Abstract

The rapid urbanization process has exacerbated the urban heat island (UHI) effect in megacities like Shanghai. Urban green infrastructure (UGI) plays a crucial role in mitigating the UHI effect; however, its cooling capacity is subject to various urban land development patterns. This study examined 39 typical locations in downtown Shanghai to measure how urban land development patterns affect the UGI’s cooling capacity. Using a data-driven framework, we identified 12 key influencing factors and explored 4 interactions for building three regression models: multiple linear regression (MLR), partial least squares regression (PLSR), and support vector regression (SVR). For each of these models, we considered two variations: a basic model neglecting interactions and an enhanced model including interactions. Results showed that all enhanced models outperformed their basic counterparts. On average, the enhanced models increased their predictive power by 14.59% for training data and 32.15% for testing data. Additionally, among the three enhanced models, the SVR-enhanced models show the best performance, followed by the PLSR-enhanced models. Their mean predictive power increased by 8.33−37.43% for training data and 31.77−43.558% for testing data vs. the MLR-enhanced models. Overall, our findings revealed that impervious surfaces contribute positively to urban warming, while UGI acts as a negative contributor. Moreover, we highlighted how urban land development metrics, particularly the UGI’s percentage and spatial arrangements in relation to adjacent buildings, significantly affect the thermal environment. The findings can offer valuable insights for urban planners and decision-makers involved in managing UGI and developing strategies for UHI mitigation and urban climate adaptation.

1. Introduction

Since the era of the Industrial Revolution, global urbanization has accelerated the rapid expansion of urbanized and urbanizing areas. Until now, there has been cumulative evidence showing that rapid urbanization has profoundly altered the urban ecosystem, causing unprecedented environmental challenges to the sustainability of human society. Among these environmental challenges, the urban heat island (UHI) effect should be one of the key issues of particular concern. In big cities, factors such as dense populations, dominant impervious surfaces, increased energy consumption, and a deficiency of green spaces exacerbate the UHI effect during warm and hot seasons [1,2,3,4,5]. This intensification results in pronounced environmental pollution, increased energy consumption, heightened carbon emissions, and increased health risks [6,7,8,9,10]. Moreover, the synergistic urbanization and global warming exacerbate the adverse consequences of the UHI effect, as evidenced by numerous case studies reported in Asian, European, African, and American countries [11,12,13,14].

China has been one of the fastest-urbanizing countries over the past three decades, with an urbanization rate 2.14% higher than the global average and an annual urban growth rate of 7.9% [15,16]. This trend is expected to continue for the next 50 years or even longer, positioning China as the world’s leading engine of urban growth [17]. However, this rapid urbanization also emphasizes the country’s vulnerability to climate change. In this sense, Shanghai, as a representative megacity at risk from climate change, has seen a steady increase in the UHI effect since the 1980s. The number of hot summer days in the downtown area has significantly surpassed that of the suburban and exurban regions [18]. The degradation of the urban thermal environment negatively affects the quality of living for residents and restricts their outdoor activities. This issue is also closely related to urban energy consumption, environmental pollution, climate adaptability, and the sustainability of the urban ecosystem [19,20]. Therefore, both qualitatively and quantitatively investigating the urban thermal environment, particularly its underlying causes and driving factors, is vital for effective decision-making regarding UHI mitigation [21].

Urban green infrastructure (UGI), also referred to as ecological infrastructure, encompasses a wide range of landscape elements within city boundaries. These include urban parks and green spaces, as well as natural or semi-natural landscapes such as vegetation, lakes, and streams that are influenced by human activities. UGI’s cooling effects primarily depend on three aspects: transpiration from vegetation, shading provided by tree canopies, and the evaporation from water bodies [22,23]. Empirical studies have demonstrated that well-designed UGI patches can reduce ambient temperatures by up to 3.71 °C during summer months. Furthermore, the UGI’s cooling capacity increases significantly with patch size. As reported, UGI patches size over 5 hectares may produce a maximum cooling distance exceeding 200 m [24]. Compared with active cooling systems relying on fossil fuels, UGI offers nature-based cooling with advantages such as zero energy consumption, low maintenance costs, and near-zero carbon emissions. Therefore, UGI has become a vital component of ecological infrastructure for adapting to climate change and a cost-effective strategy for developing climate-resilient cities.

Currently, UGI planning and design often require a balance between esthetic appeal, functional utility, and ecological benefits. The cooling performance of such green spaces is largely influenced by two sets of factors: (1) the intrinsic biophysical attributes of the green space itself—such as vegetation type and patch size—and (2) its spatial configuration within the urban fabric. At a fine scale, the morphological characteristics of green patches (e.g., edge shape, internal structure) may interact in complex ways with adjacent buildings and roadways. For instance, street orientation may affect the duration of solar exposure on green areas, building height may alter local airflow patterns, and dense building shadows may reduce the evapotranspirative cooling capacity of vegetation [25]. The effectiveness of UGI in cooling urban areas is influenced by various spatial features. In densely populated megacities, however, the large-scale expansion of UGI often faces challenges due to population pressures, economic development needs, and policy constraints. Therefore, it is nearly impossible to fully address the UHI effect solely through the widespread development of UGI. To effectively adapt to climate change and mitigate the impacts of UHI while safeguarding public health, strategies must be based on scientific evaluation systems. These systems should quantify key indicators, such as building density and the morphology of green patches, to assess their specific effects on cooling performance.

Existing studies have primarily focused on the individual impacts of regional climatic conditions, human activities, and green infrastructure characteristics on the UGI’s cooling effect [26,27]. The importance of factors influencing the cooling effect of UGI has primarily been quantified using a range of statistical techniques, including the standardized coefficient approach in linear regression [28], the Geodetector for analyzing variable interactions [29], the random forest algorithm that accounts for nonlinear effects [30], and the variance decomposition method for assessing intergroup variable importance [31]. Nevertheless, each of these methods has inherent limitations. The standardized coefficient approach and random forest cannot adequately address multicollinearity, the Geodetector is less effective in handling continuous variables, and variance decomposition fails to incorporate variable interactions. As a result, mechanism interpretation has often been partial. For instance, Ziter et al. identified 40% vegetation cover as a peak cooling threshold [28], while Kong et al. observed that a 10% increase in vegetation cover leads to a 0.83 °C reduction in land surface temperature (LST) [32].

The methodological limitations mentioned above have created a knowledge gap in understanding how urban land development patterns influence the UGI’s cooling effects. This gap limits the assessment of UGI’s cooling potential, presenting a theoretical barrier to optimizing the spatial arrangement of UGI and surrounding landscapes in urban planning. To tackle this issue, this study focuses on Shanghai, a representative megacity in China that is experiencing an intensified UHI effect due to rapid urban growth [33]. To address this issue, this study focuses on Shanghai, a representative megacity in China that is experiencing an exacerbated UHI effect due to rapid urban growth. This study aims to test and compare several popular regression models for quantitatively examining the complex relationships between influential factors of urban land development patterns and the urban thermal environment indicated by LST. The authors seek to provide practical guidance for reinforcing the UHI’s cooling effect and mitigating the UHI effect.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

The geographical extent of Shanghai falls within latitudes 31°32′ N–31°27′ N and longitudes 120°52′ E–121°45′ E. It is situated on the eastern edge of the alluvial plain of the Yangtze River Delta (Figure 1). It borders the East China Sea to the east, faces Hangzhou Bay to the south, and adjoins Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces to the west. As China’s economic capital, it yields approximately 5% of China’s GDP within its jurisdiction, accounting for 0.06% of China’s national territory [34]. The average elevation is around 4 m, with the terrain gently sloping from the northwest to the southeast [35]. Shanghai has a typical northern subtropical monsoon climate, with an annual mean temperature of approximately 15 °C. The average temperature in summer reaches 28 °C, while in winter it drops to around 4 °C. Based on local temperature records from 1981 to 2024, the average daily temperatures in July 2024 ranged from 27 °C to 36 °C, with extreme highs reaching 40 °C. In August, the average temperatures ranged from 27 °C to 37 °C, with the highest recorded extreme reaching 41 °C [36]. Consequently, downtown Shanghai usually suffers from the scorched summer days during these two months. Spatially, there exists a distinct pattern of summertime UHI effect between the urban core and urban fringe. To illustrate this varied spatial pattern of the UHI effect, we studied a total of 39 representative sample sites. These sites encompass a range of urban environments, including commercial facilities, residential communities, parks, universities, and colleges within the traditional urban core. Additionally, we examined commercial establishments, residential areas, industrial parks, and suburban parks located in the recently urbanized areas at the urban fringe. This variety represents the connection between different land development patterns and the corresponding levels of UHI intensity [33].

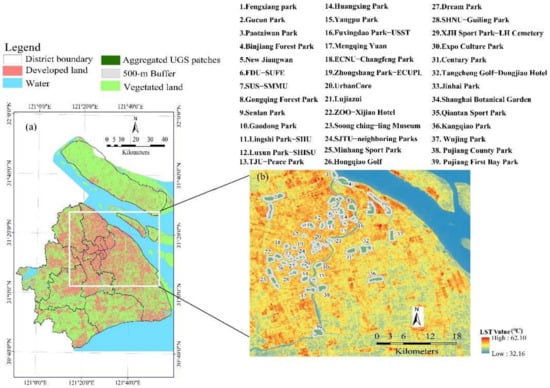

Figure 1.

Location of study area showing the location of thirty-nine sites. (a) Land use in Metropolitan Shanghai. (b) Location of thirty-nine sites affected by the surface urban heat island, as indicated by the summertime mean annual land surface temperature (LST) in 2013—2022 [33]. Among these sites, 4, 7, 12, 17, 18, and 36 are classified as slightly urbanized areas on the urban periphery, while sites 8, 13, 30, and 33 are identified as slightly to moderately urbanized areas. Sites 23, 24, 27, 29, and 37 represent moderately urbanized areas, and the remaining sites are categorized as highly urbanized areas.

2.2. Data Sources

This study uses a multi-source dataset comprising satellite remote sensing imagery and supplementary data collected between 2013 and 2022. The primary data source is the Landsat-8 OLI/TIRS imagery. Supplementary interpretation datasets include Sentinel-2 imagery, the commercial Digital Thematic Maps of Shanghai Beijing Digital Space Technology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China, (2015), field-surveyed building indicators within Shanghai, publicly accessible online data (used to assist in identifying green space and building distributions), commercial platforms such as LocalSpace Viewer©, Tianditu©, and the free platform Baidu Map© and their respective street-view services, as well as ground-truthing data collected by the research team.

These datasets can be referred to a recent publication [33]. Based on this work, we added three new sites and collected new data to explore how the urban land use features influence the UGS’s cooling effect from a new approach. Details are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of datasets used in this study.

2.3. Methods

2.3.1. Calculation of 12 Explanatory Variables Representing Urban Land Development Patterns

Urban land development patterns refer to the spatial configuration and utilization of land resources under anthropogenic influence, encompassing multidimensional characteristics such as land use structure, development intensity, functional layout, and ecological effects. As China’s largest economic hub, Shanghai contributes approximately 5% of the national gross domestic product (GDP) while occupying less than 0.1% of the country’s total land area. By 2024, its permanent resident population reached 24.80 million [39], of which 80% of the population resides within an area of 4000 km2. This area makes up the domain of downtown Shanghai, including the urban core, the newly urbanized area, and the urban periphery. In this study area, over 75% of the land is classified as developed land, including residential, commercial, and industrial uses [40].

Based on a data-driven analytical framework, this study selected 12 dual-dimensional landscape metrics to quantify the spatial heterogeneity of land development patterns in central Shanghai. These include six hardscape indicators and six softscape indicators. The first dimension comprises six hardscape variables that reflect urban development intensity: the proportion of building area (Building), the proportion of other impervious surfaces (OtherIS), mean building height (MBH), mean building distance (MBD), road density (RD), and floor area ratio (FAR). The second dimension includes six softscape variables that characterize the fragmentation of urban green infrastructure (UGI): proportion of UGI area (UGI), patch density (PD), landscape shape index (LSI), clumpiness index (CLUMPY), largest patch index (LPI), and connectivity index (COHESION).

Detailed definitions and calculation methods of each metric are provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Key Indicators Representing Urban Land Development Patterns impact LST in this study.

2.3.2. Regression Modeling

In this study, twelve indicators characterizing urban land development patterns were used as the independent variables. Meanwhile, the mean LST during five summer dates in 2013–2022 was used as the dependent variable. In this section, we adopted three widely used regression models to quantify the complex relationships between the independent and dependent variables as follows:

(1) Multiple Linear Regression (MLR)

Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) is a popular regression method based on the principle of Ordinary Least Squares (OLS). This method is widely applied for examining causal relationships between one dependent variable and multiple independent variables. It is primarily used for factor selection and statistical prediction. A specific type of multiple linear regression, referred to as complete regression, includes all potential independent variables in the model simultaneously to create a comprehensive regression equation. This approach enables a comprehensive evaluation of the potential impact of each variable on the dependent variable.

To test whether introducing the interactions between the independent variables will influence the model performance, we designed two variations for the MLR models. They contain a basic model neglecting interactions and an enhanced model including interactions. The basic model is expressed as follows:

In Equation (5), within the modeling framework, denotes the intercept term, and represents the number of predictors included in the model, constrained to 1 ≤ ≤ 12. The coefficients bi are the partial regression coefficients associated with the predictors xi, comprising six hardscape indicators (Building, OtherIS, RD, FAR, MBH, MBD) and six softscape indicators (UGI, LSI, PD, LPI, CLUMPY, COHESION).

The enhanced model is formulated as follows:

In Equation (6), f represents the interaction terms among the predictors, which can be flexibly configured based on the research objectives. The term ε represents the random error. This term accounts for the portion of variability that cannot be explained by the model, reflecting the discrepancy between observed values and model predictions. Herein, based on Spearman’s rank correlation result, we found a statistically significant correlation between the independent variables (see Appendix A Table A2). We further assumed four interactions that may have finite physical associations with the variance of the LSTs. These interactions are: Interaction1 represents UGI × CLUMPY × LPI × COHESION; Interaction2 denotes UGI × PD × LSI; Interaction3 refers to Building × Road Density × FAR × MBH; and Interaction4 represents Building × RD × FAR × MBH × UGI. Please note that these interactions were adopted by the PLSR- and SVR-enhanced models.

The model selection process adheres to rigorous criteria—not all candidate models are included. To ensure the stability of the results and the accuracy of predictions, we only retained models that produce reliable outcomes and exhibit low prediction bias. Additionally, in the final model, we considered only those combinations of predictors that were physically meaningful or statistically significant in explaining the variance of the response variable.

(2) Partial Least Squares Regression (PLSR)

Partial least squares regression (PLSR) is a statistical modeling technique well-suited for addressing multicollinearity between dependent and independent variables. The basic and enhanced forms of the PLSR model have the same structure as the MLR models. However, unlike the MLR models, PLSR models do not require fixed predictor variables and is tolerant of measurement errors, thus demonstrating significant robustness in uncertainty quantification [42,43]. It has been widely applied in fields such as chemistry [44], environmental science [45], and finance [46], and is particularly effective when dealing with high-dimensional data or small sample sizes. In the PLSR modeling, three to ten components were evaluated to select the competing models with better predictive power. After numerous attempting, five components yielding both higher R2 on the training and testing sets were adopted for further modeling.

(3) Support Vector Regression (SVR)

Support vector regression (SVR) is a non-parametric regression technique based on the principles of the support vector machine (SVM) algorithm. The core idea is to project the training dataset from a lower-dimensional space into a high-dimensional feature space via a kernel function, as with f(x) = wTx + b. This function achieves to effectively separate different groups of input data in a linearized manner. It seeks that the deviation between the predicted and actual values does not exceed a predefined threshold ε. Meanwhile, the weight vector w remains as small as possible, ensuring a smooth model [47]. SVR achieves this by incorporating an ε-insensitive loss function, which imposes no penalty for prediction errors within the ε margin but applies linear penalties for errors exceeding this threshold [48]. Compared to the MLR models, the SVR models typically perform better in modeling complex relationships between high-dimensional data. This method has been widely applied in ecological, environmental, geographical, and meteorological research [49,50].

In this study, all statistical analyses were conducted using the basic functions of R version 4.5 (R Core Team, 2024) [51] and a variety of specialized libraries. For example, library(pls) [52] was used to perform the PLSR analysis. In addition, library(e1071) was used to perform the SVR modeling [53].

2.3.3. Assessment of Regression Model Performance

An overall assessment of the performance of three regression models was conducted through the following steps. First, the data used for modeling was divided into a training set and a testing set. The training set consisted of 80% of the randomly selected data, which was utilized for model development. The testing set comprised the remaining 20%, which was employed to validate the predictive performance of the trained models. Second, to address the potential multicollinearity problem that may affect MLR models, we calculated the variance inflation factor (VIF), the coefficient of determination (R2), and the root mean square error (RMSE) for assessing model performance on the training and testing sets. In contrast, for PLSR and SVR models, which do not account for multicollinearity, the VIF is not applicable. Therefore, we used only R2 and RMSE to evaluate the model performance for these two datasets. The VIF is calculated using the following formula:

In Equation (1), Rj denotes the coefficient of determination obtained by regressing the j variable on all other explanatory variables. The VIF is used to assess the degree of multicollinearity among the independent variables. A VIF value exceeding 10 indicates the presence of severe multicollinearity, necessitating a dimensional reduction in the variables [54].

The coefficient of determination, R2, reflects the proportion of variance in the dependent variable that is explained by the model. A value closer to 1 suggests a higher goodness of fit. It is calculated using the following equation:

The RMSE is also an important metric for evaluating model performance. It quantifies the average deviation between predicted values and observed values, providing a direct measure of the model’s predictive accuracy. A lower RMSE value indicates a stronger generalization capability of the model. The formula for RMSE is as follows:

In Equation (4), n represents the sample size, denotes the actual value of the i-th observation, and is the predicted value for the i-th observation.

3. Results

3.1. Overall Linkage Between Different Land Development Patterns and LST

Figure 2 shows the clusters of 39 sampling sites that represent various land development patterns. By examining the relationships between the observations and the influential factors related to these patterns, we identified six categories of sites. Table 3 outlines the overall connections between different land development patterns and LST. Generally, it can be observed that sites with low to medium development pressure have relatively lower LSTs compared to those with high to very high development pressure, which tend to exhibit higher LSTs.

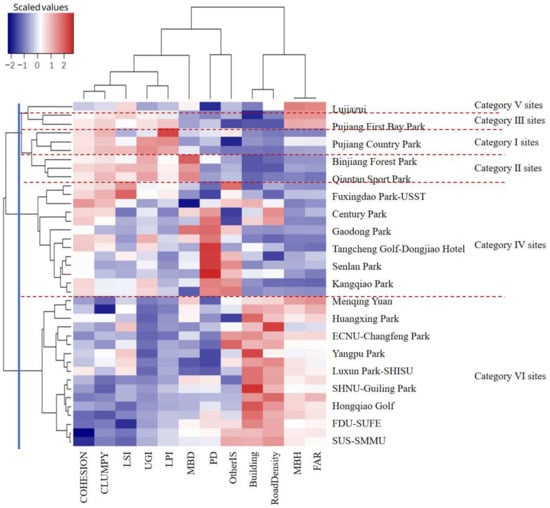

Figure 2.

Heatmap depicting the clusters of 39 sampling sites that represent different land development patterns. Note: The vertical blue line in this figure divides the observations into six categories, which are further separated by the red dashed lines. Due to space constraints, this figure only displays 20 sites; however, all sites are included in the analysis.

Table 3.

Overall linkage between different land development patterns and LST.

3.2. Results of Basic Regression Models

Table 4 shows the overall performance of three basic regression models on both the training and testing sets.

Table 4.

R2 and RMSE of the Three Basic Models on Training and Testing Sets.

On average, the MLR models achieved an R2 of 0.601 and an RMSE of 1.862 on the training sets. This indicates that the model explains approximately 60.1% of the variance in the dependent variable and has an average prediction error of about 1.862 units on the training sets. However, on the testing sets, the R2 dropped to 0.363, and the RMSE increased to 3.067, suggesting a decline in predictive performance and poor generalization capability.

The PLSR model yielded an R2 of 0.614 on the training sets, slightly higher than that of the MLR models, with a lower RMSE of 1.515. On the testing sets, the R2 was 0.479, outperforming the complete regression model, while the RMSE was 3.321, slightly higher than that of the complete regression. Overall, the PLSR model performed marginally better than the complete regression model on both training and testing datasets, likely due to its advantage in handling multicollinearity among predictors.

The SVR model achieved an R2 of 0.963 and an RMSE of 0.606 on the training sets, demonstrating a substantially better fit compared to the other two basic regression models. However, on the testing sets, the R2 decreased to 0.559 and the RMSE rose to 3.029, indicating potential overfitting. While the SVR model excelled on the training data, its generalization to unseen data was relatively limited.

In summary, across all three regression models, the models consistently exhibited significantly better performance on the training datasets than on the testing datasets.

3.3. Results of Enhanced Model Construction

Table 5 shows the overall performance of three enhanced regression models on both the training and testing sets.

Table 5.

R2 and RMSE of the Three Enhanced Models on Training and Testing sets.

As shown in Table 5, the MLR-enhanced model achieved a coefficient of determination R2 of 0.708 on the training set, representing a significant improvement compared to its basic model (R2 =0.601). Although this model’s RMSE on both training and testing sets was partially better than those of the PLSR and SVR models, all independent variables in this enhanced model exhibited VIFs greater than 10, indicating serious multicollinearity issues. Particularly, some perplexing results similar to those found in the basic model (Table 4) persisted, and the overall performance remained inferior compared to the other two enhanced models. In contrast, the PLSR-enhanced model showed a higher R2 of 0.767 and a lower RMSE of 1.337, demonstrating comparatively better overall performance. The SVR-enhanced model explained 97.3% of the variance of the LSTs on the training sets with the lowest RMSE. Although the averaged RMSE of the enhanced SVR models on the testing sets was slightly higher than that of the enhanced PLSR models, their R2 values were superior. This indicates that the enhanced SVR models demonstrated the strongest statistical explanatory power.

Specifically, the R2 for the MLR models on the training sets increased from 0.601 in the basic models to 0.708, while the RMSE decreased from 1.862 to 1.102. On the testing sets, the R2 rose from 0.363 to 0.491, and the RMSE dropped from 3.067 to 2.15. These results suggest that incorporating interaction effects improved the fitting and generalization performance of the MLR models on both the training and testing sets. The PLSR-enhanced models achieved an average R2 of 0.767 on the training sets, outperforming the basic models (R2 = 0.614). Accordingly, the average RMSE also decreased from 1.515 in basic models to 1.337 in enhanced models. On the testing sets, the average R2 improved from 0.479 to 0.647. Meanwhile, the average RMSE slightly decreased from 3.321 to 3.092. These results indicate that the inclusion of interaction terms enhanced the performance of the PLSR model compared to its basic counterpart on both the training and testing datasets. In contrast, the SVR-enhanced model achieved an average R2 of 0.973 on the training set, which is marginally higher than that of the basic models (R2 = 0.963). Consequently, the average RMSE for the enhanced models decreased from 0.606 to 0.537 compared to the basic models. However, on the testing dataset, R2 improved from 0.559 to 0.705, while RMSE increased from 3.029 to 3.257. This suggests that while the inclusion of interaction effects improved the fit of the SVR model on the training data, it slightly reduced its generalization ability on the testing set.

Overall, the three enhanced models outperformed their corresponding basic models, with the SVR-enhanced models showing the best comprehensive performance, followed by the PLSR-enhanced models. In contrast, the MLR-enhanced models.

4. Discussion

4.1. Analysis of Multicollinearity in the MLR Model

Numerous studies on the relationship between urban land use and thermal environmental responses have shown that higher proportions of impervious surface area, road density, and building coverage are typically associated with more pronounced urban warming effects [55,56,57]. In contrast, greater coverage of urban green infrastructure (UGI), higher values of metrics such as largest patch index, connectivity, and aggregation, are generally conducive to mitigating urban heat intensification [31,58,59]. Moreover, more complex landscape shapes and higher patch densities of UGI have been found to aggravate urban warming.

However, in the results of the Basic Regression model based on complete regression without considering interaction effects (Table 6), the partial regression coefficient for floor area ratio (FAR) is −4.583, and that for road density (RD) is −0.157, suggesting a negative relationship between these variables and urban warming. Conversely, the partial regression coefficients for the landscape shape index (LSI) and aggregation index (CLUMPY) are 35.879 and 0.342, respectively—implying a positive correlation between these metrics and urban temperature rise.

Table 6.

Results of the Basic MLR Models Without Considering Interaction Effects.

These observed relationships between the independent and dependent variables, as reported in Table 6, clearly deviate from established physical or biophysical understandings. In fact, 10 out of the 12 predictor variables in this model have VIFs exceeding 10.

This strongly indicates the presence of severe multicollinearity among the predictor variables. Such multicollinearity can obscure or distort the individual contribution of a given predictor to the LST, as its effect may be masked by stronger correlations between the LST and other variables. Consequently, the resulting partial regression coefficients may appear counterintuitive or inconsistent with theoretical expectations.

Therefore, the performance of the basic model based on complete regression is evidently inferior to that of the other two basic regression models.

4.2. Analysis of the Pathways Through Which the 12 Main Effects Influence LST

Table 7 presents the partial regression coefficients of the basic PLSR models. Given the substantial variation in measurement units (e.g., percentages, meters, square meters) among the 12 indicators, the raw (unstandardized) partial regression coefficients cannot directly reflect the relative strength of each predictor’s influence on the response variable, LST. To facilitate meaningful comparisons, all coefficients were standardized (see Column 4 of Table 7), and the model results were interpreted based on the standardized coefficients.

Table 7.

Partial Regression Coefficients of Each Indicator in the Basic PLSR Models.

A comparison of the standardized and unstandardized coefficients reveals that among the hardscape indicators, three variables—building coverage (Building: 2.204 → 0.115), other impervious surface area (OtherIS: 3.351 → 0.076), and road density (RD: 0.0436 → 0.093)—all exert a positive contribution to increased LST. Holding other variables constant, a one-standard-deviation increase in Building, OtherIS, and RD corresponds to increases of 0.115, 0.076, and 0.093 standard deviations in LST, respectively. Notably, the relative importance ranking of these indicators changes after standardization: while OtherIS exhibited the strongest effect in unstandardized form (3.351 > 2.204), after standardization Building surpasses OtherIS in importance (0.115 > 0.076). This result highlights how differences in measurement scale can distort coefficient estimates, while also emphasizing the dominant role of artificial surface spatial agglomeration in exacerbating urban thermal environments [60,61].

In contrast, the other three hardscape indicators—mean building height (MBH: −0.004), floor area ratio (FAR: −0.007), and mean building distance (MBD: −0.017)—have negative standardized coefficients close to zero, indicating relatively weak cooling effects compared to the stronger warming effects of Building, OtherIS, and RD. This may relate to the shading effects of built structures or improved airflow pathways, suggesting that appropriate adjustments to urban form and layout may help mitigate urban heat accumulation [62,63].

Softscape indicators exhibit similar discrepancies due to unit differences. For instance, the landscape shape index (LSI) shows a standardized coefficient of −0.043 (from an unstandardized −1.783), and CLUMPY’s coefficient changes from −0.284 to −0.092. Of particular note is the consistent dominance of UGI, whose coefficient remains the highest before and after standardization (−2.555 → −0.148), confirming its strong cooling effect and highlighting its irreplaceable role in regulating urban thermal conditions. This finding aligns with ecological theories on cooling via evapotranspiration and the low albedo of vegetated surfaces, further validating UGI’s critical role in urban climate regulation [64,65,66].

After removing the influence of differing measurement scales, the remaining five softscape indicators form two distinct clusters in terms of relative importance. Patch density (PD: −0.025) and LSI (−0.043) display similar, relatively low standardized effects, whereas CLUMPY (−0.092), largest patch index (LPI: −0.092), and COHESION (−0.090) demonstrate consistently stronger negative associations with LST. These results indicate that while all natural landscape elements contribute to mitigating urban heat island effects, their impact intensities vary substantially. This suggests that urban planning should not only prioritize increasing the proportion of UGI, but also emphasize enhancing the spatial connectivity and aggregation of green infrastructure [67,68,69].

4.3. Further Analysis of the Mechanism Behind Thermal Environment Anomalies at the Interaction Effect Scale

The results of the enhanced PLSR model incorporating interaction effects (Table 8) are consistent with those of the basic model (Table 7) [70,71]. However, by introducing interaction terms, this model further quantifies the relative contributions of both main effects and interaction effects of the explanatory variables to LST. The results show that the standardized partial regression coefficients of Interaction1 and Interaction2 are −0.094 and −0.061, respectively, both significantly negatively correlated with LST. This may be attributed to the fact that both interaction terms include the urban green infrastructure (UGI) variable. The interaction between UGI and other landscape pattern indicators or impervious surfaces exerts varying effects on urban warming, reflecting the integrated impact of green space on the urban thermal environment under different spatial structures.

Table 8.

Partial Regression Coefficients of Each Indicator in the Enhanced PLSR Models.

For example, Interaction 1 illustrates the synergies between UGI’s area proportion, largest patch index (LPI), aggregation index (CLUMPY), and connectivity (COHESION). It shows that as the interaction traits of UGI increase, so does its cooling effect in mitigating the UHI effect. This cooling effect results from a combination of UGI’s evapotranspiration cooling, shading effects, and the forms of ecological ventilation corridors [72]. Similarly, Interaction2, which captures the interaction between UGI and patch density (PD) as well as landscape shape index (LSI), may indicate that green infrastructure has a stronger regulatory impact on urban thermal environments when characterized by moderate patch density and more complex shapes [32].

A clear contrast can be observed when comparing Interaction3, which excludes UGI, with Interaction4, which includes UGI. The standardized coefficient of Interaction3 is 0.011 and weakly positively correlated with LST, suggesting that interactions among purely hardscape variables—such as combinations of building-related indicators and road density—tend to exacerbate the urban heat island effect [73]. In contrast, Interaction4 yields a coefficient of −0.096, indicating a notable cooling effect and further reinforcing UGI’s critical role in modulating the thermal impacts of land use.

The mechanisms underlying this contrast can be explained by urban microclimate principles [74]. In scenarios represented by Interaction3—particularly in densely developed areas lacking green infrastructure, where building concentration, high road density, high floor area ratio, and tall average building height are prevalent—the combination of low surface albedo, high heat retention, and insufficient ecological cooling can lead to thermal accumulation [75,76]. However, when urban development is spatially coupled with UGI, as represented by Interaction4, the cooling effects of green patches can reduce the temperature of surrounding impervious surfaces through energy exchange processes, thereby achieving a positive regulatory effect on the thermal environment [77].

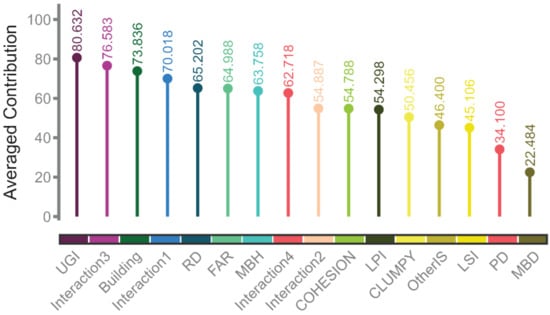

Figure 3 presents the quantitative results of the SVR-enhanced model, illustrating the contribution levels of 12 main effects and 4 interaction effects to LST. Among them, the top five contributing land development pattern indicators are: UGI (80.632), Interaction3 (Building × RD × FAR × MBH) (76.583), Building (73.836), Interaction1 (UGI × CLUMPY × LPI × COHESION) (70.018), and RD (65.202).

Figure 3.

Average Contribution of Land Development Pattern Indicators in the SVR-Enhanced Model.

Further analysis indicates that among the top five indicators, the main hardscape variables—Building and RD—account for 40% of the contributions, and Interaction3, which involves only hardscape elements, ranks second. This suggests that impervious surfaces such as buildings and roads are core drivers of abnormal urban heat intensification and thus should be prioritized for intervention in urban heat island (UHI) mitigation strategies [78,79]. Notably, UGI ranks first in average contribution, underscoring that, beyond optimizing the spatial configuration of built-up areas, strengthening UGI development is a critical pathway to alleviating UHI effects [80].

Moreover, Interaction1, which captures the interaction between UGI and key landscape pattern metrics (CLUMPY, LPI, and COHESION), ranks fourth. Its high contribution validates that developing green space systems characterized by strong connectivity, high aggregation, and prominent patch features can significantly improve the thermal environment. This provides a concrete and actionable direction for landscape-based UHI mitigation [81].

However, as noted in earlier discussions, while the SVR-enhanced model effectively quantifies the average strength of each variable’s influence on LST, it cannot determine the direction (positive or negative) of those relationships. This limitation highlights the inadequacy of relying on a single model to fully unravel the complex mechanisms through which urban land development patterns impact the thermal environment [82]. In light of this, the study further compares the quantitative results from the SVR-enhanced model with those of the PLSR-enhanced model, as detailed below.

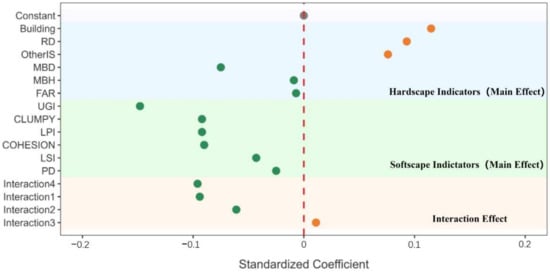

The PLSR-enhanced model, as illustrated in Figure 4, clearly demonstrates both positive and negative correlations between each indicator and LST through standardized partial regression coefficients. Among these indicators, UGI shows the strongest negative correlation with LST at −0.101, followed closely by Interaction4 at −0.096 and Interaction1 at −0.094. These negative correlations suggest that UGI and its related interactions—particularly Interaction1, which integrates UGI with CLUMPY, LPI, and COHESION—have significant cooling effects. Conversely, the indicators with positive correlations with the LST, such as Building (0.083), RD (0.0694), and OtherIS (0.0542), indicate that these hardscape elements are the main contributors to increasing urban warming. This result is consistent with the SVR model’s assessment of average importance, where Building and RD rank third and fifth, respectively.

Figure 4.

PLSR Enhanced Model’s Standardized Partial Regression Coefficients for Urban Land Development Pattern Indicators.Note:In this figure, the green dots represent positive values, and the orange dots represent negative values.

Although the analyses presented in Table 4 and Table 5 indicate that the enhanced SVR models outperform the enhanced PLSR models in terms of explanatory power (R2 = 0.971) and prediction accuracy (RMSE = 0.537) compared to the PLSR model (R2 = 0.767, RMSE = 1.337), both models provide critical insights from different analytical perspectives. The SVR-enhanced model excels at capturing the intensity of interactions among factors in complex nonlinear relationships, allowing us to identify which combinations of variables carry greater weight in their overall influence. In contrast, the enhanced PLSR models, with their strength in linear interpretation, clarify whether a given factor contributes to temperature increases or reductions. The SVR models, therefore, serve as a powerful tool for quantitatively deciphering nonlinear interactions, while the PLSR model supports qualitative judgment through its clarity in indicating directional influence.

Therefore, in exploring the nonlinear relationships between land development patterns and the thermal environment in megacities, the SVR- and PLSR-enhanced models each offer irreplaceable strengths. Their combined use enables a comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the complex influence mechanisms from both quantitative and qualitative, as well as nonlinear and linear perspectives. This integrated modeling strategy provides a robust theoretical foundation and clear direction for formulating scientifically sound and effective urban heat mitigation policies, ultimately supporting the development of a more livable urban thermal environment.

4.4. Implications to Practice in Land Use Management and UHI Mitigation

This study addressed the influential factors of urban land development patterns and their roles in negatively or positively contributing to the urban thermal environment. Our findings generally align with those of similar research [61,83,84]. However, our work strengthened the insightful analysis of the interactive effects among these influential factors, which make up a high-dimensional dataset used in this study. We quantitatively assessed the relative importance of both the main and interaction effects of the models on the thermal environment. We found that, alongside the main effect of these influential factors, the interactions among them play a significant role in UHI mitigation.

During the past three decades, downtown Shanghai has rapidly expanded its spatial domain at the loss of semi-natural landscapes, e.g., arable land and small water bodies at the urban fringe.

Recent urban land development has focused on creating large UGI patches within downtown Shanghai. However, a deficiency of ecological land, including green spaces and water bodies, remains a significant concern in unbalanced land development patterns and the UHI effect. Considering the drastic competition pressure of land development and very high economic costs, simply increasing the availability of ecological land by reducing construction areas presents significant challenges. Thus, substantially improving the UGI’s spatial connectivity and aggregation, particularly at the city core with dense buildings and high road density, should be given more priority. Based on our findings, we recommend the following actionable takeaways: (1) increasing the UGI’s share within the urban landscape; (2) improving the UGI’s spatial configuration, e.g., increasing LPI, CLUMPY, and COHESION and strengthening Interaction1−UGI × CLUMPY × LPI × COHESION; and (3) optimizing the spatial arrangement of the UGI and adjacent buildings, e.g., strengthening Interaction4−Building × RD × FAR × MBH × UGI.

To achieve these goals, we propose that recent urban renewal planning initiatives focus on enhancing the spatial connectivity of UGI without fundamentally altering the established urban spatial form and land structure. This task can be accomplished through strategies such as vertical greening, the establishment of small parks, the creation of blue-green spaces, and the implementation of green corridors. These methods aim to mitigate the fragmented characteristics of UGI within urban environments. For medium- and long-term urban renewal strategies, a comprehensive adjustment of land use patterns is imperative. This initiative entails the relocation of numerous densely developed, low-rise residential areas, which should be reconstructed as medium- to high-density buildings. By increasing the floor area ratio and modifying building spacing, it becomes possible to enhance the UGI’s area proportion and improve the effectiveness of urban ventilation corridors. Furthermore, the planning of ecological transportation corridors, characterized by tree-lined avenues, should be prioritized to foster a more favorable microclimate throughout the urban landscape. This approach can be replicated in neighboring cities within the Yangtze River basin and other cities located at a similar latitude, which have a similar local climate system.

4.5. Limitations and Future Prospects

This study has several apparent limitations. First, we primarily relied on the 30 m Landsat-8 LST datasets to represent the overall urban thermal environment. However, these LST datasets only capture daytime thermal infrared signals from the instantaneous field of view (IFOV). Thus, our results fail to capture diurnal cycles and lack the precision needed for characterizing detailed 3-D thermal profiles at the street level. Second, due to the lack of stereoscopic instruments for precise mapping, we only used the UGI’s two-dimensional traits to explore the UGI’s role in regulating the thermal environment. Therefore, we ignored the influence of the tree canopy’s vertical traits on the fine-scale thermal environment. Third, the model selection is limited to MLR, PLSR, and SVR. We did not employ other machine learning methods, such as random forests, extreme gradient boost, and deep-learning methods that utilize neural networks. Additionally, our modeling framework neglects the spatial and non-stationary models, such as the geographically weighted regression or geographically weighted random forests regression. These models may demonstrate superior performance in handling high-dimensional datasets with more competing predictive accuracy.

To tackle these challenges, we argue that future research should incorporate a UAV-thermal platform, Internet-of-Things-based thermal sensors, and thermally enhanced LST products derived from Landsat-8 TIRS data [33]. This integration will enable the production of within-daily LST series data. Additionally, it is essential to combine precise 3D data of vegetation traits and building geometry obtained from UAV-LiDAR platforms, along with information on tree or shrub shading and building shadows. These approaches will deepen our understanding of how vegetation and building spatial configurations contribute to physical cooling. By employing the proposed modeling framework, we can effectively examine the intricate relationships between urban land development patterns and the urban thermal environment at a fine scale. Additionally, future research should expand to more sampling sites to collect adequate data for validation with the numerical simulation outputs. This will ensure that the findings from out-of-sample inferences are more scientifically robust.

5. Conclusions

Taking downtown Shanghai as a case, this study quantitatively examines the complex relationships between influential factors of urban land development patterns and urban thermal environment indicated by the LSTs. We adopted MLR, PLSR, and SVR models, including their basic and enhanced models, to examine the abovementioned complex relationships. We then compared their model performance to determine which models had better interpretative power. The conclusions were summarized as follows.

(1) According to thermal physical traits, impervious surfaces and UGI are two contrasting contributors to variations in the urban thermal environment. Overall, metrics like Building, OtherIS, and road density (RD) are the main contributors to increasing the LSTs. They account for about 40% of the variance of the LSTs. Meanwhile, UGI is the strongest cooling factor. Its effectiveness in cooling increases when UGI exists in large, connected, and aggregated patches. In contrast, its fragmented patches are less effective.

(2) UGI cooling relies on composition, configuration, and spatial arrangement rather than its area proportion within the landscape. The basic and enhanced PLSR and SVR models outperformed the basic and enhanced MLR models in quantifying the relative importance of influential factors of urban land development patterns in the variance of the LSTs. In particular, when considering four interaction terms, both enhanced PLSR and SVR models remarkably increased their mean predictive power. These findings verified the importance of the interaction terms. Noteworthily, for urban settings with high floor area ratio and high road density but lacking adjacent UGI (Interaction-3), it was inclined to produce excess heat and thus increase the LSTs. Conversely, similar urban designs paired with spatially aggregated and contiguous UGI patches (Interaction-4) can lead to neutral or even reduced LST anomalies.

(3) Limitations such as a 30 m resolution for LST data, the lack of 3-D canopy data, and the focus on a single metropolitan area suggest the need for future research utilizing UAV-LiDAR technology, numerical simulation, and validation across multiple cities. Nevertheless, the SVR-PLSR models may serve as a useful approach to quickly assess urban land development patterns and related thermal health risks under different UGI conditions. This approach enables planners to move beyond merely increasing the planar metrics of UGI to implementing optimal configurations, settings, and combinations. It can help densely populated megacities adapt to a warmer future.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.-R.Y. and H.Z.; Methodology, H.-R.Y. and H.Z.; Software, H.-R.Y.; Data curation, H.-R.Y.; Formal analysis, H.-R.Y.; Resources, H.-R.Y., Y.-H.L. and H.Z.; Supervision, W.-J.W. and H.Z.; Validation, H.-R.Y.; Visualization, H.-R.Y. and H.Z.; Writing—original draft, H.-R.Y.; Writing—review and editing, H.-R.Y., H.Z. and A.-L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are not publicly available due to commercial confidentiality and licensing restrictions that prevent the disclosure of architectural planning layouts and their derivative data.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Ai-Lian Zhao was employed by East China Electric Power Design Institute (ECEPDI), China Power Engineering Consulting Group. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Basic information of 39 sampling sites.

Table A1.

Basic information of 39 sampling sites.

| Name | General Description |

|---|---|

| Fengxiang park (Area: 671.19 ha) | It is a mediumly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Fengxiang Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 27.22% of total land use shares. |

| Gucun Park (Area: 921.85 ha) | It is a slightly to mediumely urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Gucun Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 27.01% of total land use shares. |

| Paotaiwan Park (Area: 331.34 ha) | It is a slightly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Paotaiwan Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 57.30% of total land use shares. |

| Binjiang Forest Park (Area: 856.555 ha) | It is a slightly urbanized area at the Huangpu River and the Yangtze River intersection. Binjiang Forest Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 52.64% of total land use shares. |

| New Jiangwan (Area: 1006.92 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Vegetated land of Fudan University Jiangwan campus at Songhu road, New Jiangwan Park, Jiangwan Country Park, and New Jiangwan Ecological Conservation Park constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 20.22% of total land use shares. |

| FDU-SUFE (Area:350.91 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Vegetated land of Fudan University (FDU) campus at Handan Road, Shanghai University of Finance and Economics (SUFE) campus at Guoding Road, and Shanghai Pulmonary Hospital constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 6.09% of total land use shares. |

| SUS-SMMU (Area: 396.07 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Vegetated land of the Shanghai University of Sport (SUS), Second Military Medical University (SMMU), Changhai Hospital, and Jiangwan Stadium constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 4.13% of total land use shares. |

| Gongqing Forest Park (Area: 450.44 ha) | It is a slightly urbanized area featured with low-rises. Gongqing Forest Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 42.19% of total land use shares. |

| Senlan Park (Area:740.07 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Senlan Park, Senlan Sports Park, Pudong Peony Gard, and Senlan Oasis Park constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 21.70% of total land use shares. |

| Gaodong Park (Area: 1094.69 ha) | It is a slightly to mediumly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Gaodong Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 22.49% of total land use shares. |

| Lingshi Park-SHU (Area: 551.15 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Vegetated land of the Lingshi Park, Shang University (SHU) campus at Yanchang Road, Zhabei Park, constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 8.32% of total land use shares. |

| Luxun Park-SHISU (Area: 290.57 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Vegetated land of the Shanghai International Studies University (SHISU) and Luxun Park constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 4.67% of total land use shares. |

| TJU-Peace Park (Area: 503.01ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low-, middle-, and high-rises. Vegetated land of the Tongji University (TJU) campus at Siping Road and Peace Park constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 5.79% of total land use shares. |

| Huangxing Park (Aarea:258.85 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Huangxing Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 11.31% of total land use shares. |

| Yangpu Park (Area: 192.23 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Yangpu Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 7.80% of total land use shares. |

| Fuxingdao Park-USST (Area: 301.58 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Fuxingdao Park and the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology (USST) comprise the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 24.80% of total land use shares. |

| Mengqing Yuan (Area: 153.35 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Mengqing Yuan constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 8.85% of total land use shares. |

| ECNU-Changfeng Park (Area: 37.83 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Vegetated land of the East China Normal University (ECNU) campus at north Zhongshan Road and Changfeng Park constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 12.46% of land use shares in this area. |

| Zhongshang Park-ECUPL (Area:208.23 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Zhongshang Park and the East China University of Political Science and Law (ECUPL) constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 10.48% of total land use shares. |

| UrbanCore (Area: 941.32 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area at the urban core featured with a mixture of low-, middle-, and high-rise. Several big parks such as People Park, Jing’an Park, Square Park, Huaihai Park, Taipingqiao Park, Fuxing Park, Yuyuan Garden, Gucheng Park, and Bund Park constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 7.40% of land use shares in this area. |

| Lujiazui (Area:237.77 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of middle- and high-rises. The Oriental Pearl Park and Lujiazui Central Park constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 24.50% of total land use shares. |

| ZOO-Xijiao Hotel (Area: 704.52 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. It is located in the neighborhood of the Hongqiao Airport and Hongqiao high-speed railway station. Vegetated land of Xijiao Hotel and the ZOO constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 19.71% of total land use shares. |

| Soong Ching-ling Museum (Area: 286.54 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Soong Ching-ling Museum and New Hongqiao Central Garden constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 7.06% of total land use shares. |

| SJTU-neighboring Parks (Area:533.94 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The impervious surfaces occupy 92.26% of total land use shares, of which the buildings’ share is 65.52%. Vegetated land of the Shanghai Jiaotong University (SJTU) campus at Huashan Road, Hengshan Park, Xujiahui Park, Fanyu Park, Huashan Park, and Xinguo Hotel constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 7.61% of total land use shares. |

| Minhang Sports Park (Area: 961.66 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Minhang Sports Park, Minhang Culture Park, and Li’an Park constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 17.36% of total land use shares. |

| Hongqiao Golf (Area:245.25 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Vegetated land of the Hongqiao Golf constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 10.22% of total land use shares. |

| Dream Park (Area: 216.76 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Dream Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 6.16% of total land use shares. |

| SHNU-Guiling Park (Area: 372.31 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Vegetated land of the Shanghai Normal University (SHNU) campus at Guilin Road, Kangjian Yuan, Guilin Park, and Shanghai Administration Institute constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 5.91% of total land use shares. |

| XJH Sports Park-LH Cemetery (Area: 382.61 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Xujiahui (XJH) Sports Park and Longhua (LH) Cemetery constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 2.67% of total land use shares. |

| Expo Culture Park (Area: 349.26 ha) | It is a mediumly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Expo Culture Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 26.24% of total land use shares. |

| Century Park (Area: 465.60 ha) | It is a mediumly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Century Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 23.34% of total land use shares. |

| Tangcheng Golf-Dongjiao Hotel (Area: 720.35 ha) | It is a mediumly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Vegetated land of the Tangcheng Golf and Dongjiao Hotel constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 25.70% of total land use shares. |

| Jinhai Park (Area: 520.70 ha) | It is a slightly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Jinhai Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 34.37% of total land use shares. |

| Shanghai Botanical Garden (Area: 371.73 ha) | It is a highly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Shanghai Botanical Garden constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 13.27% of total land use shares. |

| Qiantan Sport Park (Area:215.61 ha) | It is a slightly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. Qiantan Sports Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 40.75% of total land use shares. |

| Kangqiao Park (Area: 601.80 ha) | It is a slightly to mediumly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Kangqiao Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 27.17% of total land use shares. |

| Wujing Park (Area:424.45 ha) | It is a mediumly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Wujing Park, Huajing Park, and Huilongyuan Coliseum constitute the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 34.28% of total land use shares. |

| Pujiang County Park (Area:481.18 ha) | It is a slightly urbanized area with sparse low-rises on the urban periphery. The Pujiang County Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 64.20% of total land use shares. |

| Pujiang First Bay Park (Area:623.31 ha) | It is a slightly to mediumly urbanized area with a mixture of low- and middle-rises. The Pujiang First Bay Park constitutes the aggregation of UGS patches, accounting for 40.18% of total land use shares. |

Table A2.

Spearman correlation coefficient matrix of 12 influential factors.

Table A2.

Spearman correlation coefficient matrix of 12 influential factors.

| Building | OtherIS | UGI | MBH | FAR | MBD | RD | PD | LSI | CLUMPY | LPI | COHESION | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Building | 1.000 | |||||||||||

| OtherIS | 0.610 * | 1.000 | ||||||||||

| UGI | −0.920 ** | −0.090 | 1.000 | |||||||||

| MBH | 0.510 * | −0.210 | 0.540 * | 1.000 | ||||||||

| FAR | 0.520 * | −0.190 | 0.550 * | 0.970 ** | 1.000 | |||||||

| MBD | −0.290 | −0.090 | 0.410 * | −0.190 | −0.210 | 1.000 | ||||||

| RD | 0.830 ** | −0.020 | −0.860 ** | 0.560 * | 0.560 * | −0.270 | 1.000 | |||||

| PD | −0.130 | 0.070 | 0.190 | −0.430 * | −0.370 * | 0.180 | −0.190 | 1.000 | ||||

| LSI | −0.560 * | −0.080 | 0.580 | −0.010 | −0.040 | 0.100 | −0.490 * | −0.510 * | 1.000 | |||

| CLUMPY | −0.780 ** | −0.190 | 0.870 ** | −0.430 * | −0.450 * | 0.230 | −0.740 ** | −0.040 | 0.660 * | 1.000 | ||

| LPI | −0.780 ** | −0.190 | 0.870 ** | −0.430 * | −0.450 * | 0.230 | −0.740 ** | −0.040 | 0.660 * | 0.996 | 1.000 | |

| COHESION | −0.810 ** | −0.120 | 0.870 ** | −0.470 * | −0.480 * | 0.260 | −0.760 ** | 0.110 | 0.610 * | 0.930 ** | 0.930 ** | 1.000 |

Note: * and ** denote statistically significant at p = 0.05 and p = 0.01,respectively.

References

- Irfeey, A.M.M.; Chau, H.; Sumaiya, M.M.F.; Wai, C.Y.; Muttil, N.; Jamei, E. Sustainable mitigation strategies for urban heat island effects in urban areas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 10767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coutts, A.M.; Beringer, J.; Tapper, N.J. Impact of increasing urban density on local climate: Spatial and temporal variations in the surface energy balance in Melbourne, Australia. J. Appl. Meteorol. Clim. 2007, 46, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Liao, W.; Rigden, A.J.; Liu, X.; Wang, D.; Malyshev, S.; Shevliakova, E. Urban heat island: Aerodynamics or imperviousness? Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaau4299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, M.; Das, A.; Biswas, M.; Pereira, P. ‘greening the edges’—Role of peri-urban green spaces in mitigating local temperature in English Bazar Urban Agglomeration, India. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2025, 156, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharston, R.; Singh, M. Urban morphology, urban heat island (UHI) and building energy consumption: A critical review of methods and relationships among influential parameters. Build. Serv. Eng. Res. Technol. 2025, 46, 561–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piracha, A.; Chaudhary, M.T. Urban air pollution, urban heat island and human health: A review of the literature. Sustainability 2022, 14, 9234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellena, M.; Melis, G.; Zengarini, N.; Di Gangi, E.; Ricciardi, G.; Mercogliano, P.; Costa, G. Micro-scale UHI risk assessment on the heat-health nexus within cities by looking at socio-economic factors and built environment characteristics: The Turin case study (Italy). Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxon, J.; Ulm, F.J.; Pellenq, R.J.M. Urban heat island impact on state residential energy cost and CO2 emissions in the united states. Urban Clim. 2020, 31, 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, M.; Das, A. Dynamicity of carbon emission and its relationship with heat extreme and green spaces in a global south tropical mega-city region. Atmos. Pollut. Res. 2025, 16, 102484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharston, R.; Singh, M. The role of passive, active, and operational parameters in the relationship between urban heat island effect (UHI) and building energy consumption. Energy Build. 2024, 323, 114720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, K.; Zhang, J.; Cui, D.; Ma, Y.; Ye, Y.; He, X.; Yang, Z.; Cheng, M.; Zhang, Y. Multi-scale study of the synergy between human activities and climate change on urban heat islands in China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2025, 125, 106341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, K.; Khan, A.; Anand, P.; Sen, J. Understanding the synergy between heat waves and the built environment: A three-decade systematic review informing policies for mitigating urban heat island in cities. Sustain. Earth Rev. 2024, 7, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Miao, S.; Masson, V.; Wurtz, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, X.; Yan, C. The synergistic effects of urbanization and an extreme heatwave event on urban thermal environment in paris. Urban Clim. 2024, 53, 101785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garuma, G.F. How the interaction of heatwaves and urban heat islands amplify urban warming. Adv. Environ. Eng. Res. 2022, 3, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Ma, J.; Liu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Hu, Y.; Li, Y.; Yue, Y. Spatial-temporal change of land surface temperature across 285 cities in China: An urban-rural contrast perspective. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 635, 487–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, B. Differential urban-rural effects of population during urbanization and urban-rural development. Urban Rural Plan. 2018, 2, 34–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuang, W.; Liu, J.; Dong, J.; Chi, W.; Zhang, C. The rapid and massive urban and industrial land expansions in China between 1990 and 2010: A CLUD-based analysis of their trajectories, patterns, and drivers. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 145, 21–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, B.; Hu, K. A review of impacts of urbanization on extreme heat events. Prog. Geogr. 2015, 34, 1219–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Geng, S.; Ren, J.; Yang, J.; Guo, A.; Xi, J. Exploration of urban thermal environment based on local climate zone. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2022, 42, 2221–2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballester, J.; Quijal-Zamorano, M.; Méndez Turrubiates, R.F.; Pegenaute, F.; Herrmann, F.R.; Robine, J.M.; Basagaña, X.; Tonne, C.; Antó, J.M.; Achebak, H. Heat-related mortality in Europe during the summer of 2022. Nat. Med. 2023, 29, 1857–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, Z.; Zhang, H. A quantitative analysis of the complex response relationship between urban green infrastructure (UGI) structure/spatial pattern and urban thermal environment in Shanghai. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, N.; Kuttler, W.; Barlag, A. Counteracting urban climate change: Adaptation measures and their effect on thermal comfort. Theor. Appl. Clim. 2014, 115, 243–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, G.Y.; Li, H.Y.; Zhang, Q.T.; Chen, W.; Liang, X.J.; Li, X.Z. Effects of evapotranspiration on mitigation of urban temperature by vegetation and urban agriculture. J. Integr. Agric. 2013, 12, 1307–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Wang, K.; Ren, Y.; Li, M.; Ji, R.; Wu, X.; Yan, H.; Lin, T.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, X.; et al. 3D compact form as the key role in the cooling effect of greenspace landscape pattern. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 160, 111776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Shu, J. Urban renewal can mitigate urban heat islands. Geophys. Res. Lett. 2020, 47, e2019GL085948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Ren, Z.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, P.; Guo, Y.; Wang, W.; Bao, G. Efficient cooling of cities at global scale using urban green space to mitigate urban heat island effects in different climatic regions. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 74, 127635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Paschalis, A.; Mijic, A.; Meili, N.; Manoli, G.; van Reeuwijk, M.; Fatichi, S. A mechanistic assessment of urban heat island intensities and drivers across climates. Urban Clim. 2022, 44, 101215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziter, C.D.; Pedersen, E.J.; Kucharik, C.J.; Turner, M.G. Scale-dependent interactions between tree canopy cover and impervious surfaces reduce daytime urban heat during summer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2019, 116, 7575–7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Jørgensen, G.; Vejre, H. Strong contributions of local background climate to the cooling effect of urban green vegetation. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 6798. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gage, E.A.; Cooper, D.J. Relationships between landscape pattern metrics, vertical structure and surface urban heat island formation in a Colorado suburb. Urban Ecosyst. 2017, 20, 1229–1238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhou, W. Optimizing urban greenspace spatial pattern to mitigate urban heat island effects: Extending understanding from local to the city scale. Urban For. Urban Green. 2019, 41, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Yin, H.; James, P.; Hutyra, L.R.; He, H.S. Effects of spatial pattern of greenspace on urban cooling in a large metropolitan area of Eastern China. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2014, 128, 35–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Kang, M.; Guan, Z.; Zhou, R.; Zhao, A.; Wu, W.; Yang, H. Assessing the role of urban green infrastructure in mitigating summertime urban heat island (UHI) effect in metropolitan Shanghai, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 112, 105605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Bureau of Statistics. Shanghai Statistical Yearbook (2024). 2024; p. 2. Available online: https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/tjnj/20250331/9f8ec62cc2234485b0aa411b8d967c37.html (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Shanghai Bureau of Statistics. Shanghai Natural Geography. Available online: https://tjj.sh.gov.cn/zrdl/index.html (accessed on 26 July 2025).

- China Meteorological Administration. Historical Weather Data for Shanghai. 2024. Available online: https://www.weather.com.cn/weather40d/101020100.shtml (accessed on 2 July 2025).

- Jiménez Muñoz, J.C.; Sobrino, J.A. A generalized single-channel method for retrieving land surface temperature from remote sensing data. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos. 2003, 108, D22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Li, T.; Liu, Y.; Han, J.; Guo, Y. Understanding the contributions of land parcel features to intra-surface urban heat island intensity and magnitude: A study of downtown Shanghai, China. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 1353–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanghai Bureau of Statistics. Shanghai Statistical Communiqué on National Economic and Social Development 2025; Shanghai Bureau of Statistics: Shanghai, China, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Feng, Y.; Chen, L.; He, X. Sky view factor calculation based on baidu street view images and its application in urban heat island. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2021, 23, 1998–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGarigal, K.; Ene, E.; Cushman, S. FRAGSTATS 4 Tutorial. Available online: https://fragstats.org/index.php/tutorial (accessed on 11 June 2025).

- Geladi, P.; Kowalski, B.R. Partial least-squares regression: A tutorial. Anal. Chim. Acta 1986, 185, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wold, H. Nonlinear iterative partial least squares (NIPALS) modelling: Some current developments. In Multivariate Analysis–III; Krishnaiah, P.R., Ed.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1973; pp. 383–407. ISBN 978-0-12-426653-7. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, W.; Fu, Q.; Xu, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, L.; Zheng, S.; Pang, J.; Chen, J. Analysis key aroma compounds based on the aroma quality and infusion durability of jasmine tea. Food Chem. 2025, 473, 143018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, X.; Xie, D.; Song, H.; Ma, J.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, Y.; Huang, F. Estimation of chemical oxygen demand in different water systems by near-infrared spectroscopy. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2022, 243, 113964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Yue, W.; Chen, J. Examining carbon emission drivers in the digital economy era: Empirical insights from the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei urban agglomeration, China. Pol. J. Environ. Stud. 2024, 33, 3247–3262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saitta, L.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar]

- Vapnik, V. The Nature of Statistical Learning Theory; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Mathew, A.; Sreekumar, S.; Khandelwal, S.; Kumar, R. Prediction of land surface temperatures for surface urban heat island assessment over chandigarh city using support vector regression model. Sol. Energy 2019, 186, 404–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garzón, J.; Molina, I.; Velasco, J.; Calabia, A. A remote sensing approach for surface urban heat island modeling in a tropical colombian city using regression analysis and machine learning algorithms. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, R.C. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Mevik, B.; Wehrens, R. (Eds.) Introduction to the pls Package; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, D. E1071: Misc Functions of the Department of Statistics, Probability Theory Group (Formerly: E1071), TU Wien. 1.7-16 Ed.; TU Wien: Vienna, Austria, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, X.; Zhang, M. Applied Regression and Classification—Based on R; China Renmin University Press: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, R.; Xiao, X.; Xia, J.C. Contribution of urban functional zones to the spatial distribution of urban thermal environment. Build. Environ. 2022, 216, 109000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estoque, R.C.; Murayama, Y.; Myint, S.W. Effects of landscape composition and pattern on land surface temperature: An urban heat island study in the megacities of Southeast Asia. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 577, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manoli, G.; Fatichi, S.; Schläpfer, M.; Yu, K.; Crowther, T.W.; Meili, N.; Burlando, P.; Katul, G.G.; Bou-Zeid, E. Magnitude of urban heat islands largely explained by climate and population. Nature 2019, 573, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Piao, S.; Ciais, P.; Friedlingstein, P.; Ottle, C.; Breon, F.; Nan, H.; Zhou, L.; Myneni, R.B. Surface urban heat island across 419 global big cities. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masoudi, M.; Tan, P.Y. Multi-year comparison of the effects of spatial pattern of urban green spaces on urban land surface temperature. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2019, 184, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Li, Z.; Su, Y.; Zhao, Q.; He, X.; Wu, Z.; Gao, W.; Wu, Z. Impact of block morphology on urban thermal environment with the consideration of spatial heterogeneity. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 113, 105622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ding, N.; Yang, X. Spatial pattern impact of impervious surface density on urban heat island effect: A case study in Xuzhou, China. Land 2022, 11, 2135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, G. How to build a heat network to alleviate surface heat island effect? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 74, 103135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Liu, J.; Zhang, Y.; Hong, S.; Fu, W.; Wang, M.; Dong, J. Construction of a cold island network for the urban heat island effect mitigation. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 915, 169950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krsnik, G. Is zagreb green enough? Influence of urban green spaces on mitigation of urban heat island: A satellite-based study. Earth 2024, 5, 604–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cameron, R.W.F.; Blanuša, T.; Taylor, J.E.; Salisbury, A.; Halstead, A.J.; Henricot, B.; Thompson, K. The domestic garden—Its contribution to urban green infrastructure. Urban For. Urban Green. 2012, 11, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Budzik, G.; Sylla, M.; Kowalczyk, T. Understanding urban cooling of blue–green infrastructure: A review of spatial data and sustainable planning optimization methods for mitigating urban heat islands. Sustainability 2025, 17, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Cheng, X.; Hu, Y.; Corcoran, J. A landscape connectivity approach to mitigating the urban heat island effect. Landsc. Ecol. 2022, 37, 1707–1719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]