Abstract

Food waste is a pressing global problem with significant environmental, economic and social impacts. This review examines the state of food waste management in Serbia and contextualizes the challenges and opportunities in a global and EU framework. In the Republic of Serbia, an estimated 247,000 tons of food is wasted annually, indicating critical gaps in waste management infrastructure, consumer awareness and missing legislation. While existing policies address general waste management, there is a lack of targeted measures for food waste prevention and resource recovery. The overview recommends aligning Serbian policy with an EU legislative frame, introducing extended producer responsibility and promoting public–private cooperation to improve food donation and recycling. This is the first comprehensive study specifically addressing food waste management in Serbia and assessing its compliance with European and global best practices. By comparing Serbia’s current status with established international models, this paper identifies critical gaps and proposes actionable strategies to improve the efficiency and sustainability of the food waste management system in Serbia. These include investment in infrastructure, public awareness campaigns and the use of innovative digital tools to reduce waste and support a circular economy.

1. Introduction

The issue of food waste has become an urgent global concern, attracting significant attention due to its environmental, health, economic, and social implications [1]. The definition of the food waste covers both edible and inedible raw or prepared materials lost during production, processing, and transport. It includes waste from vegetables and meat, or inedible materials such as bones, eggshells, or banana peels. Food waste, therefore, refers to all food whose appropriate quality has expired due to non-use, spillage, contamination, impact damage, or other harm during production, storage, processing, or other stages in the food distribution chain. Examples include animal by-products and plant waste that have become unusable due to commercial reasons, production errors, and packaging defects. Proper sorting of individual fractions is the first and fundamental step in a proper waste management system [2,3].

The main causes of food waste are overproduction, consumer behavior, food safety regulations, and economic factors. Overproduction is a major problem as farmers and food manufacturers often produce more food than is needed to meet demand. In addition, inefficiencies in the supply chain, such as poor logistics, transportation problems and inadequate storage facilities, can cause food to spoil before it reaches the consumer [4,5]. Consumer behavior also plays an important role. Impulse buying, inadequate meal planning and misunderstandings about expiry dates can all contribute to too much food being thrown away. Portion sizes in restaurants and at home can lead to food not being eaten and leftovers that cannot be consumed later. Consumers’ lack of awareness of proper food storage, the use of leftovers or the interpretation of food labels can also lead to increased waste. Food safety regulations can also result in perfectly good food being thrown away if it does not meet certain standards such as appearance, size, labeling or minor packaging defects. Cultural practices can also contribute, as the way food is prepared and served in some cultures can lead to excessive waste. Confusion over expiry dates, particularly between “best before” and “use by” dates, can lead to consumers throwing away food that is still safe to eat [6,7]. Finally, economic factors may lead businesses to dispose of unsold food rather than donating it or finding other uses for it, as this may be more cost-effective [8].

The specific amounts of food waste can vary by region, but the main categories of wasted food are generally as follows: fruit and vegetables, cereals and grains, meat and fish, dairy products, bakery products, ready meals. The largest category is fruits and vegetables due to their high perishability and esthetic appeal, while grain waste mostly occurs during processing and storage, often due to pests and spoilage. Meat and fish are wasted mainly due to spoilage and overproduction, while dairy products have a short shelf life. Baked goods enter the waste cycle through unsold and discarded products, and prepared food waste comes from leftover food from households and restaurants. The exact amounts can vary, but globally, fruit and vegetables make up the majority of food waste, followed by cereals and grains and then meat and dairy products [9,10,11].

Food waste is recognized as a critical social issue [12,13,14] directly impacting human well-being and food security. Wasted food exacerbates the problem of access to food, especially in communities with limited purchasing power. With the global population expected to rise [15], ensuring sufficient food availability becomes even more vital.

The current food production and consumption systems have been criticized for their inherent contradictions. According to Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) reports, around one-third of global food production is lost or wasted every year, with significant consequences for natural resources and environmental sustainability [16]. Tackling this problem is crucial, not only to reduce the impacts on the environment, but also to ensure resource efficiency and food security. For Serbia, an EU candidate country, the alignment of food waste management practices with EU standards is particularly urgent. Serbia is under increasing pressure to adopt sustainable practices that comply with international guidelines and contribute to the transition to a circular economy [17].

It is alarming that approximately one-third of all food produced globally is lost or wasted [18], while millions of people continue to suffer from hunger and malnutrition. This imbalance highlights the discrepancy between food production and consumption and underlines the environmental and resource inefficiency of the current system. A key challenge in addressing food waste management is that it occurs throughout the entire food supply chain. The United Nations (UN) has identified food waste as a critical area of focus in its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly Goal 12, which aims to ensure sustainable consumption and production patterns. The distinction between food loss and food waste is largely based on their position within the supply chain. Food losses typically occur early- to mid-supply chain, during stages such as agricultural production, harvesting, transportation, storage, and processing. Food waste, however, takes place toward the end of the supply chain, during distribution, retail, and consumption [19]. The effects of food waste go beyond the food itself and include the waste of resources such as energy, water and labor used in farming, transportation, processing and storage [20]. The COVID-19 pandemic has had a significant impact on food waste production in several ways, leading to both an increase and a decrease in waste volumes. Before the pandemic, food supply chains were generally more stable. The COVID-19 pandemic caused significant disruption, resulting in too much food being wasted due to insufficient transportation, processing and storage capacity as farms struggled to get their produce to market. During the pandemic, many consumers bought food in large quantities and stockpiled, leading to increased wastage as food went unused or spoiled. After the initial period of panic buying, awareness of food waste grew and some consumers became more mindful of their buying and consumption habits. Before COVID-19, restaurants and catering companies generated significant amounts of food waste through unsold meals and spoilage. The pandemic led to temporary closures and reduced capacity, which initially resulted in less waste in the sector. However, when restaurants reopened, many were faced with the challenge of managing waste due to fluctuating customer demand. The pandemic prompted many people to cook more at home. This change in behavior had varying effects on the amount of food waste. The pandemic prompted a greater focus on sustainability and reducing food waste. The economic challenges during the pandemic had an impact on food production and distribution. Farmers struggled to sell their produce, leading to increased waste, while some consumers faced financial difficulties and may have wasted less food out of necessity. These inefficiencies also contribute to greenhouse gases (GHGs) emissions, further exacerbating the global climate crisis [21,22,23,24,25].

As far as we know, this is the first comprehensive study specifically addressing food waste management in Serbia and assessing its compliance with European and global best practices. By comparing Serbia’s current status with established international models, this paper identifies critical gaps and proposes actionable strategies to improve the efficiency and sustainability of the food waste management system in Serbia.

2. Methodology

When conducting the review, we carried out the following steps: formulation of research objectives, literature search, inclusion criteria and screening, exclusion criteria, data extraction and analysis. It is a qualitative (observational) study aimed at summarizing the available evidence on food waste management in Serbia and identifying the main trends, gaps and potential improvement strategies.

The main objective was to examine the state of food waste management in Serbia and the contextualization of the challenges and opportunities in a global and EU framework. A literature search was carried out using the literature databases Google, Google Scholar, Science Direct, National Library of Medicine, and Scopus as general research platforms using the following keywords: food waste, Serbia, EU, management, legislation, and good practices. The included articles/manuscripts and guidance had at least three of the six abovementioned key words. The search was carried out under the time range October 2024–March 2025 and 318 literature sources were obtained. Articles that were excluded by screening procedure were articles that were not fully available, were duplicates, or were available in languages other than Serbian or English, or that did not deal with the challenges, gaps or perspectives in food waste management. Articles that were cited by newest reviews were also removed from the list of references. Finally, 106 documents (articles, legislation, and guidance) remained for the preparation of the manuscript. The next step was data extraction and attribution into the results section and analysis of how this can contribute to the food waste management system development in Serbia, particularly related to challenges, gaps and perspectives.

3. Results from Literature Search

3.1. Food Waste Management Legislation in EU (Policies and Regulations Addressing Food Loss and Waste in EU)

The management of food waste is a global problem with far-reaching environmental, social and economic implications. Both international agreements and European Union (EU) legislation address this issue and embed the reduction of food waste in a broader framework of sustainability. These legal and policy instruments set targets and mechanisms to reduce food waste at all stages of production, distribution and consumption [26].

At the international level, the UN and FAO have identified food waste reduction as a critical global priority. The UN SDGs provide a global framework for tackling food waste [27]. Sustainable Development Goal 12.3 explicitly calls for halving global per capita food waste at the retail and consumer levels and reducing losses along production and supply chains by 2030. Other relevant goals are SDG 2, which focuses on achieving food security through sustainable systems; SDG 12, related to responsible consumption and production with a special Target 12.3: Halve global per capita food waste; SDG 13, related to actions for climate change since proper food waste management contributes to the decrease of GHG emission, particularly methane; and SDG 15, which aims to protect terrestrial ecosystems. The Paris Agreement under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) emphasizes the importance of reducing GHG emissions as food waste contributes significantly to these emissions through agricultural production, transportation and decomposition in landfills and accounts for 8 percent of total global GHG emissions [28,29]. Therefore, dealing with food waste is directly aligned with the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting the global temperature increase to well below 2 °C, with the aim of limiting the increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels [28]. The Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and its Aichi Biodiversity Targets emphasize the need to halt biodiversity loss, which is often caused by land-use change and habitat destruction associated with excessive agricultural production [30]. Reducing food waste can reduce the demand for agricultural production and thus reduce pressure on ecosystems, preserve biodiversity and promote the sustainable use of resources. In response to the SDGs, the global SAVE FOOD initiative and the FAO Platform to Measure and Reduce Food Losses and Waste were established to address the issue of food waste [31,32].

Building on these global commitments, the European Union has integrated food waste reduction into its broader sustainability framework. In the EU, the management of food waste is a priority that is integrated into its sustainability agenda. The Circular Economy Action Plan (2020) puts the reduction of food waste at the center of the EU’s resource efficiency strategy [33]. By emphasizing waste prevention, redistribution of surplus food and innovation in packaging and logistics, the action plan aims to reduce food waste throughout the supply chain while supporting broader climate and biodiversity goals. The strategy aligns with UN SDG 12.3 by proposing legally binding targets for food waste reduction and prioritizing prevention, donation and recycling throughout the food chain.

The legal backbone for food waste management in the EU is the Waste Framework Directive, originally introduced as Directive 2008/98/EC and later amended by Directive (EU) 2018/851 [34]. These directives set out a five-tier hierarchical approach to waste management, with prevention having the highest priority, followed by re-use, recycling, recovery and disposal. The amended Directive introduces a formal definition of food waste and requires Member States to monitor, measure and report the amount of food waste. It also requires Member States to develop programs to prevent food waste in production, processing, retail and households and to promote the redistribution of surplus food through donations as a preferred alternative to disposal. In addition to waste prevention measures, Member States must ensure that (by 31 December 2023) bio-waste is either separated and recycled at source or collected separately and not mixed with other types of waste [34].

The EU’s commitment to combating food waste extends to certain sectors. In fisheries, the Common Fisheries Policy includes a landing obligation under Article 15 of Regulation (EU) No 1380/2013, which establishes the Common Fisheries Policy (CFP), includes the Landing Obligation, a measure that effectively prohibits the discarding of fish that are subject to catch limits or minimum sizes [35]. This measure, which was fully implemented in 2019, stipulates that all catches must be recorded, landed and utilized in order to reduce the waste of resources in marine ecosystems. In agriculture, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) influences food waste through subsidies and rural development programs. While subsidies have historically encouraged overproduction, CAP reforms aim to bring agricultural practices in line with sustainability goals and support better storage and logistics to minimize waste [36].

Food waste at the consumer level is also addressed by Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 on the provision of food information to consumers [37]. This regulation requires the clear labeling of “use by” and “best before” dates to avoid confusion and prevent the premature disposal of edible food. By harmonizing labeling standards across member states, the regulation ensures consistency and supports consumer education.

Reducing food waste and promoting the sustainable use of resources are key objectives of the EU Circular Economy Action Plan. In line with this, the EU Platform on Food Losses and Food Waste was established in 2016 to bring together EU institutions and private stakeholders to support the development of measures to prevent food waste, share best practices and monitor progress [38]. More recently, the issue of food waste has been highlighted through the Farm to Fork Strategy [6,17], one of the key pillars of the European Green Deal [39], which envisages a transition to sustainable food systems.

Furthermore, the European Commission has supported the reduction of food waste through two important research projects: FUSIONS (2012–2016), which focuses on social innovation and waste prevention strategies, and REFRESH (2015–2019), which aims to improve resource efficiency throughout the food and drink supply chain [26].

In addition, in May 2019, the Commission adopted a delegated decision setting out the scope and methods for measuring food waste, including voluntary measurements and minimum quality standards. Namely, directive (EU) 2018/851 requires Member States to measure the amount of food waste according to standardized methods described in Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2019/1597 [40]. This decision specifies that food waste must be measured separately for each stage of the food supply chain, including primary production, processing and manufacturing, retail and distribution, restaurants and food services, and households.

The EU’s legislative and policy measures together form a comprehensive framework for tackling food waste. By aligning sectoral policies such as the Circular Economy Action Plan, the Farm to Fork Strategy and the Waste Framework Directive, the EU ensures that waste reduction is tackled at every stage of the supply chain. This integrated approach emphasizes prevention as a top priority while enabling redistribution and recycling to maximize resource efficiency and minimize environmental impact.

For Serbia, aligning national policy with this international and European framework represents a strategic opportunity to improve the overall efficiency of its food waste management system. Strengthening the legal framework and improving coordination between stakeholders would support the transition to a more sustainable and circular food system.

3.2. Food Waste Management Legislation in Serbia (Policies and Regulations Addressing Food Loss and Waste in Serbia)

Serbia’s existing waste management regulations lack specific guidelines for food waste reduction and recovery (Table 1).

Table 1.

Serbia’s waste management regulations/strategies.

To improve food waste management, regulatory bodies in the republic of Serbia have to pass a law and revise the abovementioned strategies to include food waste prevention, tracking, and resource recovery provisions.

In November 2020, the Green Agenda for the Western Balkans with five pillars was adopted by the WB countries and after a few months an action plan came into force [48]. The Republic of Serbia has committed to achieving the goals of the UN 2030 Agenda and the Paris Agreement. Furthermore, as an EU accession candidate, Serbia is well on its way to aligning its national regulations with the EU legislation. Regarding the circular economy, the relevant strategic documents and regulations set specific targets and deadlines for achieving them in line with European standards. The management of food waste as a cross-sectoral issue is partly regulated by several laws and regulations. In recent years, this issue has been at the top of the list of priorities that need to be addressed. As the capacity for food waste collecting and treatment is very low, it is estimated that 99% of this waste ends up in landfills [49]. The uncontrolled decomposition of food waste can release significant amounts of greenhouse gasses, particularly methane, into the air and impact climate change. According to the Roadmap for Circular Economy in Serbia, agriculture and food waste is one of the four sectors that have great potential for circular economy [47].

As far as food waste treatment is concerned, it is still insufficiently developed. It is estimated that up to 30% of all food produced worldwide is lost or wasted. In Belgrade alone, there are 1147 registered restaurants and bars that produce commercial and biodegradable food waste. There are also 1639 snack bars and coffee bars. Belgrade produces 158,000 tons of food waste (26.3%) per year, which is 8% of Serbia’s total municipal waste. On average, around 100 kg of food per capita is lost every year [50]. The overall impact of Belgrade on the food sector is pervasive and far-reaching, affecting national and international supply patterns, energy and water consumption and waste management. Almost all generated quantities of food waste end up in landfills without pre-treatment. Composting and anaerobic digestion plants are not represented in a very large number. Acceleration of the circular economy in this sector entails stronger commitment and a collaborative approach involving government, businesses and the science community, as well as consumers’ cooperation. Industry has an important role to play in both identifying and delivering solutions [49,51]. Complexity and different interests throughout the circle need to be properly addressed, a proper approach implemented, and quick fix solutions avoided. A long-term strategy and enabling framework, balancing the costs and benefits to different parties, incentivizing economies of scale and taking into account the global dimension are needed. Making best use of existing legislations, through proper evaluation of their impact on the circular model, full implementation and enforcement are the primary objectives for increasing resource efficiency and pursuing circularity [47]. To unlock the potential of the sectors and business opportunities, investment certainty needs to be guaranteed. Removing obstacles, funding opportunities, demand-side push and incentives to research and innovation are key steps to accompany further the engagement of industry and the business community.

Education plays a crucial role in raising awareness of food waste and influencing consumer behavior. School and university programs that address sustainable consumption, food storage and waste prevention have been shown to improve food handling and reduce household waste [52,53,54]. Raising awareness of the environmental impacts of food waste and promoting composting and recycling has led to a measurable reduction in waste in educational institutions [53]. Integrating food waste education into school curricula has also proven to be an effective strategy to improve students’ food handling behaviors [55]. In addition, educational initiatives such as cooking workshops and waste separation activities have been shown to improve awareness and practical food waste management skills [55]. Building on these initiatives, strengthening the role of educational institutions in promoting sustainable consumption and reducing food waste could further improve the overall efficiency of the national food waste management system [43].

In addition to educational factors, cultural and social norms also influence food waste behavior. In Serbia, traditional values of hospitality often lead to generous food portions at social gatherings, which can contribute to food waste. To change consumer behavior, these deeply ingrained social norms need to be addressed through targeted awareness campaigns and educational programs [50].

Strengthening educational and social strategies in combination with regulatory and infrastructural improvements could significantly increase the effectiveness of food waste management measures in Serbia.

3.3. Policy Drivers for Food Waste Management in Serbia

Serbia, like many countries, faces substantial challenges regarding food waste, with significant implications for its environmental and health impact and potential for resource optimization. To effectively address food waste management in Serbia, it is necessary to implement policies that emphasize prevention, reduction, recycling, and disposal, while also fostering public awareness, engaging the private sector, and enhancing environmental outcomes. The following outlines key drivers for the formulation of food waste management policies in Serbia.

Primarily, Serbia should build and strengthen its legal instruments for waste management frameworks by harmonizing policies with European Union directives, such as the EU Circular Economy Action Plan, with a specific focus on reducing food waste across all stages of the food supply chain. These policies should be legally enforceable, incorporating clear compliance measures and penalties for non-compliance. According to the Waste Prevention Plan adopted by the Ministry of Environmental Protection in February 2025, a comprehensive extended producer responsibility (EPR) system should be implemented for food manufacturers, retailers, and suppliers [43]. This would mandate the reduction of food waste at the production and retail levels, encourage sustainable packaging practices, and ensure the accountability of food producers throughout the supply chain [56,57,58,59,60,61,62].

To effectively address these challenges, the following key policy drivers should be considered:

- (1)

- Public awareness and education could be improved by [59,63,64,65]:

- (a)

- government-led initiatives, focused on raising awareness about the environmental, social, and economic impacts of food waste. Public education should aim to promote responsible food consumption, effective meal planning, and better understanding of food labeling practices;

- (b)

- Educational initiatives in schools and universities about food waste management topics that can be part of educational curricula and instill sustainable consumption practices from an early age. By fostering awareness in schools and universities, Serbia can cultivate long-term behaviors that reduce food waste among younger generations;

- (c)

- Development and promotion of digital tools, such as mobile applications, that can assist consumers in tracking food expiration dates, optimizing meal planning, and identifying opportunities for food sharing [59,63,64,65]. These platforms can also facilitate the redistribution of surplus food and reduce household waste.

- (2)

- Public and private sector collaboration could be enhanced by:

- (a)

- engagement of retailers and the food service sector,

- (b)

- incentivizing food recovery programs and/or

- (c)

- strengthening partnerships with non-governmental organizations (NGOs). It is essential to bolster collaborations between governmental agencies and NGOs focused on food recovery, sustainable agriculture, food donation and waste management. These partnerships can enhance the efficacy of food waste reduction initiatives and broaden their reach [66].

- (3)

- Policies should prioritize waste segregation, recycling, and composting, and promote the utilization of food waste as a resource for producing value-added products such as animal feed, bioenergy, and compost. Proper segregation facilitates the effective recycling or composting of food waste and enhances overall waste management efficiency. The government should promote the development of community-based and household composting systems as a means of diverting organic waste from landfills. Support can be provided through subsidies for composting equipment or through public education campaigns on proper composting techniques [56,60,61]. Moreover, Serbia should encourage the establishment of anaerobic digestion facilities to convert food waste into biogas for energy production. According to the document Roadmap for Circular Economy in Serbia, investments in composting infrastructure and anaerobic digestion are an important measure to reduce the amount of waste sent to landfills and increase the production of renewable energy. By creating a sustainable energy source from food waste, the country can mitigate the environmental impact of waste while contributing to renewable energy goals [56,60,61]. In addition, the reduction of packaging waste, which often accelerates food spoilage, should be included in national policy. The government should promote the use of sustainable packaging materials and encourage manufacturers to invest in packaging innovations that extend the shelf life of food, as this is one of the key factors for better resource management [47].

- (4)

- Developed comprehensive systems for monitoring and reporting food waste at all stages of the food supply chain, from production to consumption, could produce reliable data on food waste. This data can help with the identification of critical areas for intervention and ensure that policies are evidence-based and targeted as well as mandatory reporting for businesses [56]. According to the Waste Prevention Plan, adopted by the Ministry of Environmental Protection in February 2025, the introduction of a mandatory reporting system for food waste at all levels of the supply chain is foreseen, using the methodologies defined in Directive (EU) 2018/851 [43].

- (5)

- Behavioral change and consumer engagement

Finally, addressing the behavioral aspects of food waste is crucial for the long-term success of waste management policies. In addition to the measures mentioned above, instruments should be tailored to the context in which the behavior occurs [34]. A behavior change perspective is essential to improve the efficiency of circular food systems and identify the key success factors and barriers to scaling up. By addressing consumer habits, improving food literacy and promoting sustainable consumption patterns, Serbia can create a more efficient and resilient food system [56].

3.4. Success Stories and Best Practices from International Examples

Reducing food waste is a pressing global challenge that requires a strategic and structured approach. According to an OECD report, four critical factors underpin successful food waste reduction efforts: the development of evidence-based strategies, the integration of large-scale awareness campaigns with local community engagement, the establishment of collective targets for businesses, and robust monitoring and reporting mechanisms [67]. These components ensure that initiatives are both comprehensive and adaptable to diverse contexts. By fostering public awareness, shaping consumer behaviors, and driving changes in the retail and production environments, these initiatives promote sustainable practices and mitigate environmental impacts.

Successful examples of food waste management campaigns and initiatives from other countries can provide valuable insights for improving food waste reduction policies in Serbia.

One of the most successful awareness-raising campaigns in Europe to date is the British campaign “Love Food Hate Waste” (LFHW) [68], which was launched in 2007 by the Waste and Re-sources Action Program (WRAP). The campaign is supported by the governments of England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. The LFHW campaign took a multi-pronged approach involving partnerships with more than 50 major retailers, brand owners, manufacturers and suppliers as part of the Courtauld Commitment—a voluntary agreement to improve resource efficiency and reduce waste in the UK food sector. Key elements of the campaign included: consumer education, e.g., practical advice on meal planning, portion sizes and food storage; improved packaging and labeling, e.g., working with manufacturers and retailers to standardize food labeling; and community engagement, e.g., providing training and resources to local authorities and communities. Since the campaign was launched in 2007, avoidable food waste in UK households has been reduced by an impressive 21%. The campaign remains one of the most comprehensive and influential food waste reduction programs in the world and serves as a model for similar initiatives in other countries [69]. In Austria, the nationwide campaign “Lebensmittel sind kostbar!” (“Food is precious!”) was launched in 2011 by the Austrian Federal Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry, Environment and Water Management and a private waste management company [70]. The campaign was developed to reduce and avoid food waste through a coordinated effort by companies, consumers, municipalities and social institutions. The initiative focuses on raising awareness and improving food handling at all levels of the food supply chain, including production, logistics and distribution. A key element of the campaign is the emphasis on education and awareness. Educational materials and school programs have been developed to engage students and young people and teach them responsible food handling from an early age. Information campaigns are aimed at both consumers and employees, giving advice on better food storage, portion control and the importance of food donation. The campaign also supports food sharing and redistribution activities and helps to redirect surplus food to social institutions instead of wasting it. The “Stop Food Waste Program” is another example of a successful campaign that was funded by the Irish Environmental Protection Agency between 2009 and 2021. It focused on educating households and improving consumer behavior in relation to food storage and meal planning. Through a combination of workshops, community events and educational materials, the campaign achieved a measurable reduction in household food waste and raised public awareness of the environmental and economic impact of food waste [71].

In addition to the initiatives in Europe, one of the most significant in the United States that should be highlighted as a best practice is Kroger’s Zero Hunger|Zero Waste program [72]. This initiative is a comprehensive strategy to simultaneously reduce food waste and fight hunger. Since its launch in 2017, Kroger has donated approximately 700 million pounds of surplus fresh food to local food banks and hunger relief organizations, providing more than 100 million meals annually. This initiative not only supports communities, but also reduces the impact on the environment by keeping food waste out of landfills, where it would otherwise produce methane, one of the most potent greenhouse gasses. Kroger is reducing waste through several key strategies. Through competitive pricing and promotions, Kroger encourages customers to buy fresh food before it expires. In fresh food departments, such as bakery, dairy, produce and meat, products approaching their expiration date are marked down to increase sales and reduce waste. Unsold but still edible food is donated daily to local charities and food banks through Kroger’s Food Rescue program. Any food that cannot be sold or donated is recycled through composting, animal feed production or anaerobic digestion to generate renewable energy. Kroger also works with distribution centers and supply chain partners to improve inventory management, reduce overproduction and improve demand forecasting.

In addition to these national campaigns, it is important to support the global campaign “Think. Eat. Save. Reduce your food footprint”, launched by the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and FAO as part of efforts to achieve Sustainable Development Goal 12.3 (halve food waste by 2030) [73]. The aim of the campaign was to raise awareness of the environmental impact of food waste and promote sustainable consumption patterns. The campaign was implemented through consumer education, improving supply chain efficiency and promoting public–private partnerships. The campaign helped to reduce food waste at the retail and consumer level and strengthen global capacity to measure and report on food waste reporting [74]. In particular, it served as the theme for World Environment Day 2013 under the slogan “Think. Eat. Save”. This helped make food waste a major global issue and inspired the launch of similar national campaigns worldwide.

Programs such as Japan’s Waste-to-Energy systems [67] and South Korea’s Pay-as-You-Throw models [75,76] exemplify how policy integration and community participation can significantly reduce waste [77]. The Table 2 summarizes exemplary global initiatives, highlighting their goals, focus areas, and outcomes. These initiatives serve as actionable models for adapting and scaling food waste management solutions across regions.

Table 2.

Examples of global initiatives for food waste reduction.

While these international practices demonstrate the effectiveness of combining policy enforcement, consumer education, and resource recovery technologies in a cohesive food waste management strategy, and offer valuable lessons, Serbia currently lacks a coordinated national food waste reduction campaign of similar scale and structure. Existing efforts in Serbia are fragmented and limited in scope. One of the most significant initiatives to date is the UNDP-supported blockchain platform in partnership with Delhaize Serbia and Food Bank Belgrade, which facilitates the redistribution of surplus food from retailers to humanitarian organizations. This initiative has improved food safety and traceability through digital records, but its impact remains limited to specific retailers and regions. The platform, called “Plate by Plate”, was launched in December 2020 with the aim of reducing food waste and improving the efficiency of food donations. It enables real-time tracking of food donations and ensures transparency and accountability throughout the donation process. In the first year alone, more than 37,000 meals were distributed to groups in need through the platform, preventing more than 15 tons of food from ending up in landfills [85]. This initiative has improved food safety and traceability through digital records, but its impact remains limited to certain retailers and regions. In addition, the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) has developed a food waste value chain guide for the HORECA sector (hotels, restaurants and catering), which provides technical recommendations to reduce food waste in the commercial sectors [66]. This guide was prepared as part of the DKTI project Climate-sensitive waste management in Serbia, which aims to introduce circular waste management in selected regions of Serbia in order to contribute to climate protection. The guide provides a comprehensive overview of HORECA food waste in Serbia, identifies gaps in the waste management infrastructure and proposes measures for the transition to a circular economy. Key recommendations include introducing food waste separation systems at source, improving data collection and monitoring, and promoting food redistribution through donations to food banks. A major obstacle is the lack of incentives for the separation and recycling of food waste as secondary raw materials, which prevents the development of a functioning market. The guidelines recommend the introduction of economic instruments, such as pay-as-you-throw systems and the setting of tariffs, the strengthening of municipal capacities and the support of alternative methods of recycling food waste, including the production of animal feed, biogas, composting and bioplastics. The guidelines also emphasize the importance of raising awareness and training stakeholders. However, the adoption of these guidelines remains voluntary and inconsistent across the sector.

In addition, the project “Towards Better Food Waste Management in Serbia” (2018–2021), implemented by National Alliance for local economic development (NALED) in cooperation with GIZ and private companies, stands out as an important initiative to improve the reduction of food waste at national level [86]. The project introduced food waste collection systems in public institutions and businesses and increased the number of large food waste producers participating in responsible waste management programs by 50%. This initiative diverted 1300 tons of food waste from landfills to recycling and composting facilities. The project also included educational workshops, such as a public demonstration on proper waste separation and how to use food more efficiently. As part of the project, “Guidelines for Inspections in the Area of Food Waste Management” were developed to improve the efficiency of inspection services, enhance compliance with food waste regulations, and promote best practices in waste management [87]. This project was an important step towards improving food waste management in Serbia. Through cooperation between the public and private sectors, concrete results have been achieved in reducing the amount of waste that ends up in landfills, thus contributing to environmental protection and promoting a circular economy.

Despite these positive steps, Serbia still lacks the scale and consistency seen in European and US models. National-level public education, regulatory support for food redistribution, and improved monitoring and reporting are critical to closing the gap with international best practices. Adopting proven strategies such as food labeling reform, tax incentives for food donations, and strengthened public–private partnerships could position Serbia to meet its food waste reduction targets and align with EU and global sustainability goals.

3.5. Challenges and Gaps

Despite the paradoxical coexistence of food insecurity and food waste, Serbia faces numerous challenges in tackling this problem, especially in terms of waste management, consumer behavior and logistical infrastructure. Below are some of the main challenges related to food waste management in Serbia.

- (a)

- Waste separation and infrastructure

Unlike in many developed countries, food waste in Serbia is mixed with other household or municipal waste. This makes it difficult to effectively recycle or reuse food waste and contributes to inefficiencies in waste management systems. In the EU, waste separation at the source is mandated under the Waste Framework Directive (2008/98/EC), which requires member states to introduce separate collection and recycling systems for bio-waste [88]. Many households and businesses do not separate food waste and there is very limited infrastructure for separate waste collection. Moreover, Serbia still lacks the facilities and infrastructure to implement large-scale waste separation and recycling programs [43]. As a result, most food waste ends up in landfills instead of being composted, or recycled for energy.

- (b)

- Consumer awareness and behavior

Consumers are unaware of the extent of food waste and its environmental, social and economic consequences. Most people in Serbia continue to waste food because they buy too much, store it improperly and do not know how to use leftovers creatively [89]. In some cases, traditional eating habits or expectations of food “freshness” can lead to food being thrown away prematurely. In contrast, countries like the UK and Ireland have implemented national-level educational campaigns such as “Love Food Hate Waste” [68] and the “Stop Food Waste Program”, [84] which have successfully changed consumer behavior and reduced household food waste. While in Serbia some educational programs and campaigns exist, they remain fragmented and have not yet achieved measurable national-level impact.

- (c)

- Food redistribution and donation systems

Although there are charities in Serbia, such as the Red Cross and the National Kitchens program i.e., Food Bank, the system for redistributing surplus food to the needy is not as developed and efficient as in some other countries. In the US, the “Zero Hunger/Zero Waste” program by Kroger [72] and the “Lebensmittel sind kostbar!” initiative in Austria [70] have created efficient networks for surplus food redistribution, supported by tax incentives and legal protections for donors. Serbia’s “Plate by Plate” blockchain platform (launched by UNDP in collaboration with Delhaize Serbia and the Food Bank Belgrade [85] represents a positive step toward improving food redistribution but remains limited to certain retailers and regions.

- (d)

- Food waste along the supply chain

Food waste in Serbia is not only a problem for consumers, but also a problem within the supply chain. A significant proportion of food waste occurs at the production, processing and retail stages due to poor storage conditions, inadequate transportation and inefficient distribution practices, which result in large quantities of food being lost before it even reaches the consumer. In the EU, supply chain losses count for a small portion (5%) of the total food waste throughout the food chain as a result of better logistics, cold chain improvements, and partnerships between producers and retailers to reduce overstocking and manage supply and demand. In Serbia, logistical issues and infrastructure gaps continue to cause high levels of food waste at the production and retail levels [43].

- (e)

- Waste processing and recycling infrastructure

Serbia’s infrastructure for the disposal of food waste is still underdeveloped. Many regions lack the necessary facilities for composting, recycling or converting food waste into biogas or animal feed. In the EU, countries like Germany and Austria have established anaerobic digestion plants and composting facilities, supported by clear national policies and financial incentives [90]. The GIZ Guidelines for the HORECA sector provide a framework for improving waste management in commercial settings, but adoption in Serbia remains limited and inconsistent. To overcome this challenge, investments in waste processing technologies are needed [18,91,92,93]. Landfill leachate is a highly contaminated liquid that is produced during the decomposition of organic waste in landfills. It contains various pollutants, including degradable organic substances, inorganic macro-components, heavy metals and xenobiotic organic compounds. The composition and concentration of these pollutants can vary greatly depending on factors such as landfill age, waste composition, temperature and precipitation. For example, the concentrations of organic components in leachate can be very high in the early aerobic phase of landfilling and then decrease and stabilize during the methanogenic phase. Conversely, ammonia-nitrogen concentrations may not decrease significantly over time, leading to long-term contamination risks. Understanding these characteristics is crucial for assessing environmental risks and developing effective mitigation measures for sustainable municipal waste management. Currently, there is no specific strategy for dealing with landfill leachate in Serbia, which is a major challenge for sustainable waste management [94,95,96,97,98].

- (f)

- Regulatory gaps and policy limitations

While there are efforts to improve waste management in Serbia, there is still a need for a more comprehensive policy that focuses specifically on preventive measures, i.e., reducing food waste. The current regulations focus on general waste management and not on food waste as a specific problem, which reduces the effectiveness of efforts to address this issue. In the EU, the Farm to Fork Strategy and the Waste Framework Directive provide clear guidelines and targets for reducing food waste. In Serbia, the Waste Prevention Plan (2025) [43] and other recently published strategic papers (Table 1) represent progress, but without specific targets for food waste reduction and better coordination between government agencies and the private sector, the impact will remain limited.

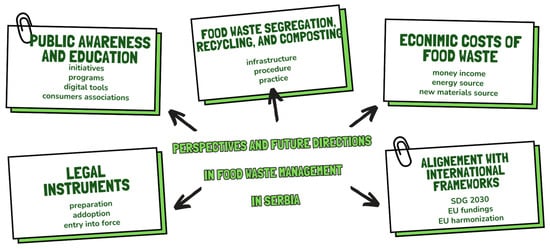

4. Perspectives and Future Directions

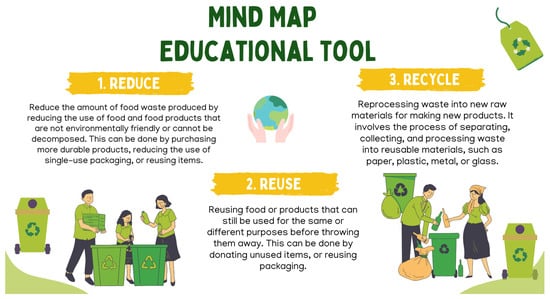

Based on the policy drivers, challenges and gaps described above, the following perspectives and future directions can be assumed: adoption of legal instruments and increased public awareness, including education, digital tools, and consumer association activities (Figure 1). The separation, recycling and composting of food waste using new infrastructures and defined procedures in practice could be an important direction for an improved food waste management system in Serbia [49,50,51,99].

Figure 1.

Suggested educational tool for consumer awareness on food waste reduction (based on the principles of reduce, reuse, and recycle).

Food waste as improperly treated organic waste is extremely questionable. The following directions of food waste treatment should be considered to turn it into a new resource and economic benefit while protecting the environment and human health. Reducing the production of food waste can lead to a reduction in GHG emissions. This is because food waste could rot in landfills and produce methane, a greenhouse gas about 30 times more potent than CO2. Appropriate treatment methods (e.g., composting, anaerobic digestion) prevent waste from ending up in landfills, which reduces methane emissions and has an impact on climate change. Processes such as anaerobic digestion or composting convert food waste into biogas, which is both renewable energy and a nutrient-rich fertilizer. For example, literature data indicates that the use of microalgae in combination with ozonation is an effective approach for the treatment of landfill leachate [100]. Microalgae utilize nutrients from the wastewater, such as ammonia, organic matter and phosphorus, for their growth and production of lipids that can be used to produce biodiesel. Ozonation improves the quality of wastewater and promotes the growth of microalgae, achieving a double effect—the elimination of pollutants and the production of renewable energy. This method represents a sustainable solution for wastewater treatment, but requires further research and adaptation to local conditions for wider application. Furthermore, composting turns waste into soil conditioner, closing the loop in agriculture and reducing dependence on synthetic fertilizers. Treating waste on site reduces transportation and landfill costs, while the by-products can be turned into cash (e.g., by selling compost or biogas), reducing waste disposal costs expenses [101]. Furthermore, the treatment of food waste transforms waste into resources, which is in line with the principles of the circular economy, and prevents pollution if the waste is properly treated so that leachate is produced in landfills which is not harmful to the environment [100,102]. Proper treatment ensures compliance with regulations and avoids fines. It also aligns with the company’s sustainability goals and strengthens the brand’s reputation. While prevention is key to saving edible food, treating inedible waste secures resources such as energy and fertilizer that could be reinvested in the food system and indirectly support long-term agricultural productivity [101].

Based on the above characteristics and possibilities for food waste, some treatment methods could be implemented in Serbian practice to reduce food waste and generate energy, fertilizer and protein. Food waste could be composted to provide nutrients to the soil, it could be fermented to produce biogas, or it could be used as animal feed if it is safely converted into animal feed. Insect farming is also attractive, for example by using larvae to process waste into protein and fertilizer [103,104,105].

Generally, improving the food waste management system can include a variety of strategies and perspectives. In order to reduce food waste in Serbia, a combination of legal measures, improved infrastructure and targeted awareness-raising campaigns is necessary. Successful examples from other countries show that a structured and well-coordinated approach can significantly reduce food waste at both the consumer and supply chain level. The following initiatives and solutions could be effectively applied in Serbia:

- (a)

- Strengthening legislation and incentives

The introduction of a national food waste reduction strategy, aligned with the EU Circular Economy Action Plan and the Waste Framework Directive, would provide a clear legal framework for tackling food waste. Strengthening the legal framework through binding food waste reduction targets and extending producer responsibility to food manufacturers and retailers would encourage better stock management and food donation practices. Tax incentives for companies that donate surplus food and penalties for excessive waste, similar to the successful model implemented under the “Zero Hunger/Zero Waste” initiative in the United States, could motivate companies to become more active in reducing waste.

- (b)

- Improving the infrastructure for processing food waste

Expanding composting and anaerobic digestion infrastructure would enable the conversion of food waste into biogas and organic fertilizer, contributing to both waste reduction and renewable energy production. The introduction of food waste separation systems at both household and business level is essential to improve recycling rates. Currently, most food waste in Serbia ends up in landfills due to inadequate infrastructure and poor separation at source. Investing in better storage and transportation systems would also reduce the loss of food during the production, processing and distribution stages.

- (c)

- Redistribution and donation networks

Expanding the existing “Plate by Plate” blockchain platform for food donations would improve the efficiency and scale of food redistribution efforts. Currently, food donation systems in Serbia are still fragmented and limited in their reach. Legal protection for food donors, including liability protection and tax benefits, could further encourage businesses to participate in food donation programs. The creation of a centralized national platform for the redistribution of surplus food, following the example of successful initiatives in Austria and Denmark, would provide a more structured and coordinated approach to tackling food shortages and reducing waste.

- (d)

- Educating and raising consumer awareness

Consumer education is crucial to changing long-standing habits that contribute to food waste. A national awareness campaign along the lines of the UK’s “Love Food Hate Waste” program could focus on educating consumers about portion sizes, food storage and expiration date labeling. Studies from other European countries show that a better understanding of food labeling and storage techniques can significantly reduce house-hold waste. Implementing educational programs in schools and universities would promote long-term change in consumer behavior by increasing awareness of sustainable food consumption. Digital tools, such as mobile applications that help consumers track food expiration dates and plan meals more efficiently, could also support these efforts and reduce household waste. As illustrated in Figure 2, a structured educational tool that emphasizes the principles of reduce, reuse and recycle could serve as the basis for consumer awareness campaigns. This approach encourages consumers to minimize waste, extend the life cycle of food and promote responsible waste management through recycling and composting.

Figure 2.

Perspectives and future directions for food waste management in Serbia.

- (e)

- Sector-specific solutions for the HORECA sector

According to the GIZ food waste value chain guide for the HORECA sector, targeted measures for hotels, restaurants and catering services could significantly reduce food waste in the commercial sector. Optimizing portion sizes and better menu planning would minimize the amount of uneaten food. Better storage and inventory management would prevent spoilage and reduce waste in processing and retail. Working with food banks and charities to redistribute surplus food would ensure that edible food is not wasted. Other measures include encouraging the use of surplus food for animal feed, composting and biogas production, as well as training staff in waste reduction strategies and regularly monitoring food waste to identify areas for improvement.

- (f)

- Data collection and monitoring

The introduction of a mandatory food waste reporting system based on the methods defined in Directive (EU) 2018/851 would provide reliable data on the generation and management of food waste. Better data collection and monitoring would allow policy makers to identify critical areas for intervention and develop more effective waste reduction strategies. A centralized platform for tracking food waste throughout the supply chain would also help businesses and regulators measure progress and adjust strategies based on insights.

- (g)

- Public–private partnerships

Promoting cooperation between government agencies, food producers, retailers and non-governmental organizations would create a more coherent and effective framework for tackling food waste. Successful models from the EU show that strong public–private partnerships increase the efficiency of food donation programs and improve waste reduction at the production and retail level. Strengthening partnerships with waste management companies would increase the capacity for waste collection, processing and recycling in Serbia. Eso Tron’s success in processing organic waste shows the potential for expanding similar models to a wider range of food waste.

5. Conclusions

This paper represents a significant contribution to the understanding of food waste management in Serbia, as it is the first report that systematically analyzes the current status, challenges and gaps, while making suggestions for the future in line with European and global practices.

Food waste management in Serbia is a major challenge that overlaps with broader issues of sustainability, food safety and resource efficiency. Despite existing frameworks and international examples, there are still systemic gaps in legislation, infrastructure, and public awareness. To address these issues, Serbia needs to adopt a holistic approach that is in line with EU directives, focuses on waste prevention and promotes cooperation between sectors. Key factors influencing Serbian consumers’ food waste behavior include low consumer awareness, food labeling confusion, inefficient storage and transportation, and cultural norms such as large portions at social gatherings. Better consumer education, improved logistics in the supply chain and more effective redistribution networks for surplus food are needed to address these issues. Food waste has significant environmental and socio-economic consequences, such as major ecological impacts, financial losses and growing food insecurity, even in more developed and affluent societies. Expanding composting and anaerobic digestion infrastructure could mitigate these impacts while supporting renewable energy generation. From a social perspective, food waste represents a missed opportunity to reduce food insecurity. Strengthening donation systems and legal protection for food donors could improve food redistribution while reducing waste. Improving the food waste management system requires legal incentives, improved infrastructure and stronger public–private partnerships. Scaling up successful initiatives such as “Plate by Plate” and encouraging businesses to adopt sustainable practices could increase efficiency and reduce waste throughout the supply chain. By leveraging best practices from global models and strengthening domestic infrastructure and policies, Serbia can transition to a more sustainable and efficient food system that reduces environmental impact, maximizes resource utilization and improves social wellbeing.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: N.I. and M.Ć.; methodology: N.I., M.Ć. and V.M.; formal analysis: N.I. and M.Ć.; investigation: N.I., M.Ć. and A.V.; writing—original draft preparation: N.I., A.V. and M.Ć.; writing—review and editing: V.M. and D.K.; supervision: M.Ć. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was partly funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation, Republic of Serbia through two Grant Agreements with University of Belgrade-Faculty of Pharmacy No 451-03-136/2025-03/200161 and No 451-03-137/2025-03/200161.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Papargyropoulou, E.; Lozano, R.; Steinberger, J.K.; Wright, N.; bin Ujang, Z. The food waste hierarchy as a framework for the management of food surplus and food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 76, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girotto, F.; Alibardi, L.; Cossu, R. Food waste generation and industrial uses: A review. Waste Manag. 2015, 45, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teigiserova, D.A.; Hamelin, L.; Thomsen, M. Towards transparent valorization of food surplus, waste and loss: Clarifying definitions, food waste hierarchy, and role in the circular economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 706, 136033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Joardder, M.U.; Masud, M.H. Food Preservation in Developing Countries: Challenges and Solutions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Raak, N.; Symmank, C.; Zahn, S.; Aschemann-Witzel, J.; Rohm, H. Processing-and product-related causes for food waste and implications for the food supply chain. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 461–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavanaugh, M.; Quinlan, J.J. Consumer knowledge and behaviors regarding food date labels and food waste. Food Control 2020, 115, 107285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschemann-Witzel, J.; De Hooge, I.; Amani, P.; Bech-Larsen, T.; Oostindjer, M. Consumer-related food waste: Causes and potential for action. Sustainability 2015, 7, 6457–6477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sert, S.; Garrone, P.; Melacini, M.; Perego, A. Corporate food donations: Altruism, strategy or cost saving? Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1628–1642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silvennoinen, K.; Heikkilä, L.; Katajajuuri, J.-M.; Reinikainen, A. Food waste volume and origin: Case studies in the Finnish food service sector. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, Z.; Toth, J.D. Global primary data on consumer food waste: Rate and characteristics—A review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, K.S.; Chu, L.M. Characterization of food waste from different sources in Hong Kong. J. Air Waste Manag. Assoc. 2019, 69, 277–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, F.; Kurniawan, T.A.; Mohyuddin, A.; Othman, M.H.D.; Aziz, F.; Al-Hazmi, H.E.; Goh, H.H.; Anouzla, A. Environmental impacts of food waste management technologies: A critical review of life cycle assessment (LCA) studies. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 143, 104287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Almeida Oroski, F.; da Silva, J.M. Understanding food waste-reducing platforms: A mini-review. Waste Manag. Res. 2023, 41, 816–827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munir, K. Sustainable food waste management strategies by applying practice theory in hospitality and food services-a systematic literature review. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 331, 129991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Partnership and United Nations Environment Programme. Reducing Consumer Food Waste Using Green And Digital Technologies; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- FAO. The State of Food and Agriculture: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste Reduction; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, t.C., the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: A Farm to Fork Strategy for a Fair, Healthy and Environmentally-Friendly Food System (COM(2020) 381 Final). Brussels: European Commission. 2020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52020DC0381 (accessed on 16 December 2024).

- Al-Obadi, M.; Ayad, H.; Pokharel, S.; Ayari, M.A. Perspectives on food waste management: Prevention and social innovations. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 31, 190–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parfitt, J.; Barthel, M.; Macnaughton, S. Food waste within food supply chains: Quantification and potential for change to 2050. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2010, 365, 3065–3081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abeliotis, K.; Lasaridi, K.; Chroni, C. Attitudes and behaviour of Greek households regarding food waste prevention. Waste Manag. Res. 2014, 32, 237–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodgers, R.F.; Lombardo, C.; Cerolini, S.; Franko, D.L.; Omori, M.; Linardon, J.; Guillaume, S.; Fischer, L.; Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M. “Waste not and stay at home” evidence of decreased food waste during the COVID-19 pandemic from the US and Italy. Appetite 2021, 160, 105110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranmanesh, M.; Ghobakhloo, M.; Nilashi, M.; Tseng, M.-L.; Senali, M.G.; Abbasi, G.A. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on household food waste behaviour: A systematic review. Appetite 2022, 176, 106127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Bux, C. Food waste in Italian households during the COVID-19 pandemic: A self-reporting approach. Food Secur. 2021, 13, 25–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicarelli, V.; Lagioia, G.; Sampietro, S.; Bux, C. Has the COVID-19 pandemic changed food waste perception and behavior? Evidence from Italian consumers. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2022, 82, 101095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaco, R.; Hoehn, D.; Laso, J.; Margallo, M.; Ruiz-Salmón, J.; Cristobal, J.; Kahhat, R.; Villanueva-Rey, P.; Bala, A.; Batlle-Bayer, L. Food waste management during the COVID-19 outbreak: A holistic climate, economic and nutritional approach. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 742, 140524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garske, B.; Heyl, K.; Ekardt, F.; Weber, L.M.; Gradzka, W. Challenges of food waste governance: An assessment of European legislation on food waste and recommendations for improvement by economic instruments. Land 2020, 9, 231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations (UN). A/RES/70/1, Resolution Adopted by the General Assembly on 25.09.2015. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations (UN). Adoption of the Paris Agreement. In United Nations Climate Change Secretariat (UNFCCC); FCCC/CP/2015/L. 9/Rev. 1; United Nations (UN): New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Food Wastage Footprint & Climate Change; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, E.; Milner-Gulland, E.; Knight, A.T.; Ling, M.A.; Darrah, S.; van Soesbergen, A.; Burgess, N.D. Status and trends in global ecosystem services and natural capital: Assessing progress toward Aichi Biodiversity Target 14. Conserv. Lett. 2016, 9, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). SAVE FOOD: Global Initiative on Food Loss and Waste Reduction. Available online: http://www.fao.org/save-food/en (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Technical Platform on the Measurement and Reduction of Food Loss and Waste. Available online: http://www.fao.org/platform-food-loss-waste/en/ (accessed on 15 March 2025).

- European Commission. Closing the Loop—An EU Action Plan for the Circular Economy. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, t.C., the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. 2015. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52015DC0614 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- European Parliament and Council. Directive (EU) 2018/851 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018 amending Directive 2008/98/EC on waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 2018, L150, 109–140. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32018L0851 (accessed on 24 November 2024).

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2019/1241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2019 on the Conservation of Fisheries Resources and the Protection of Marine Ecosystems Through Technical Measures, Amending Council Regulations (EC) No 1967/2006, (EC) No 1224/2009 and Regulations (EU) No 1380/2013, (EU) 2016/1139, (EU) 2018/973, (EU) 2019/472 and (EU) 2019/1022 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Repealing Council Regulations (EC) No 894/97, (EC) No 850/98, (EC) No 2549/2000, (EC) No 254/2002, (EC) No 812/2004 and (EC) No 2187/2005. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2019/1241/oj/eng (accessed on 25 November 2024).

- European Commission. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on the Financing, Management and Monitoring of the Common Agricultural Policy and repealing Regulation (EU) No 1306/2013. COM(2018) 393 Final, June 1, 2018. Brussels: European Commission. 2018. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52018PC0393 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- European Union. Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers; European Union: Brussels, Belgium, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. EU Platform on Food Losses and Food Waste: Terms of Reference (ToR) from 01.07.2019. Brussels: European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://food.ec.europa.eu/safety/food-waste/eu-actions-against-food-waste/eu-platform-food-losses-and-food-waste_en (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- European Commission. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, t.C., the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions: The European Green Deal (COM(2019) 640 Final). Brussels: European Commission. 2019. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A52019DC0640 (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- European Commission. Commission Delegated Decision (EU) 2019/1597 of 3 May 2019 supplementing Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council as regards a common methodology and minimum quality requirements for the uniform measurement of levels of food waste. Off. J. Eur. Union 2019, L248, 77–85. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32019D1597 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Law on Waste Management. Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia 36/2009, 14/2016, 95/2018 and 35/2023. Available online: https://www.paragraf.rs/propisi/zakon_o_upravljanju_otpadom.html (accessed on 28 November 2024).

- Waste Management Program of the Republic of Serbia for the Period 2022-2031. Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, No. 12/22. Available online: http://demo.paragraf.rs/demo/combined/Old/t/t2022_02/SG_012_2022_010.htm (accessed on 29 November 2024).

- Waste Generation Prevention Plan in the Republic of Serbia, 2025 Official Gazette of R. Serbia February No. 18/2025. Available online: https://www.ekologija.gov.rs/sites/default/files/2025-03/plan_prevencije_stvarana_otpada_1.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Regulation on Establishing a plan to Reduce Packaging Waste for the Period from 2025 to 2029. Which Establishes National Goals for Improving the Management of Municipal Packaging Waste in Serbia in Accordance with the Principles of Circular Economy, Official Gazette R. Serbia No. 21/2025; Official Gazzette of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2025.

- The Circular Economy Development Program in the Republic of Serbia for the Period 2022–2024. Official Gazette of the Republic of Serbia, No. 137/2022. Available online: https://pravno-informacioni-sistem.rs/eli/rep/sgrs/vlada/drugiakt/2022/137/1 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Strategy for Agriculture and Rural Development of the Republic of Serbia for the Period 2014–2024; Official Gazzette of the Republic of Serbia: Belgrade, Serbia, 2014.

- Ministry of Environmental Protection. Roadmap for Circular Economy in Serbia. 2020. Available online: https://circulareconomy.europa.eu/platform/en/strategies/roadmap-circular-economy-serbia (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Guidelines for the Implementation of the Green Agenda for the Western Balkan. Available online: https://neighbourhood-enlargement.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2020-10/green_agenda_for_the_western_balkans_en.pdf (accessed on 3 December 2024).

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) Vodič za Pravilno Upravljanje Otpadom od Hrane. Available online: https://naled.rs/htdocs/Files/06221/Vodic_za_pravilno_upravljanje_Otpadom_od_hrane.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) (2020) Projekat Upravljanje Otpadom u Kontekstu Klimatskih Promena. Smernice za Lanac Vrednosti za Korišćenje Otpada od Hrane iz HORECA Sektora Orijentisano ka Cirkularnoj Ekonomiji. Available online: https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz-sr-smernice-za-lanac-vrednosti-orijentisan-ka-ce-horeca.pdf (accessed on 4 December 2024).

- Kuderer, A.M. White Paper on Waste-to-Energy in Serbia. Environmental Protection Engineers, Novi Sad. 2024. Available online: https://www.activity4sustainability.org/bela-knjiga-dobijanja-energije-iz-otpada-u-srbiji/ (accessed on 5 January 2025).

- Ahmed, S.; Byker Shanks, C.; Lewis, M.; Leitch, A.; Spencer, C.; Smith, E.M.; Hess, D. Meeting the food waste challenge in higher education. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2018, 19, 1075–1094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leal Filho, W.; Ribeiro, P.C.C.; Setti, A.F.F.; Azam, F.M.S.; Abubakar, I.R.; Castillo-Apraiz, J.; Tamayo, U.; Özuyar, P.G.; Frizzo, K.; Borsari, B. Toward food waste reduction at universities. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 26, 16585–16606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derqui, B.; Grimaldi, D.; Fernandez, V. Building and managing sustainable schools: The case of food waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 243, 118533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, V.; Jones, M.; Ruge, D. Integrating Food into the Curriculum. Prim. Sci. 2021, 168, 5–8. [Google Scholar]

- Aramyan, L.H.; Beekman, G.; Galama, J.; van der Haar, S.; Visscher, M.; Zeinstra, G.G. Moving from niche to norm: Lessons from food waste initiatives. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attiq, S.; Habib, M.D.; Kaur, P.; Hasni, M.J.S.; Dhir, A. Drivers of food waste reduction behaviour in the household context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2021, 94, 104300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, P.; Visvanathan, C. Sustainable management practices of food waste in Asia: Technological and policy drivers. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 247, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chia, D.; Yap, C.C.; Wu, S.L.; Berezina, E.; Aroua, M.K.; Gew, L.T. A systematic review of country-specific drivers and barriers to household food waste reduction and prevention. Waste Manag. Res. 2024, 42, 459–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vittuari, M.; Herrero, L.G.; Masotti, M.; Iori, E.; Caldeira, C.; Qian, Z.; Bruns, H.; van Herpen, E.; Obersteiner, G.; Kaptan, G. How to reduce consumer food waste at household level: A literature review on drivers and levers for behavioural change. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselá, L.; Králiková, A.; Kubíčková, L. From the shopping basket to the landfill: Drivers of consumer food waste behaviour. Waste Manag. 2023, 169, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangherlin, I.d.C.; De Barcellos, M.D. Drivers and barriers to food waste reduction. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 2364–2387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasavan, S.; Siron, R.; Yusoff, S.; Fakri, M.F.R. Drivers of food waste generation and best practice towards sustainable food waste management in the hotel sector: A systematic review. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 48152–48167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Secer, A.; Masotti, M.; Iori, E.; Vittuari, M. Do culture and consciousness matter? A study on motivational drivers of household food waste reduction in Turkey. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 38, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thyberg, K.L.; Tonjes, D.J. Drivers of food waste and their implications for sustainable policy development. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2016, 106, 110–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GIZ. Circular Economy Oriented Value Chain Guideline for HORECA Food Waste Utilisation. 2020. Available online: https://www.giz.de/en/downloads/giz-en-circular-economy-oriented-value-chain-guideline-horeca.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Parry, A.; Bleazard, P.; Okawa, K. Preventing Food Waste: Case Studies of Japan and the United Kingdom; OECD: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Love Food Hate Faste. Available online: https://www.lovefoodhatewaste.com/ (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Love Food Hate Waste (WRAP, UK). Available online: https://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/environment/waste-management/organic-waste/casestudies/cs_1_wrap.pdf (accessed on 8 January 2025).

- Interreg Central Europe. Report on Status Quo of Food Waste Prevention and Management. Available online: https://programme2014-20.interreg-central.eu/Content.Node/STREFOWA/D.T1.1.1-SQ-Report-final-2.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- The Stop Food Waste Programme 2009-2021. Available online: https://ctc-cork.ie/projects/the-stop-food-waste-programme-2009-2021/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Zero Hunger Zero Waste. Available online: https://www.thekrogerco.com/sustainability/zero-hunger-zero-waste/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Think, Eat, Save: UNEP, FAO and Partners Launch Global Campaign to Change Culture of Food Waste. Available online: https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/think-eat-save-unep-fao-and-partners-launch-global-campaign-change (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- UN Enviroment Programme. Think Eat Save Tracking Progress to Halve Global Food Waste. Available online: https://digitallibrary.in.one.un.org/TempPdfFiles/28372_1.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Welivita, I.; Wattage, P.; Gunawardena, P. Review of household solid waste charges for developing countries–A focus on quantity-based charge methods. Waste Manag. 2015, 46, 637–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]