Abstract

Promoting demand-responsive transit (DRT) is crucial for developing sustainable and green transportation systems in urban areas, especially in light of decreasing transit ridership and increasingly varying demand. However, the effectiveness of such services hinges on their ability to efficiently match varying travel demand. This paper presents a data-driven framework for the joint optimization of customized bus routes and timetables, to enhance both service quality and operational sustainability. Our approach leverages large-scale taxi trip data to identify latent travel demand, applying a spatial–temporal clustering method to group trip requests and identify DRT stops by trip origin, destination, and direction. An adaptive large neighborhood search (ALNS) algorithm is improved to co-optimize passenger waiting times and bus operation costs, where an unbalanced penalty for early or late schedule deviations is developed to better reflect passengers’ discomfort. The framework’s performance is validated through a real-world case study, demonstrating its ability to generate efficient routes and schedules. The model manages to improve passenger experience and reduce operation costs. By creating a more appealing and efficient service, this model contributes directly to the goals of green transport in terms of reducing the total vehicle kilometers that are traveled, and demonstrating a viable, high-quality alternative to private car usage. This study offers a practical and robust tool for transit planners to design a next-generation DRT system that is both economically viable and environmentally sustainable.

1. Introduction

Demand-responsive transit (DRT) provides critical complementation to regular buses with flexible route designs, operation timetables, and economic fares. DRT has been increasingly emphasized in order to enhance service quality, expand coverage, and improve the sustainability performance of public transport systems [1,2]. With flexible routing and scheduling, DRT can offer shorter waiting times, more direct connections, and improved accessibility for passengers whose travel needs may not be covered by conventional fixed-route services. As urban travel behavior becomes more dynamic with regard to both time and space, the adaptability of DRT makes it an important component of modern sustainable mobility strategies.

Numerous empirical studies document that bus demand is highly variable across space and time, and fixed-route buses often operate with substantial spare capacity [3]. Benchmark guidelines for urban bus systems similarly report load factors of 30–40% for large buses, and about 65% on very busy routes [4]. Detailed analyses of load factor non-equilibrium further show that full-load rates can be highly unbalanced across directions, time periods, and segments within the same network [5]. Trip mode shifts, from ride-hailing, taxis, or self-driving to DRT, contribute to reducing vehicle travel distance and per capita emissions [1,6].

Recent evidence indicates a rapidly growing interest in DRT deployment. Market analyses report strong expansion of the global DRT sector in recent years, with expectations of further growth driven by digital platforms, real-time information, and new mobility services [7]. Case studies from Europe, North America, and Asia show that well-designed DRT schemes can significantly increase ridership compared with the fixed routes they replace, and in some pilot projects ridership has been reported to increase by more than a factor of two after DRT introduction [8]. These mixed outcomes underscore the need for more advanced, data-driven tools to enhance DRT services’ attractiveness and operational efficiency.

In the literature, DRT has attracted substantial attention. Existing studies address topics such as flexible route design and zoning, fleet sizing, vehicle routing and scheduling, the real-time matching of vehicles and passengers, and short-term demand prediction [9]. Various meta-heuristics, including large neighborhood search and adaptive large neighborhood search (ALNS), have been developed to tackle the underlying NP-hard optimization problems. Multiple conflicting objectives are explored, such as minimizing waiting times and operating costs [10]. Together, these studies highlight both the potential and the complexity of integrating DRT into sustainable transport systems.

To our limited knowledge, several important methodological gaps remain, particularly when the goal is to design DRT services that are tightly aligned with temporal–spatial trip demand. First, passenger trip requests are often aggregated at coarse temporal or spatial resolutions (e.g., large zones or long-time intervals), which obscures underlying trip flow similarity and reduces the precision of demand representation. Second, although a growing body of research examines boarding and alighting patterns and infers time-varying OD matrices from stop-level counts in conventional transit systems, most DRT models still do not differentiate between boarding and alighting behaviors at stops, despite its importance for capturing passenger trip patterns, capacity constraints, and route feasibility [10,11]. Third, many operational DRT formulations continue to rely on linear or otherwise simplified penalty structures that cannot fully capture the asymmetric or threshold effects on passenger discomfort associated with early or late vehicle arrivals relative to desired departure times [10].

To address these gaps, this study proposes a comprehensive DRT design framework based on refined temporal–spatial analysis regarding traveler trip demand. Large-scale trip requests are clustered with origin, destination, and trip direction for trip flow similarity. Boarding and alighting behavior at DRT stops are explicitly distinguished. Key operation constraints are considered in the proposed model, such as route length and service frequency. On this basis, the ALNS solution method is developed to jointly minimize passenger waiting time and bus operation cost, with unbalanced penalties for bus arrivals ahead of or behind passengers’ expected departure times to better reflect schedule-related discomfort. A real-world case study follows, with large-scale taxi-order data to validate the proposed model and solution approach of their potential to improve passenger trip quality and reduce bus operation cost.

Our contributions are three-fold. First, we extend the existing demand analyses methods. Motivated by the simple temporal attribute of trip demand, we first cluster demand temporarily. Thus, trip demand with close departure time is separated into the same cluster. Subsequently, spatial clustering employs adaptive k-medoids to capture the demand flow features of origin, destination, and direction. This allows demand with distant origins and destinations to be included in the same clustering, if their trip direction is close enough. In this way, we may expect DRT to take up the demand in the same direction without much detouring. Furthermore, boarding and alighting from bus stops are identified with demand origins and destinations in sequence, where alighting from stops corresponds only to the demand covered by boarding stops.

Second, the model for DRT routes is revised with scheduling tuned afterwards. We propose the constraints on DRT routes, including vehicles pulling in and out at stops en-route, passenger load factor, and route length, etc. A delicate service objective is proposed to reflect the gap between vehicle arrival time and passengers’ expected departure time. We distinguish the service penalty with respect to gap extent. That is, a small gap ahead of or behind passengers’ expectation brings no penalty, while a large gap corresponds to rapidly increasing penalty. Service penalty and DRT operation cost, as well as passenger cost, are included in the fitness function for optimal route design with the adapted ALNS method. The DRT service timetable is iteratively updated for minimal passenger cost. Notably, temporary trip demand is not incorporated into the proposed DRT route to avoid adding to uncertainty to passengers’ trip times [12]. That may add to passengers’ trust in DRT services and promote ridership.

Third, city-wide taxi data is employed to validate the proposed method. Widespread demand throughout the day is fitted into limited temporal and spatial clustering. DRT routes are proposed with timetables to serve the concentrated trip demand, i.e., demand clustering of large counts of trips. The results show that the proposed solution manages to enhance DRT operation efficiency and service quality.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 summarizes the relevant literature review in the research. Section 3 establishes modeling for temporal–spatial clustering. Section 4 revises the ALNS algorithm to solve the model for DRT routes and timetables, followed by case study in Section 5. The conclusions are briefly drawn in Section 6.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Demand Analysis and Stop Layout

Passenger flow analysis is fundamental to DRT research. Demand analysis mainly involves mining and quantifying potential trips in specific regions or groups from multi-source data, such as bus IC card data [13,14], taxi trajectory data [15,16], and POI data [17]. That allows the precise prediction of potential passenger demand for all transfer directions of the last bus at target stations [18]. Weighted DBSCAN is employed to cluster OD data from non-bus travel modes such as shared bikes/taxis, to excavate the areas with concentrated potential demand for micro-circulation lines [19]. Passenger preferences in high-demand scenarios (e.g., commuting) can be identified for local commuter customized buses by integrating data of ride-hailing orders with small sample survey [20].

To extract intensive demand that is suitable to DRT service, streamline clustering-based methods have received increasing attention in recent years. An improved flow clustering method is proposed that considers both the origin and destination when calculating flow similarity, ensuring that clusters accurately represent flows between similar origins to destinations [21]. Multi-dimensional spatial statistics are used to compare the spatial differences between two OD datasets [22]. Artificial intelligence is increasingly applied to OD analysis, including deep learning [23], deep reinforcement learning [24], and explainable neural networks [25]. That extends our knowledge of the factors affecting transit OD distribution and changes.

Notably, a general metric of temporal–spatial similarity is difficult to obtain due to the inconsistency between time and space dimensions; thus, three strategies are commonly adopted. The first strategy judges whether demands are close in space and time, separately. For example, the K-nearest neighbor test is proposed as a significant breakthrough in the field of temporal–spatial interaction analysis [26]. The method avoids subjective threshold setting and the linear assumptions of previous studies. The second strategy explores comprehensive closeness both spatially and temporally. For example, spatiotemporal distance is defined by simply adding spatial distance and temporal distance [27]. That lacks a reasonable explanation and easily leads to weight determination problems. The third strategy involves analysis in a specific order (e.g., spatial clustering preceding temporal clustering). A time-segmented hierarchical clustering method is proposed to divide data into multiple time periods, to which hierarchical spatial clustering is performed [21]. Therefore, sequential spatial–temporal clustering shows better capacity to address the complex clustering of trip demand.

DRT station layout is critical to bridge passenger demand with route services. Based on regular bus IC card data and actual operating conditions, existing bus stops are prioritized for DRT to reduce infrastructure construction costs while shortening passengers’ walking distance [28]. Utilizing POI data, bus IC card data, and questionnaires, an affinity propagation clustering algorithm is proposed for bus stop locations used for micro-circulation in aging communities [29]. Stop spacing can be optimized with the objective of minimizing passenger travel time [30]. A multi-dimensional evaluation system is constructed to match trip demand and optimize bus stop locations with K-medoids clustering and an improved tabu search algorithm [31]. Note that boarding stops may be differentiated from alighting stops to secure demand coverage at both trip ends.

2.2. Roue Planning

2.2.1. Varying Objectives

Current research on bus route optimization primarily focuses on passenger costs, operator costs, and multi-objectives [32]. Passengers’ objectives mainly include improving comfort and convenience while reducing travel costs. For example, to maximize service quality by minimizing a weighted sum of customer walking time, waiting time, and riding time, their weighted sum is formulated for demand-responsive feeder services through a large neighborhood search algorithm [33]. A bi-level programming model is developed to optimize customized bus routes, where the upper level maximizes operational efficiency and the lower level minimizes traveler costs [34]. A customized bus route and stop planning method is proposed to minimize the passenger cost of buses’ late and early arrivals [35]. A novel framework is explored with embedded eco-routing technology into DRT to enhance bus flexibility and adaptability from passengers’ perspectives [36]. Note that we may emphasize the punctuality and rapid response of DRT services at current stage to enhance its attraction. Thus, we are motivated to delineate the punctuality of DRT services more accurately, instead of treating early and late DRT equally.

Operators’ objectives primarily focus on operating costs, fixed costs, fare revenues, and boarding rates. Operation revenue with dynamic interactive demand insertion is optimized for static DRT service networks [37]. A routing model is established for DRT with the comprehensive objectives of fixed costs, variable costs, and penalties for passengers who are not served [38]. A two-stage stochastic programming is formulated with a rolling horizon scheme to minimize the total vehicle travel time cost and penalties for rejected requests [16]. A multi-commodity network is constructed for flow-based customized bus service design model with the dual objectives of maximizing vehicle capacity utilization and minimizing operation costs [39]. A route selection model is developed that considers operation costs in relation to travel distance, fixed costs such as vehicle purchase, taxes and fees, maintenance/repair costs, depreciation, and driver wages [40].

Multi-objective optimization considers both passenger and operator costs. A spatial queue model is proposed to incorporate bus and DRT passenger travel costs and operation costs. It shows that combining bus services with DRT outperforms traditional transit and fixed-route feeder services [41]. A multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithm is adopted for system-level optimization. A bus route design model for short-turn services follows, with the objectives of minimizing excess capacity, capacity shortages, and passenger time costs [42]. They propose a multi-objective optimization framework and apply Pareto frontier analysis to balance operator and passenger interests. A heuristic algorithm is used to efficiently solve large-scale problems. A service area design is proposed with a zoning strategy, which is solved with the greedy algorithm. It minimizes operator and passenger costs, and a two-stage partitioning approach is developed to generate near-optimal solutions [43].

2.2.2. Route Modeling

The DRT route-optimization problem can be modeled and solved as a classical vehicle routing problem. It can be categorized as static, semi-flexible, flexible, or dynamic.

Static or semi-flexible DRT routes serve relatively stable trip demands. They typically operate within predefined route structures and time frames. Notably they also allow flexible adjustments according to passenger demand to enhance operational efficiency and reduce operating costs. Given passenger requests with specified origins, destinations, and desired time windows, it is shown that under low-to-medium-demand levels, a flexible route system tends to exhibit the lowest system cost [44]. A mixed-integer programming model is further proposed for the simultaneous optimization of bus routes and passenger assignment. In a case study in Beijing, this method improved vehicle utilization across multiple routes [45]. Based on the demand data collected two hours in advance, with the objectives of increasing the number of satisfied passenger requests and maximizing operator profit, a two-stage branch-and-price-and-cut algorithm is proposed [46]. An enumeration-based approach is employed to compare the costs of operating a semi-flexible system in low-demand areas [47]. It conducts detailed analyses of operating costs, energy consumption, maintenance expenses, and environmental impacts for different vehicle types (such as minivans, standard vans, and minibuses) for economic viability and feasibility.

Dynamic DRT routes are increasingly studied. They adjust routes and timetables in a real-time style in accordance with changing demand, even after operations have commenced. Extensive numerical experiments are conducted to evaluate the impact of dynamic requests on DRT performance [48]. A multi-depot dynamic vehicle routing framework is proposed that leverages ALNS to efficiently reconstruct feasible routes under evolving time-windows and request dynamics [49]. The action-refinement, multi-agent dueling double Deep Q-Network algorithm is proposed to tackle the challenge of simultaneous route optimization for both static and optional dynamic passenger demands under dynamic road conditions [50]. This also calls for the deployment of exclusive bus lanes to enhance service reliability without significantly affecting social car operations [51].

2.3. Research Gap and Contributions

With extensive research on demand analysis, station layout, and DRT routing, several critical gaps are identified. First, fine-grained trip flow similarities should be well addressed for the accuracy of demand representation. This is an issue that is becoming more pressing with increasingly dynamic urban mobility patterns. Second, DRT models should distinguish boarding and alighting behaviors for bus stop siting. Third, optimization models may adopt an asymmetric and non-linear penalty for schedule deviation that causes passenger discomfort. Finally, integrating high-resolution mobility datasets (e.g., taxi orders) into joint route–timetable optimization frameworks may lay a solid foundation for DRT demand analysis and its efficient operation.

To bridge these gaps, this study introduces a data-driven DRT design framework that aligns high-resolution temporal–spatial demand patterns with operational decision making. A direction-aware clustering method captures latent trip flows by jointly considering origins, destinations, and travel directions. An explicit treatment of boarding and alighting improves demand fidelity and operational efficiency where more trips can be covered with fewer stops. The ALNS algorithm is developed to co-optimize routes and timetables, incorporating an asymmetric schedule deviation penalty that reflects passenger tolerance more accurately and enhances perceived service quality. To secure DRT service quality, we target semi-static routes that do not respond to temporally added trip demand. A real-world case study based on large-scale taxi-order data demonstrates that the proposed framework can simultaneously reduce operation cost and improve service performance, offering actionable insights for efficient, attractive, and sustainable DRT services.

3. Modeling for Passenger Demand and DRT Stop Layout

This section establishes the method relating to demand clustering and stop locations for DRT services. Demand clustering first filters the trips within the active period and with appropriate length that are suitable to DRT services. Stop locations follow to first identify the boarding points for passengers getting on, and then the alighting stops for the demand whose origins are covered.

3.1. Demand Clustering with Temporal Partition and Spatial Difference

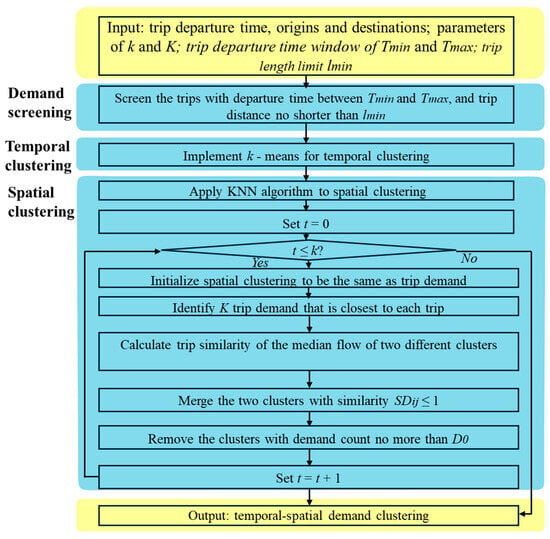

Demand characteristics can be analyzed in two aspects, i.e., temporally and spatially. Figure 1 shows the framework of demand analysis in time and space for DRT. Demand is first filtered via time and distance range to fit the service range of DRT. The time limit is given between and . Trip distance is set no smaller than the threshold value . In the following, the k-means method is adopted to divide the whole time of demand source data into k sets, and each is then brought to the KNN method for spatial clustering.

Figure 1.

Framework for demand clustering.

At the start, each trip demand is treated as a cluster, and the distance of the cluster’s middle point from all other demand is calculated. The nearest demand to the target demand is paired. When the flow of demand and belong to different spatial clusters and , the similarity of the two demands is calculated. If , we merge the two clusters of demand and into one, i.e., and is removed. We repeat the above steps until all the demand belonging to one temporal cluster is enumerated. Then we move on to the next temporal cluster and implement the spatial cluster steps. Thus, we obtain the results of temporal–spatial clustering.

The similarity of demand and is calculated with

Notation and is the similarity degree of the tlow origin and destination of demand and , respectively. They are given by

Notation and refers to the origin and destination distance between demand and , respectively, and refers to the importance of the origin and destination, respectively, means length coefficient, and means the length of flow . The similarity function allows the difference in the angle of demand direction to be no larger than arcsin(2). For example, if , the angle tolerance in the demand direction is 30°. We suggest the value of parameter to be no larger than 0.25 to require the angle difference among trip demand to be no more than 30°. The larger the value of , the more disperse the clustered demand.

It is true that including OD direction into the evaluation of OD similarity may cause the discontinuity of the routes. For example, when the DRT route length comes to the upper bound as the vehicle serves en-route destinations, the DRT route can be ended instead of expanding to serve the demand with further destination. Such problems have been considered in demand clustering to avoid inappropriate demand inserting that may pose difficulty or hinder DRT route scheme. Therefore, demand clustering does not necessarily pose a direct effect on DRT routes. That is, DRT route searches combine demand in the same clustering efficiently and economically, instead of forcing all clustering demand into one DRT route. Therefore, comprehensive demand clustering taking trip direction into consideration allows greater space for DRT route generation. This offers the potential for DRT routes to be more efficient in order to carry more passengers.

3.2. Stop Locations

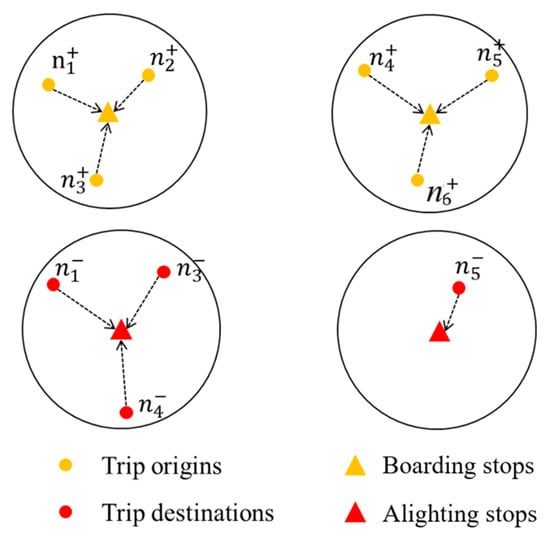

Stop locations are determined referring to the input of two parts: (1) clustered demand, and (2) existing bus stop locations. Figure 2 illustrates the procedure for selecting bus stops. Notation , represents the origin of passenger demand, which are intended to be served by boarding bus stops, while , represents the destinations of passenger demand to be served by alighting bus stops.

Figure 2.

Mapping trip origins and destinations to boarding and alighting bus stops.

Here, the locations of trip origins and destinations are treated in sequence instead of simultaneously. If trip origins and destinations are treated together, we may leave out more demand than expected within the specified stop coverage, and either the origins or destinations of which may not be covered. Thus, here we first explore the demand origins for boarding bus stop set , and then the demand destinations for alighting bus stop set for the demand whose origins are covered already by boarding stops. Subsequently, we combine the two sets and to remove the redundant stops and reduce the feasible space of DRT routing.

Algorithm 1 summarizes the method for establishing bus stops, which is applicable to both boarding and alighting bus stops and . Note that the algorithm is first adopted for boarding stop set with the origin information of the demand, and then for alighting stop set with the destination information for the covered bus demand obtained from establishing set . Here, the adaptive k-medoids method is adopted to increase bus stops one by one until the clustered trip demand is covered by no less than percentage, with bus stops spacing to avoid burdensome walk.

| Algorithm 1 Method for establishing bus stops | |

| Input: clustered demand that has been partitioned into temporary demand coverage rate and stop spacing for existing bus stops. | |

| Output: boarding and alighting bus stops. | |

| NO. | Procedure |

| 1 | Input passenger demand, bus stop service spacing , predetermined demand coverage rate , and existing bus stops as the stop candidate set. Set stop ID . |

| 2 | For each bus stop in candidate set, calculate the distance between the stop and all trip origins for distance matrix. Sum the distance for each candidate bus stop. Take the bus stop with the minimum distance into the selected stop set and remove it from the candidate stop set. Set . |

| 3 | Implement adaptive k-medoids algorithm for all the selected bus stops to cluster trip demand. For each stop clustering, calculate the sum of the distance between each covered demand to the other demand. Take the demand with the minimum as the newly selected bus stop. |

| 4 | Judge whether the selected bus stop set changes. If yes, go to step 3. Otherwise, go to step 5. |

| 5 | Calculate the coverage rate of the selected bus stops, and compare it with . If , go to step 2. Otherwise, go to step 6. |

| 6 | Return the selected bus stop set. |

4. DRT Route Model and ALNS Solution

4.1. Model for Bus Route Planning

The objective function with the DRT route scheme is given by

where means total trip cost, and and refer to passenger cost and operation cost, respectively. is composed of passenger in-vehicle time and a soft penalty cost for waiting time, and includes the fixed and variable operation cost. Notation means passenger in-vehicle cost, is the fixed cost of bus operation, is the variable operation cost, and are the set of boarding and alighting stops, is the set of vehicles, means the count of passengers with origin and destination , is the arrival time of vehicle to the stop serving origin , is the binary variable indicating whether vehicle serves the stops corresponding to origin , is penalty of the soft time window for vehicle serving the stops of origin means all the bus stops and stations, i.e., with representing terminal stations, is also a binary variable indicating whether vehicle runs from stops serving origin to destination , is from station and means the distance between stops for origin and destination .

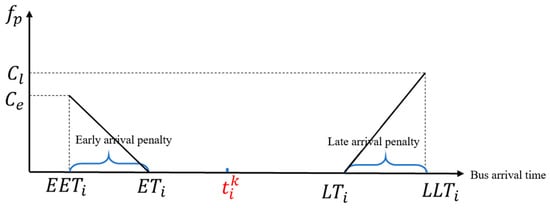

Variable is calculated by referring to the curve in Figure 3. That is, passengers may accept early DRT arrival in a small range, while late arrival can be tolerated in larger time window. Moreover, DRT arrival within a specified range should be accepted with almost no penalty due to the nature of DRT accommodating multiple trip pairs.

Figure 3.

Curve of waiting penalty for demand .

Variable is given by

where is penalty for bus early arrival, and are the range of expected departure time for demand , and are the limit of the tolerable departure time for demand . Parameter is set to be smaller than , which is consistent to the fact in the real world travelers are more sensitive to being late. The function extends the simplified function in the literature that assigns equal penalty to late and early arrivals [52].

The DRT route-planning model is constrained by the following relationships. Equations (8)–(10) mean that each trip demand can only be served once. Equation (11) requires that a bus must serve both the boarding and alighting stops once it accepts one demand. Equation (12) means that a bus must leave one stop if it pulls in at the stop. Equation (13) updates the load factor of the vehicle. Equations (14) and (15) require that the bus load factor must not exceed its load capacity. Equation (16) is about the time window. Equation (17) establishes the relationship between the bus arrival and departure time. Equation (18) exerts a limit on the bus route length. Equation (19) requires the bus to stop at the boarding stop before moving to the alighting stop.

Notation refers to the in-vehicle passenger count when vehicle arrives at the stop corresponding to trip demand , means the passenger getting onto or off vehicle at stop corresponding to demand means load capacity of vehicle is the arbitrarily large constant, and is the upper bound of the DRT route length.

4.2. Improved ALNS

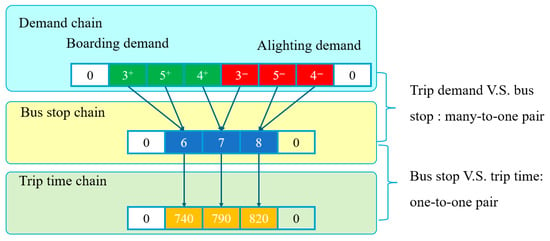

With the clustered demand and selected bus stops, bus routes are established, referring to the above constraints, including bus route length and loading capacity, to which ALNS is adopted. Three chains of passenger demand, bus stop, and vehicle time are incorporated into the model, corresponding to passenger boarding and alighting point, the sequence of stops served by buses, and bus arrival time. Figure 4 illustrates an example of the three chains. For the chain of passenger demand, passengers of demand three and five get on at stop 6 at time 7:24 (i.e., 7.4 h after midnight). Then passenger four gets on and passenger three gets off at stop 7 at time 7:54. In the following, passengers five and four get off at stop 8 at time 8:12.

Figure 4.

Chains of demand, bus stop, and trip time (Green for boarding demand, red for alighting demand, blue for bus stops, orange for bus time).

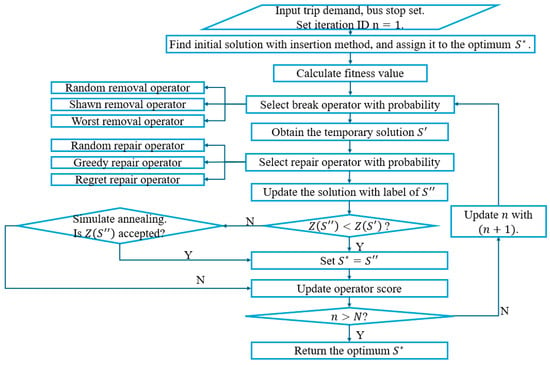

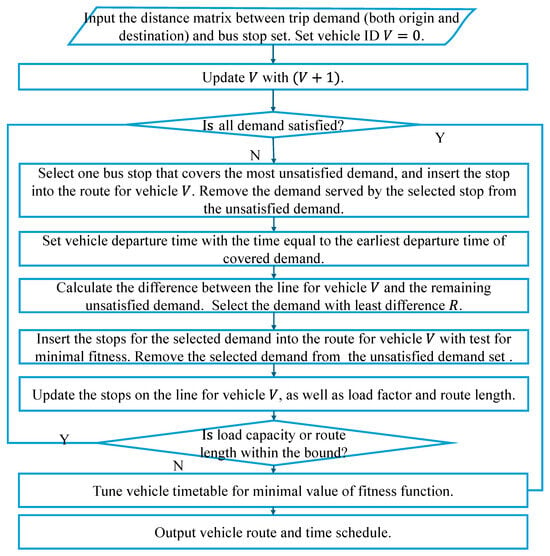

Figure 5 gives the framework of the ALNS method. It is composed of four modules, i.e., the initialization, the fitness function, the removal and insertion operator, and timetabling. All the modules are customized to the proposed DRT model for efficiency and satisfying solutions. In the following, each module is detailed.

Figure 5.

ALNS framework for DRT routing and timetabling.

Figure 6 shows the flow for establishing the initial solution to the DRT route model. We start the DRT route to serve the OD pairs with the highest passenger flow. In the following, we prioritize combining the demand with least temporal–spatial difference from the proposed DRT route, given by

where is the sum of the origin and destination distance of demand from the stops on the current route , and refers to the maximal distance between demand covered by the current route .

Figure 6.

Flow for establishing the initial solution to DRT route.

The fitness function is composed of both the route optimization objective and the penalty from breaking the constraints to DRT routes. With the DRT objective function revised with respect to the penalty from the gap in DRT arrival time and passengers’ expected departure time, and additional DRT route constraints in route length and passenger load capacity, the fitness function poses a tighter requirement to DRT route solution compared to that in the literature. The fitness function is given by

where is the fitness function of DRT scheme , and is penalty cost from breaking the constraints of Equations (9)–(19). Specifically, is the sum multiplied by the large constant of the gap of the bound in Equations (9)–(19) to the actual value with scheme .

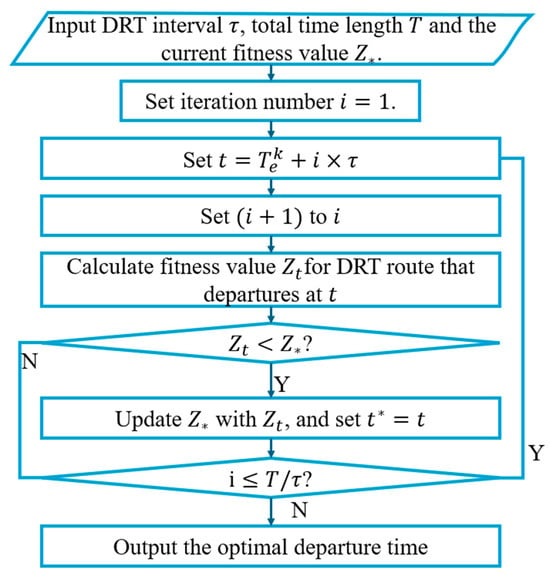

Timetable tuning for each DRT route is implemented according to the flow in Figure 7. The departure time of each bus is explored independently. It is determined by the time window of the planned departure time according to the demand accommodated by the first stop of the bus. The bus departure time is tested minute by minute between the lower and upper bound of the departure time window of the passengers getting on the first stop. The bus departure time minimizes the trip cost of all passengers on it.

Figure 7.

Algorithm for bus route timetabling.

In the following, both removal and repair operators are introduced. Assume a proportion of demand is removed from the current solution of a customized bus service. A total of three removal algorithms are proposed. (1) Random removal: The random removal algorithm is the easiest to select the percentage of trip demand from the current solution. (2) Shaw removal [53]: Randomly select one trip demand. Remove the demand with the least difference from it, until the percentage of trip demand is removed. Because significantly different trip demand can be remotely related and independently treated in the DRT route solution, while the similar trip demand is more likely to be bounded together in the following repair stage, this leads ALNS to the local minimum. Thus, removing the similar trip demand helps in two aspects, i.e., it retains the advantage of the current scheme, and explores the potential of better scheme. (3) Worst removal: Test the effect of removing each demand on fitness. Identify the demand whose removal brings the most gain in fitness. Remove the demand. Repeat the above procedure until the percentage of trip demand is removed from the solution.

Repair operators also include three types to add demand to the proposed DRT routes. (1) Random repair: Randomly select one trip demand from the removal algorithm. Randomly insert the demand into the solution. Test the feasibility of inserting the demand into a randomly selected position with respect to bus route length and passenger load. If the randomly selected position is feasible, insert the demand there; otherwise, randomly select another position until it is feasible. Then move on to randomly select another demand, until all removed demand has been inserted. (2) Greedy repair: Randomly select one trip demand. Test the feasibility and performance of inserting the demand to each position of the remaining bus routes. Insert the selected demand into the position that returns the best fitness. Move on to select the next demand that is removed, until all the removed demand has been inserted. (3) Regret repair: Test the feasibility and performance of inserting each removed demand into each position of the remaining bus routes. Identify the demand that brings the largest gap between the best and second-best position with reference to fitness. Insert the demand into the best position. Repeat the previous procedure until all the removed demands are inserted.

The probability of the above removal and repair operators is based on their weight. The operator weight is given by

where refers to the probability of selecting nth removal (or repair) operator. Initially, equal weights are assigned to each algorithm of either the removal or insertion operators. After a computation segment, i.e., a total of iterations, the algorithm weights are updated with

where means the updated weights of the nth removal (or repair) operator, refers to the times of adopting algorithm during the computation segment, is predetermined coefficient, and is the score of nth removal (or repair) operator.

Simulated annealing is based on the Metropolis criterion in order to accept some low-quality solutions with a small probability. That helps prevent the algorithm from being trapped in local optima. The Metropolis acceptance probability is given by

where is the probability of accepting the new solution, and refer to fitness value of the current solution and the new solution is the temperature change rate, and is the temperature in the previous iteration. If , new solution is worse than the current solution . In this case, the new solution is accepted with a certain probability. The higher the current temperature, the higher the probability of accepting the new solution. As the temperature decreases according to the temperature change rate, the probability of accepting the new solution decreases.

5. Case Study and Sensitivity Analysis

5.1. Scenario Information

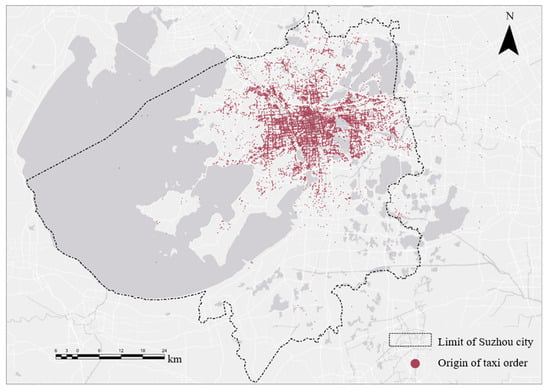

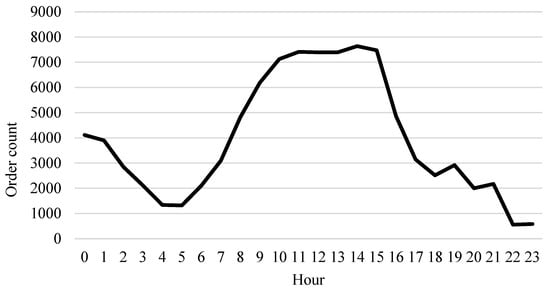

Take Suzhou, Jiangsu Province, China, as the case study. DRT demand is based on the taxi orders from 1 to 7 May 2022. An average of 92,641 trips is recorded each day. Figure 8 shows the spatial distribution of these trips, taking the example of 1 May. Figure 9 shows the average hourly taxi demand. It is observed that taxi orders concentrate in the urban area. The taxi demand is treated as the potential DRT demand. The established DRT route model is solved with the improved ALNS algorithm of this paper. Table 1 summarizes the parameter values for the proposed model and solution algorithm. The program was coded in Python 3.9.16 and executed on a computer equipped with an Intel Core i9-13700KF CPU 32 GB (Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) of RAM, and running the Windows 10 operating system.

Figure 8.

Spatial distribution of taxi trip demand.

Figure 9.

Average hourly demand.

Table 1.

Parameter values.

5.2. Result Analysis

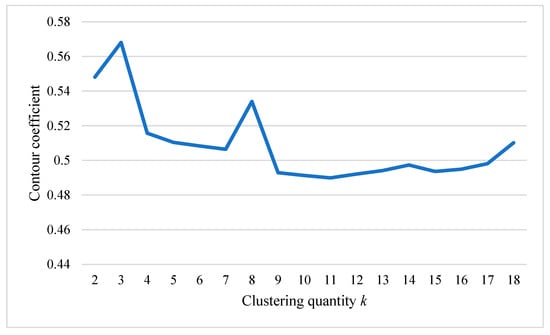

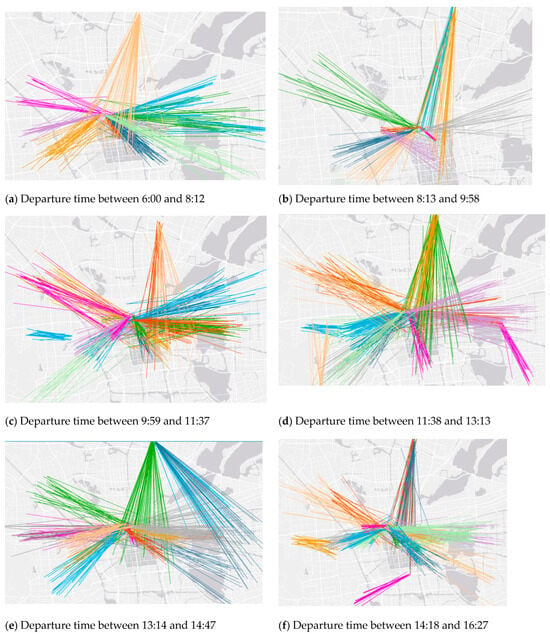

Figure 10 shows the contour coefficient from temporal clustering with different values of parameter . It is observed that manages to divide the trip demand into a reasonable set count of temporal clustering with a higher contour coefficient. Table 2 follows to demonstrate the time interval and trip count of each time clustering, which is further clustered spatially with the KNN algorithm for each time period. After deleting the temporal–spatial clustering with trips fewer than 20, Figure 11 shows the temporal–spatial clustering results before 16:28, after which taxi demand decreases rapidly and is less suitable to be served by DRT.

Figure 10.

Contour coefficients for temporal clustering.

Table 2.

Results of temporal clustering.

Figure 11.

Temporal–spatial clustering results (Different colors of lines indicate different clusterings).

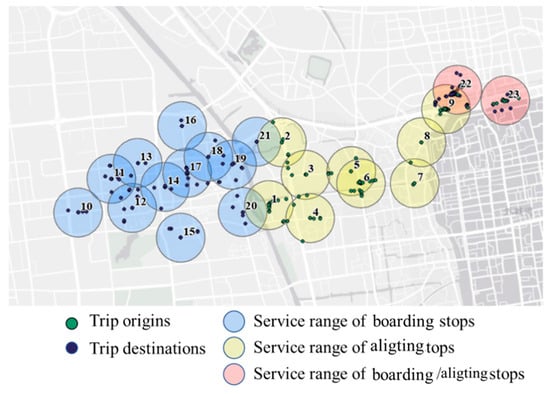

Take the temporal–spatial cluster with highest demand () from the period between 14:18 and 16:27 for the following analysis, whose origin and destination points are shown in Figure 12. The boarding and alighting bus stops are selected with the adaptive -medoids method with parameter values of DRT coverage rate and stop spacing m.

Figure 12.

Sample demand and selected boarding and alighting bus stops (numbers indicate stop ID).

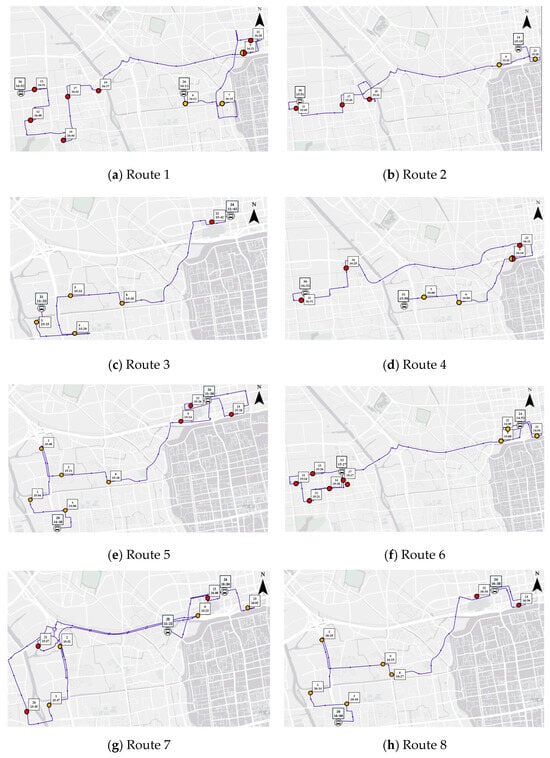

Table 3 shows the departure time and trip count of the demand covered by the selected boarding bus stops. All the demand covered with the selected boarding stops will be sent to the alighting stops within the tolerance band. Table 4 shows the correspondence between alighting stops and trip demands with demand arrival time gap. Figure 13 shows the proposed DRT routes, with detailed information in Table 5.

Table 3.

Departure time and trip count of the demand covered by the selected boarding bus stops.

Table 4.

Arrival time and trip count of the demand covered by the selected alighting bus stops.

Figure 13.

Proposed DRT routes (Orange circles for boarding stops, and red circles for alighting stops).

Table 5.

Detailed information of the proposed DRT routes.

Table 6 compares the results from our research with those in the literature [1,54,55,56,57]. Referring to the studies that incorporate DRT into public transit, and that focus solely on DRT or buses or taxis, our research tends to provide satisfying results with respect to passenger intensity, i.e., the ratio of passenger count to service trip distance. That is, our method manages to connect similar trip demand into the same DRT service. It is admitted our research does not bring better service efficiency regarding passenger intensity. Notably, the results are proposed with more a delicate objective function to reflect both operation cost and passenger cost with an asymmetric schedule deviation penalty embedded inside ALNS in the design of DRT.

Table 6.

Result comparisons.

5.3. Sensitivity Analysis

Here we test the effect of the parameters’ values on model performance, including the vehicle passenger capacity and the accepted time window band that is not penalized by early or late DRT arrivals. In detail, we investigate the effect of the proposed model performance when larger vehicles that can carry more passengers are employed. Larger vehicles cost more capital to purchase. Larger vehicles also cost more to operate due to their more intensive fuel consumption. Table 7 shows the fixed cost and variable cost of vehicles with different passenger capacities.

Table 7.

Varying vehicle types with passenger capacity and cost.

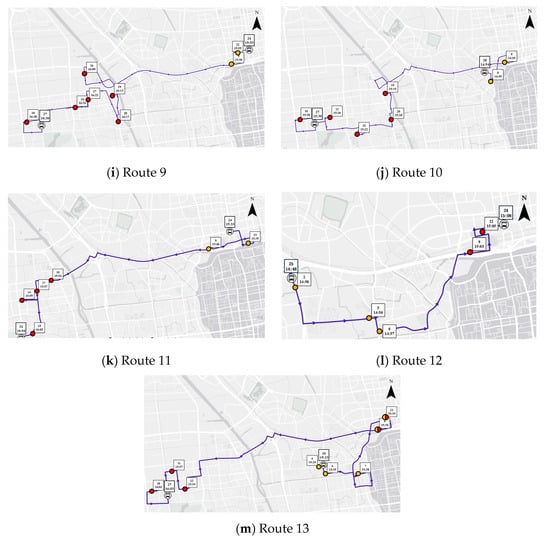

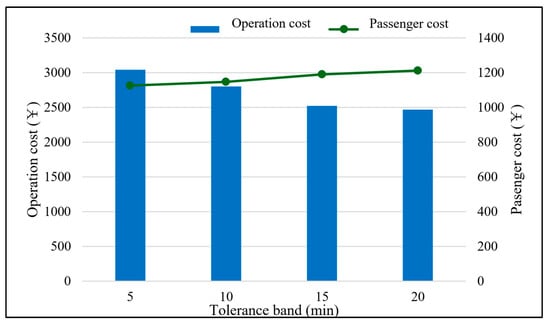

Figure 14 shows the results of operation costs against varying bus passenger capacities. It is observed that DRT operation costs increase with vehicle passenger capacity, which corresponds to higher fixed and variable costs. Note that passenger cost may decrease when larger vehicles are employed. This is because larger vehicles can accommodate more passengers, instead of forcing passengers to miss the neighboring DRT when the vehicle is full.

Figure 14.

DRT operation and passenger cost against varying vehicle types.

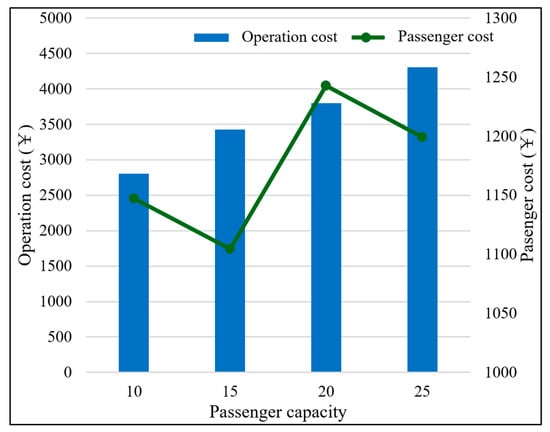

Figure 15 shows the changes in DRT operations and passenger costs when the passenger tolerance band increases. It is observed that as the tolerance band increases for the time window that early or late DRT vehicles are not published, the vehicle operation cost decreases continuously and significantly. For example, the vehicle operation cost is reduced by 18.8% with tolerance band of 20 min compared to that of 5 min. This is because larger tolerance bands allow DRT more flexibility to collect surrounding passengers without penalty or with lesser penalty from early or late arrival. In comparison, passenger cost generally increases with tolerance band. Note that the passenger cost increases slightly within 5.3% when the tolerance band increases from 10 min to 20 min. This validates the importance of a reasonable tolerance band for DRT service management.

Figure 15.

DRT operation and passenger cost against varying a tolerance band.

6. Conclusions

This study proposed a data-driven framework for designing sustainable customized bus services that jointly optimize routes and timetables using large-scale taxi trip data. The framework integrates the direction-aware temporal–spatial clustering of trip demand, a stop layout method that distinguishes boarding and alighting stops, and an ALNS algorithm with an asymmetric schedule deviation penalty and embedded simulated annealing.

The Suzhou case study, based on one-week taxi orders, shows that the proposed clustering and stop selection procedures can extract high-potential DRT markets and generate compact stop sets that satisfy coverage and walking distance requirements. On this basis, the optimized routes and timetables effectively pool dispersed passenger trips, yielding services with a reasonable ridership and operating distance, and reduced passenger costs. That enhances both DRT services’ attractiveness and operational efficiency. The passengers per kilometer of DRT services is averaged to be 0.64 pax/km. This helps to reduce the per capita emissions and energy by a factor of two or more compared to taxis, ride-hailing, or DRT in the literature, which brings passenger per kilometer around 0.3 pax/km [58,59].

From a sustainability perspective, shifting a portion of taxi-based travel to customized buses can reduce the total vehicle-kilometers traveled and support greener, shared mobility options. Nonetheless, the current framework is applied to a single city and assumes a homogeneous fleet, as well as implicit environmental benefits. Future work will extend the approach to multi-period and dynamic settings, consider heterogeneous vehicles and additional operational constraints, and couple the model with explicit energy and emission calculations to more directly quantify the environmental impacts. Also, allowing temporary demand to be inserted into DRT services after vehicles’ departure is also recommended. This allows DRT to better respond to trip demand and to promote trust in DRT services.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J.; Methodology, H.J. and Z.L.; Software, H.J. and Z.L.; Validation, H.J. and Z.L.; Formal analysis, H.J. and G.W.; Investigation, H.J. and S.Z.; Resources, H.J.; Data curation, Z.L.; Writing—original draft, H.J., G.W. and S.Z.; Writing—review & editing, H.J. and Z.L.; Visualization, H.J. and Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by National Natural Science Foundation of China grant number 52572345.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Melo, S.; Gomes, R.; Abbasi, R.; Arantes, A. Demand-responsive transport for urban mobility: Integrating mobile data analytics to enhance public transportation systems. Sustainability 2024, 16, 4367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, D.; Huang, M.; Xing, Z. Taxi origin and destination demand prediction based on deep learning: A review. Digit. Transp. Saf. 2023, 18, 47–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Cui, M.; Levinson, D. Exploring temporal variability in travel patterns on public transit using big smart card data. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2023, 128, 89–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Public Private Infrastructure Advisory Facility (PPIAF) World Bank. Urban Public Transport Toolkit, 1st ed.; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; pp. 78–85. Available online: https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099433011162311647 (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Liu, X. Characteristic analysis of bus load factor and suggestions on bus scheduling. In Advances in Energy Materials and Environment Engineering; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2022; Volume 44, pp. 56–63. Available online: https://www.taylorfrancis.com/chapters/edit/10.1201/9781003332664-118/characteristic-analysis-bus-load-factor-suggestions-bus-scheduling-xiaojuan-liu (accessed on 21 December 2025).

- Deka, U.; Varshini, V.; Dilip, D.M. The journey of demand responsive transportation: Towards sustainable services. Front. Built Environ. 2023, 8, 942651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santi, P.; Resta, G.; Szell, M.; Sobolevsky, S.; Strogatz, S.H.; Ratti, C. Quantifying the benefits of vehicle pooling with shareability networks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 13290–13294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Ouyang, Y. Mobility service design via joint optimization of transit networks and demand-responsive services. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2021, 151, 22–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Chae, M.; Yu, J.W. Optimization and Implementation Framework for Connected Demand Responsive Transit (DRT) Considering Punctuality. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zheng, L.; Liao, L.; Yang, X.; Sun, D.; Liu, W. A Multiline Customized Bus Planning Method Based on Reinforcement Learning and Spatiotemporal Clustering Algorithm. IEEE Trans. Comput. Soc. Syst. 2023, 11, 3691–3705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhong, M.; Xue, L.; Zhang, B.; Tu, H.; Tan, C.; Kong, Q.; Guan, H. Simulation Analysis of Bus Passenger Boarding and Alighting Behavior Based on Cellular Automata. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, W.; Zeng, L.; An, K. Dynamic vehicle routing problem for flexible buses considering stochastic requests. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2023, 148, 104030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.; Song, R.; He, S.; Xu, W.; Jiang, M. Clustering passenger trip data for the potential passenger investigation and line design of customized commuter bus. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2018, 20, 3351–3360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, A.; Dou, Z.; Qi, L.; Wang, L. Flexible route optimization for demand-responsive public transit service. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2020, 146, 04020132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, Y.; Chow, C.Y.; Lee, V.C.; Ng, J.K.; Li, Y.; Zeng, J. CB-Planner: A bus line planning framework for customized bus systems. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2019, 101, 233–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Miwa, T.; Morikawa, T. Recursive decomposition probability model for demand estimation of street-hailing taxis utilizing GPS trajectory data. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2023, 167, 171–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, W.; Lv, Y.; Ouyang, Q.; Ren, Y. A bus passenger flow prediction model fused with point-of-interest data based on extreme gradient boosting. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Luo, Q.; Cai, Q. Coordination of last train transfers using potential passenger demand from public transport modes. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 126037–126050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, R.; Li, T.; Pu, R.; Yang, J.; Tang, D.; Yang, L. NaGB-DBSCAN: An improved DBSCAN clustering algorithm by natural neighbor and granular-ball. Inf. Sci. 2025, 719, 122445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Oshanreh, M.M.; Khaloei, M.; Khan, N.A.; MacKenzie, D. Effect of trip attributes on ridehailing driver trip request acceptance. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2025, 1, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, Q.; Wu, Q. Tree-based and optimum cut-based origin-destination flow clustering. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Li, T.; Wang, S.; Jeong, M.H.; Soltani, K. A multidimensional spatial scan statistics approach to movement pattern comparison. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2018, 32, 1304–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, J.; Yang, L.; Chen, F.; Li, S.; Gao, Z. Physics guided deep learning-based model for short-term origin–destination demand prediction in urban rail transit systems under pandemic. Engineering 2024, 41, 276–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.; Kim, H.; Lee, J. Combining reinforcement learning with genetic algorithm for many-to-many route optimization of autonomous vehicles. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 26931–26942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, E.H. eXplainable DEA approach for evaluating performance of public transport origin-destination pairs. Res. Transp. Econ. 2024, 108, 101491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacquez, G.M. A k nearest neighbour test for space-time interaction. Stat. Med. 1996, 15, 1935–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, M.Y.; Miao, L.X.; Shan, J. A spatio-temporal distance based two-phase heuristic algorithms for vehicle routing problem. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Natural Computation, Tianjin, China, 14–16 August 2009; pp. 352–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Hislop-Lynch, S.R.; Kim, J.; Zhu, R. Agent-based simulation modeling of a Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) station using smart card data. In Proceedings of the 2017 Winter Simulation Conference (WSC), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 3–6 December 2017; pp. 4538–4539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harmann, D.; Trick, J.S.; Bienzeisler, L.; Friedrich, B. Moving beyond assumptions: Stop times and key determinants for pick-ups and drop-offs in ridepooling systems. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2025, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Sun, Z.; Liu, X. Optimized Skip-Stop Metro Line Operation Using Smart Card Data. J. Adv. Transp. 2017, 2017, 3097681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Bao, D.; Cheng, H. Evaluation of Demand Degree and Location Method of Airport Bus Stations in Urban Areas. Transp. Res. 2023, 9, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Quadrifoglio, L. Feeder transit services: Choosing between fixed and demand responsive policy. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2010, 18, 770–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galarza Montenegro, B.D.; Sörensen, K.; Vansteenwegen, P. A large neighborhood search algorithm to optimize a demand-responsive feeder service. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 127, 103102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Guo, J.; Guo, X. Bi-level Programming Model and Solution Algorithm for Decision-Making on Passenger Route Allocation of Coach Stations. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Intelligent Computation Technology and Automation (ICICTA), Changsha, China, 20–22 October 2008; Volume 1, pp. 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Zhou, K.; Yang, X.; Peng, X.; Song, R. Optimization method of customized shuttle bus lines under random condition. Algorithms 2021, 14, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wang, T.; Xu, W.; Li, H.; Yuan, Y. A novel model and algorithm for designing an eco-oriented demand responsive transit (DRT) system. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2022, 157, 102556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D.; Gu, Y.; Wang, S.; Liu, Z.; Zhang, W. A two-phase optimization model for the demand-responsive customized bus network design. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2020, 111, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Poon, M.; Yuan, Z.; Qiao, Q. Time-dependent customized bus routing problem of large transport terminals considering the impact of late passengers. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2022, 143, 103859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, L.C.; Zhou, L.; Liu, J.; Zhou, X. Customized bus service design for jointly optimizing passenger-to-vehicle assignment and vehicle routing. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 85, 451–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Z.; Chen, Y.; Li, H.; Zhang, K.; Sun, J. Customized bus network design based on individual reservation demands. Sustainability 2019, 11, 5535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Long, S.; Liu, Y.; Meng, F.; Luan, X. Integrated Optimization of Vehicle Scheduling and Passenger Assignment of Demand-Responsive Transit and Conventional Buses under Urban Rail Transit Disruptions. J. Transp. Eng. Part A Syst. 2025, 151, 04025037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanik, S.; Yılmaz, S. Optimal design of a bus route with short-turn services. Public Transp. 2023, 15, 169–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Yang, H.; Fan, W.; Wang, D. Optimizing service design for the intercity demand responsive transit system: Model, algorithm, and comparative analysis. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 254, 124180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourbakhsh, S.M.; Ouyang, Y. A structured flexible transit system for low demand areas. Transp. Res. Part B Methodol. 2012, 46, 204–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, R.; Guan, W.; Zhang, W.; Meng, F.; Zhang, Z. Customized bus routing problem with time window restrictions: Model and case study. Transp. A Transp. Sci. 2019, 15, 1804–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, S.; Dayarian, I.; Li, J.; Qian, X. A branch-cut-and-price algorithm for a dial-a-ride problem with minimum disease-transmission risk. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2205.05324. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, S.; Mehran, B. Cost analysis of different vehicle technologies for semi-flexible transit operations. Res. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2024, 130, 104159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belhaiza, S. A data driven hybrid heuristic for the dial-a-ride problem with time windows. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Honolulu, HI, USA, 27 Novembe–1 December 2017; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schiffer, M.; Walther, G. An adaptive large neighborhood search for the location-routing problem with intra-route facilities. Transp. Sci. 2018, 52, 331–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Sun, Q.; Tang, Y. Demand-Responsive Transport Dynamic Scheduling Optimization Based on Multi-agent Reinforcement Learning Under Mixed Demand. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks, Lugano, Switzerland, 17–20 September 2024; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoo, H.; Teoh, L.; Meng, Q. A bi-objective optimization approach for exclusive bus lane selection and scheduling design. Eng. Optim. 2013, 46, 987–1007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Ma, Z.; Wallace, M.; Harabor, D.D. Departure time choice user equilibrium for public transport demand management. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.18202. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, P. Using Constraint Programming and Local Search Methods to Solve Vehicle Routing Problems. In Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming—CP98; Smolka, G., Ed.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1998; Volume 1520, pp. 417–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höing, N.; Burla, P.; Louen, C.; Böhnen, C.; Kuhnimhof, T. Integrating demand-responsive services into public transport networks—Results from agent-based simulation of demand-responsive transport scenarios for the city of Aachen. J. Public Transp. 2025, 27, 100143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, C.; Maciejewski, M.; Wu, H.; Nagel, K. Demand-responsive transport for students in rural areas: A case study in Vulkaneifel, Germany. Transp. Res. Part A 2023, 178, 103837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shbeeb, L. The relation between transit service availability and productivity with customers satisfaction. Transp. Res. Interdiscip. Perspect. 2022, 16, 100716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inturri, G.; Giuffrida, N.; Ignaccolo, M.; Le Pira, M.; Pluchino, A.; Rapisarda, A.; D’Angelo, R. Taxi vs. demand responsive shared transport systems: An agent-based simulation approach. Transp. Policy 2021, 103, 116–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villani, M.G.; Cigolini, F.; Ortolani, F.; Suriano, D.; Prato, M. The smart ring experience in l’Aquila (Italy): Integrating smart mobility public services with air quality indexes. Chemosensors 2016, 4, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wenzel, T.; Rames, C.; Kontou, E.; Henao, A. Travel and Energy Implications of Ridesourcing Service in Austin, Texas. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2019, 70, 18–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.