Simple Summary

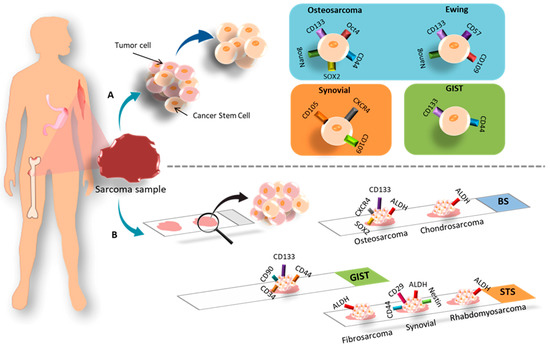

Cancer stem cells (CSCs) are responsible for the great challenge in the treatment of sarcomas due to their high prediction to form metastases. This systematic review focuses on collecting existing research on the expression of CSC markers in different types of sarcomas in both in vitro cell lines and patient samples. The results show a great heterogeneity of the studied markers, with ALDH being the only marker commonly used in sarcomas. This broader view may help to develop new CSC characterization assays to advance in more personalized treatments.

Abstract

Sarcomas are a diverse group of neoplasms with an incidence rate of 15% of childhood cancers. They exhibit a high tendency to develop early metastases and are often resistant to available treatments, resulting in poor prognosis and survival. In this context, cancer stem cells (CSCs) have been implicated in recurrence, metastasis, and drug resistance, making the search for diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers of the disease crucial. The objective of this systematic review was to analyze the expression of CSC biomarkers both after isolation from in vitro cell lines and from the complete cell population of patient tumor samples. A total of 228 publications from January 2011 to June 2021 was retrieved from different databases, of which 35 articles were included for analysis. The studies demonstrated significant heterogeneity in both the markers detected and the CSC isolation techniques used. ALDH was identified as a common marker in various types of sarcomas. In conclusion, the identification of CSC markers in sarcomas may facilitate the development of personalized medicine and improve treatment outcomes.

1. Introduction

Sarcomas are a diverse group of neoplasms comprising over 100 subtypes, all originating from mesenchymal cells [1]. Although rare in adults (1%), sarcomas are becoming increasingly prevalent in children and adolescents, with an incidence of 15% of childhood cancers [2]. Currently, they are classified into three groups: (i) bone sarcomas (BS) (15%), which include chondrosarcoma, osteosarcoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, giant cell tumor, and others; (ii) soft tissue sarcomas (STS) (80%), with rhabdomyosarcoma, liposarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, synovial sarcoma, fibrosarcoma, desmoplastic small round cell tumor, and malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor being the most frequent subtypes; and (iii) gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) [1,3,4].

Despite current treatments (a combination of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy with surgery), sarcoma prognosis and survival remain poor due to the high propensity of sarcomas to form metastases, even at the time of diagnosis, with undetectable micrometastases [5,6,7,8]. The high intratumoral heterogeneity contributes to the ineffectiveness of existing treatments [9]. Within the tumor, there is a subpopulation of cells exhibiting pluripotent embryonic stem cell characteristics, called cancer stem cells (CSCs), that are involved in tumor initiation, proliferation, recurrence, metastasis, and drug resistance [10,11,12,13]. This has sparked interest in developing an alternative approach to target the cells responsible for tumor and metastasis formation [14].

The use of CSCs as diagnostic and prognostic markers is increasingly important in various cancers. However, although some markers, such as Sox2, ALDH1, CD117, CD133, among others, have been described in sarcomas, there is no standardized differential pattern for each subtype that can be used clinically [15,16,17,18]. Additionally, more and more in vitro studies are being carried out with isolated CSCs to investigate their drug resistance and identify more effective treatments [19]. Hence, although numerous methodologies for the isolation of CSCs exist, there is a need to standardize the isolation methods and identify the most suitable CSC markers for each sarcoma subtype [11,20].

Given the importance of CSCs and their association with poor sarcoma prognosis, in addition to the great heterogeneity in the use of different markers in CSC research, this systematic review aims to collect all existing studies on the use of CSCs as prognostic biomarkers in sarcomas and the methods used to isolate and characterize these cells for preclinical in vitro studies in order to establish the markers that define CSCs in the different subtypes of sarcomas.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Eligibility

The objective of this systematic review was to collect the most recent and representative data on CSC markers in sarcoma cancer, as well as isolation techniques for this aggressive cell subgroup for in vitro culture. This review was performed in accordance to the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) [21] guidelines and has not been registered. We collected the bibliography of the last 10 years and considered the literature from previous years as obsolete. More than half of the current bibliography on the subject was included according to the Burton–Kebler obsolescence index [22].

2.2. Inclusion Criteria

Research articles were included if they were published between January 2011 and June 2021, studied the expression of CSC markers in human sarcoma cell lines and/or human tumor tissue samples, and included the method of isolation and characterization of CSCs. Open access full-text research articles were also included. No language restriction was established.

2.3. Exclusion Criteria

Research articles were excluded if they were repeated among the different databases. Articles that did not study marker expression in sarcoma lines or that used non-human sarcoma cell lines or cells derived from xenografts or xenotransplantation were excluded. Non-original articles, including reviews, clinical cases, clinical trials, systematic reviews, conference proceedings, editorials, letters, notes, patents, and book chapters, were also excluded.

2.4. Data Sources

The present systematic review was carried out using the following databases: MedLars Online International Literature, through PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science, and Cochrane Library Plus. Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) were defined using the descriptive terms “sarcoma”, “cancer stem cells”, and “biological markers”. The final equation was (((“Sarcoma”[Mesh] OR “Sarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “Osteosarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “Rhabdomyosarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “chondrosarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “synovial sarcoma” [Title/Abstract] OR “epithelioid sarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors”[Title/Abstract] OR “Ewing’s sarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “uterine sarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “leiomyosarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “pleomorphic sarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “fibrosarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “angiosarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “liposarcoma”[Title/Abstract] OR “Myxofibrosarcoma”[Title/Abstract]) AND (cancer stem cells[MeSH Terms] OR cancer stem cell[MeSH Terms])) AND (biological markers[MeSH Terms] OR “biomarkers” [MeSH Terms]) AND (“2011/01/01”[PDAT]: “2021/05/28”[PDAT]))). The same strategy was followed in all the databases, adapting the equation when necessary. In addition, the bibliography of the selected articles was reviewed to include other works of interest that did not appear in the initial search.

2.5. Study Selection

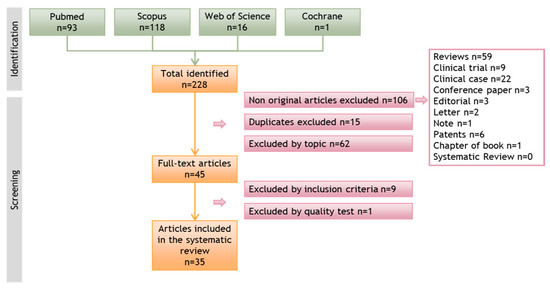

Authors M.C. and C.M. conducted a bibliographic search in various databases and performed a first screening based on the titles and abstracts. The second step involved a complete reading of the research articles that passed the first screening. In both steps, the articles were evaluated based on the pre-established inclusion and exclusion criteria. In vitro studies were the focus of this review, and articles that only conducted in vivo studies were excluded at this stage. Figure 1 depicts the flow diagram of the selection process.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram illustrating the search process and article screening in different databases that led to the selection of relevant articles for this systematic review.

2.6. Data Extraction

Following the selection process, M.C. and C.M. independently extracted the data of interest from each research article. According to Cohen’s Kappa statistic test [23], there was good correlation between M.C. and C.M. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion until a consensus was reached. Otherwise, a third experienced author made the final decision. Each research article was subjected to a quality test for in vitro studies, which was divided into two phases. The first phase contained filters on the basic characteristics that an in vitro study should meet (score ≥ 5). Studies that did not meet this score were excluded. The second phase comprised questions on methodology, results, and conclusion. The studies were classified based on their score: low quality (score 0–5), medium quality (score 6–15), and high quality (score 16–20). Table 1 and Table 2 show the obtained data for ease of understanding. Both tables display the reference of the selected article, the type of sarcoma studied, the type of sample, the methodology of CSC extraction and characterization, and the main results.

Table 1.

Isolation methodology and biomarkers expression of isolated CSCs from sarcoma cell lines and/or tumoral samples.

Table 2.

Biomarkers expression without isolation of sarcoma cell lines and/or tumor tissue.

3. Results

A total of 228 articles were identified in the initial search across the different databases consulted. After eliminating non-original articles (n = 106), duplicates between databases (n = 15), and articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria, 45 articles were retained for detailed analysis. Subsequently, 9 articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria and 1 that scored very low in the quality test were discarded. Finally, 35 articles were included in this systematic review. The flow diagram representing the search process and the screening of the articles is presented in Figure 1.

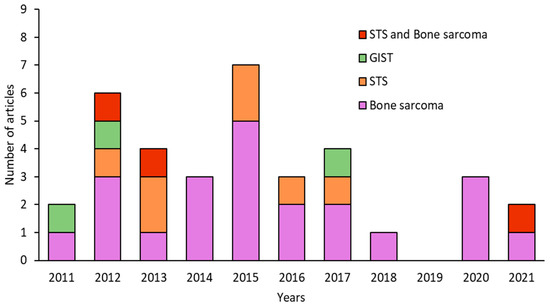

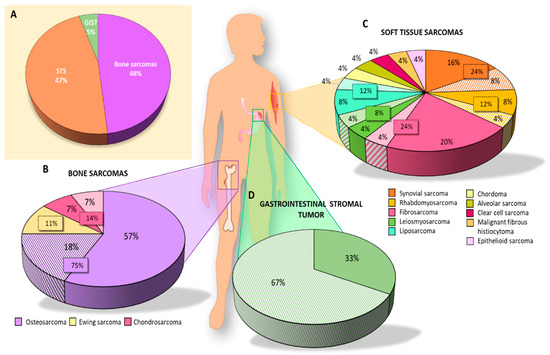

The number of articles published on CSCs in sarcomas decreased over time. The years with the highest number of publications were 2012 and 2015 (6 and 7 per year, respectively), whereas the fewest publications were observed in 2018 (1 article) and 2019 (no articles) (Figure 2). Analysis of the type of sarcoma studied in the 35 articles published in the last 10 years revealed that 22 articles focused on BS, 7 on STS, and 3 on both types (i.e., STS and BS). GISTs have been less extensively studied with only 3 articles published in the last decade. Interestingly, more articles were published on BS than on STS, except in 2013 and 2014. However, articles on STS included a larger number of different subtypes, and the percentage of STS was similar to that of BS studied (Figure 3A). In the category of BS, most studies focused on osteosarcoma (75%), while on STS, synovial sarcoma (24%) and fibrosarcoma (24%) were the most studied subtypes, followed by rhabdomyosarcoma (12%) and liposarcoma (12%) (Figure 3B,C).

Figure 2.

Number of articles published per year in the last decade on sarcomas, classified as BS, STS, or GIST.

Figure 3.

Graphic representation of the articles analyzed in this systematic review. Percentage of articles studying (A) each type of sarcoma; (B) each subtype of BS; (C) each subtype of STS; (D) GIST. Solid colors represent the results of articles in which CSCs were isolated using different techniques and the striped colors represent the results of articles on biomarker expression without isolation of CSCs.

3.1. Different In Vitro Techniques for Isolating CSCs

3.1.1. Bone Sarcoma

Of the 35 articles selected for this systematic review, 27 studied CSC markers for BS. Specifically, 21 isolated CSCs: 16 from osteosarcoma, 2 from chondrosarcoma, and 3 from Ewing’s sarcoma (Table 1). The percentage of the total studies collected on BS was 57%, 7%, and 11%, respectively (Figure 3B), with osteosarcoma being the most studied BS for isolating CSCs in vitro.

CSC markers in osteosarcoma were studied in 16 articles (Table 1). The most commonly used osteosarcoma cell lines were MG63, Saos-2, and U2OS, although most articles (10) utilized primary tumor samples from osteosarcoma patients to isolate CSCs. In addition, one article obtained samples from osteosarcoma lung metastasis [29]. Only four studies specified that patients had not been previously treated with chemotherapy [29,30,32,35], while patients underwent chemotherapy and radiotherapy in one study [46].

The most frequently used CSC isolation technique in osteosarcoma was Fluorescent-Activated Cell Sorter (FACS) combined with subsequent culture of the isolated and sorted cells in induction media for maintenance [25,27,31,37,46]. Four articles carried out the sphere formation assay using an induction culture medium [24,28,35,36], one article used FACS only without induction medium [33], two articles used the Magnetic-Activated Cell Sorting (MACS) technique and then induction medium [26,29], one article used MACS without induction medium [34], and finally, the Side Population (SP) technique with subsequent induction medium was used in three articles [13,30,32].

In the case of FACS and MACS techniques which were used in nine osteosarcoma articles, CSC markers were necessary for their isolation. The most commonly used method (three/nine articles) was double labeling with CD133 and CD44 [26,27,29], followed by labeling with CD133 only [34]. Other markers used were CD24 [25], CD49f [33], Sox2 together with Sca-1 [37] and CD109 [46]. Of the 13 osteosarcoma articles using induction and sphere-forming media, all utilized serum-free medium supplemented with factors, with EGF (epidermal growth factor) and FGF (fibroblast growth factor) being the most important, although in varying proportions. The most frequently used base medium was DMEM/F12, with a total of nine articles. One article used Ham’s F12 [24], while DMEM [27], RPMI [35], and N2B27 [37] were used depending on the cell line.

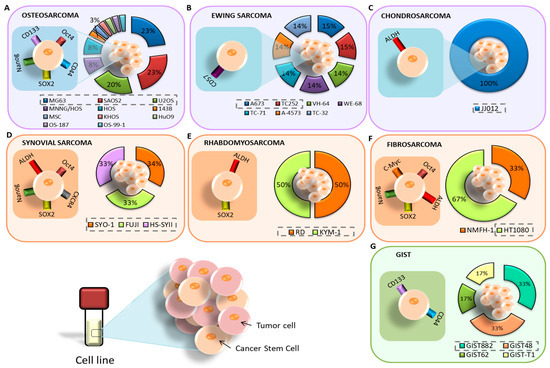

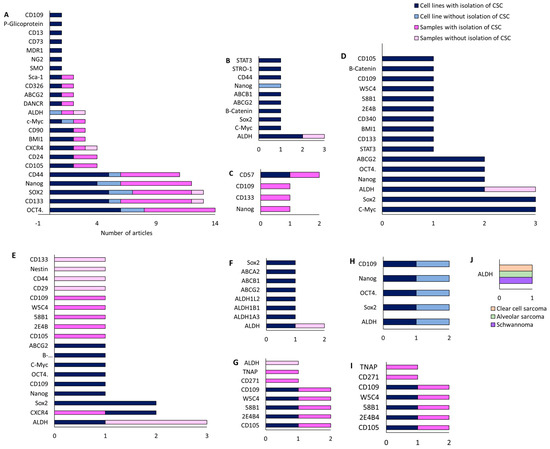

All articles conducted characterization of CSCs after isolation. The most commonly used methods were RT-qPCR, Western blot, flow cytometry, IF, and ALDEFLUOR assay to check the expression of CSC markers in the isolated cells. In addition, in vivo tumorigenicity assays were performed. The most highly expressed markers of CSCs isolated from established cell lines were Oct4, CD133, SOX2, Nanog, and CD44 (Figure 4A). On the other hand, the most highly expressed markers in CSCs isolated from primary tumor samples from patients coincided with those mentioned for the cell lines. In the case of the only article that studied pulmonary metastasis, the CD133 and CD44 markers coincided in both the cell lines and patient samples [29]. Furthermore, several CSC markers have been associated with poor patient prognosis, including CD24 [25], DANCR [27], and CD49 [33]. Some articles also examined the modulation of certain markers after treatment. Zhou et al. [25] observed an increase in CD24 expression after treatment with Cisplatin, Epirubicin, and Hydrochloride. Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) reduced several CSC markers, namely CD44, CD133, SOX2, OCT4, c-Myc, and Nanog (CD133+/CD44+) [26]. Co-culture with mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) also increased the expression of SOX2, OCT4, Nanog, and CXCR4 markers [28]. CSCs with high expression of CD248, CD133, OCT4, Nanog, and Nestin were more resistant to Doxorubicin, Cisplatin, and Methotrexate [30]. Verapamil treatment increased the sensitivity of CSCs to Doxorubicin [36].

Figure 4.

Cell lines and markers used for the study of CSCs in BS: (A) osteosarcoma; (B) Ewing’s sarcoma; (C) chondrosarcoma. Cell lines and markers used for the study of CSCs in STS: (D) synovial sarcoma; (E) rhabdomyosarcoma; (F) fibrosarcoma. (G) Cell lines and markers used for the study of CSCs in GIST.

Ewing’s sarcoma was the second most studied sarcoma subtype in terms of CSC isolation, with a total of three articles (11% of all BS) included in this review. There was no common cell line among these articles. Sphere formation using induction medium was the primary method of CSC isolation in two articles [38,39], while FACS isolation with subsequent culture in induction medium was applied in Emori et al. [46], using the CD109 marker. The medium composition was DMEM/F12 in two articles and IMDM in one [38]. The most common methods used for characterization were FACS, in vivo tumorigenicity, and RT-PCR, although SP and ALDEFLUOR assays were also applied. In Ewing’s sarcoma, CD57 was the most highly expressed marker in CSCs derived from patient samples [39], followed by OCT4 and Nanog [38] (Figure 4B). Additionally, the CD109 marker was expressed in both cell lines and patient samples [46].

Chondrosarcoma was the least studied BS, with a total of two articles (7% of all BS) included in this review. In both cases, FACS isolation was carried out using the ALDH marker [40,48], but only Granger et al. [40] subsequently cultured the isolated cells in induction medium. Common characterization methods included Western blot and RT-PCR, while IF was also applied in Lohberger et al. [48]. Both articles only used established cell lines. Granger et al. [40] found high expression of ALDH, CD44, STRO1, and STAT3 in the JJ012 line, while Lohberger et al. [48] found a high expression of ALDH, c-Myc, SOX2, B-Catenin, ABCG2, and ABCB1 in the SW1353 cell line (Figure 4C). Additionally, ALDH+ CSCs were found to be resistant to chemotherapy in Lohberger et al., 2012 [48], while treatment with PRP-1 (proline-rich polypeptide-1) had no effect in Granger et al. [40].

3.1.2. Soft Tissue Sarcomas (STS)

Twenty-four of the 35 articles selected for this review studied CSC markers in STS. Of these, 16 articles isolated CSCs, 4 of which focused on synovial sarcoma (16% of all STS), 2 on rhabdomyosarcoma (8%), 4 on fibrosarcoma (16%), 1 on epithelioid sarcoma (4%), 1 on malignant fibrous histiocytoma, 1 on leiomyosarcoma (4%), 2 on liposarcoma (8%), and 1 on chordoma (4%). Synovial sarcoma and fibrosarcoma were the most studied STS in terms of CSC isolation.

The isolation of CSCs from synovial sarcoma was described in four articles (Table 1). The most commonly used cell line was Fuji. FACS with induction media and the CD109 [46] and CD271 markers [47] were the most commonly used isolation methods, followed by FACS without induction media with the ALDH marker [48]. Sphere formation assay was also employed by Kimura et al. [41]. The induction medium used in all three articles was based on DMEM/F12. Characterization methods included RT-PCR, flow cytometry, Western blot, immunohistochemistry (IHC), and IF. From already established cell lines, Kimura et al. [41] found increased expression of the markers Nanog, Oct4, SOX2, and CXCR4 in CSCs from SYO-I, Fuji, and HS-SYII lines. Lohberger et al. [48] used the SW982 line, whose CSCs expressed ALDH, c-Myc, Sox2, B-catenin, and ABCG2 (Figure 4D). Emori et al. [46] did not find expression of CD119 in FUJI and YaFuss. One article showed expression of the unusual markers CD105, 2E4B4, 58B1, W5C4, and CD109 in both the SW982 line and in primary tumor samples from patients (Figure 5). In addition, the tumors expressed CD271 and TNAP [47]. Regarding chemotherapy treatment, SW982 ALDH+ cells were found to be resistant to Doxorubicin [48]. Furthermore, CD271+ cells derived from patient primary tumors and the SW982 line were found to be resistant to Doxorubicin and Epirubicin [47].

Figure 5.

Representation of the most commonly used CSC markers in samples derived from patients with BS, STS and GIST: (A) CSC isolation; (B) histological techniques.

Fibrosarcoma, along with synovial sarcoma, was one of the most studied STS in the articles reviewed. Table 1 lists four articles on this topic. The most commonly used cell line was HT1080 [44,47] (Figure 4F). Three articles used FACS in different ways: with the ALDH marker and induction medium [43], with ALDH without subsequent culture in induction medium [48], or with the CD271 marker and subsequent induction medium [47]. MACS with the CD133 marker and subsequent induction medium was used in Feng et al., 2013 [44]. RPMI was used as induction medium in Li et al. [43], while the rest used DMEM/F12. The prevailing characterization methods were RT-PCR, Western blot, in vivo tumorigenesis, IF, and IHC. Only one article used primary tumor samples from patients in the study. Lohberger et al. [48] used the SW982 and SW684 lines, Wirths et al. [47] used SW982, SE872, and HT1080, Feng et al. [44] used HT1080, and Li et al. [43] used the NMFH-1 line. Three articles found a high expression of c-Myc and SOX2 markers in CSCs. Nanog, Oct4, and ABCG2 markers were found in two articles. Other markers expressed in cell lines include STAT3, CD133, BMi-1, ALDH, and B-catenin. Notably, BMi-1 was overexpressed in CD133+ CSCs in HT1080 [44], but not in ALDH+ NMFH-1 cells [43]. Both ALDH+ and CD133+ cells mentioned were found to be resistant to treatment with Doxorubicin and Cisplatin. Additionally, CD105, 2E4B4, 58B1, W5C4, and CD109 were expressed in cell lines and samples.

Isolation of CSCs from rhabdomyosarcoma and liposarcoma was carried out in two articles each once (Table 1). The studies used different cell lines: TE-671 [48], and RD and KYM-1 [42] (Figure 4E). None of the studies used patient samples, but both used FACS-based CSC isolation methods with the ALDH marker. The common characterization methods were RT-PCR, Western blot, IF, and in vivo tumorigenicity. One of the articles reported no results using the cellular line of rhabdomyosarcoma [48], and the other found overexpression of ALDHA3, ALDHB1, ALDHL2, SOX2, ABCG2, ABCB1, and ABCA2 markers. Additionally, ALDH+ cells were found to be more resistant to treatment with Vincristine, Cyclophosphamide, and Etoposide. Table 1 includes two articles that evaluated CSC isolation in liposarcoma [47,48]. Both studies used the SW872 cell line. Wirths et al. [47] isolated CSCs using FACS (CD271) and subsequently maintained the cells in induction medium. They characterized CSCs using IHC. On the other hand, Lohberger et al. [48] used FACS (ALDH) for isolation and IF Western blot and RT-PCR for characterization. The markers studied in both articles did not coincide. In Wirths et al. [47], both CSCs derived from the cell line and primary tumor samples from patients expressed CD105, 2E4B4, 58B1, W5C4, and CD109. The primary tumor tissue also expressed CD271 and TNAP, with CD271+ cells being associated with Doxorubicin resistance. On the other hand, Lohberger et al. [48] only isolated CSCs from the cell line, and these cells expressed ALDH, c-Myc, Sox2, B-catenin, and ABCG2 markers.

Finally, one article related to the isolation of CSCs from epithelioid sarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, leiomyosarcoma and chordoma was found. Table 1 presents a single article reporting the isolation of CSCs in epithelioid sarcoma [46]. The study employed two cell lines, FU-EPS-1 and VA-ES-BJ, in addition to primary tumor samples. Isolation of CSCs was carried out using FACS with the CD109 marker and subsequent culture in induction medium. CSCs were characterized using RT-PCR and the ALDEFLUOR assay. The CSCs obtained from the established cell lines and tumor samples expressed ALDH, SOX2, OCT4, Nanog, and CD109 markers. It is worth noting that the expression of CD109 correlated with low survival. On the other hand, the study by Emori et al. [46] used the malignant fibrous histiocytoma cell lines, MFH2033 and MFH2004, in addition to primary tumor samples. Isolation of CSCs was carried out using FACS with the CD109 marker and subsequent culture in induction medium. The CSCs were characterized using RT-PCR and the ALDEFLUOR assay. The CSCs obtained from the cell lines and tumor samples expressed CD109, which also correlated with poor survival. In relation to leiomyosarcoma, Table 1 includes the only article that investigated this tumor [47]. The study employed the SK-LMS1l cell line and tissue samples from the primary tumor. Isolation of CSCs was carried out using FACS with CD271, followed by induction media and characterization with IHC. The CSCs obtained from the cell lines and tumor samples expressed CD105, 2E4B4, 58B1, W5C4, and CD109 markers. The primary tumor tissue also expressed CD271 and TNAP, with CD271+ cells being associated with Doxorubicin resistance. Finally, Lohberger et al. [48] studied chordoma using the MUG-Chor-1 cell line and did not use patient samples. Isolation of CSCs was carried out using FACS with ALDH and subsequent characterization of CSCs with IF, Western blot, and RT-PCR. The isolated CSCs expressed ALDH, Sox2, cMyc, β-catenin, and ABCG2 markers.

3.1.3. GIST

Only one of the three articles (33%) on GIST reported the isolation of CSCs (Figure 3D) [45]. The study employed four cell lines, namely, GIST882, GIST48, GIST62, and GIST-T1 (Figure 4G). Isolation of CSCs was performed by FACS using CD133 and CD44 markers, followed by characterization using IF, flow cytometry, and SP assay. The CSCs showed high expression of CD44 and CD133 markers, especially in GIST located in the stomach. The high expression of these markers was associated with resistance to Imatinib.

3.2. CSC Markers in Histological Samples

3.2.1. Bone Sarcoma

This systematic review includes 27 articles on BS, of which 8 only measured CSC marker expression on the entire cell population without performing in vitro treatment on cell lines or patient tumor samples. Specifically, 18% of the articles focused on osteosarcoma, and 7% on chondrosarcoma. No articles were found on Ewing’s sarcoma. The results are summarized in Table 2.

Analysis of CSC markers in osteosarcoma without isolation was found in four articles (Table 2). The commonly used cell lines were MG63 and U2OS, while two articles only used patient samples [49,57]. One article exclusively used patient samples [51]. The marker expression analysis was primarily based on Western blot, followed by RT-qPCR. One article performed FACS and ALDEFLUOR assay [57], and another article used IHC [49]. CD133 and CXR4 markers were expressed in 26% and 36% of the samples, respectively, and were found to be correlated with pulmonary metastasis [49]. In contrast, Avdonkina et al. [57] did not observe CD133 expression. Moreover, the modulation of markers by the SOX2lncRNA gene was studied; its overexpression increased OCT4, ALDH, CD133, and CD44 markers in Saos-2 cells, while the opposite was observed in U2OS cells. Overexpression of SOX2lncRNA was also associated with poor survival [50] (Figure 6A). Additionally, Zoledronate-resistant cells showed high expression of Nanog, c-Myc, Oct-4, and Sox2 markers [51].

Figure 6.

Number of articles that investigated CSC markers in cell lines after the CSC isolation process, in cell lines without CSC isolation, in patient samples after CSC isolation, and in patient samples without CSC isolation for different STS subtypes: (A) osteosarcoma; (B) chondrosarcoma; and (C) Ewing’s sarcoma; (D) fibrosarcoma; (E) synovial sarcoma; (F) rhabdomyosarcoma; (G) liposarcoma; (H) epithelioid sarcoma and malignant fibrous histiocytoma; (I) leiomyosarcoma; and (J) clear cell sarcoma, alveolar sarcoma, and schwannoma.

Only one article studied CSC markers in chondrosarcoma [52] using the JJ012 cell line, without using patient samples. The authors analyzed Nanog expression using Western blot. Comparison of the baseline with the line after PRP-1 treatment revealed a significant decrease in the Nanog marker.

3.2.2. Soft Tissue Sarcoma

Synovial sarcoma was studied in two articles focusing solely on patient samples and analyzing the markers using IHC [57] or FACS with CD133 and the ALDEFLUOR assay [53]. According to this study, CD133 was the most frequently expressed marker in 85% of the samples, followed by CD24 and CD44 in 55%, Nestin in 30%, and ALDH in 25%. ALDH was found to be correlated with poor survival. Interestingly, ALDH was expressed more frequently in STS than in BS [57]. On the other hand, only one article investigated undifferentiated cardiac sarcoma [54]. The study analyzed CD44 and OCT3/4 markers in patient samples using BS, and only CD44 expression was detected. Finally, we identified one article that studied several types of STS, including liposarcoma, fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, schwannoma, alveolar sarcoma, clear cell sarcoma, and dermatofibrosarcoma [57]. The study only analyzed patient samples using FACS and the ALDEFUOR assay. The results showed a higher expression of ALDH compared to BS, but no difference in CD133.

3.2.3. GIST

GIST was investigated in two articles. One study analyzed GIST882 and GIST48b cell lines, as well as patient samples [55], while the other only analyzed patient samples [56]. Immunohistochemistry was the main method used to investigate marker expression. The study by Geddert et al. [55] found that treatment with 5-aza-dC (5-aza-2’-deoxycytidine) reduced CD133 reactive hypomethylation and inversely correlated CD133 expression with survival, while directly correlating CD133 expression with gastric localization and KIT mutation. The relationship between KIT mutation and CD133 expression was also supported in the study by Bozzi et al. [56], as well as CD90, CD44, and CD34 markers. The expression of Kit, CD133, CD90, and CD34 was found to decrease or increase with the combination of KIT mutation and Imatinib treatment.

4. Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to provide a detailed description of the existing literature on the expression of CSC markers in sarcomas, both in vitro and in the heterogeneous population of cells present in samples. To our knowledge, this is the first systematic review of CSC markers in sarcomas. After screening, 35 articles were selected. A great imbalance was found when comparing the types of sarcomas studied in each article. Specifically, 22 articles focused only on BS, while 7 focused on STS. Three articles studied both BS and STS, and the remaining studied GIST. These data do not agree with the classification of sarcomas since the largest group is composed of STS with 80%, followed by BS with 15% and GIST with 5% [3,4]. Therefore, although more research is needed in general in this field, specifically more studies are needed in STS.

Focusing on STS, the most frequent subtype in children is rhabdomyosarcoma [58]. It is a very aggressive tumor with a skeletal muscle phenotype [59]. Two subtypes of rhabdomyosarcoma have been described: alveolar and embryonal, with the former being much more aggressive [60]. They present a 5-year survival rate of 28.9% and 74%, respectively [61]. On the other hand, the most frequent BS is osteosarcoma, which presents a peak incidence in adolescents, between 15 and 18 years of age, and another in adults at 42 years of age [62]. The 5-year survival rate in localized osteosarcoma is 65% and less than 20% in metastatic disease [63]. In this systematic review, only three articles on rhabdomyosarcoma have been found, so more studies are needed due to its high frequency. However, osteosarcoma is the most studied BS, which is consistent with its high prevalence.

This review specifically focuses on articles studying CSC markers in sarcomas. CSCs are defined as a subpopulation of cells in the tumor mass with the capacity for tumor initiation, progression, metastasis, and drug resistance [64,65]. Currently, the strategy followed by most studies is to first isolate CSCs and then analyze the expression levels of certain markers in these cells. CSCs can be isolated from existing cell lines or by generating cell cultures derived from patient tumor samples, which is not always an effective technique. In fact, the success rate in establishing cultures derived from patient samples is 82% in bone tumors and 68% in STS [66]. There are different techniques for the isolation of CSCs based on their unique characteristics, including drug resistance, dye explosion or SP assay, separation using surface markers with FACS or MACS, or ALDH activity. CSCs can also be enriched due to their ability to form tumor spheres in the absence of adherence and serum. However, there was no common method used in the studies reviewed, and even when the same method was used in sarcomas, there was much disparity in the methodology used. The CSC culture medium presented very different compositions, and no common marker was found to be used for isolation by FACS or MACS. In general, these processes select a population of CSCs with a specific characteristic, such as a particular marker, being separated from other subpopulations of CSCs with less expression of the same marker. Therefore, this CSC population is distanced from the heterogeneous population present in tumors in vivo. In conclusion, the studies were not carried out in the most appropriate way. Another strategy is based on analyzing CSC markers on the entire tumor population, either on in vitro cultures or on tumor samples using IF, IHC, or qPCR. This way, the entire CSC population present in the tumor can be analyzed. Of the 35 articles reviewed, only 9 used this approach, which is the most novel.

On the other hand, few studies analyzed the expression of CSC markers in tumor samples, so more studies are needed. It is necessary to compare the results of marker expression in isolated CSCs and in the whole cell population since the common markers could be the ones that should be used to corroborate that CSCs have been isolated in vitro similar to those present in the clinic. When analyzing the results of the included studies, the different homogeneity/heterogeneity between the markers detected in the different techniques used in the isolation of CSCs is very interesting. For example, in the case of GIST, CD44 and CD133 are constant in CSCs of this type of tumor, both in isolation using induction media and in biopsy studies. However, in the case of osteosarcoma and synovial sarcoma, a different marker profile can be seen in the case of biopsy studies compared to studies with induction media on cells. Thus, in the case of osteosarcoma, CD44 and Nanog are outstanding markers when isolation is carried out with induction media, while markers such as ALDH and CXCR5 are found on biopsy samples (Figure 6). Other markers such as CD133 and SOX2 are constant between studies. When we consider synovial sarcoma, CD44 is detected in biopsies but not in studies with induction media on the populations obtained. However, these results could be due either to a difference between the induced CSCs and those existing in the primary tumors, or it is possible that there is a bias related to the type of marker studied in each case, and the non-existence of results is due to the fact that such studies have not been carried out.

One of the most important findings from the reviewed studies is that ALDH is shown to be an important pan-CSC marker in the case of sarcomas, since it has been detected as positive in a multitude of sarcomas analyzed. Additionally, the use of chemotherapy seems to select some populations of CSCs with respect to others, with subpopulations of greater or lesser chemosensitivity and aggressiveness within the same CSCs analyzed, which could help to personalize therapies. However, there is a general lack of studies on which markers are more sensitive to different chemotherapeutic regimens. Only 30 articles in this review employed the use of chemotherapy treatment. This is important because it would enable us to determine which chemotherapy or radiotherapy to use according to the expression of each specific marker and to study resistance.

Our results are based on studies of primary and metastatic tumor samples, with the aim of studying CSCs to achieve a treatment to prevent metastasis or otherwise prevent further spread of the disease. Other reviews in this field focus on more novel aspects such as the study of markers in circulating CSCs in blood, with the aim of developing a new therapeutic target for these circulating cells responsible for metastasis. These studies also highlight the significant problem that we are addressing and show that there is also great heterogeneity in the use of CSC markers in circulating cells [67,68,69,70,71,72]. Ultimately, the goal in the future is to achieve personalized medicine.

5. Conclusions

The role of CSCs in the prognosis of sarcomas has gained great importance in recent years. However, currently very few studies have investigated the expression of CSC markers in the diverse range of existing sarcoma subtypes. Therefore, further research is urgently needed to identify more sensitive CSC biomarkers and to establish a comprehensive set of markers that can accurately characterize CSCs in sarcomas. Ultimately, this will lead to the development of personalized treatments tailored to the specific CSC markers present in each patient’s tumor.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.P., C.M. (Cristina Mesas) and K.D.; methodology, M.A.C. and C.M. (Cristina Mesas).; software, F.Q.; validation, G.P. and R.O.; investigation, M.A.C., C.M. (Cristina Mesas) and K.D.; resources, R.O.; writing—original draft preparation, M.A.C., C.M. (Cristina Mesas) and K.D.; writing—review and editing, J.P. and C.M. (Consolacion Melguizo); visualization, K.D. and R.O.; supervision, J.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by funds from group CTS-107 (Andalusian Government).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Center of Scientific Instrumentation personnel of the University of Granada for technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Fletcher, C.; Bridge, J.A.; Hogendoorn, P.C.W.; Mertens, F. WHO Classification of Tumours of Soft Tissue and Bone; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Siegel, R.L.; Miller, K.D.; Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018, 68, 7–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Occupational Cancers; Anttila, S., Boffetta, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Yue, C. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor. J. Gastrointest. Oncol. 2012, 3, 189–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arifi, S.; Belbaraka, R.; Rahhali, R.; Ismaili, N. Treatment of Adult Soft Tissue Sarcomas: An Overview. Rare Cancers Ther. 2015, 3, 69–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harting, M.T.; Blakely, M.L. Management of osteosarcoma pulmonary metastases. Semin. Pediatr. Surg. 2006, 15, 25–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heymann, M.-F.; Brown, H.K.; Heymann, D. Drugs in early clinical development for the treatment of osteosarcoma. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2016, 25, 1265–1280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mialou, V.; Philip, T.; Kalifa, C.; Perol, D.; Gentet, J.-C.; Marec-Berard, P.; Pacquement, H.; Chastagner, P.; Defaschelles, A.-S.; Hartmann, O. Metastatic osteosarcoma at diagnosis: Prognostic Factors and Long-Term Outcome--the French Pediatric Experience. Cancer 2005, 104, 1100–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellez-Gabriel, M.; Heymann, M.-F.; Heymann, D. Circulating Tumor Cells as a Tool for Assessing Tumor Heterogeneity. Theranostics 2019, 9, 4580–4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourneaux, B.; Bourdon, A.; Dadone, B.; Lucchesi, C.; Daigle, S.R.; Richard, E.; Laroche-Clary, A.; Le Loarer, F.; Italiano, A. Identifying and targeting cancer stem cells in leiomyosarcoma: Prognostic impact and role to overcome secondary resistance to PI3K/mTOR inhibition. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2019, 12, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatina, J.; Kripnerova, M.; Houfkova, K.; Pesta, M.; Kuncova, J.; Sana, J.; Slaby, O.; Rodríguez, R. Sarcoma Stem Cell Heterogeneity. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1123, 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallette, F.M.; Olivier, C.; Lézot, F.; Oliver, L.; Cochonneau, D.; Lalier, L.; Cartron, P.-F.; Heymann, D. Dormant, quiescent, tolerant and persister cells: Four synonyms for the same target in cancer. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2019, 162, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Yan, M.; Zhang, R.; Li, J.; Luo, Z. Side population cells isolated from human osteosarcoma are enriched with tumor-initiating cells. Cancer Sci. 2011, 102, 1774–1781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Damerell, V.; Pepper, M.S.; Prince, S. Molecular mechanisms underpinning sarcomas and implications for current and future therapy. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2021, 6, 246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adhikari, A.S.; Agarwal, N.; Wood, B.M.; Porretta, C.; Ruiz, B.; Pochampally, R.R.; Iwakuma, T. CD117 and Stro-1 Identify Osteosarcoma Tumor-Initiating Cells Associated with Metastasis and Drug Resistance. Cancer Res. 2010, 70, 4602–4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu-Roy, U.; Bayin, N.S.; Rattanakorn, K.; Han, E.; Placantonakis, D.G.; Mansukhani, A.; Basilico, C. Sox2 antagonizes the Hippo pathway to maintain stemness in cancer cells. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 6411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greco, N.; Schott, T.; Mu, X.; Rothenberg, A.; Voigt, C.; III, R.L.M.; Goodman, M.; Huard, J.; Weiss, K.R. ALDH Activity Correlates with Metastatic Potential in Primary Sarcomas of Bone. J. Cancer Ther. 2014, 5, 331–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tirino, V.; Desiderio, V.; Paino, F.; De Rosa, A.; Papaccio, F.; Fazioli, F.; Pirozzi, G.; Papaccio, G. Human primary bone sarcomas contain CD133+ cancer stem cells displaying high tumorigenicity in vivo. FASEB J. 2011, 25, 2022–2030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiavone, K.; Garnier, D.; Heymann, M.-F.; Heymann, D. The Heterogeneity of Osteosarcoma: The Role Played by Cancer Stem Cells. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2019, 1139, 187–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, M.; Avnet, S.; Bonuccelli, G.; Eramo, A.; DE Maria, R.; Gambarotti, M.; Gamberi, G.; Baldini, N. Sphere-forming cell subsets with cancer stem cell properties in human musculoskeletal sarcomas. Int. J. Oncol. 2013, 43, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muka, T.; Glisic, M.; Milic, J.; Verhoog, S.; Bohlius, J.; Bramer, W.; Chowdhury, R.; Franco, O.H. A 24-step guide on how to design, conduct, and successfully publish a systematic review and meta-analysis in medical research. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2020, 35, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Száva-Kováts, E. Unfounded attribution of the “half-life” index-number of literature obsolescence to Burton and Kebler: A literature science study. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2002, 53, 1098–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Weighted kappa: Nominal scale agreement provision for scaled disagreement or partial credit. Psychol. Bull. 1968, 70, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmini, G.; Romagnoli, C.; Donati, S.; Zonefrati, R.; Galli, G.; Marini, F.; Iantomasi, T.; Aldinucci, A.; Leoncini, G.; Franchi, A.; et al. Analysis of a Preliminary microRNA Expression Signature in a Human Telangiectatic Osteogenic Sarcoma Cancer Cell Line. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Kuang, M.; Wang, X.; Jia, Q.; Cao, J.; Hu, J.; Wu, S.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, J. The CD24+ cell subset promotes invasion and metastasis in human osteosarcoma. Ebiomedicine 2020, 51, 102598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, W.; Chen, D.; Zhu, K. SOX2OT variant 7 contributes to the synergistic interaction between EGCG and Doxorubicin to kill osteosarcoma via autophagy and stemness inhibition. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res. 2018, 37, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, N.; Wang, X.; Xie, X.; Liao, Y.; Liu, N.; Liu, J.; Miao, N.; Shen, J.; Peng, T. lncRNA DANCR promotes tumor progression and cancer stemness features in osteosarcoma by upregulating AXL via miR-33a-5p inhibition. Cancer Lett. 2017, 405, 46–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortini, M.; Massa, A.; Avnet, S.; Bonuccelli, G.; Baldini, N. Tumor-Activated Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Promote Osteosarcoma Stemness and Migratory Potential via IL-6 Secretion. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0166500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, A.; Yang, X.; Huang, Y.; Feng, T.; Wang, Y.; Sun, Y.; Shen, Z.; Yao, Y. CD133+CD44+Cells Mediate in the Lung Metastasis of Osteosarcoma. J. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 116, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.-X.; Liao, G.-J.; Liu, K.-G.; Jian, H. Endosialin-expressing bone sarcoma stem-like cells are highly tumor-initiating and invasive. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5665–5670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, M.; Xiong, M.; Zhang, X.; Cai, G.; Chen, H.; Zeng, Q.; Yu, Z. Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) nanoparticles conjugated with CD133 aptamers for targeted salinomycin delivery to CD133+ osteosarcoma cancer stem cells. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 2537–2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.-J.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Qiao, L.-X.; Jin, C.-L.; Tian, J.; Li, Q.-S. Aberrant Wnt/β-catenin signaling and elevated expression of stem cell proteins are associated with osteosarcoma side population cells of high tumorigenicity. Mol. Med. Rep. 2015, 12, 5042–5048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penfornis, P.; Cai, D.Z.; Harris, M.R.; Walker, R.; Licini, D.; Fernandes, J.D.A.; Orr, G.; Koganti, T.; Hicks, C.; Induru, S.; et al. High CD49f expression is associated with osteosarcoma tumor progression: A study using patient-derived primary cell cultures. Cancer Med. 2014, 3, 796–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhong, X.-Y.; Li, Z.-Y.; Cai, J.-F.; Zou, L.; Li, J.-M.; Yang, T.; Liu, W. CD133 expression in osteosarcoma and derivation of CD133+ cells. Mol. Med. Rep. 2012, 7, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, V.; Hose, C.D.; Monks, A.; Nagashima, K.; Han, B.; Newton, D.L.; Millione, A.; Shah, J.; Hollingshead, M.G.; Hite, K.M.; et al. Identification of CBX3 and ABCA5 as Putative Biomarkers for Tumor Stem Cells in Osteosarcoma. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e41401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins-Neves, S.R.; Lopes, O.; Carmo, A.D.; Paiva, A.A.; Simões, P.C.P.S.S.; Abrunhosa, A.J.; Gomes, C.M.F. Therapeutic implications of an enriched cancer stem-like cell population in a human osteosarcoma cell line. BMC Cancer 2012, 12, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu-Roy, U.; Seo, E.; Ramanathapuram, L.; Rapp, T.B.; Perry, J.A.; Orkin, S.H.; Mansukhani, A.; Basilico, C. Sox2 maintains self renewal of tumor-initiating cells in osteosarcomas. Oncogene 2012, 31, 2270–2282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornaz-Buros, S.; Riggi, N.; DeVito, C.; Sarre, A.; Letovanec, I.; Provero, P.; Stamenkovic, I. Targeting Cancer Stem–like Cells as an Approach to Defeating Cellular Heterogeneity in Ewing Sarcoma. Cancer Res. 2014, 74, 6610–6622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leuchte, K.; Altvater, B.; Hoffschlag, S.; Potratz, J.; Meltzer, J.; Clemens, D.; Luecke, A.; Hardes, J.; Dirksen, U.; Juergens, H.; et al. Anchorage-independent growth of Ewing sarcoma cells under serum-free conditions is not associated with stem-cell like phenotype and function. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 32, 845–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.J.; Hoyt, A.K.; Moran, A.; Becker, B.; Saigh, S.; Conway, S.A.; Brown, J.; Galoian, K. Cancer stem cells as a therapeutic target in 3D tumor models of human chondrosarcoma: An encouraging future for proline rich polypeptide-1. Mol. Med. Rep. 2020, 22, 3747–3758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, T.; Wang, L.; Tabu, K.; Tsuda, M.; Tanino, M.; Maekawa, A.; Nishihara, H.; Hiraga, H.; Taga, T.; Oda, Y.; et al. Identification and analysis of CXCR4-positive synovial sarcoma-initiating cells. Oncogene 2015, 35, 3932–3943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakahata, K.; Uehara, S.; Nishikawa, S.; Kawatsu, M.; Zenitani, M.; Oue, T.; Okuyama, H. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1) Is a Potential Marker for Cancer Stem Cells in Embryonal Rhabdomyosarcoma. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Zhang, T.; Gu, W.; Li, P.; Cheng, X.; Tong, T.; Wang, W. The ALDH1+ subpopulation of the human NMFH-1 cell line exhibits cancer stem-like characteristics. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 2291–2298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, B.-H.; Liu, A.-G.; Gu, W.-G.; Deng, L.; Cheng, X.-G.; Tong, T.-J.; Zhang, H.-Z. CD133+ subpopulation of the HT1080 human fibrosarcoma cell line exhibits cancer stem-like characteristics. Oncol. Rep. 2013, 30, 815–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, J.; Guo, T.; Zhang, L.; Qin, L.-X.; Singer, S.; Maki, R.G.; Taguchi, T.; DeMatteo, R.; Besmer, P.; Antonescu, C.R. CD133 and CD44 are universally overexpressed in GIST and do not represent cancer stem cell markers. Genes Chromosom. Cancer 2011, 51, 186–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emori, M.; Tsukahara, T.; Murase, M.; Kano, M.; Murata, K.; Takahashi, A.; Kubo, T.; Asanuma, H.; Yasuda, K.; Kochin, V.; et al. High Expression of CD109 Antigen Regulates the Phenotype of Cancer Stem-Like Cells/Cancer-Initiating Cells in the Novel Epithelioid Sarcoma Cell Line ESX and Is Related to Poor Prognosis of Soft Tissue Sarcoma. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e84187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirths, S.; Malenke, E.; Kluba, T.; Rieger, S.; Müller, M.R.; Schleicher, S.; von Weyhern, C.H.; Nagl, F.; Fend, F.; Vogel, W.; et al. Shared Cell Surface Marker Expression in Mesenchymal Stem Cells and Adult Sarcomas. STEM CELLS Transl. Med. 2012, 2, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohberger, B.; Rinner, B.; Stuendl, N.; Absenger, M.; Liegl-Atzwanger, B.; Walzer, S.M.; Windhager, R.; Leithner, A. Aldehyde Dehydrogenase 1, a Potential Marker for Cancer Stem Cells in Human Sarcoma. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mardani, A.; Gheytanchi, E.; Mousavie, S.H.; Jabari, Z.M.; Shooshtarizadeh, T. Clinical Significance of Cancer Stem Cell Markers CD133 and CXCR4 in Osteosarcomas. Asian Pac. J. Cancer Prev. 2020, 21, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tan, M.; Chen, G.; Li, Z.; Lu, X. LncRNA SOX2-OT is a novel prognostic biomarker for osteosarcoma patients and regulates osteosarcoma cells proliferation and motility through modulating SOX2. IUBMB Life 2017, 69, 867–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshiyama, A.; Morii, T.; Ohtsuka, K.; Ohnishi, H.; Tajima, T.; Aoyagi, T.; Mochizuki, K.; Satomi, K.; Ichimura, S. Development of Stemness in Cancer Cell Lines Resistant to the Anticancer Effects of Zoledronic Acid. Anticancer. Res. 2016, 36, 625–631. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Galoian, K.; Qureshi, A.; D’ippolito, G.; Schiller, P.C.; Molinari, M.; Johnstone, A.L.; Brothers, S.P.; Paz, A.C.; Temple, H.T. Epigenetic regulation of embryonic stem cell marker miR302C in human chondrosarcoma as determinant of antiproliferative activity of proline-rich polypeptide 1. Int. J. Oncol. 2015, 47, 465–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, D.; Qi, Y.; Liu, R.; Li, S.; Zou, H.; Lan, J.; Ju, X.; Jiang, J.; Liang, W.; et al. Evaluation of expression of cancer stem cell markers and fusion gene in synovial sarcoma: Insights into histogenesis and pathogenesis. Oncol. Rep. 2017, 37, 3351–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hegyi, L.; Thway, K.; Fisher, C.; Sheppard, M.N. Primary cardiac sarcomas may develop from resident or bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: Use of immunohistochemistry including CD44 and octamer binding protein 3/4. Histopathology 2012, 61, 966–973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geddert, H.; Braun, A.; Kayser, C.; Dimmler, A.; Faller, G.; Agaimy, A.; Haller, F.; Moskalev, E.A. Epigenetic Regulation of CD133 in Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors. Am. J. Clin. Pathol. 2017, 147, 515–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bozzi, F.; Conca, E.; Manenti, G.; Negri, T.; Brich, S.; Gronchi, A.; Pierotti, M.A.; Tamborini, E.; Pilotti, S. High CD133 expression levels in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Cytom. Part B Clin. Cytom. 2011, 80, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avdonkina, N.; Danilova, A.; Misyurin, V.; Prosekina, E.; Girdyuk, D.; Emelyanova, N.; Nekhaeva, T.; Gafton, G.; Baldueva, I. Biological features of tissue and bone sarcomas investigated using an in vitro model of clonal selection. Pathol.-Res. Pract. 2020, 217, 153214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skapek, S.X.; Ferrari, A.; Gupta, A.A.; Lupo, P.J.; Butler, E.; Shipley, J.; Barr, F.G.; Hawkins, D.S. Rhabdomyosarcoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Prim. 2019, 5, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saab, R.; Spunt, S.L.; Skapek, S.X. Chapter 7—Myogenesis and Rhabdomyosarcoma: The Jekyll and Hyde of Skeletal Muscle. In Current Topics in Developmental Biology; Dyer, M.A., Ed.; Cancer and Development; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 94, pp. 197–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashi, V.P.; Hatley, M.E.; Galindo, R.L. Probing for a deeper understanding of rhabdomyosarcoma: Insights from complementary model systems. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2015, 15, 426–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amer, K.M.; Thomson, J.E.; Congiusta, D.; Dobitsch, A.; Chaudhry, A.; Li, M.; Chaudhry, A.; Bozzo, A.; Siracuse, B.; Aytekin, M.N.; et al. Epidemiology, Incidence, and Survival of Rhabdomyosarcoma Subtypes: SEER and ICES Database Analysis. J. Orthop. Res. 2019, 37, 2226–2230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heymann, M.; Schiavone, K.; Heymann, D. Bone sarcomas in the immunotherapy era. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2020, 178, 1955–1972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roberts, R.D.; Lizardo, M.M.; Reed, D.R.; Hingorani, P.; Glover, J.; Allen-Rhoades, W.; Fan, T.; Khanna, C.; Sweet-Cordero, E.A.; Cash, T.; et al. Provocative questions in osteosarcoma basic and translational biology: A report from the Children’s Oncology Group. Cancer 2019, 125, 3514–3525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lytle, N.K.; Barber, A.G.; Reya, T. Stem cell fate in cancer growth, progression and therapy resistance. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2018, 18, 669–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, S.; Norgard, R.J.; Stanger, B.Z. Cellular Plasticity in Cancer. Cancer Discov. 2019, 9, 837–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muff, R.; Botter, S.M.; Husmann, K.; Tchinda, J.; Selvam, P.; Seeli-Maduz, F.; Fuchs, B. Explant culture of sarcoma patients’ tissue. Lab. Investig. 2016, 96, 752–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tellez-Gabriel, M.; Brown, H.K.; Young, R.; Heymann, M.-F.; Heymann, D. The Challenges of Detecting Circulating Tumor Cells in Sarcoma. Front. Oncol. 2016, 6, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Seebacher, N.A.; Hornicek, F.J.; Xiao, T.; Duan, Z. Application of liquid biopsy in bone and soft tissue sarcomas: Present and future. Cancer Lett. 2018, 439, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Laan, P.; van Houdt, W.J.; Broek, D.v.D.; Steeghs, N.; van der Graaf, W.T.A. Liquid Biopsies in Sarcoma Clinical Practice: Where Do We Stand? Biomedicines 2021, 9, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Asatrian, G.; Dry, S.M.; James, A.W. Circulating tumor cells in sarcomas: A brief review. Med. Oncol. Northwood Lond. Engl. 2015, 32, 430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolazzo, C.; Gradilone, A. Significance of Circulating Tumor Cells in Soft Tissue Sarcoma. Anal. Cell. Pathol. 2015, 2015, 697395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoletto, C.; Caruso, C.; Garofalo, C. Heterogeneous Circulating Tumor Cells in Sarcoma: Implication for Clinical Practice. Cancers 2021, 13, 2189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).