1. Introduction

Oil-exporting economies face persistent exposure to global energy price fluctuations, which often translate into macroeconomic instability and labour market disruptions. In the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries, heavy fiscal dependence on hydrocarbon revenues has intensified unemployment risks during oil price downturns. According to [

1], youth unemployment in the Middle East and North Africa region remains around 25%—the highest globally—while female labour-force participation averages only 16%, the lowest worldwide. Such indicators underscore the region’s vulnerability to oil-market cycles and the urgency of structural diversification and fiscal reform. These realities frame the core challenge motivating this study: identifying mechanisms that can cushion labour markets against commodity shocks while advancing long-term sustainability and inclusive growth.

The Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) provide a relevant framework in this context. While usually treated as long-term developmental targets, specific goals—such as SDG 7 (clean energy), SDG 8 (decent work), and SDG 9 (infrastructure)—are directly linked to economic resilience and structural transformation. By framing these goals as potential instruments of macroeconomic adjustment, it becomes possible to assess their role not only in advancing sustainability but also in mitigating cyclical vulnerabilities in rent-dependent economies. In oil-dependent labour markets, we treat SDGs as buffers: SDG 7 (clean energy) lowers exposure by diversifying the energy base, SDG 8 (decent work) dampens separations and raises job-finding through active labour-market programmes and social protection, and SDG 9 (infrastructure/innovation) increases absorptive capacity; this motivates our OilRent × SDG interaction tests.

Despite growing interest in SDG implementation, little empirical work has examined whether progress in these areas can moderate the labour market effects of oil rent dependence. Existing studies often rely on composite indices and overlook how disaggregated SDG domains may function as stabilizing policy tools in the face of external shocks.

This study addresses this gap by asking the following research question: Do targeted SDG reforms in clean energy (SDG 7), decent work (SDG 8), and infrastructure (SDG 9) moderate the impact of oil rent dependence on unemployment in GCC countries? To answer this question, we apply a comparative moderation framework to panel data from six GCC countries (2000–2021), estimating both baseline and interaction models using fixed effects and system GMM techniques. The main objective is to assess the stabilizing role of specific SDG reforms in labour markets affected by commodity shocks. This paper’s novelty is threefold. First, we integrate the SDG agenda with the resource-curse/oil-cycle literature by testing whether progress in SDGs 7 (clean energy), 8 (decent work), and 9 (infrastructure/innovation) moderates the oil-rent–unemployment link in the GCC. Second, we use disaggregated SDG scores—rather than a composite index—to identify which domain drives any buffer effect. Third, we cross-validate the moderation results across fixed-effects with Driscoll–Kraay inference, country-clustered OLS, and two-step System GMM to address heterogeneity and endogeneity.

In summary, our findings bridge sustainable-development objectives with macroeconomic stability in rentier states. The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 reviews relevant literature and develops the theoretical framework and hypotheses.

Section 3 presents the data and methodology.

Section 4 reports and analyses the empirical results.

Section 5 discusses policy implications, and

Section 6 concludes with limitations and directions for future research.

2. Theoretical Analysis and Hypothesis Development

Oil rents have long been associated with labour-market instability in rentier economies, especially those dependent on a single commodity. Classic resource curse theory suggests that reliance on external rents—like oil—leads to slower growth, weak private sectors, and high unemployment volatility [

2,

3,

4,

5]. Earlier studies by Refs. [

6,

7] also confirm that oil shocks amplify unemployment cycles in rentier states. Empirical evidence from the MENA region shows that oil-price shocks often increase unemployment rather than reduce it [

8,

9]. Within the GCC, these effects are intensified by dual labour markets and rigid institutions [

10,

11,

12]. This structural dependence on hydrocarbon rents produces procyclical employment patterns, where expansionary oil cycles raise public hiring while contractions lead to fiscal retrenchment and rising unemployment. Structural asymmetries further weaken the link between growth and employment. Ref. [

10] showed that unemployment in GCC economies does not move in tandem with output growth, while [

13] confirmed that the growth–unemployment relationship across Arab countries is often asymmetric, contradicting Okun’s Law. Labour markets remain segmented, with nationals typically in secure public-sector positions and expatriates concentrated in lower-paid private-sector roles [

12]. Even during expansionary phases, citizen unemployment remains persistently high [

14,

15], and oil booms fail to generate sustained employment gains [

16,

17]. Ref. [

18] also found that oil price volatility continues to affect long-run output and employment dynamics in Saudi Arabia. Despite reform programs such as Vision 2030, cyclical exposure persists [

19], suggesting that reducing oil dependence requires not only sectoral reallocation but also institutional transformation [

4,

20]. Within the GCC, evidence consistently links oil-cycle exposure to segmented labour markets and public-sector dependence, which weaken private-sector absorption during downturns. Foundational work documents structural strains in GCC labour markets and the limits of public hiring as a stabiliser [

4]. Unemployment does not track output one-for-one, reflecting institutional frictions and dualism [

10,

14,

15]. Panel evidence shows that oil rents and related shocks are associated with adverse employment dynamics in GCC economies, reinforcing the need for institutional buffers [

11,

16]. Taken together, this literature motivates our first hypothesis:

H1: Higher oil rents are associated with higher unemployment in GCC countries.

The Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) framework provides an alternative lens through which these vulnerabilities can be mitigated. Progress on SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure) may enhance economic resilience by diversifying energy sources, fostering inclusive labour markets, and strengthening industrial capacity [

21,

22,

23,

24]. Ref. [

25] emphasizes that innovation, governance, and infrastructure are central to breaking oil dependency in Gulf economies. while [

26] highlight the urgency of integrating SDG strategies into national development plans. Supporting evidence from the ref. [

27] underscores that sustained investment in infrastructure and human capital can strengthen adaptability to external shocks. In Saudi Arabia, the alignment between Vision 2030 and SDG reforms illustrates how energy transition and labour-market modernization reinforce one another [

28,

29]. Nonetheless, empirical assessments directly linking SDG progress to employment outcomes in rentier economies remain limited, leaving an open question about how these goals function as stabilizing mechanisms rather than distant development targets. We therefore focus on channels tied to SDG 7, SDG 8, and SDG 9.

SDG 7 (Clean Energy) represents a crucial diversification pathway that generates new employment opportunities while reducing macroeconomic exposure to oil volatility. Studies in Uzbekistan [

30] and the European Union [

31,

32] show that renewable-energy investment significantly lowers unemployment. However, green transitions can temporarily increase costs in energy-intensive sectors unless accompanied by retraining and wage-support policies [

33]. In the GCC, ref. [

24] demonstrate that renewable-energy expansion mitigates the labour-market impacts of oil shocks, while ref. [

34] finds that such investments reduce macroeconomic instability. Similarly, Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 advances renewable energy as a pillar of sustainable job creation, highlighting the role of SDG 7 in economic stabilization [

28,

29]. Overall, SDG 7 is expected to moderate unemployment responses to oil-cycle shocks.

SDG 8 (Decent Work) emphasizes inclusive growth, skills development, and social protection as mechanisms to improve labour-market adaptability. Persistent unemployment among youth and women across GCC countries reflects entrenched structural segmentation [

5,

14,

15]. Effective implementation of SDG 8 requires complementary investments in education and social safety nets to foster resilience during external shocks [

21,

22,

35], and MENA evidence linking human capital accumulation to stronger sustainability performance underscores the centrality of the skills dimension within SDG 8 [

36], though institutional weaknesses may constrain impact [

37]. Accordingly, SDG 8 should dampen the unemployment effect of oil-rent volatility.

SDG 9 (Infrastructure and Innovation) supports both short-term employment and long-term productivity by expanding industrial capacity and improving connectivity. Infrastructure investment has been shown to generate large-scale employment effects, as in the U.S. [

38] and emerging economies such as Indonesia, Mexico, and in Indonesia, Mexico, and Chile [

39]. In the GCC, infrastructure quality correlates strongly with innovation and industrial competitiveness [

40]. Country-specific evidence from Saudi Arabia and Kuwait suggests that infrastructure reforms under SDG 9 foster private-sector growth and labour reallocation [

35,

41]. Ref. [

23] further highlight how infrastructure investments promote regional diversification, while Ref. [

42] link access to finance and infrastructure to firm-level job creation. Ref. [

43] also notes that energy use in transport and industry shapes Saudi Arabia’s CO

2 trajectory, underscoring the environmental relevance of SDG-aligned industrial strategies. In sum, SDG 9 may enhance capacity for labour absorption, though short-run stabilization effects are less certain.

Recent research suggests that robust SDG performance reduces unemployment sensitivity to external shocks [

24]. Countries with higher SDG achievement experienced less labour-market disruption during the COVID-19 crisis [

21,

22]. However, effectiveness depends on institutional context [

37,

44]. Most prior studies evaluate SDGs through composite indices, which can obscure the distinct contributions of individual goals. Ref. [

45] demonstrate that energy-subsidy reforms make clean-energy policies fiscally sustainable, supporting the argument for disaggregated analysis.

Because SDG 8 aggregates employment, productivity, worker protection, and inclusion, we interpret the SDG 8 score as capturing an average moderation effect across these sub-domains. We retain the composite index to preserve country–year coverage in a small-N panel and to avoid multicollinearity and instrument proliferation that would arise from introducing multiple sub-indicators and interactions. Accordingly, the OilRent × SDG 8 coefficient is read as the mean stabilizing effect of SDG 8 rather than attribution to a single facet.

Existing work on oil shocks and unemployment in MENA/GCC documents procyclical labour outcomes but typically does not model sustainability reforms as moderators of the oil–employment link. Conversely, most SDG studies rely on composite indices and examine outcome levels (e.g., poverty, emissions) rather than cycle stabilisation or interaction effects with commodity dependence. We depart from both strands by (i) disaggregating SDGs 7, 8, and 9 to identify domain-specific buffering channels, and (ii) estimating explicit OilRent × SDG interactions under fixed effects with Driscoll–Kraay/clustered inference and two-step System GMM to address heterogeneity and endogeneity. This contrast motivates our empirical tests and clarifies the gap our study fills.

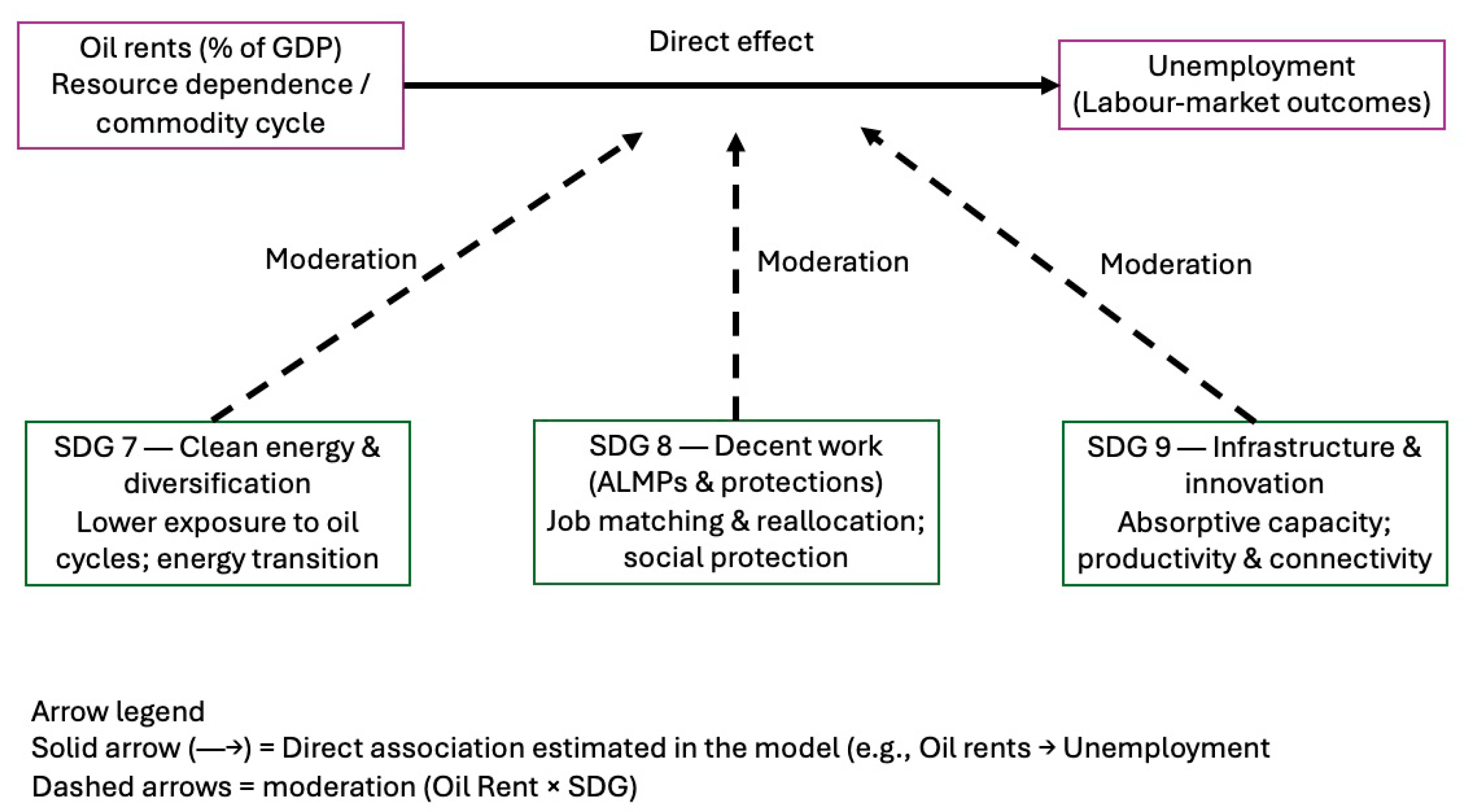

In oil-dependent labour markets, SDGs operate through three complementary channels: (i) institutional reforms (under SDG 8) that improve job matching, reduce segmentation, and strengthen labour standards and intermediation; (ii) diversification and innovation (under SDG 7 and SDG 9) that expand non-oil activity—via clean-energy deployment, industrial upgrading, and infrastructure—thereby lowering the economy’s exposure to oil-rent cycles; and (iii) social policies and active labour-market programmes (SDG 8) that support re-employment and household income during shocks through training, placement, and targeted wage support. These mechanisms imply that progress on SDGs should attenuate the sensitivity of unemployment to oil rents, which we test via OilRent × SDG interactions in our empirical models. These channels are operationalized in

Section 5.1 (Institutional Heterogeneity), which explains how country-specific reforms shape the transmission, and in

Section 5.2 (Fiscal Policy Implications), which outlines policy levers—energy-pricing reform, ALMPs, and SDG-consistent investment—that implement these buffers in practice.

Transmission mechanism (SDG 8 as a labour-market stabiliser). In rentier economies, oil-rent downturns reduce fiscal space and demand in non-tradables, raising separation rates and lowering job-finding probabilities. Progress on SDG 8 moderates this cyclicality along three margins. First, active labour-market programmes—job matching, training, apprenticeships, and wage subsidies—preserve existing matches and increase flows into employment, especially during downturns [

46,

47]. Second, social protection and basic labour standards act as automatic stabilisers, sustaining household demand and reducing lay-offs, which dampens the unemployment spike that follows oil-price contractions [

48,

49]. Third, institutional improvements—better intermediation and reduced segmentation—raise matching efficiency and facilitate reallocation across sectors [

12,

50]. Together, these channels dampen the unemployment response to oil-rent shocks.

Operationally, this implies that OilRent × SDG interactions should attenuate unemployment sensitivity; in particular, we expect a negative coefficient for OilRent × SDG 8 (labour-market stabilisation), with SDG 7 and SDG 9 effects shaped by transition speed and absorptive capacity.

Figure 1 summarises the study’s logic: oil-rent cycles affect unemployment directly, while three SDG channels moderate this link—(i) institutional buffering under SDG 8 (better matching, reduced segmentation, basic protections/intermediation), (ii) diversification and innovation under SDGs 7 and 9 (clean-energy deployment, infrastructure and industrial upgrading that expand non-oil activity), and (iii) social policies and ALMPs under SDG 8 (training, placement, targeted wage support) that sustain employment and incomes during downturns. These mechanisms imply that SDG progress should attenuate the sensitivity of unemployment to oil rents; accordingly, we test OilRent × SDG interactions in the empirical models. For identification clarity, we interpret the estimated interactions as conditional associations.

H2: Disaggregated progress in SDGs 7, 8, and 9 moderates the oil-rent–unemployment relationship more effectively than a composite SDG index.

3. Methodology

3.1. Data and Sample Selection

This study employs a panel dataset comprising six oil-exporting Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries—Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Oman, Bahrain, and Qatar—over the period 2000 to 2021. These countries represent a coherent regional bloc with similar macroeconomic exposure to oil rents and shared commitments to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Annual data were sourced from internationally recognized databases including the World Bank World Development Indicators (WDI), International Energy Agency (IEA), and the United Nations SDG indicators database. The SDG series (SDSN/SDR) provide backcasted values prior to 2015 based on harmonized sources and interpolation; accordingly, pre-2015 observations should be read as proxies for sustainability-related institutional trajectories rather than direct policy implementation [

51].

The selection of the 2000–2021 period reflects both the availability and consistency of data across GCC countries. Although extending the sample to 2023 or 2024 would include more recent developments, harmonized SDG indicators—particularly for Goals 7, 8, and 9—are not yet consistently available beyond 2021. The chosen endpoint also captures the COVID-19 pandemic and early recovery phase, providing sufficient variation to assess labor-market resilience during this period. Overall, the 2000–2021 window maximizes balanced, harmonized coverage for all six GCC countries while spanning major oil cycles (2008–2009, 2014–2016, 2020–2021). The SDG-related indicators used in this study—specifically for SDG 7 (Clean Energy), SDG 8 (Decent Work), and SDG 9 (Infrastructure)—were sourced from the Sustainable Development Report 2024 (Sachs, Lafortune, & Fuller, 2024) and its associated SDG Index & Dashboards database, developed by the Sustainable Development Solutions Network (SDSN) and Bertelsmann Stiftung [

52]. While the Sustainable Development Goals were formally adopted in 2015, the Sustainable Development Report 2024 provides backcasted estimates for earlier years. These backcasted values are constructed from UN and harmonized international sources and are extrapolated using time-consistent indicators [

51]. Accordingly, the pre-2015 data should be interpreted as proxies of sustainability-oriented institutional development rather than as direct measures of SDG implementation. Any cross-country differences may also reflect variation in data coverage and methodology.

This approach ensures a consistent, panel-compatible framework that captures long-run trajectories of sustainability reforms and labor market resilience in GCC economies.

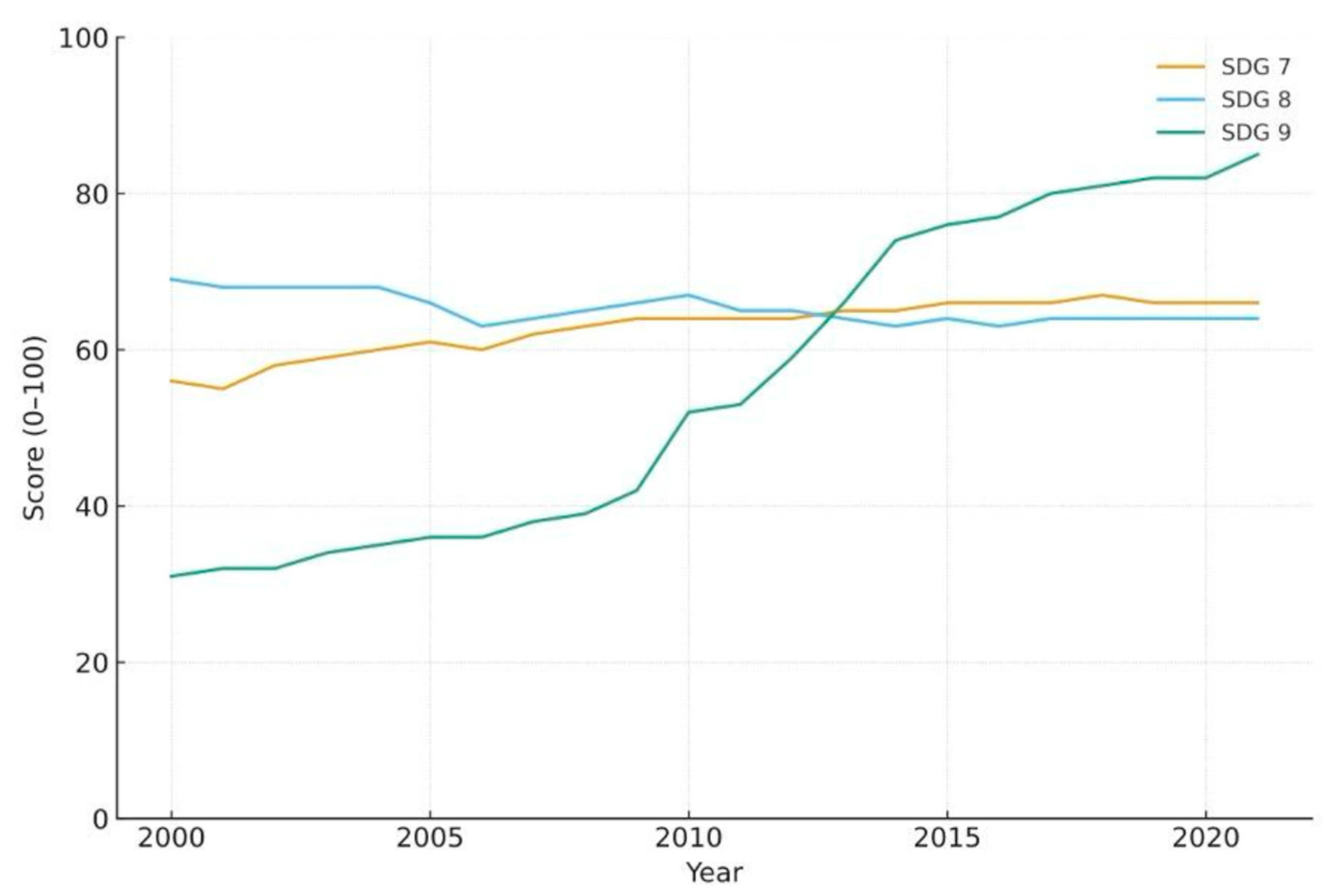

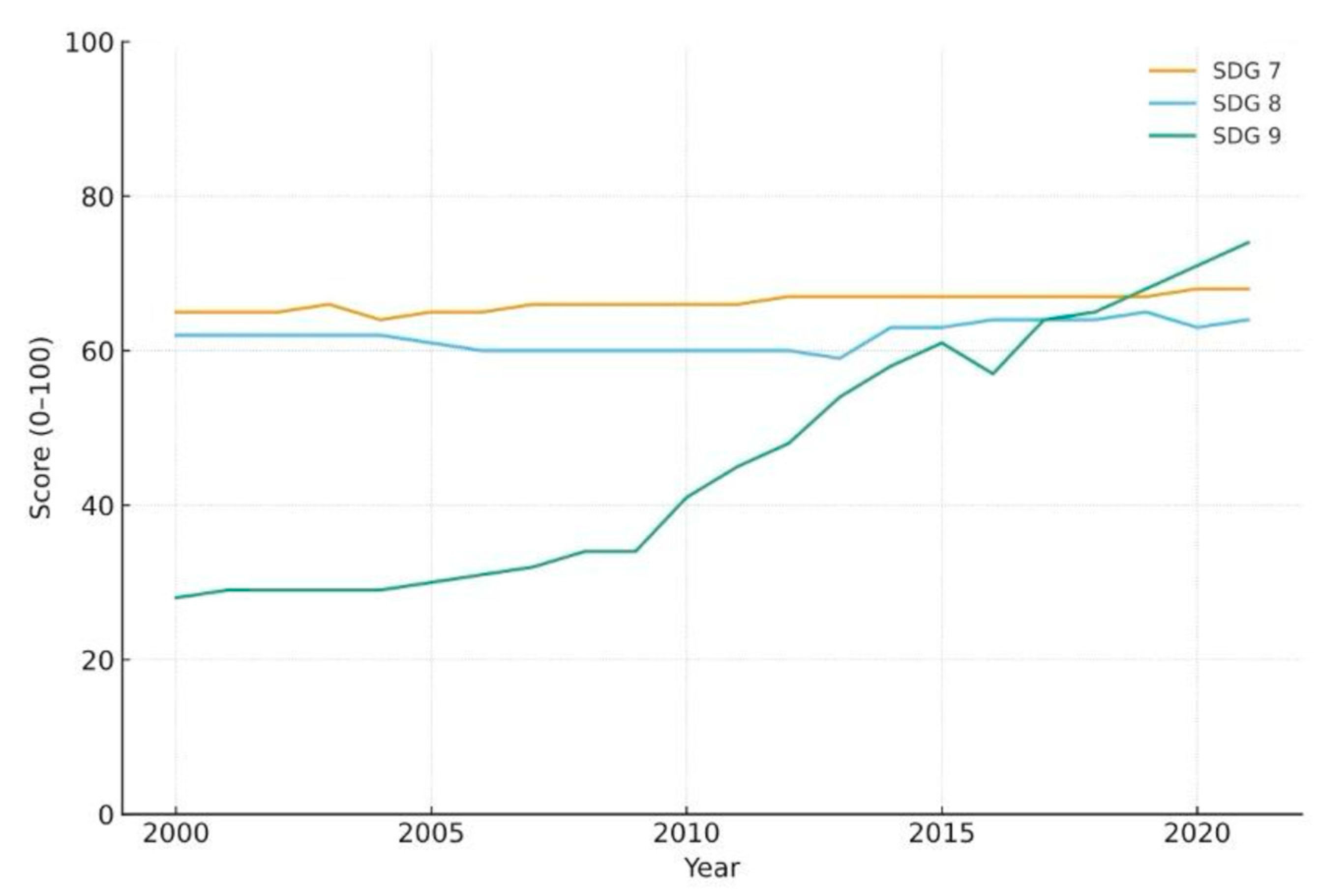

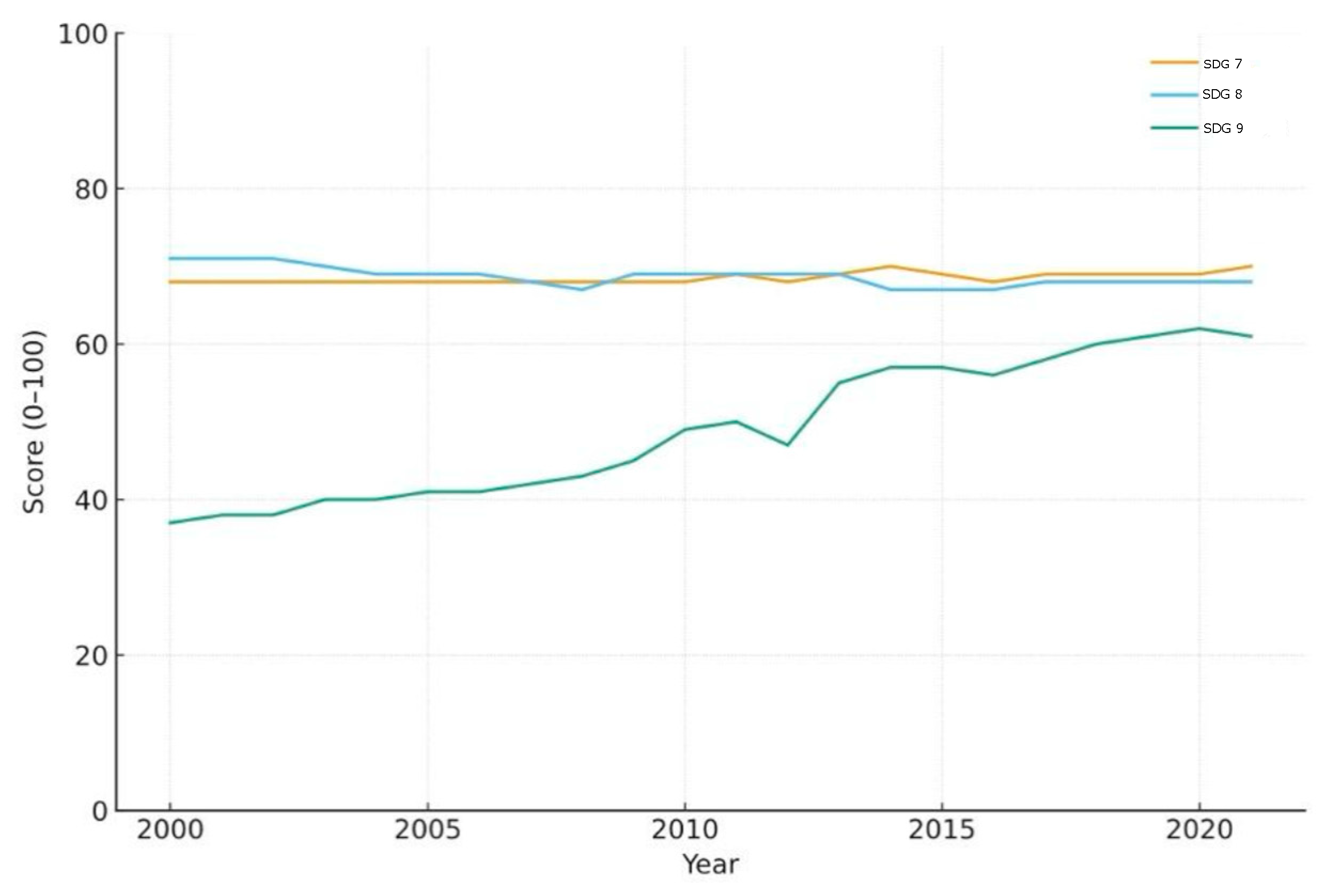

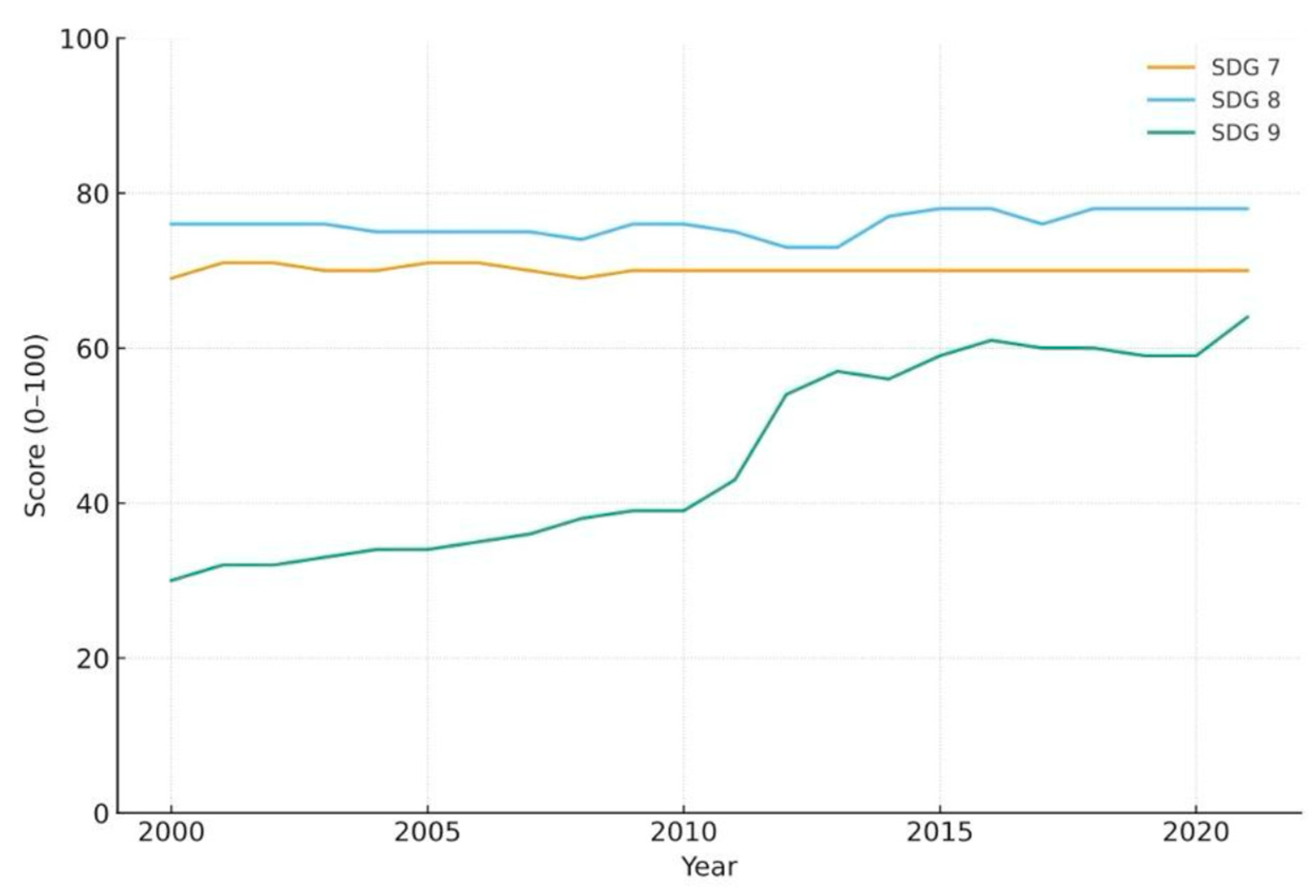

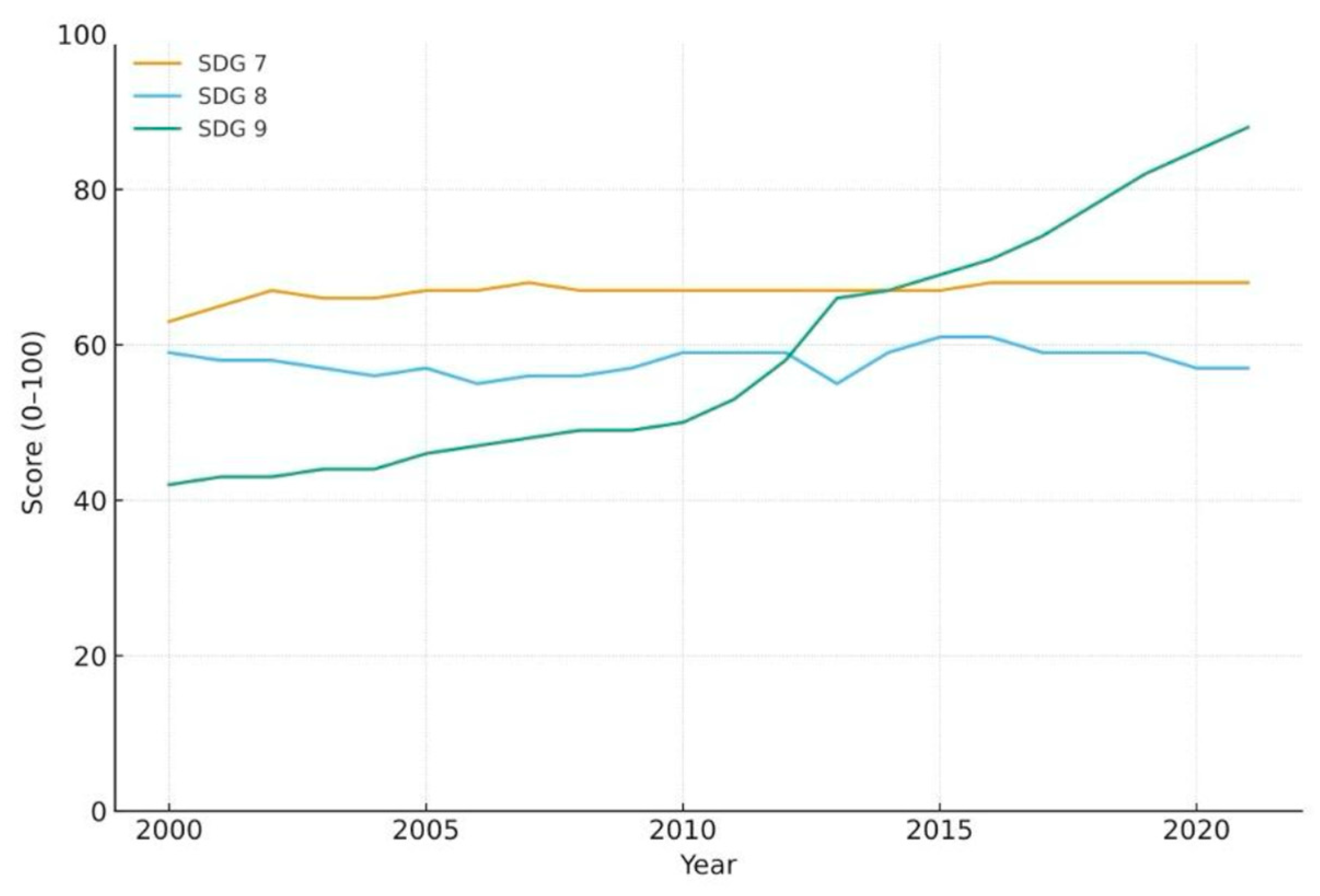

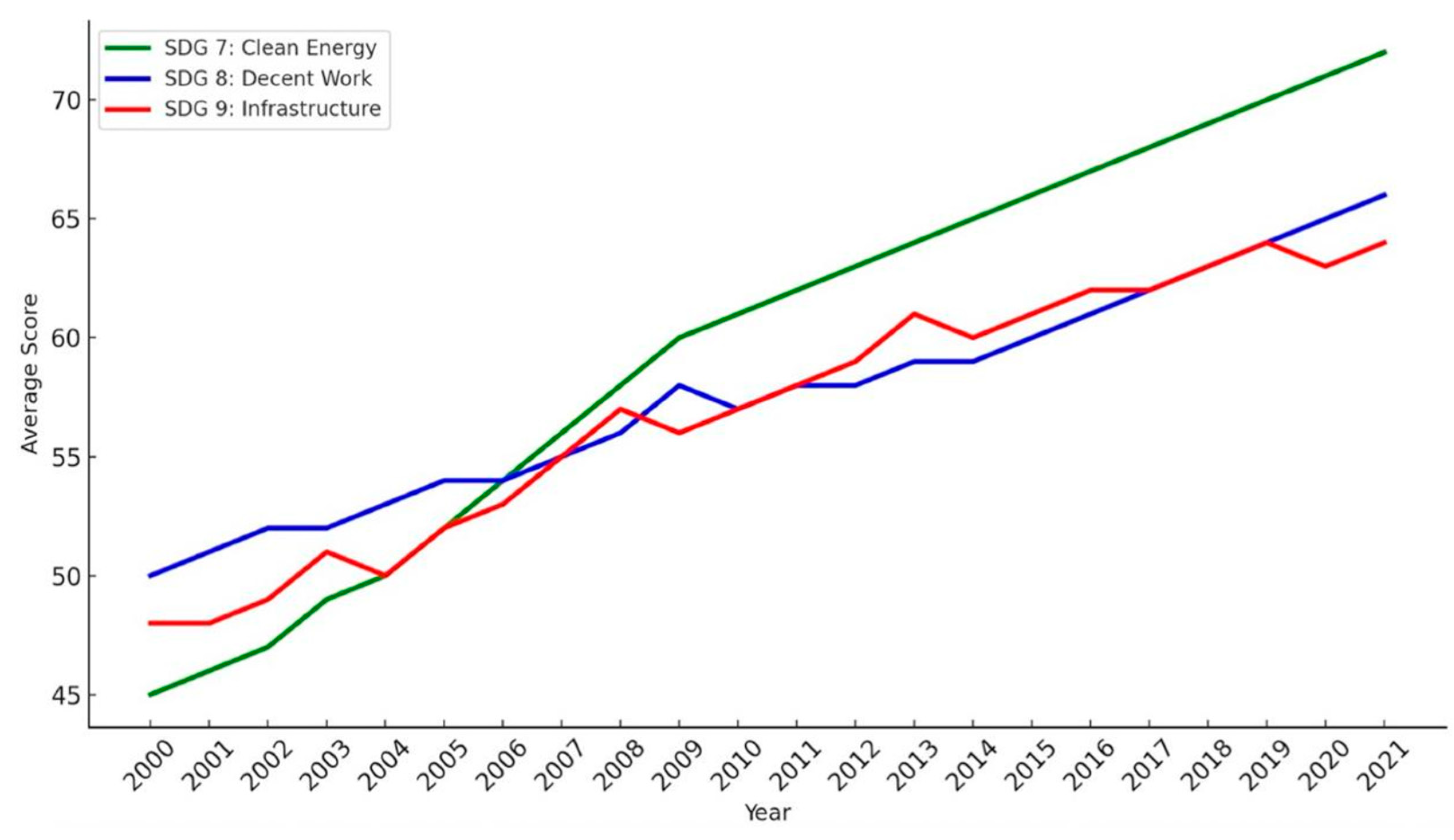

To aid interpretation, we plot country-year trajectories for SDG 7, SDG 8, and SDG 9 across the six GCC members during 2000–2021 (

Figure 2); one panel per country appear in

Appendix G Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4,

Figure A5 and

Figure A6. All series are shown on a 0–100 scale; pre-2015 values from the Sustainable Development Report are backcasted proxies of institutional progress.

Scope note (external validity). We deliberately restrict the panel to the six GCC economies to maximise institutional comparability in fiscal structures, labour-market segmentation, and energy-policy regimes. This design improves internal validity of the moderation tests. Extending the sample to non-GCC oil exporters would introduce substantial structural heterogeneity (governance, social insurance architecture, subsidy design) that warrants a distinct identification strategy; we outline such an extension in

Section 7.

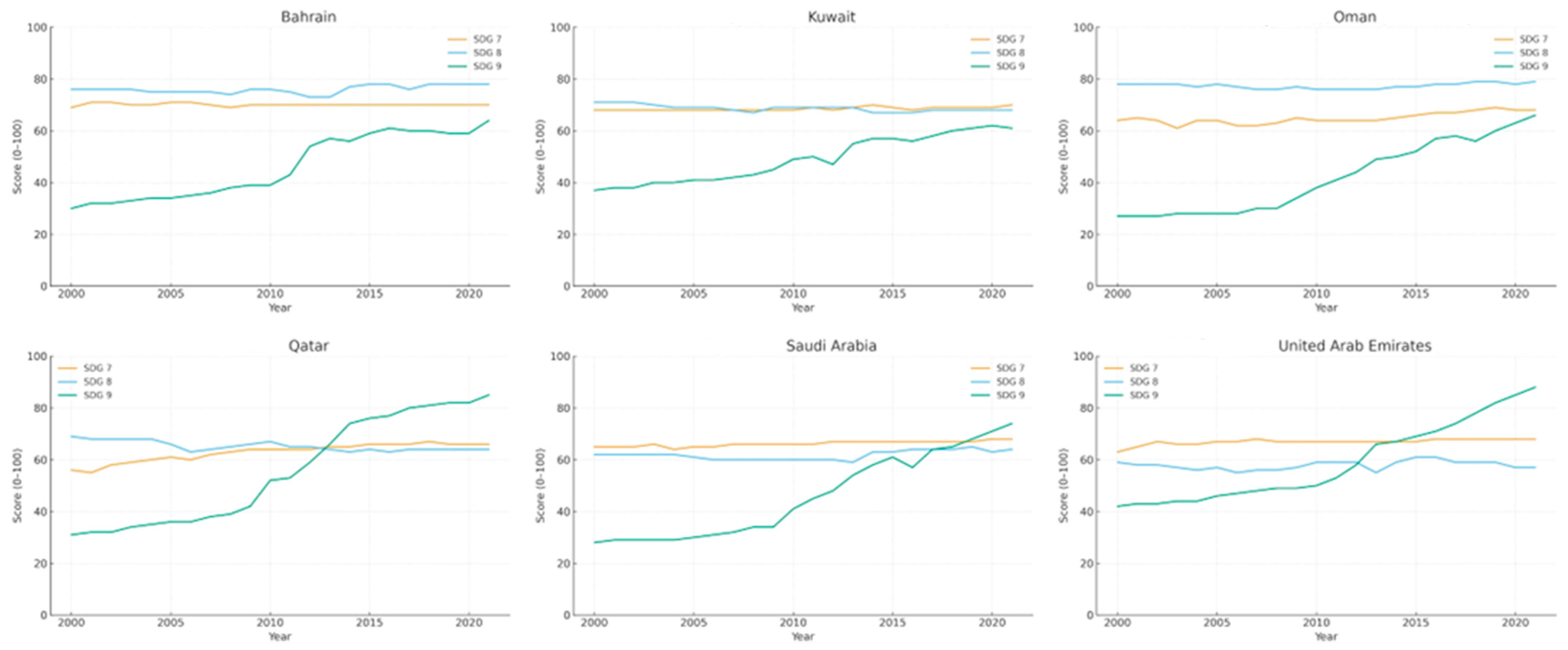

3.2. Descriptive Trends in SDGs 7–9

Figure 2 provides a country-level graphical comparison of SDG 7 (clean energy), SDG 8 (decent work), and SDG 9 (infrastructure/innovation) over 2000–2021. The small-multiple layout highlights timing and pace differences across GCC members and motivates our empirical tests of whether targeted SDG progress moderates unemployment responses to oil-rent shocks.

Appendix G Figure A1,

Figure A2,

Figure A3,

Figure A4,

Figure A5 and

Figure A6 present one figure per country for visual clarity.

3.3. Variable Construction and Definitions

The dependent variable is the unemployment rate, measured as the percentage of the labor force without employment but actively seeking work. We use the WDI/ILO modeled series “Unemployment, total (% of total labor force).” This captures macro-level labor market dynamics across the GCC. The key independent variable is oil rents, expressed as a percentage of GDP, representing Oil rent dependence, taken from the World Bank World Development Indicators (WDI). Following WDI, “Oil rents (% of GDP)” equals the value of crude oil production at world prices minus total production costs, scaled by GDP. This variable captures the structural reliance of GCC economies on hydrocarbon revenues.

To examine whether sustainability policies moderate the labour market effects of oil rents, the analysis incorporates three Sustainable Development Goals as moderators: SDG 7 (Affordable and Clean Energy), SDG 8 (Decent Work and Economic Growth), and SDG 9 (Industry, Innovation, and Infrastructure). Goal scores are taken from the Sustainable Development Report (SDR 2024, SDSN/Bertelsmann Stiftung) and are reported on a 0–100 scale where higher values indicate closer achievement of SDG targets. SDR normalizes underlying indicators to common thresholds, aligns directions, and aggregates with equal weights within each goal to form the goal score; the composite SDG Index (used in Model D) is the mean across goals. For interpretation, SDG 7 typically covers access to modern energy/clean cooking, renewable-energy penetration, and energy intensity; SDG 8 covers employment/unemployment, youth NEET/inclusion and labour-standards/protection; SDG 9 covers industrial capacity, innovation, and infrastructure/connectivity proxies. As noted in

Section 3.1, values prior to 2015 are SDR backcasts and should be read as proxies for sustainability-related institutional trajectories rather than direct policy implementation [

51].

Interaction terms between oil rents and each SDG index are introduced in the model to estimate their conditional effects. A statistically significant and negative coefficient on these interaction terms would suggest that SDG progress dampens the adverse impact of oil dependence on unemployment. Accordingly, higher SDG scores are interpreted as stronger buffering capacity in the OilRent × SDG interactions.

Control variables include GDP growth (annual %) to account for macroeconomic expansion or contraction and inflation, measured by the GDP deflator, to capture price stability and monetary influences.

We retain this parsimonious set because it maps directly to the buffering channels developed in

Section 2 (SDG 7—energy transition/diversification; SDG 8—institutions and social protection; SDG 9—infrastructure/innovation) while preserving coverage in a small-N GCC panel and avoiding multicollinearity and instrument proliferation in the System GMM specification.

Aggregation choice for SDG 8. We employ the SDSN SDG 8 composite (0–100) to retain full country-year coverage and comparability in a small-N panel. Disaggregating SDG 8 into multiple sub-indicators would (a) materially shrink balanced coverage, (b) introduce multicollinearity among highly correlated sub-metrics, and (c) proliferate interaction terms, exacerbating instrument-count and power concerns in System GMM. Accordingly, coefficients should be read as average moderation effects of SDG 8; in

Section 7 we outline a disaggregated agenda for future work.

Because SDG values for 2000–2014 are backcasted, cross-country differences in those years may partially reflect data coverage and methodology. To mitigate comparability concerns, we include country fixed effects (absorbing time-invariant institutional levels). Interaction coefficients with oil rents are therefore interpreted as average moderation effects conditional on these controls.

3.4. Empirical Strategy and Model Specification

This study employs a three-step modelling strategy to examine the impact of oil rents on unemployment and assess how SDG progress moderates this relationship. Each model progressively addresses different aspects of the research question: baseline effects, moderation, and endogeneity. Allowing for dynamics is consistent with structural evidence that oil-price volatility transmits to unemployment over time [

53]. We interpret the SDG interaction terms as conditional moderation effects (associations) rather than causal impacts.

All models include country fixed effects

μi and year fixed effects

δt to absorb time-invariant heterogeneity and common global shocks (e.g., 2008–2009, 2014–2016, 2020–2021). Given

δt we do not add separate crisis dummies in the baseline to avoid over-parameterization and, in System GMM, instrument proliferation;

Section 7 outlines extensions using dated crisis indicators to probe heterogeneous exposure. We model the moderating role of SDGs 7–9 as linear interactions with oil rents to recover average marginal effects within the observed range. This choice preserves parsimony in a small-country panel and avoids instrument proliferation in the System GMM setting; coefficients should therefore be interpreted as local average moderation effects rather than evidence of thresholds or nonlinearities. Although fixed effects, dynamics, and internal instrumentation in System GMM mitigate confounding and simultaneity, they do not by themselves identify the direction of causality between SDG progress and unemployment. We interpret the SDG interaction terms as conditional moderation effects (associations) rather than causal impacts. Although fixed effects, year effects, dynamics, and internal instrumentation in System GMM mitigate confounding and simultaneity, they do not by themselves identify the direction of causality between SDG progress and unemployment.

Model A: Baseline Specification

The first model estimates the direct relationship between oil rents and unemployment, controlling for key macroeconomic factors:

This model serves as the foundation by isolating the average effect of oil rents on unemployment across the GCC sample.

Model B: SDG-Moderated Specification (Disaggregated)

To assess how specific SDG targets influence this relationship, Model B introduces the scores for SDG 7 (energy), SDG 8 (decent work), and SDG 9 (infrastructure), along with their interaction terms with oil rents:

Model C: Dynamic Specification (System GMM)

To address possible endogeneity from reverse causality or omitted factors, Model C adopts a dynamic panel approach with two-step System GMM estimation:

Controls include GDP growth and inflation. Lagged unemployment accounts for persistence, while GMM instrumentation addresses endogeneity. Windmeijer-corrected standard errors are used for robust inference.

Model D: Composite SDG Moderation Specification

To test whether the moderating effects observed in Model B and Model C are driven by individual SDG dimensions or by broader development progress, we estimate a fourth model using a composite SDG index. This model includes an interaction term between oil rent and the composite SDG score to assess whether general sustainability advancement moderates the relationship between oil dependence and unemployment. Formally, the model is specified as:

All models include country fixed effects (μi) and year fixed effects (δt) to absorb time-invariant heterogeneity and global shocks (e.g., 2008–2009, 2014–2016, 2020–2021). The SDG Index represents a unified 0–100 score summarizing multiple SDG dimensions. As in earlier models, controls include GDP growth and inflation; fixed effects account for unobserved heterogeneity across countries and time.

3.5. Estimation Procedure

The analysis begins with stationarity checks using the Im–Pesaran–Shin (IPS) and ADF–Fisher unit root tests to avoid spurious regressions. Cointegration is assessed using the Kao and Pedroni tests to confirm long-run equilibrium relationships among the variables.

Estimation proceeds with fixed effects (FE) and random effects (RE) models. The Hausman test determines the preferred model structure; where FE is favored, it is retained to control for unobserved heterogeneity. Driscoll–Kraay standard errors are used to correct for heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-sectional dependence.

Diagnostic checks include the Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for multicollinearity, the Wooldridge test for serial correlation, and the Breusch–Pagan/Cook–Weisberg test for heteroskedasticity.

All specifications include country fixed effects (μi) and year fixed effects (λt) to absorb time-invariant institutional differences and common shocks; standard errors are reported with country clustering and Driscoll–Kraay corrections as appropriate.

3.6. Sensitivity and Robustness Analysis

To ensure the reliability of our findings, we apply robustness checks targeting model specification, measurement validity, and endogeneity. All specifications include year fixed effects (

δt) to absorb common global shocks; accordingly, we do not add separate crisis dummies in the baseline to avoid over-parameterization and, in System GMM, instrument proliferation. First, we estimate a two-step System GMM model [

54,

55] with a lagged dependent variable and internal instruments (lagged levels and differences). Windmeijer-corrected standard errors are used. Diagnostics (reported in

Section 4.6/

Appendix E) show no second-order serial correlation (AR (2)) and acceptable instrument validity (Hansen), with a significant Wald χ

2.

Second, we re-estimate the SDG-moderated specification with country-clustered OLS, which yields qualitatively similar signs and significance, complementing the main Driscoll–Kraay fixed-effects results (

Table A1).

Third, we assess measurement robustness by replacing the disaggregated SDG scores with a composite SDG index (Model D). The oil-rent interaction remains significant, although the index itself is less informative than the disaggregated goals, indicating domain-specific moderation.

Together with unit-root and panel-cointegration evidence (

Appendix A and

Appendix B), these checks indicate that our results are not artifacts of estimator choice, error structure, or SDG measurement. In the baseline, we rely on year fixed effects (

δt) rather than separate crisis dummies to avoid over-parameterization and, in System GMM, instrument proliferation; future work could replace or complement

δt with dated crisis indicators (2008–2009; 2014–2016; 2020–2021) and interact them with country characteristics to study heterogeneous exposure.

4. Results and Discussion

As a preview, results are robust across fixed effects with Driscoll–Kraay SEs, country-clustered OLS, and two-step System GMM; GMM diagnostics (AR(2), Hansen) are satisfactory, and conclusions are unchanged when using a composite SDG index. Throughout this section, we describe moderation patterns as associations. Statements about “attenuation” refer to negative interaction estimates and should not be read as proof of causal effects. This section reports the empirical findings on the relationship between oil rents and unemployment in the GCC countries, focusing on the moderating roles of SDG 7 (Clean Energy), SDG 8 (Decent Work), and SDG 9 (Industry and Infrastructure). The analysis proceeds in four stages: descriptive statistics, correlation diagnostics, model estimation using fixed-effects and system GMM, and robustness evaluations.

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

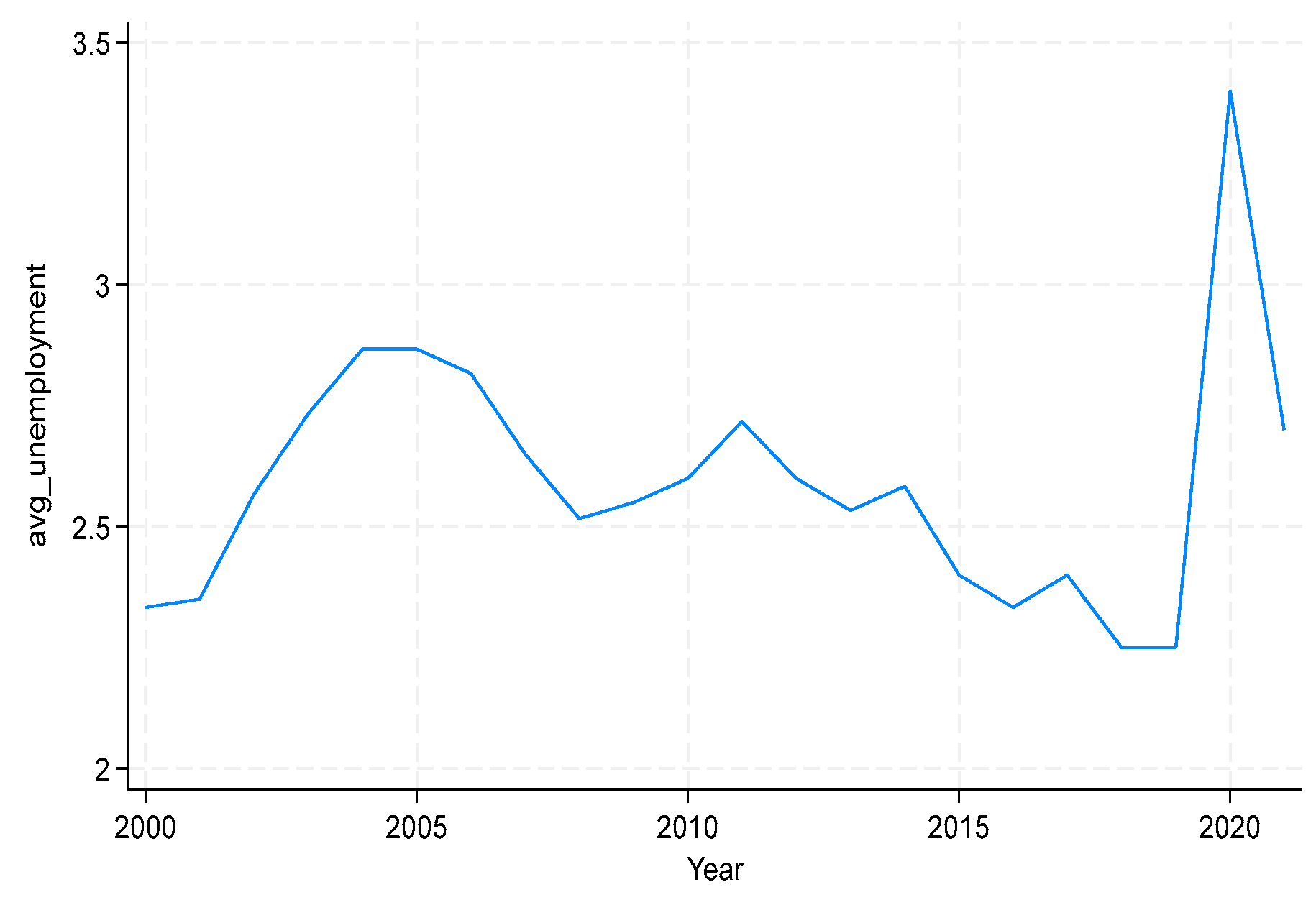

Table 1 summarizes the main variables for the six GCC countries over the period 2000–2021. The mean unemployment rate is 2.59%, with a range of 0.1% to 7.7%, suggesting significant cross-country and temporal variation. Oil rents average 23.84% of GDP (SD = 15.85), highlighting the central role of hydrocarbons in the region’s fiscal landscape and the volatility of external revenues.

Macroeconomic controls show typical resource economy features: GDP growth ranges from −7.1% to 26.2%, and inflation from −26% to 32.7%. SDG indicators show distinct patterns: SDG 7 (Clean Energy) has low dispersion (SD = 2.96), while SDG 9 (Industry and Infrastructure) shows high variability (SD = 15.90), reflecting uneven progress in industrial diversification across the region. SDG 8 (Decent Work) displays moderate dispersion.

These patterns support the use of panel regression and justify the inclusion of interaction terms between oil rents and each SDG, given the observable variation.

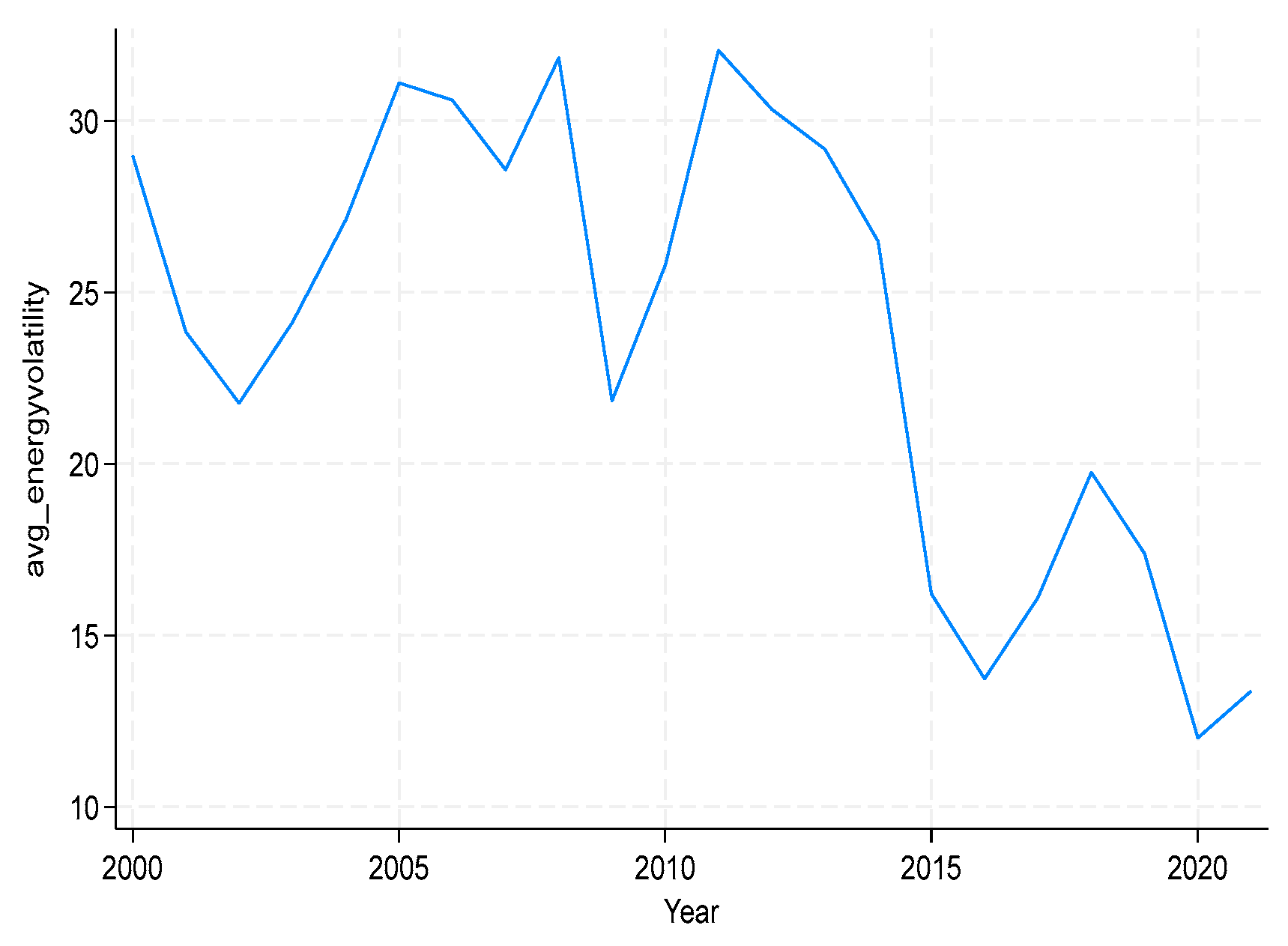

Figure 3 and

Figure 4 illustrate key trends in unemployment and oil rent volatility, reinforcing the rationale for conditional modelling. Unemployment shows a general decline until 2019, followed by a sharp uptick in 2020. Meanwhile, oil rent volatility declines markedly after 2014, reflecting policy shifts and global energy price stabilization.

4.2. Correlation Analysis

Spearman correlation coefficients (

Table 2) reveal that oil rents and unemployment are uncorrelated (ρ = 0.006), indicating that a linear specification may miss conditional dynamics. Oil rents are negatively associated with SDG 8 (ρ = −0.454,

p < 0.01) and SDG 9 (ρ = −0.168,

p < 0.10), suggesting that high oil dependency may crowd out efforts in labour inclusion and infrastructure. The correlation between oil rents and SDG 7 is negligible.

Inter-SDG correlations are moderate, particularly between SDG 7 and SDG 9 (ρ = 0.344, p < 0.01), allowing for joint model inclusion without multicollinearity risks.

4.3. Multicollinearity Diagnostics

Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values (

Table 3) confirm the absence of multicollinearity. All VIFs are well below 10, with a mean VIF of 1.50. Although SDG 9 has a higher value (5.79), it is still within acceptable bounds. These diagnostics validate the stability of the model estimations and justify the retention of all explanatory and interaction terms.

4.4. Econometric Validity and Model Selection

Pre-estimation diagnostics confirm that the variables used in the analysis are suitable for panel regression techniques. Unit root and cointegration tests indicate that key variables exhibit compatible integration orders and share stable long-run relationships (see

Appendix A and

Appendix B). Where appropriate, first-differencing and cointegration-adjusted specifications were applied to avoid spurious results. These findings support the use of level-based estimators such as fixed effects and system GMM to capture both short-term and long-term dynamics in the unemployment—oil rents—SDG framework.

Further diagnostic testing revealed heteroskedasticity, serial correlation, and cross-sectional dependence—common challenges in macro-panel settings (

Appendix C). To address these issues, we applied Driscoll−Kraay standard errors in the main specifications and performed robustness checks using country-clustered standard errors.

Model specification was guided by a Hausman test, which confirmed that unobserved country-specific factors are correlated with the explanatory variables (

Appendix D). This result supports the use of fixed-effects estimation across all regression stages, including both the baseline and SDG-moderated models. The fixed-effects approach allows for consistent estimation while controlling for structural and institutional heterogeneity across GCC countries—particularly relevant when assessing differentiated policy impacts of SDG implementation.

4.5. Main Regression Results: Baseline and SDG-Moderated Models

Model A: Baseline Estimation

The baseline model assesses the direct relationship between oil rents and unemployment, controlling for macroeconomic factors (

Table 4). The coefficient on oil rents is positive but statistically insignificant (β = 0.0104;

p = 0.206), suggesting no direct effect of oil rent fluctuations on unemployment when averaged across countries and time.

GDP growth is highly significant and negatively signed (β = −0.0900; p < 0.001), confirming that economic expansion consistently lowers unemployment. Inflation exerts a marginally significant positive effect (β = 0.0117; p = 0.096), possibly reflecting temporary cost-push effects or weak nominal wage adjustments.

The model explains only a small portion of the variance in unemployment (R2 = 0.057), supporting the hypothesis that structural and policy factors—particularly sustainability-related measures—may moderate the labour market effects of oil rents.

Model B: SDG-Moderated Estimation

Model B tests whether specific Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) moderate the relationship between oil rents and unemployment (

Table 5). The results show that SDG 8 (Decent Work) has the strongest moderating effect. The interaction term Oil Rent × SDG 8 is negative and highly significant (β = −0.0127,

p < 0.001), suggesting that stronger labour inclusion and employment protections help reduce the unemployment risks linked to oil rent volatility.

The interaction between Oil Rent × SDG 7 (Clean Energy) is positive and statistically significant (β = 0.0074,

p = 0.047). While this may initially seem counterintuitive, it aligns with the theoretical expectation that, in oil-dependent economies, early stages of clean energy transitions often involve adjustment costs—such as job losses in fossil sectors or delayed returns from renewable investments. However, over time, clean energy expansion contributes to labour market stabilization and sectoral diversification. This dynamic—short-term disruption followed by long-term benefits—has been noted in prior literature on energy transition in rentier states (e.g., ref. [

24]). We recognize that lagged or nonlinear specifications could shed additional light on the role of SDG 7. However, given the limited time span and small cross-sectional dimension of our panel, estimating such extensions would risk overfitting and unreliable instruments in dynamic models. For this reason, we restrict our analysis to contemporaneous interactions. We note, however, that future studies with longer panels could examine whether the transitional costs observed here give way to stabilizing effects at later stages of the clean energy transition.

In contrast, Oil Rent × SDG 9 (Infrastructure) is statistically insignificant (

p = 0.493), indicating no consistent moderating role. This aligns with theoretical perspectives suggesting that infrastructure investment, while critical for long-term productivity and growth, often has delayed labour market effects [

56]. In the context of GCC economies, large-scale infrastructure projects may not be well integrated with inclusive employment policies or may concentrate in capital-intensive sectors, offering limited short-term job creation. Prior studies (e.g., ref. [

57]) also note that infrastructure development in resource-rich states tends to prioritize economic diversification or prestige investments over labour absorption. This may explain the weak moderating role observed in our results.

The control variables behave as expected: GDP growth is significantly associated with lower unemployment (β = −0.0883, p < 0.001), confirming its role as a key driver of labour market outcomes. In contrast, inflation shows no statistical significance, suggesting limited short-term impact on unemployment in the GCC context.

These findings provide empirical support for Hypothesis H1, which proposed that the labor market effects of oil rents are conditional on sustainability-related reforms. The significant interaction with SDG 8 aligns with labour economics theories that emphasize the protective role of inclusive employment institutions under external shocks (e.g., [

33,

58]). Similarly, the positive but initially disruptive impact of SDG 7 supports the view that clean energy transitions, while destabilizing in early phases, become stabilizing over time—a dynamic echoed in energy transition literature [

24,

34]. The weak result for SDG 9 suggests that not all sustainability domains provide equal buffering capacity, reinforcing Hypothesis H2: disaggregated SDG indicators offer better explanatory power than composite indices. This finding aligns with prior studies (e.g., refs. [

59,

60] that caution against the overuse of composite SDG scores, arguing that they may obscure the distinct economic roles of individual development goals.

To contextualize the regression findings, this figure illustrates the average progress in SDG 7 (Clean Energy), SDG 8 (Decent Work), and SDG 9 (Infrastructure) across GCC countries over the study period. SDG 7 shows a strong and steady upward trend, suggesting consistent policy efforts toward energy transition—supporting its significant (though positive) interaction with oil rents observed in Model B. SDG 8 also rises over time but with visible year-to-year fluctuations. This visual pattern aligns with the regression results showing SDG 8 as the strongest stabilizing factor, despite some contextual variability. In contrast, SDG 9 displays irregular and volatile progress, consistent with its statistically insignificant moderating effect in the regression analysis. These descriptive trends offer additional context for understanding how sector-specific SDG implementation may shape labor market responses to oil price shocks. The model explains approximately 55% of the variation in unemployment (R2 = 0.547), with a strong overall fit (F(9, 115) = 45.52, p < 0.001; Root MSE = 1.277; Observations = 132).

These trends support the view that targeted progress in specific sustainability domains enhances the labour market’s resilience to oil-driven shocks.

Figure 5 illustrates the average trends in SDG scores across GCC countries from 2000 to 2021, highlighting the distinct trajectories of SDG 7 (Clean Energy), SDG 8 (Decent Work), and SDG 9 (Infrastructure), which align with the regression-based interpretations discussed above.

4.6. Model C: Addressing Endogeneity Using System GMM

To account for potential endogeneity, a dynamic panel System GMM model was estimated. The lagged dependent variable was significant (L1. Unemployment: β = 1.059,

p < 0.001), confirming strong persistence in unemployment trends. The moderating effect of SDG 8 remained strong (Oil Rent × SDG 8: β = −0.0093,

p < 0.001), while the interaction with SDG 9 remained statistically insignificant (

Appendix E).

Oil rents remain statistically insignificant on their own, reinforcing earlier findings that oil dependency alone does not explain unemployment variation. However, the interaction terms reveal important moderating effects. The interaction between oil rents and SDG 7 (clean energy) is positive and significant, suggesting that countries with more advanced renewable transitions experience reduced labour market exposure to oil price shocks. Similarly, the negative and significant coefficient on the interaction with SDG 8 (decent work) confirms that inclusive labour institutions help buffer the employment effects of oil volatility.

Model diagnostics confirm the specification’s validity. The Arellano−Bond test indicates no second-order autocorrelation (AR(2):

p = 0.195), while AR(1) is marginally significant (

p = 0.066), as expected. The Hansen test yields a

p-value of 1.000, suggesting instrument validity, though potentially weakened by instrument proliferation. The Sargan test is significant (

p = 0.001), but this is considered less reliable due to its sensitivity to instrument count. The Wald test confirms joint significance of the regressors in the dynamic model (χ

2(9) = 38,286.28,

p < 0.001), supporting the explanatory relevance of the included variables. These results support the robustness of SDG 8 across specifications and confirm that the GMM estimation is not mis-specified (

Appendix F).

4.7. Validating SDG Moderation Effects Under Robust Estimators

First, to ensure the reliability of the moderated model (Model B), we conducted several robustness checks focusing on both estimation techniques and proxy validity.

We re-estimated the fixed-effects model using clustered standard errors by country, which allows for intra-country correlation in the error structure. The coefficients remained stable in magnitude and significance, confirming consistency with the main Driscoll−Kraay standard error estimates. Interaction terms involving SDG 7 (clean energy) and SDG 8 (decent work) retained their significance, while SDG 9 (infrastructure) continued to show limited moderating impact (see

Appendix G).

Notably, the interaction term for Oil Rent × SDG 7 becomes more statistically significant under clustered standard errors (p = 0.005), compared to the baseline fixed effects model (p = 0.047). This strengthens confidence in the moderating role of clean energy transitions, even when accounting for country-level correlation in errors. It suggests that SDG 7’s contribution to labour market stability is not only theoretically sound but also empirically robust under stricter estimation assumptions.

For SDG 8 (Decent Work), the interaction term remains highly significant across both models (p < 0.001), confirming its consistent and strong buffering effect on unemployment volatility. The robustness of this result under different error structures highlights the central role of inclusive labor market institutions in oil-dependent economies.

In contrast, SDG 9 (Infrastructure) continues to show no significant moderating effect in either model (p = 0.493 under fixed effects; p = 0.305 under clustered SEs). This consistency suggests that while infrastructure investment may contribute to long-term structural change, its short-run role in mitigating oil rent-induced labour shocks is limited.

Second, to test whether the moderating effect is driven by overall sustainable development or by specific policy areas, we re-estimate the model using a composite SDG index instead of disaggregated SDG scores. The results, presented in

Table 6, show that the interaction between oil rents and the SDG index remains statistically significant and negative (β = −0.012,

p = 0.005), consistent with H2. However, the SDG index itself is not significant (

p = 0.132), suggesting that broad sustainability performance is less predictive than specific SDG domains. Disaggregated estimates show that the moderating effects are largely driven by SDG 8 (decent work), with SDG 7 (clean energy) playing a secondary role and SDG 9 (infrastructure) showing no consistent effect. These findings reinforce the value of disaggregating SDG targets for better policy design in rentier economies.

Taken together, the empirical findings demonstrate that the impact of oil rents on unemployment in GCC countries is not uniform but highly conditional on national progress in selected SDG domains. While SDG 8 exhibits the strongest and most consistent moderating role, SDG 7 also plays a significant part when clean energy transitions are supported by targeted labour policies. In contrast, the weak role of SDG 9 highlights the need for better alignment between infrastructure planning and employment strategies. These differentiated effects warrant careful interpretation and offer several actionable lessons, which are discussed in the following section.

5. Policy Implications

This study set out to examine the conditional effects of oil rents on unemployment in the GCC, focusing on how Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 7, 8, and 9) moderate this relationship. Evidence from multiple estimation strategies—including fixed effects, Driscoll−Kraay, clustered standard errors, and System GMM—consistently shows that oil rents alone do not directly explain unemployment trends. Instead, their effects depend heavily on national progress in clean energy, labour inclusion, and industrial development. Model B results indicate that oil rents become marginally significant only when interacted with SDG indicators. SDG 7 (clean energy) shows a positive and significant interaction, suggesting that countries with stronger renewable energy transitions are less exposed to macro-labour volatility from oil shocks, though transitional disruptions may occur. SDG 8 (decent work) exhibits a strong negative interaction, indicating that inclusive labour institutions play a counter-cyclical role during commodity fluctuations. In contrast, SDG 9 (infrastructure) shows no significant moderating effect. These findings are reinforced when comparing with a composite SDG index. Although the oil rent × SDG index interaction is statistically significant, the index itself is not, highlighting that the moderating effect is not uniformly distributed across all SDGs. The comparative analysis confirms that SDG 8 is the most relevant development domain for buffering unemployment in oil-dependent settings. System GMM results confirm the robustness of these relationships even when addressing endogeneity and persistence in unemployment. The strong coefficient on lagged unemployment captures structural inertia common in rent-based economies. These findings are reinforced when comparing with a composite SDG index. Although the oil rent × SDG index interaction is statistically significant, the index itself is not, highlighting that the moderating effect is not uniformly distributed across all SDGs. The comparative analysis confirms that SDG 8 is the most relevant development domain for buffering unemployment in oil-dependent settings. System GMM results confirm the robustness of these relationships even when addressing endogeneity and persistence in unemployment. The strong coefficient on lagged unemployment captures structural inertia common in rent-based economies.

5.1. Institutional Heterogeneity in the GCC

Institutional heterogeneity across GCC members likely mediates the SDG–oil unemployment relationship. Differences in the public-sector share of employment, the design and enforcement of labor-market nationalization programs (e.g., hiring quotas and wage support), the scope and timing of energy-pricing/subsidy reforms, and statistical/administrative capacity can shape how SDGs 7–9 translate into labor-market resilience. In settings with larger public employment or slower reform implementation, the cushioning effect of SDG 8 may be stronger through employment protection and intermediation, while in countries that adjust energy prices and accelerate renewable deployment, SDG 7 can reduce exposure to oil-cycle volatility more quickly. Recognizing these institutional channels helps interpret cross-country variation in the coefficients without implying causal differences beyond the panel-average effects estimated here.

Illustrative country evidence. In Saudi Arabia, Nitaqat quotas and HRDF wage support expand active labor-market programs under SDG 8, while phased energy-price reforms support SDG 7; in the UAE, stronger Emiratization targets and fuel-price deregulation matter for the same channels; in Oman, Omanization and multi-year subsidy reforms alter incentives; and similar localization and pricing reforms operate in Bahrain, Kuwait, and Qatar. These patterns—and their macro implications—are documented in the IMF’s regional outlook and country reports [

19]. The results yield clear macroeconomic insights for oil-dependent economies pursuing sustainable development. First, investments aligned with SDG 7 are not merely environmental commitments—they function as economic diversification strategies with the potential to enhance employment stability. However, our findings also suggest that clean energy transitions may initially bring short-term labour disruptions, especially in oil-dependent economies where sectoral adjustment is gradual. The transitional disruptions may also reflect increased energy demand and emissions from high-growth sectors like transport, as observed in recent Saudi-based studies [

43]. This transitional friction requires complementary labour policies, such as reskilling programs, transitional employment schemes, or wage support to reduce social costs and ensure a smooth adjustment. Second, policies aligned with SDG 8, such as national employment strategies, vocational training, and labour market reforms —are shown to reduce unemployment sensitivity to exogenous shocks, reinforcing their role as macroeconomic stabilizers. These measures help economies absorb oil price fluctuations without sharp labour dislocations. Third, the lack of a significant moderating effect from SDG 9 suggests that infrastructure policy, if disconnected from labour dynamics, is unlikely to mitigate short-run employment volatility. For infrastructure to act as a labour market stabilizer, GCC policymakers must align capital investments with labour absorption strategies. This means shifting away from prestige or capital-intensive investments toward infrastructure that supports labour-intensive sectors, vocational training, and small- and medium-enterprise (SME) development. Without such integration, infrastructure-led development may continue to deliver long-run productivity gains without buffering short-run unemployment shocks—confirming concerns raised in the literature [

56]. More broadly, this study reframes SDG reforms not as development slogans but as functional instruments of macroeconomic adjustment. Rather than viewing SDGs as aspirational end-goals, policymakers should treat them as operational tools to manage structural risks in volatile, resource-based economies. Overall, the findings underscore the value of integrated, cross-sectoral approaches. Labour market stability is strongest when clean energy policies, inclusive employment frameworks, and economic diversification strategies are pursued in tandem. Breaking policy silos and aligning SDG implementation with macroeconomic planning is essential to building resilient, future-ready labour markets in the GCC.

5.2. Fiscal Policy Implications

Our results imply that fiscal instruments can strengthen the SDG–oil labor-market resilience channel. First, energy-pricing and subsidy reform can reduce procyclical exposure to oil cycles while creating fiscal space for SDG-aligned spending. To preserve equity, reforms should be paired with targeted cash transfers or lifeline tariffs. Second, modest and gradually rising emissions taxes (or fuel excises) can incentivize clean-energy adoption (SDG 7) and fund active-labor-market programs under SDG 8 (e.g., reskilling, wage support, intermediation). Third, earmarking part of the proceeds to infrastructure that is both productivity-enhancing and labor-absorbing (SDG 9)—for example, grid upgrades, public transit, and SME-supporting logistics—can improve short-run absorption while raising long-run growth. Finally, indexing selected energy taxes or subsidy savings to oil-price movements, together with fiscal rules or stabilization funds, can provide automatic stabilization of employment over the cycle. The design should follow gradualism and clear communication to manage transition costs and maintain social buy-in.

Taken together, the evidence supports a coordinated package: scale clean-energy investment while cushioning workers (SDG 7 + SDG 8), align infrastructure with labour absorption (SDG 9), and use energy-pricing reform/emissions taxes as funding anchors with transparent revenue recycling. Sequencing should be gradual, with clear communication and monitoring so measures act as automatic stabilizers as shocks and institutional capacity evolve.

6. Conclusions

This study examines how oil rent dependency shapes labour market outcomes in the GCC, focusing on the moderating role of SDGs 7, 8, and 9. Drawing on panel data from 2000 to 2021 and a range of econometric techniques—including fixed effects, robust standard errors, and dynamic system GMM—we find that the impact of oil rents on unemployment is not direct, but conditional on national progress in clean energy and labour inclusion. While oil rents alone show limited explanatory power, their interaction with SDG-aligned reforms—especially in energy and employment—significantly affects unemployment dynamics. Clean energy transitions (SDG 7) and inclusive labour structures (SDG 8) mitigate the employment volatility associated with oil price shocks. In contrast, SDG 9 (infrastructure) does not exhibit a consistent short-term moderating effect. This supports theoretical perspectives that infrastructure projects in resource-rich economies often lack integration with labor-intensive sectors or short-term employment policies, limiting their capacity to cushion oil-driven volatility. The comparative assessment with a composite SDG index shows that these stabilizing effects are largely driven by specific dimensions—particularly SDG 8—rather than overall SDG progress. This highlights the importance of disaggregated, sector-specific SDG frameworks in policy design, especially where employment sensitivity to commodity shocks is high. Theoretically, the study reframes SDG progress as a stabilizing force in macroeconomic policy, not merely a development aspiration. Empirically, it highlights how targeted reforms can reduce vulnerability in rent-dependent economies navigating energy transitions. For policymakers, the results stress that SDG 8 is more than a social benchmark—it functions as a macroeconomic stabilizer. SDG 7 also emerges as a critical pillar, offering long-term labour market benefits through clean energy transitions, though it may involve short-term adjustment costs. Meanwhile, SDG 9’s effectiveness requires stronger alignment with inclusive employment strategies to fulfill its labour market potential.

Future work could expand this framework by including sector-specific employment trends, evaluating the institutional quality behind SDG performance, or testing for nonlinear effects. Still, the evidence here supports a clear message: SDG-aligned reforms—when integrated with economic policy—offer a viable path to labour market stability in resource-rich, volatile economies. Building on these findings, the following section outlines the study’s limitations and potential directions for future research.

In sum, the moderation effects we document translate into concrete fiscal choices. Well-sequenced energy-pricing reform, calibrated emissions taxation, and disciplined recycling of revenues toward SDG 8 programs and SDG 9 infrastructure can operationalize the resilience mechanism we identify. These measures complement clean-energy progress under SDG 7 and offer a cohesive, counter-cyclical toolkit for oil-dependent GCC economies.

7. Limitations and Future Research Directions

This study offers novel empirical evidence on how selected Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs 7, 8, and 9) moderate the link between oil rents and unemployment in Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. However, several limitations should be noted. First, the analysis is limited to data available up to 2021. While this period captures major economic adjustments following the COVID-19 pandemic, extending the dataset beyond 2021 could provide additional insight into post-pandemic recovery patterns and recent geopolitical shocks affecting global energy markets.

Second, the study relies on annual panel data and back-casted SDG indicators, which, though harmonized across countries, may not fully reflect the institutional depth or policy enforcement behind each SDG target. Backcasted SDG values (pre-2015) may be smoother and less variable than post-2015 observations, which can affect visual trends and estimates. To test comparability, future work could (i) re-estimate models on 2015–2021 only and (ii) complement SDG indices with country-specific administrative indicators (e.g., programme coverage, subsidy-reform milestones). Incorporating real-time, country-level institutional metrics would further strengthen robustness.

Third, while the System GMM estimation mitigates endogeneity concerns, potential dynamic feedback effects—such as how unemployment trends influence sustainability policies—remain an avenue for further investigation. Our estimates do not establish whether SDG progress causes lower unemployment sensitivity or whether stronger labour markets facilitate faster SDG achievement. Future work could: (i) estimate panel VAR/Granger-causality models to study lead–lag patterns; (ii) implement event-study or staggered difference-in-differences designs around dated policy milestones (e.g., labour-market nationalization rounds, wage-support programmes, energy-pricing/subsidy reforms); and (iii) use distributed-lag or threshold specifications for SDG channels to assess delayed or nonlinear effects. These designs would help clarify directionality beyond the conditional associations documented here. Relatedly, the SDG–oil–unemployment linkage may involve nonlinear, threshold, and lagged dynamics. For instance, SDG 8 (decent work) might only dampen unemployment volatility after a minimum level of institutional capacity or social protection is reached, while SDGs 7 and 9 (clean energy, infrastructure) may display delayed effects as investments mature. Future work could estimate panel-threshold or smooth-transition models and incorporate distributed-lag structures for SDG variables, potentially conditioned on institutional-quality proxies, to test whether stabilizing effects “switch on” beyond critical levels and materialize with lags. External validity beyond the GCC. To assess generalisability, future work can replicate the moderation design on a broader set of oil exporters (e.g., Algeria, Nigeria, Mexico, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Norway, Russia) using the same WDI/SDSN sources, adding region and income-group fixed effects, and formally testing heterogeneity via an OilRent × SDG × GCC triple interaction. A matched-comparators approach (e.g., propensity scores on pre-sample GDP per capita, export concentration, fiscal capacity, and labour-institution proxies) would further align baseline characteristics and help separate structural differences from policy effects. Finally, comparative analyses involving other oil-dependent regions (e.g., North Africa or Central Asia) could broaden generalizability and offer cross-regional insights into sustainability-driven labour-market resilience. By recognizing these limitations, the study provides a foundation for more comprehensive research that integrates broader datasets, alternative modelling strategies, and deeper institutional diagnostics to better understand the mechanisms through which sustainable development goals enhance macroeconomic stability in resource-rich economies.

External validity beyond the GCC: To assess generalisability, future work can replicate the moderation design on a broader set of oil exporters (e.g., Algeria, Nigeria, Mexico, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, Norway, Russia) using the same WDI/SDSN sources, adding region and income-group fixed effects, and formally testing heterogeneity via an OilRent × SDG × GCC triple interaction. A matched-comparators approach (e.g., propensity scores on pre-sample GDP per capita, export concentration, fiscal capacity, and labour-institution proxies) would further align baseline characteristics and help separate structural differences from policy effects.