Retrospective Trial on Cetuximab Plus Radiotherapy in Elderly Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Population

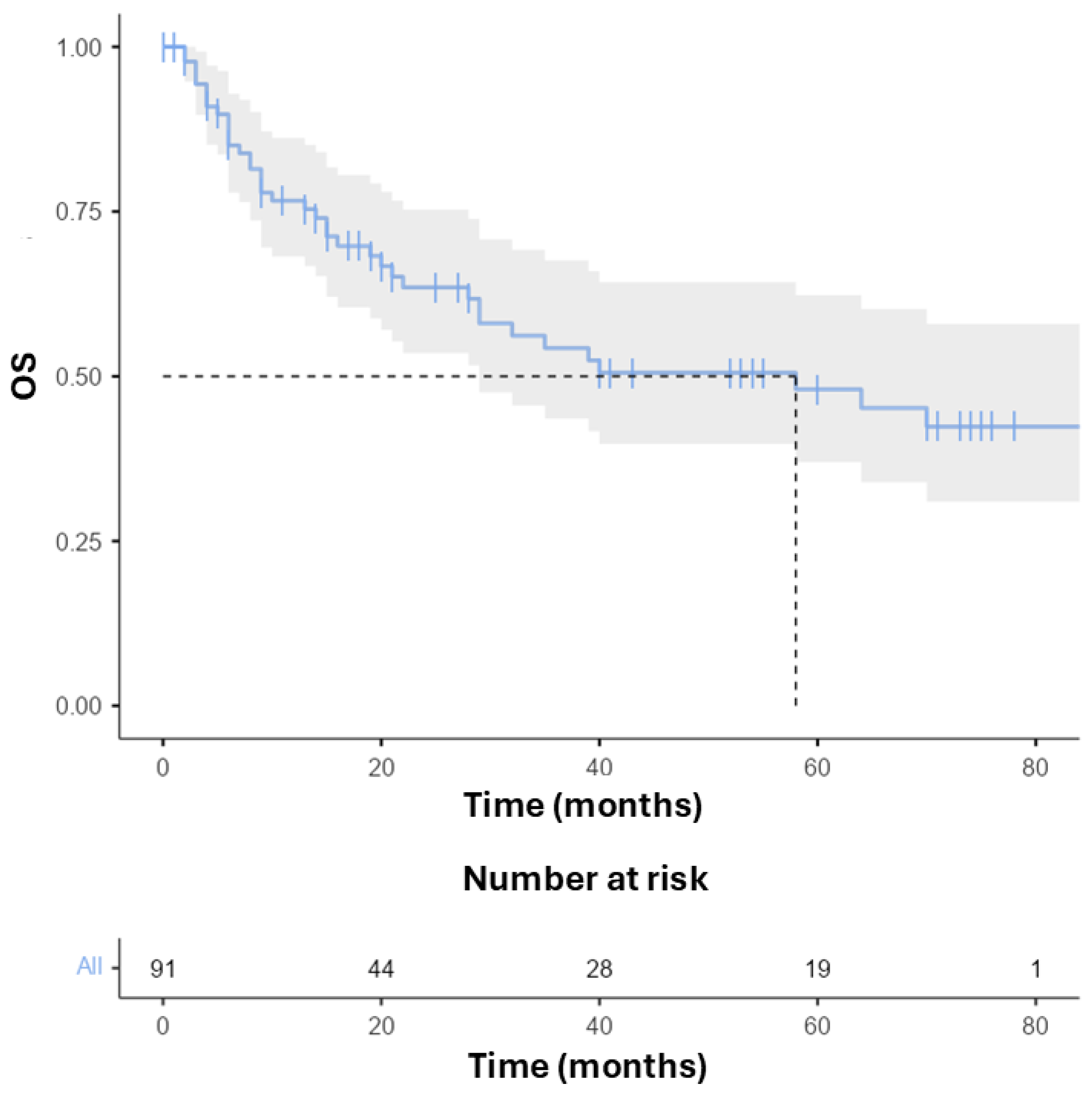

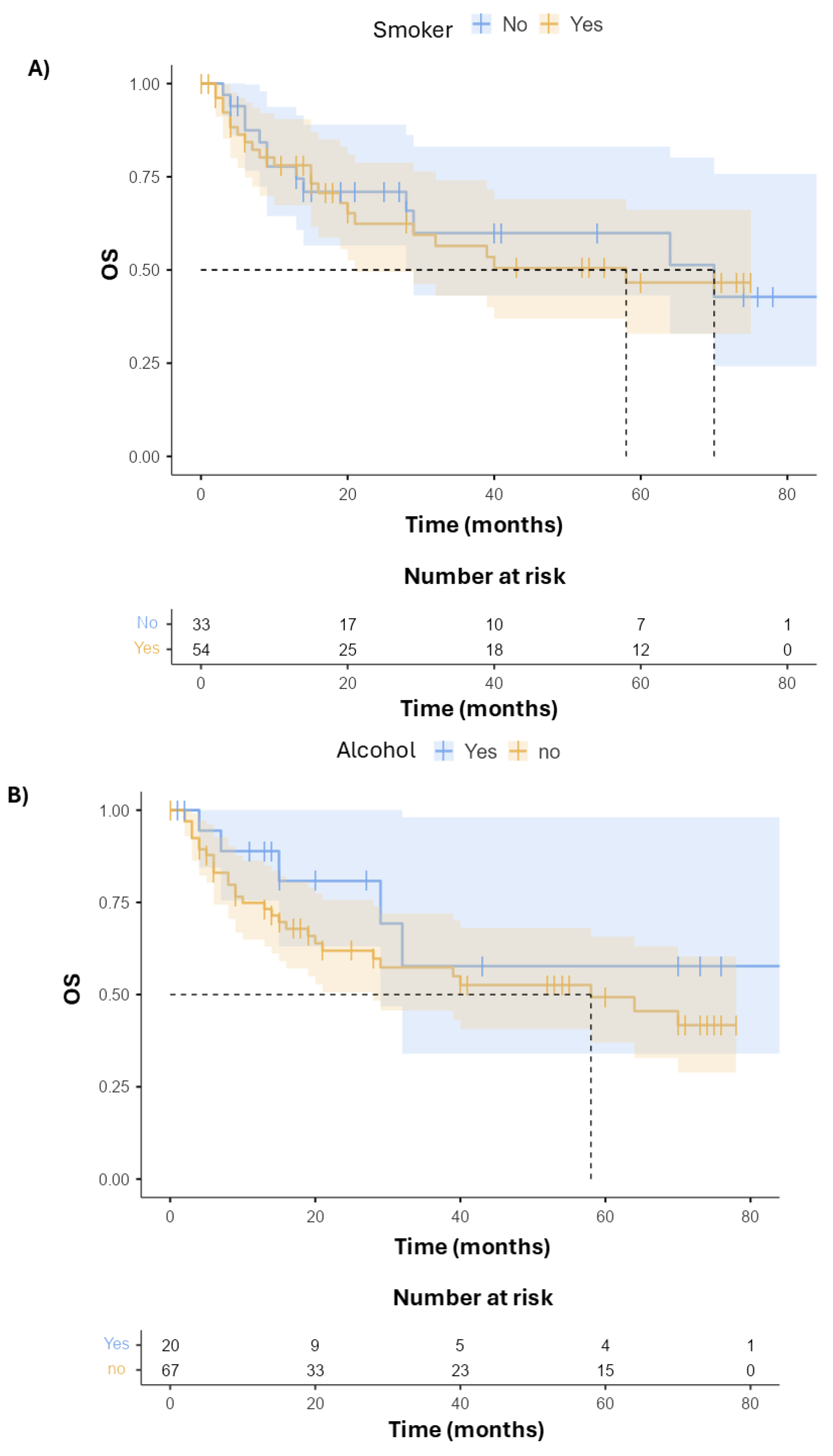

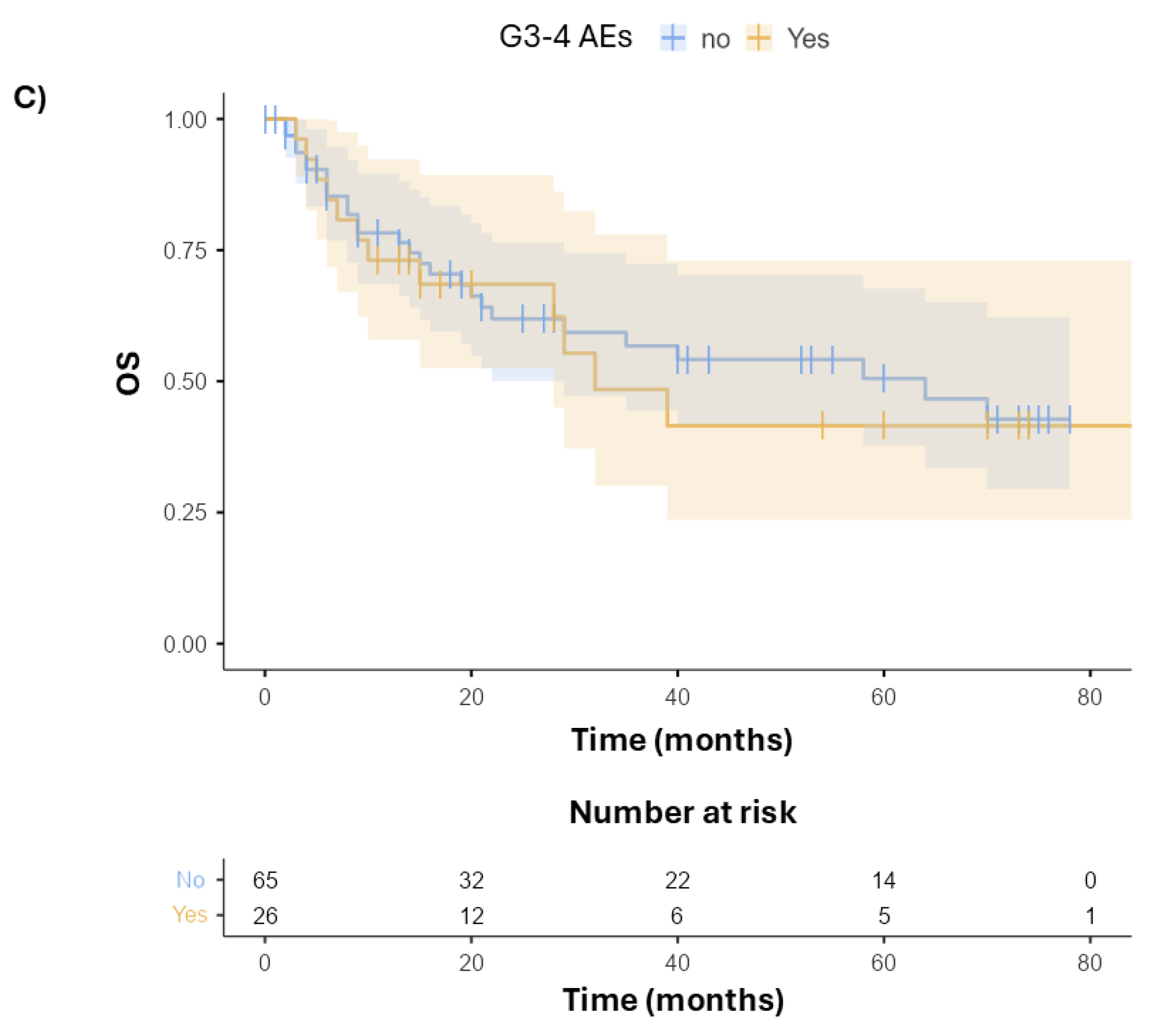

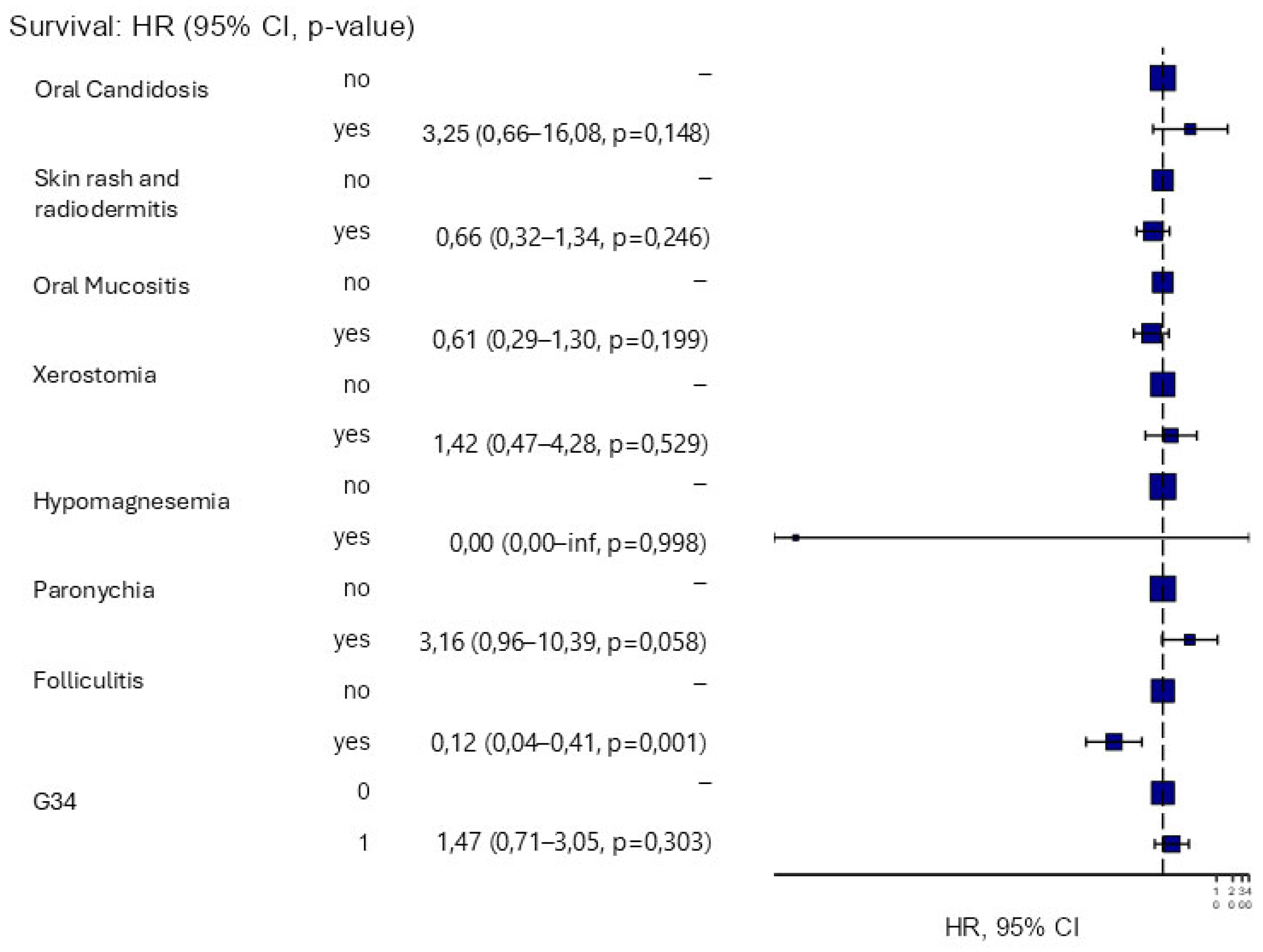

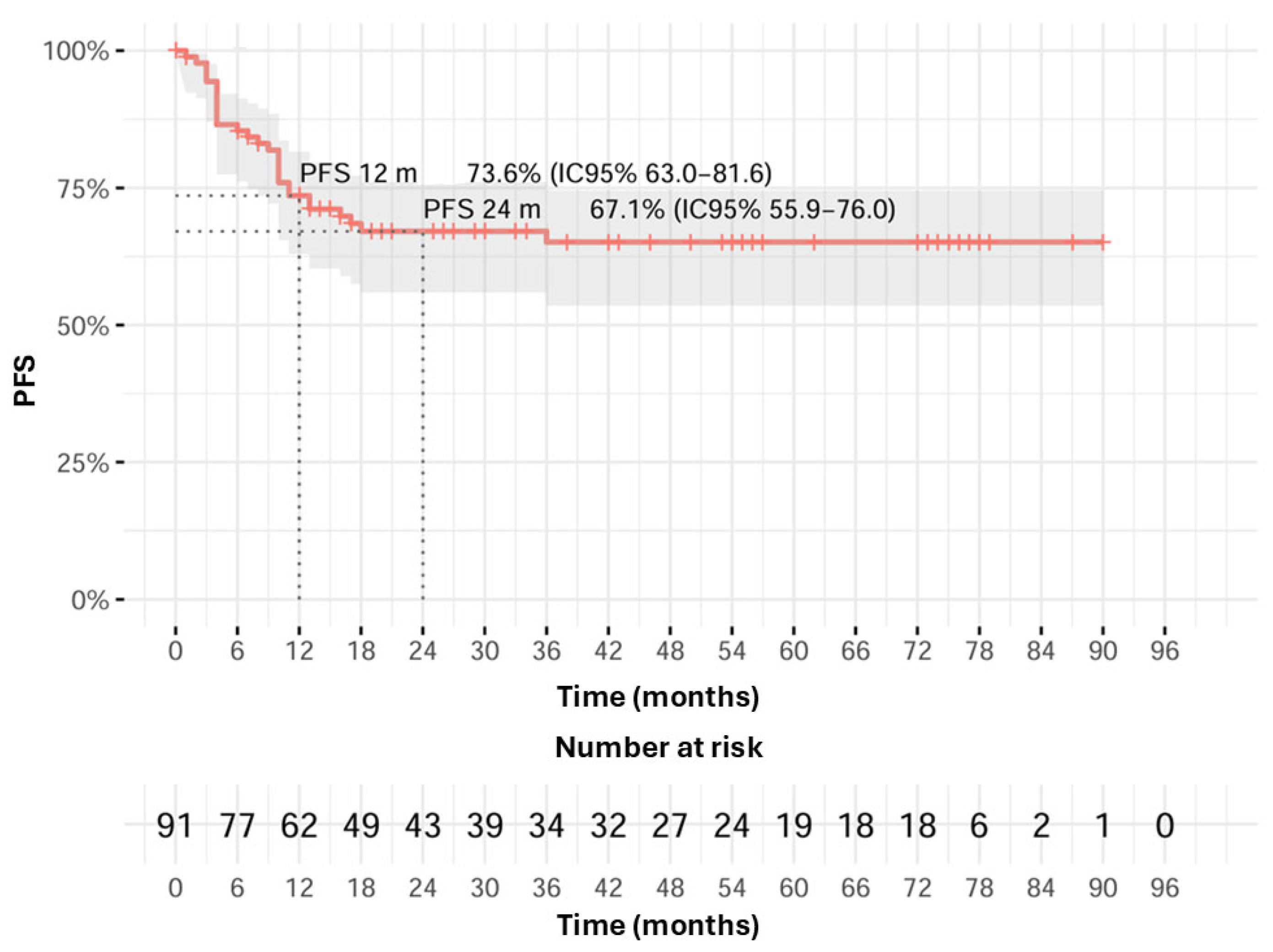

3.2. Survival and Toxicity

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Bray, F.; Ferlay, J.; Soerjomataram, I.; Siegel, R.L.; Torre, L.A.; Jemal, A. Global Cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 394–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC). Global Cancer Observatory. Available online: https://gco.iarc.fr/en (accessed on 29 September 2024).

- Gatta, G.; Capocaccia, R.; Botta, L.; Mallone, S.; De Angelis, R.; Ardanaz, E.; Comber, H.; Dimitrova, N.; Leinonen, M.K.; Siesling, S.; et al. Burden and Centralised Treatment in Europe of Rare Tumours: Results of RARECAREnet-a Population-Based Study. Lancet Oncol. 2017, 18, 1022–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ang, K.K.; Harris, J.; Wheeler, R.; Weber, R.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Nguyen-Tân, P.F.; Westra, W.H.; Chung, C.H.; Jordan, R.C.; Lu, C.; et al. Human Papillomavirus and Survival of Patients with Oropharyngeal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2010, 363, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Italiano, A.; Ortholan, C.; Dassonville, O.; Poissonnet, G.; Thariat, J.; Benezery, K.; Vallicioni, J.; Peyrade, F.; Marcy, P.Y.; Bensadoun, R.J. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Patients Aged > or = 80 Years: Patterns of Care and Survival. Cancer 2008, 113, 3160–3168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortholan, C.; Lusinchi, A.; Italiano, A.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Auperin, A.; Poissonnet, G.; Bozec, A.; Arriagada, R.; Temam, S.; Benezery, K.; et al. Oral Cavity Squamous Cell Carcinoma in 260 Patients Aged 80years or More. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 93, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pignon, J.P.; Maître, A.l.; Maillard, E.; Bourhis, J. Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer (MACH-NC): An Update on 93 Randomised Trials and 17,346 Patients. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 92, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, A.S.; Husband, D.; Rowley, H. Radical Radiotherapy for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Larynx, Oropharynx and Hypopharynx: Patterns of Recurrence, Treatment and Survival. Clin. Otolaryngol. Allied Sci. 1998, 23, 496–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, W.M.; Patel, H.; Brennan, J.; Boyle, J.O.; Sidransky, D. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck in the Elderly. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 1995, 121, 262–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusinchi, A.; Bourhis, J.; Wibault, P.; Le Ridant, A.M.; Eschwege, F. Radiation Therapy for Head and Neck Cancers in the Elderly. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1990, 18, 819–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiels, J.P.; René Leemans, C.; Golusinski, W.; Grau, C.; Licitra, L.; Gregoire, V. Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Oral Cavity, Larynx, Oropharynx and Hypopharynx: EHNS–ESMO–ESTRO Clinical Practice Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment and Follow-Up†. Ann. Oncol. 2020, 31, 1462–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AIOM (Associazione Italiana di Oncologia Medica). LINEE GUIDA TUMORI DELLA TESTA E DEL COLLO|AIOM. Available online: https://www.aiom.it/linee-guida-aiom-2021-tumori-della-testa-e-del-collo/ (accessed on 28 September 2024).

- Iqbal, M.S.; Dua, D.; Kelly, C.; Bossi, P. Managing Older Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: The Non-Surgical Curative Approach. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2018, 9, 411–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacas, B.; Carmel, A.; Landais, C.; Wong, S.J.; Licitra, L.; Tobias, J.S.; Burtness, B.; Ghi, M.G.; Cohen, E.E.W.; Grau, C.; et al. Meta-Analysis of Chemotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer (MACH-NC): An Update on 107 Randomized Trials and 19,805 Patients, on Behalf of MACH-NC Group. Radiother. Oncol. 2021, 156, 281–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonner, J.A.; Harari, P.M.; Giralt, J.; Cohen, R.B.; Jones, C.U.; Sur, R.K.; Raben, D.; Baselga, J.; Spencer, S.A.; Zhu, J.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Cetuximab for Locoregionally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer: 5-Year Survival Data from a Phase 3 Randomised Trial, and Relation between Cetuximab-Induced Rash and Survival. Lancet Oncol. 2010, 11, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Airoldi, M.; Cortesina, G.; Giordano, C.; Pedani, F.; Gabriele, A.M.; Marchionatti, S.; Bumma, C. Postoperative Adjuvant Chemoradiotherapy in Older Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2004, 130, 161–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Argiris, A.; Li, Y.; Murphy, B.A.; Langer, C.J.; Forastiere, A.A. Outcome of Elderly Patients with Recurrent or Metastatic Head and Neck Cancer Treated with Cisplatin-Based Chemotherapy. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 262–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, N. A Matched Survival Analysis for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck in the Elderly. Laryngoscope 2003, 113, 368–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machtay, M.; Moughan, J.; Trotti, A.; Garden, A.S.; Weber, R.S.; Cooper, J.S.; Forastiere, A.; Ang, K.K. Factors Associated with Severe Late Toxicity after Concurrent Chemoradiation for Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer: An RTOG Analysis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2008, 26, 3582–3589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maggiore, R.; Zumsteg, Z.S.; BrintzenhofeSzoc, K.; Trevino, K.M.; Gajra, A.; Korc-Grodzicki, B.; Epstein, J.B.; Bond, S.M.; Parker, I.; Kish, J.A.; et al. The Older Adult With Locoregionally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Knowledge Gaps and Future Direction in Assessment and Treatment. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 98, 868–883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teymoortash, A.; Ferlito, A.; Halmos, G.B. Treatment in Elderly Patients with Head and Neck Cancer: A Challenging Dilemma. HNO 2016, 64, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daly, M.E.; Lau, D.H.; Farwell, D.G.; Luu, Q.; Donald, P.J.; Chen, A.M. Feasibility and Toxicity of Concurrent Chemoradiation for Elderly Patients with Head and Neck Cancer. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2013, 34, 631–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, M.J.; D’Cruz, A.; Vermorken, J.B.; Chen, J.P.; Chitapanarux, I.; Dang, H.Q.T.; Guminski, A.; Kannarunimit, D.; Lin, T.Y.; Ng, W.T.; et al. Clinical Recommendations for Defining Platinum Unsuitable Head and Neck Cancer Patient Populations on Chemoradiotherapy: A Literature Review. Oral Oncol. 2016, 53, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongi, F.; Bignardi, M.; Garassino, I.; Pentimalli, S.; Cavina, R.; Mancosu, P.; Reggiori, G.; Poletti, A.; Ferrari, D.; Foa, P.; et al. Prospective Phase II Trial of Cetuximab plus VMAT-SIB in Locally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Feasibility and Tolerability in Elderly and Chemotherapy-Ineligible Patients. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2012, 188, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, A.D.; Bergmann, Z.P.; Garcia-Huttenlocher, H.; Freier, K.; Debus, J.; Münter, M.W. Cetuximab and Radiation for Primary and Recurrent Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (SCCHN) in the Elderly and Multi-Morbid Patient: A Single-Centre Experience. Head Neck Oncol. 2010, 2, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gillison, M.L.; Trotti, A.M.; Harris, J.; Eisbruch, A.; Harari, P.M.; Adelstein, D.J.; Sturgis, E.M.; Burtness, B.; Ridge, J.A.; Ringash, J.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Cetuximab or Cisplatin in Human Papillomavirus-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer (NRG Oncology RTOG 1016): A Randomised, Multicentre, Non-Inferiority Trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 40–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rischin, D.; King, M.; Kenny, L.; Porceddu, S.; Wratten, C.; Macann, A.; Jackson, J.E.; Bressel, M.; Herschtal, A.; Fisher, R.; et al. Randomized Trial of Radiation Therapy With Weekly Cisplatin or Cetuximab in Low-Risk HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer (TROG 12.01)—A Trans-Tasman Radiation Oncology Group Study. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2021, 111, 876–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebre-Medhin, M.; Brun, E.; Engström, P.; Cange, H.H.; Hammarstedt-Nordenvall, L.; Reizenstein, J.; Nyman, J.; Abel, E.; Friesland, S.; Sjödin, H.; et al. ARTSCAN III: A Randomized Phase III Study Comparing Chemoradiotherapy with Cisplatin versus Cetuximab in Patients with Locoregionally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 39, 38–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehanna, H.; Robinson, M.; Hartley, A.; Kong, A.; Foran, B.; Fulton-Lieuw, T.; Dalby, M.; Mistry, P.; Sen, M.; O’Toole, L.; et al. Radiotherapy plus Cisplatin or Cetuximab in Low-Risk Human Papillomavirus-Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer (De-ESCALaTE HPV): An Open-Label Randomised Controlled Phase 3 Trial. Lancet 2019, 393, 51–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, L.; Candelieri-Surette, D.; Anglin-Foote, T.; Lynch, J.A.; Maxwell, K.N.; D’Avella, C.; Singh, A.; Aakhus, E.; Cohen, R.B.; Brody, R.M. Cetuximab-Based vs Carboplatin-Based Chemoradiotherapy for Patients With Head and Neck Cancer. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 148, 1022–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beckham, T.H.; Barney, C.; Healy, E.; Wolfe, A.R.; Branstetter, A.; Yaney, A.; Riaz, N.; McBride, S.M.; Tsai, C.J.; Kang, J.; et al. Platinum-Based Regimens versus Cetuximab in Definitive Chemoradiation for Human Papillomavirus-Unrelated Head and Neck Cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2020, 147, 107–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blanchard, P.; Cheugoua-Zanetsie, M.; Deneche, I.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Gillison, M.; Eriksen, J.G.; Prabhash, K.; Giralt, J.; Bonner, J.A.; Ghi, M.G.; et al. 857O MACH-EGFR: Individual Patient Data (IPD) Meta-Analysis of Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Antibodies (Ab) in Patients (Pts) with Locally Advanced (LA) Squamous Cell Carcinomas of Head and Neck (SCCHN). Ann. Oncol. 2023, 34, S556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wildiers, H.; Heeren, P.; Puts, M.; Topinkova, E.; Janssen-Heijnen, M.L.G.; Extermann, M.; Falandry, C.; Artz, A.; Brain, E.; Colloca, G.; et al. International Society of Geriatric Oncology Consensus on Geriatric Assessment in Older Patients with Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 2595–2603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamaker, M.E.; Jonker, J.M.; de Rooij, S.E.; Vos, A.G.; Smorenburg, C.H.; van Munster, B.C. Frailty Screening Methods for Predicting Outcome of a Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in Elderly Patients with Cancer: A Systematic Review. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13, E437–E444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottel, L.; Lycke, M.; Boterberg, T.; Pottel, H.; Goethals, L.; Duprez, F.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; De Neve, W.; Rottey, S.; Geldhof, K.; et al. Serial Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment in Elderly Head and Neck Cancer Patients Undergoing Curative Radiotherapy Identifies Evolution of Multidimensional Health Problems and Is Indicative of Quality of Life. Eur. J. Cancer Care 2014, 23, 401–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottel, L.; Lycke, M.; Boterberg, T.; Pottel, H.; Goethals, L.; Duprez, F.; Rottey, S.; Lievens, Y.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Geldhof, K.; et al. G-8 Indicates Overall and Quality-Adjusted Survival in Older Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated with Curative Radiochemotherapy. BMC Cancer 2015, 15, 875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishii, R.; Ogawa, T.; Ohkoshi, A.; Nakanome, A.; Takahashi, M.; Katori, Y. Use of the Geriatric-8 Screening Tool to Predict Prognosis and Complications in Older Adults with Head and Neck Cancer: A Prospective, Observational Study. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2021, 12, 1039–1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kenis, C.; Milisen, K.; Flamaing, J.; Wildiers, H.; Decoster, L.; Van Puyvelde, K.; De Grève, J.; Conings, G.; Lobelle, J.P. Performance of Two Geriatric Screening Tools in Older Patients with Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgioia, L.; De Felice, F.; Bacigalupo, A.; Alterio, D.; Argenone, A.; D’angelo, E.; Desideri, I.; Franco, P.F.; Merlotti, A.; Musio, D.; et al. Results of a Survey on Elderly Head and Neck Cancer Patients on Behalf of the Italian Association of Radiotherapy and Clinical Oncology (AIRO). Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2020, 40, 405–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fasano, M.; D’onofrio, I.; Belfiore, M.P.; Angrisani, A.; Caliendo, V.; Della Corte, C.M.; Pirozzi, M.; Facchini, S.; Caterino, M.; Guida, C.; et al. Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma in Elderly Patients: Role of Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy. Cancers 2022, 14, 472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelstein, D.J.; Li, Y.; Adams, G.L.; Wagner, H.; Kish, J.A.; Ensley, J.F.; Schuller, D.E.; Forastiere, A.A. An Intergroup Phase III Comparison of Standard Radiation Therapy and Two Schedules of Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in Patients with Unresectable Squamous Cell Head and Neck Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 92–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forastiere, A.A.; Goepfert, H.; Maor, M.; Pajak, T.F.; Weber, R.; Morrison, W.; Glisson, B.; Trotti, A.; Ridge, J.A.; Chao, C.; et al. Concurrent Chemotherapy and Radiotherapy for Organ Preservation in Advanced Laryngeal Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003, 349, 2091–2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forastiere, A.A.; Zhang, Q.; Weber, R.S.; Maor, M.H.; Goepfert, H.; Pajak, T.F.; Morrison, W.; Glisson, B.; Trotti, A.; Ridge, J.A.; et al. Long-Term Results of RTOG 91-11: A Comparison of Three Nonsurgical Treatment Strategies to Preserve the Larynx in Patients with Locally Advanced Larynx Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellera, C.A.; Rainfray, M.; Mathoulin-Pélissier, S.; Mertens, C.; Delva, F.; Fonck, M.; Soubeyran, P.L. Screening Older Cancer Patients: First Evaluation of the G-8 Geriatric Screening Tool. Ann. Oncol. 2012, 23, 2166–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, P.; Loi, M.; Desideri, I.; Olmetto, E.; Delli Paoli, C.; Terziani, F.; Greto, D.; Mangoni, M.; Scoccianti, S.; Simontacchi, G.; et al. Incidence of Skin Toxicity in Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck Treated with Radiotherapy and Cetuximab: A Systematic Review. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 120, 98–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pottel, L.; Boterberg, T.; Pottel, H.; Goethals, L.; Van Den Noortgate, N.; Duprez, F.; De Neve, W.; Rottey, S.; Geldhof, K.; Van Eygen, K.; et al. Determination of an Adequate Screening Tool for Identification of Vulnerable Elderly Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated with Radio(Chemo)Therapy. J. Geriatr. Oncol. 2012, 3, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonomo, P.; Livi, L. De-Intensification for HPV Positive Oropharyngeal Cancer: And yet It Moves!: 2019 in Review. Clin. Transl. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 22, 40–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horsley, P.J.; Perera, L.; Veness, M.J.; Stevens, M.J.; Eade, T.N.; Back, M.; Brown, C.; Jayamanne, D.T. Outcomes for Elderly Patients 75 Years and Older Treated with Curative Intent Radiotherapy for Mucosal Squamous Cell Carcinomas of the Head and Neck. Head Neck 2020, 42, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sommers, L.W.; Steenbakkers, R.J.H.M.; Bijl, H.P.; Vemer-van den Hoek, J.G.M.; Roodenburg, J.L.N.; Oosting, S.F.; Halmos, G.B.; de Rooij, S.E.; Langendijk, J.A. Survival Patterns in Elderly Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma Patients Treated With Definitive Radiation Therapy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2017, 98, 793–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leeman, J.E.; Li, J.-G.; Pei, X.; Venigalla, P.; Zumsteg, Z.S.; Katsoulakis, E.; Lupovitch, E.; McBride, S.M.; Tsai, C.J.; Boyle, J.O.; et al. Patterns of Treatment Failure and Postrecurrence Outcomes Among Patients With Locally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma After Chemoradiotherapy Using Modern Radiation Techniques. JAMA Oncol. 2017, 3, 1487–1494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, J.S.; Pajak, T.F.; Forastiere, A.A.; Jacobs, J.; Campbell, B.H.; Saxman, S.B.; Kish, J.A.; Kim, H.E.; Cmelak, A.J.; Rotman, M.; et al. Postoperative Concurrent Radiotherapy and Chemotherapy for High-Risk Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2004, 350, 1937–1944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, S.A.; Ronis, D.L.; McLean, S.; Fowler, K.E.; Gruber, S.B.; Wolf, G.T.; Terrell, J.E. Pretreatment Health Behaviors Predict Survival among Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 2009, 27, 1969–1975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharp, L.; McDevitt, J.; Carsin, A.E.; Brown, C.; Comber, H. Smoking at Diagnosis Is an Independent Prognostic Factor for Cancer-Specific Survival in Head and Neck Cancer: Findings from a Large, Population-Based Study. Cancer Epidemiol. Biomark. Prev. 2014, 23, 2579–2590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.; Nastasi, D.; Tso, R.; Vangaveti, V.; Renison, B.; Chilkuri, M. The Effects of Continued Smoking in Head and Neck Cancer Patients Treated with Radiotherapy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Radiother. Oncol. 2019, 135, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Rahman, O.; Fouad, M. Correlation of Cetuximab-Induced Skin Rash and Outcomes of Solid Tumor Patients Treated with Cetuximab: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2015, 93, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bar-Ad, V.; Zhang, Q.E.; Harari, P.M.; Axelrod, R.; Rosenthal, D.I.; Trotti, A.; Jones, C.U.; Garden, A.S.; Song, G.; Foote, R.L.; et al. Correlation Between the Severity of Cetuximab-Induced Skin Rash and Clinical Outcome for Head and Neck Cancer Patients: The RTOG Experience. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2016, 95, 1346–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fülöp, T.; Dupuis, G.; Witkowski, J.M.; Larbi, A. The Role of Immunosenescence in the Development of Age-Related Diseases. Rev. Investig. Clin. 2016, 68, 84–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jehn, C.F.; Böning, L.; Kröning, H.; Possinger, K.; Lüftner, D. Cetuximab-Based Therapy in Elderly Comorbid Patients with Metastatic Colorectal Cancer. Br. J. Cancer 2012, 106, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugtenberg, R.T.; Boers-Doets, C.B.; Witteveen, P.O.; van Herpen, C.M.L.; Wymenga, A.N.M.; de Groot, J.W.B.; Hoeben, A.; del Grande, C.; van Doorn, B.; Koldenhof, J.J.; et al. Prospective Practice Survey of Management of Cetuximab-Related Skin Reactions. Support. Care Cancer 2021, 29, 3497–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Dee, E.C.; Bach, D.Q.; Mostaghimi, A.; Leboeuf, N.R. Evaluation of a Comprehensive Skin Toxicity Program for Patients Treated With Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors at a Cancer Treatment Center. JAMA Dermatol. 2020, 156, 1079–1085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addeo, R.; Caraglia, M.; Vincenzi, B.; Luce, A.; Montella, L.; Mastella, A.; Mazzone, S.; Ricciardiello, F.; Carraturo, M.; Del Prete, S.; et al. Efficacy and Safety of Cetuximab plus Radiotherapy in Cisplatin-Unfit Elderly Patients with Advanced Squamous Cell Head and Neck Carcinoma: A Retrospective Study. Chemotherapy 2019, 64, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Felice, F.; Vetrone, L.; Bulzonetti, N.; Caiazzo, R.; Marampon, F.; Musio, D.; Tombolini, V. Hypofractionated Radiotherapy Combined with Cetuximab in Vulnerable Elderly Patients with Locally Advanced Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Med. Oncol. 2019, 36, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, A.; Teoh, D.; Sanghera, P.; Hartley, A. Radiotherapy Compliance Is Maintained with Hypofractionation and Concurrent Cetuximab in Locally Advanced Head and Neck Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 93, 654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, D.I.; Porceddu, S.V.; Burmeister, B.H.; Guminski, A.; Thomson, D.B.; Shepherdson, K.; Poulsen, M. Enhanced Toxicity with Concurrent Cetuximab and Radiotherapy in Head and Neck Cancer. Radiother. Oncol. 2009, 90, 172–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourhis, J.; Tao, Y.; Sun, X.; Sire, C.; Martin, L.; Liem, X.; Coutte, A.; Pointreau, Y.; Thariat, J.; Miroir, J.; et al. LBA35 Avelumab-Cetuximab-Radiotherapy versus Standards of Care in Patients with Locally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Head and Neck (LA-SCCHN): Randomized Phase III GORTEC-REACH Trial. Ann. Oncol. 2021, 32, S1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therapeutics, C.; Harrington, A.K.J.; Tao, Y.; Auperin, A.; Sun, X.; Liem, X.; Sire, C.; Martin, L.; Pointreau, Y.; Borel, C.; et al. 854MO Avelumab-Cetuximab-Radiotherapy (RT) versus Standards of Care in Patients with Locally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of Head and Neck (LA-SCCHN): Final Analysis of Randomized Phase III GORTEC 2017-01 REACH Trial. Ann. Oncol. 2024, 35, S616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Machiels, J.P.; Tao, Y.; Licitra, L.; Burtness, B.; Tahara, M.; Rischin, D.; Alves, G.; Lima, I.P.F.; Hughes, B.G.M.; Pointreau, Y.; et al. Pembrolizumab plus Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy versus Placebo plus Concurrent Chemoradiotherapy in Patients with Locally Advanced Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (KEYNOTE-412): A Randomised, Double-Blind, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2024, 25, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bourhis, J.; Auperin, A.; Borel, C.; Lefebvre, G.; Racadot, S.; Geoffrois, L.; Sun, X.S.; Saada, E.; Cirauqui, B.; Rutkowski, T.; et al. NIVOPOSTOP (GORTEC 2018-01): A Phase III Randomized Trial of Adjuvant Nivolumab Added to Radio-Chemotherapy in Patients with Resected Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma at High Risk of Relapse. J. Clin. Oncol. 2025, 43, LBA2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, A.; Juloori, A.; Agrawal, N.; Cursio, J.; Jelinek, M.J.; Cipriani, N.; Lingen, M.W.; Wolk, R.; Chin, J.; Jones, M.; et al. Neoadjuvant Nivolumab, Paclitaxel, and Carboplatin Followed by Response-Stratified Chemoradiation in Locoregionally Advanced HPV Negative Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma (HNSCC): The DEPEND Trial. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 6007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency (EMA). Erbitux—SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS. Available online: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/product-information/erbitux-epar-product-information_en.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- Nimri, F.; Ghanimeh, M.A.; Venkat, D. S2675 Cetuximab-Induced Liver Injury: A Side Effect of What We Thought Is “an Innocent Subject”! Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2020, 115, S1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chua, W.; Peters, M.; Loneragan, R.; Clarke, S. Cetuximab-Associated Pulmonary Toxicity. Clin. Color. Cancer 2009, 8, 118–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, K.; Seto, A.; Sasaki, T.; Shimbashi, W.; Fukushima, H.; Yonekawa, H.; Mitani, H.; Takahashi, S. Incidence and Risk Factors of Interstitial Lung Disease of Patients with Head and Neck Cancer Treated with Cetuximab. Head Neck 2019, 41, 2574–2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tejpar, S.; Taniguchi, H.; Falco, A.; Velthuis, E.; Pineda, C.V.; Mesia, R. Prevention and Management of Cetuximab-Related Hypomagnesemia. J. Clin. Oncol. 2022, 40, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miroddi, M.; Sterrantino, C.; Simonelli, I.; Ciminata, G.; Phillips, R.S.; Calapai, G. Risk of Grade 3-4 Diarrhea and Mucositis in Colorectal Cancer Patients Receiving Anti-EGFR Monoclonal Antibodies Regimens: A Meta-Analysis of 18 Randomized Controlled Clinical Trials. Crit. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2014, 96, 355–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lacouture, M.E.; Anadkat, M.J.; Bensadoun, R.J.; Bryce, J.; Chan, A.; Epstein, J.B.; Eaby-Sandy, B.; Murphy, B.A. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of EGFR Inhibitor-Associated Dermatologic Toxicities. Support. Care Cancer 2011, 19, 1079–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kajizono, M.; Saito, M.; Maeda, M.; Yamaji, K.; Fujiwara, S.; Kawasaki, Y.; Matsunaga, H.; Sendo, T. Cetuximab-Induced Skin Reactions Are Suppressed by Cigarette Smoking in Patients with Advanced Colorectal Cancer. Int. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 18, 684–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincenzi, B.; Santini, D.; Loupakis, F.; Addeo, R.; Llimpe, F.L.R.; Baldi, G.G.; Di Fabio, F.; Del Prete, S.; Pinto, C.; Falcone, A.; et al. Cigarettes Smoking Habit May Reduce Benefit from Cetuximab-Based Treatment in Advanced Colorectal Cancer Patients. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2009, 9, 945–949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pryor, D.I.; Burmeister, E.; Burmeister, B.H.; Poulsen, M.G.; Porceddu, S.V. Distinct Patterns of Stomatitis with Concurrent Cetuximab and Radiotherapy for Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Oral. Oncol. 2011, 47, 984–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madan, V.; Ortiz-López, L.I.; Sakunchotpanit, G.; Chen, R.; Nayudu, K.; Nambudiri, V.E. Psoriasis in the Era of Targeted Cancer Therapeutics: A Systematic Review on De Novo and Pre-Existing Psoriasis in Oncologic Patients Treated with Emerging Anti-Neoplastic Agents. Dermatol. Ther. 2024, 14, 1755–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segaert, S.; Van Cutsem, E. Clinical Signs, Pathophysiology and Management of Skin Toxicity during Therapy with Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Inhibitors. Ann. Oncol. 2005, 16, 1425–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jatoi, A.; Thrower, A.; Sloan, J.A.; Flynn, P.J.; Wentworth-Hartung, N.L.; Dakhil, S.R.; Mattar, B.I.; Nikcevich, D.A.; Novotny, P.; Sekulic, A.; et al. Does Sunscreen Prevent Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) Inhibitor–Induced Rash? Results of a Placebo-Controlled Trial from the North Central Cancer Treatment Group (N05C4). Oncologist 2010, 15, 1016–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runge, C.L.; Lyness, J.; Gillison, M.; Adelstein, D.J.; Harari, P.M.; Ringash, J.G.; Geiger, J.L.; Krempl, G.A.; Blakaj, D.; Bates, J.; et al. Hearing Outcomes in Cisplatin or Cetuximab Combined with Radiation for Patients with HPV-Associated Oropharyngeal Cancer in NRG/RTOG 1016. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2023, 117, S122–S123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Population | 82 | |

|---|---|---|

| Females | 18 | 22% |

| Males | 64 | 78% |

| Median age | 74 | (65–89 years) |

| Median G8 score | 11.6 | (4–17) |

| Primary tumor sites | ||

| Oral cavity | 23 | 25.38% |

| Hypopharynx | 2 | 2.2% |

| Larynx | 35 | 38.5% |

| Oropharynx | 25 | 27.5% |

| Unknown primary | 6 | 6.6% |

| Stage | ||

| III | 26 | 28.6% |

| IVa | 38 | 41.8% |

| IVb | 20 | 21.9% |

| Unknown | 7 | 7.9% |

| Smokers | 54 | 59.3% |

| Alcohol consumption | 20 | 21.9% |

| Substance abuse | 1 | 1.1% |

| Adverse Event | All Grade | G3–4 |

|---|---|---|

| Skin rash and radiodermatitis | 26.8% | 9.9% |

| Oral Mucositis | 30.8% | 15.5% |

| Folliculitis | 22% | 5.5% |

| Dysphagia | 9.9% | 6.6% |

| Xerostomia | 7.7% | 2.2% |

| Paronychia | 5.5% | 0% |

| Oral Candidiasis | 4.4% | 0% |

| Hypomagnesemia | 1.1% | 0% |

| HR (Univariable) | HR (Multivariable) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Smoking | Yes | 10 (26.3) | - | - |

| No | 28 (73.7) | 1.39 (0.29–6.56, p = 0.678) | 3.14 (0.54–18.14, p = 0.201) | |

| Alcohol | No | 11 (28.9) | - | - |

| Yes | 27 (71.1) | 0.00 (0.00–Inf, p = 0.999) | 0.00 (0.00–Inf, p = 0.998) | |

| G3–4 AEs | No | 6 (15.8) | - | - |

| Yes | 32 (84.2) | 0.81 (0.17–3.82, p = 0.788) | 0.67 (0.12–3.90, p = 0.656) |

| Absolute Contraindications | Notes | References |

| Impaired renal function | No data on patients with Creatinine ≥ x1.5 upper limit value | [70] |

| Severe marrow dysfunction | No data on patients with Hb < 9, Leukocyte < 3000, Neutrophils < 1500, platelets < 100,000 | [70] |

| Hepatic dysfunction | No data on patients if AST/ALT ≥ x5 upper limit value Case report of Cetuximab-related DILI | [70,71] |

| Respiratory dysfunction | Increased risk of ILD | [72,73] |

| Metabolic dysfunction | Risk of hypomagnesemia, hypocalcemia | [70,74] |

| Relative Contraindications | Rationale | References |

| Age | No clear benefit over 65 years old of Cetuximab + RT in LA HNSCC | [15,24,25] |

| Performance status | Patients presented PS ≤ 2 in the Bonner trial of Cetuximab + RT | [15] |

| Weight loss | Risk of increased weight loss due to mucositis, diarrhea | [25,75] |

| Cardiovascular dysfunction | Increased frequency of severe cardiovascular events | [70] |

| Intercurrent infections | Risk of secondary infections of cutaneous and mucosal lesions | [70,76] |

| Intrinsic Factors to Consider | Rationale | References |

| Smoking | Risk of increased resistance, ILD, and toxicity | [73,77,78,79] |

| Pre-existing dermatological conditions | Worsening of pre-existing dermatological lesions | [76,80,81] |

| Sun exposure | Sun sensitivity, no benefit from sunscreen | [76,82] |

| Hearing function | Increased hearing loss with CisRT than with Cetuximab + RT | [83] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Fasano, M.; Perri, F.; Pirozzi, M.; Deantoni, C.L.; Valsecchi, D.; Cirillo, A.; Addeo, R.; Vitale, P.; De Felice, F.; Tralongo, P.; et al. Retrospective Trial on Cetuximab Plus Radiotherapy in Elderly Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer. Cancers 2025, 17, 3550. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213550

Fasano M, Perri F, Pirozzi M, Deantoni CL, Valsecchi D, Cirillo A, Addeo R, Vitale P, De Felice F, Tralongo P, et al. Retrospective Trial on Cetuximab Plus Radiotherapy in Elderly Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer. Cancers. 2025; 17(21):3550. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213550

Chicago/Turabian StyleFasano, Morena, Francesco Perri, Mario Pirozzi, Chiara Lucrezia Deantoni, Davide Valsecchi, Alessio Cirillo, Raffaele Addeo, Pasquale Vitale, Francesca De Felice, Paolo Tralongo, and et al. 2025. "Retrospective Trial on Cetuximab Plus Radiotherapy in Elderly Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer" Cancers 17, no. 21: 3550. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213550

APA StyleFasano, M., Perri, F., Pirozzi, M., Deantoni, C. L., Valsecchi, D., Cirillo, A., Addeo, R., Vitale, P., De Felice, F., Tralongo, P., Farese, S., Ruffilli, B., Romano, F., Guizzardi, M., Giordano, L., Pontone, M., Marciano, M. L., Rampetta, F. R., Longo, F., ... Mirabile, A. (2025). Retrospective Trial on Cetuximab Plus Radiotherapy in Elderly Patients with Head and Neck Squamous Cell Cancer. Cancers, 17(21), 3550. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers17213550