Abstract

Formaldehyde-based adhesives pose health and environmental risks that hinder sustainable development of the wood-based panel industry. To address the issue that “formaldehyde emissions endanger human health and ecological safety, constraining industry sustainability,” this study aims to promote the development and application of formaldehyde-free biomass-based adhesives. Centering on technological feasibility, policy compatibility, and governance effectiveness, this research adopts a multi-dimensional systems analysis method to systematically review global progress in research and industrial application of biomass-based formaldehyde-free adhesives. The results indicate the following: (1) biomass adhesives exhibit substantial potential in mechanical performance and ecological benefits; (2) their large-scale application faces obstacles including cost, performance stability, and insufficient policy coordination; and (3) building an integrated technology–policy–governance synergy framework is the key pathway to industrialization. This study provides scientific guidance for scaling up biomass adhesives and achieving ecological civilization goals.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the global demand for wood-based panel industry continues to grow, with China’s annual output of more than 300 million cubic meters of wood-based panel ranking first in the world [1]. However, traditional petrochemical-based adhesives (e.g., urea–formaldehyde resins and phenol–formaldehyde resins) release volatile organic compounds (VOCs), such as formaldehyde, during synthesis and use, posing a serious threat to human health and the environment [2]. Formaldehyde is classified as a class I carcinogen by the World Health Organization, and long-term exposure can lead to respiratory diseases, immune function abnormalities and even leukemia [3,4]. At the same time, traditional adhesives rely on non-renewable fossil raw materials, their production process has high carbon emissions, and the products are difficult to degrade, leading to environmental problems such as microplastic pollution, which further aggravates the burden on the ecosystem.

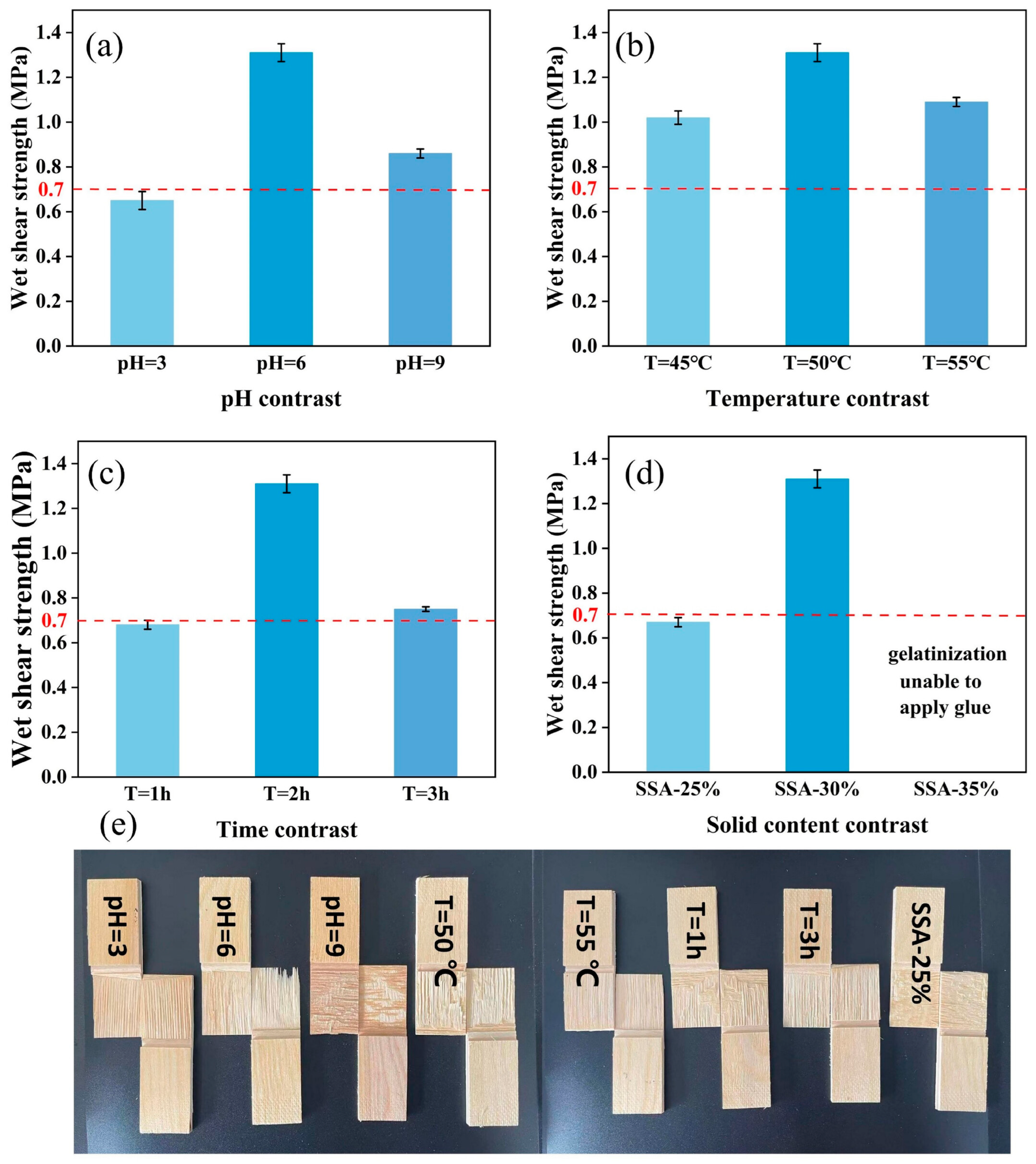

The concept of ecological civilization has been introduced as a national development principle that emphasizes the harmonious coexistence of human activities and natural systems, providing a solid framework for evaluating technological innovations in the field of materials science. Trends in social development and concerns about pollutant volatilization and the ecological footprint (sustainability) of the production of these formaldehyde- and phenolic-based adhesives have created opportunities for the development of renewable and “environmentally friendly” adhesives on the market [5]. In this context, formaldehyde-free biomass-based adhesives represent a key intersection of sustainable materials design and environmental governance, and fit with many of the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including good health and well-being, affordable and clean energy, industrial innovation and infrastructure, climate action, and terrestrial biomass [6,7]. At present, domestic and foreign research has made a series of progress in the development of biomass-based adhesives such as starch [8], lignin [9], and soy protein [10], especially in the utilization of agricultural waste (e.g., straw, peanut meal) and other high-value resources, which shows great potential and provides a technological pathway for the circular economy. However, these biomass adhesives still generally have technical bottlenecks such as insufficient water resistance and low wet strength, resulting in their product performance not yet being able to fully meet the stringent requirements of the national standards for wood-based panels (e.g., GB/T 9846-2015) [11], which restricts their large-scale industrialization and application. This biomass adhesive cannot be widely used because of its water resistance, wet strength and other aspects still having certain deficiencies. However, people’s interest in “environmentally friendly” biomass adhesives is still increasing, as evidenced by the increasing publication rate, as shown in Figure 1. Therefore, a systematic review of the technological progress of formaldehyde-free biomass adhesives, an in-depth analysis of the deep-rooted barriers to their promotion, and the exploration of feasible synergistic paths of “technology-policy-governance” are of great theoretical value and urgency for promoting the maturity and application of this green technology and realizing the green transformation of the wood-based panel industry.

Figure 1.

Publication of articles indexed in the ScienceDirect database using “biomass-based adhesives” as a search term since 2015.

This paper examines recent advances in formaldehyde-free biomass adhesive technology through the multiple lenses of materials science, public policy and grassroots governance. It analyzes the technological pathways for biomass resource utilization and their interface with other local policies, assesses the environmental and health benefits, identifies socioeconomic barriers to adoption at the level of the governance structure, and proposes an integrated policy strategy that blends technology diffusion and grassroots governance. By synthesizing recent scientific literature and policy documents with examples of local practices, this paper aims to provide a multidisciplinary understanding of how green adhesive technologies can contribute to the goals of sustainable development and ecological civilization for academic, industrial, and governmental stakeholders.

2. Formaldehyde-Free Adhesive Technology Innovation and Ecological Benefits

2.1. Technological Innovations in Formaldehyde-Free Adhesives

In recent years, significant progress has been made in the development of high-performance adhesive systems derived from renewable biomass resources to meet the wet strength standards of Class II plywood (≧0.7 MPa) as stipulated in the Chinese national standard (GB/T 9846-2015), and in different aspects with significant improvements and significant advantages, providing a viable alternative to petroleum-based formulations [12]. Dry bond strength refers to the shear strength of the adhesive bond when the bonded wood-based panel is in a dry state (moisture content 8–12%) after curing. It is critical for applications in dry environments such as indoor furniture and decorative panels. Wet bond strength refers to the shear strength after the bonded panel is soaked in water (usually 24 h at 25 °C or 3 h at 100 °C) to simulate humid service conditions, which is essential for scenarios such as outdoor furniture, packaging materials, and bathroom decorations. A comparison of the performance characteristics of different formaldehyde-free adhesive technologies is shown in Table 1. (1) Water resistance: biomass raw materials (lignin, protein, starch) contain a large number of hydrophilic groups (hydroxyl, amino, carboxyl), which easily form hydrogen bonds with water molecules, leading to swelling and failure of the adhesive layer. (2) Cross-linking density: The cross-linking degree of biomass adhesives is generally lower than that of petroleum-based adhesives, resulting in loose internal structure and easy penetration of water molecules. (3) Interface compatibility: The hydrophilicity of the adhesive is inconsistent with the hydrophobicity of the wood surface, leading to incomplete wetting and bonding, which further deteriorates wet strength. Additionally, the diversity of biomass raw materials leads to uneven reactivity, making it difficult to control the cross-linking reaction uniformly, which also affects performance stability.

Table 1.

Comparison of performance characteristics of different aldehyde-free adhesive technologies: SM-OL1.5 adhesives [13], ALN-50 adhesives [14], SPI/SA/Mg adhesives [15], SPI/TA 0.5/Borax 0.6 adhesives [16], DAS-HBP-G adhesives [17], Ost/Ita/Borax adhesives [18], and HM-CS@BN adhesives [19].

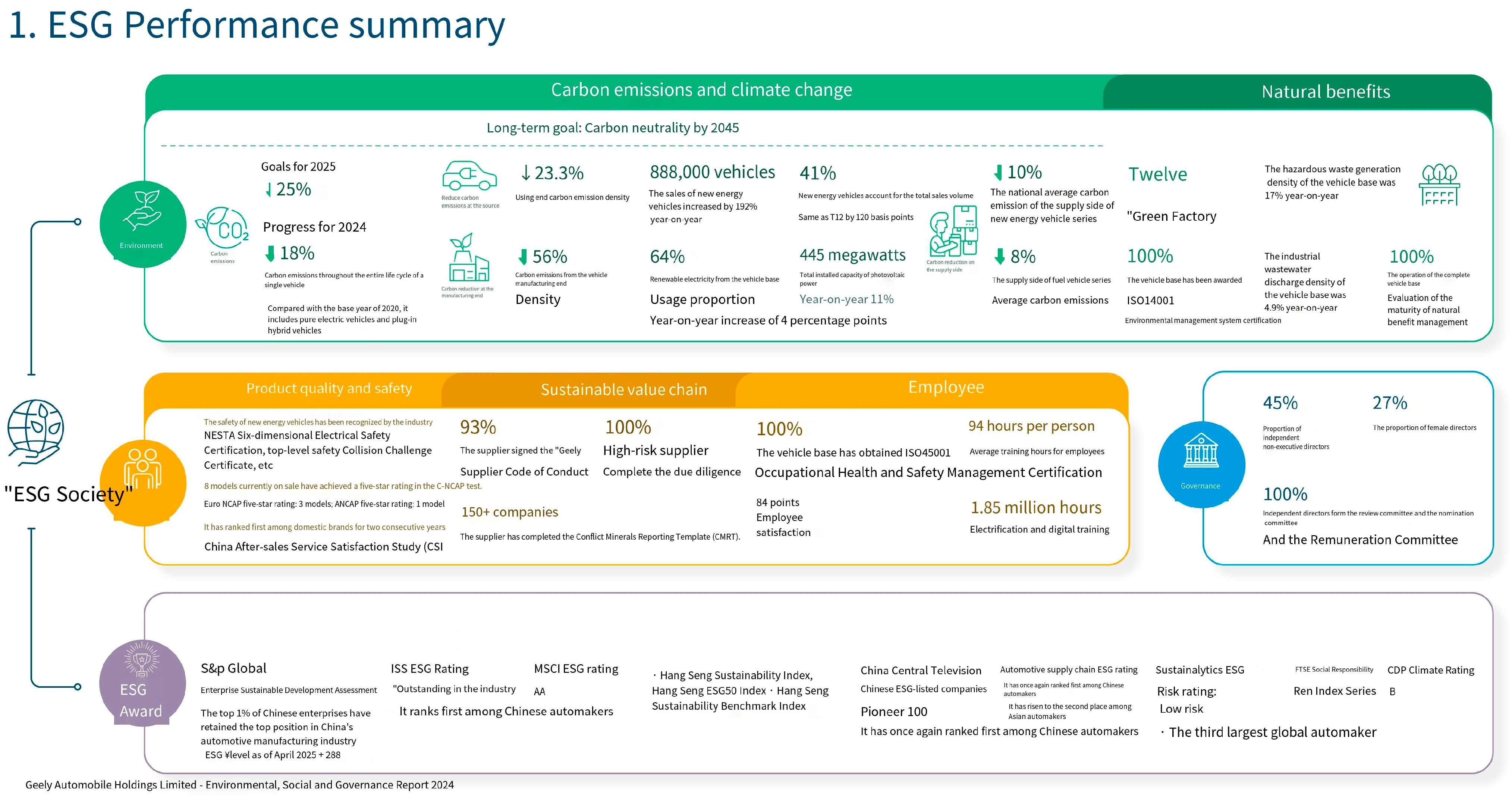

Lignin, a major component of biomass, has been widely studied for the development of formaldehyde-free wood adhesives due to its aromatic structure and abundant content. A pioneering study by Prof. Shuai Li’s team [20] at Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University has successfully developed an uncondensed lignin-based adhesive, which is made from highly active lignin extracted from biomass resources, such as wood and straw, and its gluing mechanism is shown in Figure 2. This innovative approach overcomes the limitations of traditional lignin-based adhesives, such as complex preparation process, high cost and poor performance, to form a simple, effective and low-cost preparation method. The developed adhesive has excellent performance in the hot pressing temperature range (100 to 190 °C), and is characterized by green, simple process, excellent performance and low cost, which has the potential to replace traditional petroleum-based wood adhesives. Figure 2d shows optical microscopy images of glue lines at different hot-pressing temperatures. At 100 °C, the glue line is uneven and porous, with obvious gaps between the adhesive and wood fibers. As the temperature rises to 150 °C, the glue line becomes denser, and the interface with wood is more closely combined. At 190 °C, the glue line is thin and uniform, with no visible pores, indicating that sufficient cross-linking of the lignin adhesive at high temperatures forms a stable bonding interface. Figure 2e presents scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) microscopy images of the glue line at 190 °C. The SEM image shows that the adhesive fully penetrates the wood fiber gaps, forming mechanical interlocking; the FTIR image (1597 cm−1, characteristic absorption peak of lignin) confirms uniform distribution of the adhesive in the glue line, with no local aggregation. From the perspective of policy and governance, the high-value utilization of lignin adhesive raw materials (e.g., straw) directly fits the policy direction of “use to promote the ban” in the Summary of the Reply to Recommendation No. 0278 of the Third Session of the Fourteenth National People’s Congress (Nong’anbao [2025] No. 354). The local level can provide a stable and low-cost supply of raw materials for the industrialization of lignin adhesives through the establishment of a perfect straw collection, storage and transportation system, and realize the synergy between environmental management and industrial development. Further innovations in the utilization of lignin were proposed by Ortner et al. [21], who developed a lignin–carbonate prepolymer as a formaldehyde-free wood adhesive. This adhesive performed well in the Automated Bond Evaluation System (ABES) test, with a maximum tensile shear strength of about 6.3 N·mm−2 at 180 °C for 30 min, which is comparable to the industrial phenolic resin (PF) reference value (5.9–7 N·mm−2). Despite their excellent mold resistance and compatibility with agricultural waste resources, lignin-based adhesives face challenges such as uneven reactivity of raw material lignin (due to differences in biomass sources and extraction methods) and high energy consumption in the hot-pressing process (100–190 °C). These factors increase production costs and limit standardized large-scale production [22].

Figure 2.

(a) Yields of resultant aromatic monomers from hydrogenolysis of FPLs before (25 °C) and after hot pressing. The H shown in (a,d) indicates the addition of sulfuric acid as a crosslinking catalyst to lignin adhesives. (b,c) Side-chain (b) and aromatic (c) regions in heteronuclear single-quantum coherence spectra of FPL before and after hot pressing at 190 °C (δ, chemical shift; the chemical structure in the left panel of c represents an acetal-protected lignin monomeric unit). (d) Optical microscopy images of the glue lines in the plywood products prepared at different hot-pressing temperatures. (e) Scanning electron microscopy (left) and Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) microscopy (right) images of the glue-line region in the plywood prepared at 190 °C (the FTIR image was recorded at 1597 cm−1, a characteristic absorption peak of lignin [20].

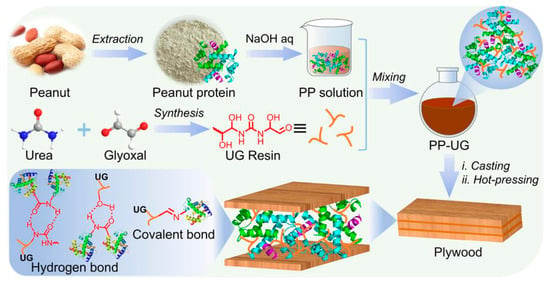

In addition to lignin, various other biomass resources have been successfully used to develop formaldehyde-free adhesives. The research on protein-based adhesives has also made great progress. Deng et al. [23] constructed an environmentally friendly and water-resistant peanut protein wood adhesive by means of various cross-linking strategies. The aflatoxin content of peanut meal often exceeds regulatory standards, leading to its classification as waste. China produces about 4 million tons of peanut meal annually with high protein content, which is an excellent raw material for vegetable protein adhesives [24]. They innovatively proposed the use of glycolaldehyde–urea resin prepolymer and peanut protein to construct a multiple cross-linking network structure, which significantly improves the adhesive bonding performance and water resistance of the adhesive, and the experimental mechanism is shown in Figure 3. The PP-UG composite adhesive forms a multiple cross-linking network through two key interactions. (1) Covalent cross-linking: The glycolaldehyde-urea resin prepolymer (UG) generates active methylol groups, which react with amino and hydroxyl groups in peanut protein (PP) to form methylene bridges, enhancing the structural stability of the adhesive. (2) Hydrogen bonding: The oxygen and nitrogen atoms in the UG resin form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups in peanut protein and wood fibers, improving interface compatibility. This dual cross-linking structure significantly reduces the hydrophilicity of the adhesive (water absorption rate decreased by 42% compared to pure peanut protein adhesive) and enhances bonding strength, with the wet bonding strength reaching 1.115 MPa, meeting the requirements of wood-based panel applications. This method not only solves the formaldehyde release problem of traditional adhesives, but also creates a high-value utilization pathway for peanut meal. The promotion of this technology can be closely integrated with the deep processing policy for agricultural products in the rural revitalization strategy. For example, in peanut producing areas, local governments can guide the establishment of a “planting-oil extraction-adhesive production” industrial chain to promote the development of “one county, one industry”, and realize agricultural efficiency and farmers’ income. Peanut protein adhesives achieve high-value utilization of agricultural waste, but their production is restricted by regional raw material distribution: peanut meal is mainly concentrated in specific producing areas, leading to high transportation costs for cross-regional production. Additionally, the cross-linking agent used in the preparation process increases material costs, and the adhesive’s storage stability (susceptible to microbial degradation) further hinders large-scale promotion [10].

Figure 3.

Schematic diagram illustrating the preparation process of the PP-UG composite adhesive and depicting the various potential interactions within the adhesive system [23].

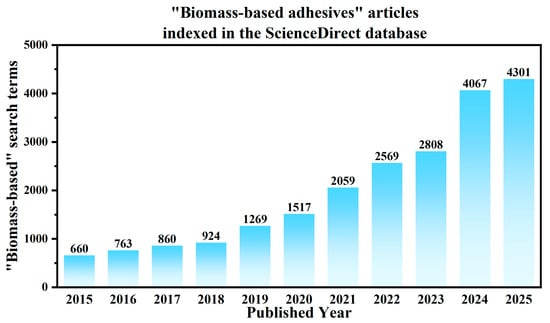

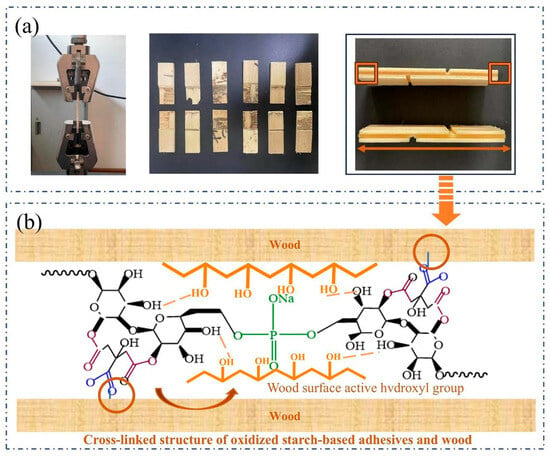

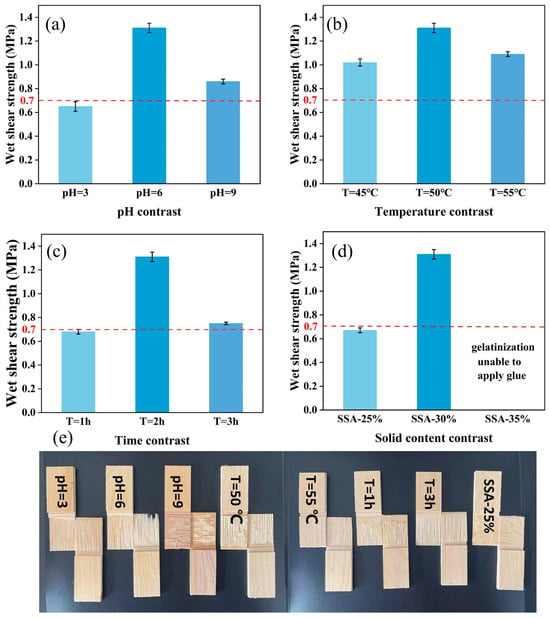

Starch-based adhesives are also a major hot spot in research. Shen Jun et al. [25] oxidized natural starch by sodium sulfate to obtain oxidized starch, and the oxidized starch adhesive (SSA-15%) was crosslinked with PVA, as shown in Figure 4. Figure 4a shows that the physical drawings of pure starch adhesive SSA-15-30% and oxidized starch adhesive SSA-5-30% after 3 h of boiling water, and the specimen of natural starch adhesive absorbed water and swelled, and basically had cracked, and even the adhesive layer separated, while the specimen of oxidized starch adhesive did not disconnect, and still had a very good bonding performance. Figure 4b illustrates the gluing mechanism of oxidized starch adhesives. The oxidized starch generates carboxyl groups through sodium sulfate oxidation, which form ester bonds with hydroxyl groups on the wood surface. Meanwhile, cross-linking with PVA forms a three-dimensional network structure, enhancing the bonding force and water resistance of the adhesive. The prepared oxidized starch adhesive (SSA-15%) had dry and wet shear strengths of up to 2.95 MPa and 1.31 MPa, which were 163% and 120% higher than that of the natural starch adhesive, respectively, improving the product’s mechanical properties, as shown in Figure 5. Oxidized starch adhesives have improved mechanical properties, but their water resistance (wet bonding strength 1.31 MPa) is still lower than that of traditional petroleum-based adhesives. Moreover, starch raw materials are prone to price fluctuations affected by agricultural production cycles, resulting in unstable production costs and making enterprises hesitant to invest in large-scale production lines [26].

Figure 4.

(a) Comparison of oxidized starch adhesive specimens. (b) Diagram of oxidized starch adhesive gluing mechanism [25].

Figure 5.

Mechanical strength comparison [25]. (a) Wet strength of plywood under different pH conditions; (b) Wet strength of plywood under different temperature condition; (c) Wet strength of plywood at different chemical cross-linking times; (d) Wet strength of plywood at different solid contents; (e) Wood failure rate of plywood after wet bonding strength tests.

As for chitosan-based adhesives, such as HM-CS@BN, chitosan’s amino and hydroxyl groups to form hydrogen bonds and covalent cross-links with wood surface hydroxyl groups were utilized, achieving a dry bonding strength of 2.27 MPa and wet bonding strength of 1.05 MPa. Their prominent advantage is high fire resistance, which meets the safety requirements of special scenarios such as interior decoration. However, chitosan raw materials are mainly derived from crustacean shells, with limited annual output and high purification costs, resulting in high adhesive prices (about 3–5 times that of starch-based adhesives). Additionally, chitosan’s poor solubility in neutral environments requires the addition of organic solvents in the preparation process, increasing environmental pressure and restricting industrial application [19].

2.2. Evaluation of Ecological Benefits and Environmental Impacts

The development of formaldehyde-free adhesives has led to significant ecological benefits. Firstly, the impact on life and health is significantly reduced. Traditional phenolic and urea–formaldehyde resin adhesives continuously release formaldehyde during production and use, which has been classified as a class 1 carcinogen by the World Health Organization, and long-term exposure may cause respiratory diseases, allergic reactions, and even increase the risk of leukemia and cancer [27,28]. Formaldehyde-free adhesives eliminate the production of formaldehyde from the source, and they will not release formaldehyde and other toxic volatile organic compounds (VOCs) to the indoor and outdoor environment during the production, storage, transportation, and use cycle after being applied to various types of panels (e.g., synthetic panels, furniture panels), thus effectively improving the quality of indoor air and decreasing the health threat that human beings face due to prolonged exposure to formaldehyde, especially for children, the elderly, and pregnant women who are sensitive to formaldehyde. It is of great significance for the health protection of sensitive groups such as children, the elderly and pregnant women [29,30].

Secondly, it also plays a positive role in resource recycling. As a large agricultural country, China produces abundant plant protein meals every year, which, if not effectively utilized, not only cause waste of resources, but also may cause environmental problems due to accumulation and storage [31]. Formaldehyde-free adhesive through the high-value transformation and utilization of these renewable biomass resources, to build a “agricultural waste—industrial raw materials—green products,” the circular economy chain, reducing the dependence on non-renewable petrochemical resources, but also reduces the environmental load in the process of agricultural waste disposal [32].

In addition, the production process level also shows significant green characteristics. The preparation process of many formaldehyde-free adhesives is gentler than that of traditional adhesives, and the reaction temperature can be generally reduced by 20–30 °C, with a consequent decrease in energy consumption of about 15–25%. The life cycle carbon emission of biomass adhesives is 1.2–1.8 tons of CO2 per ton, which is 60–70% lower than that of urea–formaldehyde resin adhesives (3.5–4.2 tons of CO2 per ton). VOC emissions during production are less than 50 mg/m3, which is 85% lower than the national standard limit for traditional adhesives (300 mg/m3). At the same time, some formaldehyde-free adhesives in the choice of raw materials more inclined to environmentally friendly substances, the production process of wastewater Chemical Oxygen Demand (COD) emissions can be reduced by 40–60%, volatile organic compounds (VOCs) generated by the amount of more than 50%, and some systems can achieve near-zero wastewater discharge [33,34]. From the overall perspective of the product life cycle, formaldehyde-free adhesives made of panels and other end-products in the service life, if you can carry out reasonable recycling and processing, its degradation is also relatively good, biomass-based adhesives made of panels of natural degradation rate than the traditional urea–formaldehyde resin panels to improve the rate of about 35–50%, and effectively alleviate the abandonment of the phase of the “white pollution” and persistent organic matter (POPs). The natural degradation rate of biomass adhesive-based panels reaches 45–60% within 5 years, while traditional urea-formaldehyde resin panels have a degradation rate of only 10–15%, significantly reducing environmental burden. The natural degradation rate of biomass-based adhesives is about 35–50% higher than that of traditional urea–formaldehyde resin sheets, which effectively alleviates the problems of “white pollution” and accumulation of persistent organic compounds at the disposal stage, and further demonstrates the environmentally friendly characteristics of the whole life cycle [35,36].

3. Ecological Civilization Policy Framework and Industrial Transformation

3.1. Overview of Ecological Civilization Policy Framework

Globally, the ecological and environmental crises are worsening, and issues such as climate change, loss of biodiversity, and resource depletion have become common challenges for mankind. This mega-trend has prompted countries to re-examine their development models and seek more sustainable growth paths. At the same time, China, as the world’s largest developing country, also deeply recognizes the unsustainability of the traditional crude development model and urgently needs to promote economic transformation through policy adjustment [37]. As a result, the intrinsic need for national sustainable development has become the core driver of policy formulation, which is manifested in the great importance attached to green and low-carbon development, efficient resource utilization, and ecological environmental protection. The evolution of China’s environmental policy has gone through a complete course from the germination of ideas to systematic advancement. The early stage of awakening of environmental protection awareness was mainly reflected in the initial cognition of environmental pollution problems, which gave rise to the first environmental protection regulations and policy frameworks, such as the establishment of the basic system of environmental protection in the 1980s. With the development of economy and society, the problem of ecological damage has become increasingly complex, pushing the policy into a deepening stage. Especially after entering the 21st century, the concept of comprehensive ecological civilization construction marked a qualitative leap in policy, the relevant policy system began to systematically integrate into the overall economic and social development, forming a comprehensive policy network covering pollution prevention and control, ecological restoration, green industry and other multi-dimensional.

The current environmental policy system presents multi-level and three-dimensional characteristics: at the level of laws and regulations, the rigid constraint framework has been constructed with the Environmental Protection Law as the overarching principle, supported by special laws such as the Water Pollution Prevention and Control Law and the Air Pollution Prevention and Control Law; and at the level of strategic planning, the five-year plan and long-term vision have been combined to form a target system through the convergence of the national ecological civilization construction outline and the local implementation plan. In terms of incentives and constraints, the innovative use of economic instruments, including financial subsidies for new energy industries, tax incentives for environmental protection enterprises, and daily penalties for environmental violations and other disciplinary measures, forming the policy synergy of “carrot and stick”. This complete institutional design not only clarifies the red line requirement for environmental protection, but also provides sustainable impetus for green development.

To strengthen the grassroot implementation mechanism, the policy framework further emphasizes the role of local governments and community participation. Grassroots governments (e.g., township and village governments) play a key role in environmental enforcement and technology promotion, for example, by organizing community meetings and conducting environmental education activities to promote public participation in the adoption of formaldehyde-free adhesives. Adaptive implementation of policies at the local level allows for the grassroots to adjust national standards according to local resources and needs, e.g., prioritizing the promotion of lignin-based adhesives in agricultural waste-rich areas in line with the rural revitalization strategy [38]. At the same time, grassroot governance actors such as small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and cooperatives have been included in the implementation system to ensure flexibility and effectiveness in policy transfer from the national level downwards and to avoid the problem of “one size fits all”.

3.2. The Guiding Role of Policy on Industrial Transformation

The main direction of the current industrial structure adjustment in China is reflected in the following aspects: firstly, it is necessary to accelerate the promotion of industrial transformation and upgrading, gradually eliminating the traditional industries with high pollution and high energy consumption, and actively promoting the transfer of industries to the direction of the development of green and low-carbon industries, and constructing a modernized green industrial system. Secondly, it is necessary to focus on promoting the green upgrading and transformation project of traditional industries, and improve the environmental friendliness and resource utilization efficiency of traditional industries through the introduction of advanced technology and equipment [39].

In terms of technological innovation orientation, enterprises should be vigorously encouraged to carry out independent research and development and innovation of cleaner production technologies, with a focus on supporting the breakthrough and application of environmental protection technologies such as energy conservation and emission reduction, pollution prevention and control. At the same time, it is necessary to focus on cultivating the field of resource recycling technology, promoting the industrialization and application of waste resource utilization technology, and building a recycling-based industrial system. In this process, policy formulation needs to consider technical feasibility [40]. For example, the current national standards (e.g., GB/T 9846-2015) put forward clear requirements for the strength of man-made boards, which directly affects the selection decision of enterprises on new adhesive technology. Therefore, the inclusion of biomass adhesives that meet the performance standards and are environmentally friendly into the “green technology catalog” and green product certification system is the key to guide the transformation of enterprises. Meanwhile, the existing R&D subsidies are mostly focused on universities and research institutes, with insufficient coverage of the pilot and industrialization stages. It is recommended to optimize the subsidy policy to cover the whole chain from R&D, pilot testing to industrialization, especially to support enterprises to build demonstration production lines in order to reduce the market risk of technology transformation [41].

In terms of market mechanism cultivation, it is necessary to accelerate the establishment and improvement of a national unified carbon emissions trading market system, giving full play to the decisive role of the market in the allocation of carbon emissions resources. In addition, it is necessary to further improve the green product certification and labeling management system, develop a scientific and standardized green product evaluation standard system, guide consumers to choose green and low-carbon products, and promote the formation of a social trend of green consumption [42].

3.3. Challenges of Industrial Transformation

3.3.1. Existing Challenges

The current green technological innovation and industrial transformation are facing severe challenges in many aspects, mainly reflected in the following key dimensions:

At the technological level, there are significant technological bottlenecks. The research and development of core green technology not only faces great technical difficulties, involving material science, energy efficiency, pollution control and other high-tech threshold areas, but also accompanied by high R&D cost investment. Even if technological breakthroughs are achieved, various implementation barriers will be encountered in the subsequent transformation and practical application of technological achievements, including problems of process adaptation and equipment renewal.

Financial pressure is another major constraint on the green transformation of enterprises. Enterprises implementing green transformation and sustainable development strategies need to invest a large amount of upfront capital, including equipment acquisition, technology introduction, and personnel training. However, the reality is that enterprises have very limited access to green financing channels, and the existing financial support system and policy support is obviously insufficient to meet the financial needs of enterprise transformation.

The same deep-seated difficulties exist in terms of concepts and management. Many enterprises have long formed the traditional development concept, and the “heavy economic benefits light environmental impact” mindset is difficult to change in a short period of time. At the same time, there is a general lack of a complete green management system within the enterprise, and there are obvious system deficiencies and management loopholes in the implementation of environmental standards, carbon emission management, and green supply chain construction. From the perspective of governance structure, the phenomenon of difficult-to-implement policies is widespread, which is manifested in the following: the implementation of environmental standards in different regions varies, and local protectionism exists in some regions; small and medium-sized enterprises are in a disadvantageous position in obtaining policy information and applying for financial support due to their limited capacity; the public’s and consumer’s cognition and acceptance of formaldehyde-free products still need to be improved; and there is insufficient synergy among the departments of agriculture, environmental protection and industry, leading to the dispersion of policy resources, and the lack of coordination between them. Insufficient synergy between agriculture, environmental protection, industry and other sectors has led to the dispersal of policy resources, affecting the efficiency of implementation. These intertwined difficulties together constitute the main obstacles to green development, and require synergy among government, enterprises and society in order to effectively break through.

3.3.2. Transformation Case Analysis of Classic Industries

At present, China’s energy industry is in a critical period of profound change, and is gradually transforming from the traditional coal-based energy structure to a diversified and clean energy system. This transformation process involves solar photovoltaic power generation, wind power generation, hydropower and other renewable energy development and utilization, aiming to build a cleaner, low-carbon, safe and efficient modern energy system. Taking a large coal enterprise as an example, the enterprise actively responds to the national energy transformation strategy, and gradually expands to the new energy field through technological innovation and industrial upgrading, realizing the successful transformation from a traditional energy supplier to a comprehensive energy service provider [43].

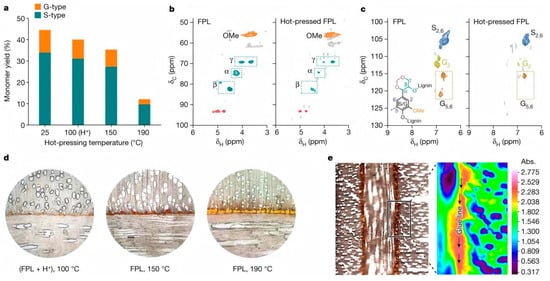

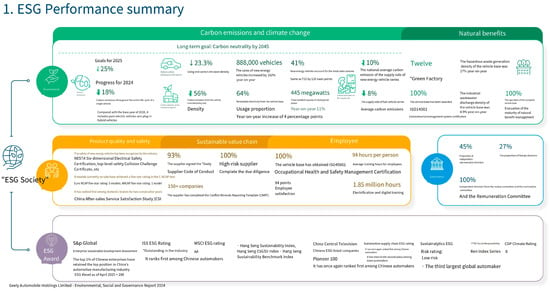

In the field of manufacturing, the integration and development of intelligent manufacturing and green manufacturing have become an important direction of industrial upgrading. Through the introduction of new-generation information technology such as industrial Internet and big data analysis, manufacturing enterprises are realizing the digitalization, networking and intelligence of the production process. At the same time, the implementation of the green manufacturing concept has prompted enterprises to adopt more environmentally friendly production processes and materials. Carbon emission density, defined as the carbon dioxide equivalent emissions generated per unit of economic output, per unit of product output or per unit of industrial added value, is a core quantitative indicator to evaluate the low-carbon level and green development efficiency of manufacturing enterprises. It directly reflects the balance between production scale, economic benefits and carbon reduction effects, and has become an important reference for industrial green transformation assessment. Geely Automobile Group has constructed a full-life-cycle green management system covering design, production, and recycling by deeply integrating intelligent manufacturing and green manufacturing. According to its Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) Report 2024, Geely has realized an increase in the production efficiency of key processes to 98% and a one-time vehicle delivery pass rate of 99% in its Xi’an Super Intelligent Blacklight Factory through the application of industrial internet and AI quality control, as shown in Figure 6. In terms of environmentally friendly materials and processes, Geely has comprehensively promoted the use of water-based coatings and bio-based materials, which has enabled the total VOC emissions from its paint shop to drop by 35% compared with the base year, and the emission concentration has continued to outperform the national standard. Meanwhile, in terms of resource recycling, Geely has established a battery laddering utilization and recycling system that has achieved a nickel—cobalt–manganese recycling rate of more than 99% on a sustained basis, and is committed to improving the economics of lithium recycling technology, which has set a model for the green recycling development of the manufacturing industry [44].

Figure 6.

Geely Automobile Holdings Limited Environmental, Social and Governance (ESG) Report 2024 Performance Summary [45,46].

In the home manufacturing industry, Sofia, a well-known customized home furnishing enterprise, has successfully realized the green upgrading and market value enhancement of its products through the large-scale adoption of Kang Pure Board (no aldehyde-added board), which is based on soy protein adhesive/lignin adhesive and other substrates. According to its “2024 Annual Social Responsibility Report” [47], the measured formaldehyde emission of Kangpure Board is less than 0.020 mg/m3, which is better than the highest national standard ENF level limit, and it also excels in key physical properties such as static bending strength and water absorption and expansion rate, ensuring a balance between health and practicality. An actual view of interior decoration using Kangpure Board is presented in Figure 7. This case shows that the strategic choice of the downstream head manufacturer not only meets the consumer demand for healthy homes, but also effectively pulls the upstream biomass adhesive and formaldehyde-free sheet capacity expansion and technology iteration, forming a market-driven green transition mechanism. To further promote the industrialization of formaldehyde-free biomass adhesives, a series of policy tools have been formed at the grassroots level to provide systematic support, covering financial incentives, standard certification, and public promotion, as detailed in Table 2.

Figure 7.

Actual view of Sofia Con Pure Plate decoration [48].

Table 2.

Policy tools to support the development and adoption of formaldehyde-free adhesives.

4. Socio-Economic Barriers and Comprehensive Policy Recommendations

The industrialization and promotion of formaldehyde-free biomass adhesives is not only a technology substitution process, but also a profound socio-economic system change. Its success relies on the precise identification of deep-seated barriers in the diffusion process and the construction of a matching systematic policy framework with multi-level synergies [7]. This section will first analyze the key socio-economic barriers, and then propose a comprehensive policy response that integrates macro-system, meso-industry and micro-governance.

4.1. Analysis of Socio-Economic Barriers and Development Bottlenecks

The promotion of formaldehyde-free biomass adhesives faces the following four types of intertwined and overlapping socio-economic barriers.

4.1.1. Regional and Industrial Development Contradictions

China’s regional development presents obvious gradient difference characteristics, eastern coastal areas with location advantages, and first opportunity to form a more perfect industrial system and economic ecology, while in the central and western regions, due to the lack of historical accumulation, infrastructure is relatively weak and other reasons, the level of development is relatively lagging behind, this regional development imbalance phenomenon in the total economic output, scientific and technological innovation capacity, public service level and other dimensions are particularly This phenomenon of uneven regional development is particularly prominent in many dimensions such as economic aggregate, scientific and technological innovation capacity, and public service level [49]. In terms of industrial transformation and upgrading, traditional manufacturing industries are facing technical constraints such as difficulties in core technology breakthroughs and huge investment in equipment upgrading, as well as financial pressures such as insufficient special funds for transformation and upgrading and poor financing channels; at the same time, the development of strategic emerging industries is also experiencing a long cultivation cycle of market demand, and insufficient reserves of high-end professionals and other bottlenecks, which hinders the process of conversion of old and new kinetic energy. Deeper industrial structure optimization and upgrading face systemic challenges, including the cost pressure brought by the continuous increase in the prices of production factors such as labor and land, the inefficiency of R&D inputs and outputs caused by the imperfect innovation system, and the structural contradiction caused by the lack of innovation power due to the poor mechanism of industry–university–research synergy, which are interwoven with each other and form the multiple obstacles restricting the high-quality development of the economy.

4.1.2. Short Board of Innovation System and Human Resources

Currently, the field of scientific and technological innovation is facing three outstanding development bottlenecks: first, from the perspective of R&D investment and result transformation, scientific and technological innovation investment has been in a state of insufficiency for a long time, and the proportion of R&D expenditure in GDP is lower than the international advanced level, while there is a significant short board in scientific and technological results transformation, and there is an obvious fault between laboratory results and industrialized application. At the same time, there are significant shortcomings in the transformation of scientific and technological achievements, and there is an obvious gap between laboratory achievements and industrialized applications, which leads to the overall low rate of transformation of R&D achievements, and scientific research achievements are difficult to be effectively transformed into real productivity. Secondly, in terms of talent support, the problem of structural shortage of high-end talents is becoming increasingly prominent, especially in the strategic emerging industries and key core technology areas of the supply of high-level talent is insufficient, while the existing talent training system and the rapid changes in the industry demand there is an obvious disconnect between the phenomenon, resulting in the targeting of talent cultivation and adaptability is insufficient [50]. In addition, due to the development environment, salary and treatment, scientific research conditions and other factors, the attraction and retention rate of talents show a double low trend, making it difficult to form a sustainable talent support system. Finally, in terms of innovation ecological construction, the operation of the industry-university-research collaborative innovation mechanism is not smooth, and there is a lack of effective collaborative cooperation platforms and benefit-sharing mechanisms between various types of innovation subjects, which leads to the dispersion of innovation resources and the fragmentation of the innovation chain. At the same time, the development of the market for technology, talent, capital and other innovation factors is still imperfect, and there are many institutional barriers to the flow of factors, which seriously restricts the efficient allocation of innovation resources and the overall enhancement of innovation efficiency, and affects the overall operational efficiency and quality of the innovation system [51].

4.1.3. Governance Structure and Policy Implementation Barriers

This is the core barrier examined from the perspective of grassroots governance. First, lax enforcement of environmental protection standards and local protectionism coexist, and some regions are lax in regulating traditional adhesives in order to protect tax revenues and employment, resulting in unfair competition for green technologies. Secondly, SMEs lack the ability to transform, they lack the ability and resources to access policy information, apply for green credit and carry out technological transformation. Thirdly, there is insufficient sectoral synergy, as the policy objectives and resources between the agricultural sector (raw materials), the industry and information sector (industry) and the environmental protection sector (regulation) are not effectively integrated, resulting in insufficient policy synergy. Finally, low public awareness and market acceptance, consumers have limited knowledge of the health benefits of formaldehyde-free products and low acceptance of the green premium, making it difficult to form an effective market pull [52].

4.1.4. Distribution Mechanism and Sustainable Development Challenges

At present, China’s economic and social development is facing multiple challenges and structural contradictions. First of all, in the field of income distribution, the income gap between different groups shows a continuing trend of widening, and the gap between high- and low-income groups is deepening, while the current social security system is still insufficient in terms of coverage and protection, and it is difficult to effectively play the role of income redistribution adjustment. Secondly, in terms of resources and the environment, the contradiction between the traditional exuberant development mode and ecological environmental protection is continuously aggravated, the intensity of resource consumption remains high, the environmental carrying capacity continues to be under pressure, and the green low-carbon transformation faces a severe test [53]. Again, in the field of public services, the uneven distribution of high-quality resources is prominent. For education, health care, and other basic public services in urban and rural areas, there is a significant gap between the regions, and some groups of people’s basic livelihood protection still needs to be strengthened and improved. The existence of these structural problems not only restricts high-quality economic development, but also affects the realization of social justice.

4.2. Systemic Policy Optimization Suggestions

In response to the above obstacles, this paper proposes a synergistic “technology-policy-governance” framework covering the macro, meso and micro levels to guide and accelerate industrial transformation. The framework integrates the central government’s strategic plan to develop new productivity and strengthen the construction of ecological civilization, and aims to transform green technology breakthroughs into real industrial competitiveness and people’s well-being.

4.2.1. Macro-Level: Building a Cross-Sectoral Synergistic and Incentive-Compatible Institutional Environment

The macro-level focuses on top-level design, breaking down sectoral and regional barriers, and creating a fair and efficient market environment and institutional safeguards for the balanced development of green technological innovation and industry.

- (1)

- Strengthen strategic planning and cross-sectoral synergistic mechanisms

Implement the top-level design of ecological civilization construction. According to the spirit of the Fourth Plenary Session of the 12th CPC Central Committee, the research, development and application of formaldehyde-free biomass adhesive will be incorporated into the overall layout of the national ecological civilization construction and the key special projects of the Tenth Five-Year Plan. Establish an inter-ministerial joint conference system for the development of bio-based green materials, which is organized by the National Development and Reform Commission, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment, the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development, the Ministry of Science and Technology and other departments, to coordinate the supply of raw materials, technology research and development, industrial application and environmental supervision, so as to form a synergistic policy and to avoid the problem of “multiple governmental departments” government out of multiple departments”.

Implement regional differentiated development strategy. Docking national regional major strategies, the development of “biomass adhesive industry regional development guidelines”. In the central and western regions, the use of rural revitalization funds and industrial transfer funds, focusing on supporting the construction of straw and other agricultural waste as raw materials for the adhesive industry clusters, to create a “planting—storage—transformation—application” integrated circular economy model. In the eastern coastal areas, encourage the use of advanced manufacturing base and market demand, the development of high-performance biomass adhesive R&D and high-end equipment manufacturing, the formation of “R&D in the East, application in the West” synergistic pattern [54].

- (2)

- Optimize innovation incentives and factor allocation policy

Stimulate the new quality productivity momentum, such as guiding enterprises to set up a “green new quality productivity cultivation fund”, focusing on supporting the whole chain of biomass adhesives from the laboratory pilot to industrialized scale production research. Reform the management of scientific research funds, the implementation of the “list of commanders” system, and encourage enterprises to take the lead in the formation of innovation consortia. The implementation of R&D costs plus deduction, environmental protection special equipment investment tax credits and other policies, and the first (sets) of major technical equipment applications to provide insurance compensation.

Build a green financial support system. Guiding banking financial institutions to expand the scale of green credit, and developing special products such as “green technology conversion loans”. Encourage local governments and leading enterprises to set up green industry guidance funds to attract social capital investment. Explore the formaldehyde-free adhesive products into the green power trading and carbon emissions trading system, so that its environmental benefits into economic gains [55].

4.2.2. Meso-Level: Cultivate Deeply Integrated and Resilient Industrial Clusters and Innovation Ecology

The meso-level focuses on the construction of industrial ecology, and further improves the resilience and security of the industrial chain supply chain by “building clusters, promoting integration and strengthening standards”.

- (1)

- Promote industrial clustering and digital transformation.

Create a modernized industrial chain supply chain. In agricultural resource-rich areas (e.g., Henan, Shandong) and advanced manufacturing bases (e.g., Yangtze River Delta, Pearl River Delta), plan and build a number of provincial-level “formaldehyde-free biomass adhesive eco-industrial demonstration parks”. Promote the coupling and symbiosis among enterprises in the park, and realize the sharing and recycling of raw materials, energy and infrastructure.

Empowering the transformation of industrial intelligence and greening. Combined with the deployment of intelligent manufacturing and green manufacturing in the Tenth Five-Year Plan, encourage enterprises to apply industrial Internet, big data and artificial intelligence technologies to build “digital twin factories”, optimize production processes, and achieve precise carbon control and emission reduction. Support industry associations to build “green supply chain management platforms”, and promote downstream household and building materials leading enterprises to prioritize the procurement of certified formaldehyde-free panels to form a market pull.

- (2)

- Build an innovation community for the deep integration of industry, academia, research and financial mediation.

Establishment of “biomass adhesive industry technology innovation strategy alliance”. The alliance is guided by the government, industry-leading enterprises, top research institutes and universities jointly initiated, responsible for condensing industry common technical problems, organizing joint research and development of group standards. The establishment of a “patent pool” reduces the transaction costs of innovation and cooperation.

Strengthen scientific and technological services and talent gathering, and build a benign ecology of “attracting talents through platforms and retaining talents through services”. In key industrial clusters, the core is to build a national innovation platform integrating technology research and development, results transformation and industrialization services, providing one-stop services for enterprises and reducing R&D costs by sharing equipment and data [56]. It focuses on strengthening the construction of pilot bases, solving the interface problems between laboratory results and large-scale production, and accelerating technology iteration. The implementation of precise talent program, promote the platform and leading enterprises to set up “industry professor” positions, to attract college scholars with technology stationed; at the same time, linked to vocational colleges and universities, to carry out “artisan star” and other order cultivation, forging technical and skilled personnel. Through the “platform + talent” mode, the deep integration of innovation elements and talent elements is realized, forming a virtuous cycle of “converging talents with platforms and driving innovation with talents”, providing core kinetic energy for industrial upgrading [57,58].

4.2.3. Micro-Level: Innovating Grass-Roots Governance Mechanisms for Joint Construction and Shared Benefits

The micro-level focuses on the “last kilometer” of policy implementation, and by stimulating the vitality of the grassroots, it ensures that the fruits of green transformation will benefit the wider public, and realizes the unity of environmental benefits, economic benefits and social benefits.

- (1)

- Deepening grass-roots governance and benefit linkage mechanisms

Promote the “government (collective) leadership + cooperatives + enterprises” model. At the township level, the village collective organization led the establishment of straw collection, storage and transportation professional cooperatives, and adhesive production enterprises to establish a long-term stable order relationship. Explore the reform of “resources into assets, capital into shares, farmers into shareholders”, allowing farmers to share in straw resources, sharing the value-added benefits of the industrial chain. This move directly echoes the strategy of rural revitalization and promotes the common prosperity of farmers and rural areas.

Empowering small and medium-sized enterprises and new business entities. The grassroots government has set up a “Green Transformation Service Window” to provide SMEs with one-stop policy interpretation, credit guarantee application and guidance on technological transformation. Local tax exemptions or special incentives are given to SMEs that actively adopt green technologies and materials.

- (2)

- Promoting public participation and green consumption trends

Carry out the “Green Living Action for All”. Publicize the health benefits of formaldehyde-free home environments and incorporate them into theme activities such as the National Ecology Day. Encourage communities, schools and shopping malls to carry out formaldehyde-free product experience and knowledge popularization. Support grassroots environmental organizations and volunteers to participate in monitoring.

Establish a green traceability system for the entire life cycle. Develop a simple and easy-to-use “green home traceability APP” or small program, docking product carbon footprint labeling system, so that consumers can query the type of adhesive, source of raw materials, carbon emission reductions and other information, through the consumer’s “vote with their feet” to force Through the consumer “vote with feet” to force industrial upgrading, forming a virtuous cycle of green consumption pulling green production.

In summary, the key challenges in industrializing biomass adhesives and corresponding policy recommendations are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of main challenges and related policy recommendations for industrialization of biomass adhesive.

5. Conclusions

This paper systematically describes the research progress of formaldehyde-free biomass adhesives, and analyzes it from the perspectives of technology, environment and policy. The results show that the adhesive has significant potential for performance enhancement, health improvement and resource recycling; its diffusion is constrained by multiple barriers such as technical stability, cost and lack of policy synergy; the key to breakthrough lies in the construction [7] of a synergistic framework of technology–policy–governance to facilitate the transformation of laboratory results into industrialized applications. In the future, the following issues need to be studied in depth: how to further optimize the water resistance of adhesives and cost control to enhance market competitiveness; how to design more effective cross-sectoral policies and incentives to promote the broad participation of small and medium-sized enterprises. Continuous exploration of these issues will provide key support for the industry’s green transformation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, X.M.; Validation, K.W.; Formal analysis, X.M.; Investigation, J.X.; Data curation, X.S.; Writing—original draft, K.W.; Writing—review & editing, X.M.; Supervision, W.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barbu, M.C.; Tudor, E.M. State of the art of the Chinese forestry, wood industry and its markets. Wood Mater. Sci. Eng. 2022, 17, 1030–1039. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M.; Shen, P.; Wang, L.; Ma, Q.; Jia, Z.; Hu, C.; Zhang, X. Research progress of eco-friendly plant-derived biomass-based wood adhesives: A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 120093. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, N.R.; Fang, L.; Liu, W.; Kan, H.D.; Zhao, Z.H.; Deng, F.R.; Huang, C.; Zhao, B.; Zeng, X.A.; Sun, Y.X.; et al. Health effects of exposure to indoor formaldehyde in civil buildings: A systematic review and meta-analysis on the literature in the past 40 years. Build. Environ. 2023, 233, 110080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshakhlagh, A.H.; Mohammadzadeh, M.; Manafi, S.S.; Yousefian, F.; Gruszecka-Kosowska, A. Inhalational exposure to formaldehyde, carcinogenic, and non-carcinogenic risk assessment: A systematic review. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 331, 121854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tenorio-Alfonso, A.; Sánchez, M.C.; Franco, J.M. A Review of the Sustainable Approaches in the Production of Bio-based Polyurethanes and Their Applications in the Adhesive Field. J. Polym. Environ. 2020, 28, 749–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvez, I.; Garcia, R.; Koubaa, A.; Landry, V.; Cloutier, A. Recent Advances in Bio-Based Adhesives and Formaldehyde-Free Technologies for Wood-Based Panel Manufacturing. Curr. For. Rep. 2024, 10, 386–400. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Zhang, F.D.; Bian, R.H.; Zeng, G.D.; Li, J.J.; Lyu, Y.; Li, J.Z. Formaldehyde-free biomass adhesive based on industrial alkali lignin with high strength and toughness. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119525. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, Q.; Tan, H.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of glycidyl methacrylate grafted starch adhesive to apply in high-performance and environment-friendly plywood. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 194, 954–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.; Peng, Z.; Li, J.; Li, X.; Jiang, X.; Dong, Y. Unlocking the role of lignin for preparing the lignin-based wood adhesive: A review. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 187, 115388. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Jin, S.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zeng, G.; Li, J.; Shi, S.Q.; Li, J. Bioinspired dual-crosslinking strategy for fabricating soy protein-based adhesives with excellent mechanical strength and antibacterial activity. Compos. Part B Eng. 2022, 240, 109987. [Google Scholar]

- GB/T 9846-2015; Plywood for General Use. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, China National Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Chen, Y.X.; Zhu, H.S.; Gao, F.; Xiong, H.R.; Yang, H.; Xu, Z.X.; Duan, P.G.; Zheng, L.J.; Osman, S.M.; Luque, R. Green wood bio-adhesives from cellulose-derived bamboo powder hydrochars. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 498, 155667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wu, H.; Zhang, J.; Wen, T.; Du, G.; Charrier, B.; Essawy, H.; Pizzi, A.; Wu, J.; Zhou, X.; et al. Soybean protein wood adhesive with enhanced water resistance and low environmental impact through lignin-protein hybridization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 234, 121571. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, Y.; Bian, R.; Yu, Y.; Li, J.; Li, C.; Lyu, Y.; Li, X.; Luo, J.; Li, J. Aminated alkali lignin nanoparticles enabled formaldehyde-free biomass wood adhesive with high strength, toughness, and mildew resistance. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 494, 152914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Y.; Pan, A.; Xu, B.; Zheng, G.; Zhang, X.; Xu, Y. Preparation of a multi-functional soy protein adhesive with toughness, mildew resistance and flame retardancy by constructing multi-bond cooperation. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2025, 142, 104134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S.; Kong, D.; Chen, H.; Gao, Q.; Li, J. Water-resistant and anti-mildew soy protein adhesive with network structures based on reversible boron-oxygen bonds and multiple hydrogen bonds. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, T.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, L.; Guo, H.; Zeng, H.; Xu, K.; Lei, H.; Du, G.; Zhang, L. Development of boiling water resistance starch-based wood adhesive via Schiff base crosslinking and air oxidation strategy. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2024, 698, 134592. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Rao, Y.; Liu, P.; Han, Z.; Xie, F. Facile fabrication of a starch-based wood adhesive showcasing water resistance, flame retardancy, and antibacterial properties via a dual crosslinking strategy. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 282, 137180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, Z.; Huang, Y.; Wang, F.; Liu, L.; Wei, D.; Guo, H.; Chen, Y.; Xie, L.; Zhang, L.; Du, G. Low-temperature curing, flame-retardant and water-resistant modified cellulose-chitosan adhesive based on organic-inorganic hybridization. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 329, 147835. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.X.; Gong, Z.G.; Luo, X.L.; Chen, L.H.; Shuai, L. Bonding wood with uncondensed lignins as adhesives. Nature 2023, 621, 511–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortner, N.; Fliedner, E.; Strüven, J.; Bornholdt, N.; Lange, I.; Ziegler, B.; Lehnen, R. Synthesis and characterization of lignin-carbonate prepolymers as formaldehyde-free wood adhesives. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 236, 121949. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, A.F.; Ashaari, Z.; Lee, S.H.; Md Tahir, P.; Halis, R. Lignin-based copolymer adhesives for composite wood panels—A review. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2019, 95, 102408. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Z.; Du, X.T.; Pizzi, A.; Li, X.H.; Zhang, J.; Xia, Y.; Du, G.B.; Lu, Y.; Deng, S.D. Construction of Eco-Friendly and Water-Resistant Peanut Protein Wood Adhesive through Multiple Cross-Linking Strategies. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 3393–3405. [Google Scholar]

- Qu, Y.; Li, T.; Huang, X.G.; Liang, M.Z.; Qin, J.J.; Guo, Q.; Wang, Q. Developing multifunctional and environmental-friendly hot-pressed peanut meal protein adhesive based on peanut waste. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 471, 144207. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, H.Q.; Yao, W.R.; Liu, G.Y.; Chen, K.; Liu, M.Y.; Sun, C.; Tan, H.Y.; Shen, J.; Zhang, Y.H. A New Strategy for the Preparation of High-Strength Hydrophobic Aldehyde-Free Starch Adhesive. Polym. Adv. Technol. 2024, 35, e70000. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, H.; Kan, Z.; Feng, W.; Chen, Y.; Yao, J.; Wei, D.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Du, G.; Liu, L. Flame retardant modified starch adhesive made by crosslinking with phosphorus containing citrate based polyamines has excellent boiling water resistance. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 366, 123835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Torre, G.; Vitello, T.; Cocchiara, R.A.; Della Rocca, C. Relationship between formaldehyde exposure, respiratory irritant effects and cancers: A review of reviews. Public Health 2023, 218, 186–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshakhlagh, A.H.; Mohammadzadeh, M.; Sicard, P.; Bamel, U. Human exposure to formaldehyde and health risk assessment: A 46-year systematic literature review. Environ. Geochem. Health 2024, 46, 206. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, S.; Chen, X.Q.; Ni, S.Z.; Wang, Z.J.; Fu, Y.J.; Qin, M.H.; Zhang, Y.C. Formaldehyde-Free, High-Bonding Performance, Fully Lignin-Based Adhesive Cross-Linked by Glutaraldehyde. Acs Appl. Polym. Mater. 2025, 7, 859–867. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, C.X.; Xu, C.; Zhai, J.X.; Zhao, C.W.; Ma, Y.H.; Yang, W.T. Low-Cost and Formaldehyde-Free Wood Adhesive Based on Water-Soluble Olefin-Maleamic Acid Copolymers. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2023, 62, 20547–20555. [Google Scholar]

- de Paiva, E.M.; Mattos, A.L.A.; da Silva, G.S.; Canuto, K.M.; Alves, J.L.F.; de Brito, E.S. Valorizing cashew nutshell residue for sustainable lignocellulosic panels using a bio-based phenolic resin as a circular economy solution. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 212, 118379. [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves, D.; Bordado, J.M.; Marques, A.C.; dos Santos, R.G. Non-Formaldehyde, Bio-Based Adhesives for Use in Wood-Based Panel Manufacturing Industry—A Review. Polymers 2021, 13, 4086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arias, A.; González-García, S.; Feijoo, G.; Moreira, M.T. Environmental benefits of soy-based bio-adhesives as an alternative to formaldehyde-based options. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 29781–29794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, R.J.; Zhang, Q.Y.; Wu, D.; Hou, M.H.; Long, L.; Zhou, X.J.; Essawy, H.; Du, G.B.; Pizzi, A.; Xi, X.D. Preparation and analysis of environment-friendly and high- performance cellulose-based wood adhesive. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 304, 140642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.Z.; Chen, G.L.; Zhang, S.F.; Zhang, W.; Wu, H.; Li, C.Z.; Xiao, Z.H. Camellia meal-based formaldehyde-free adhesive with self-crosslinking, and anti-mildew performance. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 176, 114280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.Y.; Liu, T.L.; Yu, S.S.; Meng, Y.; Lu, J.; Cheng, Y.; Wang, H.S. The preparation and performance of a novel lignin-based adhesive without formaldehyde. Ind. Crops Prod. 2020, 153, 112593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Ortega, O.; Dehbi, F.; Nelson, V.; Pillay, R. Towards a Business, Human Rights and the Environment Framework. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.Y. Grassroots governance and social development: Theoretical and comparative legal aspects. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2023, 10, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.Z.; Wei, X.J.; Wei, J.; Gao, X. Industrial Structure Upgrading, Green Total Factor Productivity and Carbon Emissions. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasmoko, S.; Akhtar, M.Z.; Khan, H.u.R.; Sriyanto, S.; Jabor, M.K.; Rashid, A.; Zaman, K. How Do Industrial Ecology, Energy Efficiency, and Waste Recycling Technology (Circular Economy) Fit into China’s Plan to Protect the Environment? Up to Speed. Recycling 2022, 7, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Wu, M.; He, S.; Peng, Z. Digitalization, Green Innovation, and Green Transformation of Energy Enterprises in China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.R.; Feng, T.T.; Kong, J.J.; Cui, M.L.; Xu, M. Grappling with the trade-offs of carbon emission trading and green certificate: Achieving carbon neutrality in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 360, 121101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jermain, D.O.; Pilcher, R.C.; Ren, Z.J.; Berardi, E.J. Coal in the 21st century: Industry transformation and transition justice in the phaseout of coal-as-fuel and the phase-in of coal as multi-asset resource platforms. Energy Clim. Change 2024, 5, 100142. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, Y.; Li, M.; Zhang, J.; Cheol, C.M.; Kim, H.E. Competitiveness Analysis of Geely Automobile Group. Int. J. Adv. Cult. Technol. 2024, 12, 402–408. [Google Scholar]

- Geely Automobile Releases Its 2024 ESG Report: Has Achieved the Top Ranking in Multiple Authoritative Rating Lists, Demonstrating Its Strength and Shaping a New Global ESG Model. Available online: https://www.news.cn/auto/20250428/79d23729d2f44499af1794a0ca3e23d1/c.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- ISO 14001: 2015; Environmental Management Systems—Requirements with Guidance for Use. General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine of the People’s Republic of China, China National Standardization Administration: Beijing, China, 2015.

- Sofia: 2024 Annual Environmental, Social Responsibility and Corporate Governance Report. Available online: https://vip.stock.finance.sina.com.cn/corp/view/vCB_AllBulletinDetail.php?id=11042637 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- A Post-90s Mother Uses KPC boards To Create an Eco-Friendly and Beautiful Home, Where Three Generations Live in Harmony and Joy. Available online: https://suofeiya.com/mcase/3562.html (accessed on 1 July 2025).

- Capello, R.; Cerisola, S. Towards a double bell theory of regional disparities. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2024, 73, 1701–1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miao, P.; Zhang, X.Y.; Zhang, N. The complex impact of China’s science and technology talent policies on key core technologies R&D. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324587. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, Y.; Zhu, J.; Tao, C.Q. The mechanism of technological potential energy driving Industry-University-Research institution collaborative innovation. Int. Entrep. Manag. J. 2021, 17, 1541–1567. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Zhao, K. Navigating the innovation policy dilemma: How subnational governments balance expenditure competition pressures and long-term innovation goals. Heliyon 2024, 10, e34787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Idrees, M.; Majeed, M.T. Income inequality, financial development, and ecological footprint: Fresh evidence from an asymmetric analysis. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 27924–27938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.G. Research Progress on Green Adhesives for Engineered Wood Panels. J. Cent. South Univ. For. Technol. 2024, 44, 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, F.J. Research on Green Finance’s Role in Promoting the Development Path of Roadside Economy Industries: A Case Study of Gansu Province. Transp. Enterp. Manag. 2022, 37, 16–18. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.H.; Zhan, X.Y. Patient Capital, Deep Integration of Industry-Academia-Research, and Corporate Independent Innovation: Empirical Evidence from Technology Achievement Transformation Guidance Funds. Contemp. Econ. Sci. 2025, 47, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z. Research on Challenges and Countermeasures for Deep Integration of Industry-Academia-Research Development. Ind. Technol. Forum 2025, 24, 225–228. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.L.; Yang, Q.L.; Huang, Y.B. Can Industry-Academia-Research Integration Empower High-Quality Economic Development? Empirical Evidence from Micro-Enterprise Innovation. Macroecon. Res. 2025, 106–122. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.