Abstract

With the deep integration of digital technology and the tourism industry, the transformation of the spatial form of smart tourism destinations and the research on their system structure have become the focus. This study adopts a mixed research approach, taking villages in the mountainous areas of southeastern China as examples, and collects empirical data through semi-structured interviews, participant observation and literature collection. This study draws on structuralist location theory to construct a four-dimensional spatial analysis model of natural environment, production economy, social norms and cultural values and incorporates a historical perspective to make up for the limitations of this theory in explaining regional dynamic changes caused by the lack of a time dimension. This study finds that digital tourism provides external resources such as the consumer market, tourism capital and information technology prompting the reconfiguration of the rural internal system. By absorbing external resources and upgrading traditional industries, rural areas have formed a more diversified, inclusive, and dynamically balanced spatial form. Furthermore, phenomena such as villagers’ relocation, e-commerce employment and local tea-growing knowledge indicate that certain predicaments still exist in the construction of digital tourism. This research can provide practical references for the development and spatial optimization of rural digital tourism.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the opening up of the rural market economy, the advent of urbanization, the development of information technology, and the influx of investment have generated significant changes in the cultural landscape, economic structure, and living environment of rural areas [1]. The change in spatial form of villages indicates that traditional rurality has been impacted by modernization. On the one hand, the traditional local features of the countryside may be overly eroded by commercialization, losing their original characteristics; on the other hand, the traditional local characteristics of the countryside, which have potential commercial value as a tourism resource, need to be continuously revitalized. This contradiction between development and conservation is particularly prominent in the process of digital tourism construction in some ancient Chinese villages. Then, what is the intrinsic mechanism by which digital tourism drives the transformation of rural spatial forms? And how can a systematic analytical framework be constructed to achieve a balance between the development of digital tourism and the protection of traditional rural characteristics?

Some studies argue that the impacts of external factors such as consumer markets, regional policies, information technology, and tourist volumes on space render tourism destinations complex and dynamic [2,3]. Digital transformation can enhance the image of tourist destinations and assist the destination track the behavior of tourists [4,5]. Although digital technology is of great significance for the dynamic construction of tourist destinations, scholars’ evaluations of it vary. Tian and Solana et al. are pessimistic, arguing that for traditional villages, the capital, tourists, and technology influx during the dynamic transformation of tourism destinations may conflict with rural local culture, thereby leading to the gradual disappearance of the rural characteristics of traditional villages [6,7]. In contrast, Massey et al. argue that mobile forces may offer opportunities for the revival and diversification of rural life, and that rural areas can exhibit “progressive sense of place” in a dynamic context [8].

In terms of the spatial dynamics of destinations, the structuralist location theory posits that geographical space is a product of the interaction of structural forces such as the natural environment, modes of production, capital markets, and socio-cultural factors [9]. This dynamic construction form is reflected in the interweaving of various rural relationships, the enhancement of landscape aesthetics, and the increased diversity of economic forms [10,11]. However, the structuralist location theory overemphasizes the horizontal structural relationship interaction and lacks a vertical time dimension to explain the dynamic evolution [12]. Therefore, it is not only difficult to trace the historical trajectory of the transformation of the destination space form, but also hard to conduct an ecosystem analysis of the spatial changes in traditional villages caused by the development of tourism.

To make up for these deficiencies, this study draws on structural location theory, supplements it with the trajectory of historical changes, and constructs a comprehensive dynamic system for analyzing the digital tourism-driven transformation of rural spatial forms: (1) clarify the core dimensions and observable indicators of the dynamic transformation of rural space, and thereby reveal the mechanism by which digital tourism empowers the transformation of rural space; (2) construct a measurable analytical framework integrating structuralist location theory and a temporal perspective.

This study employed methods such as literature analysis, semi-structured interviews, and longitudinal observation to investigate the transformation of destination spatial forms in eastern Chinese villages driven by digital tourism from four aspects: natural environment, production economy, social governance, and cultural concepts. This research is of great significance for exploring the sustainable development of ancient village tourism in the digital age.

2. Literature Review and Interpretation Framework

2.1. Literature Review

The concept of smart tourism destination emerged with the development of smart cities, based on the deep integration of information technology and tourism scenarios [13]. Early research mainly focused on the compatibility between digital technologies and tourism destination contexts. Topics such as online booking services [14], e-commerce models [15], the digital divide [16], and digital marketing [17], have all been incorporated into discussions on destination tourism, yet these single-dimensional topics are all related to the construction of destination digital infrastructure [18]. In recent years, the structural perspective of the ecosystem has become the mainstream direction in the research of smart tourism destinations. Since 2016, Buharis et al. [19,20] have criticized the traditional research approach that focuses solely on the application of ICT technologies or the governance of smart tourism destinations, and proposed to construct an overall ecosystem structure framework for the development of smart tourist destinations.

In fact, as early as the 1970s, the structuralist location theory had already laid the theoretical foundation for the systematic structural analysis framework of tourist destinations. Massey pointed out that the development of location is restricted by social structures production methods and labor-capital relations, and advocated conducting location research from the dimension of the interaction between society and space [21]. That is, spatial location is the interwoven product of environmental, social, cultural and economic relations [22]. Harvey expanded the structuralist location theory through the concept of “spatial fix”, pointing out that the formation and evolution of location are essentially the spatial manifestation of the capital circulation of capitalism [23]. However, the structuralist location theory is limited in that it only emphasizes the static spatial structure relationship of the social system [12]. To understand the evolution of a specific spatial economic structure, it is necessary to trace back its historical process through time [24]. As Shipp et al. [25] hold, time flowing in a linear manner can trace the dynamic features of a system rather than its static structure.

“Dynamics” is an important concept in sustainable development. When discussing the sustainable development process of information and regional systems, Knox proposed the concept of “space of flows” based on various fluid elements such as material flow, population flow, and information flow [26]. First, the dynamic nature, apart from being present in the process of time and historical development, is also reflected in the renewal of the natural environment, capital investment, population migration, and the promotion of local culture, among other dimensions that constitute the rural space [27,28]; Second, in terms of causes, the transformation of social demands for the functions of production, consumption, ecology, and recreation in rural areas has driven the flow of various elements in space [29]. The flow of rural spatial elements shapes regional transformation, and the functions of rural areas change accordingly [30]. For example, changes in rural spatial structure and regional transformation have gradually transformed traditional villages, which were once centered on agricultural production, into new types of villages that integrate functions such as ecological protection, leisure and vacation, and cultural consumption [31].

Through literature review, it can be known that: (1) The spatial structure perspective of the ecosystem is a cutting-edge direction in the research of smart tourism destinations, but the current research depth in this field is insufficient; (2) Structuralist location theory lays a theoretical foundation for the study of destination spatial structure, but it lacks a perspective of temporal fluidity. Furthermore, the systematic mechanism of digital technology in rural spatial transformation has not been fully explored.

2.2. Analytical Framework

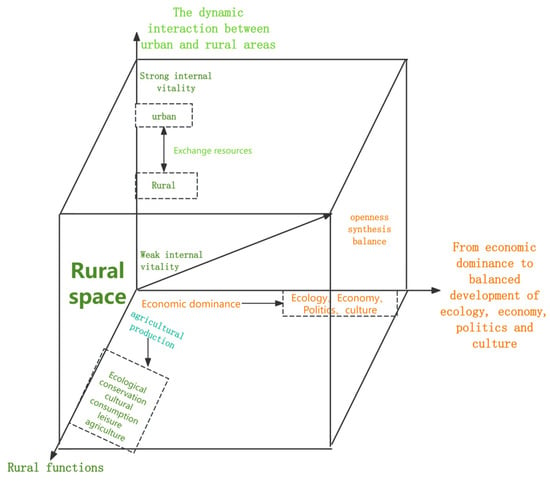

Based on the structuralist location theory, the perspective of temporal fluidity, and spatial theory, this study constructs a systematic analytical framework for analyzing the dynamic transformation of rural spaces (Figure 1). By integrating the flow of dynamic elements, structural reorganization, and functional upgrading, this framework overcomes the static limitations of traditional spatial theories and aligns with the ecosystem perspective of smart tourism destinations. (1) Axis1: urban–rural dynamic interaction axis (Vertical Axis). It reflects the core external driving force for the transformation of rural space, focusing on the flow of elements and resource exchange between urban and rural systems driven by digital technology; (2) Axis 2: system structure reconfiguration axis (Horizontal Axis). It reflects the evolution of the internal structure of the rural spatial system. For instance, driven by digital tourism, the rural space has transformed from a structure dominated by agricultural production to a balanced structure encompassing ecology, economy, social governance, and cultural values; (3) Axis 3: spatial function upgrading axis (Depth Axis). It reflects the transformation of rural space from being centered on agricultural production to an integrated space that combines ecological protection, cultural consumption, leisure and vacation, and modern agriculture. For instance, influenced by digital technology, shared farms, digital cultural experience zones, and smart facility agriculture have shaped multi-functional spatial forms.

Figure 1.

Theoretical Analysis Framework of Digital Tourism Driving the Transformation of Rural Spatial Form. (Note: The framework is a 3D model with three orthogonal core axes. Arrows indicate the direction of dynamic evolution. Each axis corresponds to a core dimension of transformation, and the intersection of the three axes reflects the integrated state of rural spatial development. Source: Author’s own construction based on field data, structuralist location theory, and space concept).

This theoretical framework also holds reference significance for the quantitative research on rural spaces. Data collected along the urban–rural dynamic interaction axis, such as the scale of digital capital inflow, tourist volume, and talent return rate, can quantify the intensity of urban–rural interaction; data gathered along the systematic structural reorganization axis, including the carbon emission ratio, non-agricultural industry proportion, smart governance level, and the degree of cultural heritage activation, can measure the balance of the rural spatial system; data collected along the spatial functional upgrading axis, such as the number of leisure facilities, residents’ income sources, and tourist satisfaction, can evaluate the effectiveness of functional transformation.

Within this framework, the increase in rural spatial elements (such as the number of digital infrastructure and the types of digital tourism jobs), the improvement of economic income (such as per capita disposable income and e-commerce turnover), the diversification of rural governance models (such as the combination of traditional rural clan systems and modern information-based governance), and the exploration of the multi-functional aspects of rural culture (such as enhancing the commercial value of traditional culture) can effectively verify the dynamic transformation of rural space.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Case Selection

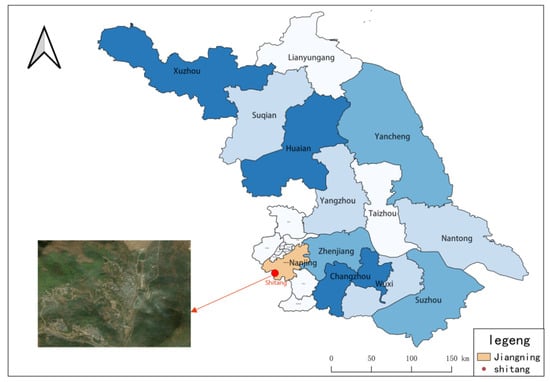

Shitang Village, with a history spanning over 800 years and located approximately 35 km from Nanjing’s urban area (Figure 2), is a suburban development village. It encompasses 73.33 hectares of cultivated land. The village has an excellent ecological environment, with vast bamboo forests and numerous tea plantations. In the 1980s, due to limited economic opportunities, a significant number of young villagers migrated to urban areas in search of employment. The village began using its natural landscape and cultural heritage in 2011 to develop tourism. In 2015, the village set up Nanjing’s first village-level e-commerce service center to facilitate online shopping and the sale of agricultural products. In 2016, to host the Internet Innovation and Entrepreneurship Competition, the government invested over CNY 20 million to build an information infrastructure, achieving full coverage of optical fibers and cables throughout the village. Since 2018, with the launch of China’s national Digital Village Strategy, Shitang Village built an e-commerce service center, and added projects such as the Tianyuan e-station shared farm and the Internet Conference Center. With the continuous return of the population, by the end of 2022, the village had 460 households and approximately 1200 residents, with 135 farmhouses having joined the e-commerce platform.

Figure 2.

Geographical coordinates map of Shitang Village. (Note: Shitang Village is located in Jiangning District, Nanjing City, Jiangsu Province, China. The map shows the geographical location and mountainous environment of Shitang Village. Author’s own illustration).

To enhance the applicability of research perspectives in the construction of rural digital tourism, simultaneously, we used Yu Village in Anji County, Huzhou City, Zhejiang Province, which we had investigated from November to December 2023, as auxiliary argumentation materials. The reasons are as follows: (1) Comparability: Both villages are surrounded by mountains. Yu Village covers an area of 4.86 square kilometers and has a population of 1050. Its agricultural resources, natural environment, geographical layout, and total population are comparable to those of Shitang Village; (2) Heterogeneity: There are some differences between the two. Tourism in Shitang Village is characterized by e-commerce and computer competitions, while in Yu Village, it is characterized by the creation of short videos of local resources. This difference helps reveal diverse impacts of digital technology on rural spaces; (3) Representativeness: As early practitioners of digital rural tourism, these two villages have mature development models, and their experiences can serve as references for similar areas. It should be noted that, both of these cases are located in the economically developed eastern part of China, where digital infrastructure, policy support and consumer markets are superior to those in rural areas of central and western.

3.2. Research Methods and Data Analysis

3.2.1. Research Method

This study adopted a mixed research approach, combining empirical survey data with structuralist location theory. Structuralist location theory provides a theoretical framework for understanding how structural forces such as digital infrastructure construction (environment), rural e-commerce operation (economy), tourism policy regulation (politics), and cultural commodification shape the spatial form of rural areas. To address the lack of a diachronic perspective in structuralist location theory, we longitudinally tracks historical data (Before 2011). To achieve triangulation of the methodology, we employed semi-structured interviews, participatory observation, document analysis and spatial records [32].

3.2.2. Data Collection

A total of 51 valid interviewees were recruited via snowball sampling to cover multiple stakeholders. To ensure the diversity of the samples, the sample included 18 local residents (≥10 years of residency), 20 tourism operators (engaged in rural tourism or e-commerce operations), 4 government staff (responsible for rural planning and tourism management), and 9 tourists.

Each interview lasted 45 to 90 min. We recorded all the interviews and transcribed them word for word into a 30,000-word text dataset. The interview outline (Supplementary File) focuses on three core dimensions: (1) Perceived changes in rural space (natural environment, production economy, social norms, cultural values) before and after digital tourism development; (2) Structural factors influencing spatial transformation (e.g., policy support, digital infrastructure, capital inflow); (3) Adaptive behaviors and subjective perceptions of micro-actors (e.g., relocation experiences, e-commerce employment, identity changes). Interviewees were coded by identity (CM = Villagers, JYZ = Operators, CW = Government Staff, YK = Tourists) and sequence (e.g., CM-01) to ensure traceability (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants in Shitang Village.

We conducted systematic participant observation over a total of 32 days during four field surveys in Shitang Village (April, July, September, and November 2024). The observation focused on: (1) The daily operation of digital tourism sites (e-commerce service centers, shared farms, tea mountains); (2) Behavioral interactions in public spaces (interactions between tourists and residents, daily affairs of the village committee, e-commerce training); (3) Spatial changes (land use conversion, house renovation, infrastructure expansion). We recorded the observations through notes, geotagged photos, and short video clips (totaling 15 min) to capture the dynamic spatial practices. The research team participated in the villagers’ daily activities (such as tea picking and packaging of e-commerce products) to gain an insider’s perspective.

To verify the primary data, we collected village chronicles published publicly, statistical yearbooks of previous years, articles from official WeChat public accounts, and media reports on rural digital transformation. These materials are used to measure changes in rural space, land use and infrastructure.

3.2.3. Data Analysis

To enhance the integration of empirical cases and theoretical research, we have formulated an analysis process of “structural coding—thematic induction—theoretical dialogue” (Table 2). Data analysis was conducted using NVivo 15 software. The first step is open coding. We coded the interview records, observation notes and secondary data to identify initial concepts (such as “digital infrastructure investment”, “spatial migration”, “cultural commercialization”). At this stage, a total of 24 basic concepts and 4 initial categories (natural environment, production economy, social norms, cultural values) were extracted; The second step is axial coding. We determine the core categories by exploring the causal relationships among the initial categories, for instance, from “policy-driven infrastructure improvement” to “expansion of tourism space”. The third step is selective coding. We have distilled three core themes: (1) the structural driving forces of rural spatial transformation; (2) the adaptability and agency of micro-actors; (3) the temporal dynamics of rural spatial transformation; The fourth step is reliability verification. Two independent coders analyzed 20% of the data to test the reliability between coders, with Cohen’s Kappa coefficient being 0.82 (≥0.75 indicates good reliability), this method adheres to qualitative research standards, this methods adhere to qualitative research standards [33]. Coding differences were resolved through group discussions with a third researcher.

Table 2.

Flowchart of the Research Process.

4. Result

4.1. The Overall Morphology of Rural Space Before the Initiation of Digital Cultural Tourism

Before 2011, the traditional settlement pattern, agricultural industrial characteristics, clan structure, and aesthetic taste of Shitang Village collectively reflected the close connection between rural character and traditional rural society [34]. In the past, the rural space of Shitang Village was characterized by a closed natural environment, limited economic production, internally dependent social norms, and local cultural beliefs.

In terms of the natural environment, the farmland in Shitang Village is fragmented and scattered, with only 0.0667 hectares per capita. Before 2007, the village’s infrastructure was outdated, with only one gravel road connecting it to the outside world, and the residents’ houses were dilapidated. The outdated settlement environment and restricted transportation conditions exacerbated the differences between urban and rural areas, supporting the view of Fan et al. The significant structural boundaries between urban and rural areas are usually reflected in population density, settlement pattern, distance from the city, etc. [35].

In terms of production economy, before 2011, the industrial structure of Shitang Village was relatively single, and villagers mainly relied on traditional agriculture, such as growing rice, corn, tea, and animal husbandry for a living. Although animal husbandry helped increase farmers’ income sources, the number of pig farmers in the village once reached nearly 200 at its peak, which led to pollution of the living area’s environment. Wilson believes that farmers regarded agricultural production as the main driving force for the normal operation of society in order to achieve self-sufficiency in agricultural production and maximize grain output. Therefore, people in the traditional period usually made significant investments and labor inputs in the agricultural industry [36].

In terms of social norms, according to historical records, the Wang family made significant contributions to agricultural reclamation and rural governance during the Southern Song Dynasty. Today, kinship centered around the Wang family continues to help maintain trust among villagers and coordinate daily affairs. For example, farmstay cooperatives and e-commerce are organized through informal networks, characterized by an inward-looking culture that facilitates quick decision making and low-cost cooperation in digital tourism. In addition, the traditional ancestral worship ceremony of the Wang family on October 10th has also been incorporated into the rural cultural tourism strategy, meaning that the question of how to strike a balance between the “value activation” and “conservation efforts” of traditional culture has become a topic that needs to be re-examined in a modern context.

In terms of cultural concepts, the cultural narrative of Shitang Village reflects distinct local characteristics. For example, the “Lion-back Umbrella” tourism cultural landscape, which has a history of over 200 years, is based on a natural rock on which a very tenacious beech tree grows. This cultural landscape was once regarded by ancestors as having special significance for providing favorable weather and enabling agricultural production. Since then, the identity of this cultural landscape has changed due to commercialization. The strong promotion of online platforms has packaged it as part of local digital tourism.

Overall, before information technology was incorporated into Shitang Village’s tourism, the closed rural space and the single industrial structure model hindered its development, which relied on the traditional agricultural model. Simultaneously, for Shitang Village, which is centered on material production, the rural living environment, rural norms, and religious culture also lean toward material production. As a result, there is an imbalance in the spatial structure of rural areas.

4.2. The Morphological Changes in Rural Space After the Launch of Digital Cultural Tourism

4.2.1. Tourism’s Effect on the Digital Transformation of Human Settlements

Tourism being an outward-oriented industry, has particular importance for the gentrification of rural society and the reconstruction of social spatial form in rural areas [37]. To align with the image of the Shitang Internet Town, the village incorporated the following projects into its rural tourism development strategy: providing tourists with diverse consumer products, renovating the appearance of houses, reserving land for digital rural facilities, and building Internet green shared vegetable gardens. After a collective discussion, the village decided to demolish some dilapidated houses and 135 pigpens, re-plan rural land use, and uniformly renovate the style of villagers’ houses. A similar situation occurred in the village of Yu, which the research team investigated. In 2023, Yu Village, provided an ideal space for young people to live stream and shoot videos by integrating land resources, repairing houses, and adopting agricultural products online. This indicates that the construction of the Internet and digital infrastructure can bring about tremendous changes in rural areas [38].

The construction of tourism-supporting facilities included the e-commerce service center, the Tianyuan e-station shared vegetable garden, the “Internet + Starry Sky” VR astronomy science popularization base, and the Shitang Village Internet Conference Center, with a construction area of 3000 square meters. These projects exert considerable pressure on the small mountain village, which is already facing a serious shortage of land. To accommodate collective planning, some villagers had to leave Shitang Village, where they had lived for many years, and move elsewhere. A former villager who returned home for a visit told the researchers about his feelings: “Although the government has built new resettlement houses for us several kilometers away, many of us have grown up here, our ancestors have lived here, and we have deep feelings for this place. After moving away, we are still very sad and often want to come back and visit. But there’s no way around it. Since we want Shitang Village to get better and better, someone has to sacrifice their own interests.” (CM-01).

4.2.2. The Development of Emerging Agricultural Industries and the Transformation of Traditional Production Relations

Since 2016, Shitang Village has been designated as the host of the Jiangsu Internet Innovation and Entrepreneurship Competition. Each year, during the event, the village committee uniformly organizes the operators of farmhouses to provide catering and accommodation services for the participants. This collective action aimed at boosting rural tourism consumption has put some business operators in a complex balancing act—considering the interests of the rural community as well as their own gains and losses, involving multiple factors such as economic costs, face, and morality. The words of one homestay operator reveal this ambivalent state of mind: “The village committee has set a uniform accommodation price of CNY120 per room per night. This price is profitable for other families, but my homestay has a high investment cost. Participating in this event is a bit uneconomical for my family, but most of the operators have participated. Considering the collective interests and neighborhood relations, we still chose to participate.” (JYZ-01).

In addition, tourists can adopt a plot of land through a remote “fruit and vegetable adoption” model, entrust a professional farmer to look after vegetables or fruit trees, and monitor its growth through a dedicated Internet mini-program. Among our respondents was an elderly male villager. He believed that helping to look after the fruit trees could once again reveal his social value. “Unlike young people, we have more experience in farming and it doesn’t take much effort to look after the fruit trees. This job not only lifts my mood but also increases my income, which is better than being idle at home.” (CM-02). This study found that Shitang Village offers various light physical jobs for the elderly, such as cleaners, sightseeing vehicle drivers, security guards, and shared farm managers, more than 130 idle elderly laborers have been re-employed. This result is consistent with the research findings of Lin et al. [39], which indicate that older farmers have richer social networks and stronger environmental adaptability. Re-employment enables them to gain more benefits from rural tourism and effectively enhance their sense of happiness.

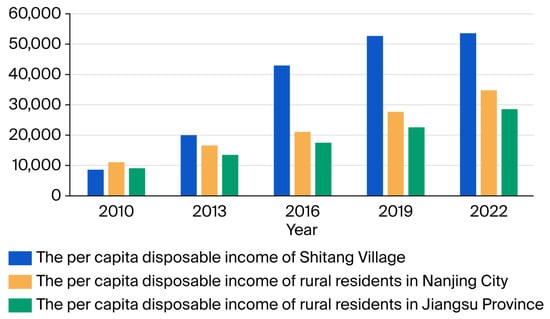

According to investigation, before the rise of digital tourism in 2011, there were 22 households in the village that met the national poverty standard, including 16 households with labor and 6 households without labor. Shitang Village achieved full poverty alleviation in 2019, with the per capita disposable income of villagers was CNY 52,681,which exceeded the average level of Jiangsu Province [40]. Since 2022, the per capita disposable income of the villagers has remained stable at over CNY 50,000 (Figure 3). The primary income sources of villagers in Shitang include the following: First, operating rural restaurants and homestays. The second is the sale of local agricultural products through e-commerce. The third is the attainment of land dividends, asset dividends, and house rents through tourism cooperatives. In 2024,more than 35 percent of villagers were engaged in rural tourism, with income from farmhouses, homestays, and tourism-related facilities accounting for 70 percent of villagers’ income. The above research indicates that digital tourism has effectively promoted the economic growth of Shitang Village.

Figure 3.

The trend of per capita disposable income in Nanjing City and Shitang Village, Jiangsu Province.

4.2.3. Digital Rural Governance and Regulation of Social Order

Digital technology has changed the limitations of traditional rural governance and addressed many problems in urban–rural integration [41]. In Shitang Village, digital technology has exceeded the intrinsic dependence of traditional rural norms and restructured the spatial order facing the outside world. To support the second entrepreneurship of business operators and facilitate the entry of agricultural products into the city, all 135 rural inn operators in the village have integrated their businesses into the e-commerce platform. All agricultural products sold by the e-commerce center have QR code identity cards, and the application of blockchain technology provides an effective guarantee for tourists to trace the origin of these products.

A rural innkeeper said that: “My daughter used to work outside. Now she has returned to the village and opened a rural inn. Running a country inn not only makes her financially independent but also makes it easier for her to look after her children. When the inn is not busy, we go to the e-commerce service center. There, village-level instructors teach us how to open an online store and expand product promotion. We women often get together to talk about our daily lives.” (JYZ-02). This indicates the growth of tourism in Shitang Village, which has attracted labor to return to the village to start businesses. This study found that, some villagers who have mastered new technologies have established new networked relationships with online consumers and community members through the Internet Conference Center. This diverse social order reflects the transformation of Shitang Village from a closed, bloodline-based traditional village to an open, multifunctional modern village. For the participants in the construction of digital villages, getting emotional feedback from peers and even strangers through cooperation and competition are also an effective incentive model [42].

A similar situation has emerged in Yu Village. Wu, a young entrepreneur, usually guides villagers in using portable communication devices to create short videos about the traditional craftsmanship and culture of Yu Village. To facilitate communication and training among creators, he often explains short video creation techniques and agricultural product marketing knowledge to villagers in his rented farmhouse courtyard, which builds a deep trust relationship between him and the villagers. For these new farmers, participating in the construction of digital villages is not merely a temporary assembly in physical space, nor is it purely driven by utilitarian economic interests; it is a social action that closely links their own life experiences with the fate of rural development [43].

4.2.4. Reconstruction of Rural Cultural Forms via Digital Tourism

The rural tourism industry, centered on the digital economy, is transforming the traditional rural cultural system with an unstoppable force. In Shitang Village, we learned that people of different identities have ideological divisions in the transformation of rural culture:

First, a village official affirmed the commercial value of rural culture: “In the past, our understanding of the potential value of rural resources was limited, and we didn’t have many ideas about how to give economic attributes to traditional culture. The construction of the digital village has made me realize the huge commercial value of culture.” (CW-01). Nowadays, Shitang Village has established a village history museum, which displays various traditional farm tools, village historical figures, and farming photos with modern electronic screens. This move, which combines traditional culture with contemporary tourism consumption demands, has attracted the attention of tourists.

Second, Geertz believes that local knowledge generated in a specific cultural environment is a form of local experience knowledge that embodies people’s unique life patterns [44]. In Shitang Village, one villager said that: “I’ve heard that those electronic devices have data sensing and precise analysis capabilities and can improve the quality of tea, but I feel that the actual effect is not significant. The poles of those devices are usually very tall and stand in the tea gardens to monitor wind, light and humidity. But there are no monitoring devices buried in the soil.” (CM-03). The actual deviation between such intelligent equipment and local knowledge confirms Scott’s view that farmers’ stubbornness as producers of local agricultural knowledge stems from their years of practical experience, which taught them that “crops have the most stable and reliable yields in specific environments” [45].

Finally, a tourist surnamed Wang talked about his feelings about the grand ancestral worship ceremony: “I saw information about the grand ancestral worship ceremony of the Wang family on the Internet, which aroused my strong interest in this traditional ceremony. Although a few villagers questioned my behavior as an outsider and showed unfriendly attitudes, I thought that eating and spending in this village would always be beneficial to them.” (YK-01). Tourists in Shitang Village have not truly integrated into the rural cultural system under the cultural commercialization model, which confirms Cheng’s core research conclusion on the commercial transformation of rural space, namely, that the role played by external heterogeneous subjects such as tourists in the rural social network is far less significant than that of subjects within the villager community [46].

5. Discussion

5.1. Dynamic Reconstruction of Rural Space: Breaking the Urban–Rural Dual Structure Through Mobility

From the perspective of the dynamic reconstruction of rural spatial form, although some scholars have called for the academic community to pay more attention to the phenomenon of population mobility in the context of current rural urbanization in China [47], the intrinsic mechanism of “dynamics” in rural sustainable development deserve more attention. For rural areas that introduce information technology into traditional industries, the ability to promote factor flow and achieve sustainable development stems from two core aspects: Firstly, breaking down the dual structural barriers between urban and rural areas and overcoming the obstacles of economic division of labor and institutional barriers in the traditional urban–rural model [48]; Secondly, through the driving effect of tourism, a dynamic balance among the environmental, economic, institutional and cultural dimensions of the destination is coordinated [49]. This remarkable change in modern rural society, overturns Fei’s last century assertion of the immobility of rural China, which he once held based on traditional Chinese culture and customs that “rural society is local, immobile and isolated” [50]. Dynamic is not only crucial for the sustainable development of rural areas, but also a key point in the formation of rural pluralism. The case of Shitang Village demonstrates that modern rural areas are no longer solely focused on grain production, but are instead committed to promoting the circulation of various elements through the deep integration of tourism with cultural industries, e-commerce, and traditional agriculture, thereby creating new rural complexes with diversified functions. This confirms Lu’s view that new rural areas have multiple functions, and the non-agricultural consumption function of rural areas is at the core of new rural areas [51].

Notably, this study, through comparative analysis of the historical data of Shitang Village and Yu Village, distinguishes the unique impact of digital tourism from other concurrent driving factors such as regional policies and external investments: The “Opinions on High-Quality Promotion of Digital Rural Construction” and other strategies issued by the governments of Jiangsu Province and Zhejiang Province have provided institutional support for the spatial transformation of rural areas. Meanwhile, the cases of Shitang Village and Yu Village show that external investment mainly focuses on commercial operation projects such as homestays and coffee shops, as well as the construction of rural infrastructure. This is essentially different from the marketization process of rural resources driven by digital tourism and the transformation of rural production relations from individual agricultural operations to cooperative operations.

5.2. Micro-Actor Adaptation: Identity Transformation and Value Reconstruction

Digital villages have endowed farmers with new professional identities and changed their values and life concepts. For a long time, the one-sided understanding of farmers’ identity and underestimation of the value of labor have not only bound farmers’ thinking but also dampened their enthusiasm for production. Gu et al. argue that farmers have long been defined as providers of agricultural products, and the magnitude of their personal value is often associated with the output of grain production [52]. However, the research results on the re-employment of the elderly labor force and the growth of farmers’ income (Section 4.2), show that farmers’ production attitudes, life concepts, and personal values change with improvements in income levels and living conditions. In this regard, Zhang et al. believe that, in the face of social structure transformation, re-understanding the multiple functions of agriculture, rural areas, and farmers after activation, mobility, and reorganization in their respective fields is the entry point for studying rural reconstruction in traditional villages [53].

A prominent finding of this study is the re-employment of the elderly labor force. Internal statistics from the village committee of Shitang Village show that over 130 idle elderly laborers have achieved re-employment through digital tourism. This not only increased their total personal income by approximately 30%, but also enabled them to regain social value recognition and emotional satisfaction. This phenomenon reflects the transformation of rural labor force structure driven by digital tourism, which not only optimizes the allocation of human resources but also enriches the connotation of rural elderly care. Compared with the traditional rural elderly care model that relies on family support, this “employment-based elderly care” model has stronger sustainability and social value, providing a new path for solving the aging problem in rural areas.

Although this study lacks systematic gender-based quantitative data, preliminary observations show that women have become important participants in digital rural construction. Through activities such as running homestays and starting e-commerce businesses, women have achieved economic independence and established emotional connections with other groups based on professional ties in the e-commerce entrepreneurship space. This breaks Beauvoir’s view that “women’s self-realization initiative cannot free them from internal constraints” [54]. However, it should be noted that women still face multiple pressures such as balancing family and work, and coping with digital technology learning. Future research needs to conduct targeted gender analysis with more systematic empirical data to explore the differentiated impacts of digital tourism on different gender groups.

5.3. Sustainability Trade-Offs: Cultural Conservation and Economic Development in Digital Rural Development

Traditional rural culture and local characteristics are facing the problem of excessive commercialization due to the entry of emerging technologies, the rise in tourism, and changes in the geographical spatial pattern. Some scholars argue that we must be aware of and avoid the potential risks associated with the commercialization of rural space [55]. It is undeniable that rural social spaces and their local traditional characteristics are being reconstructed along with changes in industrial forms, but there is no definitive conclusion as to whether this is more beneficial or detrimental to the countryside. Based on the research results of Section 4, rural indigenous people, have complex attitudes toward digital tourism development: some have negative sentiment about relocating from their hometowns; others are dissatisfied with the conflict between local knowledge and modern electronic devices; and some reject tourists’ participation in traditional sacred rituals. Therefore, balancing economic benefits and local cultural protection will be a challenging for the future development of traditional villages. The commercialization of traditional sacred landscapes and tourists’ participation in traditional rituals reflect that in the context of digital tourism development, the protection of rural culture should focus on the inheritance of “living culture” rather than merely remaining at the level of formal commercial participation.

For this reason, this study proposes the following policy recommendations: (1) In terms of the natural environment, for villages with similar resource endowments and geographical advantages to Shitang Village, it is advisable to consider introducing digital technologies, building digital infrastructure, and developing characteristic industries such as e-commerce for agricultural products and shared farms; (2) In terms of industrial economy, promote the integration of local knowledge and digital technology, and enhance the compatibility between smart agricultural equipment and traditional farming experience; (3) In terms of social governance, establish a community participation mechanism to encourage villagers to take part in rural planning, while protecting the interests and demands of vulnerable groups; (4) Protecting rural memory spaces and traditional culture, and incorporating historical relics such as ancestral halls, ancient wells and ancient trees into tourism development plans.

6. Conclusions

Based on practical cases, this study examines the interaction between smart tourism and the dimensional components of destination space (natural environment, production economy, social norms, and cultural values), expanding the relevant research on digital infrastructure-driven rural revitalization. The theoretical contributions are as follows: (1) constructing an analytical framework integrating structuralist location theory and a temporal perspective to analyze the dynamic transformation of rural spatial forms, which compensates for the inadequacies of traditional spatial theories in dynamic analysis [12]; (2) revealing the multi-dimensional mechanisms through which digital tourism empowers rural spatial transformation by investigating dynamic elements such as capital, technology, and population in the digital context, thereby enriching research on smart tourism destinations from an ecosystem perspective [19].

This study finds that there is a certain tension between digital tourism and rural space. At the positive level, digital tourism has promoted the reconfiguration of rural internal systems through external driving forces such as consumer markets, tourism capital, and information technology. For instance, the digital transformation of the human settlement environment, the restructuring of production relations, the opening-up of social norms, and the empowerment of cultural values have facilitated changes in the production and lifestyle of Shitang Village (Table 3). Specifically, over 130 elderly people have been re-employed, more than 130 digital enterprises are active online, and the per capita disposable income of villagers has stabilized above CNY 50,000. The construction of infrastructure such as rural e-commerce centers, Internet conference centers, and innovative tourism platforms has not only optimized agricultural production methods but also reshaped the labor force structure [48,56]. At the negative level, although Shitang Village has preserved traditional rural culture by retaining key cultural landmarks such as the Wang Clan Ancestral Hall and the “Lion Carrying Umbrella”, as discussed in Section 4, during the re-planning of the rural digital space and the integration of land resources, it is still necessary to take into account non-quantifiable factors such as the cultural background, participation willingness and spatial perception of the participants.

Table 3.

Photos of Digital Cultural Tourism Scenarios in Shitang Village.

Based on the temporal process and the fluid elements such as capital, technology, and population, this research proposes a novel research perspective on the dynamic transformation of rural space. It addresses the limitation of structuralist location theory in lacking a temporal dimension and enriches the systematic research on the spatial transformation of smart tourism destinations. From a practical perspective, this research provides a reference model for the sustainable development of digital tourism in mountainous villages—particularly the specific experiences of balancing economic development with the protection of historical culture—thus holding significant reference value for similar ancient villages.

This study also has certain limitations. The research sample is limited to Shitang Village and Yu Village in eastern China, and the research conclusions may not be fully applicable to rural areas in central and western China with different resource endowments and development levels. Furthermore, due to the lack of long-term panel data, research on gender analysis and changes in ecological footprints in the context of digital villages is still insufficient. These limitations indicate that in the future, it is necessary not only to conduct cross-regional and multi-case studies, expand the research scope to rural areas in central and western China, and explore the differentiated development paths of digital tourism under different resource endowments, but also to collect long-term panel data, analyze the differentiated impacts of digital tourism on different gender groups, and track the dynamics of rural spatial transformation and sustainable development.

In conclusion, this study offers practical insights for policymakers, including how to design products that meet market demands while preserving local characteristics and formulating strategies that contribute to the region’s overall development. The research suggests that, as a whole system, the rural space can explore a sustainable development path that suits local realities through the dynamic integration of traditional local features and new technologies.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su18010105/s1.

Author Contributions

J.Q.: writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision, formal analysis, software, methodology, conceptualization, and validation. X.D.: writing—review and editing, supervision, resources, project administration, and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by the Social Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province, China, under the project “Ecological Culture of Jiangsu Water Towns” (22WMB022).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ghose, R. Big Sky or Big Sprawl? Rural Gentrification and the Changing Cultural Landscape of Missoula, Montana. Urban Geogr. 2004, 25, 528–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richins, H.; Agrusa, J.; Scott, N.; Laws, E. Tourist Destination Governance Decision Making: Complexity, Dynamics and Influences; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2011; pp. 83–90. [Google Scholar]

- Almeida, A.; Golpe, A.; Justo, R. Regional Tourist Heterogeneity in Spain: A Dynamic Spatial Analysis. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2021, 21, 100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa Liberato, P.M.; Alén-González, E.; De Azevedo Liberato, D.F.V. Digital Technology in a Smart Tourist Destination: The Case of Porto. J. Urban Technol. 2018, 25, 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisa, D.G.; Parapanos, D.; Heap, T. The Role of Digital Footprints for Destination Competitiveness and Engagement: Utilizing Mobile Technology for Tourist Segmentation Integrating Personality Traits. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2025, 27, e70006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.P.; Han, D. Urbanization and the “End of Villages”. J. Soc. Sci. Jilin Univ. 2011, 51, 11–17. [Google Scholar]

- Solana-Solana, M. Rural Gentrification in Catalonia, Spain: A Case Study of Migration, Social Change and Conflicts in the Empordanet Area. Geoforum 2010, 41, 508–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Place, Space and Gender; Capital Normal University Press: Beijing, China, 2018; pp. 157–202. [Google Scholar]

- Basile, R.; Commendatore, P.; Kubin, I. Complex Spatial Economic Systems: Migration, Industrial Location and Regional Asymmetries. Spat. Econ. Anal. 2021, 16, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deller, S. Rural Poverty, Tourism and Spatial Heterogeneity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 180–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zeng, L.; Tang, X. Aesthetic Heterogeneity on Rural Landscape: Pathway Discrepancy Between Perception and Cognition. J. Rural Stud. 2022, 92, 383–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, C.A. Regional Analysis in World-System Perspective: A Critique of Three Structural Theories of Uneven Development. Review 1987, 10, 597–648. [Google Scholar]

- Lanquar, R.G. Scenarios for a Smart Tourism Destination Transformation: The Case of Cordoba. Spain. In Smart Systems Design, Applications, and Challenges; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 326–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogdanovych, A.; Berger, H.; Simoff, S.; Sierra, C. Travel Agents vs. Online Booking: Tackling the Shortcomings of Nowadays Online Tourism Portals. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism; Springer: Vienna, Austria, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Alford, P. The Impact of Technology on Tourism Marketing, E-Commerce and Database Marketing. In The International Marketing of Travel and Tourism: A Strategic Approach; Vellas, F., Bécherel, L., Eds.; Macmillan Education: London, UK, 1999; pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Minghetti, V.; Buhalis, D. Digital Divide in Tourism. In Encyclopedia of Tourism Management and Marketing; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2022; pp. 942–946. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, P.; Rawat, N.; Srivastava, S.K.; Singh, P.; Joshi, R. Customer Attitude Towards Digital Marketing: An Empirical Study of Digital Marketing Influence on Youth. Eur. Econ. Lett. (EEL) 2023, 13, 59–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Jiang, J. How Does Digital Infrastructure Construction Affect Tourism Development? Evidence from Chinese Cities. Curr. Issues Tour. 2025, 28, 3451–3467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boes, K.; Buhalis, D.; Inversini, A. Smart Tourism Destinations: Ecosystems for Tourism Destination Competitiveness. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2016, 2, 108–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivars-Baidal, J.; Casado-Diaz, A.B.; Navarro-Ruiz, S.; Fuster-Uguet, M. Smart Tourism City Governance: Exploring the Impact on Stakeholder Networks. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2024, 36, 582–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massey, D. Towards a Critioue of Industrial Location Theory. Antipode 1973, 5, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustin, M. Why Did Space Matter to Doreen Massey? In Doreen Massey Critical Dialogues; Werner, M., Peck, J., Lave, R., Brett, C., Eds.; Agenda Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2018; pp. 89–102. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, D. The Spatial Fix—Hegel, Von Thunen, and Marx. Antipode 1981, 13, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, R.; Sunley, P. Making History Matter More in Evolutionary Economic Geography. ZFW–Adv. Econ. Geogr. 2022, 66, 65–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, P.; Shipp, A.J.; Crilly, D.; Jansen, K.J.; Okhuysen, G.A.; Langley, A. Theorizing Time in Management and Organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2025, 50, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knox, P.L. Political, Social and Economic—the Informational City. Information Technology, Economic Restructuring, and the Urban-Regional Process by M. Castells. Geogr. J. 1995, 161, 94–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rignall, K.E. Environmental Politics and the New Rurality. In An Elusive Common: Land, Politics, and Agrarian Rurality in a Moroccan Oasis; Cornell University Press: Ithaca, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 133–160. [Google Scholar]

- Sierk, J. Redefining Rurality: Cosmopolitanism, Whiteness, and the New Latino Diaspora. In Rurality and Education; Routledge: London, UK, 2019; p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, G.A. The Spatiality of Multifunctional Agriculture: A Human Geography Perspective. Geoforum 2009, 40, 269–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.L. Analysis of the Concept of “Rural Area”. Acta Geogr. Sin. 1998, 4, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Halfacree, P.B.B. Migration into Rural Areas: Theories and Issues; Wiley: London, UK, 1998; pp. 1–20. [Google Scholar]

- Poth, C.; Maxwell, J.A. Mixed Methods Design in Historical Perspective: Implications for Researchers. In The Sage Handbook of Mixed Methods Research Design; Sage Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Coleman, M.L.; Ragan, M.; Dari, T. Intercoder Reliability for Use in Qualitative Research and Evaluation. Meas. Eval. Couns. Dev. 2024, 57, 136–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.J. The Reconstruction of Ruralness: A Rights Perspective Based on the “Three-Life Space”. J. Theory Reform 2023, 2, 48–60. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, X.G.; Zhu, H. Advances in Western Rural Sexuality Research. J. Trop. Geogr. 2016, 36, 503–512. [Google Scholar]

- Wiilson, G.A.; Rigg, J. ‘Post-Productivist’ Agricultural Regimes and the South: Discordant Concepts? Prog. Hum. Geogr. 2003, 27, 681–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Song, W.; Tan, H.; Liu, C.; He, S.; Tao, W.; Wang, F.; Gu, H.; Xiao, Y.; Liu, C.; et al. Research on the Exploration of Local Theories, Methods and Paths of Chinese Gentrification. J. Hum. Geogr. 2025, 40, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Fahmi, F.Z.; Sari, I.D. Rural Transformation, Digitalisation and Subjective Wellbeing: A Case Study from Indonesia. Habitat Int. 2020, 98, 102150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Lai, Q. How Does Rural Tourism Affect Farmers’ Subjective Well-Being? The Mediating Role of Farmers’ Livelihoods. Acta Psychol. 2025, 261, 105807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistical Yearbook of Jiangsu Province. Available online: https://tj.jiangsu.gov.cn/col/col87172/index.html (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Zhao, X.L. The Rise of Rural Internet Governance and Institutional Change. J. Henan Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2019, 59, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, J. Gamified Experience Design: A Case Study on China’s Immersive Tourist Blocks in Historic Cities. Front. Sustain. Tour. 2024, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.J.; Yao, J.H. Research on the Community Embedding and Resilience Reorganization Mechanism of Digital Villagers Crossing Urban-Rural Boundaries. J. Southwest Minzu Univ. (Humanit. Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2025, 46, 148–158. [Google Scholar]

- Geertz, C. Local Knowledge: Further Essays in Interpretive Anthropology; Central Compilation & Translation Press: Beijing, China, 2004; p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, J.C. The Moral Economy of the Peasant; Yilin Press: Nanjing, China, 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, Y.; Fei, X.; Luo, L.; Kong, X.; Zhang, J. Social Network Analysis of Heterogeneous Subjects Driving Spatial Commercialization of Traditional Villages: A Case Study of Tanka Fishing Village in Lingshui Li Autonomous County, China. Habitat Int. 2025, 155, 103235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Dong, Y.; Huang, X. Measuring Rurality and Analyzing the Drivers of Rurality in Megacities—A Case Study of Shanghai, China. Land 2024, 13, 1789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Li, F. Rural Revitalization Driven by Digital Infrastructure: Mechanisms and Empirical Verification. J. Digit. Econ. 2024, 3, 103–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquinelli, C.; Trunfio, M. Smart Technologies for Sustainable Tourism Development: Exploring Practices in European Destinations. In Sustainability-Oriented Innovation in Smart Tourism: Challenges and Pitfalls of Technology Deployment for Sustainable Destinations; Pasquinelli, C., Trunfio, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 111–143. [Google Scholar]

- Fei, X.T. From the Soil Beijing; The Commercial Press: Shanghai, China, 2022; pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, C.R. The Construction of Ecological Agriculture and New Productivism in Rural Areas: A Field Investigation in Yuan Village, Jiangxi Province. J. China Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2020, 37, 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.W.; Gu, H.Y. Productivism? Post-Productivism?-on the Changes and Choices of Agricultural Policy Concepts in New China. J. Econ. Syst. Reform 2012, 3, 64–68. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.X.; Shen, M.R.; Zhao, C. Rural Revitalization: The Transformation of Chinese Villages Under Productivism and Post-Productivism. Int. J. Urban Plan. 2014, 29, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Simons, M.A. Beauvoir and the Second Sex: Feminism, Race, and the Origins of Existentialism; Simons, M.A., Ed.; Rowman & Littlefield Publishers: Lanham, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Z.; Yang, A.; Wang, Y. Characteristics, Drivers, and Development Modes of Rural Space Commercialization under Different Altitude Gradients: The Case of the Mountain City of Chongqing. Land 2023, 12, 1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, W.; Wu, Q.; Xu, X. Digital Infrastructure Construction and Improvement of Non-Farm Employment Quality of Rural Labor Force—from the Perspective of Informal Employment. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.