MAIENet: Multi-Modality Adaptive Interaction Enhancement Network for SAR Object Detection

Highlights

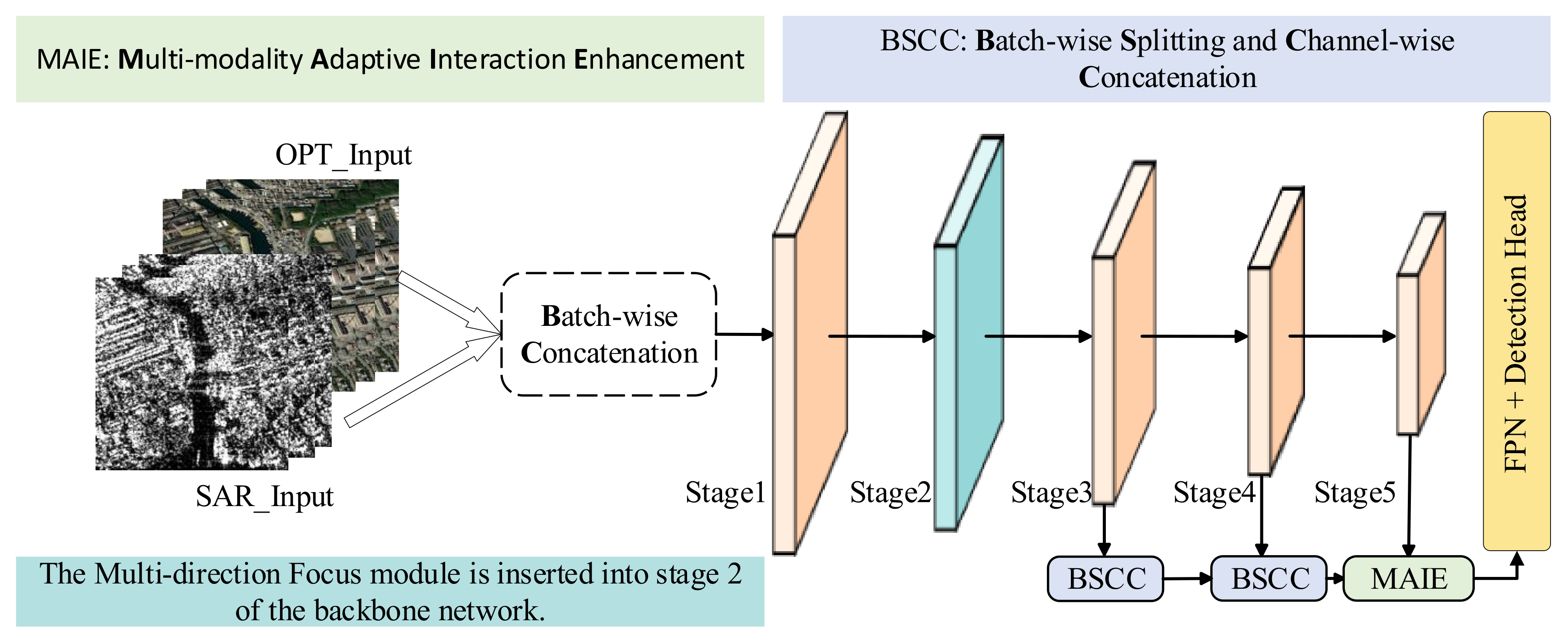

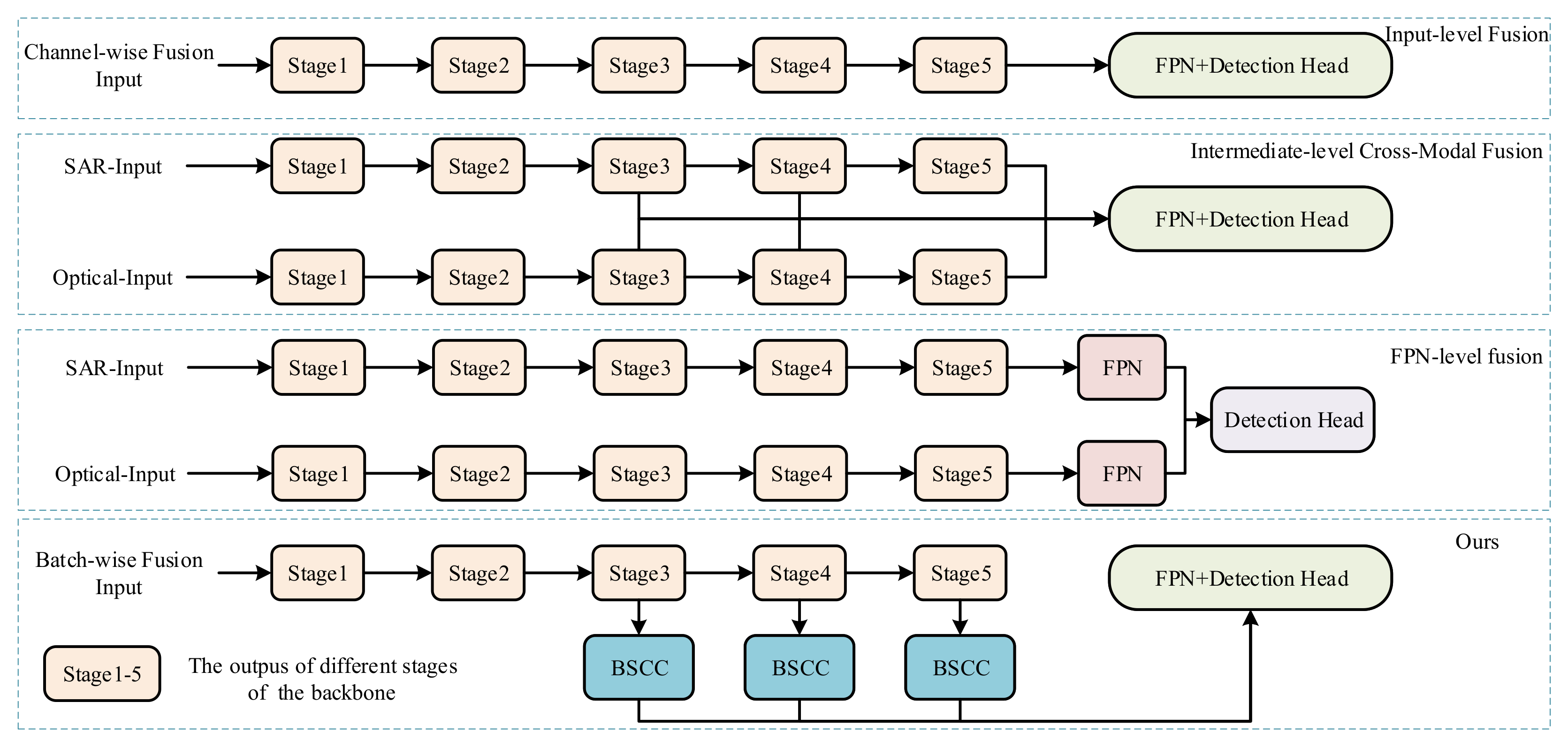

- Developed MAIENet, a single-backbone multimodal SAR object detection framework built upon YOLOv11m, integrating three dedicated modules: BSCC (batch-wise splitting and channel-wise concatenation), MAIE (modality-aware adaptive interaction enhancement), and MF (multi-directional focus). These modules jointly exploit complementary SAR-optical features, delivering mAP50 on the OGSOD-1.0 dataset.

- Compared with leading multimodal benchmarks such as DEYOLO and CoLD, MAIENet achieves superior detection accuracy while retaining fewer parameters than dual-backbone designs, despite necessarily introducing additional parameters relative to the YOLOv11m baseline.

- Demonstrates that carefully designed single-backbone multimodal fusion can outperform both unimodal and dual-backbone multimodal detectors, achieving a better balance between accuracy gains and parameter increments.

- Validates the efficacy of BSCC, MAIE, and MF modules in enhancing cross-modal feature interaction and receptive field coverage, showing their potential for improving detection of diverse target scales (bridges, harbors, oil tanks) in complex SAR-optical remote sensing scenarios.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- We propose a multimodal SAR object detection framework that exploits complementary information from SAR and optical images to boost detection accuracy.

- (2)

- The proposed BSCC module first separates modal-specific features, and then performs channel fusion, which facilitates subsequent unified processing while retaining the features of different modes.

- (3)

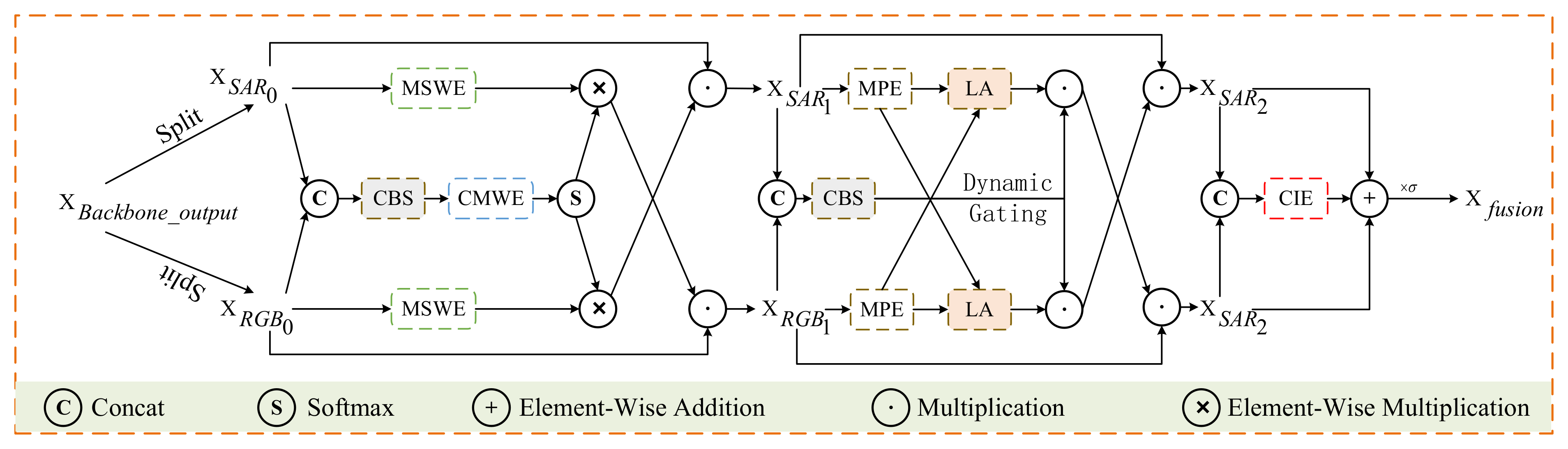

- We introduce the MAIE module to integrate channel reweighting, deformable convolution, atrous convolution, and attention mechanism to achieve deeper cross-modal dual interaction and strengthen feature representation.

- (4)

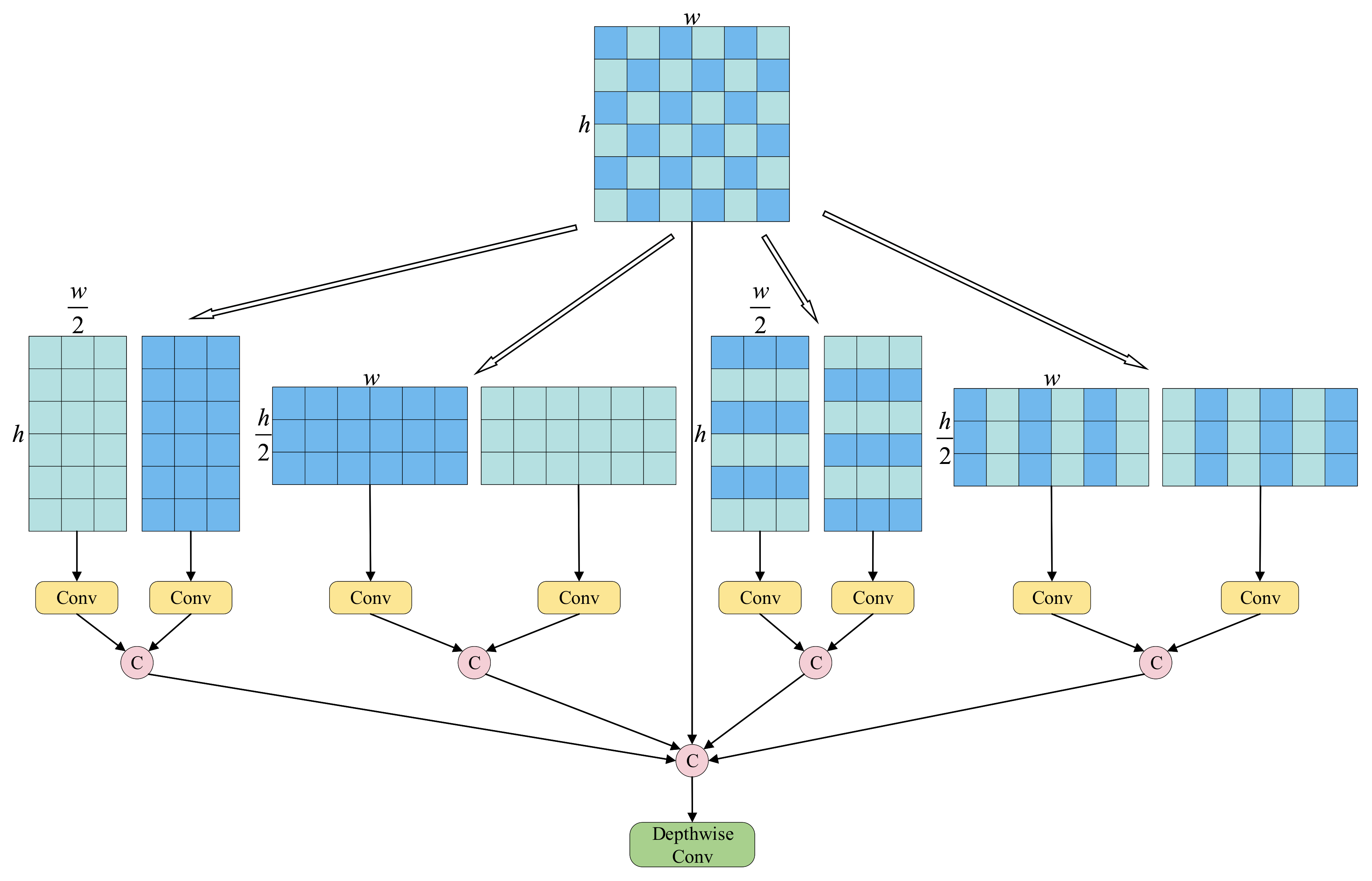

- We propose a MF module to expand the receptive field by aggregating multi-directional spatial contexts, improving robustness in complex environments.

- (5)

- Comprehensive experiments on the public OGSOD-1.0 dataset show that MAIENet outperforms existing methods and effectively utilizes multimodal information to improve object detection performance in challenging scenarios.

2. Related Work

3. Method

3.1. BSCC Module

3.2. MAIE Module

3.3. Multi-Direction Focus

- : horizontal orientation, emphasizing row-wise structures.

- : vertical orientation, emphasizing column-wise structures.

- : main-diagonal orientation, preserving principal diagonal correlations.

- : anti-diagonal orientation, preserving the inverse diagonal patterns.

4. Experiments and Results

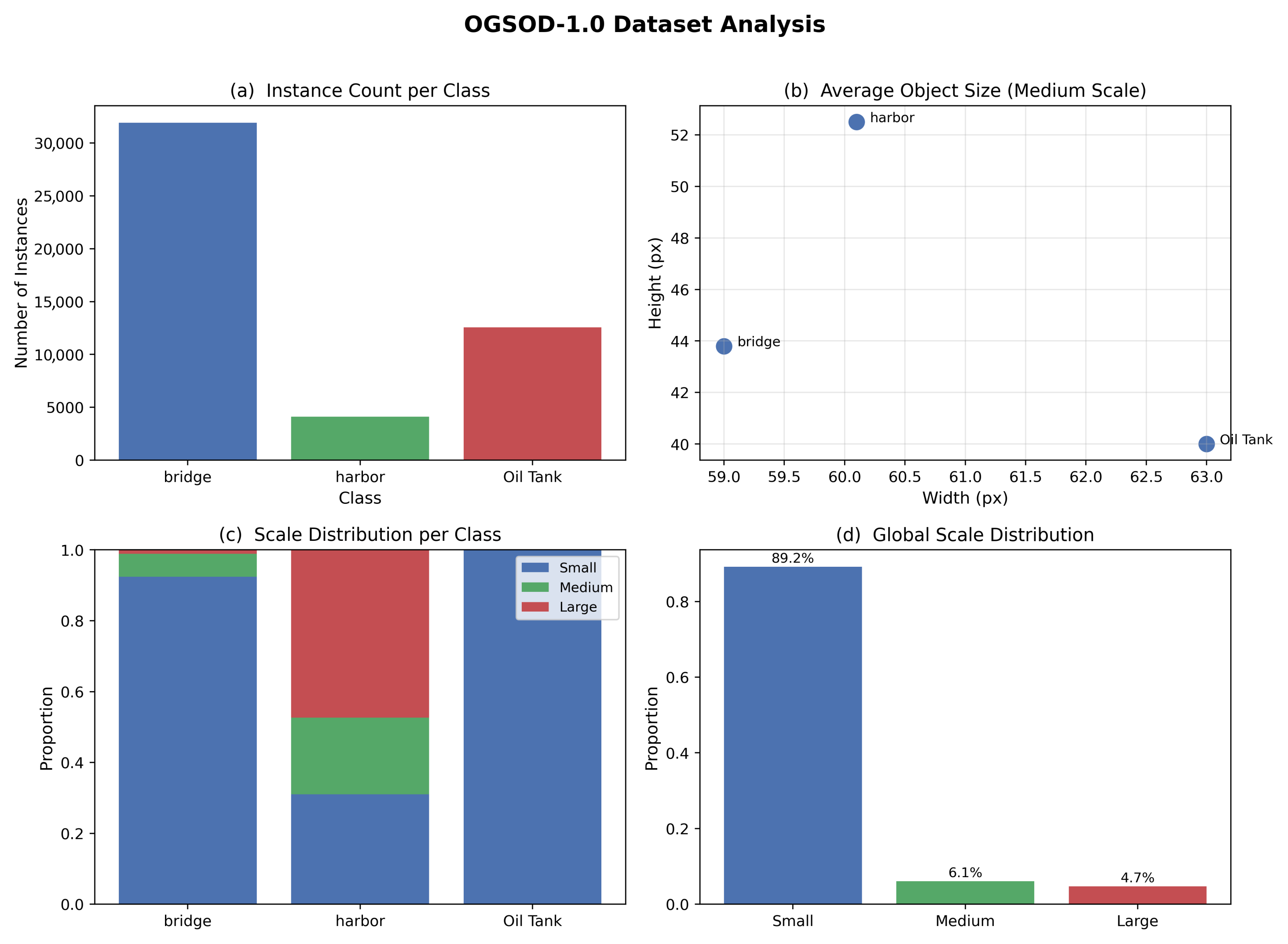

4.1. Datasets

4.2. Experimental Environment

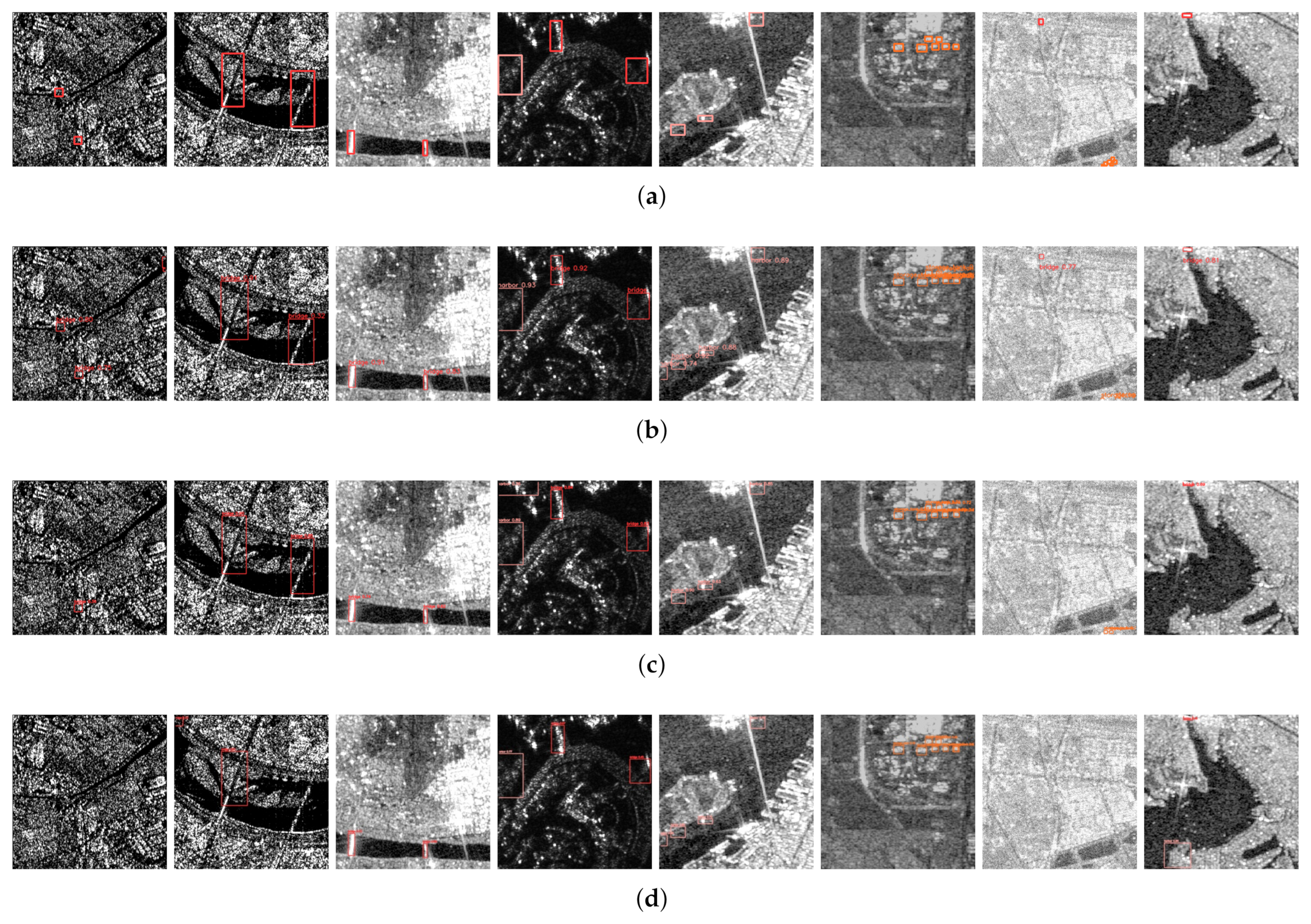

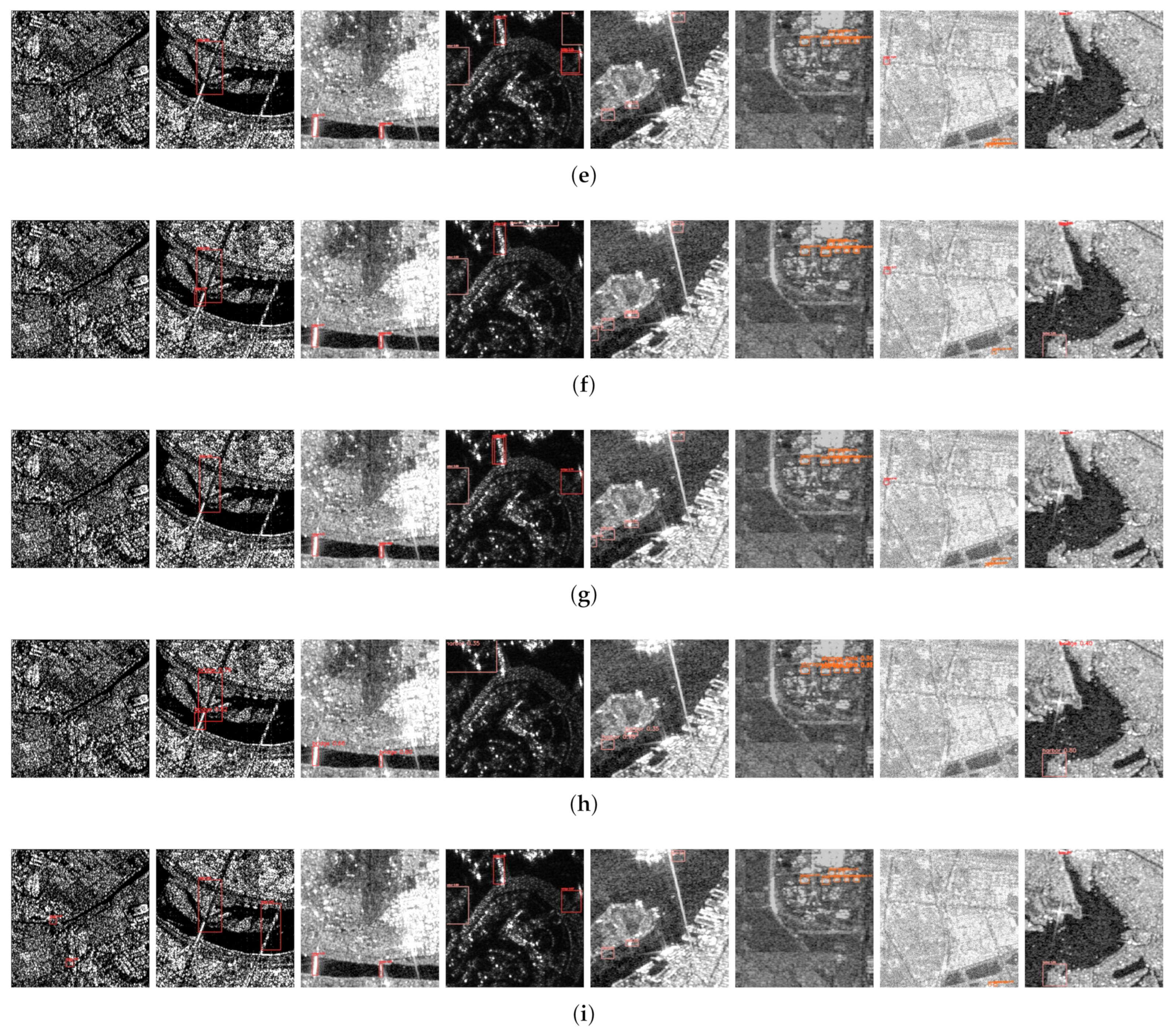

4.3. Results

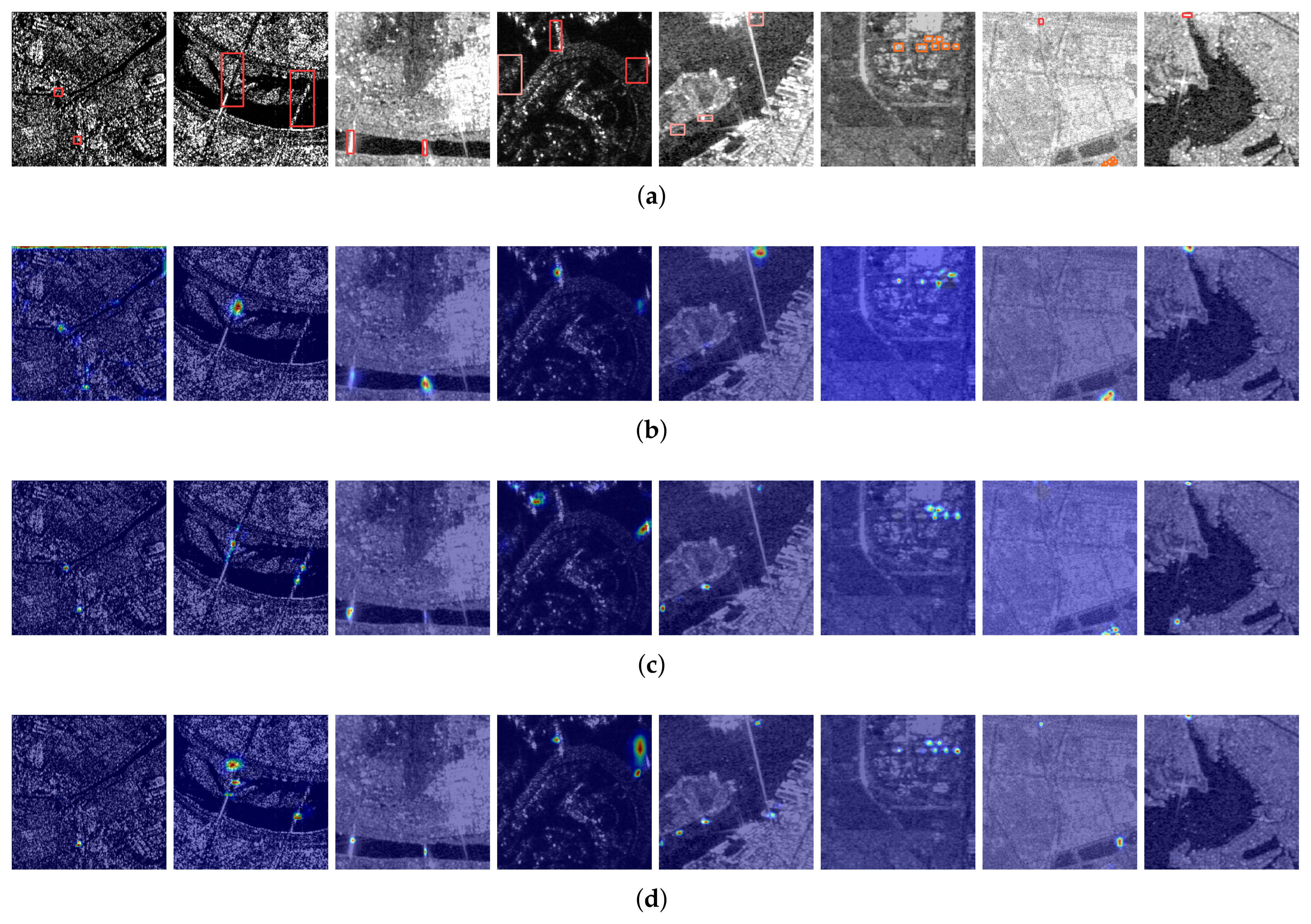

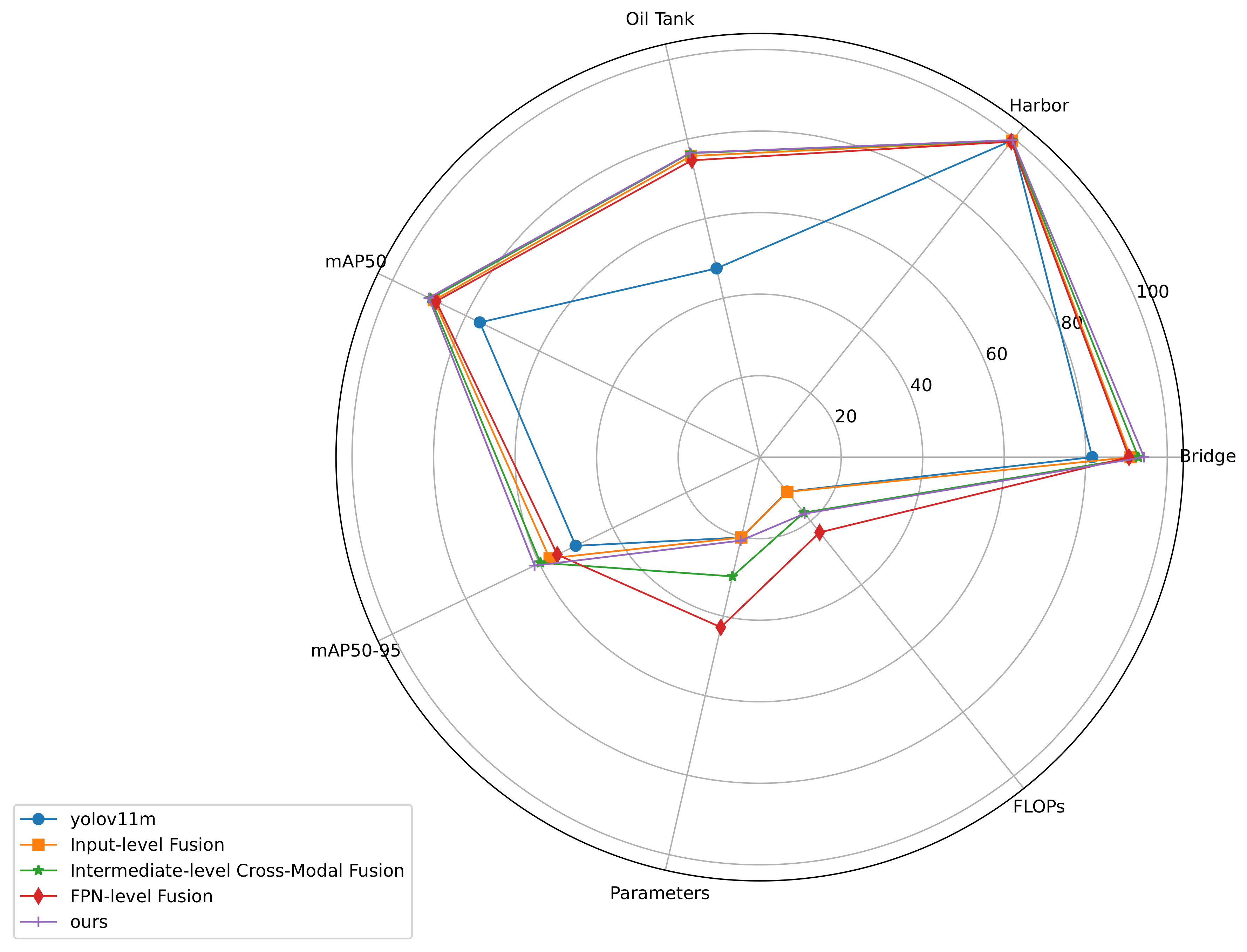

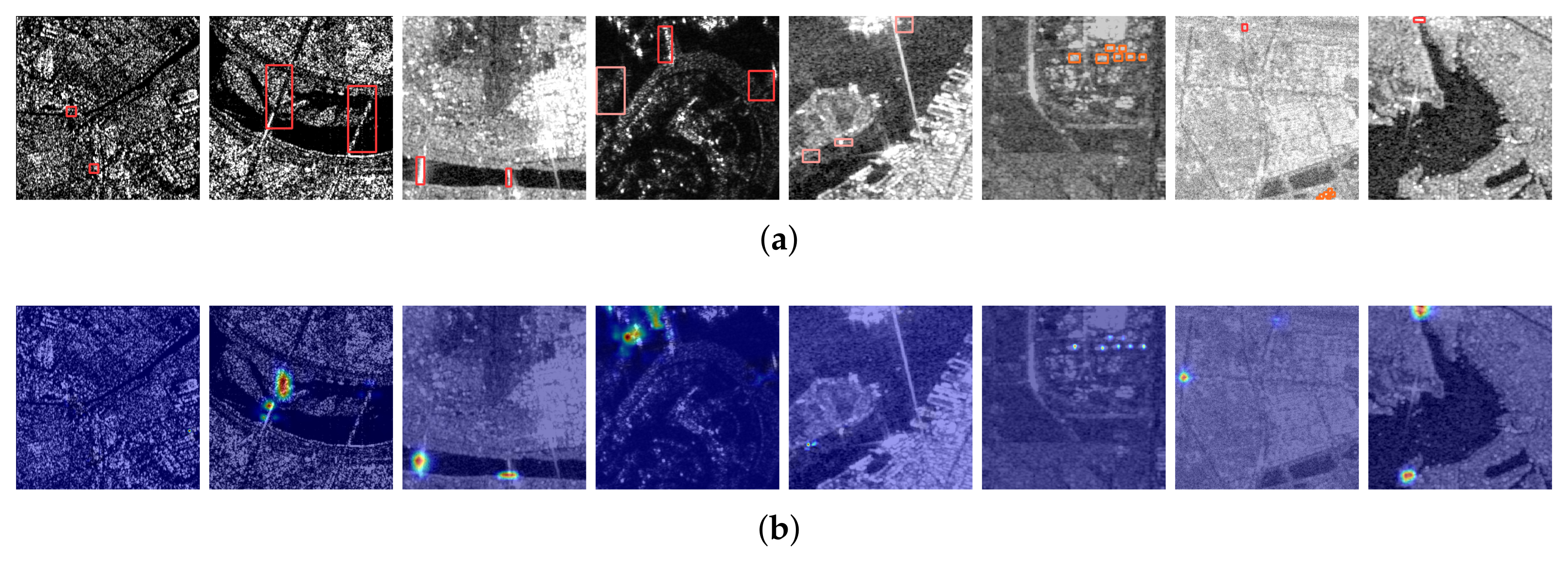

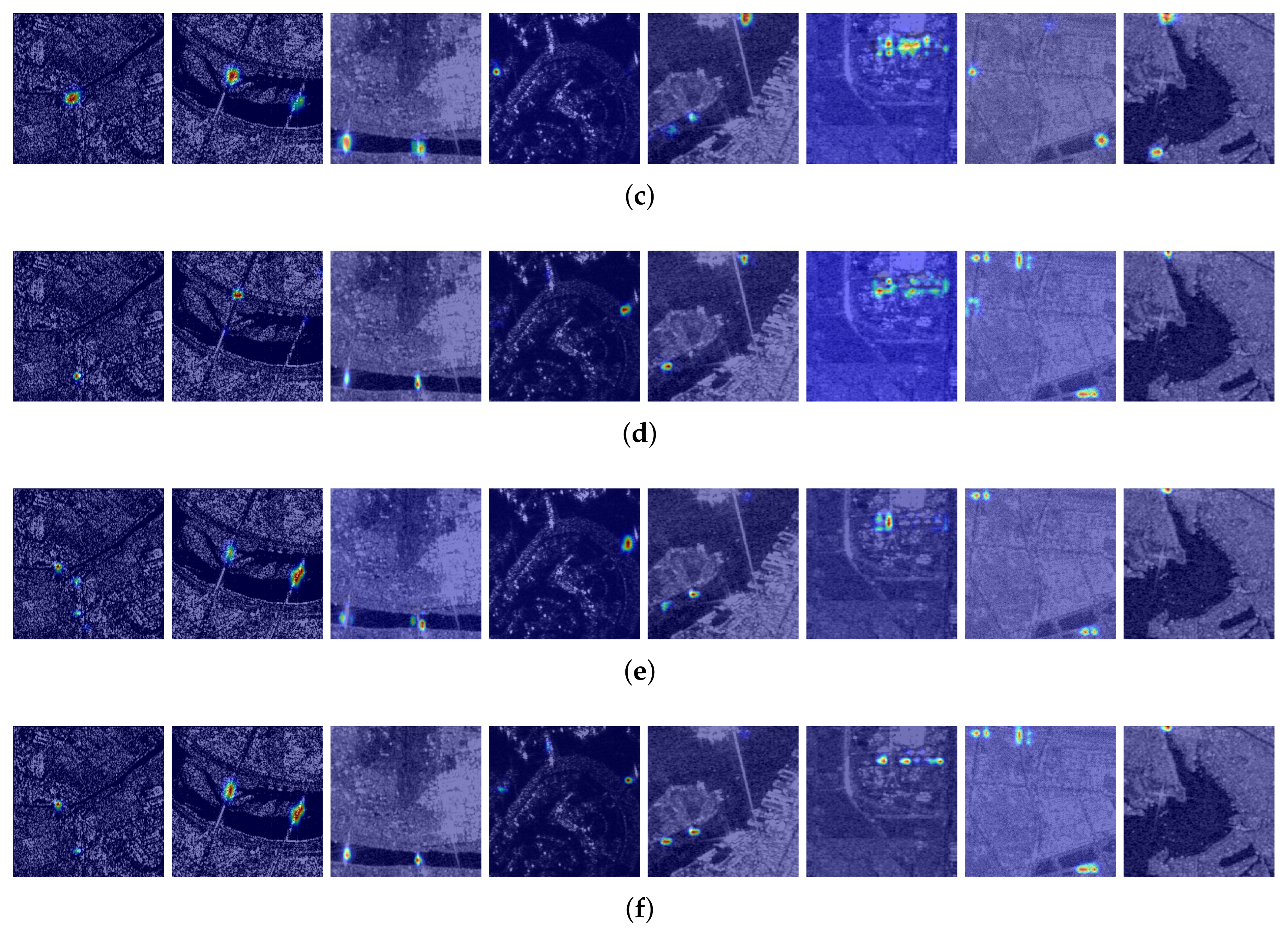

4.3.1. Comparison with Advanced Detectors

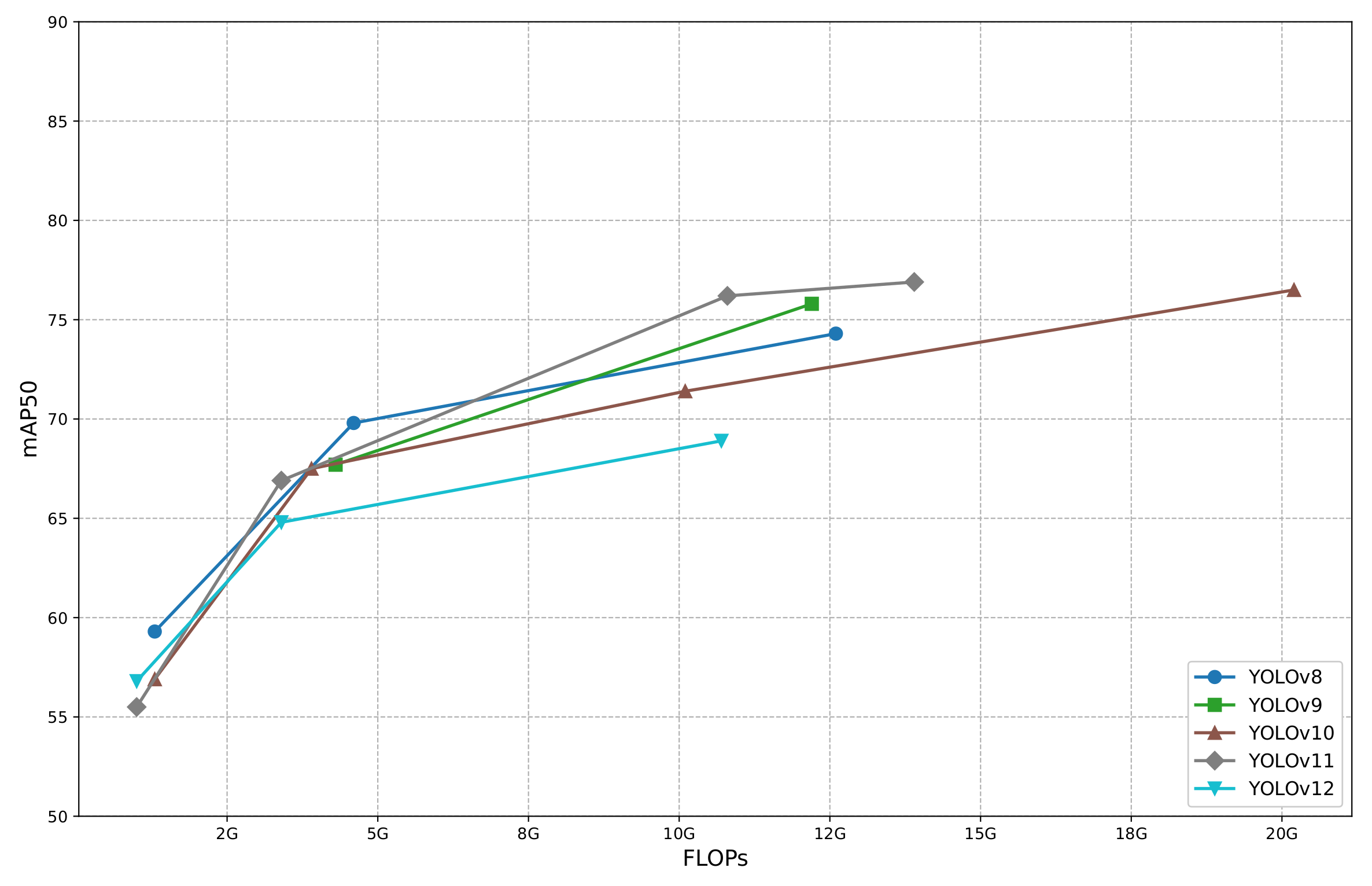

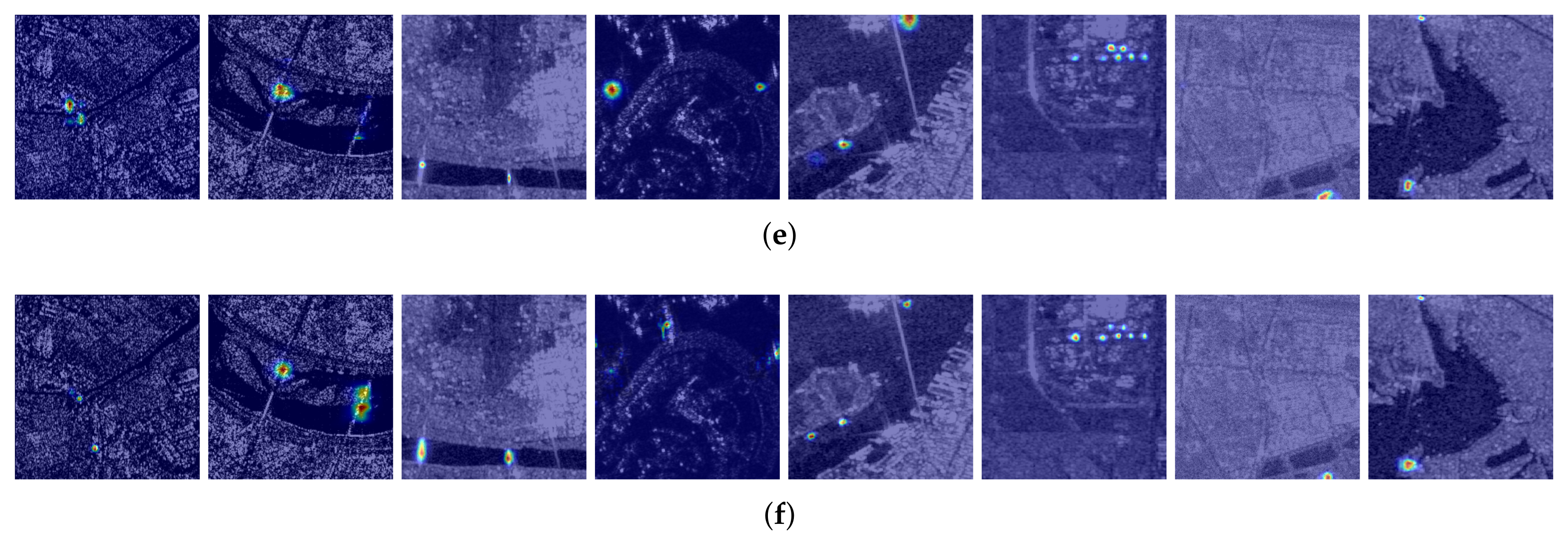

4.3.2. Baseline Model Selection

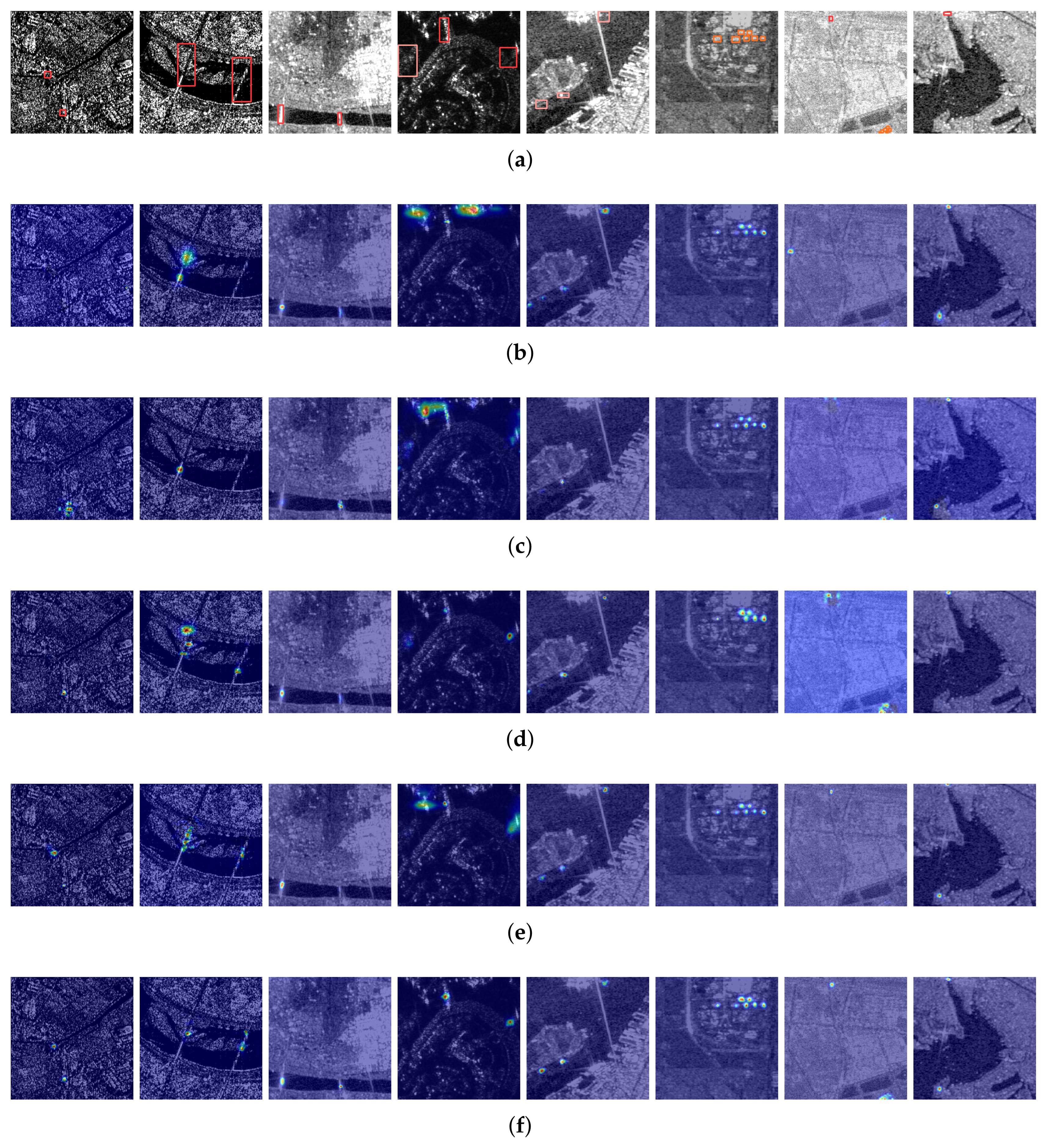

4.3.3. Ablation Studies

4.3.4. Generalization Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cervantes-Hernández, P.; Celis-Hernández, O.; Ahumada-Sempoal, M.A.; Reyes-Hernández, C.A.; Gómez-Ponce, M.A. Combined use of SAR images and numerical simulations to identify the source and trajectories of oil spills in coastal environments. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 199, 115981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, B.; Sui, H.; Liu, J.; Shi, W.; Wang, W.; Xu, C.; Wang, J. Flood inundation monitoring using multi-source satellite imagery: A knowledge transfer strategy for heterogeneous image change detection. Remote Sens. Environ. 2024, 314, 114373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karvonen, J.; Gegiuc, A.; Niskanen, T.; Montonen, A.; Buus-Hinkler, J.; Rinne, E. Iceberg detection in dual-polarized c-band SAR imagery by segmentation and nonparametric CFAR (SnP-CFAR). IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Liu, C. A novel saliency-driven oil tank detection method for synthetic aperture radar images. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020-2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Barcelona, Spain, 4–8 May 2020; pp. 2608–2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Stoken, A.; Borovec, J.; Changyu, L.; Hogan, A.; Diaconu, L.; Poznanski, J.; Yu, L.; Rai, P.; Ferriday, R.; et al. Ultralytics/yolov5: v3. 0. Zenodo YOLO-V5. 2020. Available online: https://zenodo.org/records/3983579 (accessed on 13 August 2020).

- Li, C.; Li, L.; Jiang, H.; Weng, K.; Geng, Y.; Li, L.; Ke, Z.; Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Nie, W.; et al. YOLOv6: A single-stage object detection framework for industrial applications. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2209.02976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Bochkovskiy, A.; Liao, H.Y.M. YOLOv7: Trainable bag-of-freebies sets new state-of-the-art for real-time object detectors. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 7464–7475. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, S.; Shengqi, Y.; Haiying, L.; Jason, G.; Lixia, D.; Lida, L. MIS-YOLOv8: An improved algorithm for detecting small objects in UAV aerial photography based on YOLOv8. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Milan, Italy, 29 September–4 October 2024; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, A.; Chen, H.; Liu, L.; Chen, K.; Lin, Z.; Han, J. Yolov10: Real-time end-to-end object detection. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2024, 37, 107984–108011. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, C.; Filaretov, V.F.; Yukhimets, D.A. Multi-Scale ship detection algorithm based on YOLOv7 for complex scene SAR images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Ma, H.; Guo, Z. MAEE-Net: SAR ship target detection network based on multi-input attention and edge feature enhancement. Digit. Signal Process. 2025, 156, 104810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhan, R.; Wang, W.; Zhang, J. Deformable feature fusion and accurate anchors prediction for lightweight SAR ship detector based on dynamic hierarchical model pruning. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Appl. Earth Obs. Remote Sens. 2025, 18, 15019–15036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, S.; Sohn, K. Enriching SAR ship detection via multistage domain alignment. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Guo, H.; Xu, F.; Yang, W.; Yu, H.; Zhang, H.; Xia, G.S. Optical-enhanced oil tank detection in high-resolution SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Y.; Du, L.; Guo, Y.; Du, Y. Unsupervised domain adaptation based on progressive transfer for ship detection: From optical to SAR images. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2022, 60, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ruan, R.; Zhao, Z.; Li, C.; Tang, J. Category-oriented localization distillation for sar object detection and a unified benchmark. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, J.; Xu, G.; Zhu, Y.; Liang, B.; Yang, D. Ship target detection algorithm based on decision-level fusion of visible and SAR images. IEEE J. Miniaturization Air Space Syst. 2023, 4, 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, B.; Guo, X.; Zhu, W.; He, J.; Liu, X.; Yuan, J. DEYOLO: Dual-feature-enhancement YOLO for cross-modality object detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Pattern Recognition, Kolkata, India, 1–5 December 2025; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 236–252. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Zuo, X.; Fan, H.; Yang, W. ICAFusion: Iterative cross-attention guided feature fusion for multispectral object detection. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 145, 109913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.; Xue, X.; Wen, H.; Ji, Y.; Yan, Y.; Meng, Q. Misaligned visible-thermal object detection: A drone-based benchmark and baseline. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 7449–7460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Bin, J.; Hamari, J.; Blasch, E.; Liu, Z. Multimodal object detection by channel switching and spatial attention. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops (CVPRW), Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 403–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, S.; Bai, H.; Jiang, L.; Zhou, X.; Duan, X.; Ma, Y.; Zhou, Z. SCL-YOLOv11: A lightweight object detection network for low-illumination environments. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 47653–47662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chi, C.; Yao, Y.; Lei, Z.; Li, S.Z. Bridging the gap between anchor-based and anchor-free detection via adaptive training sample selection. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 9756–9765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zand, M.; Etemad, A.; Greenspan, M. Objectbox: From centers to boxes for anchor-free object detection. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 390–406. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, S.; Hu, H.; Wang, L.; Lin, S. RepPoints: Point set representation for object detection. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October 27–2 November 2019; pp. 9656–9665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Zhang, R.; Jiang, Y.; Kong, T.; Xu, C.; Zhan, W.; Tomizuka, M.; Li, L.; Yuan, Z.; Wang, C.; et al. Sparse R-CNN: End-to-end object detection with learnable proposals. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 14449–14458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yang, W.; Hou, Y.; Liu, L.; Liu, Y.; Li, X. SARATR-X: Toward building a foundation model for SAR target recognition. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2025, 34, 869–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Han, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Li, Y. Blurry dense SAR object detection algorithm based on collaborative boundary refinement and differential feature enhancement. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2025, 46, 3207–3227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. Detrs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, J.H.; Yeo, D.; Yim, J.; Kim, N.S.; Pyo, C.S.; Kim, J. Densely distilled flow-based knowledge transfer in teacher-student framework for image classification. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2020, 29, 5698–5710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Jiang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Bao, Y.; Wang, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhou, E. General instance distillation for object detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7838–7847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, B.; Cui, Q.; Song, R.; Qiu, Y.; Liang, J. Decoupled knowledge distillation. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 11943–11952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Ye, R.; Wang, P.; Ren, D.; Zuo, W.; Hou, Q.; Cheng, M.M. Localization distillation for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 9397–9406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Methods | Year | Modality | Params | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridge | Harbor | Oil Tank | ||||||

| YOLOv3 | 2018 | SAR | 76.0 | 97.0 | 32.4 | 68.5 | 39.5 | 61.5 M |

| RepPoints | 2019 | SAR | 78.0 | 96.3 | 26.2 | 66.8 | 38.6 | 36.6 M |

| ATSS | 2020 | SAR | 70.8 | 95.4 | 30.4 | 65.5 | 37.9 | 50.8 M |

| YOLOv5 | 2020 | SAR | 87.2 | 97.9 | 57.7 | 80.9 | 46.3 | 86.2 M |

| Sparse R-CNN | 2021 | SAR | 73.8 | 94.2 | 28.7 | 65.6 | 38.7 | 124.9 M |

| ObjectBox | 2022 | SAR | 82.4 | 96.5 | 51.0 | 76.6 | 40.1 | 86.1 M |

| YOLOv7 | 2022 | SAR | 79.8 | 98.1 | 59.7 | 79.2 | 45.1 | 97.2 M |

| YOLOv8m | 2023 | SAR | 77.0 | 98.8 | 47.0 | 74.3 | 48.2 | 25.8 M |

| RT-DETR | 2024 | SAR | 90.3 | 99.1 | 72.2 | 87.2 | 49.7 | 42.0 M |

| YOLOv9m | 2024 | SAR | 81.8 | 99.4 | 46.2 | 75.8 | 15.6 | 20.0 M |

| YOLOv10m | 2024 | SAR | 73.3 | 97.7 | 43.1 | 71.4 | 45.7 | 16.5 M |

| YOLOv11m | 2024 | SAR | 81.6 | 99.4 | 47.5 | 76.2 | 50.1 | 20.2 M |

| YOLOv12m | 2025 | SAR | 72.3 | 96.4 | 37.9 | 68.9 | 42.8 | 20.1 M |

| CoDeSAR | 2025 | SAR | 86.9 | 98.9 | 76.5 | 87.4 | 56.8 | 45.9 M |

| YOLOv5 | 2020 | RGB | 87.4 | 99.0 | 73.6 | 86.7 | 53.2 | 86.2 M |

| YOLOv8m | 2023 | RGB | 88.8 | 98.5 | 73.7 | 87.0 | 55.1 | 25.8 M |

| YOLOv9m | 2024 | RGB | 90.2 | 98.7 | 73.7 | 87.6 | 56.4 | 20.0 M |

| YOLOv10m | 2024 | RGB | 87.4 | 98.5 | 72.1 | 86.0 | 54.1 | 16.5 M |

| YOLOv11m | 2024 | RGB | 90.6 | 99.1 | 74.3 | 88.0 | 57.0 | 20.2 M |

| YOLOv12m | 2025 | RGB | 89.3 | 99.1 | 73.5 | 87.3 | 55.6 | 20.1 M |

| KD | 2020 | Cross-modal | 88.4 | 98.8 | 60.3 | 82.6 | 48.4 | 86.2 M |

| LD | 2022 | Cross-modal | 90.1 | 98.3 | 65.7 | 84.5 | 51.9 | 86.2 M |

| CoLD | 2023 | Cross-modal | 93.5 | 99.5 | 69.8 | 87.6 | 56.7 | 86.2 M |

| CSSA | 2023 | Multimodal | 88.7 | 98.7 | 71.1 | 86.2 | 52.9 | 13.2 M |

| CMADet | 2024 | Multimodal | 88.3 | 98.9 | 61.8 | 83.0 | 52.6 | 41.2 M |

| ICAFusion | 2024 | Multimodal | 89.9 | 98.6 | 70.7 | 86.4 | 54.5 | 28.7 M |

| DEYOLOm | 2025 | Multimodal | 92.7 | 99.1 | 77.1 | 89.7 | 59.5 | 48.7 M |

| MAIENet (ours) | 2025 | Multimodal | 93.8 | 99.4 | 79.0 | 90.8 | 61.0 | 34.0 M |

| MF | BSCC | MAIE | Parameters | FLOPs | FPS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridge | Harbor | Oil Tank | ||||||||

| 81.6 | 99.4 | 47.5 | 76.2 | 50.1 | 20.2 M | 10.8 G | 75.8 | |||

| ✓ | 86.8 | 99.5 | 58.2 | 81.5 | 53.5 | 21.0 M | 15.4 G | 70.4 | ||

| ✓ | 91.0 | 99.3 | 75.8 | 88.7 | 57.2 | 20.9 M | 17.7 G | 72.5 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | 93.6 | 99.4 | 77.0 | 90.0 | 59.9 | 33.0 M | 18.4 G | 40.3 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 93.8 | 99.4 | 79.0 | 90.8 | 61.0 | 34.0 M | 27.6 G | 38.6 |

| PSA Module | Params | FLOPs | FPS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridge | Harbor | Oil Tank | ||||||

| ✓ | 93.3 | 99.4 | 78.4 | 90.4 | 60.2 | 34.9 M | 27.9 G | 34.7 |

| × | 93.8 | 99.4 | 79.0 | 90.8 | 61.0 | 34.0 M | 27.6 G | 38.6 |

| Stage4 | Stage5 | Parameters | FLOPs | FPS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridge | Harbor | Oil Tank | |||||||

| ✓ | 93.5 | 99.4 | 79.3 | 90.7 | 60.3 | 101.7 M | 30.8 G | 30.5 | |

| ✓ | ✓ | 92.8 | 99.5 | 77.9 | 90.1 | 59.6 | 114.7 M | 31.8 G | 28.7 |

| ✓ | 93.8 | 99.4 | 79.0 | 90.8 | 61.0 | 34.0 M | 27.6 G | 38.6 | |

| Methods | MF | BSCC | MAIE | Parameters | FLOPs | FPS | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bridge | Harbor | Oil Tank | |||||||||

| YOLOv10m | 73.3 | 97.7 | 43.1 | 71.4 | 45.7 | 16.5 M | 10.1 G | 68.5 | |||

| ✓ | 80.9 | 97.9 | 50.7 | 75.6 | 48.2 | 17.1 M | 12.7 G | 62.1 | |||

| ✓ | 90.3 | 99.3 | 72.6 | 87.4 | 56.8 | 20.6 M | 17.3 G | 67.6 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 91.7 | 99.4 | 74.8 | 88.6 | 58.6 | 35.3 M | 18.2 G | 37.3 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 91.6 | 99.2 | 75.3 | 88.7 | 58.8 | 36.0 M | 23.3 G | 36.0 | |

| YOLOv12m | 72.3 | 96.4 | 37.9 | 68.9 | 42.8 | 20.1 M | 10.7 G | 64.1 | |||

| ✓ | 80.9 | 98.3 | 51.5 | 76.9 | 48.7 | 21.0 M | 15.4 G | 59.5 | |||

| ✓ | 91.5 | 99.3 | 73.0 | 87.9 | 55.7 | 20.7 M | 17.9 G | 62.9 | |||

| ✓ | ✓ | 92.7 | 99.3 | 74.3 | 88.7 | 58.6 | 34.0 M | 19.0 G | 34.0 | ||

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 92.4 | 99.4 | 77.4 | 89.7 | 59.3 | 35.0 M | 28.2 G | 33.2 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tong, Y.; Xiong, K.; Liu, J.; Cao, G.; Fan, X. MAIENet: Multi-Modality Adaptive Interaction Enhancement Network for SAR Object Detection. Remote Sens. 2025, 17, 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233866

Tong Y, Xiong K, Liu J, Cao G, Fan X. MAIENet: Multi-Modality Adaptive Interaction Enhancement Network for SAR Object Detection. Remote Sensing. 2025; 17(23):3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233866

Chicago/Turabian StyleTong, Yu, Kaina Xiong, Jun Liu, Guixing Cao, and Xinyue Fan. 2025. "MAIENet: Multi-Modality Adaptive Interaction Enhancement Network for SAR Object Detection" Remote Sensing 17, no. 23: 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233866

APA StyleTong, Y., Xiong, K., Liu, J., Cao, G., & Fan, X. (2025). MAIENet: Multi-Modality Adaptive Interaction Enhancement Network for SAR Object Detection. Remote Sensing, 17(23), 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/rs17233866