Abstract

This study investigates how consumer brand trust is shaped by the interplay of sustainability disclosure valence (positive/negative), domain (social/environmental), and information source credibility (internet influencer/scientific report). Using a mixed-methods approach, combining a series of focus groups and a 2 × 2 × 2 between-subjects scenario experiment with a sample of 354 university students, we analyzed both the main and interactive effects of these factors on brand trust via hierarchical regression. The findings confirm that positive disclosures in both social and environmental domains significantly enhance brand trust. We observed a significant synergistic interaction, where consistent positive disclosures across both sustainability domains yield the greatest increase in trust. The study uncovers a domain-specific boundary condition for source credibility. While the source of information significantly moderates the impact of social sustainability disclosures—with influencers failing to generate the same punitive impact as scientific reports regarding social transgressions—source credibility exerts no significant influence on environmental disclosure processing. These findings suggest that consumers process environmental data as technical information (source-neutral) but social data as moral signals (source-dependent). Practically, the results suggest that brands require a holistic sustainability communication strategy and rely on highly credible sources for sensitive social messaging, especially when managing reputational risk or responding to negative disclosures.

1. Introduction

In an era of heightened consumer consciousness, a brand’s commitment to sustainability has transitioned from a peripheral concern to a central pillar of corporate strategy and brand management. Consumers increasingly expect and demand transparency, accountability, and ethical conduct from the companies they support, particularly in high-impact industries such as fashion. Consequently, how brands communicate their sustainability efforts has become a critical determinant of consumer trust, which is understood as a consumer’s willingness to rely on a brand’s perceived competence and integrity. While a growing body of research confirms that credible sustainability narratives can elevate brand trust, the mechanisms through which consumers process this complex and often conflicting information remain underexplored.

Despite the proliferation of CSR research, considerable theoretical gaps remain regarding how consumers integrate conflicting sustainability signals [1]. First, the literature frequently conflates the dimensions of sustainability, treating “green” (environmental) and “social” initiatives as interchangeable predictors of trust [2,3]. This oversight ignores emerging evidence suggesting that consumers process environmental stewardship—often viewed as a technical or competence-based attribute—through different cognitive pathways than social responsibility, which is viewed as a moral or character-based attribute [4,5]. Consequently, the interactive effects of these distinct domains remain unmapped. Does success in one domain buffer against failure in the other, or does inconsistency trigger a “hypocrisy penalty” that nullifies all efforts [6,7]?

Second, the role of source credibility in this multi-dimensional context is underexplored and often oversimplified. While attribution theory posits that independent sources generally enhance message credibility, it remains unclear whether this buffering effect holds equally across sustainability domains [8]. Specifically, does the “moral weight” of social disclosures require a different threshold of source authority than the “technical weight” of environmental disclosures? By juxtaposing a high-authority source (scientific report) against a low-authority source (internet influencer) within a factorial design, this study isolates the boundary conditions of source credibility [9,10]. Unlike cross-sectional surveys that capture static correlations, the experimental design employed here allows for the causal dissection of how conflicting sustainability signals—filtered through divergent sources— work towards reshaping brand trust. To our best knowledge, no prior study has experimentally investigated the simultaneous and interactive effects of both social and environmental communications, accounting for the information source.

Therefore, the primary aim of this study is to explore how consumer brand trust is affected by the interplay of social and environmental sustainability disclosure valence (positive vs. negative) and the credibility of the information source. Employing a 2 × 2 × 2 between-subjects experimental design, in keeping with recommendations by Aguinis and Bradley [11], we examine not only the main effects of these factors but also their crucial interactions, while controlling for important consumer characteristics such as prior brand trust, skepticism toward CSR, and sustainability engagement. By doing so, we seek to provide a more holistic and granular assessment of the drivers of brand trust in the contemporary information environment.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. First, we review the relevant literature to develop our research hypotheses. Next, we describe the research methodology, including the experimental design, sample characteristics, and measurement scales. Subsequently, we present the results of our statistical analysis, followed by a detailed discussion of the findings, their theoretical and practical contributions, and the study’s limitations.

2. Theoretical Background and Hypothesis Development

Brand trust is conceptualized as the willingness of consumers to rely on a brand based on the perceived competence, integrity, and benevolence that the brand demonstrates over time [12]. Researchers have long argued that trust entails both cognitive evaluations, informed by rational assessments of a brand’s performance, and affective responses evoked by emotive cues in corporate communications [10]. While brand trust is frequently conceptualized as a multidimensional construct encompassing competence, integrity, and benevolence [12], empirical studies suggest that these dimensions are highly correlated and often indistinguishable in consumers’ holistic evaluations of brands, particularly in high-involvement categories [13]. Consequently, this study adopts a unidimensional approach to measuring brand trust, which is reflected in the formulation of its research hypotheses. This decision is supported by research indicating that a consolidated measure provides superior predictive validity when assessing the aggregate impact of corporate communications on consumer confidence [13,14]. By employing a unidimensional scale, we focus on the magnitude of trust formation rather than its internal structural nuances, avoiding the potential for multicollinearity inherent in multi-factor scales utilized in scenario-based experiments.

Sustainability disclosures—by highlighting concrete actions and commitments—offer consumers tangible evidence of these attributes, thereby serving as a potent cue that influences trust judgments [12]. Empirical evidence supports the proposition that when sustainability narratives are perceived as credible and authentic, they can elevate levels of brand trust among consumers [15,16]. In particular, positive sustainability disclosures can align with consumers’ ethical values and serve to reduce uncertainty about the brand’s motives and practices [15,17]. In contrast, negative sustainability communications—such as accounts of greenwashing or socially irresponsible actions—have been shown to generate distrust by exposing discrepancies between a brand’s rhetoric and its actual behavior [18]. Studies emphasizing social cynicism further reveal that consumers can exhibit heightened skepticism toward brands perceived to be insincere or opportunistic in their sustainability claims [18].

Scholars have made distinctions between social sustainability disclosures and environmental sustainability disclosures, arguing that these dimensions, while complementary, impact brand trust via different psychological pathways [17,19]. Social sustainability communications typically encompass issues such as labor rights, community development, and corporate social responsibility efforts, and it often resonates with consumers on an emotional level [10,20]. Conversely, environmental sustainability claims relate more to ecological commitments and resource management practices, appealing to consumers’ rational assessments of a brand’s long-term viability and stewardship [15,16]. Each dimension is believed to trigger its own set of cognitive and affective responses, suggesting that the integration of both types of claims may yield a more robust pattern of trust formation [12,20]. This synergistic process, where both aspects of sustainability are consistent, may reduce consumer ambiguity and create a congruent brand narrative that may be perceived as more comprehensive and compelling [10,16]. Accordingly, we propose the following hypotheses:

H.1.

Social (H.1.1) and environmental (H.1.2) sustainability disclosures correlate with brand trust after scenario exposure, such that positive sustainability disclosures enhance brand trust and negative disclosures harm it.

H.2.

Social and environmental disclosures positively moderate each other’s effects on brand trust after scenario exposure.

The impact of marketing communications, including sustainability claims, on brand trust is widely acknowledged as being considerably influenced by extrinsic moderating factors such as source credibility, media framing, and consumer attitudes and sensitivities [12]. Specifically, the credibility of the information source can mitigate or exacerbate the effects of both positive and negative sustainability disclosures, thereby influencing how strongly such information is internalized by consumers [21]. For instance, when sustainability information originates from credible and independent sources, its positive or negative effects on brand trust are correspondingly amplified, as consumers rely more on these signals to validate their assessments of the brand [10,20].

We posit that the mechanism of trust formation differs between sustainability domains due to the inherent nature of the claims [4]. Environmental performance is increasingly metric-driven—defined by carbon footprints, water usage, and waste reduction—acting as a “search attribute” where data can be evaluated on its face value. In this context, the information content may supersede the information source because standardized reporting transforms complex credence claims into verifiable data points [22]. In contrast, social sustainability issues, such as labor rights, fair wages, and supply chain ethics, function as “credence attributes” or moral signals. The opacity of global supply chains makes social claims difficult for consumers to verify independently [2]. Consequently, the credibility of the information source becomes a heuristic proxy for the veracity of the claim [23]. We argue that the “moral weight” of social claims—often processed through the psychological dimension of warmth—requires a source with perceived high integrity (e.g., a scientific or audit report) to be internalized [5]. Conversely, the “technical weight” of environmental disclosures align with the dimension of competence and may be processed more directly, rendering the source less critical [24].

Our own exploratory research, in the form of four focus group interviews conducted on a group of 74 university students in April 2025, indicated that indeed the level of credibility attributed to information sources may affect the impact of sustainability messages. Internet influencers and scientific reports emerged as the least and the most trustworthy communication channels, respectively. With that in mind, we posit the following:

H.3.

Information source (internet influencer vs. scientific report) moderates the effects of social (H.3.1) and environmental (H.3.2) sustainability disclosures on brand trust after scenario exposure.

Brand trust is generally understood not as a fleeting sentiment but as a cumulative construct, developed over time through repeated interactions and experiences between the consumer and the brand [25]. Consequently, established attitudes and trust are relatively stable and resistant to change. When consumers encounter new information -whether positive or negative—they do not evaluate the brand from a neutral starting point. Instead, their pre-existing level of trust acts as a cognitive anchor. Therefore, pre-existing levels of consumer trust can act as a buffering mechanism against negative brand news, with loyal consumers exhibiting more resilience in the face of adverse disclosures [12,21]. However, this buffering effect is not absolute. While prior trust provides resistance, it does not grant immunity. Research on brand transgressions indicates that when new information highlights a severe violation of trust, particularly one that is perceived as intentional or central to the brand’s identity, prior attitudes can be rapidly overturned [26]. In certain situations, consumers who have high levels of trust may react more negatively to betrayal than those with lower trust, demonstrating a “love becomes hate” effect because their strong expectations have been violated [27]. However, based on the prevailing view, we hypothesize that:

H.4.

Brand trust before scenario exposure is positively correlated with brand trust after scenario exposure.

Beyond the direct and interactive effects of sustainability disclosures, it is essential to account for stable individual differences that shape consumer perceptions. A consumer’s reaction to brand information is not formed in a vacuum; it is filtered through their demographic background, general disposition toward corporate ethics, and personal values.

Demographic characteristics such as gender and age have often been linked to variations in ethical decision-making and consumption patterns. Socialization theory suggests that gender-based differences in socialization can lead to different value orientations, potentially making female consumers more sensitive to or appreciative of a brand’s social and ethical conduct [28]. Accordingly, empirical studies in sustainable fashion frequently observe that female consumers exhibit higher sensitivity to ethical claims and stronger adverse reactions to corporate irresponsibility. Similarly, generational cohorts differ in their skepticism and engagement, with younger consumers (Gen Z) demonstrating higher baseline awareness but also higher cynicism regarding corporate motives [29]. These demographic factors, therefore, may correlate with overall trust levels following exposure to sustainability communications.

A more direct psychological antecedent of trust in this context is a consumer’s general skepticism toward Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). This skepticism, defined by Skarmeas and Leonidou [30] as a stable dispositional trait, shapes how all corporate communication is processed. The underlying mechanism is often explained by attribution theory [31], suggesting that consumers act as “naive psychologists,” constantly attempting to deduce the motives behind a company’s actions. Accordingly, highly skeptical individuals are predisposed to attribute a company’s pro-social or pro-environmental actions to extrinsic, self-serving motives (e.g., profit or public relations) rather than genuine, intrinsic values. This inherent doubt is expected to act as a significant drag on trust formation, regardless of the valence of the information presented.

Conversely, a consumer’s personal engagement in sustainability represents the degree to which social and environmental issues are personally relevant and important. For highly engaged consumers, a brand’s sustainability performance is not a peripheral attribute but a core component of its identity [32]. The mechanism of value congruence suggests that when a brand demonstrates positive sustainability actions, it resonates with the consumer’s own values, fostering a stronger and more trusting relationship. These consumers are more likely to reward brands that they perceive as partners in achieving broader societal goals. Based on these considerations, we formulate the following hypotheses regarding key consumer characteristics:

H.5.

Consumers’ age and gender correlate with brand trust after scenario exposure.

H.6.

Skepticism toward CSR is negatively correlated with brand trust after scenario exposure.

H.7.

Sustainability engagement is positively correlated with brand trust after scenario exposure.

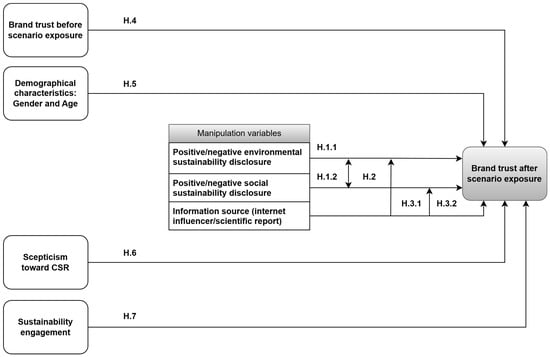

3. Graphical Model of the Study’s Conceptual Framework

The scope and hypotheses of the study are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the study and its hypotheses. Source: Own elaboration.

3.1. Research Methods

This research employed a mixed-methods approach composed of qualitative (Study 1) and quantitative components (Study 2). Study 1 consisted of a series of focus group interviews to investigate a key aspect of this project: the consumer perceptions of information sources used to relay sustainability information. The main purpose of Study 1 in the context of our mixed-methods design was to inform our choice of two information sources for experimental scenarios. We aimed to select two information sources that consumers commonly use to obtain sustainability information, while also ensuring they exhibited justifiable differences in trust, which could lead to variations in how effectively the information influences consumer behavior. This aligned with one of the overarching goals of this research, which was to understand the role of information sources, besides the message content itself, in inducing changes to brand trust. Considering how dynamic the current market environment is, coupled with possible generational and national differences, we decided that leaning solely into past published research for guidance on the selection of information sources for this experiment could result in a suboptimal design, not reflecting the sentiment of our focal cohort—Polish university students—who served as a proxy for a broader population of Gen Z consumers.

This methods section will first describe the exploratory qualitative study, to be followed by the quantitative part.

3.2. Study 1: Qualitative Exploratory Design

Study 1 employed an exploratory qualitative approach to examine the level of trust in diverse sources of information about companies’ socially and environmentally responsible (or irresponsible) activities and to identify key determinants shaping this trust [33]. Six focus group interviews (FGIs) were conducted in April 2025 with 74 students enrolled in management-related programs, selected through purposive sampling to ensure heterogeneity in demographic and academic profiles. To enhance the internal validity of the subsequent experiment, these respondents did not take part in the quantitative Study 2. This exclusion was ensured by Study 1 members belonging to different, non-overlapping student groups than the Study 2 participants. Each focus group interview adhered to the same moderator’s outline, lasted approximately 50 min, and invited participants to evaluate their trust in various information sources, such as scientific publications, corporate websites, and social media, while justifying their reasoning. The following research questions reflected the structure of the interviews and expressed the aims of this study:

- RQ1: What are the primary information sources that young consumers use to learn about the sustainability-related actions of brands and companies?

- RQ2: What trust levels are associated with various information sources?

- RQ3: What are the reasons for the varying levels of trust attributed to the most frequently reported sources of information?

- RQ4: Are there any group differences in perceiving the most frequently reported sources of information?

- RQ5: Are popular sources of information and their trust levels consistent across different consumer-focused industries?

Data triangulation, based on comparisons across six independent student groups, served to enhance the credibility and interpretive depth of the findings [34]. Triangulation facilitated cross-validation of themes and enabled the identification of both convergent and divergent perceptions, particularly in relation to more controversial sources (e.g., influencers or online forums) [35,36]. Analytical procedures followed open and selective coding [37,38], with triangulation across participant groups enhancing validity.

3.3. Study 2: Scenario Experiment

The study employed a scenario-based experimental method, also known as a vignette experiment. Scenario-based experiments enable researchers to present participants with depictions of realistic situations and measure their responses [11]. This approach was successfully used in past consumer behavior research, including sustainable consumption (e.g., [39]). Our experiment showed participants eight scenarios corresponding to different combinations of disclosures about the environmental and social actions of a fashion brand, conveyed by either a scientific report or an Internet influencer. Accordingly, these scenarios manipulated three distinct variables: environmental disclosure (negative or positive), social disclosure (negative or positive) and information source (scientific report or influencer).

A 2 × 2 × 2 between-subjects factorial design was used, exploring the impact of three experimental factors on consumer brand trust.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of the 8 experimental conditions. Each scenario contained a hypothetical message concerning the sustainability of the clothing brand they indicated earlier as the one they purchased most often.

By choosing a real, most-frequently bought brand as the focal point of the scenarios, we aimed to increase the ecological validity of the study. Respondents faced with artificial brands may fail to provide genuine trust responses, due to their lack of “emotional investment” in the brand [40].

The scenario message contained one of four combinations of positive and negative descriptions of the brand’s environmental and social performance presented by either an internet influencer or read in a scientific report. After reading the scenario, the participants were asked about their trust in the brand.

3.4. Example Scenario

Scenario 2—Negative social actions of the brand and positive environmental actions learned from an influencer

You are a regular customer of clothing Brand X.

Information shared by an influencer appeared on social media (TikTok, Instagram) stating that Brand X has been accused of serious social abuses. He reports that the company used cheap labor in developing countries, ignoring working conditions, and also avoided paying taxes in the country where it operates. Photos showing company employees in very difficult conditions appeared on the influencer’s social media page. Employees reported being forced to work over a dozen hours a day without adequate pay, and people trying to organize trade unions were fired. Furthermore, it turned out that the company employs minors in some production plants outside Europe. Human rights organizations are calling for a boycott of brand X until transparent changes are introduced.

However, another influencer reported on social media that Brand X has implemented a series of pro-ecological actions. The company reduced CO2 emissions throughout the production chain, switched to producing clothes from recycled and renewable materials, and reduced water consumption. He informs that Brand X openly communicates its climate goals and reports progress. The brand invests in wastewater treatment technologies and conducts collections of used clothing, offering customers discounts for returned clothes. All the brand’s packaging is now biodegradable, and deliveries are made using low-emission transport. The company has also signed an international climate agreement within the fashion industry.

Knowing this, how do you perceive Brand X?

3.5. Measurement Scales

The questionnaire’s scenarios were complemented by standardized measurement scales intended to capture the constructs from this study’s conceptual framework. The model employed in this study comprised four latent variables, all of which were classified as reflective constructs, following suggestions and practice outlined in the literature.

The next table presents the measurement scales used to establish the scores of reflective constructs in this research. To save space, Table 1 lists not only Likert items and literature sources but also the reliability and validity metrics derived from confirmatory factor analysis that are discussed later in the paper.

Table 1.

Likert scale items for the study’s construct together with CFA diagnostics.

3.6. Statistical Analysis

Our statistical analysis involved a two-step process to investigate the hypothesized relationships between the focal variables.

First, we performed Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) using the Lavaan and semTools packages in R (version 4.5.2). This step was crucial to estimate the reliability and validity of the latent constructs. By doing this, we ensured that the measurement model derived from the observed indicators was robust, demonstrating adequate levels of internal consistency, convergent validity, and discriminant validity, as recommended by Hair et al. [43].

Second, we used hierarchical regression analysis to examine the antecedents of post-scenario brand trust (post BT). It allowed us to isolate the effects of the manipulated variables (environmental disclosure, social disclosure, and information source) while controlling for pre-existing attitudes and demographics. We built four progressively more complex models, starting with the manipulated variables as predictors in the first model. In the subsequent steps, we added variables related to pre-scenario BT (model 2), consumer characteristics (sex, age, and education) in model 3, and in the final regression, skepticism towards CSR and sustainability engagement.

4. Research Results

4.1. Conclusions from Focus Group Interviews in Study 1

The content analysis of six focus group interviews (N = 74) identified key determinants of trust in sustainability-related information sources. Five thematic areas emerged, corresponding to the study’s research questions (RQ1–RQ5).

- RQ1: What are the primary information sources that young consumers use to learn about the sustainability-related actions of brands and companies?

In response to RQ1, the qualitative analysis revealed that young consumers rely on a diverse set of information sources to learn about companies’ sustainability-related activities. These sources span several formal and informal channels, as described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Primary Information Sources Used by Young Consumers to Learn About Companies’ Sustainability Actions.

These findings suggest that young consumers’ awareness of corporate sustainability is shaped by a mix of formal and informal channels, from expert reports and academic articles (seemingly more popular among digitally literate or sustainability-aware individuals) to social media and podcasts provided by influencers (indicated more frequently by interviewees with a more casual interest in sustainability).

- RQ2: What trust levels are associated with various information sources?

Trust was found to be source-dependent. As shown in Table 3, scientific publications and certified audit reports were most trusted (avg. 4.8–4.5 on a 5-point scale), while influencers and social media posts were met with skepticism (avg. 1.6–1.8). Corporate websites and traditional media received mixed evaluations.

Table 3.

Trust Levels Across Information Sources (Average Scores Across Focus Groups).

- RQ3: What are the reasons for the varying levels of trust attributed to the most frequently reported sources of information?

The analysis revealed that trust in information sources related to companies’ sustainability actions varied considerably based on a combination of factors, including perceived independence, financial affiliation, content format, and contextual credibility (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Reasons for Variation in Trust Across Common Information Sources.

Scientific publications and independent audit reports were rated as highly trustworthy due to their external verification, methodological transparency, and perceived objectivity. Participants emphasized the importance of evidence-based content and clearly cited sources: “If it’s a peer-reviewed report or an audit, I trust it more because someone neutral had to check it.”

Corporate websites elicited mixed reactions. While some participants appreciated direct access to CSR or ESG statements, others were skeptical, citing promotional intent and lack of external validation: “It’s useful, but they obviously want to look good. I always double-check with other sources.”

Influencer content and social media posts were consistently rated as least trustworthy, largely due to perceived financial motivations, lack of expertise, and manipulative intent. Participants frequently associated these sources with paid promotions and superficial narratives: “If they’re paid, I assume it’s biased” and “they just post to get clicks or sell something.”

Some participants noted that trust could be partially recovered when sponsored content included transparency about affiliations or when influencers showed domain relevance and long-term consistency in sustainability topics: “I don’t reject it entirely, but I need to know who paid for it—and I check it twice.”

Media literacy also shaped the variation in trust, with more critically engaged participants demonstrating awareness of structural biases and sponsorship cues. Overall, the findings indicate that perceived impartiality, depth of information, and transparency about content origins are the most salient factors driving differences in trust across commonly used sources.

- RQ4: Are there any group differences in perceiving the most frequently reported sources of information?

The analysis revealed clear group differences in how participants evaluated the credibility of commonly encountered information sources, particularly social media influencers. Digital literacy emerged as a key differentiating factor. Participants with high digital literacy expressed strong skepticism toward influencer content, often emphasizing the lack of credible citations and promotional motives. Those with moderate literacy showed selective trust, depending on perceived authenticity. In contrast, individuals with lower digital literacy tended to rely more on influencer popularity and relatability, sometimes perceiving such content as sincere and trustworthy despite limited evidence. These findings suggest that trust in digital content is moderated not only by the source but also by the cognitive filters and evaluative capacity of different audience groups.

- RQ5: Are popular sources of information and their trust levels consistent across different consumer-focused industries?

The study findings indicate that the perceived trustworthiness of popular information sources is remarkably consistent across various consumer-oriented industries. Regardless of the specific sector, whether fashion, food, cosmetics, or other consumer-facing markets, participants demonstrated a clear and recurring pattern in how they evaluated information credibility.

In all focus groups, company-only sources were viewed with caution and often perceived as self-promotional, particularly when lacking external verification. By contrast, third-party endorsements, such as academic reports, governmental statements, or independent audits, consistently elevated the level of trust across all discussed industries. This uniform preference suggests that source characteristics, such as independence, empirical backing, and transparency outweigh industry-specific factors in shaping trust evaluations.

Even in sectors often associated with differing levels of regulation or reputational risk, the pattern remained stable: the more external and verifiable the source, the higher the trust. The consistency of this judgment across discussions suggests a generalized evaluative framework applied by young consumers when assessing corporate sustainability communication—regardless of the product category.

Across groups, recurring themes included the importance of external verification, the citation of empirical data, and skepticism toward marketing-biased content outputs, confirming a high co-occurrence of distrust in influencers with perceived marketing bias. Collectively, these findings demonstrate the value of transparency, independence, and critical media literacy in fostering trust in sustainability communication.

Based on the above-discussed results of our qualitative component, we decided to choose scientific reports and internet influencers as two distinct information sources for the subsequent scenario experiment. Table 5 provides more detail on our approach to leveraging the qualitative results in the follow-up quantitative study.

Table 5.

Integration of qualitative insights into the quantitative component of the study.

4.2. Sample Characteristics in Study 2

A total of 354 complete responses were collected from students at two economics universities in Krakow and Warsaw in May and July 2025.

Utilizing cluster sampling, data were gathered from randomly selected student groups, which were investigated as a whole. Data collection occurred during standard class sessions. Students were clearly informed that participation in the study is not mandatory, and they are free to opt out at any time; however, if they completed the survey, their data would be kept anonymous and used solely for academic purposes. Respondents completed questionnaires on their personal electronic devices (laptops and smartphones) under supervision after a survey link was displayed on screen. Inputting the link into a browser directed users to a webpage featuring a randomization algorithm that allocated respondents to one of eight scenarios, each accompanied by scaled questions.

The 354 responses in the sample were spread across scenario groups as follows (the numbers are not equal due to the nature of the random selection process):

- Scenario 1 (negative environmental disclosure, negative social disclosure, influencer): 43

- Scenario 2 (positive environmental disclosure, negative social disclosure, influencer): 41

- Scenario 3 (positive environmental disclosure, positive social disclosure, influencer): 45

- Scenario 4 (negative environmental disclosure, positive social disclosure, report): 43

- Scenario 5 (negative environmental disclosure, negative social disclosure, report): 48

- Scenario 6 (positive environmental disclosure, negative social disclosure, report): 43

- Scenario 7 (positive environmental disclosure, positive social disclosure, report): 49

- Scenario 8 (negative environmental disclosure, positive social disclosure, report): 42

Table 6 provides an overview of the demographic structure of the sample.

Table 6.

Sample characteristics.

Typical respondents were female (61.3%), were enrolled in a bachelor’s program (84.5%), were between 22 and 24 years old (43.8%) and bought clothes at Zara (19.5%).

While the use of student samples is often debated, this cohort represents a suitable population for this specific investigation. The participants belong to Generation Z, a demographic that is simultaneously the primary consumer base for fast fashion brands and the most avid audience of influencer-generated content. Therefore, in the context of fashion sustainability and social media influence, this sample possesses higher ecological validity than a general population sample for theoretical testing of cognitive mechanisms (i.e., how information valence interacts with data sources).

4.3. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

Before proceeding to the regression analysis, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted to assess the reliability and validity of the reflective latent variables included in the model. This initial step is crucial because a CFA measurement model with inadequate reliability and validity is prone to yield constructs that are difficult to interpret and could produce spurious correlations.

The reliability of a CFA solution can be assessed with average variance extracted (AVE) and Cronbach’s alphas, which can be found in Table 1. An AVE indicates the average amount of variance explained by a latent variable in its indicators, which should be more than 0.50 [43]. Cronbach’s alphas provide a measure of the correlations among the indicators of a construct and should exceed 0.7 [44]. Considering that for each latent variable in the measurement model these two metrics surpass the recommended thresholds, sufficient reliability is demonstrated.

Table 1 also contains factor loadings, which are correlations for each Likert item and its corresponding construct. When squared, they indicate the proportion of variance in each indicator variable that is explained by its construct. The majority of factor loadings have absolute values greater than 0.7, with none falling below 0.5, which indicates a robustly estimated model. We observed that items 4.1 and 4.2 exhibited factor loadings (0.652 and 0.616) slightly below the 0.70 threshold. However, these items were retained to ensure content validity, as they capture the ‘cognitive concern’ dimension of sustainability engagement, which is theoretically distinct from the ‘behavioral intent’ captured by the remaining items.

Discriminant validity is frequently assessed using the Fornell-Larcker criterion [45], which postulates that latent variables possess distinct meanings if the square root of their average variance extracted (AVE) surpasses the maximum bivariate correlation coefficient with any other latent variable. In essence, a construct should exhibit stronger correlations with its own indicators than with other latent variables within the model. Table 7 shows pairwise correlations between CFA-estimated constructs and square roots of AVE along the diagonal.

Table 7.

Correlation coefficients between latent variables and the square roots of AVEs.

The estimated latent variables exhibit low to moderate correlations, with all not exceeding 0.7. This suggests that no single variable explains more than 50% of the variance in any other variable, supporting the assertion that the constructs are semantically distinct. As expected, the strongest correlations are observed between brand trust before and after the scenario, as these represent presumed continuity in consumer attitudes. Importantly, none of the bivariate correlations exceed the square root of their corresponding average variance extracted (AVE) values. This fulfills the Fornell-Larcker [45] criterion, corroborating the discriminant validity of the model.

Finally, overall goodness-of-fit indices should be examined to ensure that the covariance matrix recreated from the CFA model is close enough to the input covariance matrix computed from the sample data. As suggested by Garson [46], the acceptance values for the indices are as follows:

- Relative Chi-square < 3

- CFI, TLI, and RNI > 0.9

- GFI, AGFI, NFI > 0.8

- RMSEA < 0.05 for good model fit; < 0.08 for acceptable model fit.

Without exception, the recommended threshold and the goodness-of-fit indices reported in Table 8 are all within acceptance ranges, which implies a good model fit to the empirical data.

Table 8.

Overall goodness-of-fit measures for the CFA model.

4.4. Manipulation Effectiveness Checks

The variable “perceived corporate hypocrisy” served as a measure of manipulation effectiveness to verify if respondents understood scenarios in the way intended by the authors, which underlies the validity of the study. The expectation was that if the manipulations were successful, the respondents assigned to the scenarios involving only positive disclosures should display the lowest average value of perceived corporate hypocrisy, while those with the all-bad scenarios should have the greatest mean. The two intermediate scenarios, involving mixed information, should fall in between. The computation of group means produced the following results:

- Scenarios 1 and 5 (negative environmental and negative social disclosures): 0.504

- Scenarios 4 and 8 (negative environmental and positive social disclosures): 0.471

- Scenarios 2 and 6 (positive environmental and negative social disclosures): 0.241

- Scenarios 3 and 7 (positive environmental and positive social disclosures): −1.049.

Clearly, the means follow the anticipated linear pattern, which was statistically confirmed by a two-way ANOVA (F = 28.87, df1 = 3, df2 = 350, p < 0.001), with both main effects and the interaction term being significant. To conclude, it seems that the perceived hypocrisy of the brand indicated by the respondents was in a negative relationship with the positive valence of the sustainability communications. This suggests that the scenarios were correctly interpreted.

4.5. Regression Analysis

This section interprets the results of the hierarchical regression analysis presented in Table 9 to test the study’s seven core hypotheses. The final, most comprehensive model (Model 4) is used as the basis for these tests, as it controls for all variables included in the conceptual framework.

Table 9.

Regression models explain brand trust after the scenario.

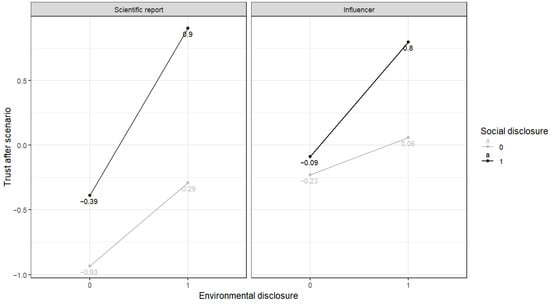

The first model in Table 9 is analogous to two-way ANOVA and accounts only for manipulation variables, their main effects, and two-way interactions. Its graphical representation is shown in Figure 2. The model explains 16.5% of variance in the after-scenario BT due to the joint effects of the three manipulation variables.

Figure 2.

Marginal means in Model 1 of after-scenario trust for combinations of environmental and social disclosures across two information sources. Source: Own elaboration.

The chart displays the marginal means for all combinations of manipulation variables that were connected by black and gray lines to represent different types of social disclosures. The added covariates in Model 4 do change the mean values, yielding more accurate estimates, but their relative positioning remains similar, indicating that consumers were indeed responsive to positive and negative sustainability disclosures, with the strongest positive and negative effects observed when the communications came from scientific reports.

In Model 4, the marginal means and significance tests for regression coefficients can be used to test hypotheses involving manipulation variables (H.1 through H.3).

The first hypothesis proposed that positive claims about a brand’s social (H.1.1) and environmental (H.1.2) actions would enhance brand trust, while negative disclosures would harm it. The results from Model 4 strongly support this hypothesis, as positive environmental disclosures were found to be a significant predictor of post-scenario brand trust (β = 0.42, p = 0.039), and positive social claims had an even stronger positive and significant effect on the dependent variable (β = 0.75, p < 0.001). These findings confirm that consumers adjust their trust in a brand based on its reported sustainability performance in both the social and environmental domains. However, it should be noted that hat while consumers value environmental stewardship, they prioritize social responsibility—the treatment of workers and human rights—as the primary determinant of brand trustworthiness. This finding challenges the prevailing emphasis on ‘green’ marketing in the fashion sector, suggesting that ‘social’ marketing carries significantly greater weight in trust formation.

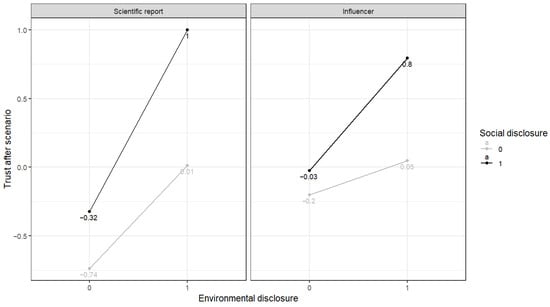

Hypothesis 2 suggested a synergistic relationship, where positive disclosures in one sustainability dimension would amplify the positive effect of communications in the other dimension. This was tested via the interaction term environmental disclosures × social disclosures. The analysis shows a positive and significant interaction effect (β = 0.57, p = 0.013), lending clear support to H.2. This synergy is visualized in Figure 3. The slope of the line for positive social disclosures (the green line) is considerably steeper than that for negative social disclosures (the red line), indicating that the trust benefit from advantageous environmental actions is magnified when the brand is also perceived as being socially responsible.

Figure 3.

Marginal means in Model 4 of after-scenario trust for combinations of environmental and social disclosure across two information sources. Source: Own elaboration.

Hypothesis 3 proposed that the information source (influencer vs. scientific report) would moderate the effects of both social (H.3.1) and environmental (H.3.2) disclosures on brand trust. The results for this hypothesis were mixed. On the one hand, the interaction between environmental disclosures and the information source was not statistically significant (environmental disclosures × influencer, β = −0.24, p = 0.286), meaning H.3.2 is not supported. The effect of environmental claims on trust does not significantly differ between an influencer and a scientific report. However, the interaction between social communications and the information source was significant (social disclosures × influencer, β = −0.50, p = 0.025), providing support for H.3.1. The location of the marginal means in Figure 3 indicates that the negative effect of adverse social disclosures on brand trust is significantly weaker when the information comes from an influencer compared to when it is delivered by a scientific report. This pattern is the strongest when both items of sustainability communications are negative (−0.2 vs. −0.72). Interestingly, the difference between the two sources of information is weaker when one or both disclosures are positive.

Hypothesis 4 concerned the influence of pre-existing brand trust, assuming a continuity of this consumer sentiment. In Model 4, brand trust before scenario exposure was the single strongest predictor (β = 0.61, p < 0.001), offering robust support for H.4. This underscores the key role of established attitudes in shaping reactions to new information.

Hypothesis 5 anticipated variability in brand trust after scenario exposure for different demographical subgroups of consumers. Age was not found to be a significant predictor of post-scenario trust, but gender was significant, with males reporting higher trust levels than females (β = 0.33, p = 0.007). Therefore, H.5 is partially supported.

The final two hypotheses related to general consumer attitudes toward sustainability and corporate responsibility. As predicted, skepticism toward CSR was a significant negative predictor of brand trust (β = −0.18, p = 0.001). This validates H.6, indicating that consumers with higher baseline skepticism exhibit reduced brand trust following exposure to sustainability disclosures. Conversely, sustainability engagement did not have a significant effect on post-scenario brand trust (β = −0.06, p = 0.252). Thus, H.7 is not supported. Once other factors are controlled for, a consumer’s general engagement with sustainability issues does not appear to influence their trust in a specific brand following scenario exposure.

5. Discussion

This study investigated the varied roles of sustainability disclosures, information source credibility, and consumer attitudes in shaping brand trust. Through a scenario-based experiment, we examined how positive and negative claims across social and environmental domains, conveyed by different sources, affect consumer trust in fashion brands. The findings both reinforce established theories and offer novel insights into the varied ways consumers process sustainability information.

5.1. Interpretation of Key Findings

The results of the hierarchical regression analysis largely supported our conceptual model, confirming that consumers adjust their trust in a brand based on its reported sustainability performance. We found that both positive social disclosures and positive environmental communications significantly enhance post-scenario brand trust, in line with H.1. Furthermore, a significant positive interaction between these two dimensions lent clear support to H.2, suggesting a synergistic effect where a brand’s consistent positive performance across both domains is rewarded with a greater increase in trust than would be expected from the sum of their individual effects. The study yielded more nuanced findings regarding the moderating role of the information source (H.3). While the source did not significantly alter the impact of environmental disclosures, it did moderate the effect of social claims, providing support for H.3.1. The negative coefficient for this interaction indicates that the impact of social disclosures on trust is significantly weaker when the information comes from an influencer compared to a scientific report. This difference was most pronounced when the information was consistently negative; in this condition, the scientific report generated a much stronger decline in trust than the influencer did. This suggests a substantial practical implication: influencers may be perceived as particularly untrustworthy when delivering purely negative messages, perhaps because their credibility is not sufficient to anchor such strong negative claims, or their message is discounted as potential sensationalism. Finally, the analysis confirmed the powerful influence of pre-existing consumer attitudes. Prior brand trust was the single most dominant predictor of post-scenario trust (H.4), while general skepticism toward CSR was a significant negative predictor (H.6). Conversely, a consumer’s general sustainability engagement did not emerge as a significant predictor (H.7), likely because the specific information presented in the scenarios provided a more immediate and powerful influence on judgment than a general disposition. In the presence of strong factual cues (e.g., a verified report on labor abuse), the consumer’s general ‘green’ attitude becomes secondary to the immediate processing of the specific transgression. This highlights the primacy of situational information over dispositional traits in high-involvement brand judgment tasks.

Overall, the evidence confirms that brand trust is not merely a function of what a brand does, but who validates it and how consistent the action is across ethical domains.

5.2. Theoretical Contributions

This study contributes to the literature on brand trust and sustainability communication in several ways. First, by examining the social and environmental dimensions of sustainability simultaneously, this study provides strong empirical evidence for a synergistic model of trust formation. It extends the work of scholars who have called for a distinction between these domains by demonstrating that their interaction is a critical component of brand evaluation (e.g., [17,19]). The study provides empirical evidence against the “siloed” approach to sustainability. The significant synergistic interaction between social and environmental disclosures implies that brands cannot simply “offset” poor social performance with aggressive environmental marketing. The consumer mind seeks congruence. A brand that saves the rainforest but exploits its workers creates a cognitive dissonance that blocks trust formation. To maximize brand trust, firms must adopt a holistic strategy where environmental and social initiatives are aligned and communicated as part of a unified ethical narrative. This confirms the theoretical propositions of Neumann et al. [16] regarding the power of consistent sustainability storytelling.

Second, the study offers an enhanced understanding of source credibility provided by other authors (e.g., [10]) by demonstrating its domain-specific and context-dependent effects. The finding that source credibility matters more for social than for environmental claims suggests that the nature of the information shapes how source cues are used. More importantly, the observation that the credibility gap between a scientific report and an influencer is largest in all-negative contexts is a significant contribution. It suggests that the perceived authority of a source is tested most severely when it bears bad news, contributing to theories on source effects by showing that a source’s influence is not static but highly elastic depending on the valence of the message, building on prior work that highlights the importance of source credibility in mitigating the effects of negative disclosures.

This domain-specific nature of source credibility can be explained by combining insights from Information Economics with the Stereotype Content Model. Our results suggest that consumers process environmental sustainability as a “search attribute” or a technical competence marker [4,22]. Because environmental information in our scenarios relied on “hard” metrics (e.g., CO2 reduction, biodegradable materials), consumers likely processed these claims as objective facts. Consistent with Jain and Posavac [23], when attributes are perceived as verifiable (searchable), the reliance on source credibility diminishes. Whether the data was delivered by a scientific report or an influencer, the “technical weight” of the message carried its own evidentiary burden, rendering the messenger secondary.

Conversely, the significant interaction found for social disclosures confirms that social sustainability functions as a “credence attribute” anchored in morality [5]. Claims regarding labor rights and human dignity are inherently opaque and unverifiable for the average consumer. In the absence of verifiable data, the consumer must rely entirely on the moral authority of the source to validate the claim. The scientific report, possessing high epistemic authority [47], successfully validated the moral transgression in the negative social condition, causing a steep drop in trust. The influencer, lacking this moral authority, failed to anchor the severity of the claim, leading to a buffering effect. This supports the view that for moral/credence signals, the messenger is the message.

Finally, even when consumers encounter powerful new information from multiple sources, the study robustly confirms the theoretical importance of pre-existing attitudes. By demonstrating the outsized influence of prior trust and CSR skepticism in a multi-cue experimental design, our findings underscore the stability of these constructs and their central role as perceptual filters. This reinforces the work of scholars who have highlighted the role of established trust as a buffer and skepticism as a key challenge in corporate communication [12,21].

5.3. Practical Implications

The findings offer several actionable insights for brand managers, marketers, and sustainability communicators. Given that social disclosures have nearly double the impact on trust compared to environmental claims (β = 0.75 vs. 0.42), brands should prioritize the communication of their social safeguards—fair wages, labor conditions, and community impact—above all else. A ‘green’ strategy that neglects social responsibility is statistically unlikely to build robust trust. Furthermore, the synergistic interaction (β = 0.57) suggests that a ‘balanced scorecard’ approach is essential; excellence in one domain amplifies the value of the other, while failure in one disproportionately erodes the trust capital gained in the other. To build maximum trust, firms cannot focus on one dimension at the expense of the other, as consumers reward a coherent commitment to both ecological and social well-being.

Furthermore, the insights into source credibility have direct practical consequences. The finding that the source matters more for social disclosures suggests that brands should use highly credible, formal channels—such as detailed sustainability reports or third-party certifications—when communicating their performance on sensitive social issues. Critically, the fact that influencers are least trusted when conveying negative news indicates that brands should be cautious about using them for damage control or to communicate unfavorable information. The study reveals that influencers are ineffective validators of social reality. If a brand is facing a social sustainability crisis (e.g., labor scandal), deploying influencers to counter the narrative or spread positive social claims is likely to be ineffective due to their limited credibility in the moral domain. Conversely, influencers remain effective conduits for environmental communications. Brands can safely leverage influencer partnerships to broadcast technical achievements—such as the launch of a recycled clothing line or carbon-neutral shipping—as consumers appear to accept these technical claims regardless of the source’s perceived depth of expertise.

Finally, given that prior trust is the best predictor of future trust, the ultimate defense against negative disclosures is a long-term investment in building a strong, positive brand reputation, as suggested by Doney and Cannon [25]. To combat consumer skepticism, brands must prioritize transparency, providing verifiable data and clear evidence to back up their sustainability claims, thereby making their motives appear more genuine.

5.4. Limitations and Future Research

This study has several limitations that offer avenues for future research.

First, while the use of a student sample was theoretically justified for the fast fashion context, it imposes limitations on generalizability. The study relies exclusively on Generation Z university students; consequently, the findings may not extend to older generational cohorts or diverse occupational groups who may possess different value priorities and purchasing power. Also, respondents sourced from other cultural contexts may demonstrate differential sensitivities and social-media consumption patterns [48], potentially affecting this study’s focal relationships. Accordingly, future research should seek to replicate this experiment with more diverse populations.

Second, the use of a scenario-based experiment, while providing high internal validity, may not perfectly reflect the complexities of real-world information consumption, where exposure is often fragmented and less focused. Field studies or analyses of real social media data could complement these findings.

Third, this study’s cross-sectional design captures an immediate response; longitudinal research could employ observational methods, such as social media sentiment analysis. Tracking real-time fluctuations in brand sentiment before and after major sustainability disclosures would provide valuable ecological validation of the experimental effects observed in this study.

Fourth, a notable limitation of this study is the operationalization of the ‘influencer’ source as a generic category. Recent literature distinguishes between generalist fashion influencers and specialized ‘sustainable fashion influencers’ (SFIs) or ‘greenfluencers’ [49]. Research suggests that SFIs possess a unique form of credibility derived from their consistent advocacy and perceived authenticity in the environmental domain [50]. Unlike the general influencer used in our scenarios—who might be perceived as commercially driven—an SFI might mitigate the skepticism we observed, particularly regarding social sustainability claims. Jacobson and Harrison [49] highlight that for sustainable content, the alignment between the influencer’s lifestyle and the message is critical for trust. Therefore, we can argue that our study established the “baseline penalty” for influencers in the social domain, while future research could determine if “greenfluencers” can overcome this penalty by being perceived as recognized sustainability advocates.

Fifth, our use of real, familiar brands (the participant’s most frequently purchased brand) rather than fictitious ones may be interpreted as a methodological limitation. While experimental protocols often favor fictitious brands to maximize internal validity and eliminate the confounding effects of pre-existing brand associations [51], this study prioritized ecological validity. Trust is inherently relational; measuring a breach of trust requires a pre-existing psychological bond to be meaningful. Using fictitious brands risks generating artificial responses where participants have no emotional investment or ‘skin in the game’ [40]. However, we acknowledge that using real brands introduces uncontrolled variance, as strong prior brand equity can act as a buffer against negative information, potentially creating ceiling effects in the trust metrics, which we aimed to control by measuring pre-experimental brand trust and using it in the regression analysis as a predictor variable. However, future research could replicate this design using fictitious brands to isolate the cognitive processing of sustainability signals from the buffering effects of established brand loyalty.

Future studies could also build on our findings by exploring a wider range of information sources (e.g., traditional news media, user-generated reviews) and product categories beyond fashion.

Supplementary Materials

The moderator’s outline used in Study 1 and the complete set of the scenarios employed in Study 2 can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010412/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.Z. and A.K.M.; Methodology, P.Z.; Validation, P.Z.; Formal analysis, P.Z.; Investigation, P.Z. and A.K.M.; Data curation, A.K.M.; Writing—original draft, P.Z. and A.K.M.; Writing—review & editing, P.Z. and A.K.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to legal regulations (https://www.sgh.waw.pl/en/ethics-sgh (accessed on 21 November 2025)).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article and Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Lewin, L.D.; Warren, D.E. Hypocrites! Social media reactions and stakeholder backlash to conflicting CSR information. J. Bus. Ethics 2025, 196, 419–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvarado-Herrera, A.; Bigne, E.; Aldas-Manzano, J.; Curras-Perez, R. A scale for measuring consumer perceptions of corporate social responsibility following the sustainable development paradigm. J. Bus. Ethics 2017, 140, 243–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, N.N.T.; Pham, T.T. Linking corporate social responsibility to customer behaviours: Evidence from fashion industry in a developing economy. Soc. Responsib. J. 2025; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Catlin, J.R.; Luchs, M.G.; Phipps, M. Consumer perceptions of the social vs. environmental dimensions of sustainability. J. Consum. Policy 2017, 40, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shea, C.T.; Hawn, O.V. Microfoundations of corporate social responsibility and irresponsibility. Acad. Manag. J. 2019, 62, 1609–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, J.; Sommers, R. When does moral engagement risk triggering a hypocrisy penalty? Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2022, 47, 101404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, T.; Lutz, R.J.; Weitz, B.A. Corporate hypocrisy: Overcoming the threat of inconsistent corporate social responsibility perceptions. J. Mark. 2009, 73, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weismueller, J.; Harrigan, P.; Wang, S.; Soutar, G.N. Influencer endorsements: How advertising disclosure and source credibility affect consumer purchase intention on social media. Australas. Mark. J. 2020, 28, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer marketing: How message value and credibility affect consumer trust of branded content on social media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visentin, M.; Pizzi, G.; Pichierri, M. Fake news, real problems for brands: The impact of content truthfulness and source credibility on consumers’ behavioral intentions toward the advertised brands. J. Interact. Mark. 2019, 45, 99–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguinis, H.; Bradley, K.J. Best practice recommendations for designing and implementing experimental vignette methodology studies. Organ. Res. Methods 2014, 17, 351–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khandai, S.; Mathew, J.; Yadav, R.; Kataria, S.; Kohli, H.S. Ensuring brand loyalty for firms practicing sustainable marketing: A roadmap. Soc. Bus. Rev. 2022, 18, 219–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koschate-Fischer, N.; Gärtner, M.M. A continuous measurement approach for brand trust. Mark. Lett. 2015, 26, 485–497. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhuri, A.; Holbrook, M.B. The chain of effects from brand trust and brand affect to brand performance: The role of brand loyalty. J. Mark. 2001, 65, 81–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Kumar, N. Sustainable marketing initiatives and consumer perception of fast fashion brands. Text. Leath. Rev. 2024, 7, 104–124. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann, H.L.; Martinez, L.M.; Martinez, L.F. Sustainability efforts in the fast fashion industry: Consumer perception, trust and purchase intention. Sustain. Account. Manag. Policy J. 2020, 12, 571–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, A. How green sustainability efforts affect brand-related outcomes. Asia-Pac. J. Bus. Admin. 2023, 16, 1182–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Policarpo, M.C.; Apaolaza, V.; Hartmann, P.; Paredes, M.R.; D’Souza, C. Social cynicism, greenwashing, and trust in green clothing brands. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1950–1961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, H.; Kim, Y. An empirical test of the triple bottom line of customer-centric sustainability: The case of fast fashion. Fash. Text. 2016, 3, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Yang, Y. Exploring the role of green attributes transparency influencing green customer citizenship behavior. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 1473–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezbaruah, S.; Dhir, A.; Talwar, S.; Tan, T.M.; Kaur, P. Believing and acting on fake news related to natural food: The influential role of brand trust and system trust. Br. Food J. 2021, 124, 2937–2962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grolleau, G.; Caswell, J.A. Interaction between food attributes in markets: The case of environmental labeling. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2006, 31, 471–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.P.; Posavac, S.S. Prepurchase attribute verifiability, source credibility, and persuasion. J. Consum. Psychol. 2001, 11, 169–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.L.; Mattila, A.S. Improving consumer satisfaction in green hotels: The roles of perceived warmth, perceived competence, and CSR motive. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2014, 42, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doney, P.M.; Cannon, J.P. An examination of the nature of trust in buyer–seller relationships. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.H.; Peng, S. How to repair customer trust after negative publicity: The roles of competence, integrity, benevolence, and forgiveness. Psychol. Mark. 2009, 26, 572–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grégoire, Y.; Fisher, R.J. Customer betrayal and retaliation: When your best customers become your worst enemies. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2008, 36, 247–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dietz, T.; Kalof, L.; Stern, P.C. Gender, values, and environmentalism. Soc. Sci. Q. 2002, 83, 353–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K.K.; Tamilmani, K.; Rana, N.P.; Patil, P.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Nerur, S. Advances in social media research: Past, present and future. Inf. Syst. Front. 2018, 20, 531–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarmeas, D.; Leonidou, C.N. When consumers doubt, watch out! The role of CSR skepticism. J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1831–1838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellen, P.S.; Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A. Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2006, 34, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, L.A.; Webb, D.J.; Harris, K.E. Do consumers expect companies to be socially responsible? The impact of corporate social responsibility on buying behavior. J. Consum. Aff. 2001, 35, 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krueger, R.A. Focus Groups: A Practical Guide for Applied Research; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Flick, U. An Introduction to Qualitative Research, 6th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kuckartz, U. Qualitative Text Analysis: A Guide to Methods, Practice and Using Software; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Patton, M.Q. Enhancing the quality and credibility of qualitative analysis. Health Serv. Res. 2000, 34, 1189–1208. [Google Scholar]

- Miles, M.B.; Huberman, A.M.; Saldaña, J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook, 3rd ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Saldaña, J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers, 4th ed.; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Zaborek, P.; Kurzak Mabrouk, A. The role of social and environmental CSR in shaping purchase intentions: Experimental evidence from the cosmetics market. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.C.; Amir, O.; Lee, L. Keeping it real in experimental research—Understanding when, where, and how to enhance realism and measure consumer behavior. J. Consum. Res. 2017, 44, 465–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Ogden, D.T. To buy or not to buy: A social dilemma perspective on green buying. J. Consum. Mark. 2009, 26, 376–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, D.J.; Mohr, L.A.; Harris, K.E. A re-examination of socially responsible consumption and its measurement. J. Bus. Res. 2008, 61, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J.F.; Babin, B.J.; Black, W.C.; Anderson, R.E.; Tatham, R.L. Multivariate Data Analysis, 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, MA, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Malhotra, N.K. Marketing Research: An Applied Orientation, 6th ed.; Pearson: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Fornell, C.; Larcker, D.F. Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 1981, 18, 39–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garson, G.D. Testing Statistical Assumptions, 2012 ed.; Statistical Publishing Associates: Asheboro, NC, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, N.; Skurka, C.; Madden, S. The effects of self-disclosure and gender on a climate scientist’s credibility and likability on social media. Public Underst. Sci. 2024, 33, 692–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wąsowicz-Zaborek, E. Cultural determinants of social media use in world markets. Folia Oeconomica Stetin. 2020, 20, 423–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobson, J.; Harrison, B. Sustainable fashion social media influencers and content creation calibration. Int. J. Advert. 2022, 41, 150–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Jeong, H.J. Crafting green influence: The role of self-disclosure and influencer type in generation Z’s Pro-environmental engagement. J. Bus. Res. 2025, 201, 115687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geuens, M.; De Pelsmacker, P. Planning and conducting experimental advertising research and questionnaire design. J. Advert. 2017, 46, 83–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.