Abstract

One major bottleneck for the sustainable development of the aquaculture sector is the reliance on conventional feed ingredients, such as fishmeal and soy protein. Another challenge is nutrient loss from these systems, which contributes to environmental pollution but also represents a waste of valuable resources. To make aquaculture truly sustainable, a shift toward circular, sustainable systems is necessary. This study compared a regionally available alternative feed, based on blue mussel meal and pea protein concentrate, to a conventional fish meal and soybean control diet in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) reared in coupled aquaponic systems. Fish performance and stress levels, water quality, plant growth, and microbial quality were investigated. Growth performance and feed intake were similar between aquaponic and control recirculating aquaculture systems (RASs) during the control feed (CF) phase. Only the feed conversion ratio (FCR) was slightly lower in the aquaponic system during the mussel-pea feed (MPF) phase. Tatsoi (Brassica rapa) growth in the aquaponic systems was comparable to, or even greater than, that of the hydroponic control systems, throughout the experiment, especially during the MPF phase. In addition, the MPF had a positive impact on phenotypic parameters and contributed to enhanced shoot growth. However, the presence of pathogens with potential biohazard impacts on human and fish health remains a concern and warrants further investigation. In our study, Salmonella spp. was detected in both systems, but levels were considerably reduced with the MPF phase. In contrast, Escherichia coli was detected only in RASs and was absent from aquaponic systems. Overall, the findings support the potential of blue mussel and pea protein as sustainable, local feed components in integrated aquaponic production, contributing to nutrient circularity and reducing dependence on limited marine stocks and imported resources.

1. Introduction

The global population is projected to reach 9.7 billion by 2050, an increase of approximately 2 billion people over the next 30 years [1]. With this population growth and increased stresses on resources such as water, land, and nutrients, the demand for sustainable food production becomes increasingly critical [2,3]. A rapidly advancing farming technology that could help address this issue is aquaponics [2,4], a combination of aquaculture and hydroponics in a recirculating system [5]. Aquaponic systems offer several benefits, including nutrient recovery, reduced water usage, and increased profitability through the simultaneous production of two valuable yields [6].

According to recent data from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) is still one of the three most farmed fish species worldwide [1]. This species has proven suitable for aquaponic farming due to its hardiness and adaptability, including tolerance to suboptimal water quality, robustness under intensive culture conditions, efficient feed conversion, and compatibility with plant nutrient requirements [7]. By integrating fish farming with plant cultivation, aquaponics creates a closed-loop system allowing for the harvest of both crops and fish, all without the use of soil. In aquaponic systems, fish waste becomes a nutrient source for the plants [5,8]. Fish excretes ammonium (NH4+) as a waste product, and through the biological process of nitrification, it is converted into nitrite (NO2−) and, subsequently, into nitrate (NO3−) by beneficial nitrifying bacteria [9]. NO3− is the most readily absorbed nitrogen (N) form by plants, acting as a crucial nutrient for growth [10].

Most of the nutrients required by the plants in an aquaponic system are retrieved from fish and feed waste. Nevertheless, plants require certain mineral nutrients that are commonly deficient in fish feed and, consequently, in aquaponic systems, as they are often poorly retained in bioavailable form due to precipitation, microbial transformation, or uptake inefficiencies under typical aquaponic conditions [11,12]. These mineral nutrients include macronutrients such as potassium (K), phosphorus (P), and sulfur (S), as well as micronutrients such as manganese (Mn) and iron (Fe) [12]. Fe is especially essential for vital processes in plants and is commonly added as a supplement [13]. One way to achieve a water composition that meets hydroculture needs is by optimizing the fish feed composition [14].

Traditionally, fish feed for intensive systems such as recirculating aquacultural systems (RASs) and aquaponics has relied heavily on fish meal and fish oil derived from wild-caught fish [15]. This practice has raised significant sustainability concerns due to overfishing and the depletion of marine resources [16]. To reduce dependence on marine ingredients, alternative feeds have been developed using terrestrial plant-based proteins and oils, such as soy, corn, and wheat [15,17,18]. However, these terrestrial plant-based alternatives present their own challenges [19]. They often require large amounts of arable land and freshwater, which raises concerns about their environmental impact and competition with human food crops [19].

To address these issues, researchers have increasingly focused on finding sustainable protein alternatives supporting environmental sustainability and optimal fish health and growth [20,21]. Promising alternative protein sources in fish feed from low-trophic origins include yeast, insect, and mussel meal [21,22,23,24,25,26]. The blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) is of significant interest to local producers in finding raw materials for inclusion in the fish diet. This is especially true for Nordic countries like Sweden, where it is one of the major aquaculture species with an annual production of around 2000 tons [27]. Blue mussels are filter-feeding mollusks that can mitigate eutrophication through the removal of N in coastal ecosystems [28], thereby providing ecological services. In addition, mussel biomass presents a high-quality marine protein source [29], making blue mussels a potential ingredient in aquaculture. After harvest, not all mussels are suitable for human consumption. Undersized mussels or individuals with damaged shells are often discarded because they do not meet size or quality standards. Although currently treated as waste, these mussels represent a promising circular protein resource, as the meat can be recovered and processed for incorporation into animal feeds [30]. While the use of blue mussel meal has been explored as alternative feed ingredient primarily in marine aquaculture systems, including cage-based and RAS for carnivorous fish species [31,32,33], its incorporation into the diet of the omnivorous species Nile tilapia within an aquaponic system has not yet been investigated.

In order to optimize aquaponic systems, it is essential to monitor plant health and performance in relation to the fish feed composition. Tools for assessing these dynamics, such as phenotypic assessment based on image analyses and measurements of chlorophyll content and leaf area, are crucial. These measurements have been implemented as indicators of plant nutritional status and stress conditions [34].

The aim of the current study is to evaluate the potential of blue mussel meal as a sustainable feed ingredient for Nile tilapia in an aquaponic system and its impact on water quality, nutrient availability, growth, and health of fish and plants. The study also conducts phenotypic assessment using image analyses and evaluation of chlorophyll content and leaf area of the plants to develop an early warning system related to abiotic and biotic stress conditions. We hypothesize that fish and plant performance, growth, and health are improved when the fish diet is based on sustainable and organic sources using blue mussel meals compared to a conventional diet. With the numerous environmental benefits associated with blue mussels, their incorporation into the food production process offers an opportunity to evaluate and enhance the environmental sustainability of aquaponic systems.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design and Treatments

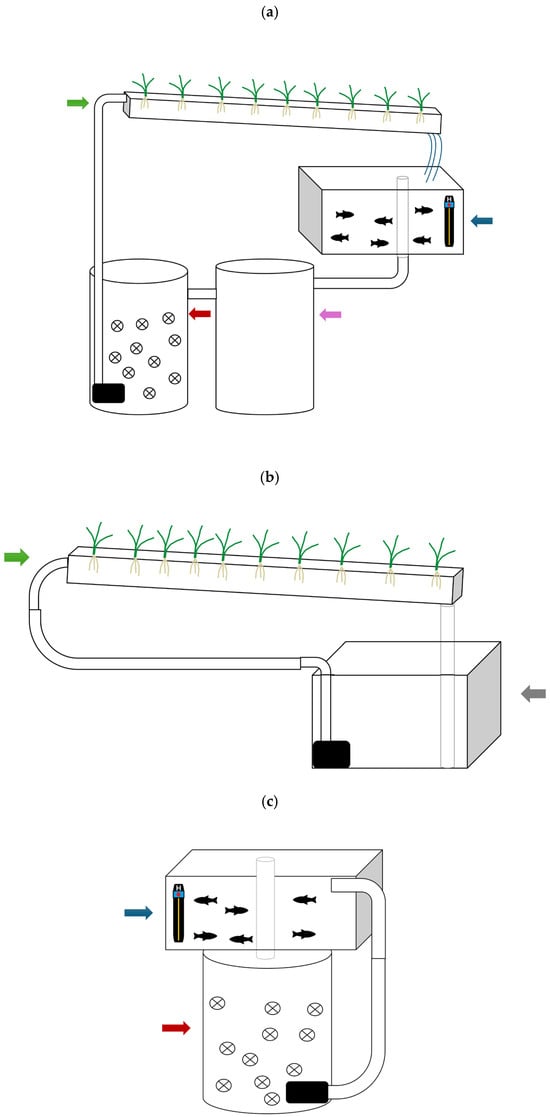

The experiments involved aquaponic systems (Figure 1a), hydroponic control systems with no fish (Figure 1b), and RAS control systems with no plants (Figure 1c). Each system was independently replicated three times (n = 3 per system type) and ran simultaneously. System compartments had the following volumes: fish tanks in aquaponic and RASs and nutrient reservoirs in hydroponic control systems of 50 L; biofilters in aquaponic systems and RASs of 70 L, containing 10% nitrifying bio media; and sump tanks in the aquaponic system of 80 L. The aquaponics and hydroponic systems included plastic gutters measuring 155 × 13 × 5 cm (10 L) to accommodate the plants. The total volumes for each system were as follows: aquaponics, 210 L; RASs, 120 L; and hydroponics, 60 L. Nutrient film technique (NFT) was used, where nutrient solutions were circulated. These compartments were also continuously aerated with air stone diffusers. Lighting was provided above the plants using high-pressure sodium lamps with a photosynthetic photon flux density (PPFD) emission range of 70–215 µmol m−2 s−1 in a 14:10 (light/dark) photoperiod. The mean PPFD measured across the plant canopy was 200 µmol m−2 s−1.

Figure 1.

Schematic representations of the three systems: (a) aquaponic, (b) hydroponic, and (c) RAS. Blue arrow: fish tank, purple arrow: sump tank, red arrow: biofilter, green arrow: hydroponic unit, gray arrow: nutrient solution reservoir, and H: heater.

Cultivation conditions in the greenhouse were monitored and maintained constant 70% relative humidity and an air temperature of 24 °C. Temperature was maintained using aquarium heaters set at 25 °C placed in the fish tanks and biofilters in the aquaponics and RASs (Figure 1a,c).

The Nile tilapia and Tatsoi (Brassica rapa) were used as model organisms for fish and crops, respectively. Tilapia is commonly used as a model fish in aquaponics and is described as a fast-growing and robust fish with the potential to adjust to a wide range of water conditions [35]. Tatsoi is a nutrient-rich leafy green depending on high N content for its growth [35]. To promote initial biofiltration, both system types were initiated prior to fish introduction using circulating water containing an active microbial inoculum. The inoculum consisted of a mature biofilter media with nitrifying bacteria provided by the same commercial fish farm that supplied the fish (Gårdsfisk, Åhus, Sweden). The exact microbial composition of the inoculum was not further characterized.

The experiments were conducted in two phases with two different types of fish feed for aquaponic systems and RASs in each phase. No washout period or system reset was applied between the two phases. The hydroponic systems received a standard mineral nutrient solution for hydroponic as described by Hoagland and Arnon [35], commonly referred to as the Hoagland solution, providing NO3−, P, K, S, calcium (Ca), and magnesium (Mg) as macronutrients, along with trace elements including Fe, Mn, zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), boron (B), and molybdenum (Mo). In phase 1, the used fish feed contained fishmeal and soy protein (hereafter referred to as CF, Table 1). The aquaponic systems and RASs were stocked with 15 fish in each fish tank with an initial weight of 7.80 ± 0.00 g (mean ± standard deviation, SD) in aquaponic and of 7.40 ± 0.00 (mean ± SD) in RAS. Tatsoi seedlings were introduced after fish stocking. A total of 20 seedlings were randomly distributed across the gutter in aquaponic systems, while 10 seedlings were placed in the gutter of hydroponic systems. To address commonly reported micronutrient deficiencies in aquaponic systems, the plants were supplemented with 1.72 g of Fe (28.7 mg L−1, YaraTera REXOLIN® D12, Yara International ASA, Oslo, Norway) and 24 g of MgSO4 (400 mg L−1, Epsom salt, CAS number 7487-88-9, Merk, Darmstadt, Germany) and applied two and six weeks after transplantation. In phase 2, the feed was changed to an alternative diet, without fishmeal and soy protein concentrate, replaced by Baltic mussel meal and pea concentrate (hereafter referred to as MPF, Table 1). The same fish, 15 fish in each tank of aquaponic systems and RASs, were kept in the system and had a mean weight of 22.30 ± 1.76 in aquaponic systems and of 21.34 ± 0.62 in RASs. New Tatsoi plants were introduced to the system as described in phase 1. The cultivation period of each phase was four weeks.

Table 1.

Ingredient composition and nutritional values of the control feed (CF) and mussel-pea feed (MPF) (source, Aleksandar Vidakovic, SLU, Uppsala, Sweden).

2.2. Water Quality

Temperature, pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and total dissolved solids (TDSs) were measured daily in the fish tanks of both aquaponic systems and RASs, as well as in the hydroponic water reservoirs in hydroponic systems, using a multiparameter probe (Combo, Hanna Instruments, Woonsocket, RI, USA). In addition, water quality was monitored twice a week using commercial photochemical test kits (Hach Lange GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany). The concentrations of NH4+, NO2−, and NO3− were measured with test kits LCK303, LCK341, and LCK339, respectively, using a DR3900 spectrophotometer (Hach Lange GmbH, Düsseldorf, Germany). Water consumption was measured, and the tanks were filled up accordingly with freshwater weekly. Additionally, water samples from the fish tanks, biofilters, and hydroponic units were analyzed by LMI commercial laboratory (Helsingborg, Sweden) using Spurway analysis methods for quantifying the concentration of micro- and macronutrients at the beginning, middle, and end of each of the experimental phases.

2.3. Fish Growth, Biometrics, and Cortisol Analysis

Initial, intermediate, and final biometric measurements were conducted across all the experimental phases. Prior to each sampling event, fish were fasted for 24 h. For sedation, 2 L of water from each system was transferred into a bucket with 50 mg L−1 tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222, Finquel®, Argent Chemical Laboratories, Redmond, WA, USA), buffered with calcium carbonate (CaCO3) to maintain a pH of 6.8–7.0. Once visibly sedated, fish were weighed, measured (fork length), and then transferred to a recovery bucket with continuous aeration until all fish had been measured and fully recovered.

At the final biometry of the phase with the MPF, after a 24 h fasting period, fish were anesthetized with 0.012 mg L−1 metomidate hydrochloride (Aquacalm, Syndel, Nanaimo, BC, Canada) dissolved in water for deep sedation. From each system, eight fish were sampled for blood sampling and subsequent plasma cortisol analysis. Fish were chosen to be representative of the tank population, with body weight close to the system’s mean and no visible sign of severe injury. Once deeply anesthetized, fish were weighed, measured, and subsequently euthanized with a sharp blow to the head.

Blood samples were then collected via caudal vessel puncture using a 23-gauge-needle and a 1 mL heparinized syringe to prevent coagulation. Samples were transferred into 0.5 mL Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min. The resulting plasma was aliquoted into new tubes and frozen on dry ice before storage at –80 °C for later analysis. The remaining fish were sedated using MS-222 protocol as previously described, then weighed and euthanized to conclude the trial.

For the growth parameters, the following growth performance indices were calculated after the feeding trial, averaged per experimental tank, experimental type of system, and per fish, where applicable. Using the initial weight (WI), final weight (WF), duration of the trial in days (d), feed consumption (FC), weight gain (WG), number of fish at the start (FI), and at the end (FF) of the feeding trial, weight gain (WG) (1), specific growth rate (SGR) (2), feed conversion ratio (FCR) (3), and survival (4) were calculated as follows:

WG (weight gain, g) = WF − WI

SGR (specific growth rate, %W day−1) = ((ln(WF) − ln(WI))/d) × 100

FCR (feed conversion ratio) = FC/WG

Survival (%) = (FF/FI) × 100

A radio immuno-assay (RIA) was used to determine cortisol concentrations in the plasma of fish as described by [36] using a cortisol antibody validated by [37].

2.4. Plant Growth Measurements

Plant growth was monitored weekly throughout all experimental phases. All plants were measured using 15 plants in the aquaponic systems and nine plants in the hydroponic systems. Plant height (cm) was recorded. At the final plant biometric sampling, eight plants were selected and separated into roots and leaves. Each plant part was wrapped in aluminum foil and weighed to determine wet weight, then dried in a drying oven at 70 °C for five days, after which the dry weight was measured.

2.5. Phenotypic Assessment of Plants

At harvest, the phenotypic assessment was performed using 10 plants in each aquaponic and hydroponic system. The quantum yield (QY) was assessed through measuring chlorophyll fluorescence using a portable modulated fluorometer (FP-100, Chl Fluorometer, Heiz Walz GmbH, Inc., Effeltrich, Germany), with the middle portions of mature, healthy, fully expanded tagged leaves at ambient temperature in plants dark-adapted for 15 min [38]. Leaf chlorophyll content was measured using a chlorophyll meter (SPAD-502; Minolta Camera Co., Osaka, Japan). Measurements were taken from three mature leaves located in the middle to upper canopy of each plant, and the values were averaged. For computer visualization, the analyses were conducted using a camera (Canon EOS1300D RGB digital single-lens reflex camera, mounted with a Canon EF-S 18–55 mm STM lens, Canon USA Inc., Huntington, NY, USA), and the image acquisition of the plants was captured with a Canon EF-S 18–55 mm STM lens from a top view angle. The image analysis was performed using ImageJ software (Version 1.54p) by following the procedure described in [39].

2.6. Microbial Analysis

The water samples for microbial analyses were collected at the end of each phase. An amount of 50 mL was centrifuged, and the pellet was suspended in 750 µL RNA/DNA shield (Zymo Research Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany). DNA and RNA were extracted with a Zymobiomics DNA/RNA miniprep Kit (Zymo Research Europe GmbH, Freiburg, Germany) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantification of the nitrification bacteria in the biofilter was based on the assessment of using Comammox amoA primers (comaA-244 F:TAYAAYTGGGTSAAYTA and comaA-659 R:ARATCATSGTGCTRTG), as described by [40]. Oomycetes in the hydroponic compartments were assessed using the forward primer ITS1-O (F:CGGAAGGATCATT-ACCAC) and the reverse primer 5.8s-O-Rev (R:AGCCTAGACATCCACTGCTG), as described by [41]. In the fish tanks, the primers E. coli Z3276 (F:GCACTAAAAGCTTGGAGCAGTTC; R:AACAATGGGTCAGCGGTAAGGCTA) and iroB (F:TGCGTATTCTGTTTGTCGGTCC; R:TACGTTCCCACCATTCTTCCC) were used for Escherichia coli and Salmonella spp., respectively [42,43]. Assessments were performed using the automated QX200TM Droplet DigitalTM PCR system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) [44]. A reaction mix composed of 10 µL QX200 EvaGreen Digital PCR Supermix, 0.5 µL each of forward and reverse species-specific primers, 7 µL of DNase/RNase free MilliQ water, and 2 µL of cDNA sample was prepared (final volume 20 µL). Samples were placed in the automated droplet generator. The plate containing droplets was sealed with pierceable aluminum foil using a PX1 PCR plate sealer (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) set to 180 °C for 5 s. The plate was then moved to a Touch Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) and run with the following thermal conditions: enzyme activation 95 °C for 5 min following by 40 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing and extension for 1 min with the temperature specific for the primer used. The procedure ended with signal stabilization at 4 °C for 5 min and 90 °C for 5 min and infinite hold at 4 °C. After thermal cycling, the plate was placed in a QX droplet reader (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). QuantaSoftTM software (Version 1.7) was used to run the instrument and analyze the data.

2.7. Ethical Conditions

The experiments were based on the permissions approved by the Swedish Board of Agriculture with permission number Dnr 5.2.18-10997/2024 for the ethical use of fish and permission number 2023-11-22 6.2.18-17898/2023 for the use of greenhouse facilities for experiments with fish.

2.8. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 29.0, IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). For comparisons between two treatment groups, independent-samples Student t-tests were used. Welch’s correction was applied when Levene’s test indicated unequal variances. For comparisons involving more than two groups, one-way ANOVA was performed. When ANOVA indicated significant differences, post hoc pairwise comparisons were conducted using the Bonferroni correction. Normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk tests and by examining the residuals. Homogeneity of variances was checked with Levene’s test. Data were log10-transformed when normality assumptions were violated, and Welch’s correction was applied if variances were unequal. All tests used a 95% confidence interval, and statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Water Parameters

Water parameters are presented in Table 2. Water temperature remained stable at the temperature set on the heaters (25 °C) in both aquaponic systems and RASs throughout all phases. In contrast, hydroponic systems, without additional heating systems, consistently maintained lower temperatures across the entire experimental period (21.5 °C). pH levels were relatively low in all systems, with the hydroponic systems reaching the lowest levels in both phases. EC and TDSs displayed similar patterns, with higher levels in the hydroponic systems across all phases. The addition of the Hoagland solution in the hydroponic systems increased the ionic strength of the water and, consequently, the EC and TDSs in these systems. Meanwhile, aquaponic systems and RASs maintained lower, comparable levels that gradually increased over time.

Table 2.

Overview of the measured water parameter variables: temperature, pH, electrical conductivity (EC), and total dissolved solids (TDSs). Measurements were taken daily during the CF (31 days) and the MPF (33 days) phases in the aquaponic, RAS, and hydroponic systems. Data are presented as mean (±SD) of n = 3 independent systems per treatment. Superscript letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05, one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc test). Significant p-values in the table are highlighted in bold.

Water levels of nitrogenous waste are presented in Table 3. In both phases, there was no difference in terms of NH4+, although aquaponic systems had a tendency to experience relatively higher NH4+ levels than RASs in the CF phase. NO2− levels remained low and similar in both systems during the CF phase but were significantly higher in the MPF phase in aquaponic systems (0.13 ± 0.01 mg L−1) compared to the RASs (0.06 ± 0.04 mg L−1), while remaining within tolerable levels for Nile tilapia [45]. NO3− concentrations increased steadily across all phases in both aquaponic systems and RASs, indicating the successful establishment of the nitrification process. NO3− kept on accumulating in both systems, with RASs consistently showing significantly higher values than aquaponic systems in both CF (27.61 ± 0.66 mg L−1 vs. 20.62 ± 1.43 mg L−1) and MPF phases (51.26 ± 1.07 mg L−1 vs. 39.14 ± 3.20 mg L−1).

Table 3.

Water concentrations of nitrogenous wastes (NH4+, NO2−, and NO3−) in fish tanks of aquaponic systems and RASs during the CF and MPF phases. Data are presented as mean (±SD) of n = 3 independent systems per treatment. Superscript letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05, t-test, (S) = Student t-test, assuming equal variances, (W) = Welch t-test for unequal variances). Significant p-values in the table are highlighted in bold.

3.2. Fish Growth, Biometrics, and Cortisol Analyses

The mean weight of fish, individual weight gains, SGR, and FI were comparable in both systems during both phases (Table 4). The FCR was comparable between aquaponic systems and RASs in the CF phase (0.62 ± 0.08 and 0.64 ± 0.03, respectively), whereas in the MPF phase, the FCR was higher in aquaponic systems than in RASs (1.07 ± 0.14 and 0.81 ± 0.04, respectively).

Table 4.

Growth performance, feed utilization, and survival of Nile tilapia in the aquaponic systems and RASs during the CF and MPF phases. Data are presented as mean (±SD) of n = 3 independent systems per treatment. Superscript letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05, t-test, (S) = Student t-test, assuming equal variances, (W) = Welch t-test for unequal variances). Significant p-values in the table are highlighted in bold.

At the end of the MPF phase, the mean cortisol concentrations in aquaponic systems and RASs were 28.70 ± 21.07 ng mL−1 and 30.99 ± 11.30 ng mL−1, respectively, with no significant differences observed between the system types (Student t-test, t(4) = −0.167, p = 0.876).

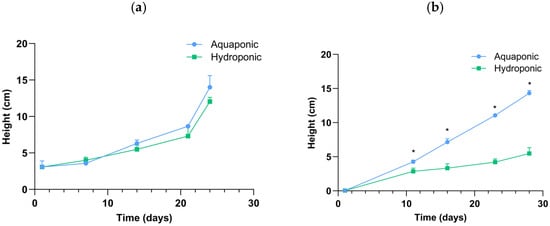

3.3. Plant Growth

Distinct growth patterns were observed between aquaponic and hydroponic systems across all experimental phases (Figure 2). In the CF phase, there was no difference between the two systems. During the MPF phase, significant differences were observed throughout the entire period (day 11 to day 28), with aquaponic systems demonstrating markedly greater growth performance. By the end of the feeding trials, mean plant height in aquaponic systems reached 14.00 ± 1.60 cm with the CF (day 24) and 14.31 ± 0.40 cm with the MPF (day 28). In contrast, hydroponic systems reached lower final heights of 12.04 ± 0.59 cm and 5.48 ± 0.85 cm, respectively.

Figure 2.

Plant height (cm) of Tatsoi in aquaponic and hydroponic systems during the CF ((a), 24 days) and MPF ((b), 28 days) phases. For both phases, each system had the following number of plants: aquaponic, n = 15; hydroponic, n = 9. Each system type included three replicates; data are presented as mean (±SD, n = 3). Asterisks indicate significant differences between groups, p < 0.05 (Student t-test).

3.4. Phenotypic Assessment of the Plant

Assessment of plant growth and physiological traits at the end of each feed experiment indicated significant differences between the plants grown in aquaponic systems compared with hydroponic systems (Table 5). During both phases, the shoot growth was higher in aquaponic systems compared with hydroponic systems. These differences were already visible during the CF phase (18.53 ± 2.71 g vs. 11.61 ± 1.91 g) but even more pronounced during the MPF phase (15.07 ± 1.77 g vs. 1.29 ± 0.33 g). The chlorophyll content (SPAD) was higher in aquaponic systems during the MPF phase only (44.81 ± 0.60 vs. 37.50 ± 1.58), while no effects on root weight or QY were observed in any of the phases.

Table 5.

Shoot fresh weight, root fresh weight, chlorophyll content (SPAD), and quantum yield (QY) of Tatsoi plants cultivated in aquaponic and hydroponic systems during the CF and MPF phases. Data are presented as mean (±SD) of n = 3 independent systems per treatment. Superscript letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05, t-test, (S) = Student t-test, assuming equal variances, (W) = Welch t-test for unequal variances). Significant p-values in the table are highlighted in bold.

3.5. Microbial Quality

No quantifiable levels of Oomycetes were detected using ddPCR analyses. On the other hand, Salmonella spp. were detected in fish tanks in both RASs and aquaponic systems during both experimental phases (Table 6). However, the number of copies and thereby the amount of these bacteria was always lower in aquaponic systems compared to RASs, and when the MPF was used in either phase (Table 6). A limited amount of E. coli was detected only in RASs during the CF phase. No E. coli was detected for either system during the MPF phase.

Table 6.

ddPCR analyses of the occurrence of Salmonella spp. and E. coli bacteria in the fish tank of aquaponic systems and of RASs using CF and MPF. Data are presented as mean (±SD) of n = 3 independent systems per treatment. Superscript letters indicate significant differences between treatments (p < 0.05, t-test, (S) = Student t-test, assuming equal variances, (W) = Welch t-test for unequal variances). Significant p-values in the table are highlighted in bold.

4. Discussion

This study explored the use of blue mussel meal and pea protein as sustainable alternatives to conventional fish feed ingredients in aquaponic systems with Nile tilapia and Tatsoi as model organisms. Growth performance and feed utilization indices were comparable between aquaponic systems and RASs during the CF phase. Despite a better FCR in RASs (0.81± 0.04) compared to aquaponics (1.07 ± 0.14), corresponding to a 24.3% improvement, the other feed utilization and growth performance parameters were similar during the MPF phase between RASs and aquaponic systems. In the CF phase, SGR were relatively high while FCR were low. In contrast, during the MPF phase, SGR decreased while FCR increased. These changes can be attributed to the natural progression of fish size and life stage, reflecting decreased feed efficiency with age and size, as previously observed in Nile tilapia [46]. During the CF phase, fish were smaller, exhibiting higher metabolic efficiency and faster growth rates, resulting in lower FCR values. As the fish grew larger in the MPF phase, growth rates naturally declined, and maintenance energy demands increased, contributing to lower SGR and higher FCR [46,47]. Overall, the FCR values obtained in the present study fall within, and in some cases below, the lower range of values reported for Nile tilapia in both RASs and aquaponic systems. Reported FCRs in aquaponic systems typically range from 0.72 in fry [48] to 1.14–1.47 in fingerlings [49,50,51] and up to 1.60–1.62 in juvenile fish [50,52]. RAS studies report FCR as low as 0.65 in fry [48] and 1.27–1.78 in fingerlings [53]. The inclusion of pea concentrate in the diet led to FCRs of 0.90–1.06 [54]. In this context, the FCR obtained with the CF diet (0.62–0.64) can be considered particularly low and comparable to the best values reported for fry under optimized conditions, whereas the MPF treatment (0.81–1.07) falls within the lower-to-mid range reported for fingerling and juvenile Nile tilapia. Thus, the FCRs observed in this study are indicative of efficient feed utilization and are equal to or better than most values reported in comparable RASs and aquaponic production systems.

Moreover, productivity in the farming of Nile tilapia is influenced by several environmental and management factors, including temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, feeding rate, and stocking density [55,56]. Optimal growth and feed efficiency in tilapia are achieved at the upper end of their preferred temperature range (27–32 °C) [55]. The water temperature remained stable at approximately 25 °C in both aquaponic systems and RASs throughout both experimental phases, which could be considered rather low for optimal growth, although it is a compromise for the well-being of the plants as well [7].

While Nile tilapia can tolerate a broad pH spectrum, optimal growth performance and FCR are typically observed within a pH range of 6–9 [55,57]. During the CF phase, pH levels averaged around 6, whereas during the MPF phase, pH declined to approximately 5–5.5 in both systems. This is a trend commonly observed in closed systems due to ongoing nitrification and limited buffering capacity [58]. Although suboptimal pH may influence fish physiological performance, including growth, no direct correlation analysis was conducted in the present study, and other factors, such as differences in diet composition and digestibility, could have played a role and should be investigated in more detail in future studies. Nonetheless, the growth performance and feed efficiency results from this study aligned with values reported in the literature, indicating that the experimental trials were successfully conducted and that both system types provided suitable rearing conditions for Nile tilapia.

The dietary shift to an alternative protein source in the MPF phase may have further influenced nutrient digestibility and feed utilization efficiency, although these effects were not assessed in this study. Previous findings for inclusion of mussel meal in aquafeeds showed that the responses vary considerably among species, underscoring the importance of species-specific evaluations. In species such as Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar), rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), turbot (Scophthalmus spp.), and Japanese flounder (Paralichtys olivaceus), diets containing blue mussel meal at inclusion levels between 10 and 25% have proven effective in maintaining growth performance, feed acceptance, and nutritional quality [31,33,59,60,61].

Pea protein has likewise been studied as a fishmeal replacement. In Nile tilapia, up to 30% pea protein was included without compromising growth performance [54]. Similar success has been reported with 20% inclusion in Rainbow trout, Atlantic salmon, and gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) [62,63,64], while European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) tolerated replacements of up to 60% [65]. A combined diet containing 17.90% blue mussel meal and 15.50% pea protein concentrate in this study resulted in slightly lower growth performance and feed utilization compared to a conventional fishmeal- and soy protein-based diet. Nevertheless, the outcomes remain within the range of values reported in the existing literature, suggesting that these alternative ingredients hold potential as sustainable feed components for use in RASs and aquaponic systems, provided the formulation is further fine-tuned.

Plasma cortisol levels serve as a key indicator of stress in fish, as cortisol is a primary hormonal response to both acute and chronic stressors [66]. Since the fish were too small to draw blood from up until the end of the MPF phase, we could only assess this stress parameter during this phase. The mean plasma cortisol concentrations for Nile tilapia at the end of the MPF phase were 28.70 ± 21.07 ng mL−1 in aquaponic systems and 30.99 ± 11.30 ng mL−1 in RASs, which is in accordance with levels described in other studies. Basal plasma cortisol levels in tilapia range from 10 to 40 ng mL−1 [67,68,69]. Overall, cortisol concentrations in both aquaponic systems and RASs were low and did not differ significantly between system types, suggesting that the rearing environment in both systems was generally conducive to maintaining fish welfare. Nonetheless, the observed intra-system variation highlights the importance of considering individual tank conditions when evaluating fish welfare in aquaponic and RAS setups.

The relatively high, but still well within tolerable levels for Nile tilapia, NO2− levels observed in the aquaponic tanks during the MPF phase may have resulted from a temporary biofilter imbalance following the switch of diet. Since NH4+ levels remained stable during this phase, the transient accumulation likely resulted from a short-term reduction in NO2− removal rather than increased N input. However, the observed levels remained low and well within tolerable ranges for Nile tilapia [45]. There was a clear difference in NO3− accumulation between the fish rearing system types, with higher levels observed in RASs (23.6%) due to the absence of plants to absorb excess nutrients [5,70]. In aquaponic systems, plant uptake contributes to the regulation of NO3− concentrations, supporting a more balanced and sustainable nutrient environment [49]. In contrast, NO3− accumulation in RASs can reach potentially harmful levels, posing a risk to fish health, feed intake, and growth [71]. Although in the scope of this study, no such tendencies were observed.

In the present study, comparable plant yields and quality were observed in both systems during the CF phase. However, during the MPF phase, significant differences emerged, with hydroponic systems showing lower growth performance compared to the aquaponic systems, with a mean biomass accumulation of 1.29 ± 0.33 g per plant, corresponding to a 91.4% reduction in biomass accumulation relative to the aquaponic systems. This decline could be likely linked to an initial underdosing of the Hoagland solution; following its renewal after ten days, plant growth started to improve, indicating previous limitations in nutrient availability. Nutrient management in hydroponic systems can be challenging, as imbalances may arise if the chemical composition is not carefully monitored and maintained [72]. Since the nutrient solution in hydroponic systems was replaced at the start of each phase, these systems may have been more prone to instability. In contrast, aquaponic systems maintained a more stable nutrient environment, gradually building up nutrient concentrations over time. This suggests that the aquaponic system inherently provided a more consistent nutrient supply due to fish-driven nutrient input.

Furthermore, the MPF diet may have influenced nutrient availability in aquaponic systems, particularly for nutrients linked to photosynthetic performance such as N and Fe [13,73], thereby contributing to the positive responses on parameters assessed by phenotypic analyses. The improved shoot growth and SPAD indicate an enhanced photosynthetic efficiency, suggesting that the conditions in aquaponic systems with MPF can promote photosynthetic performance towards yield improvement [74]. SPAD measurements also indicated a potential to reduce leaf damage under stress conditions [75] when aquaponics is conducted using MPF as designed in the current study. Previous studies have also reported a similar positive effect of MPF on plant and fish growth and nutrient content in aquaculture [76].

The microbial quality in an aquaponic system with respect to the presence of pathogens is crucial. In the current study, the occurrence of plant pathogens related to the fungal group Oomycetes could not be detected either in aquaponic or in hydroponic systems, where the risk for their spread in hydroponic systems is high [77]. This might indicate the suppressive conditions towards pathogens related to the fungal group Oomycetes in the investigated systems. On the other hand, the conditions in aquaponic systems and RASs indicated the occurrence of pathogens related to human and fish health (Salmonella spp.) [44]. These results need further investigation and risk assessment related to food safety. However, the results obtained showed a reduction in the number of these pathogens in aquaponic systems compared with RASs and in aquaponic systems with MPF compared with CF. This might indicate the potential of cultivation conditions in aquaponic systems using MPF to suppress the occurrence and spread of these pathogens. E.coli were only detected during the CF phase in RASs, at very low concentrations [78]. The absence of detectable E. coli in the aquaponic systems suggests that environmental conditions within these systems may inhibit the presence or survival of these bacteria and warrant further investigation.

5. Conclusions

The comparable or even improved plant growth observed in aquaponic systems during the MPF phase suggests that the inclusion of blue mussel meal and pea protein in fish diets may have supported nutrient release conducive to plant uptake. These findings provide promising evidence for the use of this alternative, more sustainable aquafeed in integrated aquaponic systems.

Taken together, the findings of this study demonstrate that aquaponic systems can support both fish welfare and plant productivity when alternative protein sources such as blue mussel meal and pea protein are used in the feed. While growth performance and feed efficiency were slightly reduced in aquaponic systems compared to RASs, particularly during the MPF phase, plant growth in aquaponic systems remained stable and, in some cases, superior to that in hydroponic units. This suggests a trade-off between fish and plant performance that may be managed through careful system design and nutrient balancing. Furthermore, microbial community dynamics and stress indicators such as plasma cortisol supported the conclusion that both system types provided generally suitable rearing conditions. Nonetheless, working with small fish presents several limitations, particularly in terms of handling sensitivity and growth variation. Variability among replicates and compartments highlights the importance of system-specific monitoring, particularly during transitional phases. Future studies should explore the long-term effects of alternative feeds, the development of beneficial microbial communities, and the optimization of environmental parameters for integrated production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.B., Y.F.-A., J.A.C.R., V.T., A.C. and S.K.; Methodology, M.B., Y.F.-A., V.T., A.C., M.E.K., J.A.C.R. and S.K.; Software, V.T.; Validation, V.T., J.A.C.R., A.C. and S.K.; Formal Analysis, M.B., J.A.C.R. and V.T.; Investigation, M.B., Y.F.-A., V.T., M.E.K. and J.A.C.R.; Resources, A.C. and S.K.; Data Curation, M.B. and V.T.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.B.; Writing—Review and Editing, all authors; Visualization, M.B. and V.T.; Supervision, J.A.C.R. and S.K.; Project Administration, S.K.; Funding Acquisition, A.C. and S.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors thank Partnerskap Alnarp (https://www.slu.se/en/about-slu/organisation/collaborative-centres/slu-partnership-alnarp/, grant reference 1402/Trg/2022), Crafoord Stiftelse (www.crafoord.se, grant number 20220776), and FORMAS (grant number 2020-00867) for financial support of the project.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by the Swedish Board of Agriculture, Dnr 5.2.18-10997/2024, for the ethical use of fish and permission number 2023-11-22 6.2.18-17898/2023 for the use of greenhouse facilities for the experiment with fish.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

The staff at the Grobruket company at Alnap (www.Grobruket.se) are acknowledged for their help and advice regarding the aquaponic system. The staff at the greenhouse facilities at SLU-Alnarp are also acknowledged for their help with adjusting the cultivation conditions in the cultivation chamber.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- FAO. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2024—Blue Transformation in Action; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2024; 264p. [Google Scholar]

- Klinger, D.; Naylor, R. Searching for solutions in aquaculture: Charting a sustainable course. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2012, 37, 247–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Searchinger, T.; Waite, R.; Hanson, C.; Ranganathan, J.; Dumas, P.; Matthews, E.; Klirs, C. Creating A Sustainable Food Future: A Menu of Solutions to Feed Nearly 10 Billion People By 2050; WRI: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Goddek, S.; Joyce, A.; Kotzen, B.; Dos-Santos, M. Aquaponics and Global Food Challenges, In Aquaponics Food Production Systems: Combined Aquaculture and Hydroponic Production Technologies for the Future; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 3–17. [Google Scholar]

- Diver, S.; Rinehart, L. Aquaponics-Integration of hydroponics with aquaculture. Appropr. Technol. Transf. Rural. Areas 2010, IP163, Slot 54, Version 033010, 28p. [Google Scholar]

- Wongkiew, S.; Hu, Z.; Chandran, K.; Lee, J.W.; Khanal, S.K. Nitrogen transformations in aquaponic systems: A review. Aquac. Eng. 2017, 76, 9–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somerville, C.; Cohen, M.; Pantanella, E.; Stankus, A.; Lovatelli, A. Small-Scale Aquaponic Food Production: Integrated Fish and Plant Farming; Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2014; 288p. [Google Scholar]

- Eck, M.; Körner, O.; Jijakli, M.H. Nutrient Cycling in Aquaponics Systems. In Aquaponics Food Production Systems: Combined Aquaculture and Hydroponic Production Technologies for the Future; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 231–246. [Google Scholar]

- Van Rijn, J. Waste treatment in recirculating aquaculture systems. Aquac. Eng. 2013, 53, 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marschner, H. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Nishanth, D.; Somanathan Nair, C.; Manoharan, R.; Subramanian, R.; Salim, I.; Maqsood, S.; Jaleel, A. Current Technologies for Nutrient Recovery in Aquaponic Systems: A Review. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1681638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robaina, L.; Pirhonen, J.; Mente, E.; Sánchez, J.; Goosen, N. Fish Diets in Aquaponics. In Aquaponics Food Production Systems: Combined Aquaculture and Hydroponic Production Technologies for the Future; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 333–352. [Google Scholar]

- Kasozi, N.; Tandlich, R.; Fick, M.; Kaiser, H.; Wilhelmi, B. Iron supplementation and management in aquaponic systems: A review. Aquac. Rep. 2019, 15, 100221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddek, S.; Delaide, B.; Mankasingh, U.; Ragnarsdottir, K.V.; Jijakli, H.; Thorarinsdottir, R. Challenges of sustainable and commercial aquaponics. Sustainability 2015, 7, 4199–4224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aas, T.S.; Åsgård, T.; Ytrestøyl, T. Utilization of feed resources in the production of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) in Norway: An update for 2020. Aquac. Rep. 2022, 26, 101316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture 2020: Overcoming Water Challenges in Agriculture; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Jannathulla, R.; Rajaram, V.; Kalanjiam, R.; Ambasankar, K.; Muralidhar, M.; Dayal, J.S. Fishmeal availability in the scenarios of climate change: Inevitability of fishmeal replacement in aquafeeds and approaches for the utilization of plant protein sources. Aquac. Res. 2019, 50, 3493–3506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, D.C.; Newton, R.; Beveridge, M. Aquaculture: A rapidly growing and significant source of sustainable food? Status, transitions and potential. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2016, 75, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zlaugotne, B.; Pubule, J.; Blumberga, D. Advantages and disadvantages of using more sustainable ingredients in fish feed. Heliyon 2022, 8, e10527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agboola, J.O.; Øverland, M.; Skrede, A.; Hansen, J.Ø. Yeast as major protein-rich ingredient in aquafeeds: A review of the implications for aquaculture production. Rev. Aquac. 2021, 13, 949–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwas, N.; Vilg, J.V.; Langeland, M.; Roques, J.A.C.; Hinchcliffe, J.; Sundh, H.; Undeland, I.; Sundell, K. Marine yeast (Candida sake) cultured on herring brine side streams is a promising feed ingredient and omega-3 source for rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 2023, 571, 739448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfiko, Y.; Xie, D.; Astuti, R.T.; Wong, J.; Wang, L. Insects as a feed ingredient for fish culture: Status and trends. Aquac. Fish. 2022, 7, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biancarosa, I. Insects Reared on Seaweed as Novel Feed Ingredients for Atlantic Salmon (Salmo Salar): Investigating the Transfer of Essential Nutrients and Undesirable Substances Along the Seaweed-Insect-Fish Food Chain. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Vidakovic, A.; Langeland, M.; Sundh, H.; Sundell, K.; Olstorpe, M.; Vielma, J.; Kiessling, A.; Lundh, T. Evaluation of growth performance and intestinal barrier function in Arctic Charr (Salvelinus alpinus) fed yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae), fungi (Rhizopus oryzae) and blue mussel (Mytilus edulis). Aquac. Nutr. 2016, 22, 1348–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warwas, N.; Berdan, E.L.; Xie, X.; Jönsson, E.; Roques, J.A.C.; Doyle, D.; Langeland, M.; Hinchcliffe, J.; Pavia, H.; Sundell, K. Seaweed Fly Larvae Cultivated on Macroalgae Side Streams: A Novel Marine Protein and Omega-3 Source for Rainbow Trout. Aquac. Nutr. 2024, 2024, 4221883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidakovic, A. Fungal and Mussel Protein Sources in Fish Feed: Nutritional and Physiological Aspects. Ph.D. Thesis, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences (SLU), Uppsala, Sweden, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, J.B.E.; Sinha, R.; Strand, Å.; Söderqvist, T.; Stadmark, J.; Franzén, F.; Ingmansson, I.; Gröndahl, F.; Hasselström, L. Marine biomass for a circular blue-green bioeconomy? A life cycle perspective on closing nitrogen and phosphorus land-marine loops. J. Ind. Ecol. 2022, 26, 2136–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindahl, O.; Hart, R.; Hernroth, B.; Kollberg, S.; Loo, L.-O.; Olrog, L.; Rehnstam-Holm, A.-S.; Svensson, J.; Svensson, S.; Syversen, U. Improving marine water quality by mussel farming: A profitable solution for Swedish society. AMBIO J. Hum. Environ. 2005, 34, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusadi, D.; Aprilia, T.; Setiawati, M.; Suprayudi, M.A.; Ekasari, J. Dietary supplementation of fulvic acid for growth improvement and prevention of heavy metal accumulation in Nile tilapia fed with green mussel. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2020, 46, 295–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinchcliffe, J. Circular Economy Approach for Sustainable Feed in Swedish Aquaculture: A Nutrition and Physiology Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Azad, A.M.; Bernhard, A.; Shen, A.; Myrmel, L.S.; Lundebye, A.-K.; Lecaudey, L.A.; Fjære, E.; Ho, Q.T.; Sveier, H.; Kristiansen, K.; et al. Metabolic effects of diet containing blue mussel (Mytilus edulis) and blue mussel-fed salmon in a mouse model of obesity. Food Res. Int. 2023, 169, 112927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaeger, C.; Corraze, G.; Gayet, V.; Larroquet, L.; Surget, A.; Terrier, F.; Aubin, J. Discarded blue mussel (Mytilus edulis): A feed ingredient that maintains growth performance of juvenile gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) while fishmeal and fish oil are removed. J. Appl. Aquac. 2024, 37, 264–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagel, F.; von Danwitz, A.; Schlachter, M.; Kroeckel, S.; Wagner, C.; Schulz, C. Blue mussel meal as feed attractant in rapeseed protein-based diets for turbot (Psetta maxima L.). Aquac. Res. 2014, 45, 1964–1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, S.H. Monitoring the Photosynthetic Traits of Plants Grown under the Influence of Soil Salinity and Nutrient Stress. Ph.D Thesis, King Abdullah University of Science and Technology, Thuwal, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hoagland, D.; Arnon, D. The water-culture method for growing plants without soil. Calif. Agric. Exp. Stn. 1938, 347, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Young, G. Cortisol secretion in vitro by the interrenal of coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) during smoltification relationship with plasma thyroxine and plasma cortisol. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1986, 63, 191–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundh, H.; Calabrese, S.; Jutfelt, F.; Niklasson, L.; Olsen, R.-E.; Sundell, K. Translocation of infectious pancreatic necrosis virus across the intestinal epithelium of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar L.). Aquaculture 2011, 321, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odilbekov, F.; Armoniené, R.; Henriksson, T.; Chawade, A. Proximal phenotyping and machine learning methods to identify Septoria tritici blotch disease symptoms in wheat. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leiva, F.; Vallenback, P.; Ekblad, T.; Johansson, E.; Chawade, A. Phenocave: An automated, standalone, and affordable phenotyping system for controlled growth conditions. Plants 2021, 10, 1817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsay, E.A.; Colloff, M.J.; Gibb, N.L.; Wakelin, S.A. The abundance of microbial functional genes in grassy woodlands is influenced more by soil nutrient enrichment than by recent weed invasion or livestock exclusion. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2010, 76, 5547–5555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; Panda, P.; Ghadamgahi, F.; Barreiro, A.; Rosberg, A.K.; Karlsson, M.; Vetukuri, R.R. Microbial potential of spent mushroom compost and oyster substrate in horticulture: Diversity, function, and sustainable plant growth solutions. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 357, 120654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, Y.-J.; Deering, A.J.; Kim, H.-J. The occurrence of shiga toxin-producing E. coli in aquaponic and hydroponic systems. Horticulturae 2020, 6, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, J.; Fan, C.; Liao, X.; Chen, A.; Yang, S.; Zhao, L.; Li, H. Accurate detection of Escherichia coli O157: H7 and Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium based on the combination of next-generation sequencing and droplet digital PCR. LWT 2022, 168, 113913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karlsson, M.E.; Forsberg, G.; Rosberg, A.K.; Thaning, C.; Alsanius, B. Impact of thermal seed treatment on spermosphere microbiome, metabolome and viability of winter wheat. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 27197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atwood, H.; Fontenot, Q.; Tomasso, J.; Isely, J. Toxicity of nitrite to Nile tilapia: Effect of fish size and environmental chloride. N. Am. J. Aquac. 2001, 63, 49–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Haque, M.; Alam, M.; Flura, M. A study on the specific growth rate (SGR) at different stages of Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) production cycle in tank based aquaculture system. Int. J. Aquac. Fish. Sci. 2022, 8, 59–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainaina, M.; Opiyo, M.A.; Charo-Karisa, H.; Orina, P.; Nyonje, B. On-farm assessment of different fingerling sizes of nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) on growth performance, survival and yield. Aquac. Stud. 2022, 23, AQUAST900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.; Musdalifah, L.; Ali, M. Growth performances of Nile Tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus, reared in recirculating aquaculture and active suspension systems. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Estim, A.; Saufie, S.; Mustafa, S. Water quality remediation using aquaponics sub-systems as biological and mechanical filters in aquaculture. J. Water Process Eng. 2019, 30, 100566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Félix-Cuencas, L.; García-Trejo, J.F.; López-Tejeida, S.; León-Ramírez, J.J.d.; Soto-Zarazúa, G.M. Effect of three productive stages of tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) under hyper-intensive recirculation aquaculture system on the growth of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum). Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2021, 49, 689–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Tawaha, A.R.; Wahab, P.E.M.; Jaafar, H.B.; Zuan, A.T.K.; Hassan, M.Z. Effects of fish stocking density on water quality, growth performance of tilapia and yield of butterhead Lettuce grown in decoupled recirculation aquaponic systems. J. Ecol. Eng. 2021, 22, 8–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effendi, H.; Wahyuningsih, S.; Wardiatno, Y. The use of nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) cultivation wastewater for the production of romaine lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. var. longifolia) in water recirculation system. Appl. Water Sci. 2017, 7, 3055–3063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gullian-Klanian, M.; Arámburu-Adame, C. Performance of Nile tilapia Oreochromis niloticus fingerlings in a hyper-intensive recirculating aquaculture system with low water exchange. Lat. Am. J. Aquat. Res. 2013, 41, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulz, C.; Wickert, M.; Kijora, C.; Ogunji, J.; Rennert, B. Evaluation of pea protein isolate as alternative protein source in diets for juvenile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquac. Res. 2007, 38, 537–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mengistu, S.B.; Mulder, H.A.; Benzie, J.A.; Komen, H. A systematic literature review of the major factors causing yield gap by affecting growth, feed conversion ratio and survival in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Rev. Aquac. 2020, 12, 524–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thoa, N.P.; Ninh, N.H.; Knibb, W.; Nguyen, N.H. Does selection in a challenging environment produce Nile tilapia genotypes that can thrive in a range of production systems? Sci. Rep. 2016, 6, 21486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popma, T.; Masser, M. Tilapia Life History and Biology; Southern Regional Aquaculture Center: Stoneville, MS, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Loyless, J.C.; Malone, R.F. A sodium bicarbonate dosing methodology for pH management in freshwater-recirculating aquaculture systems. Progress. Fish-Cult. 1997, 59, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, G.M.; Austreng, E. Blue mussel in feed for rainbow trout. Aquaculture 1989, 81, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikuchi, K.; Sakaguchi, I. Blue mussel as ingredient in the diet of juvenile Japanese flounder. Fish. Sci. 1997, 63, 837–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, M.; Buck, B.H. Partial replacement of fishmeal in diets for turbot (Scophthalmus maximus, Linnaeus, 1758) culture using blue mussel (Mytilus edulis, Linneus, 1758) meat. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2017, 33, 354–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Øverland, M.; Sørensen, M.; Storebakken, T.; Penn, M.; Krogdahl, Å.; Skrede, A. Pea protein concentrate substituting fish meal or soybean meal in diets for Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar)—Effect on growth performance, nutrient digestibility, carcass composition, gut health, and physical feed quality. Aquaculture 2009, 288, 305–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, T.G.; Oliva-Teles, A. Preliminary evaluation of pea seed meal in diets for gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) juveniles. Aquac. Res. 2002, 33, 1183–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiessen, D.; Campbell, G.; Adelizi, P. Digestibility and growth performance of juvenile rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) fed with pea and canola products. Aquac. Nutr. 2003, 9, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tibaldi, E.; Tulli, F.; Messina, M.; Franchin, C.; Badini, E. Pea protein concentrate as a substitute for fish meal protein in sea bass diet. Ital. J. Anim. Sci. 2005, 4, 597–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balm, P.; Lambert, J.; Bonga, S.W. Corticosteroid biosynthesis in the interrenal cells of the teleost fish, Oreochromis mossambicus. Gen. Comp. Endocrinol. 1989, 76, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpato, G.L.; Barreto, R. Environmental blue light prevents stress in the fish Nile tilapia. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2001, 34, 1041–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E Silva, M.L.R.; Pereira, R.T.; Arvigo, A.L.; Zanuzzo, F.S.; Barreto, R.E. Effects of water flow on ventilation rate and plasma cortisol in Nile tilapia introduced into novel environment. Aquac. Rep. 2020, 18, 100531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrêa, S.A.; Fernandes, M.; Iseki, K.K.; Negrão, J.A. Effect of the establishment of dominance relationships on cortisol and other metabolic parameters in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2003, 36, 1725–1731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enduta, A.; Jusoh, A.; Ali, N.A.; Nik, W.W. Nutrient removal from aquaculture wastewater by vegetable production in aquaponics recirculation system. Desalination Water Treat. 2011, 32, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, V.C.; Limbu, P.; Martins, C.I.; Eding, E.H.; Verreth, J.A. The effect of nearly closed RAS on the feed intake and growth of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) and European eel (Anguilla anguilla). Aquac. Eng. 2015, 68, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bunyuth, Y.; Mardy, S. Hydroponic systems: An overview of benefits, challenges, and future prospects. Indones. J. Soc. Econ. Agric. Policy 2024, 1, 10–18. [Google Scholar]

- Ru, D.; Liu, J.; Hu, Z.; Zou, Y.; Jiang, L.; Cheng, X.; Lv, Z. Improvement of aquaponic performance through micro-and macro-nutrient addition. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 24, 16328–16335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaszczuk, Z.M.; Brysiewicz, A.; Kozioł, A.; Auriga, A.; Brestic, M.; Kalaji, H.M. Does fish stocking rate affect the photosynthesis of Lactuca sativa grown in an aquaponic system? J. Water Land Dev. 2023, 58, 243–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taha, M.F.; Mao, H.; Wang, Y.; ElManawy, A.I.; Elmasry, G.; Wu, L.; Memon, M.S.; Niu, Z.; Huang, T.; Qiu, Z. High-throughput analysis of leaf chlorophyll content in aquaponically grown lettuce using hyperspectral reflectance and RGB images. Plants 2024, 13, 392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasidi. Potential utilization of mussel meals as an alternative fish feed raw material for aquaculture. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1119, 012063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalil, S.; Beatrix, W.A. Effect of growing medium water content on the biological control of root pathogens in a closed soilless system. J. Hortic. Sci. Biotechnol. 2011, 86, 298–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorick, J.; Hayden, M.; Smith, M.; Blanchard, C.; Monu, E.; Wells, D.; Huang, T.-S. Evaluation of Escherichia coli and coliforms in aquaponic water for produce irrigation. Food Microbiol. 2021, 99, 103801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.