Abstract

International distribution compels global value chain members to demand highly innovative and technological advancements in their products and processes. The members include small, medium, and large enterprises from both the manufacturing and service categories. Due to short product lifecycles and resource limitations, SMEs are unable to fulfill global value chain requirements in terms of new product development, consequently struggling to sustain manufacturing. In Saudi Arabia, more than 10% of SMEs currently belong to the manufacturing sector, and the majority continue to use conventional manufacturing technologies. Against this backdrop, and to strengthen existing SMEs and enhance their growth, the author conducted a comprehensive literature review on the applicability of additive manufacturing technologies in the manufacturing of various products. The review indicated that the implementation of additive manufacturing technologies faces several difficulties; thus, the author selected two manufacturing SMEs to obtain information on the necessary requirements to implement additive manufacturing technologies. The author interacted with executives from two manufacturing companies, one located in Sudair Industrial City and the other in the industrial center of Dammam. These interactions revealed that better financing, industry–academia collaborations, and stronger inter-company ties boost the adoption of additive manufacturing and support SME growth. Optimizing the use of resources, minimizing the use of materials during the production process through the use of 3D printing technologies, and optimizing time and labor costs help to enhance the economy, which is one of the main components of sustainability.

1. Introduction

Globally, the manufacturing sector is recognized as being key to boosting the economy of a country [1]. Depending on the size and output, the manufacturing sector comprises large-, medium-, and small-scale enterprises, and the majority of small-scale enterprises are suppliers to larger enterprises. However, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) are vital to the growth of the manufacturing sector [2]. To accelerate this growth, certain policies are needed to encourage the establishment of new SMEs and existing SMEs on a continual basis. As the SME sector focuses on specialized manufacturing processes and products, to sustain manufacturing and develop competitiveness [3], these enterprises require conducive industrial collaboration for functioning and growth. Industrial collaborations in terms of business partnerships, joint ventures, licensing arrangements, subcontracting, consulting advice, etc., are potentially rewarding to small and medium enterprises; thus, guiding SMEs is central to the growth of the manufacturing sector [4].

With the advent of globalization, local manufacturers are required to either be incorporated into or compete with global value chains [5]. To sustain the market, one of the competitive factors that promote such enterprises is innovation through new product development [6]. Consequently, manufacturing organizations are now required to foster the development of new products in line with existing customer requirements to attract new customers. This means that manufacturing organizations should be able to overcome short product lifecycles and stringent quality standards. Product development is a specialized production process that depends on technology and varies according to each customer’s needs. As revealed in the literature [7], the new product development process comprises several stages, such as idea generation, prototyping, testing, batch production, and design modification. These steps are repeated until customers accept the product, and each stage is time-consuming. In addition to procedural delays between various stages, the process also requires a variety of resources, including huge investments in new process and product technologies [8]. However, in the case of the SME sector, the success rate of new product development is very low [9]. Even with rapid advancements in communication systems, manufacturing organizations still face difficulties accessing information on state-of-the-art technologies and sources of machinery and equipment. Overall, in order to help sustain the manufacturing sector, it is necessary for businesses to transform themselves from conventional manual machine-oriented manufacturing to digital manufacturing [10].

The research emphasizes [11] two essential factors required for the evolution and progress of new product development in the manufacturing sector: one is to reduce the overall throughput and processing times, and the other is to incorporate functionalities to simplify the creation of complicated parts. However, developing new products within shorter timescales places pressure on manufacturers. One simple method of producing complex geometries is to incorporate 3D printing technology, popularly known as additive manufacturing, as well as controlling the process through subtractive manufacturing. Integrating these two manufacturing processes is known as hybrid manufacturing [12], which enables manufacturers to produce complex components with fewer materials and with higher precision. However, the implementation and utilization of hybrid manufacturing technology has several disadvantages, particularly in the context of medium- and small-scale organizations. One of the main negative aspects of hybrid manufacturing is that it requires the continual updating of software and related equipment.

Considering the role played by SMEs in economic development, the importance of additive manufacturing is considerable. The objective of this study is to explore the applicability of implementing additive manufacturing technology in various sectors and products in the context of SMEs. As manufacturing SMEs are constrained in terms of infrastructural resources and knowledge limitations, the author proposes initiatives to promote the implementation of additive manufacturing to enhance the growth of these enterprises.

2. SMEs and the Related Literature

2.1. Overview of SMEs in Saudi Arabia

In the global manufacturing sector, one of the countries experiencing increased growth is Saudi Arabia. Based on the volume of revenue and number of full-time employees, businesses can be categorized as micro, small, medium, or large enterprises. Monshaat’s [13] definition of enterprises, considering the number of employees and revenue ranges, is shown below in Table 1.

Table 1.

Classification of enterprises in Saudi Arabia [13].

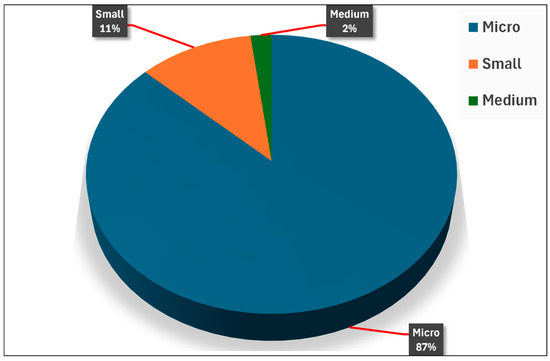

The statistical data [14] show that SMEs account for 99.5% of businesses in Saudi Arabia. The enterprises, by category, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Enterprises in Saudi Arabia by category [13].

Figure 1 shows that the majority of Saudi SMEs are in the micro-sized category. According to a recent survey report [14], 45% of employment is generated by SMEs, contributing to as much as 33% of the country’s GDP. To unlock its potential and become one of the world’s leading nations, Saudi Arabia unveiled Saudi Vison 2030 on 25 April 2016. Against the backdrop of its economic strength, investments were made in diversified fields to accelerate the growth of the industrial sector. By the end of 2030, a twofold increase in employment opportunities of up to 2.1 million is expected, along with a 35% contribution to GDP, totaling SAR 895 billion.

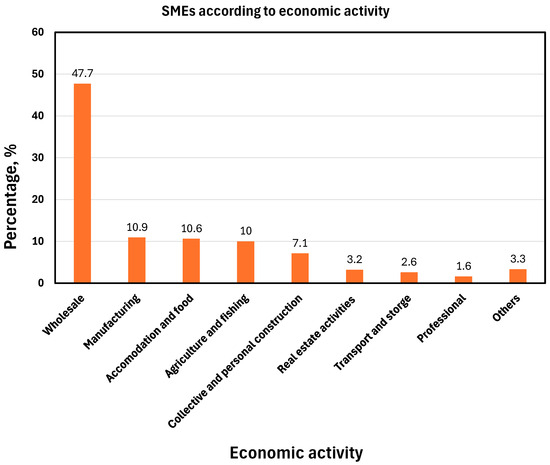

In 2017, Elhassan [15] conducted a field study to categorize the number of existing SMEs based on their economic activity. The categories of SMEs, as percentages, are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

SMEs based on economic activity [15].

Figure 2 shows that SMEs in the manufacturing sector occupy the second position in Saudi Arabia. The percentage of manufacturing SMEs totals 10.9%, indicating that there is huge potential for the establishment and growth of SMEs in this sector.

Currently, there are approximately 1.27 million SMEs in the manufacturing sector, producing various products for supply to domestic and international markets. Based on the statistics, the manufacturing sector alone contributes 6.7% of the GDP and revenues of up to SAR 287.7 billion. SMEs belong to diverse manufacturing sectors, such as aerospace and defense, pharmaceuticals and biotech, mining, chemicals, textiles, automotives, electronics, and food processing, producing a wide range of products from raw materials to finished items. The contribution made by these companies in terms of creating employment, etc. [16], is shown in Table 2. From the table, it can be seen that SMEs are involved in manufacturing and producing a variety of products.

Table 2.

Manufacturing industries and their ranking [16].

2.2. Studies on SMEs

Although there is huge potential for the growth of SMEs, studies on this topic are limited [17]. With the implementation of Vison 2030, studies on SMEs are gaining importance with the intention of accelerating entrepreneurship in all sectors. Researchers and policy makers have focused on investigating the determinants and factors influencing the growth of SMEs [18,19]. A few studies examined the aspects of financial resources [15,20], business management [19], strategic orientation [17], business knowledge, and customer service [21], and others explored business constraints [22], management leadership, and information technology [23]. All of these studies focused on managerial orientation based on the resource-based view strategy.

An exploratory study [24] on the growth of SMEs emphasizes that the main obstacle to growth is the lack of maturity in manufacturing techniques. Most SMEs still use conventional manufacturing procedures, and as a result, production continuities are interrupted, leading to increased manufacturing costs. Based on a survey, Ali [25] identified three major issues for the growth of SMEs and concluded that special attention must be paid to assist SMEs from a technological perspective. A recent study [26] found that the most important factors necessary to enhance the growth of SMEs are maintaining a high quality and delivering products on time. However, a lack of expertise and know-how is a critical issue hindering the ability of SMEs to achieve these goals. Another study [16] asserted that the implementation of technological advancements in manufacturing processes is the only way to increase productivity.

The literature on SMEs indicates that while some researchers focused specifically on identifying difficulties, others focused on suggesting measures to overcome such challenges. Comprehensively, all of the studies conducted previously were generalizable to all sectors and used the resource-based perspective. Hence, the author of this paper identifies two research gaps. While there is huge potential in the manufacturing sector, no study has investigated the growth of SMEs. Fostering new product development and the modernization of SMEs through technological advancements are key factors in sustaining the SME sector, and no specific studies that explore these applications have been carried out. With this in mind, this study explores the importance of the implementation of additive manufacturing in various manufacturing applications.

For the economic and environmental sustainability of the industrial sector, all stakeholders, including those in leadership positions in industrial, administrative, or economic institutions, must give priority to the localization of the industry with the use of additive manufacturing technologies. This modern technology reduces manufacturing time and improves environmental conservation, as less electricity is utilized since the machinery requires less time to produce the final products. In addition, the consumption of raw resources is more efficient when using additive manufacturing because wastage is reduced. AM technology depends on precise layer-by-layer building technology, which can significantly reduce material waste by enabling the more efficient use of resources [27,28]. Due to its working strategy, AM saves energy as it often requires less energy than traditional manufacturing techniques. Additionally, it can create complex, lightweight designs in industries such as automotive, aerospace, and healthcare manufacturing. This technology not only leads to enhanced product performance but also boosts resource efficiency and reduces negative environmental impacts [29,30].

Moreover, AM can foster a circular economy by enabling the recycling of materials and providing the potential for on-demand, localized production, which reduces transportation-related emissions and the need for large inventories. Through these aspects, AM aligns with the principles of sustainability, supporting both economic growth and environmental responsibility [27].

Mechater et al. [31] studied the environmental and economic effects of DMLS and CNC manufacturing processes, focusing on the effects of part size and geometry complexity. While AM can be profitable when producing complex geometries at lower costs and with less energy, CNC is still the best choice for larger and simpler geometries. For sustainability purposes and to optimize efficiency, both technologies should be integrated. In addition, the lifecycle from material production to disposal has been studied with a focus on LCA, energy modeling, and the sustainable design of the environmental impacts of additive manufacturing (AM). From the perspective of sustainability, compared to subtractive methods, AM offers considerable opportunities for sustainable production, driven by energy efficiency and redesign opportunities. In a review conducted by Gopal et al. [32], the sustainability of additive manufacturing (AM) in environmental, economic, and social dimensions was highlighted. Most studies on AM only focus on the production process and material properties without comparing them with the conventional manufacturing processes or addressing the social impacts. In addition, the authors developed a framework incorporating LCA, LCC, and the proposed S-LCA method to comprehensively assess sustainability, ensuring uniform lifecycle parameters. From this work, they concluded that AM is better from a sustainability standpoint [33].

In the following section, additive manufacturing usages and capabilities are discussed in terms of the automotive, aerospace, and healthcare industries in order to determine how these crucial sectors can benefit from additive manufacturing.

3. Research Methodology

In this research, an exploratory approach is taken to understand the use of additive manufacturing (AM) technologies and their ability to impact the sustainability agenda in industrial enterprises. The methodology employed in this study integrates both qualitative and quantitative approaches to ensure that a holistic understanding of the use and effects of AM technologies on economic, environmental, and business sustainability is obtained.

3.1. Data Collection

3.1.1. Industrial Visits and Observations

Observations of existing manufacturing scenarios and the potential for additive manufacturing implementation were made through field visits to several manufacturing facilities in multiple industrial zones. These visits helped to identify challenges, assess resource utilization, and determine the areas in which AM could be used to improve sustainability.

3.1.2. Interviews with Industry Executives

In-depth interviews were conducted with executives and decision makers from two leading manufacturing industries to gain insights into their perceptions of AM, the barriers to adoption currently in place, and the support that AM can deliver to meet their sustainability goals. Questions were asked regarding operational optimization, resource utilization, and increased economic activity.

3.1.3. Literature Review

A vast review of the existing literature, comprising journal articles, industry reports, and case studies, was undertaken to lay down a theoretical background and uncover global trends in AM for the purpose of sustainability. These were secondary data that provided the background context for the primary data collected during the field research.

3.2. Analysis Approach

To evaluate additive manufacturing’s potential for improvement, the collected data were analyzed through a comparative framework. Several key performance indicators (KPIs) were evaluated, including material consumption, energy consumption, production time, and environmental impact.

3.3. Limitations

Although the study provides valuable insights, it is limited by the industries visited and the number of executives interviewed. Furthermore, since AM is still a relatively new concept in certain industries, it was difficult to obtain relevant case studies and data.

4. Additive Manufacturing

With the advent of digital manufacturing technology, the manufacturing industry has seen phenomenal progress in activities from design to manufacturing. One such technology is additive manufacturing (AM), also known as 3D printing [34]. This technology was first developed during the 1980s, named stereolithography, and was applied in the manufacturing of products. According to an international development corporation, investments in AM during the year 2019 reached almost SAR 13.8 billion, with an average expected growth rate of 23.5% [35]. Since 2009, the manufacturing industry, particularly large enterprises, has been swift to adopt this technology, and several new developments in the processes have emerged. The technology resembles 3D printing technology, in which 3D objects are created based on the principle of depositing materials layer by layer until the product requirements are accomplished. Later, based on the mechanism of operations, various types of AM processes have evolved, such as sheet lamination [36], photo-polymerization and extrusion [37], powder bed fusion [38], beam deposition [39], direct-write technology [40], material jetting processes, and binder jetting processes. In addition, AM is currently one of the hottest topics in various research areas, including enhancing strength [41], improving surface roughness [42,43], studying erosion and corrosion properties [44], and reducing manufacturing costs, among others. These research efforts aim to address the disadvantages and limitations of AM while focusing on its improvement, making it a viable alternative to traditional manufacturing.

Additive manufacturing (AM) is changing industries, supply chains, and sustainability programs with its capability for producing complex, lightweight, and high-performance parts [45]. Additive manufacturing maximizes efficiency in supply chains, inventories, and localized production, and promotes localized production [46]. In its widespread use, its acceptance is hindered through such barriers such as variation in processes, variation in quality, high production cost, and lack of expertise among workers.

In the medical industry, AM yields significant benefits in terms of customizability and rapid production but faces barriers related to workforce expertise and efficiency in processes [47]. In spare parts manufacturing, AM reduces inventories and shortens lead times but the uncertainty about failure rates continues to serve as a strong barrier to its widespread use [48].

To counter such a challenge, new technology in the form of machine learning (ML) is assuming a critical role in AM process optimizations. ML optimizes part quality, reduces expenses, and maximizes dependability in processes through information-guided intelligence [49,50,51]. In addition, a transition towards digital spare parts supply chains (DSPSCs) is in full motion, with parts being stored in a virtual state and printed when and wherever desired. Nevertheless, such a transition is restricted through a lack of skill in operations, design, and monitoring.

Some of the new methodologies, such as ecosystem approaches, porosity analysis, in situ testing, and digital twins (DT), have tremendous potential [51]. All of them enable real-time processing and predictive maintenance, and drive transformation into motion. As AM continues to redefine traditional manufacturing and supply chain architectures, the integration of AI-powered technology, digital technology, and inter-sector collaboration will become critical in overcoming barriers and unlocking its full potential [47,50].

Additive manufacturing has completely replaced traditional process-oriented operations with product-based operations. Consequently, the implementation of additive manufacturing technology has revolutionized the manufacturing industry [52], particularly in the production of small and highly complex components. Unlike traditional manufacturing technologies, AM provides significant benefits [53] in production such as minimal material loss and enhanced functionalities, leading to huge cost reductions and energy savings. Though the inherent disadvantages of additive manufacturing have been reported [54], such as the high energy consumption and slow processes, there are few significant limitations in terms of implementation. For this reason, even SMEs can easily adopt the AM approach to manufacture products in various sectors, such as the automotive, medical and healthcare, aerospace, and defense industries. Further details of these applications are presented in the next section.

4.1. Automotive Industry

One of the key contributors to the economy in developed and developing countries is the automotive industry. In the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, more than 10 million fuel-based automotive vehicles are currently on the roads carrying passengers and goods, and this figure is expected to grow by 12% annually [55]. The Saudi government is preparing to produce 400,000 new vehicles by 2030 and to become a manufacturing hub for exports by facilitating 3–4 new original equipment manufacturers (OEMs). To ensure that these vehicles are environmentally friendly, the aim is to set up manufacturing plants, such as the Lucid Motor Corporation and Ceer Motors, to produce electric vehicles (EVs). The current development clearly shows huge opportunities for the growth of manufacturing SMEs.

Due to the customization of automotive vehicles and the rapid development of lightweight technologies, new product development is a determining factor for growth in the automotive industry. The automotive industry comprises original equipment manufacturers and replacement markets. Component manufacturing is the main source of trade to original equipment manufacturers. Manufacturing engine components such as pistons, piston rings, valves, cylinders, and gearboxes requires a series of steps, including the development of a mold, casting, heat treatment, and machining. The achievement of high product standards depends on the initial mold design, and if any changes are needed, the process should include the redesigning of the mold. Each process requires huge investment and is time-consuming. Most SMEs follow conventional design processes and the development of molds involves several steps. However, all of these steps can be eliminated, and prototypes can be produced directly and economically using AM technology. The various automotive components that can be generated using AM are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

AM technologies for manufacturing automotive components.

Three-dimensional printing is making its mark in the automotive industry by enhancing the speed of production, improving productivity, and enabling the personalization of products. Manufacturers are able to build models with great accuracy and speed, manufacture exotic or out-of-date components, and make lightweight, low-fuel-consuming parts.

For this reason, 3D-printed rapid prototypes have been applied at Ford and General Motors, enabling them to make, test, and perfect new models at lower costs and in shorter time frames. This also serves to accelerate the development of new products in the market compared to conventional methods.

Another application of 3D printing technology that car manufacturers are adopting is for the manufacture of components for discontinued models still in use. This means that companies do not have to incur costs due to buying expensive special tools or stocking large inventories. The other advantage of 3D printing is the ability to create tailor-made products. Most automotive companies design luxurious products for a limited number of people, and there is no better way of conceptualizing and realizing such designs than through additive manufacturing technology.

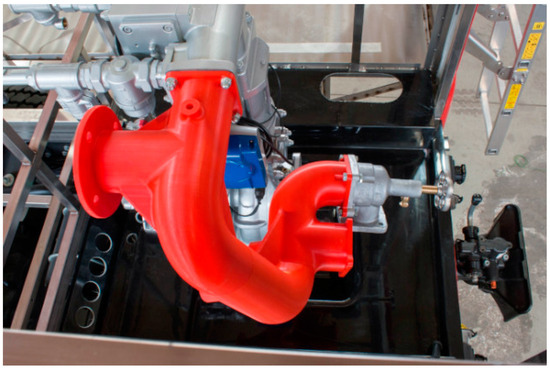

Moreover, thanks to 3D printing, vehicles that are more lightweight and fuel-efficient are being made. Manufacturers are now able to fabricate components that employ lattice structures and materials, such as aluminum alloys that are up to 80% lighter, but do not compromise on strength and safety. Put simply, metal 3D printing technology has impacted the automobile sector by making it easy to make and test new designs, fabricate difficult-to-make parts, manufacture specific parts, and develop lighter and more fuel-efficient cars. In this context, it becomes evident that the new generation of 3D printing is reshaping automotive production, making it one of the most promising enablers of progress and efficiency. Figure 3 depicts a hydraulic system inside a fire truck bearing a red colored 3D printing vacuum manifold. This manifold, which is made through a 3D printing process and fits into a pump chamber, is a prototype used to test its size, shape, and usage in the assembly of the vehicle [61].

Figure 3.

Three-dimensional printout of a fire engine’s manifold [61].

4.2. Aerospace and Military Equipment Manufacturing Industry

The aerospace sector is of great importance in Saudi Arabia and has the largest market for aircraft components in the Middle East. To fulfill the demand, more foreign direct investment is needed in order to develop the local industrial base. The development of the aerospace sector focuses on three main areas: advancing research and development, the localization of aerospace-grade materials, and the development of aerospace supply chains. According to budget statistics from 2017, Saudi Arabia has the third-largest defense budget allocation in the world, following the US and China. More than 90% of investment is spent on imports alone [62]. To minimize this spending, one of the aims of Vison 2030 is to purchase military equipment locally. In addition to maintenance and overhauling activities, local companies manufacture aerospace components and defense equipment. Recent years have witnessed an increased focus on local manufacturing, and medium enterprises are gradually becoming more involved with manufacturing components, such as Alsalam Aerospace Industries. KSA is also planning to produce vehicles with Boeing and Airbus, and Embraer have also been in discussions [55].

While maintaining accuracy, a light weight and design complexity are the main critical attributes to manufacturing aerospace and military equipment. In addition to these, generally, the components required are produced in small batches or limited numbers. Due to these attributes, additive manufacturing can be implemented successfully, irrespective of the materials, from small components to large-scale structures. Studies also indicate that, unlike other technologies, AM achieves high accuracy with minimum tolling and wastage. Another significant advantage is that AM technologies are effectively used to remanufacture worn-out components, such as the tips of turbine blades, and in engine sealing. As a result, AM is considered as an alternative technology [63], particularly in manufacturing aerospace and defense equipment. These applications are listed in Table 4.

Table 4.

AM technologies used in manufacturing aerospace and military engineering components.

The TC11 alloy (Ti–6.5Al–3.5Mo–1.5Zr–0.3Si) is widely used in various applications in aerospace industries, especially compressor disks, because of its high strain and stress resistance. Studies conducted on the TC11 alloy manufactured using laser-based additive manufacturing suggested that the tensile strength of the TC11 alloy was high due to the vertical alignment of columnar grains posed to the vertical component of the deposition axis. A thermal treatment after AM resulted in an alloy with a higher tensile strength, yield strength, and ductility than in previous studies [66].

The research on alloys such as TC21 (Ti–6Al–2Zr–2Sn–3Mo1.5Cr–2Nb) and Ti5553 (Ti–5Al–5Mo–5V–3Cr) is still ongoing. Different orientations of the TC21 samples reacted as follows after heat treatment: horizontal TC21 samples exhibited a higher strength, while vertical sections had better elongation. Ti5553 alloys with an ultimate tensile strength of 1400 MPa are suitable for high-loading parts such as aircraft landing gears, wings, and rotor structures. Due to their excellent mechanical properties, these titanium alloys find applications in the manufacture of critical aerospace structures. Figure 4 displays two components made from titanium alloys fabricated using 3D printing technology. On the left (a) is the turbine blade guider, and on the right (b) is an active cooling section of an aircraft and spacecraft engine.

Figure 4.

Three-dimensional printed components made from titanium alloys: (a) turbine blade guider, and (b) active cooling section from an aircraft and spacecraft engine [67].

4.3. Medical and Healthcare Sector

KSA considers the health of all Saudis to be of utmost importance. Government spending on medication accounts for 44% of the total healthcare budget. The size of the pharmaceutical market in 2016 was SAR 28 billion, with the current market having increased to SAR 40 billion with a compound growth rate of 5.4% [68]. To curtail pharmaceutical expenditure, the government is initiating several measures, one of which is to localize drug manufacturing and development. According to the Saudi Pharmaceutical Industries and Medical Appliances Corporation (SPIMCO) (Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), more than 40 organizations actively manufacture drugs in Saudi Arabia [69]. The manufactured drugs market is worth SAR 34 billion, caters to local needs to the extent of 36%, and contributes SAR 1.5 billion to exports. Many global manufacturers, such as GSK, Pfizer, and Sanofi Aventis, are looking to manufacture products in Saudi Arabia.

The traditional manufacturing techniques employed in the mass production of pharmaceuticals has several limitations, such as the high capital investment needed for machinery, the large space requirements, and the difficulty involved in varying dosages to meet the specific needs of patients. To overcome these limitations and to improve efficacy, AM techniques have been gaining popularity in the production of precise drug delivery systems. In the dental field, AM is being used successfully in dental models, drill guides, etc. The applications of AM technology in medical and healthcare product manufacturing are given in Table 5.

Table 5.

AM technologies used in manufacturing medical and healthcare products.

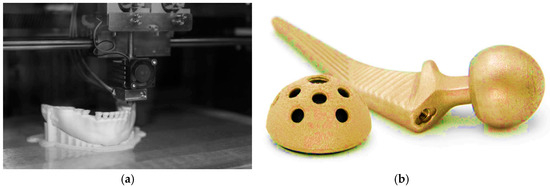

Thanks to 3D printing technology, there has been a significant improvement in the healthcare products that can be produced, such as tailor-made orthopedic implants. This degree of individualization minimizes the need for withdrawal operations or revision surgery and enhances the quality of care. Compared to conventional techniques, additive manufacturing increases the speed of production, reduces expenses, and increases the scope within which a design can be produced, making it more efficient in producing intricate parts, such as implants and surgical instruments. Developments in 3D printing will be a major factor contributing to personalized medicine while changing the face of the healthcare sector. Figure 5 illustrates two types of 3D printing applications in the field of medicine. In the left image (a), a 3D printer enables dental implants to be customized for a patient’s mouth. In the right image (b), a 3D-printed hip ball and socket joint made of titanium are shown, illustrating the advanced material and custom manufacturing approach in orthopedics [74].

Figure 5.

Three-dimensional printing in healthcare: (a) custom dental implants for personalized patient care, and (b) 3D-printed titanium hip ball and socket [74].

5. Limitations of AM Technologies

AM technologies are a cost-effective solution in the manufacture of components in the automotive sector and other automotive design applications. However, a major limitation is that, compared to existing manufacturing technologies, it takes a long time to establish the process for a specific component. Generally, SMEs are experts at producing one specific product and supply them to different customers with varied specifications; thus, customized products are manufactured in small batches and then the production switches over to other designs. The frequent changeover from one batch to another requires the adoption of manufacturing flexibility, which requires an expert workforce. In a study of the manufacture of aeronautical equipment and heavy machinery [75], it was revealed that, on one hand, the overall manufacturing costs were reduced considerably, and on the other hand, the costs associated with the technology, machinery, and post-processing functions increased drastically.

Due to accelerated progress in the evolution of AM technologies, particularly in manufacturing aerospace and defense equipment, SMEs need to upgrade their process and product technologies on a regular basis. As AM technology and machinery manufacturers are transnational corporations, SMEs are required to obtain the information related to technical feasibilities, customization, materials, and sources of information from equipment suppliers and manufacturers [76]. Shifting from existing methods to new technology involves the development of customized, tailor-made manufacturing principles and guidelines, and each technology is associated with software modifications and different design tools. To implement this, a skilled workforce is required and continuous training is needed to maintain skills.

For drug manufacturing, in the context of dosage, studies [77] have highlighted a number of drawbacks. In addition to the need for a skilled and knowledgeable workforce, another major hurdle is the high initial investment necessary for the procurement of machinery and equipment. From an economic perspective, huge investments may not be viable for SMEs unless the AM technologies are to be kept in the long term. Similarly, in the case of manufacturing bones, organs, tissues, etc., using multi-material printing, AM technologies may produce items with variations in strength when compared to existing manufacturing processes [78]. To overcome these hurdles, sound knowledge of the application of materials and their standards is essential.

6. Recommendations

In order to overcome the limitations of additive manufacturing and to enable SMEs to implement AM effectively, the author interacted with executives from two manufacturing SMEs, one located in Sudair Industrial City and the other in Dammam Industrial Center. These two SMEs are in the process of implementing AM as their product manufacturing technology. The discussions with the executives took place individually and jointly over several rounds. Based on these discussions, the author proposes three main recommendations from the SME perspective, as presented below.

6.1. Financial Assistance

Additive manufacturing technologies are completely different from conventional manufacturing processes. The technologies are automated and based on the use of computerized design software and control systems. To predict the processes, simulation software is necessary and may require modifications; therefore, this manufacturing technology is initially expensive and requires the continuous updating of software and designs. As the majority of SMEs are financially constrained, support from financial institutions is necessary, particularly for technology-dependent SMEs, in terms of cheaper finance options. Moreover, there is a need to intensify small industrial banks to provide policies for financing SMEs. Governments should also play a vital role in encouraging the shift from traditional manufacturing to AM by offering incentives such as tax breaks or straightforward, unconditional grants that could support SMEs in adopting AM technology.

6.2. Industry Interaction and Training Centers

The literature reveals that the key to implementing AM technologies is a skilled workforce. The skills of the workforce must be continually updated through basic education, experience, and training programs. Continuous workforce training is important if the changing requirements of customers are to be met. SMEs feel that the cost involved in the continuous training of their personnel is expensive and can be unaffordable; thus, state-of-the-art training centers should be established to train the SME workforce.

6.3. Inter-Firm Linkages Between SMEs and LEs

To ensure product quality, the continuous monitoring of the manufacturing process should be carried out by other agencies. In cases where SMEs act as suppliers to LEs, the linkages between them are limited to information sharing. LEs share information on product pricing and product delivery, but this should be extended to include entrepreneurial-related linkages such as personnel to monitor SMEs’ manufacturing processes and provide technical assistance and know-how. The government must encourage supplier–buyer connections and make them mandatory.

7. Conclusions

SMEs play a vital role in the manufacturing sector due to their diverse and specialized production. However, to keep pace with their competitors in the international market, SMEs need to modernize their technologies according to market demands. Here, additive manufacturing emerges are a new way to solve the problem by providing relatively inexpensive opportunities for upgrades.

With AM, SMEs can improve their production effectiveness, minimize material waste, become more environmentally friendly, and achieve more sustainable operations. AM adoption, however, is not without resource constraints, such as the lack of funds and skilled labor. All stakeholders, including the government, industrial proponents, and SMEs, need to work together to develop an infrastructure that enhances creativity and utilizes skill training to guarantee the future viability of the manufacturing industry.

This exploratory study of two industrial zones in Saudi Arabia shows that additive manufacturing has no real role in their facilities. Through communication with the executive directors of these facilities, it was found that the high cost of machines, a lack of trained workers, and low productivity are all obstacles that prevent SMEs from applying these advanced technologies in their industrial facilities. For the sake of sustainability, effective resource utilization, reducing material waste, and preserving the environment, the government must intervene to support small and medium enterprises to make this transformation and provide educational facilities to provide skilled workers that are trained in these technologies.

Funding

This research was funded by Majmaah University, grant number R-2025-1562.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank the Deanship of Scientific Research at Majmaah University, Saudi Arabia, for supporting this work under Project Number No. R-2025-1562.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Preez, W.B.; Beer, D.J. Implementing the South African Additive Manufacturing Technology Roadmap—The Role of an Additive Manufacturing Centre of Competence. S. Afr. J. Ind. Eng. 2015, 26, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotturu, C.V.V.; Mahanty, B. Subcontracting Dimensions in the Small and Medium Enterprises: Study of Auto Components’ Manufacturing Industry in India. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part B J. Eng. Manuf. 2015, 230, 364–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzogbewu, T.C.; Fianko, S.K.; Amoah, N.; Afrifa Jnr, S.; de Beer, D. Additive Manufacturing in South Africa: Critical Success Factors. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bour, K.; Asafo, A. Study on the Effects of Sustainability Practices on the Growth of Manufacturing Companies in Urban Ghana. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pleticha, P. Who Benefits from Global Value Chain Participation? Does Functional Specialization Matter? Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2021, 58, 291–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreras-Méndez, J.L.; Llopis, O.; Alegre, J. Speeding up New Product Development through Entrepreneurial Orientation in SMEs: The Moderating Role of Ambidexterity. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2022, 102, 240–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R.G.; Kleinschmidt, E.J. An Investigation into the New Product Process: Steps, Deficiencies, and Impact. J. Prod. Innov. Manag. 1986, 3, 71–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotturu, C.M.V.V.; Mahanty, B. Determinants of SME Integration into Global Value Chains: Evidence from Indian Automotive Component Manufacturing Industry. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2017, 14, 313–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falahat, M.; Chong, S.C.; Liew, C. Navigating New Product Development: Uncovering Factors and Overcoming Challenges for Success. Heliyon 2024, 10, e23763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanguineti, F.; Magnani, G.; Zucchella, A. Technology Adoption, Global Value Chains and Sustainability: The Case of Additive Manufacturing. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 408, 137095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watz, M.; Hallstedt, S.I. Towards Sustainable Product Development—Insights from Testing and Evaluating a Profile Model for Management of Sustainability Integration into Design Requirements. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 346, 131000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beaman, J.J.; Bourell, D.L.; Seepersad, C.C.; Kovar, D.J.J.O.M.S. Additive Manufacturing Review: Early Past to Current Practice. J. Manuf. Sci. Eng. 2020, 142, 110812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monshaat. The Small and Medium Enterprises General Authority. Available online: https://www.monshaat.gov.sa/en/node/5257 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- King Abdulla University of Science and Technology. KAUST SME Survey Report on SME Innovation Services; King Abdulla University of Science and Technology: Thuwal, Saudi Arabia, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Elhassan, O.M. Obstacles and Problems Facing the Financing of Small and Medium Enterprises in KSA. J. Financ. Account. 2019, 7, 168–183. [Google Scholar]

- EI-Tamimi, A.M. Evaluation of the Implementation of Business Practices and Advanced Manufacturing Technology (AMT) in Saudi Industry. J. King Saud Univ. Eng. Sci. 2010, 22, 139–152. [Google Scholar]

- Aloulou, W.J. Impacts of Strategic Orientations on New Product Development and Firm Performances: Insights from Saudi Industrial Firms. Eur. J. Innov. Manag. 2019, 22, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafiki, A. Determinants of SME Growth: An Empirical Study in Saudi Arabia. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2020, 28, 205–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Tit, A.; Omri, A.; Euchi, J. Critical Success Factors of Small and Medium-Sized Enterprises in Saudi Arabia: Insights from Sustainability Perspective. Adm. Sci. 2019, 9, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshumaimri, A.; Almohaimeed, A. The Reality of Funding Entrepreneurship Projects in Saudi Arabia the Perspective of Entrepreneurs. In Proceedings of the Saudi International Entrepreneurship Conference, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 9 September 2014; pp. 84–103. [Google Scholar]

- Migdadi, M. Knowledge Management Enablers and Outcomes in the Mall-and-Medium Sized Enterprises. Ind. Manag. Data Syst. 2009, 109, 840–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamberi Ahmad, S. Micro, Small and Medium-sized Enterprises Development in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: Problems and Constraints. World J. Entrep. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2012, 8, 217–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshagawi, M. Assessing Women Entrepreneurship in Saudi Arabia: Strategies for Success. Ajman J. Stud. Res. 2015, 14, 155–185. [Google Scholar]

- Altayyar, R.; Abdullah, A.R.; Rahman, A.A.; Ali, M.H.; Kazaure, M.A. Fostering SMEs Innovation Performance Development in Saudi Arabia Considering Vision 2030. J. Crit. Rev. 2020, 7, 347–356. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, A. Industrial Development in Saudi Arabia: Disparity in Growth and Development. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2020, 18, 23–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlBuhairan, B.; Foudeh, A. Modernizing Small & Medium-Sized Enterprises in Saudi Arabia. In Proceedings of the World Economic Forum, Davos, Switzerland, 16–20 January 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Colorado, H.A.; Velásquez, E.I.G.; Monteiro, S.N. Sustainability of Additive Manufacturing: The Circular Economy of Materials and Environmental Perspectives. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 8221–8234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, T.; Kellens, K.; Tang, R.; Chen, C.; Chen, G. Sustainability of Additive Manufacturing: An Overview on Its Energy Demand and Environmental Impact. Addit. Manuf. 2018, 21, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, A.; Zhang, Y.; Ren, S.; Lv, J.; Peng, T.; Waqar, S.; Yin, E. A Big Data-Driven Framework for Sustainable and Smart Additive Manufacturing. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2021, 67, 102026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegab, H.; Khanna, N.; Monib, N.; Salem, A. Design for Sustainable Additive Manufacturing: A Review. Sustain. Mater. Technol. 2023, 35, e00576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecheter, A.; Tarlochan, F.; Kucukvar, M. A Review of Conventional versus Additive Manufacturing for Metals: Life-Cycle Environmental and Economic Analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gopal, M.; Lemu, H.G.; Gutema, E.M. Sustainable Additive Manufacturing and Environmental Implications: Literature Review. Sustainability 2022, 15, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, I.; Matos, F.; Jacinto, C.; Salman, H.; Cardeal, G.; Carvalho, H.; Godina, R.; Peças, P. Framework for Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of Additive Manufacturing. Sustainability 2020, 12, 929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wohlers, T.; Gornet, T.; Mostow, N.; Campbell, I.; Diegel, O.; Kowen, J.; Huff, R.; Stucker, B.; Fidan, I.; Doukas, A.; et al. History of Additive Manufacturing. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4474824 (accessed on 10 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- International Development Corporation (IDC). IDC Market Insights. 2020. Available online: https://blogs.idc.com/2024/05/13/marketing-stop-creating-so-much-content/ (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Feygin, M.; Hsieh, B. Laminated Object Manufacturing (LOM): A Simpler Process; The University of Texas at Austin: Austin, TX, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobs, P.F.; Reid, D.T. Rapid Prototyping & Manufacturing: Fundamentals of Stereolithography; Society of Manufacturing Engineers: Southfield, MI, USA, 1992; p. 434. [Google Scholar]

- Beaman, J.; Barlow, J.; Bourell, D.; Crawford, R. Solid Freeform Fabrication: A New Direction in Manufacturing; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Norwell, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Balla, V.K.; Bose, S.; Bandyopadhyay, A. Processing of Bulk Alumina Ceramics Using Laser Engineered Net Shaping. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 2008, 5, 234–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pique, A.; Chrisey, D. Direct-Write Technologies for Rapid Prototyping Applications: Sensors, Electronics, and Integrated Power Sources. 2002. Available online: https://shop.elsevier.com/books/direct-write-technologies-for-rapid-prototyping-applications/pique/978-0-12-174231-7 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Hussam, H.; Abdelrhman, Y.; Soliman, M.E.S.; Hassab-Allah, I.M. Effects of a New Filling Technique on the Mechanical Properties of ABS Specimens Manufactured by Fused Deposition Modeling. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2022, 121, 1639–1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmat, M.; Maher, I.; Abdelrhman, Y. Surface Roughness Prediction of Polylactic Acid (PLA) Products Manufactured by 3D Printing and Post Processed Using a Slurry Impact Technique: ANFIS-Based Modeling. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 8, 87–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heshmat, M.; Abdelrhman, Y. Improving Surface Roughness of Polylactic Acid (PLA) Products Manufactured by 3D Printing Using a Novel Slurry Impact Technique. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2021, 27, 1791–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldahash, S.A.; Abdelaal, O.; Abdelrhman, Y. Slurry Erosion–Corrosion Characteristics of As-Built Ti-6Al-4V Manufactured by Selective Laser Melting. Materials 2020, 13, 3967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunovjanek, M.; Knofius, N.; Reiner, G. Additive Manufacturing and Supply Chains—A Systematic Review. Prod. Plan. Control 2022, 33, 1231–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tziantopoulos, K.; Tsolakis, N.; Vlachos, D.; Tsironis, L. Supply Chain Reconfiguration Opportunities Arising from Additive Manufacturing Technologies in the Digital Era. Prod. Plan. Control 2019, 30, 510–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, M.; Saporiti, N.; Shoeibi, M.; Holmström, J.; Salmi, M. Additive Manufacturing in the Medical Sector: From an Empirical Investigation of Challenges and Opportunities toward the Design of an Ecosystem Model. Int. J. Oper. Prod. Manag. 2024, 45, 387–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, M.; Coruzzolo, A.M.; Basten, R.; Knofius, N.; Lolli, F.; Sgarbossa, F. Choosing between Additive and Conventional Manufacturing of Spare Parts: On the Impact of Failure Rate Uncertainties and the Tools to Reduce Them. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2024, 278, 109438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghimire, T.; Joshi, A.; Sen, S.; Kapruan, C.; Chadha, U.; Selvaraj, S.K. Blockchain in Additive Manufacturing Processes: Recent Trends & Its Future Possibilities. Mater. Today Proc. 2022, 50, 2170–2180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Equbal, M.A.; Equbal, A.; Khan, Z.A.; Badruddin, I.A. Machine Learning in Additive Manufacturing: A Comprehensive Insight. Int. J. Lightweight Mater. Manuf. 2024; in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peron, M. A Digital Twin-Enabled Digital Spare Parts Supply Chain. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2024. Available online: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00207543.2024.2338878 (accessed on 10 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- Diegel, O. Additive Manufacturing: The New Industrial Revolution. 2011. Available online: https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/9314623 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Rouf, S.; Malik, A.; Singh, N.; Raina, A.; Naveed, N.; Siddiqui, M.I.H.; Haq, M.I.U. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: Industrial and Medical Applications. Sustain. Oper. Comput. 2022, 3, 258–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockin, A. and T.A.M. Environmental Assessment of Additive Manufacturing in the Automotive Industry. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 226, 977–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Industry and Mineral Resources. Available online: https://mim.gov.sa/en/ (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Gray, J.; Depcik, C.; Sietins, J.M.; Kudzal, A.; Rogers, R.; Cho, K. Production of the Cylinder Head and Crankcase of a Small Internal Combustion Engine Using Metal Laser Powder Bed Fusion. J. Manuf. Process. 2023, 97, 100–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alami, A.H.; Ghani Olabi, A.; Alashkar, A.; Alasad, S.; Aljaghoub, H.; Rezk, H.; Abdelkareem, M.A. Additive Manufacturing in the Aerospace and Automotive Industries: Recent Trends and Role in Achieving Sustainable Development Goals. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2023, 14, 102516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cotteleer, M.; Holdowsky, J.; Mahto, M. The 3D Opportunity Primer; Deloitte University Press: Westlake, TX, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Giffi, C.A.; Gangula, B.; Illinda, P. 3D Opportunity in the Automotive Industry: Additive Manufacturing Hits the Road. 2014. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/insights/us/articles/additive-manufacturing-3d-opportunity-in-automotive/DUP_707-3D-Opportunity-Auto-Industry_MASTER.pdf (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- A Comprehensive Review of Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing): Processes, Applications and Future Potential (Journal Article)|NSF PAGES. Available online: https://par.nsf.gov/biblio/10124832 (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- 3DGence Verification of the Prototype: Fire Engine’s Manifold 3D Printout—Automotive Case Study. Available online: https://3dgence.com/case-studies/fire-engines-manifold-3d-printout/ (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- PIF|Giga-Projects|Public Investment Fund. Available online: https://www.pif.gov.sa/en/our-investments/giga-projects/?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiA9vS6BhA9EiwAJpnXw7hIbOqpgKNUwel4Xt97nLKye8flA6sCTtqrQxaGpaGfGjqtf_NzexoCBScQAvD_BwE (accessed on 14 December 2024).

- Colorado, H.A.; Cardenas, C.A.; Gutierrez-Velazquez, E.I.; Escobedo, J.P.; Monteiro, S.N. Additive Manufacturing in Armor and Military Applications: Research, Materials, Processing Technologies, Perspectives, and Challenges. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2023, 27, 3900–3913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Makky, M.Y.; Mahmoud, D. The Importance of Additive Manufacturing Processes in Industrial Applications. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Applied Mechanics and and Mechanical Engineering, Cairo, Egypt, 19–21 April 2016; pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, D.; Yang, J.; Lin, K.; Ma, C.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, H.; Guo, M.; Zhang, H. Compression Performance and Mechanism of Superimposed Sine-Wave Structures Fabricated by Selective Laser Melting. Mater. Des. 2021, 198, 109291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, J.C.; Boyer, R.R. Opportunities and Issues in the Application of Titanium Alloys for Aerospace Components. Metals 2020, 10, 705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innovative Applications of Metal 3D Printing in Aerospace Using Titanium Alloy—Eplus3D. Available online: https://www.eplus3d.com/innovative-applications-of-metal-3d-printing-in-aerospace-using-titanium-alloy.html (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Alshehri, S.; Alshammari, R.; Alyamani, M.; Dabbagh, R.; Almalki, B.; Aldosari, O.; Alsowayigh, R.; Alkudeer, A.; Aldosari, F.; Sabr, J.; et al. Current and Future Prospective of Pharmaceutical Manufacturing in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2023, 31, 605–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tawfik, E.A.; Tawfik, A.F.; Alajmi, A.M.; Badr, M.Y.; Al-jedai, A.; Almozain, N.H.; Bukhary, H.A.; Halwani, A.A.; Al Awadh, S.A.; Alshamsan, A.; et al. Localizing Pharmaceuticals Manufacturing and Its Impact on Drug Security in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm. J. 2022, 30, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmi, M. Possibilities of Preoperative Medical Models Made by 3D Printing or Additive Manufacturing. J. Med. Eng. 2016, 2016, 6191526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Xu, S.; Zhou, S.; Xu, W.; Leary, M.; Choong, P.; Qian, M.; Brandt, M.; Xie, Y.M. Topological Design and Additive Manufacturing of Porous Metals for Bone Scaffolds and Orthopaedic Implants: A Review. Biomaterials 2016, 83, 127–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Culmone, C.; Smit, G.; Breedveld, P. Additive Manufacturing of Medical Instruments: A State-of-the-Art Review. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 27, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, M.; Bas, O.; Castro, N.J.; Schmutz, B.; Hutmacher, D.W. Additive Biomanufacturing of Scaffolds for Breast Reconstruction. Addit. Manuf. 2019, 30, 100845. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 3D Printing in Healthcare Makes It Personal|Jabil. Available online: https://www.jabil.com/blog/3d-printing-in-healthcare.html (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Gonçalves, A.; Ferreira, B.; Leite, M.; Ribeiro, I. Environmental and Economic Sustainability Impacts of Metal Additive Manufacturing: A Study in the Industrial Machinery and Aeronautical Sectors. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2023, 42, 292–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alifui-Segbaya, F.; Ituarte, I.F.; Hasanov, S.; Gupta, A.; Fidan, I. Opportunities and Limitations of Additive Manufacturing. In Springer Handbook of Additive Manufacturing; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 125–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varghese, R.; Salvi, S.; Sood, P.; Karsiya, J.; Kumar, D. Recent Advancements in Additive Manufacturing Techniques Employed in the Pharmaceutical Industry: A Bird’s Eye View. Ann. 3D Print. Med. 2022, 8, 100081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adugna, Y.W.; Akessa, A.D.; Lemu, H.G. Overview Study on Challenges of Additive Manufacturing for a Healthcare Application. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2021, 1201, 012041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).