Abstract

The Yangtze-to-Huaihe Water Diversion (YHWD) project has raised concerns about balancing economic benefits and ecological impacts in Lake Caizi, a nationally protected wetland recognized by the World Wildlife Fund. To assess post-diversion contamination and ecological risks, seasonal variation in polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) was investigated in surface sediments from Lake Caizi. Total PAH concentrations were 103–565 ng/g dw in the wet season, marginally exceeding the 97.1–526 ng/g dw observed in the dry season. The lowest levels occurred in the western sub-lake (Lake Xizi), showing marked declines relative to a decade ago, attributable to enhanced wastewater treatment, farmland-to-lake restoration, and a 10-year fishing ban. Conversely, PAH concentrations in the main lake, particularly the southeastern and northern sectors of the Caizi route, have increased, reflecting pollutant inflows from Zongyang County via the Yangtze River and accumulation driven by the diversion flows. The diagnostic ratio and positive matrix factorization model indicated biomass burning as the dominant PAH source in Lake Xizi across seasons. In contrast, PAH in the main lake were primarily derived from petroleum combustion and leakage, with coal combustion during the wet season shifting to coal combustion dominance in the dry season due to the seasonal halt of shipping activity. Although overall ecological risk remains low in Lake Caizi, localized hotspots near the Caizi routes and industrial zones pose moderate-to-high risks, necessitating continuous monitoring in the future.

1. Introduction

Lakes are essential components of regional water systems, supporting both human societies and natural ecosystems [1,2]. Lake ecosystems in good condition contribute markedly to social well-being, ecological integrity, and economic development [3,4]. However, accelerated urbanization and industrialization have intensified pressures on lake environments, especially through water pollution. Among various pollutants, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) are of considerable concern due to their teratogenic, carcinogenic, and mutagenic potential [5]. Both natural (e.g., wildfires, volcanic eruptions, and diagenesis) and anthropogenic sources (e.g., transportation, industrial activities, and energy use) contribute to PAH formation [6,7]. In urban areas, atmospheric deposition and surface runoff resulting from human activities represent key pathways for PAH inputs to lakes [8]. As a result, PAH contamination in lake environments typically intensifies with increasing urban development [9]. The Yangtze River Economic Belt, one of the most economically developed regions in China, hosts numerous lakes that are heavily contaminated with PAHs, particularly Lake Chaohu [10,11]. To improve water quality in Lake Chaohu and coordinate regional water resources, the Yangtze-to-Huaihe Water Diversion (YHWD) project—an important inter-basin water transfer initiative—was launched in 2021.

The YHWD project transfers water from the Yangtze River through Lake Caizi to Lake Chaohu, ultimately connecting to the Huaihe River [12]. As the first major node along this diversion route, Lake Caizi is essential for safeguarding the water quality of the overall transfer system. Over the past six decades, however, Lake Caizi has experienced substantial environmental stress driven by intensified human activities. Land reclamation around the lake has reached 7663 hectares, resulting in the loss of one-third of its original water area [13,14]. The rapid expansion of pen aquaculture and intensified fish farming have further reduced macrophyte coverage and shifted the lake from an oligotrophic to a eutrophic state [2,15]. Previous surveys along the Anqing section of the Yangtze River also reported that PAH concentrations in Lake Caizi were higher than those of neighboring lakes, raising serious concerns and underscoring the need for sustained monitoring [16].

Additionally, Lake Caizi contains provincial nature reserves and national wetland parks that are recognized by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF) [17], and it serves as an essential stopover and wintering habitat along the East Asia–Australia Flyway, supporting more than 80 species of migratory waterbirds [12,18]. Given that PAHs readily bioaccumulate and biomagnify through aquatic food webs, with potential transfer to terrestrial ecosystems [19], their presence in Lake Caizi poses direct risks to the health of migratory birds and may contribute to the long-distance transport of PAHs across regions via bird migration [20]. Furthermore, concerns have intensified following the implementation of the YHWD project, as the diversion of Yangtze River water has introduced additional pollutants into the lake [21,22]. Monitoring during the trial diversion period revealed a 122% increase in total nitrogen concentrations compared to pre-diversion conditions [23]. Accordingly, we hypothesize that PAH contamination in Lake Caizi may likewise have increased due to the new diversion pathway. Moreover, the artificial regulation of water levels during the dry season has disrupted natural seasonal hydrological patterns and reduced critical mudflat and shallow-water habitats for migratory birds to forage and rest [18,24]. Therefore, an assessment of seasonal variations in PAH-related ecological risks is required, along with a discussion of their potential implications for migratory waterbirds during the dry season under the influence of water diversion.

In light of these considerations, seasonal variations in PAH contamination and associated risks in Lake Caizi following the YHWD project are investigated in this study. Given their hydrophobicity and lipophilicity, PAHs readily associate with suspended particles and accumulate in sediments, which serve as the primary reservoir for these contaminants in aquatic environments [9,25]. Therefore, the key aspects addressed include (1) examining the seasonal variations and spatiotemporal distribution of PAH concentrations in the surface sediments of Lake Caizi; (2) identifying the potential sources and transport pathways of PAHs between two hydrological seasons; and (3) evaluating the potential ecological and toxicological risks posed by PAHs in this nature reserve post-YHWD. The outcomes of this research lay the foundation for future studies on the bioaccumulation and biomagnification of PAHs in aquatic organisms, thereby supporting the preservation of Lake Caizi’s ecological balance.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

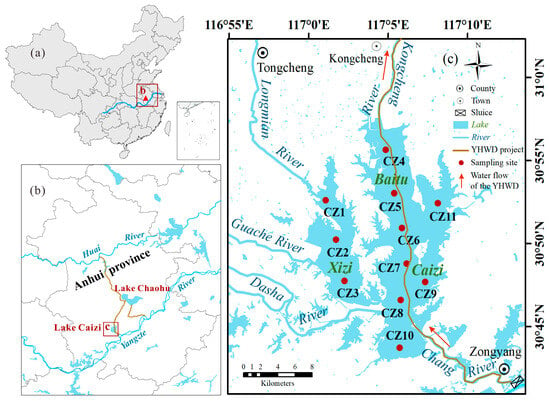

Lake Caizi, positioned at 30°43′–30°59′ N, 116°58′–117°11′ E, is an extensive floodplain body of water on the northern side of the Yangtze River in Anhui Province, China (Figure 1a,b) [2,17]. It is a typical shallow freshwater lake hydraulically connected to the Yangtze River, formed within the middle and lower reaches of the Yangtze floodplain [12]. The lake consists of three interconnected parts—Lake Baitu, Lake Caizi and Lake Xizi. Owing to its dominant spatial extent, Lake Caizi is commonly used to denote the entire lake system (Figure 1c) [2]. The elevation of the lake’s lakebed is approximately 8.5–9.0 m above sea level, and its average water depth is about 1.7 m [12,15]. The surface area of Lake Caizi varies seasonally, ranging from 145.2 km2 in winter to 242.9 km2 in summer, with corresponding water levels ranging from approximately 8.1 to 15.1 m, resulting in a total volume between 2.87 × 108 and 16.1 × 108 m3 [17]. This shallow lake experiences a subtropical monsoon climate, receiving annual precipitation ranging from 1200 to 1389 mm, mostly occurring from June to August. The average annual air temperature is around 16.5 °C [26]. The Lake Caizi watershed covers 3234–3346 km2, with inflow primarily supplied by the Dasha, Guache, Longmian, and Kongcheng rivers. Outflow to the Yangtze River is regulated by the Zongyang Sluice, which controls lake–river connectivity and flood discharge (Figure 1c) [12]. Land use in the watershed is dominated by agriculture and aquaculture activities [2,27]. After the completion of YHWD project, around 27 km of the Lake Caizi Route passes through central lake area, conveying water through the Kongcheng River to Lake Chao and ultimately into the Huai River system (Figure 1b,c) [12].

Figure 1.

Study area and sampling sites: (a) Location of Anhui province, China; (b) Overview of the study area in Anhui; (c) Detailed map of the YHWD project in Lake Caizi with sampling sites.

2.2. Sampling Strategy and Analytical Procedures

A total of eleven surface sediment sampling locations (CZ1–CZ11) were surveyed across Lake Caizi in February 2024, representing the dry season, and in July 2024, corresponding to the wet season. Although only 11 sampling sites were selected, they were distributed strategically across inflow (CZ1–CZ4), central (CZ5–CZ7, CZ9, CZ11), and outflow (CZ8, CZ10) zones in order to represent the hydrodynamic and pollution gradients of Lake Caizi. This design ensured the representativeness of sediment samples across the lake system. A grab sampler made of stainless steel was employed to obtain surface sediments (top 5 cm) at each site, with triplicate samples composited onsite. Following collection, samples were placed in amber glass containers that had been pre-cleaned with distilled water and n-hexane and preserved at −20 °C before analysis.

The samples were freeze-dried, homogenized, and ground to a fine powder with a mesh size of 100 (149 µm). Aliquots (3–5 g), after addition of surrogate standards, were subjected to dichloromethane extraction by accelerated solvent extraction (ASE-350, Dionex, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). To eliminate elemental sulfur, freshly made copper granules were introduced to individual sample. The extracts underwent further purification through a silica gel-alumina (2:1) column and eluted in sequence. Fifteen milliliters of n-hexane were discarded, and the mixture was then eluted with 70 mL of n-hexane/dichloromethane (7:3, v/v). The final extracts were reduced under a gentle nitrogen stream and processed according to the methods outlined by Li et al. [6,28].

Sixteen priority PAHs were quantified with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Agilent 1200, Santa Clara, CA, USA) using a series-wound fluorescence detector (FLD) and a diode-array detector (DAD). Separation was performed on a Supercoil LC-PAHs column (ODS, 250 mm × 3.0 mm × 5 μm, Supelco, Bellefonte, PA, USA). Additional details on reagents and analytical conditions are available in Chapter S1 of the Supplementary Materials (SM).

TOC (total organic carbon) was determined using an EuroVector organic element analyzer (EA3000, Milan, Italy). Prior to analysis, samples were freeze-dried, pulverized, and exposed to 3 M HCl to eliminate carbonates.

2.3. Quality Assurance and Control Measures

Peak identification of PAHs was relied on the comparison of UV spectra and retention times with those of reference standards analyzed under identical instrument conditions. An external-internal standard method was employed for quantification, with six-point calibration curves for each compound, resulting in coefficients (R) between 0.996 and 0.999. Precision was evaluated by the relative standard deviations (RSDs) of replicate injections, which were all <5% (0.19–1.93%). Retention time was recalibrated by analyzing a medium-concentration standard solution after every five samples. The range of method detection limits (MDLs) for individual PAH, calculated as a S/N ratio of 3, was from 0.02 to 0.42 ng/g dry weight. Laboratory blanks confirmed the absence of interferent contaminants throughout the test. Spiked recoveries of individual PAHs and surrogate standards exhibited a range of 72% to 105%, with diatomite (Fisher, Waltham, MA, USA) utilized as the sediment substitute at a baking temperature of 550 °C for a duration of six hours. Triplicate analyses were performed on all samples, with concentration variations in replicates < 10%. Details of method recoveries and MDLs are provided in Table S1.

2.4. Risk Evaluation Methodology

The Sediment Quality Index (SeQI), a tool developed by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment (CCME), was used to assess the sediment contamination levels [29]. Comprehensive information regarding the SeQI can be found in Chapter S2 of the SM. The sediment quality was classified into five categories based on SeQI scores: very poor (0–30, very high ecological risk), poor (30–50, high risk), fair (50–70, moderate risk), good (70–90, slight risk), and excellent (90–100, negligible risk) [17,30]. Additionally, given the carcinogenic properties of PAHs, the benzo[a]pyrene-equivalent toxic equivalency (TEQBaP) approach was applied to estimate the carcinogenicity of PAHs and their associated toxicity risk [9,31]. The TEQBaP calculation was computed as follows:

where Ci represents each PAH concentration (ng/g dw), and TEFi denotes the corresponding BaP factor for each PAH. TEF values are provided in Table S2. Additionally, an assessment of health hazards to humans was conducted to estimate the likelihood and potential adverse effects over a designated timeframe [32,33]. Dermal exposure to sediment during activities such as wading and swimming has been shown to pose health risks. To estimate the human dermal absorption of PAHs, the dermal absorbed dose (DAD) was calculated as:

where TEQBaPi is the TEQBaP for the i-th PAH (ng/g dw), and the other parameters are defined as the adherence factor (AF), dermal absorption fraction (ABS), exposure frequency (EF), exposure duration (ED), event frequency (EV), skin surface area (SA), conversion factor (CF), body weight (BW), and average time (AT). DAD parameters are listed in Table S3. For human health risk assessment, the values of BW and AT were based on statistical data for the Chinese population. Dermal cancer risk (DCR) was then calculated using the following equation:

where CSFd is the absorbed slope factor of BaP (kg·day/mg) as provided in Table S3.

2.5. Data Analysis Methods

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS version 22.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA) and the Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) 5.0 receptor model from the US EPA. Relative plots were created with Origin 2025 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, USA) to visually present the results. PAH concentrations were reported on a dry weight basis (ng/g dw). For all samples with concentrations below MDL, values were replaced with half the MDL for both descriptive statistics and PMF modeling, ensuring consistency across datasets. In the PMF model, uncertainty (Unc) was calculated as follows [34]:

Unc = 5/6 × MDL

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. PAH Concentrations and Distribution Patterns

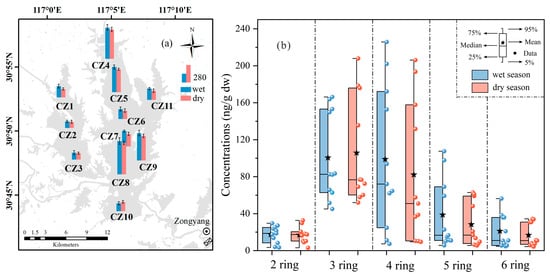

The 16 priority PAHs were identified in every surface sediment sample from Lake Caizi. In the wet season, total PAH concentrations varied between 103 and 565 ng/g dw, with a mean value of 277 ± 177 ng/g dw. In contrast, during the dry season, concentrations varied between 97.1 and 526 ng/g dw, averaging 250 ± 169 ng/g dw (Figure 2a, Table S4). Notably, PAH concentrations in the wet season were slightly higher than those in the dry season in the study area. However, paired-sample t-tests indicated that total PAH concentrations did not differ significantly between the wet and dry seasons (p = 0.802). These results suggest that seasonal variations are moderate rather than statistically significant. With respect to PAHs of varying ring numbers (Figure 2b), it was observed that during the wet season, concentrations of low molecular weight (LMW, 2–3 ring) compounds, including Naphthalene (Nap), Acenaphthene (Ace), Acnaphthylene (Acy), Phenanthrene (Phe), Fluorene (Flu), and Anthracene (Ant), ranged from 53.4 to 185 ng/g dw (mean 121 ± 51.1 ng/g dw). Concentration of high molecular weight (HMW) PAHs, represented by 4-ring compounds, including Fluoranthene (Flt), Pyrene (Pyr), Chrysene (Chr), and Benzo(a)anthracene (BaA), ranged from 7.32 to 226 ng/g dw (mean 102.3 ± 77.4 ng/g dw), while 5–6-ring compounds, including Benzo(a)pyrene (BaP), Dibenzo(a,h)anthracene (DahA), Benzo(b)fluoranthene (BbF), Benzo(k)fluoranthene (BkF), Benzo(g,h,i)perylene (BghiP), and Indeno(1,2,3-c,d)pyrene (IP), varied between 16.4 and 154 ng/g dw (mean 62.6 ± 54.2 ng/g dw). During the dry season, the concentrations of LMW PAHs were slightly elevated, ranging from 70.5 to 226 ng/g dw (mean 127 ± 59.7 ng/g dw). Four-ring compounds showed concentrations of 9.51–206 ng/g dw (mean 85.2 ± 75.5 ng/g dw), and 5–6-ring compounds ranged from 9.83 to 94.7 ng/g dw (mean 47.5 ± 36.5 ng/g dw). Overall, LMW PAHs in surface sediments of Lake Caizi were slightly lower in the wet season compared with the dry season, whereas HMW PAHs, particularly 4-ring compounds, were relatively more abundant in the wet season. Among individual PAH compounds, Pyr exhibited the highest concentration during the wet season (37.1 ± 32.3 ng/g dw), while Phe reached its maximum in the dry season (32.2 ± 24.1 ng/g dw). Additionally, Flt and Flu were consistently abundant across both seasons, whereas DahA and BkF occurred at the lowest concentrations (Table S1).

Figure 2.

(a) Spatial patterns and concentrations of PAHs in surface sediments of Lake Caizi during the wet and dry seasons; (b) Box plot of PAH compounds summarized by ring number in wet and dry seasons.

The adsorption of hydrophobic organic contaminants onto sediments plays a crucial role in their accumulation and persistence within sediment layers [35,36]. Because organic matter (OM) generally exhibits strong sorptive capacity, this study examined the influence of TOC on the distribution of PAHs in the sediments of Lake Caizi. The range of TOC content in the surface sediments was 2.71% to 6.72% during the wet season and 2.03% to 7.10% during the dry season (Table S4). However, correlation analyses conducted before and after log transformation revealed no significant relationships between TOC and individual or total PAH concentrations in either hydrological season (p > 0.05). This lack of correlation may result from differences in the sources and sorption behaviors of PAHs and TOC. PAHs and other organic materials associated with sediments undergo continuous adsorption–desorption exchanges [37], and equilibrium is difficult to establish in Lake Caizi due to its shallow nature, hydrological connection with the Yangtze River, and strong hydrodynamic disturbance. Another hypothesis is that anthropogenic inputs override the influence of TOC. When sediment sampling sites are located close to pollution sources, localized inputs may lead to elevated PAH concentrations that exert a stronger effect on PAH enrichment than TOC content alone [38,39].

Based on differences in PAH concentrations, the spatial distribution of PAHs in Lake Caizi can be classified into two categories (Figure 2a). PAH concentrations in sediments from the western part of Lake Caizi, namely Lake Xizi, were found to be lower than those in the main lake (Figure 2a). Sampling sites CZ1–3 exhibited relatively low PAH concentrations, averaging 125 ± 34.4 ng/g dw during the wet season and 107 ± 11.9 ng/g dw during the dry season. In comparison with earlier investigations, PAH concentrations in Lake Xizi have dramatically decreased, from an average of 1070 ng/g dw ten years ago [16]. This decline can be attributed to a number of initiatives implemented by the Anqing Municipal Government, including improved wastewater treatment and the policy of returning farmland to lakes, as well as the 10-year fishing ban that has been in place for the last five years [26,40]. Since 1995, Lake Xizi has been the first area within Lake Caizi to implement enclosure farming and artificial fish release for aquaculture. Large areas of land have been reclaimed in the vicinity of the lake, with a total area of approximately 4989 hectares [41]. Furthermore, the lake has continuously received industrial and domestic wastewater from Tongcheng County via the Longmian River [16]. All of these resulted in historically substantial PAH levels in Lake Xizi. Fortunately, government measures to control PAH emissions and transform Lake Xizi into an ecotourism destination (Lake Xizi Wetland Park) have played a crucial role in significantly reducing PAH contamination and facilitating the restoration of the lake ecosystem.

PAH concentrations in the main lake (mean: 336 ± 165 ng/g dw in the wet season and 303 ± 159 ng/g dw in the dry season), however, were higher than those reported in an earlier investigation (mean: 280 ng/g dw) [16]. Specifically, sites in the southeastern part of the main lake, such as CZ8 (565 ng/g dw in the wet season; 526 ng/g dw in the dry season) and CZ9 (447 ng/g dw in the wet season; 405 ng/g dw in the dry season), together with the northern sites CZ4 (523 ng/g dw in the wet season; 495 ng/g dw in the dry season) and CZ5 (440 ng/g dw in the wet season; 397 ng/g dw in the dry season), exhibited markedly elevated levels during both seasons (Figure 2a). As a key transit point of the YHDW Project, the main part of Lake Caizi has become more vulnerable to pollutant inflow from industrial sources in Zongyang County via the Yangtze River [21,42]. It is hypothesized that these pollutants accumulate in the southeastern area and are subsequently transported northward with the diversion flow toward the Kongcheng River outlet, leading to the elevated PAH burdens. Moreover, the new opening of the Lake Caizi shipping line on 16 September 2023, has increased the number of vessels on the main lake [43]. Frequent shipping activities also added PAH inputs, especially in the northern and southeastern extremes of the shipping line. By contrast, site CZ10, located near Lake Caizi Wetland Park and surrounded by forested areas with limited anthropogenic disturbance, showed comparatively low PAH concentrations, reflecting minimal impact from the YHDW Project. Compared to other regions in China, PAH levels in Lake Caizi are substantially lower than those in eastern China, such as Taihu Lake (1381.48–4682.16 ng/g dw) [44] and Chaohu Lake (158.19–1693.64 ng/g dw) [45]. Instead, they are more comparable to, or slightly lower than, lakes in western China, including Lake Bosten in Xinjiang (51.1–584 ng/g dw) [46] and lakes on the Tibetan Plateau (50.0–195 ng/g dw) [47]. These findings indicate that, despite localized hotspots, PAH contaminations in Lake Caizi remain at a moderate to low polluted level overall.

3.2. Compositions and Source Apportionment of PAHs

3.2.1. Compositions and Diagnostic Ratios

The compositional characteristics of PAHs, together with diagnostic ratios of specific compounds, are widely applied as molecular markers to trace potential PAH sources [28,48]. Generally, petrogenic inputs with incomplete combustion at lower temperatures (e.g., burning grass and wood) are characterized by the predominance of LMW PAHs, whereas pyrogenic sources involving the higher pyrolysis of fossil fuels (e.g., coke or traffic emissions) are generally enriched in HMW PAHs [49]. Therefore, LMW/HMW PAHs could provide a basis for distinguishing between petrogenic and pyrogenic sources of the overall PAH burden in the lake, where values greater than 1 suggest petrogenic sources and values less than 1 suggest pyrogenic sources. In particular, compounds such as Flt and Pyr are structural isomers that are typically released during fossil combustion. An Flt/(Flt + Pyr) ratio of less than 0.4 suggests petrogenic/petroleum sources, a ratio between 0.4 and 0.5 suggests petroleum combustion, and a ratio greater than 0.5 suggests the combustion of grass, wood, and domestic coal [50,51]. In this study, PAHs detected in surface sediments were classified into three ring-number-based categories (2–3-ring, 4-ring, and 5–6-ring PAHs) to preliminarily infer their potential sources in Lake Caizi. The relative proportions of each category, along with selected diagnostic ratios, were then calculated for different hydrological periods in the study area.

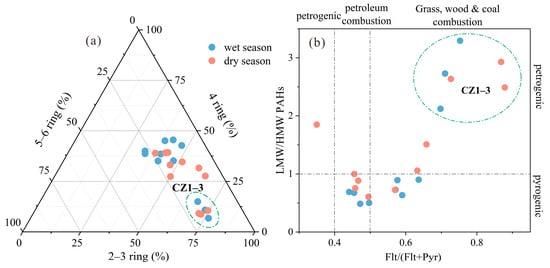

As shown in Figure 3a, the PAH compositions in Lake Caizi exhibited similar patterns during both the wet and dry seasons, with 2–3-ring compounds predominating. In the wet season, 2–3-ring PAHs accounted for 32.7–76.7% (mean 49.3 ± 15.9%), while in the dry season, this proportion slightly increased to 37.7–74.5% (mean 56.3 ± 13.3%) (Figure 3a). In contrast, 4-ring PAHs contributed less, accounting for 6.74–45.5% (mean 31.8 ± 14.2%) in the wet season and 8.73–39.2% (mean 26.6 ± 12.2%) in the dry season. The contribution of 5–6-ring PAHs was the lowest, ranging from 12.4–27.9% (mean 18.9 ± 5.75%) in the wet season to 7.42–23.4% (mean 17.1 ± 5.25%) in the dry season (Figure 3a). Notably, the proportion of 4-ring PAHs in Lake Xizi (CZ1–3) was particularly low, with mean values of only 10.8 ± 4.12% and 9.48 ± 0.965% in the wet and dry seasons, respectively, whereas the proportion of 2–3-ring PAHs was significantly high (mean 70.6 ± 4.41% and 72.8 ± 1.63%, respectively) (Figure 3a). After excluding the LMW PAH data from Lake Xizi, the average proportion of LMW PAHs in the main body of Lake Caizi decreased by 8.98% in the wet season and 6.79% in the dry season. Consequently, the relative contribution of HMW PAHs increased to 59.7% in the wet season and 49.5% in the dry season. These results suggest that the PAH sources in Lake Xizi may differ from those in the main lake, where LMW PAHs consistently dominated regardless of hydrological season. In contrast, the main lake showed a remarkable increase in HMW PAHs during the wet season, indicating that the origins of PAHs may vary between the wet and dry seasons.

Figure 3.

(a) PAH compositional profiles and (b) diagnostic cross-plot of LMW/HMW versus Flt/(Flt + Pyr) for surface sediments from Lake Caizi in both seasons.

When considering the two diagnostic ratios of selected PAH compounds, the LMW/HMW ratios of Lake Xizi were consistently greater than 1 across both seasons, and the Flt/(Flt + Pyr) ratios exceeded 0.5 (Figure 3b), both suggesting that the predominant origins of PAHs in Lake Xizi are petrogenic/petroleum-related inputs, along with incomplete combustion of biomass (wood, grass) and/or coal. Given its proximity to Lake Xizi Wetland Park and its partial encirclement by agricultural land, it is likely that petroleum leakage from tourist boats, as well as common agricultural practices such as wood/coal burning for heating and cooking and straw burning for material reduction and fertilization [42], are the main contributors to PAH contamination in this area. In comparison, PAH sources in the main body of Lake Caizi appear to be more complex. During the wet season, most LMW/HMW ratios were close to or less than 1, indicating pyrogenic combustion as the dominant PAH source in the main lake (Figure 3b). Combined with the Flt/(Flt + Pyr) ratio, values between 0.4 and 0.5 at sites CZ4–5 and CZ8–9 suggest that PAHs in the northern and southeastern parts of the lake are predominantly derived from high-temperature pyrolytic petroleum combustion, such as emissions from vessels and other industrial and urban activities. By contrast, at most of the remaining sites, where the ratio exceeds 0.5, the PAH likely results from incomplete combustion of coal, wood, and other biomass sources. During the dry season, however, both the LMW/HMW and Flt/(Flt + Pyr) ratios showed a more scattered distribution (Figure 3b), suggesting that PAHs in the main lake originated from mixed sources, including both petrogenic/petroleum inputs and pyrogenic combustion. This indicates a shift in the source pattern of PAHs, with the main Lake Caizi being predominantly affected by combustion-related sources during the wet season and by mixed sources during the dry season.

Summing up, qualitatively, Lake Xizi is predominantly impacted by unburned petroleum leakage and biomass burning linked to agricultural activities in both hydrological seasons. Meanwhile, the main body of Lake Caizi is more influenced by combustion-related sources during the wet season and by a combination of sources in the dry season. Given the complexity and variability of the PAH pollution sources, particularly in the dry season, a more quantitative approach was employed to further resolve the contributions from various sources. To this end, the PMF model was utilized to quantify the relative contributions from each identified source.

3.2.2. PMF Model

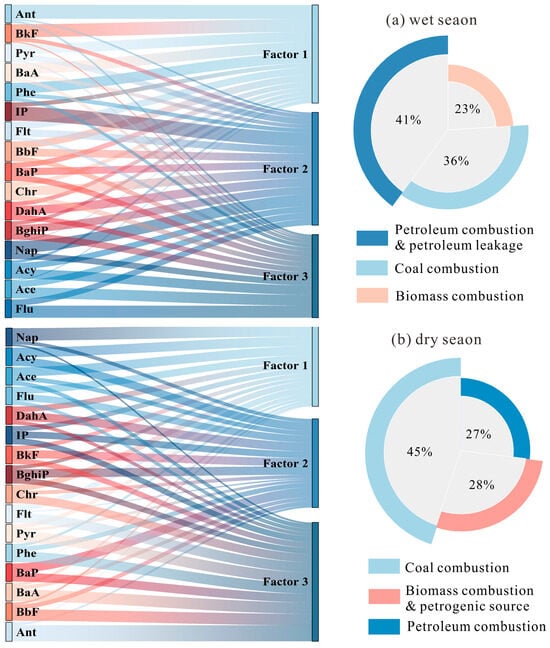

Two datasets were entered into the PMF 5.0 model, and a thorough description of the PMF analysis based on PAH concentrations, along with its limitations and the process for determining the optimal number of factors, is provided in Chapter S3. As a result, the PMF model resolved three contributing factors under two hydrological seasons (Figure 4; Figure S1).

Figure 4.

Contribution of individual PAH species and the quantitative input of identified sources by the PMF model during the (a) wet and (b) dry seasons.

During the wet season, Factor 1 was primarily characterized by the presence of Ant, BkF, Pyr, BaA and Phe, which are key tracers linked to the emission of coal combustion, including from sources such as coal-based power stations, industrial combustion units, and household coal burning [52]. Hence, Factor 1 reflects the contribution of coal combustion. Factor 2 exhibited significant correlations with IP, DahA, BghiP, BbF, BaP, Nap and Chr. IP, BbF and DahA are recognized as indicators of diesel combustion, while BghiP and BaP are associated with gasoline combustion [6,53]. Additionally, Nap is linked to petroleum volatilization or spills [47,54]. Therefore, Factor 2 is indicative of pyrogenic petroleum combustion with the occasional petroleum leakage. Factor 3 was dominated by Flu, Acy and Ace, compounds that are characteristic of biomass combustion, particularly from straw and firewood burning [9,53]. Consequently, Factor 3 represents biomass combustion. The quantitative contributions of these three PAH sources in the wet season of the main lake suggest that petroleum combustion and leakage, along with coal combustion, are the primary drivers of PAH contaminations, accounting for 41% and 36% of the total contribution, respectively. In contrast, biomass combustion contributes less significantly, at only 23% (Figure 4a).

In comparison, the PMF model for the dry season revealed that Factor 1 is mainly made up of LMW PAHs, such as Nap, Flu, Acy, and Ace, which are markers of biomass combustion along with some petrogenic processes. Factor 2 was defined by the presence of BaP, BghiP, DahA, BkF and BaP as the dominant species, compounds mainly emitted from traffic transportation sources. Thus, Factor 2 represents petroleum combustion and petroleum leakage. The main components of Factor 3 included Ant, BbF, BaA, Phe, Pyr and Flt, which were largely attributed to coal combustion. As a result of the model, it indicates a shift in the primary PAH source during the dry season, with coal combustion becoming the dominant contributor, accounting for 45% of the total contribution, while the contribution from petroleum combustion decreasing by 14%. The contribution from biomass combustion with a petrogenic source remained relatively stable, with a slight increase of 4% in the dry season (Figure 4b).

Generally speaking, the primary PAH sources in the main body of Lake Caizi could be roughly classified into three categories: petroleum combustion and leakage, coal combustion, and biomass combustion with some petrogenic processes. During the wet season, PAH pollution is primarily derived from a mixture of petroleum combustion and leakage, alongside coal combustion sources. In contrast, during the dry season, coal combustion becomes the dominant source, with a significant reduction in the contribution from petroleum sources. This seasonal shift is primarily influenced by the completion of the YHWD Project and the subsequent opening of the Lake Caizi shipping line. This new line, part of the Jianghuai Canal, links the Yangtze River and the Huaihe River, bypassing the Jing-Hang Canal and reducing transportation distances by 200–600 km [55]. As a result, there has been a significant increase in shipping activity within Lake Caizi. Statistics showed that during the trial operation of the Lake Caizi line from September to October 2023, a total of 21,945 vessels passed through the lock, with traffic showing a steady upward trend [44]. Consequently, the combustion of gasoline and diesel in ships, along with occasional petroleum spills, has become a major source of PAHs in the main body of Lake Caizi, particularly during the wet season. From November to March, during the migratory bird wintering period, all shipping activities along the Lake Caizi line are suspended [55]. This seasonal halt, thus, results in a significant reduction in petroleum-derived PAH pollution from shipping traffic during the dry season. Furthermore, Zongyang County, located in the southeast of Lake Caizi, hosts 23 metal mining sites and 106 non-metallic mining sites, as well as the Conch Cement Plant [56]. The frequent industrial activities in the area contribute to coal combustion, which, along with the water diversion project, brings coal combustion-derived PAHs from the Yangtze River into Lake Caizi. It is worth noting that the water level of Lake Caizi has risen by nearly two meters over the past three years during the dry season [18], which has exacerbated the influx of PAHs, particularly from coal combustion, during this period. Additionally, the surrounding agricultural land in the Lake Caizi basin, mainly used for seasonal crops such as rapeseed and rice [27,42], contributes to a relatively stable source of biomass combustion throughout the year. However, during the winter months, the need for household heating leads to an increase in the burning of coal and wood for domestic heating, slightly elevating the biomass combustion and petrogenic-related PAH input in the dry season compared to the wet season.

3.3. Environmental Risk Evaluation of PAHs

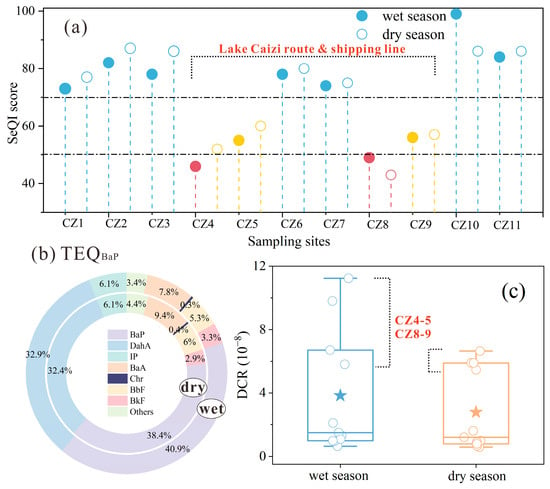

Sediment quality at Lake Caizi sampling sites was evaluated using SeQI scores, ranging from 46 to 100 (mean 70.5 ± 16.8) in the wet season and from 43 to 87 (mean 71.5 ± 15.7) in the dry season (Figure 5a). LMW PAHs, specifically Acy, Ace, and Flu, were identified as the predominant contributors. Overall, most sediments in this region exhibited high SeQI scores (>70), revealing favorable sediment quality and low PAH-related risk to aquatic organisms and migratory waterbirds year-round. However, the SeQI scores for sediments under the Lake Caizi shipping line were comparatively lower, particularly at the lake entrances and exits at the northern and southern extremes of the line. The SeQI scores at CZ4–5 and CZ8–9 were generally between 40 and 70, indicating a moderate to high risk of PAH contaminations (Figure 5a). Pyr, DahA, BaP, and BaA were significant contributors to PAH risk at these sites, in addition to LMW PAHs. As a result, the potential ecological risks posed by PAHs due to frequent shipping activities along this route cannot be overlooked, necessitating continuous monitoring in the future.

Figure 5.

(a) Sediment quality index (SeQI), (b) Benzo[a]pyrene-based toxic equivalency (TEQBaP), and (c) Dermal cancer risk in Lake Caizi during both seasons.

To better assess PAH toxicity, the TEQBaP method was applied, a widely recognized approach for estimating the toxicity risks associated with PAHs. The TEQBaP values for PAHs during the wet season were in the range of 3.92–69.8 ng/g dw (mean 23.8 ± 23.9 ng/g dw), higher than those during the dry season (range: 3.60–41.3 ng/g dw; mean 17.3 ± 15.9 ng/g dw). As shown in Figure 5b, seven PAHs—BaA, Chr, BbF, BkF, BaP, DahA, and IP—are classified as carcinogenic (TEQ7carc), and together, they contributed approximately 96% of the total TEQBaP in both seasons. Among these, BaP was the predominant toxic species, followed by DahA, BaA, BbF, and IP (Figure 5b), which were primarily derived from petroleum combustion. Although the current TEQBaP values exhibited a relatively low toxicity risk, the substantial contribution of TEQ7carc raises concerns about their long-term carcinogenic potential, particularly along the shipping line. The DCR was therefore chosen to diagnose the carcinogenic risks among these sites. As a result, the DCR values ranged from 6.31 × 10−9 to 1.12 × 10−7 in the wet season and from 5.80 × 10−9 to 6.65 × 10−8 in the dry season (Figure 5c), all of which were below the safety threshold of 10−6 [33,57], revealing no significant cancer risk in this region under current conditions. Overall, the aquatic environment of Lake Caizi remains in generally good condition with respect to PAH contamination following the implementation of the YHWD project; however, localized ecological risks persist in areas subject to intensified water diversion and shipping activities. Carcinogenic compounds, particularly BaP, DahA, and BaA, were identified as the major contributors to these risks. These findings underscore the need for continued, long-term monitoring of PAHs in Lake Caizi to protect the wetland ecosystem and to minimize large-scale PAH cycling through migratory waterbirds. Accordingly, the following subsection discusses the broader implications of our findings, the limitations of the single-year/two-time-point design, and priorities for future research.

3.4. Implications, Limitations, and Future Research Needs

Our results provide an overview of the seasonal variation in PAH contamination in the surface sediments of Lake Caizi, based on two sampling campaigns conducted during the dry and wet seasons of 2024. Despite moderate levels of PAH contamination across the lake, consistent spatial hotspots were identified along the shipping corridor and in the northern and southeastern sectors of the main lake, suggesting that hydrological connectivity with the Yangtze River and intensified navigation activities promote localized PAH accumulation and associated ecological risks. The observed seasonal differences in source contributions—a greater influence of petroleum combustion and leakage during the wet season and increased coal combustion during the dry season—suggest that hydrological regime and seasonal management measures (e.g., suspension of shipping during winter) jointly regulate PAH inputs and redistribution.

Nevertheless, the broader applicability of these findings across temporal scales should be interpreted with caution. Sampling was limited to two time points within a single year, which restricts the evaluation of interannual variability and the representativeness of seasonal contrasts. In shallow floodplain lakes, such as Lake Caizi, extreme rainfall and flooding events can substantially enhance runoff, sediment resuspension, and episodic deposition, potentially leading to atypical PAH accumulation patterns and short-term exposure pulses that are not captured by routine seasonal sampling. Moreover, source apportionment based on diagnostic ratios and PMF reflects the conditions during the sampling periods and may be influenced by transient events and spatial heterogeneity.

Therefore, future research should prioritize multi-year monitoring to resolve interannual variability as well as event-based sampling following extreme hydrological conditions to better characterize pulse-driven PAH transport and deposition. Integrating chemical measurements with sedimentological and hydrodynamic indicators would further improve mechanistic understanding of PAH behavior and support more robust risk assessment and sustainable management of navigation- and diversion-affected lake systems.

4. Conclusions

Following the operation of the YHWD project and the establishment of the Lake Caizi shipping line, the contamination characteristics of PAHs in surface sediments have undergone a marked transformation. Overall concentrations corresponded to a moderate pollution level, with seasonal variability—higher during the wet season and lower during the dry season—and heterogeneous spatial distribution. While PAH concentrations in Lake Xizi have declined substantially, levels in the main lake have increased, particularly in the northern and southern inflow–outflow sections. Source apportionment indicated that PAHs in Lake Xizi across both hydrological seasons were dominated by biomass combustion related to surrounding agricultural activities, characterized by a predominance of LMW PAHs. In contrast, the main lake exhibited distinct seasonal shifts: during the wet season, petroleum combustion and leakage from intensified shipping activity, combined with coal combustion transported via diversion flows from industrial activity in Zongyang County, were the major contributors. During the dry season, seasonal suspension of navigation led to a reduction in petroleum-related inputs, with industrial coal combustion becoming the dominant source. Sediment quality was generally favorable; however, moderate ecological risks remained at the shipping corridor hotspots, where carcinogenic PAHs (notably BaP, DahA and BaA) dominated TEQ contributions. Although DCR values were below the safety threshold at all sites, continued monitoring is warranted to protect the wetland ecosystem and reduce potential PAH cycling via migratory waterbirds. Given the two-season snapshot within a single year, multi-year and event-based sampling is recommended to better resolve interannual variability and pulse-driven transport under extreme hydrological conditions.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010446/s1, Chapter S1: PAH analysis; Chapter S2: Sediment Quality Index (SeQI); Chapter S3: Limitation and details for positive matrix factorization (PMF); Table S1: Concentrations and recoveries for 16 priority PAHs in Lake Caizi; Table S2: Proposed toxicity equivalency factors (TEFs) for individual PAHs [58]; Table S3: The parameters for health risk assessment [33]; Table S4: Total PAHs and TOC concentrations with detailed information on sampling sites; Figure S1: PMF model for PAH source apportionment during the wet and dry season, respectively, in the main body of Lake Caizi.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.L. and W.H.; methodology, Q.L. and T.D.; formal analysis, Q.L. and F.Z.; investigation, Q.L. and X.Z.; resources, Q.L. and T.D.; data curation, F.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.L.; writing—review and editing, Q.L., F.Z. and W.H.; visualization, W.H.; funding acquisition, T.D. and X.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42401320), and the Natural Science Foundation of Universities of Anhui Province (2022AH050198).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to Nanjing Institute of Geography and Limnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for their assistance with this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Schallenberg, M.; de Winton, M.D.; Verburg, P.; Kelly, D.J.; Hamill, K.D.; Hamilton, D.P. Ecosystem services of lakes. In Ecosystem Services in New Zealand: Conditions and Trends; Manaaki Whenua Press: Lincoln, New Zealand, 2013; pp. 203–225. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Z.; Zhu, G.; Zhu, M.; Xu, H.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Gui, Z.; Zou, W.; Fan, Z. Limiting factors on aquatic ecological health of Caizi Lake, a Changjiang River-isolated shallow lake: Implications for lake restoration. J. Ocean. Limnol. 2025, 43, 1923–1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhateria, R.; Jain, D. Water quality assessment of lake water: A review. Sustain. Water Resour. Manag. 2016, 2, 161–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grmasha, R.A.; Stenger-Kovács, C.; Al-Sareji, O.J.; Al-Juboori, R.A.; Meiczinger, M.; Andredaki, M.; Idowu, I.A.; Majdi, H.S.; Hashim, K.; Al-Ansari, N. Temporal and spatial distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the Danube River in Hungary. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 8318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Gaya, B.; Martínez-Varela, A.; Vila-Costa, M.; Casal, P.; Cerro-Gálvez, E.; Berrojalbiz, N.; Lundin, D.; Vidal, M.; Mompeán, C.; Bode, A.; et al. Biodegradation as an important sink of aromatic hydrocarbons in the oceans. Nat. Geosci. 2019, 12, 119–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Guo, R.; Wu, J.; Jin, M. Sedimentary records of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and organochlorine pesticides to reconstruct anthropogenic activities in Lake Issyk-Kul region (Kyrgyzstan), and their effects on the lake environment. Anthropocene 2024, 45, 100426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balint, A.; Matei, E.; Râpă, M.; Şăulean, A.-A.; Mateş, M. Human Exposure Estimation of Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons (PAHs) Resulting from Bucharest Landfill Leakages. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Yao, X.; Ding, Q.; Gong, X.; Wang, J.; Tahir, S.; Kimirei, I.A.; Zhang, L. A comprehensive evaluation of organic micropollutants (OMPs) pollution and prioritization in equatorial lakes from mainland Tanzania, East Africa. Water Res. 2022, 217, 118400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gong, X.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, L.; Yao, S.; Xue, B. North-south geographic heterogeneity and control strategies for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in Chinese lake sediments illustrated by forward and backward source apportionments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2022, 431, 128545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, C.; Huo, S.; Yu, Z.; Guo, W.; Xi, B.; He, Z.; Zeng, X.; Wu, F. Historical records of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon deposition in a shallow eutrophic lake: Impacts of sources and sedimentological conditions. J. Environ. Sci. 2016, 41, 261–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, H.R.; Zhang, X.T.; Zhao, L.L.; Peng, S.C.; Wang, J.Z.; Chen, Y.H. Variations in the concentration, inventory, source, and ecological risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediments of the Lake Chaohu. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2024, 201, 116188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zha, D.; Zhao, B.; Yang, S.; Zhang, B.; Boer, W. Predicting hydrological impacts of the Yangtze-to-Huaihe Water Diversion Project on habitat availability for wintering waterbirds at Caizi Lake. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 249, 109251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Yang, S.; Bao, M.; Yang, Y.; Li, C. Predicting the impact of the water transfer project from Yangtze River to Huai River on habitats of wintering waterbirds in Caizi Lake using remote sensed images. Ecol. Sci. 2019, 38, 71–78, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Zhai, H.; Guo, W.; Wang, H.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; Wang, H.; Zhang, X. Characteristics and historical changes of fish community in Caizi Lake during the early period of the “10-year fishing ban”. Acta Hydrobiol. Sin. 2024, 48, 1414–1427, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Z.; Xu, N.; Liu, B.; Zhou, L.; Wang, J.; Wang, C.; Dai, B.; Xiong, W. Metal concentrations and risk assessment in water, sediment and economic fish species with various habitat preferences and trophic guilds from Lake Caizi, Southeast China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 157, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.; Cheng, H.; Cao, J.; Zhou, B.; Xu, Z.; Zuo, Y.; Yao, J.; Wang, Y.; Jin, T. Distribution and ecological risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in sediments from Anqing section of Yangtze River and lakes around Anqing City. Environ. Chem. 2016, 35, 739–748, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- An, L.; Liao, K.; Zhu, L.; Zhou, B. Influence of river-lake isolation on the water level variations of Caizi Lake, lower reach of the Yangtze River. J. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 551–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Cheng, B.; Li, H.; Zhou, L.; Yan, F.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Q.; Singh, V.; Cui, L.; Jiang, B. Deteriorating wintertime habitat conditions for waterfowls in Caizi Lake, China: Drivers and adaptive measures. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 953, 176020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Zhao, Z.; Gong, X.; Feng, F.; Wu, J. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) and organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in tissues of two aquatic bird species from Poyang Lake, China. Fresen. Environ. Bull. 2017, 26, 3906–3918. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, X.; Zheng, X.; Bai, F.; Wu, Y.; Lei, W.; Zhang, Z.; Mai, B.X. Pollutant exposure for Chinese wetland birds: Ecotoxicological endpoints and biovectors. ACS EST Water 2024, 4, 2076–2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Zhang, J.; Wang, H.; Tang, P.; Liu, Y. Water Quality Pollution Characteristics and Health Risk Assessment in Caizi Lake from 2011 to 2023. Environ. Sci. Surv. 2025, 44, 59–66, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Gao, N.; Liang, Y.; Li, J.; Cui, K.; Lu, W. Bacterial community composition and indicators of water quality in Caizi Lake, a typical Yangtze-connected freshwater lake. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2022, 369, fnac084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Tian, X.; Wu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, K.; Chen, S. Water quality response changes in Caizi Lake and Chaohu Lake during the trial water diversion of the Yangtze-to-Huaihe Project. Water Resour. Plan. Des. 2025, 6, 58–74. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cui, L.; Wei, Z.; Zhou, L.; Cheng, B. Effects of constant high water levels in winter on waterbird diversity in Caizi Lakes: A functional perspective. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 2024, 52, e02934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Luo, X.; Li, F.; Dai, J.; Guo, J.; Chen, S.; Hong, C.; Mai, B.; Xu, M. Organochlorine compounds and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in surface sediment from Baiyangdian Lake, North China: Concentrations, sources profiles and potential risk. J. Environ. Sci. 2010, 22, 176–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Liu, Z.; Guo, W.; Zhou, Z. Effect of Aquatic Vegetation Restoration after Removal of Culture Purse Seine on Phytoplankton Community Structure in Caizi Lakes. Diversity 2022, 14, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Wang, F.; Guo, E.; Li, H.; Fang, F. Analysis of heavy metal enrichment, transport and influencing factors in the soil-plant system of Caizi Lake wetland. Acta Sci. Circumstantiae 2025, 45, 373–383, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhou, J.; Sakiev, K.; Hofmann, D. Occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (PAH) in soils around two typical lakes in the western Tian Shan Mountains (Kyrgyzstan, Central Asia): Local burden or global distillation? Ecol. Indic. 2020, 108, 105749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CCME (Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment). Canadian Soil Quality Guidelines for the Protection of Environmental and Human Health; Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment: Winnipeg, MB, Canada, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, W.; Gong, X.; Shang, J.; Qin, Y.; Yao, X.; Wang, Z.; Liu, X.; Gao, G.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z. Spatial heterogeneity of antibiotic pollution in Chinese lakes: A nationwide study with emphasis on arid zones. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 391, 126556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Lang, Y.; Yang, W.; Peng, P.; Wang, X. Source contributions of PAHs and toxicity in reed wetland soils of Liaohe estuary using a CMB–TEQ method. Sci. Total Environ. 2014, 490, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, C.; Albanese, S.; Li, J.; Cicchella, D.; Zuzolo, D.; Hope, D.; Cerino, P.; Pizzolante, A.; Doherty, A.L.; Lima, A. Organochlorine pesticides in the soils from Benevento provincial territory, southern Italy: Spatial distribution, air-soil exchange, and implications for environmental health. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 674, 159–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Li, Q.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, Z.; Xue, B.; Yao, S.; Wang, X.; Cai, Y. The occurrence of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) in riverine sediments of hilly region of southern China: Implications for sources and transport processes. J. Geochem. Explor. 2020, 216, 106580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norris, G.; Duvall, R.; Brown, S.; Bai, S. EPA Positive Matrix Factorization (PMF) 5.0 Fundamentals and User Guide; Prepared for the US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Research and Development: Washington, DC, USA; Petaluma, CA, USA, 2014.

- Accardi-Dey, A.; Gschwend, P.M. Assessing the combined roles of natural organic matter and black carbon as sorbents in sediments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skic, K.; Boguta, P.; Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A.; Ukalska-Jaruga, A.; Baran, A. Effect of sorption properties on the content, ecotoxicity, and bioaccumulation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in bottom sediments. J. Hazard. Mater. 2023, 442, 130073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yun, X.; Yang, Y.; Liu, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, J. Distribution, seasonal variations, and ecological risk assessment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the East Lake, China. Clean–Soil, Air Water 2016, 44, 506–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kucklick, J.R.; Sivertsen, S.K.; Sanders, M.; Scott, G.I. Factors influencing polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon distributions in South Carolina estuarine sediments. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 1997, 213, 13–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, X.; Xiao, L.; Zhao, Z.; Li, Q.; Feng, F.; Zhang, L.; Deng, Z. Spatial variation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in surface sediments from rivers in hilly regions of Southern China in the wet and dry seasons. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2018, 156, 322–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Cheng, L.; Song, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, G.; Li, C. Differences in Waterbird Communities between Years Indicate the Positive Effects of Pen Culture Removal in Caizi Lake, a Typical Yangtze-Connected Lake. Ecologies 2024, 5, 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L. The Effect of Lake Wetland Degradation on Foraging Activities of the Wintering Hooded Crane (Grus monachal). Master’s Thesis, Anhui University, Hefei, China, 2015. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- Huang, F.; Ma, K.; Gu, P.; Wang, L.; Tan, K.; Song, J.; Zhao, K. Preliminary analysis of organophosphate contamination in Caizi Lake line and its correlation with microbial community characteristics. Asian J. Ecotoxicol. 2024, 19, 377–389, (In Chinese with English Abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Wang, E.; Zhou, X.; Wang, D. Analysis of the trial operation of the Jianghuai Canal. Ship. Manag. 2025, 47, 37–42. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Lang, X.; He, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, Z.; Sun, T. Spatial occurrence and sources of PAHs in sediments drive the ecological and health risk of Taihu Lake in China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 3668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, G.; Liu, R.; Wu, H.; Shen, M.; Yousaf, B.; Wang, X. COVID-19 lockdown measures affect polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons distribution and sources in sediments of Chaohu Lake, China. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 951, 175608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Sun, L.; Zang, S. History of atmospheric PAHs sedimentation and response to human activities in Bosten Lake in Western China. Arab. J. Geosci. 2021, 14, 1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Yu, H.; Shi, K.; Shang, N.; He, Y.; Meng, L.; Huang, T.; Yang, H.; Huang, C. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in remote lakes from the Tibetan Plateau: Concentrations, source, ecological risk, and influencing factors. J. Environ. Manag. 2022, 319, 115689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yunker, M.; Macdonald, R.; Vingarzan, R.; Mitchell, R.H.; Goyette, D.; Sylvestre, S. PAHs in the Fraser River basin: A critical appraisal of PAH ratios as indicators of PAH source and composition. Org. Geochem. 2002, 33, 489–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Wu, J.; Zhao, Z. Spatial and temporal distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in sediments from Poyang Lake, China. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0205484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larsen, R.; Baker, J. Source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in the urban atmosphere: A comparison of three methods. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2003, 37, 1873–1881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Liu, X.; Liu, M.; Chen, X.; Liu, S.; Cheng, L.; Lin, X.; Li, Y. Sources, influencing factors and environmental indications of PAH pollution in urban soil columns of Shanghai, China. Ecol. Indic. 2018, 85, 1170–1180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhou, L.; Xue, N.; Li, F.; Li, Y.; Vogt, R.; Cong, X.; Yan, Y.; Liu, B. Source apportionment of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons in soils of Huanghuai Plain, China: Comparison of three receptor models. Sci. Total Environ. 2013, 443, 31–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalili, N.; Scheff, P.; Holsen, T. PAH source fingerprints for coke ovens, diesel and gasoline engine highway tunnels and wood combustion emissions. Atmos. Environ. 1995, 29, 533–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zakaria, M.; Takada, H.; Tsutsumi, S.; Ohno, K.; Yamada, J.; Kouno, E.; Kumata, H. Distribution of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in rivers and estuaries in Malaysia: A widespread input of petrogenic PAHs. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 1907–1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X. The Jianghuai Canal: A strategic fulcrum for establishing a new water transportation network in Anhui. Transp. Constr. Manag. 2025, 3, 34–37. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Huangshan Bookstore. Zongyang County Yearbook; Huangshan Bookstore: Hefei, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Meng, Y.; Liu, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, T.; Jin, B.; Wang, Q.; Tang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Guo, X.; Zhou, J. A review on occurrence and risk of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in lakes of China. Sci. Total Environ. 2019, 651, 2497–2506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Cai, J.; Li, J.; Wang, Z.; Pei, P.; Zhang, J.; Krebs, P. Characterizing the long-term occurrence of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and their driving forces in surface waters. J Hazard Mater. 2022, 423, 127065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.