Abstract

The innovative recycling of waste tires into fuel is essential for promoting sustainable development, enhancing waste valorization, and advancing waste-to-energy technologies. For the processing of fr. ≤ 200 °C, separated from the liquid products of the pyrolysis process of waste tires, polycondensation with formaldehyde and extraction with a polar solvent (N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone) was used. Due to the sequential application of these processes, a raffinate product is produced that contains significantly fewer undesirable compounds, such as reactive unsaturated hydrocarbons and aromatics, which can negatively affect gasoline. Additionally, this raffinate demonstrates chemical stability during storage. Due to its operational properties, the obtained raffinate can serve as a high-quality component for gasoline production, which is advisable when mixed with low-octane gas condensate. As a result of compounding, Euro 4 gasoline is obtained with an octane number equal to 93 according to the experimental method. The possibility of effectively using the extract (concentrate of aromatic and unsaturated compounds) as a plasticizer for waterproofing mastic was shown. Overall, the valorization of waste tire pyrolysis processing contributes to waste reduction and is consistent with promoting sustainable industrial innovation by replacing primary petrochemical feedstocks with secondary feedstocks and supporting the development of alternative energy sources.

1. Introduction

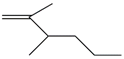

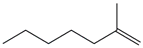

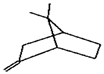

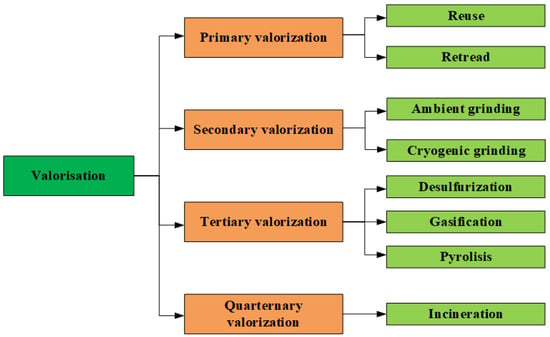

One promising area of research is the thermal destruction of waste tires to obtain liquid products that can be used as alternative fuels [1,2,3,4]. This approach allows one not only to reduce the amount of waste, but also to obtain an additional energy source, which is relevant in the current energy crisis, and contributes to the relatively environmentally friendly implementation of the waste-to-energy movement. Using liquid products of tire pyrolysis as fuel can help reduce dependence on traditional oil resources and greenhouse gas emissions [1,5,6]. Based on our previous research and analysis of the scientific literature, a visualization of the different stages of valorization in recycling waste tires is presented (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Sequential valorization processes involved in waste tire management.

The pyrolysis of waste tires produces three main products: liquid products of pyrolysis of waste tires (LPPT), gas, and solid residue (carbon black) [7]. The liquid pyrolysis products are the main product and can be used as a raw material for producing diesel fuel [8,9] or gasoline [10] after additional purification and/or hydrotreatment. The gases generated in the process have a high energy value and can be used to support the pyrolysis process or as fuel for generators [7,11]. The solid residue contains carbon black, which can be used in producing rubber, paints, lubricants, and as a filler in building materials [7,12].

The production of gasoline and diesel fuel from liquid tire pyrolysis products has several key problems. First, the resulting LPPT contains many resinous and heteroatomic compounds (sulfur, nitrogen, oxygen) [13], complicating its processing and requiring additional purification. Secondly, the fractional composition of LPPT differs from that of traditional oil raw materials, which requires adaptation of technological processes in the oil refining industry [14,15]. There is also the problem of instability of the product’s chemical composition due to the different quality of the input raw materials (tires of other manufacturers and wear) [5,16,17]. In addition, high energy costs for fuel purification and hydrotreatment can reduce the economic efficiency of production [18]. Therefore, it is essential to find an optimal approach to obtaining products from LPPT so that the resulting gasoline meets the norms of Ukrainian and international standards, is economically profitable, and has a simple processing line. Using hydrogenation processes seems technically and financially impossible if the LPPT processing process is implemented in locations remote from hydrogen production facilities (not at a refinery).

The authors are developing alternative methods of processing LPPT. It has been shown that the separation of gasoline fractions makes it possible to obtain a commercial product that fully meets the requirements for commercial boiler fuels [14]. The study of the possibility of processing gasoline fractions without using hydrogenation technologies has proved the possibility of obtaining effective road bitumen and aromatic compound concentrate additives. Bitumen modifiers were obtained by polycondensation of gasoline with formaldehyde [13]. The concentration of aromatic compounds was obtained by extraction using polar solvents [19]. The obtained gasoline fractions (unreacted substances after reactions with formaldehyde and the raffinate product after extraction) contained fewer unsaturated and aromatic compounds and undesirable gasoline components.

On the other hand, the above products still did not meet the requirements for gasoline, primarily in terms of density and aromatic compounds. Therefore, this article aims to investigate the possibility of combining two methods of gasoline fractions purification from undesirable components (aromatic, hetero-atomic, and unsaturated compounds) and the effective use of the resulting products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

The raw material for the study was the gasoline fr. ≤ 200 °C (GF), which was separated from the liquid pyrolysis products. The yield of the fr. ≤ 200 °C is 31.5 wt.% of the LPPT.

The fr. ≤ 180 °C of gas condensate (GC) produced at the Proletarska gas treatment plant (Magdalynivskyi district, Dnipropetrovska oblast, Ukraine) was used as a low-octane gasoline component. The yield of the fr. ≤ 180 °C is 94.73 wt.% of the GC. The characteristics of fr. ≤ 200 °C and fr. ≤ 180 °C GC is given in Table 1, and the fractional composition is in Table 2.

Table 1.

Physicochemical characteristics of fr. ≤ 200 °C and fr. ≤ 180 °C GC.

Table 2.

Fractional composition of fr. ≤ 200 °C and fr. ≤ 180 °C GC.

The polyurethane polymer was used as a one-component waterproofing mastic of the polyurethane-polyurea type. The main characteristics of the polyurethane polymer are a density of 1.412 g/cm3, relative elongation at break up to 400%, water absorption of 0.9%, and drying time of 120 min.

To modify the mastic, we used a functional filler, taurite shale from the TS-D brand—a fine black powder. The fraction of 5 microns is up to 90%.

2.2. Methods

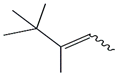

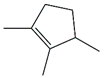

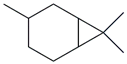

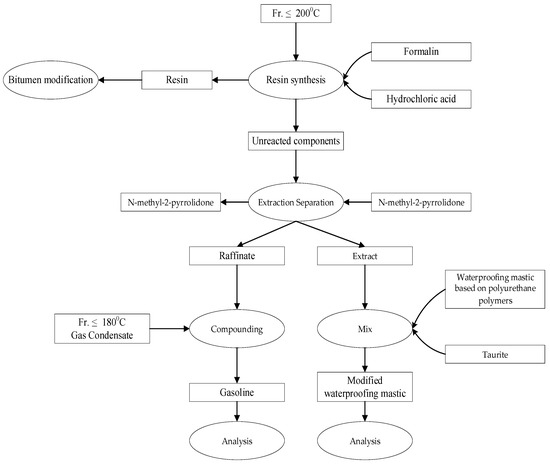

The general scheme of the research is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

General structure of the research approach.

2.2.1. Resin Synthesis

The resins were synthesized by polycondensation of formaldehyde with a fr. ≤ 200 °C using hydrochloric acid as a catalyst.

As noted above, in previous studies [13,21,22], the authors studied the processes of obtaining formaldehyde-containing resins using liquid fractions obtained during thermal transformations of organic raw materials. At the same time, the influence of each factor on the process of synthesis of formaldehyde resins was established. It was also established [13] that it is advisable to use fr. ≤ 200 °C as the starting raw material (there is no need to divide this fraction into narrower ones). The optimal conditions that ensure the maximum resin yield can be considered: synthesis temperature—100 °C, duration—120 min, formalin content—7.5 wt.% of raw materials, and catalyst—3 wt.% of raw materials. Under these factors, the synthesis of resins presented in this manuscript was carried out.

The initial fr. ≤ 200 °C was loaded into a metal cylindrical reactor, after which a previously prepared reaction mixture was added in the required ratio of formalin and hydrochloric acid. The metal reactor was hermetically sealed and immersed in a preheated oil bath, with the start of the synthesis process being recorded.

After the process, the metal reactor was cooled to room temperature. The resulting product mixture was first subjected to atmospheric distillation to remove water and unreacted components, and then kept in a vacuum oven at 150 °C for 1.5 h. The material balance of the products obtained was calculated by weighing them.

2.2.2. Extraction Separation

Extraction separation was performed to isolate aromatic and unsaturated compounds from the fraction with fr. ≤ 200 °C and unreacted components of fr. ≤ 200 °C. The extraction process methods and solvent separation were adopted following Ref. [23].

N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) and diethylene glycol (DEG) were used as solvents. According to previously conducted studies [19,22], the optimal ratio of raw material to solvent was selected: raw material: NMP—1:1.5, raw material: DEG—1:15. At a lower amount of solvent, it is not possible to separate polar compounds in sufficient quantities (undesirable in gasolines), and with an increase in its amount, the desired components begin to pass into the extract, namely, alkane, naphthene and/or alkane/naphthene-containing structures. These are the ratios chosen in the studies described in this manuscript.

The extraction was carried out in a separating funnel at ambient temperature and with continuous stirring. After that, the mixture was allowed to settle until the raffinate and extract solutions completely separated (about 20 min). The lower layer, the extract, was collected using the separating funnel. NMP was then separated from the extract and raffinate based on its solubility in water. The obtained raffinate and extract were dried to eliminate any residual water.

2.2.3. Method of Modification of Waterproofing Mastic with GF Extract

GF extract was added to the waterproofing mastic based on polyurethane polymers as a 5–10 wt.% plasticizer and stirred at 25 °C for 30 min at Re = 1200 until a homogeneous mass was formed. With further modification with taurite, the functional filler taurite in the amount of 3–9% by weight was added to the waterproofing mastic obtained by plasticizing with the GF extract and stirred at a temperature of 25 °C for 30 min at Re = 1200 until a homogeneous mass was formed.

2.3. Methods of Analysis

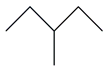

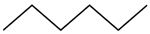

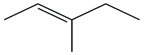

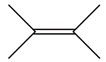

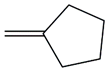

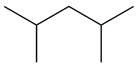

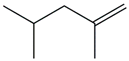

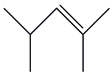

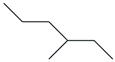

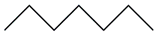

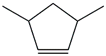

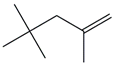

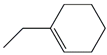

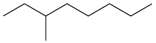

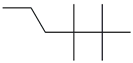

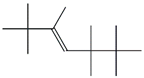

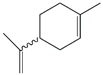

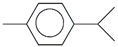

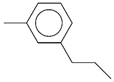

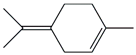

2.3.1. Gas Chromatography with Mass Spectrometric Detection

Gas chromatography analysis was performed on a Shimadzu GC-MS-QP 2020 equipped with an Rtx-5MS capillary column-crossband 5% diphenyl 95% dimethyl polysiloxane (length—30 m, inner diameter—0.25 mm, stationary phase film thickness—0.25 μm) from Restek. For more details on the processing of chromatography and analysis results, see Ref. [13]. Only the most probable isomeric structures, identified using the MS search file system and considering the retention indices for non-polar columns from the NIST database [24], are presented in the manuscript.

2.3.2. IR Spectroscopy

FTIR spectra of the samples were obtained using a PerkinElmer Spectrum Two spectrometer using a Universal ATR accessory with a diamond crystal for measurement. The largest differences between the IR spectra of the raw materials and products were observed in the ranges 3050–2750 cm−1, 1650–1300 cm−1, and 950–650 cm−1, indicating the presence of specific functional groups. A detailed procedure for processing IR spectra for quantitative analysis is given in Ref. [13].

2.3.3. Determination of Physical and Technological Indicators

Determination of physical and technological parameters for fr. ≤ 200 °C, fr. ≤ 180 °C GC, and the obtained gasoline were determined according to standardized methods: saturated vapor pressure—according to Ref. [25]; density—according to Ref. [26]; copper plate test—according to Ref. [27]; presence of water-soluble acids and alkalis using indicators—according to Ref. [28]; sulfur content—according to Ref. [29]; refractive index—according to Ref. [30]; bromine number—according to Ref. [31]; fractional composition—according to Ref. [32].

The determination of physical and technological parameters of polyurethane polymers was carried out according to standardized methods: Shore hardness—according to Ref. [33], density using the hydrostatic method—according to Ref. [34], relative elongation at the break—according to Ref. [35], water absorption—according to Ref. [36].

The determination of the mass fraction of carbon and hydrogen from a single portion of an organic substance is carried out by burning it to carbon dioxide and water in an unfilled quartz tube in an atmosphere of a significant excess of pure oxygen in the presence of silver-plated pumice and a platinum catalyst according to the modified Pregl method [37].

To determine nitrogen by the modified Dumas method, a sample of organic matter was used, which was mixed with ground nickel oxide and burned in an atmosphere of pure carbon dioxide. The nitrogen contained in the organic matter was converted mainly into molecular nitrogen, which was displaced by blowing with carbon dioxide and then absorbed by a concentrated solution of potassium hydroxide [37].

The formula determined the oxygen content:

O = 100-C-H-S-N

The extended Mendeleev formula determined the higher calorific value of fuel:

where C, H, S, O, N—content of carbon, hydrogen, sulfur, oxygen, nitrogen, respectively, wt.%.

Q = 339.4 × C + 1256.8 × H + 108.9 × (S-O-N)

2.3.4. Cost-Effectiveness Assessment

The equation determined the total amount of material resources used (3) [38]:

where —total direct material costs, USD;

j = 1…m—types of material resources/products;

—quantity of consumed material resource of the jth type in physical terms, t, m3, kWh;

—cost of jth type of material resources, USD/hour.

The equation determined the cost of marketable products (4) [38]:

where Qi—quantity of commodity products of the i-th type in physical terms, tons;

Pi—price of commodity products of the i-th type, USD/t.

The material consumption coefficient was determined by Equation (5) [38]:

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of fr. ≤ 200 and the Feasibility of Its Use

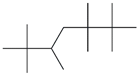

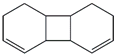

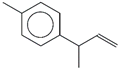

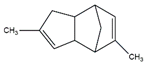

The chromatographic analysis was performed at fr. ≤ 200 °C. The results of chromatography are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Chromatographic analysis fr. ≤ 200 °C.

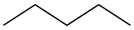

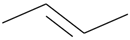

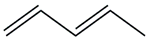

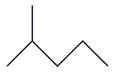

Table 1 and Table 2 show that the fr. ≤ 200 °C does not meet the requirements for gasoline regarding specific indicators, primarily density. A high bromine number also characterizes it. These data are confirmed by the results of chromatographic analysis, which indicate a high content of aromatic compounds (including benzene, the content of which is 2.96 wt.%) and unsaturated compounds, the presence of which is undesirable in commercial gasoline.

3.2. Obtaining Commercial Gasoline

3.2.1. Polycondensation with Formaldehyde

To obtain additives to bitumen and reduce aromatic and unsaturated compounds in parallel, polycondensation of fr. ≤ 200 °C with formaldehyde was used. The material balance of polycondensation under optimal conditions is shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Material balance of polycondensation at fr. ≤ 200 °C.

The resulting resins can be used as adhesive modifiers for bitumen [13].

The characteristics of the unreacted components are shown in Table 5.

Table 5.

Physical and chemical properties of unreacted components.

The obtained results confirm that the reactions of the GF components with formaldehyde reduce the density, bromine number, and refractive index. Thus, the process results in a decreased presence of aromatic and unsaturated structural components. This indicates the reaction of formaldehyde with arene components and the interaction of olefins with each other and/or polycondensation products.

3.2.2. Extraction

The extraction process was carried out to remove undesirable compounds in gasoline (condensed aromatics, unsaturated, heteroatomic, etc.). Refineries traditionally use polar solvents for the extraction process, most commonly NMP, diethylene glycol (DEG), furfural, and phenol [39].

For the environmental assessment of industrial solvents, Table 6 presents an analysis of maximum permissible concentrations (MPCs) in the air, threshold limit values of time-weighted average (TLV-TWA), and immediate danger to life or health (IDLH) according to Refs. [40,41,42,43].

Table 6.

Permissible content and effects on the human body.

As shown in Table 6, phenol and furfural are the most hazardous substances among the analyzed solvents. At the same time, N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP) is characterized by an average level of toxicity and solubility similar to phenol, but unlike it, it also has good selectivity [39].

In our studies, we used DEG as one of the most affordable and relatively environmentally friendly solvents and NMP as one of the most effective solvents. Table 7 and Table 8 compare the effectiveness of DEG and NMP.

Table 7.

Material balance of extraction processes using DEG and NMP.

Table 8.

Physical and chemical characteristics of extraction products.

As seen from Table 7, the yield of the obtained extract is higher when using NMP, which is characterized by its much better solubility than DEG and approximately the same selectivity.

Table 8 shows that the obtained extracts and raffinates at the studied ratios have similar physicochemical properties, except for the bromine number, confirming that DEG is more selective for unsaturated compounds in contrast to NMP.

From a technological point of view, the extraction separation process in the presence of N-methyl pyrrolidone is somewhat more complicated since the solvent oxidizes very quickly when in contact with air. However, the volume of reaction equipment will be much smaller.

Because of the above, it was decided to conduct further research using NMP as a solvent in the extraction process since it has a significantly better solubility. Its advantages include smaller equipment and less water for its separation after extraction.

An extraction process separated the unreacted components into an extract and a raffinate to obtain gasoline components (raffinate) and a concentrate of aromatic compounds (extract). The material balance of the extraction with N-methylpyrrolidone under the proposed conditions is presented in Table 9.

Table 9.

Material balance of the extraction and separation of unreacted components.

The characteristics of the obtained substances are presented in Table 10.

Table 10.

Physicochemical properties of the obtained raffinate and extract.

As shown in Table 10, the obtained raffinate can only be used as a component of gasoline due to its too-high density, indicating a significant content of aromatic compounds, and bromine number, which reflects the low abundance of unsaturated compounds. All analytical indicators for the extract exhibited elevated values, indicating that a significant amount of aromatic and unsaturated compounds were transferred to the extract.

3.2.3. Obtaining Gasoline

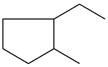

As the second component for compounding, condensate from gas fields was used, which is characterized by low density and almost no aromatic compounds.

The compounding of fr. ≤ 180 °C of GC and raffinate was carried out based on the objective of obtaining gasoline with a satisfactory density and maximum use of raffinate. The material balance associated with the compounding is summarized in Table 11.

Table 11.

Material balance of compounding.

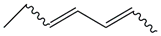

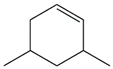

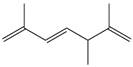

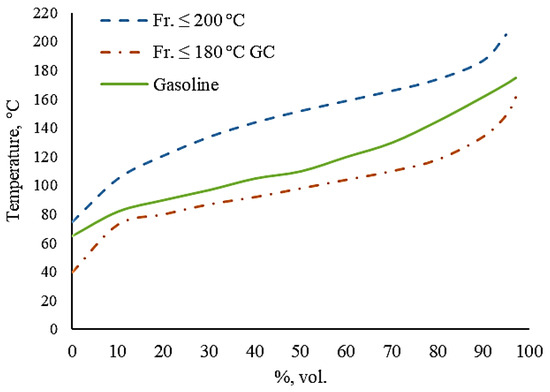

The characteristics of the obtained gasoline are shown in Table 12, and the fractional composition is shown in Figure 3.

Table 12.

Physicochemical characteristics of the obtained gasoline (a mixture of raffinate gasoline and FR ≤ 180 °C GC).

Figure 3.

Fractional composition of the obtained gasoline.

Table 12 and Figure 3 show that the obtained gasoline meets the main indicators of the regulatory documents for Euro 4 gasoline with an octane number of 92. If additional oxygenates are used or the proportion of raffinate in the mixture is increased, Euro 4 gasoline with an octane rating of 95 can be produced. The fractional composition of the obtained gasoline is heavier than gas condensate, but lighter than raffinate.

The ultimate analysis of fr. ≤ 200 °C and the obtained gasoline is given in Table 13.

Table 13.

The ultimate analysis of fr. ≤ 200 °C.

Table 13 shows that the fr. ≤ 200 °C comprises N-containing and O-containing components. After the processing, the content of N- and O-containing compounds in the resulting gasoline decreased significantly (the nitrogen content decreased by almost 1000 times). The sulfur content was also reduced by almost half. Accordingly, we can declare that the obtained gasoline is environmentally friendly and predicts a reduction in SO2 emissions and NOx reduction during its use (compared to the feedstock). The almost complete absence of nitrogen compounds in the obtained gasoline also indicates the absence of NMP and the effectiveness of the methodology proposed by the authors for separating the solvent from the extraction products. Due to the extraction of oxygen compounds, the obtained gasoline has a higher calorific value than fr. ≤ 200 °C, which improves the efficiency of its use in engines.

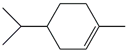

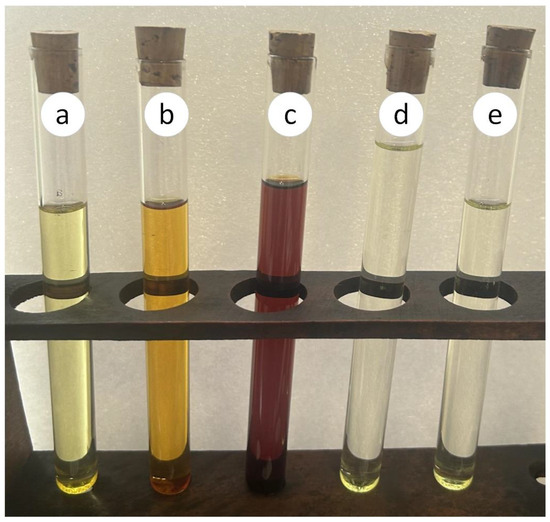

Figure 4 shows the change in color of the fr. ≤ 200 °C and the obtained gasoline during a certain storage period. The obtained gasoline (in contrast to the fr. ≤ 200 °C before its processing) does not change color during storage, which indicates the absence of compounds capable of polymerization and compaction, and the ability to maintain its properties under normal conditions (i.e., gasoline stability).

Figure 4.

General view of the fr. ≤ 200 °C and the obtained gasoline: a—fr. ≤ 200 °C after its separation from the LPPT; b—fr. ≤ 200 °C after separating from the LPPT and 30 days of storage; c—fr. ≤ 200 °C after separating from the LPPT and one year of storage; d—obtained gasoline; e—obtained gasoline after one year of storage.

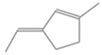

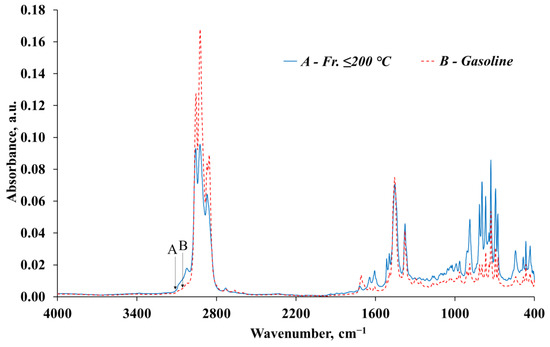

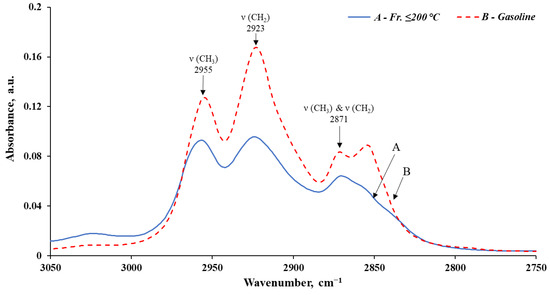

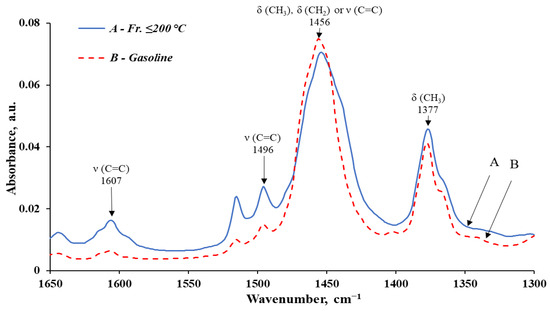

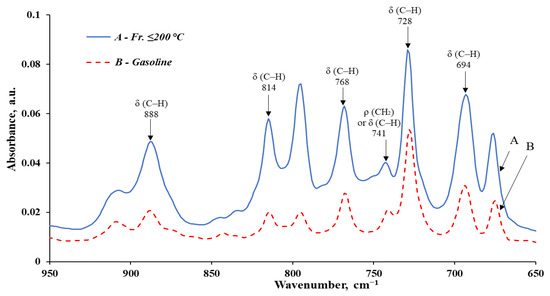

For a detailed analysis of the distribution of hydrocarbon structures, infrared spectroscopy of the feedstock (fr. ≤ 200 °C) and the obtained gasoline was also performed.

In Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8, four IR spectra are presented, and spectral bands are identified in Table 14.

Figure 5.

Infrared spectra of the fr. ≤ 200 °C and the obtained gasoline.

Figure 6.

Infrared spectra of the fr. ≤ 200 °C and the obtained gasoline, in the interval 3050–2750 cm−1.

Figure 7.

Infrared spectra of the fr. ≤ 200 °C and the obtained gasoline, in the interval 1650–1300 cm−1.

Figure 8.

Infrared spectra of the fr. ≤ 200 °C and the obtained gasoline, in the interval 950–650 cm−1.

Table 14.

IR spectra fractions: ≤200 °C and gasoline.

The analysis of IR spectroscopy data shows a significant reduction in the content of compounds prone to compaction, polymerization, and formation of deposits and soot during combustion in engines (aromatics and unsaturated) in the obtained gasoline (compared to the initial fr. ≤ 200 °C).

The summarized material balance of gasoline production from fr. ≤ 200 °C is given in Table 15.

Table 15.

Consolidated material balance of gasoline production from fr. ≤ 200 °C.

Table 15 shows that obtaining gasoline at 126.84 wt.% is possible by raw materials, of which 44.39 wt.% by raw materials are components of the initial fr. ≤ 200 °C. It is also possible to obtain related products: resin—8.59 wt.% on raw materials, which can be used as an adhesive additive to bitumens [7,13], and extract 48.33 wt.% on raw materials, the application of which is discussed below.

3.3. Application of the Extract

The obtained extract consists of polar and polarization-prone compounds and aromatic, unsaturated, and heteroatomic structures. Therefore, it can be assumed to be used as a plasticizer or for producing certain aromatic hydrocarbons.

The effectiveness of using the obtained GF extract as a plasticizer for waterproofing mastic based on polyurethane polymers was studied. The target indicators of the modification process are increasing the elasticity, water resistance, and adhesive properties of polyurethane polymers. The effect of the extracted content on the specified target indicators in the range of 5–20 wt.% was studied.

Due to the plasticizing effect in the range of 5–10 wt.% of the extract of polyurethane polymers, when a more elastic structure is formed, the relative elongation at break, adhesive properties, Shore hardness, and water absorption decrease (Table 16). This is consistent with the data in Ref. [44]. At the same time, the drying time of the modified compositions increases by 10–25 min, and the surface layer of structured modified polyurethane polymers becomes more homogeneous and practically glossy compared to the original one.

Table 16.

The effect of the extract on the technological and operational properties of polyurethane polymers.

With an increase in the extract content of polyurethane polymers to 20 wt.%, on the contrary, the target technological and operational indicators decrease, and the drying time of the composition increases sharply by almost 2.5 times to 290 min. This indicates that the rational extract content of polyurethane polymers is 10 wt.%. With an increase in the extract content above 10 wt.%, it begins to behave not as a plasticizing agent, but as a solvent, which does not fully allow polyurethane polymers to form a cross-linked elastomeric structure.

The modification of polyurethane polymers with the extract at its content of 10 wt.% can make it possible to technologically carry out a compatible modification with effective functional dispersed fillers; further studies aimed to use a functional modifier of an environmentally friendly filler—taurine TS-D—at its content from 3 to 9 wt.% in polyurethane elastomeric materials, as shown in Ref. [45].

The results of Table 17 show that due to the joint modification of polyurethane polymers when using 10 wt.% of the extract about polyurethane polymers and 6 wt.% of taurite, even more effective plasticization is observed, which is accompanied by a further increase in the relative elongation at break, adhesive properties, and a decrease in Shore hardness and water absorption [44]. At the same time, the drying time of the joint-modified compositions is reduced by 10–25 min, and the surface layer of structured modified polyurethane polymers becomes more homogeneous and practically glossy compared to the original one.

Table 17.

The influence of taurite on the technological and operational properties of polyurethane polymers modified with the extract.

Thus, we can conclude that it is appropriate to simultaneously modify the polyurethane polymer with extract and taurite in amounts of 10 wt.% and 6 wt.%, respectively.

3.4. The Economic Efficiency of the Researched Processes

Implementing sustainable development goals involves the introduction of cost-effective standards for a wide range of technologies, which can reduce electricity consumption in industry worldwide by 14% [46]. Therefore, Table 17 and Table 18 show a comparison of the main costs (costs of raw materials and reagents, energy costs, etc.) for the studied processes of pyrolysis gasoline processing with the “traditional” process (hydrotreating). The methodology for determining economic efficiency usually compares the results obtained with the costs incurred. A more detailed analysis is possible only if similar production facilities or a pilot plant exist. The main factor in achieving economic efficiency is considered to be a decrease in energy intensity. It is they, from the point of view of modern trends in technology development, that make it possible to assess qualitative characteristics without considering the amount of capital investment and the level of labor productivity.

Table 18.

Indicators of economic efficiency assessment.

The amount of raw materials, products, reagents, and specific energy costs in the economic efficiency calculations of the studied processes was taken based on the data in Table 14 and Ref. [47]. The prices of industrial raw materials, reagents, products, etc., used in the calculations are a commercial secret or, at present, are unknown (due to the authors obtaining new components of fuels, bitumens, and lubricants during the research). Table 18 shows the approximate cost of the studied raw materials, products, reagents, etc., based on the experience of cooperation with Ukrainian oil refineries and small-scale waste processing plants. The prices of energy resources in Ukraine (electricity, steam, return water, and fuel gas) and the wholesale cost of 1 ton of commercial gasoline with an octane rating of 95 (A-95) were taken based on data from Refs. [48,49,50].

The assessment of economic efficiency by determining the material consumption indicators (Table 19) indicates the efficiency of the studied methods of processing pyrolysis gasoline (fr. ≤ 200 °C) in comparison with the “traditional” processing of pyrolysis gasoline (fr. ≤ 200 °C) by hydrorefining. The material resources used make up the largest share of the production structure of commodity products. The material consumption indicator of the studied processes is option I—0.35 (obtaining three types of products) and option II—0.29 (obtaining two types of products). The efficiency of the process (option I) indicates the rationality of using the studied methods of processing gasoline fractions of pyrolysis WT.

Table 19.

Assessment of economic efficiency by determining material consumption indicators.

4. Conclusions

The fr. ≤ 200 °C, which is separated from the LPPT, is characterized by a high content of aromatic and unsaturated compounds. Such gasolines have unsatisfactory environmental properties and low stability during storage. A raffinate product with a lower concentration of aromatic and unsaturated compounds, relative to the original gasoline fraction, can be obtained through treatment with formaldehyde (catalyzed by hydrochloric acid) and subsequent extraction using N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone. As a result of mixing the raffinate with a low-octane component (condensate from gas fields) in a ratio of 35:65 (mass parts), obtaining gasoline in the amount of 126.84 wt.% is possible per 100 wt.% of the original fr. ≤ 200 °C. According to the main indicators, this gasoline is characterized by an octane number of 93 and meets the requirements of regulatory documents for the “Euro 4” brand. The obtained extract (48.33 wt.% on the initial fr. ≤ 200 °C) is expedient to add to the polyurethane mastic and taurite in amounts, respectively, 10 wt.% and 6 wt.% on 100% of the polymer. In this case, effective plasticization of the mastic occurs, which is accompanied by an increase in the relative elongation at break, improvement of adhesive properties, and a decrease in Shore hardness and water absorption. In this case, the drying time of the jointly modified compositions is reduced by 10–25 min, and the surface layer of structured modified polyurethane polymers becomes more homogeneous compared to the initial one.

Applying the proposed technologies for processing liquid pyrolysis products of used tires will allow the obtaining of high-quality, marketable products without introducing hydrogenation technologies. This, in turn, will allow the building of relatively small-capacity tire recycling plants directly near their storage locations, improving economic feasibility and valorizing waste recycling processes in general.

Given the instability of the pyrolysis feedstock (WT), changes in the component composition of the resulting gasoline fractions can also be predicted, which can be considered a limitation of this study. The possible challenges that the research findings might encounter in the future will be possible deviations in the performance properties of the resulting products during their transportation, storage, and further use. Therefore, the authors plan to conduct engine performance tests of the resulting gasoline and deepen the study of its stability during storage. For a more comprehensive and complete evaluation of the polyurethane polymers modified with extract and taurite, long-term studies are underway to determine the durability of the composites concerning the influence of environmental factors in the form of ultraviolet radiation and cyclic thermal loading.

Overall, it can be argued that the proposed LPPT recycling approach embodies the principles of waste valorization by converting hazardous pyrolysis liquids into functional fuels and binder additives. Furthermore, it contributes to achieving sustainable development goals by promoting resource efficiency, reducing environmental pollution, and enabling circular material use.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.P. and D.M.; methodology, S.P. and Y.L.; software, B.K.; validation, S.P. and D.M.; formal analysis, S.P., V.L. and A.Y.; investigation, V.L. and Y.L.; resources, S.P.; data curation, S.P.; writing—original draft preparation, S.P., V.L., A.Y. and Y.L.; writing—review and editing, S.P. and B.K.; visualization, B.K. and Y.L.; supervision, S.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no known competing financial interest or personal relationship that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Zhang, M.; Qi, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, M.; Li, J.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, S.; He, J.; Cao, H.; Tao, X.; et al. A review on waste tires pyrolysis for energy and material recovery from the optimization perspective. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 199, 114531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano, D.; Horvat, A.; Batuecas, E.; Abelha, P. Waste tyres valorisation through gasification in a bubbling fluidised bed: An exhaustive gas composition analysis. Renew. Energy 2022, 200, 1438–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Qadri, A.A.; Ahmed, U.; Ahmad, N.; Jameel, A.G.A.; Zahid, U.; Naqvi, S.R. A review of hydrogen generation through gasification and pyrolysis of waste plastic and tires: Opportunities and challenges. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 77, 1185–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, D.B.; Ganesan, M.C. A Review on Valorisation of Waste Tire with Lignocellulose Catalytic Co-Pyrolysis to High Value Products. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, in press. [CrossRef]

- Ramani, B.; Anjum, A.; Bramer, E.; Dierkes, W.; Blume, A.; Brem, G. A comprehensive study on the effect of the pyrolysis temperature on the products of the flash pyrolysis of waste tires. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2025, 13, 115468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashamfirooz, M.; Dehghani, M.H.; Khanizadeh, M.; Aghaei, M.; Bashardoost, P.; Hassanvand, M.S.; Hassanabadi, M.; Momeniha, F. A systematic review of the environmental and health effects of waste tires recycling. Heliyon 2025, 11, e41909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyshyev, S.; Lypko, Y.; Demchuk, Y.; Kukhar, O.; Korchak, B.; Pochapska, I.; Zhytnetskyi, I. Characteristics and applications of waste tire pyrolysis products: A review. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2024, 18, 244–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewang, Y.; Sharma, V.; Singla, Y.K. A critical review of waste tire pyrolysis for diesel engines: Technologies, challenges, and future prospects. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 43, e01291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suiuay, C.; Katekaew, S.; Senawong, K.; Junsiri, C.; Srichat, A.; Laloon, K. Pilot-scale production of gasoline and diesel-like fuel from natural rubber scrap: Fractional condensation of pyrolysis vapors and optimization of pyrolysis parameters by using response surface methodology (RSM). Fuel 2024, 364, 131059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moonsin, P.; Roschat, W.; Phewphong, S.; Watthanalao, S.; Maneerat, B.; Arthan, S.; Thammayod, A.; Leelatam, T.; Yoosuk, B.; Janetaisong, P.; et al. The physicochemical properties of liquid biofuel derived from the pyrolysis of low-quality rubber waste. Case Stud. Chem. Environ. Eng. 2025, 11, 101085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajczyńska, D.; Krzyżyńska, R.; Ghazal, H.; Jouhara, H. Experimental investigation of waste tyres pyrolysis gas desulfurization through absorption in alkanolamines solutions. Int. J. Hydrogen. Energ. 2024, 52, 1006–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jankovská, Z.; Peikertová, P.; Tokarský, J.; Matějová, L. Carbons prepared by microwave co-pyrolysis of waste scrap tyres and corn cob: Effect of cation size and charge on xylene adsorption. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 114374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyshyev, S.; Lypko, Y.; Korchak, B.; Poliuzhyn, I.; Hubrii, Z.; Pochapska, I.; Rudnieva, K. Study on the composition of gasoline fractions obtained as a result of waste tires pyrolysis and production bitumen modifiers from it. J. Energy Inst. 2024, 114, 101598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyshyev, S.; Lypko, Y.; Chervinskyy, T.; Fedevych, O.; Kułażyński, M.; Pstrowska, K. Application of tyre derived pyrolysis oil as a fuel component. S. Afr. J. Chem. Eng. 2023, 43, 342–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, N.; Nahil, M.A.; Williams, P.T. Co-pyrolysis of waste plastics and tires: Influence of interaction on product oil and gas composition. J. Energy Inst. 2025, 118, 101908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodak, A.; Haponiuk, J.; Wang, S.; Formela, K. Waste tire rubber with low and high devulcanization level prepared in the planetary extruder. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2025, 43, e01193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saputra, R.; Walvekar, R.; Khalid, M.; Mubarak, N.M.; Sillanpää, M. Current progress in waste tire rubber devulcanization. Chemosphere 2021, 265, 129033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straka, P.; Auersvald, M.; Vrtiška, D.; Kittel, H.; Šimáček, P.; Vozka, P. Production of transportation fuels via hydrotreating of scrap tires pyrolysis oil. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 460, 141764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pychyev, S.; Lypko, Y.; Korchak, B.; Niavkevich, M.; Rudnieva, K. Investigation of the extraction separation of gasoline fractions obtained as a result of pyrolysis of waste tires. J. Coal Chem. 2023, 6, 28–37. [Google Scholar]

- DSTU 7687:2015; Euro Motor Gasoline. Technical Conditions. UkrNDNC SE: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2015.

- Pyshyev, S.; Demchuk, Y.; Gunka, V.; Sidun, I.; Shved, M.; Bilushchak, H.; Obshta, A. Development of mathematical model and identification of optimal conditions to obtain phenol-cresol-formaldehyde resin. Chem. Chem. Technol. 2019, 13, 212–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lypko, Y. Development of Methods for the Use of Liquid Products of Thermal Destruction of Waste Tires. 2024. Available online: https://lpnu.ua/sites/default/files/2024/radaphd/27676/lypko-disertaciya.pdf (accessed on 24 May 2024).

- Chen, F.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Gao, J.; Hao, T.; Xu, C. High efficiency separation of olefin from FCC naphtha: Influence of combined solvents and related extraction conditions. Fuel Process. Technol. 2020, 208, 106497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST). Chemistry WebBook: Name Search. Available online: https://webbook.nist.gov/chemistry/name-ser/ (accessed on 30 December 2024).

- DSTU EN 13016-1:2012; Petroleum Products—Liquid. Saturated Vapor Pressure. Part 1: Determination of the Saturated Vapor Pressure with Air Content (ASVP) and Calculation of the Equivalent Dry Vapor Pressure (DVPE) (EN 13016-1:2007, IDT). UkrRIORI “MASMA”: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2012.

- DSTU 7261:2012; Technical Chemical Products. Methods for Determining the Density of Liquids. Technical Committee for Standardization “Analysis of Gases, Liquids and Solids” (TC 122), State Enterprise “All-Ukrainian State Scientific and Production Center for Standardization, Metrology, Certification and Consumer Rights Protection” of the Ministry of Economic Development of Ukraine (“Ukrmetr-teststandart”): Kyiv, Ukraine, 2012.

- DSTU EN ISO 2160:2012; Petroleum Products. Method for Determination of the Corrosive Effect on Copper Plate (EN ISO 2160:1998, IDT). UkrRIORI “MASMA”: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2012.

- GOST 6307-75; Petroleum Products. Method for Determining the Presence of Water-Soluble Acids and Alkalis. With Amendment No. 1. Technical Committee for Standardization “Standardization of Refined Petroleum Products and Petrochemicals” (TC 38): Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022.

- DSTU EN ISO 20884:2012; Petroleum Products. Method for the Determination of Sulfur Content in Motor Vehicle Fuels by Wavelength Dispersive X-Ray Fluorescence Spectrometry (EN ISO 20884:2011, IDT). UkrRIORI “MASMA”: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2012.

- DSTU GOST 18995.2:2009; Chemical Liquid Products. Method for Determination of Refractive Index (GOST 18995.2-73, IDT). UkrNDNC SE: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2009.

- Auersvald, M.; Staš, M.; Šimáček, P. Electrometric bromine number as a suitable method for the quantitative determination of phenols and olefins in hydrotreated pyrolysis bio-oils. Talanta 2021, 225, 122001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GOST 2177-99; Petroleum Products. Methods for Determining Fractional Composition. Interstate Council for Standardization, Metrology and Certification: Minsk, Belarus, 1999.

- DSTU EN ISO 868:2017; Plastics and Ebonite—Determination of Indentation Hardness Using a Durometer (Shore Hardness) (EN ISO 868:2003, IDT.; ISO 868:2003, IDT). International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- DSTU EN ISO 1183-1:2022; Plastics—Methods for Determining the Density of Non-Cellular Plastics—Part 1: Immersion, Liquid Pycnometer and Titration Methods (EN ISO 1183-1:2019, IDT.; ISO 1183-1:2019, IDT). UkrNDNC SE: Kyiv, Ukraine, 2022.

- DSTU EN ISO 527-2:2018; Plastics—Determination of Tensile Properties—Part 2: Test Conditions for Plastics Manufactured by Molding and Extrusion (EN ISO 527-2:2012, IDT.; ISO 527-2:2012, IDT). Technical Committee for Standardization “Rubbers, Rubber and Rubber Products” (TC 128): Kyiv, Ukraine, 2018.

- DSTU EN ISO 291:2017; Plastics—Standard Atmospheric Conditions for Conditioning and Testing (EN ISO 291:2008, IDT.; ISO 291:2008, IDT). Technical Committee for Standardization “Rubbers, Rubber and Rubber Products” (TC 128): Kyiv, Ukraine, 2017.

- De Groot, P.A. Chapter 4—Carbon. In Handbook of Stable Isotope Analytical Techniques; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 229–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mykytyuk, V.; Flys, V. Factors affecting the efficiency of the use of material resources in the enterprise and ways to increase it. Her. Econ. 2024, 1, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speight, J.G. Solvent Processes in Refining Technology; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- On Approval of State Medical and Sanitary Standards for the Permissible Content of Chemical and Biological Substances in the Atmospheric Air of Populated Areas. Order 10.05.2024 No. 813 Ministry of Health of Ukraine. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/z0763-24#n9 (accessed on 19 June 2024).

- On Approval of State Medical and Sanitary Standards for the Permissible Content of Chemical and Biological Substances in the Air of the Working Area. Order 9 July 2024 No. 1192 Ministry of Health of Ukraine. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/laws/show/z1107-24#Text (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- ACGIH Data Hub—2025. Available online: https://www.acgih.org/data-hub/ (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Immediately Dangerous to Life or Health (IDLH) Values. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/idlh/intridl4.html (accessed on 26 February 2021).

- Cherkashina, A.; Lavrova, I.; Lebedev, V. Development of a bitumen-polymer composition, resistant to atmospheric influences, based on petroleum bitumen and their properties study. Mater. Sci. Forum 2021, 1038, 352–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahirwar, D.; Telang, A.; Purohit, R.; Namdev, A. A short review on polyurethane polymer composite. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 62, 3804–3810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. Available online: https://www.undp.org/uk/ukraine/tsili-staloho-rozvytku (accessed on 1 March 2021).

- Meyers, R.A. Handbook of Petroleum Refining Processes, 4th ed.; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- On Establishing the Tariff for Electricity Transmission Services of NPC “UKRENERGO” for 2025. Available online: https://zakon.rada.gov.ua/rada/show/v2200874-24#Text (accessed on 19 December 2024).

- Actual Sales Price of Natural Gas for January 2025. Available online: https://me.gov.ua/Documents/Detail/53a2e159-7d90-4901-b6ca-697e54e305b0?lang=uk-UA&title=FaktichnaTsinaRealizatsiiPrirodnogoGazuNaSichen2025 (accessed on 6 February 2025).

- Price Indices. Available online: https://index.minfin.com.ua/ua/markets/fuel/ (accessed on 25 April 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).