1. Introduction

Eradicating poverty and reducing inequality are crucial objectives among the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) established by the United Nations. Income inequality remains one of the most severe challenges facing developing countries [

1,

2]. Owing to lower levels of economic development, heightened inequality is more likely to push a larger share of the population into abject poverty in developing economies, and income disparities tend to widen further as economic growth proceeds. Poverty in developing countries is largely a rural phenomenon [

3]. The urban–rural income gap constitutes a significant component of national inequality, constraining progress toward SDGs [

4,

5]. As the world’s largest developing country, China has successfully eliminated abject poverty [

6]. However, income inequality, particularly the large disparity between urban and rural income as its primary source, remains a prominent issue [

7,

8,

9,

10]. Increasing the income of rural residents is key to narrowing the urban–rural income gap. Unlike urban areas, which benefit from advantages in capital accumulation, human resources, and institutional capacity, rural regions possess the comparative advantage of abundant ecological resources [

11]. These resources can serve as productive assets underpinning green industries, eco–tourism, and ecosystem service markets, with ownership, management rights, or usage rights held by rural residents [

12,

13]. How to transform ecological resources into a source and foundation for income growth among rural residents while simultaneously protecting them is a critical issue for reducing inequality and achieving sustainable development in China and other developing countries worldwide.

The National Ecological Civilization Pilot Zone (NECPZ) policy in China provides valuable practical experience for exploring this issue. Since 2016, the Chinese government has successively designated Fujian, Jiangxi, Guizhou, and Hainan provinces, which possess relatively sound ecological foundations and strong resource and environmental carrying capacities, as NECPZs. Compared with traditional environmental policies, the NECPZ policy integrates a broader set of policy instruments and pursues more diversified objectives. In terms of instruments, it encompasses both command–and–control environmental regulations and market–based incentives, together with measures to promote green industrial development [

14]. With respect to objectives, the policy seeks to achieve multiple benefits across environmental and economic dimensions, as well as regional and individual levels. Implemented at the provincial level, the NECPZ facilitates coordination among diverse policy measures, bridges gaps across different policy domains, and mitigates conflicts between policy goals. Consequently, the NECPZ policy enhances ecological governance, improves economic performance, and contributes to raising rural residents’ income.

Existing literature has examined the impact of various ecological and environmental protection policies on rural residents’ income. These policies encompass initiatives targeting different ecosystem services or specific regions, such as biodiversity conservation, carbon emissions trading, and the establishment of nature reserves. Research indicates that biodiversity conservation policies have demonstrated effects in improving rural livelihoods and reducing poverty in Guatemala, Cambodia, and Tanzania [

15]. Nature reserve policies and carbon emissions trading schemes have also been demonstrated to positively impact rural residents’ income [

16,

17]. Nevertheless, these studies primarily focus on evaluating single, independently implemented policies, with limited attention to integrated policy frameworks. In the case of the NECPZ, as a comprehensive policy initiative, existing literature has examined its effects from corporate and macro perspectives of environmental and economic dimensions. Research indicates that NECPZs have fostered corporate green innovation [

18], enhanced green economic efficiency [

19], and promoted environmental–economic synergies [

20,

21]. However, the lack of research on the impact of the NECPZ on rural residents’ income highlights a gap in understanding both the comprehensive effects of NECPZ and the broader relationship between ecological and environmental policies and rural residents’ income. This study seeks to address this gap by investigating the following questions: Does the NECPZ policy increase rural residents’ income levels? Through what mechanisms do these policies generate such effects? And does the impact of the policy vary across different development conditions?

This study examines the above issues by constructing a panel dataset covering 1761 counties in China from 2010 to 2022 and applying a staggered difference–in–differences model. The empirical results indicate that the establishment of NECPZ contributes to fostering income growth among rural residents. Specifically, the NECPZ enhances rural residents’ income levels by increasing ecological fiscal support, promoting eco–industry development, and expanding non-agricultural employment. To further explore policy implementation patterns, this study conducts a heterogeneity analysis of the policy effects within the pilot zones. Results suggest that the NECPZ policy exerts a stronger impact on relatively low-income rural regions compared to those with higher income levels. Moreover, regarding the pathways through which the policy influences rural residents’ income, the analysis reveals that the policy demonstrates more pronounced positive income effects in central-western regions and areas with higher agricultural endowments, stronger local fiscal self-sufficiency, and greater entrepreneurial dynamism.

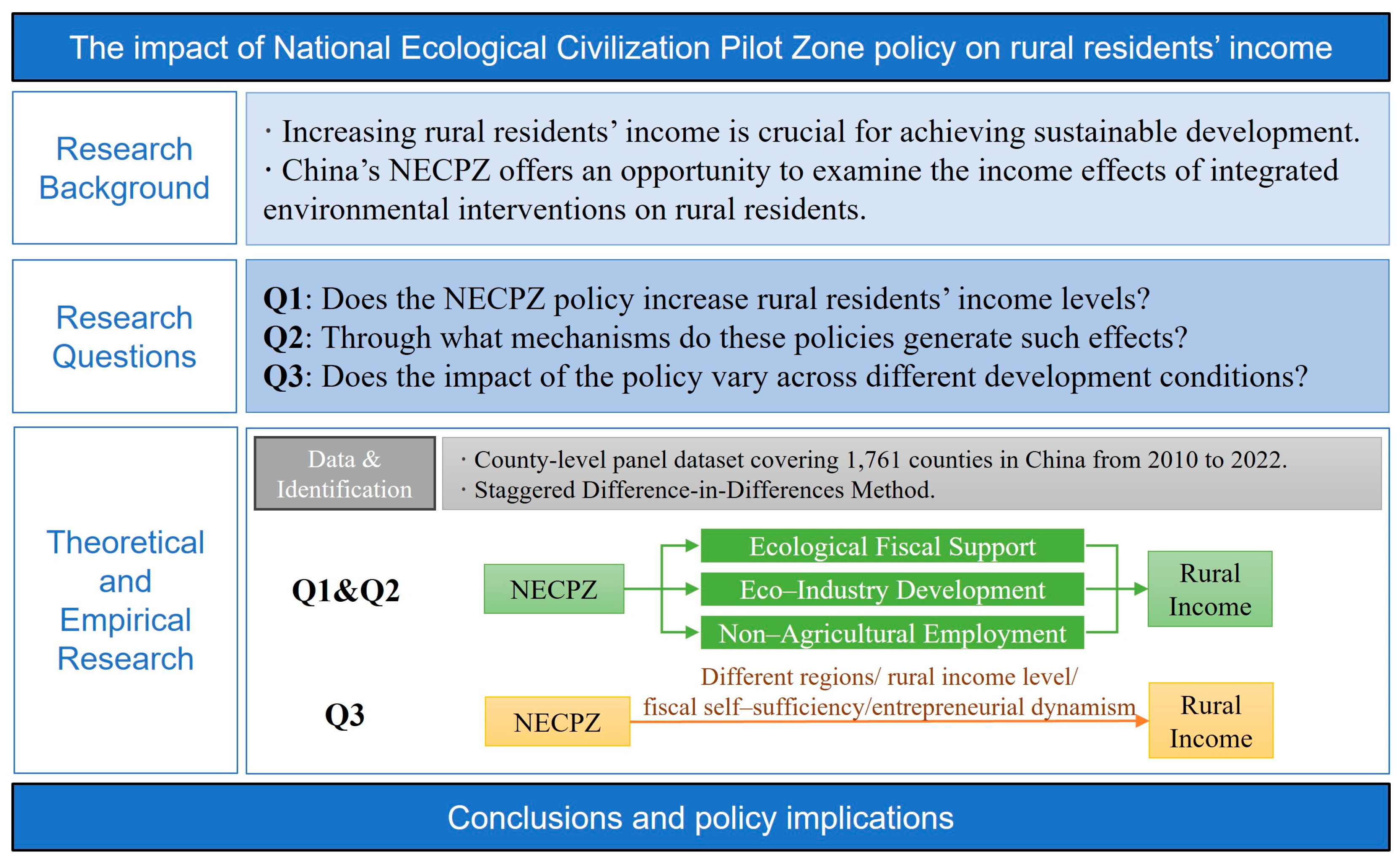

Figure 1 illustrates the research framework of this study.

This study makes three main contributions. First, it provides empirical evidence for how the NECPZ policy affects rural residents’ income, a dimension largely overlooked in previous studies. By further identifying the pathways through which the policy operates, this study offers deeper insights of the mechanisms underlying the policy’s income effects. Second, this study is conducted at the county level. The NECPZ is a macro–level initiative integrating central government top–down planning with local government innovation. By identifying policy impacts within finer spatial units, this study helps reveal the effectiveness of this macro–level policy at the county level. Third, this study employs heterogeneity analysis to examine policy implementation outcomes across counties with varying development conditions. Since counties serve as fundamental units for China’s economic development and social governance, the findings offer useful implications for the targeted implementation of the policy. Overall, by examining the impact of the NECPZ on rural residents’ income, this research contributes to the broader literature on protecting and utilizing ecological resources to improve rural livelihoods, offering valuable insights for developing countries facing similar challenges.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the policy background and presents the research hypotheses.

Section 3 describes the research methodology, data, and variable definitions.

Section 4 reports the empirical results.

Section 5 discusses the results.

Section 6 concludes with a summary of the main findings and policy implications.

Section 7 outlines the study’s limitations and prospects.

2. Policy Background and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Policy Background

In 2016, the Chinese government issued the Opinions on Establishing a Unified and Standardized National Ecological Civilization Pilot Zone to guide the construction of a national–level comprehensive platform for ecological civilization system reform. The NECPZ aims to establish institutional frameworks that improve ecological quality, promote green development, and enhance public benefits from ecological construction. Fujian Province was designated as the first NECPZ in 2016, with its implementation plan issued the same year. Subsequently, Jiangxi, Guizhou, and Hainan Provinces issued their respective implementation plans in 2017 and 2019. In this study, the issuance of the implementation plan is used as the effective policy start date in the empirical analysis. Accordingly, the sample period spans from 2010 to 2022, which allows for the examination of policy impacts before and after implementation.

The NECPZ policy encompasses five core dimensions of intervention (see

Table 1). Ecological and environmental governance, natural resource management, and ecological compensation primarily rely on administrative and regulatory measures, including laws, regulations, and technical guidelines, to establish a binding institutional framework. Green industry development emphasizes market–based incentives, facilitating the conversion of ecological resources into productive economic assets. Government ecological performance evaluation provides long–term monitoring and accountability mechanisms to ensure effective implementation of ecological civilization policies. By coordinating government regulation and market incentives from the provincial level, the NECPZ provides a systemic approach to ecological governance and creates conditions conducive to raising rural residents’ income.

2.2. Theory and Hypothesis

2.2.1. Ecological Fiscal Support

According to the theory of externalities, when actors do not fully bear the benefits of public goods provision or the costs of environmental damage, under–provision and degradation arise. Pigou suggested that governments can internalize externalities through subsidies or taxes that either increase the benefits of provision or impose costs for damages [

22]. Ecological services, such as clean water and biodiversity, possess public goods attributes. To ensure their supply, governments provide financial compensation to areas rich in ecological resources where development rights are restricted. Under the NECPZ policy, fiscal support has increased, enabling individual farmers or village collectives—as owners or users of ecological resources—to receive various payments, including easement management compensation and public welfare forest compensation. Central and provincial governments channel these transfer payments to counties, which then expand fiscal expenditures to distribute a proportion of funds to local residents. As a result, rural residents in implemented areas gain higher income from government payments linked to ecological conservation compared with non-implemented regions.

2.2.2. Eco–Industry Development

Agriculture is considered a crucial pathway for development [

23] and a key pillar industry in rural economy in China. However, its primary products are often highly homogeneous and difficult for consumers to differentiate, limiting the growth of farmers’ income. According to industrial organization theory, product differentiation is an important strategy for firms to increase profits. In the agriculture sector, branding and certification have become common practices to differentiate products, enhance their added value, and thereby increase farmers’ income [

24,

25,

26,

27]. The NECPZ policy lays the ecological and technological foundation for high-quality, differentiated agricultural products’ development by improving overall ecological quality, creating mechanisms for promoting eco–industries, and encouraging the adoption of environmentally friendly agricultural technologies. These measures support higher agricultural product prices, drive quality improvement and efficiency gains in agriculture, and ultimately promote the rural residents’ income from business.

Ecotourism consists of one of the main eco-industries in China [

28]. The NECPZ policy supports enterprises in developing ecotourism in ecologically rich areas. First, clarifying ownership of natural resources expands the scope of tradable land, reducing costs for enterprises to obtain land use rights and integrate resources. Second, green finance support for ecological projects increases firms’ access to capital. Third, shifts in ecological performance evaluations and land use regulations guide governments to restrict high–pollution industries and support ecological industries, creating a favorable policy environment. According to the theory of agglomeration, industries with strong interconnections tend to cluster geographically to benefit from technology spillovers and achieve economies of scale. The development of ecotourism enhances regional visibility and attracts visitors, which, combined with the above conditions, incentivizes local farmers to engage in ecological entrepreneurship. Farmers can increase their income by operating homestays, establishing cooperatives. Empirical studies indicate that rural entrepreneurship and participation in economic organizations have positive effects on income growth [

29,

30].

2.2.3. Non-Agricultural Employment

Non-agricultural employment constitutes an important source of rural residents’ income [

31,

32,

33]. According to dual–sector economic theory, agricultural labor can increase earnings by transferring to higher-productivity non-agricultural sectors [

34]. The NECPZ policy promotes non-agricultural employment through two main channels. First, it increases non-agricultural job opportunities. Prior studies show that the NECPZ fosters green technological innovation by integrating environmental regulations with incentive mechanisms. Such innovation stimulates new industrial demand and accelerates industrial upgrading, particularly in the rapidly expanding tertiary sector, generating more employment opportunities for rural laborers with diverse skill levels [

35,

36]. Additionally, the NECPZ provides ecological jobs that directly employ rural residents. Second, the policy reduces the opportunity cost of non-agricultural employment. By promoting the establishment of natural resource property rights, farmers who own forestland or other ecological land but lack the capacity to manage it can lease or transfer their land, reducing land idling costs and encouraging them to seek employment off–farm [

37,

38].

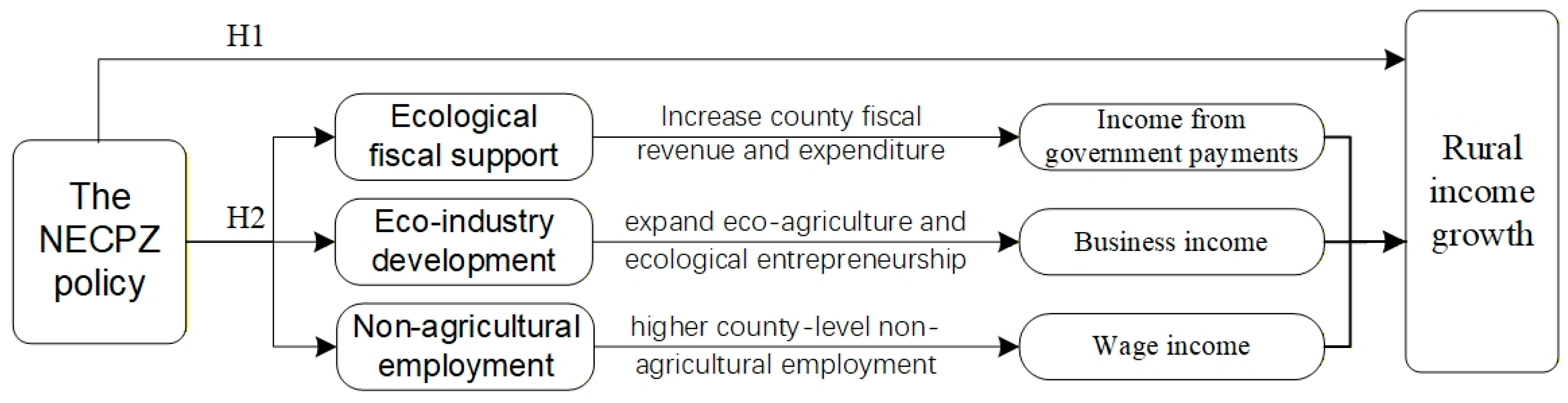

Based on the above analysis, this study develops a theoretical framework (see

Figure 2) and proposes the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1. The NECPZ policy has a positive effect on rural residents’ income.

Hypothesis 2. The NECPZ policy increases rural residents’ income through three channels: enhancing ecological fiscal support, promoting ecological industry development, and expanding non-agricultural employment.

3. Research Design

3.1. Sample Selection and Data

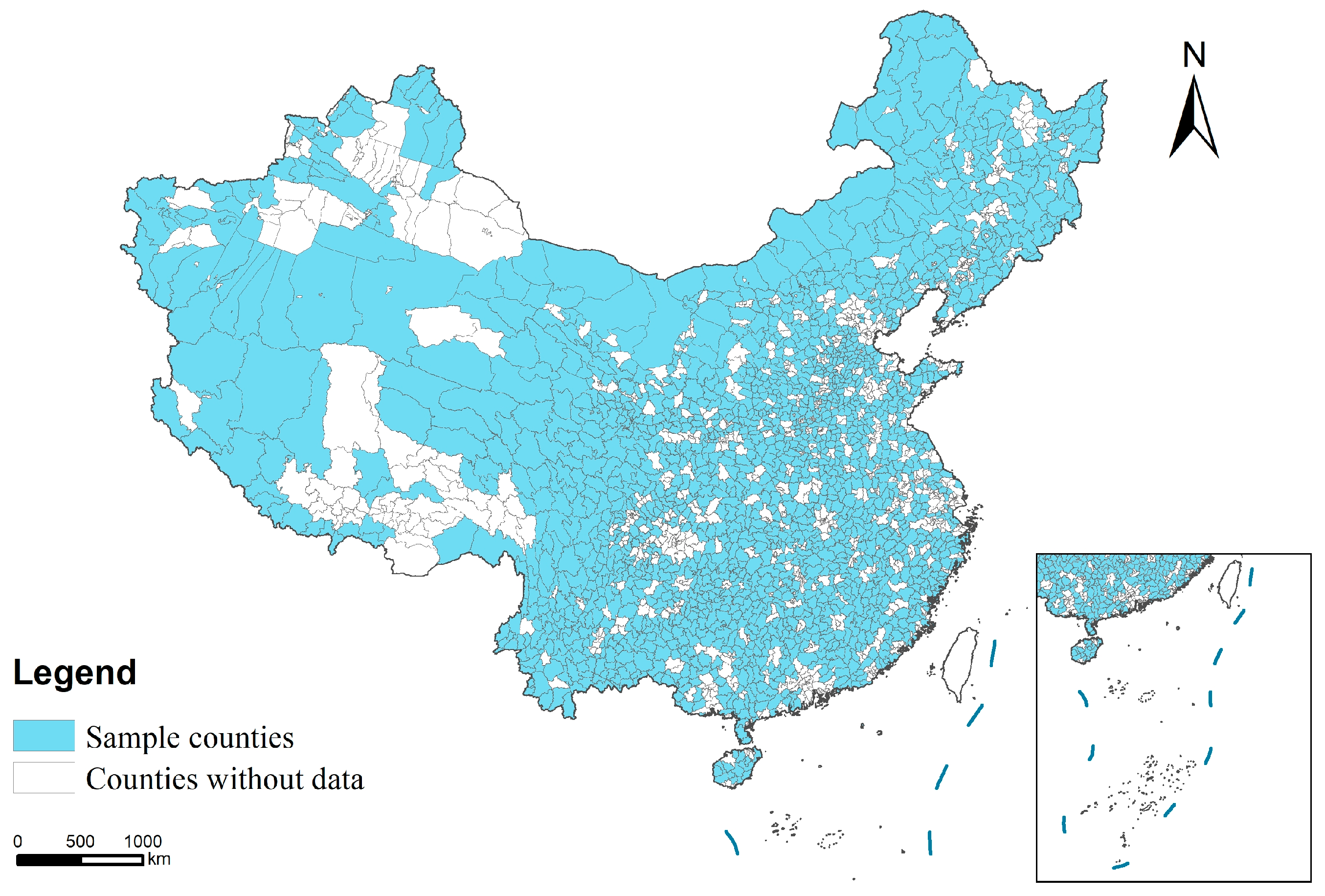

The NECPZ policy was implemented in 2016, 2017, and 2019. Considering data availability and the need to observe pre- and post–policy changes across most pilot regions, this study selected the period from 2010 to 2022 as the sample period. County names and administrative codes were standardized to 2022. Counties with severe data gaps or those rendered statistically inconsistent due to administrative divisions splitting or merging are excluded. Municipal districts were excluded due to significant characteristic differences compared to other counties. The final unbalanced panel dataset covers 1761 counties from 2010 to 2022, including 307 counties within NECPZ.

Figure 3 illustrates the spatial distribution of the 1761 sample counties across China. The sample counties are distributed across the eastern, central, and western regions, exhibiting a broad spatial coverage without noticeable concentration in any specific area. This distribution indicates that the sample is diverse in terms of geographic location and regional development stages, encompassing different types of counties, which helps enhance the representativeness of the research findings.

County–level rural residents’ income data are collected from provincial statistical yearbooks and the CEInet statistics database. GDP, administrative area size, fiscal expenditure, fiscal revenue, year–end population, number of regular secondary school students, year–end outstanding loan balance of financial institutions, and number of fixed–line telephone subscribers are sourced from the Statistical Yearbook of China’s Counties. Consumer Price Index (CPI) data is sourced from the Express Professional Superior (EPS) database. Data on farmer cooperatives are sourced from the Tianyancha website. The number of agricultural products of geographical indication is sourced from the China Academy for Rural Development–Qiyan China Agri-research Database (CCAD) and the China Green Food Development Center website. The proportion of cropland is calculated using the China Land Cover Dataset (CLCD) [

39], while the relief degree of land surface data came from the China Relief Degree of Land Surface Kilometer Grid Dataset [

40]. The average nighttime light intensity is derived from Improved Time–Series DMSP–OLS–Like Data [

41]. Provincial employment figures for the secondary and tertiary industries are obtained from the China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database. Newly established enterprises in secondary and tertiary industries are sourced from the National Enterprise Credit Information Publicity System. The list of counties covered by the NECPZ is derived from the NECPZ Implementation Plan and the Ministry of Civil Affairs’ 2022 administrative division. The list of impoverished counties is from directories of the 832 concentrated contiguous counties with special difficulties and national key counties for poverty alleviation and development issued by the State Council Poverty Alleviation Office, combined with the county exit lists for 2014, 2015, and 2016.

3.2. Model Construction

Treating the NECPZ policy as a quasi–experiment, this study employs a staggered difference–in–difference approach to analyze the impact of the NECPZ policy on rural residents’ income, leveraging the temporal differences in the implementation plans’ release dates. Counties covered by the NECPZ policy serve as the treatment group, while uncovered counties form the control group. Differences between the treatment and control groups before and after policy implementation are compared. The staggered difference–in–difference model is constructed as follows:

In Equation (1), is the constant parameter. is the logarithm of the income of rural residents in county in year ; is the NECPZ policy implementation dummy variable; includes a series of control variables, which are described below; is county–level fixed effect; is year–level fixed effect; and is random error term. The DID method avoids to some extent the omitted variables in the endogeneity problem. We focus on the coefficient . If is significantly greater than 0, this indicates that the NECPZ can positively affect rural residents’ income.

Furthermore, this study employs the following equation to examine the policy impact mechanism.

In Equation (2), represents the mechanism variables. Other variables’ definitions are the same as in Equation (1).

3.3. Variables

3.3.1. Explained Variables

Drawing on existing studies, we use the logarithm of the net income per capita of farmers and the disposable income per capita of rural residents (lnRI) as the explanatory variable (net income per capita of farmers before the reform of the Urban and Rural Household Survey and disposable income per capita of rural residents after the reform). The reform was implemented in 2013, and the change in its scope is considered minor and could be absorbed by fixed effects [

42]. All income figures are deflated using the CPI of the respective province to eliminate monetary price effects.

3.3.2. Core Explanatory Variables

Dummy variables (TreatPost) are constructed as core explanatory variables using policy implementation time and coverage area. Counties covered by NECPZ constitute the treatment group, while uncovered counties are set as the control group. Treated counties take the value 1 during the implementation year and all subsequent years, and 0 otherwise. All control group counties consistently take the value 0.

3.3.3. Control Variables

Drawing on the research of Li et al., 2021 [

43], Lin et al., 2023 [

44] and other related studies, this study first incorporates several control variables to account for other factors affecting rural residents’ income, including government fiscal self–sufficiency (GOV), education level (EDU), urbanization level (URBAN), financial development (FIN), and communication infrastructure (INFAR). Government fiscal self–sufficiency impacts the intensity of policy implementation [

45]. Education improves farmers’ human capital and thus their income [

46,

47]. Urbanization promotes the transfer of surplus rural labor into urban sectors with higher productivity and wages [

48]. Financial development influences rural residents’ income by providing financial services and improving capital flows [

49,

50]. Communication infrastructure reflects the level of local infrastructure development, which enhances resource allocation efficiency and supports income growth [

51,

52].

In addition, pre–existing differences between treated and control counties may lead to divergent development trends. Drawing on Li et al., 2016 [

53], an interaction term between minority autonomous counties and a time trend (t_AUTO) is added to control for minority–related policies. An interaction term between counties located along provincial administrative borders and a time trend (t_BORDER) is included to account for the effects of administrative and policy marginalization arising from geographic marginalization. In general, the NECPZ counties have favorable ecological endowments but lag in socioeconomic modernization, making ecological transition more attainable [

54]. This study includes interaction terms between a time trend and variables representing natural and economic conditions to control for these baseline differences. The natural–condition variables include the normalized difference vegetation index (t_NDVI) and the relief degree of land surface (t_RDLS) in the base year (2016). The NDVI reflects vegetation coverage, while the relief degree of the land surface captures geographic constraints. Areas with higher vegetation coverage and more rugged terrain tend to be less disturbed by human activity and possess stronger ecological foundations. The economic–condition variables include an indicator for whether a county remained on the national poverty list in the base year (t_poorCO) and the log of per capita GDP in the base year (t_lnGDP).

3.3.4. Mechanism Variables

Based on the preceding analysis, relevant literature, and data availability, this study selects mechanism variables to examine three pathways through which policies in the pilot region affect farmers’ income levels. The fiscal subsidy pathway involves variables including government fiscal expenditure (EXP) and government fiscal revenue (REV). The ecological industry development pathway involves variables including the number of agricultural products of geographical indication (GI) and the number of farmers’ cooperatives participating in ecological agriculture and ecotourism (COOP). The non-agricultural employment pathway involves the logarithm of the number of employees in the secondary and tertiary industries (EMPL). The presence of ecological agricultural and ecotourism operations in farmers’ cooperatives is determined by whether their business scope includes keywords for ecological agriculture and ecotourism. Due to extensive data gaps in secondary and tertiary sector employment figures spanning multiple years before and after the study period, this paper adopts an approach proposed by Bartik, 1991 [

55]. Employment figures for these sectors at the county level are derived by multiplying provincial employment data by the proportion of newly established enterprises in the county’s secondary and tertiary sectors relative to the province’s total new enterprises in those sectors.

Descriptive statistics for the main variables in this study are presented in

Table 2.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Benchmark Regression

Columns (1)–(2) in

Table 3 report the regression results without and with control variables. The coefficient of TreatPost remains consistently positive and statistically significant, unequivocally suggesting that the NECPZ has a positive effect on rural residents’ income. The estimation results in column (2) serve as this study’s baseline regression for analysis. Column (2) shows that the policy contributes to a 2.37% higher income for rural residents in participating counties relative to non–implementing counties, providing empirical support for H1.

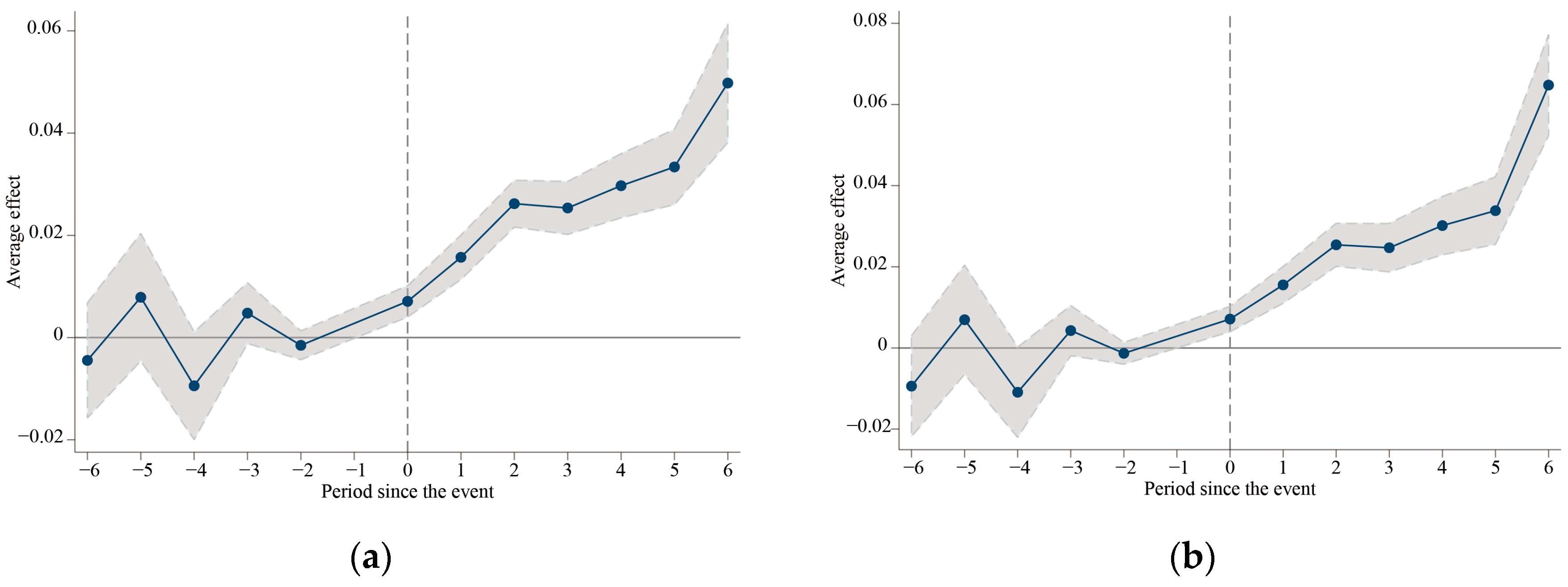

4.2. Parallel Trend Test

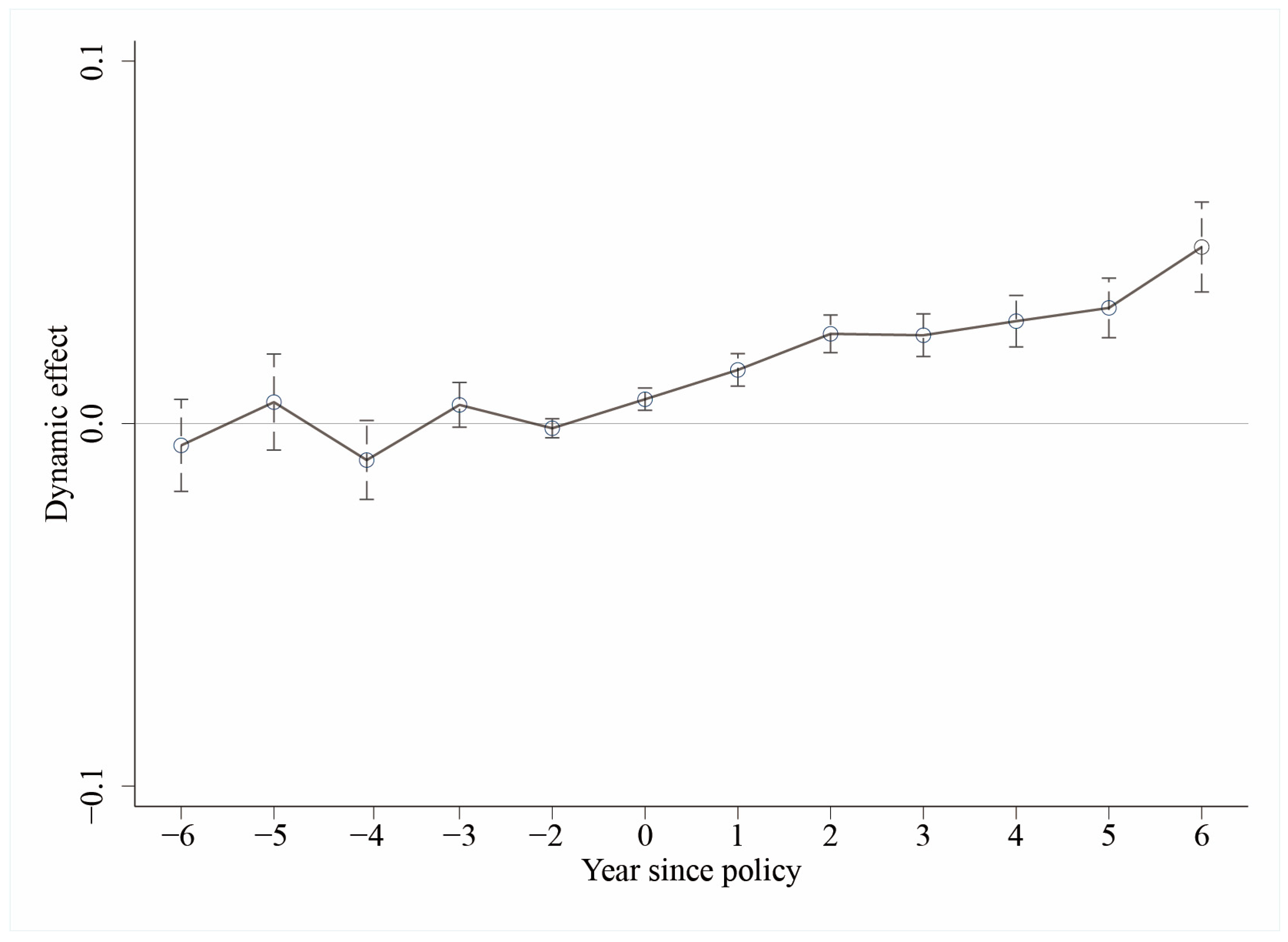

The parallel trends assumption is a prerequisite for the validity of the difference–in–differences method, requiring that the pre–policy trends of the treatment and control groups do not exhibit significant differences. Since the NECPZ policy was implemented at three different time points, this study employs an event–study approach to test the parallel trends assumption.

denotes the dummy variable in the kth year before or after the implementation of NECPZ policy. This study uses 2010–2022 data, and the policy implementation times are 2016, 2017, and 2019. The values before 6 periods of policy implementation are grouped into—6 periods, and the previous year of policy implementation (—1 period) is used as the base period. The resulting regression coefficients with 95% confidence intervals are presented in

Figure 4. It can be seen that before the policy implementation, the regression coefficients are not significantly different from zero, indicating no systematic differences between the treatment and control groups, thus confirming that the two groups satisfy the parallel trends assumption. Post–implementation coefficients show a significant and sustained increase in rural residents’ income for the treatment group relative to the control group, demonstrating the NECPZ’s persistent positive effect on rural residents’ income. In the initial phase following policy implementation, the estimated coefficients are relatively small. Subsequently, the policy’s impact gradually intensified. This persistence may be related to the fact that the NECPZ is a policy framework characterized by long–term institutional arrangements and sustained fiscal support. Even after the initial implementation phase, the construction of national ecological civilization pilot zones has continued to be emphasized in subsequent policy agendas, accompanied by ongoing fiscal transfers.

4.3. Robustness Test

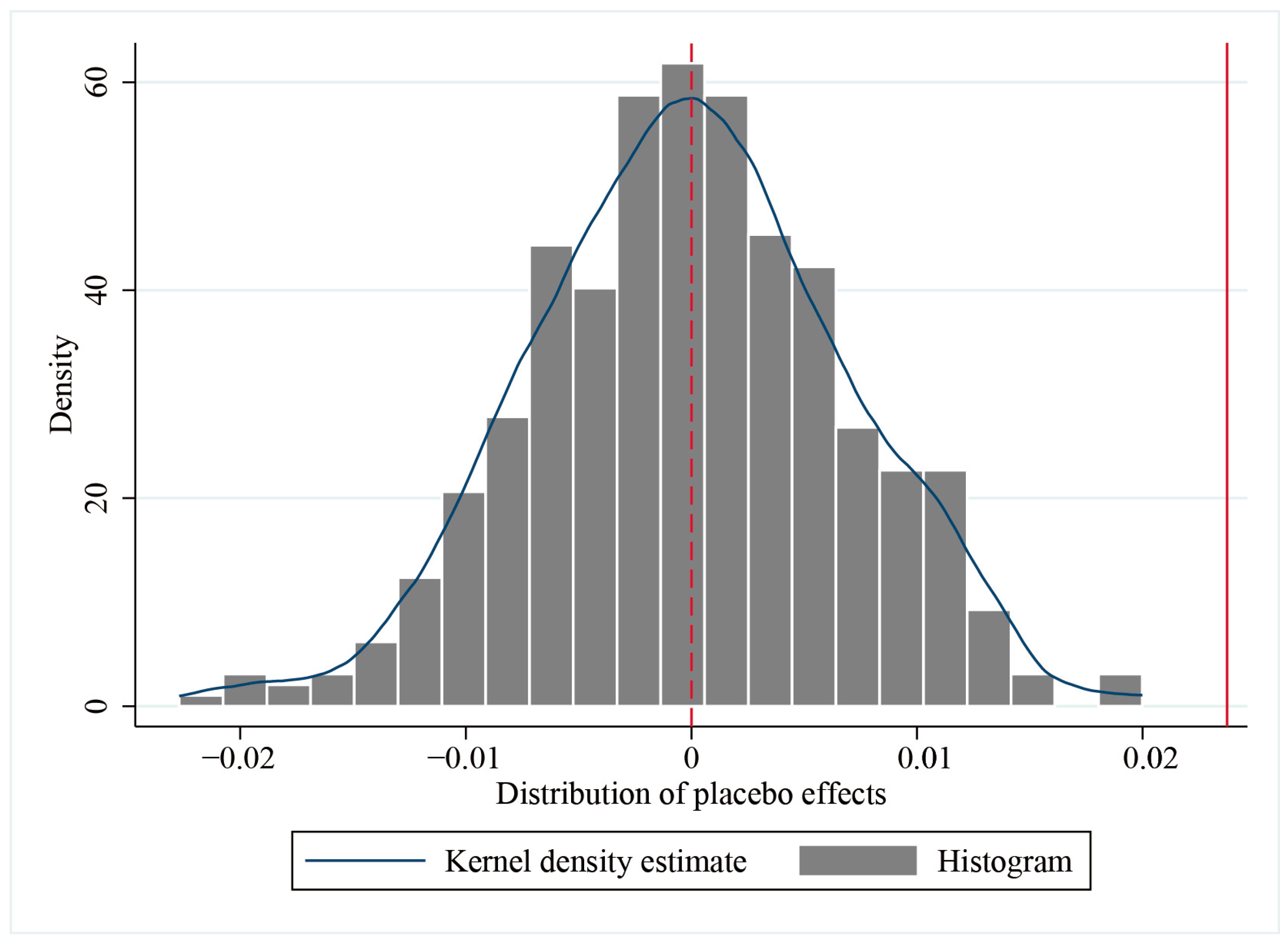

4.3.1. Placebo Test

Although the model includes region fixed effects to control for time–invariant factors at the regional level, it may still be affected by other unobserved time–varying confounding factors. To mitigate this concern, following Chen et al., 2023 [

56], a placebo test was conducted by randomly assigning fake policy implementation times and fake treated regions and estimating the coefficients.

Figure 5 presents the distribution of placebo effects obtained from 500 repetitions of two–way fixed effects estimations with randomly assigned treatment. Most estimated coefficients cluster around zero, and the distribution is approximately normal, indicating that the expected value of the placebo effect under the model is zero. The actual estimated treatment effect of the NECPZ policy (represented by the vertical solid line) lies at the extreme right end of the placebo distribution, suggesting it is an outlier. The placebo test supports the hypothesis that the NECPZ policy increases rural residents’ income, indicating that the observed effect is not driven by random factors.

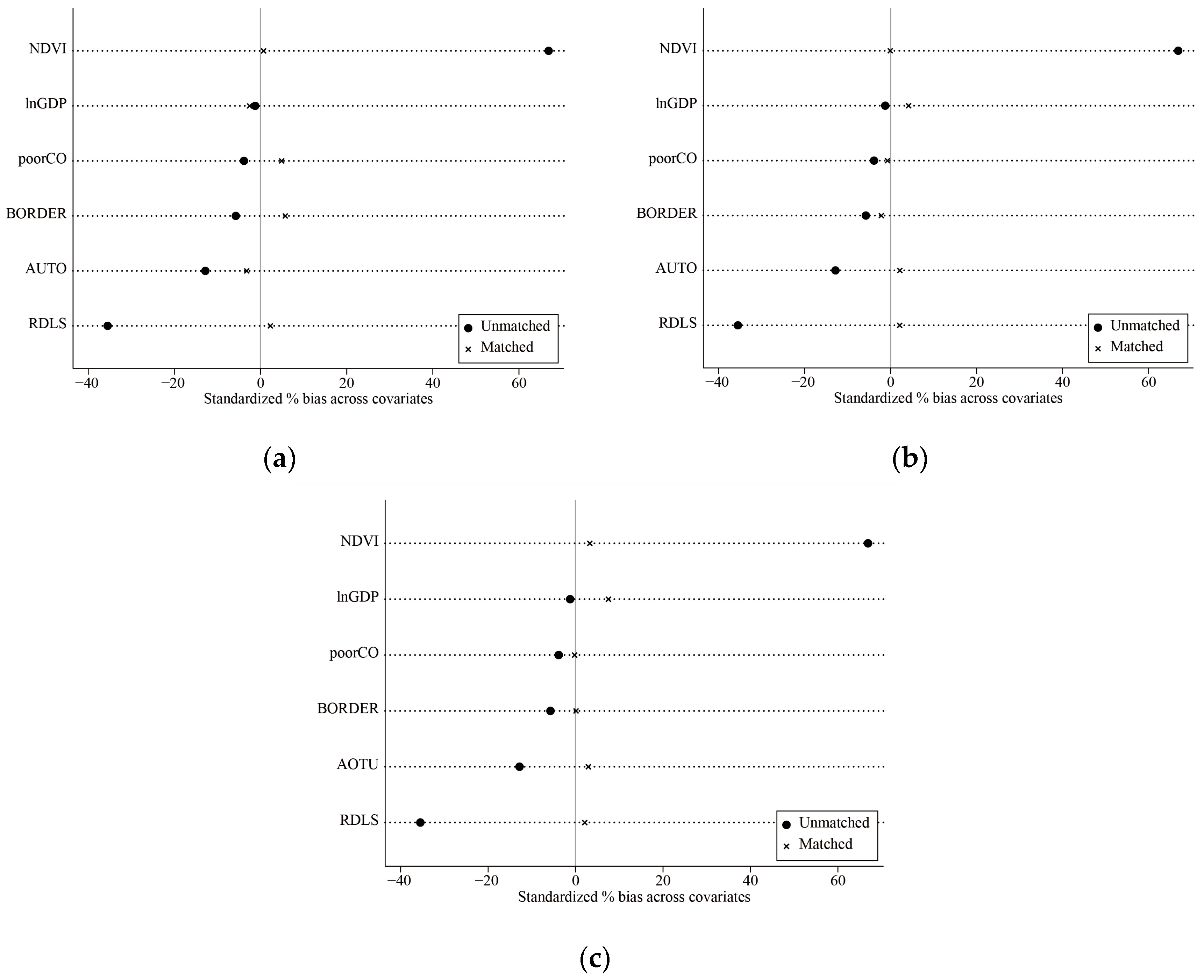

4.3.2. PSM–DID

To address potential endogeneity arising from observable variables, this study further employs the propensity score matching difference–in–differences (PSM–DID) approach to estimate the policy effect. First, this study uses the baseline–condition control variables as covariates to match the control group using 1:1 and 1:4 nearest–neighbor matching, as well as kernel matching. After matching, the absolute values of standardized differences in covariates between the treatment and control groups are all below 10%, indicating no systematic differences and validating the reliability of the matching method and covariates (see

Figure 6). Subsequently, Equation (1) is used to estimate the effect of the policy on rural residents’ income.

Table 4 presents the PSM–DID estimation results, which are similar to the baseline regression, demonstrating the robustness of the NECPZ’s income–enhancing effect on rural residents.

4.3.3. Heterogeneous Treatment Effect Tests

Staggered DID may have heterogeneous treatment effects. The same treatment produces differences in effects for different individuals, which may be manifested in the two dimensions of the length of time since receiving the treatment or the group receiving the treatment at different time points, and the heterogeneous treatment effects lead to biased results in the weighted average treatment estimates [

57]. Therefore, we adopt the stacked estimator proposed by Cengiz et al., 2019 [

58] and the group–time average treatment effect estimator developed by Sun and Abraham, 2020 [

59] to re–estimate the impact of the NECPZ policy on rural residents’ income (see

Table 5), and we plot the adjusted dynamic treatment effects after mitigating heterogeneity concerns. As shown in

Table 5, the coefficients of the core explanatory variable remain significantly positive.

Figure 7 further indicates that, although the magnitude and significance of the estimates change after accounting for treatment–effect heterogeneity, the overall pattern remains consistent with the baseline results. This confirms the robustness of the study’s conclusions.

4.4. Other Robustness Tests

First, replace the dependent variable: To further verify the robustness of the results, this study uses the growth rate of rural residents’ income as the dependent variable to estimate the effect of the NECPZ policy. Column (1) in

Table 6 shows that after including county and year fixed effects along with control variables, the coefficient of the core explanatory variable remains positive and statistically significant at the 5% level, further confirming the robustness of the findings.

Second, perform Winsorization: To eliminate the potential influence of extreme values on the estimates, all continuous variables in the model are Winsorized at the 1% level, and the regressions are re–run. Column (2) in

Table 6 presents the results. The coefficient of the core explanatory variable remains positive and statistically significant at the 1% level, consistent with the baseline regression, confirming the reliability of the findings.

Third, exclude pilot regions with short implementation periods: The Hainan pilot zone was established in 2019, and its short implementation period may not fully reflect the policy effects, potentially affecting the estimates. Column (3) in

Table 6 shows the results after excluding it. The core explanatory variable remains significant, with a coefficient slightly higher than the baseline, further supporting the robustness of the conclusions.

Fourth, control for high–dimensional fixed effects: To further account for unobserved factors, interactions between region types (eastern, central, western) and year fixed effects are added to the model. Column (4) in

Table 6 shows that the core explanatory variable remains positive and statistically significant at the 1% level.

Fifth, control for the impact of other concurrent policies: During the implementation of the NECPZ policy, other simultaneously implemented policies may also have influenced rural residents’ income. This study additionally considers three concurrent policies. First, the Two Mountains Practice Innovation Bases. From 2017 to 2023, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment successively established seven batches of these bases, covering six prefecture–level cities, 186 county–level units, and various township forest farms. Regions selected as bases need to have environmental protection foundations and achieve effectiveness in the ecological–economic transformation in some respects, which may have affected rural residents’ income [

60]. Second, the National Key Ecological Function Zone (NKEFZ) policy. To protect the environment and maintain ecological security, the central government designated National Key Ecological Function Zones starting in 2010 and expanded their coverage in 2016. Counties within these zones receive increased transfer payments due to ecological conservation and development restrictions, potentially impacting rural residents’ income [

61]. Third, the pilot policy supports rural migrant workers’ return to their hometowns for entrepreneurship. Migrant workers who have accumulated wealth and knowledge in cities may enhance local incomes by creating jobs and other means upon returning. In February and December 2016 and October 2017, the government announced three batches of pilot regions for this policy [

62]. This study constructs dummy variables using the timing and locations of these three policies and incorporates them into the model. The results, shown in columns (5), (6), and (7) of

Table 6, indicate that the core explanatory variables remain significant at the 1% level, with only minor differences from the benchmark regression. This further mitigates concerns about the influence of concurrent policies and confirms the robustness of the findings.

4.5. Analysis of Mechanisms

Initially, we examine the ecological fiscal support channel. After the NECPZ policy was implemented, the central and provincial governments increased ecological compensation funds. County governments receiving these transfers increased expenditures, channeling funds to rural residents. Due to data limitations, direct information on rural residents’ income from these transfers is unavailable. However, since the transfer payments to rural residents constitute part of the ecological transfer payments, we examine the effect of policy implementation on county–level use of ecological compensation funds to infer its impact on the transfer income of rural residents. First, we test whether county–level fiscal revenue and expenditure increased after the NECPZ policy. Columns (1)–(2) in

Table 7 show that, compared with non–pilot counties, counties within pilot zones exhibit significantly higher fiscal expenditures at the 5% level. In contrast, the coefficient for fiscal revenues is positive but not statistically significant. This may be due to the inclusion of poverty–alleviation funds in county–level transfers, which are distributed to both treated and control counties, thereby reducing observable differences in fiscal revenues between the two groups. To address this, counties that had not exited poverty by 2016 were excluded, and the regressions are re-estimated. Columns (3)–(4) in

Table 7 indicate that, relative to non–pilot counties, fiscal expenditures in pilot counties are higher and significant at the 1% level, while fiscal revenues are also higher and significant at the 5% level. Overall, these results suggest that the NECPZ policy substantially increases fiscal support to counties, promotes higher county–level expenditures, and likely enhances the transfer payments received by rural households.

Next, we examine the eco–industry development channel. This paper examines this channel from two aspects. First, the NECPZ policy improves agricultural production conditions and promotes ecological agriculture, laying the foundation for product branding and differentiation, which, in turn, enhances farmers’ income. The number of agricultural products of newly registered geographical indications is used as a proxy for the development of ecological agriculture. Geographical indication branding increases product uniqueness and competitiveness. Since GIs typically cover a specific geographic area, farmers engaged in agricultural production within that area gain additional income opportunities [

63]. Column (5) in

Table 7 shows that the NECPZ policy significantly increases the number of GI products, supporting the mechanism that ecological agriculture development promotes rural residents’ income. Second, the NECPZ policy encourages farmers to engage in ecological entrepreneurship, particularly in ecological agriculture and ecotourism. The number of farmer cooperatives operating in these sectors serves as a proxy for ecological entrepreneurship. Column (6) in

Table 7 indicates that pilot counties have more ecological agriculture and eco–tourism cooperatives than non–pilot counties. Previous studies show that farmer cooperatives enhance human capital and asset accumulation, thereby facilitating income growth [

64]. Together, these results suggest that the NECPZ policy promotes rural residents’ income by fostering eco–industry development through both improved agricultural conditions and ecological entrepreneurship.

Finally, we examine the non–agricultural employment channel. This study uses the logarithm of employment in the secondary and tertiary sectors as a proxy for non–agricultural employment. The results in column (7) of

Table 7 show that the NECPZ policy significantly expanded the scale of non–agricultural employment. In general, the marginal returns in non–agricultural sectors are higher than in agriculture, so an increase in non–agricultural employment typically leads to higher rural residents’ income [

65]. The NECPZ policy promotes eco–industry development at the county level, creating more local employment opportunities for rural residents and thereby boosting their income. Therefore, the policy effectively increases rural residents’ income by promoting non–agricultural employment. Taken together, Hypothesis 2 is supported.

4.6. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.6.1. Regional Heterogeneity Analysis

Due to significant disparities in natural environments and socioeconomic conditions between China’s eastern and central–western regions, the implementation outcomes of NECPZ may vary across regions. This study employs group regression analysis to examine these differences. As shown in columns (1) and (2) of

Table 8, the inter-group coefficient difference is significant at the 1% level. In the eastern regions, the policy effect on rural residents’ income is significantly negative, whereas in the central–western regions, the effect is significantly positive, indicating the presence of regional heterogeneity in policy impacts. This may be because the eastern regions, being more economically developed, already provide rural residents with multiple income-generating avenues, limiting the marginal income-increasing effect of the NECPZ policy relative to other eastern areas. In contrast, in the central–western regions, the institutional safeguards and financial support offered by the pilot zones improve resource allocation efficiency and broaden income channels, resulting in higher marginal effects on rural income growth.

4.6.2. Analysis of Heterogeneity by the Rural Residents’ Income Level

Although the NECPZ policy promotes increases in rural residents’ income overall, its impact may differ across regions with different income levels. Using the median income in the policy’s baseline year as the cutoff, this study divides counties into high–income and low–income groups and conducts subgroup regressions based on Model (1). The results are reported in columns (3) and (4) of

Table 8. The policy has a significantly positive income–enhancing effect in both groups, and the coefficient difference test is significant at the 5% level. Comparing the two coefficients reveals that the policy is more effective in regions with lower farmer income levels. This indicates that the NECPZ policy not only raises rural residents’ income levels but also helps reduce income inequality.

4.6.3. Analysis of Heterogeneity by Agricultural Endowments

Agriculture plays a central role in rural economies, and the development of ecological agriculture is closely linked to improvements in rural residents’ income. Given that cropland is a key agricultural endowment [

66,

67], this study uses the share of cropland as a proxy. Counties are divided into high– and low–endowment groups based on the median cropland share in the baseline year, and subgroup regressions are conducted using Model (1). Columns (5)–(6) of

Table 8 report the results, showing that both the core explanatory variable and the coefficient difference between the groups are significant at the 1% level. The findings indicate that the income–enhancing effect of the NECPZ policy is more pronounced in areas with stronger agricultural endowments. This result is consistent with the earlier mechanism analysis, which suggests that the NECPZ policy promotes ecological agriculture and thereby increases rural residents’ income. Specifically, after the establishment of the NECPZ, the promotion of agricultural ecological transformation helps activate and optimize the use of underutilized resources, such as land and agricultural machinery, in high–endowment areas, strengthening the scale effects of ecological agriculture and significantly improving rural residents’ income levels.

4.6.4. Analysis of Heterogeneity by Local Fiscal Self–Sufficiency

Lower fiscal self–sufficiency implies greater reliance on intergovernmental transfers, with a larger share of general public budget expenditures used to maintain basic government operations. This not only limits the provision of public services but also weakens the ability to finance development projects. Although transfers provide financial support, their zero–cost nature and the discretionary allocation of earmarked transfers reduce their efficiency relative to locally generated revenue [

68]. Therefore, regions with higher fiscal self–sufficiency are likely to achieve better policy outcomes. The study measures fiscal self–sufficiency using the ratio of government fiscal revenue to fiscal expenditure. Counties are grouped into high– and low–capacity regions based on the median fiscal self–sufficiency ratio in the baseline year, and subgroup regressions are conducted using Equation (1). The results in columns (7)–(8) of

Table 8 show that the core explanatory variables are significant at the 1% level, and the coefficient difference between groups is significant at the 5% level. Comparing coefficients reveals that the policy’s income–enhancing effect is more substantial in counties with higher fiscal self–sufficiency.

4.6.5. Analysis of Heterogeneity by Entrepreneurial Dynamism

Regions with higher entrepreneurial dynamism typically possess broader capital access, necessary technological resources, and favorable policy environments, enabling them to attract more start–ups, create employment, and ultimately raise income levels [

69,

70]. Based on this study’s mechanism analysis, whereby the NECPZ policy promotes rural residents’ income by stimulating ecological entrepreneurship, areas with stronger entrepreneurial dynamism are expected to experience greater policy effects. This study measures entrepreneurial dynamism using the number of newly registered enterprises in each county. Counties are divided into high– and low–dynamism groups according to the median number of new firms, and regressions are conducted using Equation (1). The results shown in columns (9)–(10) of

Table 8 indicate that the core explanatory variable is significantly positive at the 5% level in low–dynamism regions, while in high–dynamism regions, the coefficient is larger and significant at the 1% level. The coefficient difference is also significant at the 1% level, suggesting that the NECPZ policy exhibits a stronger income–enhancing effect in regions with greater entrepreneurial dynamism.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study provide empirical evidence for the continued advancement and refinement of the NECPZ policy. Baseline results indicate that the NECPZ policy significantly increases rural residents’ income, and that this effect persists after policy implementation. This persistence reflects the fact that the NECPZ policy is not a short-term intervention but a comprehensive policy characterized by long-term institutional arrangements and sustained investment. As policy implementation progresses, early exploratory efforts gradually evolve into more rational institutional designs and improved implementation efficiency, facilitating the realization of policy outcomes. Simultaneously, by jointly pursuing environmental protection and economic development, the NECPZ policy coordinates ecological conservation with rural residents’ income, thereby supporting sustained income growth.

Mechanism analysis reveals that increasing ecological fiscal support, promoting eco-industry development, and expanding non-agricultural employment are key pathways through which the NECPZ policy enhances rural residents’ income. Specifically, counties implementing the NECPZ policy are more conducive to increasing rural residents’ income from government payments compared with non-implementing counties. While existing research has discussed the significance of industrial development for farmers’ income [

71], this study focuses primarily on ecological industry development, particularly entrepreneurial activities in the ecological sector and the development of ecological agriculture. Entrepreneurial activities contribute to rural industrial revitalization and income diversification among rural residents. By improving environmental quality, enhancing agricultural product quality, and thereby promoting geographical indication branding, the policy supports income growth. Additionally, non-agricultural employment, a crucial income channel for rural residents [

72], is reinforced during the NECPZ policy implementation. Given regional disparities in development conditions, these mechanisms do not operate uniformly across regions. Nevertheless, as a comprehensive policy, the NECPZ can synergistically leverage multiple channels to provide diverse pathways for rural income growth, thereby elevating overall rural income levels.

Heterogeneity analysis indicates that the NECPZ policy significantly promotes rural income in central and western regions, while showing no positive effect in eastern regions. Central and western regions, with relatively weaker developmental foundations, benefit more from the policy’s institutional supports and resource inputs, resulting in more pronounced income effects. In contrast, eastern regions possess more developed industrial bases and may face structural adjustment pressures during policy implementation. Additionally, their relatively superior economic development, human capital, and infrastructure conditions, coupled with more diversified income sources available to rural residents, may limit the policy’s marginal income-enhancing effect relative to existing income pathways. Other heterogeneity analyses based on different development conditions generally reveal positive impacts of the NECPZ policy, though the magnitude of these effects varies. The policy exerts stronger impacts in areas with lower initial income levels among rural residents, higher agricultural endowments, greater fiscal self-sufficiency, and stronger entrepreneurial dynamism. These findings indicate that the NECPZ policy can further leverage regional resource endowments and other advantages, underscoring the importance of tailoring policy implementation to local contexts in order to fully unlock its potential.

6. Conclusions and Policy Implications

Using county–level panel data from 2010 to 2022, this study employs a staggered difference–in–differences model to examine the impact of the NECPZ policy on rural residents’ income. We decompose rural residents’ income into income from government payments, business income, and wage income to analyze how the policy affects each and, in turn, the overall income levels. We also investigate how the policy’s effects vary across regions with different development conditions. The results show that the NECPZ policy significantly increases rural residents’ income, and this finding remains robust after a series of tests, including placebo tests, heterogeneous treatment effect estimations, and controls for other concurrent policies. Mechanism analysis indicates that the policy raises rural residents’ income by increasing ecological fiscal support, promoting eco–industry development, and expanding non-agricultural employment opportunities. The heterogeneity analysis further demonstrates that the policy has stronger effects in areas with lower initial income levels, highlighting its potential to reduce rural residents’ income inequality. The policy increased rural residents’ income in the central–western regions, while showing no positive effects in the eastern regions. Moreover, the policy performs better in areas with greater agricultural endowments, better fiscal self–sufficiency, and higher entrepreneurial dynamism.

From the perspective of promoting rural residents’ income, the findings of this study highlight the importance of implementing comprehensive ecological and environmental policies. For some single ecological compensation programs, the compensation amount fails to fully offset farmers’ opportunity costs [

73], meaning that income improvement depends more on farmers diversifying their livelihoods, for example, through non-agricultural employment. Ecological protection measures that do not sufficiently account for the interests of rural residents are unlikely to secure sustained grassroots support, thereby undermining the achievement of conservation goals [

74]. In contrast, the NECPZ, by setting multiple policy objectives, integrating diverse policy instruments, and relying on provincial–level coordination, provides support for rural residents through multiple income pathways, including subsidies, agricultural operations, entrepreneurial activities, and non-agricultural employment. The heterogeneity results further show that the NECPZ generates additional benefits on top of existing regional development conditions, revealing the potential of comprehensive policies to promote rural residents’ income growth while maintaining ecological protection.

Based on the findings of this study, the following policy recommendations are proposed to strengthen future implementation.

First, the government should continue refining the policy through pilot exploration and quality enhancement. During the initial implementation phase, emphasis should be placed on pilot exploration, focusing on institutional innovation and the accumulation of practical experience. In later stages, the focus should shift toward improving efficiency, promoting the standardized adoption of proven practices, and enhancing implementation effectiveness. The coordinating role of provincial governments should be strengthened to reduce implementation frictions and advance policies toward comprehensive objectives. County governments should leverage their capacity for policy execution and practical innovation, refining support measures based on local ecological endowments, industrial structures, and fiscal capabilities. Innovative implementation approaches should ensure effective linkages between policy execution and the growth of rural residents’ income, fostering sustainable grassroots models. At the regional level, pilot experiences in ecological civilization construction should be prioritized for replication in central–western regions and low-income areas. In eastern regions, efforts should focus on leveraging advantages in information, talent, and transportation to explore innovative pathways for the protective utilization of ecological resources, thereby expanding income growth opportunities for rural residents.

Second, governments should implement targeted policies centered on rural residents’ income growth pathways and grounded in local characteristics and strengths. To strengthen these pathways, fiscal compensation mechanisms should be improved, ecological compensation standards appropriately raised, and rural residents’ participation incentives enhanced. This will foster a virtuous cycle in which ecological conservation and income growth are closely integrated. Pathways should be explored to integrate ecological resources with capital, technology, and other production factors. Industrial funding subsidies should be increased, and priority should be given to green technologies. Support should be extended to the development of regional specialty brands, while barriers to entrepreneurship and operational costs for farmers should be lowered. Farmer cooperatives should be encouraged to partner with enterprises, enabling rural residents to capture greater value within the supply chain. Differentiated policy implementation requires greater financial support tilted toward regions with weaker fiscal capacity. This involves optimizing the allocation of transfer payments, improving fund utilization efficiency, prioritizing support for industrial development and infrastructure construction, enhancing local economies’ self-sustaining capabilities, and further strengthening policy effectiveness. For areas with favorable agricultural endowments, support should be provided for eco-agricultural industrial integration projects to build high-value-added industrial systems. For areas with strong entrepreneurial vitality, efforts should concentrate on promoting green financial support and fostering a favorable business environment to stimulate innovation among enterprises and rural residents.

7. Limitations and Future Research Prospects

This study utilizes county-level panel data to examine the impact of the NECPZ policy on rural residents’ income. However, several limitations remain. County-level data cannot fully capture micro-level variations in individual income, which may obscure more nuanced policy effects. The limited availability of county-level indicators constrains in-depth research into policy mechanisms. Future research may expand in the following directions. First, integrating household survey data and other multi-source datasets could capture micro-level policy effects. Second, developing diverse monitoring data could provide foundations for policy research. Third, the long-term impacts of NECPZ policy could be examined, and its specific pathways of action across different regions could be explored. Finally, conducting cross-country comparative studies of similar environmental policies could provide contextual references for NECPZ implementation and offer insights for designing integrated ecological policies in other developing countries.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.Z.; methodology, X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang); software, X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang); validation, X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang), Y.Y. and L.Z.; formal analysis, X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang) and Y.Y.; investigation, X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang); resources, L.Z. and X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang); data curation, X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang) and X.C. (Xiang Chen); writing—original draft preparation, X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang), Y.Y. and W.C.; writing—review and editing, X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang), Y.Y., L.Z., H.W. and W.C.; visualization, X.C. (Xiaoqing Chang), H.W. and L.Z.; supervision, L.Z.; project administration, L.Z.; funding acquisition, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 23BTJ030.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are included in the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to Hongyun Huang and Yuanbo Qiao for their constructive suggestions and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alvaredo, F.; Gasparini, L. Recent trends in inequality and poverty in developing countries. In Handbook of Income Distribution; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; Volume 2, pp. 697–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, M.; Jiang, F.; Wang, J.; Wu, B. Population ageing and income inequality in rural China: An 18-year analysis. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2024, 11, 1605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, M. Urbanization can help reduce income inequality. npj Urban Sustain. 2022, 2, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, Y.B.; Lee, C.C. Financial development, income inequality, and country risk. J. Int. Money Financ. 2019, 93, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Yahong, W.; Zeeshan, A. Impact of poverty and income inequality on the ecological footprint in Asian developing economies: Assessment of Sustainable Development Goals. Energy Rep. 2022, 8, 670–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, G.; Hu, X.; Liu, W. China’s poverty reduction miracle and relative poverty: Focusing on the roles of growth and inequality. China Econ. Rev. 2021, 68, 101643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Jiang, L. Urbanization forces driving rural urban income disparity: Evidence from metropolitan areas in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 312, 127748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Wang, L.; Ma, P.; Wang, W. Urban–rural income gap and air pollution: A stumbling block or stepping stone. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 94, 106758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.W.; Liu, T.Y.; Chang, H.L.; Jiang, X.Z. Is urbanization narrowing the urban-rural income gap? A cross-regional study of China. Habitat Int. 2015, 48, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piketty, T.; Yang, L.; Zucman, G. Capital accumulation, private property, and rising inequality in China, 1978–2015. Am. Econ. Rev. 2019, 109, 2469–2496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, L.; Liu, M.; Ji, T.; Wu, X.; Li, Y. Design reflections on the integrated development of rural cultural and ecological resources in China. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Commun. 2025, 12, 1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, H.; Liu, Y.; Lee, C.C. How does judicial quality in ecological governance affect income gap between urban and rural residents. Cities 2025, 161, 105929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milder, J.C.; Scherr, S.J.; Brace, C. Trends and Future Potential of Payment for Ecosystem Services to Alleviate Rural Poverty in Developing Countries. Ecol. Soc. 2010, 15, 4. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/26268124 (accessed on 21 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Ma, X.; Cai, F.; Liu, L.; Xu, Y.; Tu, Y. Reform of eco-governance and the green performance: A quasi-natural experiment based on the national ecological civilization pilot zone in China. Environ. Res. Commun. 2025, 7, 065020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingram, J.C.; Wilkie, D.; Clements, T.; McNab, R.B.; Nelson, F.; Baur, E.H.; Sachedina, H.T.; Peterson, D.D.; Foley, C.A.H. Evidence of payments for ecosystem services as a mechanism for supporting biodiversity conservation and rural livelihoods. Ecosyst. Serv. 2014, 7, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Li, Q.; Xue, W.; Xu, Z. Impacts of nature reserves on local residents’ income in China. Ecol. Econ. 2022, 199, 107494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Xiao, D.; Chang, M.S. The impact of carbon emission trading schemes on urban–rural income inequality in China: A multi-period difference-in-differences method. Energy Policy 2021, 159, 112652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Zhou, R.; Ding, F.; Guo, H. Does the construction of ecological civilization institution system promote the green innovation of enterprises? A quasi-natural experiment based on China’s national ecological civilization pilot zones. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 67362–67379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Guo, F.; Cao, J.; Yang, X. The road to eco-efficiency: Can ecological civilization pilot zone be useful? New evidence from China. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2024, 67, 477–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, B.; Zhao, P.; Peng, L.; Luo, Z. Can China’s ecological civilization strike a balance between economic benefits and green efficiency? A preliminary province-based quasi-natural experiment. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 1027725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, C.A.; Liu, X.; Zhang, X.; Dagestani, A.A. Does the national ecological civilization pilot zone achieve a “win-win” circumstance for the environment and the economy: Empirical evidence from China. Appl. Econ. 2025, 57, 10771–10787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pigou, A. The Economics of Welfare, 1st ed.; Macmillan: London, UK, 1920; pp. 189–196. [Google Scholar]

- Dethier, J.J.; Effenberger, A. Agriculture and development: A brief review of the literature. Econ. Syst. 2012, 36, 175–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teuber, R. Geographical indications of origin as a tool of product differentiation: The case of coffee. J. Int. Food Agribus. Mark. 2010, 22, 277–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oya, C.; Schaefer, F.; Skalidou, D.; McCosker, C.; Langer, L. Effects of certification schemes for agricultural production on socio-economic outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2017, 13, 1–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, D.; Goto, D. Impacts of sustainability certification on farm income: Evidence from small-scale specialty green tea farmers in Vietnam. Food Policy 2019, 83, 70–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, W.; Jiang, M.; Qi, J. Agricultural certification, market access and rural economic growth: Evidence from poverty-stricken counties in China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 81, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ming, L.E.I. Synthesize dual goals: A study on China’s ecological poverty alleviation system. J. Integr. Agric. 2021, 20, 1042–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Liu, Z. Does farmer economic organization and agricultural specialization improve rural income? Evidence from China. Econ. Model. 2012, 29, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naminse, E.Y.; Zhuang, J.; Zhu, F. The relation between entrepreneurship and rural poverty alleviation in China. Manag. Decis. 2019, 57, 2593–2611.11–2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L. An Empirical Analysis of Rural Labor Transfer and Household Income Growth in China. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 14, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ba, M.; Anwar, A.; Mughal, M. Non-farm employment and poverty reduction in Mauritania. J. Int. Dev. 2021, 33, 490–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Fan, Z.; Xiong, K.; Shen, H.; Guo, Q.; Dan, W.; Li, R. Current situation and prospects of the studies of ecological industries and ecological products in eco-fragile areas. Environ. Res. 2021, 201, 111613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, W.A. Economic development with unlimited supplies of labour. Manch. Sch. 1954, 22, 139–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benavente, J.M.; Lauterbach, R. Technological innovation and employment: Complements or substitutes? Eur. J. Dev. Res. 2008, 20, 318–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespi, G.; Tacsir, E.; Pereira, M. Effects of innovation on employment in Latin America. Ind. Corp. Change 2019, 28, 139–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, H.; Zou, C.; Liu, Y. The Impact of Farmland Transfer on Rural Households’ Income Structure in the Context of Household Differentiation: A Case Study of Heilongjiang Province, China. Land 2021, 10, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, K.; Yang, C.; Chen, Y. Land transfer in rural China: Incentives, influencing factors and income effects. Appl. Econ. 2020, 52, 5477–5490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Huang, X. The 30 m annual land cover dataset and its dynamics in China from 1990 to 2019. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 3907–3925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, Z.; Feng, Z.; Yang, Y. Relief Degree of Land Surface Kilometer Grid Dataset of China. Digit. J. Glob. Change Data Repos. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Shi, K.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S.; Chang, Z. Developing improved time-series DMSP-OLS-like data (1992–2019) in China by integrating DMSP-OLS and SNPP-VIIRS. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2021, 60, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Song, W.; Cheng, W.; Li, X. Has the development of leisure agriculture and rural tourism promoted the increase of farmers’ income: An evidence from quasi-natural experiment. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 42, 213–222. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Ma, J.; Li, T.; Ma, J. Does digital finance benefit the income of rural residents? A case study on China. Quant. Financ. Econ. 2021, 5, 664–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Gu, C.; Si, X.; Yan, Y. County-level Entrepreneurship, Farmers’ Income Increase and Common Prosperity: An Empirical Study Based on Chinese County-level Data. Econ. Res. J. 2023, 58, 40–58. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Fan, Y.; Cong, S. Financial support and sustainable income growth of the low-income groups. Econ. Theory Bus. Manag. 2024, 44, 65–82. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Atalay, R. The education and the human capital to get rid of the middle-income trap and to provide the economic development. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 174, 969–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.T.; An, M.Y. Human capital, entrepreneurship, and farm household earnings. J. Dev. Econ. 2002, 68, 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, D.; Rao, P. Urbanization and income inequality in China: An empirical investigation at provincial level. Soc. Indic. Res. 2017, 131, 189–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, Z.; Tu, Y.; Zhou, Z. The impact of financial development on the income and consumption levels of China’s rural residents. J. Asian Econ. 2022, 83, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.W.; Song, Y.; Ma, Y.T.; Tao, R. Is financial development narrowing the urban-rural income gap? A cross-regional study of China. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2019, 98, 1779–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, G.; Routray, J.K.; Ahmad, M.M. ICT infrastructure for rural community sustainability. Community Dev. 2022, 50, 51–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, F.; Wang, Z.; Tan, Q. The impact of rural infrastructural investment on farmers’ income growth in China. China Agric. Econ. Rev. 2022, 14, 202–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lu, Y.; Wang, J. Does flattening government improve economic performance? Evidence from China. J. Dev. Econ. 2016, 123, 18–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huan, Q. National Ecological Civilization Pilot Zone: From Theory to Practice. In Beautiful China: 70 Years Since 1949 and 70 People’s Views on Eco-Civilization Construction; Pan, J., Gao, S., Li, Q., Wang, J., Wu, D., Huang, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartik, T.J. Who Benefits from State and Local Economic Development Policies? 1st ed.; W.E. Upjohn Institute: Kalamazoo, MI, USA, 1991; pp. 213–215. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Q.; Qi, J.; Yan, G. DIDPLACEBO: Stata Module for In-Time, In-Space and Mixed Placebo Tests for Estimating Difference-in-Differences (DID) Models. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/software/bocbocode/s459225.htm (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Baker, A.C.; Larcker, D.F.; Wang, C.C.Y. How much should we trust staggered difference-in-differences estimates? J. Financ. Econ. 2022, 144, 370–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cengiz, D.; Dube, A.; Lindner, A.; Zipperer, B. The Effect of Minimum Wages on Low-Wage Jobs. Q. J. Econ. 2019, 134, 1405–1454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Abraham, S. Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. J. Econom. 2020, 225, 175–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, J.; Xue, W. Impact of the “Two Mountains” bases on the income of rural residents. China Popul. Resour. Environ. 2025, 35, 164–176. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.; Wu, W.; Xiong, L.; Wang, F. Is there an environment and economy tradeoff for the National Key Ecological Function Area policy in China? Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 104, 107347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; Dong, C. Can migrant workers return home to start businesses enhance the vitality of county economy? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2025, 98, 103950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qie, H.; Chen, H.; Lu, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Z. Evaluating the impact of agricultural product geographical indication program on rural income: A case study of the Yangtze River Delta region in China. J. Knowl. Econ. 2025, 16, 556–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Wang, J.; Wang, L.; Wu, B.; Ye, X.; Han, Y.; Wang, R.; Chandio, A.A. How do cooperatives alleviate poverty of farmers? Evidence from rural China. Land 2022, 11, 1836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhao, W. Enhancing Chinese Farmers’ Livelihoods: The Role of Non-Agricultural Employment and Social Capital. Hum. Ecol. 2025, 53, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, W.; Zheng, H.; Robinson, B.E.; Li, C.; Li, R. Comparing the importance of farming resource endowments and agricultural livelihood diversification for agricultural sustainability from the perspective of the food-energy-water nexus. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 380, 135193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Wang, Y.; Yang, L.; Li, C.; Chen, L. The impact of cropland transfer on rural household income in China: The moderating effects of education. Land Use Policy 2025, 148, 107399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, R. Transfers and incentives in intergovernmental fiscal relations. In Decentralization and Accountability of the Public Sector, 1st ed.; Burki, S.J., Perry, G.E., Eid, F., Freire, M.E., Vergara, V., Webb, S., Eds.; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Adenutsi, D.E. Entrepreneurship, Job Creation, Income Empowerment and Poverty Reduction in Low-Income Economies. MPRA Paper. 2011. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/29569 (accessed on 21 November 2025).

- Bosma, N.; Schutjens, V. Understanding regional variation in entrepreneurial activity and entrepreneurial attitude in Europe. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2011, 47, 711–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Peng, L.; Chen, J.; Deng, X. Impact of rural industrial integration on farmers’ income: Evidence from agricultural counties in China. J. Asian Econ. 2024, 93, 101761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, X.; Jin, Y. Analysis of the Impact and Mechanism of Carbon Trading Pilot Policies on the Urban-Rural Income Gap. Adv. Manag. Appl. Econ. 2025, 15, 151–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, W.; Leshan, J. How eco-compensation contribute to poverty reduction: A perspective from different income group of rural households in Guizhou, China. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 275, 122962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, S.; Xia, C.; Li, W.; Xian, J. Win-win path for ecological restoration. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 430–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |