Abstract

This study examines whether historical legal traditions continue to influence contemporary environmental policy and carbon emission outcomes. Using data from the OECD Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework (CAPMF) and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators for 50 countries over 1990–2023, this analysis applies ANOVA and post hoc tests to assess differences in climate policy stringency and CO2 emissions across four major legal families: Common Law, French Civil Law, German Civil Law, and Scandinavian Law. The findings reveal that legal origin significantly affects the stringency of sectoral and cross-sectoral climate policies, particularly after 2006, when international climate commitments intensified. Scandinavian and German Law countries demonstrate stronger adoption of market-based instruments and achieve substantially lower emissions, while Common Law systems display weaker policy stringency and higher CO2 levels. Differences in non-market regulations and international policy measures are statistically insignificant, indicating convergence driven by global governance frameworks. Overall, the results confirm that legal origin remains a meaningful determinant of environmental performance through its impact on institutional design and policy implementation mechanisms. However, in the case of Scandinavian legal origin, it is worth making an adjustment for the composition of the group of countries more than for the legal tradition. This study contributes to the debate on institutional persistence by linking legal heritage to the dynamics of climate governance and decarbonization pathways.

Keywords:

energy; sustainability; CO2 emissions; CAPMF; LULUCF; legal origin; environmental stringency 1. Introduction

The quality of institutions and regulatory frameworks has long been recognized as a crucial determinant of economic and social outcomes. Within this discourse, the Legal Origin hypothesis has gained prominence, suggesting that the historical foundations of legal systems exert enduring effects on institutional design, regulatory effectiveness, and ultimately, national development trajectories. A wide body of literature points to the influence of legal traditions on governance, emphasizing how differences in the nature of law, enforcement mechanisms, and the distribution of political power shape institutional quality [1,2].

Despite the extensive application of the Legal Origin framework to issues of corporate governance, financial markets, and economic regulation, its relevance to policy domains that emerged much later—such as environmental governance—remains debated. Some scholars question whether legal traditions continue to exert influence in modern contexts, where transnational norms, global governance structures, and international agreements increasingly shape domestic policy-making [3,4]. This gap in the literature underscores the need for a systematic investigation into whether, and to what extent, historical legal legacies affect contemporary climate and environmental policies.

We hypothesize that legal origin traditions play a significant role in shaping environmental outcomes across countries. In particular, we expect that nations with different law origins demonstrate systematic differences in the stringency of their climate policies, which in turn influence both the level and trajectory of CO2 emissions. By empirically examining this nexus, our study seeks to contribute to the broader debate on institutional persistence, while also offering insights into the institutional drivers of climate change mitigation.

2. Literature Review

The stringency of regulation and the legal environment in which it is applied are of fundamental importance. Given the operation of equilibrium forces that extend beyond traditional economic markets into political markets, institutional factors largely determine the extent to which regulations are internalized, serve as a stimulus for adaptation or even innovation, or, conversely, become frustrated, degenerating into rent extraction from authority or regulatory self-capture. At the same time, the extent to which a particular legal system shapes the profile of regulations and their functional rigidity remains a widely debated issue. In this context, the Legal Origin approach has gained significant recognition.

With regard to the stringency of environmental regulation, it is evident that climate change compels international organizations and national governments to undertake active measures in the fields of climate policy and environmental protection [5,6,7,8]. Such policies can already be regarded as an integral component of the modern welfare state [9,10,11]. At the same time, the macro- and microeconomic effects of stringent environmental regulation are predominantly analyzed within the framework of the so-called Porter Hypothesis [12]. Broadly understood, the Porter Hypothesis posits that the costs of environmental regulation are offset by benefits arising from firms becoming more innovative and productive. The “weak” version of this hypothesis suggests that well-designed market-based instruments of environmental regulation stimulate innovation [13]. Empirical tests of this hypothesis yield mixed results. Overall, it can be observed that under certain conditions, environmental regulation exerts a positive influence on a range of macro- and microeconomic outcomes [13,14,15]. Benatti et al. (2024) do not confirm the clear superiority of market-based instruments but emphasize that the design of green policies is of crucial importance [16].

In turn, Koziuk et al. (2019) [9,10] demonstrate that the stringency of environmental regulation does not contradict global competitiveness, provided that institutional quality and societal choices enable the internalization of the associated burden. In other words, strong institutional quality makes it possible to reconcile more stringent environmental requirements with competitiveness [9,10]. Fredriksson and Mani (2002) propose a model linking institutional quality and the strictness of environmental regulation [17,18]. On the one hand, higher institutional quality has a positive impact on adopting more stringent approaches to sustainability. On the other hand, firms may become more prone to inducing corrupt behavior. Thus, the quality of institutions determines whether environmental regulation will be effectively implemented or frustrated. Shapiro (2025) emphasizes the existence of a strong link between institutional quality and environmental policy [19]. Sectors that are more sensitive to institutional quality exhibit higher environmental standards; more stringent regulation results in a greater “greenness” of exports; and more complex industries display a stronger dependence on institutional quality in the process of adapting to climate regulation. At the same time, the relocation of polluting industries outside the perimeter of strong institutional quality explains why a higher concentration of emissions is found in poorer countries [19].

The literature on the stringency of environmental regulation suggests that countries may differ in the degree of such stringency, may prioritize more market-oriented or less market-oriented mechanisms, and that institutional quality influences the nature of the corresponding regulatory decisions. The Legal Origin approach is widely applied in analyzing cross-country differences and, potentially, belonging to a particular legal tradition exerts an impact on the stringency of environmental regulation.

The position on the determinative role of legal origin is based on the assumption that the different historical trajectories of legal families are still relevant today. Significant differences in the political circumstances of the emergence and development of such traditions led to the emergence of English Common Law, French codified Civil Law, German and Scandinavian Civil Law, which have features of the previous two. There are also socialist law, Islamic law, and Chinese law, but they are largely ignored in the literature on Legal Origin [2,20,21].

The idea of the importance of law for economic development goes back to Hayek (1960) [22]. Pistor (2006) shows that the very fact of what can be contracted and how contractual relations are regulated reflects the fact that law is a way of allocating political power [1]. According to Pistor (2006) [1], the nature of the legal tradition determines whether an economy will be a “liberal market economy” (LME) or a “coordinated market economy” (CME), since the law is a “coordinated device for social preferences”. In a broader sense, the law will determine the distribution of power between the state and the individual and how policy is implemented through law [1,2]. So, the legal origin is associated with deeper processes of economic systems evolving and distribution of political power in society [1,2].

However, La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes & Shleifer (2008) present more narrowly the areas where differences in legal origin are manifested [2]. They highlight procedural formalism, judicial independence, market entry regulation, media control, military conscription, labor law, corporate and securities law, bankruptcy regulation, and government ownership of banks. In line with the views expressed by the authors [2], legal origin is regarded as a significant factor, given extensive historical evidence indicating its influence on whether a country is inclined to undertake regulatory interventions and on the specific modalities through which such interventions are implemented.

Significant number of papers provide empirical evidence that English Common Law better protects property rights, is more substantive and less formalistic, more adaptive, supports judicial independence, and is generally more oriented toward freedom of contracts, thus being more market-friendly. In particular, La Porta et al. [2,21,23,24,25,26,27,28,29] and Armour et al. (2009) [30] show that better protection of shareholder rights leads to higher stock market capitalization. Protecting creditors’ rights leads to greater credit depth [31]. More efficient governance and less formalism improve market dynamism [20,29]. A more independent judiciary contributes to the rule of law [23].

Thus, the literature on Legal Origin indicates substantial differences in how legal traditions shape subsequent economic processes. Building on the analytical framework of this approach, it may be hypothesized that Legal Origin constitutes a significant factor determining cross-country variation in environmental regulation and the green transition. In particular, it appears logical to assume that a system of Common Law, being more oriented toward the protection of individual rights from government dominance, corresponds to a lighter regulatory burden or lower stringency of environmental regulation. Similarly, it can be assumed that the greater tolerance of Common Law for market mechanisms implies a stronger preference for market-based instruments of environmental regulation over non-market ones in countries belonging to this legal tradition. This assumption finds empirical support in a number of studies. Fredriksson & Wollscheid (2015) [32], using a sample of 109 postcolonial countries, demonstrate that Civil Law countries adopt more stringent climate policies compared to Common Law countries. With some modifications to the sample and estimation methods, Fredriksson & Wollscheid (2018) confirm these earlier findings [33].

Thus, it has become almost conventional wisdom that Legal Origin affects both the quality of regulation and the quality of institutions through a set of complex mechanisms related to the nature of law (see Appendix A), the procedures of its enforcement, and the ways in which legal traditions shape the distribution of political power [1,2]. Nevertheless, it remains a subject of debate whether all policies that emerged long after the distinct differences between legal systems had been established are equally subject to the influence of Legal Origin [3,4].

Without rejecting the validity of the results obtained by Fredriksson & Wollscheid [32,33], it can be hypothesized that the relationship between Legal Origin and both the degree of stringency and the nature of environmental regulation may be more complex. On the one hand, the theory of legal diffusion suggests that Legal Origin is not the sole channel through which regulatory norms spread. Legal diffusion occurs through processes such as following a leader in a particular area of regulation, the influence of international organizations, regional integration, and global or regional convergence [34,35,36,37,38]. In cases of leader-following, the benefits of economic interaction with the leader shape the adoption of legal norms, in a manner analogous to gravity models of trade [36]. In turn, in the case of central bank reforms, a number of studies indicate that legislative changes in many countries have been driven by the influence of international organizations, membership in monetary unions, and peer pressure [39,40,41]. For instance, membership in the European Union requires convergence in the legal regime governing environmental protection and the green transition.

On the other hand, it is important to distinguish between the content of law arising from differences in legal tradition and the content of law regulating specific socio-economic activities. This thesis may be grounded in several observations indicating that belonging to a particular legal tradition affects economic processes primarily in areas related to property rights. In other words, the consequences for economic processes of how such rights are protected at both the fundamental and procedural levels have long been shaped by Legal Origin. However, Legal Origin appears to be a less decisive factor when it comes to policies that have emerged more recently. Bradford et al. (2021) show that belonging to either the Common Law or Civil Law tradition has a significant effect on the similarity of countries’ legal regimes for property rights protection and antitrust policy [37]. Put differently, Legal Origin explains the divergence in property rights regimes across Common Law and Civil Law countries, whereas in the case of antitrust regulation this distinction is far less pronounced. Bradford et al. (2021) conclude that the later a policy emerges, the weaker its dependence on legal tradition [37]. Oto-Peralies & Romero-Ávila (2017) follow a somewhat different line of reasoning, arguing that structural reforms substantially reduce regulatory divergence between countries belonging to different legal families, with the most pronounced formal changes occurring where the initial level of regulation was lower [42]. Investor and creditor protection as well as the quality of corporate governance serve as illustrative examples [42]. By contrast, Mutarindwa et al. (2021) do not confirm the significance of reform as a factor [43]. Examining 40 African countries, they show that formal indicators of investor and creditor protection still differ across Legal Origin, with the mode of colonization continuing to shape cross-country heterogeneity. According to Acemoglu et al. [44,45] and Acemoglu & Robinson (2005) [46], the mode of colonization is the most important factor embedding differences in institutional development trajectories, which may also prove relevant for the character of regulation.

However, as evidenced by the conclusions of Bradford et al. (2021) [37], the more recent the regulation, the less dependent it is on Legal Origin. The argument of Bradford et al. (2021) regarding the stronger significance of belonging to the Common Law or Civil Law tradition in the domain of property rights than in policy domains finds indirect confirmation in the analysis of how firms adhere to ESG guidelines [37]. Becchetti et al. (2020) show that firms from Common Law countries perform better in corporate governance and community engagement, while firms from Civil Law countries demonstrate significantly stronger outcomes in the field of human resources [47]. By contrast, legal tradition does not exert a substantial influence on the extent to which firms comply with sustainability standards. Kurbus & Rant (2025), in turn, argue that sectoral regulation exerts a greater impact on the homogeneity of ESG reporting among firms from Civil Law countries, whereas firms from Common Law countries tend to be more flexible and less burdened by formal reporting procedures [48]. The findings of Becchetti et al. (2020) [47] and Kurbus & Rant (2025) [48] suggest that legal formalism, codification, and other factors shaped by Legal Origin do matter, yet not to an extent sufficient to determine issues that may be classified as new policies. This provides further support for Bradford et al. (2021) contention that Legal Origin is not a decisive factor when it comes to newly emerging policies [37].

From a theoretical standpoint, legal origin influences environmental policy implementation primarily through its institutional and regulatory characteristics. The Legal Origins Theory argues that different legal traditions, most notably Common Law and Civil Law, embed distinct approaches to regulation, enforcement, and the role of the state. These structural differences shape how environmental policies are formulated, adopted, and enforced (Table 1).

Table 1.

Institutional and regulatory characteristics of environmental policy implementation.

Overall, as the foregoing review of the literature indicates [2,23,24,25,26,27,28,29], the transmission mechanism linking legal traditions to regulatory decisions and their outcomes remains largely situated within theoretical and historical debates. It is currently understood that Common Law countries possess stronger enforcement mechanisms, exhibit more independent judiciaries, and provide greater protection of property rights. These features may, ceteris paribus, allow for more lenient environmental regulation and, consequently, relatively higher CO2 emissions. However, insofar as regulations are implemented in Common Law countries, the quality of administrative enforcement is theoretically expected to be higher.

Legal origin influences environmental policy implementation by shaping the institutional context in which regulation is designed and enforced. Common Law traditions tend to produce fewer but more effectively enforced regulations, while Civil Law traditions support broader regulatory intervention but may face challenges in consistent and stringent enforcement. These foundational differences affect not only the ambition of environmental policies but also their practical outcomes.

Building on this, the basic hypothesis of this study is that the stringency of environmental regulation is not directly associated with belonging to a particular legal tradition. Countries differing in terms of Legal Origin are, in fact, relatively close in their policy approaches to sustainability, environmental requirements, and the green transition. Instead, formal statistical differences across English Common Law, French Civil Law, German Civil Law, and Scandinavian Law are largely driven by the composition of the groups, where the green priorities of a critical mass of countries influence the aggregate measure of regulatory stringency [20,49]. At the same time, this hypothesis does not exclude the possibility that the preference for market-based versus non-market instruments may still be shaped by Legal Origin.

In our study we tasted few hypothesis: (1) Legal Origin is associated with stringency because different instruments of environment regulation manifest themselves differently in certain groups of countries (for example, countries with English Common Law are more market-based); (2) environment regulation as a new policy may not be so strictly conditioned by Legal Origin, and therefore it is better to replace causality of relationships with association. We hypothesize also that Legal Origin traditions play a significant role in shaping environmental outcomes across countries. In particular, nations with different Legal Origin are expected to show systematic differences in the stringency of their climate policies, which in turn affect the level and trajectory of CO2 emissions [50,51,52,53].

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Data Sources

This study combines information on environmental policies and carbon emissions from two main sources. First, data on stringency of climate mitigation policies were obtained from the OECD’s Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework (CAPMF), which represents the most extensive internationally harmonized database on climate action. The CAPMF, developed under the International Programme for Action on Climate, records 130 individual policy variables grouped into 56 categories of climate actions and policies. The dataset spans the period 1990–2023 and covers 51 OECD and partner countries, along with the European Union as a single entity [54].

Policy stringency is defined as the degree to which climate actions and policies incentivize or enable GHG emissions mitigation at home or abroad. sectoral, cross-sectoral, international stringency indices are built by summing up these policy-specific stringency levels [55].

Data on CO2 emissions were retrieved from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (WDI). This database provides 16 time series on carbon dioxide emissions, allowing for the analysis of both levels and dynamics of emissions across countries and over time [56]. Considering that absolute emission levels vary greatly depending on countries’ economic development and size, the analysis focuses on indicators “Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (total) excluding LULUCF (Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry) (% change from 1990)” and “Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (total) excluding LULUCF per capita (t CO2e/capita)”.

3.2. Variables

Independent variable—Legal tradition (categorical), classified into four groups: Common Law, French Civil Law, German Civil Law, and Scandinavian Law.

Dependent variables:

- Environmental policy stringency (derived from CAPMF composite indicators).

- Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (from WDI).

3.3. Country Classification

Countries in the sample were classified according to their legal origins, following the widely used categorisation in comparative law and economics [54,55,56]. This classification enables the assessment of whether systematic institutional differences are associated with distinct environmental policy trajectories and emission outcomes.

3.4. Statistical Techniques

The empirical strategy combines descriptive and econometric methods:

- Descriptive analysis was used to identify temporal trends and cross-country patterns in environmental policy stringency and CO2 emissions.

- ANOVA and post hoc LSD (Least Significant Difference) tests were applied to compare group means across legal traditions and assess statistical significance of observed differences.

4. Results

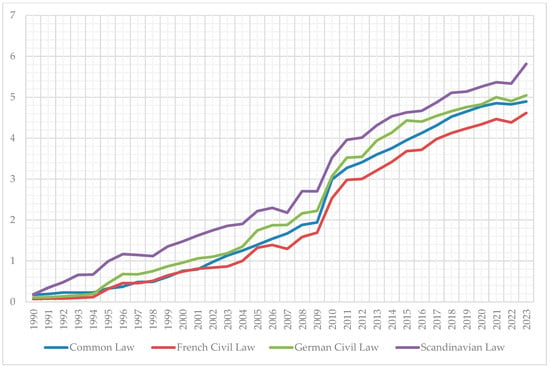

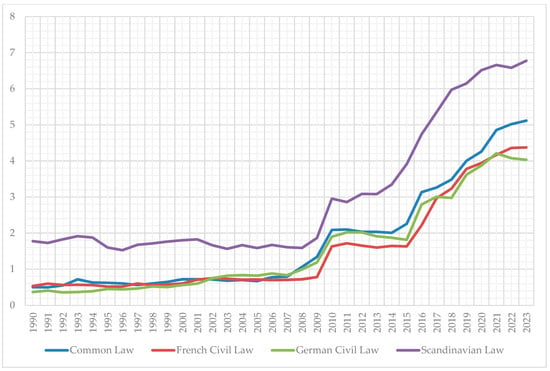

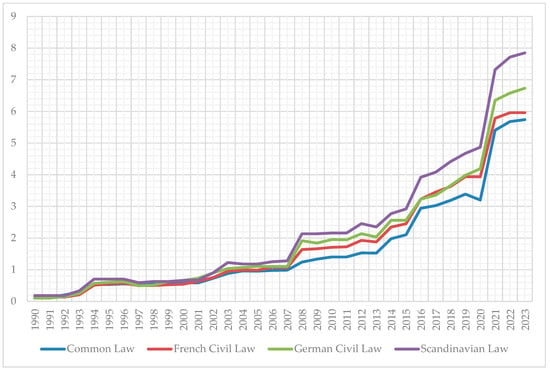

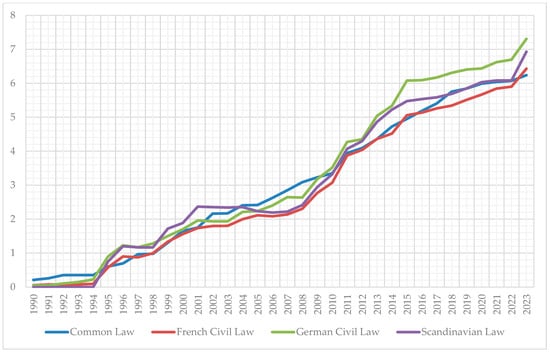

Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3 show that environmental policy stringency increases over the entire period of observation for all country groups classified by legal tradition.

Figure 1.

Trends in Sectoral Environmental Policy Stringency across countries’ legal origin. Source: own compilation based on [54,55,56].

Figure 2.

Trends in Cross-Sectoral Environmental Policy Stringency across countries’ legal origin. Source: own compilation based on [54,55,56].

Figure 3.

Trends in International Environmental Policy Stringency across countries’ legal origin. Source: own compilation based on [54,55,56].

It is evident that Scandinavian countries exhibit the highest stringency levels across all types of environmental policy (sectoral, cross-sectoral and international). A visual inspection of the graphs also indicates differing degrees of cross-group heterogeneity in environmental policy stringency across policy types. This heterogeneity is greatest for cross-sectoral environmental policy and lowest for international policy. It is also worth noting a tendency towards divergence in environmental policy stringency in recent years, particularly for sectoral and cross-sectoral measures.

For international climate policy, the trajectories show similarities across all legal origins. This suggests that participation in international agreements (such as the Kyoto Protocol or the Paris Agreement) has harmonized policy commitments, reducing the influence of domestic legal institutions on this specific dimension of climate governance. Still, Scandinavian countries tend to appear slightly more engaged, while Common Law countries remain on the lower side of the distribution (Figure 3).

The data presented in Table 2 statistically confirm the patterns that emerge from the graphical analysis. Specifically, they show that country groups with different legal traditions differ significantly in terms of mean levels of cross-sectoral stringency and post-2010 sectoral stringency. The stronger statistical results (alongside the partial divergence of the curves in Figure 1, Figure 2 and Figure 3) suggest that institutional divergence becomes more salient in the era of intensified climate commitments.

Table 2.

One-way ANOVA results for sectoral, cross-sectoral, and international policy stringency by legal origin.

The post hoc comparisons further illustrate the statistical significance of differences across legal traditions (Table 3). Scandinavian countries differ significantly from all other groups in terms of cross-sectoral stringency over the entire observation period, and from Common Law and French Law countries in terms of sectoral stringency in the most recent years. These results indicate that institutional heritage may partially explain differences in the ambition of environmental policy across legal families, although it should be noted that not all inter-group contrasts are statistically significant.

Table 3.

Post hoc LSD test for sectoral and cross-sectoral policy stringency by legal origin.

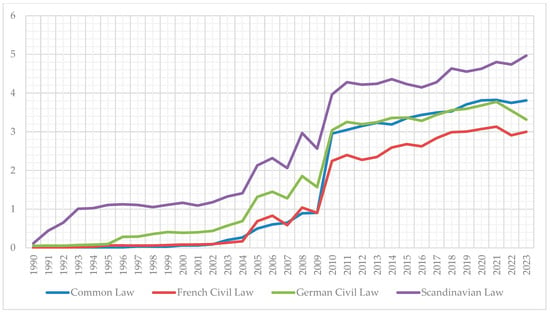

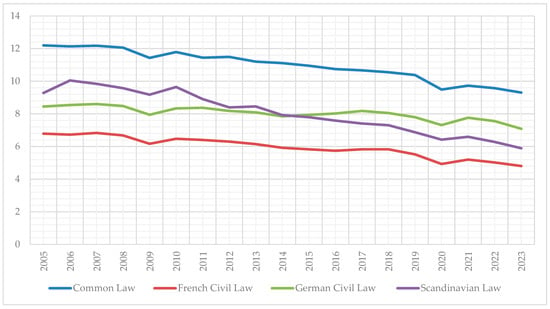

The dynamics of the stringency of market- and non-market-based instruments within sectoral policies are depicted in Figure 4 and Figure 5. Market-based tools—including carbon and fuel taxes, emissions trading systems and fossil fuel subsidy reforms, among others (see Appendix B for the full list of instruments)—are adopted earlier and at higher stringency levels in countries with Scandinavian and German legal origins, while French and Common Law systems expand these instruments more gradually. By contrast, non-market instruments (standards, bans and other regulatory measures) display smoother trajectories and less pronounced divergence across legal families, with most groups strengthening such measures over time.

Figure 4.

Trends in the stringency of market-based instruments within sectoral environmental policy across countries’ legal origin. Source: own compilation based on [54,55,56].

Figure 5.

Trends in the stringency of non-market instruments within sectoral environmental policy across countries’ legal origin. Source: own compilation based on [54,55,56].

Figure 4 highlights pronounced institutional divergence in the use of market-based instruments. Scandinavian countries demonstrate strong and accelerating stringency of Market-Based Instruments (MBIs) from the 1990s onwards, reflecting institutional preferences for economic instruments. The trajectory of MBI stringency in German Law countries is very similar in shape to the Scandinavian one but evolves at a substantially lower level; moreover, following the end of the 2007–2009 economic crisis it almost fully converges with the trajectory observed for Common Law countries.

The trajectories for non-market instruments are less differentiated across legal traditions (Figure 5). All groups exhibit moderate, relatively smooth growth over time, without major fluctuations, with German and Scandinavian systems being somewhat more consistent in maintaining higher levels of regulatory standards and direct controls in recent years.

The ANOVA results reveal a strong legal-origin effect for market-based instruments but not for non-market ones (Table 4). This suggests that institutional structures play a greater role when environmental policy goals are pursued by changing economic incentives (for example, through environmental taxes or emissions trading schemes), whereas direct regulatory requirements tend to be implemented in a broadly similar way across different legal families. Post hoc tests confirm that the Scandinavian system is significantly different from the others in its use of market-based instruments (Table 5). By contrast, differences in the use of non-market instruments are statistically insignificant, indicating broad convergence.

Table 4.

One-way ANOVA results for market-based and non-market-based instruments of sectoral policies by legal origin.

Table 5.

Post hoc LSD test for market-based and non-market-based instruments of sectoral policies by legal origin.

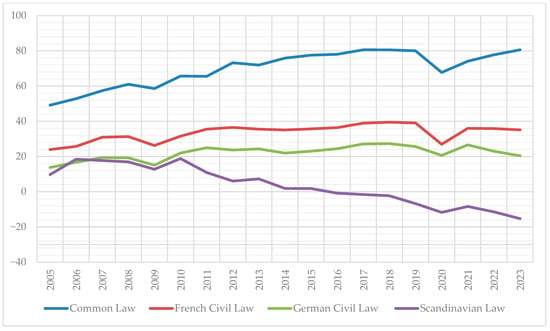

A strong divergence in the trajectories of the percentage change in total carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions excluding LULUCF, relative to 1990 levels, emerges across legal origins (Figure 6). Common Law countries show an overall increase in total emissions since 1990, with only modest growth up to around 2017 and a subsequent period of relative stabilization. French and German Law countries display a broadly similar dynamic, but at substantially lower levels of this emissions indicator. In contrast, Scandinavian Law countries have experienced a steady decline in CO2 emissions since 2010.

Figure 6.

Trends in the Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (total) excluding LULUCF (% change from 1990) across countries’ legal origin. Source: own compilation based on [54,55,56].

The time series in Figure 7 illustrates the dynamics of total CO2 emissions per capita. Common Law countries are characterized by the highest per capita emission levels, albeit with a downward trend. The trajectories for the other legal groups are similar in shape but lie considerably lower. Per capita emissions in Scandinavian and German Law countries are lower than in Common Law countries, while the lowest levels are observed in French Law countries.

Figure 7.

Trends in the Carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions (total) excluding LULUCF per capita (t CO2e/capita) across countries’ legal origin. Source: own compilation based on [54,55,56].

The ANOVA results for emissions are striking—legal origin explains a very large share of the variation in both total and per capita CO2 emissions (Table 6). The F-statistics are extremely high, indicating that group differences are systematic rather than random.

Table 6.

One-way ANOVA results for CO2 emissions (total and per capita) excluding LULUCF by legal origin.

The post hoc analysis shows that all pairs of legal traditions differ significantly in terms of total emissions (Table 7). For per capita emissions, the Scandinavian and German groups are closer to each other but remain significantly distinct from Common Law and French Law countries. Taken together, these results highlight that institutional divergence is reflected not only in the intensity of environmental policy stringency but is also associated with measurable differences in environmental outcomes.

Table 7.

Post hoc LSD test for CO2 emissions (total and per capita) excluding LULUCF by legal origin.

5. Discussion

The results provide compelling evidence that legal origin exerts a systematic influence on environmental policy stringency and CO2 emission outcomes. Although the overall hypothesis anticipated limited persistence of legal origin effects in recently emerged policy domains, the findings reveal nuanced patterns of institutional divergence. The results demonstrate that legal origin continues to shape environmental policy frameworks, particularly in the design and implementation of market-based instruments. This suggests that historical legal traditions still affect how states internalize environmental externalities through taxation, emission trading, and other economic tools.

The statistical significance of differences across legal families—most notably between Scandinavian and Common Law systems—indicates that institutional heritage remains a key determinant of regulatory ambition. The Scandinavian and German Law countries consistently display higher stringency in sectoral and cross-sectoral policies, corroborating prior studies linking coordinated legal systems with stronger collective regulatory approaches [9,18,32]. Conversely, Common Law countries exhibit lower levels of policy stringency and higher CO2 emissions, confirming that more market-oriented legal traditions may favor flexibility and self-regulation over direct intervention.

Interestingly, international policy stringency does not vary significantly across legal origins, implying that global governance frameworks—such as EU directives, UNFCCC commitments, and OECD coordination—contribute to convergence in transnational climate action. This supports the argument advanced by Bradford et al. (2021) [37] that the more recent and internationally diffused a policy area, the weaker its dependence on historical legal traditions. However, the persistence of divergence in domestic and sectoral measures highlights that formal convergence does not automatically translate into uniform implementation.

The results for CO2 emissions reinforce the institutional channel through which legal origin operates. Countries belonging to German and Scandinavian legal families demonstrate significantly lower total and per capita emissions, suggesting that their legal and administrative systems are better equipped to decouple economic growth from carbon intensity. In contrast, the persistently higher emissions in Common Law systems point to the challenges of relying on decentralized, market-driven policy instruments for achieving systemic environmental outcomes. In general, in the case of Scandinavian legal origin, it is worth making an adjustment for the composition of the group of countries more than for the legal tradition. However, it is possible that it is in the Scandinavian countries that the regional factor may play a greater role due to the interpretation of the environmental dimension of the welfare state [9].

Overall, the evidence suggests that legal origin continues to shape environmental policy and performance, albeit selectively. It matters most where institutional architecture and administrative coordination are essential for policy execution, such as in the adoption of fiscal or market-based mechanisms. While globalization and international policy diffusion have reduced the salience of legal origin for some regulatory domains, its legacy remains embedded in national institutional logics. Future research should examine the mediating role of political economic factors, such as energy dependence, fiscal decentralization, and policy diffusion networks, to identify the pathways through which legal traditions translate into divergent environmental outcomes.

6. Limitations and Further Research

It should be noted that several effects stemming from international commitments may automatically homogenize environmental policy, regardless of differences in domestic legal frameworks. For instance, the authors [37] identify the so-called “Brussels Effect”, which refers to the European Union’s ability to unilaterally shape global regulatory standards through the extraterritorial reach of its internal rules, that is, EU norms become de facto global standards even in the absence of international agreements or coercive enforcement. This occurs due to a combination of factors, the most important of which are as follows: the EU represents a large and attractive market, and firms wishing to operate within it are compelled to comply with its stringent rules; companies tend to prefer a single global standard rather than maintaining multiple production or compliance systems; and EU regulations are typically strict, detailed, and strongly protection-oriented (e.g., data protection, chemical safety, environmental standards). Through the “Brussels Effect”, EU environmental norms, such as emissions standards, chemical safety requirements, renewable energy regulations, and non-financial reporting rules, can influence global supply chains, the environmental practices of multinational corporations, and domestic regulations in non-EU countries. Consequently, even states with differing legal traditions may adopt EU-like standards primarily due to market-driven incentives.

Additionally, the influence of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), which serves as the foundational international treaty governing global climate policy [57,58], may be further examined. Its impact manifests through norm-setting (establishing global expectations for climate action), institutional processes (negotiations within the Conference of the Parties), binding and non-binding agreements (the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement), as well as capacity-building and financing mechanisms aimed at supporting mitigation and adaptation measures. Although legal systems are assumed to shape institutional capacity and administrative governance styles, UNFCCC mechanisms can: (1) compensate for or overcome weaknesses in national institutions by introducing external accountability; (2) harmonize climate regulations across countries with different legal traditions; (3) motivate climate action even in jurisdictions where regulatory enforcement has traditionally been weaker.

It should also be noted that the strong effects, whereby legal origin explains a significant share of the variance in both total and per capita CO2 emissions, do not, on their own, establish whether legal traditions exert a direct influence on emissions outcomes or whether their effect operates indirectly through environmental policy stringency. The current ANOVA results capture only between-group differences and therefore cannot disentangle these causal pathways.

Intersection of legal origins and level of development is also important area of further improvement of our understanding the transmission mechanisms between institutional path and regulatory perimeter, scope and intensity, for example, in environmental protection field.

7. Conclusions

The legal origin approach stresses that legal traditions with stronger administrative coordination (German, Scandinavian) are reluctant to implement market-based instruments, while Common Law systems appear more likely to adopt such measures. This aligns with existing theories of comparative institutional economics, which emphasize the influence of legal frameworks on policy preferences. The results of this paper provide robust evidence for legal origin shaping environmental policy outcomes. Countries classified under German and Scandinavian law traditions demonstrate significantly higher levels of policy stringency, particularly in sectoral and cross-sectoral areas, compared to Common and French law systems. These findings are in line with the idea that institutional traditions play a central role in determining policy design and enforcement. The distinction between market-based and non-market instruments is important for the analysis of environmental policy in terms of the legal origins approach. Common Law countries demonstrate more moderate visions of environmental regulation compared to Scandinavian and German law countries groups.

By contrast, international policy stringency appears to be less affected by legal origin. This is likely due to the binding nature of international agreements, which reduce institutional discretion and push countries towards more convergent behavior. It is clear that the stringency of environmental regulation is correlated, evolving over time.

We also see that the more market-oriented Common Law approach corresponds to higher emissions, but there is no clear pattern regarding the severity of regulation. In general, the traditional division into four legal families works somewhat differently in the case of environmental regulation than how it works in finance research, meaning that (a) the legal families country grouping may be undermined by the level of development and welfare state attitudes (e.g., as in case of Nordic vs. French civil law countries); (b) Common Law countries are not among the leaders of liberal environmental regulation, instead leading in emissions, demonstrating softer stringency compared to the Scandinavian and German law groups; (c) the correlation of environment protection actions may indicate patterns of legal diffusion and international peer pressure, etc.

The results for CO2 emissions confirm that institutional differences translate into tangible environmental outcomes. Legal traditions strongly associated with stricter climate policy (German and Scandinavian law) are also linked to lower aggregate and per capita emissions. Conversely, Common Law countries show weaker policy responses and significantly higher emissions trajectories.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, V.K. and Y.H.; methodology, V.K., O.D. and A.S.; software, O.D., T.W. and A.S.; validation, V.K., Y.H. and O.D.; formal analysis, V.K., Y.H. and O.D.; investigation, V.K. and Y.H.; resources, V.K., O.D. and T.W.; data curation, V.K., Y.H. and O.D.; writing—original draft preparation, V.K. and Y.H.; writing—review and editing, O.D., T.W. and A.S.; visualization, O.D., T.W. and A.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the OECD Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework (CAPMF) at https://www.oecd.org/en/data/insights/data-explainers/2025/04/the-climate-actions-and-policies-measurement-framework-capmf.html, and the World Bank’s World Development Indicators at https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 25 October 2025). These data were derived from the following resources available in the public domain: OECD—https://www.oecd.org/en (accessed on 25 October 2025); World Bank—https://databank.worldbank.org (accessed on 25 October 2025).

Acknowledgments

The research was conducted within the framework of the Erasmus + KA2 project SUSTED “Education for Sustainable Development: Synergy of Competences for the Recovery of Ukraine”(101178414-SUSTED).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Legal Origin Countries’ Classification

Table A1.

Countries grouping according to Legal Origin.

Table A1.

Countries grouping according to Legal Origin.

| English Common Law | French Civil Law | German Civil Law | Scandinavian Law |

|---|---|---|---|

| UK Irland Canada US Australia New Zealand India South Africa Saudi Arabia Israel | France Spain Portugal Italy Netherlands Belgium Luxemburg Switzerland Estonia Latvia Lithuania Romania Greece Turkey Russia Indonesia Mexico Costa Rica Columbia Peru Brazil Chile Argentina Malta | Germany Poland Austria Czech Republic Slovak Republic Hungary Bulgaria Slovenia Croatia China Korea Japan | Norway Sweeden Finland Denmark Iceland |

Note: The sample is based on the classical classification [2]. The analysis also incorporates data for Malta (French Civil Law) and Bulgaria (German Civil Law).

Appendix B. Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework

The Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework (CAPMF) is a harmonized, structured database on climate-mitigation policies. Its purpose is to assist countries in designing and implementing climate action, including the fulfillment of their nationally determined contributions (NDCs) and the transition towards global net-zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions around the middle of the century. Developed within the International Programme for Action on Climate (IPAC), the CAPMF contains 128 policy variables that are organised into 56 policy instruments and other climate-related measures (hereafter referred to as “policies”), and it covers 52 IPAC member countries over the period 2000–2020 [55]. The framework classifies policy information along two main dimensions. First, it distinguishes between sector-specific, cross-sectoral and international climate actions and policies. Second, sectoral policies groups are measured by policy type: market-based instruments and non-market instruments.

Table A2.

Sectoral policies [55].

Table A2.

Sectoral policies [55].

| Sector | Market-Based Instruments | Non Market-Based Instruments |

|---|---|---|

| Electricity |

|

|

| Transport |

|

|

| Buildings |

|

|

| Industry |

|

|

| Agriculture |

|

|

| LULUCF |

|

|

| Waste |

|

|

Table A3.

Cross-sectoral policies [55].

Table A3.

Cross-sectoral policies [55].

GHG emission targets

|

Public RD&D expenditure

|

Fossil fuel production policies

|

Climate governance

|

Climate finance

|

Table A4.

International policies [55].

Table A4.

International policies [55].

International co-operation

|

International public finance

|

GHG emissions data and reporting

|

Note: LULUCF—Land use, land use change and forestry; ETS—Emissions trading system; FFS—Fossil fuel support; RES—Renewable energy sources; FiT—Feed-in-tariff; RPS—Renewable Portfolio Standard; EE—Energy efficiency; ICE—Internal combustion engine; MEPS—Minimum energy performance standard; CCS—carbon capture and storage.

References

- Pistor, K. Legal ground rules in coordinated and liberal market economies. In Corporate Governance in Context: Corporations, States, and Markets in Europe, Japan, and the US; Hopt, K.J., Wymeersch, E., Kanda, H., Baum, H., Eds.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2006; pp. 3–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A. The Economic Consequences of Legal Origins. J. Econ. Lit. 2008, 46, 285–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, R.G.; Zingales, L. The Great Reversals: The Politics of Financial Development in the Twentieth Century. J. Financ. Econ. 2003, 69, 5–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roe, M.J. Juries and the Political Economy of Legal Origin. J. Comp. Econ. 2007, 35, 294–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Xu, X. Green finance and energy efficiency improvement: The role of green innovation and industrial upgrading. Innov. Green Dev. 2025, 4, 100200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R. Socioeconomic challenges and its inhabitable global illuminations. Socecon. Chall. 2017, 1, 81–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sotnyk, I.; Wenjuan, D.; Chortok, Y.; Yevdokymov, A.; Yang, Y. Enhancing efficiency and sustainability: Green energy solutions for water supply companies. Ekon. Rozvyt. Syst. 2024, 6, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Wong, W.-K.; Wang, Z.; Albasher, G.; Alsultan, N.; Fatemah, A. Emerging pathways to sustainable economic development: An interdisciplinary exploration of resource efficiency, technological innovation, and ecosystem resilience in resource-rich regions. Resour. Policy 2023, 85, 103747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koziuk, V.; Dluhopolskyi, O.; Hayda, Y.; Ivashuk, Y.; Shymanska, O.; Voznyi, K.; Dluhopolska, T. The Ecological Dimension of the Welfare State: Monograph; Kozyuk, V., Ed.; Lira-K: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2019; 224p, Available online: https://dspace.wunu.edu.ua/handle/316497/36455 (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Koziuk, V.; Dluhopolskyi, O.; Hayda, Y.; Klapkiv, Y. Does education quality drive ecological performance? Case of high and low developed countries. Glob. J. Environ. Sci. Manag. 2019, 5, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markina, L.; Kovach, V.; Vlasenko, O. Analysis of the world market of waste management. Technol. Audit Prod. Reserves 2024, 3, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatti, N.; Groiss, M.; Kelly, P.; Lopez-Garcia, P. Environmental regulation and productivity growth in the euro area: Testing the Porter hypothesis. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2023, 126, 102995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albrizio, S.; Kozluk, T.; Zipperer, V. Environmental policies and productivity growth: Evidence across industries and firms. J. Environ. Econ. Manag. 2017, 81, 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hille, E.; M’obius, P. Environmental policy, innovation, and productivity growth: Controlling the effects of regulation and endogeneity. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2019, 73, 1315–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benatti, N.; Groiss, M.; Kelly, P.; Lopez-Garcia, P. The Impact of Environmental Regulation on Clean Innovation: Are There Crowding Out Effects? ECB Working Paper; European Central Bank (ECB): Frankfurt, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–57. Available online: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2946~844af1ac30.en.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Mani, M.; Fredriksson, P. Trade Integration and Political Turbulence: Environmental Policy Consequences; IMF Working Paper; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; Available online: https://ideas.repec.org/p/imf/imfwpa/2001-150.html (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Fredriksson, P.; Mani, M. The Rule of Law and the Pattern of Environmental Protection; IMF Working Paper; International Monetary Fund: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; pp. 1–27. Available online: https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2002/wp0249.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Shapiro, J. Institutions, Comparative Advantage, and the Environment. Rev. Econ. Stud. 2025, 92, 4152–4193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.; Shleifer, A. Legal origins. Q. J. Econ. 2002, 117, 1193–1230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Law and Finance. J. Political Econ. 1998, 106, 1113–1155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayek, F. The Constitution of Liberty; The University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960; Available online: https://books.google.com.ua/books?id=ENQjPm-S7UEC&printsec=frontcover&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Pop-Eleches, C.; Shleifer, A. Judicial checks and balances. J. Political Econ. 2004, 112, 445–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A. Law and finance after a decade of research. In Handbook of the Economics of Finance; Constantinides, G.M., Harris, M., Stulz, R.M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2013; Volume 2, pp. 425–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A. What Works in Securities Laws? J. Financ. 2006, 61, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Agency problems and dividend policies around the world. J. Financ. 2000, 55, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Investor protection and corporate governance. J. Financ. Econ. 2000, 58, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. Legal Determinants of External Finance. J. Financ. 1997, 52, 1131–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Porta, R.; Lopez-de-Silanes, F.; Shleifer, A.; Vishny, R.W. The Quality of Government. J. Law Econ. Organ. 1999, 15, 222–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, J.; Deakin, S.; Sarkar, P.; Siems, M.; Singh, A. Shareholder protection and stock market development: An empirical test of the legal origins hypothesis. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 2009, 6, 343–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djankov, S.; McLiesh, C.; Shleifer, A. Private Credit in 129 Countries. J. Financ. Econ. 2007, 84, 299–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, P.; Wollscheid, J. Legal Origin and Climate Change Policies in Former Colonies. Environ. Resour. Econ. 2015, 62, 309–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fredriksson, P.; Wollscheid, J. Legal Origins and Environmental Policies: Evidence from OECD and Developing Countries. Lett. Spat. Resour. Sci. 2018, 11, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A.; Chilton, A.S.; Linos, K.; Weaver, A. The global dominance of European competition law over American antitrust law. J. Empir. Leg. Stud. 2019, 16, 731. Available online: https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2513 (accessed on 2 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A. The Brussels Effect: How the European Union Rules the World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A.; Chilton, A.; Linos, K. The gravity of legal diffusion. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 2024, 2023, 2. Available online: https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol2023/iss1/2 (accessed on 2 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bradford, A.; Chang, Y.-C.; Chilton, A.; Garoupa, N. Do legal origins predict legal substance? J. Law Econ. 2021, 64, 225–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobbin, F.; Simmons, B.A.; Garrett, G. The global diffusion of public policies: Social construction, coercion, competition, or learning? Annu. Rev. Sociol. 2007, 33, 449–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodea, C.; Hicks, R. International finance and central bank independence: Institutional diffusion and the flow and cost of capital. J. Politics 2015, 77, 268–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romelli, D. The political economy of reforms in central bank design: Evidence from a new dataset. Econ. Policy 2022, 37, 641–688. Available online: https://www.economic-policy.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/9104_Romelli.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025). [CrossRef]

- Romelli, D. Trends in Central Bank Independence: A De-Jure Perspective; Bocconi University Working Paper; Bocconi University: Milan, Italy, 2024; p. 217. Available online: https://repec.unibocconi.it/baffic/baf/papers/cbafwp24217.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Oto-Peralies, D.; Romero-Avila, D. Legal Reforms and Economic Performance: Revisiting the Evidence; World bank Development Report Background paper; World Bank: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 1–109. Available online: https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/193351485539892515-0050022017/original/WDR17BPRevisitingLegalOrigins.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- MMutarindwa, S.; Schäfer, D.; Stephan, A. Differences in African banking systems: Causes and consequences. J. Inst. Econ. 2021, 17, 561–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. Reversal of fortunes: Geography and institutions in the making of the modern world income distribution. Q. J. Econ. 2002, 117, 1133–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Johnson, S.; Robinson, J.A. The colonial origins of comparative development: An empirical investigation. Am. Econ. Rev. 2001, 91, 1369–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acemoglu, D.; Robinson, J. Unbundling Institutions. J. Political Econ. 2005, 113, 949–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becchetti, L.; Ciciretti, R.; Conzo, P. Legal Origins and Corporate Social Responsibility. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurbus, B.; Rant, V. A Legal Origin Perspective on Corporate Rating Disagreement. Res. Int. Bus. Financ. 2025, 74, 102702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaeser, E.; Shleifer, A. The Rise of the Regulatory State. J. Econ. Lit. 2003, 41, 401–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lu, H.; Du, M. Regional Differences in Agricultural Carbon Emissions in China: Measurement, Decomposition, and Influencing Factors. Land 2025, 14, 682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Z.; Wang, T.; Xu, J.; Li, C. Can Agricultural Productive Services Inhibit Carbon Emissions? Evidence from China. Land 2023, 12, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, S.; Liu, G. A low carbon management model for regional energy economies based on blockchain technology. Heliyon 2023, 9, e19966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sotnyk, I.; Kurbatova, T.; Kubatko, O.; Prokopenko, O.; Prause, G.; Kovalenko, Y.; Trypolska, G.; Pysmenna, U. Energy security assessment of emerging economies under global and local challenges. Energies 2021, 14, 5860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework (CAPMF); Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development: Paris, France, 2025; Available online: https://www.oecd.org/climate-action/ipac/capmf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Nachtigall, D.; Lutz, L.; Cárdenas Rodríguez, M.; Haščič, I.; Pizarro, R. The Climate Actions and Policies Measurement Framework: A Structured and Harmonised Climate Policy Database to Monitor Countries’mitigation Action; Environment Working Paper; OECD: Paris, France, 2022; p. 203. Available online: https://one.oecd.org/document/ENV/WKP(2022)15/en/pdf (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- World Bank Data. World Development Indicators (WDI). The World Bank 2025. Available online: https://databank.worldbank.org/source/world-development-indicators (accessed on 2 September 2025).

- Kopp, R.J. The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change after 20 Years: Is There a Better Way Forward? Resources. 2011. Available online: https://www.resources.org/common-resources/the-united-nations-framework-convention-on-climate-change-after-20-years-is-there-a-better-way-forward/ (accessed on 2 November 2025).

- United Nations. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 1992. Available online: https://unfccc.int/files/essential_background/background_publications_htmlpdf/application/pdf/conveng.pdf (accessed on 2 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.