Abstract

In the early 2000s, Vietnam’s government concentrated on the promotion of supporting industries which can be seen as a “key” solution to sustaining economic growth, thereby improving the national welfare. However, Vietnam’s supporting industries still exhibit lower development and competitive weakness. The main reason for this condition is due to a lack of capital, technological innovation, and necessary management skills for development. Therefore, attracting foreign direct investment (FDI) for developing supporting industries offers the best strategy to realize this solution. However, attracting FDI to develop supporting industries represents a weakness which lies in both the quantity (total capital and projects) and quality of investment. So which factors are effective to attract FDI for developing supporting industries in Vietnam? This investigation establishes an analytical hierarchy framework available to the Vietnamese government and to policymakers in order to evaluate the influence of criteria needed to attract FDI for developing supporting industries based on eight main criteria. They include legal and institutional criteria, the market size of supporting industries, human resources, infrastructure facilities, technological development and innovation, domestic supply capacity, international cooperation and competition, and other criteria. This paper uses fuzzy preference relations (FPR) to evaluate the influence of criteria necessary to attract FDI for developing supporting industries, and these analytical results demonstrate that legal and institutional criteria, domestic supply capacity, human resources, technology development and innovation are all major considerations for attracting FDI.

1. Introduction

Vietnam has been late in developing its economy, which it started to reform in 1986 [1] and became emergent in the early 1990s [2]. The Vietnamese government decided, until 2020, to follow the process of industrialization and modernization to achieve success [3]. The government’s policy changed in 1991, and since then Vietnam has been pursuing an economic policy to join the global economy, such as the lifting of the United States (US) trade embargo in 1994, joining the ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asia Nations) in 1995 and the WTO (World Trade Organization) in 2007 [4]. Therefore, to successfully implement the process of industrialization and modernization, along with international economic integration, it is necessary to reduce dependence on imported goods and a burgeoning trade deficit [5]. Instead, Vietnam should actively pursue the supply of goods in the chain of production [6]. Competitive supporting industries may consistently contribute to the economic development and national welfare [7]. Such development causes a dynamic effect to occur that will promote technological innovation and human resources [8]. Moreover, the most important aspect for developing countries to improve economic self-sufficiency is to establish competitive supporting industries for foreign direct investment (FDI)-driven economic growth [9]. So, in the early 2000s, the Vietnamese government began to concentrate on promoting supporting industries which can be seen as a “key” solution towards economic sustainability for the development of the country, and thereby improve national welfare [5]. It is expressed in the decisions and policies that have been made [10,11,12,13,14].

Currently, the term “supporting industries” is using widely, especially in East Asia. It is interpreted differently in various fields of activity [15,16]. Supporting industries may be defined as a group of producers of manufactured inputs in which finished goods are produced through manufacturing processes consisting of both manufacturing inputs and assembly processes [5]. Supporting industries produce these inputs, more specifically, as intermediate and finished capital goods. The White Paper on Economic Cooperation of the Ministry of International Trade and Industry of Japan (MITI) defined supporting industries as the supply of raw materials, and those parts and capital goods used in assembly-type industries [17]. The United States (US) Department of Energy has defined supporting industries as those which supply materials and processes that are necessary to form and fabricate products before they are marketed to end-use industries [18]. In Vietnam, supporting industries are defined in accordance with Decision No. 12/2011/QĐ-TTg, promulgated by the Prime Minister: “The supporting industries are industries producing materials, spare parts, components, accessories or semi-finished products as means of the production of final products in production and assembly industries or of consumer products” [14]. The list of supporting industry products which are given priority for development are found under Decision No. 1483/QĐ-TTg by the Prime Minister, on 26 August 2011, including six industries: textile and apparel, leather and footwear, electronic and information industries, the manufacturing and assembly of automobiles, the mechanical industry, and supporting industry products for high-tech industries [13].

Vietnam’s supporting industries are still in the process of slowly developing. The situation of supporting industries in Vietnam is one of competitive weakness [9,19]. Due to the underdeveloped state of the local supporting industry in Vietnam, increased production costs, the risk of bigger trade deficits with foreign partners, lowered competitiveness of local products compared with regional peers, and imports of more expensive components and spare parts mostly purchased from Asian markets have greatly weakened Vietnam’s supporting industries [19,20]. The weakness of these industries is viewed to be one of the primary factors preventing industrial development and economic growth from taking place, as well as benefiting national welfare [5]. Some of the major factors leading to the weakness of supporting industries in Vietnam are a lack of capital, technological innovation, and the dearth of management skills for leading development [6]. While FDI is an important vehicle for the transfer of technology, contributing relatively more to growth than domestic investment [21,22], FDI significantly increases economic growth of recipient countries by bringing physical, advanced technological, and management expertise to bear [23,24,25]. Moreover, FDI is considered to increase domestic capital, to create employment and to raise incomes, to promote technology and to generate the transfer of skills through foreign technology and technical know-how, to boost host country economies, and investment, seen as the engine of economic growth in the long-term [26,27]. Therefore, attracting FDI for developing supporting industries is the best strategy to solve the problem of insufficient capitalization; however, attracting FDI for developing supporting industries in Vietnam is also a show of weakness, both in terms of quantity (total capital and projects) and quality [9]. As such, this study demonstrates which main factors are effective to attract FDI for developing supporting industries in Vietnam.

This study concentrates on identifying the main factors influencing the attraction of FDI for developing supporting industries in Vietnam and for evaluating them. This theoretical study involves personal interviews of involved policymakers, economists, foreign investors, and managers of six supporting industries, and practical considerations of the real situation of developing supporting industries hoping to attract FDI for developing supporting industries; the result indicates that there are eight main criteria influencing to attract FDI for developing supporting industry. These eight main criteria include the following: (1) the legal and institutional framework; (2) the market size of supporting industries; (3) domestic supply capacity; (4) technological development and innovation; (5) human resources; (6) infrastructure facilities; (7) international cooperation and competition; and (8) other criteria [28,29,30,31,32]. From those results, an analytical hierarchy framework to help Vietnam’s government and responsible policymakers to evaluate the influence of criteria to attract FDI to develop supporting industries based on the eight main criteria is established.

Accordingly, the analytic hierarchy process (AHP) method performs complicated pairwise comparison among the criteria [33], and it takes considerable time to obtain a convincing consistency index with an increasing number of criteria. In the fuzzy analytic hierarchy process (fuzzy AHP) method, establishing a pairwise comparison matrix requires n(n − 1)/2 judgments for a level with n criteria (alternatives). The number of comparisons increases as the number of criteria increases [33,34]. However, fuzzy preference relations was proposed method yields consistent decision rankings from only (n − 1) pairwise comparisons [35]. Therefore, the presented fuzzy preference relations method is an easy and practical way of making decisions. This study uses the fuzzy preference relations (FPR) [35,36,37,38,39] to calculate the criteria weights. This result will make clear the most important criteria.

2. Related Literature

2.1. The Role of Supporting Industries For Economic Growth

There are two questions that may arise: “What role can supporting industries play in promoting economic growth?” and “If a country has developed competitive supporting industries then would this country promote long-run economic development, or not?” This is the possible answer to those questions. The regular development of competitive supporting industries causes the dynamic effects in the promotion of technological innovation, thereby improving national welfare [8,40]”. Porter mentions that any globally competitive companies may benefit from domestic supporting industries, although it is unnecessary to become competitive in all supporting industries if there is specialization taking place in certain areas [41]. It is decidedly beneficial for developing countries to establish competitiveness standards among supporting industries for long-run economic growth to occur. Vietnam is considered a developing country at this time in the country’s relative growth, and the process of industrialization and modernization is still progressing on a post-war and post-colonial footing [2,42,43,44,45]. Therefore, the Vietnamese government is concentrating on promoting supporting industries. This is expressed through Vietnam supporting industry prospects under assessment by Japanese enterprises [46,47], and the decisions and policies under the aegis of Decision 34/2007/QD-BCN. This decision was promulgated on 31 July 2007 by the Minister of Industry and Trade: “Approving the planning of industrial development supports up to 2010 and vision to 2020” [11]. Further, other equally important decisions have been made to promote supporting industrial growth: Decision 12/2011/QD-TTg, on 24 February 2011, by the Prime Minister: “On development policies of some supporting industries” [14]; Decision 1843//QD-TTg, on 26 August 2011, by the Prime Minister: “On promulgating list of supporting industry products which are given priority for development” [13]; Decision 1556/QD-TTg, on 17 October 2012, by the Prime Minister: “Approval scheme, help developing small and medium enterprises in supporting industries field” [12]; and Decision 9028/QD-BCT, on 10 October 2014, by the Minister of Industry and Trade: “Approval master plan for developing supporting industries up to 2020, vision to 2030” [10]. However, the situation of Vietnam’s supporting industries is still materialized as slow development and competitive weakness. As a result, it is shown too minimally in the proportion of localization found in the amount of finished products. According to Vietnamese Governmental Reports [48] and General Statistics Office of Vietnam [49], the proportion of localization in the finished products of some supporting industries is as follows: 35.5% in mechanical industry; 32.5% in textile and apparel; 21.1% in leather and footwear; 16.8% in electronic and information industries; and 26.5% in manufacturing and the assembly of automobiles. Some of the major factors leading to the weakness of supporting industries in Vietnam are the lack of capital, insufficient technological innovation, and the dearth of management skills for development. So, the Vietnamese government should concentrate on developing supporting industries within Vietnam.

2.2. Attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) for Developing Supporting Industries and Economic Growth to Occur

Developing countries can be improved national welfare by attracting FDI. It is FDI that supports economic growth, increases incomes, and promotes a greater rate of employment and technological transfer [27,50,51,52]. Assumedly, FDI could have beneficial spillover effects on the host countries, which may include the enhancement of job creation, knowledge transfer, and capital accumulation. Five main channels of technological diffusion are linked to FDI flows: Demonstration or imitation, exportation, competition, labor mobility, and backward and forward linkages with domestic firms [40,53]. Moreover, the customer base of supporting industries may include domestic assemblers, foreign assemblers located in the domestic market, and foreign assemblers in foreign countries. Foreign assemblers are often multi-national enterprises (MNEs) [40]. Research supports the theory that MNEs tend to have higher productivity than domestic firms if in the same sector and thereby contribute to GDP growth in developing countries [6,16]. Together, Dunning proposed the OLI, which stands for Location, Ownership, and Internalization, three potential sources of advantage that may underlie a firm’s decision to become a multinational. Wherein, location advantages focus on the question of where MNEs chooses to locate. They seek to avail of lower production costs in that locale [54]. Seemingly, developing countries expect that MNEs will be a positive impact on the productivity levels of domestic firms through a generation of positive externalities. FDI may generate positive externalities for the productivity growth of domestic suppliers through business relationships with MNEs (to be called “backward linkages” afterward) [40,51]. Moreover, the output and productivity of domestic supporting industries will be increased due to the additional demand and technology transfer that is caused by MNEs [16]. Furthermore, if increasing FDI causes positive externalities occurs for domestic suppliers and improves their productivity through backward linkages, national welfare in FDI host countries will also be improved [27,52].

In summary, developing countries will be improved national welfare by attracting FDI if their supporting industries will obtaining positive externalities that far exceed negative externalities present for domestic assemblers [5,40]. Finally, Porter stresses the importance of competitive supporting industries as a partner in any MNCs’ dynamic technology innovation, which serves as its obvious role as a recipient of technology transferred from the MNCs [41]. Therefore, it is important for developing countries strive to establish competitive supporting industries to achieve FDI-driven economic growth. In addition, domestic supporting industry is increasing their importance as a factor useful to attract FDI [8,9]. Additionally, in the reverse, FDI will promote developing supporting industries. From the real situation of developing supporting industries and attracting FDI to develop supporting industries, together with the results of the interviews with policymakers, economists, foreign investors and managers of six supporting industries, there are eight important factors for investment decision of foreign investors to invest into supporting industries in Vietnam. These factors have been identified to include the legal and institutional framework, the market size of supporting industries (i.e., total consumption of supporting industries products), human resources (i.e., quantity, salary, education, skill and moral), the infrastructure facilities (i.e., transport, power, information and communication), technological development and innovation, domestic supply capacity (i.e., total value and partition domestic supply, the quantity and size of supporting industries firms), international cooperation and competition, and other criteria (such as environment policy, culture, tax policy, land support, corruption, etc.).

3. Research Methodology

In this study, the proposed procedure utilizes the fuzzy preference relations (FPR) process to evaluate the influence of criteria useful to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) for developing supporting industries in Vietnam. It will give the brief descriptions of the FPR method.

Herrera-Viedma et al. [35] proposed the fuzzy preference relations, and in accordance with fuzzy preference relation [36,37,38,39].

3.1. Fuzzy Preference Relation

Expert preferences over a set of alternatives where X is denoted by a positive preference relation matrix with membership function: , where indicates the ratio of the preference intensity of alternative xi to that of xj. Moreover, if pij = implies indifference between xi and xj (xi ~ xj), indicates that xi is absolutely preferred to xj, indicates xj is absolutely preferred to xi, and pij > indicates that xi is preferred to , . Meanwhile, P is assumed to be an additive reciprocal, that is:

Proposition 3.1. Suppose that there is a set of alternatives, , and is associated with it a reciprocal multiplicative preference relation with . Then, the corresponding reciprocal fuzzy preference relation, with, , associated with A is given as follows:

With this type of transformation function g, it can be related the research issues obtained for both kinds of preference relations.

3.2. On the Consistency of the Fuzzy Preference Relations

Proposition 3.2. Let be a consistent multiplicative preference relations, then the corresponding reciprocal fuzzy preference relations, , verifies the additive transitivity property.

Proof. For being consistent it has that , or equivalently . Taking logarithms on both sides, it has

Adding Equation (3) and dividing by Equation (2) on both sides then

The fuzzy preference relations , being , verifies

It follows that verifies the additive transitivity property.

In such a way, in this paper, it considers the following definition of the consistent fuzzy preference relation:

Definition 3.1. A reciprocal fuzzy preference relation is consistent if

In what follows, it will be using the term additive consistency to refer to consistency for fuzzy preference relations based on the additive transitivity property.

3.3. Additive Transitivity Consistency of the Fuzzy Preference Relations

Proposition 3.3-1. For a reciprocal fuzzy preference relation , the following statements are equivalent:

Proposition 3.3-2. A fuzzy preference relation is consistent if and only if

Proposition 3.3-3. For a reciprocal additive fuzzy preference relation , the following statements are equivalent:

4. Framework for Evaluating the Influence of Criteria to Attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) for Developing Supporting Industries in Vietnam under a Multi-Criteria Decision Making Process

4.1. Evaluated Criteria and Framework of the Evaluation Model

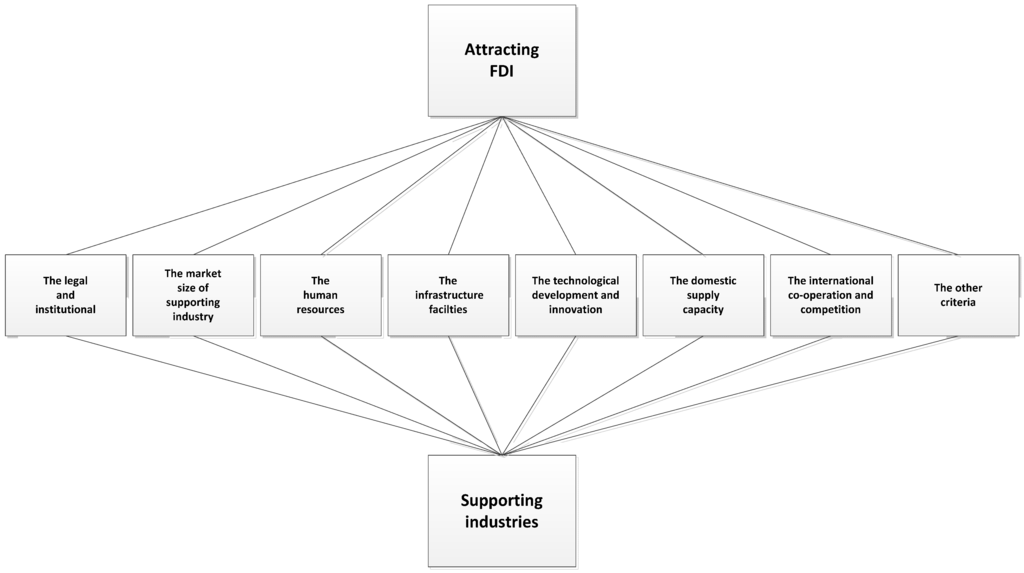

This study interviewed policymakers, economists, and foreign investors and managers of six supporting industries, together with the real situation of developing supporting industries and attracting FDI for developing supporting industries. It identified criteria and their attributes to be summarized as follows: the legal and institutional; the market size of supporting industries (total consumption of supporting industries product); domestic supply capacity (as total supply, quantity and size of supporting industries firms); the technological development and innovation; the human resources (i.e., quantity, salary, education, skill and moral); the infrastructure facilities (i.e., transport, power supply, information and communication,…); international cooperation and competition; the other criteria (culture, tax policy, land support, corruption, environment, etc.). An analytical hierarchy framework based on eight main criteria is established as the Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The analytical framework of this study.

Within the framework of attracting FDI for developing supporting industries, there are eight main criteria that influence the attraction of FDI.

4.2. Hierarchical Analytical Process to Evaluate the Influence of Criteria to Attract Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) for Developing Supporting Industries

4.2.1. Linguistic Variables

This paper compares pairs of criteria using expressions such as ‘‘Equally important (EQ)”, ‘‘Moderately important (MO)”, ‘‘Strongly important (ST)”, ‘‘Very strong importance (VS)”, and ‘‘Absolutely important (AB)”, using a five-level scale with values indicated by actual numbers (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Linguistic terms for priority weights of influential factors.

4.2.2. Reciprocal Additive Consistent Fuzzy Preference Relations for Prioritizing the Evaluation Criteria

AHP separates a complex decision issue that creates elemental problems to produce a hierarchical model. Each of these preference relations is required the completion of all judgments for a preference matrix containing n elements to be formed. To reduce the judgment times, this paper employs the reciprocal additive consistent fuzzy preference relations designed by Herrera-Viedma et al. [11], because it only requires judgments from a set of n elements.

The procedures of the reciprocal additive consistent fuzzy preference relations for prioritizing the assessment criteria are given below:

(1) This study establishes pairwise comparison matrices for all the criteria in the dimensions of the hierarchy system. The evaluators provide the more important of each of the pairs of considered criteria for a set of n-1 preference values , for

where denotes the preference intensity toward considered criteria i and j are assessed by evaluator k, indicates no difference between considered criteria i and j, reveals that criteria i relatively important to criteria j, and indicates that considered criteria i is less important than criteria j. The sign ‘‘x” indicates the remaining , which can be done via inverse comparison.

(2) Transform the preference value into using an interval scale , then derive the remaining based on the reciprocal transitivity property, as follows:

where indicates no difference between criteria i and j, demonstrates that criteria i is absolutely important to criteria j, and illustrates that the criteria is absolutely less important to criteria j. The remaining can be calculated using Equations (1) and (11), but in an interval , and a transformed function is necessary to preserve the reciprocity and additive transitivity. The transformation function is, as follows:

where a denotes the absolute value of the minimum negative value or maximum positive value minus one in this preference matrix.

(3) Base on the opinions of evaluators will be obtained the aggregated weights of the criteria. Moreover, let denote transforming the fuzzy preference value of evaluator k for assessing the criteria i and j. This paper uses the notation of the average value to integrate the judgment values of m evaluators, namely:

(4) Normalizing the aggregated fuzzy preference relation matrices is used to indicate the normalized fuzzy preference values of each considered criteria, such as

(5) Using the denoting the average priority weight of considered criteria, the priority of each criteria can be obtained, that is

where n denotes the number of criteria considered.

5. Results

This study made use of six supporting industries in Vietnam as an example to demonstrate the framework. A total of 15 questionnaires were dispatched, and survey candidates included policymakers, economists, foreign investors and managers from six supporting industries.

Eight major evaluation criteria are useful to assess the problem of how FDI attracts developing supporting industries. The pairwise comparisons for these eight criteria are obtainable via interviews with the assessment representatives mentioned above.

The following examples will be clarify the computational process used to receive the priority weights utilizing a reciprocal additive consistent with the fuzzy preference relation approach:

(1) Based on interviews with 15 representatives regarding the importance of eight evaluation criteria, Table 2 lists the pairwise comparison matrices for a set of neighboring criteria into the corresponding number.

Table 2.

The linguistic terms into corresponding numbers toward eight factors assessed by evaluators.

(2) The assessment of evaluator 1 (E1) can be served as an example and listed in Table 3. The linguistic terms, which can be transferred into corresponding numbers.

Table 3.

Interval pairwise comparisons of the criteria.

(3) Equation (2) was used to transform the elements (listed in Table 3) into an interval [0, 1], yielding the following values:

- .

The remaining value then can be calculated using Equations (1) and (11) with , , , , and being used as examples:

The fuzzy preference relation matrix for eight evaluation criteria assessed by evaluator 1 is established in Table 4.

Table 4.

Consistent fuzzy preference relation matrix of criteria E1.

Table 4 lists , , , , , , , , , elements not in the interval [0,1]. Therefore, a linear transformation stated in Equation (14) will be employed to ensure the reciprocity and additive transitivity for the preference relation matrix. Table 5 lists the transformation matrix.

Table 5.

The transformation matrix of criteria by linear solution.

(4) Likewise, the above computational procedures have calculated the fuzzy preference relation matrices of the other 14 evaluators; therefore, using Equation (15), the aggregated pairwise comparison matrix of 15 evaluators will be derived, as listed in Table 6.

Table 6.

Aggregated pairwise comparison matrices of 15 evaluators.

(5) Equation (16) is applied to normalize the aggregated pairwise comparison matrix. Taking as an example:

The priority weight of each evaluation criteria can then be obtained by Equation (17). The priority weight and rank of each influence assessed by 15 evaluators is listed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Normalized matrix of priority weight and rank of influential factors.

The ranks of the evaluation criteria weights are thus substituted as:

C1(0.1862) > C3(0.1650) > C5(0.1536) > C4(0.1268) > C6(0.1251) > C2(0.1192) > C8(0.0661) > C7(0.0580).

The results show that the five main assessment attributes are legal and institutional framework (0.1862), domestic supply capacity (0.1650), human resources (0.1536), technological development and innovation (0.1268), and infrastructure facilities (0.1251). Meanwhile, the three least important attributes are market size of supporting industries (0.1192), international cooperation and competition (0.0661), and other criteria (0.0580).

6. Conclusions

This study surveyed approximately 15 policymakers, managers and economists to identify their assessment criteria discussed above. Based on the opinions derived from all survey respondents, this study finding were obtained:

The legal and institutional framework is the most important criteria for influencing the attraction of FDI for developing supporting industries, and which is considered by supporting industries to attract FDI. Vietnam has chosen to join AFTA (ASEAN Free Trade Area) and the WTO, which means that the Vietnamese government should concentrate on building special policies for the promotion of supporting industries involved with the change and improvement of the legal and institutional framework.

Domestic supply capacity, human resources, technological development and innovation, and infrastructure facilities have also received heavy-weight influence to attract FDI for the development of supporting industries. Notably, international co-operation and competition along with other criteria have not been taken seriously.

The fuzzy preference relations (FPR) method used to evaluate the influence of criteria to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) for developing supporting industries in Vietnam presented here is clearly applicable to the evaluation process. This paper proposed evaluation also reveals the concerns and preferences of all supporting industries and main industries. The results of this study provide a valuable reference for the Vietnamese government and policymakers to improve the legal and institutional framework, domestic supply capacity, human resources, technological development and innovation, and infrastructure facilities assistance, leading to the kind of environmental investment requisite to attracting FDI to develop supporting industries. Together, based on these results, we are continuing to survey on a large scale for future research to select a strategy for attracting FDI for supporting industries in Vietnam.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/8/5/447/s1.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on this article.

Author Contributions

Tien-Chin Wang, Chia-Nan Wang, and Nguyen-Xuan Huynh designed the research and methodology; Nguyen-Xuan Huynh collected and analyzed the data; Tien-Chin Wang, Chia-Nan Wang, and Nguyen-Xuan Huynh wrote and revised the paper; Tien-Chin Wang, and Nguyen-Xuan Huynh corrected the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Communist Party of Vietnam. Resolutions of the 6th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam; Communist Party of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 1986. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Communist Party of Vietnam. Resolutions of the 7th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam; Communist Party of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 1991. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Communist Party of Vietnam. Resolutions of the 9th National Congress of the Communist Party of Vietnam; Communist Party of Vietnam: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2001. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Narayan, S.; Nguyen, T.T. Does the trade gravity model depend on trading partners? Some evidence from Vietnam and her 54 trading partners. Int. Rev. Econ. & Finance 2016, 41, 220–237. [Google Scholar]

- Chau, N.V.; Huong, P.T.; Tien, Đ.N. Supporting Industries: Experience from other country and solution for Vietnam; Information and Communication Publisher: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2010; pp. 43–323. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, K. Vietnam at the Crossroads: Policy Advice from the Japanese Perspective. Available online: http://www.grips.ac.jp/vietnam/KOarchives/doc/EP14_PN1.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2016).

- Ohno, K.; National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies; Vietnam Development Forum (VDF). Building Supporting Industries in Vietnam - Vol.1; Vietnam Development Forum: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Ichikawa, K. Building and Strengthening Supporting Industries in Vietnam. Available online: http://www.grips.ac.jp/vietnam/KOarchives/doc/EB02_IIPF/5EB02_Chapter4.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2016).

- Industrial Policy and Strategy Institute. Overall Policy Developing Supporting Industries in Terms of Integration; Industrial Policy and Strategy Institute: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2010. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Industry and Trade. Approving the Master Plan for Supporting Industrial Development by 2020, with a Vision to 2030; No.9028/QD-BCT; Ministry of Industry and Trade: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014.

- Ministry of Industry and Trade. Approving the Planning of Industrial Development Supports Up to 2010 and Vision to 2020; No.34/2007/QD-BCN; Ministry of Industry and Trade: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2007. (In Vietnamese)

- The Prime Minister. Supporting the Development of Medium and Small Enterprises Engaged in Ancillary Industries; No.1556/QD-TTg; The Prime Minister: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- The Prime Minister. Promulgating the List of Products of Support Industries Prioritized for Development; No.1483/QD-TTg; The Prime Minister: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- The Prime Minister. Policies on Development of a Number of Supporting Industries; No.12/2011/QD-TTg; The Prime Minister: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Inoue, R.; Itoga, S. Future Prospects of Supporting Industries in Thailand and Malaysia; APEC Study Center, Institute of Developing Economies: Chiba, Japan, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Uchikawa, S. Small and Medium Enterprises in Japan: Surviving the Long-Term Recession. Available online: http://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/156024/adbi-wp169.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2016).

- Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI). Keizai kyouryoku hakusho (White Paper on Economic Cooperation); MITI: Tokyo, Japan, 1985.

- U.S. Department of Energy. Supporting Industries Annual Report, Fiscal Year 2003; Industrial Technologies Program, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, U.S. Department of Energy: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Industrial Policy Formulation in Thailand, Malaysia and Japan. Available online: http://www.grips.ac.jp/vietnam/VDFTokyo/Doc/TMJreportEN.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2016).

- Vietnam Development Forum; Japan International Cooperation Agency. Survey Compares Context, Policy Measures and Results Developing Supporting Industries in ASEAN; Transport Publisher: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Borensztein, E.; de Gregorio, J.; Lee, J.W. How does foreign direct investment affect economic growth? J. Int. Econ. 1998, 45, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.H.; Yang, T.T.; Chen, C.B.; Chen, Y.L. A fuzzy hierarchy integral analytic expert decision process in evaluating foreign investment entry mode selection for Taiwanese bio-tech firms. Expert Syst. Appl. 2011, 38, 3304–3322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villaverde, J.; Maza, A. The determinants of inward foreign direct investment: Evidence from the European regions. Int. Bus. Rev. 2015, 24, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, W.; Yeaple, S. Multinational enterprises international trade and productivity growth: Firm-level evidence from the United Stated. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2009, 91, 821–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.K.; Kwan, Y.K. What are the determinants of the location of foreign direct investment? The Chinese experience. J. Int. Econ. 2000, 51, 379–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman, E. Implications of aggregate demand on employment: evidence from the Romanian economy. Young Economists J. 2011, 9, 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Fabry, N.; Zeghni, S. How former communist countries of Europe may attract inward foreign direct investment? A matter of institutions. Communist Post-Communist Stud. 2006, 39, 201–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groh, A.P.; Wich, M. Emerging economies’ attraction of foreign direct investment. Emerg. Markets Rev. 2012, 13, 210–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danciu, A.R.; Strat, V.A. Factors influencing the choice of the foreign direct investments locations in the Romanian regions. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 109, 870–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.I.; Yeh, C.H. Re-examining location antecedents and pace of foreign direct investment: Evidence from Taiwanese investments in China. J. Bus. Res. 2012, 65, 1171–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytch, N. Sectoral FDI cycles in south and East Asia. J. Asian Econ. 2015, 36, 24–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, W.; Mourmouras, A. IMF surveillance as a signal to attract foreign investment. Int. Rev. Econ. Finance 2010, 19, 562–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levary, R.R.; Wan, K. An analytic hierarchy process based simulation model for entry mode decision regarding foreign direct investment. Omega 1999, 27, 661–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.C.; Chen, Y.H. Applying fuzzy linguistic preference relations to the improvement of consistency of fuzzy AHP. Inf. Sci. 2008, 178, 3755–3765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Viedma, E.; Herrera, F.; Chiclana, F.; Luque, M. Some issues on consistency of fuzzy preference relations. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2004, 154, 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.C.; Chang, T.H. Application of consistent fuzzy preference relations in predicting the success of knowledge management implementation. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2007, 182, 1313–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.C.; Chang, T.H. Forecasting the probability of successful knowledge management by consistent fuzzy preference relations. Expert Syst. Appl. 2007, 32, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.C.; Chen, Y.H. Applying consistent fuzzy preference relations to partnership selection. Omega 2007, 35, 384–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.C.; Lin, Y.L. Applying the consistent fuzzy preference relations to select merger strategy for commercial banks in new financial environments. Expert Syst. Appl. 2009, 36, 7019–7026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center Institute of Economic Management. Subcontracting and Outsourcing, Economic Linkage between Large and Small Enterprises: Dispute Settlement and Contract Implementation; Center Institute of Economic Management: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2004. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Porter, M.E. The Competitive Advantage of Nations. Available online: https://hbr.org/1990/03/the-competitive-advantage-of-nations (accessed on 25 April 2016).

- Industrial Policy and Strategy Institute. Development Planning of Vietnam’s Automobile Industries Up to 2020 and Vision to 2030; Industrial Policy and Strategy Institute: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Industrial Policy and Strategy Institute. Supporting Industries for Textile & Apparel Vietnam; Industrial Policy and Strategy Institute: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Industrial Policy and Strategy Institute. Research Capacity Assessment of Industrial Enterprises Supporting Mechanical Industry and Proposed Models of Long-Term Links; Industrial Policy and Strategy Institute: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2011. (In Vietnamese) [Google Scholar]

- Ohno, K. Avoiding the middle-income trap: Renovating industrial policy formulation in Vietnam. ASEAN Econ. Bull. 2009, 26, 25–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Supporting Industries in Vietnam from the Perspective of Japanese Manufacturing Firms. Available online: http://www.grips.ac.jp/vietnam/KOarchives/doc/EP19_SI.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2016).

- Small & Medium Enterprise Development Policies in 6 ASEAN Countries. Available online: http://www.asean.org/storage/images/archive/documents/SME%20Development%20Policies%20in%206%20ASEAN%20Member%20States%20-%20Part%201.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2016).

- Vietnam Government. Vietnam Government Report: The Implementation of Socio-Economic Development in 2013; Vietnam Government: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2014. (In Vietnamese)

- General Statistics Office of Vietnam (GSO). Statistical Yearbook of Vietnam 2013; Statistics Publishing House: Hanoi, Vietnam, 2013. Available online: https://www.gso.gov.vn/default_en.aspx?tabid=515&idmid=5&ItemID=14079 (accessed on 25 April 2016).

- Kardos, M. The relevance of foreign direct investment for sustainable development: Empirical evidence from European Union. Procedia Econ. Finance 2014, 15, 1349–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytch, N.; Uctum, M. Does the worldwide shift of FDI from manufacturing to services accelerate economic growth? A GMM estimation study. J. Int. Money Finance 2011, 30, 410–427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doytch, N.; Narayan, S. Does FDI influence renewable energy consumption? An analysis of sectoral FDI impact on renewable and non-renewable industrial energy consumption. Energy Econ. 2016, 54, 291–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, N.; Fontoura, M.P. Determinant factor of FDI spillovers: What do we really know? World Dev. 2007, 35, 410–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, J.H. Trade, location of economic activity and the MNE: A search for an eclectic approach. In The International Allocation of Economic Activity; Ohlin, B., Hesselborn, P.O., Wijkman, P.M., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1977; pp. 395–418. [Google Scholar]

© 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC-BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).