Abstract

The environmental protection tax (EPT) is a vital means for China to promote sustainable development. However, its impact on corporate green innovation is controversial. Utilizing the data from Chinese A-share industrial listed companies from 2013 to 2022 and the difference-in-differences (DID) model, this study examines the impact of the EPT on corporate green innovation. The results indicate that the EPT can promote corporate green innovation, which is robust across various tests. Furthermore, the EPT fosters corporate green innovation mainly by stimulating companies to increase research and development (R&D) investment. The heterogeneity analysis demonstrates that the EPT promotes green innovation only in large-scale companies, non-state-owned companies, and eastern companies. The further analysis suggests that the green innovation brought by the EPT could improve corporate economic performance. Moreover, the EPT promotes both corporate substantive innovation and strategic innovation. That is, the EPT could enhance the quality of green innovation whilst also inducing strategic behavior. This study could provide profound insights to facilitate green transitions in emerging market countries like China.

1. Introduction

How to realize the synergy between ecological environment protection and economic growth is a practical challenge faced by numerous countries. Over the past decades, China has achieved breakthroughs in its economy, becoming the largest manufacturing country worldwide. However, this achievement is accompanied by increasingly severe environmental pollution, which has become a constraint on China’s sustainable growth [1]. To control environmental pollution and achieve sustainable development, China began implementing the pollution discharge fee in 1979. Unfortunately, because of excessive administrative intervention, insufficient enforcement rigidity, and weak enforcement, the effectiveness of the pollution discharge fee was limited [2]. Thus, the Chinese government began reforming the pollution discharge fee into the environmental protection tax (EPT), and formally implemented the EPT in 2018. During this reform, some regions have raised the EPT tax rates to be higher than the previous pollution discharge fee, while others have maintained the levy standards of the pollution discharge fee. This variation provides a quasi-natural experiment for examining the EPT’s impact.

Since its implementation in 2018, the impact of the EPT has received increasing attention. Some of the literature has studied the EPT’s environmental impact from the perspective of pollutant emissions [2,3] and air quality [4]. Most conclude that the EPT could effectively promote environmental protection [2,3,4]. Some studies have examined the economic effect of the EPT from the perspective of corporate financial performance [5,6] and total factor productivity [7,8], but no consistent view has been reached. There are also studies on the impact of the EPT on corporate green innovation. For example, Wang et al. (2023) [9] hold the view that the EPT could enhance corporate pollution emissions costs, squeeze corporate research and development (R&D) investment, and thereby negatively affect corporate green innovation. Conversely, Liu and Xiao (2022) [10] argued that the EPT has increased pressure on firms to reduce emissions, thereby motivating them to innovate. Therefore, there is no consensus on the impact of the EPT on corporate green innovation, and it needs further empirical research. In fact, as environmental regulations become increasingly stringent, the proportion of environmental costs in corporate expenditure continues to rise. Addressing pollution at its source through green innovation has been a more effective approach to tackling environmental pollution issues [11]. Studying the effect of the EPT on corporate green innovation holds significant practical meaning.

To fill this gap, we systematically examine the EPT’s effect on corporate green innovation. Specifically, by leveraging the enforcement of the EPT as a quasi-natural experiment, we employ a difference-in-differences (DID) model and utilize data from Chinese A-share industrial listed companies to analyze. Building on this, we analyze the mechanism through which the EPT fosters corporate green innovation. Furthermore, we explore the heterogeneous influence of the EPT on corporate green innovation across enterprises with different characteristics. Finally, we analyze the influence of green innovation brought by the EPT on corporate economic performance and the EPT’s impact on corporate green innovation quality.

The marginal contributions of this study are as follows. Firstly, this study constructs a logical chain of analysis linking the EPT, green innovation, and corporate economic performance. Different from the existing literature that only explores the EPT’s influence on corporate green innovation, this study further analyzes the influence of green innovation on corporate economic performance. This could not only effectively fill the gap in the existing literature concerning the impact of green innovation induced by the EPT on corporate economic performance, but also provide empirical evidence for the existence of the innovation compensation effect. Secondly, building upon the analysis of the EPT’s effect on the quantity of corporate green innovation, this study further investigates the EPT’s effect on the quality of corporate green innovation. Given that some firms conduct green innovation activities not for technological breakthroughs but to increase innovation quantity or seek other benefits, this study categorizes green innovation based on firms’ innovation motivations and further explores the EPT’s impact on the quality of corporate green innovation. This attempt could enrich existing research concerning the EPT’s influence on corporate green innovation.

The structure of this study is as follows. Section 2 outlines the background of the EPT and proposes the research hypothesis. Section 3 details the empirical design, including the model, variables, and data. Section 4 presents the empirical analysis, including baseline regression results, robustness checks, mechanism analysis, and heterogeneity analysis. Section 5 summarizes the research conclusion, offers policy recommendations, and identifies the limitations of this study.

2. Background and Research Hypothesis

2.1. The Background of the EPT

The EPT in China evolved from the pollution discharge fee. To stimulate enterprises to strengthen environmental governance and control pollutant emissions, China started enforcing the pollution discharge fee in 1979. However, the pollution discharge fee was ineffective due to low levy standards, excessive administrative intervention, and insufficient enforcement rigidity [2]. Consequently, the Chinese government reformed the pollution discharge fee into the EPT and formally implemented it in 2018.

To avoid excessive impact on the economy, the reform follows the principle of “shifting tax burden”. This means that taxable pollutants, taxpayers, and the calculation method are the same for the EPT and the pollution discharge fee. Specifically, the taxable pollutants for both the EPT and the pollution discharge fee encompass air pollutants, water pollutants, noise, and solid waste. The taxpayers are both producers who directly emit taxable pollutants into the environment. In addition, the calculation methods are both based on the amount of taxable pollutants emitted and the corresponding charging standards.

Notably, to address the limitations of the pollution discharge fee, some improvements have also been made to the EPT. First of all, the legal status is elevated. Unlike the pollution discharge fee that was implemented according to administrative regulations, the EPT is levied according to China’s tax law. Evading or omitting EPT tax payments will result in severe penalties, which will effectively reduce corporate tax evasion and omission behavior. Secondly, the tax collection entity is changed. The pollution discharge fee is levied by the Chinese environmental protection department, while the EPT is levied by the Chinese tax department. The tax department is independent and could effectively avoid the government’s administrative intervention. Thirdly, the levy standards are adjusted. The levy standards of the pollution discharge fee for water pollutants and air pollutants are 1.4 yuan and 1.2 yuan per pollution equivalent, respectively. Comparatively, the tax rates of the EPT for water pollutants and air pollutants are 1.4–14 yuan and 1.2–12 yuan per pollution equivalent, respectively. The governments can independently determine the locally applicable EPT rate within this scope. Some of them have raised the tax rates of the EPT to be higher than the levy standards of the pollution discharge fee, and others have maintained the levy standards of the pollution discharge fee, which offers a quasi-natural experiment for exploring the influence of the EPT on corporate green innovation.

2.2. Research Hypotheses

2.2.1. The EPT and Corporate Green Innovation

The influence of environmental regulation on corporate green innovation has been widely debated by scholars. Following the neoclassical economic theory, environmental regulation would increase corporate pollution emissions cost [12], squeeze corporate funds for technological innovation, and thus negatively influence corporate green innovation. However, this viewpoint is criticized by numerous scholars, who hold that the above analysis is based on a static analysis framework and ignores the possibility of innovation [10]. Following Porter’s hypothesis, proper environmental regulation could lead to business innovation and improve their competitiveness [13]. As a newly implemented environmental regulation in China, the EPT may promote corporate green innovation.

First of all, the EPT’s implementation has brought external pressure on firms to innovate. Compared to the levy standards of the pollution discharge fee, some regions have increased the EPT tax rates, which would directly enhance the cost of environmental compliance for firms and intensify the pressure on them to control pollution emissions [14]. Based on the theory of firm competitiveness, external pressure could stimulate firms to overcome organizational inertia and stimulate their innovation vitality [10]. Secondly, the enforcement of the EPT may reduce the uncertainty associated with environmental investments. As the first independent tax dedicated to ecological protection in China, the EPT’s implementation demonstrates the government’s strong determination to promote green development. This could help firms realize that environmental protection is not a temporary slogan, but will influence their interests in the long term. Compared with other emission reduction measures, although green innovation is marked by large investments and high risk, it could help enterprises reduce pollution emissions fundamentally [15]. Therefore, to ensure the maximization of long-term benefits, companies have incentives to conduct green innovation activities. Following the above analysis, this study proposes the first hypothesis as follows:

H1.

The EPT could promote corporate green innovation.

2.2.2. The Mechanism of the EPT on Corporate Green Innovation

In the knowledge production function, R&D investment is treated as a capital resource input and is a key factor in fostering innovation [16]. However, innovation is often characterized by long cycles, high risk, and large investments. Meanwhile, the benefits of innovation have externalities, which makes the endogenous motivation for enterprises to innovate insufficient and the actual level of corporate R&D investment lower than the optimal level [17,18]. Therefore, it is necessary to use external driving forces such as preferential policies, R&D subsidies, and environmental regulation to encourage firms to increase R&D investment. As a newly implemented environmental regulation, the EPT may motivate firms to enhance R&D investment and alleviate market failures in innovation.

Firstly, unlike the pollution discharge fee, the EPT is mandatory and legally rigid. Enterprises need to pay the EPT strictly in accordance with the quantity of pollutants discharged and the levy standards of the EPT. This means that the larger the amount of pollutant emissions, the more the EPT they need to pay. Under this mechanism, enterprises have the motivation to enhance R&D investment to reduce pollutant emissions. Secondly, the EPT is China’s first independent tax specifically designed for ecological conservation. The EPT’s implementation has demonstrated the government’s commitment to protecting the environment. This could make firms realize that pollution emissions will have a long-term impact on their interests, and R&D investment is valuable [5]. Furthermore, compared to measures such as adjusting the production scale, responding to the EPT by increasing R&D investment has less negative influence on corporate short-term profits [19,20].

According to the above analysis, this study posits that the EPT could encourage companies to enhance their R&D investment, thereby promoting corporate green innovation. R&D investment is a mechanism through which the EPT promotes corporate green innovation. Therefore, this study proposes the second hypothesis as follows:

H2.

The EPT promotes corporate green innovation by stimulating companies to enhance R&D investment.

3. Empirical Design

3.1. Model

This study employs a DID model to explore the EPT’s influence on corporate green innovation. The DID model is a widely utilized model to evaluate policy effects in existing economic research [21,22]. Its fundamental logic is to treat the implementation of a new policy as a natural experiment. By comparing the differences in changes between the experimental and control groups before and after policy implementation, it effectively mitigates endogeneity issues arising from unobservable factors that do not change over time, thereby identifying the causal impact of policy implementation [23,24]. As the implementation of the EPT could be regarded as a quasi-natural experiment [5,25], the DID model is suitable for evaluating its effect. Specifically, some provinces have enhanced the “tax burden”, with the tax rates of the EPT higher than the levy standards of the pollution discharge fee, making companies there more influenced by the EPT. Conversely, the other provinces have kept the “tax burden” unchanged, with the tax rates of the EPT consistent with the levy standards of the pollution discharge fee, making companies there virtually unaffected by the EPT. Thus, in line with Long et al. (2022) [5] and Lu and Yang (2024) [25], this study considers the enforcement of the EPT as a quasi-natural experiment. Companies located in provinces with an enhanced “tax burden” are the experimental group, while those located in provinces with an unchanged “tax burden” are the control group. Accordingly, we construct the following DID model.

where t and i stand for the year and the firm, respectively. represents green innovation of company i in year t. and stand for the time dummy variable and the group dummy variable, respectively. is the key independent variable, and its coefficient is of most interest to us. If is significantly positive, it suggests that the EPT can foster corporate green innovation, and H1 is verified. is a series of variables that potentially influence corporate green innovation. is the random error term. and are employed to control for the year fixed effect and the firm fixed effect, respectively.

3.2. Variables

Corporate green innovation (GrnInv) is the dependent variable. Patent is a widely used indicator for measuring corporate innovation output [26]. Considering that some patent applications fail due to not satisfying novelty or other requirements, employing patent grant data rather than patent application data may make the measurement more accurate [27]. Hence, following Zheng and Zhang (2023) [28], this study takes the logarithm of the number of green patent grants plus 1 to proxy for corporate green innovation.

Treat × Time is the independent variable. Treat is the group dummy variable, and Time is the year dummy variable. Treat equals 0 if enterprises locate in provinces with unchanged “tax burden” and 1 if enterprises locate in provinces with raised “tax burden”. Time equals 0 for years before the EPT policy (before 2018) and 1 for years after the EPT policy (after 2018). Treat × Time is employed to estimate the EPT’s influence on corporate green innovation.

Following Long et al. (2022) [5] and Wang et al. (2025) [29], several factors that potentially affect corporate green innovation are also controlled in the model: (i) Asset size (LnSize), measured by the logarithm of corporate total assets. Typically, larger companies usually possess more resources available for green innovation activities and are more innovative [30]. (ii) Leverage (Lev), measured by the proportion of a company’s total liabilities to total assets. Companies with high leverage may avoid risks and are more cautious in innovative activities [31]. (iii) Firm value (TobinQ), measured by the rate of a company’s market value to total assets. A higher TobinQ value suggests a stronger ability to create value and a greater sense of innovation [32]. (iv) Return on assets (Roa), defined as the proportion of a company’s net profit to its total assets. Companies with higher profit margins usually have more retained earnings to conduct green innovation activities, and Roa may positively influence corporate green innovation [33]. Nevertheless, green innovation activities usually are large investments and high risk, and firms with a high Roa may also be more cautious and unwilling to innovate [34]. (v) Capital expenditures (Capi), measured by the rate of cash used to purchase and construct fixed assets, intangible assets, and other long-term assets to corporate total assets. Companies with higher capital expenditures usually have better production and technological conditions and higher innovation initiatives. However, higher capital expenditures may extend the lifespan of current technologies, leading to lower demand for new technologies and innovation initiatives [35]. (vi) Capital intensity (Inten), defined as the ratio of a company’s total assets to operating income. It reflects corporate dependence on capital investment and business risk, affecting corporate green innovation [36]. (vii) Cash holdings (Cash), expressed as the rate of a company’s monetary funds to its total assets. Green innovation often requires significant financial investment, and firms with adequate cash flow could provide financial security for the smooth promotion of green innovation activities [37]. (viii) Firm age (Age), defined as the logarithm of the number of years the company has been in existence. Institutional inertia, which could obstruct innovation, increases with time [38]. Younger firms are usually more motivated to undertake green innovation activities [39]. (ix) CEO duality (Dual), measured by a dummy variable. When a company’s manager and its chairman of the board are the same person, Dual equals 1; otherwise, Dual equals 0. Following the principal-agent theory, the integration of these two positions could reduce the disagreement in decision-making and enhance the efficiency of innovation activities [28].

3.3. Data

We take Chinese A-share industrial listed companies from 2013 to 2022 as the sample. The reasons are as follows. Firstly, the DID model demands a consistent sample period before and after the policy. Due to the EPT policy starting in 2018, and the enterprise data we obtain being up to 2022, the sample period is set as 2013–2022. Secondly, the EPT is levied based on the EPT rate and the amount of pollutants emitted. Industrial companies are the main taxpayers due to their high emission intensity. Therefore, following Li et al. (2024) [40], this study utilizes industrial companies as the sample.

The data is obtained from two widely used databases. In particular, corporate green patent data comes from the Chinese Research Data Services (CNRDS) Platform, which provides a detailed record of the quantity of patents authorized and applied by listed enterprises since 1990 [36,41]. Other company data is collected from the China Stock Market and Accounting Research (CSMAR) database [42]. To ensure the quality of the data, we process the data as follows. First of all, the samples labeled ST or *ST are excluded because these firms have two or more consecutive years of losses or other infractions. Secondly, we drop the samples with severe missing data. Thirdly, we drop the samples with abnormal financial data, such as a gearing ratio greater than 1 or less than 0. Fourth, to assess the policy effects of the EPT, we need to compute the differences in corporate green innovation before and after the EPT’s enforcement. Therefore, firms listed after 2018 are dropped. Fifth, to relieve the potential effect of extreme values, we winsorize the continuous variables at the 1% level. Finally, we obtain a panel data set consisting of 20,065 firm-year observations from 2536 firms. Table 1 gives the descriptive statistics of the variables.

Table 1.

Descriptive statistics.

4. Empirical Analysis

4.1. Baseline Regression

Table 2 demonstrates the result of the EPT’s impact on corporate green innovation. Concretely, Column (1) is the result that only controls for the firm fixed effect and year fixed effect, while Column (2) is the result that further incorporates control variables. It can be found that the estimated coefficients of Treat × Time in those two columns are significantly positive, revealing that the enforcement of the EPT can foster corporate green innovation. Further, the coefficient of Treat × Time in Column (2) is 0.038, meaning that the enforcement of the EPT enhances green innovation by 3.8% for firms in areas with a raised “tax burden” compared to those in areas with an unchanged “tax burden”.

Table 2.

The result of the baseline regression.

Possible reasons are as follows. After the enforcement of the EPT, some areas have raised the “tax burden”, and the collection of the EPT is stricter. This would inevitably increase some firms’ compliance costs and exert external pressure on firms to control pollution emissions. External pressure could encourage firms to overcome organizational inertia and incentivize corporate innovation vitality [10]. Additionally, as the first independent tax specifically designed for ecological conservation in China, the enforcement of the EPT suggests the government’s strong commitment to protecting the environment and signals that environmental protection would influence corporate interests in the long term [5]. This would stimulate enterprises to innovate to maintain long-term competitive advantages.

The result for control variables is in line with theoretical expectations and existing research [36,43]. Specifically, the coefficient of enterprise size (LnSize) is significant and 0.068, suggesting that an increment in enterprise size could foster corporate green innovation. The coefficient of firm value (TobinQ) is also significant and greater than 0, suggesting that the bigger market value the company creates, the stronger its innovation consciousness. The coefficient of return on assets (Roa) is significantly negative, verifying that companies with higher profit margins are reluctant to invest more in green innovation projects. The coefficient of capital expenditure (Capi) is significantly positive, indicating that companies with high capital expenditure also have a higher initiative in green innovation.

4.2. Robustness Checks

4.2.1. Parallel Trend Test

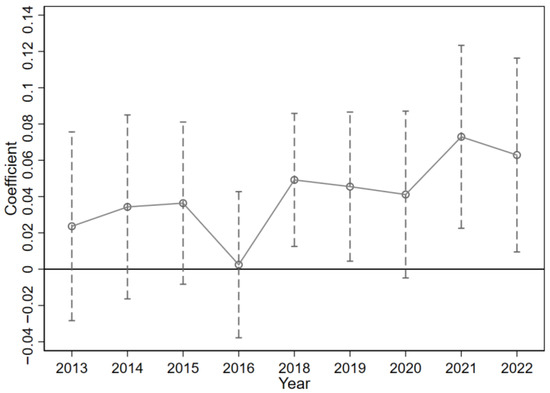

The baseline regression has identified the causal effect of the EPT on corporate green innovation by utilizing the DID model. However, causal identification utilizing the DID model presupposes that the control and experimental groups meet the parallel trend assumption. In our study, this assumption signifies that before the EPT is introduced, the trend of green innovation in the control and experimental groups should be consistent. Otherwise, the baseline regression result is unreliable. To assure the reliability of the findings, our study follows Beck et al. (2010) [44] and utilizes the event study approach to test the parallel trend. Concretely, we construct the following model.

where Year(t = k) is a dummy variable for year k. When t = k, Year(t = k) equals 1; otherwise, Year(t = k) equals 0. To prevent multi-collinearity, we treat k = 2017 as the baseline. {} is the key coefficient, representing the difference in green innovation between the control and experimental groups. When k < 2018, if is not significantly different from 0, it means Equation (1) satisfies the parallel trend assumption. Otherwise, it violates the parallel trend assumption. The meanings of other symbols are in line with Equation (1).

Figure 1 reports the regression result of at a 95% confidence interval. It demonstrates that before the EPT is enforced, the 95% confidence interval contains 0, and does not exert a significant difference from 0. This result indicates that before the enforcement of the EPT, the trends of corporate green innovation between the control and experimental groups did not have a significant difference. Therefore, Equation (1) passes the parallel trend test. Furthermore, after the EPT is enforced, is significantly greater than 0 and shows an upward trend. This implies that the EPT positively influences corporate green innovation and thereby verifies the reliability of the baseline regression result.

Figure 1.

Parallel trend test. Note: Hollow circles demonstrate point estimates of coefficients for each period, and vertical dashed lines demonstrate the lower and upper limits of the 95% confidence interval.

4.2.2. Placebo Test

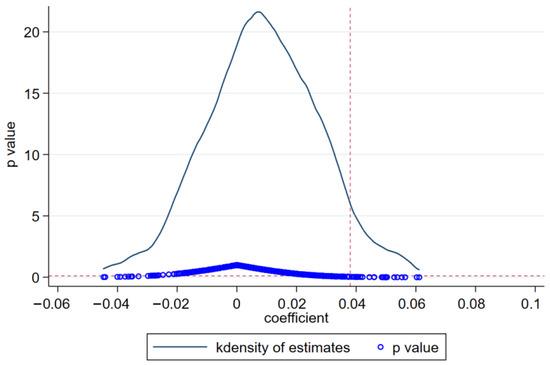

To alleviate the impact of random factors or omitted variables, this study references Tang et al. (2024) [45] and performs two placebo tests as follows.

Firstly, randomly select the experimental group. Specifically, we randomly screen 1331 companies from the sample as a false-experimental group, while the other companies are designated as a false-control group. Then, regress Equation (1). Repeat these two steps 500 times. Finally, we could obtain 500 estimated coefficients and associated p-values for Treat × Time. Theoretically, since we cannot guarantee that all the randomly chosen companies are situated in areas with increased “tax burden”, the estimated coefficients for Treat × Time should be insignificant. Otherwise, the baseline regression result is biased. Figure 2 illustrates the kernel density distribution of the coefficients for False_Treat × Time along with their corresponding p-values. It reveals that the coefficients of False_Treat × Time are distributed near zero, and p-values are mostly over 0.1, which is insignificant. Meanwhile, compared to the coefficients of False_Treat × Time, the true coefficient of Treat × Time (0.038) is an outlier. Thus, the baseline regression result is unlikely to be disturbed by random factors or omitted variables, which verifies the robustness.

Figure 2.

Placebo test: randomly choosing the experimental group. Note: The red vertical and red horizontal lines represent the true coefficient of Treat × Time (0.038) and the 10% significance level, respectively.

Secondly, fabricate the enforcement time of the EPT. Specifically, we keep the sample period from 2013 to 2017, which is unaffected by the EPT. Then, take 2015 and 2016 as the hypothetical enforcement years for the EPT, respectively. Next, regress Equation (1). The results for advancing the enforcement of the EPT to 2015 and 2016 are demonstrated in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 3, respectively. It reveals that regardless of whether the enforcement of the EPT is advanced by 2 years or 3 years, both coefficients of Treat × Time are insignificant, suggesting that the enhancement in corporate green innovation is indeed caused by the implementation of the EPT and that our finding is robust.

Table 3.

Placebo test: fabricating the enforcement time of the EPT.

4.2.3. Changing the Measurement of Corporate Green Innovation

To ensure the robustness of our findings, we alter the measurement of corporate green innovation. Specifically, following Yu et al. (2025) [46], we employ PGrnInv (the proportion of green patents granted by a company to its total patents granted) to proxy for corporate green innovation. This measurement could eliminate the influence of unobservable factors such as patent technology subsidies. The result is demonstrated in Columns (1) and (2) of Table 4. The coefficients of Treat × Time are significantly positive whether control variables are incorporated into the model or not. This result suggests that our finding is not significantly influenced by the measurement of corporate green innovation, thereby verifying its robustness.

Table 4.

The result of robustness checks.

4.2.4. Excluding Environmental Policy Interference

Other environmental policies enforced by the government during the sample period may also influence corporate green innovation. For example, the low-carbon city pilot policy (LCCP) has been enforced in several cities in China since 2010. Empirical studies have shown that the LCCP could foster corporate green innovation by enhancing corporate R&D investment [47]. In addition, China has introduced the carbon emissions trading policy (CET) in some regions, such as Beijing and Tianjin, since 2013. It is proposed that the CET can influence pollution emissions [48] and corporate green innovation [49].

To exclude the effects of the aforementioned policies, we refer to Guo and Xu (2024) [50], incorporating relevant dummy variables into Equation (1). Specifically, is used to account for the impact of the CET. If city i carries out the CET in year t, equals 1; otherwise, equals 0. The meaning of is analogous. The result is presented in Columns (3)–(5) of Table 4. It demonstrates that the coefficients of Treat × Time are significantly positive, whether and are introduced into Equation (1) separately, or they are introduced into Equation (1) simultaneously. This suggests that environmental policies implemented during the sample period do not significantly affect our findings and also confirms the robustness of our findings.

4.2.5. Testing for Endogeneity

To ensure the reliability of the result, we also need to mitigate the potential endogeneity issues that usually arise from reverse causality and sample selection bias. Since the explanatory variable (the EPT policy) is unlikely to be affected by the explained variable (corporate green innovation), this significantly alleviates the endogeneity issue associated with reverse causality. In terms of the endogeneity issue that may arise from sample selection bias, we test it by using the instrumental variable (IV) method. Given that the area of green land could somewhat represent the government’s emphasis on environmental protection, the more emphasis the governments attach to environmental protection, the more likely they are to raise the EPT tax rate. Meanwhile, the area of green land is planned by the government and will not directly influence firms’ green innovation. This signifies that the area of green land meets the requirements of the IV, which is associated with the endogenous variable but not directly linked to the dependent variable. Therefore, following Cao and Su (2023) [51], we use the area of green land (GA, the logarithm of the area of green land) as the IV for the EPT and regress with the two-stage least squares method. Specifically, Treat × Time (the endogenous variable) is first regressed against GA (the instrumental variable) and the control variables in Equation (1) to obtain the fitted values of Treat × Time. Then, replace the core explanatory variable in Equation (1) with the fitted values of Treat × Time and re-regress Equation (1).

The result is demonstrated in Columns (6)–(7) of Table 4. Specifically, the coefficient of GA in Column (6) is significant and 0.063, suggesting that GA is a proper instrumental variable. Meanwhile, the coefficient of Treat × Time in Column (7) is significant and 0.218, meaning that the baseline regression result will not be remarkably influenced by the endogeneity issues, thereby verifying the robustness of our finding.

4.3. Mechanism Analysis

The baseline regression result suggests that the EPT could stimulate corporate green innovation. In this part, we try to conduct a mechanism analysis, empirically testing whether the EPT enhances corporate green innovation by stimulating companies to increase R&D investment. Drawing on Tao et al. (2024) [52], we develop the following model to analyze.

where is corporate R&D investment and is the mechanism variable. Following Liu et al. (2023) [53], R&D investment is measured by the number of R&D staff as a proportion of the corporate total number of employees. Equation (3) is employed to verify the influence of the EPT on corporate R&D investment, and Equation (4) is employed to verify the influence of corporate R&D investment on corporate green innovation. The meanings of other symbols are in line with Equation (1). The data for the mechanism variable come from the CSMER database.

The regression result is demonstrated in Table 5. The coefficient of Treat × Time in Column (1) is significantly positive, meaning that the EPT can encourage enterprises to enhance R&D investment. Furthermore, the coefficient of RD in Column (2) is significant and 0.295, meaning that increasing R&D investment can foster corporate green innovation. Therefore, the EPT can stimulate enterprises to enhance R&D investment, thereby fostering corporate green innovation. R&D investment is the mechanism through which the EPT promotes corporate green innovation. Therefore, H2 is verified.

Table 5.

The result of the mechanism analysis.

4.4. Heterogeneity Analysis

4.4.1. Heterogeneity of Enterprise Ownership

Firms with different kinds of ownership would have different resources, business objectives, and institutional constraints, which may make firms respond differently to the same macro policies. To test whether the influence of the EPT on corporate green innovation varies across enterprise ownership, this study categorizes the sample into state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and non-state-owned enterprises (non-SOEs) according to enterprise ownership. Then, we use these two sub-samples to regress Equation (1) separately. Columns (1)–(2) of Table 6 demonstrate the result. It can be found that the coefficient of Treat × Time in Column (1) is positive and insignificant, and that Column (2) is positive and significant. This differing result suggests that the EPT has a heterogeneous influence on corporate green innovation across enterprise ownership, and it significantly promotes green innovation only in non-SOEs.

Table 6.

The result of the heterogeneity analysis.

There are two possible reasons for the heterogeneous results. Firstly, SOEs are established by the government, enjoying preferential policies and political advantages such as tax reductions and fiscal subsidies. Therefore, when faced with the environmental compliance pressure caused by the EPT, SOEs have a weaker initiative in taking measures to actively respond. In contrast, non-SOEs bear their profits and losses. They are less likely to enjoy the preferential policies or political advantages. For the non-SOEs, the appropriate approach to dealing with the EPT is to actively respond, such as conducting green innovation activities. Secondly, the R&D input of SOEs is relatively stable, meaning their levels of corporate green innovation will not change drastically due to the enforcement of environmental policies such as the EPT [54]. Hence, the EPT significantly promotes green innovation only in non-SOEs.

4.4.2. Heterogeneity of Enterprise Scale

Enterprises with different scales typically have differences in innovation capabilities, competitive advantages, and development modes. These differences may make enterprises respond differently to the EPT. To test whether the influence of the EPT on corporate green innovation varies across enterprise sizes, we categorize the sample into large-scale enterprises and small-scale enterprises based on the median of corporate total assets. Then, we employ these two sub-samples to regress Equation (1) separately. The regression result is demonstrated in Columns (3)–(4) of Table 6. It indicates that the coefficient for Treat × Time in Column (3) is significant and 0.050, while the coefficient in Column (4) is insignificant. The differing result means that the EPT has a heterogeneous effect on green innovation across enterprise scales, and it only contributes to green innovation in large-scale enterprises.

The potential reasons for the heterogeneous result may be as follows. Firstly, corporate innovation decisions depend on corporate innovation capabilities and the availability of innovative resources [55]. Large-scale enterprises usually possess abundant financial and human resources, making them better equipped to engage in technological innovation activities [56]. Comparatively, many small-scale enterprises have weaker innovation and financing capabilities and are subject to more constraints in increasing R&D investments [57]. Secondly, green innovation is usually marked by long cycles, high risk, and large investments. Small-scale enterprises tend to have a weaker ability to resist risk. Unequal risk tolerances may make the EPT exert a limited influence on green innovation in small-scale enterprises.

4.4.3. Heterogeneity of Enterprise Location

There is a huge difference in economic development and innovation capacity between China’s eastern region and its central and western regions, which may make enterprises in distinct regions respond differently to the EPT. To examine whether the influence of the EPT on corporate green innovation varies across enterprise location, we categorize enterprises into eastern enterprises and central-western enterprises according to enterprise location. Then, we regress Equation (1) with these two sub-samples. The regression results are presented in Columns (5)–(6) of Table 6. It could be found that the coefficient of Treat × Time in Column (5) is significantly positive, whereas that in Column (6) is not significant. This indicates that the implementation of the EPT could significantly promote eastern enterprises’ green innovation, but has no significant effect on central-western enterprises’ green innovation.

This may be because the Chinese eastern region is more economically developed, enabling enterprises to more easily access R&D funding, high-end talent, and advanced equipment, thereby allowing them to respond efficiently to the EPT and engage in green innovation activities. Comparatively, the central and western regions lag in economic development, and the foundational resources for green innovation, such as capital and talent, are relatively insufficient [58,59]. This may constrain corporate green innovation activities to some extent.

4.5. Further Analysis

4.5.1. The Economic Consequence of Green Innovation

The aforementioned result demonstrates that implementing the EPT can effectively foster corporate green innovation. However, the impact of green innovation induced by the EPT on corporate economic consequences remains unclear. Based on Porter’s hypothesis, moderate environmental regulation could motivate enterprises to innovate, partially or fully compensating for the costs caused by environmental regulation [19]. Meanwhile, green innovation could help enterprises optimize production technologies or processes, reduce resource consumption, and thus accumulate circulation capital [60]. From this perspective, the green innovation brought by the EPT may improve corporate economic performance. However, some studies argue that green innovation squeezes corporate resources that could have been used for other investment projects, prolongs the investment return cycle, and suppresses corporate economic performance [61]. Therefore, building upon the analysis above, we further examine the impact of green innovation induced by the EPT on corporate economic consequences. This could not only extend the existing research chain linking the EPT and corporate green innovation but also offer insights into balancing environmental protection and economic growth. Specifically, we follow Hwang and Kim (2009) [62] and construct the following model to examine

where presents the economic performance of enterprise i in year t, including TFP (corporate total factor productivity) and Revenue (operating income). Following Luo et al. (2024) [63], TFP is measured by the non-radial SBM-ML index, with the number of employees, corporate net fixed assets, and the amount of electricity consumption as input factors, corporate operating income as the expected output, and the amount of dust and smoke emissions, industrial sulfur dioxide, and wastewater emissions as unexpected output. Revenue is defined as the logarithm of corporate operating income. is the coefficient of Treat × Time in Equation (1). is the core independent variable in Equation (5), representing the green innovation caused by the EPT. is the coefficient we are concerned about. The definitions of other symbols are in line with Equation (1).

As shown in Columns (1)–(2) of Table 7, regardless of whether TFP or Revenue is utilized as the dependent variable in Equation (5), the coefficient of is always bigger than 0 and significant. These results suggest that the green innovation induced by the EPT could enhance corporate total factor productivity and corporate operating income. In other words, the green innovation driven by the EPT could improve actual corporate economic performance. This finding provides new empirical evidence for Porter’s hypothesis from China.

Table 7.

The result of further analysis.

4.5.2. The Quality of Green Innovation

In the aforementioned analysis, we measured corporate green innovation by the number of green patent grants. The enhancement in corporate green innovation only means an increase in the quantity of green patent grants, not a substantive improvement in green technology. Because some enterprises engage in innovation not to create differentiated products or improve production processes, but rather as a strategic tactic—pursuing innovation quantity [64]. To further examine the EPT’s impact on corporate green innovation quality, we divide green innovation into substantive innovation and strategic innovation according to innovation motivation. Substantive innovation is aimed at advancing technological capabilities and pursuing innovation quality, while strategic innovation is driven by motives to pursue other benefits and innovation quantity [65]. Meanwhile, green patents are categorized into green invention patents and utility model patents. Green invention patents are characterized by greater complexity and higher technological sophistication, and are treated as high-quality innovation. Comparatively, utility model patents involve lower complexity and technological standards, and are regarded as low-level innovations designed to satisfy policy requirements [66]. Hence, following Jiang and Bai (2022) [67] and Liu et al. (2024) [68], we use the logarithm of the number of green invention patents granted plus one to measure corporate substantive innovation (GreIP) and the logarithm of the number of green utility model patents granted plus one to measure corporate strategic innovation (GreUP). Then, we re-regress Equation (1) with GreIP and GreUP as the dependent variables, respectively.

The regression results are shown in Columns (3)–(4) of Table 7. It could be found that the regression coefficients of Treat × Time in these two columns are both significantly positive, indicating that the implementation of the EPT could significantly promote corporate substantive innovation and strategic innovation. In other words, the EPT could enhance the quality of green innovation whilst also inducing strategic behavior. Possible reasons are as follows. The EPT is the first independent tax dedicated to ecological protection in China, and its collection and administration are stringent. Confronted with the pollution emission cost pressures induced by the EPT, to reduce pollution emissions at source and safeguard long-term interests, enterprises have an incentive to conduct substantive innovation activities. However, to comply with government regulations in the short term, the pollution emission cost pressure may also drive enterprises to conduct strategic innovation activities with lower complexity. Hence, the EPT could simultaneously promote both corporate strategic innovation and substantive innovation. The implementation of the EPT could increase the quantity of corporate green innovation and also enhance the quality of corporate green innovation.

5. Conclusions and Policy Implications

5.1. Conclusions

The EPT is a crucial way for China to promote sustainable development. This study treats the enforcement of the EPT as a quasi-natural experiment and investigates the influence of the EPT on corporate green innovation. Utilizing the DID model and the data from Chinese A-share industrial listed companies, we find that the EPT can effectively promote corporate green innovation. Furthermore, the EPT fosters corporate green innovation mainly through increasing corporate R&D investment. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the EPT fosters green innovation only in large-scale companies, non-SOEs, and eastern companies. The further analysis suggests that the green innovation brought by the EPT could improve corporate economic performance. Moreover, the EPT promotes both corporate green substantive innovation and green strategic innovation. That is, the EPT could enhance the quality of green innovation whilst also inducing strategic behavior.

5.2. Policy Implications

This study bears important policy implications. Firstly, local government should fully leverage the role of the EPT in encouraging corporate green innovation. Currently, China’s industrial structure remains dominated by high-polluting industries, and the energy structure is dominated by coal, still facing a severe situation of pollution emissions and ecological damage. Green innovation is vital in addressing this dilemma. Based on our findings, the EPT is an effective tool to promote corporate green innovation. Its essential role should be fully utilized. Secondly, the government should take measures to encourage enterprises to increase their R&D investment, which is a key factor in fostering innovation. For instance, a higher proportion of pre-tax additional deductions should be permitted for corporate R&D investment. Additional R&D subsidies should be granted to enterprises that establish dedicated green R&D departments or collaborate with research institutions on green R&D projects. Thirdly, support and guidance for small-scale enterprises and SOEs should be strengthened. As for the shortcomings in green innovation resources and capabilities among small-scale enterprises, the government may establish specialized green innovation loans for small-scale enterprises, providing low-interest, long-term financial support to address their R&D funding shortages. For SOEs, the government could incorporate green innovation achievements into corporate performance assessment systems so as to encourage greater investment in green innovation and leverage their strengths in green technology research. Fourthly, the government should further strengthen its guidance on corporate substantive innovation, for instance, by establishing specialized green innovation loans, offering preferential lending terms for breakthrough innovations, incorporating substantive innovation achievements into green procurement lists, and prioritizing their procurement in government projects.

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

This study still has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. Firstly, this study takes the listed enterprises as the sample, which are only a few large enterprises, and cannot fully reveal the current situation of Chinese enterprises. Thus, future research could explore the EPT’s effect on corporate green innovation using more inclusive firm data. Secondly, this study only explores the effect of the EPT on green innovation within individual enterprises. Theoretically, because of the spatial spillover of technology and the imitation among companies, the EPT may also have a supply chain spillover effect, a spatial spillover effect, or an industry spillover effect on corporate green innovation. Nevertheless, owing to data limitations and the focus of this study, we do not empirically explore these spillover effects. Future research could further investigate the existence of these spillover effects and their potential transmission mechanisms.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Q.Y.; methodology, Q.Y.; software, Q.Y.; formal analysis, Q.Y. and B.Y.; data curation, B.Y. and C.M.; writing—original draft preparation, Q.Y.; writing—review and editing, B.Y., C.M., W.X. and Z.L.; visualization, Q.Y.; supervision, Z.L.; project administration, Z.L.; funding acquisition, Z.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (BH202534).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yuan, B.; Yin, Q. Does green foreign investment contribute to air pollution abatement? Evidence from China. J. Int. Dev. 2024, 36, 912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Lin, Z.; Du, H.; Feng, T.; Zuo, J. Do environmental taxes reduce air pollution? Evidence from fossil-fuel power plants in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 295, 113112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Lin, Y.; Yuan, B.; Dong, Z. Does the environmental protection tax reduce environmental pollution? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 106198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, F.; Li, J. Assessing impacts and determinants of China’s environmental protection tax on improving air quality at provincial level based on Bayesian statistics. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 271, 111017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, F.; Lin, F.; Ge, C. Impact of China’s environmental protection tax on corporate performance: Empirical data from heavily polluting industries. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2022, 97, 106892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, S.; Wang, L. The impact of environmental protection tax on corporate performance: A new insight from multi angles analysis. Heliyon 2024, 10, e30127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Zeng, Q.; Wang, Y. The impact of environmental protection tax on green total factor productivity: China’s exceptional approach. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2024, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, B.; Xu, K. The impact of environmental protection tax reform on low-carbon total factor productivity: Evidence from China’s fee-to-tax reform. Energy 2024, 290, 130216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Xu, S.; Meng, X. Environmental protection tax and green innovation. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 56670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Xiao, Y. China’s environmental protection tax and green innovation: Incentive effect or crowding-out effect? Econ. Res. J. 2022, 57, 72. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Acemoglu, D.; Akcigit, U.; Hanley, D.; Kerr, W. Transition to clean technology. J. Political Econ. 2016, 124, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kemp, R.; Pontoglio, S. The innovation effects of environmental policy instruments—A typical case of the blind men and the elephant? Ecol. Econ. 2011, 72, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M.E.; Van Der Linde, C. Toward a new conception of the environment-competitiveness relationship. J. Econ. Perspect. 1995, 9, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Q.; Meng, C.; Dong, Z.; Li, B. The effect of the environmental protection tax on corporate labor demand: Evidence from China. Econ. Anal. Pol. 2025, 86, 713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Zhou, Z.; Chen, Y. Can big data alleviate the principal-agent problems in environmental governance? Chin. J. Popul. Resour. 2025, 35, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, X.; Liu, Z.; Han, Z. How can carbon trading promote the green innovation efficiency of manufacturing enterprises? Energy Strategy Rev. 2024, 53, 101420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrow, K.J. Economic Welfare and the Allocation of Resources for Invention; Macmillan Education UK: London, UK, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, C.I.; Williams, J.C. Measuring the social return to R&D. Q. J. Econ. 1998, 113, 1119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffe, A.B.; Palmer, K. Environmental regulation and innovation: A panel data study. Rev. Econ. Stat. 1997, 79, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popp, D. International innovation and diffusion of air pollution control technologies: The effects of NOX and SO2 regulation in the US, Japan, and Germany. J. Environ. Manag. 2006, 51, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albright, B.; Nasioudis, D.; Craig, S.; Moss, H.; Latif, N.; Ko, E.; Haggerty, A. Impact of medicaid expansion on women with gynecologic cancer: A difference-in-difference analysis. Amer. J. Obs. Gyn. 2021, 224, e1–e195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delaruelle, K.; van de Werfhorst, H.; Bracke, P. Do comprehensive school reforms impact the health of early school leavers? Results of a comparative difference-in-difference design. Soc. Sci. Med. 2019, 239, 112542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Xia, C.; Fang, K.; Zhang, W. Effect of the carbon emissions trading policy on the co-benefits of carbon emissions reduction and air pollution control. Energy Policy 2022, 165, 112998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, Z.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, J. Do ship emission control areas in China reduce sulfur dioxide concentrations in local air? A study on causal effect using the difference-in-difference model. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 149, 110506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, S.; Yang, Q. Price of going green: The employment effects of the environmental protection tax in China. China Econ. Rev. 2024, 87, 102244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grafström, J. International knowledge spillovers in the wind power industry: Evidence from the European Union. Econ. Innov. New Tech. 2018, 27, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steensma, H.K.; Chari, M.; Heidl, R. A comparative analysis of patent assertion entities in markets for intellectual property rights. Organ. Sci. 2016, 27, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.; Zhang, Q. Digital transformation, corporate social responsibility and green technology innovation-based on empirical evidence of listed companies in China. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 424, 138805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Yu, X.; Zhang, Y. The effects of outward foreign direct investment on green technological innovation: A quasi-natural experiment based on Chinese enterprises. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2025, 110, 107666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkin, T.; Gilinsky, A., Jr.; Newton, S.K. Environmental strategy: Does it lead to competitive advantage in the US wine industry? Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2012, 24, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Huang, J.; Chen, J. Does digital finance matter for corporate green investment? Evidence from heavily polluting industries in China. Energy Econ. 2023, 117, 106476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, A.; Si, L.; Hu, S. Can the penalty mechanism of mandatory environmental regulations promote green innovation? Evidence from China’s enterprise data. Energy Econ. 2023, 125, 106856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, G.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y. Can the green credit policy stimulate green innovation in heavily polluting enterprises? Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment in China. Energy Econ. 2021, 98, 105134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Xing, C. How does China’s green credit policy affect the green innovation of high polluting enterprises? The perspective of radical and incremental innovations. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 336, 130387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Z.; Huang, W. Influence of non-R&D innovation expenditure on innovation performance of high technology industries. Sci. Res. Manag. 2015, 36, 1. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Xi, B.; Jia, W. Research on the impact of carbon trading on enterprises’ green technology innovation. Energy Policy 2025, 197, 114436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Wan, D.; Sun, C.; Wu, K.; Lin, C. Does political inspection promote corporate green innovation? Energy Econ. 2023, 123, 106730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, J.; Yam, R.C. Effects of government financial incentives on firms’ innovation performance in China: Evidences from Beijing in the 1990s. Res. Policy 2015, 44, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czarnitzki, D.; Kraft, K. An empirical test of the asymmetric models on innovative activity: Who invests more into R&D, the incumbent or the challenger? J. Econ. Behav. Organ. 2004, 54, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Teng, Y.; Zhou, Y.; Feng, X. Can environmental protection tax force enterprises to improve green technology innovation? Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2024, 31, 9371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, F.; Yan, Y.; Hao, J.; Wu, J. Retail investor attention and corporate green innovation: Evidence from China. Energy Econ. 2022, 115, 106308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, F.; Jiang, P.; Elamer, A.A.; Owusu, A. Environmental performance and corporate innovation in China: The moderating impact of firm ownership. Technol. Forecast. Soc. 2022, 184, 121990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, M.; Li, M.; Liao, Z. Do politically connected CEOs promote Chinese listed industrial firms’ green innovation? The mediating role of external governance environments. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 278, 123634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, T.; Levine, R.; Levkov, A. Big bad banks? The winners and losers from bank deregulation in the United States. J. Financ. 2010, 65, 1637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Tong, M.; Chen, Y. Green investor behavior and corporate green innovation: Evidence from Chinese listed companies. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 366, 121691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Cheng, X.; Sun, Q. Does a not-for-profit minority institutional shareholder promote corporate green innovation? A quasi-natural experiment. J. Environ. Manag. 2025, 373, 123852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.; Wang, Y.; Jing, L. Low-carbon city pilot, external governance, and green innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 67, 105768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Fan, Y.; Zhu, L.; Bi, Q. How will the emissions trading scheme save cost for achieving China’s 2020 carbon intensity reduction target? Appl. Energy 2014, 136, 1043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, L.; Zhang, X.; Wang, X.; Chen, X.; Xu, X.; Song, M. Impact of carbon emission trading system on green technology innovation of energy enterprises in China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 360, 121229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Xu, J. Can urban digital intelligence transformation promote corporate green innovation? Evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 371, 123245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, X.; Su, X. Does the carbon emissions trading pilot policy promote carbon neutrality technology innovation? China Popul. Res. Environ. 2023, 33, 94–104. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tao, A.; Wang, C.; Zhang, S.; Kuai, P. Does enterprise digital transformation contribute to green innovation? Micro-level evidence from China. J. Environ. Manag. 2024, 370, 122609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Jia, M.; Zhang, Y.; Guo, X. The Regulation of Market-based Environmental and Corporate Green Innovation: Evidence from Carbon Emissions Trading pilots. J. Tech. Econ. 2023, 42, 53. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Qi, S.; Lin, S.; Cui, J. Do environmental rights trading schemes induce green innovation? Evidence from listed firms in China. Econ. Res. J. 2018, 53, 129. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Cuerva, M.C.; Triguero-Cano, Á.; Córcoles, D. Drivers of green and non-green innovation: Empirical evidence in Low-Tech SMEs. J. Clean. Prod. 2014, 68, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schumpeter, J.A. The Theory of Economic Development; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt-Dundas, N. Resource and capability constraints to innovation in small and large plants. Small Bus. Econ. 2006, 26, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Gan, L.; Huang, K.; Hu, S. The impact of low-carbon city pilot policy on corporate green innovation: Evidence from China. Financ. Res. Lett. 2023, 58, 104055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.; Wang, L. The impact of carbon emission trading schemes on corporate green innovation. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 514, 145792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, Y.; Wu, W. How does green innovation improve enterprises’ competitive advantage? The role of organizational learning. Sustain. Prod. Consump. 2021, 26, 504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petroni, G.; Bigliardi, B.; Galati, F. Rethinking the Porter hypothesis: The underappreciated importance of value appropriation and pollution intensity. Rev. Policy Res. 2019, 36, 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, B.H.; Kim, S. It pays to have friends. J. Financ. Econ. 2009, 93, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Liu, Y.; Wang, D.; Han, W. Low-carbon city pilot policy and enterprise low-carbon innovation–A quasi-natural experiment from China. Econ. Anal. Policy 2024, 83, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelm, K.; Narayanan, V.; Pinches, G. Shareholder value creation during R&D innovation and commercialization stages. Acad. Manag. J. 1995, 38, 770–786. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Z.; Luo, X.; Du, J.; Xu, B. Substantive or strategic: Government R&D subsidies and green innovation. Financ. Res. Lett. 2024, 67, 105796. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, M.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z. Substantive response or strategic response? The induced green innovation effects of carbon prices. Int. Rev. Financ. Anal. 2024, 93, 103139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Bai, Y. Strategic or substantive innovation?-The impact of institutional investors’ site visits on green innovation evidence from China. Technol. Soc. 2022, 68, 101904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Liu, L.; Feng, A. The impact of green innovation on corporate performance: An analysis based on substantive and strategic green innovations. Sustainability 2024, 16, 2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).