Canady Helios Cold Plasma Induces Non-Thermal (24 °C), Non-Contact Irreversible Electroporation and Selective Tumor Cell Death at Surgical Margins

Simple Summary

Abstract

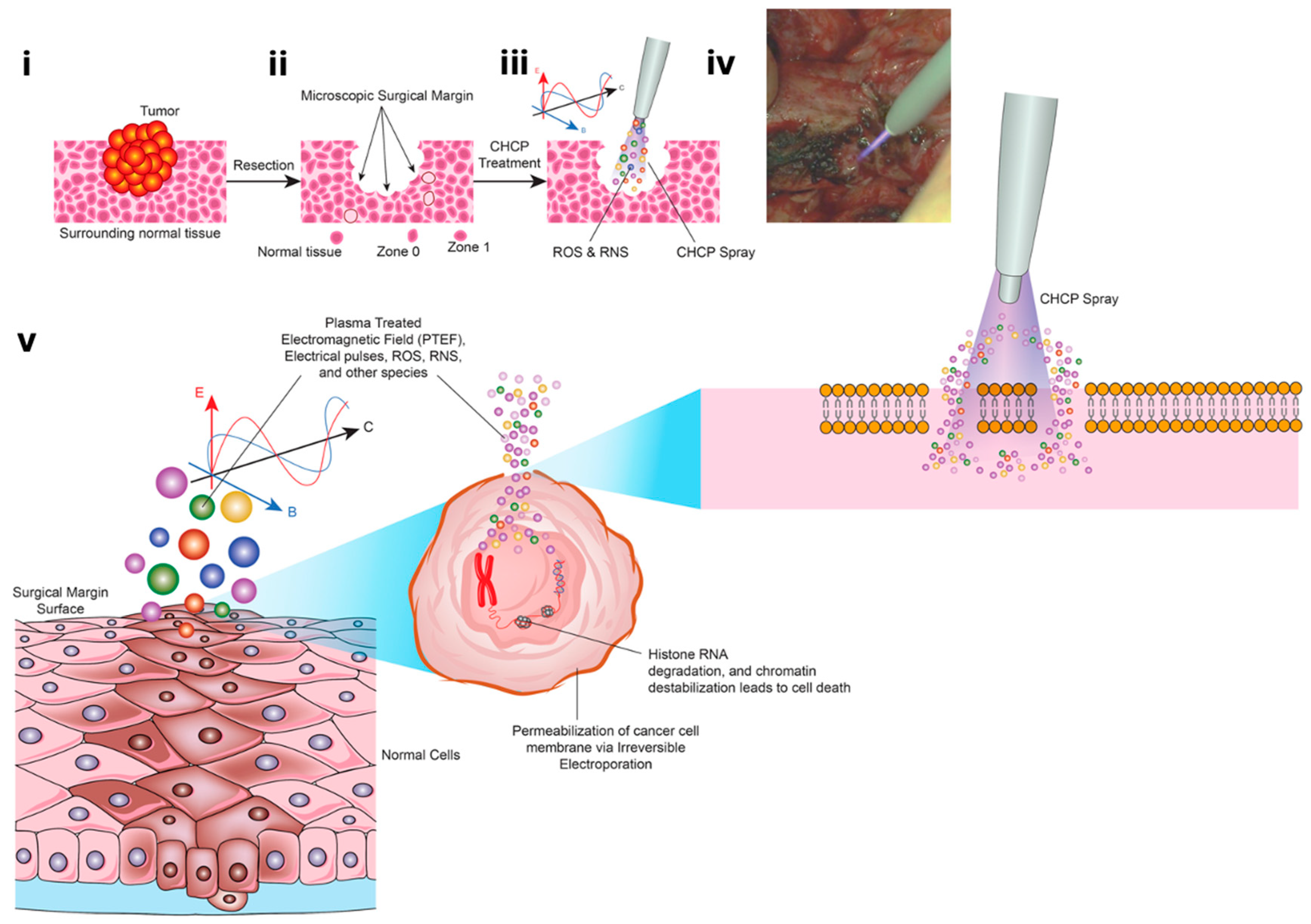

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

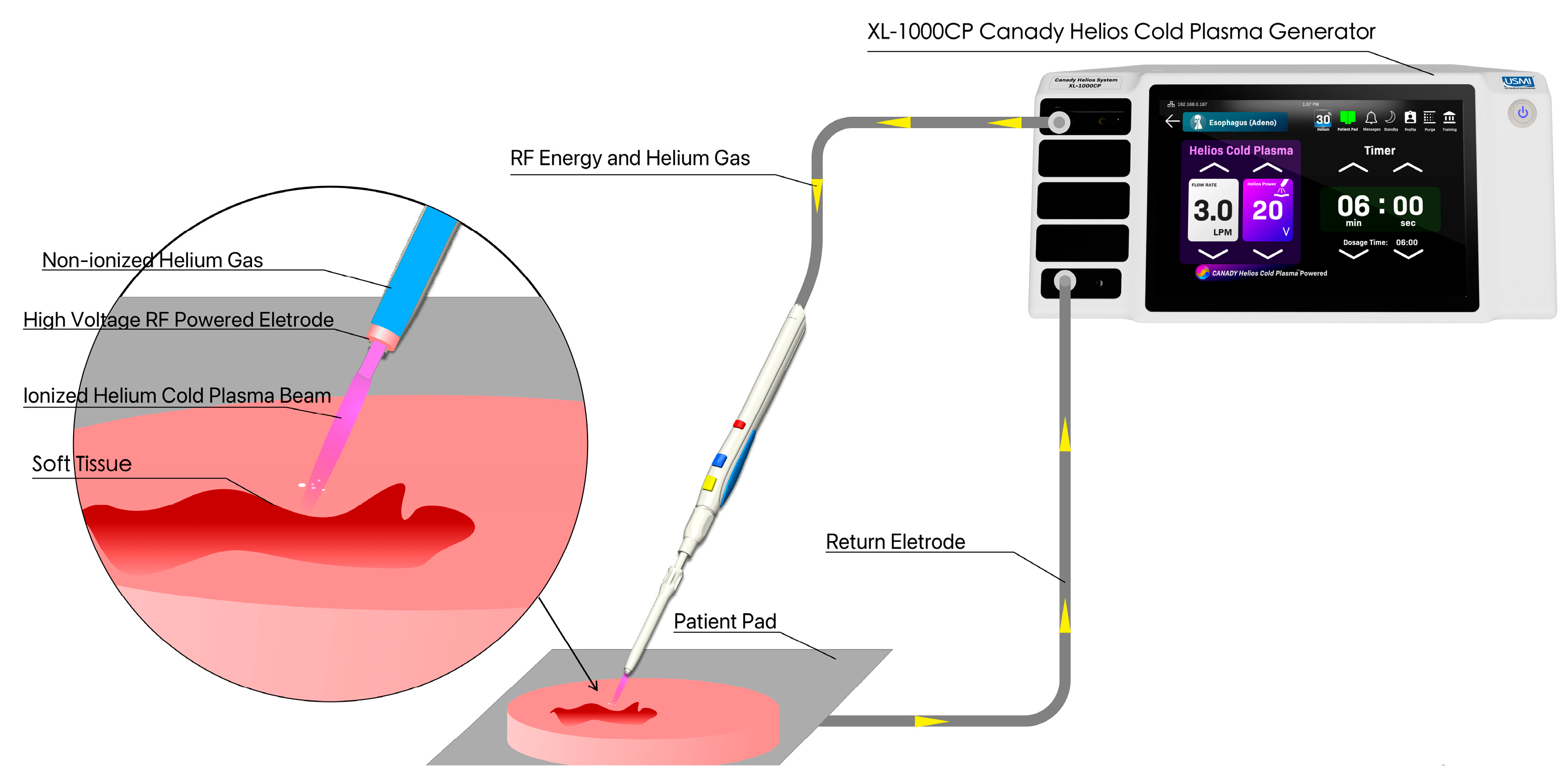

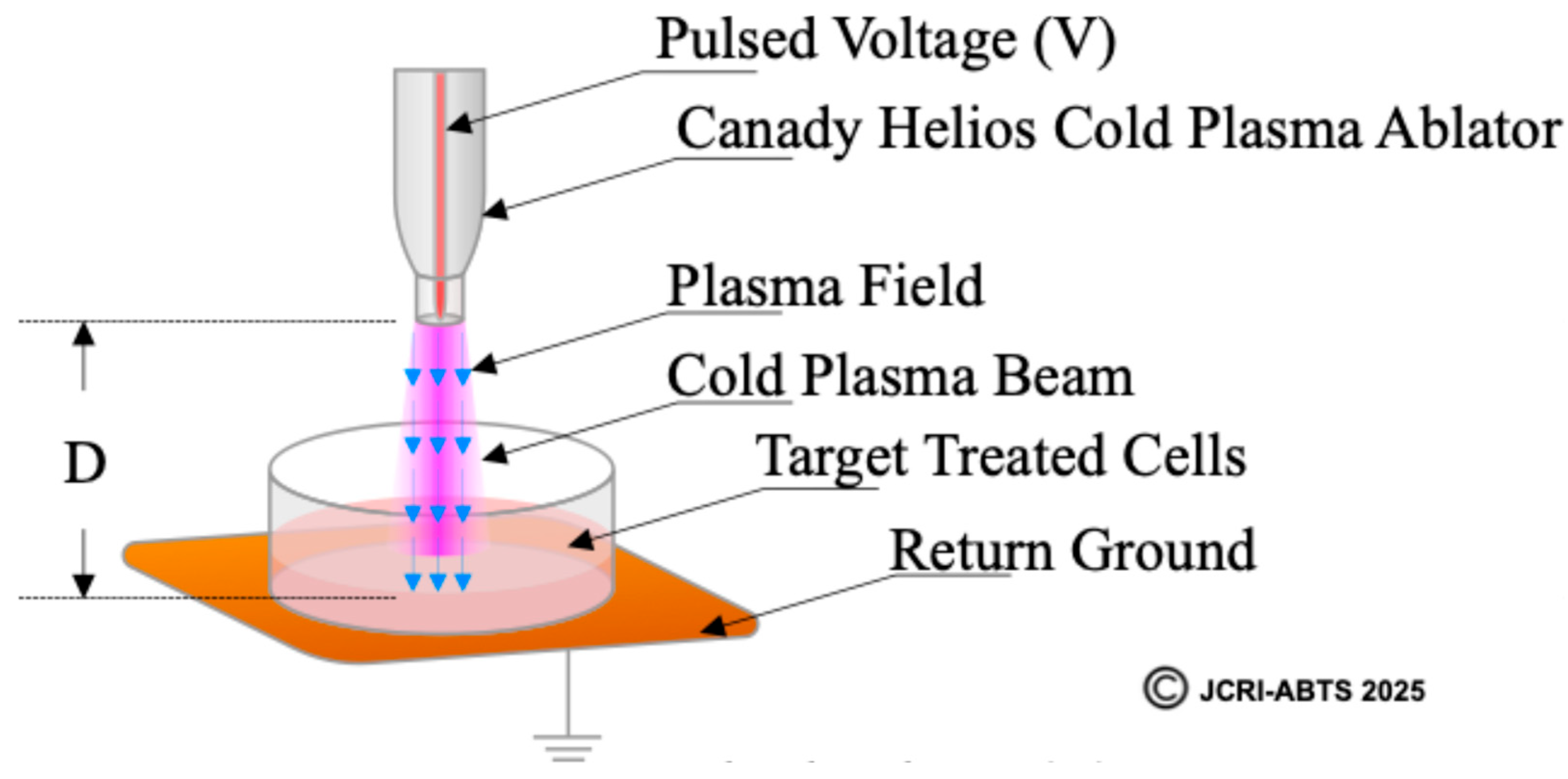

2.1. Cold Plasma Device

2.2. Definition and Calculation of the Plasma Treated Electromagnetic Field (PTEF)

2.3. Cell Culture

2.4. Treatment Protocol

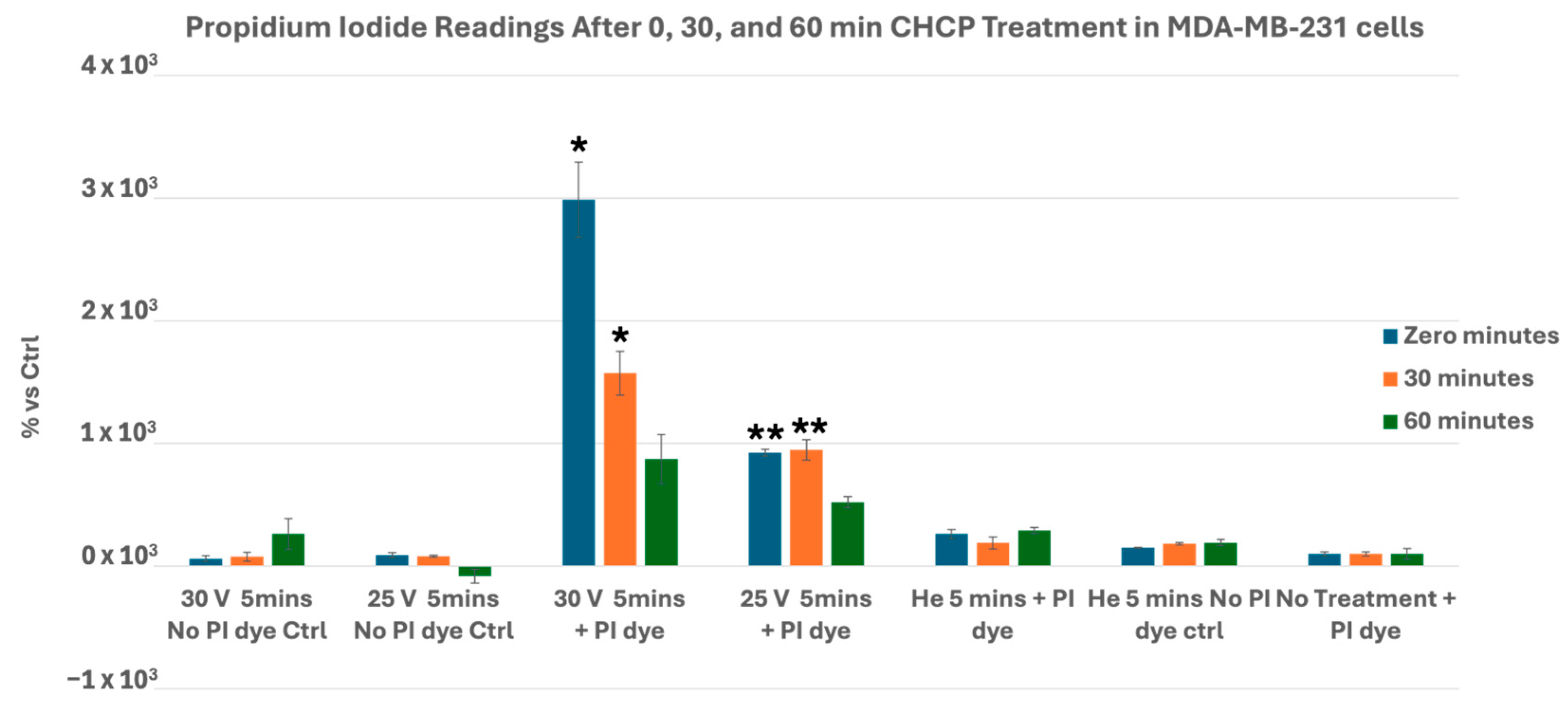

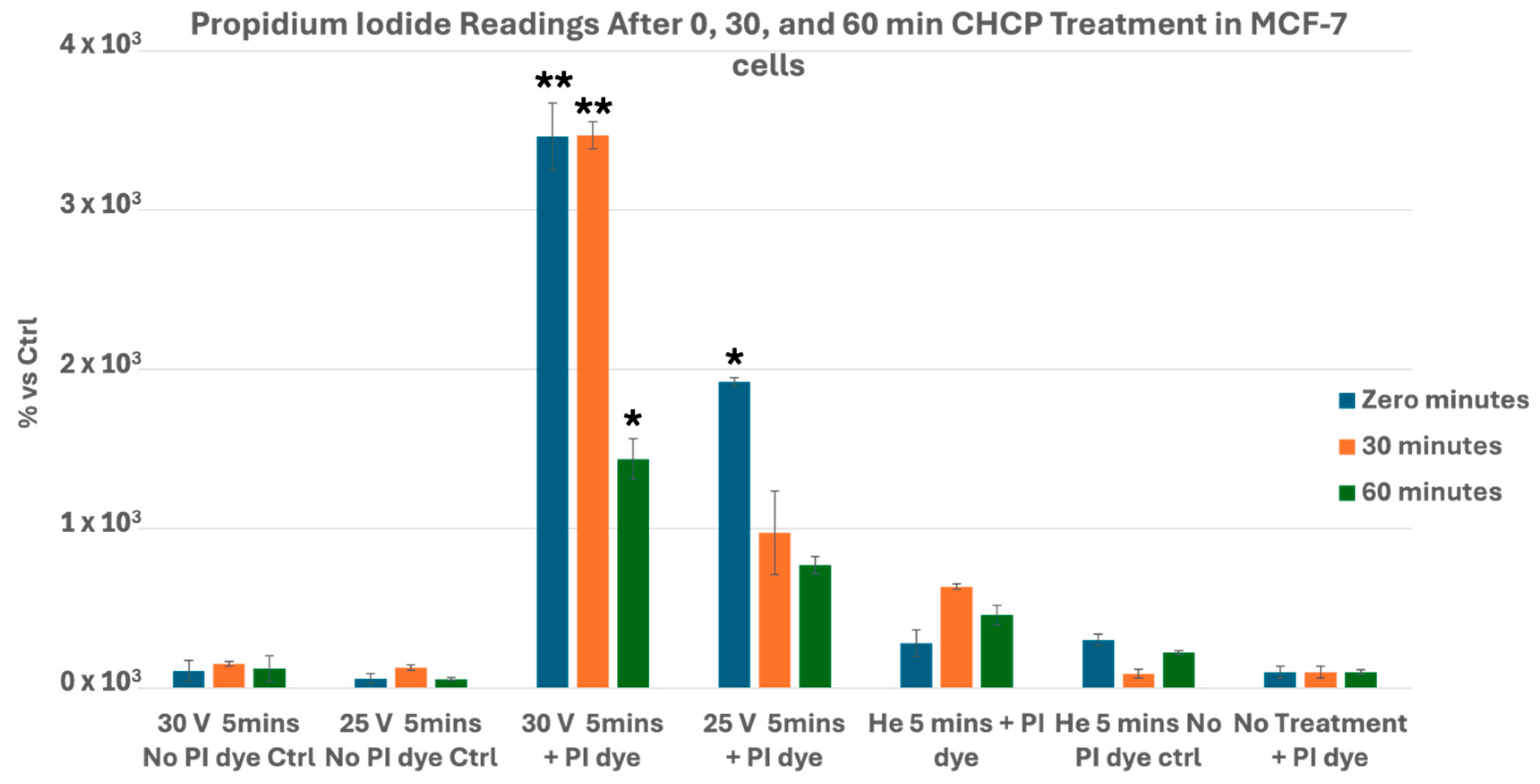

2.5. Electroporation Assay and Propidium Iodide Staining

2.6. Transfection of siRNA

2.7. Quantitative Real-Time RT-PCR

2.8. Plate Colony Formation Assay

2.9. Patient Samples

2.10. Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) Staining of Tissue Specimens

2.11. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

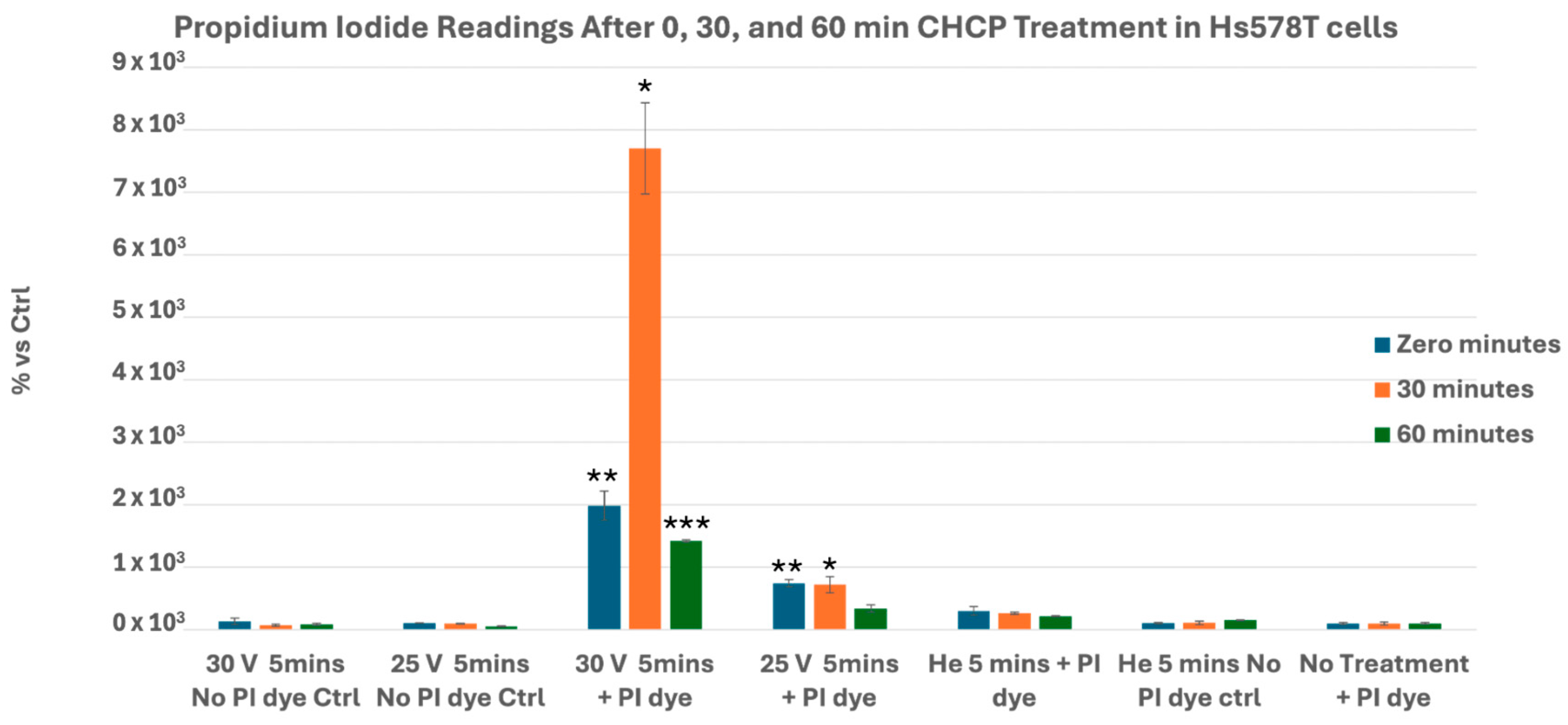

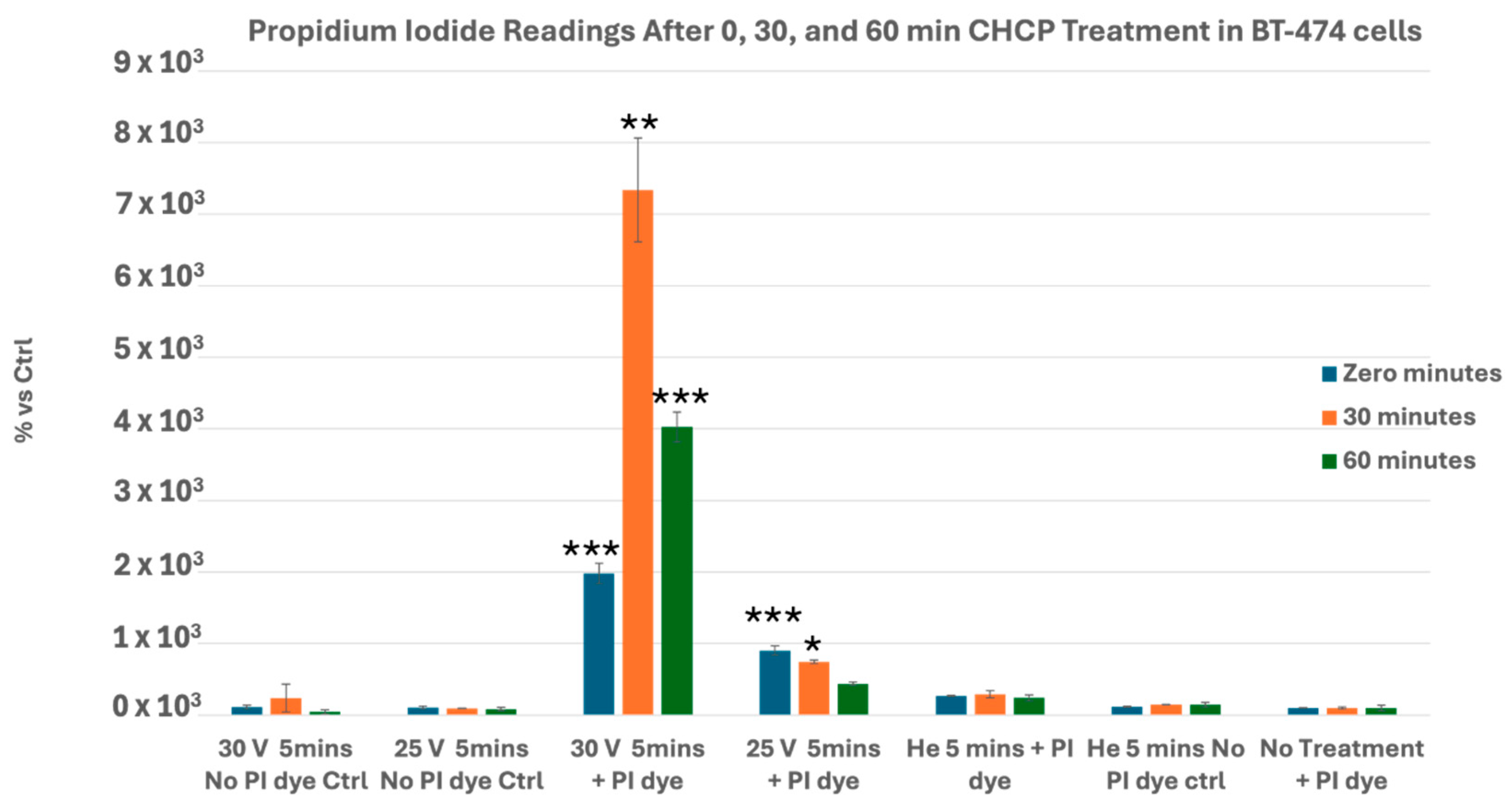

3.1. CHCP Induces Voltage- and Time-Dependent Electroporation in Breast Cancer Cells

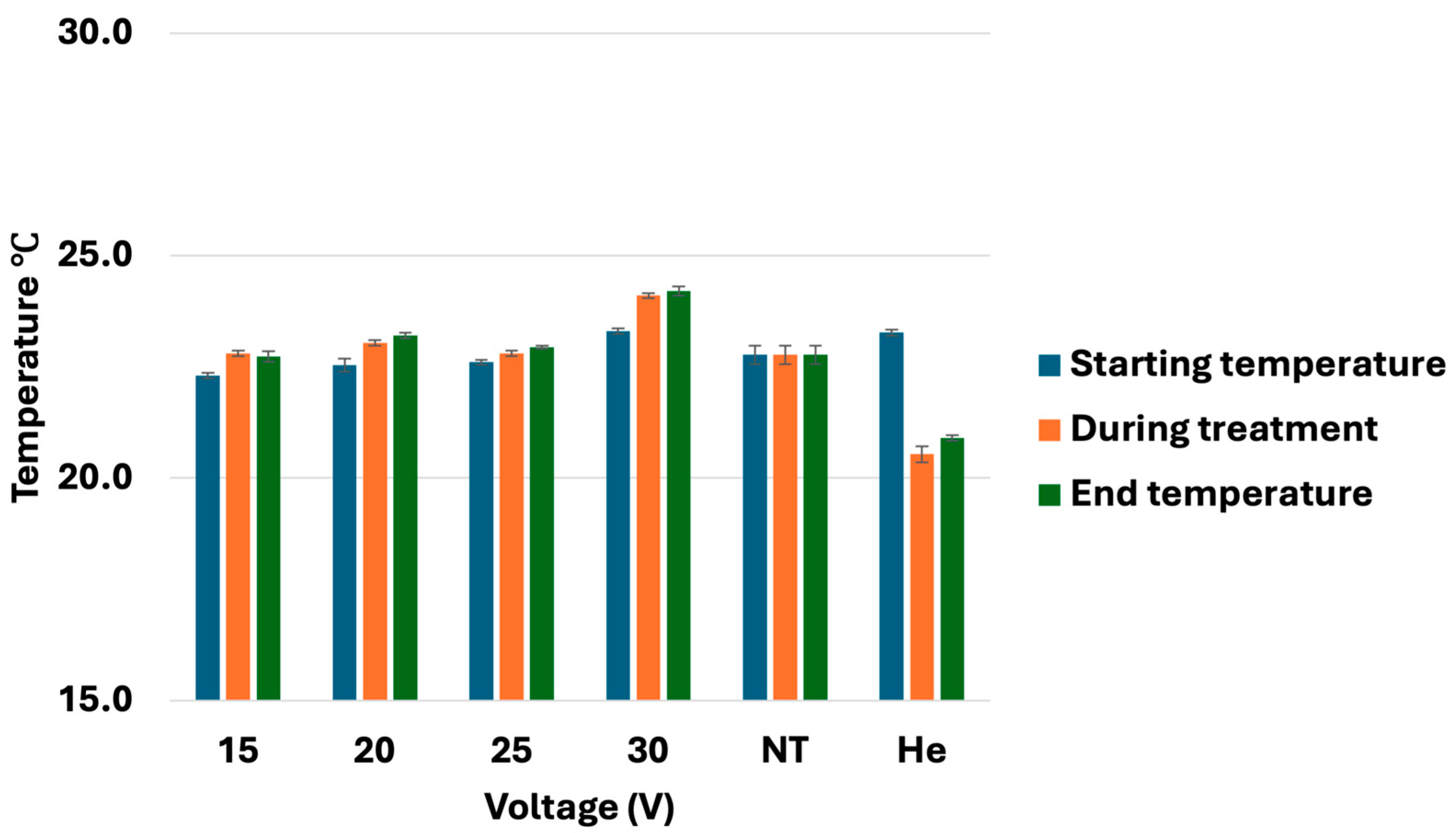

3.2. Temperature Monitoring During CHCP Treatment

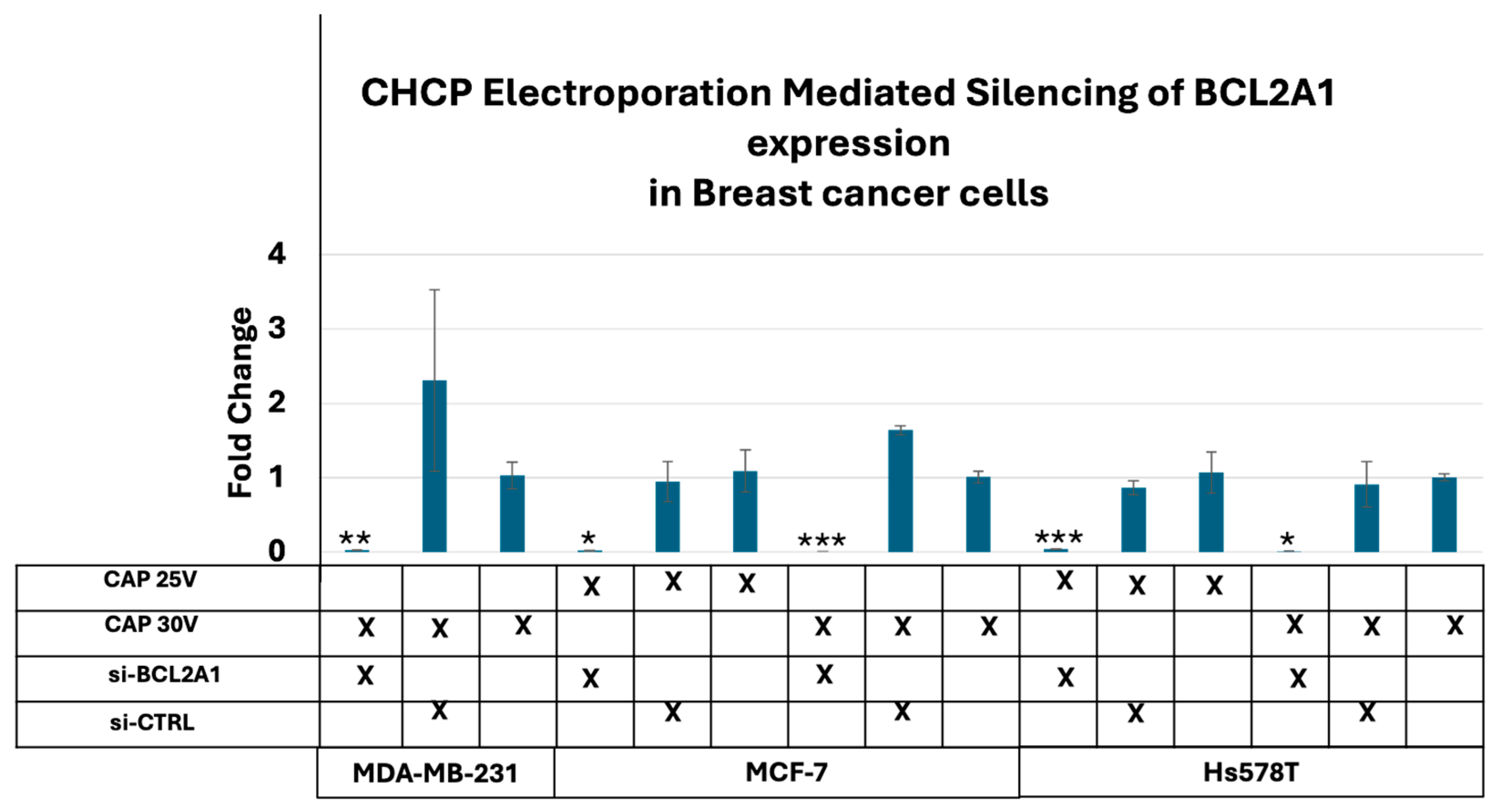

3.3. CHCP-Induced Electroporation Facilitates Efficient BCL2A1 esiRNA Delivery and Gene Silencing

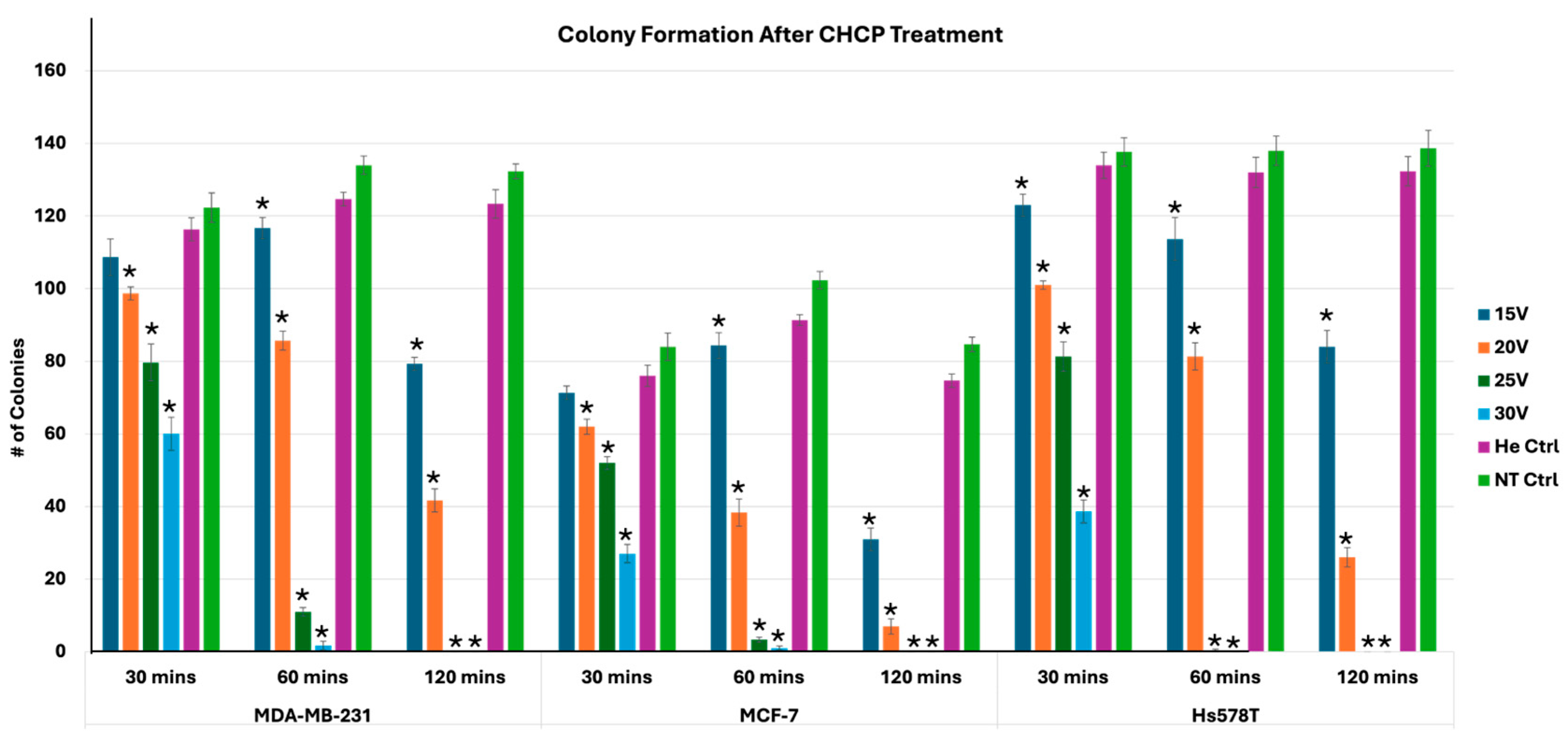

3.4. Disruption of Plasma Membrane Integrity as a Mechanism for Inhibition of Colony Formation After Cold Plasma Treatment

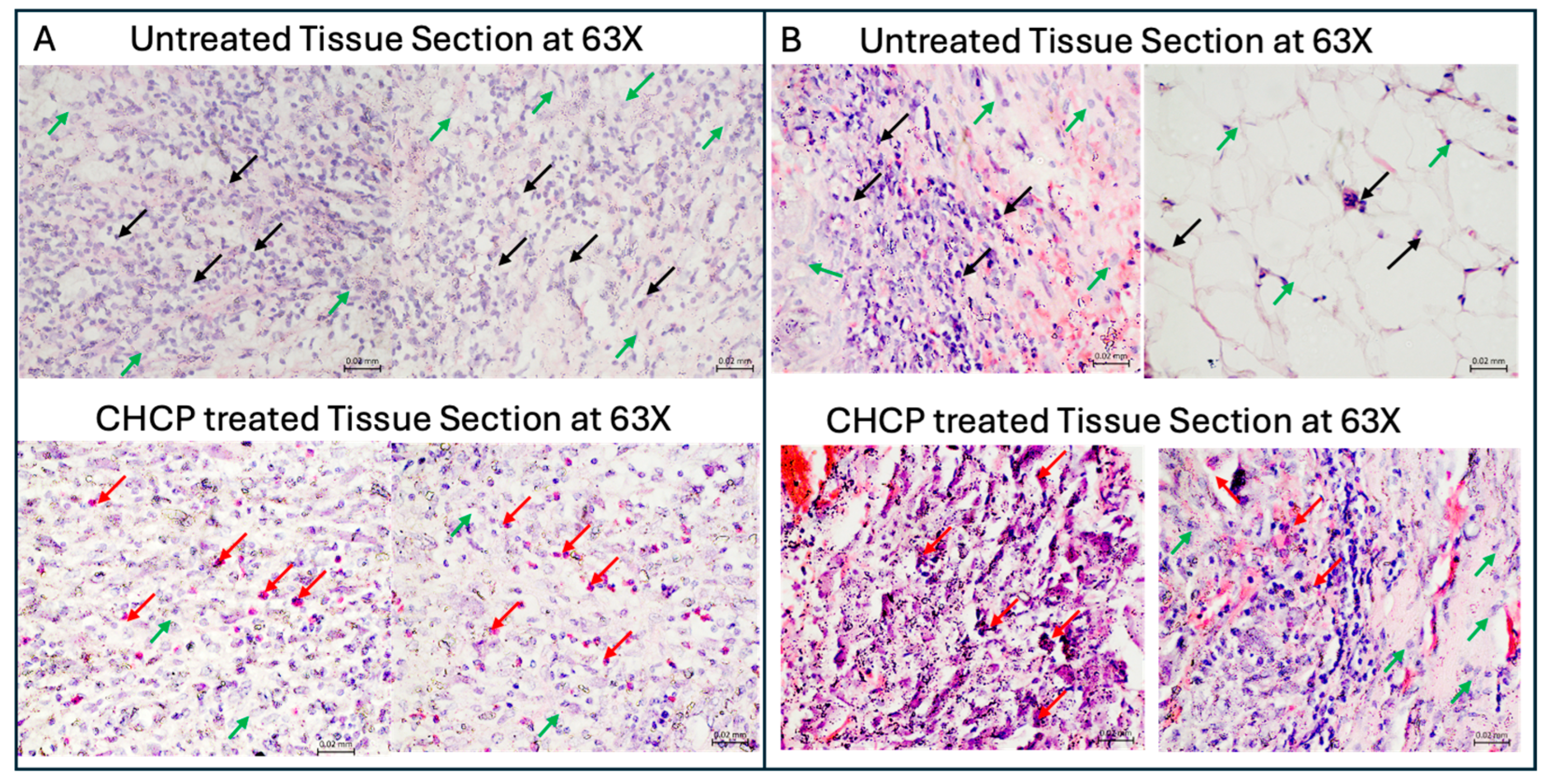

3.5. CHCP Induced Morphological Changes Consistent with Irreversible Electroporation

3.6. Ex Vivo Histopathology Reveals Selective Tumor Cell Death via CHCP-Induced Irreversible Electroporation in Human Solid Tumors

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Lee, E.W.; Thai, S.; Kee, S.T. Irreversible Electroporation: A Novel Image-Guided Cancer Therapy. Gut Liver 2010, 4, S99–S104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäumler, W.; Sebald, M.; Einspieler, I.; Wiggermann, P.; Schicho, A.; Schaible, J.; Lürken, L.; Dollinger, M.; Stroszczynski, C.; Beyer, L.P. Incidence and evolution of venous thrombosis during the first 3 months after irreversible electroporation of malignant hepatic tumours. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 19876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bäumler, W.; Sebald, M.; Einspieler, I.; Schicho, A.; Schaible, J.; Wiggermann, P.; Dollinger, M.; Stroszczynski, C.; Beyer, L.P. Evaluation of Alterations to Bile Ducts and Laboratory Values During the First 3 Months After Irreversible Electroporation of Malignant Hepatic Tumors. Cancer Manag. Res. 2020, 12, 8425–8433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, J.-C.; Xia, Z.-Y.; Sun, J.-X.; Wang, S.-G.; Xia, Q.-D. Real-world safety of irreversible electroporation therapy for tumors with nanoknife: MAUDE database analysis. BMC Surg. 2025, 25, 390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valerio, M.; Dickinson, L.; Ali, A.; Ramachandran, N.; Donaldson, I.; Freeman, A.; Ahmed, H.U.; Emberton, M. A prospective development study investigating focal irreversible electroporation in men with localised prostate cancer: Nanoknife Electroporation Ablation Trial (NEAT). Contemp. Clin. Trials 2014, 39, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knavel, E.M.; Brace, C.L. Tumor Ablation: Common Modalities and General Practices. Tech. Vasc. Interv. Radiol. 2013, 16, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Murthy, S.R.K.; Zhuang, T.; Ly, L.; Jones, O.; Basadonna, G.; Keidar, M.; Kanaan, Y.; Canady, J. Canady Helios Cold Plasma Induces Breast Cancer Cell Death by Oxidation of Histone mRNA. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 9578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ly, L.; Cheng, X.; Murthy, S.R.K.; Jones, O.Z.; Zhuang, T.; Gitelis, S.; Blank, A.T.; Nissan, A.; Adileh, M.; Colman, M.; et al. Canady Cold Helios Plasma Reduces Soft Tissue Sarcoma Viability by Inhibiting Proliferation, Disrupting Cell Cycle, and Inducing Apoptosis: A Preliminary Report. Molecules 2022, 27, 4168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ly, L.; Cheng, X.; Murthy, S.R.K.; Zhuang, T.; Jones, O.Z.; Basadonna, G.; Keidar, M.; Canady, J. Canady cold plasma conversion system treatment: An effective inhibitor of cell viability in breast cancer molecular subtypes. Clin. Plasma Med. 2020, 19–20, 100109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Rowe, W.; Ly, L.; Shashurin, A.; Zhuang, T.; Wigh, S.; Basadonna, G.; Trink, B.; Keidar, M.; Canady, J. Treatment of Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Cells with the Canady Cold Plasma Conversion System: Preliminary Results. Plasma 2018, 1, 218–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, W.; Cheng, X.; Ly, L.; Zhuang, T.; Basadonna, G.; Trink, B.; Keidar, M.; Canady, J. The Canady Helios Cold Plasma Scalpel Significantly Decreases Viability in Malignant Solid Tumor Cells in a Dose-Dependent Manner. Plasma 2018, 1, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Preston, R.; Ogawa, T.; Uemura, M.; Shumulinsky, G.; Valle, B.L.; Pirini, F.; Ravi, R.; Sidransky, D.; Keidar, M.; Trink, B. Cold atmospheric plasma treatment selectively targets head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Int. J. Mol. Med. 2014, 34, 941–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Simonyan, H.; Cheng, X.; Gjika, E.; Lin, L.; Canady, J.; Sherman, J.H.; Young, C.; Keidar, M. A Novel Micro Cold Atmospheric Plasma Device for Glioblastoma Both In Vitro and In Vivo. Cancers 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canady, J.; Murthy, S.R.K.; Zhuang, T.; Gitelis, S.; Nissan, A.; Ly, L.; Jones, O.Z.; Cheng, X.; Adileh, M.; Blank, A.T.; et al. The First Cold Atmospheric Plasma Phase I Clinical Trial for the Treatment of Advanced Solid Tumors: A Novel Treatment Arm for Cancer. Cancers 2023, 15, 3688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreedevi, P.; Suresh, K. Cold atmospheric plasma mediated cell membrane permeation and gene delivery-empirical interventions and pertinence. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 320, 102989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aycock, K.N.; Davalos, R.V. Irreversible Electroporation: Background, Theory, and Review of Recent Developments in Clinical Oncology. Bioelectricity 2019, 1, 214–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sklias, K.; Sousa, J.S.; Girard, P.-M. Role of Short- and Long-Lived Reactive Species on the Selectivity and Anti-Cancer Action of Plasma Treatment In Vitro. Cancers 2021, 13, 615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, L.; Lyu, Y.; Shneider, M.N.; Keidar, M. Average electron temperature estimation of streamer discharge in ambient air. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2018, 89, 113502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, S.R.K.; Cheng, X.; Zhuang, T.; Ly, L.; Jones, O.; Basadonna, G.; Keidar, M.; Canady, J. BCL2A1 regulates Canady Helios Cold Plasma-induced cell death in triple-negative breast cancer. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubinsky, B.; Onik, G.; Mikus, P. Irreversible Electroporation: A New Ablation Modality—Clinical Implications. Technol. Cancer Res. Treat. 2007, 6, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jacobs, E.J.; Rubinsky, B.; Davalos, R.V. Pulsed field ablation in medicine: Irreversible electroporation and electropermeabilization theory and applications. Radiol. Oncol. 2025, 59, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Narayanan, G. Irreversible electroporation for treatment of liver cancer. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2011, 7, 313–316. [Google Scholar]

- Jimenez, M.; Flandes, J.; van der Heijden, E.H.F.M.; Ng, C.S.H.; Iding, J.S.; Garcia-Hierro, J.F.; Recalde-Zamacona, B.; Verhoeven, R.L.J.; Lau, R.W.H.; Moreno-Gonzalez, A.; et al. Safety and Feasibility of Pulsed Electric Field Ablation for Early-Stage Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Prior to Surgical Resection. J. Surg. Oncol. 2025, 131, 1529–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badgwell, B.; Krouse, R.; Cormier, J.; Guevara, C.; Klimberg, V.S.; Ferrell, B. Frequent and Early Death Limits Quality of Life Assessment in Patients with Advanced Malignancies Evaluated for Palliative Surgical Intervention. Ann. Surg. Oncol. 2012, 19, 3651–3658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leegwater, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Hankemeier, T.; Zweemer, A.J.; van de Water, B.; Danen, E.; Hoekstra, M.; Harms, A.C.; et al. Distinct lipidomic profiles in breast cancer cell lines relate to proliferation and EMT phenotypes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids 2025, 1870, 159679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eiriksson, F.F.; Nøhr, M.K.; Costa, M.; Bödvarsdottir, S.K.; Ögmundsdottir, H.M.; Thorsteinsdottir, M. Lipidomic study of cell lines reveals differences between breast cancer subtypes. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0231289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lietz, A.M.; Kushner, M.J. Electrode con gurations in atmospheric pressure plasma jets: Production of reactive species. Plasma Sources Sci. Technol. 2018, 27, 105020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miebach, L.; Hagge, M.; Martinet, A.; Singer, D.; Gelbrich, N.; Kersting, S.; Bekeschus, S. Gas plasma technology mediates deep tissue and anticancer events independently of hydrogen peroxide. Trends Biotechnol. 2025, 43, 2818–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelker, M.; Müller-Goymann, C.C.; Viöl, W. Plasma Permeabilization of Human Excised Full-Thickness Skin by µs- and ns-pulsed DBD. Ski. Pharmacol. Physiol. 2020, 33, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, S.; Ke, Q.; Li, X.; Yu, L.; Huang, S. Influences of pulsed electric field parameters on cell electroporation and electrofusion events: Comprehensive understanding by experiments and molecular dynamics simulations. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0306945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitajima, N.; Makihara, K.; Kurita, H. On the Synergistic Effects of Cold Atmospheric Pressure Plasma Irradiation and Electroporation on Cytotoxicity of HeLa Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batista Napotnik, T.; Polajžer, T.; Miklavčič, D. Cell death due to electroporation—A review. Bioelectrochemistry 2021, 141, 107871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Min, T.; Xie, X.; Ren, K.; Sun, T.; Wang, H.; Dang, C.; Zhang, H. Therapeutic Effects of Cold Atmospheric Plasma on Solid Tumor. Front. Med. 2022, 9, 884887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, D.; Sherman, J.H.; Keidar, M. Cold atmospheric plasma, a novel promising anti-cancer treatment modality. Oncotarget 2016, 8, 15977–15995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanson, S.M.; Forsyth, B.; Wang, C. Combination of irreversible electroporation with sustained release of a synthetic membranolytic polymer for enhanced cancer cell killing. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razakamanantsoa, L.; Rajagopalan, N.R.; Kimura, Y.; Sabbah, M.; Thomassin-Naggara, I.; Cornelis, F.H.; Srimathveeravalli, G. Acute ATP loss during irreversible electroporation mediates caspase independent cell death. Bioelectrochemistry 2022, 150, 108355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peppicelli, S.; Calorini, L.; Bianchini, F.; Papucci, L.; Magnelli, L.; Andreucci, E. Acidity and hypoxia of tumor microenvironment, a positive interplay in extracellular vesicle release by tumor cells. Cell. Oncol. 2024, 48, 27–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montico, B.; Nigro, A.; Casolaro, V.; Col, J.D. Immunogenic Apoptosis as a Novel Tool for Anticancer Vaccine Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2018, 19, 594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryu, M.; Kim, E.; Kim, S.; Kim, K. Natural killer cell membrane manipulation for augmented immune synapse and anticancer efficacy. Mater. Today Bio 2025, 33, 101965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehan, M.C.; Collins, S.; Wimmer, T.; Gutta, N.B.; Monette, S.; Durack, J.C.; Solomon, S.B.; Srimathveeravalli, G. Non-Contact Irreversible Electroporation in the Esophagus With a Wet Electrode Approach. J. Biomech. Eng. 2023, 145, 091004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faroja, M.; Ahmed, M.; Appelbaum, L.; Ben-David, E.; Moussa, M.; Sosna, J.; Nissenbaum, I.; Goldberg, S.N. Irreversible Electroporation Ablation: Is All the Damage Nonthermal? Radiology 2013, 266, 462–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agnass, P.; van Veldhuisen, E.; van Gemert, M.J.C.; van der Geld, C.W.; van Lienden, K.P.; van Gulik, T.M.; Meijerink, M.R.; Besselink, M.G.; Kok, H.P.; Crezee, J. Mathematical modeling of the thermal effects of irreversible electroporation for in vitro, in vivo, and clinical use: A systematic review. Int. J. Hyperth. 2020, 37, 486–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Input Setting Voltage (V) | PTEF Field Strength (V/cm) |

|---|---|

| 15 V | ~1005 V/cm |

| 20 V | ~1340 V/cm |

| 25 V | ~1675 V/cm |

| 30 V | ~2010 V/cm |

| Cell Line | Time Point | F-Statistic | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| MDA-MB-231 | 30 min | 33.3 | 1.23 × 10−6 |

| MDA-MB-231 | 60 min | 742.1 | 1.64 × 10−14 |

| MDA-MB-231 | 120 min | 626.3 | 4.52 × 10−14 |

| MCF-7 | 30 min | 63.1 | 3.38 × 10−8 |

| MCF-7 | 60 min | 353.2 | 1.37 × 10−12 |

| MCF-7 | 120 min | 410.7 | 5.6 × 10−13 |

| Hs578T | 30 min | 131.1 | 4.84 × 10−10 |

| Hs578T | 60 min | 289.1 | 4.52 × 10−12 |

| Hs578T | 120 min | 358.4 | 1.26 × 10−12 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Murthy, S.R.K.; Zhuang, T.; Jones, O.Z.; Dakak, Y.; Keidar, M.; Nissan, A.; Canady, J. Canady Helios Cold Plasma Induces Non-Thermal (24 °C), Non-Contact Irreversible Electroporation and Selective Tumor Cell Death at Surgical Margins. Cancers 2025, 17, 3869. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233869

Murthy SRK, Zhuang T, Jones OZ, Dakak Y, Keidar M, Nissan A, Canady J. Canady Helios Cold Plasma Induces Non-Thermal (24 °C), Non-Contact Irreversible Electroporation and Selective Tumor Cell Death at Surgical Margins. Cancers. 2025; 17(23):3869. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233869

Chicago/Turabian StyleMurthy, Saravana R. K., Taisen Zhuang, Olivia Z. Jones, Yasmine Dakak, Michael Keidar, Aviram Nissan, and Jerome Canady. 2025. "Canady Helios Cold Plasma Induces Non-Thermal (24 °C), Non-Contact Irreversible Electroporation and Selective Tumor Cell Death at Surgical Margins" Cancers 17, no. 23: 3869. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233869

APA StyleMurthy, S. R. K., Zhuang, T., Jones, O. Z., Dakak, Y., Keidar, M., Nissan, A., & Canady, J. (2025). Canady Helios Cold Plasma Induces Non-Thermal (24 °C), Non-Contact Irreversible Electroporation and Selective Tumor Cell Death at Surgical Margins. Cancers, 17(23), 3869. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17233869