Abstract

This study examines how key organizational resources shape work–life balance (WLB), behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC), and work engagement (WE) among employees in the private sector. Drawing on the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model and the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, we test an integrated framework in which leader support, co-worker support, and family-friendly policies predict WLB and BWLC, which in turn influence work engagement. Data collected from employees in Slovenian private-sector organizations were analyzed using structural equation modelling. The results show that leader support, co-worker support, and family-friendly policies significantly enhance WLB, with leader support demonstrating the strongest effect. BWLC is negatively associated with WLB, confirming that behavioural spillover between domains diminishes employees’ perceived balance. Leader support is the only organizational resource that significantly reduces BWLC, while co-worker support and family-friendly policies show no direct effect. Furthermore, WLB is a strong positive predictor of work engagement, whereas BWLC does not directly predict WE. These findings highlight the importance of work–life balance for understanding the relationship between organizational resources and work engagement, and they underscore the crucial role of leader behaviour in shaping boundary management. The findings should be interpreted within the context of Slovenian private-sector organizations and comparable regulated labour-market settings.

1. Introduction

In contemporary society, individuals frequently encounter challenges in achieving a balance among their various roles and responsibilities. Work–life balance has gained increasing attention among scholars and practitioners since the beginning of the century, with a particularly noticeable rise in interest from 2017. Work–life balance can be defined as the effective integration of, or adaptation to, multiple roles within an individual’s life [1]. This concept predominantly refers to the equilibrium between obligations related to employment and those external to paid work, such as familial responsibilities, with the optimal balance being a subjective assessment by the individual [2]. As articulated by [3], the work–family balance is a framework that supports an individual’s ability to allocate their time and resources effectively between occupational duties and other critical life roles.

The literature distinguishes between two terms that define the concept of achieving equilibrium between work and other life roles: work–life balance and work–family balance [4]. Work–life balance is a construct that encapsulates the efforts of individuals to effectively allocate their time and energy between occupational responsibilities and other significant roles and activities in life, such as family, social interactions, community involvement, spirituality, personal development, and leisure pursuits [3]. In contrast, work–family balance specifically refers to the successful negotiation and fulfilment of role-related expectations that occur between an individual and their role-related partners within both work and family domains [5]. While the two terms are conceptually related, they are not identical; the construct of work–life balance is more comprehensive, encompassing a broader range of life domains compared to the narrower focus of work–family balance [4]. This paper adopts the term work–life balance to specifically examine the interplay between work and non-work roles.

Research in the domain of work–family balance predominantly identifies three distinct types of experiences encountered by individuals when attempting to manage multiple roles. The first of these is work–family conflict, which refers to the tension that arises from the incompatibility or incongruence between the demands of work and other life roles [6]. The second experience is work–family balance satisfaction, which is defined as an individual’s holistic assessment of their effectiveness in balancing work-related responsibilities with other life roles [7]. The third experience, as noted by [8], is work–family enrichment, which refers to the extent to which engagement in one role enhances the quality of life in another role.

In research on the work–life interface, one of the most frequently examined experiences is work–life conflict. It is defined as a form of strain arising from incompatibility or misalignment between the demands of the work role and those of other life roles [9]. This phenomenon occurs when obligations in one domain hinder successful participation in another, leading to stress, lower life satisfaction, and often reduced work engagement. Existing studies indicate that numerous factors influence the emergence and intensity of work–family conflict, among which organizational support plays a particularly important role [10,11,12,13,14]. The literature distinguishes three primary forms of conflict: time-based conflict, which occurs when time demands in one role reduce availability for the other; strain-based conflict, in which stress, fatigue, or emotional exhaustion from one domain interferes with functioning in the other; and behaviour-based conflict, which arises from incompatible behavioural expectations between roles [15,16].

Behavioural work–life conflict represents a specific and often the most disruptive dimension of this phenomenon, as it involves the transfer of behavioural patterns from one domain into another, resulting in inappropriate behaviour in the family or work context. As outlined above, behaviour-based conflict represents one of the three established forms of work–life conflict, alongside time-based and strain-based conflict, and refers to incompatibilities in behavioural expectations across work and non-work roles. Specifically, behavioural work–life conflict arises when behavioural scripts, norms, and expectations that are effective and rewarded in one role domain—such as authoritarianism, high control, emotional restraint, or strong task orientation—are inappropriately transferred into another domain, where they become dysfunctional. Unlike time-based or strain-based conflict, which primarily reflect temporal pressures or emotional overload, behavioural conflict is defined by the observable misalignment between role-incongruent behaviours and contextual expectations. Importantly, the behavioural nature of this conflict does not imply the absence of emotional or cognitive components; rather, it denotes the primary locus at which incompatibility manifests—namely, in role-incongruent behaviour. Prior research indicates that such behavioural spillover has particularly disruptive effects on interpersonal relationships, role adjustment, and overall well-being, underscoring the theoretical and practical relevance of behavioural work–life conflict [9].

Behavioural conflict typically arises when work demands impair one’s ability to adapt to family roles, contributing to resource loss, emotional exhaustion, and poorer interaction quality in the home domain. Research shows that high workloads, insufficient supervisory or co-worker support, and unfavourable working conditions all increase the likelihood of behavioural conflict [17,18]. While conflict is often discussed as a multidimensional phenomenon, it is important to distinguish work–life conflict from other forms of conflict studied in organizational research. While some forms of conflict, such as task-related conflict, may under certain conditions foster creativity and performance, work–life conflict is conceptually distinct. By definition, work–life conflict reflects incompatible role demands across life domains and constitutes a strain-based process that is consistently associated with reduced well-being and impaired functioning. For this reason, our study focuses specifically on behavioural conflict as a key aspect of the work–life interface that reflects how work-related demands intrude into private life [19,20].

Lower levels of behavioural conflict substantially contribute to more effective work–life balance, as employees are better able to maintain clear boundaries between domains and adjust their behaviour according to contextual expectations. Reducing behavioural spillover minimizes the loss of psychological and social resources and, consistent with the Conservation of Resources theory [21,22], supports improved subjective balance and a greater sense of control. A stable work–life balance is associated with higher work engagement, as employees experience less stress, more support, and greater alignment between expectations and their behavioural responses [1,23]. Evidence further demonstrates that organizational support reduces work–life conflict and is associated with higher levels of work engagement [14,18]. Lower behavioural conflict between work and private life is therefore associated with greater resource availability, more effective role management, and higher levels of energy, dedication, and motivation at work.

In addition to the challenges surrounding work–life balance, organizations are also confronted with widespread disengagement among employees. Data from a 2016 Gallup survey covering 155 countries revealed that only 15% of employees were engaged in their work, with 67% unengaged and 18% actively disengaged. By contrast, the most successful companies globally achieve employee engagement rates of approximately 70% [24]. It is increasingly recognized that contemporary organizations require employees who are energetic, committed, and engaged, as these employees tend to demonstrate higher levels of productivity [25,26].

Work engagement is conceptualized as a positive, work-related psychological state comprising three core dimensions: vigour, dedication, and absorption [27,28]. Vigour reflects high levels of energy and mental resilience during work tasks, while dedication denotes a strong sense of involvement in one’s work, accompanied by feelings of significance, enthusiasm, and challenge. Absorption refers to a state of deep immersion in work, characterized by high concentration and minimal error [27,29]. Work engagement is therefore regarded as a relatively stable psychological state, involving the simultaneous investment of personal energy and resources into work tasks and achievement [30].

The concept of work engagement has been extensively studied, with the literature identifying it as a critical outcome of a healthy work environment. This underscores the importance for organizations to understand and address the needs of their employees, thereby fostering work engagement, which in turn enhances productivity [23,31]. Work engagement is characterized by an emotional and psychological connection between employees and their organization, which can manifest in either positive or negative workplace behaviours [32,33]. As noted by [34], individuals are generally more engaged when they feel valued and included. Research indicates that work engagement produces numerous positive outcomes that are significant for both the organization and the individual. One study [35] categorizes the effects of work engagement into three groups: performance, professional outcomes, and personal outcomes. Thus, work engagement is significantly associated with positive work-related outcomes [36] and extends to outcomes beyond the workplace [37].

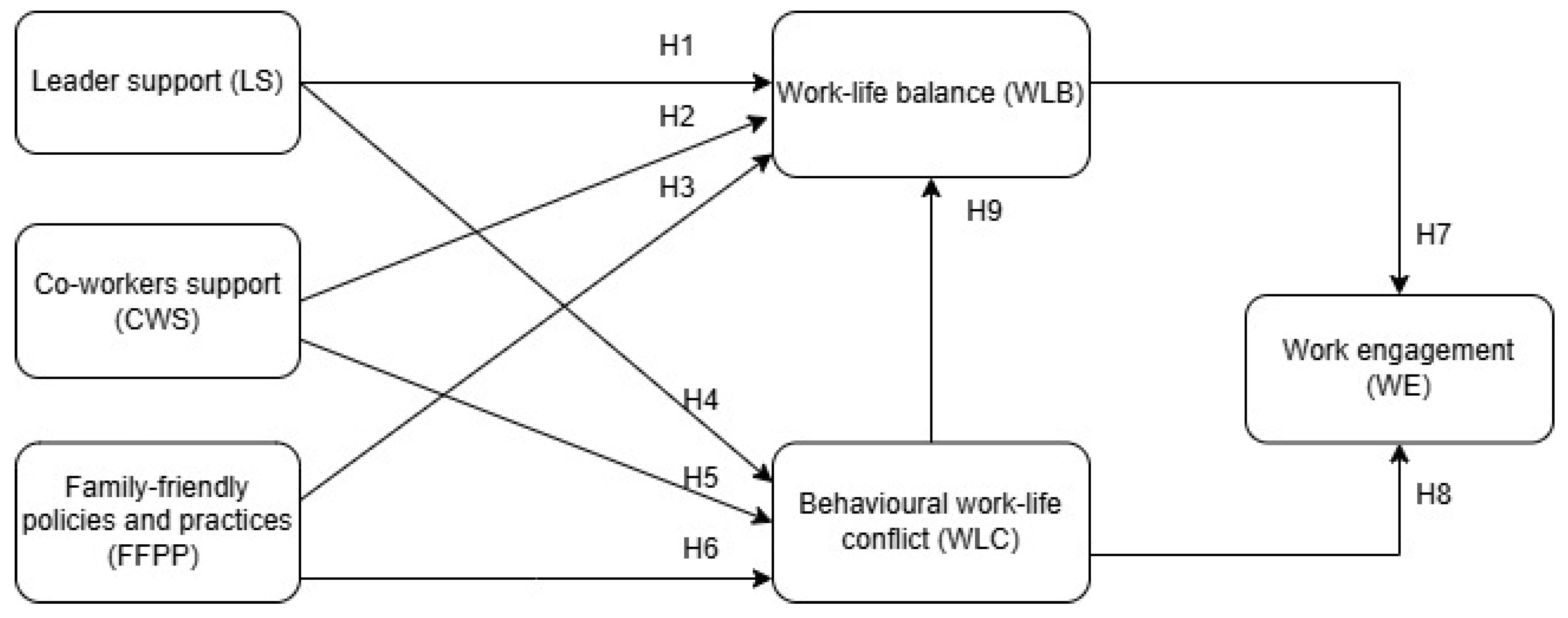

Drawing on the review of prior research, we developed a conceptual model that examines how key organizational resources—leader support, co-worker support and family-friendly policies and practices—shape employees’ work–life balance (WLB), behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC) and their work engagement (WE). The model builds on the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) framework [38], which proposes that job resources promote positive work outcomes, while excessive demands can undermine well-being. It also incorporates the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory [21,22], which explains how resource gain processes (e.g., achieving work–life balance) enhance engagement, whereas resource loss processes (e.g., behavioural spillover between work and private life) reduce it. By integrating both theoretical perspectives, the model captures the positive and negative processes by which organizational support is associated with employees’ experiences at the work–life interface.

Despite growing interest in the work–life interface, most existing studies continue to examine work–life balance (WLB) and work–life conflict separately. In particular, behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC) remains systematically underexplored. As a result, little is known about how positive processes such as WLB and negative processes such as behavioural WLC co-occur, interact, and jointly shape key organizational outcomes such as work engagement. This represents a significant research gap, as treating WLB and BWLC in isolation limits our ability to understand the complex mechanisms of resource gain and resource loss that simultaneously unfold across the work–life boundary.

Drawing on the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model and Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, this study develops an integrated dual-pathway model that conceptualizes WLB as a resource-gain mechanism and BWLC as a resource-loss mechanism. By doing so, the study addresses the research gap by examining both processes within a single conceptual framework and by clarifying how leader support, co-worker support, and family-friendly practices are related to work engagement in the context of positive and negative forms of work–life spillover. This integrated approach provides a more nuanced understanding of which organizational resources most effectively foster healthy work–life functioning while mitigating behavioural interference between domains.

The model makes a meaningful theoretical and practical contribution by offering a more comprehensive perspective on the dynamics of the work–life interface and by identifying organizational practices that can reduce behavioural conflict and strengthen employee engagement. Given that the study is conducted within a European Union member state, where labour standards and organizational frameworks are relatively harmonized, the findings are to broader European and sustainability-oriented contexts. Consequently, the proposed model offers valuable insights for organizations seeking to enhance social sustainability, improve employee well-being, and manage the increasingly complex interplay between work and personal life.

The main contributions of the paper can be summarized as follows:

- Review the existing literature related to work–life balance, behavioural work–life conflict and organizational support within the JD-R and COR frameworks.

- Analyze the relationships between organizational support, resource-gaining (WLB) and resource-losing (BWLC) processes, and work engagement.

- Identify the main organizational conditions that enhance employee well-being and sustain work engagement in broader organizational and European contexts.

Although work–life balance and work–life conflict have been extensively examined in prior research, these constructs are most often studied in isolation and predominantly through a single-valence lens. In particular, behavioural work–life conflict remains underexplored, despite its importance for understanding behavioural spillover across work and non-work domains. Moreover, existing studies rarely consider how positive (resource-gain) and negative (resource-loss) work–life processes operate simultaneously in shaping employee outcomes such as work engagement. Addressing this gap, the present study integrates work–life balance and behavioural work–life conflict within a single analytical framework grounded in the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model and Conservation of Resources (COR) theory. Specifically, work–life balance is conceptualized as a resource-gain mechanism, while behavioural work–life conflict is conceptualized as a resource-loss mechanism. By examining how distinct organizational resources simultaneously influence both mechanisms and how these processes, in turn, relate to work engagement, the study advances a more nuanced understanding of behavioural boundary management. In doing so, it extends fragmented work–life interface research and contributes insights relevant to work engagement and social sustainability in contemporary organizations.

Our paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides background details related to the topic, hypothesis, and model development. In Section 3, we present the methodology, including sample, procedure, instrument and data analysis. In Section 4, we present key results and structural equation modelling. Section 5 provides a discussion on the limitations and main article contribution, and Section 6 is the conclusions.

2. Theoretical Background

This chapter presents the theoretical background for the development of the hypotheses and the proposed model.

2.1. Hypothesis Development

Existing research consistently emphasizes that organizational resources—particularly leader support, co-worker support, and family-friendly policies and practices—are key determinants of employees’ ability to successfully balance work and personal life. Empirical studies show that a supportive work environment significantly enhances work–life balance and strengthens individuals’ sense of control over their life roles [18,39,40]. Family-friendly policies, such as flexible working hours, telework, reduced working hours, or compressed workweeks, provide employees with greater flexibility and autonomy in scheduling their responsibilities and effectively reduce the negative pressures that arise from the interaction of work and private life [16,41]. Evidence from Slovenian organizations likewise confirms that the introduction of such measures improves work–family balance for the majority of employees [42,43]. These findings suggest that a combination of formal policies and interpersonal support represents a crucial mechanism for achieving sustainable work–life balance.

Building on this broad empirical foundation, it is also essential to consider the role of specific organizational resources in shaping employees’ ability to maintain balance between work and personal domains. Leaders who offer understanding, autonomy, and resources facilitate employees’ capacity to manage both professional and personal responsibilities, while supportive co-workers help create a collegial environment that eases the integration of work and non-work domains [44,45,46]. Organizations that adopt family-friendly policies—such as flexible scheduling or parental leave—signal institutional commitment to balance, offering employees greater perceived and actual control over competing role demands [47,48,49]. Yet, empirical findings are not always unanimous. Some studies suggest that formal policies alone may be insufficient if unsupportive workplace cultures or managerial attitudes persist, indicating the complex interplay of structural and interpersonal factors [48]. These inconsistencies highlight the need for further investigation into the distinct and combined effects of supportive leadership, peer relationships, and policy on WLB across organizational settings, leading to the formation of the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1.

Leader support (LS) positively predicts work–life balance (WLB).

Hypothesis 2.

Co-worker support (CWS) positively predicts work–life balance (WLB).

Hypothesis 3.

Family-friendly policies and practices (FFPP) positively predict work–life balance (WLB).

Research on the work–life interface consistently shows that behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC) emerges as a consequence of various work-related and organizational stressors. The most commonly identified antecedents include high workload, unpredictable or unfavourable work schedules, roles ambiguity, and insufficient social support [17,50,51]. Under such conditions, employees struggle to adapt their behaviour to the expectations of different life domains, resulting in BWLC. Empirical studies demonstrate that BWLC substantially reduces perceived work–life balance and adversely affects psychological well-being [52,53]. These findings provide a strong basis for expecting a negative association between BWLC and work–life balance.

Within the organizational context, leader support and co-worker support represent primary social resources that can mitigate behavioural work–life conflict. Leader support enhances clarity of expectations, reduces role-related stressors, and provides flexibility that enables employees to manage boundaries between work and personal life more effectively [17,40]. Similarly, supportive co-workers offer emotional and instrumental assistance that reduces tension arising from competing role demands and facilitates behavioural adjustment across domains [18,54]. Both forms of support strengthen employees’ capacity to manage behavioural demands and reduce instances of conflict between work and non-work roles.

Prior research suggests that behavioural work–life conflict leads to strain and poor boundary management, directly undermining individuals’ sense of balance [9,55]. Supportive leaders and colleagues, as well as organizational policies, are thought to buffer these effects by providing guidance, flexibility, and practical resources [44,45,47]. Accordingly, the present study focuses on examining the direct relationships between organizational resources, behavioural work–life conflict, and work–life balance.

Hypothesis 4.

Leader support (LS) negatively predicts behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC).

Hypothesis 5.

Co-worker support (CWS) negatively predicts behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC).

Hypothesis 9.

Behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC) negatively predicts work–life balance (WLB).

Within the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) framework, organizational resources are understood to facilitate employees’ ability to regulate the boundaries between work and private life by reducing the negative impact of work demands on behavioural spillover across domains [38]. Family-friendly policies and practices—such as flexible scheduling, remote work options, or other forms of temporal and spatial flexibility—provide employees with greater control over how they allocate their responsibilities, thereby alleviating time-, strain- and behaviour-based pressures that contribute to behavioural work–life conflict [16,41,48]. Empirical research further demonstrates that increased access to such practices enhances employees’ sense of autonomy and supports more effective behavioural adjustment between roles, reducing behavioural disruptions across the work and non-work interface [56]. Although some authors note that the effectiveness of formal policies depends on supportive leadership and workplace culture [49], the prevailing evidence confirms their protective effect in mitigating behavioural work–life conflict. On this basis, we hypothesize that family-friendly policies and practices reduce behavioural work–life conflict.

From the perspective of Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, work–life balance (WLB) represents a critical psychosocial resource that enables employees to preserve energy, maintain stability, and exert control over competing role demands [21,22]. The JD-R model similarly conceptualizes resources as motivational drivers that enhance vigour, dedication, and absorption, thereby fostering higher levels of work engagement [38,57]. Empirical studies consistently find that individuals who successfully reconcile their work and non-work responsibilities report higher engagement, more positive affect, and a stronger sense of organizational support [1,23]. Positive emotions arising from well-managed roles demands enhance employees’ emotional and cognitive availability, improving their capacity to focus on work tasks and deepening their engagement [58]. Based on this evidence, we expect that higher work–life balance will positively predict work engagement.

Hypothesis 6.

Family-friendly policies and practices (FFPP) negatively predict behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC).

Hypothesis 7.

Work–life balance (WLB) positively predicts work engagement (WE).

Extensive research consistently demonstrates that behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC) undermines employees’ psychological resources, increases strain, and disrupts role adjustment processes, which in turn diminishes work engagement. Employees who frequently experience behavioural spillover between work and non-work domains report higher emotional exhaustion, reduced attentional capacity, and lower motivation to invest effort in their work roles [17,18]. Prior findings indicate that BWLC erodes key psychological resources—such as energy, focus, and perceived competence—resulting in diminished vigour, dedication, and absorption [53,59]. Because work engagement relies on the availability of such resources and on stable boundaries that support effective role functioning, BWLC emerges as a significant negative predictor of engagement. These insights provide a strong empirical rationale for proposing a negative relationship between BWLC and work engagement.

The final hypothesis posits a negative relationship between behavioural work–life conflict and work engagement, theorizing that ongoing behavioural incompatibility drains psychological resources and reduces employees’ capacity for dedication and absorption at work [9,55]. Accordingly, the present study focuses on examining the relationship between behavioural work–life conflict and work engagement, leading to the final hypothesis:

Hypothesis 8.

Behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC) negatively predicts work engagement (WE).

2.2. Proposed Model

Based on the review of the relevant literature and the development of the study hypotheses, we developed a research model (Figure 1) that examines the relationships between organizational factors—leader support, co-worker support and family-friendly policies and practices—work–life balance (WLB), behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC) and work engagement (WE). The model is theoretically grounded in the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model [20] and the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory [21,22], which jointly explain processes of resource gain and resource loss within the work environment.

Figure 1.

Proposed model.

The JD-R model assumes that employee experiences and outcomes are shaped by two categories of work characteristics: job demands and job resources. Job demands refer to aspects of work that require effort and lead to strain, such as high workload, time pressure and conflicting expectations. In contrast, job resources represent physical, psychological, social and organizational features that help employees cope with demands and foster motivation and engagement—such as leader support, co-worker support and family-friendly practices [57,60]. In our model, leader support (LS), co-worker support (CWS) and family-friendly policies and practices (FFPP) function as key organizational resources. Prior studies have consistently shown that such resources enhance employees’ ability to coordinate work and non-work roles and therefore positively influence work–life balance [40,61], which supports our hypotheses H1–H3. At the same time, these organizational resources reduce pressures, ambiguity and behavioural strain that may otherwise lead to behavioural work–life conflict [16,18], supporting hypotheses H4–H6.

The JD-R model further specifies a motivational pathway and a strain pathway. Following this logic, our model includes a motivational pathway in which work–life balance positively predicts work engagement (H7), as a favourable work–life balance strengthens employees’ energy, motivation and commitment [30]. Conversely, behavioural work–life conflict reflects a form of resource depletion and is therefore expected to negatively influence work engagement (H8), consistent with prior empirical findings [62]. Within the JD-R framework, BWLC is understood as a consequence of excessive or poorly supported job demands, as it signals reduced ability to regulate behaviour between work and non-work domains. In line with this reasoning, we additionally propose that higher levels of work–life balance reduce behavioural work–life conflict, since a well-maintained balance enhances role clarity and reduces behavioural spillover between domains.

The Conservation of Resources (COR) theory enriches these assumptions by explaining how individuals acquire, protect and lose resources, and how these processes shape well-being and behaviour [21,22]. Within our model, work–life balance is conceptualized as a resource-gain mechanism, as successful management of competing roles reduces strain and enhances perceived control [63]. In contrast, behavioural work–life conflict represents a resource-loss mechanism, as behavioural spillover across domains reflects diminished self-regulation and reduced available resources. Organizational resources (LS, CWS, FFPP) act as external mechanisms protecting employees from resource loss and supporting resource preservation [64,65].

The COR theory therefore supports the assumptions that resource gain fosters higher work engagement (WLB → WE), resource loss undermines engagement (BWLC → WE), and that increased resource availability reduces the likelihood of behavioural work–life conflict (WLB → BWLC).

Together, the JD-R and COR theories provide a coherent and complementary theoretical foundation for our model. JD-R clarifies how organizational resources shape employees’ ability to achieve work–life balance and avoid behavioural conflict, while COR explains the underlying dynamics of resource acquisition and depletion that link work–life balance and behavioural conflict to work engagement. The integration of both theories thus captures the positive and negative processes inherent in the work–life interface and highlights the pivotal role of organizational resources in shaping employee outcomes.

Figure 1 presents the research model developed based on the above hypothesis.

3. Methodology

The methodology section outlines the methodology employed in the present study, including the research instrument, sample and procedure characteristics, and analytical approach.

3.1. Sample and Procedure

The study was carried out in the private sector, specifically within business-oriented manufacturing companies in Slovenia. The private sector was selected because private organizations typically operate in a more competitive and dynamic market environment, characterized by higher performance pressures, greater work intensity, and increased expectations for flexibility compared to the public sector. These conditions are frequently associated with stronger challenges in achieving work–life balance [16,66]. Similar international studies confirm that employees in market-driven firms often report higher levels of work–family conflict [11].

The manufacturing sector was chosen because it includes heterogeneous job roles, encompassing both production and administrative positions. This diversity enables a broader understanding of organizational demands and support mechanisms. Moreover, private-sector companies have greater autonomy in implementing HR and family-friendly practices, which is essential for examining organizational support in relation to work–life balance [42].

Although the data were collected in Slovenia, the national context is fully comparable within the European Union, of which Slovenia is a Member State. EU legislation classifies companies into micro-, small-, medium-sized, and large enterprises based on harmonized criteria such as number of employees, turnover, and balance sheet totals [67,68]. In line with this classification, our study focused on small, medium-sized, and large private companies, while micro-enterprises were excluded due to their distinct organizational characteristics.

This research context provides a solid basis for analyzing organizational support, work–life balance, behavioural work–life conflict, and work engagement in a setting that is nationally specific yet aligned with EU-wide business structures.

Several procedural remedies were implemented to mitigate the risk of common method bias. Participation in the survey was voluntary and anonymous, reducing evaluation apprehension and social desirability effects. Items measuring different constructs were interspersed rather than grouped, and no item wording suggested socially desirable responses.

The study sample consisted of 381 respondents employed across a range of organizations. Table 1 summarizes the demographic characteristics of the participants. The sample was 58.5% male (n = 223) and 41.5% female (n = 158). Participants’ ages were distributed as follows: 12.3% up to 25 years, 34.1% aged 26 to 35, 29.7% aged 36 to 45, and 23.9% aged 46 to 60. Educational attainment ranged from primary school (10.2%) and secondary school (48.3%) to college or bachelor’s degree (33.6%), with 7.3% holding a master’s degree and 0.5% a doctorate.

Table 1.

Sample demographics (n = 381).

Table 2 presents the main firm and workplace characteristics. More than half of the respondents (55.6%) worked in large organizations (more than 250 employees), 23.4% in medium-sized organizations (50 to 249 employees), and 21.0% in small organizations (10 to 49 employees). Regarding perceived work demands, 21.8% described their jobs as very demanding, 49.6% as demanding, 26.5% as medium demanding, and 2.1% as undemanding.

Table 2.

Sample firm and workplace characteristics (n = 381).

3.2. Research Instrument

The research instrument utilized in this study was constructed using validated scales from established sources to ensure content validity and comparability with previous research (Table 3). Leader support was measured with items adapted from [46], which capture the extent to which direct supervisors demonstrate sensitivity to employees’ family commitments through scheduling adjustments, attentiveness, and flexibility in assigning work tasks. Co-worker support was assessed using items informed [45,46]. Family-friendly policies and practices were also based on [46], focusing on the availability of flexible work arrangements such as adaptable arrival and departure times, part-time options, and autonomy in managing leave and shift coverage. Work–life balance was measured using items from [53,69], both of which emphasize subjective perceptions of the adequacy of time allocation and coordination between work and non-work roles. Behavioural work–life conflict was measured using four items adapted from [9,55]. In line with established work–family research, behaviour-based work–life conflict is conceptualized as individuals’ perceived incompatibility of role-related behaviours across work and non-work domains. Work engagement was measured using the widely recognized scale by [70], with items capturing enthusiasm, pride, and inspiration derived from one’s work.

Table 3.

Research instrument.

3.3. Data Analysis

Data analysis was performed in two main stages: assessment of the measurement model and testing of the structural model using structural equation modelling (SEM). All analyses were conducted on the full sample of 381 respondents. The measurement model was evaluated using confirmatory factor analysis to assess model fit, reliability, and validity of the latent constructs. Model fit was assessed using established criteria, including the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), and Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI). The thresholds for acceptable model fit were adopted from [71,72].

Convergent validity was assessed by examining standardized factor loadings, the average variance extracted (AVE), and composite reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega). Items with standardized loadings above 0.60 and AVE values above 0.50 were considered to be indicative of adequate convergent validity. Reliability was confirmed if both alpha and omega coefficients exceeded 0.80. Discriminant validity was evaluated using the heterotrait–monotrait ratio (HTMT), with values below 0.85 indicating satisfactory discriminant validity among latent variables.

After establishing the adequacy of the measurement model, the hypothesized structural model was estimated to test relationships among the constructs. Direct effects were tested using SEM, with standardized coefficients, z-values, and p-values reported for each path. The significance of structural paths was evaluated at the 1% and 5% levels. R-squared values for endogenous variables were reported to indicate the proportion of explained variance. All analyses were conducted following recommended best practices for SEM in organizational research [71,72].

4. Results

The results chapter presents the findings from the evaluation of the measurement and structural models. Analyses include tests of model fit, reliability, validity, and the hypothesized relationships among the study variables.

4.1. Reliability and Validity of the Measurement Model

The measurement model was subjected to confirmatory factor analysis to evaluate its fit with the observed data. The chi-square statistic indicated an acceptable model fit, χ2(260) = 431.48, p < 0.001, based on 381 observations and 65 free parameters. As presented in Table 4, all major fit indices surpassed established thresholds: the Comparative Fit Index (CFI) reached 0.922 and the Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) was 0.910, both above the recommended cutoff of 0.900 [71]. The Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) was 0.042 and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) was 0.049, both well below their respective thresholds of 0.060 and 0.080, while the Goodness-of-Fit Index (GFI) was 0.985, exceeding the 0.900 criterion [72]. The presented fit indices jointly indicate that the model demonstrates robust overall fit to the data and provides a strong foundation for further analyses.

Table 4.

Fit indicators.

Table 5 presents the standardized factor loadings (λ), t-values, and p-values for each indicator in the measurement model. All factor loadings are substantial, exceeding 0.63, with several reaching or surpassing 0.80, which demonstrates strong associations between observed indicators and their respective latent constructs. The t-values are consistently high, and all associated p-values are well below the 0.001 threshold, indicating that each loading is highly statistically significant, confirming that each indicator meaningfully represents its intended latent variable, providing evidence for the construct validity of the measurement model.

Table 5.

Standardized loadings (λ) and t-value for the initial measurement model.

Table 6 reports the average variance extracted (AVE), Cronbach’s alpha (α), McDonald’s omega (ω), and the square root of AVE (√AVE) for each latent construct. All AVE values exceed the recommended threshold of 0.50, providing evidence of adequate convergent validity [73]. The square root of AVE is used to assess discriminant validity, with values exceeding the correlations between constructs, thereby supporting the distinctiveness of the measured constructs. Internal consistency reliability is further supported by Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients, both of which are above 0.80 for every construct, indicating strong reliability across the measurement scales. Based on the presented results, it can be concluded that the latent constructs are measured with high reliability and that the observed indicators share sufficient variance to justify their inclusion within each construct.

Table 6.

Average variance extracted for latent constructs (AVE), coefficient α, and coefficient ω.

Table 7 displays the heterotrait–monotrait (HTMT) ratios for all pairs of latent constructs. All HTMT values fall well below the recommended cutoff of 0.85 [74], confirming satisfactory discriminant validity, indicating that the constructs are empirically distinct from each other and that the measurement model adequately differentiates between conceptually separate variables.

Table 7.

Heterotrait–monotrait ratio.

Collectively, the results of the measurement model assessment confirm that all key psychometric criteria have been met. The model demonstrates strong overall fit, high and statistically significant factor loadings, adequate convergent validity, high internal consistency reliability, and clear discriminant validity among the latent constructs. With these measurement properties established, the analysis proceeds to the examination of the structural model and the testing of the hypothesized relationships among the study variables.

4.2. Structural Equation Modelling

Table 8 summarizes the results of the structural equation modelling analysis, presenting the standardized path coefficients, associated test statistics, and statistical significance for each hypothesized relationship. Leader support, co-worker support, and family-friendly policies and practices were all found to be significant positive predictors of work–life balance (H1–H3), collectively explaining 47% of the variance in this construct. Behavioural work–life conflict exhibited a significant negative effect on work–life balance (H4), while leader support had a significant negative effect on behavioural work–life conflict (H5). In contrast, the effects of co-worker support and family-friendly policies and practices on work–life conflict were not statistically significant (H6 and H7). Work–life balance demonstrated a strong positive effect on work engagement (H8), accounting for 37% of its variance. The effect of behavioural work–life conflict on work engagement was negative but not statistically significant (H9). Therefore, the research confirmed the central roles of leader support and work–life balance, as in the proposed model, while highlighting the weaker or nonsignificant impact of co-worker support, family-friendly practices, and behavioural work–life conflict on certain outcomes.

Table 8.

Structural equation modelling results.

The structural equation modelling results provide a clear indication of which factors function as the primary drivers of work–life balance, behavioural work–life conflict, and work engagement in the examined context. Leader support, co-worker support, and family-friendly policies showed significant positive effects on work–life balance, which aligns with previous findings that supportive leadership, collegial assistance, and formal work–family practices enhance employees’ capacity to manage parallel role demands [44,45,47]. The magnitude of the coefficients suggests that leader support and family-friendly practices represent particularly influential resources. This pattern supports arguments that managerial flexibility and organizational policies serve as structural conditions that enable balance, while co-worker support contributes through relational mechanisms [46,48]. The explained variance of 47.0% confirms the practical relevance of these predictors and indicates that work–life balance is strongly shaped by workplace resources.

The negative effect of behavioural work–life conflict on work–life balance is consistent with theoretical accounts that conceptualize conflict as a direct barrier to the integration of work and non-work roles [9,55]. This finding confirms that behavioural incompatibilities operate as a distinct form of strain that erodes overall perceptions of balance. However, in case of the strong leader support, the behavioural work–life conflict tends to be lower, which is in line with prior evidence that supervisor support mitigates role-based tensions and moderates work–family pressures [44]. In contrast, the effects of co-worker support and family-friendly policies on behavioural work–life conflict were not significant, indicating that behavioural conflict may be less responsive to peer-level relational resources or formal policy provisions. Behavioural work–life conflict appears more strongly tied to managerial practices that influence role expectations, boundary permeability, and behavioural norms. This finding raises questions about whether co-workers or policy mechanisms possess sufficient influence to counteract behaviour-based incompatibility, highlighting a need for further research on the specific locus of work–life behavioural conflict triggers.

Work–life balance showed a strong positive effect on work engagement, consistent with the Job Demands–Resources model [70]. Employees who perceive their work and personal roles as manageable exhibit higher energy, enthusiasm, and absorption at work [53,56,57]. The explained variance of 37.1% for the work engagement regression equation underscores the centrality of work–life balance as a motivational resource. In contrast, the negative but nonsignificant effect of increased behavioural work–life conflict on work engagement suggests that behavioural conflict may influence engagement only indirectly, or that its effects are overshadowed by the beneficial impact of balance itself. This result diverges from earlier studies that identified conflict as a key predictor of motivational depletion [9] and indicates the need to examine moderating factors such as resilience, role centrality, and individual coping strategies.

Taken together, the results demonstrate the central roles of leader support and work–life balance within the overall model. They confirm that work–life balance operates as a critical mechanism linking workplace resources to employee engagement. At the same time, they show that co-worker support, family-friendly practices, and behavioural work–life conflict exert more limited or context-dependent effects. These findings reinforce calls for more targeted examinations of how different forms of organizational and social support interact with role demands, behavioural expectations, and individual strategies for managing work–family boundaries [49,69].

5. Discussion

5.1. General Findings

The results of this study provide important insights into how organizational resources shape work–life balance (WLB), behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC), and work engagement (WE) among employees in the private sector. Consistent with the Job Demands–Resources (JD-R) model [38], leader support, co-worker support, and family-friendly policies emerged as key job resources that strengthen WLB. Among these, leader support exerted the strongest influence, confirming prior findings that emphasize the central role of supervisors in creating conditions that enable employees to effectively manage professional and personal responsibilities [17,44,45].

Furthermore, behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC) was found to negatively affect work–life balance (WLB), which is consistent with prior research highlighting the adverse effects of behavioural spillover across life domains [9,55]. Among the examined organizational resources, leader support emerged as the only factor that significantly reduced behavioural conflict, indicating that BWLC is particularly sensitive to norms, expectations, and boundaries shaped by leaders. This finding can be explained through authority-based boundary regulation: leaders possess the formal power to influence task allocation, time expectations, and behavioural norms, and they also act as salient role models who legitimize boundary-setting and the use of flexible arrangements in everyday practice [46,47,48]. Consequently, leader behaviour directly shapes employees’ perceptions of which forms of behavioural spillover are acceptable or sanctioned. In contrast, co-worker support and formal family-friendly practices lack such regulatory authority and, without active supervisory endorsement, do not alter structural role expectations, which may explain their nonsignificant effects on employees’ everyday behavioural practices [44,45]. Accordingly, WLB and BWLC are interpreted as theoretically grounded mechanisms linking organizational resources and work engagement, rather than as statistically confirmed mediators in the present study. This interpretation does not imply that co-worker support or family-friendly policies are irrelevant, but rather that their effectiveness in shaping behavioural work–life conflict may depend on the extent to which leaders actively model, legitimize, and enforce boundary-related norms.

The strongest positive relationship was observed between WLB and WE, supporting Conservation of Resources (COR) theory [21,22], which posits that balance functions are a resource-gain process that enhances energy, motivation, and dedication [1,23]. BWLC did not directly affect WE, indicating that strong work–life balance may buffer the negative effects of behavioural conflict—an interpretation supported by [53,58].

Overall, the results are consistent with a dual-path perspective, whereby organizational resources are associated with higher work–life balance and lower behavioural conflict, and work–life balance is positively related to work engagement.

Although work–life balance and behavioural work–life conflict are strongly related, they represent conceptually distinct constructs. Work–life balance reflects a global, evaluative assessment of compatibility between work and non-work roles, whereas behavioural work–life conflict captures concrete behavioural interference arising from role enactment across domains. Accordingly, behavioural work–life conflict represents one specific pathway through which balance may be undermined, but it does not exhaust the broader construct of work–life balance, which also encompasses cognitive and affective evaluations. The observed negative association therefore reflects theoretical complementarity rather than construct redundancy.

5.2. Theoretical Implications

This study contributes to the literature on the work–life interface on several important levels. First, it confirms the differentiated effects of distinct organizational resources. While leader support, co-worker support, and family-friendly practices all improved WLB, only leader support significantly reduced BWLC. This extends the findings of [44,55], who argue that behavioural conflict is primarily shaped by norms set by direct supervisors.

Second, the results underscore the conceptual importance of work–life balance in understanding the relationship between organizational resources and work engagement. Although behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC) was negatively associated with work–life balance, its direct effect on work engagement was not statistically significant. This absence of a direct relationship suggests that the negative impact of BWLC on engagement may be indirect or buffered by resource-gain processes such as work–life balance. In line with Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, these findings indicate that resource gains can offset concurrent resource losses, thereby preserving employees’ motivational states and sustaining work engagement even in the presence of behavioural conflict.

Third, the study provides theoretical value by integrating positive (WLB) and negative (BWLC) boundary mechanisms into a single model. Existing literature often examines these constructs separately or treats them as independent [69]. This study demonstrates that the two processes are interconnected and jointly shape employee outcomes.

Fourth, the findings reinforce the link between the social dimensions of the work environment and employment outcomes, strengthening the conceptualization of work–life balance as a cornerstone of social sustainability essential for the long-term functioning of organizations [75].

5.3. Practical Implications

The findings of this study have substantial practical implications, especially for human resource management within the context of social sustainability.

First, the findings of this study clearly indicate that generic calls for leadership development are insufficient unless they are translated into specific, observable supervisory behaviours. The strongest effects on improving work–life balance and reducing behavioural work–life conflict are associated with leader behaviours that enable employees to adjust working hours and job demands to family-related needs, redistribute tasks during periods of high family demand, and explicitly legitimize non-work responsibilities. From a practical perspective, leadership development programmes should therefore prioritize these behaviours, which are reflected directly in the leader support measurement items and appear to be particularly effective in reducing behavioural spillover and strengthening employees’ perceived work–life balance. These practices closely correspond to family-supportive supervisory behaviours identified in prior research [44,46] and align with the Job Demands–Resources model, which emphasizes the role of supervisory resources in reducing strain and supporting boundary management [20].

Second, companies should continue to maintain and expand family-friendly practices—such as flexible scheduling, remote work, or accommodations for parents and caregivers. These practices can effectively improve balance when accompanied by strong supervisory support [41,43,48,76]. Family-friendly policies appear to enhance WLB primarily when leaders actively legitimize their use, rather than merely when such policies exist formally.

Third, improving WLB may serve as a powerful lever for enhancing work engagement, which is closely associated with productivity, innovation, and talent retention [1,77].

Fourth, organizations should develop targeted programmes aimed at reducing behavioural conflict, as this form of conflict directly affects behavioural norms, communication, and interpersonal relationships. Strategies such as boundary-management training, leadership coaching, and cultivating a healthy organizational culture may be particularly effective. Additionally, organizations may wish to incorporate resilience-building and grit-enhancement programmes, consistent with the recommendations of [78], who show that strengthening employees’ personal psychological resources supports sustainable engagement and reduces the negative impact of work pressures.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

Despite its significant contributions, the study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design limits the ability to draw causal inferences. Longitudinal or experimental designs would enable a more robust examination of the dynamics among WLB, BWLC, and WE. We also did not conduct a post hoc statistical test for common method bias (e.g., Harman’s single-factor test). However, several procedural remedies were implemented to reduce the risk of common method bias, including guaranteed anonymity, the absence of right or wrong answers, and the psychological separation of predictor and criterion variables. Given the well-documented limitations of such statistical tests, future research should employ longitudinal or multi-source designs to further address potential method bias.

Second, the study was conducted in the Slovenian private sector, which limits generalizability. Cultural factors, labour market structures, and organizational norms may shape how leadership support, peer support, or formal practices function. International comparative studies could illuminate these contextual differences. Although Slovenia represents a regulated labour context within the European Union, the findings of this study should primarily be interpreted within the context of Slovenian manufacturing firms and comparable regulated labour-market settings. While Slovenia shares several institutional characteristics with other EU countries, differences in work–family norms, welfare regimes, and leadership practices suggest that caution is warranted when generalizing the results even within the EU.

In service-based sectors, emotional labour demands are often more pronounced, which may strengthen the relationship between behavioural work–life conflict and work engagement. In public sector contexts, the rigidity of institutional rules and procedures may limit leaders’ discretionary power, thereby reducing the impact of leader support observed in this study. Moreover, in countries with less developed social welfare systems, family-friendly policies and practices may play a more central role than indicated by the present findings. Further, the use of self-report measures increases the risk of common method bias. Future research should incorporate objective data (e.g., overtime records, absenteeism) or supervisor reports. Future research could also complement survey-based measures with diary designs or behavioural observations to capture dynamic enactments of behaviour-based work–life conflict more directly. The model did not include individual-level factors such as resilience, boundary management strategies, personality traits, or partner support, which may influence relationships between resources, conflict, and engagement [18,50]. Future research could explicitly examine whether leader support moderates the effects of co-worker support and family-friendly policies on behavioural work–life conflict.

Next, future research may also explore advanced data aggregation or pooling techniques to better capture complex patterns in work–life dynamics, particularly in longitudinal or multi-source designs. However, such approaches must remain aligned with survey-based and latent-variable research paradigms; techniques developed for image processing or computer vision, such as singular pooling [79], are not directly applicable to the present SEM-based design.

Although work–life balance and behavioural work–life conflict are theoretically positioned as mediating mechanisms in the proposed framework, the present study did not formally test indirect effects using bootstrapped mediation analysis; conclusions regarding mediation therefore remain conceptual rather than statistical. The analysis focused on direct structural relationships within the SEM model. Finally, future research should examine mediation and moderation mechanisms—for example, whether WLB fully or partially mediates the relationship between organizational resources and WE, and whether individual or contextual variables strengthen or weaken these pathways. Future research should formally test these mediation pathways using longitudinal designs and bootstrapped indirect effect estimation.

6. Conclusions

This study provides a comprehensive understanding of how key organizational resources shape employees’ work–life balance (WLB), behavioural work–life conflict (BWLC), and work engagement (WE) within the private sector. The findings confirm that leader support, co-worker support, and family-friendly practices significantly enhance employees’ sense of balance across life domains, with leader support exerting the strongest influence. The results also show that BWLC diminishes perceived balance, whereas the positive association between WLB and work engagement is both strong and consistent.

From a theoretical perspective, the study contributes to the literature by integrating positive (WLB) and negative (BWLC) processes at the work–life interface into a single analytical framework, while empirically demonstrating the distinct roles of individual organizational resources. Importantly, the findings underscore the central role of work–life balance in understanding the relationship between organizational resources and work engagement.

The practical implications highlight that organizations aiming to strengthen social sustainability must invest in supportive leadership practices, foster high-quality workplace relationships, and maintain effective family-friendly policies. Enhancing employees’ work–life balance not only promotes individual well-being but also serves as a key lever for improving organizational performance, resilience, and talent retention. These insights align directly with major Sustainable Development Goals, including good health and well-being, gender equality and care responsibilities, and decent work and economic growth.

The study also has several limitations. The cross-sectional design restricts causal inference, the focus on Slovenia limits generalizability, and the self-reported data raise the possibility of common method bias. Future research should incorporate longitudinal and cross-cultural data and examine additional moderating factors, such as personality traits, boundary management strategies, and contextual characteristics of the workplace. Further research could also explore how digitalization and emerging hybrid work arrangements affect balance, conflict, and employee well-being.

Overall, the findings clearly demonstrate that cultivating a supportive organizational environment is a central component of social sustainability. Organizations that systematically invest in employee support and work–life integration contribute not only to greater employee well-being but also to their own long-term stability and sustainable performance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.Ž.; Methodology, J.Ž.; Validation, M.B.; Formal analysis, J.Ž.; Investigation, J.Ž. and M.B.; Resources, J.Ž.; Writing–original draft, J.Ž.; Writing–review & editing, J.Ž. and M.B.; Supervision, M.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Bedarkar, M.; Pandita, D. A study on the drivers of employee engagement impacting employee performance. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 133, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajni, R. A Comprehensive Study of Work Life Balance Problems in Indian Banking Sector. Int. J. Enhanc. Res. Manag. Comput. Appl. 2015, 4, 37–41. Available online: https://www.erpublications.com/uploaded_files/download/download_21_04_2015_12_47_41.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Prabhu Shankar, M.R.; Mahesh, B.P.; Nanjundeswaraswamy, T.S. Employees’ Perception on Work-Life Balance and its Relation with Job Satisfaction and Employee Commitment in Garment Industry—An Empirical Study. Int. Adv. Res. J. Sci. Eng. Technol. 2007, 3, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshin, J.; Deepu, J.S. Work-life Balance vs. Work-family balance—An Evaluation of Scope. Amity Glob. HRM Rev. 2019, 9, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grzywacz, J.G.; Carlson, D.S. Conceptualizing work—Family balance: Implications for practice and research. Adv. Dev. Hum. Resour. 2007, 9, 455–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dukhaykh, S. Exploring the Relationship Between Work–Family Conflict, Family–Work Conflict and Job Embeddedness: Examining the Mediating Role of Emotional Exhaustion. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2023, 16, 4859–4868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Allen, T.D. Work–family balance: A review and extension of the literature. In Handbook of Occupational Health Psychology; Quick, J.C., Tetrick, L.E., Eds.; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2011; pp. 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Powell, G.N. When work and family are allies: A theory of work-family enrichment. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2006, 31, 72–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Beutell, N.J. Sources of Conflict between Work and Family Roles. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1985, 10, 76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adkins, C.L.; Premeaux, S.F. Spending time: The impact of hours worked on work–family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stier, H.; Lewin-Epstein, N.; Braunc, M. Work-family conflict in comparative perspective: The role of social policies. Res. Soc. Strat. Mobil. 2012, 30, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haines, V.Y.; Harvey, S.; Durand, P.; Marchand, A. Core Self-Evaluations, Work–Family Conflict, and Burnout. J. Marriage Fam. 2013, 75, 778–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Kumar, R. Organisational Work Pressure Rings a “Time-Out” Alarm for Children: A Dual-Career Couple’s Study. Asian J. Manag. Res. 2014, 4, 583–596. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3429591 (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- McNeill, I.M.; Cullington, E. Workload, Work-Life Conflict, and Stress Amongst Mental Health Professionals: The Moderating Role of Segmentation Preference. Stress Health 2025, 41, e70095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Netemeyer, R.G.; Boles, J.S.; McMurrian, R. Development and Validation of Work–Family Conflict and Family–Work Conflict Scales. J. Appl. Psychol. 1996, 81, 400–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyar, S.L.; Maertz, C.P., Jr.; Mosley, D.C., Jr.; Carr, J.C. The impact of work/family demand on work-family conflict. J. Manag. Psychol. 2008, 23, 215–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goh, Z.; Ilies, R.; Wilson, K.S. Supportive supervisors improve employees’ daily lives: The role supervisors play in the impact of daily workload on life satisfaction via work–family conflict. J. Vocat. Behav. 2015, 89, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griggs, T.L.; Casper, W.J.; Eby, L.T. Work, family and community support as predictors of work–family conflict: A study of low-income workers. J. Vocat. Behav. 2013, 82, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, J.R.; Rothbard, N.P. Mechanisms linking work and family: Clarifying the relationship between work and family constructs. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2000, 25, 178–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The spillover-crossover model. Current issues in work and organizational psychology. In New Frontiers in Work and Family Research; Grzywacz, J.G., Demerouti, E., Eds.; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013; pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S.E. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am. Psychol. 1989, 44, 513–524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobfoll, S.E. The Influence of Culture, Community, and the Nested-Self in the Stress Process: Advancing Conservation of Resources Theory. Appl. Psychol. 2001, 50, 337–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timms, C.; Brough, P.; Bauld, R. Balanced Between Support and Strain: Levels of Work Engagement. In Proceedings of the 8th Industrial & Organisational Psychology Conference, Sydney, Australia, 25–28 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Gallup. State of the Global Workplace. 2017. Available online: https://www.gallup.com/workplace/257552/state-global-workplace-2017.aspx (accessed on 16 September 2025).

- Bakker, A.B.; Schaufeli, W.B. Positive organizational behavior: Engaged employees in flourishing organizations. J. Organ. Behav. 2008, 29, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujral, H.K.; Jain, I. Determinants and Outcomes of Employee Engagement: A Comparative Study in Information Technology (IT) Sector. Int. J. Adv. Res. Manag. Soc. Sci. 2013, 2, 207–220. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/5450524/DETERMINANTS_AND_OUTCOMES_OF_EMPLOYEE_ENGAGEMENT_A_COMPARATIVE_STUDY_IN_INFORMATION_TECHNOLOGY_IT_SECTOR_INTRODUCTION (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Job demands, job resources, and their relationship with burnout and engagement: A multi-sample study. J. Organ. Behav. 2004, 25, 293–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Salanova, M.; González-Romá, V.; Bakker, A.B. The measurement of engagement and burnout: A two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J. Happiness Stud. 2002, 3, 71–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B. Utrecth Work Engagement Scale. Occupational Health Psychology Unit Utrecht University. 2003. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=1&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiph_6c277lAhUplIsKHVluBX8QFjAAegQIARAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.wilmarschaufeli.nl%2Fpublications%2FSchaufeli%2FTest%2520Manuals%2FTest_manual_UWES_English.pdf&usg=AOvVaw27fY3f5T8QZ2k5o6GhkKkV (accessed on 15 September 2025).

- Christian, M.S.; Garza, A.S.; Slaughter, J.E. Work engagement: A quantitative review and test of its relations with task and contextual performance. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 89–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, I.-S. Work Engagement and its antecendents and consequences: A case of lecturers teaching synchronous distance education courses. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2017, 72, 655–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrew, O.C.; Sofian, S. Individual Factors and Work Outcomes of Employee Engagement. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2012, 40, 498–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saks, A.M. Antecedents and consequences of employee engagement. J. Manag. Psychol. 2006, 21, 600–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghipour, A.; Dezfuli, Z.K. Designing and Testing a Model of Antecedents of Work Engagement. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 84, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keyko, K.; Cummings, G.G.; Yonge, O.; Wong, C.A. Work engagement in professional nursing practice: A systematic review. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 61, 142–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemeda, H.K.; Lee, J. Leadership styles, work engagement and outcomes among information and communications technology professionals: A cross-national study. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eldor, L.; Harpaz, I.; Westman, M. The Work/Nonwork Spillover: The Enrichment Role of Work Engagement. J. Leadersh. Organ. Stud. 2016, 27, 21–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E. The Job Demands-Resources Model: State of the Art. J. Manag. Psychol. 2007, 22, 309–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, L.T.; Ganster, D.C. Impact of Work-Supportive Work Variables on Work-Family Conflict and Strain: A Control Perscpective. J. Appl. Psychol. 1995, 80, 6–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenhaus, J.H.; Ziegert, J.C.; Allen, T.D. When family-supportive supervision matters: Relations between multiple sources of support and work–family balance. J. Vocat. Behav. 2012, 80, 266–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parakandi, M.; Behery, M. Sustainable human resources: Examining the status of organizational work–life balance practices in the United Arab Emirates. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 55, 1370–1379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaflič, T.; Svetina Nabergoj, A.; Pahor, M. Analiza učinkov uvajanja družini prijaznega delovnega okolja. Econ. Bus. Rev. 2010, 12, 27–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konavec, N. Analiza Učinkov Vpeljevanja Družini Prijaznih Politik v Organizacijo. Ekvilib Inštitut, Ljubljana. 2015. Available online: https://www.certifikatdpp.si/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/Analiza_DPP-anketa_2015_.pdf (accessed on 18 October 2025).

- Kossek, E.E.; Pichler, S.; Bodner, T.; Hammer, L.B. Workplace social support and work–family conflict: A meta-analysis clarifying the influence of general and work–family-specific supervisor and organizational support. Pers. Psychol. 2011, 64, 289–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, K.A.; Dumani, S.; Allen, T.D.; Shockley, K.M. A meta-analysis of work–family conflict and social support. Psychol. Bull. 2018, 144, 284–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammer, L.B.; Kossek, E.E.; Yragui, N.L.; Bodner, T.E.; Hanson, G.C. Development and validation of a multidimensional measure of family supportive supervisor behaviors (FSSB). J. Manag. 2009, 35, 837–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.D. Family-supportive work environments: The role of organizational perceptions. J. Vocat. Behav. 2001, 58, 414–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauregard, T.A.; Henry, L.C. Making the link between work-life balance practices and organizational performance. Hum. Resour. Manag. Rev. 2009, 19, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casper, W.J.; Eby, L.T.; Bordeaux, C.; Lockwood, A.; Lambert, D. A review of research methods in IO/OB work-family research. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 28–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.S.; Kotrba, L.M.; Mitchelson, J.K.; Clark, M.A.; Baltes, B.B. Antecedents of work–family conflict: A meta-analytic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2011, 32, 689–725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, B.; Ma, E.; Hsiao, A.; Ku, M. The work-family conflict of university foodservice managers: An exploratory study of its antecedents and consequences. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2015, 22, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salminen, S.; Mäkikangas, A.; Feldt, T. Job Resources and Work Engagement: Optimism as Moderator Among Finnish Managers. J. Eur. Psychol. Stud. 2014, 5, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M. Testing a new measure of work–life balance: A study of parent and non-parent employees from New Zealand. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2013, 24, 3305–3324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rathi, N.; Barath, M. Work-family conflict and job and family satisfaction. Equal. Divers. Incl. Int. J. 2013, 32, 438–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreiner, G.E.; Hollensbe, E.C.; Sheep, M.L. Balancing borders and bridges: Negotiating the work-home interface via boundary work tactics. Acad. Manag. J. 2009, 52, 704–730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russo, M.; Shteigman, A.; Carmeli, A. Workplace and family support and work–life balance: Implications for individual psychological availability and energy at work. J. Posit. Psychol. 2016, 11, 173–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, J.J.; Schaufeli, W.B.; Ahola, K. The Job Demands-Resources model: A three-year cross-lagged study of burnout, depression, commitment, and work engagement. Work. Stress 2008, 22, 224–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothbard, N.P. Enriching or Depleting? The Dynamics of Engagement in Work and Family Roles. Adm. Sci. Q. 2001, 46, 655–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turliuc, M.N.; Buliga, D. Cognitions and Work-Family Interactions: New Research Directions in Conflict and Facilitation. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 140, 86–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Xanthopoulou, D.; Bakker, A.B.; Demerouti, E.; Schaufeli, W.B. The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int. J. Stress Manag. 2007, 14, 121–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Movilla, J.M.; Munoz, H.F.; Rodriguez, L.P.S.; Sevilla, Y.M. Perception on Work-Life Balance and Job Satisfaction among Employees in a Higher Education Institution. Int. J. Res. Sci. Innov. 2025, 12, 1903–1910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiaolan, S.; Man, J. The impact of work-family conflict on work engagement of female university teachers in China: JD-R perspective. J. Account. Tax. 2023, 15, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandey, A.A.; Cropanzano, R. The Conservation of Resources Model Applied to Work–Family Conflict and Strain. J. Vocat. Behav. 1999, 54, 350–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Contreras, F.; Espinosa, J.C.; Esguerra, G.A. Could Personal Resources Influence Work Engagement and Burnout? A Study in a Group of Nursing Staff. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244019900563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valcour, M. Work-based resources as moderators of the relationship between work hours and satisfaction with work-family balance. J. Appl. Psychol. 2007, 92, 1512–1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bohle, P.; Willaby, H.; Quinlan, M.; McNamara, M. Flexible work in call centres: Working hours, work-life conflict & health. Appl. Ergon. 2011, 42, 219–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Commission Recommendation of 6 May 2003 concerning the definition of micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (2003/361/EC). Off. J. Eur. Union 2003, L 124, 36–41. [Google Scholar]

- STAT. Number of Enterprises by Size of Enterprise. 2019. Available online: https://pxweb.stat.si/SiStatData/pxweb/sl/Data/-/1418801S.px/table/tableViewLayout2/ (accessed on 13 December 2022).

- Carlson, D.S.; Grzywacz, J.G.; Zivnuska, S. Is work—Family balance more than conflict and enrichment? Hum. Relat. 2009, 62, 1459–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaufeli, W.B.; Bakker, A.B.; Salanova, M. The Measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: A cross-national study. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2006, 66, 701–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, L.T.; Bentler, P.M. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 1999, 6, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, G.W.; Rensvold, R.B. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Struct. Equ. Model. Multidiscip. J. 2002, 9, 233–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis, 7th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Henseler, J.; Ringle, C.M.; Sarstedt, M. A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2015, 43, 115–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haar, J.M.; Brougham, D.; Roche, M.A.; Barney, A. Servant leadership and work engagement: The mediating role of work-life balance. N. Z. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2017, 17, 56–72. [Google Scholar]

- Domagalska-Grędys, M.; Sroka, W. A Balanced Professional and Private Life? Organisational and Personal Determinants of Work–Life Balance. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caesens, G.; Stinglhamber, F. The relationship between perceived organizational support and work engagement: The role of self-efficacy and its outcomes. Eur. Rev. Appl. Psychol. 2014, 64, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atan, A.; Gelirli, N. Resilience and Grit for Sustainable Well-Being at Work: Evidence from High-Pressure Service Organizations. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, S.; Cai, J.; Xiong, R.; Zheng, L.; Ma, D. Singular Pooling: A Spectral Pooling Paradigm for Second-Trimester Prenatal Level II Ultrasound Standard Fetal Plane Identification. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 12508–12523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |