Abstract

Urban-rural imbalance impedes sustainable development in modernizing nations. This paper examines China’s urban-rural relations via symbiosis theory, building a model and index system to assess urban-rural symbiosis, contributing to SDG 11 (Sustainable Cities and Communities) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities). Focusing on 31 provinces and cities in China, this study uses data from 2022 and the entropy weight method to evaluate the current urban-rural symbiosis relationship in China. Findings highlight unsustainable urban-rural relations: Firstly, imbalances persist between urban and rural areas in China regarding resource allocation, public services, and development speed, hindering sustainable and equitable development. Secondly, spatial differentiation and insufficient flow of factors significantly restrict the development of urban-rural symbiosis, impacting resource efficiency and balanced regional growth. Thirdly, the levels of cultural and ecological symbiosis between urban and rural areas are low and uneven, posing risks to environmental sustainability and social cohesion. Recommendations include strengthening rural units for collaboration, using counties to improve the symbiosis interface, and optimizing the symbiotic environment. These measures aim to guide, incentivize, coordinate, and protect positive urban-rural relations, driving symbiosis towards a more balanced, inclusive, sustainable urban-rural development model for China, offering insights for similar nations.

1. Introduction

Sustainable development in modernizing nations is significantly challenged by urban-rural imbalance. This not only restricts balanced socio and economic development but also poses a critical challenge to achieving sustainable development. Notably, in China, the world’s largest developing nation, the urban-rural gap is particularly acute. Long et al. [1] examined the rural transformation and development in China based on three evaluation index systems: rural development level, rural transformation level, and urban coordination level. Fang et al. [2] analyzed the main factors, driving mechanisms, fundamental patterns, and sustainability of China’s integrated urban-rural development from a theoretical perspective. They developed measurement standards for integrated urban-rural development and proposed a triangular model. Zhang et al. [3] used an evolutionary game model to analyze the changes in the values of peak Nash equilibrium and cumulative Nash equilibrium in each province, as well as the degree of integrated development in urban-rural areas of the country. They found that the level of integration is closely related to provincial differences. The literature on the development of urban-rural relations in China is extensive, providing strong theoretical and methodological support for this paper. However, some unresolved issues still require further exploration.

Firstly, research on urban-rural relations mainly focuses on macro-level narratives or remains at the micro-level of quantitative analysis. While some scholars combine these approaches, there still needs to be more theoretical integration with theories from other disciplines. A profound analysis of the characteristics of urban-rural relations in China, along with the development of a systematic and localized theoretical framework, is still needed. Secondly, academic discussions on urban-rural relations have long been confined to the socioeconomic domain. Although there are geographical studies on urban-rural relations, these often focus on spatial dilemmas and pattern evolution. More research is needed to examine and position the logical relationships between urban and rural areas from a complex, holistic network ecology perspective.

Since 2003, China has introduced coordinated urban-rural development policies to address the imbalance between urban and rural areas. With continuous improvements in policy frameworks, urban-rural relations in China have entered a new phase of integration. In this context, it is essential to deeply understand the connotations of urban-rural integration from a theoretical perspective and provide a theoretical explanation. Symbiosis theory, proposed by biologist Anton de Bary and widely used in political science, ethnography, economics, sociology, and other fields, offers a new framework for explaining the relationship between urban and rural integration in China. Symbiosis theory reveals the complex, multifaceted, dynamically evolving interdependence and co-evolution between different entities or systems. This relationship is reflected not only in diverse symbiotic units and patterns but also in the continual adjustments and evolution driven by environmental changes and internal interactions, thereby advancing the sustained development of the symbiotic system. The complexity, diversity, and dynamism of urban-rural systems align significantly with the concepts of symbiosis theory. Exploring urban-rural relations from the perspective of symbiosis theory can provide a systemic explanation of the interactions and evolutionary patterns between urban and rural areas, offering new insights into the development of urban-rural relations.

The Chinese government attaches great importance to integrated urban-rural development, elevating it to a national strategy. Symbiosis theory aligns closely with the policy goals of coordinated urban-rural development and common prosperity advocated by the Chinese government. Concurrently, scholars in China have actively explored innovative models based on symbiosis within the context of China’s urban-rural integration practices. Wu [4] utilizes the “symbiosis theory” from ecology to theoretically interpret China’s urban-rural relations from a political ecology perspective, constructing an explanatory framework for “symmetric and mutually beneficial symbiotic development between urban and rural areas” in the new era. Liu [5] reflects on the epistemological and axiological limitations of long-standing perceptions regarding China’s “urban-rural education” issue, asserting that symbiosis philosophy and values are necessary choices for China’s educational outlook in the new period and that a Chinese urban-rural education symbiosis view must be constructed in a philosophical or methodological sense.

Zhang [6] argues that in integrated urban-rural development, urban and rural cultures should be mutually respectful, mutually beneficial and complementary, fully integrated, co-prosperous and progressive, and jointly developed, i.e., symbiotic development. Zhang et al. [7] takes spatial structure as a starting point, using clustering algorithms and geographic visualization tools to depict spatial patterns of urban-rural relations in different regions and combine symbiosis theory to deeply analyze the production order inherent in China’s urban-rural spatial structure. Liu et al. [8] believes that researching the symbiotic integration of urban-rural ecology in the new era is an inevitable requirement for addressing the imbalances in China’s urban-rural development and the inadequacies in agricultural and rural development, with new-type urbanization and rural revitalization strategies serving as the two wheels driving urban-rural symbiotic integration. In summary, symbiosis theory provides a more profound and broader theoretical perspective to understand and promote China’s urban-rural integration. It transcends the limitations of traditional theories and is more in line with the practical needs of China’s urban-rural integrated development.

This paper explores the current degree of urban-rural integration, and regional disparities building on the previous discussion. It seeks to propose concrete pathways for achieving a mutual symbiosis between urban and rural areas, thereby driving symbiosis towards a more balanced, inclusive, sustainable urban-rural development model for China, offering insights for similar nations. The remainder of this paper is arranged as follows. Section 2 analyzes the symbiosis theory and constructs an urban-rural symbiosis model from three aspects: symbiotic development, symbiotic linkage, and symbiotic coordination. Section 3 introduces an indicator system, main methods, and data resources. Section 4 analyzes the empirical results. Section 5 discusses the study’s main findings. Section 6 presents the study’s main conclusions, recommendations, and limitations.

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Symbiosis Theory

Existing research has analyzed urban-rural relations from multiple perspectives, including frameworks of urban-rural linkages, new-type urbanization, and sustainability transitions, yielding substantial results. However, against the backdrop of pursuing balanced and coordinated urban-rural development, these theoretical paradigms still exhibit certain limitations in explaining urban-rural relations. Specifically, Urban-rural linkage theory, while focusing on urban-rural interactions, tends to fall into a superficial interpretation of “linkages”, simplifying urban-rural relations into unidirectional urban-driven or functional complementarity, neglecting the deeper structural embedding, shared interests, and synergistic evolution mechanisms between urban and rural areas. Although new-type urbanization theory emphasizes urban modernization and high-quality development and to some extent encompasses urban-rural integration, in practice, it still tends to view rural areas as the hinterland or supporting space for urban development, relatively overlooking their intrinsic value and development potential and the more fundamental reciprocal relationship between urban and rural areas. While possessing macro and systemic characteristics, the sustainability transition framework is somewhat broad when applied to urban-rural integration. It lacks an in-depth analysis of the specificity and complexity of urban-rural relations and a precise depiction of the reciprocal symbiotic mechanisms.

In contrast, symbiosis theory demonstrates unique advantages in interpreting urban-rural relations. Symbiosis theory emphasizes reciprocal symbiosis between urban and rural areas, rather than unidirectional dominance and dependence, and breaks through the traditional unidirectional development thinking. More importantly, symbiosis theory not only focuses on the physical flow of urban and rural elements but also strives to achieve the optimal allocation of the overall functions of the urban-rural system through element integration and functional reconstruction, thereby achieving a “1 + 1 > 2” system gain effect. Therefore, this study, based on the perspective of symbiosis theory, constructs an urban-rural relations analysis framework with theoretical foresight and practical rationality.

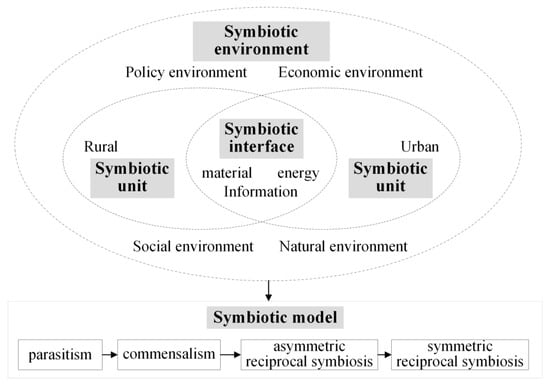

Symbiosis theory encompasses three fundamental elements: symbiotic units, symbiotic patterns, and symbiotic environments. Symbiotic units are the most basic units in a symbiotic system for producing and exchanging material, energy, and the flow of resources and elements. In the urban-rural symbiotic system, cities and villages are the fundamental symbiotic units. The symbiosis mode refers to the interaction between symbiotic units, reflecting the quality and strength of the relationship between the units, including parasitism, commensalism, asymmetric reciprocal symbiosis, and symmetric reciprocal symbiosis [9]. Symbiotic environments are the exogenous factors influencing the formation and evolution of symbiotic relationships. They encompass all environmental factors except the symbiotic units themselves [10]. The symbiotic environment in urban and rural systems includes the social environment, cultural environment, natural environment, and economic environment. The three elements (symbiotic units, symbiotic patterns, and symbiotic environments) form a co-evolving and synergistic symbiotic system through symbiotic interfaces, which refer to the medium of material, information, and energy transmission between symbiotic units. The physical spaces and interactive markets between cities and villages, among other diverse symbiotic media, together constitute the urban-rural symbiotic interface, which is the foundation for the formation and development of symbiotic relationships (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Theoretical analytical framework of urban-rural symbiosis.

2.2. Urban-Rural Symbiosis System

In alignment with the “symbiosis theory” and “system theory”, urban and rural areas are recognized as intricate, interconnected organic systems that adhere to the principles of symbiosis. To quantitatively assess the developmental trajectory and symbiotic nature of urban-rural integration in China, this study introduces the “Urban-Rural Symbiotic System (URSS)”. The URSS is delineated as a composite system encompassing economic (Economy), social (Society), spatial (Space), resource (Resources), and cultural (Culture) dimensions. This framework facilitates a nuanced understanding of the dynamic equilibrium among various subsystems, aiming to sustain a balanced distribution of interests and benefits.

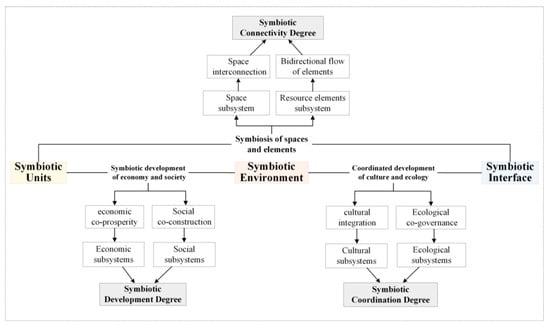

The URSS is comprised of several interrelated components, each of which is in a state of continuous evolution through interaction, progressively transitioning from a state of “parasitism” to one characterized by “symmetric reciprocal symbiosis”. Furthermore, the system’s symbiotic interface, symbiotic units, and symbiotic environment are intricately interconnected. The symbiotic environment serves as a foundational platform, offering the necessary conditions for the economic and social integration of urban and rural symbiotic units. The symbiotic interface, meanwhile, functions as the medium facilitating spatial connectivity and the exchange of factors among these symbiotic units. Concurrently, the dynamic interplay between the urban-rural symbiotic interface and the symbiotic environment is instrumental in fostering the harmonious development of both the cultural and ecological dimensions of the urban-rural landscape (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Theoretical model of China’s urban-rural symbiosis system (URSS).

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Construction of the Indicator System

As a new indicator of social progress, the degree of urban and rural symbiosis can better reflect the essential relationship between urban and rural mutual assistance, mutual benefit, and reciprocity in the new era. To effectively evaluate the realistic level of urban-rural integration and symbiosis in China, this paper focuses on the analysis dimension of “symbiosis development degree, symbiotic connectivity degree, and symbiosis coordination degree” in the symbiosis theory for empirical measurement and form a specific indicator system (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Urban-Rural Symbiosis Evaluation Indicator System.

3.1.1. Symbiotic Development Degree

The degree of symbiotic development mainly reflects the level of symbiosis between urban and rural economic subsystems and social subsystems. Within the economic subsystem, this paper uses three indicators to measure the urban-rural income structure, consumption structure, and industrial integration separately: the ratio of per capita disposable income between urban and rural areas, the ratio of urban-rural resident consumption expenditure, and the ratio of per capita GDP in secondary and tertiary sectors to primary sector. For assessing the level of urban-rural symbiotic development within the social subsystem, this paper uses six indicators: the ratio of urban to rural per capita expenditure on health care, the number of beds in health care facilities per 1000 population in urban and rural areas, the ratio of urban to rural gas penetration rate, the ratio of urban to rural water supply penetration, the ratio of full-time elementary school teachers per 10,000 population in urban and rural areas, and the ratio of full-time junior high school teachers per 10,000 population in urban and rural areas.

3.1.2. Symbiotic Connectivity Degree

The degree of symbiotic connectivity primarily reflects the level of symbiosis between the urban-rural spatial subsystem and the resource element subsystem. The strong interaction and deep connection of urban and rural spaces are crucial for the integration development of urban and rural areas in the new era. Therefore, three indicators are selected to measure urban-rural circulation and spatial connectivity: per capita private vehicle ownership, regional transportation network density [11], and passenger turnover in road transport. The mutual exchange and bidirectional flow of various “energies” between urban and rural areas are essential for their development [12]. Therefore, four indicators are selected to measure the flow of population, land, capital, and technology resources, urbanization level, land urbanization level, the ratio of agricultural, forestry, and water affairs expenditure to general public budget expenditure, and the level of agricultural mechanization.

3.1.3. Symbiotic Coordination Degree

The degree of symbiotic coordination mainly reflects the level of symbiosis between the urban-rural cultural and ecological subsystems. We choose three indicators to reflect the degree of symbiotic coordination comprehensively: the ratio of per capita expenditure on culture, education, and recreation for urban and rural residents, the ratio of township cultural stations to the total number of mass cultural institutions in the region, and the comprehensive population coverage rate of rural television programming. At the same time, we have selected three sub-indicators, including the ratio of urban and rural sewage treatment rates, the ratio of urban and rural domestic waste treatment rates, and the ratio of greening coverage in urban and rural built-up areas, which are all critical variables affecting urban-rural symbiosis governance.

3.2. Data Source

In this paper, we evaluated 31 provinces in China (excluding Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan). The data used in this study are from the China Statistical Yearbook 2022 [13], China Population and Employment Statistical Yearbook [14], China Rural Statistical Yearbook [15], China Education Expenditure Statistical Yearbook [16], and China Health Statistical Yearbook [17] issued by the National Health Commission of China to ensure their authenticity and reliability. The National Bureau of Statistics of China is the official statistical agency of China, and the statistical yearbook data it publishes undergo rigorous collection, review, and proofreading procedures, possessing high authority and standardization and serving as one of the most commonly used essential data sources for domestic economic and social research. At the same time, the China Health and Health Statistical Yearbook is an annual publication reflecting the development of China’s health undertakings and the health status of residents.

Naturally, the data used in this study may still contain potential biases and limitations due to limitations in statistical caliber and indicator definitions, potential errors in data collection and statistical processes, and restrictions on data disclosure and availability. In response to such problems, this paper has fully considered indicators’ representativeness, availability, and data quality in selecting indicators, opting for relatively mature and reliable indicators as much as possible, and has conducted necessary cleaning and preprocessing of the original data to ensure data quality. Additionally, this study employs linear interpolation to address some missing data.

This study analyzes data from 22 provinces, five autonomous regions, and four centrally administered municipalities in mainland China. In order to analyze the spatial differences, we cluster the provinces into four regions: eastern, northeastern, central, and western, according to the criteria for economic zoning in China’s National Statistical areas (the Eastern region includes Beijing Municipality, Tianjin Municipality, Shanghai Municipality, Hebei, Shandong, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong, and Hainan provinces; the Northeastern region includes Heilongjiang, Jilin, and Liaoning provinces; the Central region includes Shanxi, Henan, Hubei, Anhui, Hunan, and Jiangxi Province; the Western region includes Chongqing Municipality, Shaanxi, Gansu, Sichuan, Qinghai and Guizhou provinces, Yunnan, Ningxia Hui, and the Autonomous Region: Tibet, Inner Mongolia, Xinjiang, Uyghur, and Guangxi Zhuang. Considering the consistency of the sample data, this paper excluded Hong Kong, Macao, and Taiwan.).

3.3. Methodology for Calculating Indicator Weights

This study employs the Entropy Weight Method (EWM) for the weighting and comprehensive evaluation of 22 indicators, as it demonstrates distinct advantages over the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Principal Component Analysis (PCA) in reflecting objective reality and achieving evaluation goals. First, evaluating urban-rural integration levels requires the most objective reflection of actual conditions, minimizing interference from subjective factors. EWM, as an objective weighting method, relies entirely on the information inherent in the data to determine weights, effectively avoiding human bias and enhancing the credibility of the evaluation results. In contrast, AHP is more subjective, with weight outcomes susceptible to the influence of experts’ personal experiences and preferences, potentially lacking objectivity. Secondly, evaluating urban-rural integration levels focuses on comprehensively measuring the degree of urban-rural integration development in various regions and conducting comparative analyses based on these measurements. EWM directly outputs indicator weights, which can be used to construct a comprehensive evaluation model and calculate composite scores, thereby achieving the evaluation goals. While PCA can also be indirectly used for indicator weighting, its primary purpose is data dimensionality reduction and information extraction, differing from the direct purpose of comprehensive evaluation. PCA emphasizes identifying the main components of the data, whereas EWM emphasizes measuring the relative importance of indicators within the evaluation system.

We used the entropy weight method to determine the weights of each third-level indicator under the three subsystems: Symbiotic Development Degree, Symbiotic Connectivity Degree, and Symbiotic Coordination Degree. The specific calculation process is as follows.

3.3.1. Data Standardization: Homogenizing of Heterogeneous Indicators

The evaluation system for urban-rural integration levels typically encompasses multi-dimensional and multi-type indicators, which exhibit significant variations in units of measurement and numerical ranges, rendering direct numerical comparisons unfeasible. Therefore, data normalization is essential. This ensures that the Entropy Weight Method (EWM) effectively quantifies each indicator’s information content and importance, mitigating the influence of original data units and numerical ranges on weight allocation and achieving objectivity and rationality in indicator weight measurement. Furthermore, normalization standardizes the values of each indicator to a comparable scale, enabling aggregation operations such as weighted summation to construct a composite index that represents the overall level of urban-rural integration. Differentiated normalization processing for ‘larger-the-better’ and ‘smaller-the-better’-type indicators ensures that all indicators in the index construction point towards the positive direction of enhancing urban-rural integration, ultimately guaranteeing the scientific validity and reliability of the evaluation results [18].

The standardization formula for positive indicators is as follows:

The standardization formula for negative indicators is as follows:

where represents the dimensionless data after normalization, represents the original data of the data, and represent the maximum and minimum values of the index, respectively.

3.3.2. Calculation of Indicator Weights for Each Subsystem

After standardizing both positive and negative indicators separately, calculate the proportion of the i-th sample value for the j-th indicator:

3.3.3. Calculation of Information Entropy for Each Indicator

The entropy value of the j-th indicator (column):

Take . The coefficient of variation for the j-th indicator (column) is given by , where n is the number of samples for the indicator, which is 32 in this paper, and m represents the number of indicators, totaling 15 in this paper.

3.3.4. Determination of the Weight for Each Indicator

The weight of the j-th indicator (column) is as follows:

3.4. Measurement of Urban-Rural Symbiosis Level

The entropy weight method sequentially calculates the composite index score of urban-rural symbiosis by following the steps outlined below. First, calculate the score for each indicator, where wj denotes the weight of the respective indicator and represents the score of the urban-rural symbiosis index for that particular indicator:

Then, calculate the symbiotic development degree score, symbiotic association degree score, and symbiotic coordination degree score of region i. In this case, when m = 1, n = 9, and s = 1, the comprehensive score of symbiotic development degree of region i is obtained; when m = 2, n = 16, and s = 10, the comprehensive score of symbiotic association degree of region i is obtained; when m = 3, n = 22, and s = 17, the comprehensive score of symbiotic coordination degree of region i is obtained; when m = 4, n = 30, and s = 1, get the composite index value of urban-rural symbiosis in region i:

4. Results

4.1. Comprehensive Analysis of Urban-Rural Symbiosis in China

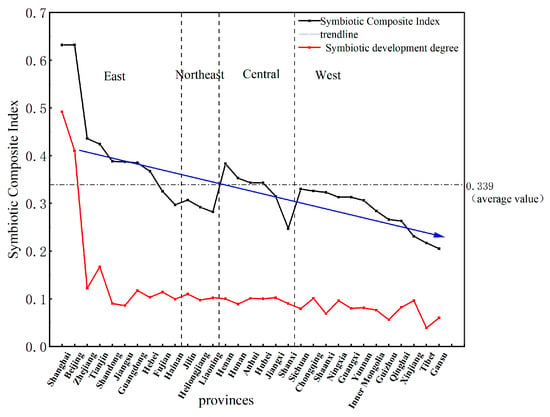

Based on the Chinese Geographical and Economic Regionalization Standards and the final measurement results, the 2022 Composite Score of the Urban-Rural Symbiosis Index and the Regional Trend Comparison Chart (Figure 3) were generated using Origin plotting software (version 2021). The graph illustrates the regional variations in the urban-rural symbiosis index across Chinese provinces, categorized into Eastern, Northeastern, Central, and Western regions. The horizontal axis represents the provinces, while the vertical axis denotes the composite score of the urban-rural symbiosis index. A black line depicts the 2022 trends in the composite score, with a blue trend line indicating the overall trajectory, averaging 0.339 (represented by a dashed line in the text). A red line represents the 2022 trends in the urban-rural symbiosis development composite score. These trends provide a comprehensive overview of the level and disparities in urban-rural symbiosis across China’s regions and provinces, laying a practical foundation for formulating national strategies to promote the urban-rural symbiotic level.

Figure 3.

Analysis of regional differences in urban-rural co-development in 2022.

During a period of high-quality development, China’s urban-rural relationship has entered a new stage in terms of development status and policy promotion. From the general trend line, the urban-rural regional symbiosis index shows a decreasing trend of “East-Northeast + Central-West”. Figure 3 clearly illustrates that most provinces in the eastern region have a composite index above 0.339, indicating a relatively strong capacity for urban-rural mutual benefit and symbiosis. Only the Henan and Hunan provinces have scores above the average in the central region, reflecting an essential capability for urban-rural mutual benefit and symbiosis. Conversely, the composite index scores for the northeastern, western, and remaining central provinces are below the national average. In the western region, half of the provinces have scores below 0.3, indicating less favorable conditions for balanced urban-rural development and a low level of symbiosis, which is why the Chinese government has vigorously promoted the revitalization of the countryside in the western region, an essential task in promoting shared prosperity. Furthermore, the urban-rural development gap in the northeastern region remains substantial, which has become one of the main obstacles to the region’s development and revitalization strategy [19].

Section 2 identifies that the economic and social development subsystems influence urban-rural symbiosis. The ultimate goal of urban-rural symbiosis in China is to completely eliminate the dual economic and social disparities between urban and rural areas while maintaining functional differences. Thus, by comparing the urban-rural symbiotic development degree with the composite index scores in the same chart, it can be observed that the development degree of urban-rural symbiosis closely aligns with the total index level and also shows the evolution of a gradual decrease but with less fluctuation between regions. The eastern region, particularly Shanghai and Beijing, shows relatively high urban-rural economic and social symbiosis levels. In contrast, the northeastern, central, and western regions exhibit a gradual decline in symbiosis levels, with Tibet having the lowest level of urban-rural symbiosis. It indicates that continuously narrowing the economic and social disparities between urban and rural areas is a fundamental direction for advancing rural revitalization and urban-rural integration in China.

4.2. Space Differences in Urban-Rural Symbiosis Across Dimensions

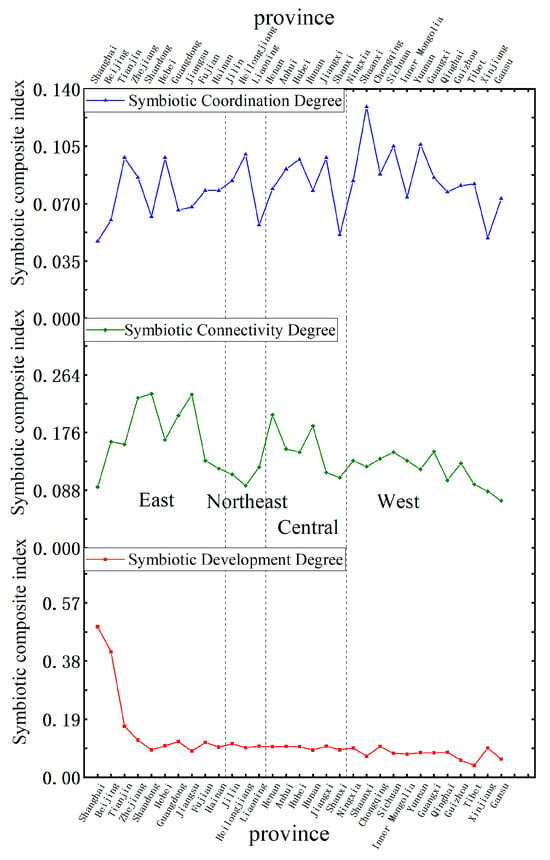

The composite scores for the three dimensions of urban-rural symbiosis in 2022 are plotted using line charts to understand urban-rural symbiosis in China better (see Figure 4). This figure reflects the balance and differences in the levels of urban-rural symbiosis in different geographic regions of China in each dimension. Similar to Figure 3, this graph delineates provinces along the horizontal axes, categorized into Eastern, Northeastern, Central, and Western regions. However, the vertical axis is segmented with 0.000 as the baseline, ascending to represent the composite scores of urban-rural symbiosis development, urban-rural symbiosis connection, and urban-rural symbiosis coordination, respectively. The trend variations for these scores are visualized through red, green, and blue lines, respectively. Building upon the analysis of the overall level of urban-rural symbiosis across China’s regions, this graph provides a more granular exploration, delving into the factors impeding urban-rural symbiosis at the development, connection, and coordination levels. This refined analysis lays the groundwork for identifying effective pathways toward enhanced urban-rural symbiotic levels.

Figure 4.

Comprehensive scores and regional trends of urban-rural symbiosis evaluation in 2022.

Regarding the degree of urban-rural symbiotic development, Beijing and Shanghai exhibit significantly higher levels of urban-rural symbiosis than other provinces and cities, while the differences in symbiosis development levels among other provinces are relatively small. Beijing is a typical mega-city in China, with the spatial characteristics of “big city, small agriculture”, “suburban Beijing, small urban area”. In recent years, Beijing has attached great importance to promoting the integrated development of urban and rural areas, narrowing the development gap between urban and rural areas, and has entered a new stage of urban and rural economic and social integration. Shanghai, as the economic center of China, has long been at the forefront of cities in the country in terms of economic aggregate, and its high level of economic development has laid a good foundation for its urban and rural symbiotic development. However, trends in symbiosis development levels reveal that most provinces with scores above 0.1 are located in eastern and southeastern China. It is potentially attributable to the significant disparities in economic development across different regions of China, which has resulted in pronounced urban-rural differences. Since implementing the Reform and Opening-up policy, China has prioritized opening up its eastern coastal areas, establishing Special Economic Zones, and adopting policies that permit early implementation and experimentation. Consequently, the eastern coastal regions took the lead in development, becoming a growth engine that propelled the sustained and rapid growth of the national economy. The eastern coastal areas have evolved into urban economic zones that transcend traditional urban-rural divisions. Within these zones, rural areas have become an intrinsic component of the urban economy, fostering a higher level of urban-rural economic and social symbiosis.

In contrast, rural areas in the central and western regions lag in economic and social development compared to urban areas due to the lack of industrialization advantages. Various resource advantages in rural areas are redirected to cities, leading to insufficient endogenous development momentum in rural areas and a lower level of urban-rural symbiosis development. Consequently, the current policy direction of the Chinese government is to vigorously promote urbanization centered on county towns to dismantle the urban-rural dual structure and advance urban-rural symbiosis.

Regarding the degree of symbiotic connectivity, provinces and cities in eastern and central China exhibit higher levels of urban-rural correlation, with most composite index scores above 0.13. With preferential financial and policy allocation, the infrastructure sector in eastern China experienced rapid development over more than a decade, building modern transportation networks and fostering the formation of numerous city clusters and metropolitan areas. This progress has enhanced urban-rural factor flows and promoted urban-rural functional complementarity and distinctive development, thereby driving rural revitalization. Conversely, infrastructure in western China has long suffered from underdevelopment. While key transportation arteries have been established, developing lower-level access routes remains insufficient, exhibiting a pattern of complete trunk lines but limited branch extensions. The insufficient development of these lower-level access routes obstructs the extension of urban-rural industrial chains into rural areas and the bidirectional flow of factors between urban and rural areas, resulting in persistently low spatial connectivity between urban and rural areas.

Notably, Shanghai, a global metropolis in China, exhibits an urban-rural symbiosis correlation coefficient of less than 0.1. This low coefficient is attributed to Shanghai, serving as the core city of its metropolitan area, wielding a strong siphoning effect, drawing population and resources from economically weaker neighboring cities and rural areas, resulting in a unidirectional outflow of resources, thereby impeding the development prospects of smaller cities and rural areas, and consequently impacting its level of urban-rural symbiosis. Concurrently, disparities in investment in infrastructure and public services contribute to a significant urban-suburban gap in Shanghai despite its status as a global metropolis in China. Furthermore, a considerable development gap exists between Shanghai and its agricultural suburbs (including Pudong). For example, in 2023, the top-ranked Pudong New Area in terms of total GDP of Shanghai’s agriculture-related suburbs will be more than 14 times as much as the eighth-ranked Jinshan District, and more than 40 times as much as the ninth-ranked Chongming District, which affects the overall urban-rural symbiosis level in the city.

In terms of the degree of symbiotic coordination, the level of urban-rural symbiosis is low across the country, and there are significant differences in the level of urban-rural symbiosis between provinces within each region. For example, the comprehensive index score for urban-rural symbiosis coordination in Tianjin, located in the east, is 2.06 times higher than that of Shanghai. In the central region, the comprehensive index score for Jiangxi Province is nearly twice that of Shanxi Province. Additionally, the differences in urban-rural symbiosis coordination between regions are even more pronounced, with Shaanxi Province in the central region scoring 2.55 times higher than Shanxi Province. At the same time, symbiosis coordination is only partially positively correlated with economic development levels. Economically developed provinces and cities such as Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangdong have urban-rural symbiosis coordination levels below 0.1.

In contrast, provinces with weaker economic development, such as Shaanxi and Yunnan, have urban-rural symbiosis coordination levels above 0.1. This result may be attributed to the following two aspects: First, it is evident that the level of urban-rural cultural symbiosis coordination is influenced not only by the disparity in economic and social development levels between urban and rural areas but also by factors such as the cultural awareness of rural residents, the ability of government departments to coordinate urban-rural cultural integration, and the in-depth exploration of traditional cultural content in rural areas. These factors affect the allocation of urban-rural cultural resources and the equality and harmony of urban-rural cultural relations, thereby impacting the level of urban-rural symbiosis coordination. Second, under the backdrop of high-quality development in China, the concept of “ecology first, green development” has become a common principle for urban and rural development. Ecological value has become the core of urban-rural integration and symbiosis, leading to a more profound “symmetrical integration and symbiosis” in the construction of urban-rural relationships in the new era. Provinces in the central and western regions, such as Jiangxi, Shaanxi, and Yunnan, which are rich in ecological resources, may improve urban-rural symbiosis coordination levels through the rational development and protection of ecological resources and the establishment of integrated ecological, economic, and industrial chains.

4.3. Analysis of Space Differences and Distribution Characteristics of Urban-Rural Symbiosis Subsystems

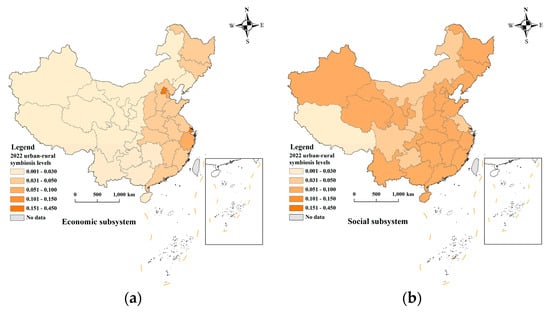

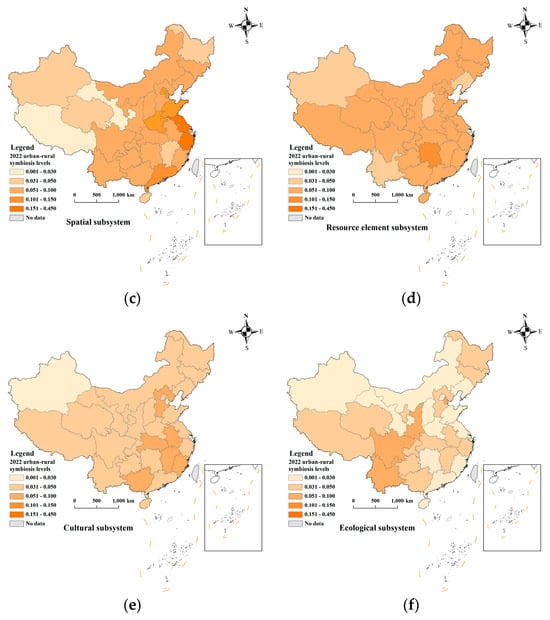

This paper employs ArcGIS Desktop software (version 10.8) to visually represent the spatial distribution of China’s urban-rural symbiosis levels across different dimensions, thereby providing empirical evidence for regional disparities and clarifying the strengths and weaknesses of each region in various aspects. Each province’s composite symbiosis index values, encompassing economic, social, spatial, resource, cultural, and ecological dimensions, are imported into ArcMap (version 10.8.1). We categorized and mapped the composite symbiosis indices using a manual classification based on data characteristics, which yielded visualized spatial variations in the six subsystems of China’s urban-rural symbiosis (Figure 5). This analysis facilitates the observation of spatial clustering phenomena in urban-rural symbiosis levels, such as the formation of core-periphery structures in high-value regions and the concentrated distribution of low-value regions, laying a foundation for proposing regional collaborative development strategies in subsequent sections.

Figure 5.

The 2022 Comprehensive Scores and Regional Differences of Urban-Rural Symbiosis Subsystems for 31 Provinces and Municipalities in China. (a) Economic subsystem; (b) Social subsystem; (c) Spatial subsystem; (d) Resource subsystem; (e) Cultural subsystem; (f) Ecological subsystem.

At the economic level (Figure 5a), economic development is crucial for establishing an excellent symbiotic relationship between urban and rural areas. Analysis shows that the national urban-rural economic symbiosis level features “higher in the east, lower in the central and western regions, high extremes, and low averages”. The urban-rural economic symbiosis levels in Shanghai and Beijing are 0.40 and 0.32, respectively, significantly higher than in other provinces. However, the overall national urban-rural economic symbiosis level still needs to be higher. Although China eliminated absolute poverty in 2021, economic disparity between urban and rural areas remains a serious issue. Further research also reveals a bidirectional interaction between urbanization development and urban-rural symbiosis levels. Shanghai and Beijing have urbanization rates of 89.39% and 87.6%, respectively, the highest in the country in 2022. At the social level (Figure 5b), except for some slower-developing areas such as Tibet and Xinjiang, the overall urban-rural social symbiosis level is relatively balanced. This balance is attributed to China’s long-term emphasis on rural health care, basic infrastructure, and compulsory education. In 2022, the consolidation rate of China’s nine-year compulsory education reached 95.5%, with the national urban-rural water supply coverage ratio average and the number of primary school teachers per 10,000 people averaging 1.2 and 0.93, respectively.

At the spatial level (Figure 5c), urban-rural development is a spatial reorganization and integration process. It can be observed that the spatial symbiosis level between urban and rural areas in China exhibits characteristics of “higher along the coast, lower inland; higher in the southeast, lower in the northwest”. Coastal regions in southeastern China, such as Guangdong, Zhejiang, and Jiangsu, benefit from favorable natural conditions and geographic advantages. Cities in these areas continuously expand into rural areas, leading to the gradual assimilation and integration of urban and rural production orders and the formation of interlocking spatial structures. In contrast, provinces in the northwest interior or those with poorer natural conditions, such as Xinjiang, Heilongjiang, Qinghai, and Gansu, have lower transportation network density and road passenger turnover, facing spatial separation and inequality challenges.

At the level of factor flow (Figure 5d), the dynamics of urban-rural relationships are driven by the movement of urban and rural elements. The analysis indicates that the flow of urban-rural elements in China is relatively balanced. This balance is due to measures such as urbanization and rural revitalization strategies that have broken the “urban-rural dual structure” in China, promoting the rapid movement of factors such as population, land, and capital between urban and rural areas. However, the intensity of element flow between urban and rural areas remains low, and there are still institutional and structural barriers to element movement, with the flow levels in Xinjiang, Shanxi, and Liaoning provinces being below 0.05. Moreover, although Shanghai is economically developed, its urban-rural factor flow level is only 0.03. The issue of uneven urban-rural development remains significant, with rural areas being mismatched with the international metropolitan image of the city in terms of environmental landscape, industrial structure, and overall strength.

At the cultural level (Figure 5e), the overall level of cultural symbiosis in China is low. This is due to low levels of rural cultural consumption, few cultural institutions, and poor service quality. Rural traditional culture has yet to be deeply explored or absorbed and is often marginalized by modern urban culture, reducing its space for survival. However, some provinces and cities, such as Anhui and Hebei, are enhancing the leading position of rural culture in the urban and rural cultural system by strengthening rural cultural facilities and promoting the development of rural cultural tourism industries.

At the ecological level (Figure 5f), two features can be observed: First, the level of urban-rural ecological symbiosis is related to the region’s concept of using ecological resources. Based on the “ecological strong province” concept, provinces such as Shaanxi, Heilongjiang, and Yunnan tend to convert green advantages into economic benefits. Second, the development of urban-rural ecological symbiosis in China needs to be more balanced. Provinces and cities with higher levels of ecological symbiosis are primarily located in the Yangtze River Basin. This may be due to China’s implementation of the horizontal ecological compensation mechanism (Horizontal ecological protection compensation refers to establishing an ecological protection compensation mechanism by the people’s governments of ecological beneficiary regions and ecological protection regions through consultation and other means to carry out horizontal ecological protection compensation between regions. The Implementation Program to Support the Establishment of a Horizontal Ecological Protection Compensation Mechanism for the Entire Yangtze River Basin was issued by China in 2021.), which has improved ecological governance in these provinces. Additionally, Beijing has a low level of ecological co-governance, with persistent environmental issues in rural areas. In 2018, 282 villages in Beijing still needed to complete rural wastewater treatment tasks, which may negatively impact the overall urban-rural ecological symbiosis level.

5. Discussion

Globally, the urban-rural development gap is not unique to any nation but is a critical issue impacting holistic progress in developing and developed countries. Consequently, nations worldwide have formulated context-specific strategies [20]. Prominent examples include the UK’s central village development, spearheaded by large-scale rural industries, the US’s interactive agro-industrial systems fostering new town development, and Japan’s plan of “industry-leading agriculture and city-promoted rural development” [21,22]. These initiatives have significantly contributed to integrated urban-rural development [23]. In non-Western societies, such as in Africa, despite urban-rural imbalances, the interactions and connections between urban and rural areas—such as circular migration and hometown associations—can serve as compensatory mechanisms to mitigate these disparities. This urban-rural “symbiotic” relationship is particularly pronounced in African societies, notably among the Igbo and Yoruba people in Southeastern and Southwestern Nigeria, respectively [24].

As a representative developing country, China has introduced numerous measures across various development stages to promote urban-rural integration policies, such as the National New Urbanization Plan (2014–2020), the Rural Revitalization Strategy Plan (2018–2022), and the National Pilot Zones for Integrated Urban-Rural Development. These policies have yielded remarkable achievements.

Urban-rural relationships in China have undergone a progressive evolution from “alleviation, improvement, interaction, coordination to integration” [2], developing a path of urban-rural relations with Chinese characteristics [25]. This paper applies symbiosis theory to analyze the development of urban-rural relationships in China from four aspects—symbiotic environment, symbiotic units, symbiotic interfaces, and symbiotic models—and identifies three dimensions—symbiotic development degree, symbiotic connectivity degree, and symbiotic coordination degree—to measure China’s current urban-rural symbiosis level. It aims to explore the changes in urban-rural relationships under the influences of political systems, economic development, and cultural heritage, offering a new perspective and a robust explanatory framework for issues such as the transformation of urban-rural relations and the “dual nature” of urban-rural disparities [26].

A scientific evaluation of the level of urban-rural interaction is a prerequisite for formulating urban-rural development strategies and addressing urban-rural issues. At present, the evaluation of urban-rural linkage mainly focuses on three aspects. The first is to judge the interaction effect between urban and rural areas by constructing the urban-rural integration index [3,27], the second is to judge the linkage effect between urban and rural areas by using the degree of coupling or the degree of coordination [19,28], and the third is to pay attention to the urban-rural development imbalance to evaluate the chasm effect between urban and rural areas to reflect the level of urban-rural integration [29,30].

Although there is no consensus on the evaluation dimensions of urban-rural relations, scholars usually evaluate the interaction effect and the level of correlation from the five classical levels of political, economic, cultural, social, and ecological evaluation [31], ignoring the spatial elements affecting the development of urban-rural relations, and less considering the impact of the flow of production elements, such as labor, capital, and technology, on the relationship between urban and rural areas. Additionally, scholars focus more on methodological application and empirical testing than the indicator systems themselves, leading to evaluative frameworks needing a solid theoretical foundation. This paper combines the theory of symbiosis with the theoretical framework of China’s urban-rural symbiosis system (URSS) based on an in-depth analysis of the development of urban-rural relations in China and further develops the indicator system, which incorporates spatial integration and elemental mobility in order to improve the accuracy and comprehensiveness of the evaluation.

The evaluation results of urban-rural symbiosis levels in this paper indicate that an asymmetric reciprocal symbiosis model characterizes urban-rural relationships in China and has yet to reach the stage of symmetric reciprocal symbiosis. This assertion is in line with other related studies. Wu [26] mentioned that socioeconomic disparities persist in China, and urban-rural relationships are in a “dual pathological symbiosis” state. “Symmetric reciprocal symbiosis” is the evolutionary direction of its urban-rural symbiosis system. Moreover, issues of asymmetric development between urban and rural areas still exist in education, spatial patterns, and factor flow [5,32,33].

Additionally, due to significant geographical differences in China, evaluating urban-rural symbiosis levels requires consideration of the current state of comprehensive development in different regions. Research by Wang and Peng et al. [34] indicated that urban-rural integration levels are higher in eastern provinces, with some developed provinces having integration levels far surpassing those in central and western provinces [35,36]. Yang et al. [37] found that Beijing, Tianjin, Shanghai, Zhejiang, and Fujian had higher levels of urban-rural integration development in 2018. The evaluation results of urban-rural symbiosis levels in this paper also show that the development level of urban-rural symbiosis in China is uneven. Eastern regions have a higher overall symbiosis level due to faster economic and social development. However, the differences in symbiosis levels across regions regarding cultural harmony and ecological governance do not correlate strongly with economic development levels, indicating more complex underlying reasons.

6. Conclusions, Recommendations, and Limitations

6.1. Conclusions

This paper measures the degree of urban-rural integration and symbiosis using the Urban-Rural Symbiosis Comprehensive Index. Based on national data from 2022, it empirically tests the urban-rural symbiosis relationships and their underlying elements during the high-quality development phase. The main research findings are as follows:

(1) China’s urban-rural symbiosis model is marked by asymmetrical reciprocity.

Although the development pace between urban and rural areas has accelerated compared to the past, sustained implementation of development strategies remains the only way to address the significant “double gap”. Issues such as uneven element allocation, unequal public services, and asynchronous development still exist, preventing the achievement of symmetric reciprocal symbiosis. Additionally, urban-rural development in China needs to be more balanced, with low symbiotic connection and coordination levels, mainly due to the need for more capacity for rural economic development. Although rural industries have established a development foundation with policy support, issues such as short industrial chains, low levels of integration, and inadequate technological advancement persist, and farmers’ incomes are lower and less diverse than urban residents. In addition, as an essential unit subject in urban-rural symbiosis, the subjectivity of the rural has not been effectively activated and embodied in urban-rural symbiosis and faced with challenges such as the destruction of the social order and the extinction of traditional culture in the development of urbanization, the rural development unit has gradually become objectified in the process of obedience and dependence on the city.

(2) The urban-rural symbiosis interface acts as a medium for symbiotic interactions, facilitating spatial connections and the exchange of resources between urban and rural units [38]. However, spatial differentiation and insufficient element flow between urban and rural areas are significant obstacles to China’s current development of urban-rural symbiotic associations.

On the one hand, the continuous expansion of urban areas during China’s urbanization process has encroached upon and squeezed rural production and living spaces, leading to an unequal spatial structure and layout. There are significant disparities in social space rights and welfare protection between urban and rural residents, with low levels of spatial integration and a lack of a cohesive urban-rural development spatial system. On the other hand, although government policies have facilitated a shift from a unidirectional flow of elements from rural to urban areas to a bidirectional flow between urban and rural areas, with overall improvements in element movement, some regions still face issues of insufficient and unreasonable element flow.

(3) The environment acts as a catalyst for promoting urban-rural symbiosis in the interaction between urban and rural units. However, the level of symbiosis in both the human and ecological environments between urban and rural areas in China is low and uneven.

The low degree of cultural integration between urban and rural areas can be attributed to the lack of rural cultural subjectivity and insufficient investment by managers in rural cultural initiatives. Rural culture has yet to be effectively inherited or innovatively adapted to contemporary times, and urbanization’s negation of rural cultural values has exacerbated inherent cultural conflicts between urban and rural areas. Additionally, although China has proposed the ecological development concept of “lucid waters and lush mountains are invaluable assets”, significant regional differences in the management and investment in the urban-rural ecological environment mean that balanced urban-rural ecological governance has not yet been achieved.

6.2. Recommendations

Based on the above conclusions, in order to narrow the gap between urban and rural areas in China, promote rural revitalization to form a pattern of reciprocal symbiosis between urban and rural areas, and realize China’s economic, social, cultural, ecological, and other sustainable development goals, the following suggestions are put forward:

(1) First, strengthen rural units to enhance the collaborative development capabilities of symbiotic units, continuously advance rural revitalization, and boost the endogenous driving force of rural development to reduce the urban-rural gap.

Specifically, first of all, the government should build a diversified rural industrial system, improve the rural economic level, and implement the following three strategies: On the one hand, it should develop the processing industry of agricultural products, encourage the development of intensive processing of agricultural products, and increase the added value of agricultural products. On the other hand, it should support the development of rural leisure tourism, creative agriculture (adopted agriculture, experience farms), and health care industry (combining rural natural environment and cultural resources), and promote the integration of agriculture with culture, tourism, education, health care, and other industries. For example, through the “Ten Thousand Village Renovation Project” policy, Zhejiang combines environmental remediation with industrial development in rural areas, enhances the attractiveness of rural tourism through environmental remediation, and develops eco-tourism and homestay economy. The three strategies involve actively developing new rural e-commerce, building rural e-commerce platforms, promoting online sales of agricultural products, developing smart agriculture, and improving agricultural production efficiency and management level. For example, Zhejiang is at the forefront of rural e-commerce development, producing rural e-commerce industrial clusters and Taobao villages.

Second, we should improve the policy support system and increase policy support for rural development. For example, we can give financial subsidies and tax relief to enterprises and new agricultural operators that invest in special industries in rural areas, innovate rural financial services, develop inclusive finance, and provide convenient and low-cost financing channels for developing rural industries. Finally, we should improve the comprehensive ability of farmers, reshape the subjectivity of rural areas, and establish the core position of farmers in urban and rural symbiosis. Specifically, it includes the implementation of the “new farmer” cultivation program, attracting college students, returning youth, and professional and technical personnel to invest in rural industrial development, providing entrepreneurship training, technical guidance, and other services to cultivate new agricultural business entities; It should deepen the reform of the rural land system, clarify farmers’ contracted land management rights, explore practical ways to realize the “separation of three rights”, protect farmers’ land rights and interests, and provide stable expectations and guarantees for farmers to participate in rural revitalization; It should also build an interest linkage mechanism, establish an interest linkage mechanism between new agricultural business entities and farmers, such as order agriculture, share cooperation, profit sharing, so that farmers can share more industrial value-added income.

The third critical aspect centers on enhancing the comprehensive capabilities of farmers, fundamentally reshaping rural agency, and unequivocally establishing farmers’ central and pivotal role in fostering mutually beneficial urban-rural symbiosis. To elaborate, this multifaceted endeavor intrinsically encompasses implementing a comprehensive “New Farmer Cultivation Program” meticulously designed to proactively attract university graduates, returning youth, and specialized technical personnel to actively engage in diverse rural industrial development initiatives. This program should strategically provide comprehensive entrepreneurship training, targeted technical guidance, and a wide array of related support services expressly designed to effectively cultivate and empower new agricultural business entities. Furthermore, decisively deepening the reform of the rural land system remains indispensable. This necessitates definitively clarifying farmers’ land contractual management rights, diligently exploring effective and viable implementation forms of the “separation of three land rights” framework to rigorously safeguard farmers’ fundamental land rights, and proactively providing demonstrably stable expectations and robust guarantees meticulously designed to demonstrably bolster farmers’ confident and active participation in comprehensive rural revitalization endeavors. Ultimately, establishing robust and equitable benefit-sharing mechanisms is paramount. This entails strategically creating synergistic linkages between new agricultural business entities and individual farmers, effectively leveraging diverse models such as order agriculture, share cooperation, and profit sharing, thereby demonstrably enabling farmers to equitably share a greater proportion of the substantial industrial value-added benefits generated.

(2) Next, the urban-rural symbiosis interface can be improved using counties as spatial carriers.

Based on the actual development conditions of the regions, develop strategies to open up channels for urban-rural element exchange systematically. First, using Chinese counties is a crucial interface and entry point for promoting urban-rural symbiosis. Advance the spatial layout of counties and optimize spatial structures to build an urban-rural integration development system centered on county towns, with towns as nodes and rural areas as the hinterland, thereby promoting urban-rural spatial integration through integrated planning. Second, strategies should be developed to facilitate the orderly and sufficient flow of elements by considering the weights of different element flows in urban-rural symbiosis and the disparities in element flow between regions of varying development levels. In this paper, technological elements have the highest weight among the four indicators measuring urban-rural symbiosis, followed by capital elements, consistent with existing research indicating that capital elements have entered an active promotion phase in urban-rural element flow [39]. For example, technological elements have a significant share in their urban-rural symbiosis in developed regions such as Beijing, Tianjin, and Zhejiang. Therefore, it is necessary to guide the flow of technological and capital elements from cities to rural areas.

An exemplary case is Ninghai County, Ningbo, which pioneered the “public transport postal route” and “public transport mailbox” urban-rural logistics model. This initiative effectively addresses the operational inefficiencies and high terminal costs of rural logistics, facilitating urban-rural resource flow. Furthermore, Jingning She Autonomous County, leveraging its county-level platform, has implemented systemic and integrated reforms. Through institutional and mechanism innovation, ecological value transformation, infrastructure coordination, and smart governance empowerment, it has established an urban-rural symbiotic pattern characterized by efficient urban-rural factor flow, deep industrial integration, joint environmental protection and governance, and collaborative and efficient governance. These reforms demonstrate the county’s pivotal role as a “bridge” in urban-rural integration.

(3) Finally, optimize the urban-rural symbiosis environment to enhance positive environmental effects and curb negative impacts.

In promoting urban-rural cultural cohesion, the cultural subjectivity of villages can be upgraded by inheriting outstanding traditional local culture, strengthening the protection and utilization of traditional villages, and enriching the spiritual and cultural life of villages, on the basis of which a mechanism for mutual support between rural and urban cultures has been established, to promote the two-way integration of urban and rural cultures. In promoting urban-rural ecological governance, it is necessary to focus on the ecological protection compensation system to promote the active protection and management of urban and rural ecological environments in all regions. Additionally, regions should leverage their ecological resource advantages to organically combine ecological management and the development of regional industries through policy, market, and technological innovations, creating a new ecological economic pathway centered on realizing the value of ecological products.

6.3. Limitations

Due to both subjective and objective reasons, the study inevitably has some limitations. Firstly, while this research provides a comprehensive analysis of the evolution of urban-rural symbiosis in China, it measures the current level of urban-rural symbiosis from a cross-sectional perspective. However, due to limitations in national statistical data, it only uses data from 2022 and overlooks data from other years. Secondly, the study focuses on provincial-level regions, necessitating further research at the municipal and county levels. Finally, as urban-rural connections have become an international focal point, it is essential to consider the commonalities and differences in urban-rural development across different societies and to extend the conclusions to other countries or regions.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, P.W.; Methodology, P.W.; Formal analysis, Z.S.; Data curation, B.G.; Writing—original draft, P.W.; Writing—review & editing, B.G. and Z.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province grant number No. 2023LS06. And The APC was funded by Social Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Long, H.; Zou, J.; Pykett, J.; Li, Y. Analysis of rural transformation development in China since the turn of the new millennium. Appl. Geogr. 2011, 31, 1094–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, C. On integrated urban and rural development. J. Geogr. Sci. 2022, 32, 1411–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Fan, Y.; Fang, C. When will China realize urban-rural integration? A case study of 30 provinces in China. Cities 2024, 153, 105290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. Symmetry Mutualism of Urban and Rural Areas:A New Theoretical Framework of Urban-Rural Relationship. Issues Agric. Econ. 2018, 4, 14–22. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y. Urban and rural education symbiosis: An exploration of educational philosophy. Educ. Res. Mon. 2017, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. The Inherent Logic and Promotion Tactic of the Symbiotic Development of Urban-Rural Culture—From the Interculturality Perspective. Soc. Sci. Xinjiang 2019, 39, 88–95+147–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, B.; Duan, M.; Tan, T. Spatial structure, production order, and construction path of Urban-rural communities: A symbiotic perspective. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2023, 23, 97–104. [Google Scholar]

- Liu Yubang, S.H. Study on ecological integration and symbiosis between urban and rural areas in China from the perspective of green development. Rural Econ. 2020, 38, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, H.; Zhuang, T. On theIntegration Development of Rural Industry from the Perspective of Symbiosis Theory:Symbiosis Mechanism Practical Dilemma and Promotion Strategy. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 8, 68–76. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, H.; Jiao, H.; Ye, L. Theoretical framework and research emphasis of integrated symbiotic network system in metropolitan area. Geogr. Res. 2023, 42, 475–494. [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S.; Chan-Kang, C. Regional road development, rural and urban poverty: Evidence from China. Transp. Policy 2008, 15, 305–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Zhou, G.; Tang, C.; Fan, S.; Guo, X. The spatial organization pattern of urban-rural integration in urban agglomerations in China: An agglomeration-diffusion analysis of the population and firms. Habitat Int. 2019, 87, 54–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China Division of Population and Employment Statistics. China Population and Employment Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- National Bureau of Statistics of China Department of Rural Socio-Economic Survey. China Rural Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Technology and Cultural Industries Statistics Department Social Science, National Bureau of Statistics of China. China Education Expenditure Statistical Yearbook; China Statistics Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- National Health Commission of China. China Health and Health Statistical Yearbook; China Union Medical College Press: Beijing, China, 2022.

- Liu, X.; Luo, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Guo, L. Research on the Measurement and Effects of Urban–Rural Integration and Modernization in National Central Cities. Soc. Indic. Res. 2024, 173, 827–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, X.; Sun, P.; Liu, H.; He, J. Spatial-temporal Evolution of the Urban-rural Coordination Relationship in Northeast China in 1990–2018. Chin. Geogr. Sci. 2021, 31, 429–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Li, Y. Revitalize the world’s countryside. Nature 2017, 548, 275–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y. Geography of New Countryside Construction in China; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Long, H.; Hu, Z.; Zou, J. The evolution of rural policy in Britain and its policy implications for rural development in China. Geogr. Res. 2010, 29, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar]

- Zhan, L.; Wang, S.; Xie, S.; Zhang, Q.; Qu, Y. Spatial path to achieve urban-rural integration development− analytical framework for coupling the linkage and coordination of urban-rural system functions. Habitat Int. 2023, 142, 102953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Victor, O.U.; Hope, E.N. Rural–Urban ‘Symbiosis’, community self-help, and the new planning mandate: Evidence from Southeast Nigeria. Habitat Int. 2011, 35, 350–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Hu, Z. Approaching Integrated Urban-Rural Development in China: The Changing Institutional Roles. Sustainability 2015, 7, 7031–7048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X. Urban and rural symbiotic development: From morbid to normal. Acad. Bimest. 2014, 30–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, P.; Yang, Y.; Ye, W.; Liu, L.; Gu, X.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y. Study on the Efficiency, Evolutionary Trend, and Influencing Factors of Rural–Urban Integration Development in Sichuan and Chongqing Regions under the Background of Dual Carbon. Land 2024, 13, 696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.-G.; Reid, B.J.; Meharg, A.A.; Banwart, S.A.; Fu, B.-J. Optimizing Peri-URban Ecosystems (PURE) to re-couple urban-rural symbiosis. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 586, 1085–1090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lu, S.; Chen, Y. Spatio-temporal change of urban–rural equalized development patterns in China and its driving factors. J. Rural Stud. 2013, 32, 320–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Kang, W.; Zhang, R.; Xia, J. The Gap between Urban and Rural Development Levels Narrowed. Complexity 2020, 2020, 4615760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Zeng, Z.; Xi, Z.; Peng, Z.; Chen, G.; Zhu, X.; Chen, X. Research on Sustainable Urban–Rural Integration Development: Measuring Levels, Influencing Factors, and Exploring Driving Mechanisms—Taking Eight Cities in the Greater Bay Area as Examples. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G.; Li, Q. From Separation to Integration: Reflection on Spatial Justice of Urban-Rural Relations in the New Era. J. Soc. Theory Guide 2021, 43, 10–16+27. [Google Scholar]

- He, R.; Yang, H.; Zhang, H.; Yuan, C. Research on the realization path of urban-rural integration development with a perspective of urban-rural “convection”. J. Desert Res. 2022, 42, 32–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Peng, Q.; Jin, C.; Ren, J.; Fu, Y.; Yue, X. Whether the digital economy will successfully encourage the integration of urban and rural development: A case study in China. Chin. J. Popul. Resour. Environ. 2023, 21, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, P.; Wan, J. Land use and travel burden of residents in urban fringe and rural areas: An evaluation of urban-rural integration initiatives in Beijing. Land Use Policy 2021, 103, 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shan, B.; Zhang, Q.; Ren, Q.; Yu, X.; Chen, Y. Spatial heterogeneity of urban–rural integration and its influencing factors in Shandong province of China. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 14317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Bao, W.; Wang, Y.; Liu, Y. Measurement of urban-rural integration level and its spatial differentiation in China in the new century. Habitat Int. 2021, 117, 102420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, J.; Ma, Y. Research on dynamic model of urban-rural interface. Geogr. Res. 2016, 35, 2283–2297. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, H.; Zhu, X.; Guo, S.; Yuan, H. The impact of total factor mobility on rural-urban symbiosis: Evidence from 27 Chinese provinces. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).