Climate Change and the Potential Expansion of Rubus geoides Sm.: Toward Sustainable Conservation Strategies in Southern Patagonia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sampling Area

2.2. Morphological Analysis

2.3. Integrative Molecular Approaches for Genetic Diversity and Paternity in Rubus

2.3.1. DNA Extraction and Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism (AFLP) Procedure

2.3.2. Genetic Diversity Analysis

2.3.3. cpDNA Analysis

2.3.4. Paternity Analysis

2.4. The Potential Distribution Model for Rubus geoides

3. Results

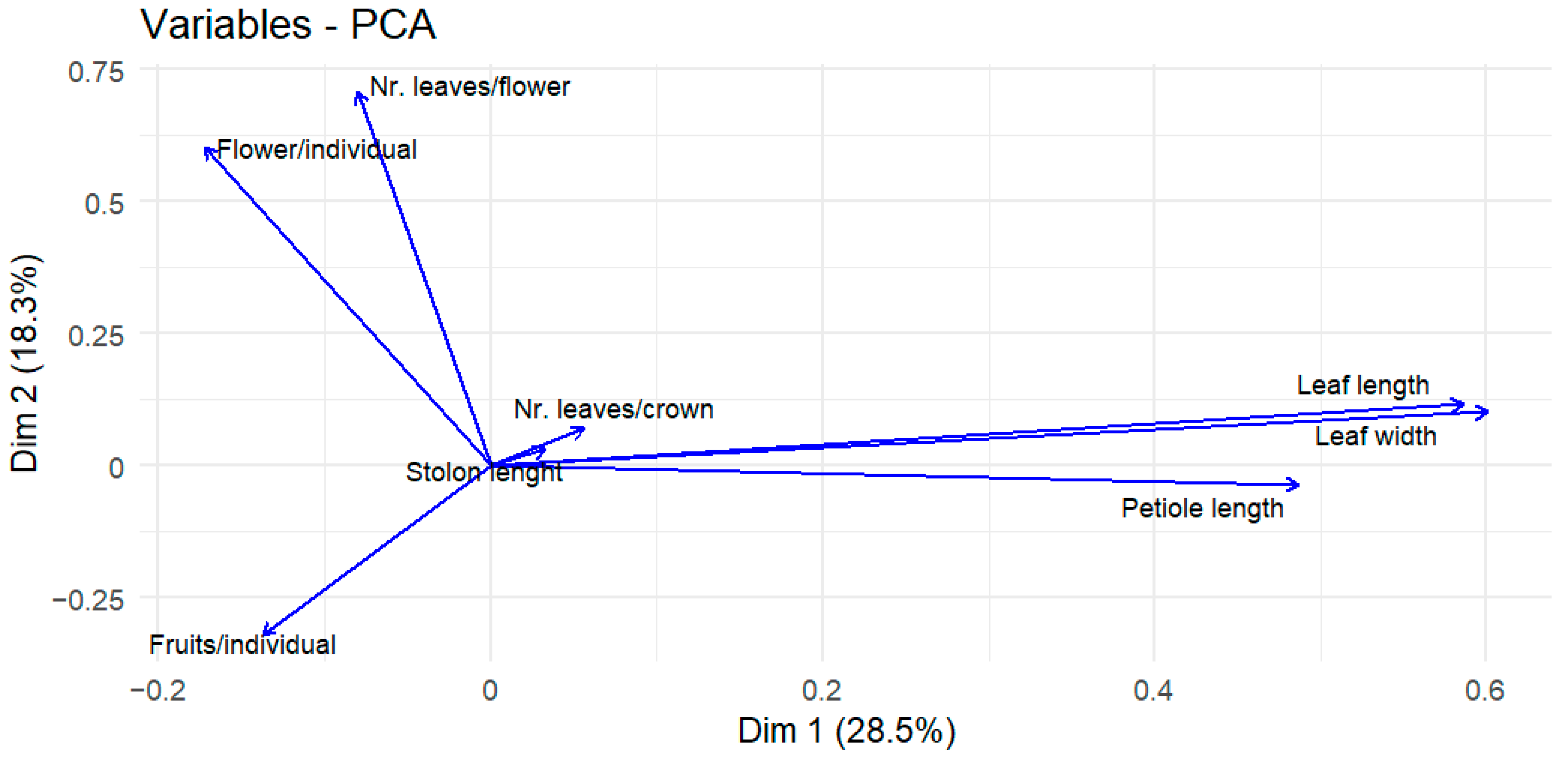

3.1. Morphological Analysis

3.2. Genetic Diversity and Seed-Driven Connectivity in Rubus geoides Populations of Southern Patagonia

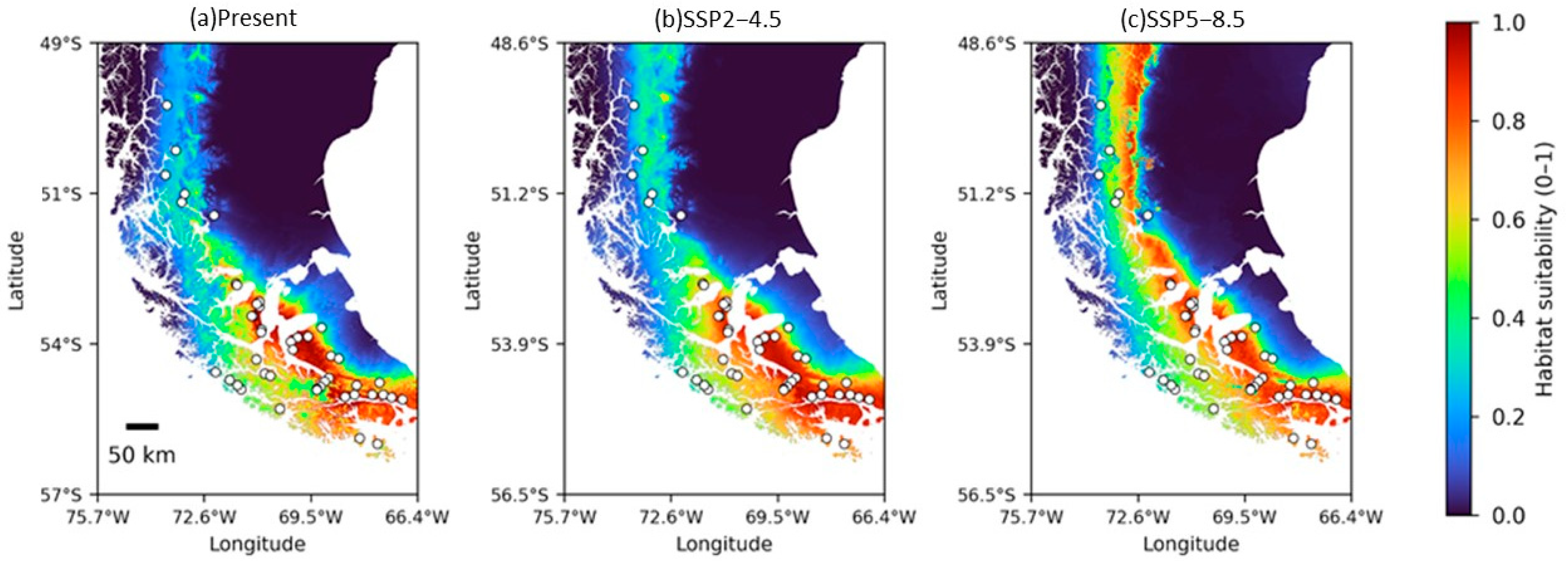

3.3. Potential Distribution Model for 2021–2040

4. Discussion

4.1. Determinants of R. geoides’ Gene Flow in Southern Patagonia

4.2. Past and Future Climatic Influence

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Castellanos, E.; Lemos, M.F.; Astigarraga, L.; Chacón, N.; Cuvi, N.; Huggel, C.; Miranda, L.; Moncassim Vale, M.; Ometto, J.P.; Peri, P.L.; et al. Central and South America. In Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Pörtner, H.-O., Roberts, D.C., Tignor, M., Poloczanska, E.S., Mintenbeck, K., Alegría, A., Craig, M., Langsdorf, S., Löschke, S., Möller, V., et al., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 1689–1816. [Google Scholar]

- Trisos, C.H.; Merow, C.; Pigot, A.L. The projected timing of abrupt ecological disruption from climate change. Nature 2020, 580, 496–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inostroza, L.; Zasada, I.; König, H.J. Last of the wild revisited: Assessing spatial patterns of human impact on landscapes in Southern Patagonia, Chile. Reg. Environ. Change 2016, 16, 2071–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bañados Ortiz, M.P. Frambuesas en Chile: Sus Variedades y Características; Fundación para la Innovación Agraria: Santiago, Chile, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jiménez-Aspee, F.; Theoduloz, C.; Ávila, F.; Thomas-Valdés, S.; Mardones, C.; von Baer, D.; Schmeda-Hirschmann, G. The Chilean wild raspberry (Rubus geoides Sm.) increases intracellular GSH content and protects against H2O2 and methylglyoxal-induced damage in AGS cells. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 908–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uleberg, E.; Trost, K.; Stavang, J.A.; Rothe, G.; Martinussen, I. Evaluation of cloudberry (Rubus chamaemorus L.) clones for selection of high-quality varieties. Acta Agric. Scand. Sect. B-Soil Plant Sci. 2011, 61, 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Moore, D. Flora of Tierra del Fuego; Garden, A.N.M.B., Ed.; Anthony Nelson Ltd.: Shrewsbury, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Sudzuki, F. Cultivo de Frutales Menores; Colección Nueva Técnica; Editorial Universitaria: Santiago, Chile, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Lima, J.S.; Ballesteros-Mejia, L.; Lima-Ribeiro, M.S.; Collevatti, R.G. Climatic changes can drive the loss of genetic diversity in a Neotropical savanna tree species. Glob. Change Biol. 2017, 23, 4639–4650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebel, I.; Gonzalez, I.; Jaña, R. Genetic Approach on Sanionia uncinata (Hedw.) Loeske to Evaluate Representativeness of in situ Conservation Areas Among Protected and Neighboring Free Access Areas in Maritime Antarctica and Southern Patagonia. Front. Conserv. Sci. 2021, 2, 647798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereux, E. Flora del Archipiélago Fueguino; Ed. Gráfica LAF: Ushuaia, Argentina, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pisano, E. Fitogeografía de fuego-patagonia chilena: Comunidades vegetales entre las latitudes 52 y 56° S. An. Inst. Patagon. 1977, 8, 121–250. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.; Glaser, M.; Kilian, R.; Santana, A.; Butorovic, N.; Casassa, G. Weather observations across the Southern Andes at 53° S. Phys. Geogr. 2003, 24, 97–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamora, E.; Santana, A. Características climáticas de la costa occidental de la Patagonia entre las latitudes 46° 40′ y 56° 30′. An. Del Inst. De La Patagon. 1979, 10, 109–144. [Google Scholar]

- Takeda, F.; Strik, B.C.; Peacock, D.; Clark, J.R. Cultivar differences and the effect of winter temperature on flower bud development in blackberry. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2002, 127, 495–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vos, P.; Hogers, R.; Bleeker, M.; Reijans, M.; Vandelee, T.; Hornes, M.; Frijters, A.; Pot, J.; Peleman, J.; Kuiper, M.; et al. AFLP—A new technique for dna-fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 1995, 23, 4407–4414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weising, K.; Nybom, H.; Wolff, K.; Kahl, G. DNA Fingerprinting in Plants Principles, Methods, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Taylor & Francis Group: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2005; p. 427. [Google Scholar]

- Bonin, A.; Bellemain, E.; Eidesen, P.B.; Pompanon, F.; Brochmann, C.; Taberlet, P. How to track and assess genotyping errors in population genetics studies. Mol. Ecol. 2004, 13, 3261–3273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vekemans, X.; Beauwens, T.; Lemaire, M.; Roldan-Ruiz, I. Data from amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers show indication of size homoplasy and of a relationship between degree of homoplasy and fragment size. Mol. Ecol. 2002, 11, 139–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peakall, R.; Smouse, P.E. GenAlEx 6.5: Genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research-an update. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 2537–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlueter, P.M.; Harris, S.A. Analysis of multilocus fingerprinting data sets containing missing data. Mol. Ecol. Notes 2006, 6, 569–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falush, D.; Stephens, M.; Pritchard, J.K. Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: Linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics 2003, 164, 1567–1587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evanno, G.; Regnaut, S.; Goudet, J. Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: A simulation study. Mol. Ecol. 2005, 14, 2611–2620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Earl, D.A.; Vonholdt, B.M. STRUCTURE HARVESTER: A website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv. Genet. Resour. 2012, 4, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roderic, D.M. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2003; pp. 6.2.1–6.2.15. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, T.Y.; Schaal, B.A.; Peng, C.I. Universal primers for amplification and sequencing a noncoding spacer between the atpB and rbcL genes of chloroplast DNA. Bot. Bull. Acad. Sin. 1998, 39, 245–250. [Google Scholar]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M.; Team, U. Unipro UGENE: A unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Higgins, D.G.; Gibson, T.J. CLUSTAL W: Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids. Res. 1994, 22, 4673–4680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swofford, D.L. PAUP* Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (and Other Methods); Version 4; Sinauer As-Sociates: Sunderland, MA, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Librado, P.; Rozas, J. DnaSP v5: A software for comprehensive analysis of DNA polymorphism data. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1451–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ElMousadik, A.; Petit, R.J. Chloroplast DNA phylogeography of the argan tree of Morocco. Mol. Ecol. 1996, 5, 547–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volis, S.; Song, M.S.; Zhang, Y.H.; Shulgina, I. Fine-Scale Spatial Genetic Structure in Emmer Wheat and the Role of Population Range Position. Evol. Biol. 2014, 41, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Excoffier, L.; Smouse, P.E.; Quattro, J.M. Analysis of molecular variance inferred from metric distances among dna haplotypes—Application to human mitochondrial-dna restriction data. Genetics 1992, 131, 479–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhead, M.; McCallum, S.; Smith, K.; Cardle, L.; Mazzitelli, L.; Graham, J. Identification, characterisation and mapping of simple sequence repeat (SSR) markers from raspberry root and bud ESTs. Mol. Breed. 2008, 22, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalinowski, S.T.; Taper, M.L.; Marshall, T.C. Revising how the computer program cervus accommodates genotyping error increases success in paternity assignment. Mol. Ecol. 2007, 16, 1099–1106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phillips, S.J.; Anderson, R.P.; Schapire, R.E. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Model. 2006, 190, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fick, S.E.; Hijmans, R.J. WorldClim 2: New 1-km spatial resolution climate surfaces for global land areas. Int. J. Climatol. 2017, 37, 4302–4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartl, D.; Clark, A. Principles of Population Genetics, 3rd ed.; Sinauer Associates, Inc. Publishers: Sunderland, MA, USA, 1997; p. 542. [Google Scholar]

- Korpelainen, H. Sex-ratios and resource-allocation among sexually reproducing plants of Rubus chamaemorus. Ann. Bot. 1994, 74, 627–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, A.M.; Gomez-Ruiz, P.A.; Pena, J.A.; Uno, H.; Jaffe, R. Wind Speed Affects Pollination Success in Blackberries. Sociobiology 2018, 65, 218–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nybom, H. Active self-pollination and pollen stainability in some Rubus cultivars. J. Hortic. Sci. 1986, 61, 49–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cronquist, A. The Evolution and Classification of Flowering Plants, 2nd ed.; The New York Botanical Garden: Bronx, NY, USA, 1988; p. 535. [Google Scholar]

- Markham, B.J. Reconocimiento faunístico de las áreas de los fiordos Toro y Cóndor, Isla Riesco, Magallanes. An. Del Inst. De La Patagon. 1970, 1, 41–59. [Google Scholar]

- Lynch, M.; Milligan, B.G. Analysis of population genetic-structure with rapd markers. Mol. Ecol. 1994, 3, 91–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butorovic, N. Resumen Metereológico año 2015* Estación “Jorge C. Schythe” (53°08′ S; 70°53′ O; 6 msnm): Metereological Summary year 2015, “Jorge C. Schythe” Station (53°08′ S; 70°53′ O; 6 msnm). An. Inst. Patagon. 2016, 44, 89–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuilleumier, F. Avian biodiversity in forest and steppe communities of chilean Fuego-Patagonia. An. Del Inst. De La Patagonia. 1998, 26, 41–57. [Google Scholar]

- Volis, S.; Zaretsky, M.; Shulgina, I. Fine-scale spatial genetic structure in a predominantly selfing plant: Role of seed and pollen dispersal. Heredity 2010, 105, 384–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovett-Doust, J.; Lovett-Doust, L. Plant Reproductive Ecology: Patterns and Strategies; Lovett-Doust, J., Lovett-Doust, L., Eds.; SERBIULA (sistema Librum 2.0); Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez, N. Plant sexual systems, dichogamy, and herkogamy in the Venezuelan Central Plain. Flora 2005, 200, 30–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez de Paz, J. La biología reproductiva. Importancia y tipos de estudios. In Biología de la Conservación de Plantas Amenazadas; Organismo Autónomo Parques Nacionales: Madrid, Spain, 2002; pp. 72–132. [Google Scholar]

- Gyan, K.Y.; Woodell, S.R.J. Flowering phenology, flower colour and mode of reproduction of Prunus spinosa L. (Blackthorn); Crataegus monogyna Jacq. (Hawthorn); Rosa canina L. (Dog Rose); and Rubus fruticosus L. (Bramble) in Oxfordshire, England. Funct. Ecol. 1987, 1, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nybom, H. Chromosome-numbers and reproduction in Rubus subgen malachobatus. Plant Syst. Evol. 1986, 152, 211–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tammisola, J. Incompatibility classes and fruit-set in natural-populations of arctic bramble (Rubus-arcticus L.) in finland. J. Agric. Sci. Finl. 1988, 60, 327–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haskell, G.; Paterson, E.B. Chromosome Number of a Sub-Antarctic Rubus. Nature 1966, 211, 759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, S. Isolation by distance. Genetics 1943, 28, 114–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindqvist-Kreuze, H.; Koponen, H.; Valkonen, J.P.T. Genetic diversity of arctic bramble (Rubus arcticus L. subsp arcticus) as measured by amplified fragment length polymorphism. Can. J. Bot.-Rev. Can. Bot. 2003, 81, 805–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marulanda, M.L.; Lopez, A.M.; Aguilar, S.B. Genetic diversity of wild and cultivated Rubus species in Colombia using AFLP and SSR markers. Crop Breed. Appl. Biotechnol. 2007, 7, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCulloch, R.D.; Fogwill, C.J.; Sugden, D.E.; Bentley, M.J.; Kubik, P.W. Chronology of the last glaciation in central strait of magellan and bahía inútil, southernmost south america. Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr. 2005, 87, 289–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvill, C.M.; Stokes, C.R.; Bentley, M.J.; Lovell, H. A glacial geomorphological map of the southernmost ice lobes of Patagonia: The Bahia Inutil—San Sebastian, Magellan, Otway, Skyring and Rio Gallegos lobes. J. Maps 2014, 10, 500–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, B.J.; Darvill, C.M.; Lovell, H.; Bendle, J.M.; Dowdeswell, J.A.; Fabel, D.; García, J.L.; Geiger, A.; Glasser, N.F.; Gheorghiu, D.M.; et al. The evolution of the Patagonian Ice Sheet from 35 ka to the present day (PATICE). Earth-Sci. Rev. 2020, 204, 103152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabassa, J. Late Cenozoic Glaciations in Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego. In Late Cenozoic of Patagonia and Tierra del Fuego; Rabassa, J., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2008; Volume 11, pp. 151–204. [Google Scholar]

- Sagredo, E.; Moreno, P.; Villa-Martínez, R.; Kaplan, M.; Kubik, P.; Stern, C. Fluctuations of the Ultima Esperanza ice lobe (52°S), Chilean Patagonia, during the last glacial maximum and termination 1. Geomorphology 2011, 125, 92–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hebel, I.; Rudinger, M.C.D.; Jana, R.A.; Bastias, J. Genetic Structure and Gene Flow of Moss Sanionia uncinata (Hedw.) Loeske in Maritime Antarctica and Southern-Patagonia. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 6, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahokas, H. Artificial hybrid—Rubus chamaemorus (female) × Rubus idaeus cv Preussen. Ann. Bot. Fenn. 1979, 16, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- RejmÁNek, M. Invasion of Rubus praecox (Rosaceae) is promoted by the native tree Aristotelia chilensis (Elaeocarpaceae) due to seed dispersal facilitation. Gayana. Botánica 2015, 72, 27–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith-Ramírez, C.; Vargas, R.; Castillo, J.; Mora, J.; Arellano-Cataldo, G. Woody plant invasions and restoration in forests of island ecosystems: Lessons from Robinson Crusoe Island, Chile. Biodivers. Conserv. 2017, 26, 1507–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Trait | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | PC4 | PC5 | PC6 | PC7 | PC8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leaf length | 0.58579038 | 0.11621487 | 0.08518639 | 0.07921917 | 0.0827973 | 0.3750708 | 0.15557078 | 0.6768128 |

| Leaf width | 0.60068881 | 0.10176556 | 0.07970959 | 0.07185648 | 0.0915439 | 0.28616366 | 0.00157614 | 0.72596648 |

| Petiole length | 0.48658754 | 0.03566475 | 0.13271174 | 0.05394922 | 0.01821023 | 0.83198714 | 0.20587306 | 0.08074493 |

| Flower/individual | 0.17220306 | 0.60374595 | 0.32147963 | 0.03320196 | 0.32337693 | 0.08867873 | 0.62121752 | 0.0551149 |

| Fruits/individual | 0.13751595 | 0.31898653 | 0.65201661 | 0.04135373 | 0.5709221 | 0.03793024 | 0.35214817 | 0.03319778 |

| Stolon length | 0.0332995 | 0.03172979 | 0.42202998 | 0.75429643 | 0.48210031 | 0.1314326 | 0.03298174 | 0.00537726 |

| Nr. leaves/crown | 0.05628016 | 0.07056438 | 0.51099391 | 0.64285101 | 0.56152168 | 0.00852413 | 0.04564571 | 0.00427058 |

| Nr. leaves/flower | 0.0800893 | 0.70895572 | 0.03283851 | 0.02484805 | 0.07861756 | 0.24203275 | 0.64832142 | 0.06473374 |

| ID | Population | N° of Samples | Coordinates | PLP (%) | Hj | NPA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Discordia | 12 | 53°13′60.00″ S–71° 1′0.00″ O | 6.4 | 0.01999 | 3 |

| B | Parrillar | 12 | 53°23′51.90″ S–71°11′44.39″ O | 8.3 | 0.02328 | 1 |

| C | Riesco | 24 | 52°49′47.18″ S–71°41′44.68″ O | 27.5 | 0.04274 | 47 |

| D | Parrillar | 17 | 53°23′56.56″ S–71°14′24.80″ O | 3.9 | 0.00941 | 0 |

| E | Riesco | 23 | 52°51′29.05″ S–71°40′40.72″ O | 3.9 | 0.01196 | 4 |

| F | San Juan | 19 | 53°38′30.46″ S–70°57′25.15″ O | 18.1 | 0.04222 | 28 |

| G | Dorotea | 12 | 51°37′29.33″ S–72°20′33.81″ O | 12.7 | 0.05365 | 4 |

| I | San Juan | 17 | 53°40′58.91″ S–70°58′35.99″ O | 8.3 | 0.03765 | 1 |

| K | Karukinka | 15 | 54° 9′5.77″ S–68°42′55.77″ O | 9.3 | 0.03576 | 0 |

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Pops | 8 | 120.193 | 15.024 | 0.461 | 5% |

| Within Pops | 142 | 1133.343 | 7.981 | 7.981 | 95% |

| Total | 150 | 1253.536 | 8.442 | 100% |

| ID | Population | PPICA | PIP | PIGP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Discordia | 0 | 0.270–0.332 (*E) 0.001–0.047 (*C) | 0.540–0.664 (*E) 0.002–0.094 (*C) |

| B | Parrillar | 0 | 0.175–0.332 (*E) 0.001–0.052 (*C) | 0.349–0.664 (*E) 0.002–0.104 (*C) |

| C | Riesco | 0.508–0.998 | 0–0.161 (*E) | 0–0.322 (*E) |

| D | Parrillar | 0 | 0.292–0.332 (*E) 0.001–0.037 (*C) | 0.585–0.664 (*E) 0.002–0.044 (*C) |

| E | Riesco | 0.999–1.000 | 0 | 0 |

| F | San Juan | 0.020–0.999 | 0.0–0.322 (*E) | 0–0.644 (*E) |

| G | Dorotea | 0 | 0.018–0.327 (*E) 0.006–0.158 (*C) 0–0.180 (*F) | 0.035–0.655 (*E) 0.011–0.381 (*C) 0–0.359 (*F) |

| I | San Juan | 0 | 0.065–0.332 (*E) 0.001–0.162 (*C) 0–0.246 (*F) | 0.0131–0.664 (*E) 0.002–0.323 (*C) 0–0.491 (*F) |

| K | Karukinka | 0 | 0–0.332 (*E) 0.001–0.053 (*C) 0–0.276 (*F) | 0.1–0.664 (*E) 0.002–0.105 (*C) 0–0.555 (*F) |

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Pops | 8 | 9.444 | 1.181 | 0.062 | 6% |

| Within Pops | 9 | 9.500 | 1.056 | 1.056 | 94% |

| Total | 17 | 18.944 | 1.118 | 100% |

| Source | df | SS | MS | Est. Var. | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Among Pops | 4 | 18.205 | 4.551 | 0.134 | 9% |

| Among Indiv | 49 | 87.851 | 1.793 | 0.429 | 29% |

| Within Indiv | 54 | 50.500 | 0.935 | 0.935 | 62% |

| Total | 107 | 156.556 | 1.498 | 100% |

| Populations | Riesco C (a) | Riesco C (b) | Riesco E |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riesco C (a) | 0 | ||

| Riesco C (b) | 1.437 | 0 | |

| Riesco E | 3.334 | 3.402 | 0 |

| Parrillar | 1.670 | 1.975 | 1.468 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Hebel, I.; Jofré, E.; Ulloa, C.V.; González, I.; Jaña, R.; Páez, G.; Cáceres, M.; Latorre, V.; Vera, A.; Bahamonde, L.; et al. Climate Change and the Potential Expansion of Rubus geoides Sm.: Toward Sustainable Conservation Strategies in Southern Patagonia. Sustainability 2026, 18, 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010444

Hebel I, Jofré E, Ulloa CV, González I, Jaña R, Páez G, Cáceres M, Latorre V, Vera A, Bahamonde L, et al. Climate Change and the Potential Expansion of Rubus geoides Sm.: Toward Sustainable Conservation Strategies in Southern Patagonia. Sustainability. 2026; 18(1):444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010444

Chicago/Turabian StyleHebel, Ingrid, Estefanía Jofré, Christie V. Ulloa, Inti González, Ricardo Jaña, Gonzalo Páez, Margarita Cáceres, Valeria Latorre, Andrea Vera, Luis Bahamonde, and et al. 2026. "Climate Change and the Potential Expansion of Rubus geoides Sm.: Toward Sustainable Conservation Strategies in Southern Patagonia" Sustainability 18, no. 1: 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010444

APA StyleHebel, I., Jofré, E., Ulloa, C. V., González, I., Jaña, R., Páez, G., Cáceres, M., Latorre, V., Vera, A., Bahamonde, L., & Yagello, J. (2026). Climate Change and the Potential Expansion of Rubus geoides Sm.: Toward Sustainable Conservation Strategies in Southern Patagonia. Sustainability, 18(1), 444. https://doi.org/10.3390/su18010444