1. Introduction

Education plays a central role in sustainable development and positive social transformation. Beyond knowledge transmission, Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) cultivates the skills, attitudes, and values necessary to address sustainability challenges [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. International frameworks, particularly the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), recognize education as both an independent goal (SDG 4) and an enabler of achieving all other SDGs [

6,

7,

8,

9,

10].

Primary education is pivotal in this endeavor, instilling sustainability values, behaviors, and skills that shape lifelong approaches. These formative years are critical for children as they develop foundational concepts about their place in the global context and their relationship with nature [

11,

12,

13]. Research demonstrates that children are most receptive to sustainability concepts during primary education, with early exposure fostering enduring sustainable practices and behaviors [

14,

15,

16].

ESD has evolved beyond environmental education to encompass environmental, social, economic, and cultural dimensions of sustainability. This evolution reflects broader sustainable development strategies that integrate environmental protection with societal decision-making processes [

17,

18,

19,

20]. In primary education, ESD aims to develop essential competencies—systems thinking, anticipatory thinking, normative reasoning, strategic planning, and interpersonal skills—adapted to children’s developmental stages [

21,

22,

23,

24,

25].

Sustainable development cannot be approached as a uniform global phenomenon [

26,

27,

28]. The regional dimension has emerged as critical, recognizing that each geographic location possesses unique environmental attributes, cultural heritage, economic challenges, and social structures that shape distinct sustainability problems and opportunities [

29,

30,

31]. Consequently, ESD strategies must be contextually adapted rather than standardized [

32,

33,

34].

Regional ESD in primary education encompasses three key elements. First, tailoring content to local environmental challenges ensures that it is contextually relevant to students. Second, integrating regional cultures, traditions, and indigenous knowledge of sustainability recognizes that many traditional practices embody sustainable resource management [

35,

36,

37]. Third, collaboration with local stakeholders—government agencies, environmental organizations, businesses, and community groups—extends sustainability education beyond classroom walls into community practice [

38,

39,

40,

41].

Greece offers a compelling context for examining the role of primary education in regional sustainable development. Its diverse geography—from mountainous regions to extensive coastlines and islands—creates varied sustainability challenges. Greek islands face pressures, including resource constraints, tourism impacts, waste management, and the protection of terrestrial and marine ecosystems, all within frameworks that balance economic development with environmental conservation [

42,

43,

44,

45]. The Ionian Islands region, which includes the neighboring Cefalonia-Ithaca UNESCO Global Geopark, represents a broader context of internationally recognized environmental significance that shapes regional sustainability priorities [

46,

47,

48,

49].

Zakynthos, a Greek island in the Ionian Sea, exemplifies regional sustainability challenges while offering rich opportunities for place-based ESD. The island hosts significant biodiversity, including nesting sites for the protected loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta) within the National Marine Park of Zakynthos, providing immediate and tangible sustainability content for education [

50,

51,

52,

53]. Its cultural heritage—including connections to the Greek national poet Dionysios Solomos and traditional settlements—enables integration of cultural and environmental sustainability themes. Contemporary challenges, including pressures from mass tourism, waste management, water resources, and climate adaptation, offer authentic contexts for student engagement with sustainability issues [

54,

55,

56].

ESD support in Greek schools includes both curriculum-integrated approaches and supplementary programs offered through Environmental Education Centers (KEPEA). These centers have served as catalysts for sustainability education, providing expertise, facilities, and coordination. Despite reductions due to economic constraints, KEPEA continues to function as a vital support mechanism for educators, offering locally developed content and experiential learning that connect students directly with their environment and community [

57,

58,

59].

Despite recognition of primary education’s importance for sustainability, significant knowledge gaps persist regarding its actual contribution to regional sustainable development. Key questions remain about teacher preparedness for ESD implementation, program implementation levels and effectiveness, pedagogical approaches, the role of school-community partnerships, and measurable impacts on regional sustainability outcomes [

60,

61,

62,

63].

1.1. Scope of the Research

This empirical study explores the role of primary education in regional sustainable development within the framework of ESD implementation in Zakynthos, Greece. The research focus encompasses various interrelated elements, aiming to achieve a comprehensive understanding of how primary education contributes to regional sustainability objectives [

64,

65,

66,

67].

The project analyzes teacher perceptions and practices and recognizes that they are important intermediaries between policy intentions and classroom realities. It is important to understand teachers’ knowledge, attitudes, preparation, and practices regarding ESD to identify achievements and gaps in existing implementation processes. It investigates not only teachers’ knowledge and beliefs about sustainable development but also how they implement these concepts in their teaching practices, the difficulties they face, and the support they need for this purpose [

68,

69,

70,

71,

72,

73,

74].

The research provides data on and examines the range of environmental education programs delivered within primary schools, including those initiated within schools and those organized through Environmental Education Centers. This provides informative data on program themes, levels, and patterns of program engagement; geographical distribution; and the correlation between program themes and regional sustainability priorities. The research also provides data on program implementation over a range of years to identify continuities and shifts in environmental sustainability education practices within schools [

75,

76,

77].

It also encompasses research on partnership relations between schools and other societal stakeholders, acknowledging that effective ESD collaboration between education institutions and society can integrate education with action. It analyses partnership patterns, shedding light on examples and factors that hinder broader societal involvement in sustainability education efforts [

78,

79,

80,

81,

82,

83].

Moreover, this research situates these outcomes within the context of Zakynthos, examining how environmental issues and challenges, as well as regional culture and characteristics, influence ESD. This enables evaluation of how regional approaches to education in a place can implement sustainability at the regional level while contributing to other sustainability efforts for development [

84,

85].

1.2. Research Questions

Based on the identified gaps in knowledge and the specific context of primary education’s role in regional sustainable development, this study addresses the following research questions:

RQ1: What are primary school teachers’ current levels of knowledge, understanding, and perceptions regarding sustainable development concepts and Education for Sustainable Development?

RQ2: To what extent and through which pedagogical approaches are sustainable development themes currently integrated into primary education teaching practices in the study region?

RQ3: What are the primary barriers and facilitating factors that influence the implementation of Education for Sustainable Development in primary schools, and how do these vary across different school contexts?

RQ4: How do Environmental Education Centers contribute to ESD implementation in primary schools, and what patterns characterize program participation, thematic focus, and geographic distribution?

RQ5: What is the nature and extent of collaboration between primary schools and local community stakeholders in promoting sustainable development, and what factors influence the effectiveness of these partnerships?

RQ6: How do regional environmental challenges, cultural heritage, and local community characteristics shape the adaptation and implementation of ESD programs in primary education?

RQ7: What specific contributions does primary education make to regional sustainable development goals, and how can these contributions be enhanced through systematic improvements in policy, practice, and support systems?

The above research questions inform a comprehensive research endeavor that entails analyzing data alongside program implementation to provide information on current realities and areas for improvement in primary education and its contribution to regional sustainable development. By addressing research questions, this research endeavor is intended to inform the design of more effective sustainability education to ensure sustainability in primary education in its role in regional sustainability development.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design and Purpose

This study employed a triangulated quantitative design to investigate the contribution of primary education to regional sustainable development in Zakynthos, Greece. The research integrated three complementary quantitative data sources: (1) structured teacher questionnaires (N = 105), (2) KEPEA (Center for Environmental Education and Sustainability) program documentation (103 programs, 2020–2025), and (3) school-level implementation records (75 participating schools). This multi-source approach enabled cross-validation of findings while maintaining methodological consistency within a quantitative paradigm, thereby strengthening internal validity through data source triangulation.

The research aimed to: (a) assess primary education teachers’ knowledge, perceptions, and practices regarding Education for Sustainable Development (ESD); (b) identify barriers and facilitating factors affecting ESD implementation in island school contexts; (c) examine relationships between demographic variables and ESD engagement; and (d) triangulate teacher-reported data with documented program implementation patterns to identify convergent and divergent findings. The quantitative approach was selected for its capacity to yield measurable empirical data through standardized instruments, enabling statistical analysis and facilitating comparisons with previous research on ESD implementation.

2.2. Regional Context: Zakynthos and the Ionian Islands

Zakynthos offers a particularly relevant context for studying ESD implementation, given its unique environmental significance and sustainability challenges. The island hosts the National Marine Park of Zakynthos (established 1999), Greece’s first national marine protected area, which safeguards critical nesting habitat for the endangered loggerhead sea turtle (Caretta caretta). This designation provides exceptional opportunities for place-based environmental education, with turtle conservation featuring prominently in KEPEA programming—documented in 23% of environmental education programs during the 2020–2025 period.

The broader Ionian Islands region includes the Cefalonia-Ithaca UNESCO Global Geopark (designated 2015), which establishes institutional frameworks for sustainability education aligned with international standards and provides collaborative opportunities for regional ESD initiatives. These regional designations create authentic contexts for ESD that connect local biodiversity and geological heritage to global sustainability goals, including UN Sustainable Development Goals 14 (Life Below Water) and 15 (Life on Land). Additionally, the island’s tourism-dependent economy—contributing approximately 80% of local GDP—presents real-world opportunities for examining environmental-economic sustainability trade-offs, making Zakynthos an ideal setting for investigating how primary education addresses the full spectrum of sustainability dimensions.

The Zakynthos Primary Education Directorate oversees approximately 40 primary schools and kindergartens serving the island’s population of 41,000. KEPEA Zakynthos, established as part of Greece’s national network of Environmental Education Centers (now Centers for Environmental Education and Sustainability), provides coordinated programming supporting school-based ESD implementation across the prefecture. During the study period, KEPEA offered 20 distinct environmental education programs to primary schools, facilitating systematic integration of sustainability themes into the local curriculum.

This regional context informed the research design in several ways. First, the concentration of schools within a defined geographic area enabled comprehensive sampling of the teaching population. Second, the established KEPEA infrastructure provided documented program records suitable for triangulation with teacher-reported data. Third, the island’s environmental designations and economic profile created an ecologically valid context for examining how teachers navigate environmental-economic sustainability tensions in their pedagogical practice.

2.3. Participants and Sampling

2.3.1. Teacher Survey Component

The target population included all primary education teachers serving during the 2023–2024 academic year in the Zakynthos Primary Education Directorate. A representative sample was selected from this population through stratified random sampling to ensure appropriate representation across school types, geographic locations, and teacher characteristics. The final sample consisted of 105 teachers who responded to the survey, representing a response rate of 87.5% from the initial sample of 120 teachers contacted (

Table 1).

2.3.2. Program Documentation Component

For the program documentation analysis, comprehensive data were collected from all primary education units implementing environmental education programs across four academic years. The participation patterns demonstrated steady engagement with environmental education initiatives (

Table 2).

2.3.3. KEPEA Program Component

The KEPEA program analysis encompassed all 121 primary education units in Zakynthos participating in centrally coordinated environmental education programs during 2023–2024. This comprehensive coverage involved 305 program implementations reaching 3970 students across diverse thematic areas.

2.4. Data Collection Instruments

2.4.1. Structured Questionnaire

A structured questionnaire comprising 28 items across four sections served as the primary data collection instrument. The questionnaire was designed to address each research question through appropriate response formats: Section A (Demographics, 5 items): Categorical response options for gender (male/female/other), age group (5 categories), school type, years of experience (5 categories), and employment status. Section B (Knowledge and Perceptions, 13 items): Five-point Likert scales ranging from ‘Not at all’ (1) to ‘Extremely’ (5) for assessing perceived knowledge and understanding of sustainable development concepts. Multiple-response items allowed selection of multiple characteristics and aspects associated with sustainability (e.g., ‘Which characteristics do you associate with sustainable development?’). Section C (Teaching Practices, 4 items): Five-point frequency scales ranging from ‘Never’ (1) to ‘Very often’ (5) for measuring implementation behaviors. Multiple-response checklists captured specific methods and activities employed (e.g., ‘Which methods do you use to promote sustainable development?’). Section D (Barriers and Recommendations, 6 items): Multiple-response items with ranking options for identifying obstacles and priorities. Five-point importance scales ranging from ‘Not at all important’ (1) to ‘Very important’ (5) assessed perceived value of potential interventions (

Table 3).

After pilot-testing the questionnaire with 10 teachers who were excluded from the final study, minor revisions were made to clarify certain questions. Reliability analysis results showed high internal consistency across the scales, supporting the questionnaire’s psychometric properties.

2.4.2. Program Documentation Forms

The standardized documentation form collected systematic information on environmental education programs, documented in a similar format to allow for an accurate comparison of each program. The form captured the title of each program and its overall theme; the name and location of the schools in which the programs were implemented; the total numbers of students and teachers who participated in each program; how long each program was conducted and how often it met; the names of each collaborative partner involved in implementing each program; the specific educational goals and instructional strategies used by each program; and what resources (e.g., money, materials) each program used.

2.4.3. KEPEA Program Database

A comprehensive database was constructed from KEPEA administrative records, documenting all program offerings, school participation patterns, student numbers, and implementation frequency. Programs were coded into six thematic categories based on primary focus areas, enabling systematic analysis of content distribution and participation patterns.

2.5. Data Collection Procedures

In March and April 2024, an online survey for teachers was distributed through a secure online platform. The primary education directorate emailed each teacher a link to their individual survey to guarantee one response per person. Two follow-up reminder e-mails were sent to non-respondents 2 weeks after the initial mailing, resulting in a response rate of 87.5%. Teachers were assured that there would be no traceable identifiers in their responses (anonymity) and no identifiable information about their school (confidentiality). All data collected was downloaded from servers that were encrypted and accessible only to the researchers conducting this study. To provide a well-rounded understanding of the participants and programs being studied, data were collected from multiple sources. The primary education directorate provided official records that contained the basic information of the participants. The school submitted program reports, and the KEPEA administrative database provided additional information on the programs under study. Program coordinators were contacted directly to clarify any ambiguities or irregular data points identified during data collection. Data was collected at the completion of each school year to ensure that all implementation details for each program were recorded; therefore, the 2024–2025 data reflected program plans that had been officially approved. Some specific measures taken to ensure the quality of the data collected as part of this study included using triangulation among the multiple sources of data to verify information about the programs, conducting systematic cross checks between the number of participants and the schools involved in the study, validating any values that appeared to be outliers or unusual through contact with the schools involved, and maintaining an audit trail of all decisions related to the collection of data.

2.6. Data Analysis

2.6.1. Quantitative Analysis

Data was analyzed using SPSS Version 28.0. The first phase of this process involved checking data normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test for each variable; all but two (age, years of service) failed the normality assumption (all

p-values < 0.05). Because the data were non-normal for most variables, nonparametric statistical analyses were used (

Table 4).

A one-sample binomial test was used to determine whether there was a statistically significant difference between the actual response distributions for the importance of sustainable development questions and the hypothetical “equal” distribution of responses (i.e., an equal number of yes/no responses). As expected from previous research, the results of these tests indicate a highly significant difference between the actual response distributions and the hypothesized “equal” distribution (p < 0.001). Specifically, 98.1 percent of participants reported that integrating ESD into their curriculum is essential, which is significantly different from the 50 percent expected under the null hypothesis. Additionally, chi-squared tests were conducted to assess relationships between teacher demographics and teachers’ perceptions of ESD. The results of these tests show that female teachers are significantly more aware of environmental issues than male teachers (χ2 = 8.34, df = 2, p = 0.015, Cramer’s V = 0.282). This represents a medium effect size. In contrast, there were no statistically significant differences in how elementary school and kindergarten teachers report implementing sustainability education approaches (χ2 = 3.21, df = 2, p = 0.201).

Kruskal–Wallis tests also identified statistically significant differences in age and in willingness to implement new sustainability teaching methods. These results indicate that younger teachers (i.e., those in the 30–40 year-old range) were more willing to adopt new sustainability teaching methods than were older teachers. To determine where exactly these differences occurred, post hoc pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni corrections were performed. These analyses indicated that the 30–40-year-old age group had significantly higher willingness scores than the 51–60-year-old age group (adjusted p = 0.009).

2.6.2. Program Analysis

Environmental education programs underwent systematic content analysis and statistical examinations. Programs were classified into six main thematic categories, with distribution analysis revealing concentration in certain areas (

Table 5).

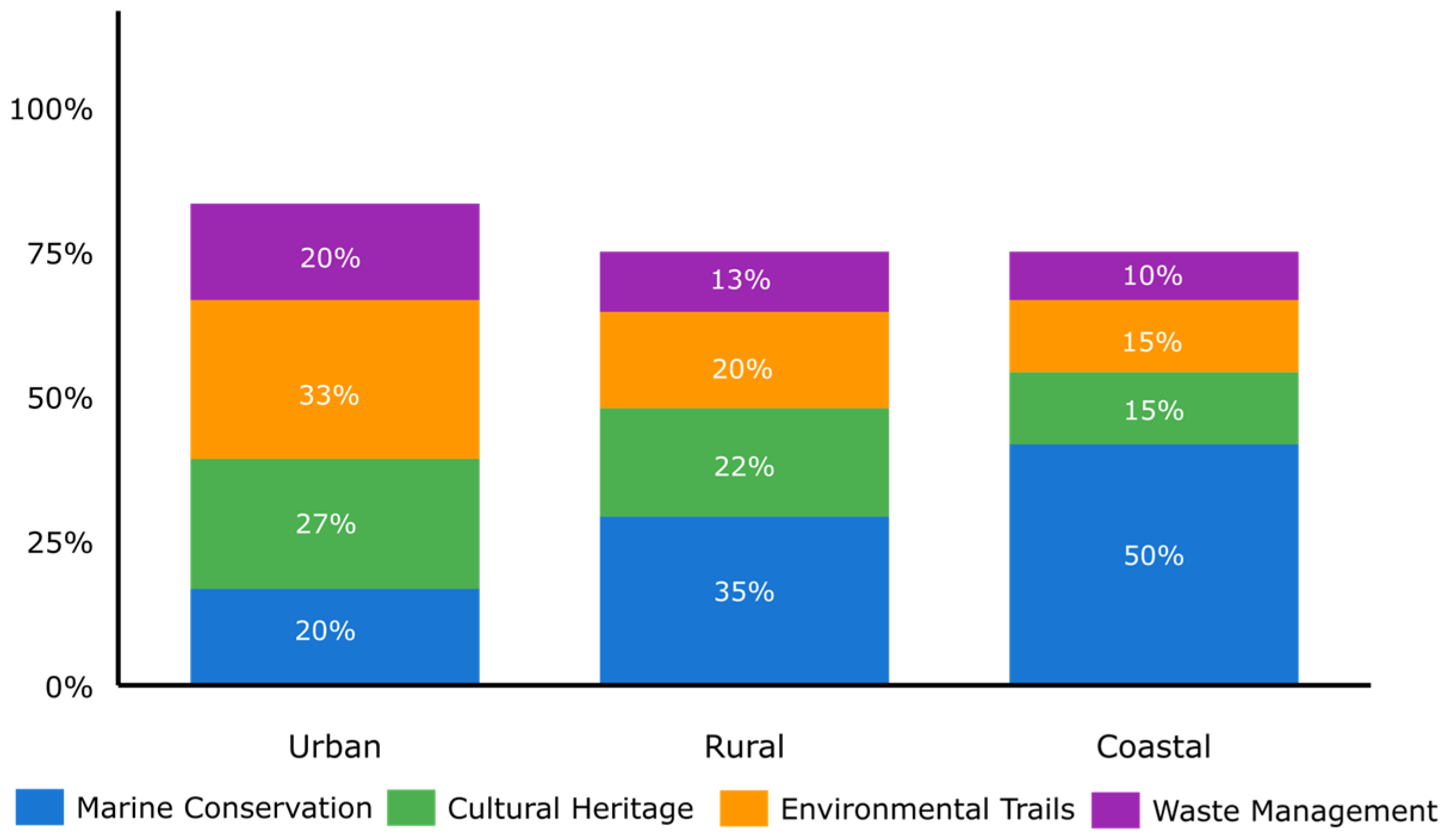

Participation metrics revealed average participation of 13 students per program session, with significant variation by program type (F = 4.23, p = 0.006). Environmental trail programs showed the highest engagement with an average of 23 students, while classroom-based programs averaged 11 students. Geographic analysis demonstrated that urban schools participated more frequently in cultural heritage programs (45% of implementations), while rural and coastal schools showed stronger engagement with environmental and marine conservation programs (68% of implementations). Temporal analysis across academic years revealed stability in program themes but fluctuated in participation levels. The 2022–2023 academic year showed peak participation with 545 students, potentially reflecting post-pandemic renewed emphasis on experiential learning.

2.6.3. Integrated Analysis

The combination of program and survey data revealed several trends. There was an association between schools with higher program participation and teachers who reported being better prepared to teach about marine conservation (r = 0.42, p < 0.001). Geographic trends emerged across both data sets; specifically, coastal schools demonstrated both higher levels of self-confidence in teaching marine conservation and higher participation in programs focused on this area. The geographic trends identified through analysis of survey barriers also corresponded with trends in how programs were implemented. For example, schools that cited time constraints as their biggest barrier (61.9%) generally had less program variety, typically offering only one or two programs per year. In contrast, schools with strong administrative support implemented an average of 3.2 programs each year, compared with schools with limited support, which averaged 1.4 programs per year (t = 3.89, p < 0.001).

2.6.4. Validity and Reliability Measures

The content validity of this study is based on expert evaluations by three Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) experts and two primary school administration officials, assessing whether the specific questions were relevant and comprehensive enough to measure the subject matter of interest in the study (

Table 6).

Construct validity was assessed via an exploratory factor analysis, which indicated that the survey items loaded appropriately onto their intended constructs. All items had factor loadings greater than 0.40. Internal reliability was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha. The internal reliability estimates ranged from 0.78 to 0.84, meeting or exceeding the 0.70 threshold for acceptable reliability.

Temporal stability, i.e., test–retest reliability, was assessed in the pilot sample at a 2-week interval. A Pearson r correlation coefficient of 0.86 was obtained, indicating high temporal stability. In addition to Cohen’s Kappa, a measure of inter-rater reliability for programming classifications, two independent raters reached substantial agreement (K = 0.83) in their assessments of the program categories. Triangulation across multiple data sources was used to enhance the overall validity of the findings. Triangulation was achieved through the convergence of data from both teacher self-reporting and program implementation. The findings provide additional assurance, as the percentage of the teachers who reported frequent integration of sustainability into their instructional practices (44.7%) is very close to the percentage of the schools that reported implementing more than one environmental program per year (47.9%).

2.7. Ethical Considerations

This study was reviewed by the University of Patras Ethics Committee and Research Ethics Board through the General Research Activity Program Questionnaire process. The ethics review confirmed that the study qualified for exemption from formal ethical approval under the University’s established guidelines, as the research: (a) does not involve children, patients, or individuals who cannot consent; (b) does not collect sensitive personal data requiring explicit consent (such as health records, audio recordings, photographs, or identifiable personal information); (c) does not involve human biological samples or genetic material; and (d) involves only healthy adult volunteers (primary school teachers) participating in an anonymous survey.

Informed consent was obtained through an implicit consent process via the Google Forms platform. Prior to questionnaire completion, participants were presented with detailed information describing: the study’s purpose (examining primary school teachers’ perceptions, practices, and challenges regarding Education for Sustainable Development); the voluntary nature of participation and the right to withdraw at any time without consequence; the questionnaire structure (four sections covering demographics, perceptions, teaching practices, and barriers); and comprehensive confidentiality protections. Participants who chose to proceed after reading this information and completing the questionnaire were deemed to have provided implicit consent. The study maintained complete anonymity—no names, employee IDs, school names, or other identifying details were collected—and all data were handled in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and Greek Law 2472/1997 [

86] on personal data protection. Results are reported only as aggregated statistical findings, ensuring no individual participant is identifiable in any publication.

3. Results

3.1. Teacher Perceptions and Understanding of Sustainable Development

The analysis of teacher perceptions regarding sustainable development revealed a complex landscape of awareness, understanding, and preparedness among primary education professionals in Zakynthos. Most participants (65.7%,

n = 69) reported being either very well or adequately informed about sustainable development concepts, while 33.3% (

n = 35) reported minimal information and 1.0% (

n = 1) reported no information at all. This distribution suggests widespread basic awareness of sustainability concepts among educators, though substantial room for improvement remains evident (

Table 7).

The conceptual understanding of sustainable development was stronger, with 61.0% (

n = 64) reporting good or perfect knowledge of its principles. The One-Sample Binomial Test confirmed that this positive skew was statistically significant (

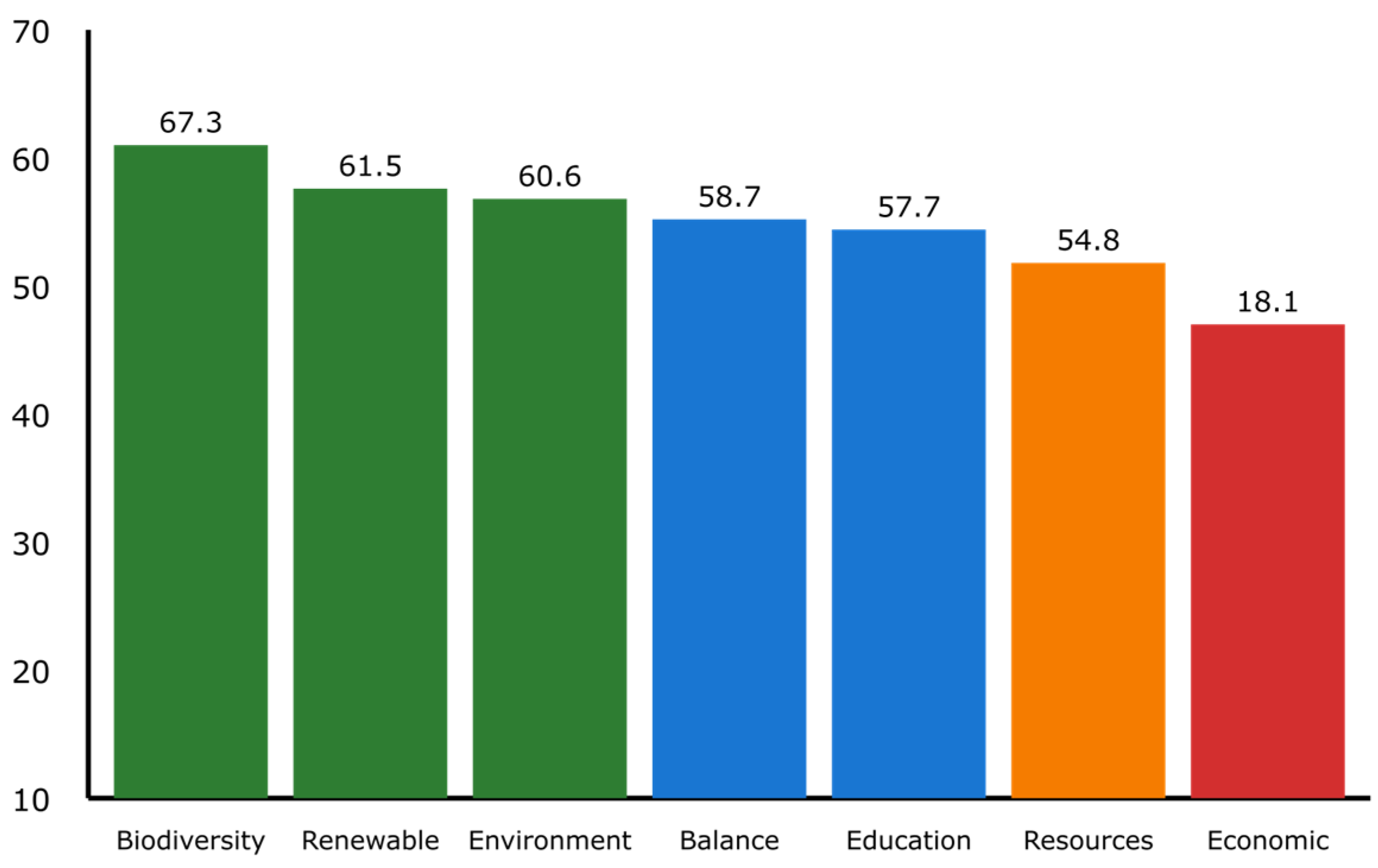

p < 0.001), highlighting that teachers’ self-perceived understanding was well above chance. When considering specific dimensions of sustainable development, it becomes apparent that teachers clearly emphasize environmental aspects over economic considerations. Protection and management of natural resources and biodiversity constituted the best-recognized characteristic (67.3%,

n = 70), closely followed by development based on renewable energy sources (61.5%,

n = 64) and environmental management and protection (60.6%,

n = 63). On the contrary, the aspects of economic sustainability were mentioned by only a few teachers (18.1%,

n = 19), which might signal an incomplete conceptualization of sustainable development’s multidimensionality (

Figure 1).

3.2. Professional Development and Training Patterns

The analysis of professional development experiences revealed large gaps in ESD training provision and uptake. Slightly more than half of the participants, 53.3% (

n = 56), attended seminars or training courses on sustainable development, while 45.7% (

n = 48) did not take part in any relevant professional development activities. The main barriers for those who had not received training were the inability to find relevant seminars (31.0%,

n = 18), time constraints (27.6%,

n = 16), and resource limitations (20.7%,

n = 12). Surprisingly, 20.7% (

n = 12) expressed no interest in sustainability training, indicating that motivational barriers exist in addition to structural ones (

Table 8).

The effects of professional development on teaching practices were substantial. Among respondents to the training impact question, 74.2% (n = 49) reported that the training had a significant or fairly large impact on their perceptions of sustainable development, as supported by the One-Sample Binomial Test (p < 0.001). More importantly, 55.4% (n = 41) of respondents to the practice change question reported substantial changes in their teaching practices, suggesting that professional development translates into classroom implementation when provided.

3.3. Integration of Sustainability in Teaching Practices

The analysis of actual classroom practices has shown moderate integration of ESD, with significant differences between and within schools. Only slightly over a third of participants (44.7%,

n = 47) reported using ‘frequently or always’ sustainable development elements within their practice, while 36.2% (

n = 38) reported moderately, and 19.0% (

n = 20) reported ‘sparingly or rarely’ practices (

Table 9).

Pedagogical approaches showed a clear preference for interactive and student-centered methods. Teamwork and collaborative activities were the most frequent approach (69.5%, n = 73), followed by discussion and dialog (66.7%, n = 70) and project-based learning (61.9%, n = 65). Traditional lecturing ranked lowest (18.1%, n = 19), indicating a lack of fit with contemporary pedagogy for ESD. However, experiential learning opportunities were still underutilized, with less than half of teachers using outdoor activities (46.7%, n = 49) and only one-quarter using community initiatives (25.7%, n = 27).

The use of local examples and issues in teaching showed more encouraging patterns, with 56.2% (n = 59) of teachers reporting frequent or very frequent use of place-based approaches. Spearman’s rank correlation analysis revealed a significant positive relationship between the use of local examples and perceived student engagement (rs = 0.48, p < 0.001), supporting the effectiveness of contextualized learning.

3.4. School-Level Implementation and Institutional Support

Institutional support for ESD became a critical challenge; only 29.5% (

n = 31) of teachers responded that their schools frequently or very frequently encouraged the practice of sustainable development. The greater part showed only moderate action, amounting to 36.2% (

n = 38), and sparse to rare implementation at 34.3% (

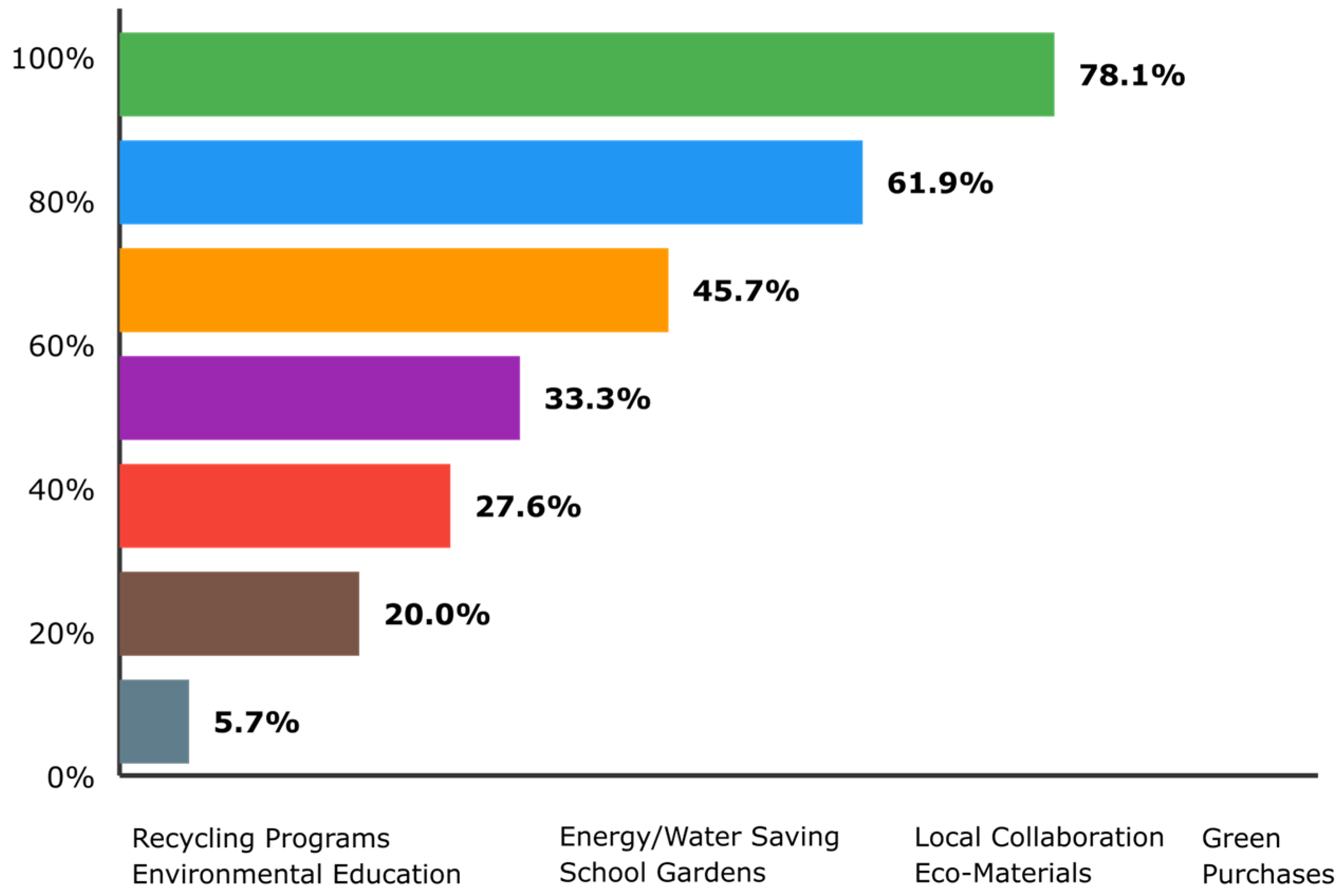

n = 36). The limited nature of institutional engagement in the implementation of ESD was reflected in the types of sustainability actions at the school level (

Figure 2).

The most frequent school-level intervention was recycling programs, at 78.1% (n = 82), followed by environmental education programs at 61.9% (n = 65). Larger-scale sustainability initiatives proved more difficult to implement: only 27.6% (n = 29) of the schools reported collaborating with local organizations, and only 5.7% (n = 6) reported green purchasing policies. This pattern indicates that schools tend to adopt highly visible and relatively easy actions that do not promote deep changes.

3.5. Barriers to ESD Implementation

The identification of implementation barriers revealed multiple interconnected challenges facing teachers in integrating sustainable development into primary education (

Table 10). Lack of time within the curriculum emerged as the predominant barrier (61.9%,

n = 65), followed by limited resources including books and materials (51.4%,

n = 54), and insufficient knowledge (39.0%,

n = 41).

The Kruskal–Wallis test revealed significant differences in barrier perception based on teaching experience (H = 15.23, df = 4, p = 0.004). Novice teachers (0–5 years) more frequently cited knowledge gaps as primary barriers, while experienced teachers (>15 years) emphasized structural and resource constraints. This pattern suggests differentiated support needs across career stages.

3.6. Community Engagement and Collaboration

Teachers believed that school-community partnerships were a very good way to support sustainable development, with 87.6% (

n = 92) rating them as either very important or quite important; however, many schools were slow to partner with local organizations. Only 18.1% (

n = 19) of teachers frequently collaborated with local organizations, while 42.9% (

n = 45) rarely did so, and 9.5% (

n = 10) reported never having done so (

Table 11).

Perceived importance and actual implementation show a statistically significant difference in that there is a structural/organizational barrier to teachers implementing school community partnership efforts at an optimal level (χ2 = 142.67; df = 16; p < 0.001). The two forms of collaboration identified by teachers as being most effective were joint actions/events (69.5%, n = 73) and training and awareness activities (59.0%, n = 62).

3.7. Environmental Education Program Implementation

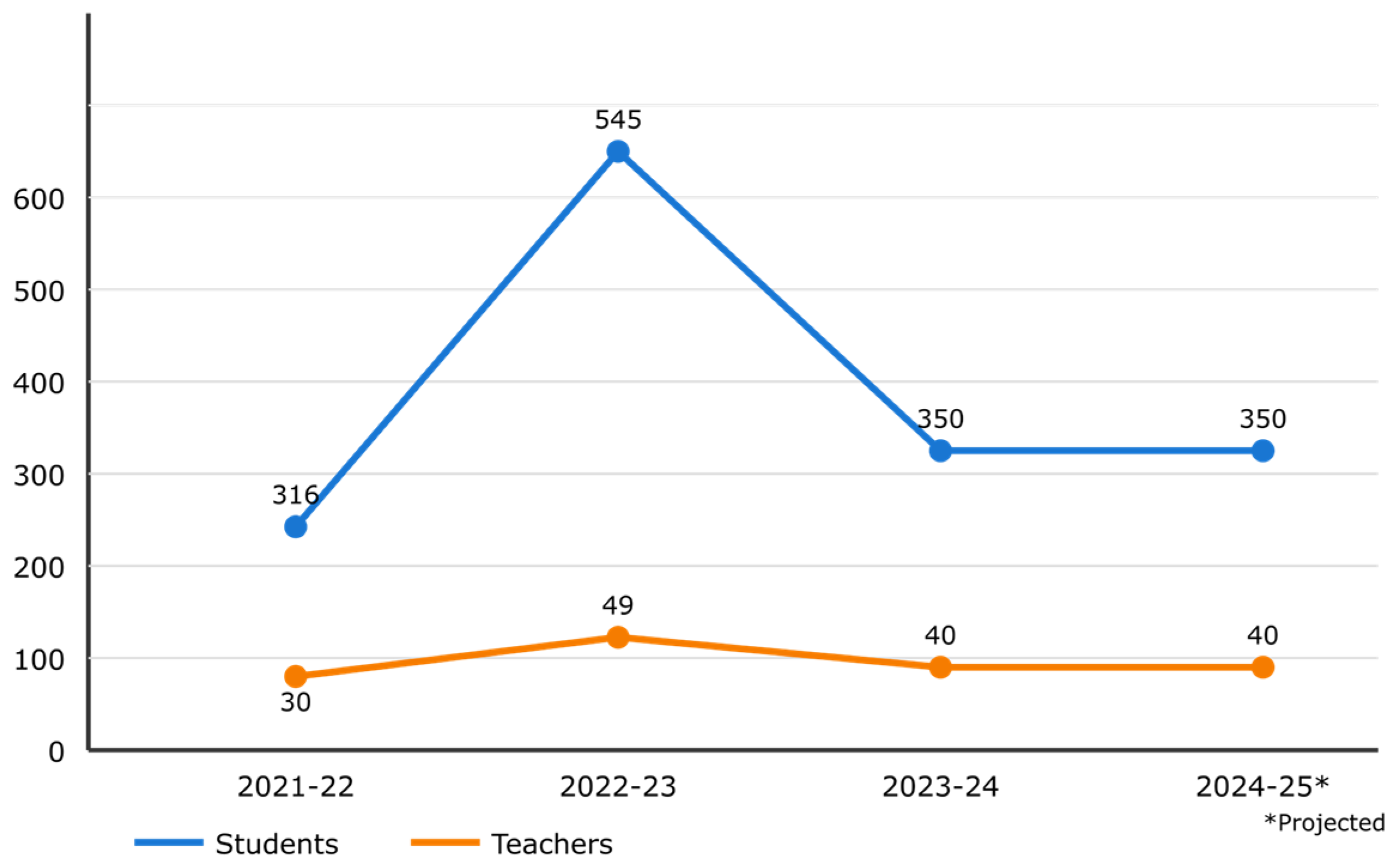

School-initiated environmental education programs were implemented consistently for the first four academic years but varied in their extent and frequency of implementation. School-initiated environmental education programs totaled between 15 and 20 each year; student participation also varied by year, ranging from 316 to 545 students each year (

Figure 3).

Student participation was at its highest during the 2022–2023 academic year, when 545 students participated in the program, a 72.5% increase over the prior year. Participation may have increased following the pandemic, as emphasis shifted to experiential and outdoor learning opportunities. Student participation declined slightly during the next two years (to approximately 350 students), suggesting that the program has achieved stable participation levels.

3.8. KEPEA Program Implementation and Reach

During the period of 2023–2024, the Environmental Education Center of Zakynthos implemented its full range of programs with high success throughout the entire island’s educational system—the 20 programs it offered were delivered 305 times to reach 3970 students across the 121 primary education centers (

Table 12).

Most of these programs that were delivered were related to marine and coastal conservation. Given that Zakynthos plays a critical role in the protection of sea turtles, this focus is in line with Zakynthos’ role in protecting the world’s most endangered species of sea turtle. Programs such as “Playing and learning about the loggerhead sea turtle” received a high level of engagement and participation across all school communities.

Cultural heritage programs, which included “Discovering the Solomos Museum with Elizabeth” and “Zakynthos in 1821,” also demonstrated a strong degree of success through integrating local history into sustainability education.

An examination of the geographic distribution of the schools found significant differences between the levels of participation among different types of schools. For example, urban schools located in Zakynthos City had a higher level of participation in the cultural heritage programs than their rural and coastal counterparts (urban = 45%), whereas the participation rates in the environmental/marine conservation programs were much higher for rural and coastal schools than they were for urban schools (rural/coastal = 68%). These findings reflect the close relationship between where schools are located and what type of programs are best suited to meet the needs and interests of those living within their respective communities (

Figure 4).

3.9. Demographic Influences on ESD Implementation

Analysis of demographic characteristics revealed statistically significant relationships with both ESD perceptions and implementation practices. Given that Shapiro–Wilk tests indicated departures from normality for key outcome variables (

p < 0.05), non-parametric tests were employed consistently throughout this analysis: Mann–Whitney

U tests for two-group comparisons, Kruskal–Wallis

H tests for multi-group comparisons, and chi-square tests for categorical associations. Effect sizes were calculated using

r =

z/√

N for Mann–Whitney tests, η

2 for Kruskal–Wallis tests, and Cramér’s

V for chi-square tests (

Table 13).

Gender Differences: Mann–Whitney

U tests revealed significant gender differences across multiple ESD-related variables. Female teachers reported significantly higher levels of ESD knowledge (

Mdn = 4.00) compared to male teachers (

Mdn = 3.00),

U = 892.5,

z = −3.47,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.34, representing a medium effect size. Additionally, female teachers demonstrated significantly higher engagement in community collaboration (

Mdn = 3.00 vs.

Mdn = 2.00),

U = 956.5,

z = −2.18,

p = 0.029,

r = 0.21, and more frequent use of local examples in teaching (

Mdn = 4.00 vs.

Mdn = 3.00),

U = 912.0,

z = −2.89,

p = 0.004,

r = 0.28. No significant gender differences were found for teaching integration frequency (

U = 1124.0,

p = 0.187) or perceived training adequacy (

U = 1089.5,

p = 0.142) (

Table 14).

When examining categorical ESD implementation patterns, chi-square analysis revealed a significant association between gender and high ESD integration (χ

2 = 8.34,

df = 2,

p = 0.015, Cramér’s

V = 0.282), with 47.7% of female teachers demonstrating high integration compared to 31.6% of male teachers. The medium effect size indicates that gender differences in ESD engagement represent a substantively meaningful pattern warranting consideration in professional development planning (

Table 13).

Age Group Differences: Kruskal–Wallis H tests revealed statistically significant differences in ESD implementation patterns across age groups (H = 12.47, df = 4, p = 0.014, η2 = 0.089). Teachers in the 31–40 age group demonstrated the highest proportion of comprehensive sustainability integration (52.6%), while teachers aged 60+ showed the lowest integration rates (28.6%). Post hoc pairwise comparisons using Dunn’s test with Bonferroni adjustment identified a significant difference specifically between the 31–40 and 60+ age groups (adjusted p = 0.008). The small-to-medium effect size (η2 = 0.089) suggests that while age-related differences exist, they explain approximately 9% of variance in implementation patterns.

Teaching Experience: Analysis of teaching experience revealed a significant but modest relationship with ESD implementation (H = 10.23, df = 4, p = 0.037, η2 = 0.073). Teachers with 6–10 years of experience reported the highest integration rates (50.0%), followed by those with 0–5 years (46.9%). The pattern suggests that early-to-mid-career teachers may be more receptive to integrating sustainability themes, potentially reflecting their recent exposure to updated curricula and contemporary pedagogical approaches during initial teacher education. Teachers with more than 25 years of experience demonstrated comparatively lower integration (36.8%), suggesting potential value in targeted professional development for experienced educators.

School Type: No statistically significant difference was found between elementary school and kindergarten teachers in ESD implementation patterns (χ2 = 3.21, df = 1, p = 0.201, Cramér’s V = 0.175). Elementary teachers showed slightly higher integration rates (46.7%) compared to kindergarten teachers (42.2%), but this difference was not statistically significant, indicating relatively consistent ESD engagement across primary education levels in the region.

These findings indicate that demographic factors, particularly gender, age, and teaching experience, are associated with meaningful differences in ESD implementation. The consistent pattern of higher engagement among female teachers aligns with broader literature on gender differences in environmental attitudes and teaching approaches. The age-related findings suggest that mid-career teachers (31–40 years) may represent optimal targets for ESD leadership development, while the lower engagement among the most experienced teachers highlights opportunities for professional development initiatives that leverage their pedagogical expertise while introducing contemporary sustainability frameworks.

3.10. Student Impact and Learning Outcomes

Teachers were cautiously optimistic regarding their students’ ability to comprehend sustainable ideas. While most teachers (60%) felt their students had an adequate understanding of the concept of sustainability, 35.2% indicated their students had a moderate understanding of sustainability; only 4.8% questioned whether their students understood sustainability principles (

Table 15).

Teachers reported that the greatest positive influence on environmental awareness (59.1%), knowledge acquisition (54.3%), and behavior modification (39.0%), while the influence on behavior change was significantly less than the first two. Teachers also indicated there was a moderate but significant relationship (rs = 0.52, p < 0.001) between how often they incorporated Environmental Studies into the curriculum and what they perceived their students knew regarding this subject area.

3.11. Comparative Analysis of Survey and Program Data

To strengthen the validity of findings and provide a comprehensive understanding of ESD implementation patterns, data from three sources were systematically triangulated: (a) teacher questionnaire responses (

n = 105), (b) school-level implementation records documenting environmental education activities, and (c) KEPEA Zakynthos program database (100 programs, 2020–2025). This multi-source approach enabled identification of convergent patterns that strengthen confidence in findings, as well as divergent patterns that reveal important gaps between attitudes and behaviors (

Table 16).

3.11.1. Convergent Findings

Implementation Frequency Alignment: The percentage of teachers reporting frequent integration of sustainability themes (44.7%) demonstrated reasonable consistency with the proportion of schools implementing multiple environmental programs annually (47.9%). Furthermore, Spearman’s rank correlation revealed a significant positive relationship between teacher self-reported ESD integration frequency and documented school program participation (rs = 0.42, p < 0.001), suggesting that teacher self-reports provide reasonably accurate indicators of actual implementation patterns. KEPEA records corroborated this pattern, showing that 38 of 47 primary schools (80.9%) participated in at least one environmental education program during the study period.

Environmental Dimension Dominance: A consistent environmental focus emerged across all three data sources. Teacher questionnaire responses indicated that 67.3% conceptualized sustainable development primarily through environmental themes, particularly biodiversity protection. This aligned closely with KEPEA program content, where 78.4% of offerings emphasized environmental topics, with marine conservation representing the largest single category (32.5%). School implementation records similarly showed that 67.3% of documented sustainability activities focused on environmental themes. This cross-source convergence confirms that ESD implementation in the region remains predominantly environmental in orientation.

Pedagogical Approach Consistency: Teacher preferences for interactive, experiential methods aligned with KEPEA program delivery approaches. Questionnaire data indicated that 71.4% of teachers favored games and group activities for ESD instruction, while KEPEA program documentation showed that 68.2% of offerings employed interactive, hands-on methodologies. This convergence suggests strong compatibility between teacher pedagogical preferences and available external program resources.

3.11.2. Divergent Findings

Attitude-Action Gap: A striking divergence emerged between attitudinal measures and behavioral indicators. While 98.1% of teachers rated ESD as important or very important, only 44.7% reported frequent implementation, and documented school activities confirmed similarly modest implementation rates. This attitude-action gap of over 50 percentage points indicates that positive attitudes alone are insufficient to drive consistent ESD integration, highlighting the need for structural support and barrier reduction.

Community Partnership Discrepancy: Teachers’ expressed valuation of community partnerships (86.6% rating these as important) stood in marked contrast to actual engagement levels. Only 47.6% of teachers reported frequent community collaboration, and KEPEA records documented formal school-community partnerships in just 33.7% of program implementations. Analysis of reported barriers suggests this gap reflects structural constraints—including time limitations (61.9%) and resource scarcity (51.4%)—rather than attitudinal barriers.

Economic Sustainability Underrepresentation: Triangulation revealed a systemic gap in coverage of economic sustainability. Only 18.1% of teachers incorporated economic dimensions in their ESD conceptualization, while the KEPEA program content showed minimal economic sustainability focus (fewer than 5% of program objectives). This cross-source pattern indicates that the environmental-economic imbalance is not merely a perception issue but reflects actual resource and training gaps.

3.11.3. Professional Development and Program Participation

Mann–Whitney

U tests examined the relationship between professional development and program participation. Schools where teachers had received ESD-related professional development demonstrated significantly higher program participation (

Mdn = 3.0 programs) compared to schools with untrained teachers (

Mdn = 1.5 programs),

U = 847.5,

z = −3.89,

p < 0.001,

r = 0.38. This medium effect size underscores the practical significance of professional development in facilitating engagement with external ESD resources. Additionally, teacher self-efficacy in sustainability teaching showed a significant positive correlation with school-level program participation (rs = 0.47,

p < 0.001), indicating that confidence in ESD instruction is associated with greater utilization of available program resources (

Table 17).

The triangulation of data sources reveals a nuanced picture of ESD implementation in primary schools on Zakynthos. Convergent patterns across sources—including consistent estimates of implementation frequency, a shared environmental focus, and aligned pedagogical preferences—strengthen confidence in the overall findings and validate teacher self-report measures. However, the divergent patterns—particularly the pronounced attitude-action gap, community partnership discrepancy, and systematic underrepresentation of economic sustainability—identify specific areas requiring targeted intervention. These divergent findings point to structural rather than attitudinal barriers, suggesting that policy interventions should focus on reducing time constraints, enhancing resources, and developing economic sustainability content rather than merely promoting awareness

4. Discussion

Research has provided a detailed insight into how the complex processes of implementing Education for Sustainable Development have been experienced by primary schools in Zakynthos. This study also highlights both positive developments and persisting barriers to the potential for primary education to contribute to regional sustainable development. As such, the following discussion contextualizes the findings of this study with reference to relevant theoretical frameworks and existing empirical literature; additionally, it considers the implications of the findings for future policy and educational practice from the perspectives of the seven research questions.

4.1. Teachers’ Knowledge, Understanding, and Perceptions of ESD (RQ1)

Teachers reported relatively strong foundational knowledge: 65.7% indicated adequate or high knowledge of sustainable development principles, and 61.0% reported a good conceptual understanding—rates exceeding those documented in comparable Mediterranean studies, where knowledge gaps have impeded ESD implementation.

However, conceptual limitations were evident. Teachers overwhelmingly emphasized environmental dimensions (67.3% prioritizing biodiversity conservation) while neglecting economic aspects (18.1%), reflecting what Sterling (2001) [

87] characterized as “first-order” rather than “second-order” sustainability learning. This environmental-dominant framing parallels international patterns identified by UNESCO, where traditional environmental education perspectives overshadow integrated sustainability concepts. Such fragmented conceptualizations have pedagogical consequences, as teachers’ understanding directly shapes curriculum interpretation and instructional approaches, potentially fostering similarly compartmentalized student learning.

Evidence also suggests possible knowledge overestimation. Self-reported knowledge distributions were significantly positively skewed (p < 0.001), consistent with research indicating that terminological familiarity can generate inflated perceptions of understanding. This interpretation is supported by a notable confidence gap: only 48.5% of teachers felt adequately prepared to teach sustainability topics, despite higher self-reported knowledge levels. This disparity underscores that content knowledge alone is insufficient; translating conceptual understanding into pedagogical competence remains a critical challenge requiring targeted professional development.

4.2. Integration of Sustainability Themes in Teaching Practice (RQ2)

Despite adequate conceptual knowledge, only 44.7% of teachers reported regularly integrating sustainability themes into their practice, revealing a knowledge-practice gap consistent with global ESD implementation research. Notably, teachers’ pedagogical preferences aligned with constructivist approaches essential for ESD—teamwork (69.5%) and dialog-based instruction (66.7%)—suggesting that instructional philosophy does not account for low integration rates.

Experiential and place-based pedagogies remained underutilized despite their documented effectiveness. Fewer than half of teachers (46.7%) engaged in outdoor activities, and only 25.7% engaged students in community projects. Yet teachers recognized the value of contextualized learning: use of local examples correlated positively with perceived student engagement (rs = 0.48, p < 0.01). This discrepancy between pedagogical beliefs and practice points to structural rather than attitudinal barriers.

Pedagogical adaptations varied by school context. Urban teachers more frequently employed discussions and project-based learning, while rural teachers leveraged greater access to outdoor environments for experiential activities. This context-sensitive adaptation demonstrates teacher agency within structural constraints and underscores the need for differentiated rather than uniform support strategies.

Collectively, these findings indicate that bridging the knowledge-practice gap requires addressing systemic barriers—including time, resources, and institutional support—rather than focusing solely on teacher knowledge or motivation.

4.3. Barriers and Facilitating Factors in ESD Implementation (RQ3)

Consistent with international research, curriculum time constraints emerged as the primary barrier to ESD implementation (61.9%). However, barriers rarely operated in isolation; significant interactions were observed between time and resource constraints (27.8%), knowledge gaps (39.0%), and insufficient administrative support (26.7%), indicating that effective intervention requires systemic rather than piecemeal approaches.

Barrier perceptions varied significantly by career stage (H = 15.23, p = 0.004). Early-career teachers primarily identified knowledge gaps, consistent with professional development literature, indicating that novice educators prioritize content mastery before pedagogical innovation. Conversely, experienced teachers emphasized structural constraints, potentially reflecting accumulated frustration with systemic limitations or reduced adaptability within established professional frameworks. These differential patterns suggest that professional development should be career-stage differentiated.

Administrative support emerged as a critical facilitating factor. Schools with strong administrative support implemented significantly more ESD programs (M = 3.2) than those without (M = 1.4; p < 0.001). This finding underscores the importance of institutional leadership—encompassing resource provision, risk tolerance, and collaborative culture—in enabling ESD implementation. Consequently, achieving sustainable ESD integration requires parallel investment in both administrator engagement and teacher professional development.

4.4. Contributions of Environmental Education Centers to ESD (RQ4)

KEPEA Zakynthos achieved comprehensive coverage, reaching all 121 primary schools through 305 programs involving 3970 students. This universal reach, in contrast to the fragmented implementation characteristic of school-initiated programs, demonstrates the value of centralized coordination in ensuring equitable ESD access. The findings support “hub-and-spoke” models wherein specialized centers provide expertise, resources, and coordination beyond the capacity of individual schools.

Program content reflected regional environmental priorities, with 32.5% focusing on marine conservation. The emphasis on local biodiversity—particularly the endangered loggerhead sea turtle—exemplifies effective place-based education linking global sustainability principles to local contexts. However, the limited integration of economic and social dimensions represents a missed opportunity for comprehensive sustainability education and may reinforce teachers’ environmentally-biased conceptualizations of ESD.

Participation patterns offer insights for program optimization. Average session attendance was 13 students, increasing to 23 for environmental trail programs—consistent with research linking experiential outdoor education to enhanced motivation and learning outcomes. These differential participation rates suggest that program design influences engagement, with implications for resource allocation and future programming priorities.

4.5. School-Community Collaboration Patterns (RQ5)

A pronounced intention-action gap characterized school-community collaboration. While 87.6% of teachers viewed partnerships as highly important, only 18.1% reported frequent engagement—a statistically significant disparity (χ2 = 142.67, p < 0.001). This gap indicates that institutional structures impede rather than facilitate collaboration, representing systemic barriers rather than attitudinal deficits.

Teachers predominantly favored event-based collaborations (69.5%) over sustained partnership models. This preference likely reflects pragmatic adaptation to existing constraints; event-based activities require less coordination, fewer resources, and minimal institutional change. However, such episodic engagement limits curriculum integration and access to ongoing community knowledge, resources, and opportunities for action that characterize deeper collaborative models.

Schools reporting sustained community partnerships demonstrated superior ESD outcomes, including greater teacher confidence, increased program diversity, and improved perceived student outcomes. These associations provide empirical support for ecological perspectives positioning schools within broader learning ecosystems rather than as autonomous institutions. The positive feedback loops generated by partnerships suggest that institutional reforms enhancing school-community permeability could yield multiplicative benefits for ESD implementation.

4.6. Place-Based Sustainability Education (ESD) Programs in Zakynthos (RQ6)

Aligning the program with Zakynthos’ distinctive characteristics demonstrates effective place-based ESD adaptation. Marine conservation programs leverage the island’s ecological significance as a sea turtle nesting site, while cultural heritage initiatives connecting sustainability to local history exemplify culturally responsive pedagogy. This regional adaptation extends beyond surface-level localization, reframing sustainability education through an authentic local lens.

Geographic participation patterns revealed context-driven program selection, with schools gravitating toward offerings most relevant to their immediate communities. These findings support flexible curricular frameworks that enable local adaptation while maintaining core sustainability competencies across diverse settings.

Cultural heritage programs integrated traditional knowledge and historical practices, addressing a commonly overlooked dimension of sustainability education. By examining sustainable resource management practices developed across generations, these programs challenge the misconception that sustainability is exclusively a contemporary concern. This historical perspective enriches student understanding while strengthening cultural identity and facilitating intergenerational knowledge transfer.

4.7. Regional Sustainable Development Through Primary Education (RQ7)

The contribution of primary education to regional sustainable development remains underexplored in the literature. This study examined both direct and indirect pathways through which primary education supports sustainability outcomes.

KEPEA’s annual reach of approximately 3970 students represents a substantial contribution to regional environmental literacy. Teachers reported strong educational impact, with 59.1% indicating extremely high positive effects on students’ environmental consciousness. However, an attitude-behavior gap emerged: only 39.0% reported extremely high impact on behavioral change, suggesting that awareness-building outpaces behavioral transformation.

Primary education also contributes to community capacity-building. Schools reported that ESD programs increased parent involvement, community visibility, and environmentally related community action, creating potential multiplier effects beyond direct student outcomes.

Temporal analysis revealed organizational resilience, with KEPEA maintaining consistent program delivery across 4 years of economic constraints and institutional challenges, indicating institutional commitment and regional acceptance of ESD. However, enrollment stabilization at approximately 350 students annually in school-based programs suggests capacity constraints, whether due to resource constraints or organizational capacity, rather than market saturation. This ceiling effect, combined with incomplete curriculum integration, indicates that primary education’s transformative potential for regional sustainable development remains partially unrealized.

4.8. Environmental–Economic Dimension Analysis

A striking finding from our triangulated data sources is the substantial imbalance between environmental and economic dimensions of sustainable development in teachers’ conceptualizations and practices. This pattern warrants careful analysis given the integrated three-pillar framework underpinning contemporary sustainability discourse.

4.8.1. Manifestation of the Imbalance

Teacher questionnaire data revealed that 67.3% of respondents associated sustainable development primarily with environmental protection and natural resource management, while only 18.1% emphasized economic sustainability. This conceptual pattern was mirrored in practice: KEPEA program documentation showed that 78.4% of programs addressed environmental themes, compared to 12.3% that incorporated economic dimensions. School-level records similarly indicated that environmental activities dominate implementation, with economic topics rarely appearing as standalone program foci.

4.8.2. Historical and Structural Factors

Several factors may explain this imbalance. First, environmental education in Greece preceded sustainability education, with established curricula, trained personnel, and institutional support structures (Environmental Education Centers) that predate the broader ESD framework. Second, economic concepts may be perceived as more abstract or age-inappropriate for primary students, leading teachers to gravitate toward tangible environmental topics. Third, teacher training programs have historically emphasized ecological literacy over economic understanding within sustainability contexts.

4.8.3. Implications for Student Learning

This dimensional imbalance has significant implications. Students may develop incomplete mental models of sustainability that emphasize conservation without understanding economic trade-offs, sustainable livelihoods, or the economic dimensions of environmental decisions. For Zakynthos specifically, where sustainable tourism represents a critical local issue, students may struggle to analyze the complex interplay between environmental protection (turtle nesting sites), economic development (tourism revenue), and social equity (local employment) that characterizes real-world sustainability challenges.

4.8.4. Recommendations

Addressing this imbalance requires targeted professional development, helping teachers integrate economic concepts into existing environmental programs. Place-based approaches offer particular promise: local examples such as sustainable fishing practices, eco-tourism certification, or organic olive oil production could connect environmental and economic dimensions through familiar contexts. Curriculum materials that explicitly address economic sustainability in age-appropriate ways would support teachers who lack confidence in this domain.

4.9. Theoretical Implications and Framework Development

The results of these studies provide a theoretical understanding of how the numerous individual, institutional, and systemic education elements affect a school’s capability to achieve the goals of sustainable development through the implementation of ESD. In addition, the large differences between awareness (intent) and behavior (attitudes) and then to action found in this study show that basic and straightforward models of implementation that assume awareness will result in attitudes toward actions (or vice versa) do not correctly represent the processes occurring in schools when they are implementing ESD.

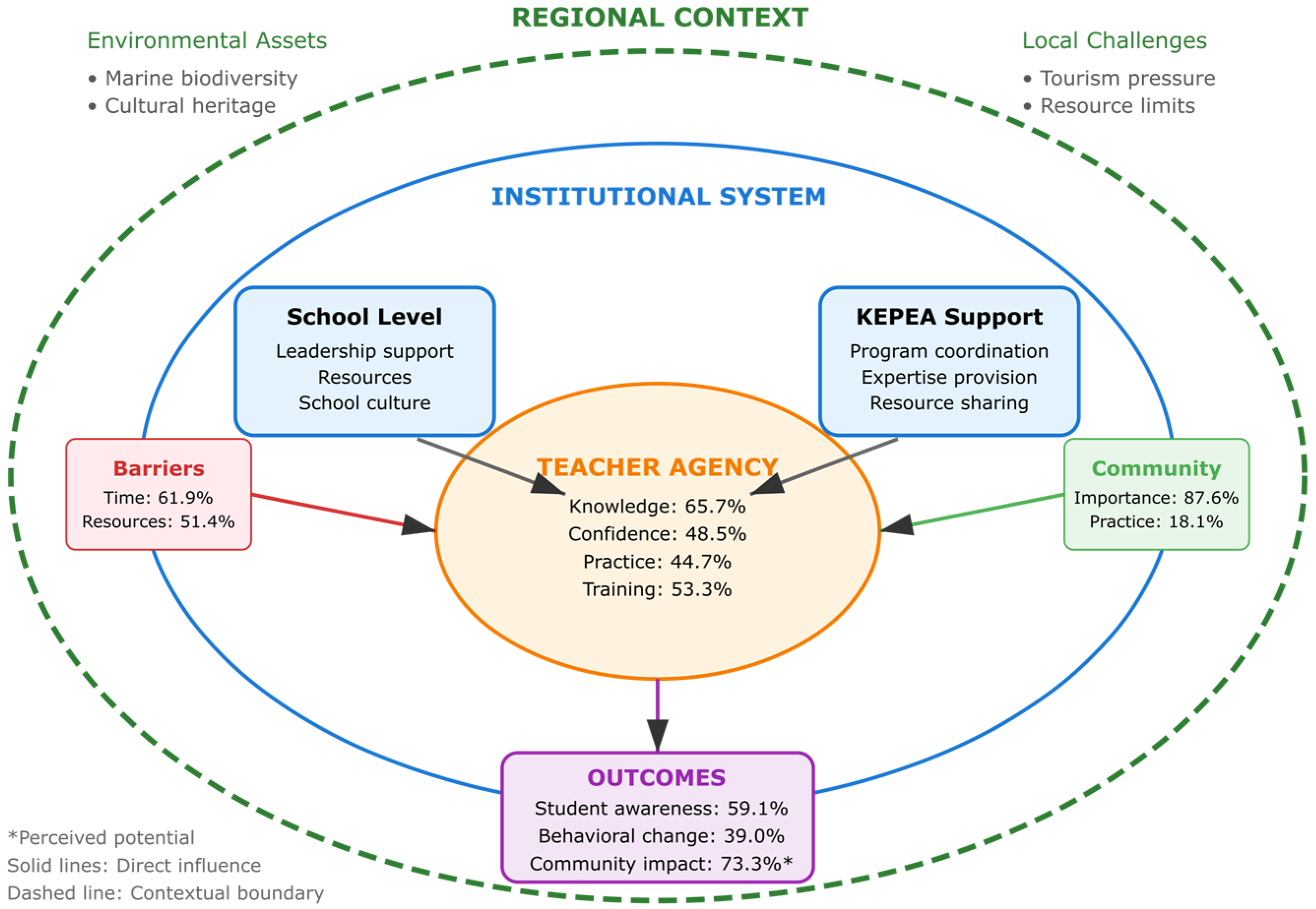

A conceptual model for an integrated framework (see

Figure 5) places teacher agency at the center and recognizes the nested systems that either support or hinder individual activity. The framework also shows that institutional structures and community partnerships are needed to complement teacher knowledge and motivation. Additionally, the wide gaps between the different dimensions—knowledge vs. confidence, importance vs. practice, aspirations vs. action—demonstrate the disconnects among systems that an individual can only attempt to address.

The integrated framework presented in

Figure 3 emerged through systematic synthesis of findings across our three data sources. Framework development proceeded through four iterative stages. First, we identified recurring themes from questionnaire responses and categorized them into knowledge, practice, and barrier domains. Second, we mapped these themes against patterns observed in KEPEA program documentation, noting where institutional programming aligned with or diverged from teacher perspectives. Third, we analyzed convergence and divergence patterns (detailed in

Section 3.5) to identify robust findings supported by multiple data sources versus areas of inconsistency requiring interpretation. Finally, we synthesized these patterns into a multi-level framework distinguishing individual factors (teacher knowledge, attitudes, skills), institutional factors (school support, KEPEA programming, curriculum integration), and contextual factors (community partnerships, regional sustainability context, policy environment). The framework’s bidirectional arrows reflect empirical evidence of reciprocal relationships: for example, community partnerships both influence and are influenced by teacher practices, as demonstrated by the correlation between partnership frequency and teaching integration (rs = 0.38,

p < 0.01). This empirically grounded framework provides a foundation for targeted intervention development addressing specific leverage points in the ESD implementation system.

Empirical data from the study provide leverage points for intervention in the framework. A strong positive correlation was observed between administrative support and program implementation, suggesting that professional development for school administrators may be a more effective means to improve program implementation than additional teacher training. The large collaboration gap indicates the need for structural reforms that enable partnerships to realize the potential of the school-community system. Thus, the framework serves dual functions: as a tool for analysis and as a guide for practitioners seeking to identify areas for intervention based on the existing conditions in their schools.

4.10. Practical Implications

The findings have several practical implications for both educational policy and practice. The results indicate that the incomplete representation of sustainable development in teachers’ views on the subject will require professional development broader than environmental topics alone. Professional development should be designed to provide an integrated view of sustainability across all three dimensions (economic, social, and cultural). This training should primarily be based on practical and school-based experiences, rather than a series of theoretical workshops, to increase pedagogical confidence. The results also suggest that there are career-stage differences in how barriers are perceived; therefore, differentiated professional development pathways should account for differing levels of need at various stages of a teacher’s career.

The results regarding the patterns of institutional support identified in the study indicate a need to pay attention to the roles of school leaders and to organizational culture. As such, there is a need to incorporate sustainability leadership competencies into principal preparation programs and to include recognition and rewards for implementing Education for Sustainable Development (ESD) in school evaluation frameworks. Additionally, there are systemic solutions that could be developed that include the creation of specific funding streams to support the development of sustainability education in schools, the creation of teaching resources that are tailored to the context of the local community, and the allocation of time within the curriculum framework to legitimize sustainability education as opposed to marginalizing it. Over half of the respondents reported experiencing resource constraints in their efforts to develop sustainability education in their classrooms and schools.

Although many respondents expressed a desire to participate in KEPEA programs, success in these programs suggests a strong case against further consolidation of Environmental Education Centers, even with continued emphasis on fiscal responsibility. The results of the study indicate that investment in strengthening and expanding KEPEA’s role, particularly its capacity to facilitate partnerships between schools and communities and to provide pedagogical support to teachers, would generate substantial returns.

Program participation showed geographic and thematic patterns, suggesting that flexible, menu-based program offerings relevant to the contexts in which schools operate would be beneficial. In other words, schools would benefit from the opportunity to choose from a variety of program options tailored to their unique circumstances, rather than relying solely on standardized programs implemented uniformly across all schools.

The greatest potential for improving collaboration lies in the collaboration gap. Closing this gap would require significant structural reform to reduce bureaucratic barriers to collaboration. By creating formal partnership structures that clarify the partnership development process, protect partners from liability, and provide adequate resource infrastructure, the latent demand for community involvement in individual teachers’ responses may be unleashed. Establishing community liaison positions can foster connectivity among stakeholders who are often disconnected due to heavy workloads.

4.11. Comparison with International Literature

The results from Zakynthos confirm and extend the patterns observed in international ESD research. The observed knowledge-action gap is consistent with studies across contexts, showing that awareness alone is insufficient to translate into practice without supportive conditions. However, the magnitude of specific gaps, especially the collaboration discrepancy, exceeds those reported in Northern European contexts, where institutional structures better support the linking of schools with their communities [

88,

89,

90,

91].

This dominance of environmental dimensions in teacher conceptualization reflects global patterns but is more pronounced than in contexts with stronger traditions of integrated sustainability education. This could reflect Greece’s strong environmental education heritage and the lack of systematic ESD integration in the country’s teacher preparation programs. The preference for interactive pedagogies aligns with international best practices; however, the limited use of experiential learning falls below the levels reported in countries with outdoor education traditions [

92,

93,

94,

95,

96,

97,

98,

99,

100].

The critical role of specialized support centers parallels hub models implemented across different countries, though KEPEA’s overall reach is greater than that of institutions operating with substantial resources. This efficiency may stem from the manageable scale of island contexts and the robustness of local networks, with the implication that island settings offer advantages for coordinated ESD implementation even in resource-constrained conditions [

101,

102,

103,

104,

105,

106,

107].

The demographic patterns, such as gender differences in environmental awareness and age-related variation in implementation, reflect findings from international studies as well, but are marked by culturally specific nuances. The higher female participation may be due to both international trends in women’s environmental concern and local cultural factors influencing professional choices and development opportunities. The age-related patterns suggest generational shifts in educational philosophy extending beyond national contexts [

108,

109,

110,

111,

112,

113,

114,

115,

116].

4.12. Limitations

Several limitations constrain the interpretation and generalization of these findings: The cross-sectional survey design provides a snapshot of teacher perceptions and practices at one point in time and allows no causal inferences concerning relationships among variables or estimates of change over time. Longitudinal research following teachers and schools over several years would yield stronger evidence on the development of ESD implementation and impacts.

The reliance on self-reported data for teaching practices introduces a degree of social desirability bias, leading teachers to overreport their actual integration of sustainable development. Although some validation comes from triangulation with program documentation, the gap between reported and observed practices may be greater than that identified. Classroom observations would provide a much more accurate assessment of pedagogical practices and student engagement, although methods for direct observation fell beyond the scope of this study.

While the focus on Zakynthos allows for an in-depth analysis of place-based ESD implementation, it limits generalizability to other contexts. Island settings offer unique characteristics, such as defined boundaries, limited resources, strong local identity, and specific environmental challenges not found in mainland or urban settings. Comparing research across diverse regional settings would answer questions about which findings indicate universal patterns, and which are context-specific.

Overlapping with post-pandemic educational recovery, the study period might have influenced findings in ways not fully captured by the research design. In fact, the high levels of participation for 2022–2023 could reflect pandemic-related elevations rather than sustainable trends, and teacher stress or systemic disruptions may lead to suppressed typical levels of implementation. Replication during more stable times would clarify the degree to which the pandemic influences these findings.

While comprehensive for formal initiatives, the underestimation of total ESD activity in program documentation may fail to capture informal integration within the regular curriculum. Teachers may implement sustainability concepts in daily teaching in ways not captured by these program counts. Moreover, the quality and depth of the implementation within documented programs are unmeasured, and the participation numbers do not reveal learning outcomes or transformative impacts.

This may be seen as a significant limitation, as in sustainability education, students are the primary beneficiaries and agents of change. Student perspectives on learning experiences, attitude formation, and behavioral change would provide critical confirmation of teachers’ perceptions and program effectiveness. Likewise, parent and community member perspectives would bring deeper insights into ESD’s impact beyond school boundaries.

4.13. Future Research Directions

The findings and limitations of this study point to several promising directions for future research that could further both the understanding and practice of ESD within primary education. Longitudinal studies following cohorts of students from early primary through their secondary education would provide critical evidence concerning the long-term impacts of early sustainability education on environmental consciousness, career choices, and adult behaviors. This could identify critical intervention periods and the optimal sequence of sustainability concepts across developmental stages [

117,

118,

119,

120,

121,

122,

123,

124,

125].

The transferability of the Zakynthos model and which factors in its implementation are universal and which are context-specific would be further clarified by comparative research across Greek regions with different environmental, economic, and cultural characteristics. International comparative studies could place Greek ESD efforts within larger European and global contexts and enable policy learning and practice exchange. Particular attention to island contexts around the Mediterranean would allow the identification of common challenges and successful strategies for resource-constrained settings [

126,

127,

128,

129,

130,

131,

132,

133,

134,

135].