Highlights

What are the main findings?

- This study introduces the Hybrid Attention Fusion Network (HAFNet), a unified framework that integrates content, scale, and frequency-domain adaptivity to address the insufficient feature adaptivity in existing deep learning-based pansharpening methods.

- Comprehensive evaluations on WorldView-3, GF-2, and QuickBird datasets demonstrate that HAFNet achieves superior performance in balancing spatial detail enhancement with spectral preservation.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The study validates that a coordinated hybrid attention strategy effectively resolves the fundamental spatial-spectral trade-off in remote sensing image fusion.

- HAFNet establishes a new architectural paradigm for adaptive feature learning, offering broad applicability to other remote sensing tasks requiring multi-dimensional feature integration, such as image fusion and super-resolution.

Abstract

Deep learning–based pansharpening methods for remote sensing have advanced rapidly in recent years. However, current methods still face three limitations that directly affect reconstruction quality. Content adaptivity is often implemented as an isolated step, which prevents effective interaction across scales and feature domains. Dynamic multi-scale mechanisms also remain constrained, since their scale selection is usually guided by global statistics and ignores regional heterogeneity. Moreover, frequency and spatial cues are commonly fused in a static manner, leading to an imbalance between global structural enhancement and local texture preservation. To address these issues, we design three complementary modules. We utilize the Adaptive Convolution Unit (ACU) to generate content-aware kernels through local feature clustering, thereby achieving fine-grained adaptation to diverse ground structures. We also develop the Multi-Scale Receptive Field Selection Unit (MSRFU), a module providing flexible scale modeling by selecting informative branches at varying receptive fields. Meanwhile, we incorporate the Frequency–Spatial Attention Unit (FSAU), designed to dynamically fuse spatial representations with frequency information. This effectively strengthens detail reconstruction while minimizing spectral distortion. Specifically, we propose the Hybrid Attention Fusion Network (HAFNet), which employs the Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block (HARB) as the fundamental utility to dynamically integrate the above three specialized components. This design enables dynamic content adaptivity, multi-scale responsiveness, and cross-domain feature fusion within a unified framework. Experiments on public benchmarks confirm the effectiveness of each component and demonstrate HAFNet’s state-of-the-art performance.

1. Introduction

This paper addresses remote sensing image pansharpening, a task aiming to fuse the geometric details of a High-Resolution Panchromatic (PAN) image with a Low-Resolution Multispectral (MS) image. This process generates a High-Resolution Multispectral (HRMS) image that combines both fine spatial detail and rich spectral information [1,2]. Recent advancements in deep learning have significantly propelled the field of image restoration, including degradation perception [3], underwater image enhancement [4], and variational dehazing techniques [5]. Furthermore, removing complex artifacts like moiré patterns [6] has provided a solid feature representation foundation for multispectral image fusion. However, limited by sensor design and data transmission, MS sensors typically trade spatial resolution for spectral richness, leading to coarse spatial detail [7]. Conversely, PAN sensors capture high-frequency structural data at finer resolutions, yet they lack the spectral diversity needed for accurate material discrimination [8].

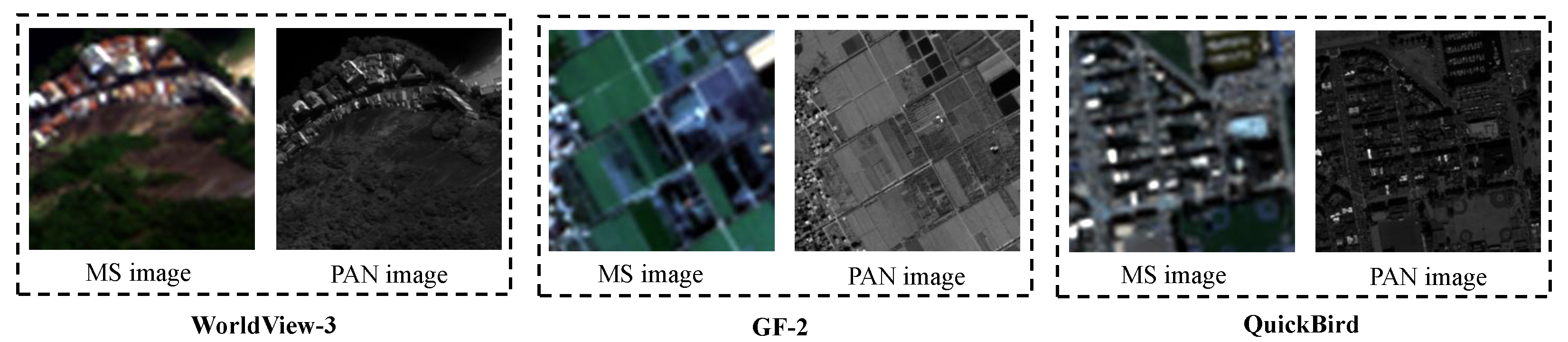

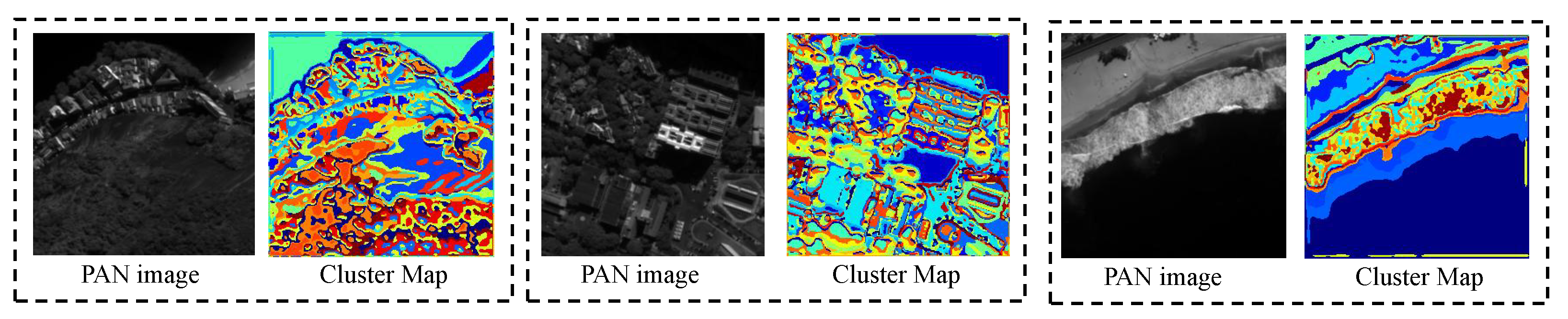

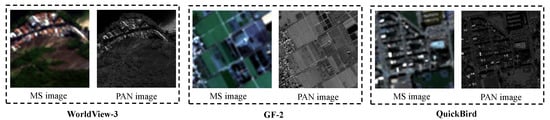

To intuitively illustrate these intrinsic differences between MS and PAN imagery, Figure 1 presents image pairs from three sensors: WorldView-3, GF2, and QuickBird. Each pair clearly shows the MS image’s spectral richness but limited spatial fidelity, while the PAN image provides fine structural detail despite its spectral sparsity. Pansharpening combines these complementary properties to generate HRMS images with sharper spatial features and consistent spectral responses. Such high-quality products support a wide range of applications, including land-cover analysis, disaster monitoring, and military reconnaissance [9,10].

Figure 1.

Example MS and PAN image pairs from WorldView-3, GF2, and QuickBird satellites. The pairs demonstrate the spectral richness of MS imagery versus the fine spatial detail of PAN imagery.

Beyond domain-specific remote sensing applications, the importance of high-quality image representations has also been widely recognized across different vision and sensing domains. In these fields, the fidelity of intermediate visual representations directly influences downstream task performance, such as object segmentation-assisted coding [11], large-scale benchmarking and evaluation [12], and multi-scale wireless perception tasks [13]. These cross-domain studies collectively indicate a broader paradigm shift from pure image reconstruction toward task-aware optimization. Motivated by this general trend, recent image fusion research has begun to explore task-driven formulations, including learnable fusion losses [14] and meta-learning-based optimization strategies [15].

Early pansharpening research primarily focused on traditional methods such as Component Substitution (CS) and Multi-Resolution Analysis (MRA). CS approaches, including IHS and PCA, are simple and efficient. However, they often assume identical spatial details across spectral bands, which can lead to substantial spectral distortion [16]. MRA methods improve spectral consistency by decomposing and recombining high-frequency and low-frequency components. However, their performance depends heavily on the chosen decomposition filter and often falls short in capturing fine spatial details [17]. With the rise of deep learning, Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) based methods such as PanNet [18] and DiCNN [19] have become mainstream. By treating pansharpening as a non-linear mapping problem, these models achieve significant improvements in fusion quality. Nevertheless, standard convolution still relies on fixed, content-agnostic kernels [20], which limits adaptability to the spectral complexity and spatial heterogeneity of remote-sensing scenes. Without the ability to assign region-specific weights, static kernels struggle with fine edges and heterogeneous surfaces, often resulting in aliasing and localized spectral distortion.

To overcome these limitations, content-adaptive mechanisms that dynamically adjust convolution parameters based on local inputs have been proposed. Early works, such as the Dynamic Filter Network (DFN) [21], generate kernel weights through auxiliary branches to achieve content awareness. Subsequent methods like PAC [22] and DDF [23] extend this idea to pixel-wise kernel generation, allowing fine adaptation across spatial regions at the cost of increased computational and memory overhead. Beyond standard convolutional approaches, biologically inspired networks have also demonstrated potential in capturing complex local dynamics. For instance, deep spiking neural networks have been successfully applied to spike camera reconstruction [24], while neuron-based spiking transmission networks [25] provide energy-efficient reasoning capabilities. These studies suggest that integrating neuron-like adaptive processing can complement conventional content-adaptive mechanisms.

However, their strictly local nature prevents the effective use of non-local contextual information. To capture global dependencies, relational modeling techniques have been introduced. Graph-based networks, including CPNet [26] and IGNN [27], establish long-range spatial connections. Recent approaches have further enhanced semantic consistency by integrating language-guided graph representation learning [28], enabling the model to understand complex structural relationships within the scene data more effectively. Additionally, Non-Local blocks and Self-Attention mechanisms leverage the Non-Local Self-Similarity property often observed in remote sensing imagery. Sampling-point optimization schemes, such as Deformable Convolution [29,30], enhance geometric flexibility by learning spatial offsets. However, they still rely on standard or imprecise dynamic kernels, which limit local adaptability.

Driven by the pursuit of higher content precision, grouped customization strategies were developed. For example, the cluster-driven adaptive convolution method CANNet [31] generates specialized kernels for clustered feature groups, greatly enhancing local perception. Despite these advancements, most existing strategies utilize these adaptive mechanisms in isolation. Current designs typically implement content adaptivity as an independent stage, which prevents effective interaction across scales and feature domains. Furthermore, dynamic multi-scale mechanisms are often constrained by global statistics, ignoring the specific regional heterogeneity of the scene. Finally, frequency and spatial cues are commonly fused through static operations, leading to an imbalance between global structural enhancement and local texture preservation. These disjointed designs limit the model’s ability to fully resolve the complex spatial-spectral trade-off.

To address these interconnected issues, we propose the Hybrid Attention Fusion Network (HAFNet). The network’s design centers on our novel Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block (HARB), which serves as the core module for unified multidimensional adaptive feature learning. Unlike previous works that treat adaptivity dimensions independently, HARB establishes a hierarchical feature refinement sequence to synergistically integrate three specialized components. First, to achieve fine-grained content adaptivity, we utilize the Adaptive Convolution Unit (ACU) to generate content-aware kernels through local feature clustering, thereby achieving fine-grained adaptation to diverse ground structures. Second, building upon the spatially adapted features from ACU, we develop the Multi-Scale Receptive Field Selection Unit (MSRFU). This unit provides flexible scale adaptability by selecting informative branches at varying receptive fields based on the local semantic content. Third, to impose a global structural constraint, we incorporate the Frequency-Spatial Attention Unit (FSAU). This unit dynamically fuses spatial representations with frequency information, effectively strengthening detail reconstruction while minimizing spectral distortion.

To sum up, our proposed HAFNet aims to address the critical, interconnected challenges that currently limit reconstruction quality. By dynamically integrating content-aware specialization, multi-scale responsiveness, and cross-domain feature balancing within a single, unified framework, HAFNet enables a more robust and comprehensive feature representation. This establishes a new paradigm for multi-dimensional adaptive feature learning in pansharpening. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

- We propose a unified Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block (HARB) that integrates content, scale, and domain adaptivity, establishing a new paradigm for synergistic multi-dimensional adaptive feature extraction.

- We design the Adaptive Convolution Unit (ACU), which employs a cluster-driven mechanism for fine-grained, content-aware feature modulation, overcoming static-kernel limitations and improving robustness against noise and geometric variations.

- We leverage the Multi-Scale Receptive Field Unit (MSRFU) to dynamically aggregate features from multiple receptive fields, resolving the rigidity of scale adaptivity by aligning receptive fields with local object structures.

- We introduce the Frequency–Spatial Attention Unit (FSAU) to dynamically balance spatial information with frequency-domain cues, reducing spectral distortion while preserving high-frequency detail.

The extensive experiments on multiple benchmark datasets demonstrate that HAFNet achieves state-of-the-art performance in both quantitative metrics and visual quality, validating the effectiveness of its synergistic attention mechanism.

2. Related Work

2.1. Content-Adaptive and Dynamic Convolution

Standard convolution is fundamentally limited by its use of fixed and spatially invariant kernels. Such static kernels cannot adjust to the diverse geometric structures or heterogeneous surface patterns found in remote sensing imagery. This primary limitation drove the development of adaptive convolution mechanisms. Early dynamic convolution methods, such as DFN [21] and DyConv [32], addressed this by generating content-conditioned kernel weights through auxiliary branches. However, since these generated filters are applied uniformly across the entire spatial field, they ultimately fail to capture fine-grained local variations in complex scenes. To overcome the uniformity constraint, pixel-wise adaptive approaches (including DC [29,30], PAC [22], and DDF [23]) were introduced. These methods maximize local flexibility by producing a unique kernel at every spatial position. However, this strategy introduces substantial computational redundancy and memory cost, making it difficult to deploy on high-resolution remote sensing data. Pansharpening-oriented variants like LAGConv [33] and ADKNet [34] further underscore the difficulty of tailoring these complex convolutions to spectral–spatial fusion tasks. Moreover, as remote sensing imagery exhibits strong Non-Local Self-Similarity (NLSS), pixel-wise approaches often overlook global redundancy, repeatedly learning similar, redundant filters.

To capture these long-range structural patterns, methods based on Non-Local operations, Self-Attention [35,36], or Graph Convolutional Networks (GCNs) [26,27] were employed. Despite their ability to establish non-local relationships, the inherent sparsity of kNN graphs and limited relational coverage restrict their capacity to fully exploit global redundancy. More recently, group-wise adaptive designs, such as the cluster-driven convolution in CANNet [31], have emerged. These methods mitigate pixel-wise redundancy by generating kernels for semantically coherent feature groups. Despite this substantial progress, most content-adaptive strategies function in a “scale-agnostic” manner. For instance, cluster-driven approaches like CANNet confine adaptation to the convolution stage without leveraging the semantic grouping to guide subsequent scale selection. In contrast, our approach utilizes these clustered features as explicit content priors to inform the adaptive receptive field mechanism, ensuring that geometric rectification directly enhances scale-specific processing.

2.2. Multi-Scale Feature Learning and Adaptive Receptive Fields

Real-world visual scenes encompass targets that vary greatly in spatial extent. This complexity is highly evident in remote sensing imagery, which includes structures ranging from fine-grained urban features to large-scale natural terrains. Accurately representing this variability requires models to perceive information across multiple receptive field (RF) scales. However, conventional convolutional networks are constrained by fixed kernel sizes and static receptive fields. Consequently, they lack the flexibility to adapt their perceptual scope to objects of different sizes, leading to incomplete feature representation and suboptimal contextual understanding.

To address this limitation, multi-scale feature learning has emerged as a key design paradigm in convolutional network architecture. Early explorations, such as Inception networks [37,38] and FractalNet [39], introduced parallel convolutional branches with heterogeneous kernel sizes to capture diverse contextual cues. Subsequent models refined this approach through grouped and pyramid convolutions. To handle dynamic content and varying object scales more effectively, researchers have explored unsupervised optical flow estimation [40] and multi-timescale motion-decoupled mechanisms [41] to better align temporal and spatial features. Despite these efforts, conventional multi-scale architectures in pansharpening remain fundamentally static.

Despite these efforts, these multi-scale architectures remain fundamentally static. The number of branches, kernel sizes, and fusion operations are predefined and fixed during training, which prevents the model from dynamically adjusting its receptive field based on input characteristics. To overcome the rigidity of such designs, dynamic receptive field mechanisms were developed. Selective Kernel Networks (SKNet) [42] pioneered an attention-based framework that adaptively selects among feature maps generated by multiple convolutional kernels based on input statistics. By allowing neurons to dynamically modulate their effective receptive field size, SKNet enables more flexible and context-dependent feature extraction. This adaptive mechanism effectively emulates a “soft” selection among scales, allowing the network to focus on the most informative context for each input region.

Following this direction, several advanced designs further extended dynamic scale adaptation. MixConv [43] achieved multi-scale integration by mixing different kernel sizes within a single depthwise convolution. CondConv [44] and Dynamic Kernel Aggregation [32] introduced condition-dependent routing or kernel weighting strategies to enhance scale sensitivity. These methods collectively demonstrate the growing consensus that adaptive receptive fields are critical for robust and generalizable representation. Despite these advances, most dynamic multi-scale mechanisms determine attention weights based on global pooling statistics, which tends to homogenize diverse land covers. Consequently, they often assign uniform receptive fields across the image, failing to distinguish between fine-grained urban textures and broad natural terrains. Our method differs by performing scale selection at a refined feature level, where local semantic clusters drive the aggregation of multi-branch responses, thereby aligning the receptive field with specific regional structures.

2.3. Frequency-Spatial Feature Fusion and Cross-Domain Processing

Spatial-domain convolution has long been the backbone of deep pansharpening networks. However, its inherently local receptive field limits the ability to capture large-scale structural relationships and to robustly separate genuine high-frequency details from noise. Remote sensing imagery contains a complex mixture of broad homogeneous regions, repetitive man-made patterns, and subtle textural variations. This complexity has motivated researchers to explore frequency-domain representations, which offer complementary benefits by providing a global receptive field and explicit spectral decomposition of image structures. Early frequency-based pansharpening efforts mainly aimed to extract or enhance high-frequency components. Yang et al. [18] and Zhou et al. [45] applied handcrafted or learned high-pass filters to strengthen structural details during fusion. With the evolution of research, FFT-based modeling became more prominent. Zhang et al. [46] incorporated Fourier phase modeling to better preserve structural consistency. Zhou et al. [47,48] introduced invertible neural networks (INNs) to jointly process images in both spatial and frequency domains, demonstrating the advantage of multi-domain representations for improving spectral fidelity. Beyond pansharpening, frequency-domain cues have proven useful for denoising, enhancement, and reconstruction [49,50,51], highlighting the importance of global frequency structures in remote sensing tasks.

Other studies focused on explicit frequency separation. Diao et al. [52] manually divided low- and high-frequency bands and supervised them with separate objectives. Xing et al. [53] used wavelet-based multi-resolution analysis for hierarchical fusion. Zhou et al. [54] combined Fourier masking with learned filtering, though they did not incorporate explicit cross-domain supervision. More recent methods introduced learnable masks or gating mechanisms [55], which often rely on handcrafted priors or complex training strategies.

Together, these studies show that frequency-domain modeling has progressed significantly, with methods like high-frequency residual feature guidance for MRI [56] and self-adaptive Fourier augmentation [57]. Furthermore, the frontier of pansharpening is expanding with framelet-based conditional diffusion models [58], wavelet-assisted multi-frequency attention networks [59], bidomain uncertainty gated recursive networks for enhanced domain generalization [60], and two-stage fine-tuning strategies like PanAdapter [61] which injects spatial-spectral priors. However, a key challenge remains in the rigid coupling of domains. Existing methods typically enforce a fixed fusion ratio or rely on separate loss constraints, which prevents the network from adjusting to local variations. This often leads to the over-injection of high-frequency noise or the suppression of genuine details. Distinct from these static approaches, our framework introduces a learnable gating mechanism within the residual block. This design dynamically re-weights spatial and frequency contributions on a sample-by-sample basis, ensuring a robust balance between global structural preservation and local detail enhancement.

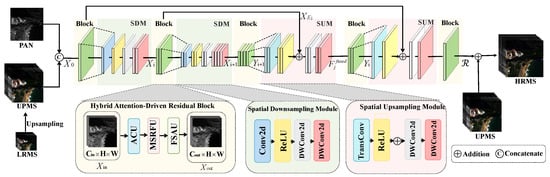

3. Methods

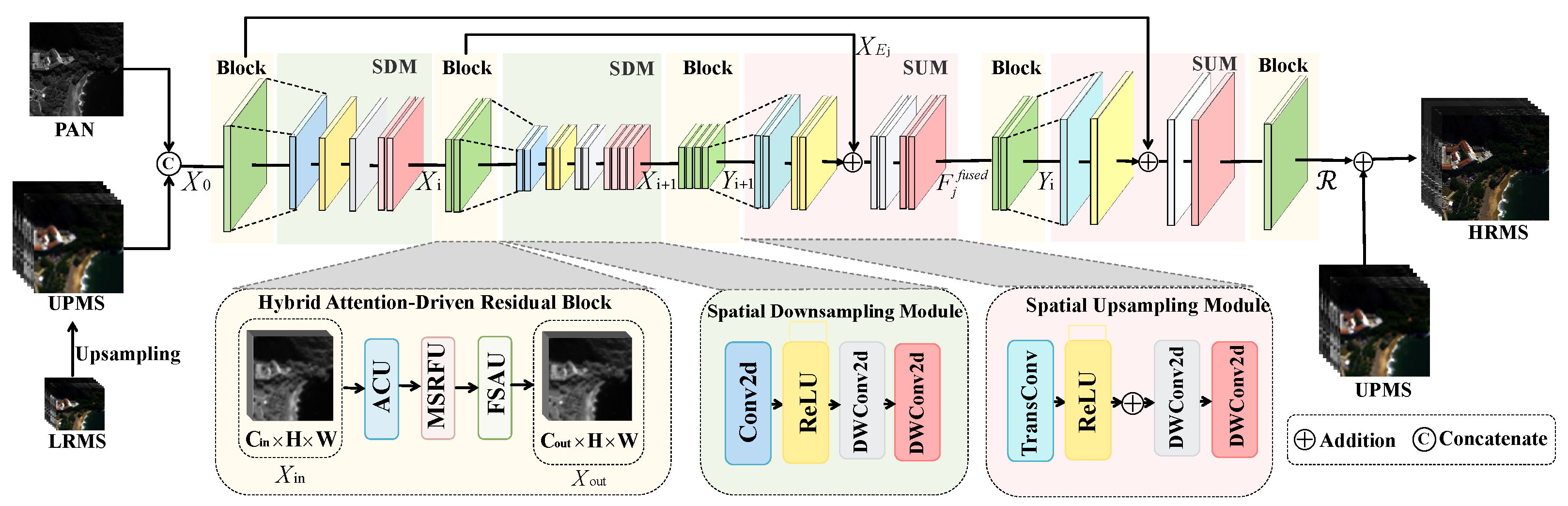

The overall architecture of our proposed Hybrid Attention Fusion Network (HAFNet) is illustrated in Figure 2. The network adopts an encoder–decoder paradigm, where the core feature extraction is accomplished through our newly designed Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block (HARB). This module is carefully designed to integrate three complementary mechanisms: content-adaptive attention, scale-adaptive attention, and cross-domain attention. Unlike traditional models that employ these mechanisms in isolation, HAFNet unifies them to explicitly address the interconnected challenges of limited adaptivity, rigid scale modeling, and insufficient spatial-spectral interaction. During training, our objective is to learn a mapping function . This function fuses a high-resolution panchromatic () image with a low-resolution multispectral () image to produce the target high-resolution multispectral () output.

Figure 2.

Overall architecture of the Hybrid Attention Fusion Network (HAFNet). The network adopts a U-shaped encoder–decoder design with skip connections for hierarchical feature extraction. Feature learning is centered around the Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block (HARB), which integrates the ACU, MSRFU, and FSAU modules (illustrated in the inset). The final HRMS image is generated via residual addition.

3.1. Problem Formulation

Let denote the panchromatic image, and denote the low-resolution multispectral image, where r is the spatial resolution ratio and C is the number of spectral bands. To align spatial resolutions, is first upsampled using a conventional interpolation method to produce . This upsampling step ensures spatial consistency for subsequent joint feature extraction [62]. Our network is formulated as a robust residual learning framework. This approach transforms the pansharpening problem from a difficult “image-to-image” mapping into a more tractable “detail injection” problem. The network focuses on learning the missing high-frequency spatial details and the spectral compensation components (), effectively preserving the low-frequency spectral content already present in . This design significantly aids optimization and maintains spectral fidelity.

The input tensors are concatenated to form the initial feature representation :

where is the initial input feature representation, is the panchromatic image, and is the upsampled low-resolution multispectral image.The network then learns a complex residual representation . The final HRMS image is obtained by adding this learned residual to the upsampled multispectral image:

where is the reconstructed high-resolution multispectral image, and is the residual map learned by the network .

3.2. Overall Network Architecture

The overall HAFNet architecture is shown in Figure 2. We adopt a U-shaped encoder–decoder design with skip connections, which is highly effective for capturing multi-scale contextual features and maintaining precise spatial localization. The network begins by passing the input feature through a shallow convolutional layer () for initial feature embedding, resulting in .

The features flow through N encoder stages. Each stage i contains a single HARB module for deep feature transformation, followed by a Spatial Downsampling Module (), which reduces the spatial resolution by a factor of . The uses learnable stride-2 convolutions instead of conventional pooling to avoid irreversible information loss. The feature propagation in the encoder is defined as:

where is the input feature map to stage i, is the core processing block, and reduces the spatial resolution. After the final encoder stage, the features pass through a bottleneck layer consisting of a single HARB module to capture rich global context.

The decoder symmetrically reverses the encoding operations using the Spatial Upsampling Module () to gradually restore spatial resolution. Each decoding stage j fuses the upsampled features with the corresponding encoder features through element-wise addition (skip connection):

where is the output of the previous decoder stage, is the feature from the corresponding encoder stage, and is the feature map fused via the skip connection. This addition directly injects high-frequency details from the encoder. The fused features are then refined by a HARB module to produce the decoder stage output . The final residual map is obtained by projecting the last decoder output back to C channels via a convolution (), which is then added to .

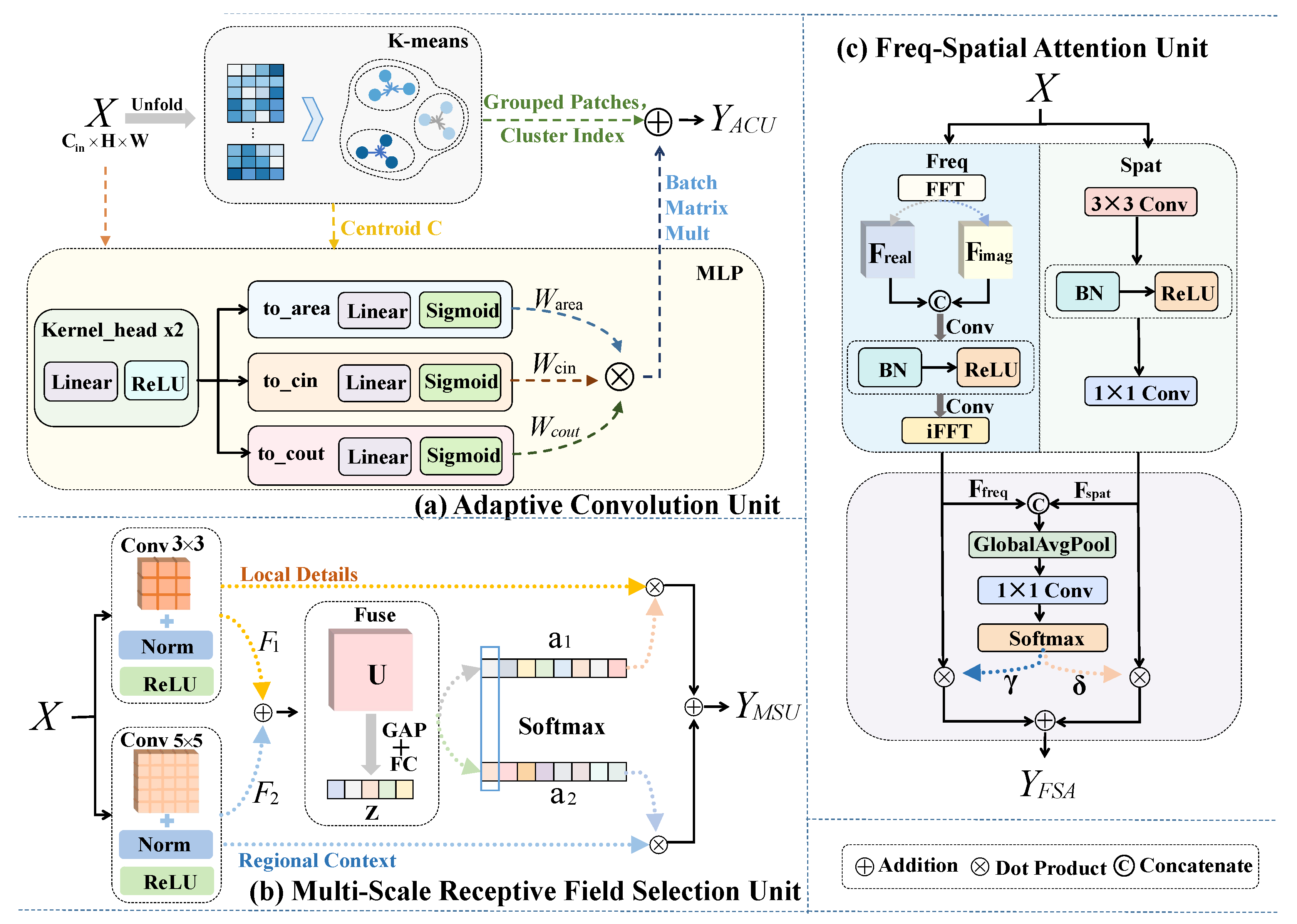

3.3. Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block

The HARB serves as the central computational component of HAFNet. Its design directly addresses a key limitation in previous studies where content, scale, and domain adaptivity were treated as separate, non-interacting modules. HARB integrates these adaptive aspects into a unified architecture, enabling synergistic learning across content, scale, and frequency domains. Its design is conceptually motivated by structured probabilistic modeling approaches, such as those employed in advanced variational inference frameworks for video summarization [63]. HARB integrated design is not merely a stacking of attention blocks but a structured pipeline that coordinates feature modulation across multiple dimensions. As illustrated in Figure 3, HARB adopts a residual learning formulation. This approach stabilizes training and ensures reliable gradient propagation in deep architectures. The block computes the output feature by adding the input to a non-linear transformation of the input:

where and are the input and output feature tensors, and represents the non-linear residual function. The identity path allows the residual branch to focus solely on enhancing discriminative details. The core transformation is realized as a sequential pipeline of three specialized units: Adaptive Convolution Unit (), Multi-Scale Receptive Field Selection Unit (), and Frequency–Spatial Attention Unit (). The sequential computation is defined as:

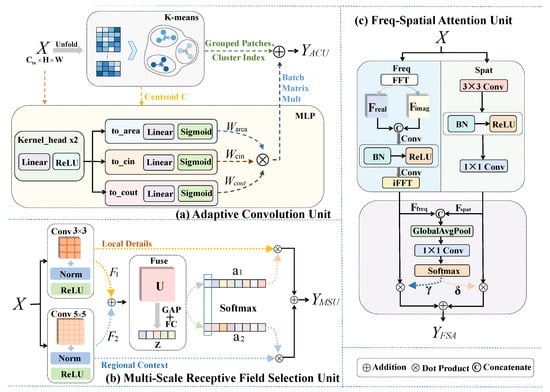

Figure 3.

Structure of the Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block (HARB). The core transformation refines features through three synergistic units: ACU for content-aware specialization, MSRFU for scale adaptation, and FSAU for balancing spatial and frequency features. These units collectively enable multi-dimensional feature adaptivity.

This sequential arrangement establishes a hierarchical feature refinement pipeline. Specifically, the first performs geometric rectification to generate content-aware features (), providing a spatially accurate foundation. These rectified features then enable the to align the receptive field with the actual semantic structures of the objects. Finally, the applies a global frequency-domain constraint to the multi-scale features, ensuring that the locally enhanced details are spectrally calibrated before being injected into the residual stream. This ordered dependency allows HARB to achieve a comprehensive representation that is robust to both geometric variations and spectral inconsistencies.

3.4. Adaptive Convolution Unit

The Adaptive Convolution Unit (), illustrated in Figure 3, is designed to address content adaptivity. departs from less flexible standard dynamic convolutions and pixel-wise dynamic filters by leveraging a cluster-driven adaptive mechanism. This novel approach strikes a necessary balance between achieving high feature adaptivity and maintaining computational efficiency. The operation of is realized in three distinct, sequential parts: patch unfolding and grouping, cluster-specific kernel generation, and efficient partition-wise convolution.

3.4.1. Patch Unfolding and Grouping

To enable content awareness, the input feature map is first transformed into a collection of overlapping patches via an operation. This results in , where is the total number of patches and k is the kernel size. To maintain computational feasibility for clustering, the high-dimensional patch features are first downsampled to a lower-dimensional representation . These features are then partitioned into K semantic clusters using the algorithm:

where is the cluster assignment map, K is the number of semantic clusters, and N is the total number of patches. The elements of the map store the assigned cluster index (ranging from 0 to ) for each corresponding patch.

The clustering is performed via an iterative optimization framework where patch assignments are determined by minimizing the squared Euclidean distance to the nearest cluster centroid. By recursively updating these centroids to represent the mean feature vector of their respective groups, the algorithm ensures that patches with consistent semantic textures and radiometric properties are aggregated into coherent partitions. This convergence-driven grouping serves as the prerequisite for generating specialized kernels tailored to distinct ground structures in the subsequent stage.

3.4.2. Cluster-Specific Kernel Generation

For each cluster , we first compute its centroid . The centroid is derived by averaging the original patches that are assigned to that specific cluster index . This calculation accurately represents the mean feature characteristic of the k-th semantic cluster:

where is the centroid of cluster k, is the Iverson bracket which equals 1 if the condition is true and 0 otherwise, and is the n-th input patch. Subsequently, a shared Multi-Layer Perceptron (MLP), denoted as , generates a cluster-specific convolution kernel and bias based on the computed centroid :

where and are the generated cluster-specific kernel and bias, respectively. This generation process enables content-aware transformation tailored to the underlying characteristics of each cluster.

3.4.3. Efficient Partition-Wise Convolution

The final adaptive convolution step applies cluster-specific kernels () to their corresponding patches. Dynamically retrieving a unique kernel for every patch introduces severe, irregular memory access and reduces throughput. To maintain high efficiency, we implement a specialized data strategy. This method addresses irregular memory access by leveraging the cluster assignment map . We reorganize and group all patches that share the identical kernel . This crucial grouping converts many small, scattered operations into a few large, continuous matrix multiplications. Consequently, the model executes a single, highly efficient batched matrix operation for all patches within each cluster. The resulting partition-wise convolution output patch is computed as:

where is the n-th output patch, is the n-th input patch, and and are the cluster-specific kernel and bias, respectively, retrieved based on the cluster assignment . This architectural optimization ensures the efficient execution of the partition-wise convolution. This allows to deliver high adaptivity without incurring the typical irregular memory penalties, making it highly suitable for large-scale remote sensing imagery.

3.5. Multi-Scale Receptive Field Selection Unit

The Multi-Scale Receptive Field Selection Unit () enhances the content-adaptive behavior of the . Unlike traditional multi-scale blocks that operate on static features, MSRFU introduces a learnable scale adaptivity that is explicitly conditioned on the semantically refined output of the ACU. While adapts to content variations, its fixed receptive field limits its ability to model structures of heterogeneous spatial extents. resolves this limitation by using a multi-branch transformation and an adaptive soft selection mechanism.

3.5.1. Multi-Branch Feature Aggregation

The receives the -refined feature map as input. It applies M parallel transformation operators, . Each operator is associated with a distinct effective receptive field to generate multi-scale features :

where is the feature response of the m-th branch, is the -refined input feature, and is the m-th parallel transformation operator (). Each operator consists of a depthwise convolution, followed by activation and normalization. This design enables multi-scale representation with minimal computational overhead. In our specific implementation (), we use receptive fields of and . This two-branch configuration allows to jointly capture fine textures and broader contextual structures. Specifically, the branch focuses on modeling local high-frequency details, while the branch captures slightly broader spatial context, forming a pair of complementary receptive fields sufficient for effective multi-scale feature aggregation in pansharpening.

3.5.2. Global Context Encoding

First, the multi-scale feature responses are aggregated via element-wise summation: . This step combines information from all scales. The fused map is then summarized using Global Average Pooling (). This operation derives a compact channel descriptor by averaging across the spatial dimensions H and W:

where is the global channel descriptor, H and W are the height and width of the feature map, is the aggregated feature map, and denotes the channel values at spatial location .This vector encapsulates the global distribution of multi-scale responses, providing content-aware conditioning for the subsequent adaptive scale selection.

3.5.3. Adaptive Weight Generation

A lightweight transformation network, , processes the global descriptor . It maps to branch-specific attention logits :

where is the attention logit for branch m (), and is the lightweight transformation network.These logits are then normalized along the scale dimension using the Softmax function. This yields probability-like attention weights :

where is the normalized attention weight for branch m, and .

3.5.4. Adaptive Multi-Scale Fusion

The final output of is a weighted combination of all branch responses . This is an adaptive multi-scale fusion process:

where is the final output feature of the module, is the computed branch weight, and ⊙ denotes channel-wise modulation. Specifically, this channel-wise attention mechanism is designed to synergize with the spatial adaptivity of the preceding ACU. Since the input features have already undergone fine-grained spatial rectification via the ACU, the MSRFU focuses on recalibrating the importance of different receptive fields along the channel dimension. This allows the network to learn a distributed representation where specific channels specialize in capturing local high-frequency details while others encode broader contextual cues. Consequently, the model effectively preserves representational diversity across heterogeneous regions, ensuring that multi-scale information is integrated without being homogenized by global statistics.

3.6. Frequency–Spatial Attention Unit

The Frequency–Spatial Attention Unit (FSAU), illustrated in Figure 3, addresses the single-domain limitation of conventional CNNs. It achieves this by jointly modeling complementary spatial-domain and frequency-domain representations. The ’s operation consists of three stages: dual-domain feature extraction, adaptive cross-domain fusion, and weighted feature combination.

3.6.1. Dual-Domain Feature Extraction

Given the input feature map , the module extracts two parallel responses. The spatial branch uses a standard convolutional operator to produce the spatial features . Simultaneously, the frequency branch first applies the 2D Real Fast Fourier Transform () to obtain a complex-valued tensor . Unlike localized transforms such as the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) or Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT), FFT provides a global receptive field that captures holistic frequency interactions across the entire scene. This global perspective is critical for maintaining radiometric consistency and preserving spectral fidelity in the pansharpened image. This complex tensor is decomposed into its real (ℜ) and imaginary (ℑ) components. We purposefully select this real-imaginary representation over the magnitude-phase decomposition. As highlighted in surveys on complex-valued learning [64], the polar representation often suffers from the phase wrapping problem, where the periodicity of the phase component introduces discontinuities that hinder the stability of gradient-based optimization. In contrast, the real-imaginary representation ensures algebraic continuity, allowing the network to learn stable linear transformations.

A learnable frequency-domain filter then processes these concatenated components:

where is the processed frequency-domain tensor, is the learnable filter, and and denote the real and imaginary parts, respectively. An inverse transform then returns this frequency-enhanced representation to the spatial domain:

where is the final frequency-branch feature in the spatial domain. This process yields spatial-domain features that are enriched with global structural cues.

3.6.2. Adaptive Cross-Domain Fusion

The dual-domain features and are first concatenated to form . This combined tensor is then fed into a lightweight fusion network . This network incorporates Global Average Pooling to generate domain-selection weights and :

where and are the computed scalar weights for each domain, and is the lightweight fusion network. These weights provide a probabilistic interpretation of the relative importance assigned to spatial versus frequency representations, with .

3.6.3. Weighted Combination

The final output of the is a weighted combination of the two domain responses, which are adaptively merged using the computed weights:

where is the final output feature of the module, ⊙ denotes channel-wise modulation, and and are the adaptive weights. This formulation effectively implements a learnable gating mechanism, allowing the network to dynamically favor spatial or spectral cues on a sample-by-sample basis. This ensures a robust balance between local detail injection and global structural preservation. Similar to Spiking Tucker Fusion Transformers used in audio-visual learning [65] and multi-layer probabilistic association reasoning networks [66], our module dynamically reweights spatial and frequency contributions on a sample-by-sample basis, overcoming the limitations of static fusion strategies.

3.7. Loss Function

HAFNet is optimized using the loss (Mean Absolute Error) as the primary training objective. This choice is motivated by the characteristics of reduced-resolution pansharpening, where local intensity inconsistencies frequently arise from sensor noise, spatial misalignment, and downsampling artifacts. Compared with the loss, the loss applies a linear penalty to pixel-wise errors. This property makes the optimization process less sensitive to localized large deviations and more favorable for preserving inter-band radiometric relationships [67,68,69]. Although additional spectral or perceptual constraints can be incorporated, our framework strategically emphasizes architectural mechanisms, specifically hybrid attention modules and content-adaptive convolutions, to inherently enforce spectral and spatial consistency. This design avoids the hyperparameter sensitivity associated with balancing multi-term loss functions. The effectiveness of this choice is empirically validated in Section 4.5.4 through an ablation study comparing and losses on the WV3 reduced-resolution dataset.

Given the predicted high-resolution multispectral image and the ground truth , the loss is defined as:

where B, C, H, and W represent the batch size, number of spectral bands, height, and width, respectively. This function minimizes the average pixel-wise absolute error across all bands and samples. During training, the network parameters are optimized by minimizing using the Adam optimizer. We employ a step decay learning rate schedule to ensure stable convergence across the deep architecture. This strategy reduces the learning rate by a predefined factor at specific training epochs. This facilitates the network’s escape from shallow local minima and enables precise fine-tuning of parameters during later stages.

4. Experiment

In this section, we systematically evaluate the proposed Hybrid Attention Fusion Network (HAFNet) for remote sensing pansharpening. The experiments cover dataset configurations, implementation details, quantitative and qualitative analyses, an ablation study, and a discussion. They aim to comprehensively validate HAFNet’s capability to balance spectral fidelity and spatial detail preservation.

4.1. Datasets and Evaluation Metrics

We comprehensively evaluate HAFNet on three remote sensing benchmarks from the PanCollection repository [70]: WorldView-3 (WV3), Gaofen-2 (GF2), and QuickBird (QB). These datasets, from different satellite sensors, vary in spatial resolution, spectral configuration, and land-cover type. This diversity enables a rigorous assessment of HAFNet’s ability to preserve both spectral fidelity and spatial details under heterogeneous conditions.

The WorldView-3 (WV3) dataset provides panchromatic (PAN) images at 0.3 m resolution and multispectral (MS) images at 1.2 m resolution, containing eight spectral bands: coastal, blue, green, yellow, red, red edge, NIR1, and NIR2. Its high spectral complexity makes WV3 particularly suitable for evaluating the model’s ability to reconstruct intricate spectral information while maintaining fine spatial structures. The dataset includes dense urban regions, agricultural zones, and coastal scenes, offering representative yet challenging scenarios for high-resolution pansharpening. The Gaofen-2 (GF2) dataset includes PAN images at 0.8 m resolution and MS images at 3.2 m resolution with four bands: red, green, blue, and NIR. Its varied landscapes, from mountains to industrial areas, are effective for evaluating regional-scale fusion and the model’s response to terrain and texture changes. The QuickBird (QB) dataset contains PAN images at 0.61 m resolution and MS images at 2.44 m resolution across four bands: blue, green, red, and NIR. As a classical multispectral benchmark widely used in remote sensing, QB includes suburban residential areas, farmland, and wetlands. These scenes allow for evaluating the robustness of HAFNet in preserving spectral-spatial correlations under typical imaging conditions.

For all datasets, MS images are upsampled to PAN resolution using bicubic interpolation (). Both PAN and images are normalized to the range [0, 1] to reduce radiometric discrepancies and stabilize network training. Following standard pansharpening protocol, 90% of the reduced-resolution samples are used for training, 10% for validation, and an additional 20 reduced-resolution and 20 full-resolution samples are reserved for testing. The specific partitioning for each dataset is summarized in Table 1, ensuring balanced distribution across imaging conditions and geographical coverage. The dataset partition strategy provides sufficient diversity for model generalization while maintaining consistency across training and evaluation phases.

Table 1.

Number of training, validation, and test samples for each dataset.

When evaluating algorithms for the pansharpening task, it is essential to consider both the spatial detail injection and the preservation of spectral fidelity. Therefore, we employ two sets of commonly used metrics to comprehensively evaluate the results on both Reduced-Resolution Datasets (with ground truth) and Full-Resolution Datasets (no ground truth).

For the reduced-resolution datasets, we use four standard with-reference metrics: Spectral Angle Mapper (SAM), Erreur Relative Globale Adimensionnelle de Synthèse (ERGAS), Spatial Correlation Coefficient (SCC), and the Generalized Quality Index (, represented as or ). SAM quantifies spectral distortion by calculating the angle between spectral vectors, thus measuring spectral fidelity. ERGAS evaluates the overall reconstruction quality by balancing spatial and spectral distortions. SCC focuses on the preservation of spatial information and measures the correlation of spatial details between the fused image and the PAN image. simultaneously evaluates both the spectral and spatial consistency of the fused image.

As for the full-resolution datasets, where ground truth is unavailable, we apply three standard no-reference metrics: Spectral Distortion Index (), Spatial Distortion Index (), and the Quality with No Reference Index (). focuses on spectral distortion, measuring the consistency between the fused image and the original multispectral image. evaluates spatial distortion, assessing how well the fused image preserves the spatial details of the original panchromatic image. integrates both and into a single metric, providing a comprehensive and balanced assessment of the fusion quality spectrally and spatially.

4.2. Implementation Details

The model was trained for 500 epochs using the Adam optimizer. The primary optimization objective chosen was the loss (Mean Absolute Error, ), which offers superior robustness to outliers and is essential for preserving spectral fidelity in remote sensing applications. The training process began with an initial learning rate of , which was managed using a step-wise decay strategy. This schedule involved reducing the learning rate by a factor of at predefined epochs (epoch 250). This approach was implemented to facilitate stable convergence across the deep architecture, enabling precise parameter fine-tuning during later training stages.

All experiments were conducted on NVIDIA GPUs using a consistent batch size of 32. For the network structure, the base feature dimension was uniformly set to 32 channels across all datasets, ensuring a consistent feature dimensionality for the clustering process regardless of the initial number of spectral bands. Specific to the Adaptive Convolution Unit (), we configured 32 clusters to capture distinct semantic variations. Furthermore, a confidence threshold of was applied. This threshold was chosen based on the consideration that clusters with extremely low occupancy rates (below ) generally correspond to noisy or rarely activated patterns, which contribute little to feature aggregation while increasing computational cost. Discarding these clusters provides a practical means to reduce noise and maintain computational efficiency, while retaining the dominant semantic structures captured by the ACU. Finally, the input configuration was tailored to the specific datasets: the network processed 8-band input for the WorldView-3 dataset, and 4-band input for the GF2 and QuickBird datasets, matching the available multispectral channels.

4.3. Quantitative Results and Analysis

To comprehensively evaluate the performance of the proposed HAFNet, we conducted quantitative comparisons against diverse state-of-the-art methods on three benchmark datasets. These included traditional methods (BT-H [71], MTF-GLP-FS [72], BDSD-PC [73]) and established CNN-based approaches (FusionNet [74], TDNet [75], BiMPan [76]). To represent advances in adaptive fusion and frequency-aware modeling, we selected LAGConv [33], LGPConv [77], CML [78], PEMAE [79], and HFIN [80]. Moreover, we included recent Transformer and Mamba-based architectures to benchmark against the latest paradigms, specifically HyperTransformer [81], PreMix [82], GGP-Net [83], and PanMamba [84]. The evaluation was performed in two stages: reduced-resolution (RR) assessment using reference-based metrics and full-resolution (FR) assessment using no-reference metrics.

As shown in Table 2, HAFNet consistently demonstrates superior performance on the reduced-resolution datasets. On the WV3 dataset, HAFNet achieves the lowest ERGAS (2.1827) while attaining the highest Q8 (0.9212) and SCC (0.9856), surpassing all compared methods. Although PanMamba yields a marginally lower SAM (2.9132 vs. 2.9422), HAFNet outperforms it in all other reported metrics, showing a stronger capability in overall structural preservation. On the GF2 dataset, HAFNet achieves the best SAM (0.7223) and ERGAS (0.6347), while maintaining highly competitive Q4 (0.9843) and SCC (0.9917) scores. This indicates a superior balance between spectral and spatial consistency, avoiding the common pitfall of over-emphasizing spatial sharpness at the expense of spectral fidelity. For the QB dataset, while GGP-Net exhibits lower spectral distortion in SAM and ERGAS, HAFNet achieves the best performance in SCC (0.9815) and maintains a high Q4 (0.9331), which is significantly better than most CNN-based approaches. These results validate the model’s superior perceptual quality and its ability to accurately inject spatial details without introducing artifacts.

Table 2.

Quantitative comparison of different methods on three benchmark datasets. The best and second-best results are highlighted in bold and underline, respectively.

For the full-resolution evaluation on WV3, GF2, and QB datasets, HAFNet demonstrates robust performance and high fidelity (Table 3). Specifically, HAFNet achieves the state-of-the-art results across all three metrics (, , and QNR) on the WV3 dataset, while maintaining competitive spectral and spatial distortion indices on both GF2 and QB samples. The consistently low values across these sensors confirm that HAFNet excels in preserving the physical spectral characteristics of the original multispectral image, effectively avoiding color distortion. Meanwhile, the balanced scores indicate that the model accurately injects high-frequency details from the PAN image. These results obtained from different satellite sensors validate the model’s capability to generate high-quality fused images with superior spectral-spatial consistency in real-world scenarios where no ground truth is available.

Table 3.

Average full-resolution evaluation results on WV3, GF2, and QB datasets. The best and second-best results are highlighted in bold and underline, respectively.

In summary, reduced-resolution and full-resolution experiments validate HAFNet’s robust capabilities in pansharpening. The model achieves state-of-the-art performance, particularly on comprehensive metrics (Q8/Q4, QNR) and spectral fidelity indicators (e.g., ERGAS, ). Notably, HAFNet attains the highest QNR on the WV3 dataset and maintains top-tier performance across GF2 and QB samples. Compared to other recent advanced methods like PanMamba and PreMix, HAFNet confirms its effectiveness in balancing the inherent trade-off between spectral preservation and spatial enhancement. The Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block (HARB) effectively integrates multi-scale and multi-band features. This enables the generation of fused images with excellent perceptual quality and high spectral-spatial consistency. Furthermore, the model maintains stable generalization across different satellite sensors and imaging conditions.

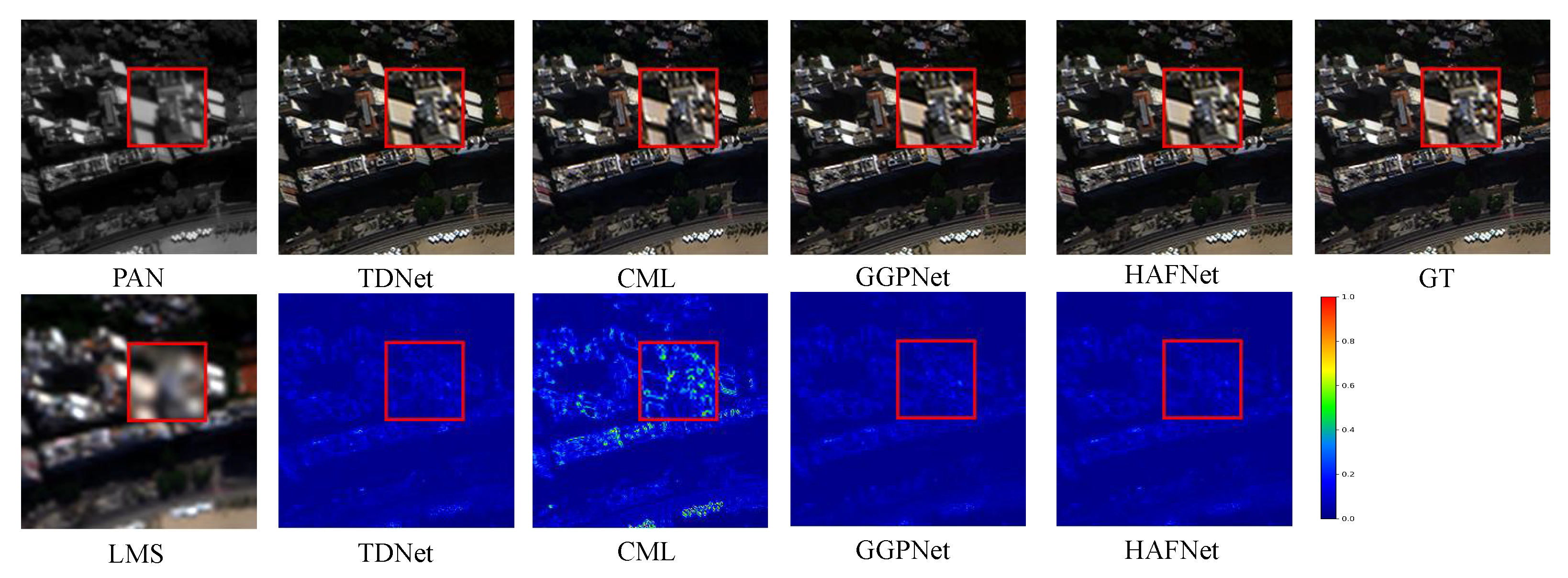

4.4. Visualization and Qualitative Analysis

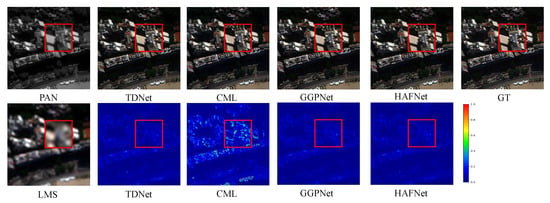

To further assess the perceptual quality of the fused results, Figure 4 presents a detailed visual comparison on a representative WV3 test scene. This scene contains dense urban structures, high-frequency roof textures, and complex illumination variations, making it an effective benchmark for evaluating both spatial detail reconstruction and spectral integrity. The figure includes the input PAN and LMS images, the outputs of TDNet, CML, GGPNet, and the proposed HAFNet, as well as the GT reference for reduced-resolution evaluation.

Figure 4.

Visual comparison on a challenging WV3 test scene. Top row: PAN input, fused results of TDNet, CML, GGPNet, HAFNet, and the GT reference. Bottom row: LMS input and absolute difference maps relative to the GT. The red boxes highlight an urban region containing high-frequency structural details, where notable differences in spatial fidelity and spectral consistency can be observed across methods.

As shown in Figure 4, TDNet and CML show significant limitations in reconstructing high-frequency roof structures. Their results present blurred edges in the white-gray rooftop segments, with some linear features either oversmoothed or incorrectly sharpened. In comparison, GGP-Net produces sharper contours than TDNet and CML. Nevertheless, its building edges still appear softened, and the roof ridges lack the sharp geometric profiles visible in the ground truth (GT). In contrast, HAFNet demonstrates substantially improved spatial fidelity. Its hybrid attention fusion mechanism accurately extracts and injects structural details from the PAN image, resulting in sharp roof boundaries, smooth shadow transitions, and clear façade textures. In the red-boxed region, the fine roof geometry closely matches the ground truth, and subtle intensity transitions are reproduced without over-sharpening or artifacts.

Although TDNet and CML reconstruct some structural elements, their fused images contain noticeable spectral distortions, especially in the roof and vegetation areas. GGPNet alleviates part of this issue, yet slight color deviations remain visible around highly reflective rooftop surfaces. In contrast, HAFNet achieves the most accurate spectral reconstruction. It successfully preserves the color distribution of the original multispectral image while integrating spatial details in a controlled manner. The bottom row of Figure 4 presents the absolute difference maps with respect to the GT. TDNet and CML show extensive bright and mid-intensity regions across the buildings. GGPNet produces overall darker maps, but still contains noticeable high-error responses around the roof edges. The HAFNet residual map is the darkest and most uniform among all methods, indicating more stable reconstruction across both homogeneous and heterogeneous regions.

4.5. Ablation Study

To systematically validate the necessity of each component and justify the architectural design choices of the Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block (HARB), we conducted a comprehensive ablation study on the WV3 dataset. The analysis is structured into three parts: an evaluation of component contributions and their interactions (Section 4.5.1), a validation of the adaptive convolution mechanism (Section 4.5.2), and an analysis of the frequency domain representation (Section 4.5.3).

4.5.1. Component Contributions and Synergistic Effects

To address concerns regarding the individual effectiveness of each module, we expanded the ablation experiments to include a “Plain Baseline” (a standard residual block with static convolutions) and evaluated each proposed unit independently. The quantitative results are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Quantitative analysis of component contributions on the WV3 dataset. Bold indicates the best performance, and underline indicates the second best.

We first examine the individual contributions of each module relative to the Baseline (Model I). Replacing the static convolution with the proposed ACU (Model II) yields the most significant single-module improvement. It increases the QNR from 0.9280 to 0.9371. This result indicates that content-adaptive convolution plays a dominant role in enhancing feature discrimination under heterogeneous scene conditions. Similarly, the standalone introduction of MSRFU (Model III) improves the QNR to 0.9364. This highlights the effectiveness of multi-scale receptive fields in accommodating objects with varying spatial extents.

We further analyze the interaction between modules, with a particular focus on the Frequency-Spatial Attention Unit (FSAU). As shown in Model IV, applying FSAU in isolation leads to a noticeable performance degradation compared to the baseline. This empirical observation suggests that global spectral–spatial operations can be sensitive to the stability of input features, which motivates positioning FSAU after the local and regional adaptation stages. To further investigate this behavior, we compare Model VI with Model II to isolate the impact of introducing FSAU in the absence of MSRFU. The results indicate that adding FSAU increases spatial distortion, with rising from 0.0464 to 0.0478. This implies that effective global frequency enhancement benefits from sufficient spatial context. Without the multi-scale structural support provided by MSRFU, the frequency module may amplify misaligned high-frequency components rather than refining meaningful details.

Importantly, this behavior is alleviated in the complete framework (Model VII), where the joint integration of ACU and MSRFU provides enhanced spatial regularization. By enforcing content-consistent and multi-scale structural constraints, the network reduces to its lowest value of 0.0312. Under this stabilized feature representation, FSAU is able to more effectively exploit its spectral modeling capability, achieving the lowest spectral distortion () while preserving fine spatial details. These results demonstrate a strong synergistic interaction among the proposed modules, highlighting the role of hierarchical feature stabilization in frequency-aware attention mechanisms.

4.5.2. Validation of the Adaptive Convolution Mechanism

We further investigate the effectiveness of the proposed cluster-driven ACU. In this experiment, the MSRFU and FSAU modules are retained. We only replace the ACU with other representative dynamic convolution methods. Table 5 reports the quantitative comparison.

Table 5.

Comparison of adaptive convolution strategies on the WV3 dataset. The upper rows compare different dynamic methods, while the lower rows analyze the effect of cluster number K. Bold indicates the best performance, and underline indicates the second best.

As shown in the upper section of Table 5, the proposed ACU achieves the highest QNR (0.9544). It outperforms CondConv [44], DCN [30], and MetaConv [85]. CondConv and DCN introduce adaptive behaviors through fine-grained or spatially local modulation. However, such mechanisms can be overly sensitive to high-frequency noise. In contrast, ACU performs region-level kernel adaptation. It clusters features based on semantic similarity. This enforces content consistency across spatially correlated areas.

The lower section of Table 5 analyzes the influence of the cluster number K. Setting provides the best trade-off between adaptivity and stability. degenerates to static convolution (QNR = 0.9472). This indicates insufficient adaptivity. Conversely, slightly degrades performance (QNR = 0.9447). This is due to redundant kernel generation.

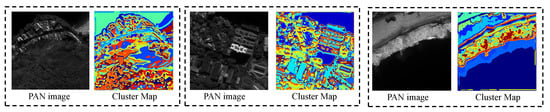

Beyond quantitative results, we provide qualitative evidence of the ACU’s adaptability in Figure 5. The visualization reveals a strong correlation between the learned cluster assignments and actual semantic regions. For instance, the module effectively distinguishes breaking waves from calm water and separates building rooftops from shadowed streets. This structural alignment demonstrates that the ACU successfully captures local feature characteristics, enabling the application of specialized kernels for fine-grained adaptation.

Figure 5.

Visualization of the spatial cluster assignments learned by the ACU. The Cluster Maps demonstrate that the learned clusters align closely with semantic boundaries, verifying the module’s fine-grained content adaptation.

4.5.3. Analysis of Frequency Domain Representation

We validate the choice of the frequency transform in the FSAU module. In this analysis, the ACU and MSRFU modules are present. We only substitute the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) with the Discrete Cosine Transform (DCT) or Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT).

As reported in Table 6, FFT achieves the lowest spectral distortion and maintains the highest QNR. Theoretically, pansharpening requires maintaining global radiometric consistency across the entire image. By operating on the full image signal, FFT captures holistic frequency interactions and long-range dependencies. These are critical for preserving spectral fidelity. In contrast, the localized nature of DWT and DCT limits their ability to model such global spectral relationships. This leads to inferior performance in this task.

Table 6.

Evaluation of frequency domain representations on the WV3 dataset. Bold indicates the best performance, and underline indicates the second best.

4.5.4. Analysis of Optimization Objective

To evaluate the impact of the training objective, we conduct an ablation study comparing the and losses on the WV3 reduced-resolution dataset. All experimental settings remain unchanged except for the loss function. As reported in Table 7, models trained with the loss achieve consistently better spectral-related metrics, including SAM and ERGAS, while maintaining competitive spatial quality. In contrast, the loss tends to emphasize minimizing large local errors, which leads to smoother predictions and slightly degraded spectral consistency in complex regions. These results indicate that the loss provides a more balanced optimization objective for pansharpening, aligning well with the goal of preserving spectral fidelity while reconstructing fine spatial details.

Table 7.

Ablation study of different loss functions on the WV3 reduced-resolution dataset. The best results are highlighted in bold.

4.6. Computational Efficiency Analysis

To assess the practical deployability of the proposed HAFNet, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of computational complexity (in FLOPs) and model size (in Parameters). Table 8 presents the comparison of HAFNet against the representative CNN-based FusionNet [74], the lightweight LGPConv [77], and the state-of-the-art Mamba-based architecture, PanMamba [84].

Table 8.

Comparisons on FLOPs and parameter numbers. The best results are highlighted in bold.

As reported in Table 8, while LGPConv [77] achieves the best performance in terms of model compression with only 0.027 M parameters and 0.112 G FLOPs, HAFNet maintains a remarkably competitive computational cost of 0.327 G FLOPs. This efficiency is comparable to the standard FusionNet [74] (0.323 G) and is significantly superior to the Mamba-based PanMamba [84], which requires approximately 2.07 G FLOPs.

Although HAFNet exhibits a larger parameter count (1.171 M) compared to the lightweight LGPConv [77], this represents a deliberate architectural trade-off to support the high-capacity feature mapping required for our Adaptive Convolution Unit (ACU). Unlike the static kernels used in lightweight models, the ACU generates content-aware kernels through local feature clustering to adapt to diverse ground structures. Thanks to the optimized partition-wise operation strategy, these parameters do not all participate in simultaneous calculation for every pixel. This design ensures that HAFNet achieves state-of-the-art fusion quality while maintaining an inference efficiency that remains well-suited for large-scale remote sensing applications.

5. Discussion

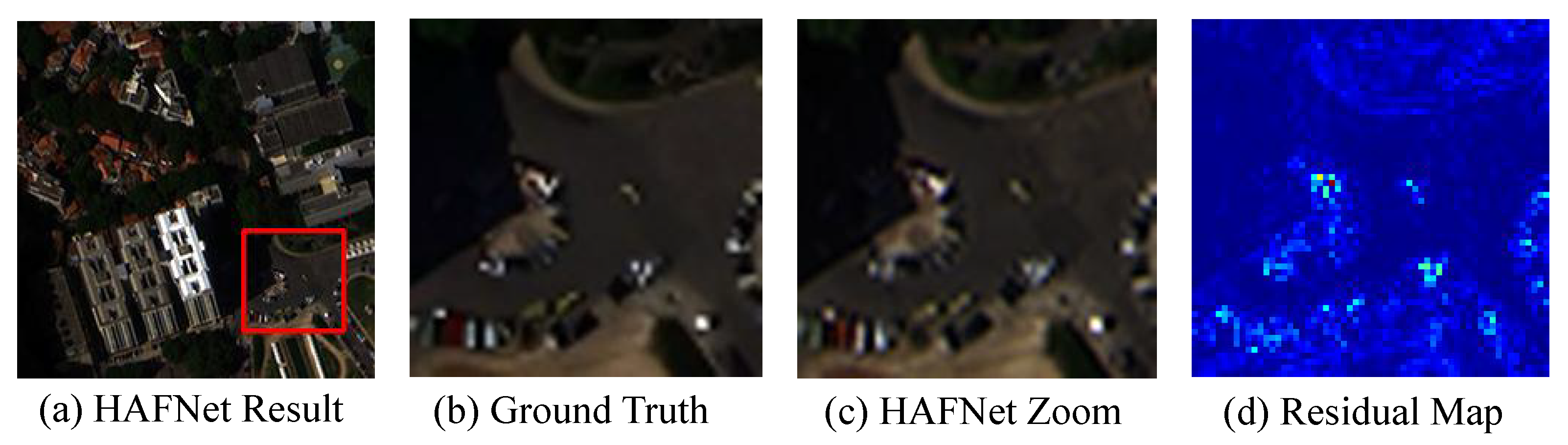

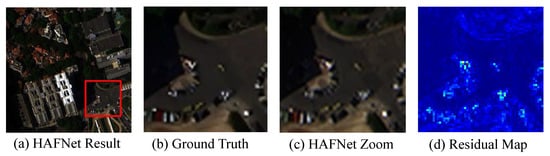

HAFNet demonstrates state-of-the-art performance in both quantitative metrics and visual reconstruction quality. However, we must acknowledge specific limitations in challenging scenarios. Figure 6 illustrates a typical failure case selected from the WorldView-3 (WV3) dataset. This sample depicts a complex urban scene. We present the full HAFNet result in Figure 6a and compare its zoomed detail (c) against the ground truth (b). As shown in the residual map (d), noticeable bright spots appear around the edges of the vehicles. These errors indicate that HAFNet struggles to maintain perfect spectral fidelity in high-frequency transition regions. This phenomenon is primarily attributed to the intense spectral heterogeneity at object interfaces, where sharp PAN-induced spatial details are injected into MS pixels with rapidly shifting radiometric properties. In such cases, the cluster-driven mechanism of the ACU module may group these edge pixels into a dominant semantic cluster, slightly perturbing local spectral fidelity. While the current adaptive design improves overall robustness, capturing extremely fine-grained, pixel-level spectral transitions in highly heterogeneous areas remains challenging.

Figure 6.

Qualitative analysis of a typical failure case. (a) The pansharpened result by HAFNet. (b) The ground truth of the zoomed region. (c) The zoomed version of the HAFNet result. (d) The residual map between the result and the ground truth. Brighter pixels in the residual map indicate larger spectral distortions.

Besides local spectral errors, the computational cost is another concern. The Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block uses complex adaptive mechanisms. These designs improve accuracy but require more calculation than static CNN models. This complexity restricts real-time deployment on hardware with limited resources. Future work will explore model compression, knowledge distillation, or efficient approximations to reduce complexity while preserving adaptivity.

Another limitation lies in the upsampling strategy. HAFNet currently uses fixed bicubic interpolation for the low-frequency reference. This non-learnable method may introduce aliasing artifacts. We plan to develop a learnable upsampling module in future versions. This will allow the model to optimize spatial alignment and frequency recovery jointly in an end-to-end manner.

Finally, extending HAFNet to hyperspectral data remains a challenging frontier due to the inherent high redundancy and complex cross-band correlations. Current frequency-spatial fusion alone may not fully resolve these issues. Future work will therefore explore spectral grouping and band-wise attention strategies. In this pursuit, we will draw inspiration from advanced geometric modeling paradigms such as Riemann-based multi-scale reasoning [86] and hyperbolic-constraint reconstruction [87] to robustly handle high-dimensional and correlated feature spaces. Moreover, although HAFNet demonstrates consistent performance across WorldView-3, GF-2, and QuickBird sensors, these experiments mainly focus on same-sensor reconstruction. Explicit cross-dataset domain generalization remains a rigorous challenge and constitutes another important direction for future research.

6. Conclusions

In conclusion, this paper introduces the Hybrid Attention Fusion Network (HAFNet) for high-fidelity multispectral pansharpening. HAFNet integrates three core components in the Hybrid Attention-Driven Residual Block (HARB) to achieve simultaneous improvement in spectral fidelity and spatial detail. The ACU provides content-aware feature extraction through cluster-driven dynamic kernels, the MSRFU adaptively selects multi-scale receptive fields to capture structural details, and the FSAU enforces frequency-spatial constraints to maintain spectral consistency. Extensive experiments on multiple benchmark datasets demonstrate that HAFNet surpasses state-of-the-art methods in both quantitative metrics and visual quality. Ablation studies further confirm the individual contributions of each module and highlight the synergistic effect when all units operate jointly. These results demonstrate that HAFNet provides a unified and robust framework for adaptive pansharpening, offering effective high-resolution reconstruction and a solid foundation for future multi-dimensional feature fusion research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.X., J.Z. and W.L.; Methodology, D.X. and J.Z.; Software, J.Z.; Investigation, D.X., J.Z. and W.L.; Data curation, X.W.; Validation, X.W., P.W. and X.F.; Formal analysis, D.X.; Writing—original draft, J.Z.; Writing—review and editing, W.L.; Supervision, W.L.; Project administration, D.X. and W.L.; Funding acquisition, W.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1008501), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC) under grant 624B2049 and 62402138, the Pre-research Project of CIPUC under grant Y2024035, the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2025M784373) and the Jiangsu Funding Program for Excellent Postdoctoral Talent.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets used in this study are publicly available. The WorldView-3, GaoFen-2, and other benchmark pansharpening datasets were obtained from the PanCollection repository, which can be accessed at https://github.com/liangjiandeng/PanCollection (accessed on 24 December 2025). No new datasets were generated in this study. Additional experimental configurations and processing scripts are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the technical support and constructive feedback received during the preparation of this manuscript. The authors would also like to express their gratitude to the academic editor and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable time and insightful comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Amro, I.; Mateos, J.; Vega, M.; Molina, R.; Katsaggelos, A.K. A survey of classical methods and new trends in pansharpening of multispectral images. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2011, 2011, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, F.; Wan, W.; Yu, H.; Sun, J.; Del Ser, J.; Elyan, E.; Hussain, A. Panchromatic and multispectral image fusion for remote sensing and earth observation: Concepts, taxonomy, literature review, evaluation methodologies and challenges ahead. Inf. Fusion 2023, 93, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ma, J.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, L. Perceive-ir: Learning to perceive degradation better for all-in-one image restoration. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Zhang, L.; Du, B. UniUIR: Considering Underwater Image Restoration as an All-in-One Learner. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 6963–6977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, F.; Wang, T.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, T.; Zhang, G. Variational single image dehazing for enhanced visualization. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2019, 22, 2537–2550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, F.; Wang, T.; Wu, S.; Zhang, G. Removing moiré patterns from single images. Inf. Sci. 2020, 514, 56–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivone, G.; Alparone, L.; Chanussot, J.; Dalla Mura, M.; Garzelli, A.; Licciardi, G.; Restaino, R.; Wald, L. A critical comparison of pansharpening algorithms. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium, Quebec City, QC, Canada, 13–18 July 2014; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2014; pp. 191–194. [Google Scholar]

- Ciotola, M.; Guarino, G.; Vivone, G.; Poggi, G.; Chanussot, J.; Plaza, A.; Scarpa, G. Hyperspectral pansharpening: Critical review, tools, and future perspectives. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Mag. 2025, 13, 311–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, C.; Ranchin, T.; Wald, L.; Chanussot, J. Synthesis of multispectral images to high spatial resolution: A critical review of fusion methods based on remote sensing physics. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2008, 46, 1301–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Miao, J.; Li, G.; Tan, Y.; Yu, S.; Liu, X.; Zeng, L.; Li, G. Pan-Sharpening Network of Multi-Spectral Remote Sensing Images Using Two-Stream Attention Feature Extractor and Multi-Detail Injection (TAMINet). Remote Sens. 2023, 16, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Yuan, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, D.; Tang, X.; Wu, F. Object segmentation-assisted inter prediction for versatile video coding. IEEE Trans. Broadcast. 2024, 70, 1236–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Liao, J.; Tang, C.; Zhang, H.; Li, Y.; Bian, Y.; Sheng, X.; Feng, X.; Li, Y.; Gao, C.; et al. Ustc-td: A test dataset and benchmark for image and video coding in 2020s. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2026, 28, 269–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Li, J.; Ma, M.; Hong, X.; Fan, X. Multi-scale spiking pyramid wireless communication framework for food recognition. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2025, 27, 2734–2746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Cui, Y.; Feng, T.; Xu, S. Task-driven Image Fusion with Learnable Fusion Loss. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Nashville, TN, USA, 11–15 June 2025; pp. 7457–7468. [Google Scholar]

- Bai, H.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, J.; Wu, Y.; Deng, L.; Cui, Y.; Jiang, B.; Xu, S. Refusion: Learning image fusion from reconstruction with learnable loss via meta-learning. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2025, 133, 2547–2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, T.M.; Su, S.C.; Shyu, H.C.; Huang, P.S. A new look at IHS-like image fusion methods. Inf. Fusion 2001, 2, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nason, G.P.; Silverman, B.W. The stationary wavelet transform and some statistical applications. In Wavelets and Statistics; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995; pp. 281–299. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Fu, X.; Hu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Ding, X.; Paisley, J. PanNet: A deep network architecture for pan-sharpening. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 5449–5457. [Google Scholar]

- He, L.; Rao, Y.; Li, J.; Chanussot, J.; Plaza, A.; Zhu, J.; Li, B. Pansharpening via detail injection based convolutional neural networks. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2019, 12, 1188–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Y.; Yang, Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, H.; Qi, Q. Full convolutional neural network based on multi-scale feature fusion for the class imbalance remote sensing image classification. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 3547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; De Brabandere, B.; Tuytelaars, T.; Gool, L.V. Dynamic filter networks. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2016, 29, 667–675. [Google Scholar]

- Su, H.; Jampani, V.; Sun, D.; Gallo, O.; Learned-Miller, E.; Kautz, J. Pixel-adaptive convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 11166–11175. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Jampani, V.; Pi, Z.; Liu, Q.; Yang, M.H. Decoupled dynamic filter networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 19–25 June 2021; pp. 6647–6656. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, R.; Xiong, R.; Zhang, J.; Yu, Z.; Zhu, S.; Ma, L.; Huang, T. Spike camera image reconstruction using deep spiking neural networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 34, 5207–5212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Ma, Z.; Deng, L.J.; Fan, X.; Tian, Y. Neuron-based spiking transmission and reasoning network for robust image-text retrieval. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2022, 33, 3516–3528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Fu, X.; Zha, Z.J. Cross-patch graph convolutional network for image denoising. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 4651–4660. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, S.; Zhang, J.; Zuo, W.; Loy, C.C. Cross-scale internal graph neural network for image super-resolution. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2020, 33, 3499–3509. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Han, W.; Man, H.; Zuo, W.; Fan, X.; Tian, Y. Language-Guided Graph Representation Learning for Video Summarization. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, J.; Qi, H.; Xiong, Y.; Li, Y.; Zhang, G.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y. Deformable convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 764–773. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, X.; Hu, H.; Lin, S.; Dai, J. Deformable convnets v2: More deformable, better results. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 16–20 June 2019; pp. 9308–9316. [Google Scholar]

- Duan, Y.; Wu, X.; Deng, H.; Deng, L.J. Content-adaptive non-local convolution for remote sensing pansharpening. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 17–21 June 2024; pp. 27738–27747. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Dai, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, D.; Yuan, L.; Liu, Z. Dynamic convolution: Attention over convolution kernels. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Virtual, 14–19 June 2020; pp. 11030–11039. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Z.R.; Zhang, T.J.; Jiang, T.X.; Vivone, G.; Deng, L.J. LAGConv: Local-context adaptive convolution kernels with global harmonic bias for pansharpening. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Virtual, 22 February–1 March 2022; pp. 1113–1121. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, S.; Deng, L.J.; Hu, J.F.; Zhuo, Y.W. Source-Adaptive Discriminative Kernels based Network for Remote Sensing Pansharpening. In Proceedings of the IJCAI, Vienna, Austria, 23–29 July 2022; pp. 1283–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Mairal, J.; Bach, F.; Ponce, J.; Sapiro, G.; Zisserman, A. Non-local sparse models for image restoration. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE 12th International Conference on Computer Vision, Kyoto, Japan, 29 September–2 October 2009; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2009; pp. 2272–2279. [Google Scholar]