Highlights

What are the main findings?

- Using geologic mapping, spectral data, and crater counting techniques, we identify two distinct plains units northwest of the Caloris impact basin on Mercury.

- The results are more consistent with a volcanic origin, but a contribution from impact processes cannot be ruled out.

What is the implication of the main finding?

- The findings are consistent with prior work indicating widespread resurfacing of mercurian plains units.

- The upcoming BepiColombo mission may be able to help address outstanding questions about the origin of these plains units.

Abstract

Mercury hosts widespread smooth plains that are concentrated in the Caloris impact basin, in an annulus surrounding the Caloris basin, and in the adjacent northern smooth plains. The origins of these smooth plains are uncertain, although prior work suggests these plains in the northwestern Caloris annulus might reflect volcanic activity, impact ejecta, or a combination of the two. Deciphering the timing and mode of emplacement of these plains would provide a critical constraint on regional late-stage volcanism or impact effects. In this work, the region northwest of Caloris was investigated using geomorphological and color-based mapping, crater counting techniques, and spectral analyses with the goal of placing constraints on the source of the observed units and identifying the primary emplacement mechanism. Mapping and spectral analyses confirm previous findings of two distinct, yet intermingled, units within these plains, each with similar crater count model ages that postdate the formation of the Caloris impact basin. Mapping, spectra analysis, ages, and the identification of potential flow pathways are more consistent with a predominantly volcanic origin for the smooth plains materials, although these data do not rule out contributions from impact ejecta or impact melt. We propose several hypothetical scenarios, including post-emplacement modification by near-surface volatiles, to explain these observations and clarify the emplacement mechanism for these specific smooth plains regions. Further observations from the BepiColombo mission should provide data to potentially address the outstanding questions from this work.

1. Introduction

The Mariner 10 mission and the subsequent MErcury Surface, Space ENvironment, GEochemistry, and Ranging (MESSENGER) mission provided evidence for a complex surface evolution for the planet Mercury. The surface of Mercury is composed of three primary geomorphological terrain types: smooth plains, intercrater plains, and intermediate terrains. There are also three distinct spectral units consisting of high-reflectance red plains (HRPs), intermediate-reflectance plains (IRPs), and low-reflectance blue plains (LBPs), along with a low-reflectance material (LRM), which are characterized by a combination of differing spectral slopes, relative reflectance values, and surface morphologies (e.g., [1,2]). The intermediate geomorphological terrain contains a unit referred to as the intercrater plains, which are widespread and comprise approximately one-third of the exposed intermediate terrain. These materials have been interpreted as representing an effusive volcanic unit, perhaps not unlike the smooth plains unit, but which has experienced significant degradation and heavy cratering [3]. By contrast, the vast exposures of smooth plains, the Caloris interior plains, circum-Caloris exterior plains, and northern smooth plains have been variously interpreted to have formed from impact ejecta, volcanism, or a mix between the two [4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16]. Smooth plains deposits share morphological characteristics that include sparse cratering, level terrain, distinct boundaries with adjacent terrains, embayment of older units, and lowland ponding (e.g., [1,12,17]). After the recognition that post-emplacement deformation of the plains had occurred, specifically related to the development of long-wavelength topographic undulations [18,19], the morphological description of these units was modified to include the presence of gently rolling topography [12]. Here we investigate the origin of plains units in and near Caloris using a combination of geologic mapping, crater size–frequency distribution analyses, and spectral analyses.

2. Background

Geological Background and Characteristics of Mercurian Smooth Plains

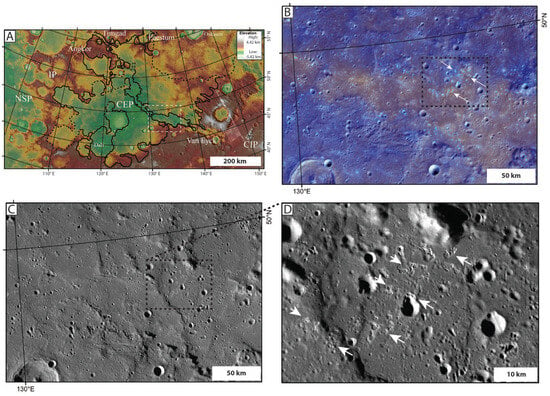

The Caloris exterior plains form a nearly continuous annulus around the Caloris basin, the interior of which has also been filled by smooth plains material (Figure 1A,B) (e.g., [9,10]), and are intermingled in the northeast and east with the Caloris Montes, Nervo, Odin, and Van Eyck formations, which are collectively interpreted as Caloris rim and ejecta units (e.g., [20]). The origin of the Caloris exterior plains has been attributed to emplacement of impact-related melt, direct deposition of impact ejecta, and surficial emplacement of volcanic melt. Such interpretations are based primarily on apparent stratigraphic relationships between the smooth plains and adjacent terrain, and geospatial proximity to Caloris [4,20,21,22,23]. A volcanic origin for the majority of the smooth plains appears favored by most researchers, as evidenced by characteristics such as their smooth morphology, widespread distribution (including non-proximity to impacts basins), relative youth compared to the largest impact basins, color characteristics, and embayment of the Caloris rim and other topographically highstanding terrain [5,7,8,9,10,11,13,15,17,24,25,26]. Potential lava flow paths (Figure 1C) have been identified leading from the northern smooth plains into the Caloris exterior plains [13], and from the Caloris interior plains into the Caloris exterior plains through the Caloris rim, utilizing the linear troughs of the Van Eyck formation [9]. The potential flow pathways into the Caloris exterior plains through the bounding valleys that lead from the northern smooth plains also contain potential flow structures, such as kipukas, that range in size up to ~20 km long [13]. The possibility for limited pyroclastic activity has also been associated with coalesced depressions found within several smooth plains regions, though these features may represent a more effusive style of eruption [13], which is supportive of a volcanic origin for the surrounding region. Other features have been identified that suggest the potential for flow within, into, and out from the Caloris interior [27]. Still, other investigators have pointed out that despite the fact that volcanism is widespread, the origin of some smooth plains is more ambiguous and might result from mixing of impact and volcanic lithologies (e.g., [12,28,29]). There are examples of ejecta related to the Caloris impact that are mixed with later smooth plains deposits (e.g., [9,12,26]), supporting the interpretation that impact events played some part in the sequence of events that formed these plains deposits.

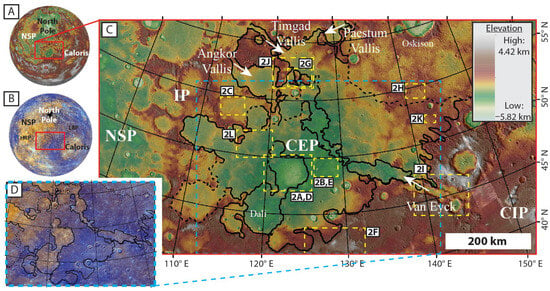

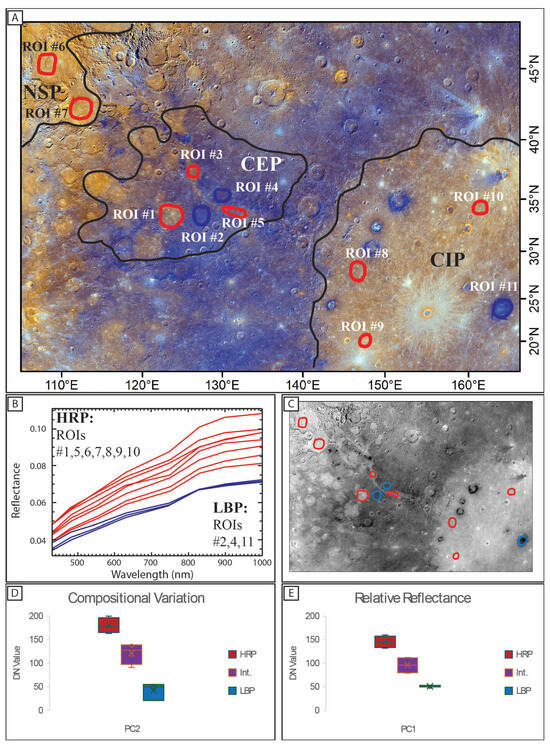

Figure 1.

(A) Global topography centered on the Caloris exterior plains (CEP; 125°E, 60°N), with adjacent northern smooth plains (NSPs) to the northwest and the Caloris basin to the southeast. (B) Global enhanced color image (R: PC2, G: PC1, B: 430 nm/1000 nm) centered on the Caloris exterior plains, highlighting color differences between the low-reflectance blue plains (LBPs) annulus containing the Caloris exterior plains and the high-reflectance red plains (HRPs) units in the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains. (C) Topographic overview of the study area with general unit outlines, solid black lines denoting certain contacts and dashed black lines denoting approximate contacts. The intercrater plains (ICPs) lie in between the northern smooth plains and Caloris exterior plains. Potential flow pathways from the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains (CIPs) into the Caloris exterior plains are identified (white arrows). (D) Subset of the enhanced color mosaic covering the study area (shown by dashed blue box in (C)) in the Caloris exterior plains, highlighting the presence of both LBPs in the south and east and HRPs in the north and west in the region. Dashed yellow boxes denote the type locations given in Figure 2 and described in Table 1. All images utilize an orthographic projection. Image mosaics credit: NASA/Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory/Carnegie Institution of Washington.

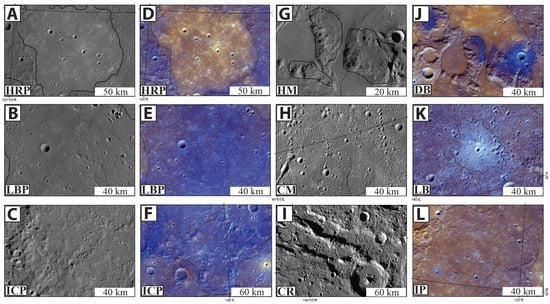

Figure 2.

Geomorphological and color-based (R: PC2, G: PC1, B: 430 nm/1000 nm) units, from the MDIS WAC basemap and MDIS 3 band enhanced color mosaic, respectively, used to map the Caloris exterior plains (see Table 1), with locations denoted in Figure 1. To highlight the differences in color between the units, they are displayed using the enhanced color RGB combination. Each color image is subject to a uniform color combination using the above RGB bands in order to facilitate direct visual comparisons between the regions. Pairs (A,D) and (B,E) demonstrate the morphology and color characteristics of the HRPs and LBPs, respectively. Covering two different areas, (C,F) highlight the smaller-scale surface morphologies (C) and generally blue color of the ICP (F). Panels (G,J), located in the same region, demonstrate the isolated nature of the mesas and their varied color characteristics. Panel (H) shows a spread of secondary crater chains possibly related to Oskison crater, due to their approximate N-S orientation relative to that crater. Panel (K) shows an example of the very bright, light blue material found scattered throughout the Caloris exterior plains in limited exposures, generally related to small and likely recent impact events. Panel (I) highlights a segment of the crater rim material associated with the Caloris basin. Panel (L), an example of the intermediate plains, which exhibits a mix of red and blue material, with some small exposures of light blue interspersed throughout.

Table 1.

Units and their morphological- and/or color-based descriptions, derived from the MDIS monochrome basemap, MLA DEM topography, and MDIS 3-band color basemap (R: 1000 nm, G: 750 nm, B: 430 nm). These morphological and color characteristics define the units in the Caloris exterior plains (Figure 2) and were used to map their contacts throughout the region, resulting in a comprehensive map.

Table 1.

Units and their morphological- and/or color-based descriptions, derived from the MDIS monochrome basemap, MLA DEM topography, and MDIS 3-band color basemap (R: 1000 nm, G: 750 nm, B: 430 nm). These morphological and color characteristics define the units in the Caloris exterior plains (Figure 2) and were used to map their contacts throughout the region, resulting in a comprehensive map.

| Unit | Morphology/Texture | Color Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| High-Reflectance Red Plains (HRPs) | Relatively smooth, few wrinkle ridges, extensional features present. | Red hue in color and enhanced color imagery. |

| Low-Reflectance Blue Plains (LBPs) | Relatively rough, knobs and wrinkle ridges present. | Blue hue in color and enhanced color imagery. |

| Intermediate Plains (IPs) | Relatively smooth, few wrinkle ridges. Generally located between expanses of HRP and LBP units. | Intermediate plains materials that exhibit a mixture of red and blue hues. |

| Intercrater Plains (ICPs) | Relatively highstanding terrain that bounds the CEP. Knobs, wrinkle ridges, and craters are prevalent. | Generally blue with slight mixture of red. |

| Highstand Material (HM) | Isolated highstanding mesas, primarily located in valleys and bounded by HRP and LBP material. | Primarily red hued, but mixed with some dark and light blue exposures. |

| Crater Material (CM) | Significant ejecta blanket and secondary crater fields associated with Oskison crater. Craters with distinct ejecta blankets or rims. | Generally red hue surrounding portions of the crater. |

| Caloris Rim (CR) | Continuous sections of the rim material bounding the Caloris basin, including the Van Eyck formation. | Generally mixed red and blue hues. |

| Light Blue (LB) | Small, highly reflective ejecta blankets associated with small impact craters. | Extremely light blue hue in enhanced color images. |

| Dark Blue (DB) | Small, isolated expanses of low-reflectance material, limited areal coverage, typically found along mesa edges. | Dark blue material generally surrounded by HRP material in enhanced color images. |

Compositional variations in these smooth plains have been inferred from various spectral datasets covering a wide range of the electromagnetic spectrum, including 400–1000 nm (e.g., [1,2,30]), gamma rays [31], and X-rays [32]. These three spectrally distinct smooth plains units include the HRPs, IRPs, and LBPs (Figure 1B,C) [1,2]. The HRPs have been interpreted as low-Fe, basalt-like mafic compositions, whereas the LBPs, though similarly low in Fe, have been identified as having higher Mg/Si and Ca/Si ratios, and lower Al/Si ratios, which are more consistent with ultramafic compositions [33,34,35]. The northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains have been spectrally classified as HRP, and the Caloris exterior plains have been classified as LBP (Figure 1B,D) e.g.,[1,2,12]. Within the study area of the present work over in the northwestern portion of the Caloris exterior plains, comingled deposits of HRP and LBP are present (Figure 1D) [9], and have an elemental composition intermediate between the plains units identified in the Caloris exterior plains and northern smooth plains [31,32,36,37].

Despite the spectral similarities between the HRP deposits in the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains, elemental abundances show marked differences in composition among all three smooth plains regions (e.g., [31,32,33,34]). X-Ray Spectrometer (XRS) [38] and Gamma-Ray Spectrometer (GRS) [39] data measured during the MESSENGER mission were used to differentiate the surface of Mercury into different geochemical terranes that represent distinct compositions [31,32,40]. Compositional differences exist among the smooth plains units and present themselves as distinct color variations between the Caloris interior plains and northern smooth plains. Although both the interior plains and northern smooth plains exhibit low-Mg abundances, and the exterior plains exhibit a low- to intermediate-Mg abundance, a clear spatial trend exists for Al abundance, wherein the Caloris interior plains have high-Al abundances that decrease toward the northern smooth plains, which have low- to intermediate Al abundances [31,32,40,41]. This Al-abundance trend has been interpreted as resulting from differing amounts of Na in source magmas of Mercury that affected the type of plagioclase produced and the final Al concentrations [32]. The Caloris exterior plains are apparently intermediate in composition between the Caloris interior plains and northern smooth plains regions, and may be gradational between them. Alternatively, it has been suggested that fractional crystallization instead of mantle heterogeneity could account for the observed compositional and spectral variation between smooth plains units within and outside Caloris [42].

Together, these geochemical signatures have been used to suggest that the smooth plains in the Caloris exterior plains, Caloris interior plains, and northern smooth plains are related, each derived from Caloris impact-induced deep mantle melting and convection that tapped different portions of the mantle, leading to subsequent eruptions of varying compositions [5,31,32,43]. This timing of melt development which could have sourced surficial lava flows has been inferred to have occurred within 1–2 Ma from the initial impact event, although remnant thermal anomalies in the mantle related to the impact might have been capable of generating limited melt after >100 Ma [43]. Compositionally different portions of the mantle have been modeled to arise from sluggish mantle convection leading to lateral and vertical heterogeneities, which are consistent with the observed compositional heterogeneities between the Caloris interior plains and northern smooth plains deposits [31,32,44,45,46]. Coupling these apparent geochemical signatures to newly mapped units in the Caloris exterior plains can provide a clearer understanding of the relationship between composition and surface materials.

The various smooth plains also have crater size–frequency distributions (CSFDs) that suggest emplacement relatively early in Mercury’s geologic evolution. Previous crater-count-derived model ages suggest that the intercrater plains were emplaced during the late heavy bombardment (LHB) [3] whereas the northern smooth plains, Caloris interior plains, and Caloris exterior plains were emplaced after the Caloris basin formed at ~3.9 Ga, either during the waning phases of the LHB or following its cessation (e.g., [7,8,9,12,47]). These smooth plains deposits were emplaced in a relatively narrow ~200 Ma window of time, between ~3.7 and 3.9 Ga [7,8,9,12,14,15]. However, the application of different production functions on Mercury (i.e., model predictions of the impact flux) provides a broader envelope within which this restricted age range resides, i.e., pushing the range younger to 3.3 ± 0.3 Ga or even 2.5 ± 0.3 Ga [15]. The relative comparison of the crater abundance above a certain diameter N (x) can also be employed to determine the relative order in which the units formed (e.g., [14,15]). Regardless of this uncertainty, the crater retention ages for the smooth plains units suggest they were emplaced prior to global contraction and the termination of large-scale volcanism on Mercury [14].

The derived ages for the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains are statistically indistinguishable [8,12,15], whereas the derived ages suggest the Caloris exterior plains are slightly younger [7,8,9,12], with the exception of a southern exposure [12]. Previous age estimates for the Caloris exterior plains have been based on CSFD measurements performed across the entire unit (e.g., [7,8]), on a portion of the northwest Caloris exterior plains [9], and on dispersed segments to the east, west, and south of Caloris [12]. The entire area of the Caloris exterior plains in the northwest was not fully counted, nor were targeted counts performed specifically within two contrasting spectral units in the area. A primary motivation for this study is adding targeted crater count-derived ages that include these specific Caloris exterior plains units in order to better constrain the sequence and origin of these units.

3. Materials and Methods

Hypotheses regarding the origin and emplacement of Caloris exterior plains materials were examined via detailed geomorphological-, color-, and compositional-based mapping of the study area (Figure 1C), supplemented by crater counting and interpretation of spectral analyses. Mapping within the study area was used to define the areal extent of the different plains units and their adjacent units, to identify potential structures that could be interpreted as tectonic structures, volcanic vents, or flow structures, and to delineate locations for crater counting. Crater counts were performed in HRP and LBP materials within the study area to refine the emplacement age(s) for the smooth plains in this northwestern segment of the Caloris exterior plains. Spectral analyses were then used to identify compositional similarities and differences between units within the Caloris exterior plains and to identify similar spectral signatures in the adjacent northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains. Spectral analyses were supplemented by a qualitative assessment of previously derived principal component analyses, to further investigate differences between identified spectral units.

3.1. Geomorphological and Color/Compositional Mapping

Geomorphological units that had previously been identified within the circum-Caloris region (cf., [10,11,12]) were delineated within the ESRI ArcGIS 10.8 environment and mapped at a scale of 1:1 M, enabling discrimination of morphological contacts, tectonic structures, and color differences. Prior mapping was performed at a slightly smaller scale, e.g., 1:1.25M (e.g., [12]). Surface morphology was characterized using the Mercury Dual Imaging System (MDIS) [48] 250 m/pixel monochromatic basemap, as this mosaic highlighted brightness differences between units, and was supplemented by available higher-resolution MDIS wide-angle camera (WAC) and narrow-angle camera (NAC) images. The Mercury Laser Altimeter (MLA) [49] 1 km/pixel basemap and the 665 m/pixel global digital elevation map (DEM) [50] supplemented data from visual images to identify the margins of the Caloris exterior plains and surrounding terrains and to further characterize units based on their topography. The MDIS WAC 3-band composite basemap (1000 nm, 750 nm, 430 nm in RGB channels) at 665 m/pixel [51] was used to identify the margins of any spectrally distinct units within and adjacent to the smooth plains basin. This basemap was also used to collect spectra from HRP and LBP units in the Caloris exterior plains, as well as spectra of the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains for comparison with the Caloris exterior plains units. The mapping of color variations was supplemented by the 3-band enhanced color (PC2, PC1, 430/1000 nm in RGB channels) 665 m/pixel basemap [51] that highlights spectral contrasts. Coarse resolution 20 km/pixel X-Ray Spectrometer (XRS) and 100–1000 km/pixel Gamma-Ray Spectrometer (GRS) elemental abundances maps also were used to explore spatial compositional trends (e.g., [31,32,36,37]).

3.2. Crater Counting

To derive model ages for the target LBP and HRP units, crater counts were performed in several distinct locations associated with each spectral unit within the Caloris exterior plains. Craters that are circular, have a raised rim, or retain an ejecta blanket within the chosen sites were counted. The size of the count areas was informed by the minimum ~1000 km2 count area recommended for Martian crater counts; for small areas with small crater populations, this area typically results in statistically significant crater counts [52]. For each location, a minimum area of ~10,000 km2 was used to provide a statistically representative sampling of larger craters (>1 km diameter). Such areas are one to two orders of magnitude smaller than previous regions defined for crater counting (e.g., [14,15]), but are required to satisfy the more spatially focused nature of this investigation and the limited size of the exposures in the Caloris exterior plains. Such small areas, however, restricted counting of craters to below 8–10 km in diameter, though craters below this size are typically dominated by secondary craters on Mercury (e.g., [8]). Count locations were selected to avoid and limit the inclusion of secondary clusters and linear crater chains in the count areas. Defining secondary clusters and linear chains was also instrumental in inferring the potential effect secondary craters might have had on excavating the surface in the study region. Craters that exhibit embayment relationships must predate the observed surface being age-dated and so were excluded, as were craters with non-circular rims and craters in clusters, interpreted as secondaries.

The CraterTools plug-in within ArcGIS was used to perform crater counts [53], and the final crater count model ages were computed in Craterstats2 [54,55] from fits of measured crater distributions to model isochrons, crater production functions, and chronology functions for Mercury [56]. CraterStats2 has been superseded by CraterStats3, but the results of this study would not have been materially affected by the software update. Craters <1 km in diameter were excluded when fitting the observed crater populations to the isochrons, to account for observation loss due to resolution limits, resurfacing processes, and contamination by secondary craters (e.g., [54]).

3.3. Spectral Analyses

The MDIS 3-band enhanced color basemap was used to characterize the spectral properties of the HRP and LBP units in the study area, specifically their spectral slope, which is the measure of the relationship between the reflectance of a surface and the wavelength (λ) of the reflected light. In the ENVI 5.6 image processing software suite, regions of interest (ROIs) were chosen to cover areas of the HRP and LBP units that exhibit distinct color differences within the Caloris exterior plains (Figure 2), as well as similar regions in neighboring northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains terrains, for spectral comparison. Extraction of spectral data from the MDIS multispectral data relied on extracting the average reflectance values for each ROI within the ENVI environment. Although the spectral signatures from the surface of Mercury are typically muted (e.g., [57,58,59]) due to space weathering (e.g., [59,60,61]), low iron content (e.g., [41]), and high concentrations of carbon (e.g., [59,62]), which all act to suppress spectral absorption features, these data are useful for basic first-order comparison of the spectral slopes between units. Results were then compared to previous interpretations of the smooth plains spectral characteristics (e.g., [1,2,30]) and regional elemental abundances determined from XRS and GRS data (e.g., [31,32]), to both determine whether distinct spectral units existed within the Caloris exterior plains and to attempt to distinguish between different exposures of the same spectral class, i.e., the HRPs or LBPs.

3.4. Principal Component Analyses

A qualitative assessment of the previously derived principal component analyses [51,63] was used to supplement spectral interpretations of the units within the Caloris exterior plains, Caloris interior plains, and northern smooth plains. Principal Component Analysis is a statistical technique to reduce the dimensionality of a dataset by transforming the original variables (or bands, in this case) into a new set of variables called principal components. These principal components capture the largest degrees of variation within a given transformed dataset. These principal components highlighted differences between units derived from morphological and color-based mapping. The enhanced color mosaic for Mercury’s surface includes Principal Component 1 (PC1) and Principal Component 2 (PC2) as part of the enhanced color mosaic RGB band combination (R: PC2, G: PC1; B: 430 nm/1000 nm) (e.g., [12,16,27,51,63,64]). Using a spatial subset of the planetary PC2 dataset which highlights compositional differences represented by differences in surface brightness, spectral differences between the mapped spectral units, particularly the widely spaced HRP units, were able to be distinguished. A straightforward comparison of the digital number (DN) values of the pixels associated with the chosen ROIs using the PC2 data, further aided in distinguishing between mapped units. The PC1 data was not utilized for spectral analyses, as it only highlighted the differences in relative reflectance between the units.

4. Results

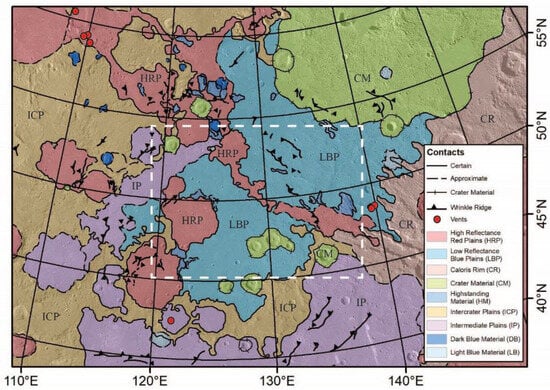

4.1. Geomorphological and Color/Compositional Mapping

Unit delineation based on morphologies, textures, and color characteristics (Figure 2, Table 1) yields a comprehensive map of the region highlighting different units in and around the northwestern Caloris exterior plains (Figure 3). The mapped units in the region generally follow the morphological boundaries, although gradational units (e.g., intercrater and intermediate plains) between the HRP and LRP units and impact related features diverge slightly from these boundaries (Figure 3). The LBP units are generally restricted to within the Caloris exterior plains and also found within multiple nearly filled craters. The HRPs are concentrated within two filled craters and within the arcuate corridor that extends from the distal margins of Timgad and Paestum Valles and extend through the Caloris exterior plains to the Van Eyck formation troughs that dissect the Caloris rim. The Caloris exterior plains lack unambiguous flow structures. The LBPs coincide with most of the Caloris exterior plains, and occur both north and south of the arcuate HRP unit that dissects the Caloris exterior plains. An intermediate plains unit is found in the western margins of the Caloris exterior plains, several filled craters, and south of the exterior plains, consisting of a reddish-blue hued plains unit in the enhanced color composite that appears to be a mix between the HRP and LBP units.

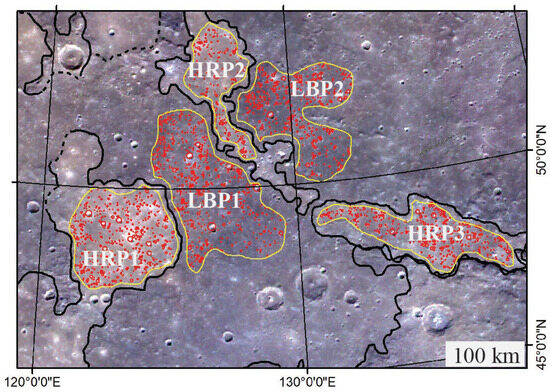

Figure 4.

Crater count locations in the Caloris exterior plains covering the LBP and HRP units. The measurement areas are outlined in yellow, and the counted craters are outlined in red. Figure 2A,D provide examples of the craters that were counted and correspond to count location HRP1. Figure 2B,E correspond to a portion of the count location LBP1.

In addition to the predominant HRP and LBP units, the geomorphologic and/or color-based units identified within and bordering the Caloris exterior plains include ICP, the CR, and HM along the outer margins of the plains. Crater-related outcrops include the large ejecta blanket of Oskison crater to the northeast, and various smaller craters and their associated rims and ejecta (Figure 2, Table 1). The two least common units in the area (LB and DB), though distinct, are areally restricted within the Caloris exterior plains. In addition to the geological units in the Caloris exterior plains, mapping also identified the extent of wrinkle ridges in the region, and the location of several possible volcanic vents (Figure 3). These potential vents correspond to previously identified structures in and around the Caloris exterior plains (e.g., [12,13,25]), and are identified as probable volcanic vents based on their morphology, with broad flat floors, as well as scalloped margins evidencing coalescence [13]. A potential source vent for Dali (see Figure 1) and the adjacent unnamed crater is located in a small bordering filled crater, which is categorized as a mixed plains unit (Figure 3).

4.2. Crater Size–Frequency Distribution Analyses

Crater counting efforts were focused on areas that include distinct HRP and LBP regions (Figure 4) that have previously been interpreted as volcanic or impact units, or a mixture of the two. We delineated crater count locations containing no obvious clusters of secondary impact craters. Though derived from smaller areas and including smaller crater diameters than in previous work, these data—specifically the CSFDs (Figure 5), crater densities, and ages (Table 2)—align with the results of previous investigations (e.g., [7,8,9,12,14,15]). These results suggest that measurements of primary-production crater populations, even in smaller regions and at smaller diameters, can provide a plausible assessment of surface ages for Mercury. In comparison, previous workers attempted to limit contamination from secondary craters by restricting the diameters of the counted craters to ≥4 km [14] or ≥8–10 km (e.g., [9,15]) and removing areas contaminated from their measurement areas.

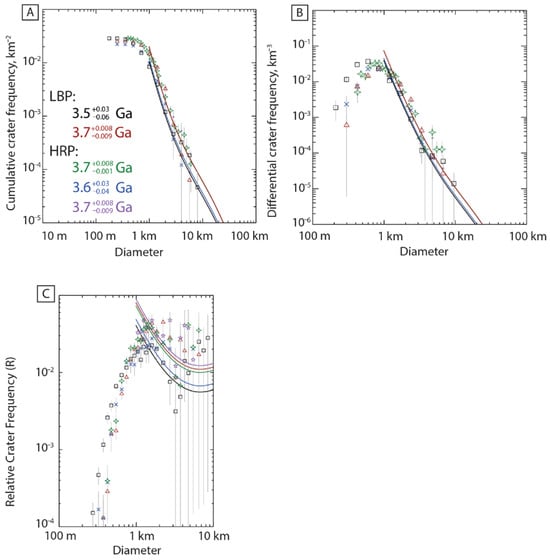

Figure 5.

(A) Cumulative SFDs for the five count locations (Figure 4), with their associated derived absolute model ages. (B) Differential SFDs highlighting the same overlapping pattern as the cumulative SFD display. The cumulative and differential SFDs, and the derived model ages, overlap and are not separable from each other. (C) Relative SFDs indicate that the surfaces were emplaced within a relatively narrow period.

Table 2.

Crater count-derived absolute ages for the LBP and HRP units. The model ages were derived using chronology and production functions for Mercury [56].

Crater counts were used to calculate both absolute and relative ages. Absolute model age estimates for the HRP and LBP range from 3.58 to 3.73 Ga (Table 2), implying that the HRP and LBP units in the region were both emplaced within a span of ~150 My (Table 2); the cumulative and differential CSFDs also suggest overlapping ages for these units (Figure 5). Errors for the model ages derived by CraterStats2 were determined using 1/√n, where n is the total number of counted craters, which provides accurate error estimation for crater populations where n > 20 [65,66]. Although some of the ages might be separated based on these formal errors (Table 2), systemic uncertainties associated with crater counting on Mercury are 100–200 Ma, resulting from the unknown local effects of resurfacing and occurrence of secondary crater populations e.g., [15]. Thus, although it appears certain that the Caloris exterior plains region is younger than the Caloris impact basin, the individual plains unit ages cannot be confidently separated from each other.

As a measure of relative age, crater densities for the HRP and LBP units were also calculated for craters > 4 km (N(4)) in diameter (Equation (1)). This crater diameter enables direct comparison to previous relative age estimates for smooth plains. These N(4) data are similar to previous work in different smooth plains regions over larger areas e.g., [14,15], and do not support distinctly different emplacement times for these two units. The fact that neither relative nor absolute age estimates are separable implies that HRP and LBP unit emplacement occurred either contemporaneously or within a geologically brief timeframe. These relative and absolute age estimates are consistent with previously derived relative and absolute age estimates for similar, but larger count areas, and further support the interpretation that these units were emplaced post-LHB and after the formation of the Caloris impact basin (e.g., [7,8,9,12,14,15]).

Equation (1). The following equation was used to calculate the N(4) to determine the relative ages of the units. The N(D) represents the relative age for a surface with craters greater than or equal to a set diameter (e.g., 4 km). The total number of craters n and surface area A of the count location are input to determine the N(D).

4.3. Spectral Analyses

Though the LBPs and HRPs both have low Fe concentrations that can suppress their overall spectral variability, each have distinct characteristics owing to the differences in their Mg/Si, Ca/Si, and Al/Si ratios, which can be used to distinguish between mafic and ultramafic compositions [33,34,35]. The LBP spectra within the Caloris exterior plains are both similar to each other and to regional exposures of LBP within the Caloris interior plains (Figure 6). There were no LBP exposures in the northern smooth plains for comparisons. The HRP spectra in the Caloris exterior plains, Caloris interior plains, and northern smooth plains exhibit a wider range of reflectance values than those of the LBP spectral units, which show overlapping reflectance values. Spectral comparisons show a small amount of variability in spectral slope of the HRP units in the map area and their similarity to those found in the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains (Figure 6B). The reflectance values of the Caloris exterior plains units are concentrated at the lower end of the HRP reflectance values, suggesting that the HRP units in the Caloris exterior plains are composed of a more intermediate composition (cf. [31,32]).

Figure 6.

(A) Enhanced color mosaic (R: PC2, G: PC1, B: 430 nm/1000 nm) with overlaid ROIs within the Caloris exterior plains, Caloris interior plains, and northern smooth plains. These ROIs cover HRP (red) and LBP (blue) units in each of the three plains regions marked by black outlines. (B) Spectra of the ROIs. The LBP spectra are tightly clustered while the HRP spectra exhibit a greater spread in spectral slopes. (C) The extracted PC2 from the 3-band enhanced color mosaic, highlighting further differences between HRP and LBP units. The location of ROIs from A are represented by open circles, with red representing the HRP and blue representing the LBP. (D) Box and whisker plot of the PC2 for the ROIs. The PC2 values cluster, corresponding to HRP and LBP units, along with an intermediate unit that combines the spectral characteristics of the two. These data suggest distinct spectral differences between the units based on compositional variation. (E) Box and whisker plot of the PC1 for the ROIs. The clustering of these values suggests differences in relative reflectance which may be related to differing physical characteristics, perhaps related to compositional variation.

4.4. Principal Component Analyses

Qualitative assessment of the apparent spectral differences present in the PC2 data were derived from varying brightness of the investigated ROIs. There is clustering of the PC2 values into three distinct spectral populations corresponding to HRP and LBP units, along with a unit that is intermediate between the two (Figure 6D). These variations in the PC2 data indicate potential compositional differences between the HRP and LBP material, consistent with previous observations (e.g., [42]), and highlighted here as the PC2 data transformation is sensitive to spectral differences. The PC2 values for the HRP material in the Caloris exterior plains are intermediate between the HRP values observed in either the northern smooth plains or Caloris interior, as well as lie between those of the HRPs and LBPs. The observation of the PC1 data, which is sensitive to variations in reflectance, suggests that the HRP materials in the Caloris exterior plains are generally darker than the HRP materials found in both the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains (Figure 6E). The PC2 brightness values of the LBP units in the Caloris exterior plains are nearly identical to the LBP unit identified in the Caloris interior plains (Figure 6E). These intermediate brightness values in the PC2 data that are attributed to the HRP material in the Caloris exterior plains lie between the LBP and HRP values identified from the Caloris interior plains and northern smooth plains.

5. Discussion

Our geologic mapping has identified distinct HRP units in the Caloris exterior plains, similar to those found in the Caloris interior plains and northern smooth plains (Figure 3 and Figure 6). The LBP and HRP units identified in the Caloris exterior plains are concentrated in topographic lows, fill craters, and embay the margins of topographically higher terrain. The identification of these distinct HRP units is important, as they correlate to regions, the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains, that have previously been interpreted as being volcanic in origin (e.g., [5,7,8,9,10,11,13,15,17,24,25]). The identification of distinct HRP material in the Caloris exterior plains is suggestive of at least one lava flow in the region (Figure 3). Possible flow pathways from the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains have also been previously identified (e.g., [9,13]), and suggest that lavas could have flowed from either of these potential source areas into the Caloris exterior plains (Figure 1). A potential flow pathway or structure could include the arcuate HRP unit that dissects the Caloris exterior plains (Figure 3). The small vent identified to the east of Dali might represent a potential source for the observed HRP materials in these filled craters, though the vent sits within a crater that is filled by material that is categorized as an IP unit, comprising a potentially compositionally mixed plains unit (Figure 3).

Crater count model ages (Table 2, Figure 5) give a Caloris exterior plains age approximately contemporaneous to the emplacement of the Caloris interior plains and northern smooth plains (~3.7–3.9 Ga) [7,8,9,12,15], and younger than the formation of the Caloris basin (~3.9 Ga) [7,8,9,12]. Thus, the Caloris exterior plains are unlikely to be solely the result of impact ejecta from the formation of the basin.

The slopes of the reflectance values for both the LBP and HRP units identified in the Caloris exterior plains are similar to the LBP and HRP units from the neighboring Caloris interior plains and northern smooth plains (Figure 6B). If the previous interpretations of the HRP materials in the Caloris interior plains and northern smooth plains as extensive lava flows (e.g., [12,15]) are correct, spectral similarities among HRP exposures support the interpretation that the Caloris exterior plains contain lava flows. The spectra of LBP material in the Caloris exterior plains match those of LBP exposures in the Caloris interior plains. These exposures correspond to a unit found in and around craters within the Caloris interior plains, that was likely excavated from depth beneath HRP material (e.g., [1,2,62,64,67]) and has been interpreted to be ancient volcanic materials [33,34,35]. These spectral similarities suggest the LBP in the Caloris exterior plains might also be ancient volcanic material excavated from depth. In contrast to the LBP identified in the Caloris interior plains, the LBP materials in the Caloris exterior plains cover most of the region, may be superposed on or intermixed with HRP material, and cannot be directly related to any specific impact structure that could have excavated the material. The distinct spectral signatures of the LBP and HRP are consistent with previous volcanic interpretations of the smooth plains, and may explain the observed intermediate composition of the Caloris exterior plains [31,32], resulting from a mixture of HRP and LBP units that were blended in the coarse data resolution of the XRS and GRS instruments.

Although the results presented here support a predominantly volcanic emplacement of the Caloris exterior plains, and previous age dating is inconsistent with impact melt or ejecta, other lines of evidence add ambiguity and uncertainty into this interpretation. Potential flow structures may be present within the region (e.g., kipukas), but no unambiguous flow structures were identified within the Caloris exterior plains or within the valleys that fed into the Caloris exterior plains from the northern smooth plains or within the linear Van Eyck troughs, although the absence of observed flow features could also result from insufficient image resolution, impact erosion, or burial by late-stage flows or impact ejecta. The spectra for the HRP units found in the Caloris exterior plains, although similar to those found within the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains, are not diagnostic of having originated in either of these regions. The spectra for the LBP units in the Caloris exterior plains are similar to the exposed LBP material in the interior plains, and based on previous interpretation of LBP material [1,2,62,64,67], these exposures could be representative of either older volcanically emplaced units or excavated material from impacts. The PC2 results suggest multiple compositions (Figure 6D,E), ranging from HRP to LBP and including an intermediate unit between these two endmembers, and are not diagnostic of volcanic processes alone.

Although these results do not distinguish conclusively between lava or impact emplacement of the Caloris exterior plains, they permit multiple scenarios for the origins of the plains units that form the basis of hypotheses that can be tested in subsequent work.

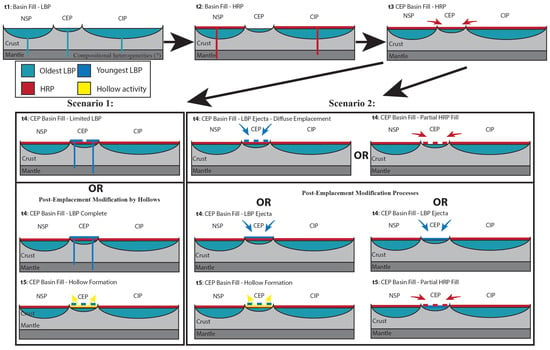

Scenario 1—All Volcanism: In this first scenario for the emplacement of Caloris exterior plains, topographic depressions may have formed first, including the Caloris impact basin, the northern lowlands, and portions of the annulus around Caloris. These depressions were infilled with older, volcanically emplaced LBP material (Figure 7), possibly via now-buried vents or fissures, based on the inference of LBP/LRM deposits at depth (e.g., [1,16,31,62,64,67]). These older volcanic LBP deposits were then covered by deposits of HRP as products of extensive extrusive volcanism (e.g., [12,15]). The compositional differences between the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains (e.g., [31,32,44,45,46]) suggest the HRP deposits within these two regions’ lavas may have been sourced from distinct magmas. Compositional differences between the northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains, particularly the Al-abundance trend, can be plausibly interpreted to result from varying Na concentrations in their source magmas that affected plagioclase production and the final Al concentrations [32]. These compositional variations could also be related to fractional crystallization of a single magma chamber [42]. These HRP lavas were plausibly sourced from the northern smooth plains through valley networks into the Caloris exterior plains [13,25] and/or through the Van Eyck formation rimming the Caloris basin [9]. In this scenario, the separation of the HRP exposures from each other by LBP, or intermingling of these units to form a mixed color unit, may be explained as late-stage and possibly local eruptions of younger LBP material forming a partial veneer over the previously contiguous HRP units. These late-stage LBP deposits could be the result of eruptions preferentially concentrating around a large impact basin where the stress conditions are conducive to providing a conduit for magma ascent in their immediate vicinity [68].

Figure 7.

Various scenarios for the emplacement of the Caloris exterior plains, ranging from predominantly volcanic processes (Scenario 1), to primarily ejecta deposits (Scenario 2), and variations in both scenarios that have been modified by post-emplacement processes. The first (t1), second (t2), and third (t3) steps represent common events for both scenarios. Prior to t1, the topographic depressions that comprise the extent of the Caloris exterior plains, Caloris interior plains, and northern smooth plains formed, either from impact or tectonic events. At t1, these depressions were filled with volcanically derived LBP material, likely fed by vertical conduits plumbing melt zones in the mantle. These melt zones may have been compositionally heterogeneous. These initial conduits closed or the magma sources were exhausted by t2, and were replaced by new conduits sampling different locations and compositions in the mantle, which resulted in HRP material filling the Caloris interior plains and northern smooth plains. In Scenario 1, the HRP material then flowed into the Caloris exterior plains during t3, and was subsequently capped by a limited eruption of volcanically derived LBP material in (t4). An alternative for Scenario 1 would involve complete fill of the Caloris exterior plains by the volcanically derived LBP material during t4, which was then dissected (dashed line) by the formation of hollows (yellow). In Scenario 2, several alternatives are presented. The first two options occur at t3, where the LBP was emplaced as diffuse ejecta deposits (dashed blue line) or emplaced as a continuous layer and partially covered by HRP material (dashed red line). If the LBP was once a continuous surface in the Caloris exterior plains, these ejecta-dominated scenarios must have been modified by post-emplacement processes. If the LBP material was originally continuous at t4, it might have been altered by hollow formation of partial HRP flows in the Caloris exterior plains during (t5). Note: The depressions are not to scale and are meant to convey the general size difference between the adjacent terrains and areally limited Caloris exterior plains.

The development of the Caloris exterior plains might have occurred during multiple pulses of volcanic activity in the region. This supposition is based on the presence of distinct HRP and LBP units in the Caloris exterior plains (e.g., [31,32,33,34]). At least two phases of widespread effusive volcanism that occurred over an extended period of time are inferred in the northern smooth plains, based on stratigraphic embayment relationships of ghost crater populations [15]. The emplacement of the Caloris exterior plains might also have occurred over an extended period of time and, based on analogy to the proposed formation of the northern smooth plains (e.g., [15]), could have involved multiple eruptions. These volcanic pulses might have been triggered by the Caloris basin forming impact event, which could have induced melting in multiple regions within the mantle from remnant thermal anomalies, which later upwelled to the surface ~100 My after the Caloris impact event [43], and continued to form for ~300 My. The different color characteristics of the mapped units and intermediate composition of the Caloris exterior plains [31,32] suggest packets of magma with differing compositions sourced the lavas, although a single fractionated magma chamber could have also produced lavas of different compositions on the surface (e.g., [42]).

If the covering by the potentially younger LBP material was complete over the HRP, a mechanism would be needed to expose the HRP unit. Local landforms that suggest a removal mechanism are hollows, found in the eastern HRP unit (Figure 8). Hollows are small, shallow, irregularly shaped, rimless depressions with flat floors, and inferred to have formed from the loss of volatiles through sublimation processes (Figure 8D) (e.g., [69,70,71,72]) or potentially through fumarole driven sublimation [73]. Although typically found in LBP/LRM deposits, hollows in the Caloris exterior plains have been identified within exposures of HRP material (Figure 8B) (e.g., [1,59,69,70,71,72]). Some additional potential hollows may exist in other HRP units within the Caloris exterior plains, but high-resolution imagery is lacking and their identification would rely solely on their color characteristics that they share with the clearly identifiable hollows as shown here (8B). There are other exposures of these potential hollows in the region as well, though located in the LBP units. The necessary concentration of volatiles is hypothesized to have occurred due to condensation of magmatic volatiles in the subsurface, in cold traps on the surface following their eruption [69,70,71], or beneath a capping layer of lava or pyroclastic deposits [71,72]. Impact melts could also have differentiated and concentrated volatiles following their emplacement [74]. Additionally, volatiles may also be concentrated and sequestered within LBP/LRM units during their formation [71,75]. In this sub-scenario, the localized eruption of LBP material created a veneer that completely covered the HRP material in the Caloris exterior plains and then was locally removed during the formation of hollows (Figure 7). This formation of the hollows could have been triggered by activity of local faults (Figure 8C), or local impacts that exposed the volatile-bearing material to the surface (Figure 8D). The size of hollows would suggest they are not sufficiently large enough to remove a significant amount of surface material, and this possible limitation on their ability to modify the surface must be considered. However, for the sake of considering all potential reasonable hypotheses, we could not discount this option.

Figure 8.

The hollows identified in the CEP are located on the periphery of the HRP unit that corresponds to the crater count area HRP3 and the spectral ROI #5. (A) Regional context of the portion of the annulus that covers the study area. The white dashed box denotes the extent of B and C. (B) Enhanced color imagery showing the location of the hollows in the red-plains unit (white arrows). Note the light-blue characteristics of the hollows. This color characteristic is not easily distinguishable from craters at a distance, but is clearly distinct when zoomed in. (C) B&W image identifying the location of the observed hollows. The hollows are visible in this mosaic, but are more clearly recognizable in the color images in B. (D) Hi-res WAC image covering the highest density cluster of hollows found in the red-plains unit (white arrows).

Scenario 2—Volcanism + Impact Ejecta: A second scenario considers the emplacement of the LBP material as ejecta (Figure 7), perhaps from the formation of the bordering Oskison crater (120 km diameter), which is located in the northwest of the Caloris exterior plains (Figure 1). The local ages derived in the Caloris exterior plains units preclude emplacement as ejecta or melt directly from the Caloris basin formation event, as they are younger than the model ages for the Caloris rim (e.g., [9]). Nevertheless, the LBP in the Caloris exterior plains may be related to Oskison and/or other local or regional impacts. Oskison is a potential candidate due to its proximity to the region and its ejecta blanket encroaching on the northern section of the study area. The exposure of HRP material in the Caloris exterior plains could be related to incomplete, diffuse deposition of this ejecta material over the HRP unit, leaving HRP material exposed and not requiring post-emplacement modification processes to remove any overlying material (Figure 7). Alternatively, the Caloris exterior plains might have been filled with the older volcanically derived LBP material, then partially filled with HRP material after the emplacement of younger LBP ejecta deposits, due either to limited flow into the Caloris exterior plains from the northern smooth plains and/or Caloris interior plains or contributions from localized vents/fissures (Figure 7). These potential sources could have originated within hundreds of kilometers, or within the extent of the Caloris exterior plains (e.g., [13,27]).

If the potentially younger LBP material once covered the entire Caloris exterior plains, then post-emplacement modification would have been necessary (Figure 7). As exposures of HRP material are limited in the Caloris exterior plains, or mixed with LBP material, it is reasonable to infer a once complete coating that had been modified. This modification might have been the result of the flow of HRP material into the Caloris exterior plains from the northern smooth plains or Caloris interior plains that superposed the older volcanic LBP material and younger ejecta-derived LBP. The younger ejecta-derived LBP deposits may represent older volcanically derived LBP deposits that have been excavated and reworked. Alternatively, this modification could have been the result of small impact events or hollow formation that removed some of the overlying material, without completely resurfacing the Caloris exterior plains. This veneer of ejecta material could have been removed through the same processes as the volcanically emplaced LBP material in Scenario 1, although in this second scenario the ejecta material hosted the volatile material. Alternatively, “modern” hollow formation in the last ~1 Ga might have been able to remove a thin LBP veneer, exposing the ancient HRP material without significantly modifying the surface and therefore altering its crater population. This scenario would lead to both the LBP and HRP material having ancient derived ages (~3.7 Ga), though the process that modified them could be far younger.

6. BepiColombo Observations

6.1. Additional Observations for Scenario One

A primary criterion in support of the first scenario would be the identification of flow structures. Examples of flow structures, such as kipukas ranging up to ~20 km long, are found in the Caloris exterior plains-bounding valleys [13] and ~20–50 km long fan-shaped arrays are found within the Caloris basin (e.g., [27]). Structures of this size have not been identified in the study area, but smaller-scale features may be present. Distinguishing impact melt deposits from lavas is difficult, as they have similar morphologies. Impact melts are usually restricted to the interior of craters, or within a few crater radii beyond the rim, which are incorporated in ejecta deposits as coherent bodies and/or isolated outcrops (e.g., [76,77,78,79]). Identification of flow structures that are not in close proximity to large impact craters would support interpretation of the Caloris exterior plains as surficial lava flows. Subdued tectonic structures that constrain either HRP or LBP units would also suggest emplacement of flowing materials like lava. An identification of potential source vents for filled craters would suggest a volcanic origin, similar to the apparent relationship between Dali and an unnamed crater that hosts a small vent structure (Figure 3).

Spectral signatures consistent with volcanic compositions and with the bordering northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains, inferred to have been volcanically emplaced [5,7,8,9,10,11,13,15,17,24], would also support emplacement as lava(s). More definitive spectral characterization of the Caloris exterior plains units, beyond differences in spectral slope (e.g., [1,2,12,59]) would be critical to determining the composition of the units present in the Caloris exterior plains. Alongside the spectral characterization, further investigation of elemental compositions could lead to the identification of source areas. Additional elemental geospatial trends, such as the Al-abundance trend between the Caloris exterior plains, Caloris interior plains, and northern smooth plains observed in MESSENGER data (e.g., [31,32]), could be critical.

Crater counts performed in the region could be refined, which would support more robust geological interpretations through both the refinement of unit boundaries and the inclusion of additional crater count locations. Refinement and expansion of the unit boundaries, however, would allow for better constraints on crater populations which would lead to an increase in overall robustness of model age determinations for specific units. More accurate delineation of additional crater count locations, based on morphological and spectral characteristics, would increase the sample size of locations and their corresponding model ages in the Caloris exterior plains. Counts in HRP units related to the potential flow pathways in the Van Eyck formation and valley networks [9,13] and newly delineated LBP units would better constrain the regional stratigraphy. HRP unit ages that are younger than the Caloris basin and with ages consistent with the bordering northern smooth plains and Caloris interior plains would be supportive of a volcanic interpretation for their emplacement. LBP units younger than the Caloris basin formation event would be consistent with a volcanic emplacement. These potential younger ages would exclude ejecta and melt from the Caloris basin formation event having filled the Caloris exterior plains, but would not definitively exclude later impact events.

6.2. Additional Observations for Scenario Two

A primary criterion for the second scenario, to distinguish whether the Caloris exterior plains units are predominantly ejecta and/or ballistically emplaced melt, would be strongly supported by the identification of superposing deposits that drape highstanding features. Mapped HRP and LBP deposits draped on higher elevation sites would suggest an ejecta origin. Alternatively, if those deposits are restricted to low-lying areas and topographic depressions, their presence would then support a volcanic or melt origin. The small knobs of the Odin formation that are prevalent in the region (e.g., [20]) may be an ideal site to search for any draping deposits that might be present.

A potential further complicating factor for the identification of draping deposits relates to their composition. Draping deposits with spectra consistent with a volcanic composition might be the result of excavation of ancient magmatic material from depth (e.g., [1,2]). In this case, the band centers and depths of absorption features from the spectra may be useful in distinguishing whether the observed material was emplaced on the surface as basalt or in the subsurface as gabbro (e.g., [80]), and then subsequently incorporated into ejecta deposits during an impact event. Additionally, if draped deposits are identified, and have spectral signatures consistent with surficial lava flows, they can be interpreted as ejecta derived from the surface. These spectra might also be useful in identifying any unusual bulk compositions that may contain signatures of the impactor itself [81].

Characterization of the thermal characteristics of the surface, including the thermal inertia (TI), could yield critical distinguishing data. The TI of a surface represents its resistance to temperature change [80]. TI differences may be related to compositional differences between the materials, induration state, grain size, texture, and unit thickness (e.g., [82]). Differences in TI might be useful in distinguishing lava flows from impact ejecta. Typically, a consolidated or crystalline material has a higher TI than a fine-grained material (e.g., [80,82,83,84]), so that TI differences might help distinguish a crystalline lava from a finer-grained ejecta deposit. Ejecta deposits on Mars, Mercury, and the Moon have often been found to have distinct TI from their surroundings (e.g., [85,86,87,88]). Assessing the spatial correlation of any observed TI variations with the mapped unit boundaries would help to determine whether those variations correspond to specific units or whether they are a diffuse coating. This thermal detection method might also provide a way to identify any other potential source craters for ejecta material, besides the neighboring Oskison crater, by tying any observed ejecta deposits to a distinct source crater.

Another avenue to pursue is the clarification of the age relationships in the Caloris exterior plains with a particular emphasis on the LBP units. Current crater count-derived ages (Table 2) suggest the HRP and LBP units were emplaced within a relatively narrow time range. LBP and mixed-plains units are the most morphologically diffuse, similar to potential ejecta deposits, and better constraining their emplacement timing would be used to infer whether any are related to the formation of Caloris, or confirm that they formed well after that impact event. As a supplement to the crater count-derived ages, differences in surface roughness which may be attributable to differences in ages between units (e.g., [89]) could provide an additional proxy for dating the surface. Though any identified roughness differences may correlate to differing ages, these differences may be intrinsic to the units themselves. To avoid this potential issue, a limitation of analyses of the plains units would remove any intermingled units, to ensure comparisons are performed between similar terrains. This approach might further clarify whether adjacent LBP and HRP units are approximately the same age, or if there are distinct differences that would imply unit emplacement was separated in time. Additionally, if any of the results from these techniques identify isolated patches of material that are contemporaneous with the formation of the Caloris basin, this evidence would strongly indicate the contribution of impact ejecta to the filling of the Caloris exterior plains.

6.3. Potential Post-Emplacement Processes

Post-emplacement modification of the plains units might have occurred (Figure 7). In each of the proposed scenarios, various post-plains-emplacement processes altered the main HRP and LBP units, particularly hollow formation and secondary cratering processes. Though these processes do not distinguish between the scenarios proposed for the plains formation mechanisms, they are still important for understanding the subsequent evolution of the plains.

6.3.1. Hollows

The presence of hollows, their genetic relationship to the units that host them, and their potential involvement in surface modification could explain the observed distribution of HRP and LBP units in the Caloris exterior plains, through the removal and/or exposure of surface material. Finding additional locations that host hollows in the Caloris exterior plains, beyond those already identified (Figure 8), would be useful to spatially correlate any identified hollows to the presence of HRP deposits, which would be suggestive of surface modification. A high concentration of either fresh or subdued hollows in the HRP materials would be suggestive of post-emplacement modification by hollows as having disrupted the surface and possibly having removed any overlying LBP material.

As volatile release (e.g., sulfur, sodium, potassium) has been suggested as the driving force leading to the formation of hollows (e.g., [70,72]), any identified volatiles might act as markers and lead to the identification of previously unrecognized hollow populations, especially older subdued hollows. Though volatiles are not exclusive to hollows, for example, volatile activity related to observed pyroclastic deposits (e.g., [24,90]), their presence would be a potential indicator that hollows were/are present in the Caloris exterior plains.

Another consideration when investigating hollows is their age(s). Hollows are inferred to be far younger than Mercury’s surface as a whole, on the basis of the preservation of undisturbed surface features, and may be <1 Ga (e.g., [69]), whereas the ages of the units in the Caloris exterior plains are ~3.7 Ga. Ancient hollows are not observed on Mercury, but may have existed and are no longer discernible, possibly due to their small size, they are relatively short-lived, and easily overprinted on the surface (e.g., [71]). Placing age constraints on the currently observed and prospective hollows in the Caloris exterior plains would assist in understanding the timing of their formation and possible effect on the plains units.

Tectonic structures may offer an initiation point for hollow formation, triggering their volatile release [71,72]. Remapping of tectonic structures in the Caloris exterior plains could provide data to determine whether a geospatial relationship exists with any observed hollows and/or HRP units. Spatial correlation of tectonic structures and hollows would imply that tectonism acted as a driving mechanism related to their formation in the Caloris exterior plains.

6.3.2. Cratering

The results from current mapping of the Caloris exterior plains units and crater counts argue against the contribution of secondary craters being responsible for exposing any surface features. However, their potential effect cannot be completely discounted. High-resolution images from BepiColombo can be used to identify any potential clusters or linear chains of small secondary craters that were previously below the limits of detection of the MDIS data. Identification of linear and clustered secondaries that are confined to within, or truncated by, HRP unit boundaries, would suggest cratering events exposed the HRP material, possibly through the disruption or removal of overlying LBP material.

6.4. BepiColombo Mission Overview and Instrumentation

The BepiColombo mission will arrive at Mercury in 2026 with a primary mission to investigate the magnetic field, magnetosphere, interior, and exterior of Mercury (e.g., [91,92,93]). The spacecraft consists of the Mercury Transfer Module, Mercury Planetary Orbiter (MPO), and the Mercury Magnetospheric Orbiter. The MPO hosts the primary instruments that will investigate the surface of Mercury, orbiting the planet at a periapsis of 480 km and an apoapsis of 1500 km [91], a far less elliptical orbit than that of MESSENGER. Over the course of a primary mission lasting one Earth year, and potential extended mission, BepiColombo’s instruments aboard the MPO will generate both higher-spatial and -spectral resolution data of the surface in the visible, near-infrared, ultraviolet, X-ray, neutron and γ-ray wavelengths, more accurate topographic models, and characterization of mineralogical and elemental compositions compared to the data collected from MESSENGER (Table 3). The visible and near-infrared (VNIR) and thermal infrared (TIR) spectrometers will cover a wider spectral range (0.4–2.0 and 7–14 μm). The camera systems will provide a 50–110 m/pixel color stereo map and 500 m/pixel multispectral map, along with higher-resolution global compositional maps (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparison of instrumentation aboard MESSENGER and BepiColombo. The instruments aboard BepiColombo increase the wavelength range, resolution, and data coverage over that of the MESSENGER instruments. The gray-scale color scheme of the table relates to similar instruments between the MESSENGER and BepiColombo missions.

The instruments aboard the MPO will generate both higher-spatial and -spectral resolution visible, near-infrared, and ultraviolet images of the surface, more accurate topographic models, and characterization of mineralogical and elemental compositions compared to the data collected from MESSENGER (Table 3). The BepiColombo Laser Altimeter (BELA) will better characterize surface elevations and lead to more accurate topographic models across the entire planet [91,92,94]. The Mercury Radiometer and Thermal Infrared Spectrometer (MERTIS) instrument will be used as a mineralogical mapper covering the 7–14 μm spectral range at 500 mpp, and investigate surface temperatures and thermophysical properties [91,92,95]. The Mercury Gamma-ray and Neutron Spectrometer (MGNS) [91,92,96] and Mercury Imaging X-Ray Spectrometer (MIXS) [91,92,97] will map elemental concentrations on the surface, supplementing the mineralogical mapping and previous elemental maps (e.g., [31,32]). The Spectrometer and Imagers for MPO BepiColombo—Integrated Observatory SYStem (SIMBIO-SYS) includes a stereo image system, high-resolution images, and VIS-IR spectrometer that will map Mercury’s surface in unprecedented detail [91,92,98].

7. Conclusions

The results from this work support the interpretation of the smooth plains deposits within the northwestern Caloris exterior plains as at least one distinct lava flow, but are not conclusive, and contributions from impact ejecta cannot be entirely ruled out. These potential lava flows likely originated from the northern smooth plains and/or Caloris interior plains. It is possible that the HRP materials were emplaced prior to late-stage superposition by younger ejecta-derived LBP units. Several possible scenarios which are consistent with the observations from this work were developed to explain the prospective geologic history of Caloris exterior plains. These scenarios may be tested through reinvestigation of MESSENGER data and the acquisition of new data. The understanding of this region will increase significantly with the arrival of BepiColombo and the return of higher-resolution images and spectral data, from which these proposed formation scenarios may be distinguished. With the potential for answering these lingering questions concerning the formation of the Caloris exterior plains with BepiColombo data, a clearer interpretation of the thermal evolution of Mercury may be attained.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B.G.; Methodology, K.B.G., B.J.T., L.R.O., D.M.B., J.P.E. and H.H.; Validation, K.B.G., L.R.O., D.M.B. and J.P.E.; Formal analysis, K.B.G., B.J.T. and D.M.B.; Investigation, K.B.G.; Resources, K.B.G.; Data curation, K.B.G.; Writing—original draft, K.B.G.; Writing—review & editing, K.B.G., B.J.T., L.R.O., D.M.B., J.P.E. and H.H.; Supervision, B.J.T. and D.M.B.; Project administration, K.B.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

L.R.O. acknowledges USGS-NASA Planetary Spatial Data Infrastructure Interagency Agreement NNH22OB02A.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in this work includes various MDIS global mosaics and WAC and NAC images readily available on the Planetary Data System Cartography & Imaging Sciences Node at https://pds-imaging.jpl.nasa.gov/ accessed on 14 December 2025. Several software suites were used, including ArcGIS 10.8, an Esri product, and the ENVI 5.6 spectral software suite, both of which can be downloaded online. CraterTools is a crater counting tool developed by [53] and CraterStats2 is software for fitting absolute model ages by [59,66]. Craterstats2, the version used in this work, has been superseded by Craterstats3, which can be downloaded at https://github.com/ggmichael/craterstats accessed on 14 December 2025. Data derived from this work is available on Zenodo at DOI https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17344204.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments, which improved the manuscript. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Denevi, B.W.; Robinson, M.S.; Solomon, S.C.; Murchie, S.L.; Blewett, D.T.; Domingue, D.L.; McCoy, T.J.; Ernst, C.M.; Head, J.W.; Watters, T.R.; et al. The Evolution of Mercury’s Crust: A Global Perspective from MESSENGER. Science 2009, 324, 613–618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watters, T.R.; Murchie, S.L.; Robinson, M.S.; Solomon, S.C.; Denevi, B.W.; André, S.L.; Head, J.W. Emplacement and tectonic deformation of smooth plains in the Caloris basin, Mercury. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 285, 309–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitten, J.L.; Head, J.W.; Denevi, B.W.; Solomon, S.C. Intercrater plains on Mercury: Insights into unit definition, characterization, and origin from MESSENGER datasets. Icarus 2014, 241, 97–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelms, D.E. Mercurian volcanism questioned. Icarus 1976, 28, 551–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiefer, W.S.; Murray, B.C. The formation of Mercury’s smooth plains. Icarus 1987, 72, 477–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spudis, P.D.; Guest, J.E. Stratigraphy and geologic history of Mercury. In Mercury; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 1988; Volume 1, pp. 118–164. [Google Scholar]

- Strom, R.G.; Chapman, C.R.; Merline, W.J.; Solomon, S.C.; Head, J.W. Mercury Cratering Record Viewed from MESSENGER’s First Flyby. Science 2008, 321, 79–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strom, R.G.; Banks, M.E.; Chapman, C.R.; Fassett, C.I.; Forde, J.A.; Head, J.W.; Merline, W.J.; Prockter, L.M.; Solomon, S.C. Mercury crater statistics from MESSENGER flybys: Implications for stratigraphy and resurfacing history. Planet. Space Sci. 2011, 59, 1960–1967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fassett, C.I.; Head, J.W.; Blewett, D.T.; Chapman, C.R.; Dickson, J.L.; Murchie, S.L.; Solomon, S.C.; Watters, T.R. Caloris impact basin: Exterior geomorphology, stratigraphy, morphometry, radial sculpture, and smooth plains deposits. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 285, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J.W.; Murchie, S.L.; Prockter, L.M.; Solomon, S.C.; Chapman, C.R.; Strom, R.G.; Watters, T.R.; Blewett, D.T.; Gillis-Davis, J.J.; Fassett, C.I.; et al. Volcanism on Mercury: Evidence from the first MESSENGER flyby for extrusive and explosive activity and the volcanic origin of plains. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2009, 285, 227–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, J.W.; Chapman, C.R.; Strom, R.G.; Fassett, C.I.; Denevi, B.W.; Blewett, D.T.; Ernst, C.M.; Watters, T.R.; Solomon, S.C.; Murchie, S.L.; et al. Flood Volcanism in the Northern High Latitudes of Mercury Revealed by MESSENGER. Science 2011, 333, 1853–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Denevi, B.W.; Ernst, C.M.; Meyer, H.M.; Robinson, M.S.; Murchie, S.L.; Whitten, J.L.; Head, J.W.; Watters, T.R.; Solomon, S.C.; Ostrach, L.R.; et al. The distribution and origin of smooth plains on Mercury. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2013, 118, 891–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, P.K.; Klimczak, C.; Williams, D.A.; Hurwitz, D.M.; Solomon, S.C.; Head, J.W.; Preusker, F.; Oberst, J. An assemblage of lava flow features on Mercury. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2013, 118, 1303–1322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, P.K.; Ostrach, L.R.; Fassett, C.I.; Chapman, C.R.; Denevi, B.W.; Evans, A.J.; Klimczak, C.; Banks, M.E.; Head, J.W.; Solomon, S.C. Widespread effusive volcanism on Mercury likely ended by about 3.5 Ga. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2016, 43, 7408–7416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostrach, L.R.; Robinson, M.S.; Whitten, J.L.; Fassett, C.I.; Strom, R.G.; Head, J.W.; Solomon, S.C. Extent, age, and resurfacing history of the northern smooth plains on Mercury from MESSENGER observations. Icarus 2015, 250, 602–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klima, R.L.; Denevi, B.W.; Ernst, C.M.; Murchie, S.L.; Peplowski, P.N. Global Distribution and Spectral Properties of Low-Reflectance Material on Mercury. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2018, 45, 2945–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trask, N.J.; Guest, J.E. Preliminary geologic terrain map of Mercury. J. Geophys. Res. 1975, 80, 2461–2477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oberst, J.; Preusker, F.; Phillips, R.J.; Watters, T.R.; Head, J.W.; Zuber, M.T.; Solomon, S.C. The morphology of Mercury’s Caloris basin as seen in MESSENGER stereo topographic models. Icarus 2010, 209, 230–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuber, M.T.; Smith, D.E.; Phillips, R.J.; Solomon, S.C.; Neumann, G.A.; Hauck, S.A.; Peale, S.J.; Barnouin, O.S.; Head, J.W.; Johnson, C.L.; et al. Topography of the Northern Hemisphere of Mercury from MESSENGER Laser Altimetry. Science 2012, 336, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guest, J.E.; Greeley, R. Geologic Map of the Shakespeare Quadrangle of Mercury; Map I-1408; U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series: Denver, CO, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Oberbeck, V.R.; Quaide, W.L.; Arvidson, R.E.; Aggarwal, H.R. Comparative studies of lunar, Martian, and Mercurian craters and plains. J. Geophys. Res. 1977, 82, 1681–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaber, G.G.; McCauley, J.F. Geologic Map of the Tolstoj Quadrangle of Mercury (H-8); Map I-1199; U.S. Geological Survey Miscellaneous Investigations Series: Denver, CO, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Mccauley, J.F.; Guest, J.E.; Schaber, G.G.; Trask, N.J.; Greeley, R. Stratigraphy of the Caloris basin, Mercury. Icarus 1981, 47, 184–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prockter, L.M.; Ernst, C.M.; Denevi, B.W.; Chapman, C.R.; Head, J.W.; Fassett, C.I.; Merline, W.J.; Solomon, S.C.; Watters, T.R.; Strom, R.G.; et al. Evidence for Young Volcanism on Mercury from the Third MESSENGER Flyby. Science 2010, 329, 668–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurwitz, D.M.; Head, J.W.; Byrne, P.K.; Xiao, Z.; Solomon, S.C.; Zuber, M.T.; Smith, D.E.; Neumann, G.A. Investigating the origin of candidate lava channels on Mercury with MESSENGER data: Theory and observations. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2013, 118, 471–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, J.; Conway, S.J.; Morino, C.; Rothery, D.A.; Balme, M.R.; Fassett, C.I. Modification of Caloris ejecta blocks by long-lived mass-wasting: A volatile-driven process? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2020, 549, 116519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothery, D.A.; Mancinelli, P.; Guzzetta, L.; Wright, J. Mercury’s Caloris basin: Continuity between the interior and exterior plains. J. Geophys. Res. Planets 2017, 122, 560–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]