Abstract

The comprehensive evaluation of factors that increase the difficulty of autonomous driving in various complex traffic situations and diverse roadway geometries within living lab environments is of great interest, particularly in developing sustainable urban mobility systems. This study introduces a novel methodology for assessing autonomous driving vulnerabilities and identifying urban traffic segments susceptible to autonomous driving risks in mixed traffic situations where autonomous and manual vehicles coexist. A microscopic traffic simulation network that realistically represents conditions in a living lab demonstration area was used, and twelve safety indicators capturing longitudinal safety and vehicle interaction dynamics were employed to compute an integrated risk score (IRS). The promising weighting of each indicator was derived through decision tree method calibrated with real-world traffic accident data, allowing precise localization of vulnerability hotspots for autonomous driving. The analysis results indicate that an IRS-based hotspot was identified at an unsignalized intersection, with an IRS value of 0.845. In addition, analytical results were examined comprehensively from multiple perspectives to develop actionable improvement strategies that contribute to long-term sustainability, encompassing roadway and traffic facility enhancements, provision of infrastructure guidance information, autonomous vehicle route planning, and enforcement measures. Furthermore, this study categorized and analyzed the characteristics of high-risk road sections with similar geometric features to systematically derive effective traffic safety countermeasures. This research offers a systematic, practical framework for safety evaluation in autonomous driving living labs, delivering actionable guidelines to support infrastructure planning and validate sustainable autonomous mobility.

1. Introduction

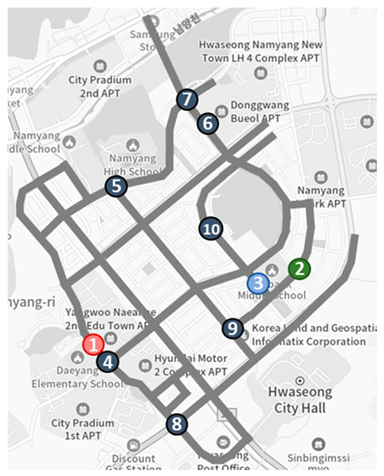

Autonomous vehicles (AVs) are emerging as a future transportation technology that can reduce traffic accidents caused by human factors such as perception and decision-making errors, or inadequate driving performance. According to the U.S. National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), approximately 41% of all accidents are caused by human factors, 34% of which are due to driver decision errors, and 10% are due to poor driving performance [1]. To address these issues, AVs are equipped with AI-based decision-making systems, sensing technology, vehicle-to-vehicle and vehicle-to-infrastructure communication systems, enabling real-time perception and decision making in dynamic traffic environments. Autonomous driving technology is advancing in a direction that verifies it with transportation systems and infrastructure in urban areas. The development of autonomous driving technology has increasingly focused on verification within actual urban transportation systems and infrastructure. Accordingly, autonomous driving living labs have been established and operated to test autonomous driving technologies in real urban settings and to evaluate aspects such as traffic safety and social acceptability. A living laboratory denotes an open testbed environment designed to facilitate systematic demonstrations and validations of autonomous driving technologies, supporting infrastructure, and associated services. It is implemented within real-world settings that are actively inhabited by the general public. It further serves as a platform enabling citizens to directly experience autonomous-driving services, thereby facilitating empirical evaluation under authentic operational and behavioral conditions [2]. In the Republic of Korea, living labs for autonomous driving are currently operating in Seoul and Sejong, while Namyang-eup and Saesol-dong in Hwaseong have recently been designated as new autonomous driving living lab areas. The Hwaseong living lab area includes diverse roadway geometries such as roundabouts, signalized intersections, and arterial roads, where AVs and manual vehicles (MVs) coexist. In mixed traffic situations, it is necessary to identify autonomous driving vulnerable segments by analyzing the AV driving data collected from the testing zone and to propose improvements for road traffic infrastructure. The purpose of this study is to identify autonomous driving vulnerable segments within the Hwaseong autonomous driving living lab demonstration zone, where various services and technologies have been tested, and to suggest potential issues and improvement measures for these vulnerable segments.

This study selected the autonomous driving living lab demonstration zone in Hwaseong as the analysis segment and established a simulation network with the traffic simulation software VISSIM 2024. To ensure realism in the simulation network, roadway elements such as on-street parking areas and bus stops were implemented. The analysis was conducted by dividing the roadway into segments such as bus stop influence zones and intersection influence zones. Longitudinal maneuvering and vehicle interaction safety evaluation indicators were selected and computed using simulation data. This study advanced the road infrastructure safety assessment methodology proposed in existing studies [3]. The safety penalty (SP) was computed by applying min-max normalization to the values of the evaluation indicators derived for each segment. The integrated risk score (IRS), a comprehensive indicator, was computed by applying weights to the normalized SP values of the individual evaluation indicators. Evaluation indicators were selected based on accident data, with the analysis area classified into three distinct groups according to accident frequency: segments with no reported accidents, segments with below-average accident frequency, and segments with above-average accident frequency. The relative amount of information gains derived from decision tree analysis was used to compute the weights. This study analyzed the autonomous driving vulnerability within the living lab based on the IRS, presenting the risk level of roads and identifying autonomous driving vulnerable segments. Furthermore, the study examined the road characteristics of these segments to identify existing issues and propose appropriate improvement measures. The improvement measures were proposed across four aspects: road and traffic facilities, infrastructure guidance, autonomous vehicle route design, and enforcement. The results of this study are expected to support the development of comprehensive guidelines for safe autonomous driving, specifically addressing road infrastructure facilities and traffic management practices.

The structure of this study is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews existing studies that analyzed safety in mixed traffic situations and suggests implications relevant to this research. Section 3 presents a methodology for analyzing autonomous driving vulnerability through simulation-based analysis to identify autonomous driving vulnerable segments. Section 4 identifies these vulnerable segments within the autonomous driving living lab and discusses the issues and improvement measures for these segments. The Section 5 presents the conclusions of this study and suggests directions for future research.

2. Literature Review

This study aims to identify autonomous driving vulnerable segments through simulation-based analysis and to present the issues and improvement measures associated with these segments. In this context, prior research was reviewed, including studies that evaluated autonomous vehicle safety through traffic simulations and those that developed and applied methodologies for assessing road infrastructure safety. The distinctiveness of this study compared to existing relevant studies was also presented.

First, the existing studies that evaluated the safety of AVs using traffic simulations were reviewed. Xu et al. [4] developed a framework to verify the safety performance of connected autonomous vehicles based on co-simulation. They applied a Bayesian hierarchical model to analyze accident occurrence patterns and identified conditions under which AV safety became vulnerable. The safety evaluation indicators were selected as post-encroachment time (PET) and time to collision (TTC). Garbaire et al. [5] utilized driving data collected from 20 AVs operating in California to identify the factors influencing AV conflicts on roads and intersections based on Capula. The number of conflicts per hour and the number of severe conflicts per hour were selected as safety indicators for the evaluation. Alozi et al. [6] developed a machine learning-based conflict prediction model using driving data collected from AVs operating in six regions of United States. The study presented the driving time and number of conflicts for each AV in each region, using TTC as the evaluation indicator for conflict prediction and safety assessment. Ortiz et al. [7] identified high-risk events by analyzing TTC, driving behavior, and driving direction based on real-world data collected from AVs operating in multiple cities. Time to collision with motion orientation, called TTCmo, was used to identify high-risk events and conflicts. Deluka Tibljaš, A. et al. [8] evaluated the safety of roundabouts in mixed traffic situations depending on the market penetration rate (MPR) of AVs. Conflict analysis was performed using VISSIM and SSAM. Safety evaluation indicators such as speed, spacing, TTC, and PET were selected to assess how indicator values changed based on the MPR.

The existing studies that developed and applied road infrastructure safety assessment methodologies and those that derived integrated evaluation indicators for safety assessment were reviewed. Gu et al. [3] analyzed vulnerable segments for driving safety by developing an integrated evaluation indicator through simulation-based safety assessment that considered road alignment and facilities. The behavior of MVs following AVs, collected through driving simulations, was applied to traffic simulations. The integrated evaluation indicator was derived by applying the road infrastructure safety assessment methodologies developed in existing studies. Lee et al. [9] evaluated the safety of mixed traffic situations in urban environments using VISSIM. The driving safety evaluation indicators were selected as conflict-related and individual safety evaluation indicators. These indicators were normalized through the min–max normalization method to compute an integrated evaluation indicator. The integrated evaluation indicator was derived by computing the simple average of the normalized individual evaluation indicators, and safety assessments were conducted based on both the individual and the integrated evaluation indicators.

Research related to traffic safety in mixed traffic situations using simulations has been continuously conducted, with most studies focusing on safety analysis based on selected specific evaluation indicators [4,5,6,8]. However, the rationale for selecting these indicators remains insufficient. In addition, there have been many existing studies deriving the influencing factors of AV accidents or identifying accident occurrence patterns [3,9]. However, research that analyzed the causes and influencing factors of autonomous driving vulnerabilities while proposing improvement measures was few. Therefore, this study developed an integrated evaluation indicator using longitudinal and interaction safety evaluation indicators to effectively assess the safety of mixed traffic situations. Unlike the existing studies, this study focused on urban roads as the analysis area. While this study aligns with previous research in its overall direction [3,9], it distinguishes itself by employing actual urban crash data to derive the integrated evaluation indicator. In preceding studies, the indicators were selected based on crash data obtained from freeway environments and representative measures were subsequently applied in urban analyses. In contrast, this study utilized crash data from urban areas to select the evaluation indicators incorporated into the integrated risk index. Furthermore, this study analyzed the road characteristics of segments with high autonomous driving vulnerability and proposed improvement measures from various aspects.

3. Methodology

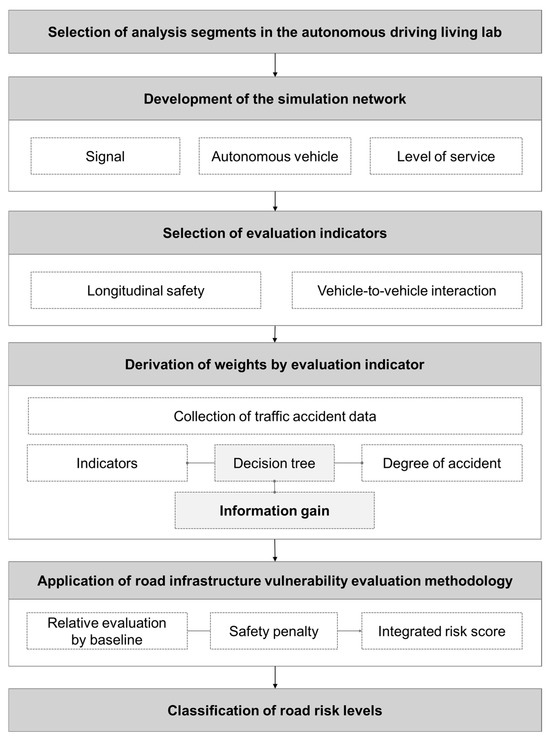

This study analyzed the autonomous driving vulnerability of an autonomous driving living lab through simulation, and the overall research procedure is presented in Figure 1. First, the autonomous driving living lab is selected as the analysis area, and a simulation network is established. The simulation implemented real-world conditions, such as signal timing and the number of operating AVs. During the selection process of evaluation indicators, candidate measures for assessing autonomous driving vulnerability are identified based on the traffic simulation. The indicators used to compute the integrated evaluation indicator are selected through decision tree analysis, and weights are derived from information gain. The integrated evaluation indicator is computed by applying the road infrastructure safety assessment methodology proposed in existing studies and incorporating the derived weights. In the final step, the autonomous driving vulnerable segments are identified based on the integrated evaluation indicator, and the issues and improvement measures for these segments are presented.

Figure 1.

Overall research procedure.

3.1. Simulation Network and Experiments

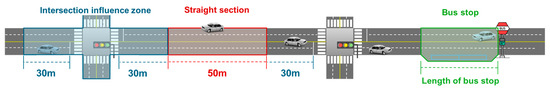

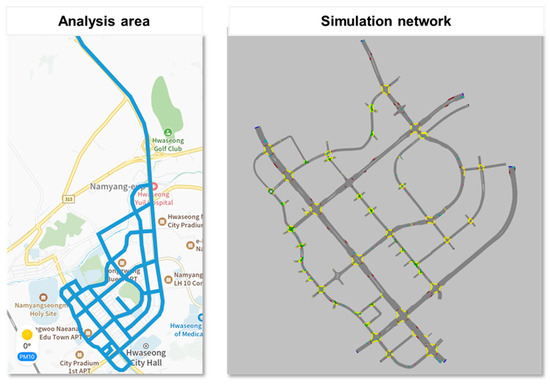

This study selected the demonstration zone of the autonomous driving living lab as the analysis area. The total length of the network was approximately 35.02 km, consisting of diverse geometries such as four-way intersections, three-way intersections, roundabouts, and unsignalized intersections. The analysis area was established using VISSIM, a microscopic traffic simulation tool that enables the implementation of realistic roadway conditions, including geometric layouts and roadside facilities. In addition, it allows for the reproduction of autonomous vehicle behavior, thereby facilitating its incorporation into simulated traffic environments. This study adopted VISSIM as the primary simulation tool due to its capability to construct scenarios considering various levels of traffic conditions and autonomous driving functions. When establishing the network, the area was divided into 254 segments based on categories such as intersection influence zones, straight sections, and bus stop influence zones. A conceptual diagram of the segment classification is presented in Figure 2. The intersection influence zone was defined as extending from 30 m before the stop line at an intersection to 30 m beyond the intersection exit [10]. Straight sections were set at 50 m, and bus stop influence zones were defined according to the length of the bus stop area or bus bay [9,11]. Signal timings within the network were applied using real-world signal data. Traffic volume was set to level of service (LOS) between A and B, ensuring that the behavioral differences between AVs and MVs were clearly distinguishable. The behavior of AVs was set to the ‘aggressive’ driving mode from CoExist, which had short spacing and high acceleration [12,13,14,15]. This mode was selected as the AV driving logic in the simulation due to its high infrastructure communication capability, short perception and reaction times, similarity to Level 4 autonomous driving, and ability to clearly distinguish the behavior between AV and MV. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE), a U.S.-based international organization, defined six levels of driving automation ranging from Level 0 to Level 5: no automation (Level 0), driver assistance (Level 1), partial automation (Level 2), conditional automation (Level 3), high automation (Level 4), and full automation (Level 5) [15]. The Hwaseong autonomous driving living lab has been designed as an environment capable of comprehensively demonstrating technologies, infrastructure, and services associated with Level 4 vehicle automation. Accordingly, this study focuses on Level 4 automation, which corresponds to the operational conditions and technological advancement of the living lab environment [2].

Figure 2.

Segment classification of analysis area.

The number of AVs in the simulation was set to 80, matching the number of AVs to be demonstrated in the actual living lab. The simulation was conducted with a 30-min warm-up period and a 1-h simulation time, with a total of 10 runs performed. The analysis area and VISSIM simulation network are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Analysis area and simulation network.

3.2. Selection of Evaluation Indicator

The evaluation indicators were selected as driving safety evaluation indicators that could be computed from simulation results including speed, acceleration, vehicle length, and spacing. These are presented in Table 1. The selected indicators consisted of speed standard deviation, speed-based time varying volatility (VF speed), average acceleration, acceleration standard deviation, acceleration-based time varying volatility (VF acc), average time to collision (TTC), average deceleration rate to avoid a crash (DRAC), average crash potential index (CPI), spacing standard deviation, average headway, headway standard deviation, and headway-based time varying volatility (VF headway) [9,16,17,18,19,20]. A total of 12 driving safety evaluation indicators were selected: 5 longitudinal safety indicators for AVs and 7 interaction indicators. The analysis area, urban roads, frequently experiences stop-and-go conditions, so data recorded during stopped states were excluded from the analysis. Each evaluation indicator was computed for all 254 segments.

Table 1.

Candidates driving safety indicators.

3.3. Selection of Evaluation Indicator Priorities and Derivation of Weights

This study defines segments where accidents are likely to occur during AV operation as autonomous driving vulnerable segments and presents the risk level of roads based on autonomous driving vulnerability for the analyzed area. Prior to identifying the autonomous driving vulnerable segments, evaluation indicators that clearly identify autonomous driving vulnerability were selected. A decision tree analysis was performed to select indicators, derived from simulation results, that effectively represent segments where actual accidents occurred. The input variables were the evaluation indicators derived from simulations, and the output variable was set as actual accident segments. The accident segments defined as the output variable were determined using real accident data of MV. This approach was adopted because AV operation remained in the pilot phase, resulting in limited availability of accident data. According to California autonomous vehicle accident reports, accident-prone segments for AVs—such as signalized intersections, unsignalized intersections, and merge zones—corresponded closely to those where MV accidents frequently occurred. Therefore, this study assumed that segments where MV accidents occurred represented segments with a high risk of AV accidents [21,22].

A decision tree is one of the algorithms classified under supervised learning in machine learning. It refers to a method of classifying or predicting data by diagramming decision rules based on specific criteria into a tree structure. The decision tree model is a nonparametric method that does not require assumptions such as linearity, normality, or homoscedasticity [23]. It is intuitively easy to understand and presents key variables and separation criteria, which makes the interpretation of results straightforward. It is also commonly used when identifying which explanatory variable has the most significant influence [24]. In forming the decision tree structure, determining the input variables and classification points is critical. These variables and points are selected to maximize the value obtained by subtracting the sum of the impurities of the child nodes from the impurity of the parent node. Furthermore, optimal parameters, namely hyperparameters, are set to prevent overfitting and to ensure the selection of an appropriately sized tree.

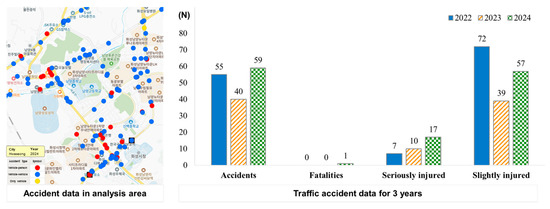

The decision tree model was employed to determine the weights of evaluation indicators, with the entropy index serving as the objective function for selecting separation criteria during classification. Variable selection was guided by information gain represented by Equation (1), calculated from the entropy representing information uncertainty, thereby quantifying each variable’s relative contribution to data classification [25]. The computed information gain for each indicator was then applied as its weight when deriving the integrated evaluation indicator. The decision tree model was established by setting simulation-based driving safety evaluation indicators as input variables and real-world accident data from the analysis area as output variables. The accident data were collected from the Traffic Accident Analysis System. Multiple scenarios were developed by varying the temporal span of the accident dataset and the number of classification levels for accident frequency, enabling the identification of the optimal utilization of crash data. Among these scenarios, the model using three years of accident data categorized into three classes showed the best performance in terms of accuracy, recall, and precision. The decision tree analysis results for all data scenarios are summarized in Table 2. Accordingly, a total of 154 accident cases recorded between 2022 and 2024 were analyzed for the Hwaseong Autonomous Driving Living Lab. During this period, one fatal accident occurred in 2024, along with several cases involving severe and minor injuries. A summary of these data is presented in Figure 4. Road segments with accidents that occurred were divided into three classes, as identified from the optimal classification categories: segments with no accidents, segments with below-average accident frequency, and segments with above-average accident frequency. Over the three-year period, 154 accidents occurred across 60 segments, yielding an average of 2.57 crashes per segment. Therefore, the classification criteria were defined as segments with no accidents, segments with 2 or fewer accidents, and segments with 3 or more accidents.

where

Table 2.

Results of the decision tree analysis by data scenarios.

Figure 4.

Spatial distribution and summary of traffic accidents.

- : Prior entropy.

- : Post-event entropy.

- : Child node.

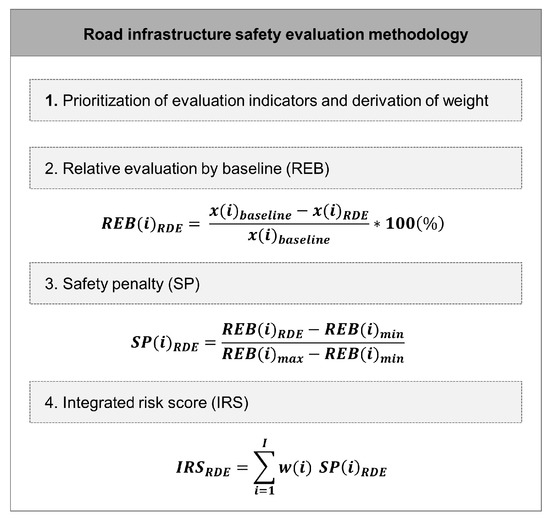

3.4. Development of a Methodology for Evaluating Road Infrastructure Safety

This study adopted and further developed the road infrastructure safety assessment methodology proposed in existing study [3]. The framework for road infrastructure safety assessment is presented in Figure 5. The existing study selected freeways as the analysis area and categorized road design elements such as connectors, longitudinal gradients, and slopes for analysis. It also utilized accident data from individual C-ITS vehicles operating on freeways to prioritize evaluation indicators, derive indicator weights, and compute an integrated evaluation indicator. In contrast, this study focused on urban roads and conducted the analysis by dividing the actual roads of the autonomous driving living lab in Hwaseong into segments such as intersection influence zones and bus stop influence zones. The accident data used for evaluation indicator selection and weight derivation in the integrated evaluation indicator computation were appropriately modified since individual C-ITS vehicles have different behavioral characteristics from AVs in urban areas. Furthermore, this study not only identified autonomous driving vulnerable segments but also proposed improvement measures from multiple aspects.

Figure 5.

Methodology for analyzing autonomous driving vulnerability.

The first step involved prioritizing the evaluation indicators and deriving weight for each indicator through decision tree analysis. The second step, REB, was a process to evaluate the autonomous driving vulnerability of road infrastructure through simulation-based analysis. Existing methodologies classified road segments according to geometry and facility characteristics, and a baseline section-a flat, straight road-was designated to compare the relative safety of segments. In contrast, this study compared evaluation indicators for segments categorized not by road geometry but by real-world segments where AVs were tested, such as intersection influence zones and bus stop influence zones. The REB computation for each evaluation indicator is presented in Equation (2).

where

- : REB values of evaluation indicator by road design element.

- : Road design element.

- : Values of evaluation indicator on straight sections.

- : Values of evaluation indicator by road design element.

- : Evaluation indicator ( = 1, 2, ⋯, n).

The third step was to normalize the evaluation indicators. Because the ranges of REB values differed across indicators, direct comparison was infeasible. To address this, each evaluation indicator was normalized using a consistent standard, enabling meaningful comparison across indicators. The min-max normalized values of each evaluation indicator, ranging from 0 to 1, were defined as the safety vulnerability score, SP. The SP for each indicator and segment was computed as shown in Equation (3).

where

- : Normalized values of evaluation indicator by road design element.

- : REB values of evaluation indicator by road design element.

- : Maximum values of evaluation indicator by road design element.

- : Minimum values of evaluation indicator by road design element.

The fourth step was the computation of IRS. It was computed by multiplying the weights derived for each evaluation indicator from the decision tree analysis with the SP derived in the second step, as shown in Equation (4).

where

- : Weight of evaluation indicator .

- : Normalized values of evaluation indicator by road design element.

This study complemented existing methodologies to make it suitable for urban environments and derived individual evaluation indicators and their corresponding weights for computing the IRS. A machine learning-based classification model using a decision tree was applied to assign weights according to the relative importance among driving safety indicators. This study labeled each segment as either above-average accident, below-average accident, or no-accident segments based on the traffic accident frequency within the analysis area. The information gain, representing the influence that each variable has on the occurrence of traffic accidents, was then computed. The REB and SP were utilized as evaluation indicators and their corresponding weights, respectively, when computing the IRS.

4. Results

4.1. Derivation of Weights for Evaluation Indicators Based on Decision Tree

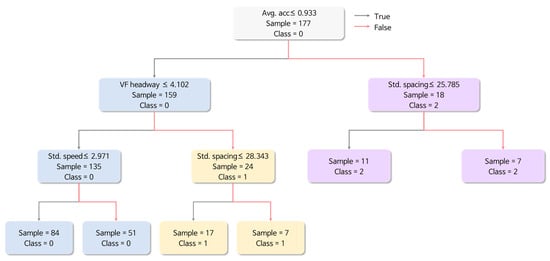

The IRS presented in this study was computed by multiplying the weights of individual evaluation indicators derived from decision tree analysis by the normalized indicators. Among the 254 segments, 194 segments had no accidents, 50 segments experienced below-average accident frequency, and 10 segments experienced above-average accident frequency. For the 254 segments, the dataset was divided into training and testing sets at a ratio of 7:3, and decision tree analysis was performed after hyperparameter tuning to derive the weights for individual evaluation indicators. The classification accuracy of the decision tree optimization model was derived as 72.73%, recall as 75.32%, and precision as 73.75%. The confusion matrix and information gain are presented in Table 3. In the confusion matrix, ‘non-occur’ indicates segments with no recorded accidents, ‘occur’ corresponds to segments with accident frequencies below the average, and ‘multi-occur’ denotes segments with accident frequencies above the average. The model correctly classified 53 non-accident segments as non-occur and 4 below-average segments as occur. A total of four evaluation indicators were used to compute the IRS: average acceleration, VF headway, standard deviation of spacing, and standard deviation of speed. The information gains were derived in the order of 0.698, 0.137, 0.084, and 0.082. These information gains were used as weights to compute the IRS. The results of the decision tree model are shown in Figure 6. Segments where the average acceleration exceeded 0.933 were interpreted as accident-prone segments where three or more accidents occurred. The proposed decision tree model reveals that the decision thresholds correspond to distinct patterns of crash occurrence, as shown in Figure 6. Specifically, when the average acceleration of vehicles exceeds 0.933, the model classifies the segment as one associated with high crash frequency. Conversely, when the average acceleration is below 0.933, and the time-varying volatility of headway exceeds 4.102, the segment corresponds to an average crash frequency group. These outcomes demonstrate that average acceleration exhibits the highest level of explanatory importance in the model, followed by VF-based headway volatility as the next most influential factor. Table 4 summarizes the statistical results obtained from ten repeated simulations for each of the four evaluation indicators. The mean average acceleration across the ten runs was 0.242, with a standard deviation of 0.006. Similarly, the VF headway showed a mean of 4.083 and a standard deviation of 0.055. These findings demonstrate a high level of consistency across the repeated simulations, indicating minimal variability in the outcomes.

Table 3.

Results of decision tree analysis with accident data.

Figure 6.

Decision tree model.

Table 4.

Statistical results of ten simulation iterations for the key variables.

4.2. Analysis of the Risk Level of Roads Based on Individual Evaluation Indicators

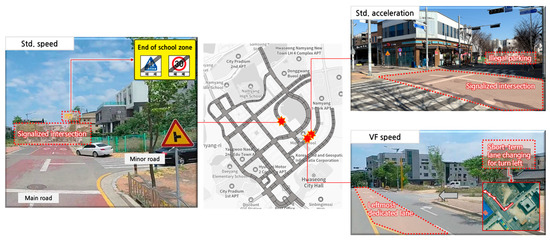

The segments where autonomous driving was most vulnerable based on individual evaluation indicators are presented in Figure 7. The issues identified in the segments with the highest vulnerability for each individual evaluation indicator were analyzed, and improvement measures were proposed from four aspects: road and traffic facilities, infrastructure guidance, autonomous vehicle route design, and enforcement. First, the segment with the highest vulnerability based on speed standard deviation was the one where child and senior protection zones ended, resulting in a change in the speed limit from 30 km/h to 50 km/h. Rapid acceleration might occur, and stopping at a downstream signalized intersection due to a red light could increase speed standard deviation immediately after this limit change. Additionally, this segment lay between a three-way intersection and a four-way signalized intersection, with a short distance between them. Rapid lane changes may occur upstream of the signalized intersection as drivers attempt to enter the dedicated left-turn lane. To enhance autonomous vehicle driving safety from the perspective of road and traffic facilities, improvements in intersection operation and speed limit management strategies are needed. In addition, monitoring left-turn traffic volumes is essential for optimizing signal operation systems to better accommodate real-time traffic flow. From the enforcement perspective, regulating illegally parked vehicles and other factors that block the recognition of road markings by autonomous vehicles is essential to reducing autonomous driving vulnerability.

Figure 7.

Road sections identified as having the highest autonomous driving vulnerability by indicators.

The segment where autonomous driving was vulnerable based on acceleration standard deviation was signalized intersections with narrow intersection areas and the absence of left-turn guidelines. In these segments, the speed limit was set at 50 km/h on the main road and 30 km/h on the side road, making rapid deceleration during left turns when the left-turn green signal was active. In addition, the side roads lacked centerline, increasing the potential for conflicts when vehicles from the main road entered the side road. From the perspective of road and traffic facilities, installing left-turn guidelines could enhance the safety of AVs turning left. It is necessary to provide information regarding speed limit changes to induce vehicles deceleration from the infrastructure guidance perspective. Furthermore, providing both main road and side road vehicles with information regarding the presence of entering vehicles and guidance on turning radius adjustments could prevent conflicts.

The segment where autonomous driving was identified as vulnerable based on VF speed was the one where vehicles could merge from a minor road onto a main road and where a dedicated left-turn lane was present. This highlights the issue that, when vehicles enter the main road from a minor road intending to turn left, the distance available for required lane changes is often insufficient. Therefore, the autonomous driving vulnerability can be improved by not providing information about the left-turn path during autonomous vehicle route design.

4.3. Risk Level Assessment of Road Segments Based on Integrated Risk Score (IRS)

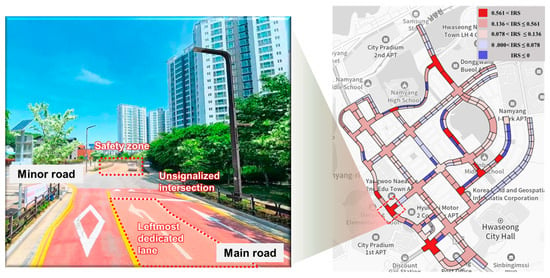

The IRS computed using weights derived from the decision tree and the IRS-based risk level visualization is shown in Figure 8. Risk levels of road were classified into five grades: Top 5%, 35%, 65%, 95%, and 100%. Among all segments, the segments with high risk levels were identified as signalized intersections, unsignalized intersections, and the upstream areas of intersections. Issues were identified for segments with high risk levels, and improvement measures were proposed across four aspects: road and traffic facilities, infrastructure guidance, autonomous vehicle route design, and enforcement. The segment with the highest risk level was the unsignalized intersection within the school zone. This segment not only had the possibility of conflicts between vehicles on the main and side roads but also severe accidents involving child pedestrians. Furthermore, the presence of both a dedicated left-turn lane and a straight-through lane required lane changes depending on the vehicle’s approach direction. When vehicles enter the main road from a minor road to turn left, driving within the road safety zone is prohibited under current law. Therefore, this segment requires careful consideration of lane usage and turning radius to ensure legal compliance and safe maneuvering. To improve safety within school zones, the installation of raised crosswalks is recommended as a measure to reduce accident frequency and severity. In addition, the dedicated left-turn lane could be operated flexibly as a straight-through lane depending on traffic volume, and left-turn guidelines should be established to prevent unauthorized entry into the road safety zone. Regulatory enforcement measures, such as controlling illegal parking, are essential for ensuring clear visibility and safe autonomous vehicle local path planning. Furthermore, infrastructure improvements can be supported by providing guidance on right-of-way and implementing automatic speed limit adjustments during school commute times, utilizing real-time traffic data. The geometry and IRS values for the top 10 segments based on IRS are presented in Table 5. All top 10 high-risk segments were classified as unsignalized or signalized intersections, indicating that intersections in general are autonomous driving vulnerable segments. Accordingly, the risk levels by road geometry were presented to derive the characteristics of autonomous driving vulnerable segments for each geometry.

Figure 8.

Level of IRS and highest vulnerable segment.

Table 5.

Top 10 segments vulnerable to autonomous driving based on IRS.

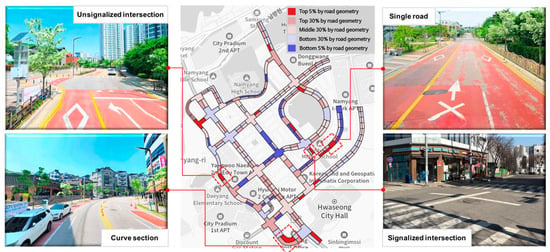

The IRS-based risk levels of roads were classified into five grades to assess risk by road geometry. Road geometry was categorized into four types: signalized intersections, unsignalized intersections, curve sections, and single roads. The number of segments per geometry, the proportion of each geometry within the total of 254 segments, highest IRS, and average of IRS are presented in Table 6. Signalized intersections had 22 segments, accounting for approximately 8.66% of all segments. The highest IRS value for a signalized intersection was derived as 0.793. Unsignalized intersections also had 22 segments, with the IRS of 0.845, the highest value among all geometry. The average IRS values by road geometry are highest in the order of signalized intersections, unsignalized intersections, single roads, and curved sections. Therefore, the results show that autonomous driving is most vulnerable at signalized intersections compared to other road geometry.

Table 6.

Number of segments and IRS by road geometry.

The visualization of each road geometry according to five risk levels and the most vulnerable segments is presented in Figure 9. The signalized intersection identified as most vulnerable to autonomous driving matched the segment previously identified based on the standard deviation of acceleration. Similarly, the segment with the highest vulnerability at unsignalized intersections corresponded to the result from the IRS-based vulnerability analysis. Among curve sections, the segment with the highest vulnerability at unsignalized intersections corresponded to the result from the IRS-based vulnerability analysis. The far-right lane in this segment was used as on-street parking. This segment had fewer lanes and frequent vehicle merging due to the on-street parking compared to other curved sections. Therefore, it is necessary to ensure lane availability and reduce traffic congestion through enforcement of illegal parking regulations. For single roads, the most vulnerable segment was found near daycare centers and middle schools, located between signalized intersections. This segment had a dedicated left-turn lane, requiring mandatory lane change when turning left. Vehicles were permitted to cross the center line for parking on the opposite side. Compared to other single roads, this segment often has lower speed limits and frequent stops and starts caused by signalized intersections. Therefore, it is necessary to evaluate the signal operation system to minimize delays due to low-speed driving or signal-induced stops. Additionally, the installation of delineator posts, in addition to centerline pavement markings, is installed to prevent centerline encroachment.

Figure 9.

Segments exhibiting highest risk by roadway geometry.

5. Conclusions

Evaluating autonomous driving vulnerability is crucial in living labs where advanced technologies and public services are demonstrated. It is particularly necessary to proactively identify the autonomous driving vulnerable segments and propose improvement measures within the demonstration zone where there are various geometries and services. This study developed a road infrastructure safety assessment methodology to analyze autonomous driving vulnerabilities in mixed traffic situations. Autonomous driving vulnerable segments were identified based on individual evaluation indicators and IRS. A realistic simulation network was established to accurately represent the analysis area, and traffic conditions were set to differentiate the behavior of AVs and MVs. 12 evaluation indicators were selected to assess longitudinal and interaction safety based on the simulation results. Normalization and IRS were computed using the road infrastructure safety evaluation methodology. The IRS was computed through the decision tree-based information gain derived from actual traffic accident data. Autonomous driving vulnerability was high at unsignalized intersections, particularly in areas requiring low-speed driving like school zones. Improvement measures were proposed across four aspects: road and traffic facilities, infrastructure guidance, enforcement, autonomous vehicle path design, by analyzing the characteristics of vulnerable segments based on individual evaluation indicators and IRS in Table 7. This study is significant in that it proposes an autonomous driving vulnerability analysis framework specifically suited for living lab demonstration environments and suggests improvement measures for each identified vulnerable segment. Based on these contributions, the findings are expected to serve as practical guidelines for establishing autonomous driving infrastructure and implementing technology demonstrations, ultimately enhancing operational safety. Moreover, by supporting data-driven decision making for risk-mitigating interventions, the outcomes of this research can facilitate the realization of sustainable smart cities in which autonomous driving systems operate more safely and efficiently, ultimately leading to a reduction in collision risks and improved urban mobility performance.

Table 7.

Example of improvement measure for vulnerable segments.

Future research is required to advance this study. First, it is necessary to consider various levels of autonomous driving behavior. This study modeled AVs with aggressive driving settings, but it is required to set behavior levels considering situations where various levels of autonomous driving technology coexist. Second, further investigation under various traffic conditions is required. This study focused on relatively light conditions corresponding to LOS A–B; therefore, extending the analysis to congested states such as LOS C or LOS D would help determine whether vulnerability patterns shift with increasing congestion and the extent of such changes. Third, refinement of segment influence zones is necessary. Although influence areas were defined as 30 m for intersections and 50 m for mid-block segments, urban road networks exhibit diverse geometric conditions. Future research should therefore define and analyze influence zones in more diverse ways to better capture segment-specific roadway characteristics. Fourth, implementation of road users such as pedestrians and cyclists is needed. This study implemented only AVs and MVs in the simulation; accordingly, future analyses should address interactions with a broader range of road users, including pedestrians, cyclists, and personal mobility (PM) users. Fifth, it is necessary to incorporate disturbance factors into the decision tree-based weight calibration, such as introducing noise into input features or label data. Assessing the robustness of the decision-tree model under perturbed conditions—by examining variations in classification structure, performance indices, and accuracy metrics—would provide meaningful insights into its stability against disturbances. Sixth, it would be worthwhile to evaluate whether applying control-based approaches—such as the “Dual Control for Exploitation and Exploration (DCEE)” or the “Nesterov Accelerated Gradient Descent (NAGD)-based DCEE” to the framework proposed in this study yields improved performance. Finally, vulnerability analysis should be extended to encompass atypical or complex traffic scenarios, such as construction zones and unexpected events. Enhancing safety under such challenging conditions is essential for the commercialization of autonomous driving.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.K. and C.O.; data curation, M.K.; methodology, M.K. and C.O.; analysis, M.K. and H.J.; visualization, M.K.; writing—original draft, M.K. and H.J.; Writing—review and editing, C.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Korea Agency for Infrastructure Technology Advancement (KAIA) grant funded by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (Grant RS-2021-KA160881, Future Road Design and Testing for Connected and Autonomous Vehicles).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset available upon request from the authors.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| AV | Autonomous vehicle |

| MV | Manual vehicle |

| PET | Post-encroachment time |

| TTC | Time to collision |

| VF | Time varying volatility |

| DRAC | Deceleration rate to avoid crash |

| CPI | Crash potential index |

| REB | Relative evaluation by baseline |

| RDE | Road design element |

| SP | Safety Penalty |

| IRS | Integrated risk score |

References

- National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey: Report to Congress; U.S. Department of Transportation: Washington, DC, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- ITS Korea, ITS Koea Notice: [Press Release] Autonomous Driving Living Lab Construction Project Briefing Session Held. 2024. Available online: https://itskorea.kr/boardDetail.do?type=7&idx=15158¤tPage=1&searchType=&searchText= (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Gu, Y.; Jo, Y.; Oh, C.; Park, J.; Yun, D. Evaluating road infrastructure safety in mixed traffic conditions of autonomous mobility and manual vehicles: A comprehensive simulation approach. J. Korean Soc. Transp. 2024, 42, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Zheng, N. Safety validation for connected autonomous vehicles using large-scale testing tracks in high-fidelity simulation environment. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 215, 108011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gabaire, M.; Ghomi, H.; Hussein, M. Investigating the contributing factors to autonomous vehicle–road user conflicts: A data-driven approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 211, 107898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alozi, A.R.; Hussein, M. Enhancing autonomous vehicle hyperawareness in busy traffic environments: A machine learning approach. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2024, 198, 107458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ortiz, F.M.; Sammarco, M.; Detyniecki, M.; Costa, L.H.M. Road traffic safety assessment in self-driving vehicles based on time-to-collision with motion orientation. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2023, 191, 107172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deluka Tibljaš, A.; Giuffrè, T.; Surdonja, S.; Trubia, S. Introduction of autonomous vehicles: Roundabouts design and safety performance evaluation. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Jo, Y.; Jung, A.; Park, J.; Oh, C. Evaluation of automated driving safety in urban mixed traffic environments. IET Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 18, 2963–2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.; Kim, H.; Oh, C. Development of integrated driving evaluation index by proportion of autonomous vehicles for future intelligent transportation systems. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Land Infrastructure and Transport. Road Design Manual: Road Planning and Geometry; Ministry of Land Infrastructure and Transport: Sejong, Republic of Korea, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Sekar, N.K.; Malaghan, V.; Pawar, D.S. Micro-simulation insights into the safety and operational benefits of autonomous vehicles. J. Intell. Connect. Veh. 2023, 6, 202–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.L.; Qurashi, M.; Varesanovic, D.; Sodnik, J.; Antoniou, C. Exploring the influence of automated driving styles on network efficiency. Transp. Res. Procedia 2021, 52, 380–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, E.; Olstam, J.; Schwietering, C. Investigation of automated vehicle effects on driver’s behavior and traffic performance. Transp. Res. Procedia 2016, 15, 761–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Society of Automotive Engineers SAE, SAE Standards News: SAE and ISO Refine the Levels of Driving Automation SAE-MA-06717. 2021. Available online: https://www.sae.org/articles/sae-iso-refine-levels-driving-automation-sae-ma-06717 (accessed on 8 December 2025).

- Do, W.; Saunier, N.; Miranda-Moreno, L. Evaluation of conventional surrogate indicators of safety for connected and automated vehicles in car following at signalized intersections. Transp. Res. Rec. 2025, 2679, 1118–1133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Q.; Zhao, X.; Chen, C.; Ren, W. How predictive-forward-collision-warning reduces the collision risk of leading vehicle driver. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 211, 107891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vogel, K. A comparison of headway and time to collision as safety indicators. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2003, 35, 427–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, X.; Wong, Y.; Li, M.; Chai, C. Key risk indicators for accident assessment conditioned on pre-crash vehicle trajectory. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2018, 117, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, C.; He, X.; van Lint, H.; Tu, H.; Happee, R.; Wang, M. Performance evaluation of surrogate measures of safety with naturalistic driving data. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 162, 106403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andriola, C.; Chitturi, M.V.; Noyce, D.A.; Song, Y. How similar or different are automated vehicle and human-driven vehicle crash patterns? Findings from crash sequence analysis. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 222, 108239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wen, Q.; Xu, M. Heterogeneity in crash patterns of autonomous vehicles: The latent class analysis coupled with multinomial logit model. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2025, 209, 107827. [Google Scholar]

- Drazin, S.; Montag, M. Decision Tree Analysis Using Weka. Machine Learning–Project II; University of Miami: Coral Gables, FL, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.; Lee, S. Effects analysis of traffic safety improvement program using data mining: Focusing on urban area. J. Transp. Res. 2011, 18, 77–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Chong, J.; Lu, Y.; Li, Z. Application of information gain in the selection of factors for regional slope stability evaluation. Bull. Eng. Geol. Environ. 2022, 81, 470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.