Abstract

Morro do Banco, a slum in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, is home to a community composed mainly of Brazilian and Venezuelan nationals, where littering is a persistent issue. This study investigates the causes of littering and examines the differences in perceptions and littering behaviours between residents, addressing a research gap in multicultural slums. A face-to-face survey was conducted with 150 residents, complemented by interviews with community members and professionals from urban cleaning and waste management services. Visual observations were also made. The results indicate that littering is primarily linked to a lack of containers for waste disposal and collection, as well as residents’ failure to dispose of waste at the designated times. There is a notable absence of awareness campaigns aimed at addressing the problem. While both communities recognise the littering issue, Venezuelan residents are less aware of public services and report observing lower levels of littering than Brazilian residents. Furthermore, Brazilians tend to place more responsibility on local authorities, while Venezuelans attribute responsibility to the central government. Venezuelans also express less support for oversight actions involving penalties compared to Brazilians. These findings highlight the need for targeted awareness campaigns and inclusive policies to effectively tackle littering in multicultural slums.

1. Introduction

Globally, waste management is a growing concern as the population continues to rise and consumption patterns change [1,2,3]. The environmental and health consequences associated with inadequate waste management are becoming increasingly urgent, particularly in developing countries such as Brazil [2,4], where waste management remains ineffective in several regions due to insufficient or malfunctioning infrastructure, limited financial and technical resources, inadequate planning, and citizens’ attitudes [1,5,6,7]. According to the 2022 Census [8], Brazil has already surpassed 203 million inhabitants, generating approximately 81.8 million tonnes of municipal waste, which is often dumped in open-air sites, discharged into the public sewage system, or incinerated [9,10].

Moreover, in Brazil, informal settlements known as favelas are common, where social inequalities are reflected in the physical organisation of space [9,11,12]. These areas are characterised by high urban density, low-income populations, and insufficient state interventions in key sectors such as sanitation, security, and public services [12,13]. For instance, in 2022, there were 12,348 slums in Brazil [8]. In the city of Rio de Janeiro, approximately 22% of the population (around 1,434,975 inhabitants) live in the 1074 slums [14]. Slums face challenges due to the limited space for temporary waste disposal and difficulties facing waste collection vehicles and equipment gaining access. These factors contribute to inefficient waste management, littering [13], and potentially the spread of diseases [15].

Specifically, litter can be defined as waste discarded in a disorganised manner [16]. Its physical composition varies [17], including plastics, paper, food waste, and its packaging, among others [18,19,20]. Several researchers have focused on the causes of littering behaviours [18]. These behaviours have been linked to sociodemographic or contextual factors, such as individuals’ age [21], gender, marital status, monthly household income, and religious beliefs [22], or even interpersonal relationships within families [23]. Other contributing factors include the lack of sufficient and conveniently located waste disposal facilities, the presence of appropriate waste management infrastructure [24], the pre-existence of litter in an area, a lack of awareness regarding regulations and punitive measures against littering [25], a low sense of belonging to the community [22], and tendencies to imitate the behaviour and social norms of peers [26].

By way of a broader yet integrated approach, the variety of factors influencing waste management are well explained and articulated in the “Behaviour Change Wheel” model, developed by Michie et al. [27]. This model highlights various systemic factors that can influence waste management behaviour, including public policies, infrastructure, communication and awareness campaigns, and cultural and social norms, among others. These factors interact in complex ways and can vary across different communities and contexts.

Specifically, the issue of multiculturalism, associated with immigration, has been identified as one of the causes of environmental problems, increasing population growth, resource consumption, and waste disposal [28]. Kim and Moon [29] found that the behaviour of immigrants may differ from that of native individuals, meaning that each group is likely to have had distinct learning experiences that shape their actions. Importantly, other authors do not associate immigration with environmental damage in host countries, nor do they report differences between immigrants and natives concerning environmental behaviours. For example, Hunter [30] concluded that both immigrants and native residents in the United States exhibited similar attitudes and behaviours towards environmental resources. Additionally, immigrants have been shown to contribute to the implementation of environmentally positive practices, such as waste recycling or working towards more sustainable sources of energy [31]. Acculturation is also a phenomenon that should be considered, particularly in terms of how individuals adjust to a new culture and manage the challenges they may face [32].

In Brazil, migrants and refugees of various nationalities are present, particularly in the peripheral areas of major metropolitan regions, such as favelas. Since 2014, Brazil has received many Venezuelan migrants, with the numbers increasing each year. More than 800,000 Venezuelans have entered the country since 2017, fleeing the severe economic, social, and political crisis in Venezuela [33]. Although Brazil is not the primary destination for Venezuelan migrants, their choice to settle there can be attributed to its geographical position within the continent, the Brazilian government’s adoption of a legal framework to support refugees (guaranteeing rights to immigrants), and the economic crises affecting traditionally migrant-receiving regions such as North America and Europe [34]. Most Venezuelans entering Brazil settle in the northern region, particularly in the states of Amazonas and Roraima [8], and are later relocated across Brazil through Operação Acolhida, a government initiative supporting migratory movements [35].

Although a body of scientific literature on littering behaviours and its causes exists, research projects specifically addressing this issue in developing countries remain scarce. This was highlighted by Chaudhary et al. [36] in their systematic review of littering behaviours. Additionally, some authors, particularly Brazilian academics, have conducted studies on littering in Brazilian slums (e.g., Junkes et al. [37], Silva et al. [38], and Carijó [39]). However, their research did not focus on the multicultural aspect of communities, omitting how cultural and social dynamics between natives and immigrants might influence perceptions and behaviours related to littering. This gap justifies the research presented below, which studies the Morro do Banco slum in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, a community with a significant presence of Venezuelan immigrants and high littering levels. Understanding the causes of littering and associated behaviours is essential for the development of effective solutions to address it, particularly in the many slums in developing countries with multicultural communities.

2. Methods

2.1. Case Study

The city of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, receives a large number of immigrants, including Venezuelan citizens [40]. Most of the Venezuelans migrating to Rio de Janeiro settle in the Itanhangá neighbourhood, specifically in the Floresta da Barra da Tijuca community, known as Morro do Banco, where the Non-Governmental Organisation (NGO) SOS Children’s Villages is based.

Morro do Banco, was established in the Itanhangá area in the 1970s and, with seven other slums, forms the Complexo do Itanhangá or G8 [41]. Since 2002, the slum has had an ecological barrier intended to limit space for new constructions, although according to data from DataRio [14], the slum expanded from 149,859 m2 to 156,204 m2 between 1999 and 2019. Morro do Banco has paved streets, with over 80% of households being connected to the main water supply network, and nearly 100% having sewage and waste collection services.

Waste management and the cleaning of public spaces across Rio de Janeiro is carried out by the municipal cleaning company, Comlurb. In Morro do Banco, the sectors responsible for waste management include the Regional Superintendency of Barra—Jacarepaguá, the Support and Management Coordination, the Barra da Tijuca Management, and the Joá Services Division of Comlurb [42].

The Regional Superintendency of Barra—Jacarepaguá is responsible for participating in global decisions made by Comlurb’s management, in addition to coordinating urban cleaning, disease vector control, machinery and vehicle operations, and other special services. The Support and Management Coordination is responsible for planning operational activities, controlling and updating the data and information generated by the departments of the Regional Superintendency, allocating personnel, processing expenses, and managing all necessary logistics. The Barra da Tijuca Management plans, executes, and monitors waste collection and urban cleaning operations. Meanwhile, the Joá Services Division is responsible for cleaning the slums, beaches, markets, riverbanks, and other areas. The division also responds to the population’s suggestions and complaints, implements environmental education campaigns, and enforces warnings and penalties.

2.2. Research Approach

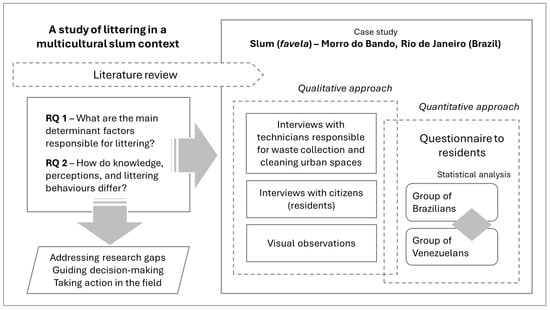

To meet the defined objective, this project was guided by two research questions (RQs) (Figure 1): the first concerns identifying the main factors responsible for the large amount of litter in the Morro do Banco slum (RQ1); and the second concerns examining whether statistically significant differences in the knowledge, perceptions, and littering behaviours between Brazilian and Venezuelan nationals exist (RQ2). Answering these questions allows for the development of a deeper understanding of the littering phenomenon in multicultural slum settings, as well as helping us to identify the most effective interventions to reduce littering.

Figure 1.

Research approach. Legend: RQ—research question.

To address the RQs, this study was structured into three phases using both qualitative and quantitative research methods (Figure 1). The first phase, a literature review, aimed to gather data on the characteristics and population dynamics of Morro do Banco, as well as the features of its waste management and urban cleaning services. The second consisted of interviews with technicians from Comlurb’s cleaning and waste collection services and key community actors, as well as visual observations to record the existing waste disposal facilities, assess the cleanliness of the streets, and observe the behaviour of the residents. The third phase involved administering a questionnaire to the slum’s residents.

2.3. Investigation Methods

2.3.1. Interviews

In order to collect precise data on waste management and street cleaning services, interviews with technicians and employees from the entity responsible for these services in Morro do Banco, Comlurb [42], were undertaken. A semi-structured interview guide was developed, including questions related to waste collection, public street cleaning, market cleaning, and the implementation of public awareness campaigns.

It was also considered important to gather the opinions of residents of the slum who hold relevant roles within the Morro do Banco community. For this purpose, a semi-structured interview guide was developed, including a set of questions aimed at understanding the interviewees’ opinions and perceptions regarding littering and the waste collection and urban cleaning services provided by Comlurb.

2.3.2. Visual Observations

To complement the information collected during the interviews, fieldwork was undertaken, aiming to observe waste disposal facilities, the cleanliness of public spaces, residents’ behaviour, and existing litter. The streets were selected randomly. On some days, the lead author made observations alone, but usually, she was accompanied by residents who had volunteered. This was because certain streets could be unsafe without the presence of a local resident. Observations were made between March and July 2022, totalling 30 visits to Morro do Banco.

2.3.3. Questionnaire to Residents

To better understand the knowledge, behaviours, perceptions, and opinions of the residents of Morro do Banco regarding litter, a questionnaire was designed and administered face-to-face between March and July of 2022. Before administering the questionnaire, a pre-test was conducted not only to refine the questionnaire but also to assess the relevance of the pre-selected questions and validate the chosen research assumptions.

The questionnaire’s closed-ended questions were organised into four groups of variables: (a) sociodemographic data; (b) knowledge about littering (c) behaviours related to littering; and (d) perceptions of the waste collection and public space cleaning services in the slum.

Although the objective was exploratory, the aim was to obtain the most representative sample possible of the community. Several points in the slum were selected, and the questionnaire was administered with the help of residents and volunteers from NGOs, who also helped with data collection, particularly in reaching Venezuelan citizens, as many were not fluent in Portuguese. The respondents were approached randomly along the selected routes.

To verify the existence of differences within the community and to study the influence of multicultural contexts on littering, the sample of residents was divided into two groups: Brazilians (G.BR) and Venezuelan immigrants (G.VE).

For the statistical data analysis, a one-way ANOVA test and Pearson’s chi-square test (χ2) were used to determine whether differences in the means or distributions of the groups were statistically significant. The significance level was set at 5% (p ≤ 0.05), and the tests were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics software (https://www.ibm.com/spss).

The Cramér’s V coefficient was used to measure the strength of the association between categorical variables. The Eta squared (η2) statistic was used to assess the strength of the association or effect size in analysis of variance (ANOVA). The interpretation of the results obtained for the correlation coefficients was considered, in general, to fall within the categories from medium to large [43]: small < 0.20; medium = 0.20 to 0.30; and large > 0.30.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Perception of Technicians and Residents Regarding Littering

To better understand the phenomenon of littering in the multicultural context of slums, it was possible to interview two operational technicians and one employee (responsible for street sweeping) from Comlurb, the company responsible for managing municipal waste in the Brazilian slum Morro do Banco. Here, there are no containers on public streets near residences, and one of the technicians suggested the frequent theft of these containers as a justification for the situation. At that time, the population had three 5 m3 multibenne containers intended for mixed waste, distributed randomly, and one 20 m3 compactor container, located at the entrance of the slum. The 5 m3 containers were collected daily by a roll-off vehicle and emptied into the compactor container, which, in turn, was filled every day. The waste was then transported to its final destination. Comlurb did not carry out any selective waste collection there.

Generally, the interviewees considered the equipment available and frequency of collections to be adequate. They identified the behaviour of the residents, who frequently disregarded the designated locations for waste disposal and the collection schedules, as the cause of improper disposal and the abandonment and accumulation of waste on the streets.

The street cleaning team consisted of at least two drivers and two street cleaners working daily. Due to the absence of containers and trash bins on the public streets, many residents chose to place their waste, either loose or in bags, in front of their houses, which was then collected by the street cleaners. This led one of the interviewees to claim that there was a door-to-door waste collection service in the community. Street and marketplace cleaning was carried out three times per week. One of the interviewees stated that there was no littering on the streets, while another acknowledged that the frequency of cleaning should be increased due to the community’s behaviour, indicating an awareness of the reality.

It was unclear whether the waste management operator regularly collaborated with the residents’ association to inform and raise awareness among residents about waste collection and public space cleaning, as the responses from the interviewees were contradictory. Complaints from the population about waste collection or street cleaning were perceived as rare due to a lack of knowledge about the appropriate channels for filing complaints.

The three interviewees agreed that there was a lack of information and awareness among the residents regarding proper waste disposal and littering, suggesting the implementation of awareness campaigns, lectures in schools, and joint actions with the residents’ association as essential measures to reduce improperly disposed of or abandoned waste, to improve hygiene conditions, and to facilitate the service they provide.

In addition to the Comlurb professionals, seven Brazilian residents of the slum were also interviewed, including local business representatives, school directors, NGO staff, and members of the residents’ association. Only one of these interviewees considered the number of containers and bins in Morro do Banco as sufficient. All seven highlighted the compacting container as an important waste disposal point. Only two interviewees considered the frequency of waste collection from the 5 m3 multibenne containers adequate, indicating contradictory perceptions. All seven respondents agreed that there is a large amount of abandoned waste on the streets. Most of the interviewees reported being unaware of the cleaning services occurring in the community or that they considered services insufficient, rarely occurring. Some stated that the streets were cleaned by the residents themselves, not by an external organisation.

The main problems concerning littering, from the perspective of residents, were the lack of containers and trash bins, the scarcity of street cleaners, the perception of infrequent waste collection, the presence of rats as disease vectors, and the lack of awareness, and the improper behaviour of the residents. Only one interviewee from this group mentioned that in the past, the residents’ association had carried out waste management awareness campaigns. Other participants referred to initiatives promoted by an NGO but emphasised the need for more.

3.2. Observations on Littering Gathered During Fieldwork

The 20 m3 compactor container, located at the entrance of the slum, was a widely recognised destination for waste disposal by residents. It was also observed that a vehicle was transporting 5 m3 multibenne containers and unloading their contents into this compactor. During the fieldwork, no employees from the waste management entity were observed cleaning the containers and trash bins or cleaning the streets.

Contrary to the information provided by the technicians interviewed, observations recorded a scarcity of trash bins and containers for waste disposal and an uneven distribution of them throughout the slum. Only four 50 L trash bins were observed, all located on the same street, and generally, they were overflowing with waste, covering the ground around them. Visual observation revealed that the physical composition of this waste was predominantly food scraps, bags, and plastic bottles, as also observed by Kachef and Chadwick [17], Rossi et al. [18], Verstegen et al. [20], and Tehan et al. [19]. The few 240 L waste containers available on the streets were concentrated on the access road to the slum. De Schueler et al. [13] and Junkes et al. [37] also reported a lack or insufficiency of waste disposal equipment in Brazilian slums. Additionally, occurrences of scattered waste abandoned on the ground in bags, at street corners, in squares, and near buildings were observed. In a large area designated for recreation and leisure, there were no waste containers, and a significant amount of construction and demolition waste was noted.

3.3. Residents’ Perception of Littering

3.3.1. Sociodemographic Profile of the Respondents

This component of the research was carried out through a questionnaire conducted with the residents of the Morro do Banco slum. The sociodemographic characteristics of the sample are recorded in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of the respondents.

A total of 150 respondents agreed to complete the questionnaire (See Appendix A), of which 95 (63.3%) were of Brazilian nationality and 55 (36.7%) were of Venezuelan nationality, composed of immigrants/refugees. The majority of the respondents were young adults, under 39 (76.0%), and female (62.4%). Regarding gender, the differences between the two groups were statistically significant (χ2 (2) = 12.596; p ≤ 0.002; V = 0.291), with 12.7% of the Venezuelan respondents selecting the “Other” option. Additionally, Junger et al. [44] recorded that the majority of refugee applicants in 2022 were between 25 and 39 years of age, which, when combined with those under 24 years, accounted for approximately 82.0% of the total applicants. Since 2015, the same author observed a growing number of women from the Global South (i.e., Haitians, Venezuelans, Cubans, and Paraguayans) in the refugee profile in Brazil.

While 77.1% of the respondents completed primary or secondary education, the differences between the two groups were statistically significant (χ2 (3) = 7.822; p ≤ 0.050; V = 0.230): compared to the Venezuelan residents, fewer Brazilian respondents had secondary education (38.3% vs. 50.0%) or higher education (10.6% vs. 18.5%). Regarding occupation, the differences between the two groups were not significant (χ2 (11) = 18.560; p ≤ 0.069), with high unemployment (around 38.9%). Many refugees face financial difficulties in meeting their basic needs, such as individual and family sustenance, often taking jobs that do not match their qualifications [45]. The two main occupations in both groups were domestic work (15.4% in total) and commerce, particularly in small shops, street sales, or markets (14.1% in total). Regarding family income, no statistically significant differences were found between the two groups (χ2 (3) = 3.493; p ≤ 0.322). The majority of respondents (67.9%, in total) had a monthly family income equivalent to one minimum wage (Brazilian context), which, at the time, corresponded to about 200 USD.

There were statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding housing type (χ2 (4) = 45.809; p ≤ 0.001; V = 0.558): while 52.1% of the Brazilian residents lived in their own homes, none of the Venezuelan residents did; the majority (96.2%) rented. Another statistically significant difference concerned length of residence in Morro do Banco, with 72.8% of the Brazilian respondents having lived in the slum for more than five years, while 52.7% of the Venezuelan group lived there for less than a year (χ2 (7) = 70.871; p ≤ 0.001; V = 0.694). This situation could be explained by the fact that there was an NGO located in the Itanhangá neighbourhood that hosted refugees, who could stay there for up to three months before being referred to other locations. Located within the same neighbourhood, the Morro do Banco slum was a common option.

When the respondents were asked how they felt about living in Morro do Banco slum, measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale with the extremes of “very bad” and “very well”, 31.7% stated they felt very well, 61.8% felt well, 5.7% felt bad, and only one Brazilian respondent mentioned feeling very bad. The average scale value for the Brazilian group was 3.26, and that of the Venezuelan group the 3.19. The difference was not statistically significant (F (1, 121) = 0.360; p ≤ 0.550).

3.3.2. Residents’ Knowledge of Littering

The residents of the Morro do Banco slum were asked about their knowledge regarding the public services available to the population, the types of waste that can be deposited in the containers, the problems that can be caused by littering, and waste collections where they live.

Regarding the public services available in the neighbourhood, the majority mentioned electricity (69.3%), piped water (64.7%), and waste collection (64.0%), but only 32.0% mentioned the existence of sewage treatment, which could be explained by the fact that it takes place outside the slum. The differences between the groups were not statistically significant only in the case of sewage treatment (χ2 (1) = 2.792; p ≤ 0.067). For other services, the group of Venezuelan residents (G.VE) consistently showed lesser knowledge compared to the group of Brazilian residents (G.BR) concerning the existence of electricity (G.BR 81.1% vs. G.VE 49.1%; χ2 (1) = 16.736; p ≤ 0.000; V = 0.334), piped water (G.BR 75.8% vs. G.VE 45.5%; χ2 (1) = 14.029; p ≤ 0.000; V = 0.306), and waste collection (G.BR 80.0% vs. G.VE 36.4%; χ2 (1) = 28.788; p ≤ 0.000; V = 0.438). This may have been because they predominantly lived in rented houses, in poorer living conditions, had a lesser sense of belonging, or possessed less knowledge, having lived in the slum for a shorter period of time.

When the respondents were asked whether they knew what type of waste could be placed in the waste containers, 44.4% stated that they did, while 55.6% were unsure or did not know. This aligns with the uncertainty perceived during the technicians’ interviews regarding the effectiveness of raising awareness among residents about waste collection and the cleaning of public spaces. The statistical difference between the two groups was not significant (χ2 (2) = 5.180; p ≤ 0.075), although G.BR showed a higher number of respondents who believed they knew (50.5% of G.BR vs. 33.3% of G.VE). The lower knowledge among recent immigrants about the proper disposal of different types of waste was also identified by Silva et al. [46] in interviews conducted with a group of 10 Brazilians living outside Brazil regarding their perception of waste disposal practices. The respondents stated that they did not know the proper way to manage waste.

Although many respondents affirmed knowledge of correct waste disposal procedures, during the complementary fieldwork a large amount of abandoned waste of various types was observed. Similar results were obtained by Carijó [39] in a survey conducted in the Morro da Babilônia slum (also in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil), where, despite all respondents claiming to dispose of waste in appropriate locations, a large amount of waste abandonment was observed during the visits to the community, revealing a discrepancy between questionnaire responses and the visible result of behaviours (litter on the ground).

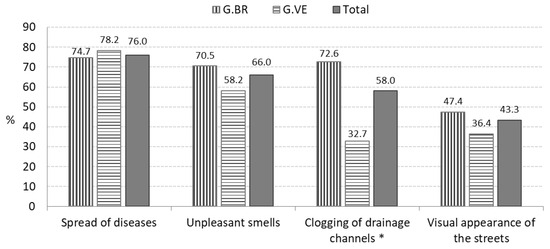

The respondents were asked about the problems caused by littering because knowledge of this can motivate more appropriate disposal behaviour. As the results in Figure 2 demonstrate, the majority associated littering with the spread of diseases (76.0%) and unpleasant odours (66.0%), which corresponds with the results obtained from the interviews with residents. However, statistically significant differences were noted regarding the clogging of drainage channels, recognised by 72.6% of G.BR and only 32.7% of G.VE (χ2 (1) = 22.770; p ≤ 0.000; V = 0.390).

Figure 2.

Opinions of the respondents from Morro do Banco on the problems associated with littering. Legend: G.BR—Group of Brazilian residents; G.VE—Group of Venezuelan residents. * Statistically significant differences between the groups (p ≤ 0.05).

The findings of Carijó’s [39] study of the Morro da Babilônia slum to the south of Rio de Janeiro indicate that the main problems the residents associated with inadequate waste management were the spread of diseases, unpleasant odours, and the clogging of drainage channels and gutters. This was echoed in Carvalho’s [47] survey of the residents of the Brazilian slum Rocinha.

On the other hand, the results showed that neither group had an adequate understanding of the waste collection services provided by Comlurb, with an overall result of 59.6% (56.0% for G.BR vs. 65.5% for G.VE; χ2 (3) = 2.186; p ≤ 0.535). The lack of knowledge about the services provided, as well as the locations and times of collection and the limited space for temporary waste storage inside homes, all contribute to its abandonment in the streets, as also noted in the interviews conducted with residents.

3.3.3. Residents’ Behaviour Related to Littering

The majority of respondents indicated that when they produced waste while walking down the street, they kept it until they found an appropriate bin or container in which to dispose of it (84.9%). A small proportion kept it or dropped it on the ground, depending on the situation (6.5%). Only 8.6% stated that they threw it directly on the ground (Table 2). Analysing the differences in the responses between the two groups, it was observed that a higher number of G.VE reported littering behaviours compared to G.BR, with statistically significant differences (χ2 (2) ≤ 10.406; p ≤ 0.005; V = 0.274).

Table 2.

Respondents’ behaviour regarding littering.

To gain a better understanding of the littering behaviour in Morro do Banco, when asked about their attitude if they were observed while discarding their waste on the ground, the groups showed statistically significant differences (χ2 (2) ≤ 15.255; p ≤ 0.001; V = 0.477). This question was only answered by 67 respondents (33 Brazilians and 34 Venezuelans). As shown in Table 2, the majority of respondents felt embarrassed, indicating the importance of social pressure/censure. However, while most G.BR stated that they felt ashamed and disposed of the waste in the nearest bin or container (81.8%), G.VE were almost equally divided between the three options, with only 35.3% of them acknowledging feeling embarrassed and subsequently disposing of the waste properly. Nonetheless, this finding does not correlate with the observations made during fieldwork regarding the large amounts of waste abandoned in the streets, which may also reflect a social desirability bias, understood as a tendency to overstate actions that align with social norms [48,49]. Interestingly, a study conducted some time ago by Grasmick et al. [50] in Oklahoma City, USA, interviewed the population before and after an anti-littering campaign, concluding that after the campaign, the percentage of people who would likely feel ashamed of improper waste disposal behaviour increased.

A total of 85 respondents (56.7% of the initial sample of 150 respondents), comprising 44 G.BR and 41 G.VE, answered the question aimed at understanding why residents throw waste directly on the ground. The statistical differences in the two groups’ responses were not significant (χ2 (4) = 5.057; p ≤ 0.281): 63.5% of them reaffirmed that they did not usually throw waste on the ground, while the others cited justifications such as insufficient trash bins or containers in their area (17.6%) or the containers always being full (3.5%). Only 8.2% justified their behaviour as a matter of convenience, considering it easier.

As observed in the Morro do Banco slum, Carijó [39] also found that most of the interviewees in the Morro da Babilônia slum (Rio de Janeiro) felt responsible for the cleanliness of public spaces. However, during her research, the author reported observing several residents discarding waste on the ground. Similarly, in the study by Junkes et al. [37], in the Comunidade Sombra dos Eucaliptos slum in Maceió (Brazil), most respondents admitted to discarding their waste directly into the sewage system or on abandoned lots, acknowledging some lack of awareness but also a lack of support from public authorities, who should be responsible for providing adequate facilities.

3.3.4. Residents’ Perceptions of the Services Provided

This section assesses the respondents’ perception of the services provided by the company responsible for waste collection and public space cleaning, specifically regarding the number of containers and trash bins available for waste disposal, the frequency of collections, and the quality of the public space cleaning service (Table 3).

Table 3.

Respondents’ perception of the services provided for waste management and public space cleaning.

Measured on a 4-point Likert-type scale (with extremes categorised between “there are none” and “there are many”), the majority of respondents in Morro do Banco considered that the containers were few in number (65.1%) or that none existed (13.7%). Only 21.2% considered that there were sufficient or many containers (7.5% and 13.7%, respectively). The average score was 2.21, with statistically significant differences between the groups (F(1, 144) = 7.122; p ≤ 0.008; ŋ2 = 0.047); G.BR provided a lower score than G.VE (2.08 vs. 2.44). These results correspond to the observed reality, where only three 5 m3 multibenne containers for waste collection and few 240 l containers were observed. According to Carijó [39], the presence of too few containers leads the population to abandon waste on the ground or beside the available containers.

In turn, most respondents perceived that the waste collection from the three 5 m3 multibenne containers in Morro do Banco was carried out daily (45.5%) or with some frequency (41.4%), although 13.1% stated that the waste was almost never or never collected. Analysis of the average values obtained for the 4-point Likert-type scale (with extremes categorised between “never collected” and “collected daily”) showed statistical differences between the groups (F(1, 143) = 3.908, p ≤ 0.05; ŋ2 = 0.027), with G.BR perceiving a higher frequency of collection than G.VE (3.39 vs. 3.13). Similar results were identified by Silva et al. [38] in a study conducted in the Complexo do Lins, a cluster of 14 communities located in the North Zone of Rio de Janeiro, where the majority of respondents considered the waste collection to be performed with weekly regularity (between one and three days a week), and only 6% stated there was no waste collection. The authors state that the collection service cannot meet the demand, causing unpleasant odours, the spread of disease vectors, and a poor quality of life in the region. Many of the interviewees expressed dissatisfaction, feeling a lack of support from the political authorities.

When asked about the streets of Morro do Banco, the majority of respondents (57.5%) experienced a large amount of abandoned waste in the streets, with this situation being validated in the fieldwork. However, the differences between the groups were relevant and statistically significant (χ2 (3) = 24.063; p ≤ 0.000: V = 0.406); litter in the streets was more frequently reported by G.BR than G.VE (71.7% vs. 33.3%).

When asked if the amount of litter in the streets bothered them, the statistical difference between the two groups was also significant (χ2 (3) = 24.615; p ≤ 0.000; V = 0.408). The majority of respondents stated that it had bothered them a lot (53.4%) or a little (31.1%). However, it is evident that the discomfort is felt more strongly by G.BR, while a higher proportion of G.VE reported that they were not bothered or did not care about this issue.

When participants were asked to evaluate the public space cleaning service (Table 3), measured on a 4-point Likert scale (ranging from “very bad” to “very good”), the opinion was split between those who rated the service as bad or very bad (47.8% for these two options combined) and those who rated it as good or very good (52.2% for these two options combined). The mean values for the evaluation scale were 2.45 for G.BR and 2.55 for G.VE. However, the differences between the two groups were not statistically significant (F(1, 136) = 0.503; p ≤ 0.479). These results seem contradictory, as one would expect respondents, given their perception of the large amount of litter on the streets and the discomfort they feel, to be more critical of the cleaning service.

The differences observed between the two groups may reveal not only a lesser understanding among immigrants of the political system and waste management in their neighbourhood but also a reduced perception of their ability or right to criticise the waste collection system due to their vulnerable position within society, as well as the influence of their experience and culture from their country of origin. Therefore, the topic of acculturation is relevant and should be explored in future research on littering.

In addition, the 150 respondents were asked about their reasons for littering on the streets, with the option to select multiple responses. The analysis revealed statistically significant differences between the groups for three options: “people do not want to put in the effort” (44.0% overall, 51.6% for G.BR and 30.9% for G.VE; χ2 (1) = 6.040; p ≤ 0.014; V = 0.201); “people do not care about the problems litter can cause” (30.7% overall, 36.8% for G.BR and 20.0% for G.VE; χ2 (1) = 4.647; p ≤ 0.031; V = 0.176); and “there are not many bins on the streets” (21.3% overall, 27.4% for G.BR and 10.9% for G.VE; χ2 (1) = 5.623; p ≤ 0.018; V = 0.194). On the other hand, there were no statistically significant differences between the groups for the following options: “people do not care about dirty streets” (30.7%, overall; χ2 (1) = 2.02; p ≤ 0.155); “the local government does not clean the streets regularly” (24.0%, overall; χ2 (1) = 2.78; p ≤ 0.096); and “the bins are always full of trash” (16.0%, overall; χ2 (1) = 2.19; p ≤ 0.139). According to Scotia (2022), there are several reasons that can lead people to abandon the waste they produce, including: convenience, a lack of concern (apathy), a lack of awareness about the problems caused by litter, a lack of understanding of waste separation rules, group behaviours, rebellion, or the absence of social pressure discouraging incorrect behaviours.

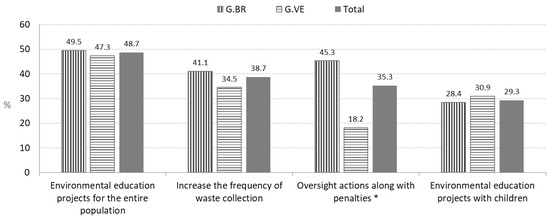

When asked to whom they attributed responsibility for the cleaning of public spaces, respondents collectively pointed to the municipality (Prefeitura) (56.0%), residents (38.0%), the government (28.0%), local associations (18.7%), and NGOs (11.3%). The order of responsibility allocation differed between groups (Figure 3), although the differences were only statistically significant for the municipality (70.5% for G.BR and 30.9% for G.VE; χ2 (1) = 22.188; p ≤ 0.000; V = 0.385) and the government (18.9% for G.BR and 43.6% for G.VE; χ2 (1) = 10.532; p ≤ 0.001; V = 0.265). These differences may have been due to the fact that most Venezuelan residents have lived in the slum for a relatively short period time so could be unfamiliar with the responsibilities of these bodies. Although respondents did not attribute much responsibility to local associations (e.g., residents or NGOs), collaborative governance involving various segments of society could have generated collective motivation and greater capacity for action, with better results when addressing littering, as highlighted by Abdulai et al. [51], when studying waste dynamics in the Wa region in Ghana.

Figure 3.

Measures to minimize the problem of litter. Legend: G.BR—Group of Brazilian residents; G.VE—Group of Venezuelan residents. * Statistically significant differences between the groups (p ≤ 0.05).

The respondents were asked about the measures that they believe should reduce the amount of littering in the streets, with the option to select multiple responses. The results shown in Figure 3 reveal that the two most prominent response options were environmental education projects for the entire population (48.7%, in total) and more frequent waste collection in the streets (38.7%, in total). The groups only showed statistically significant differences for oversight actions involving penalties, a measure considered more effective at addressing littering by G.BR than G.VE (χ2 (1) = 11.181; p ≤ 0.001: V = 0.273). Several studies on littering in developing countries have emphasised the importance of environmental education projects, training, and workshops, as these are essential for more effective anti-littering plans [52].

4. Conclusions

In slums, it is common to find large quantities of litter in public spaces. This study specifically addressed this issue in the Morro do Banco slum, located in Rio de Janeiro (Brazil), which has a significant presence of Venezuelan residents. The aim was to explore how the multicultural dynamics might influence perceptions and behaviours related to littering and to fill gaps in scientific knowledge.

The results highlight that the issue of littering in this context is complex, involving factors related to waste management services as well as behavioural aspects. From an operational perspective, as observed during fieldwork, these areas face significant challenges in terms of waste collection and the cleaning of public spaces, particularly due to the limited availability of waste disposal equipment and the inefficient distribution of the few available units. Additionally, the circulation of waste collection vehicles is hindered by the urban layout and topographical constraints, and the cleaning of public spaces is infrequent. Furthermore, as these areas are often socioeconomically disadvantaged, they tend to receive less consistent attention and investment from policymakers and waste management authorities compared to other urban areas. In fact, the respondents’ perception that public services were ineffective at waste collection and cleaning public areas may have generated a sense of irresponsibility among residents, leading them to abandon waste. Additionally, many residents did not respect the designated times and locations for waste collection and lacked awareness of local waste management services.

It was important to assess whether there were differences in the knowledge, perceptions, and littering behaviours between Brazilian and Venezuelan residents in the multicultural context of the Morro do Banco slum. The results indicated that overall, both groups showed a similar understanding of the littering problem, acknowledging the negative impacts associated with it. However, Venezuelan residents demonstrated less awareness of the public services available, likely due to living in the slum for a shorter time. Overall, it was found that Venezuelan residents detected less littering than the Brazilian community and were more tolerant of this phenomenon. Furthermore, when it comes to assigning responsibility for street cleaning, Brazilian residents attributed greater responsibility to local authorities (Prefeitura), while Venezuelan residents attributed greater responsibility to central authorities, namely, the government. The absence of effective awareness campaigns may have contributed to these results. It is noteworthy that when asked about measures to reduce the littering problem, Venezuelan residents were less likely to support enforcement actions combined with penalties than Brazilian residents.

In terms of limitations, this study faced challenges such as restricted access to some streets within the slum, the language barrier with the Venezuelan community, as well as difficulties communicating with the technicians responsible for waste management and public space cleaning services. Therefore, it is recommended that these factors be considered when conducting studies in similar contexts.

Based on field observations and the results obtained, several intervention strategies should be implemented to address the issue of littering in the context of a multicultural slum to reduce the differences found. These include developing awareness campaigns and environmental education that engage all residents, including workshops, lectures and practical activities to encourage the participation of everyone. Also, the government, local authorities, local associations, and NGOs must work together to engage with the community and tailor strategies that consider multicultural factors. This approach aims to enhance immigrant community involvement in waste management and litter reduction, addressing cultural differences where necessary, clarifying specific concerns, and implementing targeted actions to overcome identified challenges.

Regarding future research, studying slums where the immigrant community has been established for a longer period of time would be fruitful because in Morro do Banco, the Venezuelan community has been in the area for a relatively short period. In addition, the living conditions of immigrants prior to their arrival should be more carefully explored in future studies, particularly regarding waste management practices, to allow for meaningful comparisons. Finally, desirability bias regarding littering should be further explored, as well as the acculturation context, as it was not possible to address these topics in detail in the current research project.

Author Contributions

P.S., conceptualisation, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, and writing—review and editing; M.R., conceptualisation, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, and visualisation; A.A., formal analysis and writing—review and editing; G.M., conceptualisation, methodology, validation, formal analysis, resources, writing—original draft, writing—review and editing, supervision, and project administration. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is funded by national funds through FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P., within the framework of the UID/04292/MARE—Centro de Ciências do Mar e do Ambiente and the project LA/P/0069/2020 (https://doi.org/10.54499/LA/P/0069/2020) granted to the Associate Laboratory ARNET—Aquatic Research Network.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The Ethics Committee of NOVA School of Science and Technology does not consider formal ethical approval to be required in this case.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their sincere gratitude to those who participated in this study, particularly the interviewees and the residents of the Morro do Banco slum who took part in the questionnaire, as well as those who accompanied the fieldwork. Without their presence and support, many of the activities carried out during this research would not have been possible.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Questionnaire for residents of the Morro do Banco slum.

- A.

- Sociodemographic profileA1. What is your age?[ ] 18–24 [ ] 25–39 [ ] 40–59 [ ] 60 or overA2. What is your gender?[ ] Female [ ] Male [ ] OtherA3. What is your nationality?[ ] Brazilian [ ] VenezuelanA4. What is your level of education?[ ] No formal education [ ] Primary education [ ] Secondary education [ ] Higher educationA5. What is your current professional occupation?[ ] Student [ ] Unemployed [ ] Domestic work [ ] Retired [ ] Commerce/retail [ ] Industry/manufacturing [ ] Agriculture [ ] Construction [ ] Administration [ ] Healthcare [ ] Electrical work [ ] Other (please specify)A6. What is your monthly family income (Brazilian context)?[ ] Up to 1 minimum wage [ ] 1 to 3 minimum wages [ ] 3 to 6 minimum wages [ ] 6 to 9 minimum wages [ ] More than 9 minimum wagesA7. What type of housing do you live in?[ ] Owned [ ] Rented [ ] Provided by family/friends [ ] Granted/temporary [ ] Other (please specify)A8. How long have you lived in this slum?[ ] Less than 1 year [ ] 1 to 2 years [ ] 2 to 5 years [ ] 5 to 10 years [ ] 10 to 20 years [ ] 20 to 30 years [ ] 30 to 40 years [ ] More than 40 yearsA9. On a 4-point scale, how do you feel about living in the Morro do Banco slum?[1] Very bad [2] Bad [3] Well [4] Very well

- B.

- Residents’ knowledge of littering.B1. Which of the following services are available in your neighbourhood?[ ] Electricity [ ] Piped water [ ] Sewage treatment [ ] Waste collectionB2. Do you know what types of waste can be placed in the waste containers?[ ] Yes [ ] NoB3. What type of problems can littering cause?[ ] Spread of diseases [ ] Clogging of draimage channels [ ] Unpleasant odours [ ] Other (please specify)B4. Are you familiar with Comlurb’s household waste collection system?[ ] Yes, completely [ ] Yes, I know a little about it [ ] I do not know what it is for [ ] I am not familiar with it

- C.

- Residents’ behaviour related to litteringC1. When walking in the streets, how do you usually dispose of your waste?[ ] I always throw it on the ground, as usual [ ] I either keep it with me or throw it on the ground [ ] I always keep it with me until I find a bin or containerC2. If someone is watching you while you are throwing your waste on the ground, what would you do?[ ] I throw it on the ground because the street is already dirty [ ] I feel embarrassed and only throw it on the ground when I am alone [ ] I feel embarrassed and dispose of it in the nearest bin or containerC3. If you throw your waste on the ground, why do you usually act this way?[ ] It is easier [ ] The bins or containers near my house are always full [ ] There are not many bins or containers where I live [ ] I do not usually throw waste on the ground [ ] Other (please specify)

- D.

- Residents’ perceptions of the services providedD1. On a 4-point scale, how would you rate the availability of trash bins and containers in your area?[1] There are none [2] There are a few [3] There are enough [4] There are manyD2. On a 4-point scale, how would you evaluate the waste collection from the three waste containers in your community?[1] Never collected [2] Hardly ever collected [3] Collected occasionally [4] Collected dailyD3. How do you perceive the amount of litter on the streets in the area where you live?[ ] Little [ ] Some [ ] A lot [ ] Not important to meD4. How do you perceive the discomfort caused by litter on the streets in the area where you live?[ ] It is very bothersome [ ] It is somewhat bothersome [ ] It is not bothersome at all [ ] Not important to meD5. On a 4-point scale, how would you evaluate the street waste cleaning service?[1] Very bad [2] Bad [3] Good [4] Very goodD6. What do you think are the reasons for littering on the streets? (you may select multiple answers)[ ] People do not care about dirty streets [ ] The bins are always full of trash [ ] There are not many bins on the streets [ ] People do not want to put in the effort [ ] People do not care about the problems litter can cause [ ] The local government does not clean the streets regularlyD7. Who do you believe is responsible for the cleaning of public spaces?[ ] The government [ ] The municipality (Prefeitura) [ ] Local associations [ ] NGOs (Non-Governmental Organisations) [ ] ResidentsD8. What measures do you believe would help reduce the amount of littering on the streets? (you may select multiple answers)[ ] Environmental education projects for the entire population [ ] Environmental education projects with children [ ] Increase the frequency of waste collection [ ] Oversight actions along with penalties

References

- Iyamu, H.; Anda, M.; Ho, G. A review of municipal solid waste management in the BRIC and high-income countries: A thematic framework for low-income countries. Habitat Int. 2020, 95, 102097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mor, S.; Ravindra, K. Municipal solid waste landfills in lower- and middle-income countries: Environmental impacts, challenges and sustainable management practices. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2023, 174, 510–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Global Waste Management Outlook 2024: Beyond An Age of Waste. United Nations—United Nations Environment Programme. 2024. Available online: https://wedocs.unep.org/20.500.11822/44939 (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Fuss, M.; Vasconcelos, R.; Poganietz, W. Designing a framework for municipal solid waste management towards sustainability in emerging economy countries—An application to a case study in Belo Horizonte (Brazil). J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 178, 655–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruhn, N.; Viglioni, M.; Nunes, R.; Calegario, C. Recyclable waste in Brazilian municipalities: A spatial-temporal analysis before and after the national policy on solid waste. J. Clean. Prod. 2023, 421, 138503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, R.; Farahbakhsh, K. Systems approaches to integrated solid waste management in developing countries. Waste Manag. 2013, 33, 988–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, V.; Ismail, S.; Singh, P.; Singh, R. Urban solid waste management in the developing world with emphasis on India: Challenges and opportunities. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2015, 14, 317–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IBGE. Demographic Data (Census 2022). Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics. 2024. Available online: https://www.ibge.gov.br/ (accessed on 5 February 2025).

- Aparcana, S. Approaches to formalization of the informal waste sector into municipal solid waste management systems in low- and middle-income countries: Review of barriers and success factors. Waste Manag. 2017, 61, 593–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lino, F.; Ismail, K.; Castañeda-Ayarza, J. Municipal solid waste treatment in Brazil: A comprehensive review. Energy Nexus 2023, 11, 100232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azevedo, B.; Scavarda, L.; Caiado, R. Urban solid waste management in developing countries from the sustainable supply chain management perspective: A case study of Brazil’s largest slum. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 233, 1377–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comelli, T.; Anguelovski, I.; Chu, E. Socio-spatial legibility, discipline, and gentrification through favela upgrading in Rio de Janeiro. City 2018, 22, 633–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Schueler, A.; Kzure, H.; Racca, G. How are municipal waste in the slums of Rio de Janeiro? Urbe 2018, 10, 213–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DataRio. Open Data Portal of the City of Rio de Janeiro (Brazil). DataRio. 2025. Available online: https://www.data.rio/ (accessed on 14 January 2025).

- Juvakoski, A.; Rantanen, H.; Mulas, M.; Corona, F.; Vahala, R.; Varis, O.; Mellin, I. Evidence of waste management impacting severe diarrhea prevalence more than WASH: An exhaustive analysis with Brazilian municipal-level data. Water Res. 2023, 247, 120805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, A.; Polonsky, M.; McClaren, N. Littering behaviour: A systematic review. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 478–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kachef, R.; Chadwick, M. Litter impact index: A proposed weighting of litter items to inform sustainable packaging development and extended producer responsibility. J. Clean. Prod. 2025, 495, 145069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Wu, M.; Wolde, B.; Zerbe, K.; David, T.; Giudicelli, A.; Da Silva, R. Understanding the factors affecting the quantity and composition of street litter: Implication for management practices. Heliyon 2023, 9, e14245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tehan, R.; Jackson, L.; Jeffers, H.; Burns, T.; Monck, G. Litter and Social Practices. J. Litter Environ. Qual. 2017, 2, 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- Verstegen, A.; De bruyn, E.; Soers, F.; Van Renne, R.; De Greef, J.; Vanaenroyde, B.; Van Caneghem, J. Exploratory compositional analysis of street bin litter: Empirical study in a regional city in Belgium. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2023, 190, 106817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leijdekkers, S.; Marpaung, Y.; Meesters, M.; Naser, A.; Penninx, M.; Rookhuijzen, M.; Willems, M. Effective Interventions on Littering Behaviour of Youngsters. What Are the Ingredients? 2015. Available online: https://edepot.wur.nl/412199 (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Al-Khatib, I.; Arafat, H.; Daoud, R.; Shwahneh, H. Enhanced solid waste management by understanding the effects of gender, income, marital status, and religious convictions on attitudes and practices related to street littering in Nablus—Palestinian territory. Waste Manag. 2009, 29, 449–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangoni, R.; Jager, W. Social dynamics of littering and adaptive cleaning strategies explored using agent-based modelling. Jasss 2017, 20, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schenck, C.; Grobler, L.; Blaauw, D.; Nell, C. Reasons for littering: Social constructions from lower income communities in South Africa. S. Afr. J. Sci. 2022, 118, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoppe, T.; Franco-Garcia, L.; Bressers, H. Street litter reduction programs in the Netherlands: Reflections on the implementation of the Dutch litter reduction program for 2007–2009. Lessons from a public private partnership in environmental policy. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2013, 12, 1657–1668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scotia, D. Litter Behaviour Research Findings. 2022. Available online: https://divertns.ca/sites/default/files/researchreportsfiles/2022-03/Report_DivertNS_LitterBehaviourResearch_March2022.pdf (accessed on 10 January 2025).

- Michie, S.; Stralen, M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement. Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, R. Georgia 2006 Visible Liter Survey: A Baseline Survey of Roadside Litter. Keep America Beautiful and Georgia Department of Community Affairs. 2007. Available online: http://cummingutilities.com/2006_Georgia_Litter_Report__Final_.pdf (accessed on 6 December 2024).

- Kim, K.; Moon, S. Determinants of the pro-environmental behavior of korean immigrants in the U.S. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2012, 17, 99–123. [Google Scholar]

- Hunter, L. A comparison of the environmental attitudes, concern, and behaviors of native-born and foreign-born U.S. residents. Popul. Environ. 2000, 21, 565–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonatti, V. Taking out the garbage: Migrant women’s unseen environmental work. Eur. J. Women’s Stud. 2018, 25, 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romero, C.; Laroche, M.; Aurup, G.; Ferraz, S. Ethnicity and acculturation of environmental attitudes and behaviors: A cross-cultural study with Brazilians in Canada. J. Bus. Res. 2018, 82, 300–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IOM. Data on Migration in Brazil. International Organization for Migration (Brazil). 2024. Available online: https://brazil.iom.int/pt-br (accessed on 5 November 2024).

- Alves, T. Direitos Humanos e a Política Migratória Brasileira. In I Encontro Virtual do CONPEDI—Direito Internacional dos Humanos; CONPEDI: Florianópolis, Brazil, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Breitenbach, B. A Migração Venezuelana e o Papel do Brasil: A Operação Acolhida Como Resposta ao Fluxo Migratório. 2022. Available online: https://repositorio.animaeducacao.com.br/bitstreams/e3de8ad4-f931-49a6-a68b-e038f48430a3/download (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Chaudhary, A.; Polonsky, M.; McClaren, N. Social norms and littering—The role of personal responsibility and place attachment at a Pakistani beach. Glob. Environ. Change 2023, 82, 102725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junkes, J.; Pedrosa, A.; Vieira, D.; Galvão, V. Resíduos Gerados nas Favelas. Impactos Sobre o Direito à Moradia Adequada, o Ambiente e a Sociedade; Editora Unijuí: Ijuí, Brazil, 2020; Volume 45. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, V.; Souza, C.; Fernandes, J.; Duarte, J.; Santos, P. Conscientização e Coleta Seletiva no Complexo do Lins. In X Congresso Brasileiro de Gestão Ambiental; Instituto Brasileiro de Estudos Ambientais: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Carijó, R. Análise e Proposta de Uma Gestão Integrada de Resíduos Sólidos: O Estudo de Caso da Comunidade da Babilônia. Master’s Thesis, Mestrado em Planejamento Energético. Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2016. Available online: https://www.ppe.ufrj.br/images/publica%C3%A7%C3%B5es/mestrado/Renata_de_Sousa_Carij%C3%B3.pdf (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Charneski, M.; Villamar, M. Mais vulnerabilidades e menos direitos: Migração e pandemia na cidade do Rio de Janeiro a partir do olhar das organizações da sociedade civil. In Travessa-Revista do Migrante; CEM – Centro de Estudos Migratórios: São Paulo, Brazil, 2022; Volume 95. [Google Scholar]

- Oberg, L. Do Rio das Vitrines à Galeria dos Desconhecidos: Um Estudo em Psicologia Social Comunitária na Localidade de Muzema. Doctorate Thesis, Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comlurb. Companhia Municipal de Limpeza Urbana. Prefeitura do Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. 2024. Available online: https://comlurb.prefeitura.rio/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Hemphill, J.F. Interpreting the magnitudes of correlation coefficients. Am. Psychol. 2003, 58, 78–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junger, G.; Cavalcanti Oliveira, T.; Lemos, S. Refúgio em Números—2023. Observatório das Migrações Internacionais; Ministério da Justiça e Segurança Pública. Departamento das Migrações. Brasília, Brazil. Available online: https://portaldeimigracao.mj.gov.br/images/Obmigra_2020/OBMIGRA_2023/Ref%C3%BAgio_em_N%C3%BAmeros/Refugio_em_Numeros_-_final.pdf (accessed on 4 January 2025).

- Faria, J.; Ragnini, E.; Brüning, C. Deslocamento humano e reconhecimento social: Relações e condições de trabalho de refugiados e migrantes no Brasil. Refug. Or Displac. Pers. Work. Environ. 2021, 19, 278–291. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, A.; Braga, N.; Pinho, A.; Silva, A. Comportamento sustentável de brasileiros residentes no exterior: Investigação sobre o descarte de resíduos. Rev. Foco 2023, 16, e810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, M. A Favela da Rocinha e a Destinação Inadequada de lixo: Entendendo os Meandros da Questão. Master’s Thesis, Mestrado em Serviço Social. Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, 2016. Available online: https://sucupira-legado.capes.gov.br/sucupira/public/consultas/coleta/trabalhoConclusao/viewTrabalhoConclusao.jsf?popup=true&id_trabalho=4578086 (accessed on 17 January 2025).

- Zhu, O.; Greene, D.; Dolnicar, S. Should the risk of social desirability bias in survey studies be assessed at the level of each pro-environmental behaviour? Tour. Manag. 2024, 104, 104933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vilar, R.; Milfont, T.; Sibley, C. The role of social desirability responding in the longitudinal relations between intention and behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 70, 101457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasmick, H.; Bursik, R.; Kinsey, K. Shame and embarrassment as deterrents to noncompliance with the law: The case of an antilittering campaign. Environ. Behav. 1991, 23, 233–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulai, I.; Fuseini, M.; File, D. Making cities clean with collaborative governance of solid waste infrastructure in Ghana. Clean. Waste Syst. 2024, 8, 100150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanyanyiwa, V.I. Motivational Factors Influencing Littering In Harare’s Central Business District, Zimbabwe. J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2015, 20, 58–65. Available online: https://www.iosrjournals.org/iosr-jhss/papers/Vol20-issue2/Version-4/J020245865.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).