Abstract

This study investigates how gender-inclusive leadership and trade integration shape environmental sustainability in China, addressing a key gap in the literature where most prior work has focused on aggregate governance, finance, or growth without considering how gender representation in leadership and trade openness jointly relate to environmental outcomes. China provides a particularly relevant setting because it is both a leading global emitter and one of the world’s most trade-integrated and rapidly growing economies, so changes in leadership structures, financial deepening, and external openness can have sizable environmental consequences. Given the nonlinear and non-normal nature of the variables, the analysis relies on nonlinear econometric tools, specifically quantile-on-quantile ARDL and Quantile Granger Causality, applied to quarterly data from 1998Q1 to 2024Q4. The results show that the impact of gender-inclusive leadership on environmental sustainability is state-dependent, with improvements at lower environmental pressure but a predominantly negative long-run association at mid to upper quantiles, while financial development tends to support sustainability, and economic growth and trade openness are generally linked to lower sustainability across much of the quantile range. By narrowing the research gap on gender-inclusive leadership and explicitly motivating China as a critical case, this study offers context-specific evidence that can guide policies aimed at fostering inclusive leadership and greener finance while carefully managing the environmental consequences of rapid growth and deeper trade integration.

1. Introduction

Across emerging economies, environmental sustainability is increasingly treated as a core policy concern, with China offering a prominent example of both the scale of environmental pressures and the strength of the policy response. Decades of sustained economic expansion have made China the second-largest economy globally, yet this growth has generated serious environmental repercussions, from intensified resource use and pollution to ecosystem degradation [1]. The authorities have reacted by integrating environmental priorities into the Ecological Civilization agenda and by setting clear milestones to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 [2,3]. Achieving these targets will require more than technological innovation and industrial restructuring; it will also depend on the influence of social structures and financial systems on environmental outcomes. In particular, two dimensions that have received limited attention—female participation in leadership (FP) and financial development (FD)—may significantly shape the trajectory of sustainability.

The core research gap is the incomplete, piecemeal understanding of how FP and financial development (FD) jointly shape environmental sustainability (ES) in China. Evidence from gender–sustainability research indicates that GIL emphasizes long-term welfare, inclusion, and environmental stewardship [1,4], yet structural barriers and heterogeneous institutions can dilute its influence and make effects uneven [5,6]. FD likewise cuts both ways: With robust regulation, it mobilizes capital for clean energy and innovation, but under weak governance, it can fund polluters or enable “greenwashing” [7,8]. Despite China’s advances in gender inclusion and financial reform, no study has systematically assessed the combined effects of GIL and FD on ES using holistic sustainability metrics. This omission constrains the policy toolkit for balancing economic, social, and environmental objectives.

The existing literature provides useful but incomplete insights. For instance, ref. [1] documents China’s efforts to integrate women into ecological governance but cautions that institutional constraints prevent these efforts from fully translating into outcomes. Comparative studies such as [2] confirm that female parliamentarians positively influence sustainability, but mostly in cultural contexts supportive of gender inclusivity. Similarly, studies on FD highlight that while deepening financial systems can support clean energy adoption and green innovation [3], global evidence also warns that FD often worsens environmental degradation, especially in the absence of strong regulations [4,5]. This mixed evidence underscores the need to study FP and FD together within a Chinese context, where institutional reforms, industrial transformation, and ecological goals intersect in complex ways. Based on the above information, the following research questions are formulated as follows:

- (1)

- What is the effect of female participation on environmental sustainability?

- (2)

- Does trade foster environmental sustainability?

- (3)

- What is the nexus between financial development and environmental sustainability?

- (4)

- How does economic growth impact environmental sustainability?

This study advances empirical practice by employing quantile-on-quantile ARDL (QQARDL), which identifies heterogeneous effects across the full distribution of environmental sustainability rather than at a single central tendency. By jointly modeling gender-inclusive leadership, trade openness, financial development, and economic growth in low-, mid-, and high-sustainability states, QQARDL reveals pronounced nonlinearities and asymmetries that mean-based estimators miss. The policy takeaway is straightforward: Interventions should be sequenced and sized to current sustainability conditions—measures that succeed in the upper tail may underperform or backfire in the lower tail. Distribution-aware evidence equips Chinese authorities with a toolkit for context-specific, stage-contingent design and offers a reference point for peers aiming to align trade and finance expansion with lasting environmental outcomes through gender-inclusive governance.

2. Theoretical Framework and Empirical Review

2.1. Theoretical Framework

Viewing environmental sustainability through the sustainable development lens requires integrating economic, financial, and social determinants into a single analytical frame and linking each determinant to an expected impact on environmental outcomes. Female participation in leadership—supported by gender and sustainability theories—is expected to improve environmental sustainability because greater representation widens the range of perspectives, reinforces ethical accountability, and aligns decisions with community-centered and long-term priorities. Accordingly, when ES is proxied by emissions (where lower values indicate better sustainability), we anticipate a negative coefficient on female leadership, reflecting its role in reducing environmental pressure [6,7,8]. This is consistent with the SDGs, particularly SDG 5 (Gender Equality) and SDG 13 (Climate Action), which stress that inclusive decision-making is instrumental for achieving durable environmental gains.

Trade openness (TD), grounded in globalization and ecological modernization, has an inherently ambiguous theoretical sign. The pollution haven hypothesis implies that greater TD can worsen environmental sustainability (a positive coefficient on emissions-based ES), as liberalized trade may attract pollution-intensive industries to countries with weaker environmental regulations [3,5]. By contrast, the ecological modernization perspective suggests that trade integration can improve sustainability (a negative coefficient on emissions-based ES) through channels such as technology transfer, diffusion of cleaner production practices, and the adoption of international environmental standards [9]. Thus, we treat the expected impact of TD on ES as context-dependent, allowing for both risk- and opportunity-driven effects.

Within sustainability frameworks, financial development (FD) is conceptualized as a key allocator of resources, and its sign is theory-driven. When FD supports green finance—directing credit toward renewable energy, environmental innovations, and clean technologies—it is expected to enhance environmental sustainability, implying a negative coefficient on emissions-based ES [8,10]. However, if financial deepening primarily channels funds into carbon-intensive sectors and fossil-fuel-based infrastructure, FD can undermine sustainability, leading to a positive coefficient on emissions-based ES [11]. Our framework, therefore, anticipates that the sign of FD will depend on whether financial resources are steered toward low- or high-carbon activities.

Finally, economic growth (EG) is interpreted through the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) and ecological economics. At early stages of development, rising income typically increases pollution and resource use, implying a positive relationship between EG and emissions-based ES (i.e., growth reduces environmental sustainability). At higher income levels, if accompanied by technological upgrading, stricter regulation, and structural shifts toward cleaner sectors, EG may eventually improve ES, generating a negative coefficient on emissions-based measures [12]. Critics, however, argue that in many emerging economies—particularly those dependent on fossil fuels—this turning point does not materialize within the observed period, so growth continues to be associated with environmental degradation [10]. In such settings, we expect EG to exert a predominantly harmful effect on ES, reflected in a positive estimated coefficient when ES is proxied by emissions.

2.2. Empirical Review

The evidence on the nexus between female participation in leadership (FP) and environmental sustainability (ES) is growing, yet findings remain nuanced across contexts, sectors, and methodological approaches. The authors of [13], using panel data from 237 energy firms (2012–2022), reveal that female CEOs generally enhance environmental innovation, though board chairs have mixed impacts, highlighting the importance of positional influence within leadership structures. The authors of [14] extend this evidence to the hospitality and tourism sector (2017–2021), showing a positive link between FP and ES, consistent with [11], who finds that Nordic firms with female leaders display stronger ESG outcomes. At the cross-national level, ref. [2] demonstrates, using 2SLS techniques across 18 countries over two decades, that female parliamentarians positively influence environmental performance, particularly in institutional and cultural contexts supportive of sustainability. Similarly, ref. [15], based on survey data from 500 Indonesian respondents, finds that greater female political participation enhances pro-environmental behaviors and policies. Evidence from qualitative inquiry, such as [7] in Italian firms, corroborates these results, showing that women leaders promote sustainable practices through inclusive and collaborative approaches. However, the relationship is not uniformly positive: ref. [16], using Indian panel data (2006–2016), shows mixed results, where female leadership reduces crop burning and improves air quality in some contexts but has limited or negative effects in others, reflecting structural and institutional barriers. Table 1 presents a summary of findings (female participation and environmental sustainability).

Table 1.

Summary of findings (female participation and environmental sustainability).

The empirical literature on the relationship between financial development (FD) and environmental sustainability (ES) presents mixed and often context-specific results, reflecting differences in institutional quality, economic structures, and stages of development. For instance, ref. [17], using time-series ARDL bounds testing for China (1953–2006), finds that FD enhances ES by facilitating cleaner technologies and efficient resource allocation. Similarly, ref. [18] demonstrates, through a system GMM panel of 24 transition economies (1993–2004), that FD contributes positively to ES when combined with good governance and institutional support. Consistent with this, ref. [3] reports that, in Indonesia (1975–2011), FD improves ES in the long run, highlighting the role of financial resources in supporting green investments. In Turkey, ref. [19] shows a bidirectional relationship between FD and ES (1960–2007), suggesting a feedback loop where finance and sustainability reinforce each other. However, the evidence is not uniformly positive. The authors of [5], applying a simultaneous-equation panel model for 12 MENA countries (1990–2011), find no significant link between FD and ES, pointing to weak institutional and regulatory environments that undermine finance’s potential to drive sustainability. The authors of [4], analyzing 155 countries from 1990 to 2014, further highlight this heterogeneity, finding that FD tends to deteriorate ES globally, though its negative effect is less pronounced in developed economies. In the U.S., ref. [20] identifies a neutral but bidirectional link (1960–2010), suggesting that FD and ES move together but without a consistent causal pattern. Table 2 presents a summary of findings (financial development and environmental sustainability).

Table 2.

Summary of findings (financial development and environmental sustainability).

The literature examining the link between economic growth (EG) and environmental sustainability (ES) highlights a complex and often contradictory relationship, shaped by national context, development stages, and methodological approaches. Ref. [21], analyzing 20 countries between 1990 and 2019, shows that growth generally reduces ES, reflecting the environmental costs of expansion even in countries with relatively sustainable practices. Similarly, ref. [22], using a non-linear MS-VAR model for China (1996–2019), finds that EG negatively impacts ES, especially in medium-growth regimes where industrial activity dominates. A global review by [23] reinforces this narrative, emphasizing that while growth has historically improved material welfare, it consistently imposes ecological trade-offs, thereby questioning the sustainability of growth-led models. However, some studies identify partial evidence of decoupling. Ref. [24], through decoupling analysis of Eastern European economies (1998–2017), reports that growth both weakens and strengthens ES depending on institutional quality, technology adoption, and the stage of transition. Ref. [25] also highlights heterogeneity in 15 African countries, finding that while growth increases environmental pressures in the short run, some evidence of improvement emerges at higher levels of income, in line with the EKC hypothesis. Table 3 presents a summary of findings (economic growth and environmental sustainability)

Table 3.

Summary of findings (economic growth and environmental sustainability).

The relationship between trade openness (TD) and environmental sustainability (ES) has been widely studied, and findings remain mixed, reflecting variations in economic structures, regulatory contexts, and methodological approaches. Ref. [26], applying panel quantile regressions to 64 nations (2001–2019), found that greater openness generally worsens ES, consistent with the pollution haven hypothesis. By contrast, ref. [27] used Bayesian model averaging across 64 developing countries (2000–2022) and revealed both positive and negative effects, highlighting the heterogeneity of outcomes across regions. Evidence from Europe, such as ref. [28] covering EU-15 economies (1980–2022) with ARDL methods, also shows a dual impact where trade sometimes promotes sustainability through technology transfer but, in other cases, worsens emissions through industrial expansion. Similarly, ref. [9] reports the insignificant effects of trade on ES in BRICS countries (1991–2019), suggesting that growth and institutional quality overshadow trade’s role. More nuanced insights emerge from threshold and dynamic panel approaches: refs. [29,30] report that in BRICS+T and Asian developing countries, respectively, TD can harm ES below certain regulatory or technological thresholds but may contribute positively once cleaner technologies or stronger environmental standards are in place. Sun et al. (2019), analyzing 49 high-emission Belt and Road countries (1991–2014), also document this duality, showing that trade worsens emissions in the short run but fosters improvements when coupled with renewable energy adoption [31]. Finally, ref. [32], in a panel of 53 nations (1990–2019), emphasized the negative long-run effect of trade on sustainability, confirming that openness without stringent environmental frameworks aggravates ecological pressures. Table 4 presents a summary of findings (trade and environmental sustainability).

Table 4.

Summary of findings (trade and environmental sustainability).

2.3. Gap in the Literature

A consistent shortcoming appears in existing studies on female leadership, financial development, economic growth, and trade openness in relation to environmental sustainability. Most analyses rely on methods that focus on averages or, at best, estimate conditional quantiles only for the sustainability outcome while treating the explanatory variables as if their effects were uniform across their own distributions. This design cannot show whether the impact of trade openness at high levels differs from its impact at low levels or whether the influence of female leadership and finance changes when sustainability is weak versus strong. In practice, this smooths over nonlinearities and asymmetries that are likely to be central to how these drivers shape environmental outcomes.

To overcome this limitation, the present study turns to quantile-on-quantile frameworks such as QQARDL. These methods allow the researcher to link different quantiles of the predictors to different quantiles of environmental sustainability, capturing how the effect of a variable like trade openness or financial development varies across both its own distribution and the state of the environment. By jointly tracing these state-contingent interactions, QQARDL provides a richer and more realistic picture of the policy space. This deeper view is crucial for designing targeted interventions that acknowledge that the same policy lever can behave very differently under low, medium, or high levels of both the driving variables and environmental pressure.

2.4. Conceptual Framework

The conceptual framework views environmental sustainability, ES, as the outcome of intertwined social, economic, and financial forces shaped by female participation in leadership, FP; trade openness, TD; financial development, FD; and economic growth, EG. Higher FP is expected to support ES because more women in decision-making typically bring stronger attention to social welfare, ethical responsibility, and long-term risk management, which can translate into stricter environmental oversight and greater support for green investment. TD affects ES through both harmful and beneficial pathways, since greater integration with global markets can, under weak regulation, attract pollution-intensive production yet, at the same time, can facilitate access to cleaner technologies, international standards, and greener management practices, so its net effect depends on the domestic institutional and regulatory context. FD functions as a central channel for allocating resources and can improve ES when banks and capital markets expand credit for renewable energy, environmental innovation, and low-carbon infrastructure, but it can also weaken ES when financial deepening mainly fuels fossil fuel expansion and carbon-intensive industries. EG shapes ES through expansion in scale, shifts in economic structure, and technological change, so in early stages of development, growth often raises emissions and resource use, while at more advanced stages where regulatory capacity and clean technology adoption are stronger, growth can be associated with gradual improvements in ES. Taken together, the framework suggests that the environmental trajectory of an economy does not depend on growth or openness alone but on how leadership is composed, how finance is steered, and whether the gains from trade and growth are systematically aligned with low-carbon and socially inclusive development. Figure 1 presents the theoretical framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

3. Data and Methods

3.1. Data

This study explores the drivers of environmental sustainability in China using quarterly data from 1998Q1 to 2024Q4. The sample period begins in 1998 due to the lack of data on female participation in leadership prior to that year and ends in 2024, as data for all variables are not yet available for 2025. Table 5 outlines the variables, their measurements, and the data sources used in this study. Environmental sustainability (ES) is captured using the ratio of biocapacity to ecological footprint from [33], providing a holistic measure of ecological balance. Female participation in leadership (FP) is measured by the proportion of parliamentary seats held by women, sourced from [34]. Trade (TD) is represented by trade as a percentage of GDP, while financial development (FD) is proxied by domestic credit to the private sector by banks as a share of GDP, both obtained from [34]. Finally, economic growth (EG) is measured by GDP per capita in constant 2015 US dollars, also from [34], ensuring consistency and comparability across time.

Table 5.

Data sources and measurement.

3.2. Empirical Method

Adopting the QQARDL model proposed by [35], this paper moves beyond the confines of traditional ARDL and QARDL. ARDL only captures mean responses, and QARDL extends to the distribution of the dependent variable; QQARDL advances further by pairing the quantiles of regressors with those of the outcome, thereby exposing nonlinear and asymmetric interactions across the full joint distribution. To maintain coherence and comparability between short-run and long-run parameters, the specification employs an ARDL(1,1) structure following [36]. The workflow begins with [37]’s quantile series method to derive quantile-indexed representations of all variables, after which ARDL equations are estimated on these transformed series. This setup supports rigorous tests of long-run relations and yields dynamic coefficients for each quantile pairing, which are presented as a matrix that clearly maps cross-distribution dependencies:

Here, denotes the change in ; is a quantile-specific intercept. The coefficients of the short-run are depicted by ; the long-run coefficients are . The QQARDL bound test computes an F-statistic for each (τ, θ) pair to determine cointegration:

With cointegration confirmed, this study implements an error-correction form within the QQARDL architecture to recover both the transient and persistent components of the relationship between quantiles of and . The inclusion of an ECT anchors each quantile pairing to its long-run equilibrium, enabling the estimation of the speed of adjustment back to balance aftershocks. At the same time, quantile-specific differenced regressors identify short-horizon pass-through that may vary across low, median, and high states of the variables. This approach isolates equilibrium consistency from immediate adjustments, revealing how distributional states condition both the magnitude and direction of responses:

In the specification, ∂0(τ, θ) is the error-correction term, with δ1(τ, θ) and β1(τ, θ) reflecting short-run and long-run parameters. Long-run effects are computed only for cointegrated quantile pairs, whereas short-run effects are assessed for all combinations.

The initial values correspond to the distributional quantiles of X, whereas the subsequent values correspond to those of Y.

4. Findings and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlation Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations for the core variables are summarized in Table 6. Part A shows EG ranging from 7.55 to 9.50, averaging 8.63 with moderate volatility (Stdev = 0.606) and a mild negative skew, suggesting a tilt toward higher growth realizations. ES is persistently below zero (mean = −1.35), capturing sustained sustainability challenges; its positive skewness hints at intervals of relatively lower ecological pressure. Both FD and FP display tight distributions (Stdev = 0.203 and 0.085) and positive skewness, signaling more frequent higher-level outcomes for financial development and female leadership participation. TD records a mean of 3.76, moderate dispersion, and a positive skew, consistent with generally rising but uneven trade activity. Normality is decisively rejected for all variables by the Jarque–Bera statistic (p < 1%), motivating robust, non-Gaussian methods. In Part B, ES sits at the center of strong linkages: It is nearly perfectly inversely related to EG (−0.974) and also negatively correlated with FD (−0.769) and FP (−0.656), whereas its association with TD is small and positive (0.113). Taken together, these patterns suggest that while financial development and female participation support growth, they are accompanied by declines in environmental sustainability, underscoring the need for policy frameworks that integrate inclusiveness and finance with ecological goals.

Table 6.

Descriptive statistics and correlation results.

4.2. Diagnostic Test

The diagnostics in Table 7 test for structural complexity and distributional shape. Part A shows that Teräsvirta, White, and BDS statistics are all significant at the 1% threshold, documenting widespread nonlinearities among the variables. The Keenan test isolates ES as distinctly nonlinear (p < 1%), while EG, FD, FP, and TD do not exhibit the same pattern, suggesting that environmental sustainability embeds richer nonlinear components. Reinforcing this, Mann–Kendall and Runs tests are significant across all series at the 1% level, indicating non-randomness and serial structure. The combined signal justifies moving beyond linear, mean-centric specifications. Normality and variance diagnostics in Parts B and C point to additional modeling challenges. Robust Jarque–Bera and Shapiro–Wilk tests reject Gaussianity for every series; skewness and kurtosis results—especially for ES (skewness: p = 0.0026 ***; kurtosis: p < 1%)—confirm thick tails and shape deviations. Interestingly, the SJ statistics are not significant, suggesting approximate symmetry even in the presence of excess kurtosis. White and ARCH–LM tests unanimously detect heteroskedasticity (p < 1%), underscoring time-varying volatility. In combination, these properties—nonlinearity/dependence, non-normality, and heteroskedasticity—support employing nonlinear, distribution-aware, and robust estimators, with quantile-based frameworks particularly well-suited to the task.

Table 7.

Diagnostic test results.

4.3. Stationarity Test

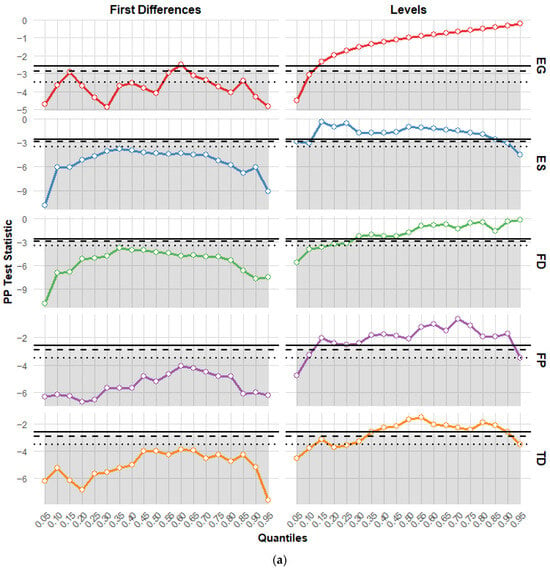

The quantile-based Phillips–Perron (PP) and Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test results in Figure 2a,b show that EG, ES, FD, FP, and TD are non-stationary in levels but become stationary after first differencing, confirming that all series are integrated of order one, I(1). Importantly, the quantile framework highlights heterogeneous persistence across the distribution: For instance, EG displays stronger unit root evidence in upper quantiles, while ES and FD remain consistently non-stationary across quantiles, and FP and TD show varying degrees of persistence. These results not only validate the application of cointegration techniques but also suggest that mean-based approaches may obscure distributional dynamics. Thus, employing nonlinear and quantile-based econometric methods such as the quantile ARDL (QARDL) is essential, as they allow both long-run and short-run relationships to be captured across different quantiles, thereby accommodating heterogeneity, asymmetry, and distributional dependence in the growth–sustainability–finance–inclusion–trade nexus.

Figure 2.

(a): Quantile PP estimates. Note: Shaded areas denote 1%, 5%, and 10% critical values. (b): quantile ADF estimates. Note: Shaded areas denote 1%, 5%, and 10% critical values.

4.4. Quantile-on-Quantile ARDL Result

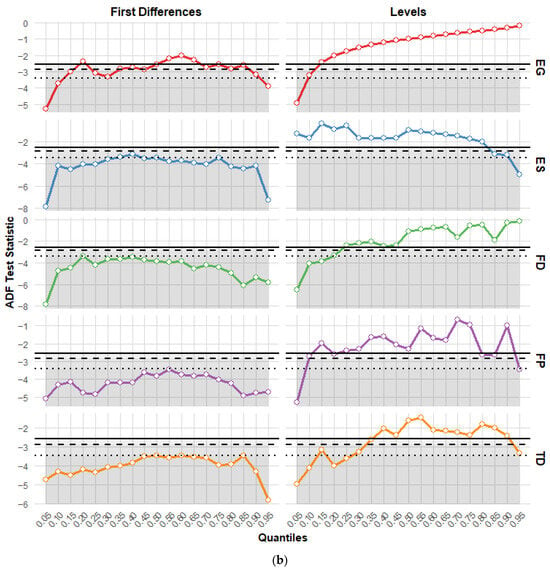

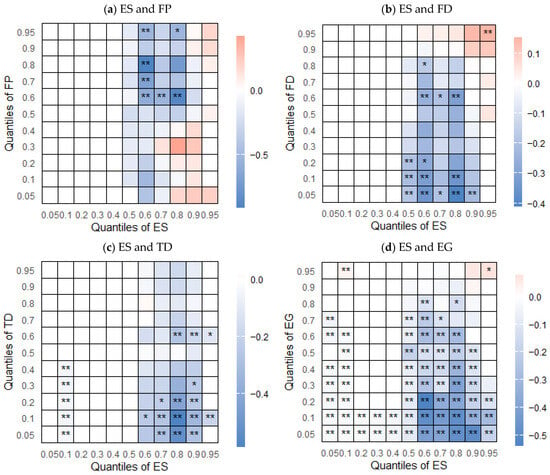

The QQARDL bounds test results in Figure 3 provide evidence of quantile-dependent cointegration between ES and the other variables—FP, FD, TD, and EG. The heatmaps show the test statistics across combinations of ES quantiles (x-axis) and the quantiles of each explanatory variable (y-axis), with the intensity of the shading and the presence of significance stars indicating where the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected. The results reveal that cointegration is not uniform but rather concentrated in specific quantile ranges, highlighting the asymmetric and heterogeneous nature of the long-run relationships. For instance, ES and FP demonstrate significant cointegration predominantly in the mid-to-upper quantiles, suggesting that stronger female participation interacts with higher levels of environmental sustainability in forming a long-run equilibrium. Similarly, ES and FD display robust cointegration across a wide range of quantiles, emphasizing the deep linkages between financial development and sustainability outcomes. The relationship between ES and TD shows cointegration, particularly in mid- and upper quantiles, indicating that trade openness contributes more strongly to long-run sustainability dynamics at higher conditional distributions of ES. The ES–EG nexus stands out with widespread and consistent cointegration across nearly all quantile combinations, underscoring the fundamental long-run trade-off and interdependence between economic growth and environmental sustainability. Overall, the QQARDL bounds test results confirm that the variables are cointegrated, but in a quantile-specific manner, meaning that the strength and presence of long-run relationships vary across different states of the economy and environment.

Figure 3.

QQARDL bound test. ** p < 5%, and * p < 10%.

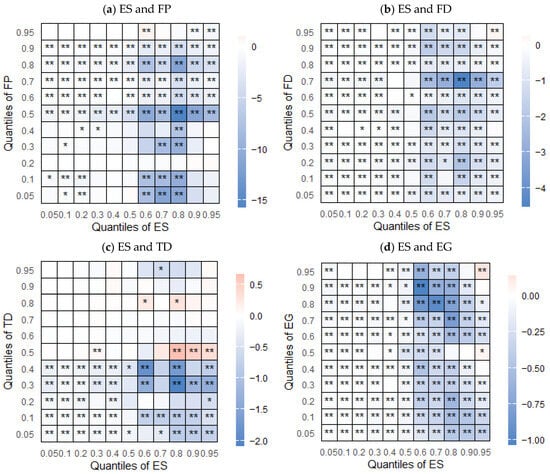

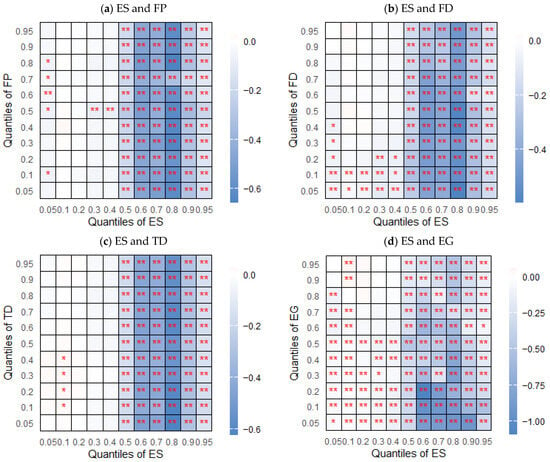

The QQARDL long-run results in Figure 4 provide quantile-specific insights into the relationship between environmental sustainability (ES) and its key determinants. Panel a shows that the ES–FP relationship is predominantly negative across mid-to-upper quantiles, with several cells around the 0.6–0.8 quantiles of ES and FP showing significant coefficients. This indicates that in China, when both environmental sustainability and female political participation are relatively high, greater participation does not translate into improved sustainability outcomes but instead coincides with deteriorations. A few positive but nonsignificant coefficients at the upper tail (0.9–0.95) suggest that only at very high quantiles might FP support ES, but the evidence is weak.

Figure 4.

QQARDL long-run results. ** p < 5%, and * p < 10%.

Panel b shows that ES and FD are also mostly negatively associated, with strong significance in the lower and mid-quantiles of ES and FD. For instance, at the 0.1–0.3 quantiles of ES and FD, coefficients are around −0.2 to −0.3, indicating a clear long-run trade-off. This suggests that in states of low to moderate sustainability, financial deepening in China has often come at an environmental cost, reflecting the country’s reliance on credit expansion and financial flows that historically favored industrial sectors. However, at the very upper quantiles (0.9–0.95), a weak positive effect emerges, hinting that advanced stages of financial development—likely linked to green finance reforms in recent years—may begin to align more positively with sustainability goals.

The ES–TD relationship in Panel c further illustrates China’s structural challenges. Significant negative coefficients dominate at low ES quantiles (0.05–0.25) across multiple trade quantiles, with magnitudes close to −0.4. This indicates that during periods of weak environmental performance, trade expansion exacerbates environmental degradation, consistent with the pollution haven hypothesis. However, at mid-to-high ES quantiles (0.5–0.8), the coefficients weaken, suggesting that once sustainability reaches moderate levels, the adverse effects of trade are somewhat less pronounced—potentially reflecting technology transfer or the adoption of cleaner production standards through trade integration.

Finally, Panel d highlights the ES–EG nexus, where negative long-run coefficients are consistently observed across nearly all quantile combinations, with magnitudes often around −0.3 to −0.5 and strong significance in the mid-to-upper quantiles. This finding confirms the environmental cost of China’s sustained economic growth, particularly when growth is high and ES is moderate to high. While this aligns with the classic Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) trade-off in the early and middle stages of development, it also contrasts with studies suggesting that China has already reached the turning point.

Figure 5 shows the short-run QQARDL. Panel a demonstrates that the ES–FP relationship is predominantly negative and statistically significant across most quantile combinations, particularly when both ES and FP are in their lower to middle quantiles. This implies that in the short run, increases in female political participation coincide with reductions in environmental sustainability. One interpretation is that in contexts where institutional mechanisms are not fully supportive, greater female representation may not immediately translate into improved sustainability outcomes but could instead be constrained by structural economic priorities. Nonetheless, the persistence of significance across quantiles underscores the importance of FP as a channel shaping ES, even if its short-run impact is adverse.

Figure 5.

QQARDL short-run results. ** p < 5%, and * p < 10%.

Panel b shows a strong negative short-run relationship between ES and FD, with statistically significant coefficients dominating across almost all quantile combinations. The magnitudes are concentrated around −1 to −4, suggesting that financial development exerts a substantial short-run pressure on environmental sustainability in China. This indicates that credit expansion and financial flows are still disproportionately directed towards environmentally intensive sectors such as manufacturing, real estate, and infrastructure development, which generate immediate environmental costs. Unlike the long-run findings, where some weak positive effects emerge at higher quantiles, the short-run results highlight that financial development remains a structural driver of environmental degradation in China, at least in the immediate term, before reforms in green finance can take effect.

Panel c depicts the ES–TD short-run association, where negative coefficients dominate the lower quantiles of both ES and TD, with magnitudes around −1.0 to −2.0, and significance concentrated at the 0.05–0.3 quantiles. This suggests that when environmental sustainability is weak, trade expansion exacerbates environmental degradation in the short run, consistent with the pollution haven hypothesis. However, at higher quantiles (0.7–0.9), some positive and significant coefficients emerge (reddish cells), indicating that under stronger environmental conditions, trade can potentially support ES, perhaps through cleaner production standards, environmental clauses in trade agreements, or technology spillovers. This duality underscores the conditional nature of trade’s effect: whether it reinforces or alleviates environmental pressure depends on the state of sustainability in the economy.

Finally, panel d shows that the ES–EG short-run association is almost uniformly negative, with coefficients ranging from −0.25 to −1.0 across most quantiles and strong significance throughout. This finding highlights that economic growth in China imposes immediate environmental costs across the entire distribution of ES, reinforcing the idea that growth in the short run remains resource- and pollution-intensive. Even at higher ES quantiles, growth continues to undermine sustainability, suggesting that the benefits of cleaner technologies or ecological reforms have not yet materialized strongly enough to offset the short-run environmental trade-offs of expansion. This contrasts with the long-run literature that expects eventual EKC turning points, suggesting that China’s short-run growth–environment trade-off remains structurally embedded, requiring stronger regulatory enforcement, faster clean energy adoption, and deeper institutional reforms to decouple growth from environmental degradation.

The QQARDL Error Correction Term (ECT) results in Figure 6 illustrate the adjustment dynamics of ES in response to deviations from long-run equilibrium across FP, FD, TD, and EG. Across all panels, the ECT coefficients are consistently negative and statistically significant at most quantile combinations, which confirms the stability of the long-run relationships and the existence of a quantile-specific cointegration process. In Panel a, the ES–FP relationship shows moderately negative and significant ECT values (around −0.2 to −0.6), suggesting that when ES deviates from its long-run equilibrium with FP, approximately 20–60% of the disequilibrium is corrected in the following period depending on the quantile level. Similarly, Panel b demonstrates that ES and FD also exhibit strong and significant adjustment, with particularly higher speeds of correction at the lower quantiles of ES, indicating that when sustainability is weak, deviations from equilibrium with financial development are corrected more rapidly.

Figure 6.

QQARDL ECT results. ** p < 5%, and * p < 10%.

Panel c highlights the ES–TD nexus, where the adjustment coefficients are strongly negative and significant across the mid-to-upper quantiles of ES and TD, with values up to −0.6. This suggests that trade-related shocks to sustainability are quickly absorbed, particularly when ES is already at moderate to high levels, reflecting the growing integration of trade with environmental mechanisms such as cleaner exports and international regulatory standards. Finally, Panel (d) reveals the ES–EG relationship, where ECT coefficients are the largest in magnitude (approaching −1.0 in some quantiles) and highly significant throughout. This indicates that deviations from the long-run equilibrium between growth and sustainability are corrected very rapidly, particularly at higher levels of ES and EG, highlighting the strong adjustment pressures in China’s growth–environment dynamics. Collectively, these results confirm that while shocks in the short run may generate environmental imbalances, the system consistently reverts to long-run equilibrium, with the speed of adjustment varying by quantile and by the specific interaction with FP, FD, TD, and EG.

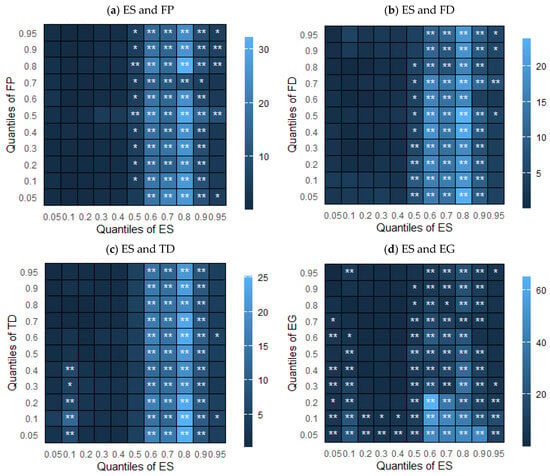

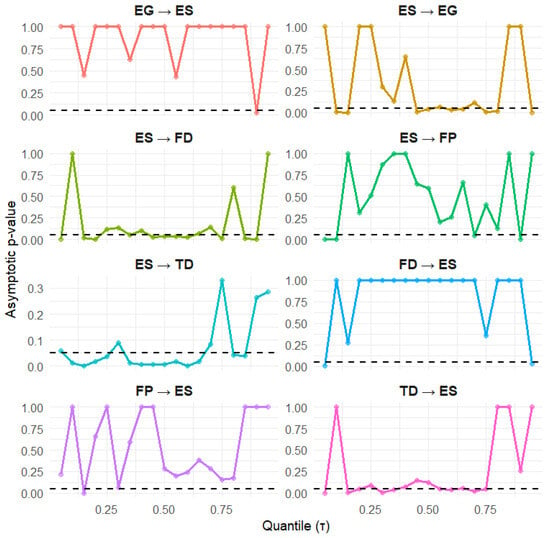

4.5. Quantile Granger Causality

Figure 7 presents the results of the Quantile Granger Causality between ES and its key. Beginning with EG and ES, bidirectional causality emerges, but with asymmetric patterns: EG causes ES primarily at selected lower and upper quantiles, while ES drives EG more consistently in mid-to-high quantiles. This suggests that environmental performance significantly constrains growth when sustainability is moderate or improving, while growth shocks only affect ES in periods of environmental extremes. For ES and FD, causality is largely unidirectional from ES to FD across several quantiles, implying that improvements in sustainability influence financial flows (likely via green finance initiatives), whereas the reverse channel remains weak in most quantiles.

Figure 7.

Quantile Granger Causality.

Turning to ES and FP, the causality is stronger from ES to FP, particularly in middle quantiles, indicating that improvements in environmental sustainability tend to foster conditions that promote female political inclusion or empower participation in governance. However, FP’s effect on ES is weaker and only sporadically significant, consistent with the notion that, in China, institutional structures still limit the immediate environmental impact of female participation in leadership. For ES and TD, causality is unidirectional from ES to TD across lower quantiles, suggesting that weaker sustainability conditions shape trade composition and flows, while trade’s influence on ES is less consistently observed. Finally, FD and TD both exhibit weak predictive power for ES across most quantiles, underscoring the dominance of environmental conditions themselves in shaping macro-financial and trade outcomes in the Chinese context.

4.6. Discussion of Findings

This section presents the discussion of the findings. We observed a predominantly negative association between female political leadership (FP) and environmental sustainability (ES). In the context of China, these findings align with some studies but contrast with others. For example, ref. [38] finds that China’s recent economic growth shows evidence of a gradual transition toward a more sustainable economic structure, but that growth still exerts environmental costs in certain sectors. Also, ref. [1] documents that Chinese policy has increasingly aimed to include women and local female participation in environmental governance (especially through “ecological civilization”) but acknowledges that structural constraints mean female participation does not always translate into stronger environmental outcomes unless supported by stronger institutions. On the other hand, some studies, such as [6], point out that, in higher-income contexts, female participation tends to have a more positive or at least less negative effect on environmental outcomes.

Likewise, the ES and FD association is predominantly negative. Turning less negative or weakly positive at very high ES/FD matches or echoes several recent studies. For example, ref. [39] finds heterogeneous effects of financial development on sustainability: In low-to-middle-income provinces or earlier stages, financial deepening can reinforce environmental pressures, but in provinces where green technology, regulatory oversight, and environmental standards are more advanced, finance plays a more constructive role. Also, ref. [40] shows that green finance (a component of financial development) has stronger positive effects in regions or quantiles with higher baseline “quality of institutions” and environmental regulation. On the other hand, there are studies that disagree or complicate this view. Some recent work argues that even in relatively advanced quantiles or provinces, the positive effects of financial development on ES are weak unless accompanied by strong environmental regulation, technology adoption, and policy reforms. For instance, ref. [41] reports that while green finance instruments (like green bonds and green loans) are expanding, their full environmental impact remains uneven due to issues like weak implementation, greenwashing, and disparity between provinces. Also, ref. [42] highlights that without regulatory oversight, financial development may fail to incentivize green innovation or sustainability improvements even when financial resources are abundant.

Regarding ES–TD the results highlight the structural challenges of trade for China’s environmental agenda. At the lower quantiles of environmental sustainability (0.05–0.25), the coefficients are significantly negative, with magnitudes approaching −0.4, suggesting that during periods of weak environmental performance, trade openness intensifies environmental degradation. This outcome is consistent with the pollution haven hypothesis, which posits that countries with relatively lax environmental standards attract polluting industries through trade liberalization. Ref. [43] provides supporting evidence, showing that trade openness in China after WTO accession led to substantial increases in emissions, primarily through scale effects in energy-intensive manufacturing sectors [44]. Similarly, ref. [45] demonstrates that exports from environmentally intensive industries continue to contribute disproportionately to regional environmental pressures, underscoring the risks of trade-driven environmental stress in China. However, we observed that at mid-to-high ES quantiles (0.5–0.8), the negative impact of trade on environmental sustainability diminishes, suggesting that once a certain threshold of sustainability is achieved, trade integration may begin to facilitate positive spillovers. This could reflect technology transfer, the diffusion of cleaner production processes, or stricter environmental requirements imposed on exporters. Ref. [46] confirms this channel, finding that foreign technology transfer through trade and investment has improved environmental efficiency in China’s high-tech industries. Ref. [47] further highlights that China’s expanding role in the global market for low-carbon technologies has dual benefits: it improves partner countries’ environmental performance and incentivizes domestic firms to adopt greener practices.

Lastly, the negative association between ES and EG across nearly all quantile combinations—and especially in the mid-to-upper quantiles (≈0.5–0.95)—suggests that, in China, periods of higher growth are associated with worsening environmental sustainability, even when sustainability is already moderate to strong. The magnitude of these coefficients (around −0.3 to −0.5) indicates a substantial trade-off: Growth imposes environmental costs that are not easily offset once the economy passes certain growth thresholds, unless accompanied by strong mitigation measures. This pattern is broadly consistent with the early and middle segments of the Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) theory, where growth initially increases pollution before eventual reductions occur [48]. However, this finding diverges from some of the recent literature that suggests China has already passed the turning point of the EKC for certain environmental indicators. For example, ref. [49] finds an inverted U-shaped relation between GDP per capita and carbon emissions; Their results suggest that many urban areas have begun to show declining emissions beyond certain income levels, consistent with having reached a turning point. Meanwhile, ref. [50] reports that while many studies validate the EKC in China, there remains significant heterogeneity: regional, sectoral, and pollution-proxy variations mean that the turning point is not uniform across the country.

5. Conclusions and Policy Initiatives

5.1. Conclusions

The promise of female participation in leadership (FP) for environmental sustainability depends on institutional strength, credible enforcement, and genuine channels for women to influence ecological choices. Using China’s quarterly data from 1998Q1 to 2024Q4, this study applies quantile-focused methods to accommodate nonlinearity and non-normality. QQARDL estimates indicate that GIL and financial development (FD) generally depress environmental sustainability (ES), though these adverse effects are mitigated where institutions are stronger and green finance is more developed. Trade openness (TO) is harmful at the lower end of the ES distribution but becomes conducive to cleaner outcomes as sustainability improves. Economic growth (EG) consistently undermines ES, consistent with an early Environmental Kuznets Curve (EKC) phase, with turning points varying across regions.

5.2. Policy Initiatives

China’s path to real environmental gains requires moving beyond symbolic inclusion. The largely negative link between female political participation and sustainability suggests that representation without decision power, resources, and mandates delivers limited impact. A stronger approach empowers women within environmental institutions through targeted capacity building, durable organizational backing, and gender-sensitive program design. Creating formal channels for female leaders to shape climate strategy can translate participation into measurable ecological benefits.

The negative association between financial development and sustainability signals misallocated capital rather than an unavoidable trade-off. Redirecting finance toward renewables, circularity, and clean technologies should be matched with tighter supervision to curb greenwashing. Regulators can embed alignment by incorporating environmental risk metrics in credit decisions, lifting disclosure standards, and rewarding verifiable green innovations. Expanding green-finance access in lagging provinces would support a fairer, more balanced transition.

Trade liberalization can amplify environmental risks where safeguards are weak. Policy should raise exporter benchmarks, weave ecological provisions into trade agreements, and expand access to clean manufacturing technologies. Since trade-related harms ease at higher sustainability levels, upgrading to cleaner production and integrating with global low-carbon technology networks can convert trade into a conduit for diffusion and greener outcomes, anchored by a push to grow green export sectors.

The persistent tension between growth and sustainability underscores the urgency of faster decoupling. Environmental pressures continue to rise with output, especially at higher growth states, implying that the dividends from transition are uneven. Policy should accelerate structural shifts that scale renewables, reduce coal dependence, and embed carbon-neutral targets in industrial strategy. Region-specific roadmaps matched to local development and ecological constraints are vital, supported by an innovation-led growth model that aligns prosperity with environmental quality.

5.3. Managerial Initiatives

To build a durable competitive advantage, Chinese managers should reframe sustainability as an enterprise-wide capability that shapes strategic direction and execution, rather than treating it as a box-ticking response to regulation. This involves systematically integrating female participation in leadership into every stage of the sustainability process: identifying material issues, defining objectives, designing interventions, and delivering on implementation. Firms can empower women to jointly lead environmental roadmaps, invest in leadership development focused on eco-innovation and process refinement, and adjust governance so that boards and key committees explicitly connect inclusion mandates with sustainability responsibilities. The result is richer strategic insight and faster progress in cutting energy intensity, scaling renewable energy use, and modernizing production toward cleaner technologies.

Financial and trade decisions should underpin this transformation. Capital budgeting needs to prioritize low-carbon, circular-economy, and resilient supply chain projects, while environmental indicators become part of ongoing portfolio and performance reviews, supported by climate-related scenario testing. On the trade side, firms should elevate product and process standards to meet or exceed regulations in major destination markets, enhance supply chain transparency, and collaborate with global green hubs and industry networks. These actions collectively help firms manage regulatory and reputational risk, tap into expanding green demand, and contribute to China’s ecological transition without sacrificing commercial strength.

5.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Several caveats qualify the conclusions and point to directions for future work. First, using the Load Capacity Factor as our proxy for environmental sustainability is a strength in terms of providing a holistic, capacity-based measure, but it also aggregates multiple ecological pressures into a single index. This aggregation can dilute specific trade-offs: For example, when trade openness increases methane emissions from agriculture while simultaneously affecting CO2 from industry or other localized pollutants, future research could complement LCF with pollutant-specific or sector-specific indicators to uncover these channels more explicitly. Second, quantile-based methods are well suited for revealing heterogeneous effects but may be exposed to data sparsity at extreme quantiles; supplementing them with panel threshold or smooth transition models, causal forest estimators, or double-ML frameworks would offer useful robustness checks. Third, concentrating on China enhances contextual relevance but limits the breadth of inference, so comparative analyses across multiple emerging markets would help show how differences in governance capacity, financial depth, and trade structures condition environmental performance. Finally, the analysis is conducted at an aggregate scale, and introducing sectoral or regional granularity would make it possible to test whether female participation in leadership, financial development, and trade openness operate differently in high-carbon versus low-carbon activities, informing more fine-grained policy design.

Author Contributions

Data curation, A.K.; Writing—original draft, H.E.; Writing—review & editing, H.E.; Supervision, A.K.; Project administration, H.E. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chen, L.; Hansen, M.H. Gender and Power in China’s Environmental Turn: A Case Study of Three Women-Led Initiatives. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, T.; Tawiah, V.; Zakari, A.; Osei-Tutu, F. Female parliamentarians and environmental sustainability: Do national culture matter? Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2025, 217, 124174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, M.; Hye, Q.M.A.; Tiwari, A.K.; Leitão, N.C. Economic growth, energy consumption, financial development, international trade and CO2 emissions in Indonesia. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 25, 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, C.; Ma, X. The Impact of Financial Development on Carbon Emissions: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omri, A.; Daly, S.; Rault, C.; Chaibi, A. Financial development, environmental quality, trade and economic growth: What causes what in MENA countries. Energy Econ. 2015, 48, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Z.; Jiang, F.; Xu, T. Female parliamentarians and environment nexus: The neglected role of governance quality. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 184, 122022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierli, G.; Murmura, F.; Palazzi, F. Women and Leadership: How Do Women Leaders Contribute to Companies’ Sustainable Choices? Front. Sustain. 2022, 3, 930116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cisternas, F.; Sun, C.; Contador, C.A.; Anders, S.; Chu, M.; Phan, N.; Hu, B.; Liu, Z.; Lam, H.-M.; Tse, L.A. Cultural and generational factors shape Asians’ sustainable food choices: Insights from choice experiments and information nudges. Cell Rep. Sustain. 2024, 1, 100020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhabra, M.; Giri, A.K.; Kumar, A. Do technological innovations and trade openness reduce CO2 emissions? Evidence from selected middle-income countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 65723–65738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erdogan, S.; Akalin, G. Empirical Evidence on the Impact of Technological Innovation and Human Capital on Improving and Enhancing Environmental Sustainability. Sustainability 2025, 17, 7840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahya, H. Female leadership and ESG performance of firms: Nordic evidence. Corp. Gov. 2023, 25, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Krueger, A.B. Economic Growth and the Environment. Q. J. Econ. 1995, 110, 353–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansour, M.; Al Zobi, M.; Altawalbeh, M.; Abu Alim, S.; Lutfi, A.; Marashdeh, Z.; Al-Nohood, S.; Al Barrak, T. Female leadership and environmental innovation: Do gender boards make a difference? Discov. Sustain. 2024, 5, 331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pathiranage, N.W.; Waheduzzaman, W.; Dayarathna, K.T. Top management gender diversity and environmental performance: Evidence from hospitality and tourism industry. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2025, 130, 104262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmania, T.; Kertamuda, F.; Wulandari, S.S.; Marfu, A. Empowering women for a sustainable future: Integrating gender equality and environmental stewardship. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2025, 11, 101503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagnani, M.; Mahadevan, M. Women leaders improve environmental outcomes: Evidence from crop fires in India. J. Public Econ. 2025, 248, 105443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalil, A.; Feridun, M. The impact of growth, energy and financial development on the environment in China: A cointegration analysis. Energy Econ. 2011, 33, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamazian, A.; Rao, B.B. Do economic, financial and institutional developments matter for environmental degradation? Evidence from transitional economies. Energy Econ. 2010, 32, 137–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozturk, I.; Acaravci, A. The long-run and causal analysis of energy, growth, openness and financial development on carbon emissions in Turkey. Energy Econ. 2013, 36, 262–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dogan, E.; Turkekul, B. CO2 emissions, real output, energy consumption, trade, urbanization and financial development: Testing the EKC hypothesis for the USA. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 1203–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixeira, N.; Rodrigues, R.; Rodrigues, A. Economic growth and environmental sustainability in more and less sustainable countries. Discov. Sustain. 2025, 6, 618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, C.; Li, H.; Li, Z. Environmental pollution and economic growth: Evidence of SO2 emissions and GDP in China. Front. Public Health 2022, 10, 930780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horodecka, A. Is Economic Development Really Becoming Sustainable? Forum Soc. Econ. 2024, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirikkaleli, D.; Sowah, J.K.; Addai, K. The asymmetric and long-run effect of energy productivity on environmental degradation in the United Kingdom. Energy Environ. 2023, 35, 2566–2585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, U.D.; Adegbola, O.C.; Shittu, I.M.; Falana, B.J.; Obidiah, F.E. Economic Growth and Environmental Sustainability: Empirical Evidence from Selected African Countries. Path Sci. 2024, 10, 7001–7013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, F.; Jiang, G.; Kitila, G.M. Trade Openness and CO2 Emissions: The Heterogeneous and Mediating Effects for the Belt and Road Countries. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, D.T.T.; Nguyen, H.T. Effects of trade openness on environmental quality: Evidence from developing countries. J. Appl. Econ. 2024, 27, 2339610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djellouli, N.; Abdelli, L.; Elheddad, M.; Ahmed, R.; Mahmood, H. The effects of non-renewable energy, renewable energy, economic growth, and foreign direct investment on the sustainability of African countries. Renew. Energy 2022, 183, 676–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qamruzzaman, M. Clarifying the nexus between Trade Policy Uncertainty, Economic Policy Uncertainty, FDI and Renewable Energy Demand. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2024, 14, 367–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakri, M.A.; Chia, Y.-E.; Chia, R.C.-J. Trade openness and carbon emissions using threshold approach: Evidence from selected Asian countries. Carbon Res. 2025, 4, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Clottey, S.A.; Geng, Y.; Fang, K.; Amissah, J.C.K. Trade Openness and Carbon Emissions: Evidence from Belt and Road Countries. Sustainability 2019, 11, 2682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thi, D.; Tran, V.Q.; Nguyen, D.T. The relationship between renewable energy consumption, international tourism, trade openness, innovation and carbon dioxide emissions: International evidence. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2023, 42, 397–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Footprint Network. Ecological Footprint per Person. Available online: https://data.footprintnetwork.org/#/countryTrends?cn=110&type=BCpc,EFCpc (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- WDI. World Development Indicator. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 1 April 2024).

- Destek, M.A.; Radulescu, M.; Özkan, O.; Balsalobre-Lorente, D. The hidden cost of renewable energy: A quantile view for environmental management on critical metals. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 389, 126089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, S.; Philips, A.Q. Cointegration Testing and Dynamic Simulations of Autoregressive Distributed Lag Models. Stata J. 2018, 18, 902–923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.-H. Quantile Fourier transform, quantile series, and nonparametric estimation of quantile spectra. Commun. Stat. Simul. Comput. 2025, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, Y.; Rosland, A.; Ishak, S.; Senan, M.K.A.M. China’s pattern of growth moving to sustainability and reducing inequality. Econ. Res. Ekon. Istraživanja 2023, 36, 2101018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammed, K.S.; Magdalena, R.; Alofaysan, H.; Hagiu, A. The Impact of Green and Energy Investments on Environmental Sustainability in China: A Technological and Financial Development Perspectives. Environ. Model. Assess. 2025, 30, 1147–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Ding, Z. Sustainable growth unveiled: Exploring the nexus of green finance and high-quality economic development in China. Front. Environ. Sci. 2024, 12, 1414365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Eweade, B.S.; Özkan, O.; Ozsahin, D.U. Effects of energy security and financial development on load capacity factor in the USA: A wavelet kernel-based regularized least squares approach. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2025, 27, 4215–4232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirikkaleli, D.; Adebayo, T.S. Do renewable energy consumption and financial development matter for environmental sustainability? New global evidence. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 29, 583–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jun, W.; Mahmood, H.; Zakaria, M. Impact of trade openness on environment in China. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2020, 21, 1185–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebayo, T.S.; Akadiri, S.S.; Akpan, U.; Aladenika, B. Asymmetric effect of financial globalization on carbon emissions in G7 countries: Fresh insight from quantile-on-quantile regression. Energy Environ. 2022, 34, 1285–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Khan, K.A.; Eweade, B.S.; Adebayo, T.S. Role of eco-innovation and financial globalization on ecological quality in China: A wavelet analysis. Energy Environ. 2024, 36, 3770–3793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhong, Z. CO2 emissions, economic growth, renewable and non-renewable energy production and foreign trade in China. Renew. Energy 2019, 131, 208–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kongkuah, M.; Yao, H.; Yilanci, V. The relationship between energy consumption, economic growth, and CO2 emissions in China: The role of urbanisation and international trade. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2022, 24, 4684–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olanrewaju, V.O. Environmental effects of nuclear energy, renewable energy and trade openness in the United States: A wavelet perspective. Environ. Prog. Sustain. Energy 2026, e70152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanger, A.; Zaman, U.; Hossain, M.R.; Awan, A. Articulating CO2 emissions limiting roles of nuclear energy and ICT under the EKC hypothesis: An application of non-parametric MMQR approach. Geosci. Front. 2023, 14, 101589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Dogan, M.; Pervaiz, A.; Bukhari, A.A.A.; Akkus, H.T.; Dogan, H. The impact of digitalization, technological and financial innovation on environmental quality in OECD countries: Investigation of N-shaped EKC hypothesis. Technol. Soc. 2024, 77, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.