Abstract

Heavy metals release in the environment represents a growing threat to human health and nature, particularly due to industrial activities contributing to soil and water contamination. In this study, Ganoderma lucidum heteropolysaccharides (GLHP) were evaluated as a biosorbent for cadmium removal. The biomass was acquired following the production of Ganoderma lucidum fruiting bodies and consisted of remnants from the fungus and cultivation substrate. Cd(II) and elemental analysis were carried out by atomic adsorption spectrometry (AAS) and inductively coupled plasma mass spectroscopy (ICP-MS), respectively. The biosorption efficiency was critically evaluated, optimizing physical adsorption parameters for batch, column, and percolation configuration, as well as application in real environmental water. Utilizing a simple pre-rinsing step, completely omitting any chemical pretreatment, the Cd(II) removal efficiency was improved from 41.2% to 78.4% in a batch system and up to 98.4% in a fixed-bed column, making it suitable not only for wastewater treatment but also for drinking water purification. The adsorption kinetics were described by a pseudo-second-order (PSO) model and further analyzed using a revised PSO (rPSO) model, which explicitly accounts for adsorbate and adsorbent concentrations. A global fit to the PSO model demonstrated that the rate constant was independent of the adsorbent concentration, supporting its application as a robust descriptor of the adsorption process. GLHP showed good adsorption performance, following the Sips adsorption isotherm and Thomas model for batch and column setup, respectively, demonstrating the potential as a scalable, low-cost biosorbent for fast and efficient Cd(II) removal from contaminated waters.

1. Introduction

Heavy metals are naturally present in the earth’s crust but are also released into the environment as a result of rapid industrialization, which has spurred the expansion of activities such as electroplating, tanning, and chemical manufacturing, leading to the persistent increase in metal concentrations and severe pollution problems arising from the improper disposal and management of industrial waste [1]. The levels of heavy metals in the environment have been rising continuously and, due to high toxicity, pose a significant threat to living organisms of aquatic and soil ecosystems already at low concentrations [2].

Heavy metal ions are commonly removed from the environment through processes such as chemical precipitation, ion exchange, solvent extraction, and reverse osmosis [3]. Nonetheless, these methods exhibit several drawbacks, including non-selective metal ion removal, high-costs, complex processes, and low removal efficiency [4,5]. Activated carbon adsorption is a well-established technique for the removal of heavy metals from wastewater [6]. However, the substantial cost associated with activated carbon restricts its widespread application [7]. Some synthesized sorbents, such as the metal–organic framework (MOF), exhibit high sorption capacities; however, their practical application is often limited by structural stability in aqueous solutions and varying pH conditions, high prices of organic ligands, toxicity, and challenges with yields in large-scale synthesis [8]. As a significantly more cost-effective alternative, biosorption has emerged as a promising biotechnological approach, leveraging its simplicity, resemblance to traditional ion exchange processes, high efficacy, and availability of diverse types of biomasses and waste bioproduct feedstocks [9]. Among natural materials, fungal biomass is considered to be one of the most promising biosorbents [10,11,12]. The fungal cell wall is composed primarily of chitins, glucans, mannans, and proteins but also incorporates other polysaccharides and lipids. Due to the diversity of structural components, fungal biomass offers a wide range of functional groups with binding potential and strong interactions with metal ions [5,13]. Biosorption efficiency can be further improved via various activation methods, including the physical (e.g., heat, lyophilization, ultrasound, and microwave) [14] and/or chemical pretreatment (strong electrolytes, oxidative, acidic, alkaline, or organic solutions) [15,16,17] of fungal biomass.

Cadmium (Cd) is a highly toxic and mobile element with significant environmental and health implications [18]. A maximum contamination level of 5 μg L−1 has been established by the World Health Organization (WHO) for cadmium in drinking water [19]. Exposure to high levels of cadmium can lead to serious health problems, including kidney and liver damage, as well as an increased risk of cancer [20]. Sources of cadmium include natural geological processes (weathering of Cd-bearing rocks), atmospheric deposition (dust storms, sea spray, and volcanic eruptions), and anthropogenic processes, such as combustion of fossil fuels, waste disposal (sewage sludge, landfills), and industrial activities (mining, smelting) [21].

In this context, the aim of this study was to assess the biosorption potential of Ganoderma lucidum biomass for the removal of heavy metals from the aquatic environment. The tested sorbent was a commercial dietary supplement based on Ganoderma lucidum heteropolysaccharides, which consists of fruiting bodies, associated secondary metabolites, and whole-grain starch, hereafter referred to as GLHP. The structural properties of biomass were characterized by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), showing a heterogeneous surface with a rough texture, as well as the particle size distribution, while the GLHP nutritional values were analyzed in terms of caloric value, dry matter, crude proteins, lipids and fiber, ash, and polysaccharides. As a distinguished traditional medicinal herb, Ganoderma lucidum heteropolysaccharides exhibit many health benefits, including immunomodulatory, anticancer [22], antioxidant [23], and protective effects against Alzheimer’s disease [24], alongside other pharmacological effects of bioactive polysaccharides from G. Lucidum, as reviewed by Lu et al. [25].

Cd(II) ion was used as a model contaminant in this study due to high toxicity, a wide range of application in batteries and industrial processes [26], and its local environmental relevance due to increased levels in Mežiška Valley, Slovenia [27,28]. Various physical pretreatment methods were systematically evaluated to improve the GLHP’s adsorption efficiency, and applied for Cd(II) ions removal from aqueous solutions, including a real sample of surface water. As a continuous biosorption using a column system offers a more practical and efficient approach for large-scale remediation applications [5], both batch and continuous adsorption systems were tested and compared for the bioremediation of Cd(II). Furthermore, for improved understanding of the GLHP adsorption mechanism, kinetics and mechanisms of both investigated systems were critically evaluated considering various types of adsorption models and isotherms. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study utilizing the commercially available GLHP product for Cd(II) removal, including a systematic evaluation of adsorption parameters, as well as additional improvement of the biosorbent performance by the use of a non-toxic pre-rinsing step in order to obtain higher sorption capacity and consequently lower residual Cd(II) concentrations for both wastewater as well as drinking water purification.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

The chemicals used in this study were supplied by Merck (Germany) with a purity of ≥99.99%. Stock solution of 93.05 mg L−1 Cd(II) was prepared by dissolving cadmium chloride monohydrate (CdCl2·H2O) in ultrapure Milli-Q (MQ) water with resistivity > 18.2 MΩ cm. Solutions of lower concentrations were prepared by serial dilution steps using MQ water to obtain the desired concentrations.

2.2. Structural and Nutritional Characterization of GLHP

GLHP, a commercial food supplement GOBA Galimmun®, sold as bulk material under the trademark GOBA® Ganoderma lucidum heteropolysaccharides, was donated by MycoMedica Ltd. (Podkoren, Slovenia). Material composed of G. lucidum fruiting bodies, secondary metabolites, and whole grain starch was dried under vacuum, milled into a fine powder, and used in experiments.

For structural characterization, the GLHP sample was coated with a thin layer of gold using a Jeol JFC 1100E ion sputtering machine (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and the microstructure was examined using the Jeol JSM-IT800 field emission scanning electron microscope (JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). The particle size distribution analysis was performed using a sowing power of 3.0 mm g−1, interval time of 40 s, and 2 min of total sowing time. The results are given in the Supplementary Materials (Figure S5 and Table S5, respectively).

For the nutritional composition analysis, relative amounts of protein (AOAC Official method 954.01), lipids (AOAC Official method 920.39), water (AOAC Official Method 934.01), fiber (AOAC Official method 978.10), and ash (AOAC Official method 942.05) in GLHP were estimated by proximate analysis. The analyses were conducted at the Biotechnical Faculty, Chair of Nutrition, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia. Polysaccharides content in samples was calculated by difference (100–water–lipids–proteins–ash) [29]. Since these results were not an object of the study, they are presented in the Supplementary Materials (Table S6).

2.3. Pretreatment of GLHP

For the evaluation of various thermal pretreatment methods, drying, vacuum drying and freeze-drying were applied. A total of 150 mL of ultrapure water was added to 100 g of GLHP, homogenized by stirring for 10 min, and the resulting suspension was divided into 4 equal parts. Parts 1 and 2 were dried for three hours at 90 °C and 120 °C, respectively; part 3 was freeze-dried overnight; and part 4 was dried and vacuumed at 90 °C for two hours, followed by freeze-drying overnight. After pretreatment, all fungal biomass parts were stored in a desiccator for 24 h and finely ground using a laboratory-grade grinder. The prepared biomass parts as well as the untreated biomass were later used for the adsorption studies to evaluate the effect of pretreatment methods.

In addition to thermal pretreatment, pre-rinsing of dried and finely ground fungal biomaterial was evaluated as well for adsorption studies. A size fractionation process was employed using a column of stacked copper sieves with varying pore sizes (42 µm, 56 µm, 71 µm, 100 µm, 200 µm, 250 µm, and 500 µm). Approximately 100 g of ground GLHP was rinsed with 20 L of Milli-Q water until a clear effluent was obtained. The size-fractionated GLHP was dried in a drying oven (Binder, Germany) at 110 °C with ventilation for 1.5 h, cooled to room temperature, and stored in a desiccator for 24 h.

2.4. Batch Adsorption Study

All experiments were performed at room temperature (22 ± 1) °C in a 250 mL beaker placed on a magnetic stirrer at 500 rpm, except for the study of the stirring speed, which was carried out in an Erlenmeyer flask at stirring rates between 100 and 1500 rpm. Batch Cd(II) removal efficiency was studied in 100 mL suspension with the initial metal concentration of 1.0 mg L−1 and addition of both untreated and pre-rinsed GLHP materials in the range of 0.1 g to 3.0 g. Sampling was performed at 2, 4, and 6 min.

For the study of particle size effect on the Cd(II) removal efficiency, 1.0 g of each size fraction (namely: <56 µm, 56 < 71 µm, 71 < 100 µm, 100 < 200 µm, 200 < 250 µm, 250 < 500 µm, and >500 µm) of untreated and pre-treated GLHPs was applied for the batch adsorption experiments in 100 mL of mQ water with added 1.0 mgL−1 Cd(II) at 500 rpm.

The batch adsorption of Cd(II) was also performed in the absence and presence of competing heavy metals (Pb(II), Co(II), Cr(III), Zn(II), Ni(II), and Mn(II)) using 1.0 g of untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs in 100 mL mQ with 1.0 mg L−1 Cd(II) at 500 rpm and 6 min contact time. The initial concentration of each heavy metal in the mix was 1.0 mg L−1. The results of these experiments are given in Supplementary Materials (Table S8).

To investigate the subsequent (i.e., multistep) adsorption efficiency, 1.0 g of GLHP was added to the initial 100 mL of 1.0 mg L−1 Cd(II) solution in the first step. After each adsorption step, the solution was filtered (0.45 µm), and fresh GLHP material was added into remaining filtrate solution. As the remaining filtrate volume decreased in every step due to water absorption and resulting fungal biomass swelling, the mass of added GLHP was adjusted (i.e., 0.8 g, 0.6 g, 0.4 g, 0.2 g, and 0.1 g for 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th step, respectively) in order to keep a constant mass-to-volume ratio (1.0 g GLHP/100mL) for all adsorption steps.

In addition, different GLHP masses were exposed to a surface water matrix sourced from the Glinščica river stream (Ljubljana, Slovenia; 46.051131, 14.467769) spiked with 1.0 mg L−1 of Cd(II). For the adsorption kinetics study, contact time was 30 min, and samples were collected every 15 s up to 2 min and thereafter every 3–6 min. Experiments without the addition of GLHP were used as negative controls. All experiments were performed in duplicate, and results are reported as mean ± standard deviation unless stated otherwise.

2.5. Fixed-Bed Column Adsorption Study

Continuous flow sorption experiments were conducted in a glass column with diameter of 1 cm and height of 15 cm. The column was packed with a 0.5 cm layer of glass wool followed by a predetermined amount of untreated GLHP biomass (namely: 0.1 g, 0.2 g, and 0.4 g) or 0.2 g in the case of pre-rinsed GLHP. Milli-Q water was first passed through the adsorbent bed to remove impurities and trapped air. Cd(II) solution of 1 mg L−1 was continuously fed into the top of the column at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min−1 at room temperature. Samples were collected every 8 min (i.e., by 8 mL intervals) from the column effluent and analyzed by AAS for residual Cd(II) concentration. The residual Cd(II) levels were used for the calculation of GLHP adsorption efficiency relative to the initial Cd(II) concentration. All experiments were performed in duplicate.

2.6. Percolation Adsorption Study

The percolation experiments were carried out in a flow-through column with diameter of 3.4 cm and height of 32 cm filled with 10 g of GLHP sorbent (resulting height of 4 cm) using Cd(II) solution (investigated concentrations: 1 mg L−1, 20 mg L−1, and 200 mg L−1), which was continuously fed into the top of the column at a flow rate of 1 mL min−1, maintained by a peristaltic pump. Both untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs were evaluated. Eluent samples were taken by 10 mL intervals, followed by filtration with 0.45 µm nylon filter and dilution with Milli-Q water before AAS analysis of residual Cd(II) concentration.

2.7. Determination of Cd by AAS

The remaining Cd(II) concentrations after adsorption were determined using flame atomic absorption spectrometry (FAAS, Varian AA240, Australia) by measuring the absorbance at 228.8 nm in the concentration range 0.08–0.6 mg L−1 (5 calibration standards, R2 > 0.999) after filtration with a 0.45 µm nylon filter (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and a 2-fold dilution with Milli-Q water.

2.8. Determination of Heavy Metals in GLHP by ICP-MS

Elemental analysis of initial GLHP was performed after acidic mineralization of fungal biomass in a microwave system Ethos Up (Milestone Srl, Sorisole, Italy). Approximately 250 mg of GLHP sample was weighed directly into a Teflon vessel, and 10.0 mL of 65% (w/w) HNO3 was added before applying the temperature program. The sample underwent a preliminary annealing step at 220 °C for 40 min in an open furnace, followed by a 20 min annealing treatment at 220 °C in a sealed furnace. After cooling to <60 °C (approx. 40 min), the sample was quantitatively transferred into a 25 mL flask and diluted with Milli-Q water. An additional 5-fold and 100-fold dilution using 1% (v/v) HNO3 was performed before the measurement. The analysis was performed using a quadrupole inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS Agilent 7900ce, Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA, USA) with the use of internal standard. A forward RF power of 1.5 kW was used with Ar gas flows, carrier 0.85 L min−1, makeup 0.28 L min−1, plasma 1.0 L min−1, cooling 15 L min−1, and sample flow rate 0.2 mL min−1, measuring one point per mass and acquiring the following isotopes: 7Li, 9Be, 11B, 23Na, 24Mg, 27Al, 31P, 39K, 44Ca, 47Ti, 51V, 52Cr, 55Mn, 56Fe, 59Co, 60Ni, 63Cu, 66Zn, 69Ga, 75As, 78Se, 85Rb, 88Sr, 95Mo, 107Ag, 111Cd, 115In, 118Sn, 121Sb, 125Te, 133Cs, 137Ba, 205Tl, 208Pb, and 209Bi. The calibration curves were based on 9 calibration multi-standards within the concentration range 0.1–1000 µg L−1 (R2 > 0.999), prepared by the dilution of CRM multi-standard solution (Periodic Table mix 1 for ICP, TraceCERT®, Sigma-Aldrich, Darmstadt, Germany). The limits of detection (LODs) were in the range 0.05–0.5 µg L−1, depending on the measured element.

2.9. Adsorption Data Study

The Cd(II) ions removal efficiency was calculated as follows:

where is the initial concentration of Cd(II) ion in the solution (mg L−1), and is the concentration of the metal ion at the equilibrium (mg L−1).

2.10. Adsorption Kinetics

Adsorption kinetics models provide information for understanding the mechanism that controls the overall adsorption process [30]. Two simple, empirical, and frequently applied kinetic models are the pseudo-first-order (PFO) and pseudo-second-order (PSO) models. The PFO kinetic equation [31] is given as

where (mg g−1) represents the amount of adsorbate (i.e., Cd(II)) adsorbed per mass of adsorbent (i.e., GLHP biomass) at time t (min), (mg g−1) is the amount of adsorbate adsorbed at equilibrium, and (min−1) is the PFO rate constant. The PSO kinetic equation [32] is given as

where (g mg−1 min−1) is the PSO rate constant. The integrated form of Equation (2) reads

While the integrated form of Equation (3) is given as

The values of rate constants and can depend on the underlying experimental conditions, i.e., on the initial concentrations of the adsorbate, , and adsorbent, [33,34]. The limitation of PFO and PSO models is that they cannot predict how changes in and will affect the adsorption kinetics. Recently, a revised pseudo-second-order (rPSO) kinetic model has been proposed [34], where both and are built into the kinetic equation:

where (mg L−1) is the concentration of the adsorbate at time t, and (L g−1 min−1) is the rPSO rate constant. Equation (6) can be integrated; however, this yields a transcendental equation that is not suitable for numerical fitting of experimental data (see Supplementary Materials).

We applied the PFO, PSO, and rPSO kinetic models to our experimental data. Frequently applied linearizations of kinetic equations are known to lead to erroneous estimations of the kinetic parameters [35,36,37]. A non-linear least-squares regression analysis (Levenberg–Marquardt algorithm) was therefore applied in all cases using GNU Octave (v. 4.2.2) software [38]. The uncertainties in fitting coefficients were estimated from the variance–covariance matrix. Details on numerical solutions of differential Equation (6) are given in the Supplementary Materials.

2.11. Adsorption Isotherms

Adsorption isotherm models can provide insight into the adsorption mechanism, surface characteristics, as well as the degree of affinity of the adsorbents [39]. Two most commonly applied adsorption isotherms are the Freundlich isotherm [40] and the Langmuir isotherm [41]. An empirical Freundlich isotherm takes the form:

where (mg L−1) is the concentration of adsorbent at equilibrium, (g−1 mg(1−1/n) L1/n) is the Freundlich constant, and unitless coefficient () is a parameter often used in evaluating the adsorption heterogeneity (higher values of correspond to more surface heterogeneity). However, we note that both and are empirical parameters obtained from fitting the Freundlich isotherm to experimental data. Therefore, care has to be taken when interpreting the values of these parameters for adsorption from a liquid phase on the microscopic level. In cases where , this can be an indication of cooperativity in interactions between adsorbent and adsorbate [42]. A model-based Langmuir isotherm takes the form:

where (mg g−1) represents the saturation amount of the adsorbate per unit mass of the adsorbent (i.e., maximum adsorption capacity), and (L mg−1) is the Langmuir equilibrium constant. For heterogeneous surfaces, the assumption that adsorption energy is constant and coverage-independent is often unrealistic. In addition, describing the adsorption from the liquid phase with Equation (8) has been shown to give poor correlation coefficients [43]. Several modified isotherms have been proposed to account for surface heterogeneity [44]. In this work, a so-called Sips (also known as Langmuir–Freundlich) isotherm was employed [44,45]:

where (L mg−1) is the Sips constant. For , Equation (9) converts to Equation (8). As with the Hill equation, which describes the binding of ligands to a biological macromolecule as a function of ligand concentration—where a certain amount of ligand bound to the macromolecule can enhance the binding of additional ligands from the solution (so-called cooperative binding)—Equation (9), in the case where , can be regarded as describing a cooperative-type reaction between an adsorption site and adsorbing molecules, with being the equilibrium constant for this process [42].

For describing column adsorption performance, the Thomas model [46] is a widely used model, assuming ideal plug flow and negligible intraparticle and external mass transfer resistances. This model is a suitable tool for analyzing breakthrough curves and estimating adsorption capacity for various sorbents [47,48]. The Thomas equation has the following form [46,49]:

where and are the inlet and the effluent solute concentrations at given time t (min), (L min−1 mg−1) is the Thomas model constant, (mg g−1) is the maximum solid-phase concentration of the solute, x (g) is the total mass of the adsorbent, and Q (L min−1) is the volumetric flow rate.

In fitting the adsorption isotherms to experimental data, linearized forms of the equations are often used. It has been well-documented that linearization frequently leads to erroneous estimations of the model parameters [49,50,51]. In this work, a non-linear least-squares regression analysis was therefore applied (Octave software was used). The uncertainties in fitting coefficients were estimated from the variance–covariance matrix. A comparison with the results of fitting to linearized adsorption isotherms is provided in the Supplementary Materials.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Determination of Heavy Metals in GLHP

In the first part of this study, elemental analysis of GLHP was performed using ICP-MS following acid digestion to determine the initial levels of Cd and other relevant heavy metals in applied biomass. The results, given in Table 1, represent the average of the duplicate analyses.

Table 1.

Elemental analysis of dried fungal biomass: the mass of the element per mass of GLHP, w, and corresponding relative standard deviation, RSD.

Elemental analysis showed that GLHP was rich in essential elements, including Ca, P, K, Mg, Fe, Na, Zn, Al, Mn, Cu, and Sr levels above 10 µg g−1. Additionally, Cd, Ni, Cr, Ti, Rb, and other heavy metals were detected. Ca was the most abundant element (13.9 mg g−1), followed by P (5.08 mg g−1). The amount of Cd was low, namely, 0.038 µg g−1. Previous studies by Sharif et al. [52] on Ganoderma lucidum reported similar levels for Cu, Fe, Mn, Zn, and P levels; slightly higher K, Al, B, Li, and Na; and lower levels of Ca and Mg, while other non-detected metals were below the LOD (0.4 mg g−1). However, levels of some of the most environmentally problematic heavy metals such as Cd and Cr are in line with previous studies, where the Cd levels were in the range between 0.01 and 0.1 µg g−1 [53,54]. These findings highlight the ability of GLHP to bioaccumulate and biotransform minerals from inorganic to organic forms.

3.2. Batch Adsorption Study

In the second part of the study, removal efficiency of the GLHP biomass was investigated by evaluating different pretreatment methods and physical parameters. Initially, the impact of various thermal pretreatment procedures on the removal efficiency was studied, with the results summarized in Table 2 (untreated GLHP served as a control). All applied pretreatment methods showed increased efficiency in Cd(II) adsorption as the result of improved fungus surface properties, also reported by Karimi et al. [14].

Table 2.

Cd(II) removal efficiencies for thermal pretreatment methods using 1.0 g of GLHP in a bath system of 100 mL solutions, with initial Cd(II) concentration of 1 mg L−1.

Freeze-drying is shown to be the most efficient pretreatment method as the removal efficiency increased from initial 41.1% to 50.3%. This is most likely due to increased porosity of the fungal biomass after the freeze-drying pretreatment step, as freezing induces the formation of large ice crystals, disrupting the cellular structure and creating a porous network [55]. This structural modification enhances the availability of active sites, facilitating metal ion complexation and improving overall biosorption efficiency [56,57]. Although vacuum drying allows for greater dehydration of materials, compared to dry heat methods, the minimized thermal degradation of sensitive materials [58] led to moderate improvement of efficiency (44.5%) in combination with the following freeze-drying. Drying, while reducing both biomass weight and volume and altering physical properties [55], showed a small improvement of adsorption efficiency (i.e., 41.5% and 44.3% for 40 °C and 120 °C, respectively) compared to the untreated control (41.1%). Higher Cd(II) removal efficiency in the case of drying at 120 °C compared to 40 °C is most likely due to water evaporation from GLHP material, which resulted in higher dry matter content in the remaining dried material and, therefore, a higher number of binding sites for Cd(II) adsorption per given mass of biosorbent. Whereas in the case of drying at 40 °C, higher water content was retained in GLHP, which is consistent with slightly lower removal efficiency. The observed enhancements in Cd(II) adsorption capacity using freeze-dried biomass are consistent with prior investigations employing fungal biomass for heavy metal remediation [59].

In addition to thermal pretreatment methods, physical adsorption parameters were assessed in a batch adsorption study. Hereby, it is important to note that the applied fungal biomass also consisted of a considerable percentage of finely ground particles smaller than the pore sizes of the applied filter, i.e., <0.45 µm. Therefore, the most significant physical parameter improving the adsorption process was pre-rinsing of the GLHP with MQ water, followed by drying at 110 °C for 1.5 h, and passing the material through the sieve of 42 µm to remove the smallest fraction and retain the particles of greater size, which were used for the study. In the case of the adsorption of Cd(II) in MQ water (Figure 1a, black and red), the pretreatment step was effectively applied, as the Cd(II) removal efficiency remarkably increased for each given mass, e.g., from approx. 40% to 72% at 1.0 g of added fungal biomass. By eliminating the fine particles, the post-adsorption filtration was significantly improved, and Cd(II) release was minimized, also leading to more accurate evaluation of the adsorption capacity and efficiency. Hereby, it is important to note that the pH of the solution was measured before and after batch experiments, and relatively small or negligible changes were found (ΔpH ≤ 0.04), indicating that the fungal material functions as a buffer itself and thus maintained a practically constant pH value between 5.03 and 5.31 during the adsorption for any given mass of GLHP, as shown in Table S7. Small negative changes are in accordance with the binding and/or complexation of positively charged Cd(II) ions accompanied by the release of protons from the binding sites.

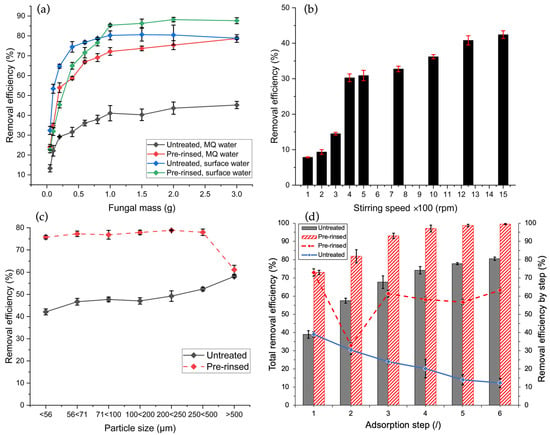

Figure 1.

Dependence of the batch system Cd(II) removal efficiency on the following: (a) added mass of fungal material (0.1–3.0 g) using untreated (black and blue) and pre-rinsed GLHPs (red and green) in 100 mL of MQ water (black and red) and surface water (blue and green) spiked with 1.0 mg L−1 Cd(II) at 500 rpm; (b) stirring speed (from 100 to 1500 rpm) using 1.0 g of untreated GLHP in 100 mL 1.0 mg L−1 Cd(II) in MQ; and (c) particle size using 1.0 g of untreated (black) and pre-rinsed GLHPs (red) of various particle sizes obtained with sieves (in the range from <56 µm to >500 µm) in 100 mL 1.0 mg L−1 Cd(II) in MQ and stirring speed of 500 rpm. (d) Dependence of sequential (multistep) Cd(II) removal efficiency with untreated (blue) and pre-rinsed GLHPs (red) and resulting total removal efficiency (gray and red-hatched columns, respectively), performed at 500 rpm in 1.0 mg L−1 Cd(II) in MQ water, using a constant mass-to-volume ratio between GLHP and solution (1.0 g fungal biomass/101 mL of solution).

To investigate the effects of surface water matrix composition and the applicability of fungal biomass for environmental remediation, adsorption batch experiments were conducted using both model MQ water and real surface water matrix collected from Glinščica stream water (Ljubljana, Slovenia; 46.051131, 14.467769). Typical physico-chemical characteristics of the Glinščica stream are given in Table S9. The initial Cd(II) concentration was set at 1.0 mg L−1 for both experiments. As reported by Gutierrez et al. [60], dissolved organic matter (DOM), a complex mixture of organic compounds ranging from small molecules to large biopolymers and humic substances, can also play an important role in sorption studies. Previous research has demonstrated that DOM can positively impact the heavy metal adsorption characteristics [61,62]. Although the determination of DOM composition in the surface water matrix was out of the scope of this work, the results in Figure 1a demonstrate that the Cd(II) adsorption efficiency was substantially higher in spiked surface water for both untreated (blue) and pre-rinsed GLHPs (green), attaining 80.3% and 85.4% removal efficiency at 1.0 g of GLHP, respectively. In comparison, the experiments conducted in DOM-free MQ water showed 41.1% and 72.2% efficiency for untreated (black) and pre-rinsed GLHPs (red), respectively, under the same conditions. Control samples of surface water without the addition of GLHP were also performed and used as a controls. Upon the introduction of Cd(II) to surface water, a decrease in Cd(II) concentration was observed, specifically from 1.0 mg L−1 to 0.8 mg L−1. This reduction is attributed to interactions between Cd(II) ions and constituents present within the surface water matrix. Cd(II) can thus undergo two primary processes, namely adsorption onto insoluble salts, e.g., calcium phosphate, or precipitation as metal phosphate compounds. Both mechanisms can contribute to the immobilization of cadmium, transforming it from a mobile ionic form into a less soluble, solid phase [63], which could be the reason for the apparent increase in the adsorption fraction of cadmium in the surface water matrix. Based on a relatively high hardness of Glinščica water [64,65], an additional reason for higher adsorption efficiencies in the real sample could also be the synergistic co-sorption/co-precipitation of Cd(II) on the surface of fungal particles in combination with other (heavy) metals and/or anions present in the real matrix, such as Ca(II), Mg(II) or (hydrogen)carbonate, sulphate, and phosphate [66,67]; however, the study of the mechanism was out of scope of this work and requires further research.

Moreover, the batch Cd(II) removal efficiency was also evaluated in the presence of other environmentally relevant heavy metals (namely: Pb(II), Co(II), Cr(III), Zn(II), Ni(II), and Mn(II)) at the same concentration levels as Cd(II) for both the untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs biosorbent (see Table S8 in the Supplementary Materials). The results showed a relatively small decrease in Cd(II) removal efficiencies in the presence of six heavy metals, i.e., from 47.2% to 44.1% for untreated and from 70.2% to 64.1% for pre-rinsed GLHPs, indicating a minor effect of competing multivalent cations and thus the applicability of GLHP for the Cd(II) adsorption under real environmental conditions.

The impact of the stirring speed on Cd(II) removal efficiency using GLHP is illustrated in Figure 1b. The removal efficiency rapidly increased from 7.85% to 30.3% with increasing stirring speed from 100 to 400 rpm using a magnetic stirrer with the following dimensions: 2.81 cm × 0.70 cm. However, further increases in the stirring speed to 1500 rpm resulted in a somewhat smaller improvement, i.e., reaching 42.4%, and did not show significant impact on the removal efficiency, which is in good agreement with the results of AjayKumer et al. [68] who reported similar adsorption behavior for activated sludge. The enhanced removal efficiency is attributed to increased turbulence, which reduces the external mass transfer resistance around the adsorbent particles. Higher stirring speed minimizes the boundary layer thickness, maximizing mass transfer and achieving maximum removal efficiency [68]. Based on the results shown in Figure 1b, a stirring speed of 500 rpm was selected as optimal and used in further experiments.

Figure 1c illustrates the cadmium adsorption efficiency of untreated and pre-rinsed GLHP particles with the use of varying particle sizes, obtained with the use of sieves with respective pore sizes. As expected, untreated GLHP (black) demonstrates an increased efficiency with larger particle size due to a lower percentage of nanoparticles (i.e., <0.45 µm) that are not removed during the filtration process (with the use of a 0.45 µm filter) and are thus present in the final eluate that was analyzed for Cd concentrations. On the other hand, pre-rinsed GLHP (red) exhibits opposite behavior and shows higher efficiency for smaller particle sizes due to the combination of (i) the preliminary removal of nanoparticles by rinsing (<0.45 µm) and (ii) higher surface-to-mass ratio (i.e., higher surface area). The latter is a well-known phenomenon for the adsorption using smaller particle sizes and is in accordance with Al-Ghouti and Al-Absi [69], who discussed that larger particle sizes generally decrease adsorption capacity due to reduced surface area, while smaller particle sizes increase the capacity by providing more adsorption sites per given mass of adsorbent. Moreover, the cadmium removal efficiency (61.1%) for the largest pre-rinsed particles of sizes > 500 µm is in line with that of untreated particles of the same size (58.1%), additionally supporting the explanation. In other words, smaller GLHP particles offer a larger surface area per mass for the adsorption but also cause filtration challenges, depending on the filter pore size selection. The optimal Cd(II) removal with pre-rinsed GLHP was observed for the 200–250 µm size range with 78.8% efficiency, as a compromise between the opposite effects of surface area and filtration considerations.

Figure 1d shows the improvement of Cd(II) removal efficiency by applying sequential adsorption steps based on the increasing number of available binding sites for the remaining free (i.e., soluble) Cd(II) in the filtrate [68]. With the use of stepwise adsorption, the total removal efficiency increased from 38.9% to 80.5% for untreated GLHP (gray column) and from 73.0% to 99.5% for pre-rinsed GLHP (red-hatched column) from the first to the fourth sequential adsorption step and remained stable thereafter, as seen from the resulting plateaus. In the case of untreated particles (blue curve), the rate of adsorption rapidly diminished with the increasing step number, which can be explained by filtration limitations and the increasing concentration of smaller GLHP particles in the filtrate, retaining the adsorbed Cd(II), as discussed above. On the other hand, a somewhat constant 70–80% removal efficiency was found for pre-rinsed biomaterial from the third to the sixth adsorption step (red curve). However, with the increasing step number, larger GLHP quantities require a significantly longer filtration and/or centrifugation process for the quantitative removal of biomass alongside adsorbed Cd(II) and can thus limit its applicability as well as accurate determination of the remaining metal concentration in the resulting filtrate.

3.3. Fixed-Bed Column Adsorption

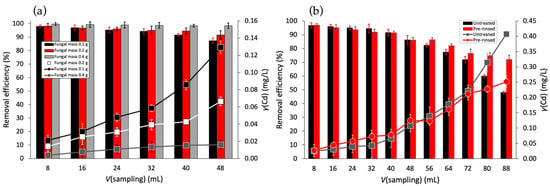

To assess the parameters of the flow-through system, the Cd(II) removal was performed in a fixed-bed column with the use of different amounts of GLHP (Figure 2a) and both untreated and pre-rinsed biomass (Figure 2b) while collecting 8 mL fractions of effluent. As shown in Figure 2a, during the continuous flow, fresh biosorbent bed effectively removes the majority of Cd(II) in the first 8 mL fraction, resulting in low remaining Cd(II) concentration level and high Cd(II) removal efficiency, i.e., 87.3%, 91.5%, and 98.4% for 0.1 g (black column), 0.2 g (red column), and 0.4 g (gray column), respectively. With further increasing volume of the effluent, the Cd(II) concentration gradually increases for 0.1 g and 0.2 g of the GLHP. As expected, the rate is higher for the bed with the lower GLHP mass due to a lower capacity and thus faster saturation of adsorption sites over volume and time [68].

Figure 2.

Dependence of the Cd(II) removal efficiency in a fixed-bed column system on the following: (a) fungal biomass (0.1 g–0.4 g) (black, red, and gray columns) at flow rate 1.0 mL min−1 of 1.0 mg L−1 Cd(II), and (b) volume of effluent using 0.2 g of untreated (black columns) and pre-rinsed GLHPs (red columns) at flow rate 1.0 mL min−1 of 1.0 mg L−1 Cd(II). All experiments were performed in MQ water.

On the other hand, the experiment with 0.4 g of GLHP showed stable residual Cd(II) levels under 0.02 mg L−1 and retained a >98% Cd(II) removal efficiency up to 48 mL of the collected effluent fraction.

Figure 2b illustrates the decrease in Cd(II) removal efficiency with the increasing effluent volume for untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs at a constant mass of 0.2 g. The untreated GLHP (black columns) exhibited a faster decline, reaching 48.1% removal efficiency at the final collected fraction at 88 mL, while the pre-rinsed GLHP (red columns) showed better performance and maintained a 72.1% removal in the same conditions. Interestingly, during the initial adsorption phase up to 48 mL, similar behavior was observed for both investigated fungal materials, suggesting that adsorption primarily occurs on larger particles retained by the filtration. Beyond this volume, the untreated GLHP exhibited a more pronounced decrease in adsorption efficiency due to the contribution of smaller particles, which passed through the filter and thus transported an additional amount of Cd(II) to the resulting effluent.

3.4. Percolation Adsorption Study

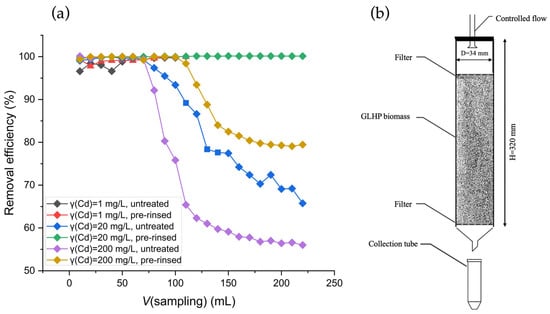

The remediation performance of GLHP was also evaluated by monitoring cadmium concentrations in the percolation effluent after the exposure of fungal biomass to various Cd(II) concentrations of the initial influent solution. This approach allowed for the assessment of heavy metal removal and potential breakthrough at different stages of the percolation process, presented in Figure 3a.

Figure 3.

(a) Dependence of Cd(II) removal efficiency in the percolation system on Cd(II) in-flow concentrations (1.0 mg L−1, 20.0 mg L−1, and 200 mg L−1), using 10 g of untreated (black, blue, and purple) and pre-rinsed GLHPs (red, green, and yellow) at a flow rate of 1.0 mL min 1. (b) Illustration of a percolation column used for percolation adsorption system.

Percolation experiments were conducted in a percolation column (Figure 3b), using 10 g of untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs with different concentrations of Cd(II) in-flow solution (1.0 mg L−1, 20 mg L−1, and 200 mg L−1). As shown in Figure 3a, the percolation system demonstrated the exceptional adsorption capacity of GLHP for Cd(II), achieving nearly complete removal at a concentration of 1 mg L−1 for both untreated (black) and pre-rinsed (red) GLHPs up to the final volume of 100 mL. Similarly, pre-rinsed GLHP (green) achieved complete removal at 20 mg L−1 Cd(II) up to 225 mL, while the capacity of untreated GLHP (blue) was notably lower as the breakthrough was reached at approx. 75 mL, and the removal efficiency is gradually reduced thereafter. The characteristic S-shaped breakthrough curve is influenced by equilibrium sorption isotherms, mass transfer within the sorbent, and hydrodynamic flow parameters. At the highest investigated concentration of 200 mg L−1, the breakthrough was reached at approx. 80 mL and 120 mL for untreated GLHP (purple) and pre-rinsed GLHP (yellow), respectively, followed by the onset of a well-defined S-shaped curve and reaching the limiting Cd(II) removal efficiency of 56% and 80%, respectively. These results clearly demonstrate the applicability of GLHP for Cd(II) removal and highlight the significant impact of the pre-rinsing step that not only increases the column capacity by approximately 50% but also significantly reduces the level of residual Cd(II) in the effluent once the breakthrough is reached.

3.5. Adsorption Kinetics

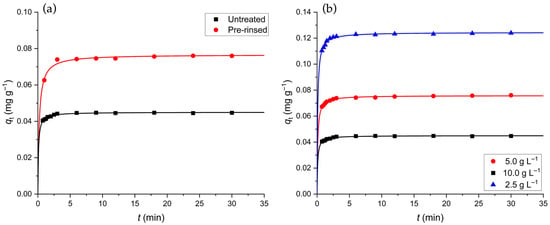

The kinetics of GLHP biosorption was determined by monitoring the decrease in Cd(II) concentrations in the adsorption medium over time using both untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs. As shown in Figure 4, pre-rinsed GLHP demonstrated a significantly higher removal efficiency than untreated GLHP, as a rapid initial adsorption rate in the first 2.5 min was followed by a gradual saturation phase at 0.045 mg g−1 and 0.075 mg g−1 for untreated (black) and pre-rinsed (red) fungal material, respectively. Equilibrium was reached within approximately 7.5 min, after which the amount of adsorbed Cd(II) remained practically constant.

Figure 4.

(a) Dependence of the mass of Cd(II) adsorbed per mass of GLHP, , on adsorption time in a batch system, conducted with 1.0 g of untreated (black) and pre-rinsed (red) GLHPs ( g L−1) with an initial Cd(II) concentration of 1.0 mg L−1 and a stirring speed of 500 rpm. (b) Comparison of for different quantities of biomass g L−1) for untreated GLHP (in all cases the initial concentration of Cd(II) was 1.0 mg L−1). Symbols denote the experimental values obtained at room temperature, while the lines designate the PSO kinetic model (Equation (5)).

Pseudo-first-order (Equation (4)), pseudo-second-order (Equation (5)), and revised pseudo-second-order (Equation (6)) kinetic models have been employed to describe the kinetics of Cd(II) biosorption onto the untreated and pre-rinsed GLHP adsorbents. The kinetic parameters ( and rate constants) obtained via non-linear least-squares regression fits to experimental data ( mg L−1, g L−1) are given in Table 3. A graphical comparison of PFO, PSO, and rPSO for this case is provided in Figure S1 in the SI, along with a comment on the use of linearized kinetic equations in the fitting process. The PFO kinetic model is the least appropriate model to describe Cd(II) adsorption onto GLHP. This is more expressed in the case of the untreated biomass (compared to pre-rinsed GLHP), where the correlation coefficient () and chi-square () are worse for the PFO model compared to PSO or rPSO. A higher value of R2 and smaller value of suggest that the pseudo-second-order models more accurately describe the Cd(II) biosorption process, which is in good agreement with the results of Rozman et al. [70]. In the case of PFO and PSO, higher values of rate constants were observed for untreated GLHP compared to pre-rinsed biomass. In the case of rPSO, the opposite holds true. For the PFO and PSO models, the rate constants ( and ) were higher for the untreated biomass, with uncertainties below 10%. For the rPSO model, this trend was reversed, but the rate constant for the pre-rinsed biomass showed high uncertainty (~38%). We believe that the rPSO model is particularly sensitive to the lack of reliable concentration data at very early times ( 1 min), which is challenging to obtain experimentally (use of automatic sampling could be beneficial here). Under the conditions used, where is comparable to , the reaction rate decreases more rapidly for the rPSO model since decreases with the uptake of the adsorbate (Equation (6)).

Table 3.

Kinetic parameters for pseudo-first-order (Equation (4)), pseudo-second-order (Equation (5)), and revised pseudo-second-order (Equation (6)) models for Cd(II) adsorption onto untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs ( g L−1 and mg L−1). All at room temperature.

It is important to note that pre-rinsing of the GLHP is not primarily a chemical activation step but a physical purification and preparation step of the biomass. In the case of the untreated biomass, the material is a fine powder that also consists of a considerable percentage of finely ground particles smaller than the pore sizes of the applied filter (<0.45 µm). The pretreatment process (rinsing with water and sieving through a 42 µm filter) was performed to remove these fine particles. The fine particles in the untreated biomass have critical advantages for rapid initial Cd(II) uptake. The collective surface area of the nano- and micro-particles is vastly greater than that of the larger, pre-rinsed particles. This provides an immense number of binding sites that are immediately available for Cd(II) adsorption. In the case of using untreated GLHP, a large population of highly efficient small particles are present in the solution. The initial adsorption is dominated by these small particles, leading to a very rapid decrease in solution concentration. A steep initial slope is directly captured by the kinetic model, resulting in a high calculated rate constant ( g mg−1 min−1). The pre-rinsed biomass, devoid of these small particles, relies solely on the larger particles. Their adsorption process is inherently slower because it is governed by the slower diffusion of ions into their porous structure. Hence, its initial rate is lower, leading to a smaller value of the rate constant ( g mg−1 min−1). The larger rate constant for untreated biomass is therefore a genuine reflection of the superior initial mass transfer and kinetics provided by its fine particle fraction. Why then does the pre-rinsed biomass has a higher equilibrium capacity, , compared to untreated GLHP? The pre-rinsed biomass, with its smaller rate constant, possesses a higher and more accessible total capacity, which is why it performs better in all equilibrium and continuous-flow experiments (see also the results of the adsorption study, Section 3.2). The initial rate and the final capacity are therefore controlled by different factors. The nanoparticles in the untreated biomass are excellent at rapid, surface-level adsorption. However, they may have limited internal capacity, and, more importantly, they create a problem of site saturation and inaccessibility. As these small particles adsorb Cd(II) ions, they might agglomerate or block the pores of the larger particles, preventing the bulk of the biomass from reaching its full adsorption potential. The untreated GLHP system reaches a local equilibrium quickly but at a low overall capacity ( mg g−1). By removing these nanoparticles (pre-rinsing), only larger particles with a larger internal network of pores and binding sites are left. While it takes longer for ions to diffuse into these sites (slower rate constant), the total number of available sites is much higher. The adsorption process of pre-rinsed GLHP is thus slower but more thorough, leading to a significantly higher equilibrium capacity ( mg g−1).

It has been argued that the PSO rate constant, , can depend on the initial experimental conditions [33,34]. We performed additional kinetic experiments with varying amounts of untreated biomass, g L−1 (Figure 4b). A global fit of the PSO kinetic model on these three sets of experimental data was performed, where the rate constant, , served as the global fitting parameter. The value of g mg−1 min−1 was obtained with the global fit, while the values of the rate constant for individual cases were g mg−1 min−1 ( g L−1), g mg−1 min−1 ( g L−1), and g mg−1 min−1 ( g L−1). One can see that the reported values of are all within numerical uncertainty. We conclude that the biosorption process is most likely controlled by a second-order kinetic mechanism. While the PSO (and rPSO) model is empirically successful, the determining factor for the adsorption rate in this system appears to be the physical accessibility of binding sites rather than the chemisorption reaction rate alone [71].

PFO and PSO models are rate-law equations not mechanistic models. The better performance of the PSO (rPSO model in our case), as is also common in the literature, is probably due to its mathematical flexibility and should not be directly equated with the adsorption mechanism. True mechanistic insight comes from applying diffusion-based and surface-reaction-based models, correlating kinetic data with independent spectroscopic and microscopic evidence of the metal–adsorbent interaction, and understanding the chemical nature of the adsorbent surface and the aqueous chemistry of the metal ion. Many studies interpret good agreement of the PSO model with experimental data as evidence of a chemisorption mechanism. Without additional spectroscopic measurements (e.g., FTIR [72]), it is not possible to state that the chemisorption of Cd2+ ions on GLHP is the predominant mechanism, although it is very plausible.

3.6. Adsorption Isotherms

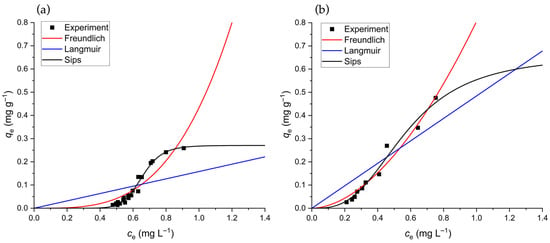

The adsorption behavior of Cd(II) ions onto GLHP was examined through isothermal equilibrium adsorption experiments. The experimental data were modeled using the Freundlich [73], Langmuir [74], and Freundlich–Langmuir [44] adsorption isotherms. To describe column adsorption performance, the Thomas model [75] was used. In all cases, non-linear least-squares regression analysis (Equations (7)–(9)) was employed. A comment on the use of linearized versions of the isotherms in the fitting process is given in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 5 shows the equilibrium adsorption behavior of Cd(II) ions onto the untreated (Figure 5a) and pre-rinsed (Figure 5b) GLHPs in a batch system. A sigmoidal shape of the amount of Cd(II) ions adsorbed at equilibrium, , upon the increasing equilibrium concentration of Cd(II), , is observed in both cases. From the experimental trends, it is evident that the often used Freundlich (Equation (7)) and Langmuir (Equation (8)) adsorption isotherms are not suitable for modeling presented adsorption data. The Langmuir model assumes a monolayer adsorption onto a homogeneous surface with a finite number of identical adsorption sites. Saturation occurs when all sites are occupied [76,77]. The Freundlich model, by contrast, can in principle be applied to cases of multilayer adsorption on a heterogeneous surface, where the adsorption energy decreases exponentially as the adsorption process progresses [78]. Furthermore, as the concentration increases, the Freundlich model does not imply a limited surface coverage. Both Freundlich and Langmuir isotherms, obtained by fitting Equation (7) and Equation (8), respectively, to experimental data, are shown in Figure 5. It can be seen that neither isotherm is suitable for an accurate description of Cd(II) adsorption onto GLHP. The coefficients of the Langmuir and Freundlich adsorption isotherms shown in Figure 5 are given in Table S3 in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 5.

Dependence of the amount of adsorbed Cd(II) ions, , as a function of Cd(II) at equilibrium, , for (a) untreated and (b) pre-rinsed GLHPs. Symbols denote the experimental data obtained at room temperature, and lines show Freundlich (red, Equation (7)), Langmuir (blue, Equation (8)), and Sips (black, Equation (9)) adsorption isotherms.

The Sips adsorption isotherm (also called the Langmuir–Freundlich isotherm) incorporates the concept of maximum capacity, (from the Langmuir model), while also accounting for surface heterogeneity (from the Freundlich model) through exponent . The shape of the Sips isotherm (Equation (9)) is highly flexible and can model different types of adsorption behavior based on the value of . For the isotherm adopts a sigmoidal (S-shaped) form [79]. In Figure 5, one can see that the Sips isotherm adequately describes the experimental trends both in the case of untreated and pre-rinsed adsorbents. The values of the model parameters ( and ) are given in Table 4. The application of the Sips model can provide further insight into the impact of the pre-rinsing process. A significantly larger maximum adsorption capacity for the pre-rinsed biomass was obtained ( mg g−1) compared to the untreated material ( mg g−1). This is because the removal of nano-sized particles (<45 μm) in the rinsing process eliminates pore-blocking and unveils the full, heterogeneous network of binding sites within the macroporous fungal structure, which is in good accordance with the results of the kinetics study (Section 3.5) and SEM images (Figure S5). SEMs showed the heterogeneous surface of the GLHP with a rough texture and irregular pattern. These morphological features result in the large specific surface area of the material and porosity and are therefore favorable for the biosorption process. The larger Sips exponent for the untreated GLHP () suggests an apparent homogeneity in its adsorption behavior. This is interpreted not as an intrinsic property of the fungal biomass itself but as evidence that the adsorption process is dominated by a uniform population of sub-micron particles (<45 μm). In contrast, the lower value for the pre-rinsed biomass () more accurately reflects the inherent chemical and structural heterogeneity of the native fungal cell wall, which was unmasked by the removal of the fine particle and which possesses a wide variety of binding sites with differing affinities for Cd(II) ions. The shift in can be mechanistically explained by the change in the dominant physical structure. The high value of of the untreated biomass reflects a system dominated by a uniform population of fine external particles (<45 μm), offering similar, readily accessible sites. Pre-rinsing removes this masking fraction, exposing the inherent heterogeneous porous network of the fungal biomass. The resultant lower directly quantifies the broad energy distribution of adsorption sites arising from the complex particle size distribution, varied pore accessibility (from open macropores to restricted micropores), and the total accessible internal surface area of the larger, intact particles. The affinity of the GLHP for Cd(II) ions was evaluated by comparing the equilibrium constant () of the Sips model. The pre-rinsed GLHP exhibited a slightly higher value ( L mg−1) compared to the untreated biomass ( L mg−1), indicating a stronger adsorption intensity and higher affinity for Cd(II) ions under these conditions. However, due to a large uncertainty in the in the case of pre-rinsed GLHP, one needs to compare these two values with care. The greater uncertainty in the fitting parameters for pre-rinsed biomass compared to untreated GLHP (Table 4) is largely attributed to the more limited number of experimental data points for the pre-rinsed case. Nevertheless, from kinetic and adsorption studies, the pre-rinsed material is more suitable for the target contaminant (Cd2+) compared to untreated GLHP [80].

Table 4.

Parameters of the Sips isotherm (Equation (9)) and Thomas model (Equation (10)) for Cd(II) adsorption on untreated and pre-rinsed GLHP biosorbents. All at room temperature.

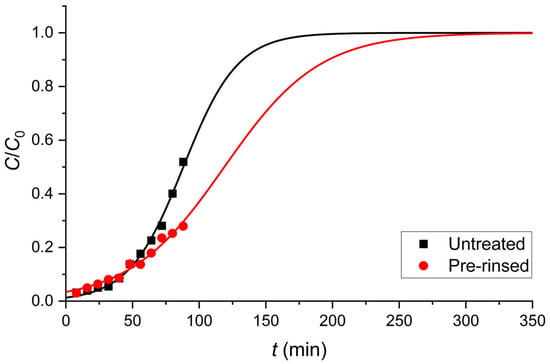

In the last part of this study, we present the column adsorption performance. Experimental data for untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs are shown in Figure 6. The Thomas model (Equation (10)) provides valuable insights into the maximum amount of pollutants that can be adsorbed per gram of adsorbent. Model parameters—the adsorption capacity () and rate constant () for the column system—were obtained via non-linear least-squares regression and are given in Table 4, while the model functions are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The column adsorption performance for untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs (0.2 g) in the case of Cd(II) removal in the column system (flow rate Q = 1.0 mL min−1). Symbols denote the experimental data obtained at room temperature, and lines show the Thomas model (Equation (10)).

The application of the Thomas model to the column adsorption data yielded a good fit for both biosorbents ( > 0.97), confirming its suitability for describing the kinetics of the column adsorption process under these flow conditions and also indicating that external and internal diffusion limitations are negligible during the adsorption process [81]. The model provided two key quantitative insights. First, utilizing a sorbent mass of 0.2 g, the maximum Cd(II) adsorption capacity, , was significantly higher for the pre-rinsed GLHP ((0.53 ± 0.01) mg g−1) compared to the untreated material ((0.345 ± 0.004) mg g−1). This ~54% increase in column capacity is consistent with the batch isotherm studies and conclusively demonstrates that the pre-rinsing process enhances the total number of usable binding sites by removing very small particles that would otherwise cause pore-blocking and inefficient bed packing. The superior adsorption capacity of the pre-rinsed biosorbent is also consistent with previous batch studies by Sankararamakrishnan et al. [82]. The improvement ratio between untreated and pre-rinsed GLHPs was estimated from the data shown in Figure 3a. For 200 mg/L Cd(II), the breakthrough volume increased from ~75 mL (untreated biomass) to ~110 mL (pre-rinsed biomass), corresponding to an improvement factor of 1.47 (110 mL/75 mL). This aligns well with the 1.54-fold increase in the Thomas model capacity (q0) from 0.345 mg g−1 to 0.53 mg g−1.

Second, the Thomas rate constant, , was notably larger for the untreated biomass. This result, which may seem counterintuitive at first, aligns with the kinetic findings from the batch studies. In the column, the untreated biomass’s population of nano-sized particles provides a large external surface area for rapid initial adsorption, leading to a steeper initial breakthrough curve that the model interprets as a faster rate constant (see Figure 6). However, this initial kinetic advantage is short-lived. The pre-rinsed biomass, while exhibiting a smaller due to its reliance on intra-particle diffusion, possesses a more robust and accessible porous structure, which is why it achieves a much higher total capacity () and maintains a lower effluent concentration for a longer time. This trade-off between the initial adsorption rate and total usable capacity underscores the critical importance of the pre-rinsing step for practical, long-term column operation.

Table 5 summarizes the performances of various types of fungal biomasses and other common (bio)sorbent materials for Cd(II) removal from aqueous solutions. In comparison to fungal biosorbents, the pre-rinsed GLHP showed a similar removal efficiency (85.4%); however, it is important to note the significantly (i.e., 10–80×) shorter contact times required to reach its maximum capacity (6 min), emphasizing its applicability for time-efficient water treatment. Some synthesized sorbents, such as Ca-MOFs and nanocomposites, exhibit higher sorption capacities and efficiencies compared to fungal biosorbents in general; however, their practical application can often be limited by instability, high prices, toxicity, and challenges with large-scale synthesis [8]. On the other hand, since GLHP is obtained from industrial food-supplement production, this work underlines the potential scalability for rapid Cd(II) removal, as well as further improvements of the sorption capacity with a simple pre-rinsing step without the use of any toxic chemicals.

Table 5.

Comparison of selected fungal and other (bio)sorbents for Cd(II) removal efficiency (all studies performed at (25 ± 5) °C).

4. Conclusions

The presence and persistence of Cd(II) and other heavy metals in the environment presents a critical challenge to both human health and ecosystems. This study systematically evaluates the performance of GLHP for Cd(II) removal, including in a batch, column, and percolation configuration. Utilizing thermal pretreatment and the simple pre-rinsing of fungal biomass, the investigated material showed a significantly improved Cd(II) biosorption capacity and fast adsorption kinetics. The process adhered to a pseudo-second-order kinetic model, while kinetic evaluations revealed surface heterogeneity and a broad range of active adsorption sites, consistent with the Sips isotherm and Thomas model. Beyond cadmium, GLHP’s success underscores its applicability for other heavy metals removal, exhibiting prospects for environmental clean-up initiatives, and could be further explored, together with other fungal biomasses, as part of integrated strategies for managing heavy metal exposure. Since the GLHP is a commercially available, well-controlled, and standardized dietary supplement product in accordance with HACCP (Hazard Analysis and Critical Control Points) food safety standards and has been accessible on the market for over 15 years, it shows applicability not only for wastewater but also for drinking water purification. Its minimized chances of side effects are further supported by utilizing a pre-rinsing step with ultrapure water, completely omitting any potentially toxic chemical pretreatment. Thus, this work could serve as a foundation for in vivo and/or clinical studies related to acute and chronic heavy metal poisoning. By integrating efficiency, cost-effectiveness, scalability, and sustainability, GLHP presents an adaptable solution for comprehensive water purification and thus environmental and public health benefits.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010448/s1. Figure S1: Comparison of PFO, PSO and rPSO kinetic models for describing the dependence of the mass of Cd(II) adsorbed per mass of GLHP. Table S1: Equations for various linearizations of the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Table S2: Parameters qe and k2 of the PSO model. Figure S2: Comparison of PSO adsorption kinetic theory from nonlinear fit and from parameters obtained using type 1 linearization with experimental data. Figure S3: Plots of the linearized PSO kinetic model. Table S3: Parameters of the Freundlich and Langmuir isotherm. Table S4: Parameters of the Thomas model. Figure S4: Fit for the linearized Thomas model and comparison of Thomas model. Figure S5: SEM images of GLHP. Table S5: Particle size distribution of GLHP biomass. Table S6: Nutritional composition of GLHP biomass. Table S7: Dependence of pH for batch setup before and after adsorption. Table S8: Dependence of the batch system Cd(II) removal efficiency in the absence and presence of the competing heavy metals. Table S9: Chemical characteristics of Glinščica steam water.

Author Contributions

T.K.: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Investigation, and Data curation. A.G.: Writing—review and editing, Conceptualization, Methodology, and Validation. M.L.: Writing—review and editing, Methodology, and Validation. G.M.: Writing—original draft, Writing—review and editing, Methodology, Validation, Supervision, and Conceptualization. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge the financial support from the Slovenian Research and Innovation Agency—research core funding no. P1-0153 and P1-0201.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Doris Bračič from University of Maribor, Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Maribor, Slovenia for conducting SEM analysis of the samples.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Andrej Gregori was employed by the University of Ljubljana and MycoMedica Ltd. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Mishra, S.; Bharagava, R.N.; More, N.; Yadav, A.; Zainith, S.; Mani, S.; Chowdhary, P. Heavy metal contamination: An alarming threat to environment and human health. In Environmental Biotechnology: For Sustainable Future; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 103–125. [Google Scholar]

- Das, S.; Sultana, K.W.; Ndhlala, A.R.; Mondal, M.; Chandra, I. Heavy metal pollution in the environment and its impact on health: Exploring green technology for remediation. Environ. Health Insights 2023, 17, 11786302231201260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Say, R.; Yilmaz, N.; Denizli, A. Removal of heavy metal ions using the fungus Penicillium canescens. Adsorpt. Sci. Technol. 2003, 21, 643–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Viraraghavan, T. Fungal biosorption—An alternative treatment option for heavy metal bearing wastewaters: A review. Bioresour. Technol. 1995, 53, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Dhankhar, R.; Hooda, A. Fungal biosorption—An alternative to meet the challenges of heavy metal pollution in aqueous solutions. Environ. Technol. 2011, 32, 467–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abd El-wahaab, B.; El-Shwiniy, W.H.; Alrowais, R.; Nasef, B.M.; Said, N. Adsorption of Lead (Pb(II)) from Contaminated Water onto Activated Carbon: Kinetics, Isotherms, Thermodynamics, and Modeling by Artificial Intelligence. Sustainability 2025, 17, 2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burakov, A.E.; Galunin, E.V.; Burakova, I.V.; Kucherova, A.E.; Agarwal, S.; Tkachev, A.G.; Gupta, V.K. Adsorption of heavy metals on conventional and nanostructured materials for wastewater treatment purposes: A review. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 148, 702–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, G.-R.; An, Z.-H.; Xu, K.; Liu, Q.; Das, R.; Zhao, H.-L. Metal organic framework (MOF)-based micro/nanoscaled materials for heavy metal ions removal: The cutting-edge study on designs, synthesis, and applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2021, 427, 213554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowalik-Klimczak, A. Removal of Heavy Metals from Galvanic Industry Wastewater: A Review of Different Possible Methods. Sustainability 2025, 17, 8562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldrian, P. Interactions of heavy metals with white-rot fungi. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 2003, 32, 78–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bibbins-Martínez, M.; Juárez-Hernández, J.; López-Domínguez, J.Y.; Nava-Galicia, S.B.; Martínez-Tozcano, L.J.; Juárez-Atonaľ, R.; Cortés-Espinosa, D.; Díaz-Godinez, G. Potential application of fungal biosorption and/or bioaccumulation for the bioremediation of wastewater contamination: A review. J. Environ. Biol. 2023, 44, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Wet, M.M.; Brink, H.G. Lead Biosorption Characterisation of Aspergillus piperis. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomina, M.; Gadd, G.M. Biosorption: Current perspectives on concept, definition and application. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 160, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karimi, K.; Shafiei, M.; Kumar, R. Progress in physical and chemical pretreatment of lignocellulosic biomass. In Biofuel Technologies: Recent Developments; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2013; pp. 53–96. [Google Scholar]

- Javaid, A.; Bajwa, R.; Manzoor, T. Biosorption of heavy metals by pretreated biomass of Aspergillus niger. Pak. J. Bot. 2011, 43, 419–425. [Google Scholar]

- Akar, T.; Tunali, S. Biosorption characteristics of Aspergillus flavus biomass for removal of Pb (II) and Cu (II) ions from an aqueous solution. Bioresour. Technol. 2006, 97, 1780–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, A.; Viraraghavan, T. Biosorption of heavy metals on Aspergillus niger: Effect of pretreatment. Bioresour. Technol. 1998, 63, 109–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pino, G.H.; De Mesquita, L.M.S.; Torem, M.L.; Pinto, G.A.S. Biosorption of cadmium by green coconut shell powder. Miner. Eng. 2006, 19, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.; Puri, A. A review of permissible limits of drinking water. Indian J. Occup. Environ. Med. 2012, 16, 40–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Satarug, S.; Garrett, S.H.; Sens, M.A.; Sens, D.A. Cadmium, environmental exposure, and health outcomes. Cien. Saude Colet. 2011, 16, 2587–2602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kubier, A.; Wilkin, R.T.; Pichler, T. Cadmium in soils and groundwater: A review. Appl. Geochem. 2019, 108, 104388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Zhou, S.; Jiang, W.; Huang, M.; Dai, X. Effects of Ganopoly® (A ganoderma lucidum polysaccharide extract) on the immune functions in Advanced-Stage cancer patients. Immunol. Investig. 2003, 32, 201–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yan, X.-H.; Zhang, J.-L.; Wang, L.-Y.; Xue, H.; Jiang, G.-C.; Ma, X.-T.; Liu, X.-J. Characterization, hypolipidemic and antioxidant activities of degraded polysaccharides from Ganoderma lucidum. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 135, 706–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Xue, J.; Yang, X.; Zhang, Y. Structural characteristics of a heteropolysaccharide from Ganoderma lucidum and its protective effect against Alzheimer’s disease via modulating the microbiota-gut-metabolomics. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 297, 139863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.; He, R.; Sun, P.; Zhang, F.; Linhardt, R.J.; Zhang, A. Molecular mechanisms of bioactive polysaccharides from Ganoderma lucidum (Lingzhi), a review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 150, 765–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernard, A. Cadmium & its adverse effects on human health. Indian J. Med. Res. 2008, 128, 557–564. [Google Scholar]

- Jelen, Ž.; Svetec, M.; Majerič, P.; Kapun, S.; Resman, L.; Čeh, T.; Hajra, G.; Rudolf, R. Contaminants in the Soil and Typical Crops of the Pannonian Region of Slovenia. Sustainability 2024, 16, 8678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gluhar, S.; Jez, E.; Lestan, D. The use of zero-valent Fe for curbing toxic emissions after EDTA-based washing of Pb, Zn and Cd contaminated calcareous and acidic soil. Chemosphere 2019, 215, 482–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizjak, M.Č.; Pražnikar, Z.J.; Kenig, S.; Hladnik, M.; Bandelj, D.; Gregori, A.; Kranjc, K. Effect of erinacine A-enriched Hericium erinaceus supplementation on cognition: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. J. Funct. Foods 2024, 115, 106120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.L.; Hameed, B.H. Insight into the adsorption kinetics models for the removal of contaminants from aqueous solutions. J. Taiwan Inst. Chem. Eng. 2017, 74, 25–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keberle, H. The biochemistry of desferrioxamine and its relation to iron metabolism. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1964, 119, 758–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ho, Y.-S.; McKay, G. Pseudo-second order model for sorption processes. Process Biochem. 1999, 34, 451–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plazinski, W.; Rudzinski, W.; Plazinska, A. Theoretical models of sorption kinetics including a surface reaction mechanism: A review. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 152, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullen, J.C.; Saleesongsom, S.; Gallagher, K.; Weiss, D.J. A revised pseudo-second-order kinetic model for adsorption, sensitive to changes in adsorbate and adsorbent concentrations. Langmuir 2021, 37, 3189–3201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Revellame, E.D.; Fortela, D.L.; Sharp, W.; Hernandez, R.; Zappi, M.E. Adsorption kinetic modeling using pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws: A review. Clean. Eng. Technol. 2020, 1, 100032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal, M.C.; Onursal, N. Two new linearized equations derived from the pseudo-second-order kinetic model. Desalin. Water Treat. 2023, 308, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, H.N. Applying linear forms of pseudo-second-order kinetic model for feasibly identifying errors in the initial periods of time-dependent adsorption datasets. Water 2023, 15, 1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eaton, J.W.; Bateman, D.; Hauberg, S. GNU Octave Version 4.2.1 Manual: A High-Level Interactive Language for Numerical Computations. 2017. Available online: https://docs.octave.org/octave-4.2.0.pdf (accessed on 11 November 2025).

- Foo, K.Y.; Hameed, B.H. Insights into the modeling of adsorption isotherm systems. Chem. Eng. J. 2010, 156, 2–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundlich, H. Über die adsorption in lösungen. Z. Phys. Chem. 1907, 57, 385–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langmuir, I. The constitution and fundamental properties of solids and liquids. Part I. Solids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1916, 11, 2221–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keren, Y.; Borisover, M.; Bukhanovsky, N. Sorption interactions of organic compounds with soils affected by agricultural olive mill wastewater. Chemosphere 2015, 138, 462–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohn, S.; Kim, D. Modification of Langmuir isotherm in solution systems—Definition and utilization of concentration dependent factor. Chemosphere 2005, 58, 115–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azizian, S.; Eris, S. Adsorption isotherms and kinetics. In Interface Science and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; Volume 33, pp. 445–509. ISBN 1573-4285. [Google Scholar]

- Azizian, S.; Eris, S.; Wilson, L.D. Re-evaluation of the century-old Langmuir isotherm for modeling adsorption phenomena in solution. Chem. Phys. 2018, 513, 99–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Yue, Q.; Gao, B.; Li, Q.; Xu, X.; Fu, K. Adsorption of hexavalent chromium from aqueous solution by modified corn stalk: A fixed-bed column study. Bioresour. Technol. 2012, 113, 114–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, F.; Talpur, F.N.; Balouch, A.; Afridi, H.I.; Khaskheli, A.A. Efficient entrapping of toxic Pb (II) ions from aqueous system on a fixed-bed column of fungal biosorbent. Geol. Ecol. Landsc. 2018, 2, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makrigianni, V.; Giannakas, A.; Hela, D.; Papadaki, M.; Konstantinou, I. Adsorption of methylene blue dye by pyrolytic tire char in fixed-bed column. Desalin. Water Treat. 2017, 65, 346–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-López, M.E.; Laureano-Anzaldo, C.M.; Pérez-Fonseca, A.A.; Arellano, M.; Robledo-Ortíz, J.R. A discussion on linear and non-linear forms of Thomas equation for fixed-bed adsorption column modeling. Rev. Mex. Ing. Quím. 2021, 20, 875–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Wang, J. Comparison of linearization methods for modeling the Langmuir adsorption isotherm. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 296, 111850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, F.; Chu, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, F.; Bhandari, N.; Ruan, G.; Dai, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Kan, A.T. Determination of adsorption isotherm parameters with correlated errors by measurement error models. Chem. Eng. J. 2015, 281, 921–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharif, S.; Mustafa, G.; Munir, H.; Weaver, C.M.; Jamil, Y.; Shahid, M. Proximate composition and micronutrient mineral profile of wild Ganoderma lucidum and four commercial exotic mushrooms by ICP-OES and LIBS. J. Food Nutr. Res 2016, 4, 703–708. [Google Scholar]

- Tham, L.X.; Matsuhashi, S.; Kume, T. Responses of Ganoderma lucidum to heavy metals. Mycoscience 1999, 40, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussien, Z.G. Chemical content study in Ganoderma lucidum commercial products. System 2022, 1, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, L.-Z.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Zhang, Q.; Yang, X.-H.; Wang, J.; Zheng, Z.-A.; Gao, Z.-J.; Xiao, H.-W. Chemical and physical pretreatments of fruits and vegetables: Effects on drying characteristics and quality attributes–a comprehensive review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 1408–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, A.I.; El-Monaem, E.M.A.; Elgarahy, A.M.; Aniagor, C.O.; Hosny, M.; Farghali, M.; Rashad, E.; Ejimofor, M.I.; Lopez-Maldonado, E.A.; Ihara, I. Methods to prepare biosorbents and magnetic sorbents for water treatment: A review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2023, 21, 2337–2398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, W.; Xu, J.; Gao, L.; Zhang, Q.; Tong, J.; Ren, L. Preparation of freeze-dried porous chitosan microspheres for the removal of hexavalent chromium. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubbard, B.R.; Putman, L.I.; Techtmann, S.; Pearce, J.M. Open source vacuum oven design for low-temperature drying: Performance evaluation for recycled PET and biomass. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2021, 5, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.P.; Westman, D.; Quirk, K.; Huang, J.P. The removal of cadmium (II) from dilute aqueous solutions by fungal adsorbent. Water Sci. Technol. 1988, 20, 369–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, M.; Verlicchi, P.; Mutavdžić Pavlović, D. Study of the influence of the wastewater matrix in the adsorption of three pharmaceuticals by powdered activated carbon. Molecules 2023, 28, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guillossou, R.; Le Roux, J.; Mailler, R.; Pereira-Derome, C.S.; Varrault, G.; Bressy, A.; Vulliet, E.; Morlay, C.; Nauleau, F.; Rocher, V. Influence of dissolved organic matter on the removal of 12 organic micropollutants from wastewater effluent by powdered activated carbon adsorption. Water Res. 2020, 172, 115487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, J.; Xu, L.; Xu, Q.; Wu, D.; Ai, Y.; Li, D.; Liu, W.; Qu, J.; Wang, L. The effect and spectral response mechanism of dissolved organic matter (DOM) in Pb (II) adsorption onto biochar. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11, 111115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebri, S.; Jaouadi, M.; Khattech, I. Precipitation of cadmium in water by the addition of phosphate solutions prepared from digested samples of waste animal bones. Desalin. Water Treat. 2021, 217, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klun, B.; Starin, M.; Novak, J.; Putar, U.; Korošin, N.Č.; Binda, G.; Kalčíková, G. Biofilm formation on polyethylene and polylactic acid microplastics in freshwater: Influence of environmental factors. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 118689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]