Abstract

The role of soil microbial communities in soil organic matter (OM) decomposition, transformation, and the global nitrogen (N) and carbon (C) cycles has been widely investigated. However, a comprehensive understanding of how specific agricultural practices and OM inputs shape microbial-driven processes across different European pedoclimatic conditions is still lacking, particularly regarding their effectiveness in mitigating greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. This systematic review synthesizes current knowledge on the biotic mechanisms underlying soil C sequestration and GHG reduction, emphasizing key microbial processes influenced by land management practices. A rigorous selection was applied, resulting in 16 eligible articles that addressed the targeted outcomes: soil microorganism biodiversity, including microbiome composition and other common Biodiversity Indexes, C sequestration and non-CO2 GHG emissions (namely N2O and CH4 emissions), and N leaching. The review highlights that, despite some variations across studies, the application of OM enhances soil microbial biomass (MB) and activity, boosts soil organic carbon (SOC), and potentially reduces emissions. Notably, plant richness and diversity emerged as critical factors in reducing N2O emissions and promoting carbon storage. However, the lack of methodological standardization across studies hinders meaningful comparison of outcomes—a key challenge identified in this review. The analysis reveals that studies examining the simultaneous effects of agricultural management practices and OM inputs on soil microorganisms, non-CO2 GHG emissions, and SOC are scarce. Standardized studies across Europe’s diverse pedoclimatic regions would be valuable for assessing the benefits of OM inputs in agricultural soils. This would enable the identification of region-specific solutions that enhance soil health, prevent degradation, and support sustainable and productive farming systems.

1. Introduction

Soil microorganisms play a central role in the decomposition and transformation of organic matter (OM) through diverse metabolic pathways; thus, they are crucial in responding to climate changes in agriculture, through nutrient cycles, sequestration of soil carbon (C) and greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions [1,2,3]. Agricultural fields represent a significant source of GHG emissions, mainly methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O); however, at the same time, they also hold an untapped potential for mitigation of these emissions, particularly through C sequestration, depending on the land use and management practices [4].

Soil C sequestration is the process by which CO2 is removed from the atmosphere and stored in the soil C pool. This process is primarily mediated by plants through photosynthesis and rhizodeposition, with C stored in the form of soil organic C (SOC) [5]. The co-benefits of soil C sequestration include advancing food and nutritional security, improving water renewability and quality, enhancing biodiversity, and strengthening elemental recycling. Soils in different agroecosystems, however, are often strongly depleted of their SOC stock and degraded due to intensive land use, soil management practices and farming systems. Restoring soil quality requires increasing SOC stock through sustainable management practices (e.g., conservation agriculture), which create a positive C budget [6]. Soil microbial communities play a pivotal role in C cycling within soil systems, returning C that enters the soil from above-ground plant production to the atmosphere as CO2 and contributing to the stabilization of organic C, thereby influencing soil C storage and turnover [7,8]. Notably, bacterial network interactions are positively associated with the rate of C fixation; for example, Proteobacteria spp. promote the activity of other microbes that contribute to CO2 fixation [9].

On the other hand, microbial activity, particularly nitrification and denitrification, is mainly responsible for the production of soil nitrous oxide (N2O), a gas with a global warming potential 298 times greater than that of CO2 [10]. N2O contributes to ozone depletion and is released by microbial processes. Various studies have linked N2O emissions to microbial functional diversity [11]. The application of mineral fertilizers, particularly ammonium-based fertilisers, has significantly increased agricultural yields and economic returns to farmers worldwide. However, agricultural intensification and the associated rise in nitrogen (N) applications have also heightened the risk of systemic losses through N2O emissions and N leaching [12,13]. Non-fertilized soils exhibit up to 78% less denitrification than ammonium nitrate fertilised soils [14]. During nitrification, the ammonium added as fertilizer, fixed from the atmosphere by legumes, or mineralized from soil OM, crop residues, or other inputs, is oxidized to nitrite and eventually to nitrate in a series of reactions that can also produce N2O. Likewise, when denitrifiers use nitrate as an electron acceptor under low-oxygen conditions, N2O is an intermediate product that can readily escape to the atmosphere [4]. When crops compete with microbes for available N, N2O fluxes tend to be lower.

Nitrogen leaching is one of the most common forms of aquatic system pollution, leading to high nitrate concentrations in drinking water, which can cause serious health issues [15]. Additionally, N leaching results in the loss of a nutrient resource for plants, leading to lower yields and significant economic losses for farmers. Controlled utilization of N and irrigation inputs can minimize the losses and emissions, thereby improving water quality [16].

Terrestrial ecosystems also influence emissions and removal of the atmospheric methane (CH4) in soils. More than one-third of global CH4 emissions occur through the microbial breakdown of organic compounds in soil under anaerobic conditions. Both CH4 production and oxidation occur simultaneously, since methanogenic (CH4-producing) and methanotrophic (CH4-consuming) microorganisms coexist in soils. Consequently, emissions of biogenic CH4 from soils would be significantly higher if not for the methanotrophic microorganisms that oxidize CH4 before it escapes the soil, reducing the amount of CH4 released into the atmosphere [17]. In the global CH4 budget, agricultural soils are typically considered minor net emitters of CH4 [18], though there is ongoing debate regarding whether they act as a net source or sink for methane, in contrast to wetlands (regarded as the dominant natural source) and upland soils (regarded as the primary biological sink) [19].

Recently, effective and climate-friendly measures and technologies for C sequestration and GHG emission reduction have been proposed for farmland soils. These include the application of organic matter (OM) inputs, such as biochar, returning straw to the field, and applying organic fertilizer and biological soil improvers. Among sustainable agricultural strategies and management systems, practices such as crop rotation, cover crops, no tillage (NT) or reduced tillage, beyond biodiversity embracing, livestock and crop integration, and agroforestry, are those more commonly adopted. Soil microbes play a crucial role in the effectiveness of these mitigation measures and technologies, but studies on the role of microorganisms in GHG emissions from farmland are still insufficient [20], and the high microbial diversity in soils still remains underexplored.

The scientific literature has provided evidence regarding the specific relationships between OM inputs or certain agricultural management practices with soil microorganisms and C sequestration [21,22,23], or with soil microorganisms and non-CO2 GHG emissions, particularly N2O emissions, CH4 emissions, and N leaching [24,25,26]. A recent review examining the impact of soil management practices on the trade-offs between soil carbon sequestration, N2O and CH4 emissions, and nitrogen leaching—while focusing on abiotic factors—highlighted a persistent gap in understanding these complex interactions [27].

Therefore, the effects of soil microorganisms on C and N dynamics need to be addressed to allow correct evaluation of the success of sustainable management practices in supplying their ecosystem services [28,29]. In the frame of the H2020 European Joint Programme on Soil (EJP-Soil), the ΣOMMIT project (Sustainable Management of soil Organic Matter to Mitigate Trade-offs between C sequestration and nitrous oxide, methane and nitrate losses) had the objective to evaluate trade-offs and synergies between soil C sequestration, nitrous oxide, methane and nitrate losses as affected by soil management options aimed at increasing soil C storage. This systematic review, as a specific task of the ΣOMMIT project, provides a literature survey focused on the relationships between soil microorganisms and microbiomes and the trade-offs between C sequestration and non-CO2-GHG emissions, in farming systems applying OM inputs (e.g., organic wastes, biochar, digestate) or other management systems in European soils. New insights will help assess the potential effects of OM inputs and other practices in arable farming on the abundance, diversity, and activity of biotic drivers, ultimately contributing to climate change mitigation.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Procedure for the Systematic Review

The PRISMA protocol (“Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses”) [30] was followed [PRISMA 2020 checklist in Supplementary Material S1]. The main requirements of the PRISMA protocol, detailed below, are: (i) the accurate and precise definition of the research objective of the study; (ii) the selection of information sources; (iii) the definition of the eligibility criteria and the exclusion criteria.

- (i)

- Definition of the research objective of the study

A clear research question regarding the objective of this review has been defined, including the key terms to perform the search. The research question was based on PICO [31], applied to a search addressing soil microorganisms in relation to the trade-offs between C sequestration, N2O, and other non-CO2 GHG emissions, as reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

PICO acronym, general description and explication of the PICO components, key terms and sentences used in the research question for the search in the current review.

The research question was formulated as follows: “What are the effects of OM inputs on soil microorganisms in relation to C sequestration and N2O emissions in EU agricultural soil?”. To avoid making the bibliographic search overly complex, the number of keywords has been minimized. In this regard, it is assumed that any full-text reporting on CH4 emissions and/or N leaching would generally mention N2O emissions. However, only N2O emissions were explicitly reported (see Table 1), while no keywords were used to search for CH4 emissions or N leaching.

- (ii)

- Selection of information sources

The database selected for the search was Scopus (https://www.scopus.com, accessed on 10 November 2025), which was considered the most suitable for this study due to its broad journal coverage, advanced keyword search capabilities, and citation analysis tools focused on recent literature. This choice allowed for a comprehensive overview of all published research [32]. The search was conducted in March 2023.

- (iii)

- Eligibility criteria

The eligibility screening of the numerous articles retrieved from the scientific literature involved the development, testing and application of the selection criteria listed in Table 2, following the guidelines in [33]. Preliminary searches across various databases revealed that the number of required keywords to address the research question was excessively high and difficult to manage. At the same time, including all selected keywords significantly limited the number of retrieved articles. Therefore, to avoid overlooking valuable information, in very few cases studies that had not been carried out in field were also included. Only a few studies reporting microcosm experiments were retained, as it is well-documented that, in the short-term, the microbial community modifications can be detected with greater precision, whereas specific biological effects in field experiments may be masked or influenced by pedoclimatic variations [34,35,36].

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria for the inclusion and the exclusion of manuscripts.

Regarding the literature search, the following considerations are noteworthy. The OM inputs considered in this study, reported in Table 2, were like in Valkama et al. [37]. To search for microbial diversity, in addition to the general terms related to microorganisms (microb* OR microorganism* OR arche* OR bacteria* OR fung*), the following biological parameters and Biodiversity Indexes (BIs) related to microbial abundance and diversity were included: “Microbial biomass”, “Microbial composition”, “Shannon”, “Simpson”, “Fisher”, “OTU”, “ASV”, “Richness”, “Evenness”, “Relative Abundance”, “Phylogenetic diversity” and “Diversity”. The search focused on studies localized in Europe. Selected studies ranged from 2005 to August 2022, the starting period was chosen due to the introduction of sequencing-by-synthesis technology by 454 Life Science in 2005 [38]. After evaluating the eligibility criteria through a preliminary analysis of titles and abstracts, the remaining articles were examined carefully, with respect to terms related to C sequestration, N2O emissions and possibly other non-CO2 GHG emissions, such as CH4 emissions and N leaching. The advanced search in Scopus (https://www.scopus.com/search/form.uri?display=basic#basic, accessed on 10 November 2025), within “Documents” > “All fields”, was carried out through the query sentences in Table 1, all of them linked by the Boolean operator “AND”.

2.2. Abstract Bibliometric Analysis

The abstracts of the articles selected for this systematic review were extracted and examined using the Bibliometrix package within the R Studio (version 4.5.1) environment [39]. Bibliometrix uses the “co-occurrence method” to cluster keywords based on their frequency in articles, revealing thematic relationships [40]. Network analysis was performed using Walktrap algorithm to further clarify connections between key concepts in the abstracts, and to identify predominant topics and their interconnections. A word cloud was generated to visually represent the frequency of terms occurring in the abstracts. Furthermore, thematic mapping was utilized to categorize and visualize clusters of related terms and concepts within the abstracts. This technique helped identify overarching themes and patterns in the literature, aiding in the contextualization and interpretation of the findings. Raw data, including the BibTeX file, are provided in Supplementary Materials S2 and S3.

3. Results

3.1. Systematic Review and Descriptive Analysis

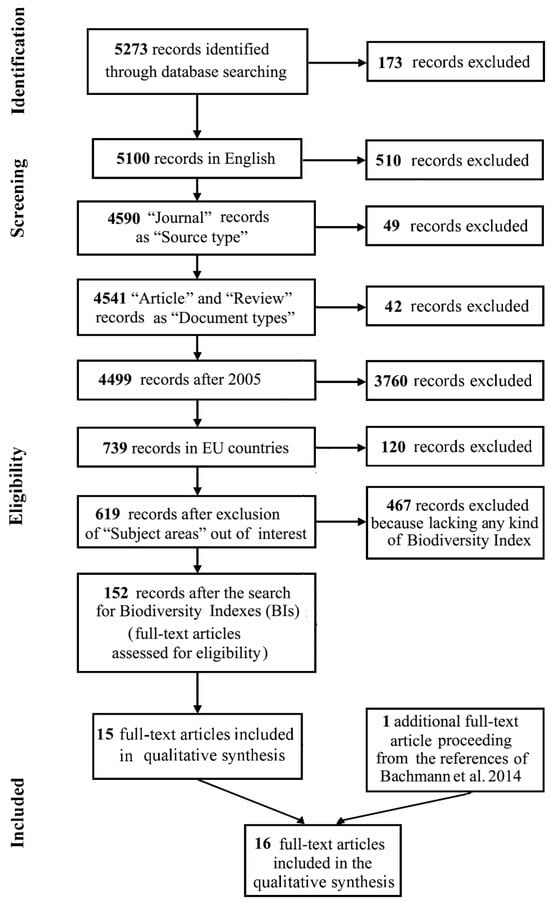

Following the schematic procedure reported in Figure 1, 16 manuscripts from the scientific literature were finally analysed [Supplementary Materials S4].

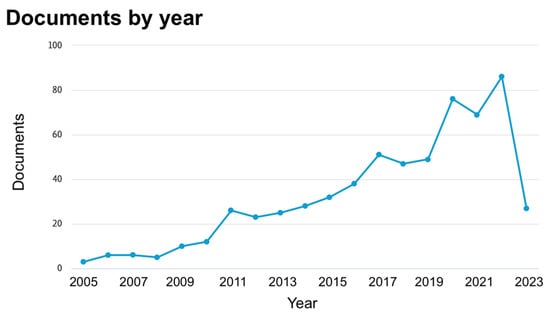

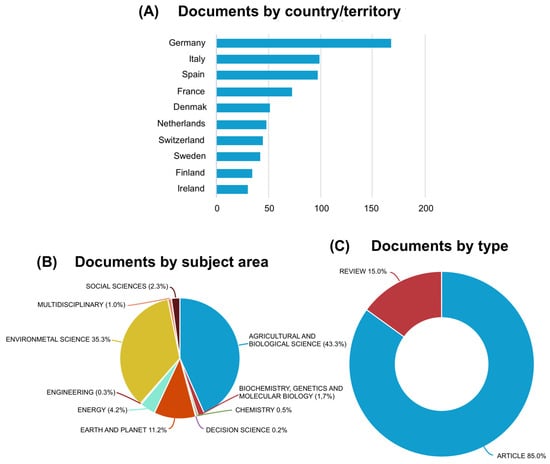

In detail, starting from 5273 total initial items, the following were removed serially: 173 for being in a non-English language; 510 because the “Source type” was not “Journal”; 49 for not being “Article” or “Review”; 42 for being published before 2005; 3760 for being from non-EU countries; and 120 for being from unrelated “Subject areas”. After completing the screening and assessing eligibility criteria, 619 full-text articles were obtained (Table 2; Figure 1). The number of articles related to the study’s objective showed an increasing trend from 2005, reaching 88 in 2022 [Figure 2]. More than a quarter of these articles originated from Germany [Figure 3A], 43.3% were in the “Agricultural and Biological Science” area, and 35.3% were in “Environmental Science” [Figure 3B]; 85% were articles and 15% were reviews [Figure 3C].

To refine the search for relevant manuscripts, a set of Biodiversity Indexes (BIs) was chosen for the microbial data collection template. As shown in Figure 1, of the initial 619 items that complied with the eligibility criteria, only 152 of them including BIs were extracted from the pool. In screening for the presence of terms related to BIs, 8 records resulted for “Shannon”, 42 records for “Fisher”, 47 records for “Richness”, 73 records for “Simp-son”, 10 records for “Evenness”, 1 record for “Phylogenetic diversity” and 8 records for “Relative abundance”. It has to be noted that, in some cases, the BI term was only present in the reference section of a manuscript. For example, many records contained the term “Simpson”, referring to highly cited studies authored by “Simpson G”.

After a preliminary analysis of the Title and the Abstract of these 152 articles, a general scarcity of research encompassing microbial composition and diversity, and at the same time both C sequestration and N2O emissions, was observed. Only manuscripts with explicit evidence of a clear treatment—such as the application of one or more OM inputs or specific agricultural management practices—were selected, following a rigorous screening based on the eligibility criteria outlined in Table 2.

Finally, 15 research articles were selected from Scopus. The article selection process followed rigid criteria to identify studies that simultaneously reported information and results on soil microorganisms, C sequestration, and non-CO2 GHG emissions. These 15 articles were considered representative of the state-of-the-art knowledge regarding the integrated effects of OM fertilization and other agricultural practices on soil microorganisms and the trade-offs between C seq and GHG non-CO2 emissions, although not all of them provided insights into all three topics. For this reason, among the final selected articles, those studies including agricultural management systems (e.g., tillage) rather than OM input application were also kept for the systematic review.

Additionally, another manuscript [41], Johansen et al. 2013, was selected and included in this study, proceeding from the References of Bachmann et al. (2014) [42] [Figure 1; Supplementary Material S4]. For the 16 manuscripts, the main information on the geographical climatic location, the year(s) and duration of experiments, the crops, the OM inputs and/or the agricultural management practice, and the outcomes in terms of soil microbial data and BIs, C sequestration, and non-CO2 emissions is summarized in Table 3. No studies related to Archaea were found, so the current review only encompasses Bacteria and Fungi.

Figure 1.

Flow of information through the different phases of a systematic review according to the PRISMA protocol [30] for the search carried out in the Scopus database. 1 additional full-text article proceeding from the references of Bachmann et al. 2014 [42].

Figure 2.

Number of documents (scientific journal articles) by year, from 2005 to March 2023, retrieved from the key word search in Scopus.

Figure 3.

(A) Number of documents by affiliated country/territory; (B) number of documents by subject area; (C) number of documents by type.

Among the 16 studies included in the final selection, the majority examined the trade-offs between carbon sequestration and non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions (notably N2O) and concurrently presented data related to soil microbial dynamics. However, during an in-depth analysis of the full texts, it was found that not all articles fully adhered to the inclusion criteria. In some cases, the articles focused specifically on the relationships between soil C sequestration and microorganisms or between non-CO2 GHG emissions and microorganisms, with one of the three topics only discussed rather than directly evaluated at the experimental level. For example, Ribas et al. [43] explored the potential effect of plant diversity on yield and GHG exchanges in forage mixtures using slurry for fertilization. The authors measured CO2, N2O, and CH4 emissions but did not assess soil microorganism variations, even though soil microorganism effects were often mentioned and discussed throughout the paper. This article was included in the current review because, more interestingly, it proposed plant diversity, particularly N-rich crops, as a tool to regulate gas balances.

Table 3.

Main information related to the studies reported in the 16 finally selected Original Research manuscripts from Scopus focused on in this systematic review.

Table 3.

Main information related to the studies reported in the 16 finally selected Original Research manuscripts from Scopus focused on in this systematic review.

| Manuscript N° | Environmental Zone in Europe | Country, City, Location | Years of Experiment and Duration | Cultivated Crops | OM Input/Agricultural Management Practice | Microbial Data and Biodiversity Indexes (BIs) | C Sequestration and Related Data | N2O Emissions and Related Data | CH4 Emissions or N Leaching Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1–Anastopoulous et al. 2019 [44] | Mediterranean | Greece, Pathos (Cyprus) | 2017, 5 and 34 days after application of treatments | N.A. | Organic agricultural wastes from orange, mandarin, and banana peels vs. ammonium nitrate | Soil microbial communities were analysed through: - qPCR of denitrifiers (nirK, nirS, nosZ I and nosZ II) - 16S rRNA seq. - BI: Shannon Index | - Initial soil organic carbon - CO2 emissions | - Initial soil N - Initial soil nitrate N - N2O emissions | N.A. |

| 2—Bachmann et al. 2014 [42] | Continental | Germany, Mecklenburg-West Pomerania | 2008, 3 years | Maize | Digestate | Activity of enzymes connected to soil P cycle: - dehydrogenase - alkaline phosphatase - acid phosphatase | - Total C content - TOC - CO2 efflux | - Total N - NH4-N - N as calcium ammonium nitrate - N-uptake (in kg ha−1) | N.A. |

| 3—Badagliacca et al. 2021 [29] | Mediterranean | Italy, Sicily, Pietranera Farm located in the North of Agrigento | 2013–14, 23 years | Durum wheat (Triticum durum), faba bean (Vicia faba L.) | - Conservation system: NT vs. CT - Crop sequence: wheat monoculture vs. wheat-faba bean rotation | - Microbial Biomass C (MBC) - Microbial Biomass N (MBN) - Basal Respiration (BR) - Abundance of main microbial groups by phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) - Microbial quotient | - TOC - Labile Organic Carbon (LOC) | - Total N | N.A. |

| 4—Badagliacca et al. 2022 [45] | Mediterranean | Italy, Calabria | 2019–20, 1 year | Durum wheat (Triticum durum) | Conservation system: NT vs. CT | - PFLA analysis - Activity of enzymes connected to C, N, P and S cycling. For C cycling: α-and β-glucosidase, α- and β-galactosidase, α- and β- mannosidase, β-1,4-glucanase, β-1,4-xylanase, α-arabinase, β-D-glucuronidase. For N cycling: N-acetyl-b-D-glucosaminidase, leucine amino-peptidase, trypsin-like protease | - Soil permanganate oxidizable C (POxC) as labile C | - Nitrate-N (NO3−-N) and ammonium-N (NH4+-N) - total soluble N (TSN) - extractable organic N | N.A. |

| 5—Dicke et al. 2015 [46] | Continental | Germany, Berge | 2012–13, (October 2021 to September 2013) | Winter wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) | Biochar (pyrolisis char and hydrochars) and digestate | Soil microbial communities were analysed through: - qPCR of nosZ denitrifiers | - C content in soil and in OM inputs (as %DM) | - N2O emission (cumulative annual emission as of N2O-N in kg ha−1 a−1) - Soil inorganic N (NH4+-N and NO3—N in mg kg−1 soil) - In the OM inputs: N (%DM), NH4+-N and NO3-N in mg kg−1 | N.A. |

| 6—Drost et al. 2020 [47] | Microcosm experiment | The Netherlands, Wageningen | 2017, short-term time-course, 50 days | Wheat was grown and harvested prior to soil collection | Cover crops [monocultures of oat (Avena strigosa), vetch (Vicia sativa), radish (Raphanus sativus), a mixture of 3 species and a mixture of 15 species | - Fungal biomass by ergosterol - Bacterial biomass by 16S rRNA gene qPCR - Fungal biomass C - Bacterial biomass C - Total (fungal + bacterial) microbial biomass C - Microbial functional diversity by Biolog ECO plates | - C content of the added plant material - CO2 fluxes | - N2O fluxes - Cumulative fluxes - Plant available N concentration | N.A. |

| 7—Johansen et al. 2013 [41] | Microcosm experiment | Denmark, Taastrup | 2011, short-term time-course, 9 days | Barley (Hordeum vulgare), perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), white clover (Trifolium repens), bread wheat (Triticum aestivum) | - OM inputs: (a) raw cattle slurry; (b) anaerobically digested cattle slurry/maize; (c) anaerobically digested cattle slurry/grass-clover; (d) fresh glass-clover (green manure) Crop rotation: - spring barley (Hordeum vulgare) undersown with grass (Lolium perenne) - clover (Trifolium repens), grass-clover, grass-clover and winter wheat (Triticum aestivum) | - PLFA analysis for microbial biomass and community composition - Catabolic response profiling (functional diversity) | - Available organic C - CO2 emissions | - Mineral N - N2O emissions | N.A. |

| 8—Lori et al. 2020 [48] | Terrestrial Model Ecosystems (TMEs) | For arable cropping system in Switzerland, Therwil; for mountain grasslands in France, Vercors; for agroforestry systems in Portugal, Montemor-o-Novo | Autumn 2015, 1 year | - Ecological intensive vs. conventional intensive, in three agricultural systems: - arable cropping (grassland in rotation) - mountain grassland - agroforestry - Different soil types, N fertilizer application (slurry, synthetic, cow manure), tillage system (CT, reduced tillage and NT), and vegetation cover (% of grasses, legumes and others) | - Enzyme activity involved in degradation of N containing molecules: leucine aminopeptidase activity (LAP) for protein degradation potential and β-1,4-N-acetylglucosaminidase (NAG) for chitin and peptidoglycan degradation. - Abundance of proteolytic microbial communities by qPCR on alkaline (apr) and neutral (npr) metallopeptidase genes. - Community and diversity composition of apr encoding communities. BI: richness, evenness and Shannon Index. | - Soil C content | - Applied N fertilization - Soil N content - Soil dissolved mineral and organic N | NO3− content in leachates | |

| 9—Lubbers et al. 2020 [49] | Microcosm experiment | Netherland, Droevendaal Agricultural | 120 days | Absent | Hay residue | - Microbial Biomass N (MBN) | - Dissolved organic C - CO2 flux measurement | - N2O flux - Key physico-chemical factors influencing N2O emissions, including total dissolved N, ammonia (NH+), nitrate and nitrite (NO− and NO−), dissolved organic N | N.A. |

| 10—Niklaus et al 2016 [50] | Continental | Germany, Jena | 2007–2008, long-term (2 years) field experiment | Experimental grassland communities established in 2002 | Plant species richness Synthetic NPK fertilization | - Nitrifyng (NEA) and denitrifying (DEA) enzyme activities - Bacterial nitrifiers by qPCR of nirK (copper nitrite reductase) and nirS (cd1 nitrite reductase) genes - Bacterial denitrifiers by qPCR of nitrite oxido-reductase gene (nxrA) from Nitrobacter-like nitrite-oxidizing bacteria (NOB). - Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) qPCR | Authors suggest that plant diversity could influence C storage by affecting soil microbial communities and their ability to process OM, which indirectly impacts carbon sequestration. | - Soil-atmosphere N2O fluxes - Soil inorganic N concentrations (NH4+ and NO3−) | Soil-atmosphere CH4 fluxes |

| 11—Panico et al. 2020 [51] | Mediterranean | Italy, Ponticelli, near Naples | 2018, 6 months | Sorghum (Sorghum bicolor L.), sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.) | Conventional agricultural practice | - Microbial biomass expressed ad microbial C - Microbial respiration (CO2 evolution from soil samples) - Total fungal biomass expressed as fungal C - Soil microbial quotient (qCO2) - Soil microbial activity and functional diversity - BIs: Catabolic Evenness and Shannon Index | - Soil C content - Soil organic C content | - Soil inorganic N concentrations (NH4+ and NO3−) - N2O emissions | N.A. |

| 12—Ribas et al. 2015 [43] | Mediterranean | Spain, Catalan Central Depression, Castellnou d’Ossó | Spring 2008, 4 months | Tall fescue (Festuca arundinacea), alfalfa (Medicago sativa), chicory (Cichorium intybus) | - Plant species diversity. - Three N fertilization levels with filtered pig slurry | Indirect assessment of microbial activity through the effects of plant diversity on soil conditions that influence gas emissions | - CO2 gas exchange rate | - Soil inorganic N content - N2O gas exchange rate - NH3 gas exchange rate | CH4 gas exchange rate |

| 13—Rosinger and Bonkowski 2021 [52] | Continental | Garzweiler mines, ca. 10 km south of Mönchengladbach | 2019, 7 years | Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) | - Reclaimed soils from agricultural post-mining chronosequence. - Wheat and barley crop rotation - Mineral fertilization (NPK and calcium ammonium nitrate) - Compost addition | - Microbial Biomass C (MBC) - Microbial Biomass N (MBN) - Basal Respiration (BR) | - Dissolved organic carbon - Soil organic carbon | - Total dissolved nitrogen | N.A. |

| 14—Rosinger et al. 2022 [53] | Continental | Garzweiler mines, ca. 10 km south of Mönchengladbach | 2018, 33 years | Alfalfa (Medicago sativa) | - Reclaimed soils from agricultural post-mining chronosequence - Wheat and barley crop rotation - Mineral fertilization (NPK and calcium ammonium nitrate) - Compost addition | - Microbial Biomass C (MBC) - Microbial Biomass N (MBN) - Basal Respiration (BR) | - Dissolved organic carbon - Soil organic carbon | - Total dissolved nitrogen | N.A. |

| 15—Rummel et al. 2020 [54] | Continental | Germany, South of Göttingen | 2016, 22 days | Maize (Zea mays) | - Two N fertilizer levels (N1, N2) - Three litter addition treatments: control, root, root+shoot) | - Bacterial community structure by 16S rRNA gene sequencing - BIs: Shannon, Simpson, PD Index | - Organic carbon as water-extractable organic carbon (WEOC) | - N2O fluxes - Soil mineral N - Net N mineralization | N.A. |

| 16—Zistl-Schlingmann et al. 2020 [55] | Continental | Germany, the Graswang and Fendt sites | 2017, 6 years | Montane grassland | - 15N cattle slurry application - Extensive vs. intensive management - Control climate vs. reduced precipitation (+2 °C) | - Microbial Biomass N (MBN) | - Soil organic C | - Soil inorganic N concentrations (NH4+ and NO3−) - Dissolved organic N - Total N | N leaching rate |

“N.A.” stands for “Not Available”.

In the surveyed literature, soil microbial status was represented by various parameters, often by microbial biomass (e.g., microbial biomass carbon and microbial biomass nitrogen, MBC and MBN) and/or by basal respiration (BR). Soil microbial communities and their abundances were frequently investigated by 16S rRNA or by phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs) to characterize the main microbial groups. When microbial biodiversity was specifically addressed, the most used BIs were the Shannon and Simpson indexes, richness, and evenness. Some studies also investigated bacterial nitrifiers and denitrifiers, as well as N-cycling related genes via qPCR. C sequestration was mainly evaluated using SOC (sometimes equally defined as TOC for total organic carbon) and total carbon and more indirectly through CO2 fluxes. N2O emissions were almost always measured as fluxes, although in some cases, indirect assessment of total N, inorganic N, dissolved and organic N, was conducted, as these factors influence N2O emissions [56] [Table 3]. One study focused on N leaching by measuring NO3- content in leachates [48], and another measured N leaching rate [55]. Finally, two articles analysed CH4 fluxes [43,50]. In Table 3, the last four columns on the right contain the main parameters measured in the 16 articles related to microorganisms, C sequestration, N2O emissions, CH4 emissions, and N leaching.

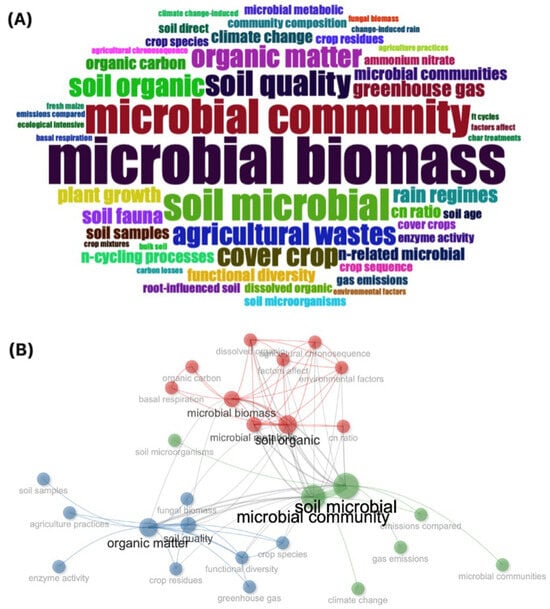

3.2. Network Analysis and Word Cloud

A semantic network map based on word co-occurrence in the 16 finally selected articles was created to highlight how the different research areas interrelate and overlap [Figure 4A]. The nodes clustered into three main groups, suggesting distinct aspects within the relationships between soil microorganisms and greenhouse gas emissions.

Figure 4.

(A) Word Cloud based on bibliometric analysis of the 50 most frequently found words, and (B) co-occurrence network analysis of the 16 scientific articles reported in Table 4. Three clusters were generated: Cluster 1 (red) with high betweenness and centrality scores, Cluster 2 (blue) with closeness centrality, and Cluster 3 (green) with influential nodes based on high PageRank values.

The co-occurrence network analysis revealed three main clusters of keywords [Figure 4B]. A strong association between “microbial biomass” and “organic carbon” (Cluster 1) was found, suggesting that organic matter (OM) inputs enhance microbial activity, promoting carbon sequestration and potentially reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Similarly, “organic matter” (Cluster 2) showed high betweenness centrality, emphasizing its central role in soil quality and functional diversity. Environmental topics such as “microbial community” and “climate change” were grouped in another cluster (Cluster 3). Moreover, nodes like “microbial community” had high PageRank, indicating their significant influence and centrality in studying microbial dynamics under environmental changes [Figure 4B; Supplementary Material S2].

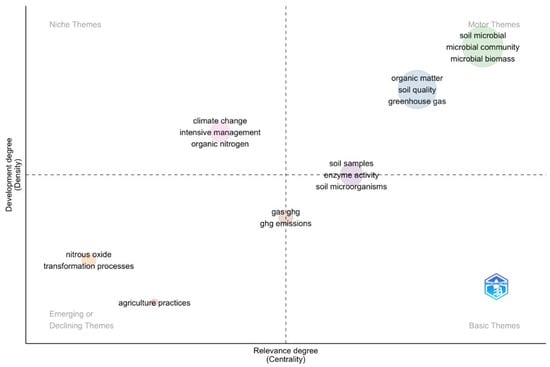

The thematic map analysis showed the complex interactions between the soil microbiome, agricultural practices, and greenhouse gas emissions [Figure 5]. At its core, “soil microbial”, including “microbial community” and “microbial biomass”, emerged as the motor theme. This highlighted the important role of microbial diversity and processes in regulating soil health and carbon dynamics, with high centrality values indicating strong connections to other research areas [Supplementary Material S3]. Nearby, the “organic matter” cluster (including “soil quality” and “greenhouse gas”) was closely linked but distinct, suggesting a complementary focus on how organic inputs influence microbial activity and emissions. Niche themes, such as “climate change”, “intensive management”, and “organic nitrogen”, appeared well-developed but less connected to the central topics, possibly reflecting specialized studies on environmental impacts or specific management practices. On the periphery, emerging themes such as “nitrous oxide” and “transformation processes” suggested growing interest in targeted areas like greenhouse gas mitigation and biochemical pathways in soil.

Figure 5.

Thematic mapping analysis of keywords from the abstracts of the 16 scientific articles using Bibliometrix. The X-axis, “Relevance Degree”, represents the centrality of a topic within the analyzed field. Higher values indicate stronger connections and greater importance within the overall network of keywords. The Y-axis, “Development Degree”, reflects the maturity or advancement of a topic. Higher values indicate well-established topics with significant structural development. The bubble size corresponds to the frequency of occurrence of the associated keywords, with larger bubbles representing more frequently referenced topics, highlighting their prominence in the field. These dimensions enable the categorization of topics into quadrants, identifying emerging, declining, or well-established research areas.

Table 4.

Effects on C sequestration, N2O emissions and soil microorganisms by the different types of agricultural management practices or OM inputs as reported in the articles analysed and classified in this review.

Table 4.

Effects on C sequestration, N2O emissions and soil microorganisms by the different types of agricultural management practices or OM inputs as reported in the articles analysed and classified in this review.

| Article N° (Based in Table 3), First Author and Year of Publication | Type of Agricultural Management Practice or OM Input | Effects on C Sequestration | Effects on N2O Emissions | Effects on Microbiome | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agricultural organic waste | 1-Anastopoulos et al. 2019 [44] | Agricultural waste vs. ammonium nitrate | ↓ (↑soil direct CO2 emissions) | ↓ N2O emissions | ↑ soil microbiome |

| 9-Lubbers et al. 2020 [49] | Hay residues | ↓ (↑soil CO2 emissions) | ↓ N2O emissions | ↑ soil fauna (earthworms) diversity | |

| Biochar, digestate and slurry | 5-Dicke et al. 2015 [46] | Biochar vs. digestate | N.A. | ↓ N2O emissions | ↔ nosZ gene abundance |

| 2-Bachman et al. 2014 [42] | Digestate vs. no digestate (negative control) | ↔ (CO2 efflux) | N.A. | ↓ dehydrogenase and alkaline phosphatase activity | |

| 7-Johansen et al. 2013 [41] | Raw cattle slurry, anaerobically digested cattle slurry/maize, and cattle slurry/grass-clover vs. water and fresh grass-clover | ↑ CO2 emissions | ↔ N2O fluxes (anaerobically digested materials ↑NO3− respect to raw cattle slurry) | ↔ (only small transient changes in soil microbial biomass, function, and community structure by soil total PLFA) | |

| 16-Zistl-Schlingmann et al. 2020 [55] | Cattle slurry under extensive and intensive agricultural management | Under intensive conditions ↓ (↓ SOC) | Under intensive conditions ↑ high gaseous environmental N losses (and soil N mining) | N.A. | |

| Conservation system and crop rotation | 3-Badagliacca et al. 2021 [29] | NT vs. CT | ↑ SOC | ↑ microbial biomass and microbial quotient | |

| 4-Badagliacca et al. 2022 [45] | NT vs. CT | ↓ release of labile C ⟹ ↑ carbon storing | ↓ release of labile N ⟹ ↓ N2O emissions | depending on soil texture | |

| 13-Rosinger and Bonkowski 2021 [52] | Crop rotation and freeze–thaw events | Soil freeze–thaw ⟹ ↑ dissolved organic C | Soil freeze–thaw ⟹ ↑ total dissolved N⟹ ↑ N2O emissions | Soil freeze–thaw ⟹ ↓↓ MBC and ↓ MBN; ↑ SOC ⟹ ↑ MBC and MBN losses | |

| 14-Rosinger et al. 2022 [53] | Crop rotation and freeze–thaw events | ↑ microbial cell lysis ⟹ ↑ dissolved organic C | ↑ N losses | Soil freeze–thaw ⟹ ↓ MBC; ↑ SOC ⟹ ↓ MBC | |

| Cover crops and litter | 6-Drost et al. 2020 [47] | Different cover crops | ↓ CO2 emissions | ↓ N2O emissions | ↑ fungal biomass |

| 7-Johansen et al. 2013 [41] | Fresh grass-clover vs. water and digested residues | ↑ CO2 emissions | ↑ N2O emissions | ↑ microbial activity (soil PFLA) | |

| 15-Rummel et al. 2020 [54] | Fresh maize root and shoot litter | ↑ C availability ⟹ ↓ bacterial community diversity | ↑ N2O emissions; ↑ N availability ⟹ ↓ bacterial community diversity | ↑ microbial respiration | |

| 8-Lori et al. 2020 [48] | Ecological intensive vs. conventional intensive | N.A. | Ecological intensive management ⟹ ↑ forage N uptake ↑ NO3− leaching; Soil OM ⟹ ↑ forage N uptake ↓ NO3− leaching | Ecological intensive management ⟹ beneficial N-related microbial community composition | |

| Plant diversity | 10-Niklaus et al. 2016 [50] | Plant species richness + NPK fertilization | N.A. | ↓ N2O emissions by plant species richness (unless fertilization is applied) | Plant species richness ↑ nitrifying enzyme activity; ↔ microbial gene abundance |

| 11-Panico et al. 2020 [51] | Plant species richness, soil tillage and mineral fertilization | ↑ Ctot, soil respiration and qCO2 in root-influenced soils more than in bulk soils | ↑ N2O emissions with plant growth stage | ↓ microbial diversity in root-influenced soils | |

| 12-Ribas et al. 2015 [43] | Plant species diversity vs. monocolture | ↑ CO2 emissions | ↓ N2O emissions | ↑ microbial amount and functionality |

Even if they are not part of the soil microbiome, the observation on biodiversity increase in soil earthworms has been reported since they are known to profoundly shape the soil microbiome. “↑” indicates an increase; “↓” indicates a decrease; “↔” indicates little or no effect; “⟹” denotes therefore.

3.3. Results Classified by Agricultural and Fertilization Practices

The inclusion of other studies beyond the initial focus on OM input, based on the literature keyword search described in the Materials and Methods (Section 2), provided additional insights into soil microorganisms and trade-offs in European agricultural soils. Among the 16 studies, different OM inputs and some agricultural management practices were encountered [Table 3]. Hence, results are further categorized according to the experimented agricultural and fertilization practices, including the application of agricultural wastes (e.g., fruit peels, hay residues), digestate and biochar, slurry (including cattle and anaerobic digested slurry), tillage system, crop rotation, cover crops, and litter [Table 4]. Additionally, in three articles, the contribution of plant diversity in regulating nutrient cycles was assessed [43,50,51], highlighting a complex relationship with soil carbon storage and GHG emissions.

3.3.1. Agricultural Organic Wastes

Agricultural organic wastes (AOWs) are outputs from agricultural activities, primarily consisting of crop residues and livestock waste. In particular, crop residues should be viewed as a valuable resource. They serve as a nutrient source for beneficial fungi, bacteria, and insects, help reduce evaporation from the soil surface, and contribute to maintaining soil moisture. Anastopoulos et al. [44] applied agricultural wastes in soil, specifically orange, mandarin and banana peels, and compared them with soils fertilized with the same amount of N in the form of ammonium nitrate. The authors found that agricultural wastes enhanced CO2 accumulation and enriched the soil with several bacterial groups, particularly Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, both of which are known to have a copiotrophic lifestyle under nutrient conditions [57]. These taxa also include numerous species of denitrifiers. Moreover, higher N2O emissions were recorded in soils treated with ammonium nitrate compared to those amended with agricultural wastes, where a substantial reduction in the relative abundance of soil bacterial taxa associated with N2O emissions was detected. Interestingly, no association emerged between soil N2O emissions and the composition of bacterial denitrifiers.

The addition of hay residues enhanced soil fauna diversity, and higher species richness and functional dissimilarity led to increased CO2 emissions (up to 10%) and suppressed N2O emissions from soil (up to 60%) [49]. The authors concluded that CO2 represents the end product of microbial-mediated processes such as soil respiration and decomposition. In contrast, N2O comes from intermediate products or by-products of microbial processes involved in N transformation, meaning that N2O can be consumed again and converted back into elemental N2 instead of being released as N2O emissions. This study also highlighted the major role of earthworms in driving both CO2 and N2O emissions.

3.3.2. Biochar, Digestate and Slurry

Biochar, digestate, and slurry are organic materials derived from agricultural and waste processing. Biochar is produced by pyrolyzing organic matter, digestate is the by-product of anaerobic digestion, and slurry is a water-based mixture of organic waste, often used as fertilizers or soil amendments. Dicke et al. [46] determined that biochar-treated soil samples produced significantly lower N2O emissions with respect to digestate-treated soil samples and controls. However, despite different tested conditions, the abundance of the nosZ gene was not affected, in contrast with other studies. Interestingly, the authors detected that the nosZ gene copy number was significantly higher in October 2012 than in June 2013, showing a major influence of temperature and the crop growing season.

Digestate is generally characterized by valuable nutrient (N, P, K) content and low OM [58]. As expected, the chemical composition and the nutrient availability in soils treated with digestate are subjected to changes due to the anaerobic digestion process. In an on-farm field trial lasting 3 years, Bachmann et al. [42] found that CO2 efflux from the soil surface and N uptake by maize were not significantly affected by the application of anaerobic digestion slurry residues. However, in digestate-amended soil, they observed a 50% reduction in the activity of soil microorganisms (dehydrogenase, acid- and alkaline-phosphatase) and a decrease in C turnover.

Johansen et al. [41] compared various amendments, including raw cattle slurry, anaerobically digested cattle slurry/maize, anaerobically digested cattle slurry/grass-clover, and fresh grass-clover, all applied to soil undergoing organic rotation. They observed only slight changes in microbial community composition with slurry-based amendments, while N2O emissions were lower compared to those from fresh grass-clover. Additionally, they found that anaerobically digested cattle slurry resulted in 30–40% more NO3- than raw cattle slurry.

Studying the effects of plant diversity on yield and CO2 and N2O emissions (also discussed in the Plant diversity subsection), Ribas et al. [43] tested three different fertilization levels using filtered pig slurry. They found that increasing the slurry application reduced soil ammonium content, but no significant changes in emissions were observed, suggesting that this outcome was likely due to their specific fertilization technique.

In addition, in a 15N-tracing study conducted in C- and N-rich montane grassland soil, Zistl-Schlingmann et al. [55] investigated the N balance following the addition of cattle slurry under two different management conditions, namely extensive and intensive, while also comparing climate-controlled conditions vs. +2 °C heating and reduced precipitation conditions. Both management practices led to high plant biomass, with N uptake by plants primarily derived from soil organic matter mineralization due to high microbial immobilization. Differently, fertilizer N was only lightly exploited by plants, determining significant gaseous N losses, particularly under climate change conditions. The study further revealed that more intensive management practices caused higher N mining, depleting organic N stocks in soil and resulting in lower biomass production and SOC stocks. Ultimately, the intensive application of cattle slurry as fertilizer was linked to higher N2O emissions and to SOC weakening.

3.3.3. Conservation System and Crop Rotation

No-tillage (NT) is widely reported as the most effective conservation system for improving soil organic matter due to no soil disturbance. This characteristic of no-tillage is extremely beneficial because surface residues and soil organic matter are left undisturbed, slowing decomposition and maximizing soil organic matter gains. Moreover, NT improves moisture retention by reducing evaporation and enhancing water infiltration, making more water available for crop production [59]. In semi-arid Mediterranean regions, where soils are particularly prone to OM depletion, Badagliacca et al. [29] found that long-term NT increased SOC, providing a greater availability of organic substrates, and consequently enhancing microbial biomass and microbial quotient, thus ameliorating soil quality. Interestingly, the increase in microbial biomass carbon (MBC) in NT vs. conventional tillage (CT) was mainly attributed to bacterial communities rather than fungi; a result that contrasts with several other studies that reported a greater fungal presence in NT systems. Notwithstanding, in a previous study conducted in the same field location in Sicily (Italy) by the same Italian research team [60], an almost 50% increase in total N2O emissions, together with enhanced activity of denitrifying enzymes, was observed during the faba bean growing season (crop rotation) in NT compared to CT. In a later study conducted in semi-arid Mediterranean regions, Badagliacca et al. [45] investigated the effects of NT on wheat performance, revealing an initial reduction in grain yield, along with changes in soil nutrient levels, microbial communities, and enzyme dynamics, which were likely due to the reduced availability of crop residues and slower decomposition. Overall, their findings suggested that NT application could lead to a decreased release of labile N and C forms into the soil, due to the lower crop residue mineralization, which in turn may affect wheat yield and soil microbial community.

In the postmining agricultural sequence analysed in [52,53], where fields typically underwent wheat and barley crop rotation, high-carbon soils were found to be more vulnerable to microbial losses compared to low-carbon soil. In other words, SOC content was associated with less microbial variation, primarily affecting MBC and basal respiration.

3.3.4. Cover Crops and Litter

In farming management, cover crops are plants grown primarily to protect and improve soil health, reduce erosion, and enhance soil fertility during the off-season between main crop cycles. Among the analysed manuscripts, Drost, et al. [47] explored the ability of different cover crops, both monocultures and mixtures proceeding from diverse species, to stimulate soil microbial functional diversity by providing a variety of OM inputs and to mitigate GHG emissions. They observed a similar increase in fungal biomass across all cover crop treatments tested. The metabolic potential of the microbial community, as assessed by Biolog ECO plates, was higher in cover crop treatments formed by multiple species, supporting the hypothesis that plant species richness promotes greater microbial diversity. Concerning the GHG emissions, they found an immediate reduction in both CO2 and N2O emissions from the first day of soil collection after the cover crop addition, regardless of the cover crop species applied.

In the above-mentioned [41], the soil application of grass-clover provided a higher amount of readily degradable organic C with respect to raw or digested cattle slurry, leading to an increase in microbial biomass. However, this also resulted in an undesirable increase of up to 10 times in CO2 and N2O emissions compared to all other examined treatments.

Several studies have proved that plant residues can increase N2O emissions upon incorporation into soils [61]. The term “litter” refers to the layer of decomposing plant and animal material that accumulates on the soil surface. The chemical composition of soil litter plays a critical role in C decomposition and availability for biological processes of nitrogen transformation. In [54], a comparison of GHG emissions from fresh maize root and shoot litter revealed that shoot litter significantly increased both CO2 and N2O emissions compared to root litter. Additionally, they observed a significant correlation between total CO2 and N2O emissions and the soil bacterial community composition, with reduced bacterial diversity in the presence of higher N levels and higher available C. Remarkably, the changes observed in bacterial community structure reflected the degradability of the analysed maize litter types. A lower diversity due to higher C and N availability favoured the presence of fast-growing C-cycling and N-reducing bacteria, such as Actinobacteria, Chloroflexi, Firmicutes, and Proteobacteria.

In a comprehensive analysis on selected Terrestrial Model Ecosystems (TMEs) used in agricultural systems, the abundance, diversity and activity of N-related microbes, as well as abiotic N-related soil indicators (such as NH4+, NO3−f, NO2 and dissolved organic N) were not significantly affected by the management strategy. However, the strategy did influence the N-related microbial community composition in connection with the N-cycling processes of forage-N uptake and NO3− leaching [48]. Furthermore, soil OM positively influenced N leaching by decreasing NO3− leaching, enhancing microbial communities and at the same time increasing forage-N uptake.

3.3.5. Plant Diversity

At least three of the analysed manuscripts dealt with plant diversity as a driver of changes in soil microbial structure and composition, subsequently affecting soil C content and or non-CO2 GHG emissions. Valuable insights into the relationships between the soil microbiome and N2O and CH4 fluxes were provided in Niklaus et al. [50]. Although the authors focused on how plant diversity—specifically grass species richness—affects these emissions, they also carefully examined and linked the abundance of bacterial nitrifiers and denitrifiers to these fluxes. Soil N2O emissions decreased with species richness in the absence of mineral fertilization but increased when fertilizer was added, which turned out to be directly proportional to the fraction of legumes in plant communities. Concerning methane, plant diversity was inversely related to soil CH4 uptake, regardless of fertilization. Moreover, plant diversity exhibited significant effects on soil microbial processes and the abundance of microbial groups involved in these processes.

The effects of plant diversity on yield and GHG exchanges in a forage mixture, measuring N2O, CH4, NH3 and CO2 fluxes in comparison with yield and soil inorganic N, were explored in [43]. In addition to yield, they observed a significant modulation of soil NO3− and NH4+, with plant diversity reducing N2O emissions. The authors highlighted that nitric and ammonium nitrates could impact soil microbial communities both directly and indirectly, although they made these associations without directly measuring microbial populations. Consistent with the findings in [50], legumes were responsible for the highest emission rates for all GHGs.

Lastly, Panico et al. [51] investigated the effects of two different plant species (sorghum and sunflower) on soil and its microbial communities, measuring the induced changes in soil physical–chemical characteristics and microbiota composition and functionality. Soil mineral fertilization was found to influence N-cycling processes based on soil N content and N2O emissions. In this context, bacterial communities were more affected than fungal communities.

The average effects on C sequestration, N2O emissions and soil microorganisms resulting from the different types of agricultural management practices or OM inputs discussed in the 16 analysed articles are tentatively summarized in Table 4. Agricultural organic wastes led to an increase in soil CO2 emissions, thereby reducing the soil’s carbon sequestration potential, but also had a positive effect on N2O emissions, which were associated with a significant increase in soil microbial diversity and/or microbial biomass. The effects and trade-offs driven by biochar, digestate and slurry resulted in much more complex and varied outcomes across the analysed studies. Additionally, tillage system, crop rotation, cover crops and litter had differentiated effects on C sequestration and N2O emissions, although most of the analysed studies indicated a shared gain in soil microorganisms. Finally, with a few exceptions, plant diversity was generally associated with increased soil CO2 and N2O emissions, with varied response at the soil microbial level [Table 4].

4. Discussion

Since the strong anthropogenic impact on biogeochemical cycles at the global level has been ascertained, current research focuses on developing and implementing strategies to manage nutrient cycling and, consequently, balance GHG emissions. In agricultural soils, C and N cycles are intricately linked, with efforts to enhance soil C sequestration having a direct impact on the balance of GHG gases, particularly N2O, as well as CH4 emissions and N leaching. The aim of this study was to identify the effects of the application of OM inputs and other management practices on soil microbes in relation to C sequestration and non-CO2 GHG emissions in EU agricultural soil, through an analysis of scientific literature. Based on the preliminary article search from the main data sources, it became apparent that integrated data on soil microorganisms and trade-offs were somewhat limited. Moreover, the studies varied considerably, with only a small amount of data available from several independent studies, making it challenging to conduct a robust statistical analysis.

Among the parameters used to assess soil microbial status and composition, microbial biomass (MB) and activity are often considered as potential indicators of soil quality and functionality as an ecosystem service provider. Indeed, both MB and microbial activity are strictly related to the soil’s living component and are highly responsive to management practices that alter the soil microbiota [62,63]. Indeed, Badagliacca et al. [29] demonstrated that soil MB and the main microbial groups showed varied or no significant responses to the different tillage systems, highlighting the diverse outcomes observed in different studies. Hence, the response of soil microorganisms is likely to be site-specific, depending on the context in which tillage systems are adopted, based on climate, soil type, fertility, and other management practices.

Soil microorganisms play a crucial role in regulating N2O emissions in agricultural systems. An updated description of the key bacterial taxonomic groups involved in various biochemical reactions of the N cycle is provided in [64], highlighting the potential of N2O reductase (nosZ) as a target for N2O mitigation, enabling soils to act as a N2O sink. A general positive effect on N2O emission reduction has been ascertained in most of the analysed articles, with a few exceptions, such as [41], which reported a huge increase in N2O emissions due to enhanced microbial activity following the application of grass-clover, in contrast with the well-known ability of clover to fix atmospheric N through symbiosis with Rhizobium bacteria in its root nodules [65]. These unexpected differences likely arise from the complexity of such studies, where a high number of both natural and artificial variables can influence the outcomes.

Based on the analysed manuscripts, only limited information could be extracted regarding the specific role of soil microbiome in modulating the trade-off between C se-questration and non-CO2 GHG emissions. Nevertheless, evidence from the more recent literature suggests that soil microbial communities promoting C sequestration while limit-ing GHG emissions are characterized by (i) a high abundance of CO2-fixing and C-accumulating taxa; (ii) a predominance of methane-oxidizing bacteria prevailing over methanogenic archaea; (iii) denitrifier communities enriched in nosZ, enabling the complete reduction of N2O and N2 [66]; (iv) high phylogenetic and functional diversity across C and N metabolic pathways; and (v) functional gene profiles favouring oxidation and assimilation over production of CH4 and N2O (e.g., higher pmoA relative to nirS/nirK gene abundances) [67,68,69].

It is worth noting that the literature search for the current systematic review was conducted in March 2023, during the execution of the EU ΣOMMIT project, and since then, several new studies and advancements have been made. Among the various OM inputs, integrating agricultural organic waste (AOW) into soil management practices can significantly influence C sequestration, N2O emissions, and soil microbial dynamics. A result of the articles analysed in this review is that organic amendments used to enhance soil OM stock and promote C sequestration can potentially offset GHG emissions [70]. Although N2O emissions were lower in the analysed papers [44,49], the impact of AOW on N2O emissions is variable, depending on factors such as C/N ratios and soil conditions. This is in line with some studies reporting increased emissions due to enhanced microbial activity [71]. At the same time, OM inputs can stimulate microbial diversity, including N2O-reducing bacteria that help mitigate emissions [64].

Biochar promotes C storage by stabilizing C in soils and may reduce N2O emissions by enhancing soil structure [72]. On the other hand, digestate and slurry contribute to C sequestration but can increase N2O emissions, especially under high N conditions, by altering microbial communities [37,73]. In a similar way, the results reported on the analysed articles show that biochar tends to mitigate N2O emissions, while slurry can enhance microbial activity but also elevate emissions.

More recently, outside the timeframe of this systematic review, numerous publications have reported on the effects of biochar on N2O emissions in relation to changes in microbial communities. This growing body of evidence, extending beyond the period covered by the reviewed papers, prompted the authors to undertake a deeper analysis of these newer studies with the support of Elicit AI (https://elicit.com/, accessed on 10 November 2025), an advanced research assistant for streamlining the analysis of scientific literature. A main output from the analysis of ten manuscripts [37,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82] is that biochar application to EU agricultural soils increases soil organic carbon by 30–150% and reduces N2O emissions by 13–54% through a combination of enhanced microbial functional gene expression favoring complete denitrification, increased microbial biomass, and physical entrapment of N2O in biochar pores, with effectiveness dependent on application rates above 20 t/ha and pyrolysis temperatures exceeding 500 °C. The global meta-analysis [78] revealed that biochar increased amoA gene abundance by 39.4% and nosZ genes by 41.7% while reducing nirS gene abundance by 17.8%. This pattern suggests enhanced nitrification capacity alongside increased potential for complete reduction of N2O to N2. Furthermore, biochar significantly alters bacterial community composition across European sites: for example, Italian sites demonstrated enrichment of Protobacteria and Gemmatimonadetes. The complete report of this analysis is annexed to this manuscript as Supplementary Material S5.

Among the management practices, conservation agriculture may have beneficial effects on both soil C sequestration and N2O emissions, even though NT is typically linked to lower crop yields. Interestingly, in Badagliacca et al. [45] it was found that NT reduces the release of labile C (i.e., C readily available for microbial activity), which in turn slows microbial decomposition rates. This process encourages the accumulation of OM in the soil, potentially enhancing long-term C sequestration. Additionally, the reduced availability of easily decomposable C may limit soil respiration, further supporting carbon storage over time. The same study also found that NT was associated with a decrease in labile N, which may decrease microbial activity, including the processes that contribute to N2O production (such as nitrification and denitrification). Since labile N is a key substrate for these processes, its reduction could result in lower N2O emissions. However, if N availability becomes too limited, it could hinder crop growth [83,84], potentially leading to a trade-off between reduced emissions and overall productivity.

In a study summarizing 57 publications, it was found that in plots with cover crops, over the long term, there was a 9% increase in organic matter, a 41% increase in microbial biomass in the soil, and about 50% less N leaching [85]. According to [86], cover crops, compared to monocropping enhance soil biodiversity and nutrient cycling, prevent runoff and N leaching, and improve soil physical properties and C sequestration over the long term. In a meta-analysis, it was concluded that although the effects of cover crop species and residue management on microbial properties vary across different soil and climatic conditions, cover crops overall can enhance biological soil health by enhancing microbial community abundance compared to soils without cover crops [87]. In another meta-analysis, it was found that cover crops generally enhanced soil microbial abundance, activity, and, to a lesser extent, diversity [88].

Plants release a variety of compounds through their roots into the soil, known as root exudates. These compounds, which include sugars, organic acids, amino acids, and secondary metabolites, serve as food sources for soil microbes. The type and amount of exudates vary depending on the plant species present in the ecosystem. Greater plant diversity typically results in a wider range of root exudates, thereby supporting a more diverse microbial community and beneficial microbial functions such as decomposition, nutrient cycling, and organic matter stabilization [89]. Concerning N2O emissions, plant diversity influences N cycling by modifying the availability of labile nitrogen in the soil, which is crucial for understanding how plant diversity can both increase and decrease N2O emissions, depending on the balance of microbial processes in the soil [90].

Importantly, the findings of this review are consistent with a recent meta-analysis on SOC [91], assessing that, especially in the complex agricultural setup, only a limited number of high-quality meta-analyses were available in scientific literature, leading to uncertain conclusions and potentially unreliable recommendations for scientists, policymakers, and farmers. Notwithstanding, even though the current review provides evidence that our knowledge is still limited, insightful considerations may be drawn related to the effects driven by the application of OM inputs to agricultural soils or by implementing management practices like conservation agriculture, crop rotation, and others on soil microorganisms, C sequestration and N2O emissions.

5. Limitations

While this study provides useful insights into the trade-offs between soil microbes and the interplay of carbon sequestration and non-CO2 greenhouse gas emissions in EU agricultural soils, some main limitations are recognized. First, the sample size of included studies is relatively small, consisting of only 16 scientific peer-reviewed manuscripts, selected following the PRISMA procedure. This limited sample size reflects several technical factors mentioned throughout the manuscript, particularly the complexity and number of required keywords to capture three outcome terms. We selected Scopus as the sole database because it allows flexible keyword combinations, whereas other databases present more restrictions and a more difficult keyword handling; however, most Society journals are not indexed in Scopus. Future studies could benefit from refining or reframing complex, multi-output research questions into testable hypotheses to increase the significance of the results.

Second, the selected studies are predominantly from a few EU countries, such as Germany and Italy, resulting in limited geographical and pedoclimatic representation across European agricultural soils. Therefore, the results should be interpreted within the context of the available evidence. There is a clear need for future studies in underrepresented European regions to improve spatial coverage and validate observed trends across diverse pedoclimatic conditions. Extending this research to a global scale would further enhance the generalizability of the findings and provide a more mechanistic understanding of the relationships among soil microbial communities, carbon sequestration, and non-CO2 GHG emissions.

6. Conclusions

The data from the 16 scientific articles reviewed in this study are valuable; however, the lack of robust long-term studies conducted across diverse EU regions and pedoclimatic conditions remains a significant gap. Further research is needed to better understand the effects of different management practices—such as soil conservation and OM-based fertilization—on soil microbial diversity, carbon sequestration, and N2O and other GHG emissions.

Given the complexity of these studies, with numerous parameters involved and different outputs to analyse, the low level of standardization in relation to the field experiment, methodology used and data measured should be addressed to allow comparisons among different climate/regional locations. The EU Mission ‘A Soil Deal for Europe’ (Mission Soil), under the EU Horizon Europe Program, has the goal to create 100 Living Labs (LLs) and Lighthouses by 2030 to promote sustainable land and soil management in urban and rural areas (https://mission-soil-platform.ec.europa.eu/about/mission-soil, accessed on 10 November 2025). Through these LLs, Mission Soil can play a pivotal role in demonstrating the potential of EU-funded soil microbiome research to enhance biodiversity and support in situ measurements of GHG fluxes and carbon sequestration. At this aim, the use of soil indicators—chemical, physical and biological—and the establishment of general experimental principles and protocols, starting from the field design up to the soil sample collection, soil microbiome analysis (16S rRNA sequencing) and GHG emissions measurement, could help to make the comparisons and assessments of variations in soil microbiota and the trade-offs between carbon sequestration and non-CO2 GHG emissions less complex.

Most of the selected studies addressed one or more management practices, including tillage systems, crop rotations, and the addition of litter, digestate, organic waste, or biochar. The application of OM inputs was generally found to have positive effects on microbial biomass (MB), influencing the functional diversity dynamics of soil microorganisms. At the same time, a general increase in soil organic carbon (SOC) content and potential reductions in GHG emissions were observed. Overall, despite a few contrasting results, the main findings advocate for soil biodiversity conservation to promote carbon sequestration and mitigate N2O emissions and encourage sustainable agricultural practices. Another relevant factor frequently considered in these studies, in addition to the feedstock origin of the OM, is the cultivated plant species. Plant richness and diversity appear to reduce soil N2O emissions and drive C sequestration by shaping the activity and composition of soil microorganisms, which play a pivotal role in N cycling and C storage.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010319/s1, Supplementary Material S1: PRISMA 2020 Checklist; Supplementary Material S2: Co-occurrence analysis of keywords with centrality metrics (Betweenness, Closeness, and PageRank) to identify clusters and relationships within microbial and soil science concepts; Supplementary Material S2: Thematic map of co-occurrence analysis with centrality metrics (Betweenness, Closeness, and PageRank) to identify basic, emerging, and niche themes; Supplementary Material S3: List of the 16 finally selected original articles from Scopus picked out in this systematic review; Supplementary Material S4: Report generated by Elicit AI on the effects of biochar inputs on soil microorganisms in relation to C sequestration and N2O emissions in EU agricultural soil.

Author Contributions

All authors discussed the results and contributed to the final manuscript. A.L. (Arianna Latini): conceived and developed the theoretical framework, collected the data, performed the analysis, wrote the original draft, reviewed, and edited the paper. L.D.G.: collected the data, performed the analysis, reviewed and edited the paper. M.C.: collected the data, performed the analysis and reviewed the paper. E.V.: reviewed and edited the paper, contributed to the implementation of the research. A.L. (Alessandra Lagomarsino): performed data curation, reviewed and edited the paper, funding acquisitions. M.S., P.M., F.V. and S.M.: contributed to the interpretation of the results and reviewed the paper. A.B.: conceptualization, data validation, reviewed and edited the paper, supervision, funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under grant agreement No. 862695 (European Joint Programme SOIL) “Towards climate-smart sustainable management of agricultural soils”. The research was developed in the framework of the EJP SOIL internal project ΣOMMIT—SUstainable Management of soil Organic Matter to MItigate Trade-offs between C sequestration and nitrous oxide, methane and nitrate losses” (https://projects.au.dk/ejpsoil/soil-research/ommit, last accessed on 15 December 2025). This manuscript reflects only the authors’ views and opinions; neither the European Union nor the European Commission can be considered responsible for them. The authors also gratefully acknowledge funding from the Italian project “SoilHUB2—Creazione di una rete italiana di competenze per la gestione sostenibile del suolo.” (D.M. MASAF—DSR 4—Prot. N° 0672924 del 20 December 2024); the European Union ECO-READY project “Achieving Ecological Resilient Dynamism for the European food system through consumer-driven policies” (GA No. 101084201) under the HORIZON-CL6-2022 Research and Innovation Programme; the European Union DELISOIL project “Delivering safe, sustainable, tailored & societally accepted soil improvers from circular food production for boosting soil health” (GA No. 101112855) under the Horizon Europe Programme; and the “Strengthening the MIRRI Italian Research Infrastructure for Sustainable Bioscience and Bioeconomy” SUS-MIRRI.IT project funded by the European Union—NextGeneration EU, PNRR—Mission 4 “Education and Research” Component 2: from research to business, Investment 3.1: Fund for the realization of an integrated system of research and innovation infrastructures—IR0000005 (D.M. Prot. n.120 del 21/06/2022).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

All information required to access the manuscripts analysed in this review has been provided. The data supporting the findings are reported in the Supplementary Material S3 and the References section.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the entire team of the EJP SOIL internal project ΣOMMIT (https://projects.au.dk/ejpsoil/soil-research/ommit, last accessed on 15 December 2025) for insightful discussions and valuable suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| amoA | Ammonia Monooxygenase gene |

| AOB | Ammonia-Oxidizing Bacteria |

| AOW | Agricultural Organic Waste |

| BI | Biodiversity Index |

| BR | Basal Respiration |

| C | Carbon |

| CH4 | Methane |

| CO2 | Carbon dioxide |

| CT | Conventional Tillage |

| DM | Dry Matter |

| GHG | Greenhouse Gas |

| LOC | Labile Organic Carbon |

| MBC | Microbial Biomass Carbon |

| MBN | Microbial Biomass Nitrogen |

| N | Nitrogen |

| N2O | Nitrous Oxide |

| nirK and nirS | Nitrite Reductase genes (commonly used as functional marker of denitrifying bacteria) |

| nosZ I and nosZ II | Nitrous Oxide Reductase genes of clade I and II, respectively |

| NT | No Tillage |

| OM | Organic Matter |

| PLFAs | Phospholipid Fatty Acids |

| pmoA | Particulate Methane Monooxygenase gene |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| qCO2 | Soil microbial quotient |

| SOC | Soil Organic carbon |

| TME | Terrestrial Model Ecosystem |

| TOC | Total Organic Carbon |

References

- Kannojia, P.; Sharma, P.K.; Sharma, K. Chapter 3—Climate Change and Soil Dynamics: Effects on Soil Microbes and Fertility of Soil. In Climate Change and Agricultural Ecosystems; Choudhary, K.K., Kumar, A., Singh, A.K., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2019; pp. 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suman, J.; Rakshit, A.; Ogireddy, S.D.; Singh, S.; Gupta, C.; Chandrakala, J. Microbiome as a key player in sustainable agriculture and human health. Front. Soil Sci. 2022, 2, 821589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chai, Q.; Dou, X.; Zhao, C.; Yin, W.; Li, H.; Wei, J. Soil microorganisms in agricultural fields and agronomic regulation pathways. Agronomy 2024, 14, 669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paustian, K.; Lehmann, J.; Ogle, S.; Reay, D.; Robertson, G.P.; Smith, P. Climate-smart soils. Nature 2016, 532, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ontl, T.A.; Schulte, L.A. Soil Carbon Storage. Nat. Educ. Knowl. 2012, 3, 35. Available online: https://www.nature.com/scitable/knowledge/library/soil-carbon-storage-84223790/ (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Lal, R.; Negassa, W.; Lorenz, K. Carbon sequestration in soil. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2015, 15, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharyya, S.S.; Ros, G.H.; Furtak, K.; Iqbal, H.M.; Parra-Saldívar, R. Soil carbon sequestration—An interplay between soil microbial community and soil organic matter dynamics. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 815, 152928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Cui, H.; Fu, C.; Li, R.; Qi, F.; Liu, Z.; Yang, G.; Xiao, K.; Qiao, M. Unveiling the crucial role of soil microorganisms in carbon cycling: A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 909, 168627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Tong, D.; Nie, X.; Xiao, H.; Jiao, P.; Jiang, J.; Li, Q.; Liao, W. New insight into soil carbon fixation rate: The intensive co-occurrence network of autotrophic bacteria increases the carbon fixation rate in depositional sites. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2021, 320, 107579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2007; Available online: https://archive.ipcc.ch/publications_and_data/ar4/wg1/en/ch2s2-10-2.html (accessed on 15 December 2025).

- Bahram, M.; Espenberg, M.; Pärn, J.; Lehtovirta-Morley, L.; Anslan, S.; Kasak, K.; Kõljalg, U.; Liira, J.; Maddison, M.; Moora, M.; et al. Structure and function of the soil microbiome underlying N2O emissions from global wetlands. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraseni, T.N.; Qu, J. An international comparison of agricultural nitrous oxide emissions. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 135, 1256–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebender, U.; Senbayram, M.; Lammel, J.; Kuhlmann, H. Effect of mineral nitrogen fertilizer forms on N2O emissions from arable soils in winter wheat production. J. Plant Nutr. Soil Sci. 2014, 177, 722–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Chadwick, D.R.; Cheng, Y.; Yan, X. Global analysis of agricultural soil denitrification in response to fertilizer nitrogen. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616–617, 908–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]