Abstract

Vehicular emissions are a major contributor to air pollution and respiratory morbidity in Ecuador’s urban centers. Despite increasing evidence of traffic-related health impacts, national research remains fragmented and unevenly distributed. This narrative review synthesizes 26 peer-reviewed studies published between 2000 and 2024 to characterize vehicular air pollution sources, pollutants, and respiratory health effects in Ecuador. The evidence shows a strong geographic concentration, with more than half of the studies conducted in Quito, followed by Guayaquil and Cuenca. National inventories indicate that the transport sector accounts for approximately 41.7% of Ecuador’s CO2 emissions. Across cities, PM2.5, PM10, NO2, CO, and SO2 were the most frequently assessed pollutants and were repeatedly reported to approach or exceed international guideline values, particularly during traffic peaks and under low-dispersion conditions. Health-related studies documented substantial impacts, including up to 19,966 respiratory hospitalizations in Quito, with short-term PM2.5 exposure associated with increased hospitalization risk in children. Among schoolchildren attending high-traffic schools, carboxyhemoglobin levels above 2.5% were linked to a threefold increase in the risk of acute respiratory infections. Occupationally exposed adults, such as drivers, traffic police officers, and outdoor workers with regular exposure to traffic-related air pollution, also showed a higher prevalence of chronic respiratory symptoms. Environmental evidence further highlighted the accumulation of traffic-related heavy metals (Zn, Cu, Pb, Cr) and pronounced spatial inequalities affecting low-income neighborhoods. Overall, the review identifies aging vehicle fleets and diesel-based transport as dominant contributors to observed pollution and health patterns, while underscoring methodological limitations such as the scarcity of longitudinal studies and uneven monitoring coverage. These findings provide integrated and policy-relevant evidence to support sustainable urban planning, cleaner transport strategies, and targeted respiratory health policies in Ecuador.

1. Introduction

Air pollution is one of the most critical environmental and public health challenges worldwide. According to recent World Health Organization (WHO) reports, nearly 4.2 million people die prematurely due to ambient air pollution [1]. Among the most significant sources of atmospheric pollution are emissions from road transportation, particularly in densely populated urban areas [2,3]. The transportation sector, especially motor vehicle transport, emits a complex mixture of primary pollutants (e.g., PM10/PM2.5, NOx, CO, SO2 and VOCs) and secondary pollutants formed in the atmosphere (e.g., ozone and secondary inorganic/organic aerosols), whose toxicity depends on particle size, chemical composition, and atmospheric transformation processes [4,5]. In addition, the combustion of fossil fuels in internal combustion engines emits greenhouse gases such as CO2 and methane (CH4). Methane is primarily generated through incomplete fuel combustion and the release of unburned hydrocarbons in exhaust systems, contributing to the global climate crisis [6].

In low- and middle-income cities, where environmental controls are often more limited, the combination of an aging vehicle fleet, low-quality fuels, and heavy traffic congestion increases exposure levels [7]. Beyond citywide background concentrations, human exposure is determined by time–activity patterns and microenvironments (home, school, workplace, and in-transport settings), which can lead to significant contrasts between ambient monitoring values and personal exposure, particularly for traffic-related pollutants and along commuting corridors [8]. Suproń and Lacka [9] estimate that road transport accounts for more than 20% of global energy-related CO2 emissions and contributes, to varying degrees, to concentrations of key criteria pollutants (such as NO2 and PM) in urban areas.

Although some regions of the world have successfully implemented emission control policies (including Euro standards, low-emission zones, and incentives for electric vehicles) [10], in many cities across Latin America, Asia, and Africa, vehicular transport remains a dominant source of environmental pollution. This exposure has direct impacts on respiratory, cardiovascular, and neurological health, particularly among vulnerable groups such as children and older adults [11,12].

In Latin America, rapid urban growth, the expansion of the vehicle fleet, and limited enforcement of environmental regulations have contributed to elevated levels of air pollution [13], especially in capital cities such as Mexico City, Lima, Bogotá, Santiago de Chile, and Quito. Despite some progress in air quality monitoring and management, the region still faces significant challenges in controlling vehicular emissions [14]. Across these urban contexts, pollution levels are not determined solely by emission intensity but also by the interaction between traffic-related emissions and local meteorological and topographic conditions, such as boundary-layer dynamics, thermal inversions, wind fields, humidity, and precipitation, which strongly modulate pollutant dispersion and secondary formation. As a result, urban air-quality assessments increasingly integrate chemical transport models and satellite-based products to characterize spatiotemporal gradients and episodic pollution events [15,16].

Ecuador exemplifies these regional challenges in an exacerbated manner. Its complex Andean topography intensifies engine load and emissions in urban valleys, while long-standing limitations in fuel desulfurization contribute to elevated pollutant outputs from vehicular sources [17,18]. According to a study by Viteri et al. [19], approximately 41.7% of the country’s CO2 emissions originate from the transport sector, with heavy-duty vehicles accounting for approximately 60% of the CO emitted by mobile sources. Vehicular air pollution is widely recognized as a major environmental health concern. International evidence has linked transport-related emissions to a broad range of adverse health outcomes, including both respiratory and cardiovascular effects [20,21]. In this context, respiratory outcomes constitute a primary and consistently assessed pathway in studies of traffic-related air pollution, providing a common basis for synthesis across different study designs and settings (as respiratory effects are the primary endpoints in many TRAP studies) [22].

Given this context, although numerous studies have examined traffic-related air pollution in Ecuador, the evidence remains dispersed across cities, pollutants, and analytical approaches, with limited integration of emission sources and respiratory health outcomes at the national level. There is a need to organize the existing body of knowledge, identify gaps in technical and scientific information, and support informed decision-making on a problem that directly affects the quality of life in urban environments across the country.

This paper presents a narrative review of the literature with the aim of comprehensively analyzing atmospheric pollution generated by vehicles in Ecuador, examining its main sources and documented effects on respiratory health. To the best of our knowledge, this review provides the first national-scale synthesis that enables the identification of dominant sources, commonly assessed pollutants, and consistently reported respiratory effects, while highlighting implications for air quality management, sustainable mobility policies, and future research priorities.

2. Methodology

2.1. Type of Review

This study adopts a narrative review approach to synthesize current knowledge on vehicular air pollution and its effects on health and the environment in Ecuador. This approach allows for the integration of evidence derived from studies employing diverse methodological designs—quantitative, qualitative, and mixed—providing a comprehensive overview of the topic from scientific, technical, and public management perspectives.

2.2. Search Strategy

The review draws on peer-reviewed scientific literature retrieved from the following academic databases: ScienceDirect, PubMed, Scielo, Scopus, and SpringerLink. Searches were conducted in both English and Spanish to identify relevant international and regional publications. Keyword combinations included terms such as “vehicle emissions,” “air pollution,” “health impacts,” “Ecuador,” “respiratory disease,” “traffic-related,” and “air quality monitoring.” Boolean operators (AND, OR) and truncations were applied to broaden or refine the search depending on the database. Duplicate records were removed prior to screening. The literature search was completed on 16 July 2025.

Given the multidisciplinary scope of traffic-related air pollution research, encompassing environmental monitoring, epidemiology, and technical assessments, a narrative review framework was considered appropriate for organizing and interpreting the available evidence.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

The documents included in this review meet the following criteria: (i) a focus on air pollution generated by road transport vehicles; (ii) presentation of empirical evidence or technical analysis related to emissions, air quality, respiratory health, or environmental impact; (iii) inclusion of data, case studies, or analyses applied to Ecuador; (iv) publication between 2000 and 2024; (v) availability in Spanish or English; and (vi) an origin from reliable and verifiable sources such as indexed scientific journals, academic institutions, governmental entities, or multilateral organizations.

The following were excluded from the review: (i) articles focused exclusively on industrial or rural pollution sources without a connection to transportation; (ii) opinion pieces, personal essays, or non-scientific outreach articles lacking technical support; and (iii) studies that did not present specific data on Ecuador or whose information was limited to anecdotal or general references.

2.4. Data Extraction

Following the initial screening of titles and abstracts, the full texts of studies meeting the inclusion criteria were reviewed. Each eligible study was coded and summarized using a structured analytical matrix, including reference, pollutants assessed, vehicle type, city or study area, main results, and reported limitations. This matrix served to organize the evidence and facilitate the comparisons across studies prior to the synthesis.

2.5. Evidence Synthesis

A narrative synthesis was subsequently conducted to integrate findings across studies. The evidence was examined by grouping results according to pollutant categories, vehicle types, geographic contexts, and reported health or environmental outcomes. This process aimed to identify recurring patterns, areas of convergence, and key differences in the literature, as well as to highlight common limitations and research gaps relevant to the objectives of the review.

3. Results

3.1. Geographic Distribution of the Studies

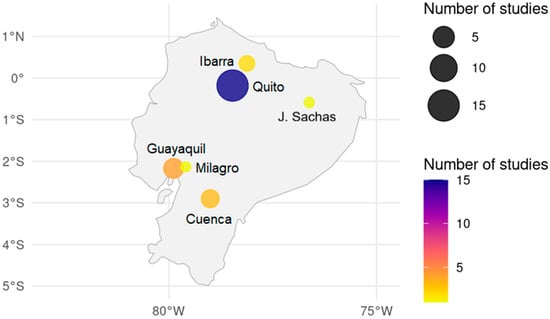

The review included a total of 26 studies that analyzed atmospheric pollution associated with vehicular traffic in Ecuador. A comprehensive summary of the characteristics, pollutants assessed, study locations, and main findings of these studies is provided in Supplementary Table S1. The majority of these studies focused on Quito, which served as the study site in at least 15 investigations, covering urban and peri-urban monitoring stations, schools, industrial zones, road corridors, and satellite or atmospheric modeling analyses [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37] (Figure 1). This predominance confirms Quito’s role as the country’s primary center for air quality research due to its basin-like topography, high altitude, and dense vehicle fleet.

Figure 1.

Spatial distribution of traffic-related air pollution studies in Ecuador.

However, the literature also shows significant territorial diversification. In the Andean region, Cuenca appears in three studies focused on PM2.5, NO2, O3, and the effects of mobility restrictions during the pandemic [30,38,39], while Ibarra features in research on photochemical dynamics and mobile monitoring [32,40]. On the coast, Guayaquil was examined in studies on PM2.5, mixed vehicular–industrial sources, and sector-based pollution characterization [41,42], as well as in the case of General Villamil–Playas, which focused on vehicle maintenance and its environmental impact [43].

In the central–southern agricultural zone, Milagro was the subject of a study addressing exposure and community perceptions related to vehicular and industrial emissions [44]. In the Amazon region, an analysis in Orellana (Joya de los Sachas) assessed environmental impacts associated with heavy machinery and transport in oil-producing areas [45]. Additionally, nationwide analyses included emission inventories, energy projections, and multi-city studies [19,41,46,47].

3.2. Identified Vehicular Pollutants

The pollutants that were examined across the reviewed studies reflect the diversity of emission processes associated with vehicular traffic and related mobile sources. Rather than reiterating the frequencies already summarized in Table 1, this section highlights the analytical emphasis and interpretive relevance of the main pollutant groups reported in the Ecuadorian literature. The majority of the studies focused on particulate matter and traffic-related gaseous pollutants as primary indicators of urban exposure. PM2.5 and NO2 were consistently used as core markers of vehicular influence, given their sensitivity to traffic intensity and their well-documented associations with adverse health outcomes [19,26,28,36,39]. Several investigations further explored short-term temporal variability, linking these pollutants to characteristic rush-hour peaks and low-dispersion conditions in major cities [30,32].

Table 1.

Frequency of pollutants analyzed across the reviewed studies.

Secondary pollutants and photochemical processes were also addressed. Tropospheric ozone (O3) was evaluated in at least 12 studies, particularly in the context of photochemical processes involving NOx and volatile organic compounds. These findings are further interpreted below in relation to the photochemical dynamics and health implications [24,35]. In contrast, SO2 received attention mainly in contexts influenced by the fuel sulfur content and atypical energy-use scenarios, such as power shortages and generator use [36]. Beyond criteria pollutants, a subset of studies incorporated chemical speciation approaches, examining trace metals and soluble ions in particulate matter as indicators of non-exhaust emissions and cumulative environmental contamination. The detection of elements such as Pb, Zn, Cu, Cr, Ni, and V in air samples, soils, vegetation, and bioindicators highlights the relevance of brake and tire wear, diesel combustion, and coexisting industrial activities in shaping the urban contamination profiles [26,27,29].

Greenhouse gases (CO2, CH4) and related hydrocarbons were included in emission inventories and scenario-based studies, linking vehicular activity not only to local air quality degradation but also to broader climate-related implications [19,45,47]. Collectively, the reviewed evidence underscores a shift from single-pollutant assessments toward more integrated analyses that consider atmospheric composition, exposure pathways, and environmental accumulation processes.

3.3. Vehicle Types and Their Contribution to Pollution

The evidence gathered confirms that internal combustion vehicles constitute the main source of atmospheric pollution in Ecuadorian cities. The majority of the studies [23,24,26,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,36,37,38,41,46] identify cars, buses, trucks, and motorcycles as the dominant urban emitters of CO, NO2, NOx, PM2.5, PM10, and SO2. Quantitative inventories indicate a marked contribution from heavy-duty diesel vehicles, particularly buses and trucks, which generate a disproportionate share of emissions relative to their fleet size. As reported in the literature [19,25,35,39], vehicular traffic in Quito accounts for approximately 98.5% of CO emissions and over 60% of PM2.5 concentrations, highlighting the central role of diesel-intensive transport in urban air quality degradation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Conceptual synthesis of vehicle types and associated pollutant profiles reported in Ecuadorian studies.

Smaller vehicle categories (including motorcycles, moto-taxis, taxis, and private light-duty vehicles) have received increasing attention due to their rapid growth and relevance in dense urban settings. Their contribution to CO, NO2, and VOC emissions has been documented in specific contexts [43], while scenario-based analyses suggest that large-scale fleet electrification and the adoption of micromobility could substantially reduce future transport-related emissions [47]. Beyond routine traffic conditions, several studies report measurable emission shifts associated with context-specific events. Mobility restrictions during national strikes and the COVID-19 lockdowns resulted in temporary reductions in traffic-related pollutants [27,46], whereas prolonged power outages revealed the growing importance of alternative sources, including diesel generators, tire burning, and biomass combustion, which led to localized pollution spikes during crisis periods [36]. Heavy machinery used in remediation or industrial activities also contributed locally to mixed pollutant profiles [45].

3.4. Observed Effects on Health and the Environment

The reviewed studies consistently link traffic-related air pollution with adverse respiratory health outcomes in Ecuadorian cities (Table 2). Particulate matter (particularly PM2.5) together with NO2 and CO, were the pollutants most frequently associated with respiratory morbidity across different population groups [23,24,28].

Table 2.

Associations between traffic-related pollutants, respiratory health outcomes, and affected population groups in Ecuador.

Children, outdoor workers, and residents of high-traffic or industrial areas emerged as the most vulnerable populations. Among schoolchildren attending high-traffic schools, CO exposure was associated with a markedly increased risk of acute respiratory infections [23]. Short-term elevations in PM2.5 were linked to higher rates of respiratory hospitalizations in children, while long-term exposure was associated with an increased prevalence of asthma, bronchitis, and pneumonia in urban populations [24,44]. Furthermore, NO2 peaks during rush hours were repeatedly associated with increases in respiratory symptoms and hospital admissions in the general urban population [24,38].

Urban workers, particularly traffic officers and other outdoor workers operating near high-traffic corridors, showed a higher prevalence of wheezing and chronic bronchitis compared with unexposed groups, defined as individuals working in low-traffic or predominantly indoor environments [31]. Experimental evidence provides biological plausibility for these epidemiological findings, as PM10 and PM2.5 exposure were shown to induce inflammatory activation through TLR2/TLR4–NF-κB signaling pathways and the partial activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome [28].

Several studies have also identified short-term temporal associations between elevated NO2 and CO concentrations and COVID-19 outcomes, with the pollutant increases preceding rises in infections and mortality by approximately one to two weeks [38,41]. Although based on ecological designs, these consistent lag patterns suggest that traffic-related pollution may exacerbate susceptibility to respiratory infections during epidemic events.

Beyond health effects, environmental impacts were also documented. In neighborhoods located near traffic corridors or industrial activities, particulate matter concentrations frequently exceeded international guideline values and were enriched with traffic-related metals such as Cr, Zn, Cu, and Pb, indicating cumulative exposure and a potential long-term respiratory burden [27,42].

3.5. Identified Limitations

A recurring weakness in the reviewed studies is the absence of direct clinical measurements, which are frequently replaced by surveys, self-reported symptoms, or aggregated indicators. This limitation is particularly evident in research based on occupational questionnaires or community perceptions [31,43,44], thereby reducing the accuracy of conclusions regarding actual health effects.

Furthermore, the majority of the studies employ ecological, cross-sectional, or short-term designs, which limit the ability to establish robust causal relationships between pollutant exposure and respiratory or cardiovascular outcomes [48]. Such patterns are apparent in studies with brief observation periods, such as analyses of protests, lockdowns, or festive events [27,38,39], as well as in historical investigations with datasets restricted to a single year or to only a few years [23,32,35].

Frequently, confounding factors—including socioeconomic conditions, access to healthcare, nutritional status, weather, or individual behaviors—were not incorporated despite their potential influence on the results. This omission is especially evident in the clinical–environmental studies involving schoolchildren and vulnerable urban populations [23,34,38,44].

Another significant limitation involves methodological heterogeneity in pollutant measurement. Some studies relied on satellite models with reduced coverage due to cloud presence or inconsistencies between satellite and ground-level measurements [30,37,46], while others used international emission factors (from Mexico, the U.S., or Europe) due to the lack of updated local inventories [19,33,39]. These discrepancies affect both the comparability and representativeness of findings across cities and study periods.

An additional cross-cutting limitation concerned data transparency and accessibility. Several studies depended on monitoring data or emission inventories that were not fully available through open-access platforms, thereby restricting independent verification, reproducibility, and secondary analyses. While some municipalities (such as Quito) provided public access to historical air quality data through institutional environmental data portals [49], comparable open datasets and harmonized emission inventories were not consistently available nationwide. Furthermore, the absence of standardized, openly accessible air quality datasets and emission inventories at the national level limited the integration of results across studies and constrained the development of cumulative or longitudinal assessments. Strengthening the open data policies for air quality monitoring networks and promoting harmonized, regularly updated emission inventories would substantially enhance the robustness, transparency, and policy relevance of future research in Ecuador.

Moreover, there is limited information on VOCs, ultrafine particles, black carbon (BC), and the chemical composition of particulate matter, despite their toxicological relevance. Furthermore, only a few studies have characterized trace metals or soluble elements in PM2.5 and PM10 [26,27,28,29], thereby revealing a substantial gap in the understanding of the biological and environmental mechanisms involved. Spatial limitations have also been observed, such as studies that relied on a single monitoring station or on only a few neighborhoods, thereby making it difficult to extrapolate the results to the urban or national scale [34,35,40]. Similarly, limited segmentation by age, occupation, or risk category, together with the frequent use of aggregated health records, restricts the identification of the most vulnerable populations and underscores the need for longitudinal and clinically detailed studies [24,31,34].

4. Discussion

4.1. Main Findings

The findings of this review consistently demonstrate that vehicular air pollution is one of the main determinants of respiratory health deterioration [50] and environmental degradation in urban areas of Ecuador. High concentrations of atmospheric pollutants such as PM2.5, PM10, and NO2, which are attributable to internal combustion vehicles and outdated public transport fleets have been associated with increased hospitalizations due to respiratory diseases, particularly in cities such as Quito and Guayaquil. This strong concentration of evidence in the country’s largest metropolitan areas reflects the spatial distribution of monitoring capacity and research activity and provides robust city-level insights, while also suggesting that national-scale inferences should be interpreted with caution given Ecuador’s marked geographic, topographic, and socio-environmental heterogeneity.

The accumulated evidence indicates that pollutants including PM2.5, PM10, NO2, CO, and SO2, emitted mainly by internal combustion vehicles, diesel-powered public transport, and heavy-duty trucks, frequently exceed international guidelines, especially in Quito, Guayaquil, and Cuenca [51]. The studies analyzed identified clear patterns: (i) hourly peaks associated with traffic (morning and evening rush hours); (ii) seasonal increases linked to the dry season or low-dispersion meteorological conditions; and (iii) critical episodes related to socio-political events (national strikes), prolonged blackouts, and lockdowns, during which vehicular emissions and diesel generator use showed abrupt variations [27,36,46]. These patterns are consistent with global and Latin American evidence indicating that traffic congestion, boundary-layer dynamics, and secondary pollutant formation jointly shape urban exposure profiles, and that cities in the region often face similar challenges related to fleet aging, diesel dependence, and uneven regulatory enforcement. These episodes are of particular relevance given that pollutant concentrations frequently approach or exceed health-based guideline values defined by the WHO [52].

In terms of health outcomes, the reviewed literature demonstrates that prolonged exposure to PM2.5, NO2, and CO is associated with an increased risk of asthma, bronchitis, acute respiratory infections, chronic symptoms, and COPD exacerbations [53,54]. Among children, exposure to heavy traffic has been particularly concerning, with elevated carboxyhemoglobin levels above safety thresholds and higher incidence of respiratory symptoms [23,55]. Adults with occupational exposure (such as traffic officers or urban outdoor workers) exhibit a substantially higher risk of chronic bronchitis and persistent wheezing. These findings align with global evidence establishing a direct connection between vehicular pollution, respiratory morbidity, and premature mortality [56].

Furthermore, the environmental dimension of vehicular pollution also reveals consistent patterns across urban settings. In areas characterized by intense vehicular activity and industrial operations, elevated concentrations of fine particulate matter and associated heavy metals (including Zn, Cu, Pb, Cr, and V) have been detected in air samples, soils, and urban vegetation, indicating chronic contamination processes and long-term environmental accumulation [57]. In addition, photochemical pollution plays a significant role in urban air quality dynamics: ground-level ozone concentrations tend to increase during periods of high solar radiation as a result of interactions between nitrogen oxides and volatile organic compounds, contributing to respiratory irritation and adverse health effects in both adults and children [58].

Collectively, the reviewed studies enable a partial spatiotemporal characterization of traffic-related air pollution in Ecuador, although important limitations persist. The evidence has been largely concentrated at the urban scale and based on fixed monitoring stations, with a primary focus on ambient concentration rather than personal exposure. Vehicle fleet characterization is generally limited to broad categories (light-duty vs. heavy-duty and diesel-based transport), while pollutant assessment prioritizes criteria pollutants and selected metals. Temporal patterns have been primarily inferred from short-term variability, seasonal contrasts, and episodic events, whereas long-term cumulative exposure, biological indicators, and integrated measurement–modeling approaches remain underexplored.

4.2. Environmental and Health Implications in Urban Contexts

Beyond the pollutant-specific associations summarized above, the reviewed evidence supports an integrated exposure–response framework in which the vehicular emissions act through multiple, interrelated pathways affecting both the environmental quality and human health. Traffic-related pollutants such as PM2.5, NO2, CO, and O3 do not operate as isolated stressors but rather as part of complex urban exposure mixtures shaped by traffic intensity, fuel composition, meteorological conditions, and urban morphology. This integrated environment–health perspective aligns with international conceptual models that link emission sources, ambient concentrations, population exposure, biological responses, and health outcomes within urban systems [59].

A cross-cutting dimension emerging from the Ecuadorian evidence is the unequal spatial distribution of both exposure and health impacts. Studies have consistently shown that low-income neighborhoods, industrial zones, and urban peripheries experience a disproportionately higher burden of PM2.5, NO2, and toxic co-pollutants, which is often combined with limited access to healthcare, green infrastructure, and environmental protection measures. This pattern reflects an environmental challenge, whereby socially and economically vulnerable populations bear a greater share of pollution-related health risks despite contributing least to overall emissions. Similar inequities have been documented internationally, reinforcing the relevance of incorporating social vulnerability and equity considerations into air quality management and urban planning strategies [60,61].

From a sustainability perspective, the reviewed literature has highlighted the close connection between vehicular air pollution, respiratory health, and climate change mitigation. The transport sector’s substantial contribution to national greenhouse gas emissions underscores the dual benefits of emission-reduction strategies that simultaneously improve air quality and reduce climate impacts [62]. Emerging evidence on fleet electrification, micromobility, and sustainable transport scenarios suggests that the transitions toward low-emission mobility systems could yield co-benefits for public health, environmental quality, and climate resilience. However, the Ecuadorian context demonstrates that such transitions remain uneven and are currently in their preliminary stages, thereby emphasizing the need for integrated policies that align air quality management, sustainable mobility, and social equity objectives within broader urban sustainability frameworks.

4.3. Implications for Practice

The results of this review underscore the need to strengthen sustainable mobility policies by prioritizing fleet renewal, emission control, and the transition to cleaner technologies. Although initiatives such as the introduction of electric buses and sustainable transport corridors represent important progress in Quito and other cities, their current reach remains limited and requires greater regulatory, financial, and technical support [63]. Similar challenges related to traffic congestion, aging vehicle fleets, and high exposure to traffic-related pollutants have been documented in other Latin American cities, where targeted mobility and traffic-management interventions have resulted in measurable air quality improvements. In this context, expanding incentives for low-emission vehicles, modernizing diesel-based public transport, and integrating micromobility options emerge as policy-relevant measures that can contribute to reducing the urban pollution burden while supporting climate mitigation goals [64], as illustrated by recent experiences in neighboring countries.

One such example has been observed in Peru, where evidence demonstrates the potential effectiveness of targeted traffic management measures as part of an air quality policy. In Metropolitan Lima, the implementation of a traffic regulation and reordering plan along a major urban corridor resulted in substantial and sustained reductions in the ambient pollutant concentrations, including decreases of approximately 62% in PM2.5, 55% in PM10, 65% in NO2, and 82% in SO2 when compared with control avenues without traffic regulation [65]. These results demonstrate that well-designed and consistently enforced traffic interventions can yield rapid air quality improvements in densely populated cities, supporting their relevance for Ecuadorian urban settings facing similar congestion and exposure patterns.

Furthermore, recent evidence from Colombia has highlighted the importance of spatially resolved exposure assessment to inform equitable air quality policies in large Latin American cities. A multicity study using land-use regression models in five major Colombian cities reported pronounced intraurban variability in long-term PM2.5 and NO2 exposure, with traffic density, road infrastructure, and land-use characteristics emerging as key predictors of pollutant concentrations [66]. Compared with the Ecuadorian literature—still largely concentrated in Quito and predominantly based on fixed monitoring stations—these approaches illustrate how expanded exposure modeling can improve the identification of high-risk populations and support more targeted and evidence-based urban air quality interventions.

At both the municipal and national levels, it is essential to reinforce environmental monitoring systems by expanding spatial coverage, ensuring continuous maintenance, and updating measurement protocols. As emphasized by international frameworks for sustainable air quality management, Ecuador would benefit from hybrid monitoring networks that combine regulatory-grade stations with validated low-cost sensors, as well as satellite-based remote sensing products, enabling sub-kilometer spatial resolution and improved characterization of ambient air pollutants in underserved or high-risk areas [37,67,68]. Networks such as REMMAQ should be integrated with early-warning systems, predictive analytics, machine-learning–based forecasting, and real-time public information dashboards. These tools are particularly critical for cities with complex topography and recurring pollution episodes. The improvement of monitoring infrastructure must be complemented by robust governance models that ensure transparency, data accessibility, and sustained institutional coordination.

Additionally, community-based risk communication initiatives designed to help the general population understand pollution dynamics and adopt appropriate protective behaviors are equally significant [69]. Awareness campaigns promoting the rational use of private vehicles, preventative maintenance, and the reduction in fossil fuel consumption should be sustained and culturally adapted. Investments in active mobility infrastructure, cleaner public transport, and climate-resilient mobility planning serve to further support long-term sustainability objectives [70]. Finally, since many Ecuadorian cities face governance and funding constraints similar to those observed across the Global South, collaborative initiatives—such as regional air quality platforms, shared sensor networks, and capacity-building partnerships— might help to bridge technical gaps and accelerate the adoption of sustainable monitoring and management frameworks [71].

4.4. Limitations and Implications for Future Research

From an academic and technical perspective, this review has revealed structural gaps in Ecuadorian research on air pollution and public health. As a narrative review focusing on studies conducted within specific urban and regional contexts, the present work is inherently limited by the scope, the heterogeneity, and the availability of the existing evidence. Significant limitations continue to persist in the development of longitudinal epidemiological studies that are capable of assessing the cumulative or delayed effects of prolonged exposure to vehicular pollutants. Likewise, a limited number of studies have incorporated clinical–laboratory analyses, inflammatory, oxidative, or cardiovascular biomarkers, or the integrated personal-exposure measurements using portable devices, thereby hindering the establishment of more definitive causal relationships between traffic-related pollution and pulmonary or systemic health outcomes; it should also be noted that the analysis of non-respiratory outcomes was beyond the scope of the present review [72]. Accordingly, future research should expand this focus by incorporating cardiovascular and other systemic outcomes, enabling a more comprehensive assessment of traffic-related health impacts.

Within the subset of transport-related air pollution studies included in this review, several methodological gaps persist. Furthermore, most investigations have focused on isolated pollutant–health associations without assessing the potential interactions between multiple pollutants or combined exposures to environmental stressors, thereby limiting insights into synergistic or antagonistic effects [73]. Moreover, few studies have systematically incorporated seasonal variability in pollutant levels, and detailed stratification by age, occupation, gender, mobility patterns, or socioeconomic vulnerability remains scarce. Key epidemiological confounders, such as smoking habits, socioeconomic status, meteorological conditions, and background respiratory infections, have been inconsistently reported or controlled across studies, limiting comparability and causal inference.

These limitations partially reflect the design constraints of studies conducted in specific cities or during short observation periods, underscoring the need for epidemiological studies with multidimensional exposure metrics and robust analytical frameworks to better quantify associations between traffic-related air pollution and health outcomes. Such frameworks may include multivariable and machine learning approaches for exposure prediction, which have been shown to improve the estimation of ambient concentrations of key traffic-related pollutants [74].

Another important gap pertains to the limited integration between measurement-based observations and atmospheric modeling frameworks, as well as the insufficient assessment of interactions among multiple pollutants. Furthermore, the present review demonstrates that many Ecuadorian studies have relied on a restricted number of monitoring stations or short-term campaigns, thereby limiting their spatial representativeness. Tools such as WRF-Chem, CMAQ, or GEOS-Chem, combined with data assimilation techniques and validated low-cost sensors [75], could improve exposure estimates in areas with limited monitoring coverage, such as peri-urban, rural, and Amazonian regions. Similarly, updating local emission inventories is essential to avoid reliance on international emission factors that do not reflect the specific characteristics of the Ecuadorian vehicle fleet.

At the institutional level, sustained intersectoral collaborations are required among universities, municipalities, ministries, mobility observatories, and health centers. Furthermore, from the perspective of future research, comparative and collaborative studies with neighboring countries would serve to contextualize Ecuadorian findings within the broader regional dynamics, including transboundary processes such as the regional pollutant transport, the volcanic ash dispersion, or aerosol intrusions. Moreover, it is crucial to incorporate environmental justice and social epidemiology approaches, which examine how vehicular pollution disproportionately affects low-income communities, informal workers, children, and older adults. These perspectives—combined with the implementation of participatory methodologies and community monitoring—will support the development of public policies that are more equitable, sensitive to historical inequalities, and grounded in robust local evidence [76].

5. Conclusions

This narrative review demonstrates that vehicular emissions constitute a dominant driver of urban air pollution and respiratory burden in Ecuador, with the evidence concentrated in major cities where traffic intensity, fleet aging, and diesel-based transport shape exposure patterns. Across the analyzed studies, recurrent temporal dynamics linked to traffic peaks, seasonal dispersion conditions, and exceptional events have consistently revealed associations with adverse respiratory outcomes, particularly among children and occupationally exposed adults, as well as the long-term environmental deposition near high-traffic corridors. The findings further highlight marked spatial inequalities, with socially vulnerable and peripheral neighborhoods experiencing disproportionate exposure, underscoring an environmental justice dimension of urban air pollution. Despite these insights, the evidence base remains constrained by short-term designs, limited clinical and personal-exposure assessments, and uneven monitoring coverage, which restrict causal inference and national generalization. Future research should therefore prioritize longitudinal and integrative approaches that combine epidemiology, atmospheric modeling, and updated emission inventories, while explicitly incorporating vulnerability and equity perspectives. Advancing these directions is essential for generating robust, context-specific evidence capable of informing sustainable mobility strategies and equitable air quality policies in Ecuador.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18031262/s1, Table S1: Overview of traffic-related air quality studies included in this review.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.C.-C. and J.B.; methodology, D.C.-C. and J.B.; validation, D.C.-C. and J.B.; formal analysis, D.C.-C. and J.B.; investigation, D.C.-C. and J.B.; resources, D.C.-C. and J.B.; data curation, D.C.-C. and J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, D.C.-C. and J.B.; writing—review and editing, D.C.-C. and J.B.; visualization, D.C.-C.; supervision, J.B.; project administration, J.B.; funding acquisition, J.B. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica through the project “Análisis del uso de la inteligencia artificial generativa en contextos de formación y operación profesional”, grant number IIDI-059-2026. The APC was funded by Universidad Tecnológica Indoamérica.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data supporting the findings of this review consist exclusively of previously published articles and publicly available institutional reports cited within the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT 5.1 to support grammar refinement, language clarity, and style consistency. The authors reviewed, edited, and took full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

| ARI | Acute respiratory infection |

| BC | Black carbon |

| CMAQ | Community multiscale air quality |

| CO | Carbon monoxide |

| COHb | Carboxyhemoglobin |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| COPD | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| Cr | Chromium |

| Cu | Copper |

| GEOS-Chem | Goddard earth observing system-chemistry |

| NH4+ | Ammonium |

| Ni | Nickel |

| NOx | Nitrogen oxides |

| NO2 | Nitrogen dioxide |

| NO3− | Nitrate |

| Pb | Lead |

| PM | Particulate matter |

| PM1/PM2.5/PM10 | Particles < 1 µm/<2.5 µm/<10 µm |

| REMMAQ | Red Metropolitana de Monitoreo Atmosférico de Quito |

| SO2 | Sulfur dioxide |

| SO42− | Sulfate |

| TRAP | Traffic-related air pollution |

| V | Vanadium |

| VOCs | Volatile organic compounds |

| WRF-Chem | Weather research and forecasting-chemistry |

| Zn | Zinc |

References

- Singh, G.K.; Rai, S.; Jadon, N. Major Ambient Air Pollutants and Toxicity Exposure on Human Health and Their Respiratory System: A Review. J. Environ. Manag. Tour. JEMT 2021, 7, 1774–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez-Aparicio, S.; Grythe, H.; Drabicki, A.; Chwastek, K.; Toboła, K.; Górska-Niemas, L.; Kierpiec, U.; Markelj, M.; Strużewska, J.; Kud, B.; et al. Environmental Sustainability of Urban Expansion: Implications for Transport Emissions, Air Pollution, and City Growth. Environ. Int. 2025, 196, 109310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crippa, M.; Guizzardi, D.; Pisoni, E.; Solazzo, E.; Guion, A.; Muntean, M.; Florczyk, A.; Schiavina, M.; Melchiorri, M.; Hutfilter, A.F. Global Anthropogenic Emissions in Urban Areas: Patterns, Trends, and Challenges. Environ. Res. Lett. 2021, 16, 074033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meo, S.A.; Shaikh, N.; Alotaibi, M. Association between Air Pollutants Particulate Matter (PM2.5, PM10), Nitrogen Dioxide (NO2), Sulfur Dioxide (SO2), Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs), Ground-Level Ozone (O3) and Hypertension. J. King Saud Univ.-Sci. 2024, 36, 103531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobias, A.; Kim, Y.; Madaniyazi, L. Time-Stratified Case-Crossover Studies for Aggregated Data in Environmental Epidemiology: A Tutorial. Int. J. Epidemiol. 2024, 53, dyae020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaworski, A.; Kuszewski, H.; Balawender, K.; Woś, P.; Lew, K.; Jaremcio, M. Assessment of CH4 Emissions in a Compressed Natural Gas-Adapted Engine in the Context of Changes in the Equivalence Ratio. Energies 2024, 17, 2095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalakeviciute, R.; Lopez-Villada, J.; Ochoa, A.; Moreno, V.; Byun, A.; Proaño, E.; Mejía, D.; Bonilla-Bedoya, S.; Rybarczyk, Y.; Vallejo, F. Urban Air Pollution in the Global South: A Never-Ending Crisis? Atmosphere 2025, 16, 487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, P.T.B.S.; Alvim-Ferraz, M.C.M.; Martins, F.G.; Sousa, S.I.V. The Microenvironmental Modelling Approach to Assess Children’s Exposure to Air Pollution—A Review. Environ. Res. 2014, 135, 317–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suproń, B.; Łącka, I. Research on the Relationship between CO2 Emissions, Road Transport, Economic Growth and Energy Consumption on the Example of the Visegrad Group Countries. Energies 2023, 16, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tipton, M.J.; Lathem, T.L.; Fu, J.S.; Tschantz, M.F. Effectiveness of Emissions Standards on Automotive Evaporative Emissions in Europe under Normal and Extreme Temperature Conditions. Environ. Res. Commun. 2022, 4, 081003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guerra, E.; Montejano, J.; Reyes, A.; Vergel-Tovar, E. Transportation and Emissions in Latin American Cities. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 123, 103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardoy, J.E.; Mitlin, D.; Satterthwaite, D. The Rural, Regional and Global Impacts of Cities in Africa, Asia and Latin America. In The Earthscan Reader in Sustainable Cities; Routledge: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Follmann, A.; Willkomm, M.; Dannenberg, P. As the City Grows, What Do Farmers Do? A Systematic Review of Urban and Peri-Urban Agriculture under Rapid Urban Growth across the Global South. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 215, 104186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergel-Tovar, C.E. Sustainable Transit and Land Use in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Review of Recent Developments and Research Findings. In Urban Transport and Land Use Planning: A Synthesis of Global Knowledge; Advances in Transport Policy and Planning; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2022; Volume 9, pp. 29–73. ISBN 978-0-12-824080-9. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, Z.; Zhou, X. A Review of the CAMx, CMAQ, WRF-Chem and NAQPMS Models: Application, Evaluation and Uncertainty Factors. Environ. Pollut. 2024, 343, 123183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, X.; Yu, S.; Li, J.; Sun, Y.; Song, Z.; Yao, N.; Li, P. The WRF-CMAQ Simulation of a Complex Pollution Episode with High-Level O3 and PM2.5 over the North China Plain: Pollution Characteristics and Causes. Atmosphere 2024, 15, 198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lara-Calle, A.; Espinoza-Tenemaza, J.; Buele, J. Monitoring Air Pollutants in Industrial Settings: A Study in Tungurahua, Ecuador. In Information Technology and Systems; Rocha, A., Ferrás, C., Calvo, H., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2025; pp. 125–134. [Google Scholar]

- Jácome-Galarza, L.-R.; Jaramillo-Sangurima, W.-E.; Jaramillo-Luzuriaga, S.-A. Traffic Congestion in Ecuador: A Comprehensive Review, Key Factors, Impact, and Solutions of Smart Cities. Lat.-Am. J. Comput. 2025, 12, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Viteri, R.; Borge, R.; Paredes, M.; Pérez, M.A. A High Resolution Vehicular Emissions Inventory for Ecuador Using the IVE Modelling System. Chemosphere 2023, 315, 137634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nishida, C.; Yatera, K. The Impact of Ambient Environmental and Occupational Pollution on Respiratory Diseases. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.M.; Tsai, F.-J.; Lee, Y.-L.; Chang, J.-H.; Chang, L.-T.; Chang, T.-Y.; Chung, K.F.; Kuo, H.-P.; Lee, K.-Y.; Chuang, K.-J.; et al. The Impact of Air Pollution on Respiratory Diseases in an Era of Climate Change: A Review of the Current Evidence. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 898, 166340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, X.; Zhang, Q.; Du, X.; Jiang, Y.; Niu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Chillrud, S.N.; Liang, D.; Li, H.; et al. Respiratory Effects of Traffic-Related Air Pollution: A Randomized, Crossover Analysis of Lung Function, Airway Metabolome, and Biomarkers of Airway Injury. Environ. Health Perspect. 2023, 131, 057002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estrella, B.; Estrella, R.; Oviedo, J.; Narváez, X.; Reyes, M.T.; Gutiérrez, M.; Naumova, E.N. Acute Respiratory Diseases and Carboxyhemoglobin Status in School Children of Quito, Ecuador. Environ. Health Perspect. 2005, 113, 607–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Gladson, L.; Díaz Suárez, V.; Cromar, K. Respiratory Health Impacts of Outdoor Air Pollution and the Efficacy of Local Risk Communication in Quito, Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 6326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurado, J.; Southgate, D. Dealing with Air Pollution in Latin America: The Case of Quito, Ecuador. Environ. Dev. Econ. 1999, 4, 375–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalakeviciute, R.; Alexandrino, K.; Rybarczyk, Y.; Debut, A.; Vizuete, K.; Diaz, M. Seasonal Variations in PM10 Inorganic Composition in the Andean City. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 17049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalakeviciute, R.; Alexandrino, K.; Mejia, D.; Bastidas, M.G.; Oleas, N.H.; Gabela, D.; Chau, P.N.; Bonilla-Bedoya, S.; Diaz, V.; Rybarczyk, Y. The Effect of National Protest in Ecuador on PM Pollution. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cevallos, V.M.; Díaz, V.; Sirois, C.M. Particulate Matter Air Pollution from the City of Quito, Ecuador, Activates Inflammatory Signaling Pathways in Vitro. Innate Immun. 2017, 23, 392–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raysoni, A.U.; Armijos, R.X.; Weigel, M.M.; Echanique, P.; Racines, M.; Pingitore, N.E.; Li, W.-W. Evaluation of Sources and Patterns of Elemental Composition of PM2.5 at Three Low-Income Neighborhood Schools and Residences in Quito, Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mejía, C.D.; Faican, G.; Zalakeviciute, R.; Matovelle, C.; Bonilla, S.; Sobrino, J.A. Spatio-Temporal Evaluation of Air Pollution Using Ground-Based and Satellite Data during COVID-19 in Ecuador. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Villacis Medina, D.F.; Piedra Gonzalez, J.P. Síntomas respiratorios en agentes civiles de tránsito expuestos a smog en Quito en el año 2021. Cambios Rev. Méd. 2021, 20, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andino-Enríquez, M.A.; Hidalgo-Bonilla, S.P.; Ladino, L.A. Comparison of Tropospheric Ozone and Nitrogen Dioxide Concentration Levels in Ecuador and Other Latitudes. Rev. Bionatura 2018, 3, 586–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancheno, G.; Jorquera, H. High Spatial Resolution WRF-Chem Modeling in Quito, Ecuador. Environ. Sci. Adv. 2025, 4, 1310–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Allauca, A.D.; Pérez Castillo, C.G.; Villacis Uvidia, J.F.; Abdo-Peralta, P.; Frey, C.; Ati-Cutiupala, G.M.; Ureña-Moreno, J.; Toulkeridis, T. Relationship between COVID-19 Cases and Environmental Contaminants in Quito, Ecuador. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2024, 21, 1336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrino, K.; Zalakeviciute, R.; Viteri, F. Seasonal Variation of the Criteria Air Pollutants Concentration in an Urban Area of a High-Altitude City. Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2021, 18, 1167–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, F.; Villacrés, P.; Yánez, D.; Espinoza, L.; Bodero-Poveda, E.; Díaz-Robles, L.A.; Oyaneder, M.; Campos, V.; Palmay, P.; Cordovilla-Pérez, A.; et al. Prolonged Power Outages and Air Quality: Insights from Quito’s 2023–2024 Energy Crisis. Atmosphere 2025, 16, 274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez-Mendoza, C.I.; Teodoro, A.; Torres, N.; Vivanco, V.; Ramirez-Cando, L. Comparison of Satellite Remote Sensing Data in the Retrieve of PM10 Air Pollutant over Quito, Ecuador. In Proceedings of the Remote Sensing Technologies and Applications in Urban Environments III, Berlin, Germany, 9 October 2018; Volume 10793, pp. 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera Campoverde, N.D.; Molina Campoverde, P.A.; Novillo Quirola, G.P.; Ortiz Valverde, W.F.; Serrano Ortiz, B.M. Influence of Mobility Restrictions on Air Quality in the Historic Center of Cuenca City and Its Inference on the COVID-19 Rate Infections. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 49, 64–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parra, R.; Saud, C.; Espinoza, C. Simulating PM2.5 Concentrations during New Year in Cuenca, Ecuador: Effects of Advancing the Time of Burning Activities. Toxics 2022, 10, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvear-Puertas, V.E.; Burbano-Prado, Y.A.; Rosero-Montalvo, P.D.; Tözün, P.; Marcillo, F.; Hernandez, W. Smart and Portable Air-Quality Monitoring IoT Low-Cost Devices in Ibarra City, Ecuador. Sensors 2022, 22, 7015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacheco, H.; Díaz-López, S.; Jarre, E.; Pacheco, H.; Méndez, W.; Zamora-Ledezma, E. NO2 Levels after the COVID-19 Lockdown in Ecuador: A Trade-off between Environment and Human Health. Urban Clim. 2020, 34, 100674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rincon, G.; Morantes, G.; Roa-López, H.; Cornejo-Rodriguez, M.d.P.; Jones, B.; Cremades, L.V. Spatio-Temporal Statistical Analysis of PM1 and PM2.5 Concentrations and Their Key Influencing Factors at Guayaquil City, Ecuador. Stoch. Environ. Res. Risk Assess. 2023, 37, 1093–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Llerena Mena, A.F.; Gómez Berrezueta, M.F.; Jerez Mayorga, D.A.; Peña Pinargote, A.J. Vehicle Preventive Maintenance: A Comprehensive Analysis of Its Impact on Society, Economic, and Environmental Factors in General Villamil Playas City. South Fla. J. Dev. 2024, 5, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro Vásquez, D.I.; Cujilan Cortez, Z.A.; Mendieta Tobar, N.B.; Tomalá Cabrera, E.E.; Villanueva Real, L.Z.; Guillen Godoy, M.A. Monóxido de Carbono (CO), Dióxido de Carbono (CO2) y sus Efectos en Enfermedades Respiratorias. Rev. Científica Multidiscip. SAGA 2025, 2, 397–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Villacís, K.; Ramos-Guerrero, L.; Canga, J.L.; Hidalgo-Lasso, D.; Vargas-Jentzsch, P. Environmental Impact Assessment of Remediation Strategy in an Oil Spill in the Ecuadorian Amazon Region. Pollutants 2021, 1, 234–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atiaga, O.; Guerrero, F.; Páez, F.; Castro, R.; Collahuazo, E.; Nunes, L.M.; Grijalva, M.; Grijalva, I.; Otero, X.L. Assessment of Variations in Air Quality in Cities of Ecuador in Relation to the Lockdown Due to the COVID-19 Pandemic. Heliyon 2023, 9, e17033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atiaja, J.; Arroyo, F.; Hidalgo, V.; Erazo, J.; Remache, A.; Bravo, D. Dynamic Simulation of Energy Scenarios in the Transition to Sustainable Mobility in the Ecuadorian Transport Sector. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krittanawong, C.; Qadeer, Y.K.; Hayes, R.B.; Wang, Z.; Thurston, G.D.; Virani, S.; Lavie, C.J. PM2.5 and Cardiovascular Diseases: State-of-the-Art Review. Int. J. Cardiol. Cardiovasc. Risk Prev. 2023, 19, 200217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Secretaría de Ambiente del Distrito Metropolitano de Quito. Open Air Quality Data Repository (REMMAQ); Secretaría de Ambiente del Distrito Metropolitano de Quito: Quito, Ecuador, 2025; Available online: https://datosambiente.quito.gob.ec (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Bălă, G.-P.; Râjnoveanu, R.-M.; Tudorache, E.; Motișan, R.; Oancea, C. Air Pollution Exposure—The (in)Visible Risk Factor for Respiratory Diseases. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 19615–19628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran-Zuloaga, D.; Merchan-Merchan, W.; Rodríguez-Caballero, E.; Hernick, P.; Cáceres, J.; Cornejo, M.H. Overview and Seasonality of PM10 and PM2.5 in Guayaquil, Ecuador. Aerosol Sci. Eng. 2021, 5, 499–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines: Particulate Matter (PM2.5 and PM10), Ozone, Nitrogen Dioxide, Sulfur Dioxide and Carbon Monoxide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021.

- Bouza, E.; Vargas, F.; Alcázar, B.; Álvarez, T.; Asensio, Á.; Cruceta, G.; Gracia, D.; Guinea, J.; Gil, M.A.; Linares, C.; et al. Air Pollution and Health Prevention: A Document of Reflection. Rev. Esp. Quim. 2022, 35, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curtis, L.; Rea, W.; Smith-Willis, P.; Fenyves, E.; Pan, Y. Adverse Health Effects of Outdoor Air Pollutants. Environ. Int. 2006, 32, 815–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holguín-Carvajal, J.P.; Otzen, T.; Sanhueza, A.; Castillo, Á.; Manterola, C.; Muñoz, G.; García-Aguilera, F.; Salgado-Castillo, F. Trends in Traffic Accident Mortality and Social Inequalities in Ecuador from 2011 to 2022. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- State of Global Air. State of Global Air Report 2025: A Report on Air Pollution and Its Role in the World’s Leading Causes of Death. Available online: https://www.stateofglobalair.org/resources/report/state-global-air-report-2025 (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Fischer, G.; Fischer-García, F.L.; Fischer, G.; Fischer-García, F.L. Heavy Metal Contamination of Vegetables in Urban and Peri-Urban Areas. An Overview. Rev. Colomb. Cienc. Hortícolas 2023, 17, e16099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazorla, M.; Parra, R.; Herrera, E.; da Silva, F.R. Characterizing Ozone throughout the Atmospheric Column over the Tropical Andes from in Situ and Remote Sensing Observations. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 2021, 9, 00019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriazu-Ramos, A.; Santamaría, J.M.; Monge-Barrio, A.; Bes-Rastrollo, M.; Gutierrez Gabriel, S.; Benito Frias, N.; Sánchez-Ostiz, A. Health Impacts of Urban Environmental Parameters: A Review of Air Pollution, Heat, Noise, Green Spaces and Mobility. Sustainability 2025, 17, 4336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Fan, C.; Chien, Y.-H.; Mostafavi, A. Human Mobility Disproportionately Extends PM2.5 Emission Exposure for Low Income Populations. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 119, 106063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hidalgo, D.; Huizenga, C. Implementation of Sustainable Urban Transport in Latin America. Res. Transp. Econ. 2013, 40, 66–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soares, F.; Silva, M.C.; Azevedo, I. Urban Decarbonization Policies and Strategies: A Sectoral Review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 215, 115617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2023: Catching Up with Climate Ambitions; IEA: Paris, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Bagkis, E.; Hassani, A.; Schneider, P.; DeSouza, P.; Shetty, S.; Kassandros, T.; Salamalikis, V.; Castell, N.; Karatzas, K.; Ahlawat, A.; et al. Evolving Trends in Application of Low-Cost Air Quality Sensor Networks: Challenges and Future Directions. npj Clim. Atmos. Sci. 2025, 8, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapia, V.; Carbajal, L.; Vásquez, V.; Espinoza, R.; Vásquez-Velásquez, C.; Steenland, K.; Gonzales, G.F. Reordenamiento vehicular y contaminación ambiental por material particulado (2.5 y 10), dióxido de azufre y dióxido de nitrógeno en Lima Metropolitana, Perú. Rev. Peru Med. Exp. Salud Pública 2018, 35, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Villamizar, L.A.; Rojas, Y.; Grisales, S.; Mangones, S.C.; Cáceres, J.J.; Agudelo-Castañeda, D.M.; Herrera, V.; Marín, D.; Jiménez, J.G.P.; Belalcázar-Ceron, L.C.; et al. Intra-Urban Variability of Long-Term Exposure to PM2.5 and NO2 in Five Cities in Colombia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 3207–3221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, C.I.; López, S.; Vásquez, D.; Gualotuña, D. Assessing Air Quality Dynamics during Short-Period Social Upheaval Events in Quito, Ecuador, Using a Remote Sensing Framework. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porcheddu, A.; Kolehmainen, V.; Lähivaara, T.; Lipponen, A. Machine Learning Data Fusion for High Spatio-Temporal Resolution PM2.5. Atmos. Meas. Tech. 2025, 18, 4771–4789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huertas, J.I.; Stöffler, S.; Fernández, T.; García, X.; Castañeda, R.; Serrano-Guevara, O.; Mogro, A.E.; Alvarado, D.A. Methodology to Assess Sustainable Mobility in LATAM Cities. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco Arevalo, A.; Gerike, R. Sustainability Evaluation Methods for Public Transport with a Focus on Latin American Cities: A Literature Review. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2023, 17, 1236–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sserunjogi, R.; Ogenrwot, D.; Niwamanya, N.; Nsimbe, N.; Bbaale, M.; Ssempala, B.; Mutabazi, N.; Wabinyai, R.F.; Okure, D.; Bainomugisha, E. Design and Evaluation of a Scalable Data Pipeline for AI-Driven Air Quality Monitoring in Low-Resource Settings. In Software and Data Engineering; Rahimi, N., Margapuri, V., Golilarz, N.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2026; pp. 212–231. [Google Scholar]

- Boogaard, H.; Patton, A.P.; Atkinson, R.W.; Brook, J.R.; Chang, H.H.; Crouse, D.L.; Fussell, J.C.; Hoek, G.; Hoffmann, B.; Kappeler, R.; et al. Long-Term Exposure to Traffic-Related Air Pollution and Selected Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environ. Int. 2022, 164, 107262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anenberg, S.C.; Haines, S.; Wang, E.; Nassikas, N.; Kinney, P.L. Synergistic Health Effects of Air Pollution, Temperature, and Pollen Exposure: A Systematic Review of Epidemiological Evidence. Environ. Health 2020, 19, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vachon, J.; Kerckhoffs, J.; Buteau, S.; Smargiassi, A. Do Machine Learning Methods Improve Prediction of Ambient Air Pollutants with High Spatial Contrast? A Systematic Review. Environ. Res. 2024, 262, 119751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Li, Y.; Gao, J.; Bao, F. A New Coupling Method for PM2.5 Concentration Estimation by the Satellite-Based Semiempirical Model and Numerical Model. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKie, R.E. Chapter 25: Climate Change Governance, Environment, and Inequality in Latin America. In Handbook on Inequality and the Environment; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2023; ISBN 978-1-80088-113-6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.