Abstract

This paper reviews the scientific motivation and challenges, development, and use of underwater robotic vehicles designed for use in ice-covered waters, with special attention paid to the navigation systems employed for under-ice deployments. Scientific needs for routine access under fixed and moving ice by underwater robotic vehicles are reviewed in the contexts of geology and geophysics, biology, sea ice and climate, ice shelves, and seafloor mapping. The challenges of under-ice vehicle design and navigation are summarized. The paper reviews all known under-ice robotic vehicles and their associated navigation systems, categorizing them by vehicle type (tethered, untethered, hybrid, and glider) and by the type of ice they were designed for (fixed glacial or sea ice and moving sea ice).

1. Introduction

This paper seeks to review the scientific motivation, challenges, development, and use of underwater robotic vehicles designed for diving in ice-covered waters, with special attention paid to the navigation systems employed for under-ice deployments. The world’s oceans cover 71% of the Earth’s surface, 12% of which is largely inaccessible to scientific research due to being covered by ice all or part of the year. In the Northern Hemisphere, sea ice coverage varies seasonally from 102% to 192% the size of the United States, and in the Southern Hemisphere sea ice coverage varies seasonally from 39% to 260% the size of Australia (equivalently 30% to 205% the size of the United States) [1].

Few methods presently exist for routine deep water and benthic survey and sampling operations under ice in high latitudes. In contrast, present day blue-water oceanographic methods for survey and sampling are extensive—they include ship-based sensing; lowered and towed instruments such as dredges, Conductivity Temperature Depth (CTD) instruments, and deep-tows tethered Remotely Operated Vehicles (ROVs); and untethered vehicles such as Human Occupied Vehicles (HOVs), Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs), and Hybrid Remotely Operated Vehicles (HROVs). Only a few of these methods, principally vertically lowered instruments deployed from icebreaking ships, e.g., in [2], or from ice camps, e.g., in [3], are regularly practiced for under-ice sampling and survey operations. It remains difficult to effectively employ most open water methods in ice-covered high-latitude seas because of the constrained maneuverability inherent in icebreaker operations. Over-the-side deployments of lowered instruments generally prohibit ice-breaking and constrain the ship to the wind-driven motion of the ice. Even then, drifting sea ice is a threat to the cables used to deploy the instrumentation. The first reported attempts of scientific observation beneath ice-covered waters involved depth and hydrographic measurements (Nansen’s 1893–1896 Fram Expedition [4]) and, in the 20th century, the analysis of sonar measurements and officer’s cruise reports from military submarine missions dating back to the 1950s [5]. Even in the present day, large parts of polar seafloor remain uncharted [6,7]. Hydrographic mesoscale structures and processes, like ocean fronts and eddies, upwelling, and downwelling, requiring 3D surveys by AUVs are extremely difficult to realize under the ice [8,9]. Likewise, the discovery and observation of polar life, which contains a high proportion of endemic species, remains an important task [10]. Very little is known about the specific adaptations of polar life to its extreme habitat. Understanding these is critical in the face of rapid climate change and sea ice decline [11].

New methods for surveying and sampling under permanent moving sea ice are needed to address a range of critically important geologic, biologic, geochemical, oceanographic, and climatic problems. For example, ultra-slow Mid-Ocean Ridges (MORs) occur in geographic regions where weather windows are extremely narrow or there is ice cover (e.g., the Southwest Indian Ridge and the Gakkel Ridge). With the recent identification of hydrothermal vents during first-order mapping studies of these ultra-slow spreading ridges [2,12,13,14,15], scientists are poised to make breakthroughs in our understanding of this important end-member of the sea floor spreading environment. The ability to sample and observe detailed geological, biological, and chemical processes occurring at the slowest spreading MORs could revolutionize our understanding of how sea floor spreading is manifested in these settings. In addition, a host of new and novel biological communities and chemical/biochemical processes may be associated with ultra-slow spreading MORs.

New methods for surveying and sampling under glacial ice shelves are needed to provide scientific access to the water column, sea floor, grounding line, and underside of the ice shelves, which remain among the least explored frontiers worldwide. These cavities under ice shelves host poorly understood processes that control most of the global sea level uncertainty over the next decades to century [16]. A preliminary draft of Section 3, Section 4 and Section 5 of this paper appeared in [17].

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews the scientific motivation and challenges for remote under-ice oceanographic exploration, addressing these issues in the scientific contexts of geology and geophysics, biology, sea ice and climate, ice shelves, and seafloor mapping. Section 3 briefly reviews several approaches to vehicle navigation under ice. Section 4 reviews previously reported vehicle systems designed for use under fixed ice—landfast sea ice or ice shelves. Section 5 reviews previously reported vehicle systems designed for use under moving sea ice. Section 6 summarizes and concludes.

2. Scientific Motivation and Challenges for Remote Under-Ice Oceanographic Exploration

This section reviews the scientific motivation and challenges for remote under-ice oceanographic exploration, addressing these issues in the following scientific contexts; Ice Shelves (Section 2.1), Sea Ice and Ocean (Section 2.2), Biology (Section 2.3), Seafloor Mapping (Section 2.4), and Geology and Geophysics (Section 2.5).

2.1. Ice Shelves

A part of the world where climate changes are the largest and the most iconic is the poles, where the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets meet continental shelf seas. In the Arctic, atmospheric warming and other processes are leading to a shrinking ice sheet, increased subglacial runoff and the associated amplified interaction with the ocean [18], and weakening of the ice sheet buttressing glacial margins [19,20], with important implication to global sea level [21]. In the Antarctic, both atmospheric (Antarctic Peninsula) and ocean-driven melting (West Antarctica) of the ice shelves conspire to accelerate the flow of land ice into the ocean [16], thereby contributing significantly to sea level rise [22], and freshening continental shelf seas and the Southern Ocean [23,24]. In addition to sea level concerns, ice sheet–ocean interactions in Antarctica are key to the formation of dense waters that fill to global oceans abyss [25], and the melt-driven upwelling arising from the freshening and associated buoyancy gain is also thought to provide crucial nutrients for primary production in Southern continental shelf seas [26,27], with consequential contribution to the global biological carbon pump [28].

Around most of Greenland, the interaction between the ice and the ocean happens along a one to tens of kilometers wide, hundreds of meters high vertical ice face that flows into a fjord setting. Around most of Antarctica, the interaction mostly arises under an ice shelf, the floating extension of grounded glacial ice, within an ocean cavity covering tens to hundreds of kilometers in the horizontal and hundreds of meters in the vertical. These scales align rather well with present autonomous underwater vehicle capabilities, and remarkable progress in our understanding has been achieved thanks to few but precious forays into these treacherous environments.

The deployment of Autosub2 under the Fimbul ice shelf in East Antarctica showed a complex, irregular ice base geometry [29]. A few years later, the extensive observations under Pine Island Glacier ice shelf in West Antarctica revealed the importance of seabed bathymetry in shaping the access of the warmest deepest waters to the most sensitive glacier grounding line [30], the glacial retreat history [31], the glacial melt sensitivity to oceanic variability [32], and the broader connections with climate variability [33,34]. The same missions also imaged important features on the seabed [35,36] and the ice base [37,38]. The latter, instead of the irregular features discerned earlier, is organized in a series of kilometer-wide, hundred meter high channels that drive the circulation and heat exchange at the ice–ocean interface, and are also carved by melt [39,40]. In turn, the flanks of such channels are not smooth, but instead harbor a terraced geometry that is also carved by and modulates melting [37], hinting at a tightly coupled ice–ocean system.

These advances led to new AUV operations, first repeating surveys under Pine Island Glacier ice shelf with modified sensor payload [41] and more recently exploring other settings, expanding the diversity of vehicle types and capabilities (see Section 4).

2.2. Sea Ice and Ocean

The decline of Arctic sea ice is one of the most conspicuous examples of climate change; September ice extent is now ~35% lower than four decades ago. In contrast, Antarctic sea ice extent has increased modestly over the same period, only to drop to record lows in 2016 from which it has yet to fully recover [42]. Neither of these trends are adequately captured by models [43,44]. In the Arctic, sea ice has also thinned dramatically, with the loss of almost all ice more than a few years old [42]. Thinning was first established between the late 1950s–1979 and the 1990s from extensive upward-looking sonar from American and British submarines [45,46], a trend that has continued to be observed by satellites [47,48]. Under-ice vehicles have the advantage of an unobstructed view of the ice underside. Equipped with multibeam sonar, they can provide a detailed view of ice morphology and understanding of the mechanical thickening driven by ice dynamics that is otherwise very challenging to measure, particularly for thicker, ridged ice [49,50]. Because only a small fraction of sea ice rises above sea level, and is usually concealed under a layer of snow, sonar measurements of the ice draft provide the most reliable estimate of sea ice thickness. Such observations can help validate satellite altimeter estimates of sea ice thickness [51], particularly at the high spatial resolutions possible with the recently launched ICESAT-2 [52].

Sea ice change is closely coupled with changes in the upper ocean. The Arctic maintains a perennial ice cover in part because it is insulated from the heat of warmer waters at depth by cold, fresher surface waters. This stratification results from a complex series of pathways and physical mechanisms, including inflows of both warm and cold Pacific-sourced waters at shallow depths, a warm inflow of Atlantic Water at intermediate depths, riverine input, sea ice melt and growth, and solar heating, that are not well observed or understood (see, e.g., in [53]). In the Eastern Arctic, increasing inflow and temperature of Atlantic Water has been observed, contributing to reduced ice growth in winter [54]. In the Western Arctic, the increasingly seasonal ice cover has been accompanied by increased inflow of warm Pacific water through the Bering Strait, thought to contribute to reduced summer ice extent and potentially winter ice growth [55], increased solar heating at shallow depths that retards autumn ice growth, and may also act as a source of heat to limit winter ice growth [56,57]. While strong stratification presently limits the role of the latter, this may increase alongside the observed increase in the role of waves and storms [58] and a thinner, more mobile ice cover.

Of particular interest to vehicle operations beneath the Arctic ice cover is the development of the “Beaufort lens”, a sound duct that forms as cooler Pacific Winter Water is sandwiched between warm Pacific Summer Water at depths of 50–100 m and warm, salty layer of Atlantic sourced waters at depths below 150–200 m. Regionally and seasonally variable, this sound duct can enable acoustic communication over distances up to 400 km [59].

In the Antarctic, a thin, seasonal ice cover is maintained in part by the weak upper ocean stratification that facilitates stronger ice–ocean interactions and release of deeper ocean heat than in the Arctic. This strong coupling between the ice and ocean has been invoked as contributing both long-term expansion of the winter ice cover [60], and the dramatic recent retreat [61]. The open northern boundary of the ice pack is exposed to the storms and swell of the Southern Ocean. Here, atmosphere–wave–ice–ocean interactions drive ice production and break-up, ice edge retreat and advance, and a variety of mesoscale phenomena [62]. Along the Antarctic coast, similar processes play important roles in polynyas, where strong winds drive high rates of ice production and export from the coast plays an important role in global water mass transformation. There have been very few direct observations of these processes due to the challenges of operating in these remote and highly dynamic environments (see, e.g., in [63]).

Moorings, ice-tethered platforms, and under-ice profiling floats have provided critical information on these ongoing changes and inter- and intra-seasonal variability, but require significant logistical support to deploy. Moreover, they cannot adequately observe mesoscale phenomena. Larger-scale operations with on-site scientists and technicians are limited by the expense and logistical challenges of operating in this environment. This is particularly true in winter, where large, multidisciplinary expeditions might occur decades apart in some regions (see, e.g., in [63,64]). Under-ice vehicles offer an attractive means to observe ice–ocean interactions in these challenging environments where capturing processes that vary dramatically across small to medium spatial scales are needed, or where traditional methods are exceedingly difficult to perform (see, e.g., in [63,65]). As capabilities advance, particularly for long-term or long-range presence, autonomous under-ice vehicles will play an increasing role in sustained observations of the ice and ocean in both the Arctic and Antarctic [66,67].

2.3. Biology

Under-ice ocean worlds belong to the least studied ecosystems on Earth. Therefore, one priority for under-ice robots is the discovery of a highly endemic diversity of life in the Arctic and Antarctic [68]. A key issue is the accessibility of the under-ice life which uses sea ice flows as a substrate, hideout, feeding, and breeding grounds. A number of species are directly connected to life in the ice, including, for example, the colonial sea ice algae Melosira which grows into kelp-like forests [11]. ROVs have been used to assess the 3D structure of the under-ice habitat, as well as light transmission, primary productivity, distribution of algae [69], and also the gelatinous life inhabiting the highly stratified water layer under the ice, which is less dense due to the input of ice melt water [70]. Under-ice ROVs or AUVs allow noninvasive studies of the productive layers under the ice and in the upper ice-covered ocean, which can help in quantifying carbon and nutrient budgets, as well as revealing the food webs, diversity, and biological interactions of polar life. Only a few studies have been extended to the deep water and polar ocean seafloor. Early investigations by tethered ROV video surveys of the highly productive Antarctic seafloor assessed composition of benthic communities and the impact of and recovery from iceberg grounding [71]. Modern working class ROVs like Victor 6000, Quest, and Kiel 6000 enable experimental studies on factors shaping polar biodiversity (see, e.g., in [72]) in seasonally ice-covered waters, yet they cannot be deployed in full ice. Recent studies of the Arctic ridges, focusing on vents (see, e.g., in [73]) and other prominent habitats associated with the ridges like sponge reefs, cold water corals, and sea mounts, have detected previously unknown, diverse seafloor communities adapted to tap into chemical energy provided from seeping and degassing of hydrogen, sulfur, or hydrocarbons, or from hydrothermalism (see, e.g., in [12,74,75]). Key questions remain as to the effect of climate change, sea ice retreat, glacial melt, and pollution or other forms of human impact on these vulnerable regions of Earth. Some areas that cannot be accessed by ship, like the seafloor under glaciers or thick Antarctic fast ice need first time studies by long range AUVs. ROVs and AUVs have barely been used in polar winter, and key questions remain as to the role and fate of polar life in absolute darkness and coldness of the polar night. The North Pole drift expedition MOSAIC will, for the first time, produce year round under-ice imaging in 3D [76,77]. Accessing polar regions year-round at all depths remains a key task in global ocean observation, management, and protection of ocean life, but needs substantial innovation in reach, navigation, data transmission, and endurance of under-ice robots, especially those equipped with energy-hungry sonars, cameras, and biosensors.

2.4. Seafloor Mapping

Seafloor mapping in ice-covered regions offers the same critical geospatial contextual information that it provides in open waters, including the data needed for safe navigation (of both surface and submerged vessels), for defining and understanding benthic habitats, for establishing the routes and dissipation of the deep-sea currents that globally distribute heat, for understanding geologic and tectonic processes (see Section 2.5), for determining the risk of natural hazards (submarine landslides and gas seeps), for revealing a treasure trove of maritime heritage, for predicting tsunami inundation and storm surge run-off, and for exploration and discovery of the 85% of the seafloor that is yet to be mapped. While seafloor and water column mapping from ice breakers is feasible, it is an extremely slow process when done in ice-drift modus, or greatly hampered by the noise generated by ice-breaking. Thus, mapping efforts in ice-covered regions, like those carried out to establish limits of the continental shelf under Article 76 of the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea [78] are remarkably time-consuming and tend to be conducted as sparsely separated lines rather than the typical overlapping, complete coverage of standard multibeam sonar surveys. The inability to obtain complete overlapping mapping coverage in ice-covered regions greatly reduces the value of these data, as it is often the ability to see the complete picture of the geologic or morphologic context that provides critical insights into seafloor and oceanographic processes.

There are several applications that are particularly critical in ice-covered waters. First among these is the determination of the bathymetry under marine terminating glaciers with ice shelves. Mass loss from ice sheets in both Greenland and Antarctica has increased dramatically over the past few decades and is a critical contributor to global sea level rise. A key component of the mass loss process, yet one whose quantification is still uncertain, is the contribution from the retreat of marine terminating glaciers forced by oceanic heat transport [79]. The ability of relatively warm waters to interact with marine terminating glaciers is often dependent on the presence or absence of bathymetric sills located under floating ice tongues [33,80], and thus the ability to map under ice-tongues is critical to understanding the fate of terminating glaciers. Additionally, the ability to map the location of grounding lines under ice shelves can provide critical insight into the history and dynamics of the ice sheets [30,31,35,81]. Finally, the history of Arctic glaciation, a fundamental driver of global climate, is recorded on the seafloor (i.e., the recent demonstration that a 1km thick ice sheet covered the central Arctic during the penultimate glaciation [82]) and in the subsurface sediments of the ice-covered regions of the Arctic. Future plans to sample these sediments through scientific drilling will depend on the ability to obtain detailed maps of potential drill sites. Last but not least, high-resolution maps are essential for ecosystem research and as basis for assessing the ecological status of seafloor habitats, and for establishing marine protected areas. New technologies are available to combine mapping and video surveys as an efficient way of creating ecological knowledge of baselines and of disturbances [83,84].

2.5. Geology and Geophysics

While ice-tethered profilers have begun to allow routine access to processes at the ice–ocean interface over the past decade or more (see, e.g., in [85]), polar scientists have continued to lack cutting edge capabilities with which to investigate the deep seafloor of both the Arctic and the Antarctic. This has proven particularly frustrating in the context of marine geoscientists interested in the evolution of ocean basins, from three perspectives: (a) in terms of understanding the evolution of the Amerasian Basin in the Arctic, for which numerous, often conflicting, models have been proposed, and (b,c) because the Bransfield Strait in the Antarctic and the Gakkel Ridge in the Arctic represent type localities where geoscientists seek to investigate key processes related to incipient continental rifting and ultra-slow spreading mid ocean ridges, respectively.

For the Amerasian Basin, resolving which of several competing basin evolution models [86,87,88,89,90] is correct remains critical to our understanding of the tectonics of this basin, and therefore its impact on global paleoclimate through the evolution of inter-ocean connections. The paucity of published geophysical data and lack of rock samples from within the basin have made interpretations of the kinematic history of the Amerasia Basin difficult to constrain. The U.S. Extended Continental Shelf Program dredged rock samples from the Chukchi Borderland, Northwind Ridge, and Alpha Ridge using the US Coast Guard Cutter (USCGC) Healy Those samples have brought pre-existing models into question [91], but like all dredged samples, raise the issue of how representative they are of in situ bedrock. Only in situ sampling by a well-positioned underwater vehicle can be guaranteed to provide in situ context and precise location of collected samples.

Studying incipient continental rifting is critical to understanding the evolution of the US Atlantic continental margin. From this perspective, the Bransfield Strait, immediately north and west of the Antarctic Peninsula, rivals the Red Sea (which has even more complex geopolitical barriers to access) as an ideal natural laboratory in which to study such processes—from the first rifting of continental crust through to the opening of ocean basins [92,93]. From shipboard remote-sensing geophysics (seismics, magnetics, and multibeam) data, it is known that the Bransfield Strait rift is comprised of a series of extensional basins that are infilled with detritus from Antarctica. These basins are separated from one another by prominent volcanic constructions that define the rift axis and at least some of which host hydrothermal activity [94,95,96]. This research has been rather thwarted for more than a decade, however, because no detailed examination of the seafloor geology, including the hydrothermal sites hosted there, have been able to be attempted by ROV.

The Gakkel Ridge, which extends across the entire Arctic Basin from the Norwegian-Greenland Sea to the Siberian Margin represents Earth’s slowest spreading and most geologically diverse mid-ocean ridge, exposing significant outcrops of ultramafic as well as mafic lithologies [15,97] and hosting evidence for geologically recent, and explosive volcanism [12,74,75]. While much has been hypothesized about these processes from remote sensing (including systems mounted on US Navy submarines deployed beneath the ice cap), this ridge system—including the numerous hydrothermal systems that it is known to host [2]—awaits direct intervention by a suitable deep-diving research submersible. This interest has become even more acute in the past decade with the recognition that multiple other planetary bodies in the outer solar system also host saltwater oceans with rocky seafloors beneath their ice shell exteriors [98]. Geothermal systems that can sustain chemosynthetic ecosystems, independent of sunlight, beneath Earth’s ice-covered oceans thus become a compelling analog site for study in the search for life beyond Earth.

2.6. Vehicle Capability Needs for Under-Ice Science Missions

The vehicle capability needs for future oceanographic science missions under sea ice and ice shelves naturally depends on the nature of the particular science missions as well as the physical geography of the sea. Although a comprehensive study of vehicle capability needs is beyond the scope of this paper, we note some preliminary observations.

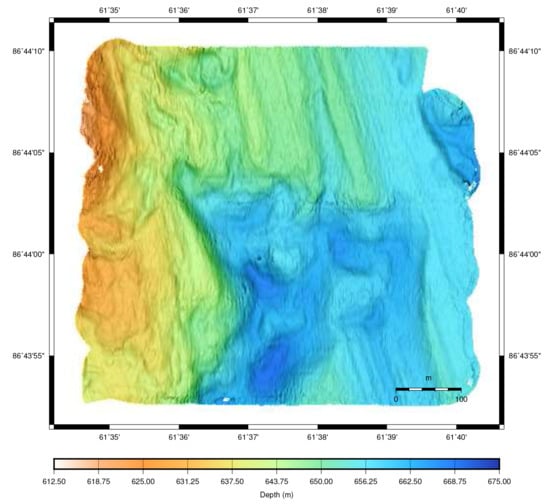

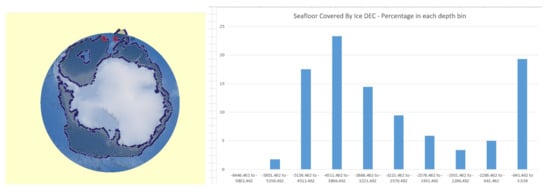

Most ship-based oceanographic operations in the Antarctic occur from November to April. Figure 1 shows, on the left, the Antarctic ice cover in December 2019 and, on the right, the corresponding percentage this ice-covered sea floor for each of 10 depth bins. We note that 40% of the December 2019 ice-covered sea floor has depth between about 3800 m and 5200 m, and that a vehicle with a depth capability of 5200 m could reach 98% of the this sea floor. In the Arctic Ocean, the permanently sea ice covered area according to the September sea ice minimum is >1000 m deep, and a vehicle reaching 5000 m would be needed to cover most seafloor area including the North Pole.

Figure 1.

Antarctic seafloor covered by ice in December (denoted “DEC” in the figure) 2019 (left figure). Percentage distribution of this ice-covered seafloor in 10 depth bins (right figure).

In terms of horizontal scales, ice shelves can extend from a few kilometers to 1000 km at the most (Filchner–Ronne and Ross), from the calving front to the grounding line. Considering the distance covered by shelf ice, a vehicle with a 400 km range (including the return path) could reach a significant number of targets in a single dive. However, considering the vast area of shelf ice in Antarctica of 1.5 million square kilometers, and that Filchner–Ronne, Ross, and Amery make up most of the area, much longer range capacities are needed for under ice research with at least 1000 km range. Furthermore, a key feature for the future will be the persistent or resident nature of the AUV observations as the need to cover seasonal and interannual variability is extremely important for the coupled ice–ocean interaction physics.

6. Conclusions

The 12% of the world’s oceans that is covered by fixed or moving ice remains largely inaccessible to ocean science. Over the last three decades, researchers have developed and deployed multiple new classes of underwater robotic vehicles and navigation methods specifically to provide scientific access beneath ice shelves, landfast ice, and free-floating ice. However, fundamental obstacles remain that severely limit under-ice oceanographic vehicle operations in ice-covered environments including vehicle launch, recovery, and navigation. Successful ship-based under-ice operations are subject to favorable weather and ice conditions, whereas landfast and through-ice vehicle deployments require specialized ice drilling or melting equipment, which also significantly constrain vehicle size, shape and endurance. Navigation beneath both moving and stationary ice remains challenging, both at depth and near the surface.

Nearly two decades ago, Edmonds et al. [2] discovered abundant hydrothermal venting along the 1100 km Gakkel Ridge in the Arctic Ocean, clearly indicating the existence of 9–12 discrete active hydrothermal vent sites, but specific active vent sites on the Gakkel Ridge have yet to be explored. Similarly, exploration of ice shelf cavities only started a decade ago, and only half a dozen cavities have been partially or comprehensively observed to date, in general for a limited amount of time (hours to days). Under sea ice, passive drifting platforms and manned icebreakers and ice stations have been used for decades, but observations remain sparse compared to the open ocean, particularly in winter. UUVs have only just begun to be routinely exploited, with most covering only limited ranges and/or durations, and with efforts for sustained observations or long-range missions only just emerging. The potential for first-order scientific discoveries at high latitudes, under ice, remains high, but new and improved approaches to the design and navigation of underwater vehicles will be needed to achieve this.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.D.L.B. and L.L.W; writing–original draft preparation, all Authors; writing–review and editing, all Authors. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Barker and Whitcomb gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Science Foundation under Award 1319667 and 1909182, and support of the first author under a Graduate Fellowship from the Johns Hopkins Department of Mechanical Engineering. Jakuba, Bowen, and German gratefully acknowledge the support of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration under Planetary Science and Technology through Analog Research (PSTAR) award NNX16AL04G. Maksym was supported by National Science Foundation Award CMMI-1839063. Dutrieux was supported by his Center for Climate and Life Fellowship from the Earth Institute of Columbia University. Boetius acknowledges funding from the Helmholtz Association for the FRAM infrastructure, and from her ERC Adv. Grant ABYSS (294757). Mayer’s work is supported by NOAA Grant NA15NOS4000200.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript.

| ACTV | Autonomous Conductivity Temperature Vehicle |

| AMTV | Autonomous Microconductivity Temperature Vehicle |

| ARCS | Autonomous Remotely Controlled Submersible |

| AUV | Autonomous Underwater Vehicle |

| BRUIE | Buoyant Rover for Under-Ice Exploration |

| CTD | Conductivity Temperature Depth |

| DR | Dead Reckoning |

| DVL | Doppler Velocity Log |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| FATTI | Fluorometer and Acoustic Transducer Towable Instrument |

| FOG | Fiber-optic Gyroscope |

| GPS | Global Positioning System |

| HOV | Human Occupied Vehicle |

| HROV | Hybrid Remotely Operated Vehicle |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| INS | Inertial Navigation System |

| ISE | International Submarine Engineering |

| LBL | Long Baseline |

| MBARI | Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute |

| MEMS | Micro-electro-mechanical system |

| MIZ | Marginal Ice Zone |

| MSLED | Micro Subglacial Exploration Device |

| NUI | Nereid Under-Ice |

| OWTT | One Way Travel Time |

| PAUL | Polar Autonomous Underwater Laboratory |

| PIG | Pine Island Glacier |

| REMUS | Remote Environmental Monitoring UnitS |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

| RIS | Ross Ice Shelf |

| RLG | Ring-laser Gyroscope |

| ROV | Remotely Operated Vehicle |

| SBL | Short Baseline |

| SCINI | Submersible Capable of under Ice Navigation and Imaging |

| SIR | Sub-Ice ROV |

| SLAM | Simultaneous Localization and Mapping |

| SLW | Subglacial Lake Whillans |

| SODA | Stratified Ocean Dynamics of the Arctic |

| TRN | Terrain Relative Navigation |

| TROV | Telepresence-Controlled Remotely Operated Vehicle |

| TWTT | Two Way Travel Time |

| UARS | Unmanned Arctic Research Submersible System |

| USBL | Ultra-Short Baseline |

| UUV | Uninhabited Underwater Vehicle |

| WHOI | Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution |

| MOR | Mid-Ocean Ridge |

References

- Weeks, W. On Sea Ice; University of Alaska Press: Fairbanks, AK, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Edmonds, H.N.; Michael, P.J.; Baker, E.T.; Connelly, D.P.; Snow, J.E.; Langmuir, C.H.; Dick, H.J.B.; Mühe, R.; German, C.R.; Graham, D.W. Discovery of abundant hydrothermal venting on the ultra-slow spreading Gakkel Ridge, Arctic Ocean. Nature 2003, 421, 252–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smethie, W.M.; Chayes, D.; Perry, R.; Schlosser, P. A lightweight vertical rosette for deployment in ice-covered waters. Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2011, 58, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nansen, F. Farthest North: Being the Record of a Voyage of Exploration of the Ship “Fram” 1893–1896 and of a Fifteen Months’ Sleigh Journey by Dr. Nansen and Lieut. Johansen (Complete); Macmillan and Company: London, UK, 1904; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Bourke, R.H.; Garrett, R.P. Sea ice thickness distribution in the Arctic Ocean. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 1987, 13, 259–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, M.; Grantz, A.; Kristoffersen, Y.; Macnab, R. Physiographic provinces of the Arctic Ocean seafloor. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 2003, 115, 1443–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, L.; Jakobsson, M.; Allen, G.; Dorschel, B.; Falconer, R.; Ferrini, V.; Lamarche, G.; Snaith, H.; Weatherall, P. The Nippon Foundation—GEBCO seabed 2030 project: The quest to see the world’s oceans completely mapped by 2030. Geosciences 2018, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, U.; Wulff, T. Correcting Navigation Data of shallow-diving AUV in Arctic. Sea Technol. 2015, 56, 27–30. [Google Scholar]

- Wulff, T.; Bauerfeind, E.; von Appen, W.J. Physical and ecological processes at a moving ice edge in the Fram Strait as observed with an AUV. Deep. Sea Res. Part I Oceanogr. Res. Pap. 2016, 115, 253–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jørgensen, L.; Archambault, P.; Armstrong, C.; Dolgov, A.; Edinger, E.; Gaston, T.; Hildebrand, J.; Piepenburg, D.; Smith, W.; Quillfeldt, C.; et al. Arctic marine biodiversity. In The First Global Integrated Marine Assessment, World Ocean Assessment I; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016; p. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Boetius, A.; Albrecht, S.; Bakker, K.; Bienhold, C.; Felden, J.; Fernández-Méndez, M.; Hendricks, S.; Katlein, C.; Lalande, C.; Krumpen, T.; et al. RV Polarstern ARK27-3-Shipboard Science Party. Export of Algal Biomass from the Melting Arctic Sea Ice. Science 2013, 339, 1430–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, M.; Kurras, G.; Tolstoy, M.; Bohnenstiehl, D.; Coakley, B.; Cochran, J. Evidence of recent volcanic activity on the ultraslow-spreading Gakkel Ridge. Nature 2001, 409, 808–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, R.; Goodwillie, A. The Physiography of the Southwest Indian Ridge. Mar. Geophys. Res. 1997, 19, 451–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grindlay, N.R.; Madsen, J.A.; Rommevaux-Jestin, C.; Sclater, J. A different pattern of ridge segmentation and mantle Bouguer gravity anomalies along the ultra-slow spreading Southwest Indian Ridge (15 30’E to 25E). Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 1998, 161, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dick, H.J.; Lin, J.; Schouten, H. An ultraslow-spreading class of ocean ridge. Nature 2003, 426, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scambos, T.A.; Bell, R.E.; Alley, R.B.; Anandakrishnan, S.; Bromwich, D.H.; Brunt, K.; Christianson, K.; Creyts, T.; Das, S.B.; DeConto, R.; et al. How much, how fast? A science review and outlook for research on the instability of Antarctica’s Thwaites Glacier in the 21st century. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2017, 153, 16–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, L.D.L.; Whitcomb, L.L. A preliminary survey of underwater robotic vehicle design and navigation for under-ice operations. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Daejeon, Korea, 9–14 October 2016; pp. 2028–2035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straneo, F.; Hamilton, G.; Stearns, L.; Sutherland, D. Connecting the Greenland Ice Sheet and the Ocean: A Case Study of Helheim Glacier and Sermilik Fjord. Oceanography 2016, 29, 34–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joughin, I.; Shean, D.E.; Smith, B.E.; Floricioiu, D. A decade of variability on Jakobshavn Isbræ: Ocean temperatures pace speed through influence on mélange rigidity. Cryosphere 2020, 14, 211–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khazendar, A.; Fenty, I.G.; Carroll, D.; Gardner, A.; Lee, C.M.; Fukumori, I.; Wang, O.; Zhang, H.; Seroussi, H.; Moller, D.; et al. Interruption of two decades of Jakobshavn Isbrae acceleration and thinning as regional ocean cools. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 277–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IMBIE Team. Mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2018. Nature 2020, 579, 233–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shepherd, A.; Ivins, E.; Rignot, E.; Smith, B.; van den Broeke, M.; Velicogna, I.; Whitehouse, P.; Briggs, K.; Joughin, I.; Krinner, G.; et al. Mass balance of the Antarctic Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2017. Nature 2018, 558, 219–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.S.; Giulivi, C.F. Large Multidecadal Salinity Trends near the Pacific-Antarctic Continental Margin. J. Clim. 2010, 23, 4508–4524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rye, C.D.; Naveira Garabato, A.C.; Holland, P.R.; Meredith, M.P.; George Nurser, a.J.; Hughes, C.W.; Coward, A.C.; Webb, D.J. Rapid sea-level rise along the Antarctic margins in response to increased glacial discharge. Nat. Geosci. 2014, 7, 732–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, K.W.; Østerhus, S.; Makinson, K.; Gammelsrød, T.; Fahrbach, E. Ice-ocean processes over the continental shelf of the southern Weddell Sea, Antarctica: A review. Rev. Geophys. 2009, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alderkamp, A.C.; van Dijken, G.L.; Lowry, K.E.; Connelly, T.L.; Lagerström, M.; Sherrell, R.M.; Haskins, C.; Rogalsky, E.; Schofield, O.; Stammerjohn, S.E.; et al. Fe availability drives phytoplankton photosynthesis rates during spring bloom in the Amundsen Sea Polynya, Antarctica. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2015, 3, 000043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherrell, R.; Lagerström, M.; Forsch, K.; Stammerjohn, S.; Yager, P. Dynamics of dissolved iron and other bioactive trace metals (Mn, Ni, Cu, Zn) in the Amundsen Sea Polynya, Antarctica. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2015, 3, 000071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrigo, K.R.; van Dijken, G.; Long, M. Coastal Southern Ocean: A strong anthropogenic CO2 sink. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholls, K.W.; Abrahamsen, E.P.; Buck, J.J.H.; Dodd, P.A.; Goldblatt, C.; Griffiths, G.; Heywood, K.J.; Hughes, N.E.; Kaletzky, A.; Lane-Serff, G.F.; et al. Measurements beneath an Antarctic ice shelf using an autonomous underwater vehicle. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, 2–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkins, A.; Dutrieux, P.; Jacobs, S.S.; McPhail, S.D.; Perrett, J.R.; Webb, A.T.; White, D. Observations beneath Pine Island Glacier in West Antarctica and implications for its retreat. Nat. Geosci. 2010, 3, 468–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Andersen, T.J.; Shortt, M.; Gaffney, A.M.; Truffer, M.; Stanton, T.P.; Bindschadler, R.; Dutrieux, P.; Jenkins, A.; Hillenbrand, C.D.D.; et al. Sub-ice-shelf sediments record history of twentieth-century retreat of Pine Island Glacier. Nature 2016, 541, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, S.S.; Jenkins, A.; Giulivi, C.F.; Dutrieux, P. Stronger ocean circulation and increased melting under Pine Island Glacier ice shelf. Nat. Geosci. 2011, 4, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrieux, P.; De Rydt, J.; Jenkins, A.; Holland, P.R.; Ha, H.K.; Lee, S.H.; Steig, E.J.; Ding, Q.; Abrahamsen, E.P.; Schroder, M. Strong Sensitivity of Pine Island Ice-Shelf Melting to Climatic Variability. Science 2014, 343, 174–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, P.R.; Bracegirdle, T.J.; Dutrieux, P.; Jenkins, A.; Steig, E.J. West Antarctic ice loss influenced by internal climate variability and anthropogenic forcing. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graham, A.G.C.; Dutrieux, P.; Vaughan, D.G.; Nitsche, F.O.; Gyllencreutz, R.; Greenwood, S.L.; Larter, R.D.; Jenkins, A. Seabed corrugations beneath an Antarctic ice shelf revealed by autonomous underwater vehicle survey: Origin and implications for the history of Pine Island Glacier. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2013, 118, 1356–1366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.; Bingham, R.G.; Graham, A.G.C.; Spagnolo, M.; Dutrieux, P.; Vaughan, D.G.; Jenkins, A.; Nitsche, F.O. High-resolution sub-ice-shelf seafloor records of twentieth century ungrounding and retreat of Pine Island Glacier, West Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Earth Surf. 2017, 122, 1698–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrieux, P.; Stewart, C.; Jenkins, A.; Nicholls, K.W.; Corr, H.F.J.; Rignot, E.; Steffen, K. Basal terraces on melting ice shelves. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 5506–5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrieux, P.; Jenkins, A.; Nicholls, K.W. Ice-shelf basal morphology from an upward-looking multibeam system deployed from an autonomous underwater vehicle. Geol. Soc. Lond. Mem. 2016, 46, 219–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutrieux, P.; Vaughan, D.G.; Corr, H.F.J.; Jenkins, A.; Holland, P.R.; Joughin, I.; Fleming, A.H. Pine Island glacier ice shelf melt distributed at kilometre scales. Cryosphere 2013, 7, 1543–1555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shean, D.E.; Joughin, I.R.; Dutrieux, P.; Smith, B.E.; Berthier, E. Ice shelf basal melt rates from a high-resolution digital elevation model (DEM) record for Pine Island Glacier, Antarctica. Cryosphere 2019, 13, 2633–2656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, S.; Jenkins, A.; Dutrieux, P.; Forryan, A.; Naveira Garabato, A.C.; Firing, Y. Ocean mixing beneath Pine Island Glacier ice shelf, West Antarctica. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 8496–8510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maksym, T. Arctic and Antarctic Sea Ice Change: Contrasts, Commonalities, and Causes. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 2019, 11, 187–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stroeve, J.C.; Kattsov, V.; Barrett, A.; Serreze, M.; Pavlova, T.; Holland, M.; Meier, W.N. Trends in Arctic sea ice extent from CMIP5, CMIP3 and observations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobbs, W.R.; Massom, R.; Stammerjohn, S.; Reid, P.; Williams, G.; Meier, W. A review of recent changes in Southern Ocean sea ice, their drivers and forcings. Glob. Planet. Chang. 2016, 143, 228–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothrock, D.A.; Yu, Y.; Maykut, G.A. Thinning of the Arctic sea ice cover. Geophys. Res. Lett. 1999, 26, 3469–3472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhams, P.; Davis, N.R. Further evidence of ice thinning in the Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2000, 27, 3973–3975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, R.; Rothrock, D.A. Decline in Arctic sea ice thickness from submarine and ICESat records: 1958–2008. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2009, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, R.; Cunningham, G.F. Variability of Arctic sea ice thickness and volume from CryoSat-2. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2015, 373, 20140157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wadhams, P.; Wilkinson, J.P.; McPhail, S.D. A new view of the underside of Arctic sea ice. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2006, 33, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, G.; Maksym, T.; Wilkinson, J.; Kunz, C.; Murphy, C.; Kimball, P.; Singh, H. Thick and deformed Antarctic sea ice mapped with autonomous underwater vehicles. Nat. Geosci. 2015, 8, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, M.J.; Maksym, T.; Weissling, B.; Singh, H. Estimating early-winter Antarctic sea ice thickness from deformed ice morphology. Cryosphere 2019, 13, 2915–2934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwok, R.; Markus, T.; Kurtz, N.T.; Petty, A.A.; Neumann, T.A.; Farrell, S.L.; Cunningham, G.F.; Hancock, D.W.; Ivanoff, A.; Wimert, J.T. Surface Height and Sea Ice Freeboard of the Arctic Ocean From ICESat-2: Characteristics and Early Results. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2019, 124, 6942–6959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmack, E.; Polyakov, I.; Padman, L.; Fer, I.; Hunke, E.; Hutchings, J.; Jackson, J.; Kelley, D.; Kwok, R.; Layton, C.; et al. Toward Quantifying the Increasing Role of Oceanic Heat in Sea Ice Loss in the New Arctic. Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 2015, 96, 2079–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polyakov, I.V.; Pnyushkov, A.V.; Alkire, M.B.; Ashik, I.M.; Baumann, T.M.; Carmack, E.C.; Goszczko, I.; Guthrie, J.; Ivanov, V.V.; Kanzow, T.; et al. Greater role for Atlantic inflows on sea ice loss in the Eurasian Basin of the Arctic Ocean. Science 2017, 356, 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodgate, R.A.; Weingartner, T.; Lindsay, R. The 2007 Bering Strait oceanic heat flux and anomalous Arctic sea ice retreat. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2010, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, J.M.; Williams, W.J.; Carmack, E.C. Winter sea ice melt in the Canada Basin, Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2012, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timmermans, M.L.; Toole, J.; Krishfield, R. Warming of the interior Arctic Ocean linked to sea ice losses at the basin margins. Sci. Adv. 2018, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thomson, J.; Rogers, W.E. Swell and sea in the emerging Arctic Ocean. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2014, 41, 3136–3140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitag, L.; Ball, K.; Partan, J.; Koski, P.; Singh, S. Long range acoustic communications and navigation in the Arctic. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2015—MTS/IEEE Washington, Washington, DC, USA, 19–22 October 2015; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Lecomte, O.; Goosse, H.; Fichefet, T.; de Lavergne, C.; Barthélemy, A.; Zunz, V. Vertical ocean heat redistribution sustaining sea ice concentration trends in the Ross Sea. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meehl, G.A.; Arblaster, J.M.; Chung, C.T.Y.; Holland, M.M.; DuVivier, A.; Thompson, L.; Yang, D.; Bitz, C.M. Sustained ocean changes contributed to sudden Antarctic sea ice retreat in late 2016. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squire, V.A. The marginal ice zone. In Physics of Ice-Covered Seas; Lepparanta, M., Ed.; Helsinki University Printing House: Helsinki, Finland, 1998; Volume 1, pp. 281–446. [Google Scholar]

- Ackley, S.F.; Stammerjohn, S.; Maksym, T.; Smith, M.; Cassano, J.; Guest, P.; Tison, J.L.; Delille, B.; Loose, B.; Sedwick, P.; et al. Sea ice production and air-ice-ocean-biogeochemistry interactions in the Ross Sea during the PIPERS 2017 autumn field campaign. Ann. Glaciol. 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bronwyn, W. A drift in the Arctic. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2019, 9, 733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Thomson, J. An autonomous approach to observing the seasonal ice zone in the western Arctic Oceanography. Oceanography 2016, 30, 56–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, C.M.; Cole, S.; Doble, M.; Guthrie, J.D.; Mackinnon, J.; Morison, J.; Musgrave, R.; Peacock, T.; Rainville, L.; Stanton, T.; et al. Stratified Ocean Dynamics of the Arctic: Science and Experiment Plan; Technical Report APL-UW 1601; Applied Physics Laboratory, University of Washington: Seattle, WA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, L.; Heil, P.; Trebilco, R.; Katsumata, K.; Constable, A.; van Wijk, E.; Assmann, K.; Beja, J.; Bricher, P.; Coleman, R.; et al. Delivering Sustained, Coordinated, and Integrated Observations of the Southern Ocean for Global Impact. Front. Mar. Sci. 2019, 6, 433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raskoff, K.; Hopcroft, R.; Kosobokova, K.; Purcell, J.; Youngbluth, M. Jellies under ice: ROV observations from the Arctic 2005 hidden ocean expedition. Deep. Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2010, 57, 111–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katlein, C.; Schiller, M.; Belter, H.J.; Coppolaro, V.; Wenslandt, D.; Nicolaus, M. A New Remotely Operated Sensor Platform for Interdisciplinary Observations under Sea Ice. Front. Mar. Sci. 2017, 4, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- German, C.R.; Boetius, A.; Whitcomb, L.L.; Jakuba, M.; Bailey, J.; Judge, C.; McFarland, C.; Suman, S.; Elliott, S.; Katlein, C.; et al. First Scientific Dives of the Nereid Under Ice Hybrid ROV in the Arctic Ocean; AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2014; Volume 2014, abstract ID B23G–07; Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2014AGUFM.B23G..07G (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Gutt, J.; Piepenburg, D. Scale-dependent impact on diversity of Antarctic benthos caused by grounding of icebergs. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 2003, 253, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltwedel, T.; Hasemann, C.; Vedenin, A.; Bergmann, M.; Taylor, J.; Krauß, F. Bioturbation rates in the deep Fram Strait: Results from in situ experiments at the arctic LTER observatory HAUSGARTEN. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2019, 511, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahle, H.; Le Moine Bauer, S.; Baumberger, T.; Stokke, R.; Pedersen, R.B.; Thorseth, I.H.; Steen, I.H. Energy landscapes in hydrothermal chimneys shape distributions of primary producers. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sohn, R.A.; Willis, C.; Humphris, S.; Shank, T.M.; Singh, H.; Edmonds, H.N.; Kunz, C.; Hedman, U.; Helmke, E.; Jakuba, M.; et al. Explosive volcanism on the ultraslow-spreading Gakkel ridge, Arctic Ocean. Nature 2008, 453, 1236–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontbriand, C.W.; Soule, S.A.; Sohn, R.A.; Humphris, S.E.; Kunz, C.; Singh, H.; Nakamura, K.; Jakobsson, M.; Shank, T. Effusive and explosive volcanism on the ultraslow-spreading Gakkel Ridge, 85°E. Geochem. Geophys. Geosyst. 2012, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kintisch, E. Arctic researchers prepare to go with the floes. Science 2019, 365, 728–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommerfeld, A.; Rex, M.; Shupe, M.; Dethloff, K. The Multidisciplinary drifting Observatory for the Study of Arctic Climate (MOSAiC). In Proceedings of the EGU General Assembly Conference Abstracts, Vienna, Austria, 23–28 April 2017; p. 2115. Available online: https://ui.adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2017EGUGA..19.2115S (accessed on 30 June 2020).

- Mayer, L.A.; Armstrong, A.; Calder, B.; Gardner, J. Sea Floor Mapping in the Arctic: Support for a Potential US Extended Continental Shelf. Int. Hydrogr. Rev. 2010, 3, 14–23. [Google Scholar]

- Straneo, F.; Heimbach, P. North Atlantic warming and the retreat of Greenland’s outlet glaciers. Nature 2013, 504, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaffer, J.; Kanzow, T.; von Appen, W.J.; von Albedyll, L.; Arndt, J.E.; Roberts, D.H. Bathymetry constrains ocean heat supply to Greenland’s largest glacier tongue. Nat. Geosci. 2020, 13, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsson, M.; Hogan, K.A.; Mayer, L.A.; Mix, A.; Jennings, A.; Stoner, J.; Eriksson, B.; Jerram, K.; Mohammad, R.; Pearce, C.; et al. The Holocene retreat dynamics and stability of Petermann Glacier in northwest Greenland. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 2104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jakobsson, M.; Nilsson, J.; Anderson, L.; Backman, J.; Björk, G.; Cronin, T.M.; Kirchner, N.; Koshurnikov, A.; Mayer, L.; Noormets, R.; et al. Evidence for an ice shelf covering the central Arctic Ocean during the penultimate glaciation. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 10365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thorsnes, T.; Brunstad, H.; Lågstad, P.; Chand, S. Trawl marks, iceberg ploughmarks and possible whale-feeding marks, Barents Sea. Geol. Soc. Lond. Mem. 2016, 46, 293–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gausepohl, F.; Hennke, A.; Schoening, T.; Köser, K.; Greinert, J. Scars in the abyss: Reconstructing sequence, location and temporal change of the 78 plough tracks of the 1989 DISCOL deep-sea disturbance experiment in the Peru Basin. Biogeosciences 2020, 17, 1463–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toole, J.; Krishfield, R.; Proshutinsky, A.; Ashjian, C.; Doherty, K.; Frye, D.; Hammar, T.; Kemp, J.; Peters, D.; Timmermans, M.L.; et al. Ice-tethered profilers sample the upper Arctic Ocean. Eos. Trans. Am. Geophys. Union 2006, 87, 434–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brumley, K.; Mayer, L.A.; Miller, E.; Coakley, B. Dredged rock samples from the Alpha Ridge, Arctic Ocean: Implications for the tectonic history and origin of the Amerasian Basin. Eos. Trans. AGU 2008, 89, T43B-2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lawver, L.; Scotese, C. A review of tectonic models for the evolution of the Canada Basin. Geol. N. Am. 1990, 50, 593–618. [Google Scholar]

- Grantz, A.; Hart, P.E.; Childers, V.A. Chapter 50 Geology and tectonic development of the Amerasia and Canada Basins, Arctic Ocean. Geol. Soc. Lond. Mem. 2011, 35, 771–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Døssing, A.; Jackson, H.; Matzka, J.; Einarsson, I.; Rasmussen, T.; Olesen, A.; Brozena, J. On the origin of the Amerasia Basin and the High Arctic Large Igneous Province—Results of new aeromagnetic data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2013, 363, 219–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chernykh, A.; Glebovsky, V.; Zykov, M.; Korneva, M. New insights into tectonics and evolution of the Amerasia Basin. J. Geodyn. 2018, 119, 167–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukasa, S.; Andronikov, A.; Mayer, L.; Brumley, K. Submarine basalts from the Alpha/Mendeleev Ridge and Chukchi Borderland: Geochemistry of the first intraplate lavas recovered from the Arctic Ocean. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta Suppl. 2009, 73, A912. [Google Scholar]

- Ferran, C.G. The Bransfield rift and its active volcanism. In Geological Evolution of Antarctica; Thomson, M., Crame, J., Thomson, J., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991; pp. 505–509. [Google Scholar]

- Lawver, L.A.; Sloan, B.J.; Barker, D.H.; Ghidella, M.; Von Herzen, R.P.; Keller, R.A.; Klinkhammer, G.P.; Chin, C.S. Distributed, active extension in Bransfield Basin, Antarctic Peninsula: Evidence from multibeam bathymetry. GSA Today 1996, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Gràcia, E.; Canals, M.; Farràn, M.L.; Prieto, M.J.; Sorribas, J.; Team, G. Morphostructure and evolution of the central and eastern Bransfield basins (NW Antarctic Peninsula). Mar. Geophys. Res. 1996, 18, 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinkhammer, G.; Chin, C.; Keller, R.; Dählmann, A.; Sahling, H.; Sarthou, G.; Petersen, S.; Smith, F.; Wilson, C. Discovery of new hydrothermal vent sites in Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 2001, 193, 395–407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, D.H.; Christeson, G.L.; Austin Jr, J.A.; Dalziel, I.W. Backarc basin evolution and cordilleran orogenesis: Insights from new ocean-bottom seismograph refraction profiling in Bransfield Strait, Antarctica. Geology 2003, 31, 107–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michael, P.; Langmuir, C.; Dick, H.; Snow, J.; Goldstein, S.; Graham, D.; Lehnert, K.; Kurras, G.; Jokat, W.; Mühe, R.; et al. Magmatic and amagmatic seafloor generation at the ultraslow-spreading Gakkel ridge, Arctic Ocean. Nature 2003, 423, 956–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hendrix, A.R.; Hurford, T.A.; Barge, L.M.; Bland, M.T.; Bowman, J.S.; Brinckerhoff, W.; Buratti, B.J.; Cable, M.L.; Castillo-Rogez, J.; Collins, G.C.; et al. The NASA Roadmap to Ocean Worlds. Astrobiology 2019, 19, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsey, J.C.; Eustice, R.M.; Whitcomb, L.L. A survey of underwater vehicle navigation: Recent advances and new challenges. In Proceedings of the IFAC Conference of Manoeuvering and Control of Marine Craft, Lisbon, Portugal, 20–22 September 2006; Volume 88. [Google Scholar]

- Francois, R.E.; Nodland, W.E. Unmanned Arctic Research Submersible UARS System Development and Test Report; Technical Report APL-UW 7219; University of Washington, Applied Physics Laboratory: Seattle, WA, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Francois, R.E. High Resolution Observations of Under-Ice Morphology; Technical Report APL-UW 7712; University of Washington, Applied Physics Laboratory: Seattle, WA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Deffenbaugh, M.; Schmidt, H.; Bellingham, J.G. Acoustic Navigation for Arctic under-ice AUV missions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Victoria, BC, Canada, 18–21 October 1993; Volume 1, pp. 1204–1209. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, R.; Thomas, H.; Weber, D.; Psota, F. Performance of an AUV navigation system at Arctic latitudes. IEEE J. Ocean. Eng. 2005, 30, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thorleifson, J.; Davies, T.; Black, M.; Hopkin, D.; Verrall, R. The Theseus Autonomous Underwater Vehicle: A Canadian Success Story. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Halifax, NS, Canada, 6–9 October 1997; pp. 1001–1008. [Google Scholar]

- Kaminski, C.; Crees, T.; Ferguson, J.; Forrest, A.; Williams, J.; Hopkin, D.; Heard, G. 12 days under ice—An historic AUV deployment in the Canadian High Arctic. In Proceedings of the 2010 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles, Monterey, CA, USA, 1–3 September 2010; pp. 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crees, T.; Kaminski, C.; Ferguson, J.; Laframboise, J.M.; Forrest, A.; Williams, J.; MacNeil, E.; Hopkin, D.; Pederson, R. UNCLOS under ice survey—An historic AUV deployment in the Canadian high arctic. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2010 MTS/IEEE SEATTLE, Seattle, WA, USA, 20–23 September 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustice, R.M.; Whitcomb, L.L.; Singh, H.; Grund, M. Recent Advances in Synchronous-Clock One-Way-Travel-Time Acoustic Navigation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Boston, MA, USA, 18–21 September 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Jakuba, M.V.; Roman, C.N.; Singh, H.; Murphy, C.; Kunz, C.; Willis, C.; Sato, T.; Sohn, R.A. Long-baseline acoustic navigation for under-ice autonomous underwater vehicle operations. J. Field Robot. 2008, 25, 861–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McFarland, C.; Jakuba, M.; Suman, S.; Kinsey, J.; Whitcomb, L. Toward ice-relative navigation of underwater robotic vehicles under moving sea ice: Experimental evaluation in the Arctic Sea. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 1527–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francois, R.E. The Unmanned Arctic Research Submersible System. Mar. Technol. Soc. J. 1973, 7, 46–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooke, J. ARCS (Autonomous remotely controlled submersible). In Proceedings of the International Symposium of Unmanned Untethered Submersible Technology, Boston, MA, USA, 21–24 September 1981; p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, E. Autonomous remotely controlled submersible “ARCS”. In Proceedings of the 1983 3rd International Symposium on Unmanned Untethered Submersible Technology, Durham, NH, USA, 6–9 June 1983; Volume 3, pp. 77–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B. Control software in the ARCS vehicle. In Proceedings of the International Symposium of Unmanned Untethered Submersible Technology, Durham, NH, USA, 6–9 June 1985; Volume 4, pp. 334–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Light, R.D.; Morison, J. The Autonomous Conductivity-Temperture Vehicle: First in the Seashuttle Family of Autonomous Underwater Vehicle’s for Scientific Payloads. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Seattle, WA, USA, 18–21 September 1989; pp. 793–798. [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls, K.W.; Abrahamsen, E.P.; Heywood, K.J.; Stansfield, K.; Østerhus, S. High-latitude oceanography using the Autosub autonomous underwater vehicle. Limnol. Oceanogr. 2008, 53, 2309–2320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhail, S.; Furlong, M.; Pebody, M.; Perrett, J.; Stevenson, P.; Webb, A.; White, D. Exploring beneath the PIG Ice Shelf with the Autosub3 AUV. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Bremen, Germany, 11–14 May 2009; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McPhail, S.; Templeton, R.; Pebody, M.; Roper, D.; Morrison, R. Autosub Long Range AUV Missions Under the Filchner and Ronne Ice Shelves in the Weddell Sea, Antarctica—An Engineering Perspective. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2019-Marseille, Marseille, France, 17–20 June 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, A.; Bohm, H.; Laval, B.; Magnusson, E.; Yeo, R.; Doble, M. Investigation of under-ice thermal structure: Small AUV deployment in Pavilion Lake, BC, Canada. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 29 September–4 October 2007; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forrest, A.; Hamilton, A.; Schmidt, V.; Laval, B.; Mueller, D.; Crawford, A.; Brucker, S.; Hamilton, T. Digital terrain mapping of Petermann Ice Island fragments in the Canadian High Arctic. In Proceedings of the 21st IAHR International Symposium on Ice, Dalian, China, 11–15 June 2012; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Doble, M.J.; Forrest, A.L.; Wadhams, P.; Laval, B.E. Through-ice AUV deployment: Operational and technical experience from two seasons of Arctic fieldwork. Cold Reg. Sci. Technol. 2009, 56, 90–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhams, P. The use of autonomous underwater vehicles to map the variability of under-ice topography. Ocean Dyn. 2012, 62, 439–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, W.C.; Hogan, B.; Flesher, C.; Gulati, S.; Richmond, K.; Murarka, A.; Kuhlman, G.; Sridharan, M.; Siegel, V.; Price, R.M.; et al. Sub-ice exploration of West Lake Bonney: ENDURANCE 2008 Mission. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Unmanned Untethered Submersible Technology 2009 (UUST 2009), Durham, NH, USA, 23–26 August 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Richmond, K.; Febretti, A.; Gulati, S.; Flesher, C.; Hogan, B.P.; Murarka, A.; Kuhlman, G.; Sridharan, M.; Johnson, A.; Stone, W.C.; et al. Sub-Ice Exploration of an Antarctic Lake: Results from the ENDURANCE Project. In Proceedings of the International Symposium of Unmanned Untethered Submersible Technology, Portsmouth, NH, USA, 21–24 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kukulya, A.; Plueddemann, A.; Austin, T.; Stokey, R.; Purcell, M.; Allen, B.; Littlefield, R.; Freitag, L.; Koski, P.; Gallimore, E.; et al. Under-ice operations with a REMUS-100 AUV in the Arctic. In Proceedings of the IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUV), Monterey, CA, USA, 1–3 September 2010; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrandt, M.; Albiez, J.; Fritsche, M.; Hilljegerdes, J.; Kloss, P.; Wirtz, M.; Kirchner, F. Design of an autonomous under-ice exploration system. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, San Diego, CA, USA, 23–27 September 2013; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Forrest, A.L.; Lund-Hansen, L.C.; Sorrell, B.K.; Bowden-Floyd, I.; Lucieer, V.; Cossu, R.; Lange, B.A.; Hawes, I. Exploring Spatial Heterogeneity of Antarctic Sea Ice Algae Using an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Mounted Irradiance Sensor. Front. Earth Sci. 2019, 7, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spain, E.; Gwyther, D.; King, P. Submarine ventures under Sørsdal Glacier. Aust. Antarct. Mag. 2019, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Beeler, C. One Year into the Mission, Autonomous Ocean Robots Set a Record in Survey of Antarctic Ice Shelf. Available online: https://www.pri.org/stories/2019-03-06/antarctica-dispatch-7-under-thwaites-glacier (accessed on 6 March 2019).

- Hobson, B.; Raanan, B.Y. Personal communication to first Author. 25 February 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Bono, R.; Bruzzone, G.; Caccia, M.; Grassia, F.; Spirandelli, E.; Veruggio, G. ROBY goes to Antarctica. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Brest, France, 13–16 September 1994; Volume 3, pp. 621–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veruggio, G.; Bono, R.; Caccia, M. The control system of a small virtual AUV. In Proceedings of the Symposium on Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA, 19–20 July 1994; pp. 69–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoker, C.R.; Barch, D.R.; Hine III, B.P.; Barry, J. Antarctic undersea exploration using a robotic submarine with a telepresence user interface. IEEE Expert 1995, 10, 14–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caccia, M.; Bono, R.; Bruzzone, G.; Veruggio, G. Variable-configuration UUVs for marine science applications. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 1999, 6, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogel, S.W.; Powell, R.D.; Griffith, I.; Anderson, K.; Lawson, T.; Schiraga, S.A. Subglacial environment exploration—Concept and technological challenges for the development and operation of a Sub-Ice ROV’er (SIR) and advanced Sub-Ice instrumentation for short and long-term observations. In Proceedings of the IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles, AUV 2008, Woods Hole, MA, USA, 13–14 October 2008; p. 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazenave, F.; Zook, R.; Carroll, D.; Flagg, M.; Kim, S. The skinny on SCINI. J. Ocean. Technol. 2011, 6, 39–58. [Google Scholar]

- SCINI Deployment Procedures (2012–2015). 2015.

- Behar, A.E.; Chen, D.D.; Ho, C.; McBryan, E.; Walter, C.; Horen, J.; Foster, S.; Foster, T.; Warren, A.; Vemprala, S.H.; et al. MSLED: The Micro Subglacial Lake Exploration Device. Underw. Technol. 2015, 33, 3–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burnett, J.; Rack, F.; Zook, R.; Schmidt, B. Development of a Borehole Deployable Remotely Operated Vehicle for Investigation of Sub-Ice Aquatic Environments. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Washington, DC, USA, 19–22 October 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spears, A.; Howard, A.; Schmidt, B.; Meister, M.; West, M.; Collins, T. Design and development of an under-ice autonomous underwater vehicle for use in Polar regions. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 14–19 September 2014; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, M.; Dichek, D.; Spears, A.; Hurwitz, B.; Ramey, C.; Lawrence, J.; Philleo, K.; Lutz, J.; Lawrence, J.; Schmidt, B.E. Icefin: Redesign and 2017 Antarctic Field Deployment. In Proceedings of the OCEANS 2018 MTS/IEEE Charleston, Charleston, SC, USA, 22–25 October 2018; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, B.; Spears, A. Personal communication to first Author. 20 April 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Berisford, D.F.; Leichty, J.; Klesh, A.; Hand, K.P. Remote Under-Ice Roving in Alaska with the Buoyant Rover for Under-Ice Exploration; AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2013; Volume 2013, abstract ID C13C–0684. [Google Scholar]

- Aquatic Rover Goes for a Drive Under the Ice. Available online: https://www.jpl.nasa.gov/news/news.php?feature=7543 (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Clark, E. Our Biggest Day Yet. 2015. Available online: http://artemis2015.weebly.com/expedition-log/our-biggest-day-yet (accessed on 28 January 2016).

- Ferguson, J.; Pope, A.; Butler, B.; Verrall, R. Theseus AUV-two record breaking missions. Sea Technol. 1999, 40, 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- Butler, B.; Verrall, R. Precision Hybrid Inertial/Acoustic Navigation System for a Long-Range Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. Navigation 2001, 48, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellingham, J.G.; Leonard, J.J.; Vaganay, J.; Goudey, C.A.; Atwood, D.K.; Consi, T.R.; Bales, J.W.; Schmidt, H.; Chryssostomidis, C. AUV Operations in the Arctic. In Proceedings of the International Symposium of Unmanned Untethered Submersible Technology, Durham, NH, USA, 12–14 June 1993; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, D.; Morison, J. Determining Turbulent Vertical Velocity, and Fluxes of Heat and Salt with an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2002, 19, 759–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhams, P.; Wilkinson, J.; Kaletzky, A. Sidescan sonar imagery of the Winter Marginal Ice Zone obtained from an AUV. J. Atmos. Ocean. Technol. 2004, 21, 1462–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brierley, A.S.; Fernandes, P.G.; Brandon, M.A.; Armstrong, F.; Millard, N.W.; McPhail, S.D.; Stevenson, P.; Pebody, M.; Perrett, J.; Squires, M.; et al. An investigation of avoidance by Antarctic krill of RRS James Clark Ross using the Autosub-2 autonomous underwater vehicle. Fish. Res. 2002, 60, 569–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunz, C.; Murphy, C.; Singh, H.; Pontbriand, C.; Sohn, R.A.; Singh, S.; Sato, T.; Roman, C.; Nakamura, K.i.; Jakuba, M.; et al. Toward extraplanetary under-ice exploration: Robotic steps in the Arctic. J. Field Robot. 2009, 26, 411–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimball, P.; Rock, S. Sonar-based iceberg-relative navigation for autonomous underwater vehicles. Deep. Sea Res. Part II 2011, 58, 1301–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalving, B.; Faugstadmo, J.E.; Vestgard, K.; Hegrenaes, O.; Engelhardtsen, O.; Hyland, B. Payload sensors, navigation and risk reduction for AUV under ice surveys. In Proceedings of the 2008 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicles, Woods Hole, MA, USA, 13–14 October 2008; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, J. Under-ice seabed mapping with AUVs. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Bremen, Germany, 11–14 May 2009; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhams, P.; Doble, M.J. Digital terrain mapping of the underside of sea ice from a small AUV. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2008, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wulff, T.; Lehmenhecker, S.; Hoge, U. Development and operation of an AUV-based water sample collector. Sea Technol. 2010, 51, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Wulff, T.; Lehmenhecker, S.; Bauerfeind, E.; Hoge, U.; Shurn, K.; Klages, M. Biogeochemical research with an Autonomous Underwater Vehicle: Payload structure and Arctic operations. In Proceedings of the 2013 MTS/IEEE OCEANS-Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 10–14 June 2013; pp. 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wulff, T. Physics and Ecology in the Marginal Ice Zone of the Fram Strait—A Robotic Approach. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bremen, Bremen, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, R.S.; Rock, S.P.; Hobson, B. Iceberg Wall Following and Obstacle Avoidance by an AUV. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/OES Autonomous Underwater Vehicle Workshop (AUV), Porto, Portugal, 6–9 November 2018; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Hopcroft, R. Pelagic ROV Dive. 2002. Available online: https://oceanexplorer.noaa.gov/explorations/02arctic/logs/aug22/aug22.html (accessed on 2 February 2016).

- Hobson, B.W.; Sherman, A.D.; McGill, P.R. Imaging and sampling beneath free-drifting icebergs with a remotely operated vehicle. Deep. Sea Res. Part II Top. Stud. Oceanogr. 2011, 58, 1311–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolaus, M.; Katlein, C. Mapping radiation transfer through sea ice using a remotely operated vehicle (ROV). Cryosphere 2013, 7, 763–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lange, B.A.; Katlein, C.; Nicolaus, M.; Peeken, I.; Flores, H. Sea ice algae chlorophyll a concentrations derived from under-ice spectral radiation profiling platforms. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2016, 121, 8511–8534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arndt, S.; Meiners, K.M.; Ricker, R.; Krumpen, T.; Katlein, C.; Nicolaus, M. Influence of snow depth and surface flooding on light transmission through Antarctic pack ice. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2017, 122, 2108–2119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakuba, M.V.; German, C.R.; Bowen, A.D.; Whitcomb, L.L.; Hand, K.; Branch, A.; Chien, S.; McFarland, C. Teleoperation and robotics under ice: Implications for planetary exploration. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Aerospace Conference, Big Sky, MT, USA, 3–10 March 2018; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2018; pp. 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Katlein, C.; Arndt, S.; Nicolaus, M.; Perovich, D.K.; Jakuba, M.V.; Suman, S.; Elliott, S.; Whitcomb, L.L.; McFarland, C.J.; Gerdes, R.; et al. Influence of ice thickness and surface properties on light transmission through Arctic sea ice. J. Geophys. Res. Ocean. 2015, 120, 5932–5944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, J.; Li, S.; Li, Y.; Wang, X.; Chen, Q.; Lei, R.; Li, T. The observation of sea ice in the six Chinese National Arctic Expedition using Polar-ARV. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, Washington, DC, USA, 19–22 October 2015; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, S.A.; Humphreys, D.E.; Sherman, J.; Osse, J.; Jones, C.; Leonard, N.; Graver, J.; Bachmayer, R.; Clem, T.; Carroll, P.; et al. Underwater Glider System Study: Scripps Institution of Oceanography Technical Report No. 53; Technical Report; Scripps Institution of Oceanography: La Jolla, CA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Claus, B.; Bachmayer, R. Energy optimal depth control for long range underwater vehicles with applications to a hybrid underwater glider. Auton. Robot. 2016, 40, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, C.; Webb, D.; Glenn, S.; Schofield, O.; Kerfoot, J.; Kohut, J.; Aragon, D.; Haldeman, C.; Haskin, T.; Kahl, A.; et al. Slocum Glider Expanding the Capabilities. In Proceedings of the 17th International Symposium on Unmanned Untethered Submersible Technology 2011 (UUST 2011), Portsmouth, NH, USA, 21–24 August 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Bachmayer, R.; deYoung, B. Mapping the underside of an iceberg with a modified underwater glider. J. Field Robot. 2019, 36, 1102–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, S.E.; Lee, C.M.; Gobat, J.I. Preliminary Results in Under-Ice Acoustic Navigation for Seagliders in Davis Strait. In Proceedings of the IEEE/MTS Oceans Conference and Exhibition, St. John’s, NL, Canada, 14–19 September 2014; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Webster, S.; Freitag, L.; Lee, C.; Gobat, J. Towards real-time under-ice acoustic navigation at mesoscale ranges. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Seattle, WA, USA, 26–30 May 2015; pp. 537–544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hickey, H. One Year into the Mission, Autonomous Ocean Robots Set a Record in Survey of Antarctic Ice Shelf. Available online: https://www.washington.edu/news/2019/01/23/one-year-into-their-mission-autonomous-ocean-robots-set-record-in-survey-of-antarctic-ice-shelf (accessed on 18 March 2020).

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).