Abstract

Wildfires represent one of the most destructive natural disturbances, yet they play a fundamental ecological role in the regeneration and evolution of forest ecosystems. In Mediterranean regions, fire acts as a selective factor shaping plant adaptive strategies and the structure of vegetation mosaics. This study analyzes post-fire regeneration dynamics in Pinus radiata and P. pinaster plantations located in Roccaforte del Greco (Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria, southern Italy), severely affected by the 2021 wildfires. Phytosociological surveys were conducted along permanent transects using the Braun-Blanquet method and analyzed through diversity indices (Shannon, Evenness), Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling (NMDS), Indicator Species Analysis (IndVal), and hierarchical clustering. The results reveal a clear floristic differentiation among management conditions, with higher species diversity and variability, and a predominance of pioneer therophytes and hemicryptophytes in burned areas. The in situ retention of burned logs enhances structural and microenvironmental heterogeneity, facilitating the establishment of native species and supporting post-fire functional recovery. Overall, this preliminary study, focusing on early successional dynamics, suggests that the in situ retention of burned logs may positively contribute to ecosystem resilience and biodiversity in post-fire Mediterranean pine forests, while also highlighting the need for long-term monitoring to confirm the persistence of these effects.

1. Introduction

Fire is one of the most destructive natural phenomena and a characteristic element of boreal, temperate, and tropical regions worldwide. At the same time, it represents a key factor shaping the equilibrium of many forest ecosystems and the ecological history of numerous landscapes [1].

Fire has played a fundamental role in the evolutionary history of plants since the Silurian (ca. 443 million years ago), and not only in more recent geological periods [2].

Although commonly perceived as catastrophic events, wildfires constitute, an intrinsic ecological factor of many ecosystems, combining destructive processes with mechanisms of renewal and regeneration [3].

In Mediterranean-climate regions, the influence of fire on vegetation has progressively increased due to the addition of anthropogenic ignitions to natural fire regimes, producing heterogeneous effects depending on local environmental conditions and ecological context [4,5]. Wildfires act as selective agents, promoting the survival and regeneration of plant species adapted to recurrent disturbance [6]. Fire often removes the pre-existing vegetation cover, triggering secondary succession dynamics that may restore plant communities similar to the original ones within one or two decades [6]. In Mediterranean environments, vegetation recovery frequently follows autosuccessional pathways driven by resprouting and vegetative regeneration of the same species present before the fire, resulting in limited changes in floristic composition and a rapid re-establishment of pre-fire physiognomy [7]; at the same time, vegetation responses may diverge depending on landscape heterogeneity and fire-regime characteristics, giving rise to distinct successional trajectories [8]. However, recent large-scale assessments have shown that the increasing interaction between climate and land-use change and altered fire regimes is progressively eroding the resilience of Mediterranean forest ecosystems, pushing some systems toward critical thresholds of degradation and collapse, as highlighted for Chilean Mediterranean forests by Cueto et al. [9]. In the Mediterranean basin, too, the increasing frequency of forest fires, largely due to improper land management and human activities, exacerbated by drought linked to climate change, can lead to serious ecological consequences, including reduced ecosystem productivity and the onset of desertification processes [10,11,12,13,14].

At the same time, agricultural abandonment in marginal and hilly areas has promoted the expansion of monospecific plantations of highly flammable species, such as Pinus sp. pl. and Eucalyptus sp. pl., increasing the vulnerability of forest landscapes to wildfire [15,16]. Forest ecosystems characterized by high plant diversity generally exhibit greater resilience due to the coexistence of species with different disturbance-response strategies; conversely, structurally simplified monocultures, lacking functional heterogeneity, are particularly fragile and prone to irreversible collapse following fire [17].

The increase in the frequency of fires, which are increasingly widespread and destructive, has serious consequences, both direct and indirect, including economic ones, and poses a substantial threat to human safety, sometimes resulting in loss of life [13,18,19]. Beyond the immediate impacts on vegetation and infrastructure, severe or recurrent fires exert long-lasting effects on ecosystems, particularly on soils and hydrological processes. Fire alters soil structure and fertility through organic matter combustion and litter loss, while simultaneously modifying water regulation by increasing surface runoff and reducing soil water retention, thereby enhancing the risk of floods and hydrogeomorphological instability during post-fire rainfall events [20,21,22,23].

Vegetation plays a crucial role in soil protection through canopy interception, which reduces raindrop impact, and through root systems that stabilize soil particles [11,24]. Consequently, the loss of vegetation following fire promotes soil particle detachment and transport, particularly during high-intensity post-fire precipitation events [24].

The effects of fire extend beyond vegetation to include fauna and overall biodiversity. Many animal species depend on the structural and compositional features of forest vegetation and on the availability of different successional stages [25]. Some taxa may temporarily benefit from post-fire conditions: certain bird species exploit the increased abundance of insects and other organisms associated with burnt substrates [25], while some mammals and reptiles are able to rapidly adapt to the altered spatial configuration [26,27]. In addition, the increased availability of dead wood generated by fire can provide essential habitat and resources for saproxylic organisms, including insects and fungi, thereby supporting post-fire biodiversity and food-web dynamics [28,29].

However, the loss or severe reduction in habitat types linked to specific plant communities can have detrimental effects, particularly on vulnerable or endemic species, highlighting the need for targeted post-fire management aimed at promoting vegetation recovery and mitigating impacts on wildlife [13,30,31,32].

Mediterranean ecosystems generally exhibit high resilience to wildfire due to the presence of numerous plant species that have evolved fire-adaptive traits enabling survival and regeneration after burning, including autosuccessional mechanisms [3,33,34], through three main regenerative strategies, commonly referred to as plant functional types (PFTs).

- -

- “Resprouting species” survive fire thanks to protected buds located in different parts of the plant, such as basal or underground buds associated with specialised storage structures, such as lignotuber, or dormant buds along branches protected by thick bark, as observed in many Mediterranean woody species [35,36]. This strategy allows for rapid vegetative recovery, as observed in Quercus ilex, Q. suber and several Mediterranean shrubs [37,38]. Geophytes survive fire thanks to deep rhizomes or bulbs located below lethal temperature thresholds [35].

- -

- “Seeder species”, by contrast, do not survive fire as adults and rely on soil or canopy seed banks for post-fire regeneration, taking advantage of nutrient-rich ash beds and increased light availability [39,40,41]. Obligatory seeders form persistent seed banks with dormancy broken by heat or smoke-derived cues, a strategy typical of several Fabaceae and Cistaceae species [14,35,42]. Some conifers exhibit serotiny, retaining seeds in closed cones that open synchronously in response to fire, as observed in Pinus halepensis and P. pinaster [35,42,43]. Annual therophytes often dominate early post-fire stages due to rapid growth and high seed production [44,45,46]. However, seeder species are particularly vulnerable to short fire-return intervals that prevent individuals from reaching reproductive maturity, potentially leading to population decline [39].

- -

- “Intermediate strategies” combine both resprouting and seeding mechanisms. Typical examples include tufted grasses of Mediterranean grasslands, such as Ampelodesmos mauritanicus and Hyparrhenia hirta, which protect buds at the base of the tussock and regenerate rapidly after fire while also reproducing through soil-stored seeds [47].

Post-fire recovery dynamics in Mediterranean vegetation are influenced by multiple ecological, climatic, and geological factors, among which soil erosion plays a critical role. The loss of topsoil, particularly pronounced in hilly and mountainous landscapes, can amplify habitat degradation and significantly limit vegetation recovery potential [48,49].

Within this context, the present study focuses on post-fire vegetation recolonization dynamics in relation to erosion-mitigation interventions, with the aim of evaluating the effectiveness of such practices in enhancing soil stabilization and supporting sustainable ecological recovery.

In Italy, Mediterranean pine forests dominated by Pinus pinea, P. pinaster, and P. halepensis cover approximately 226,101 ha, accounting for about 4% of the total forest area, according to the National Forest Inventory [50]. These stands largely consist of plantations established in recent decades with the primary objective of reducing soil erosion and stabilizing slopes. Nevertheless, they currently face significant conservation challenges, as high stand densities often limit natural regeneration and reduce structural and compositional diversity, compromising their long-term persistence [51]. Artificial plantations, particularly those created with non-native species, should undergo renaturalisation processes [51] aimed at restoring potential natural vegetation, thereby improving ecosystem functionality and allowing the formation of more complex, stable and resilient forest communities [51].

In this framework, the present study addresses a relevant knowledge gap by providing empirical, field-based evidence on the role of in situ retention of burned logs as a nature-based solution for post-fire management in Mediterranean pine plantations. Accordingly, the purpose of this study is to evaluate post-fire regeneration dynamics in Mediterranean pine plantations. The case study focuses on pine stands within the Aspromonte National Park (southern Italy), severely affected by a wildfire in 2021 and subsequently subjected to management interventions, with particular emphasis on the effectiveness of retaining burned logs in situ as a nature-based solution to promote renaturalization, soil stability, and ecosystem resilience.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

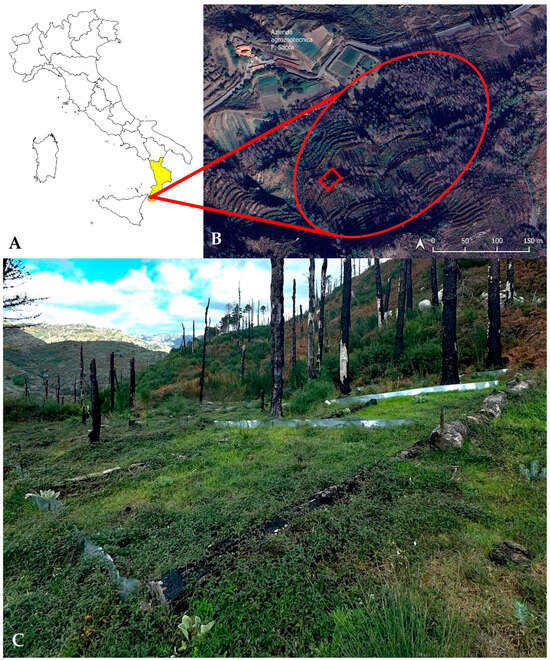

The study area is located entirely within the municipality of Roccaforte del Greco (Metropolitan City of Reggio Calabria, Southern Italy). It is characterized by extensive Pinus plantations, dominated by Pinus radiata D.Don and Pinus pinaster Aiton subsp. pinaster, most of which were severely affected by the wildfire that struck the area in 2021 [22,23,52,53,54]. The site lies at elevations ranging between 970 and 1020 m a.s.l. (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study area located in Aspromonte National Park (southern Italy). (A) Geographic location of the study area in Italy and within the Calabria region. (B) Satellite view showing the extent of the study area (outlined in red) and the position of the experimental plot (red square). The distribution map was created using ®QGIS 3.26.3 [55], with spatial data overlaid on ©Google Satellite imagery [56], available through the QGIS XYZ Tiles service. (C) Field view of the post-fire pine plantation, showing retained burned logs arranged along contour lines and early post-fire vegetation recovery within the experimental area.

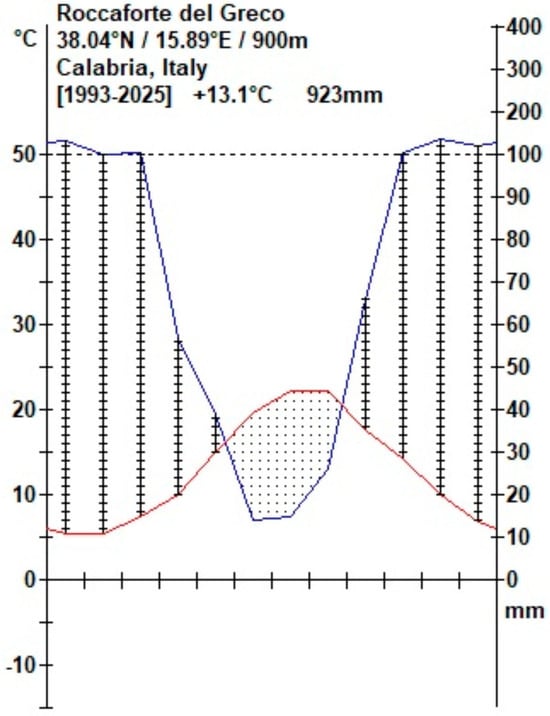

For the climatic characterization of the study area, meteorological data were obtained from the ARPACAL portal [57], with specific reference to the Roccaforte del Greco station, code 2340, the nearest station to our site. The mean annual temperature is approximately 13.1 °C. The dry season lasts for about three months, from the end of May to the end of August.

Precipitation shows marked seasonal variability, consistent with the typical rainfall regime of Mediterranean areas. The mean annual total is approximately 923 mm. The wet period extends for about nine months, from early September to mid-May (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Climate diagram of study area (Roccaforte del Greco—RC), according to Walter and Lieth [58], generated using Climate Plot 32 (©1999 Backhuys Publishers, Leiden, The Netherlands). The diagram shows the mean monthly value of temperature (red line) and precipitation (blue line), highlighting the dry season (dotted area, defined as monthly value of P < 2T) and the wet period (vertical line area).

The investigated area is characterized by a Mediterranean macrobioclimate, with a pluviseasonal oceanic bioclimate, upper mesomediterranean thermotype, and upper subhumid ombrotype [59].

2.2. Data Collection

The study was conducted within a single experimental plot located in the burned pine plantation of the study area. Following the August 2021 wildfire, post-fire management actions were implemented during the subsequent months, and the experimental plot was established in October 2021. The plot corresponds to the same experimental parcel previously investigated and described by Bombino et al. [22,23] and is located on a north-eastern-facing slope. The management treatment consisted of the in situ retention of eight burned logs already present within the burned area. These logs were not removed but manually repositioned and arranged transversely to the slope and to the main runoff directions in order to increase surface microtopographic complexity, reduce runoff velocity, and enhance soil stabilization and microenvironmental heterogeneity. Burned trunks generally ranged between approximately 1.5 and 4.0 m in length.

To characterize the flora and vegetation and to evaluate their temporal dynamics, phytosociological surveys were conducted using the permanent transect method. This approach allows for the analysis of the spatial distribution of plant species, vegetation structure, and changes in cover over time, providing essential information for the management and conservation of ecosystems affected by wildfire [60]. Within the experimental plot, three permanent transects were established, each 10 m long and positioned along the longitudinal profile of the study area: one in the central portion and two along the lateral margins [60]. Along each transect, 1 × 1 m sampling plots were established following the alternating-plot technique [61], which consists of placing non-contiguous sampling units to increase representativeness and reduce bias associated with environmental variability. This approach is particularly suitable in structurally complex environments, as it allows sampling across a broad range of ecological conditions and heterogeneous vegetation communities. For each transect, the following baseline information was recorded: unique identifier (ID), elevation (m a.s.l.), slope (°), aspect, and geographic coordinates (decimal degrees).

Vegetation surveys were conducted during key periods of the year corresponding to major phenological phases, in order to capture seasonal variations in cover and floristic composition. Sampling activities were therefore planned when vegetation was most expressive and representative, enabling the detection of both perennial species and ephemeral annuals. This timing ensured accurate species census and minimized the risk of underestimating plant diversity due to phenological differences or temporary disappearance of taxa. For each plot, the following data were collected: transect ID and plot number; survey date; average height and percentage cover of vegetation layers (herbaceous, shrub, and tree layers); percentage cover of litter; deadwood; bryophytes; and bare ground. All species occurring within each 1 m2 plot were recorded, and their percentage cover was estimated by subdividing the plot into 10 × 10 cm grids to improve estimation accuracy.

Additional phytosociological surveys were also performed using the Braun-Blanquet method [62] in areas adjacent to the transects, following a random sampling design within environmentally homogeneous units selected based on physiognomic and structural uniformity. Representative surfaces were selected for each vegetation unit under the most homogeneous conditions. In each relevé, all vascular plant taxa were recorded with abundance–cover estimates following the Braun-Blanquet scale [62] (classes +, 1–5). Cover estimates were also assigned for each vegetation layer (tree, shrub, herb layers), as well as for litter, bare soil, and rock cover. Environmental variables (elevation, slope, aspect, topography, disturbance type) were simultaneously recorded. All relevés were georeferenced and conducted during the phenological period of maximum floristic detectability.

Finally, an in-depth analysis of pressures and threats influencing habitat conservation and natural regeneration capacity was carried out for the entire study area. This analysis involved the identification, description, and coding of each disturbance factor following the criteria established in the Reference List of Threats, Pressures and Activities proposed by Salafsky et al. [63] and later updated by the European Environment Information and Observation Network [64]. This standardized framework allowed for consistent classification of different impact types, including both natural disturbances, such as extreme climatic events and intrinsic ecological processes (e.g., landslides), and anthropogenic factors, such as wildfires, agricultural activities, grazing, or the presence of invasive alien species.

2.3. Data Analysis

The doubtful taxa observed in the field were collected and deposited in the Herbarium of the Mediterranean University of Reggio Calabria (REGGIO) [65] and identified using Flora d’Italia [66,67,68,69,70]. For alien species, online floras and specialized databases such as GBIF [71], CABI [72], and POWO [73] were consulted. Taxonomic nomenclature follows the Portal to the Flora of Italy [74] and the second checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy [75].

All field relevés were tabulated in an Excel spreadsheet [76]. When necessary, Braun–Blanquet cover–abundance classes were converted into ordinal values according to the van der Maarel scale [77] for subsequent statistical analyses.

A comprehensive checklist of the flora occurring in the study area was compiled and tabulated in Excel [76]. The floristic list was analyzed in terms of chorology and biological forms. Biological forms were classified according to Raunkiaer’s system [78]. Chorotypes follow Pignatti [66]. For each taxon, the origin status was also reported according to PFI [74], distinguishing two main categories: Alien (A): species introduced by humans, intentionally or unintentionally, outside their native range; Native (N): species naturally occurring in a given area, whose presence is not related to human activity and reflects the evolutionary history of the territory.

Biodiversity in the study area was assessed using the Shannon–Weaver [79] diversity index (1), which accounts both for the number of species present (richness) within a given habitat and for the distribution of their relative abundances (evenness) defined as:

where S is the total number of species and pi (2) is the relative importance of the i-th species (e.g., frequency or percentage cover), calculated as:

where ni is the number of individuals (or cover, or frequency) of species i, and N is the total number of individuals (or total cover) of all species.

Evenness (J) (3), defined as the ratio between the observed diversity (H) and the maximum possible diversity (Hmax), was also calculated as:

The value of J ranges from 0 to 1. When J = 1, all species are equally represented and the observed diversity corresponds to its maximum possible value (Hmax). Conversely, low values of J indicate dominance by one or a few species, with the remaining species being poorly represented. This index is particularly useful for monitoring temporal changes in biodiversity [79].

To analyze the floristic composition of the sampled plots, a non-parametric ordination analysis (NMDS, Non-metric Multidimensional Scaling) was performed using the software PAST 4.10 [80], employing the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity coefficient, which is appropriate for ecological data expressed as percentage cover. The analysis was based on a species × plot matrix, where each sampling unit corresponded to a 1 m2 quadrat placed along the three permanent transects (left margin, centre, and right margin).

To identify the species most strongly associated with the different sectors of the experimental plot, an Indicator Species Analysis (IndVal) was performed following the approach of Dufrêne and Legendre [81], using PAST 4.10 [80]. This method allows the identification of indicator species, i.e., species exhibiting a non-random spatial distribution and a strong association with specific groups of relevés, both in terms of abundance and frequency of occurrence.

The Indicator Value (IndVal) (4) for each species was calculated by combining two components: specificity (A), which measures how exclusive a species is to a particular group, and fidelity (B), which measures the constancy of the species within that group. The final index ranges from 0 to 100 and is computed as:

where is specificity, i.e., the proportion of the abundance of species i found in group j relative to its total abundance across all groups, and is fidelity, i.e., the frequency of occurrence of species i within group j.

For each species, the IndVal value was calculated for every group, and the group with the highest value was identified as the reference group for that species. To test whether the association between species and groups was statistically significant, a permutation test (999 permutations) was performed. The p-value was computed as the proportion of permutations in which the randomized IndVal was equal to or greater than the observed value. A species was considered a significant indicator when p ≤ 0.05 and its IndVal value was high. Intermediate IndVal values allowed the identification of different levels of association: low values (0–30): the species is scarce or broadly distributed across groups, without indicating specific conditions; medium values (30–60): the species shows some preference for a group, but is neither exclusive nor constant; high values (60–100): the species is strongly indicative and useful for identifying and monitoring particular habitats or vegetation communities.

To analyze floristic similarity among relevés, a hierarchical clustering analysis was performed using PAST 4.1 [80]. The data matrix, containing Braun–Blanquet [62] cover values converted to the van der Maarel [77] scale, was analyzed using the UPGMA agglomerative method (Unweighted Pair Group Method with Arithmetic Mean) and Chord distance.

In addition, each species was assigned to its corresponding vegetation class according to Mucina et al. [82], considering its sociological role within the study area [83]. To assess differences in floristic composition between the two experimental areas (plots with logs retained in situ and unmanaged areas), the Bray–Curtis dissimilarity index [84] (5) was calculated using the abundance matrix by phytosociological class.

It should be noted that Bray–Curtis dissimilarity was intentionally computed using phytosociological classes rather than individual species abundances, in order to capture differences in vegetation structure and syntaxonomic composition between management conditions. Species-level patterns were instead explored through NMDS ordination and Indicator Species Analysis, allowing the integration of both compositional and structural perspectives in the interpretation of post-fire vegetation dynamics. This index, widely used in vegetation ecology, quantifies the degree of difference between two communities based on relative abundances or counts of taxa, ranging from 0 (identical communities) to 1 (completely different communities).

The index was calculated using the standard formula:

where ai and bi represent the number of taxa belonging to the i phytosociological class in the two areas being compared.

The calculation was carried out using PAST v. 4.1 [80], selecting the abundance matrix by phytosociological class as input. The resulting value provides a synthetic measure of overall floristic dissimilarity, useful for highlighting the effect of retaining burned logs in situ on the composition and structure of the plant communities.

Each multivariate analysis was applied with a specific and complementary purpose. NMDS was used to explore overall floristic patterns and spatio-temporal variability among plots; Indicator Species Analysis (IndVal) was applied to identify taxa preferentially associated with different sectors of the experimental plot; cluster analysis was used to assess floristic affinities among phytosociological relevés. Bray–Curtis dissimilarity was calculated at the phytosociological class level to provide a synthetic measure of structural and syntaxonomic differentiation between treated and unmanaged areas, rather than species-level compositional turnover.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of Flora

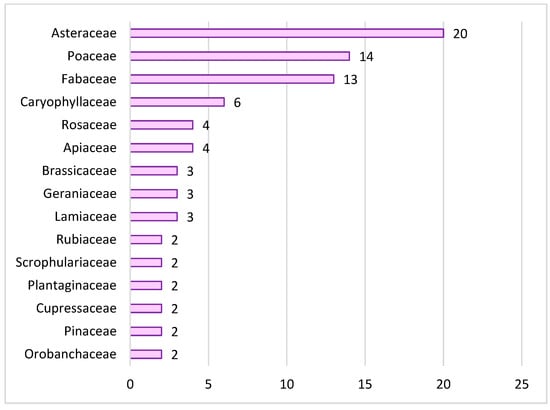

The flora of the study area comprises 97 vascular taxa belonging to 29 families and 74 genera. The most represented families are Asteraceae (20 species; 20.6%), followed by Poaceae (14 species; 14.4%) and Fabaceae (13 species; 13.4%), which together account for nearly half of the total floristic richness (48%). Caryophyllaceae (6 species), Rosaceae and Apiaceae (4 species each) follow with lower values, whereas the remaining families are represented by one to three species (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Distribution of vascular plant species among the most represented botanical families.

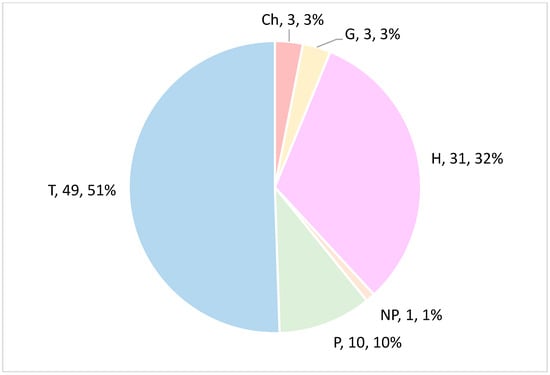

The biological spectrum reveals a marked predominance of therophytes (T, 49 species; 51%), followed by hemicryptophytes (H, 31; 32%), and, to a lesser extent, chamaephytes (Ch, 3; 3%), geophytes (G, 3; 3%), phanerophytes (P, 10; 10%), and nanophanerophytes (NP, 1; 1%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Biological spectrum of the recorded flora. T = therophytes; H = hemicryptophytes; Ch = chamaephytes; G = geophytes; P = phanerophytes; NP = nanophanerophytes.

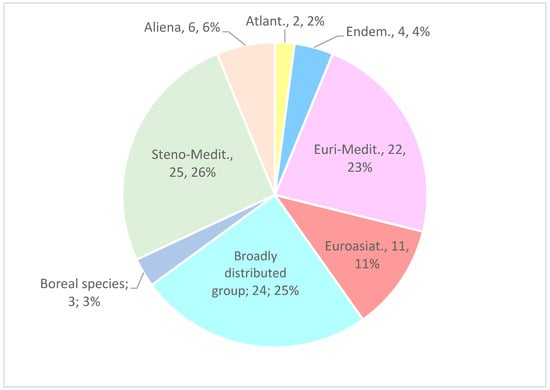

The chorological spectrum shows a clear predominance of Steno-Mediterranean elements (25; 26%), followed by Euri-Mediterranean taxa (22; 23%), which together account for 49% of the Mediterranean component. These are followed by broadly distributed taxa (24; 25%) and Eurasian elements (11; 11%). Endemic species (4; 4%), Atlantic and boreal species (2–3%) are marginal. Particularly noteworthy is the presence of alien taxa, which represent 6% of the total flora (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Chorological spectrum of the recorded flora.

The Shannon index (H = 2.03) indicates an intermediate level of species diversity, suggesting the presence of a substantial number of taxa with differentiated abundances. The maximum theoretical diversity (Hmax = 3.81) shows that, under conditions of perfect evenness, the community could achieve a considerably higher level of complexity. However, the evenness value (J = 0.53) reveals that species abundances are not uniformly distributed: a few species tend to dominate and exert a stronger influence on community structure, whereas others occur at lower frequencies, resulting in only partial ecological balance.

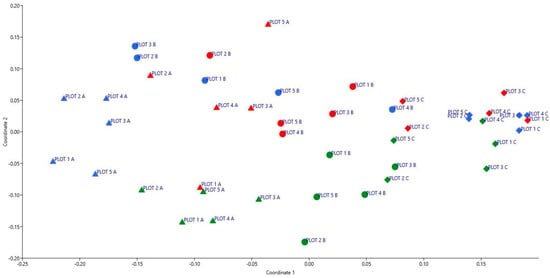

The NMDS analysis revealed a clear spatial separation among plots according to their position within the experimental parcel and the sampling period. In the ordination diagram (Figure 6), colours represent the different survey dates (blue: November; red: April; green: May), while shapes indicate transect position: triangle for the left margin (A), circle for the centre (B), and diamond for the right margin (C). The arrangement of points shows that central plots tend to cluster within a restricted ordination space, suggesting a relatively homogeneous and temporally stable floristic composition. This pattern indicates that the centre of the parcel is characterised by more uniform ecological conditions, with reduced influence from edge-related disturbances and a more consolidated plant community.

Figure 6.

NMDS (Non-Metric Multidimensional Scaling) analysis of the floristic composition within the permanent transects of the Roccaforte del Greco study area. Colours indicate the different sampling periods (blue: November; red: April; green: May), while shapes represent transect position (triangle: left margin—A; circle: centre—B; diamond: right margin—C).

In contrast, plots located along the margins display a more scattered distribution, reflecting higher floristic variability both between the two edges and across the different sampling dates. Such variability likely corresponds to greater environmental heterogeneity, driven by factors such as edge exposure, colonisation by pioneer species, and fluctuations in microclimatic conditions. Moreover, the partial overlap of points belonging to different sampling periods at the margins suggests that the vegetation composition in these areas is still undergoing dynamic changes, with processes of species turnover and the arrival of new taxa over time (Figure 6).

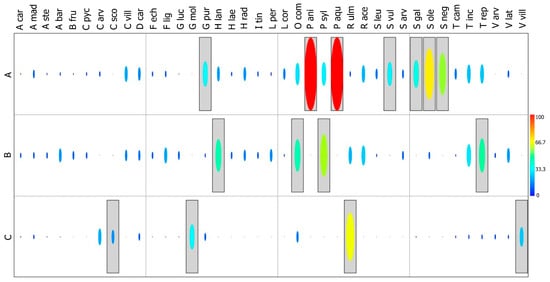

The Indicator Species Analysis (IndVal) (Figure 7) revealed clear patterns in species distribution along the spatial gradient of the experimental plot at Roccaforte del Greco, distinctly separating the three sampled sectors (A = left margin, B = centre, C = right margin).

Figure 7.

Analysis of species distribution using Indicator Species Analysis (IndVal) in the experimental plot of Roccaforte del Greco. The subdivision of the plant community along the spatial gradient is shown for the three sampled sectors (A = left margin, B = centre, C = right margin). Colours represent IndVal values ranging from 0 (blue) to 100 (red). Grey rectangles highlight species that are statistically significant with p ≤ 0.05. A code was assigned to each species: Aira caryophyllea—A car; Anisantha madritensis—A mad; Anisantha sterilis—A ste; Avena barbata—A bar; Brassica fruticulosa—B fru; Carduus pycnocephalus—C pyc; Cerastium arvense—C arv; Cytisus scoparius—C sco; Cytisus villosus—C vil; Daucus carota—D car; Falona echinata—F ech; Festuca ligustica—F lig; Galium lucidum—G luc; Geranium molle—G mol; Geranium purpureum—G pur; Holcus lanatus—H lan; Hypochaeris laevigata—H lae; Hypochaeris radicata—H rad; Isatis tinctoria—I tin; Lolium perenne—L per; Lotus corniculatus—L cor; Ornithopus compressus—O com; Pimpinella anisum—P ani; Poa sylvicola—P syl; Pteridium aquilinum—P aqu; Rubus ulmifolius—R ulm; Rumex acetosa—R ace; Senecio leucanthemus—S leu; Senecio vulgaris—S vul; Sherardia arvensis—S arv; Silene gallica—S gal; Sonchus oleraceus—S ole; Stellaria neglecta—S neg; Trifolium campestre—T cam; Trifolium incarnatum—T inc; Trifolium repens—T rep; Veronica arvensis—V arv; Vicia lathyroides—V lat; Vicia villosa—V vil.

At the left margin (A), very high IndVal values were recorded for several herbaceous species, particularly Pimpinella anisoides and Pteridium aquilinum, which are strongly associated with this sector (IndVal > 95; p ≤ 0.001). These species typify disturbed areas with partially colonised bare soil, indicating an early phase of post-fire recolonisation. Annual species such as Sonchus oleraceus and Stellaria neglecta are also present, reflecting open, dynamic, and disturbance-prone conditions.

The central portion of the plot (B) exhibits a floristically heterogeneous pattern, with IndVal values distributed without pronounced peaks. This sector is dominated by annual and perennial herbaceous species adapted to unstable environments and frequent disturbance. Among these, Poa sylvicola and Holcus lanatus, fast-growing and competitive grasses, enhance soil cover during early colonisation stages. Some Fabaceae, such as Ornithopus compressus and Trifolium repens, contribute to improving soil fertility through atmospheric nitrogen fixation, thereby facilitating the establishment of other plants. Their abundance suggests that the central sector represents an intermediate successional phase, dominated by pioneer communities that play a key role in post-fire recovery (Figure 7).

Finally, the right margin (C) is characterised by species associated with more advanced successional stages, including Rubus ulmifolius and Cytisus scoparius, which show high and significant IndVal values (IndVal > 95; p ≤ 0.001). Their presence indicates a process of vegetation consolidation, with increasing soil cover and a gradual decline in pioneer species (Figure 7).

Overall, the analysis identified key ecological indicators that reflect the vegetation status along the spatial gradient of the plot. Species with the highest IndVal not only discriminate among the sectors but also provide insights into post-fire recolonisation dynamics and the degree of habitat stability or vulnerability.

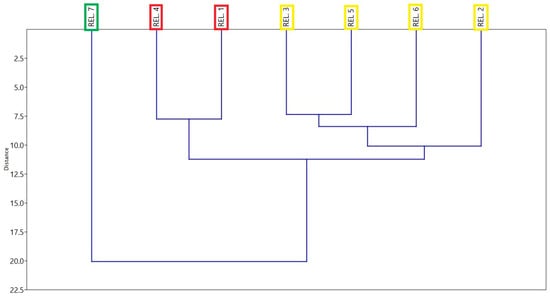

The cluster analysis (Figure 8) of the phytosociological relevés conducted in the areas adjacent to the permanent plot reveals three distinct groups. Relevé 7 separates early from all others, with a distance greater than 20, indicating a clearly distinct floristic composition strictly linked to the local edaphic and microclimatic conditions. Indeed, it is characterised by species typical of warmer and drier south-facing slopes, such as Spartium junceum, Rosa canina and Rubus ulmifolius.

Figure 8.

Dendrogram of floristic similarity for the phytosociological relevés conducted in the experimental area of Roccaforte del Greco. The analysis is based on the UPGMA agglomerative method and Chord distance. The different box colors (green, red and yellow) represent distinct clustering groups, and REL is the abbreviation of relevé.

Relevé 4 and Relevé 1 exhibit strong floristic affinity, clustering together at a very short distance (~7). These two relevés share similar ecological dynamics and are characterised by species typical of cooler, north-facing sites, such as Cytisus villosus and Cytisus scoparius.

The group formed by Relevé 2, Relevé 3, Relevé 5, and Relevé 6 occupies an intermediate position. These relevés show a relatively homogeneous floristic–ecological composition, although with some internal variability. This pattern likely reflects the presence of interconnected habitats where plant communities partially overlap while maintaining distinctive features related to soil properties and slope exposure. These relevés are mainly characterised by Pteridium aquilinum, with a lower representation of Cytisus villosus and Cytisus scoparius.

The analysis of pressures and threats (Table 1) made it possible to identify the main anthropogenic and natural factors affecting the conservation status of habitats and species within the study area. Agro-pastoral practices represent one of the principal sources of disturbance: both extensive grazing (A10) and agricultural burning (A11), as well as arson fires (H4), show high levels of pressure and threat, whereas land conversion to agricultural use (A01) currently exhibits a low impact. Infrastructure-related modifications—including roads, connection works and urban development (E01, F02)—generally display low pressure values, although in the case of road infrastructure the associated threat reaches a medium level. Waste management activities (F09) show low threat values.

Table 1.

Classification of pressures and threats affecting the study area according to Salafsky et al. [63] and later updated by EIONET [64]. COD refers to the threat code according to Salafsky’s classification system, while H and L indicate the level of impact, corresponding to High and Low, respectively.

Among biotic factors, the presence of invasive alien species represents one of the most critical issues: in particular, alien taxa not included in the EU list (I02) exhibit high levels of pressure and threat, with potential consequences for community structure and local ecological dynamics. The most widespread alien species in the study area include Cryptomeria japonica, Cupressus sempervirens, Erigeron bonariensis, Isatis tinctoria subsp. tinctoria, and the two pine species that formed the burned plantation and are currently regenerating: Pinus pinaster subsp. pinaster and Pinus radiata.

Natural abiotic processes (L01)—such as erosion, sedimentation and drought—show medium intensity, reflecting the geomorphological fragility of the area. Landslide processes (M05) appear relatively less significant, with low to medium impacts.

Finally, climatic factors constitute emerging threats: both rising temperatures (N01) and decreasing precipitation (N02) show medium to high impacts, confirming the increasing influence of climate change on ecosystem stability and vegetation dynamics.

3.2. Analysis of Phytosociological Classes

The analysis of phytosociological classes reveals marked differences between the vegetation of the experimental plot and that of the untreated surrounding area. Overall, 17 phytosociological classes were identified within the study area (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phytosociological classes recorded in the overall relevés and in the experimental plot, according to the syntaxonomic classification proposed by Mucina et al. [82]. Values indicate the percentage (%) of taxa assigned to each class.

The analysis of the syntaxonomic composition of the overall relevés (Table 2) reveals a clear predominance of the classes Chenopodietea and Quercetea pubescentis, each representing 18% of the taxa. The class Chenopodietea comprises ephemeral therophytes, nitrophilous or sub-nitrophilous species typical of ruderal and highly disturbed environments, occurring on nutrient-rich soils and in post-fire recolonisation contexts characterised by discontinuous vegetation cover and low competitive pressure. Conversely, Quercetea pubescentis includes species characteristic of deciduous oak forest communities, as well as thermophilous and meso-xerophilous elements typical of Mediterranean hill woodlands. These are followed by Artemisietea vulgaris (13%) and Cytisetea scopario-striati (9%), which comprise species of open, sunny and transitional environments featuring dynamic mosaics of herbaceous and shrubby elements. The class Helianthematea guttati (7%) represents pioneer communities typical of incoherent, dry and nutrient-poor substrates, dominated by ephemeral annual, xerophilous and thermophilous species with short winter–spring life cycles. Sisymbrietea (7%) includes highly ruderal and synanthropic pioneer communities, characterised by nitrophilous species adapted to nutrient-poor soils and strong disturbance, also with rapid biological cycles. The remaining classes are less represented (1–4%), including Rhamno-Prunetea, Trifolio-Geranietea sanguinei, Poetea bulbosae, Papaveretea rhoeadis, Molinio-Arrhenatheretea, Carpino-Fagetea sylvaticae, Lygeo-Stipetea, Thlaspietea rotundifolii and Quercetea ilicis, which nonetheless contribute to delineating a complex vegetational mosaic combining grassland, shrubland and forest elements.

In the experimental plot (Table 2), the distribution of vegetation classes shows a clear shift towards greater floristic and structural diversity. Chenopodietea remains the dominant class (26%), but there is a marked increase in components belonging to Helianthematea guttati (18%)—pioneer communities dominated by ephemeral, xerophytic, thermophilous, non-nitrophilous annuals with short winter–spring cycles and to Sisymbrietea (12%), characterised by ruderal and synanthropic species that colonise highly disturbed environments. At the same time, the contribution of Molinio-Arrhenatheretea (7%) and Papaveretea rhoeadis (7%) increases, reflecting the presence of species typical of secondary grasslands and pastures, and suggesting advancement towards more mature stages of vegetation succession.

Although less represented (4%), the presence of classes such as Stipo-Trachynietea distachyae and Trifolio-Geranietea sanguinei indicates the onset of secondary recolonisation processes and greater ecological heterogeneity induced by the installation of woody material. Altogether, the intervention using logs along drainage lines favoured the establishment of a higher number of species belonging to different syntaxonomic classes, reflecting improved microenvironmental conditions and a progression towards more complex and diversified vegetation stages.

The comparison between the two areas, based on Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, yielded a value of 0.566, indicating a moderate floristic difference between the communities. Although they share a substantial portion of species (approximately 43%), the areas exhibit clear structural divergence linked to differing microenvironmental conditions and distinct successional trajectories. In the unmanaged area, therophytic and nitrophilous elements typical of Chenopodietea and Artemisietea vulgaris dominate, reflecting early successional stages and disturbed environments.

In contrast, the plot with logs displays floristic and functional enrichment, with an increase in species from Helianthematea guttati, Molinio-Arrhenatheretea and Lygeo-Stipetea tenacissimae, as well as shrubs and perennial species belonging to Cytisetea scopario-striati, typical of Mediterranean shrublands, and Trifolio-Geranietea sanguinei, characteristic of hemicryptophytic grasslands.

This composition indicates a more advanced and diversified successional stage in the treated areas, where the retention of woody material in situ promotes the formation of heterogeneous microhabitats and supports progression towards more mature and stable vegetation.

4. Discussion

The flora of the experimental area of Roccaforte del Greco shows a typically Mediterranean composition, dominated by Asteraceae, Poaceae, and Fabaceae (Figure 3), consistent with herbaceous communities developing in thermo-xerophilous, disturbance-prone environments during the post-fire phase [85,86]. In line with recent studies [87,88], this pattern reflects the early colonisation of nutrient-depleted substrates by herbaceous species with high ecological plasticity.

The life forms spectrum (Figure 4), characterised by the predominance of therophytes and hemicryptophytes, indicates an active recolonisation phase following disturbance. As reported by Erfanian et al. [89], therophytes reflect the influence of disturbance factors such as fire and grazing, while hemicryptophytes signal the gradual establishment of perennial species and a progressively stabilising successional process.

These floristic and biological patterns are consistent with succession mediated by the microenvironmental conditions created by the experimental treatment [90]. The transverse arrangement of burned logs reduced runoff velocity and enhanced soil moisture and stabilisation, generating more favourable microsites for vegetation development. Accordingly, NMDS results (Figure 6) show a more homogeneous and temporally stable floristic composition in the central sector of the plot, where the treatment effect is strongest, compared to the more erosion-prone and pioneer-dominated margins.

Beyond their role in reducing runoff and soil erosion, retained burned logs likely influenced post-fire vegetation dynamics through multiple ecological mechanisms. Woody debris can function as an effective seed trap, intercepting diaspores transported by wind or surface runoff and increasing local seed availability, especially in microsites upslope of the logs. In addition, the accumulation of litter and fine organic material around the logs creates favourable conditions for germination by improving soil structure, buffering temperature extremes, and maintaining higher soil moisture. These microsites may also enhance microbial activity and nutrient cycling, increasing nitrogen and carbon availability during the early post-fire phase and ultimately facilitating seedling establishment and the development of more stable, perennial-dominated assemblages in treated areas [91,92].

In this context, the same mechanisms may also affect the establishment dynamics of alien and invasive species. Post-fire environments are highly susceptible to invasions due to open canopy conditions, reduced competition, and nutrient pulses that favour fast-growing, disturbance-adapted taxa [93]. The retention of burned logs may influence alien species establishment in contrasting ways. By trapping diaspores and accumulating litter and fine sediments, logs can enhance propagule retention and create resource-enriched microsites that may facilitate the recruitment of opportunistic alien annuals, particularly along runoff pathways and plot margins. Such patterns are consistent with evidence showing that seed bank dynamics and species-specific fire responses strongly shape post-fire invasion potential [94]. On the other hand, the same structures enhance soil moisture buffering and promote earlier development of continuous native plant cover (including perennial grasses and shrubs), which can reduce the availability of bare ground and limit invasion opportunities through increased competition and shading. In our study area, alien taxa were recorded (e.g., Erigeron bonariensis, Isatis tinctoria subsp. tinctoria, and non-native conifers), yet their overall incidence remained low (6% of the total flora). This suggests that, at least in the short term, log retention did not trigger a marked invasion release, but rather promoted a faster transition towards a more structured community. Alien and exotic species are recognized as an important issue in post-fire management because fire may promote their occurrence and compromise native regeneration [95]. Nevertheless, because alien species responses can be delayed, continued monitoring and early detection are recommended, particularly in edge sectors and microsites where propagule accumulation is most likely.

The practice of leaving or placing logs across drainage lines, widely tested in Mediterranean post-fire ecosystems [96], has proven effective in limiting soil and nutrient loss, reducing surface compaction, and promoting the re-establishment of native vegetation [96,97]. The greater representation of perennial herbaceous species such as Holcus lanatus and Poa sylvicola, along with Fabaceae such as Ornithopus compressus and Trifolium repens, in the central areas is linked to the higher stability of the plot, which favours germination and establishment of Fabaceae, species that, in turn, improve soil fertility through nitrogen enrichment, as also reported by Lucas-Borja et al. [98]. In contrast, more unstable margins are characterised by persistent annual nitrophilous and ruderal elements.

These spatial differences indicate that the log-based treatment fostered a more balanced and differentiated successional trajectory, with greater vegetation cover and reduced erosion in the central sector compared to the margins.

It should be noted that the present study does not include direct measurements of physical or hydrological variables (e.g., soil moisture, erosion rates, or sediment accumulation). Therefore, the ecological mechanisms discussed are inferred from vegetation patterns and supported by existing post-fire literature, and should be interpreted as process-oriented interpretations rather than direct causal evidence.

However, it should be acknowledged that the observed differences derive from a preliminary experimental design based on a single treated plot compared with adjacent unmanaged areas. As a consequence, part of the detected patterns may also reflect local site-specific conditions or edge effects, in addition to the influence of the management intervention itself. The results should therefore be interpreted as indicative of early post-fire successional processes and underlying ecological mechanisms, rather than as definitive causal evidence. Future research should aim to strengthen causal inference by including multiple treated and untreated plots with comparable slope, aspect, burn severity, and stand structure, thereby allowing treatment effects to be disentangled from local environmental variability.

Within this context, delayed invasion responses cannot be excluded, underscoring the importance of continued monitoring, particularly along plot margins and runoff pathways. From a management perspective, the findings allow some preliminary practical considerations to be proposed. The in situ retention of burned logs appears to represent a promising nature-based solution for Mediterranean pine plantations, especially on erosion-prone slopes. Compared to extensive salvage logging, the conservation of residual woody material may support early successional dynamics, promote faster vegetation cover development, and enhance microenvironmental heterogeneity, while simultaneously limiting soil degradation. Nevertheless, given the preliminary nature of this study and its focus on early post-fire successional stages within a single experimental plot, these indications should be regarded as process-oriented guidance rather than prescriptive management recommendations. Overall, while spatial replication and long-term monitoring are required to assess variability, persistence, and scalability across different environmental contexts, the observed patterns provide ecologically meaningful insights into post-fire vegetation recovery processes and contribute to a process-based understanding of post-fire management effectiveness in Mediterranean pine plantations, rather than definitive management prescriptions.

In accordance with Di Biase et al. [99] and López-Alvarado & Farris [100], the chorological results (Figure 5) show that the co-dominance of steno-Mediterranean and eury-Mediterranean elements (totalling 49%) confirms the Mediterranean–xerophilous character of the flora. However, the presence of regional endemics (4%), such as Carlina hispanica subsp. globosa, Pimpinella anisoides, Silene italica subsp. sicula, and Trifolium pratense subsp. semipurpureum, suggests the persistence of microhabitats of high conservation value, indirectly favoured by the action of the logs, which help reduce soil erosion and increase edaphic moisture.

The Shannon index (H = 2.03) indicates an intermediate level of species diversity, consistent with the early stages of secondary succession following a severe disturbance such as fire. Under these conditions, floristic composition tends to be dominated by a limited number of pioneer species capable of rapidly colonising the soil through adaptive strategies such as abundant seed production, heat-stimulated germination, or resprouting from underground organs.

The maximum theoretical diversity (Hmax = 3.81) suggests that the structural potential of the community is not yet fully expressed, while the low evenness value (J = 0.53) confirms a marked imbalance in relative abundances, with a few dominant species exerting strong control over community structure and functioning. These values clearly reflect the recolonisation stage of a plant community undergoing post-fire recovery.

It should be noted that the Shannon diversity and evenness indices are used here exclusively as general descriptive indicators of plant community structure during the early post-fire phase. These metrics were not employed for quantitative or inferential comparisons among treatments, sectors, or sampling dates, but are presented to provide a general framework for interpreting community conditions in the initial stages of post-disturbance succession.

Overall, the results indicate that the vegetation community is undergoing an ecological transition, with recovery dynamics and progressive recolonisation by perennial species potentially leading to increased diversity and structural stability over time, in agreement with patterns observed in other Mediterranean post-fire ecosystems [96,101]. The Cluster Analysis (Figure 8) further highlights the role of topographic and microclimatic variability in differentiating plant communities, confirming the importance of environmental gradients in structuring Mediterranean biodiversity [102].

The analysis of pressures and threats (Table 1) shows that the ecological structure of the study area is primarily shaped by the interaction between traditional anthropogenic pressures, natural processes, and emerging climate-related factors. Agro-pastoral activities represent the main disturbance drivers, with extensive grazing, agricultural burning (codes A10, A11), and arson fires (H4) exerting high levels of pressure and threat, consistent with their documented role in driving vegetation degradation and regressive successional cycles in Mediterranean ecosystems [35,102,103]. In contrast, infrastructure-related modifications (E01, F02), road development, and waste management (F09) currently show low pressure and threat levels, indicating a more limited and localized impact [104].

Among the most critical factors is the presence of invasive alien species (6% of the total flora, Figure 5) (I02), which represent one of the fastest-expanding threats in Mediterranean regions [105,106]. The alien taxa recorded in the area, including Cryptomeria japonica, Cupressus sempervirens, Erigeron bonariensis, Isatis tinctoria subsp. tinctoria, as well as Pinus pinaster subsp. pinaster and Pinus radiata, may interfere with successional processes and alter competitive dynamics, fostering floristic homogenisation and reducing local biodiversity [107]. Their high pressure and threat levels are consistent with the vulnerability of post-fire environments, a phase in which recolonisation can be rapidly monopolised by competitive or alien taxa [91,108,109].

Natural abiotic processes (L01), such as erosion, desiccation, and sedimentation, show medium–high impact. These processes are particularly relevant in Mediterranean landscapes characterised by steep slopes and incoherent substrates, where the loss of vegetation cover following fire greatly increases the risk of geomorphological instability [22,23,49].

Climatic factors (N01, N02) indicate an increasing pressure on Mediterranean plant communities, with rising temperatures and decreasing precipitation exerting medium to high impacts on ecosystem stability. These climate-driven changes can alter species phenology, intensify drought stress, and increase fire probability, producing cumulative effects on habitats and successional dynamics [110]. Overall, the analysed communities are exposed to multiple and potentially synergistic pressures, resulting from the interaction of traditional disturbances (grazing and fire), emerging threats such as invasive species, and ongoing climatic changes. This combination represents a major vulnerability driver, whose mitigation requires integrated and multisectoral management approaches [102,109,110].

The analysis of syntaxonomic composition, based on the classification proposed by Mucina et al. [82], highlights significant differences between the vegetation of the relevés conducted across the study area and that of the experimental plot treated with fallen logs retained in situ. The species recorded throughout the study area belong to 17 phytosociological classes (Table 2), a figure that confirms the site’s floristic diversity and allows the treatment’s effects on the syntaxonomic spectrum to be clearly assessed.

Overall, the most represented classes in the relevés from the entire study area, Chenopodietea and Quercetea pubescentis, reflect two distinct yet complementary ecological components of the post-fire landscape. The former, composed of ephemeral and nitrophilous therophytes, is typical of disturbed and recolonising environments where soils remain rich in mineral nutrients but lack stable vegetation cover [42]. The latter includes elements of mesophilous and thermophilous deciduous oak forests, representing the more mature and stable stages of the potential dynamic series in this Mediterranean area. In unmanaged sectors, this coexistence of ruderal and forest communities reflects the characteristic mosaic of Mediterranean post-fire landscapes, where vegetation recovery proceeds through heterogeneous phases shaped by microtopography, water availability, and the soil seed bank [101,111].

The classes Artemisietea vulgaris and Cytisetea scopario-striati, occupying intermediate positions, represent transitional communities between pioneer stages and more evolved shrub-dominated phases, often associated with well-drained soils and sunny exposures.

Conversely, in the more open and arid sectors, communities belonging to Helianthematea guttati are observed, consisting of ephemeral annual, xerophilous and thermophilous species with short winter–spring cycles and non-nitrophilous preferences, typical of poor, highly exposed environments, also found in sectors adjoining the study area. Species characteristic of Sisymbrietea are also present, representing ephemeral nitrophilous and semi-nitrophilous ruderal vegetation, attributable to the proximity of anthropogenic areas used for agricultural purposes.

Within the experimental plot, the syntaxonomic pattern changes markedly, with a noticeable increase in the classes Chenopodietea (26%), Helianthematea guttati (18%), Sisymbrietea (12%), and Papaveretea rhoeadis (7%). The higher representation of these classes indicates that the treatment likely favoured microhabitats conducive to colonisation and to the rapid establishment of herbaceous cover composed of species associated with anthropogenic environments [92,96].

The increase in Molinio-Arrhenatheretea (7%) is consistent with secondary regeneration dynamics in herbaceous and grassland communities, as reported in studies of post-fire recovery in Mediterranean regions [112]. In this sense, the installation of woody material appears to have facilitated vegetation recolonisation by creating greater ecological heterogeneity and promoting the transition from ruderal communities to more complex mosaics in which pioneer species coexist with longer-lived taxa [112,113].

The Bray–Curtis dissimilarity of 56.6% indicates a moderate compositional divergence between the two communities, attributable to the microenvironmental effects generated by the woody material retained in situ. This treatment not only increases species richness but also improves the structure and organisation of the plant community, with positive effects on ecological recovery processes. Several studies underline that the conservation of residual woody components (woody legacies) is a key factor in preventing vegetation simplification and the consequent loss of essential ecosystem functions [114].

The persistence of burned logs left in situ proved to be an effective ecological management tool, as dead wood contributes to soil stabilization and increases microenvironmental heterogeneity by enhancing water retention and the accumulation of organic matter [92,96,115]. These effects improve conditions for the germination and establishment of pioneer species while also facilitating the onset of later stages of secondary succession, as documented in several studies conducted in post-fire forest environments and degraded substrates [114,116,117].

Numerous studies indicate that the retention of woody material is associated with faster regeneration dynamics compared to salvage-logged areas, where wood removal may slow succession and increase erosion [118,119,120]. In this respect, the experience at Roccaforte del Greco is consistent with Mediterranean nature-based solutions, suggesting that the conservation of dead wood in situ can contribute to integrating ecological recovery with hydrogeomorphological risk mitigation [121,122,123].

More broadly, wildfire acted as a disturbance capable of promoting the renaturalisation of artificial stands. Despite its short-term negative effects, fire may, in the medium term, play a role comparable to silvicultural thinning by reducing stand density and competitive pressure and favouring the re-establishment of potential natural vegetation [2,36,51]. Accordingly, fire-induced canopy opening and structural reorganisation can facilitate native species recolonisation and initiate more natural successional pathways than those observed in unmanaged artificial stands [114,116,117,124]. Overall, the findings should be interpreted within the context of early post-fire succession and as a contribution to a process-oriented understanding of post-fire management effectiveness, rather than as definitive management prescriptions.

5. Conclusions

This study suggests that retaining burned logs in situ may represent an effective nature-based solution to support post-fire recovery in Mediterranean pine forests. Floristic, vegetational and syntaxonomic analyses show that the treated plot differs clearly from the unmanaged area, exhibiting greater microenvironmental heterogeneity, higher functional diversity, and a more structured plant composition. These differences are reflected in multivariate analyses and diversity patterns, indicating that the stabilising effect of the logs, through reduced erosion and enhanced water retention, is associated with early successional processes, facilitating both pioneer and perennial species. The moderate dissimilarity observed between treated and untreated areas suggests that log retention may influence successional trajectories, contributing to the development of more complex and resilient communities.

Importantly, the results presented here derive from a preliminary study conducted within a single experimental plot and primarily reflect early post-fire successional responses under site-specific environmental and management conditions.

In a context characterised by recurrent anthropogenic pressures, alien species, and climatic stressors, the conservation of residual woody material emerges as a sustainable practice capable of integrating soil protection with biodiversity enhancement. Overall, these findings should therefore be interpreted as process-oriented evidence directly derived from the observed floristic and structural patterns, rather than as definitive management prescriptions. Long-term monitoring will be necessary to assess the persistence of the observed effects and the evolution of plant communities over time.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.L.A.L., G.B., C.M.M., A.R.P. and G.S.; methodology, V.L.A.L., G.B., C.M.M., A.R.P. and G.S.; software, V.L.A.L.; validation, V.L.A.L., G.B., C.M.M., A.R.P. and G.S.; formal analysis, V.L.A.L. and G.S.; investigation, V.L.A.L., G.B., C.M.M., A.R.P. and G.S.; resources, V.L.A.L., G.B., C.M.M., A.R.P. and G.S.; data curation, V.L.A.L. and G.S.; writing—original draft preparation, V.L.A.L. and G.S.; writing—review and editing, V.L.A.L., G.B., C.M.M., A.R.P. and G.S.; visualization, V.L.A.L., G.B., C.M.M., A.R.P. and G.S.; supervision, G.B., C.M.M., A.R.P. and G.S.; project administration, G.B., A.R.P. and G.S.; funding acquisition, G.B., A.R.P. and G.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the project: “Tech4You—Technologies for climate change adaptation and quality of life improvement”; was assigned the identification n. ECS00000009, CUP C33C22000290006, this work is part of SPOKE 3 goal 3 PP 2.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data used in the study can be obtained upon request from a corresponding author. The data is not publicly available due to its usage in the ongoing study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest and the funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Keeley, J.E.; Fotheringham, C.J.; Baer-Keeley, M. Determinants of postfire recovery and succession in Mediterranean-climate shrublands of California. Ecol. Appl. 2005, 15, 1515–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E.; Pausas, J.G.; Rundel, P.W.; Bond, W.J.; Bradstock, R.A. Fire as an evolutionary pressure shaping plant traits. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 406–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, S.D.; Dixon, K.W.; Hopper, S.D.; Lambers, H.; Turner, S.R. Little evidence for fire-adapted plant traits in Mediterranean climate regions. Trends Plant Sci. 2011, 16, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Breman, E.; Gillson, L.; Willis, K. How fire and climate shaped grass-dominated vegetation and forest mosaics in northern South Africa during past millennia. Holocene 2012, 22, 1427–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rita, F.; Ghilardi, M.; Fagel, N.; Vacchi, M.; Warichet, F.; Delanghe, D.; Sicurani, J.; Martinet, L.; Robresco, S. Natural and anthropogenic dynamics of the coastal environment in northwestern Corsica (western Mediterranean) over the past six millennia. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2022, 278, 107372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, R.E.; Yang, Z.; Cohen, W.B.; Pfaff, E.; Braaten, J.; Nelson, P. Spatial and temporal patterns of forest disturbance and regrowth within the area of the Northwest Forest Plan. Remote Sens. Environ. 2012, 122, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoleni, S.; Esposito, A. Vegetation Regrowth After Fire and Cutting of Mediterranean Macchia Species. In Fire in Mediterranean Ecosystems, 1st ed.; Trabaud, L., Prodon, R., Eds.; Commission of the European Communities: Brussels, Belgium, 1993; pp. 87–99. [Google Scholar]

- Tessler, N.; Wittenberg, L.; Greenbaum, N. Vegetation cover and species richness after recurrent forest fires in the Eastern Mediterranean ecosystem of Mount Carmel, Israel. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 1395–1402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cueto, D.A.; Alaniz, A.J.; Hidalgo-Corrotea, C.; Vergara, P.M.; Carvajal, M.A. Chilean Mediterranean forest on the verge of collapse? Evidence from a comprehensive risk analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 964, 178557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriondo, M.; Good, P.; Durao, R.; Bindi, M.; Giannakopoulos, C.; Corte-Real, J. Potential impact of climate change on fire risk in the Mediterranean area. Clim. Res. 2006, 31, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riera, P.; Peñuelas, J.; Farreras, V.; Estiarte, M. Valuation of climate-change effects on Mediterranean shrublands. Ecol. Appl. 2007, 17, 91–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lionello, P.; Scarascia, L. The relation between climate change in the Mediterranean region and global warming. Reg. Environ. Change 2018, 18, 1481–1493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, L.T.; Giljohann, K.M.; Duane, A.; Aquilué, N.; Archibald, S.; Batllori, E.; Bennett, A.F.; Buckland, S.T.; Canelles, Q.; Clarke, M.F.; et al. Fire and biodiversity in the Anthropocene. Science 2020, 370, eabb0355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salesa, D.; Baeza, M.J.; Santana, V.M. Fire severity and prolonged drought do not interact to reduce plant regeneration capacity but alter community composition in a Mediterranean shrubland. Fire Ecol. 2024, 20, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pongratz, J.; Reick, C.; Raddatz, T.; Claussen, M. A reconstruction of global agricultural areas and land cover for the last millennium. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 2008, 22, GB3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Rein, G.; Martin, D. Past and present post-fire environments. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 573, 1275–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steel, Z.L.; Foster, D.; Coppoletta, M.; Lydersen, J.M.; Stephens, S.L.; Paudel, A.; Markwith, S.H.; Merriam, K.; Collins, B.M. Ecological resilience and vegetation transition in the face of two successive large wildfires. J. Ecol. 2021, 109, 3340–3355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P.; Francos, M.; Brevik, E.C.; Ubeda, X.; Bogunovic, I. Post-fire soil management. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health 2018, 5, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spada, E.; Falcone, G.; Praticò, S.; Benedetto, M.C.; Gulisano, G.; De Luca, A.I. Wildfires’ cost for societal welfare: Economic evaluation of forestry ecosystem services losses in Southern Italy. Land Degrad. Dev. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrelja, I.; Šestak, I.; Bogunović, I. Wildfire impacts on soil physical and chemical properties—A short review of recent studies. Agric. Conspec. Sci. 2020, 85, 293–301. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira, M.G.; Fernandes, L.S.; Carvalho, S.; Santos, R.B.; Caramelo, L.; Alencoão, A. Modelling the impacts of wildfires on runoff at the river basin ecological scale in a changing Mediterranean environment. Environ. Earth Sci. 2016, 75, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombino, G.; Barbaro, G.; Pérez-Cutillas, P.; D’Agostino, D.; Denisi, P.; Foti, G.; Zimbone, S.M. Use of logs downed by wildfires as erosion barriers to encourage forest auto-regeneration: A case study in Calabria, Italy. Water 2023, 15, 2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bombino, G.; D’agostino, D.; Marziliano, P.A.; Pérez-Cutillas, P.; Praticò, S.; Proto, A.R.; Manti, L.M.; Lofaro, G.; Zimbone, S.M. A nature-based approach using felled burnt logs to enhance forest recovery post-fire and reduce erosion phenomena in the Mediterranean area. Land 2024, 13, 236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Raga, M.; Palencia, C.; Keesstra, S.; Jordán, A.; Fraile, R.; Angulo-Martínez, M.; Cerdà, A. Splash erosion: A review with unanswered questions. Earth Sci. Rev. 2017, 171, 463–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puig-Gironès, R.; Brotons, L.; Pons, P. Aridity, fire severity and proximity of populations affect the temporal responses of open-habitat birds to wildfires. Biol. Conserv. 2022, 272, 109661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, X.; Chergui, B.; Belliure, J.; Moreira, F.; Pausas, J.G. Reptile responses to fire across the western Mediterranean Basin. Conserv. Biol. 2025, 39, e14326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González, T.M.; González-Trujillo, J.D.; Muñoz, A.; Armenteras, D. Effects of fire history on animal communities: A systematic review. Ecol. Process. 2022, 11, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandström, J.; Emilsson, T.; Nilsson, U.; Günther, T.; Åström, M. Effects of dead wood manipulation on saproxylic insects and fungal communities in managed boreal forests. J. Appl. Ecol. 2019, 56, 1572–1583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, E.; Vahlström, I.; Dahlberg, A.; Magnusson, M.; Löfroth, T. Wildfires provide more diverse habitats than prescribed burns for saproxylic beetles and wood decay fungi in Swedish boreal landscapes. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 395, 127956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwörer, C.; Morales-Molino, C.; Gobet, E.; Henne, P.D.; Pasta, S.; Pedrotta, T.; Leeuwen, J.F.N.; Vannière, B.; Tinner, W. Simulating past and future fire impacts on Mediterranean ecosystems. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 954–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega, M.; Lora, Á.; Yocom, L.; Zumaquero, R.; Molina, J.R. Effects of fire recurrence and severity on Mediterranean vegetation dynamics: Implications for structure and composition in southern Spain. Sci. Total Environ. 2025, 961, 178392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Keeley, J.E. Wildfires as an ecosystem service. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2019, 17, 289–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhk, C.; Götzenberger, L.; Wesche, K.; Gómez, P.S.; Hensen, I. Post-fire regeneration in a Mediterranean pine forest with historically low fire frequency. Acta Oecol. 2006, 30, 288–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culbert, S.G.; Arthur, M.A.; Cotton, C.A.; Muller, J.J. Higher severity fire increases the long-term competitiveness of pyrophytes in an upland oak–pine forest, Kentucky, USA. Fire Ecol. 2025, 21, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeley, J.E.; Bond, W.J.; Bradstock, R.A.; Pausas, J.G.; Rundel, P.W. (Eds.) Fire in Mediterranean Ecosystems: Ecology, Evolution and Management, 1st ed.; Cambridge University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Pausas, J.G.; Keeley, J.E. Evolutionary ecology of resprouting and seeding in fire-prone ecosystems. New Phytol. 2014, 204, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Keeley, J.E. A burning story: The role of fire in the history of life. BioScience 2009, 59, 593–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallejo, V.R.; Allen, E.B.; Aronson, J.; Pausas, J.G.; Cortina, J.; Gutiérrez, J.R. Restoration of Mediterranean-Type Woodlands and Shrublands. In Restoration Ecology: The New Frontier, 2nd ed.; Van Andel, J., Aronson, J., Eds.; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2012; pp. 130–144. [Google Scholar]

- Keeley, J.E.; Fotheringham, C.J. Role of Fire in Regeneration from Seed. In Seeds: The Ecology of Regeneration in Plant Communities, 2nd ed.; Fenner, M., Ed.; CABI Publishing: Wallingford, UK, 2000; pp. 311–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, S.; Arianoutsou, M.; Kazanis, D.; Tavsanoglu, Ç.; Lloret, F.; Buhk, C.; Ojeda, F.; Luna, B.; Moreno, J.M.; Rodrigo, A.; et al. Fire-related traits for plant species of the Mediterranean Basin: Ecological Archives E090-094. Ecology 2009, 90, 1420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paneghel, M.; Torné, G.; Morin, X.; Alday, J.G.; Coll, L. Increasing temperature threatens post-fire autosuccessional dynamics of a Mediterranean obligate seeder. J. Ecol. 2024, 112, 2929–2943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudena, M.; Santana, V.M.; Baeza, M.J.; Bautista, S.; Eppinga, M.B.; Hemerik, L.; Mayor, A.G.; Rodriguez, F.; Valdecantos, A.; Vallejo, V.R.; et al. Increased aridity drives post-fire recovery of Mediterranean forests towards open shrublands. New Phytol. 2020, 225, 1500–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tapias, R.; Climent, J.; Pardos, J.A.; Gil, L. Life histories of Mediterranean pines. Plant Ecol. 2004, 171, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Bladé, C.; Valdecantos, A.; Seva, J.P.; Fuentes, D.; Alloza, J.A.; Vilagrosa, A.; Bautista, S.; Cortina, J.; Vallejo, R. Pines and oaks in the restoration of Mediterranean landscapes of Spain: New perspectives for an old practice—A review. Plant Ecol. 2004, 171, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pausas, J.G.; Bradstock, R.A.; Keith, D.A.; Keeley, J.E.; GCTE Fire Network. Plant functional traits in relation to fire in crown-fire ecosystems. Ecology 2004, 85, 1085–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paula, S.; Pausas, J.G. Burning seeds: Germinative response to heat treatments in relation to resprouting ability. J. Ecol. 2008, 96, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Delgado, R.; Lloret, F.; Pons, X.; Terradas, J. Satellite evidence of decreasing resilience in Mediterranean plant communities after recurrent wildfires. Ecology 2002, 83, 2293–2303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermitão, T.; Gouveia, C.M.; Bastos, A.; Russo, A.C. Recovery following recurrent fires across Mediterranean ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2024, 30, e70013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakesby, R.A. Post-wildfire soil erosion in the Mediterranean: Review and future research directions. Earth Sci. Rev. 2011, 105, 71–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INFC. Statistiche INFC 2015; Principali caratteristiche dei boschi italiani, Inventario Nazionale delle Foreste e dei Serbatoi Forestali di Carbonio (INFC); CREA–Foreste e Legno: Roma, Italy, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mercurio, R. La Rinnovazione dei Popolamenti Forestali. In Restauro della Foresta Mediterranea; Scarascia Mugnozza, G., Ed.; Accademia Nazionale delle Scienze: Roma, Italy, 2010; pp. 1000–1010. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, G.; Silva, J.M.; Oom, D.; Modica, G. Combined use of Sentinel-1 and Sentinel-2 for burn severity mapping in a Mediterranean region. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Science and Its Applications, Cagliari, Italy, 13–16 September 2021; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 139–154. [Google Scholar]

- De Luca, G.; Modica, G. Canopy fire effects estimation using Sentinel-2 imagery and deep learning approach—A case study on the Aspromonte National Park. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Applied Intelligence and Informatics, Olten, Switzerland, 5–7 September 2022; Springer Nature Switzerland: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 403–417. [Google Scholar]

- Oliva, M.; Maffia, A.; Marra, F.; Canino, F.; Battaglia, S.; Mallamaci, C.; Muscolo, A. The complex impacts of fire on soil ecosystems: Insights from the 2021 Aspromonte National Park wildfire. J. For. Res. 2025, 36, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- QGIS Development Team. QGIS Geographic Information System, Version 3.26.3. Open Source Geospatial Foundation Project. QGIS: Bern, Switzerland, 2022. Available online: https://qgis.org (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Google. Google Satellite Imagery; © Google. 2025. Available online: https://www.google.com/maps (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Centro Funzionale Multirischi—Calabria. Consultazioni Banca Dati Storici. Available online: https://www.cfd.calabria.it/index.php/dati-stazioni/dati-storici (accessed on 18 November 2025).

- Walter, H.; Lieth, H.; Rehder, H.; Harnickell, E. Klimadiagramm—Weltatlas; G. Fischer: Jena, Germany, 1960; p. 103. [Google Scholar]

- Pesaresi, S.; Galdenzi, D.; Biondi, E.; Casavecchia, S. Bioclimate of Italy: Application of the worldwide bioclimatic classification system. J. Maps 2014, 10, 538–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Sánchez, M.E.; Navidi, M.; Ortega, R.; Soria, R.; Miralles, I.; Carmona-Yáñez, M.D.; Lucas-Borja, M.E. Medium-term associations of soil properties and plant diversity in a semi-arid pine forest after post-wildfire management. For. Ecol. Manag. 2023, 545, 121163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ercole, S.; Giacanelli, V.; Bacchetta, G.; Fenu, G.; Genovesi, P. (Eds.) Manuali per il Monitoraggio di Specie e Habitat di Interesse Comunitario (Direttiva 92/43/CEE) in Italia: Specie Vegetali; Serie Manuali e Linee Guida 140/2016; ISPRA: Roma, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]