Abstract

Immersive technologies such as virtual reality (VR), augmented reality (AR), mixed reality (MR), and multisensory interaction are increasingly deployed to support the transmission and presentation of intangible cultural heritage (ICH), particularly within tourism and heritage interpretation contexts. In cultural tourism, ICH is often encountered through museums, heritage sites, festivals, and digitally mediated experiences rather than through sustained community-based transmission, raising important challenges for interaction design, accessibility, and cultural representation. This study presents a narrative review of immersive human–computer interaction (HCI) research in the context ICH, with a particular focus on tourism-facing applications. An initial dataset of 145 records was identified through a structured search of major academic databases from their inception to 2024. Following staged screening based on relevance, publication type, and temporal criteria, 97 empirical or technical studies published after 2020 were included in the final analysis. The review synthesises how immersive technologies are applied across seven ICH domains and examines their deployment in key tourism-related settings, including museum interpretation, heritage sites, and sustainable cultural tourism experiences. The findings reveal persistent tensions between technological innovation, cultural authenticity, and user engagement, challenges that are especially pronounced in tourism context. The review also maps the dominant methodological approaches, including user-centred design, participatory frameworks, and mixed-method strategies. By integrating structured screening with narrative synthesis, the review highlights fragmentation in the field, uneven methodological rigour, and gaps in both cultural adaptability and long-term sustainability, and outlines future directions for culturally responsive and inclusive immersive HCI research in ICH tourism.

1. Introduction

The global growth of cultural tourism has fundamentally reshaped how intangible cultural heritage (ICH) is encountered, interpreted, and transmitted, with immersive technologies such as augmented reality (AR), virtual reality (VR), and mixed reality (MR) increasingly mediating these encounters. Unlike tangible cultural heritage, ICH includes many cultural elements such as oral traditions, performing arts, social customs, rituals, crafts and knowledge systems. In tourism contexts, the transmission of ICH increasingly relies on short-term, experience-oriented encounters that prioritise interpretation, interaction, and visitor engagement rather than long-term community-based transmission [1,2]. But due to the acceleration of modernisation, globalisation and digital transformation, many kinds of ICH have been undermined by the weakening of its transmission, loss of context or even extinction. A key issue in current ICH digitisation approaches is that they are often more focused on technical implementation than on user experience and accessibility [2,3,4,5]. Technologies such as VR heritage applications, interactive AR museum displays, and immersive installations have been widely adopted in cultural tourism settings, including museums, heritage sites, and visitor-oriented exhibitions [4,5,6,7], but such technologies often fail to consider accessibility for users with disabilities, marginalised communities, and people with low digital literacy. This review focuses on the application of immersive HCI technologies for the presentation and transmission of intangible cultural heritage in tourism-facing contexts, where interaction design directly shapes visitor experience, accessibility, and cultural interpretation. Through a critical review of the existing literature and practical case studies, this paper systematically analyses the key technological trends, mainstream methodological approaches and remaining accessibility issues in this field to provide theoretical reference for the integration of technology and culture.

Digitisation of physical cultural heritage (i.e., artefacts, monuments) can be done through various techniques such as 3D scanning and reconstruction to achieve high-fidelity virtual versions [8,9,10]. The living expressions of ICH include human gestures, traditional movements, oral narratives and ritual practices. Its cultural meaning and value is based on direct sensory experience and participatory transmission, rather than static preservation [2,5,11]. This creates a unique problem for HCI researchers: how to translate the multisensory, performative, and interactive essence of ICH (which relies on embodied experience and situational engagement) into digital technologies that are currently dominated by visually centric, static presentation [3,4,12].

In order to address this core problem, a number of technological solutions have been proposed. Which relies on embodied experience and situational engagement, into digital technologies which are predominantly visual-centric and static in presentation [3,4,12]. VR-based heritage simulation systems can give users an experience of historical events, traditional performances and lost cultural practices in virtual environments [6,13,14], which addresses this challenge by reconstructing the “situational interactivity” of ICH. By providing a lost cultural context (i.e., vanished folk rituals), VR technology is able to compensate for the lack of the performative nature of ICH in static digital displays.

AR applications are widely used in museums, public spaces, and heritage-based tourism environments to construct historical narratives, support interactive interpretation, and enhance visitor engagement [7,15,16]. This helps to solve the problem as it allows for “multisensory engagement” with the physical carriers of ICH. Unlike one-way visual presentations, real-time interaction is enabled by AR technologies to link the physical artefacts with the information about them, thus restoring the interactive nature of ICH. AI-based gesture recognition and haptic feedback technologies are being employed to recreate traditional craft techniques, dance movements and ritual processes in virtual spaces [3,4,17].

Despite this, these technological approaches still have their limitations. For VR experiences, lightweight devices such as Google Cardboard have been adopted in museum settings, often in combination with smartphones [18]. However, in tourism contexts, high-fidelity immersive experiences are often facilitated by expensive professional equipment and require a level of digital literacy that many visitors may not possess [5,8,19]. This results in a participation barrier for disadvantaged groups, including low-income communities and marginalised rural populations that have limited access to digital devices [5,20], who often lack the resources or digital skills required to engage with high-quality VR experiences.

While AR is capable of merging the physical and digital worlds, it can also oversimplify cultural knowledge by lacking the contextual socio-cultural background of ICH [21,22]. A striking example came from a mobile AR installation developed to present the leather tanning process, an ICH practice closely tied to local architecture and central to many people’s livelihoods [21]. The installation functioned by using a tannery scale model on a table to introduce the AR system. The AR layer displayed over the tannery showed animated 3D visuals illustrating the different stages of the tanning process, with the aim of providing educational value. However, the animated AR content mainly focused on the technical aspects, such as soaking and applying tannins to hides, while overlooking socio-cultural dimensions such as intergenerational knowledge transmission, the significance of tools, and the community’s reliance on tanning for livelihood [21]. A static and linear presentation of a complex, living practice is a key limitation of AR, which often prioritises visual clarity and legibility [22]. Gesture and haptic technologies could be useful in addressing issues related to contextual background; however, they have very high technical complexity and low popularity among the general public [4,17].

These issues point to a contradiction in the core premise that technological advancement does not necessarily translate into accessibility, inclusivity, and cultural authenticity [12]. In order to make inclusive access to immersive technologies centred on ICH possible, it is not only hardware limitations that need to be overcome, but even when digital systems are freely available, usability and inclusive design are often neglected [20,23]. Many of the current immersive experiences are visually and interactively heavy, which does not provide sufficient accessibility for people with visual impairments, mobility problems, or cognitive disabilities [23,24]. Design-related issues such as language barriers and cultural insensitivity have also contributed to the marginalisation of certain groups, thus raising questions about ‘who benefits from digital cultural heritage projects and who is excluded’ [5,6].

This study employs a narrative review method to analyse 97 studies on immersive HCI applications for ICH, with particular attention to tourism-oriented contexts such as museums, heritage sites, community exhibitions, and cultural tourism experiences. In particular, it critically appraises the methodological approaches adopted in HCI research to design and evaluate immersive ICH experiences, the incorporation of user-centred design and participatory co-creation models, the methods used to evaluate the effectiveness of the digital representation of ICH, and the extent to which usability and accessibility design considerations are incorporated [4,5,6,7,14,20].

Given the interdisciplinary nature of this topic, which spans HCI, digital humanities, cultural heritage studies, and interaction design, the narrative review provides a structured yet flexible framework for identifying the types of ICH being studied, the technologies applied, the strengths and weaknesses of current methods, and the research gaps [5,12,14,15]. By integrating insights from multiple fields, this study aims to lay the foundation for more inclusive, user-friendly, and culturally responsible digital ICH pathways, thereby advancing the living transmission of ICH in the digital age [3,5,7,13].

This study focuses on four interrelated questions:

- (1)

- What types of ICH have been explored in HCI research, and how are they classified based on intrinsic attributes and technological adaptability?

- (2)

- How are AR, VR, MR, and multisensory systems applied to different types of ICH in tourism and heritage interpretation contexts, and what usage trends do they exhibit?

- (3)

- What challenges and limitations do the digitisation and interactive presentation of ICH face (e.g., accessibility, usability, inclusivity)?

- (4)

- What methods does HCI research employ to design and evaluate immersive ICH experiences in order to ensure cultural sensitivity and widespread accessibility?

Through an analysis of these questions, this study aims to provide direction for future research, promoting the responsible application of immersive technologies within the field of ICH while striking a balance between the core values of technological innovation and cultural heritage.

2. Methodology

2.1. Search Strategy

This study adopts a narrative review with a structured search and screening strategy, consistent with interdisciplinary digital heritage research practices [25]. While narrative reviews emphasise interpretive synthesis, a structured search procedure was incorporated to ensure transparency and objectivity, given the fragmented and cross-disciplinary nature of immersive HCI and intangible cultural heritage (ICH) [15,26].

The search covered major academic databases, including Web of Science, Scopus, and IEEE Xplore [25]. The search time frame extended from the inception of each database to 2024, allowing the review to capture the full development of immersive technology applications in ICH [26].

Search terms incorporated both cultural and technological dimensions:

- Intangible Cultural Heritage: “Intangible Cultural Heritage,” “ICH,” “Oral Traditions,” “Traditional Performing Arts,” etc.

- Immersive Technologies: “Virtual Reality,” “Augmented Reality,” “Mixed Reality,” “Extended Reality/XR,”

- “Multisensory Interaction,” etc.

- HCI/Scenario-related: “Human-Computer Interaction,” “Virtual Museum,” “Digital Preservation,” “User Experience,” etc.

A complete list of search terms and database query formulas is provided in Appendix A.

Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” were used to construct formulas such as: (“Virtual Reality” OR “Augmented Reality” OR “Mixed Reality”) AND “Intangible Cultural Heritage” AND (“Human–Computer Interaction” OR “User Experience”) [25]. Following common approaches in virtual museum research, citation tracing and the supplementation of grey literature (e.g., conference papers, technical reports) were applied to ensure diversity and coverage of emerging research [18,27].

Two researchers independently screened titles, abstracts, and full texts to minimise bias, following dual-review practices adopted in XR heritage workflows [12,28]. This process yielded 145 potentially relevant records, including journal papers, conference proceedings, and technical reports [4,12].

2.2. Selection Criteria

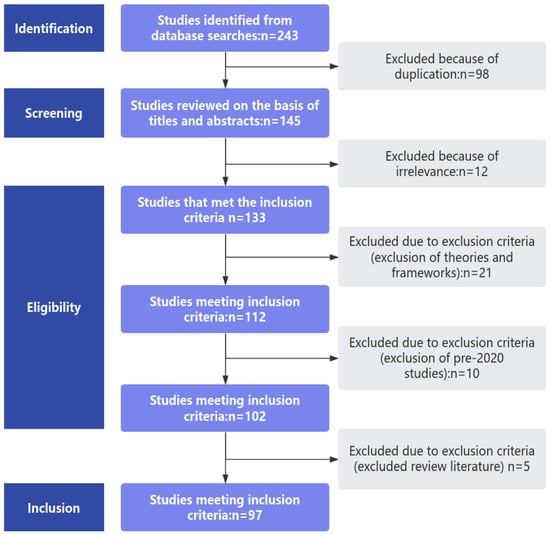

This review follows a structured, multi-stage screening logic common in narrative reviews of emerging technologies [25,26], progressing through the stages of Identification → Screening → Eligibility → Final Inclusion.

Identification stage

A comprehensive database search was conducted using combined technological and cultural keywords, such as (Virtual Reality OR Augmented Reality OR Mixed Reality) AND Intangible Cultural Heritage AND Human–Computer Interaction. This ensured broad coverage for the subsequent eligibility assessment [25].

Screening stage

Duplicate records were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened to exclude:

Studies unrelated to immersive technology applications in ICH; Studies focusing solely on tangible cultural heritage; Purely theoretical or technical papers without cultural or interaction contexts [26]. This produced an initial set of relevant documents for the full-text review.

Eligibility stage

Full texts were assessed across three dimensions: content suitability, temporal validity, and publication type.

- (1).

- Content suitability

Included studies had to present practical applications of immersive technologies (VR/AR/MR/multisensory systems) in ICH contexts, covering system design, user experience, cultural effects, or transmission practices.

Examples include:

Metaverse-based virtual museum research [25]; VR interaction with traditional musical instruments [4]; Excluded were conceptual frameworks without empirical cases or interaction scenarios [15].

- (2).

- Temporal validity

Although the search spanned all years, only post-2020 publications were included in the core dataset. This reflects the recent maturation of immersive technologies and ensures the reviewed evidence captures the latest developments. Representative retained works include: the v-Corfu VR/AR project [23]; the bamboo weaving VR system [29]. Earlier works were used only for contextual background, not for analytical inclusion.

- (3).

- Publication type

Only original empirical or technical research was included, such as:

EEG-based evaluations of emotional responses in VR [30]; mixed-reality devices for traditional craftsmanship [2]. Excluded were review papers, overviews, and bibliometric analyses [15,26].

Final inclusion

As illustrated in Figure 1, two independent reviewers conducted multi-round screening (titles → abstracts → full texts), following dual-validation procedures used in XR cultural heritage workflows [12,28]. A final set of 97 studies met all the criteria and formed the analytical corpus, covering journal articles, conference papers, and technical reports.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the inclusion and exclusion process of the studies.

3. Results

3.1. Research Design Types

The 97 included studies adopted diverse research designs, reflecting the interdisciplinary nature of research on immersive human–computer interaction technologies in the field of intangible cultural heritage (ICH). Based on the core characteristics of the research methods, they can be classified into four main types: conceptual-validation studies, quantitative research, qualitative research, and mixed-methods research, with each method type assuming different research objectives in analysing the interaction between technology application and cultural heritage.

As shown in Table 1, 18.6% of the studies centred on technology prototyping and feasibility validation, aiming to build a foundational framework for the application of immersive technologies to the ICH domain. For example, a blockchain-based metaverse virtual museum scheme was proposed to verify the adaptability of decentralised technology in the digital preservation of cultural heritage [25]. Li et al. developed the “CubeMuseum” augmented reality prototype, which explores how to enhance user engagement and learning experiences in virtual museum scenarios through tangible interaction design (e.g., using a physical cube as an interaction device to present 3D cultural relic models) [31]. Most of these studies focus on the development of technological processes, such as the Extended Reality Museum Application workflow proposed in earlier work [32], providing methodological reference points for subsequent empirical research.

As shown in Table 1, the majority of studies (52.6%) used quantitative research, which is now the predominant method of research in the field, to quantify the effects of technology applications. The majority of the studies used experimental designs or standardised scales. For example, electroencephalography (EEG) was applied to monitor users’ physiological and emotional responses during VR experiences [30], whereas a sense-of-presence scale was used to quantify the experience of headset-based interactions [33]. Quantitative studies usually focus on indicators such as user performance, for example, how efficiently users interact with the system. These results then provide empirical evidence for technology optimisation. For example, technology acceptance has been identified as an important factor in collaborative MR heritage applications [34]. Another indicator concerns learning effects and the ways in which knowledge is transferred.

20.6% of the studies used qualitative research, focusing on the in-depth exploration of subjective experiences and cultural contexts through ethnography, interviews, narrative analysis, and other methods. For example, users’ emotional responses to different digital museum experiences have been examined through unbalanced data analysis [35]. Nijdam (2023) highlighted the tension between cultural sovereignty and adaptation to technology through a case study of Sami digital narratives in indigenous games [36]. These studies emphasise the importance of cultural authenticity in the application of technology and often focus on user perceptions in relation to traditional cultural practices.

Only 8.2% of studies combined quantitative and qualitative methods to achieve triangulation, balancing empirical rigour with scenario complexity. For example, quantitative data on users’ cultural learning effects and technology acceptance were collected through standardised questionnaires, supplemented by qualitative feedback on collaborative interaction experiences obtained from semi-structured interviews in a mixed-reality (MR) heritage study [34]. In addition, observational records of visitors’ operational processes on a hybrid MR installation were combined with in-depth interviews on user experience to comprehensively assess the suitability of the technology for the transmission of Tinos marble crafts heritage [2].

Table 1.

Distribution and proportion of research methods across 97 studies on immersive human–computer interaction and intangible cultural heritage.

Table 1.

Distribution and proportion of research methods across 97 studies on immersive human–computer interaction and intangible cultural heritage.

| Research Method Type | Number of Studies | Proportion (%) | Representative Research Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conceptual Validation | 18 | 18.6 | [25,31] |

| Quantitative Research | 51 | 52.6 | [30,33] |

| Qualitative Research | 20 | 20.6 | [13,37] |

| Mixed Methods Research | 8 | 8.2 | [2,38] |

Overall, the dominance of quantitative studies reflects the field’s emphasis on the measurability of technological effects. In contrast, proof-of-concept studies exemplify the fundamental role of technological prototyping in ICH digitisation. Although the proportion of qualitative and mixed-methods research is relatively low, they have irreplaceable value in revealing the cultural context and subjective experience of users, and the three types of methods together constitute the methodological system of cross-disciplinary research on technology and culture.

3.2. Intangible Cultural Heritage Challenges Addressed in the Studies

This section critically examines how existing research conceptualises, frames, and problematises intangible cultural heritage (ICH) within immersive technologies. The analysis identifies four overarching issues: (1) the ontological characteristics of ICH and their implications for digital mediation; (2) cultural loss, distortion, and epistemic reduction during digitisation; (3) persistent tensions between authenticity and user experience; and (4) the inadequacy of current evaluation frameworks for capturing cultural transmission.

3.2.1. Cultural Characteristics and Their Implications for Digital Mediation

ICH encompasses dynamic, expressive, and community-embedded practices. The reviewed studies acknowledge this diversity but often fail to fully account for the implications these characteristics have for digital mediation. Performing arts such as dance, opera, and traditional music are fundamentally embodied forms grounded in synchrony, affect, and co-presence. Their meaning emerges through relational dynamics between performer and audience, performer and environment, and performer and community. Although motion capture and VR rendering can reproduce physical movements, these systems struggle to convey kinaesthetic intentionality, ritual timing, and collective atmospheres that shape cultural meaning [4,20,39]. Similarly, traditional craftsmanship relies heavily on tacit knowledge, including sensory cues such as resistance, weight, texture, and temperature. These qualities are core to understanding craft processes, yet they remain challenging to encode within current XR frameworks. Immersive representations tend to prioritise visual fidelity at the expense of material agency and processual authenticity, flattening the apprenticeship system into simplified step-by-step instructions [2,40]. Oral traditions and narratives present additional challenges. Their storytelling logics are non-linear, adaptive, and audience-responsive, shaped by improvisation, memory, and situational context. Attempting to capture these narrative structures using fixed 3D scenes, linear scripts, or pre-set branching paths reduces cultural plurality to system-friendly formats, resulting in a loss of narrative elasticity and relational storytelling [36]. Rituals and social practices further highlight these tensions. Their symbolic power derives from collective participation, temporal sequencing, spatial choreography, and cosmological significance. Yet many immersive reconstructions reduce rituals to performative spectacles without fully addressing the embedded social rules, intersubjective hierarchies, and spiritual dimensions that shape their meaning [40,41]. Traditional knowledge systems and spatial memory forms likewise require contextual sensitivity and ecological embeddedness. Yet XR platforms often encode this knowledge in abstracted, generalised forms divorced from local traditions and lived environments [14,41,42]. Taken together, these examples illustrate a deep ontological mismatch: ICH is fluid, relational, and multi-sensory, whereas immersive systems are discrete, modular, and representational. Few studies explicitly interrogate this epistemic tension, representing a critical gap in current scholarship.

3.2.2. Cultural Loss, Distortion, and Epistemic Reduction

Digitisation is frequently framed as preservation, yet the reviewed literature shows that immersive mediation often results in structural cultural losses. These occur not only at the level of aesthetic detail but also in epistemological and symbolic domains. At a surface level, limitations in rendering and modelling lead to visual simplification. For instance, the translucent quality of shadow puppets, central to their aesthetic is often lost due to computational constraints, reducing the expressive vocabulary of the tradition [28]. However, deeper distortions arise from the necessity of fitting ICH into computational models. Immersive systems require clear boundaries, explicit rules, and stable representations, but many ICH practices derive their value precisely from being ambiguous, fluid, or polyvalent. As a result, digitisation frequently enforces:

- Epistemic closure, where cultural knowledge is frozen into canonical “versions”;

- Symbolic reduction, where ritual, mythological, or embodied complexity is simplified;

- Temporal flattening, where the processual unfoldings of a tradition are compressed;

- Cultural sanitisation, where controversy, conflict, or change is omitted for clarity or usability.

These reductions raise concerns about epistemic injustice, as they privilege external interpretations and technological constraints over culturally grounded knowledge structures. The literature rarely questions whose knowledge is encoded, whose is omitted, and how these decisions shape future understandings of cultural heritage.

3.2.3. Negotiating Authenticity, User Experience, and Power Relations

A recurring theme is the tension between preserving authenticity and ensuring accessibility or engagement. However, most studies treat this as a design optimisation problem rather than a site of cultural politics. Simplifying contextual information may improve usability, but it also risks erasing historical nuance, symbolic ambiguity, or culturally situated meanings [24]. Conversely, strict adherence to traditional forms may reduce appeal for younger audiences or novice users, potentially undermining intergenerational transmission [4,39]. Crucially, authenticity is often defined by designers, technologists, or institutions rather than cultural holders. This raises significant critical concerns:

- Who determines what counts as “authentic”?

- Who benefits from the digital representation?

- Do immersive systems reproduce existing cultural hierarchies?

- How are communities involved in decision-making?

Studies involving Sámi communities illustrate the importance of participatory narrative sovereignty, where community-led authorship prevents misrepresentation and cultural flattening [36]. Yet such approaches are rare; most systems adopt a designer-centric perspective, inadvertently reproducing extractive or paternalistic modes of digitisation.

3.2.4. Design and Evaluation Approaches for Immersive ICH Experiences

Across the reviewed literature, the design and evaluation of immersive intangible cultural heritage experiences reveal a field in transition, moving gradually from technologically driven frameworks toward approaches that attempt, though not always successfully, to engage with cultural meaning, authenticity, and lived experience. Most studies frame design and evaluation through usability, task performance, and user satisfaction, reflecting inherited methodological priorities from mainstream HCI. However, the suitability of these metrics for assessing cultural transmission, community resonance, or heritage sustainability remains largely unexamined. As a result, the current evidence base provides useful insights into interaction dynamics but remains limited in its ability to account for the deeper cultural work that ICH practices perform. User experience evaluation continues to dominate. Many immersive applications, particularly virtual museums and VR learning systems, measure effectiveness through emotional, cognitive, and behavioural indicators commonly used in HCI. EEG studies in virtual exhibitions, for instance, report heightened beta and gamma activity during interactive tasks such as annotating artefacts or leaving emoji-based responses, suggesting increased emotional arousal and cognitive engagement relative to passive navigation [30]. Similarly, mixed-reality learning environments for craft practices, such as VR systems for Dongyang bamboo weaving, show improved learner interest and reduced learning time compared with traditional computer-based instruction [29]. While such findings demonstrate that immersive systems can effectively attract and hold attention, they provide only a partial understanding of how users interpret cultural content, negotiate meaning, or integrate new knowledge into their own cultural frameworks. A growing number of studies attempt to address these gaps by incorporating multisensory interaction as a strategy for deepening immersion and enhancing cultural resonance. In museums and archaeological parks, for example, the integration of visual, auditory, and tactile cues has been shown to enhance users’ understanding of ritual settings or material techniques, even when the effects are not always quantified rigorously [43]. Multisensory XR platforms are praised for their potential to mirror the embodied and affective qualities of ICH, yet this potential is still underexplored. Most implementations treat sensory channels as experiential augmentations rather than as culturally specific modes of engagement. As a consequence, multisensory design often enriches immersion without necessarily strengthening cultural comprehension. Behavioural intention models, particularly those derived from the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), are sometimes employed to predict users’ willingness to continue engaging with ICH applications. Studies of collaborative mixed-reality systems, for instance, report that perceived enjoyment, ease of use, and perceived usefulness strongly influence intention to revisit immersive heritage experiences [34]. These findings highlight the importance of affective and motivational factors in sustaining engagement. Yet, they also underscore an implicit tension: sustained usage does not necessarily equate to meaningful cultural understanding. High enjoyment may indicate successful entertainment design rather than successful cultural transmission. Methodologically, mixed-methods approaches are becoming more common, combining quantitative measures such as usability scales (e.g., SUS, UEQ) with qualitative interviews or thematic analysis. This has allowed some studies to capture more nuanced perceptions of authenticity and personal interpretation [36]. For example, reverse-virtualisation models that log user navigation patterns while collecting post-experience interviews provide richer insights into how different demographics engage with heritage content [44]. Despite these innovations, such methods still tend to privilege user perspectives at the moment of interaction, rather than examining broader cultural or intergenerational impact. A notable shift within the field is the increasing critique of technologically centric evaluation frameworks.

Recent studies argue that immersive heritage applications should not be judged solely on their operational performance but on their contribution to cultural transmission, community engagement, and the safeguarding of intangible practices. However, many of these critiques stop short of proposing robust alternative evaluation paradigms. As a result, although scholars acknowledge the limitations of existing metrics, the field continues to rely heavily on them, perpetuating a gap between technological assessment and cultural relevance. In sum, while evaluation methods in immersive ICH research are evolving, they remain constrained by the epistemologies of mainstream HCI, which privilege efficiency, usability, and short-term engagement. The reviewed literature demonstrates incremental progress toward culturally grounded approaches, particularly through multisensory design and mixed-method evaluation. Yet a coherent methodological framework for assessing cultural transmission, authenticity, or community impact is still lacking. Moving forward, immersive heritage research must develop evaluation strategies that account not only for what systems enable users to do but also for how they support the living, relational, and intergenerational dimensions of intangible cultural heritage.

3.3. Human–Computer Interaction Issues Addressed in the Study

The reviewed literature demonstrates that the application of immersive technologies to intangible cultural heritage introduces a wide range of HCI challenges that extend far beyond technical implementation. Building on the ICH characteristics identified in Section 3.2, this section examines how immersive interaction design operationalises cultural practices, and how specific HCI choices shape, constrain, or reconfigure embodied, narrative, and social forms of heritage engagement. This section synthesises the HCI issues identified across the literature, examining not only how immersive technologies operationalise cultural practices but also how interaction design choices shape the forms of cultural knowledge that can be represented, transmitted, and transformed within digital environments.

3.3.1. Technical and Interaction Demands Across ICH Types

As summarised in Table 2, the studies highlighted notable differences in the interaction requirements associated with different forms of ICH. For example, VR-based follow-up training systems for traditional martial arts translate expert movements into motion-captured reference models, requiring precise alignment between user input and avatar feedback; however, studies report that limitations in tracking resolution and temporal synchronisation constrain interaction accuracy [45]. Systems such as VR gesture-learning tools for musical instruments, and cloud-based multi-user puppetry environments [4,39], showed that interaction success depended heavily on the ability of the technology to recognise subtle and continuous movements. However, several studies noted recurring issues with latency, incomplete motion capture, and restricted movement ranges, which disrupted interaction flow and reduced performance fidelity.

Table 2.

Interaction requirements identified across ICH types.

Craft-based systems also revealed distinctive interaction challenges. Immersive craft-learning platforms frequently relied on hand tracking or controller-based interactions, yet these studies reported that current input methods did not fully support actions requiring fine motor precision, pressure variation, or material resistance. For example, VR-based movable-type printing museums enable users to interact with virtual tools and follow sequential production steps; however, interaction remains largely procedural, with limited support for pressure variation, resistance, or fine motor modulation [47]. For oral traditions and narrative practices, studies indicated that interaction requirements centred on continuity, pacing, and user-driven exploration. Adaptive interaction trends were also observed in virtual museum environments employing conversational agents, where interaction design choices, such as humanoid guides versus animated artefacts, significantly influenced engagement patterns and user inquiry behaviour [48]. However, several studies reported that linear interaction models constrained users’ ability to explore multiple narrative paths, resulting in reduced engagement for traditions where variation is central. Rituals and spatial practices additionally required multi-user coordination or spatially anchored interaction. Mixed-reality museum installations that anchor virtual content within physical exhibition spaces rely on stable spatial tracking and sensor calibration; studies report that even minor misalignment or tracking drift can disrupt interaction coherence [49]. Nonetheless, the studies often noted challenges in maintaining positional accuracy, avatar alignment, or shared timing, impacting users’ perception of coherence in ritualised activities. Overall, the literature showed that different ICH categories placed different demands on immersive interaction, but many systems defaulted to generic interaction techniques regardless of cultural or practical requirements.

3.3.2. Application Patterns and Interaction Trends Observed in the Literature

As summarised in Table 3, across studies, several patterns emerged regarding how immersive technologies were applied to ICH contexts. A large proportion of VR and AR applications emphasised embodied interaction, using gesture-based input, motion tracking, or spatial exploration to enable deeper engagement. For example, AR gesture-controlled cultural learning applications [9], and VR-based performing arts simulations [4,46] demonstrated that embodied interaction enhanced user engagement, although technical limitations sometimes restricted the intended effects. A second trend involved the integration of multiple technologies to create hybrid interaction environments. Hybrid interaction patterns were evident in mixed-reality museum installations employing physical interfaces, such as rotating-screen systems that allow visitors to reveal virtual reconstructions through bodily movement, highlighting challenges related to calibration and interaction consistency [49]. However, the studies also remarked that combining modalities introduced additional challenges related to calibration, system complexity, and consistency of feedback. Collaboration emerged as another notable trend.

Table 3.

Technological application patterns and interaction trends.

Multi-user VR platforms supporting joint performance [39], and museum-based MR systems enabling shared exploration [2,52], highlighted the growing interest in social interaction. Studies reported that collaborative environments often improved user engagement and emotional involvement, although technical constraints such as network latency and inconsistent avatar behaviour occasionally disrupted synchronous participation. Finally, multisensory interaction was a recurring theme across the literature. Haptic systems simulating material textures [51], spatialised audio in ritual simulations [42], and experimental olfactory augmentation [3], were all cited as ways to increase immersion and approximate aspects of embodied cultural experience. Yet these systems also introduced challenges related to hardware accessibility, reliability, and integration with visual interfaces. Together, these trends illustrate the increasing sophistication of immersive ICH applications, while also revealing recurring constraints related to system design, calibration, and multi-modality.

3.3.3. Challenges and Limitations in Interaction, Technology, and System Performance

As summarised in Table 4, the studies consistently reported several types of challenges that affected the design and effectiveness of immersive ICH systems. One frequently cited limitation concerned input accuracy. Gesture-recognition systems, in particular, struggled with fine-grained movements, leading to interactions that users perceived as imprecise or inconsistent [4,38]. These inconsistencies frequently disrupted learning activities, craft tasks, and performance-based interactions. A second challenge related to the lack of tactile feedback in systems designed for craftsmanship or tool-based activities. Studies combining passive haptic interfaces with speech-based interaction in VR museums demonstrate improved immersion and presence; however, they also report increased system complexity, hardware dependency, and challenges in maintaining consistent interaction feedback across modalities [53].

Table 4.

Interaction, technological, and system limitations reported.

Several studies noted that this gap influenced user satisfaction and learning outcomes. For multi-user and spatially distributed environments, studies identified synchronisation issues, including delays in avatar movement, inconsistent rendering of shared objects, and difficulties maintaining spatial alignment [39,42]. These technical issues affected collaborative tasks and reduced users’ sense of shared presence. Studies also reported challenges related to system sustainability and deployment. Immersive installations often required specialised hardware, such as high-end VR headsets, motion sensors, or multi-camera tracking arrays, that increased installation and maintenance costs [33,38,42]. Museum-based systems highlighted difficulties adapting content to evolving software standards and hardware updates, leading to concerns about long-term accessibility [32]. In narrative-based applications, constraints emerged around interaction pacing and control. Studies found that interface mechanisms sometimes limited users’ ability to explore content at their preferred speed or to revisit narrative branches, restricting engagement in traditions that rely on open-ended exploration [1,36]. Overall, these findings indicate that while immersive systems can support engaging interaction experiences, they are limited by current hardware capabilities, system stability, and the technical demands of modelling complex interactions.

3.3.4. Methodological Approaches Reported in Immersive ICH Research

As shown in Table 5, the methodological approaches identified across the studies reflect varying priorities in HCI research on ICH. User-centred design (UCD) was widely used to refine interaction techniques and improve usability. Several studies prioritised usability-driven evaluation, such as heuristic assessments of AR-based ICH mobile learning applications, which identified interface simplicity and interaction clarity as key factors influencing accessibility [58].

Table 5.

Methodological Approaches in Immersive ICH Studies.

Technical performance evaluation was particularly prominent in studies involving gesture recognition, motion capture, and haptic feedback. Systems were frequently assessed using metrics such as tracking accuracy, latency, error rates, and frame consistency [33,38,42]. Although such evaluations yielded valuable information about system reliability, they offered limited insight into user perception or interpretive engagement.

Participatory design and co-creation were reported in a smaller subset of studies but played a key role in identifying interaction requirements for culturally embedded practices. Examples include mixed-reality craft installations developed in collaboration with artisans [2], and VR narrative systems involving Indigenous storytellers [36]. These studies reported that participatory approaches helped improve the relevance and validity of interaction designs.

Evaluation practices across the literature tended to combine usability scales, task-based metrics, and short post-experience interviews. VR museum studies, for instance, employed surveys and behavioural measures to assess learning outcomes and emotional responses [13,18,37]. However, most evaluations were short-term and conducted immediately after system use; few studies reported longitudinal assessment or follow-up measures. Additionally, relatively few studies involved cultural practitioners in evaluation, limiting insights into system fidelity from the perspective of cultural expertise. In summary, the methodological approaches emphasised usability and technical performance, with fewer studies addressing longer-term interaction effects or culturally grounded forms of evaluation.

3.4. Overview of Immersive HCI Applications in Tourism

HCI has become an important tool for reshaping how cultural heritage is presented, experienced, and transmitted in tourism contexts. Rather than functioning solely as display technology, immersive HCI enables new forms of cultural engagement by integrating virtual reconstruction, mixed-reality interaction, and multisensory feedback. These capabilities help address long-standing challenges such as conservation pressure, limited accessibility, low engagement among younger audiences, and the uneven distribution of tourism resources.

In tourism settings, immersive HCI strengthens the connection between visitors and cultural environments by transforming them from passive observers into interactive participants. It supports the “virtual–real synergy” model, allowing cultural content to be explored without placing additional strain on fragile heritage spaces, while also enhancing narrative depth and learning outcomes. At the same time, its flexibility allows tailored solutions for different tourism scenarios, heritage sites, urban cultural spaces, children’s cultural education, and remote or inaccessible ICH communities.

3.4.1. Application Scenario Expansion of Immersive HCI in Tourism Settings

The value of immersive HCI technology in tourism settings lies in its ability to reconstruct the relationship between cultural experience and space utilisation through “virtual-real synergy”, and to form differentiated solutions for the core pain points of different tourism scenarios. Specifically, it can be divided into four typical scenarios:

Cultural heritage sites often face the contradiction between “protecting fragile carriers” and “meeting experience demands”. Excessive concentration of tourists in physical spaces can disrupt the living transmission of ICH (such as simplification of folk performances and commercialization of traditional craft displays), while limiting the number of visitors can reduce the efficiency of cultural dissemination. Immersive HCI technology achieves a win-win situation of diversion and experience upgrade through “virtual replication + physical linkage”. The Jemaa El-Fna Square in Morocco has implemented the “El-FnaVR” system, which uses high-fidelity 3D modelling to recreate ICH performances such as storytelling and Gnawa music in the square. Tourists can “virtually be present” and interact through VR devices [42]. After the system was promoted, the average daily number of visitors to the physical square decreased, the number of incidents of trampling on cultural facilities declined, and the duration of tourists’ cultural experiences was extended, with an increase in the recognition rate of the “Gnawa music ritual process”. The Kampung Adat Pulo Garut traditional village in Indonesia launched the “Echoes of Tradition” VR project, which combines LiDAR scanning and the Unreal Engine to build a 3D virtual tour of the village. Tourists can first remotely understand traditional Sundanese architecture and handicraft processes through VR, and then participate in “in-depth workshop experiences” (such as bamboo weaving practice) in the physical village [40]. This model enhances the “experience carrying capacity” of the physical villages while reducing carbon emissions from tourism transportation. Compared to traditional car travel, remote VR experiences reduce the carbon footprint related to cultural tourism and prevent the influx of tourists from causing disturbances to the village ecology (such as trampling on farmland and an increase in household waste). The mixed-reality installation at the Museum of Marble Crafts in Tinos, Greece, integrates virtual and physical interaction by allowing visitors to simulate quarrying in a reconstructed virtual environment and then manipulate tangible tools in real space [52]. This hybrid “virtual-physical” approach enhances engagement and learning efficiency in traditional marble craftsmanship. Tourists first simulate the quarrying process through the MR device and then operate the physical tools under the guidance of the artisans, thereby improving the efficiency of traditional craftsmanship learning and reducing the equipment failure rate of the physical workshops.

In urban tourism, “micro-cultural spaces” such as streets, community stores, and historical building facades are often overlooked due to the lack of explicit display. Immersive HCI technology, through AR “superimposition of reality and virtuality”, activates the cultural value of these spaces and promotes the transformation of urban tourism from “commercial consumption-oriented” to “culture exploration-oriented”. Macao has designed an AR interpretation system for traditional street signs. These signs integrate traditional intangible cultural heritage porcelain painting techniques, but most tourists merely regard them as ordinary road signs [59]. When tourists scan the signs with their mobile phones, virtual artisans will demonstrate the process of porcelain painting and explain the connection between the road name and Portuguese–Australian culture (such as “Yapao Well Street” and the history of early immigrants fetching water). After the system was tested in the old urban area of Taipa, the football traffic of traditional pastry shops and handicraft workshops around the signs increased, and over half of the tourists said they understood the “Chinese and Western integration” cultural traits of Macao through AR. The “v-Corfu” project, developed by the Ionian University in Greece, provides an integrated virtual and augmented reality experience of Corfu’s cultural heritage. The system enables users to explore digitised urban and architectural landmarks through AR-enhanced content and interactive storytelling. User evaluation (n = 22) reported high satisfaction and motivation scores across all six UX dimensions, indicating that the application effectively fosters engagement and cultural awareness [23]. This technology application shifts urban tourism from “checking landmarks” to “in-depth cultural exploration”, helping to uncover the tourism value of the city’s existing cultural resources, and is in line with the sustainable tourism goal of “increasing the cultural value of the destination”.

The core pain point of insufficient appeal of traditional culture tourism to children lies in the mismatch between “static display” and “children’s concrete cognitive needs”. Immersive HCI technology transforms ICH into operable and explorable experience projects through gamification and interactive design, expanding the tourism group while achieving cultural cognition enlightenment.

The AR children’s picture book of Psiloritis Mountain in Greece, centred on the pastoral culture of the UNESCO World Geopark, presents the daily life of shepherds (such as herding and making cheese) through 3D animation [16]. Children can trigger interactive tasks by scanning the picture illustrations. “Help the virtual sheep find the pasture”, “Simulate the mixing of cheese”, and convey the “synergetic relationship between pastoral culture and mountain ecology” through voice explanations. Children “participate” in historical scenes such as the exchange of tools between 19th-century immigrants and indigenous people, and the construction of docks through VR controllers. Although the research found that “fantasy elements” (such as virtual magical animals) did not significantly improve the recognition of historical facts, most children said they wanted to visit the real Sydney Rocks area after playing the game, and most parents believed that this technology made the abstract cultural history perceivable.

For ICH sites located in remote and inaccessible areas (such as mountain villages or island communities), immersive HCI technology breaks the “geographical accessibility” barrier and enables “remote participatory tourism”, while also expanding the global dissemination channels for local ICH. The traditional diving culture of the Stari Most Bridge in Bosnia and Herzegovina is the core ICH of the region. The diving ceremony held every summer attracts a large number of tourists, but the remote location limits the participation of most people [6]. The research team developed a VR simulation system that allows participants to experience the traditional bridge-diving ceremony at the 17-m-high Stari Most Bridge in Bosnia and Herzegovina through 360° immersive video. The system enables users to explore the cultural environment and symbolic significance of the ritual, effectively enhancing their sense of presence and engagement with local intangible heritage [6]. Data shows that the application of virtual reality technology in the digital media environment significantly enhances user engagement. Compared to traditional methods, the VR environment demonstrates more precise scene control and stronger capability in extending users’ expectations, achieving notably improved overall performance. The research emphasises that virtual reality, as a key force in cultural heritage protection, is the cornerstone of future architectural heritage preservation. The Dongyang bamboo weaving in China was reconstructed through a VR-based virtual experience system [29]. Tourists wearing VR headsets could observe virtual artisans demonstrating key steps such as “unfolding”, “weaving”, and “finishing”, and perceive tactile and visual feedback within the immersive environment. The learning module was evaluated through comparative experiments involving eight participants, showing that the average time required to master basic bamboo weaving techniques in the VR system (369 s) was significantly shorter than that of traditional video learning (439 s) [29].

3.4.2. The Multidimensional Impact of Immersive HCI on Sustainable Tourism

Based on the three pillars of sustainable tourism proposed by UNWTO (environmental protection, community benefits, and cultural sustainability), immersive HCI technology reconfigures the interaction between “tourism—culture—community”, forming quantifiable and implementable positive impacts. These impacts are specifically manifested in the following dimensions:

The dynamic inheritance of ICH highly relies on specific natural and cultural spaces (such as squares, villages, workshops). Excessive tourism activities can lead to “ecological depletion” (such as environmental pollution) and “cultural depletion” (such as simplification of folk performances). Immersive HCI technology reduces the pressure on physical spaces through “virtual substitution” and “traffic regulation”, protecting the authenticity and integrity of ICH. Before the implementation of the VR project, the Kampung Adat Pulo Garut village faced typical challenges of over-tourism and environmental strain. The “Echoes of Tradition” virtual tour, developed through Unreal Engine, provided an alternative digital approach that preserved spatial authenticity while enhancing cultural education and visitor engagement [40]. The final presentation of the “traditional echo” 3D virtual tour guide, supported by Unreal Engine, realises high-precision visualisation of traditional buildings and village environments, and combines immersive interactive experiences. After the VR diversion, the amount of garbage during the peak season decreased, the problem of farmland damage was largely eliminated, and at the same time, the traditional water conservancy facilities of the village (part of ICH) avoided the risk of being crushed by tourist vehicles. The “El-FnaVR” system, developed for Jemaa El-Fna Square, an element inscribed on UNESCO’s Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity, uses high-fidelity 3D modelling and spatial audio to recreate traditional performances such as storytelling and Gnawa music [41,42]. El-FnaVR effectively recreated the atmosphere of Marrakech’s UNESCO World Heritage Site, Jemaa El-Fna Square, fostering an immersive sense of presence and deeper understanding of its living cultural traditions [41].

One of the core goals of sustainable tourism is to “make communities the main actors in tourism development rather than passive recipients”. Immersive HCI technology binds tourism revenue deeply with ICH inheritance through “community participation in design” and “value feedback mechanism”, enhancing the cultural inheritance enthusiasm and economic sense of gain of the community. The VR cultural project focusing on the Minangkabau community in Negeri Sembilan, Malaysia, aimed to preserve traditional dances and musical expressions through virtual reality. The research team proposed a model incorporating motion capture, sound processing, and expressive visualisation to represent the Minangkabau’s intangible cultural heritage authentically. The project emphasised cultural fidelity in costume and movement design to reflect local traditions and aesthetics [20]. The project revenue was used to establish the “Minangkabau Cultural Heritage Fund”, supporting the training of young inheritors and the renovation of cultural venues. Tracking showed that the average income of local cultural inheritors increased, and the proportion of young people willing to learn traditional dances rose. In the mixed reality crane installation at the Museum of Marble Crafts on the island of Tinos, Greece, local artisans and museum experts participated in co-design workshops to refine the virtual quarry scene. Their feedback informed improvements to the system’s haptic realism, particularly the simulation of weight and material resistance during the marble lifting process [2]. Compared to non-interactive media or pure digital environments, this model can significantly enhance visitors’ interest and participation. Evaluation results show that mixed reality technology is expected to become a powerful medium for museums to create immersive interactive experiences that integrate physical and intangible cultural heritage.

In traditional tourism, ICH is often simplified as “photo-taking spots” or “commercial symbols” due to “traffic orientation” (such as simplifying Miao silver jewellery to decorative pendants, ignoring its ritual significance). Immersive HCI technology retains the deep cultural connotations of ICH through “context reconstruction” and “community supervision”, achieving “dynamic inheritance” rather than “static display”. In the VR game Gufihtara eallu, developed during the 2018 Sámi Game Jam, Sámi community members collaborated in the narrative and design process [36]. Centred on the traditional legend of the Gufihtar, mythic underground spirits whose songs taught humans the art of Joik, the game integrates elements of Sami oral storytelling and cosmology. Through immersive narration and interactive exploration, it conveys the Sami philosophy of coexistence between humans and nature. By integrating indigenous digital games and development as a form of digital narrative, it can impart the indigenous knowledge system and intangible cultural heritage to players. In the mobile AR installation illustrating the leather-tanning process on the island of Syros (Greece), the system initially focused on the technical stages, soaking, tanning, and finishing, while later evaluations suggested the need to enrich the narrative with cultural aspects such as intergenerational knowledge and the symbolic significance of tools [21]. The system examined the impact of the device on user participation, experience, and knowledge acquisition, improving the awareness of tourists of the “connection between tanning process and local economic history”.

3.4.3. Practical Challenges of Immersive HCI in Tourism Applications

Although immersive HCI technology demonstrates significant value, existing research has revealed that it faces three core challenges in tourism scenarios. These challenges arise from the mismatch between the technical characteristics and the requirements of the tourism environment, and they need to be addressed through technological optimisation and policy coordination:

The hardware requirements and maintenance costs of immersive technology have become the main obstacles for its promotion in small and medium-sized tourist destinations, especially in less developed areas. Professional VR headsets (such as Oculus Rift S or HTC Vive Pro) typically cost between USD 1000 and USD 3000, posing financial barriers for small cultural institutions. For example, outdoor AR applications must cope with lighting variation, as screen visibility decreases under strong sunlight, while VR experiences need to accommodate differences in tourists’ vestibular sensitivity, with elderly tourists showing a higher incidence of VR motion sickness than younger users [24]. A markerless AR system developed by Indian researchers enables museums to create mobile-based virtual exhibitions without requiring specialised hardware [60]. Built with Google ARCore and Unity3D, it reduces setup costs and enhances accessibility for visitors in limited physical spaces. However, as a mobile AR system, its outdoor tracking performance still faces challenges that require further algorithmic optimisation.

With the development of “all-round tourism”, tourists expect to obtain a coherent cultural experience across multiple destinations (such as cross-regional ICH themed tourism routes), but current immersive HCI systems are fragmented due to “inconsistent data formats” and “missing interface standards”. Both the “Battle on Neretva VR” project in Bosnia and Herzegovina and the “v-Corfu” project in Greece were developed independently using the Unity engine for different platforms, namely a local museum VR installation and a multi-platform WebGL/VR exhibition [23,32]. However, due to their distinct build structures and platform dependencies, users cannot share or synchronise experiential data (e.g., learning progress or unlocked scenes) across destinations. This fragmentation of application ecosystems requires tourists to repeatedly download and register with separate systems, undermining continuity in cross-site cultural experiences.

The EU’s “Digital Heritage Cloud” initiative aims to establish a cross-regional platform for sharing cultural heritage data. However, only a few studies have adopted this standard [32]. Most regions lack a standard-setting mechanism for the “cultural tourism-technology-community” collaboration, making it difficult for immersive systems in different destinations to form an “experience synergy”, which limits the large-scale development of ICH tourism.

Sustainable tourism emphasises “inclusiveness”, but current immersive HCI technologies mostly design for “average healthy users”, with insufficient consideration for the accessibility of special groups such as tourists with disabilities and elderly tourists, resulting in “technological exclusion”.

Visually impaired tourists require tactile feedback and spatial audio to perceive cultural scenes. Although the potential of finger-specific vibrotactile feedback for enhancing cultural immersion in virtual museums has been demonstrated, most immersive systems still lack dedicated tactile adaptations for accessibility [51]. Tourists with limited mobility benefit from voice-controlled interfaces rather than gesture-based operations. It has been emphasised that combining gesture and voice recognition offers one of the most natural and accessible interaction models in cultural heritage environments [24]. Additionally, a test of visually impaired users in a VR museum in Greece showed that without tactile feedback adaptation, the cognitive accuracy rate of visually impaired tourists for “virtual cultural textures” was much lower than that of ordinary users. At the same time, elderly tourists have low tolerance for complex gesture interactions. Only a few tourists over 65 years old can independently complete “multi-step gesture operations” (such as “grab-rotate—place” in VR), and after optimisation (simplified to “click—slide”), the satisfaction of elderly tourists with the experience has improved [24]. However, in existing research, only a few projects have optimised interactions for elderly tourists, making it difficult for this group to enjoy immersive cultural experiences.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

In recent years, immersive technologies—including Augmented Reality (AR), Virtual Reality (VR), Mixed Reality (MR), and multisensory interaction systems—have substantially reshaped the preservation, education, and public engagement of Intangible Cultural Heritage (ICH). This review examines the effectiveness, limita-tions, and future trajectories of immersive technologies within the ICH domain, offering a critical analysis of their methodological, cultural, and technological implications.

4.1. Discussion

4.1.1. Key Insights from Research Design Analysis

Research has identified three key contradictions in the digitalisation of intangible cultural heritage (ICH). These include the conflict between technical standardisation and the dynamic nature of ICH transmission, the tension between cultural authenticity and user experience adaptation, and the imbalance between the goal of technological accessibility and the financial barriers that limit implementation. From a research design perspective, current immersive systems face structural limitations in adapting to the complexity of ICH practices. VR-based motion-capture frameworks often lack the sensitivity required to record highly nuanced kinetic qualities. This limitation affects the fidelity of movement-centric traditions such as Tai Chi. Similarly, existing 3D reconstruction pipelines struggle to preserve fine-grained textures, layered materials, and handcrafted details. In traditions such as shadow puppetry, this results in incomplete cultural representation at the modelling stage. Beyond technical capture, practical constraints, practical constraints further complicate project implementation. These include the high cost of VR hardware and the lack of interoperability across folklore visualisation modules developed by different teams, particularly in under-resourced regions A further challenge concerns the tension between cultural authenticity and user adaptability. In virtual museums, simplified interpretations of ritual processes may improve comprehension efficiency but risk diminishing cultural significance. If the technical team does not deeply collaborate with the cultural guardians, the digital content may be misinterpreted in its symbolism, e.g., treating ritual props as decorations rather than a sign of cultural information. User adaptability also varies significantly across different groups. Older users typically have a lower tolerance for VR-induced motion sickness than younger users. Children tend to prefer animated presentations, whereas cultural guardians place greater emphasis on stylistic authenticity. Participatory co-creation models offer practical strategies for addressing these contradictions. For example, involving craftsmen in the parameter tuning of mixed-reality systems for marble craftsmanship enhances the cultural affinity of digital content. Similarly, community collaboration platforms that allow users to adjust scene details, such as the colour schemes of traditional clothing in VR environments, can strengthen users’ perception of cultural authenticity.

4.1.2. Understanding ICH Engagement and Digitalization Challenges

The study reveals a triple core contradiction in the process of ICH digitisation: the conflict between technological standardisation and ICH viability, the tension between cultural authenticity and user adaptability, and the tension between technological universality and cost barriers.

VR technology is increasingly applied in movement-based ICH practices and has been used to support Tai Chi learning; however, existing systems fail to capture subtle expressive qualities such as qi yun, resulting in culturally diluted representations [19]. In artefact-based traditions, 3D digitization techniques have been employed for digitally reconstructing shadow puppetry, yet current imaging methods cannot reproduce layered textures or carved materiality, leading to loss of visual and symbolic detail [28]. The challenge is further amplified by the high cost of immersive hardware, VR headsets typically range from USD 1000–3000, which restricts accessibility and limits participation in resource-constrained cultural preservation contexts [32].

Balancing cultural authenticity and user adaptability is another key challenge. In virtual museum settings, prioritising “non-observable information” while simplifying “interpretation-based cultural context” in textual presentation has been shown to improve users’ comprehension efficiency but may omit nuanced cultural details [7].

It has been pointed out that without the involvement of cultural holders in the technical team, digitised content may be vulnerable to symbolic misinterpretation, such as the simplification of ritual props into merely decorative elements [36]. Differences in user adaptability across groups are also significant. Older users have lower tolerance for complex gesture interactions in immersive systems [24]; children tend to prefer vivid animated presentations of cultural scenes, and cultural bearers place greater emphasis on original details such as the accurate restoration of the shapes and usage scenarios of pastoral tools [16].

In response to these contradictions, participatory co-creation models offer a promising pathway. In the mixed reality crane installation for marble heritage, experts in marble craftsmanship, museum curators, and community members took part in iterative co-design workshops, contributing feedback on virtual scene authenticity such as quarry environment details and tool operation logic to improve the cultural fidelity of the digitised content [2]. A cloud-based VR glove puppetry platform supports multi-user remote interaction with virtual glove puppets (e.g., operating puppet movements and simulating performances), enabling community members to participate in the digital dissemination of traditional glove-puppetry culture and strengthening users’ sense of cultural authenticity through collaborative engagement [39].

4.1.3. HCI Issues in ICH Digitization

Human–computer interaction research has systematically categorised the types of intangible cultural heritage (ICH) and thoroughly explored the application pathways of immersive technology. Different types of ICH present distinct technical requirements and research priorities. Traditional performing arts, which centre on physical expression, require interaction models that shift the experience from passive observation to active participation. These systems must also support real-time feedback and emotional transmission in multi-user contexts. Traditional handicraft relies on handmade skills and material perception, and its technological adaptation needs to simulate the physical properties of materials and the logic of the process, supplemented by step-by-step guidance and structured presentation of knowledge. Oral traditions and narratives utilise linguistic symbols as carriers, necessitating solutions to the problems of dialect recognition and non-linear narrative design, while also enhancing narrative immersion through virtual characters.

Ceremonies and social practices emphasise group participation, and the application of technology needs to restore the spatial scene, the division of labour and roles, and process timing, while avoiding the entertainment adaptation of cultural symbols through expert review mechanisms. Focuses on the systematic nature of practical knowledge, and it is necessary to visualise the tacit knowledge and build interactive design to support knowledge association and cross-generational transmission. Traditional sports require the accurate capture of movement specifications and power techniques, as well as the combination of real-time error correction with rule instruction. Spatial memory and folklore places focus on the historical restoration and integration of memory in physical space and establish the virtual linkage between scene switching and personal memory through spatial-and-temporal superposition design.

The application of immersive technology presents two significant trends: one is the transformation from ‘one-way display’ to ‘two-way interaction’, and the early information-push-based applications are gradually evolving into user customisation and community collaborative editing. Secondly, cross-technology integration has become mainstream, with fewer single-technology applications and more platform-based applications that combine multiple technologies, such as VR environments, MR guidance, and biosensing systems. However, technological applications still face many challenges, and it is difficult to replicate the embodied and multisensory dimensions of ICH, such as the tactile details of handicrafts and the ambient scent of rituals. There are epistemic differences between computational models and cultural knowledge systems, as well as conflicts between linear narrative logic and non-linear cultural expressions. There is a significant risk of cultural simplification and misinterpretation, as some platforms overemphasise visual effects or universality, thereby ignoring the uniqueness of local knowledge and symbol systems. There is insufficient sustainability of the system; short-term projects lack updating and maintenance mechanisms and are easily reduced to static archives. Limited community participation and insufficient representation of culture holders in the design process may lead to a disconnect between the content and community values.

The choice of methodology is closely related to the type of ICH, with process-driven heritage types r relying more on quantitative assessments of technological performance. In contrast, context-driven heritage requires stronger participatory co-creation with cultural actors. Future research needs to promote the integration of methodologies, e.g., combining 3D reconstruction accuracy testing and community memory collection in spatial memory heritage, to achieve a unity of technical rigour and cultural depth.

4.1.4. Insights for Tourism Practice: Balancing Technology, Culture, and Sustainability

A deeper examination of the reviewed studies reveals that cultural sustainability remains one of the least developed yet most critical dimensions of immersive ICH research. While VR, AR, MR and multisensory systems are widely presented as promising tools for revitalising ICH, their long-term contribution to cultural continuity is far from guaranteed. Across the literature, sustainability-related issues appear in fragmented form, embedded in case examples, technical limitations or tourism scenarios, but collectively they point to a more systemic challenge: immersive technologies risk producing representations that are engaging in the short term yet culturally reductive, technologically fragile and unevenly accessible over time. To address these concerns, this section synthesises insights from the studies into an integrated understanding of cultural sustainability, focusing on the interplay between cultural representation, technical practice and socio-economic contexts such as tourism.

One dimension of sustainability concerns the preservation of cultural depth and embodied meaning within immersive representations. Several studies note that the technical infrastructures used to digitise ICH, particularly motion-capture systems and 3D reconstruction pipelines, are often unable to reproduce fine-grained qualities essential to the cultural integrity of a tradition. VR motion-capture systems lack the sensitivity needed to capture nuanced expressive movements in practices such as Tai Chi, producing simplified or culturally diluted versions of highly sophisticated kinetic knowledge [19]. Similarly, 3D digitisation of artefact-based traditions struggles to reproduce layered textures and handcrafted details, as seen in the modelling of shadow puppetry, where the loss of visual and symbolic depth affects the sustainability of cultural knowledge transmitted to future users [28]. When such simplified representations are repeatedly circulated, they risk shaping public perception toward incomplete or distorted understandings of the tradition.

Cultural sustainability also depends on the extent to which immersive systems can maintain the contextual and symbolic logic of ICH. Several studies highlight that content designed without close collaboration with cultural holders tends to rely on visual clarity or entertainment value at the expense of ritual significance or narrative coherence. Simplifying ritual components for ease of comprehension in virtual museums may improve user efficiency but removes layers of cultural meaning that sustain the practice [42]. Misinterpretation of symbolic elements, such as treating ritual props as decorative visuals or overlooking the socio-cultural dimensions of craft processes, further undermines the cultural fidelity of digital experiences [2,28]. By contrast, studies adopting participatory co-creation demonstrate stronger sustainability potential. When craftsmen, storytellers or cultural experts are involved early in the design process, the resulting systems, such as mixed reality installations for marble craftsmanship or Indigenous storytelling games [2,36], tend to retain deeper cultural specificity and avoid symbolic erosion.