Abstract

Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG 14) was launched in 2015 to provide an overarching governance framework for long-term sustainable ocean development. This research paper analyzes the extent to which global and regional organizations are coherent with SDG 14 under the existing frameworks of international law. This research paper further assessed Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs) under the framework of the United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) and International Environmental Law (IEL) in the context of joint governance of ocean and fisheries as Large Marine Ecosystems (LMEs). According to its objectives, the research indicated that coherence across governing instruments should be increased for the governance of LMEs, leading to the development of a mechanism representing consistency with SDG 14. As a result, a mechanism that demonstrates the coherence of SDG 14 with Agenda—2030 is made, which indicates that, in order to govern fisheries and oceans as LMEs jointly, coherence among governing instruments must be increased. The conclusion followed SDG 14’s recommended actions, which are sly in line with UNCLOS and IEL, although the current initiatives of the regional organizations should be updated.

1. Introduction

A joint governance mechanism of oceans and fisheries has recently gained global attention and appeals for transformation under Sustainable Development Goal 14 (SDG 14) [1]. Such a call to transform the governance of the oceans was louder during the Conference of Parties (COP)27 (the decision of the COP27 is known as the Glasgow Pact) and became more expansive in scope [2]. The international agendas (SDG 14 and COP27) emphasized a need to redefine fisheries governance based on internationally agreed environmental conventions and treaties [3]. International Environmental Law (IEL) outlines the responsibility of States to cooperate in the governance of oceans, focuses on the conservation and sustainable use of marine resources, and aims to ensure that the fisheries are a source of sustainable livelihoods and economic growth [1].

Ocean as an ecosystem and fisheries as a significant resource were first recognized in the Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (Stockholm Declaration) [4]. During the establishment of pertinent environmental declarations and treaties/conventions, the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) was codified as the primary international law providing rules for the joint governance of oceans and fisheries [5]. In addition, the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (CMS) provides a framework for protecting migratory species (including fisheries) [6]. It establishes the responsibilities of States to ensure that these species are protected from harm. Moreover, the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) requires States to regulate the trade of certain (marine) species and to prohibit their exploitation [7].

While recognizing the limits of the abilities of the individual States to achieve development and the sustainable management of oceans and fisheries as large marine ecosystems (LMEs), the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) attempts to establish multilateral organizations for such purposes [1]. Concurrent with the applicable rules provided under international law, multilateral organizations have also established a series of legal instruments for joint governance of oceans and fisheries. Such instruments were developed with time after the significant progress in IEL through the establishment of the United Nations Declaration on Environment and Development (Rio Declaration) [8]. During the same time, many States approached the Global Environmental Facility (GEF) for assistance in the joint governance of ocean and fisheries [9].

Considering the international ‘fisheries’ as an insufficiently addressed issue and imprecisely regulated issue during the Earth Summit, the United Nations Convention on Straddling Fish Stocks and Highly Migratory Fish Stocks (UNFSA) was established as an implementing agreement for the governance of fisheries as an ecosystem [10]. Food and Agriculture Organization’s (FAO) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (CCRF) and the Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas (The Compliance Agreement) are significant developments that specify the obligations of States to keenly legislate on the international conservation and management rules relating to the fisheries [11,12,13,14]. Furthermore, the Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter, and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported, and Unregulated (IUU) Fishing (PSMA) is developed in extenso of the UNCLOS, UNFSA, CCRF, and Compliance Agreement to enable the local authorities of the port States to deny permission to entry into its port if they suspect that a particular vessel has engaged in IUU fishing [15].

Although there have been frequent advances in international law and the latest development in global policies for joint oceans and fisheries governance as LMEs, the marine environment is deteriorating, and life below water is diminishing. Existing global, regional, and even national approaches to ocean and fisheries governance are fragmented because they are inconsistent with IEL and UNCLOS regulations, overlapping policies, and conflicting governing bodies at all levels [1]. Most regional and national efforts focused primarily on resolving issues on a single sector-by-sector basis. Oceans and fisheries governance is handled with unreasonable time and resources to resolve the ecosystem issues. The governance of oceans and fisheries intersects with four major components: the production of fisheries, the protection of endangered marine species, the environment in which fish survive, and human use and interactions with the fish and oceans.

Based on the above, it can be argued that the joint governance of the oceans and fisheries as LMEs cannot ensure long-term sustainability. There are many differences among various governing instruments at regional levels. As significant attempts at the international level promote joint governance of oceans and fisheries, it is also imperative to develop such mechanisms at regional and national levels. A joint governance mechanism for oceans and fisheries as LMEs requires coherent governance, particularly for marine environmental and fisheries protection. However, the governance of LMEs is inadequate and incoherent and thus poses a severe challenge to SDG 14.

This research paper comprehensively analyzed and reviewed seventy-four regional Multilateral Environmental Agreements (MEAs) on ocean and fisheries governance. The following section analyzed scholarly journals, books, legal documents, and policy papers that provide theoretical and legal frameworks for further analysis. The UN policies and interpretation of the international courts and tribunals are systematically analyzed. Section 3 has developed a legal and theoretical framework for the methodology of analysis of the regional frameworks. The results provided links to the interconnection of SDGs with SDG 14, which can assist multilateral organizations in the development of joint governance of ocean and fisheries as LMEs. The conclusion followed the discussion on joint governance of LMEs presented in the form of policy principles at regional levels in Section 4. As the paper utilized various abbreviations, acronyms, and terms, for clarity, Table 1 is provided, which presents all the abbreviations, acronyms, and terms used in this paper.

Table 1.

List of abbreviations, acronyms, and terms utilized in this paper. Source—The abbreviations, acronyms, and terms utilized in this paper.

2. Ocean and Fisheries Policy (and Literature) Review: Current Challenges

While undertaking a systematic policy review, this research paper examined various sources, including scholarly journals, books, legal documents, and policy papers, as shown in Figure 1. It is important to note that this paper focused on the international legal framework for the joint governance of ocean and fisheries and not on all the regional conventions and treaties or the domestic laws of individual States. The methodology aims to identify the gaps between fisheries and ocean governance at regional levels, which causes severe impacts on sustainability. Additionally, when conducting a policy review on this topic, this section and the next section thoroughly considered both the positive and negative aspects of the international legal framework.

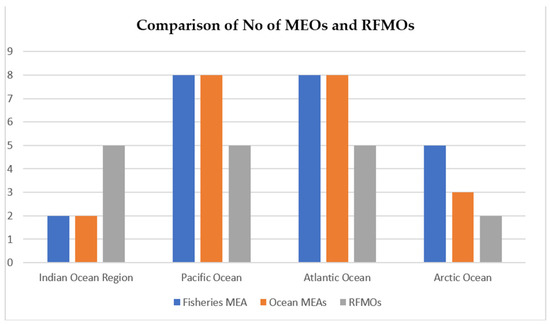

Figure 1.

Timeline of IEL for Joint Governance of LMEs. Source: This timeline is developed through the chronology of the discussion and analysis in this section.

The literature review begins with a review of international law with a timeline, as shown in Figure 1, that includes the interpretation of the UNCLOS and UNFSA by the international courts and tribunals. The international courts and tribunals, including the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) and Special Courts (mainly the Permanent Court of Arbitration PCA and International Court of Justice ICJ), serve as international forums for the resolution of disputes between nations regarding the interpretation and application of the UNCLOS [16]. The interpretation by these courts and tribunals while using the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (Vienna Convention) has been valuable in resolving disputes between nations concerning the joint governance of ocean and fisheries resources or LMEs [17].

As already discussed, the governance of oceans and fisheries is part of the broader subject of IEL. It was not until the Stockholm Declaration provided principle seven that obliged States to protect the marine environment as an ecosystem [18]. Perhaps establishing the UNEP–Regional Seas Program is the most significant achievement made through the Stockholm Declaration in ocean governance. Such advancement in the governance of the LMEs was made through two critical international instruments, known as the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), signed during the Earth Summit [19,20].

Although the provision of the CBD that defines ‘biodiversity’ does not include ‘marine biodiversity’, the parties to the Earth Summit established a thematic program on ‘coastal and marine biodiversity’ during the COP2 [21]. During the negotiations of COP2, the Jakarta Mandate was produced, which reaffirms the critical need to address the conservation and sustainable use of marine and coastal biodiversity [1]. The Jakarta Mandate further articulated ecosystem approach, precaution, science–policy integration, and top-down and bottom-up governance of the oceans and fisheries. This approach under the Jakarta Mandate is designed under the IEL, UNCLOS, and UNFSA and implemented at various regional levels [1]. At regional levels, various regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) are used for fisheries governance, and multilateral environmental organizations (MEOs) are used for ocean governance under the MEAs. The importance of RFMOs was enhanced with the Declaration on Responsible Fisheries in Marine Ecosystems (RFME) and was transformed through the World Summit on Sustainable Development (Johannesburg Declaration) [21].

While examining the policy related to the joint governance of oceans and fisheries, it is essential to consider both the positive and negative aspects of the MEAs at regional levels. Both the RFMOs and MEOs or Regional Organizations are effective in facilitating collaboration between States for the protection of fisheries and marine resources. Some of these organizations updated their governance mechanisms with the emergence of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [16,18]. However, other organizations have been criticized for lacking enforcement and failing to protect vulnerable species and marine habitats adequately due to ineffective governance under SDGs [1]. There is ample evidence of such failure, as can be observed by the deterioration of the marine environment, fish, and fisheries: depletion, eutrophication, pollution, and emerging diseases [1].

2.1. Interpretation of the IEL for the Governance of LMEs

UNCLOS limits the cooperation of the States in governance for joint governance of the oceans and fisheries. The principles of freedom of fishing at high seas’ and ‘coastal State jurisdiction’ challenge the sustainability of the oceans and fisheries. Therefore, other IEL conventions and declarations are interpreted with UNCLOS to ensure the sustainability of the oceans and fisheries [1]. This position of the IEL has been restated and maintained by the ITLOS in the MV Saiga Case [22]. ITLOS, in the MV Saiga Case, referred to the ‘marine environmental protection’ while restraining that particular fishing vessel, and that espouses a view close to a description of the ‘joint governance of oceans and fisheries’ or LMEs [23].

Festering such conflicts challenges the effective implementation of SDG 14, which the ITLOS has already realized in terms of joint governance of LMEs. ITLOS in the MV Saiga Case particularly ordered to maintain the oceans’ ecosystem while utilizing the ‘applicable law’ provisions of the Vienna Convention [16,24]. Generally, the provision of the Vienna Convention on ‘applicable law’ along with the provision of UNCLOS on ‘law not incompatible with’ expands the jurisdiction of the international courts [16]. Therefore, international courts under the IEL focus on protecting vulnerable species, habitats, and ecosystems and enforcing conservation measures, such as fishing quotas and gear restrictions [25].

Additionally, international courts seek to ensure the equitable and sustainable use of marine resources by all States and to prohibit any activities that are likely to cause harm to the marine environment. Such realm is foundational for SDG 14, yet it is markedly different from what has been interpreted. There exist diverse perceptions of jurisprudential ties, which differ from what has been perceived in the existing literature. A complex formal and informal ocean and fisheries governance mechanisms may value rationalities if, following the jurisprudence of the international courts, ITLOS expanded its jurisdiction and applied IEL in the Southern Bluefin Tuna Case [26]. In this case, ITLOS abstained from three States (Japan, Australia, and New Zealand) from fishing under a regional MEA (Convention on the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna-CCSBT) [27].

ITLOS applied both the UNCLOS and CCSBT without any overriding effect to protect the marine habitat (Southern Bluefin Tuna). Similarly, in the MOX Plant Case, a special tribunal constituted under the auspices of PCA stated that the ‘Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Northeast Atlantic (OSPAR Convention)’ is related to the UNCLOS and is mutatis mutandis applicable for the protection of the marine environment as per the IEL [28]. Broadly, the literature on maritime dispute settlement that reinforces joint governance of LMEs has also demonstrated how the settlement might result in unfair allocation, harming the marine environment and fisheries.

The Volga Case is another pertinent judgment by the ITLOS, in which the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCAMLR) and UNCLOS are jointly applied for marine and fisheries governance [29,30]. ITLOS stated in the Volga Case that while settling disputes, international courts shall also consider coordinated (joint) actions for combatting marine pollution and protecting marine habitats. The ITLOS further clarified joint governance of oceans and fisheries in its advisory opinion related to the Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with Respect to Activities in the Area. ITLOS underpinned the importance of governance of LMEs under the Rio Declaration while stating that ‘States shall have the responsibility to ensure that activities in the area shall be carried out in conformity with the UNCLOS’ [31].

In an advisory opinion in Request for an advisory opinion submitted by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission (SRFC), ITLOS endorsed that all issues close to the oceans (including marine habitat, marine environment, and ocean resources) are compatible with the UNCLOS [32]. ITLOS further endorsed the Convention on the definition of the minimum access conditions and exploitation of fisheries resources within the maritime zones under the jurisdiction of SRFC Member States (MAC Convention) with the UNCLOS for the governance of LMEs under SRFC. ITLOS followed its position in Advisory Opinion on the Area by clarifying the scope of UNCLOS on ‘activities in the Area’ [33]. ITLOS made an important statement on the scope of ‘responsibility of the States conducting activities in the area’ that they must ensure that their activities do not cause damage to the LMEs in the Area.

Protection of the LMEs is the justiciability of the ITLOS, and the PCA follows that in the South China Sea dispute [34]. A special tribunal formulated under the UNCLOS in the South China Sea dispute stated that all States to dispute under (regional and international) MEAs and UNCLOS should preserve the marine resources (oil and gas), minerals, and fisheries to maintain marine biodiversity [35]. PCA stressed that all States in the South China Sea have ‘direct obligations’ regarding any activity, among them the obligations to apply the precautionary approach and conduct an environmental impact assessment. PCA has interpreted and applied provisions of the UNCLOS by considering best practices and standards developed by international organizations, such as the FAO and IMO.

The discussion above shows that the jurisprudence of international courts is trending toward joint governance of fisheries and oceans. Such debate is going to serve as a beginning point for reviewing the UNCLOS, MEAs, and IEL governing LMEs. The decisions of the international courts provide substantive indicators to review the existing law. These indicators are ‘applicable law’ (applying two or more legislation for the governance of LMEs) and ‘compatible law’ (the legislation compatible under the UNCLOS for the governance of LMEs). Such interpretation provides two indicators, i.e., ‘applicable law’ and ‘compatible law’, to support the ecosystem-based approach through precautionary measures and science–policy integration.

2.2. United Nations Policies for Joint Governance of Oceans and Fisheries

After decades of rapid geographical expansion and technical developments, the global community has observed a several-fold increase in annual harvests, the marine environment is in the worst condition, and fisheries are at a crossroads [36]. The present global governance mechanism of LMEs often experiences great difficulties in effectively containing an expansion of redundant exploitation capacity and pollution problems. Some of the main challenges facing the governance of LMEs today include IUU fishing, overfishing, resource collapse, endangered species, and the environmental state of the coastal and marine zones [37]. Therefore, it has been suggested on several occasions that integrating fisheries governance into ocean governance with an interface between various ecosystems is a way forward [25].

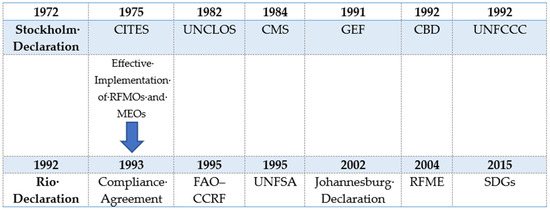

The United Nations (UN) recently established an interagency mechanism for the joint governance of oceans and fisheries, as shown in Figure 2. This agency is named UN-Oceans, which consists of representation from UNEP and FAO along with the Division on Oceans Affairs and Law of the Sea (UN-DOALOS), International Maritime Organization (IMO), and Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) (Figure 2) [38]. The UN-Oceans attempts to ensure coordination between the international organizations dealing with oceans and fisheries with an ecosystem-based approach. Such a mechanism is considered an adaptation of the oriented vision of sustainable development and conservation in the UNCLOS by subsequent practice building upon the Rio Declaration.

Figure 2.

International Organizations Impacting RFMOs for Governance of LMEs. Source: “Preserving Community’s Environmental Interests in a Meta-Ocean Governance Framework towards Sustainable Development Goal 14” [1].

In the context of ocean governance, UN-DOALOS serves as the Secretariat at the UN to monitor UNCLOS implementation. It is also important to note that UN-DOALOS has been regularly reporting on the issues of the IUU and over-fishing to the UN Secretariat [1]. IMO regulates shipping, which includes ship sources of pollution and fishing vessels (equipment for fishing, maritime labor, and health of the ships). IMO governs shipping pollution and regularly reports to relevant UN bodies (for example, UN-Oceans and UNEP) under the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) and Convention on the Prevention of the Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (Dumping Convention) [39,40]. IOC is responsible for the collective governance of the ocean and coasts. IOC also promotes mechanisms for sharing knowledge, information, and technology, as well as the coordination of various programs and capacity building in marine scientific research [1].

Governance of fisheries concerns two prominent organizations because ‘fisheries’ are considered an essential part of ‘nutrition’ and ‘marine ecosystems’. UNEP is responsible for effectively implementing CITES and CBD with the MEOs to protect marine habitats [41]. Moreover, UNEP also assists MEOs in sharing knowledge, information, good practices, and experiences to strengthen and maintain an overview of synergies between ongoing and upcoming marine environmental issues [42]. As a strategic partner of UN-Oceans, FAO aims to enhance coordination, coherence, and effectiveness of the CCRF and the Compliance agreement [43]. Moreover, the FAO aims to ensure that the duties of the states are to cooperate in the international, regional, and sub-regional implementation of the UNFSA.

The presence and use of ‘relevant institutions and international regulations’ have been developed within the UN systems, where the implementation of equitable principles came together with the recognition of all regional systems. The next section has developed a legal and theoretical framework that fosters SDG 14 based on this categorization of interconnections. The amalgamation of different organizations on a single platform shows that the UN, at the international level, is expanding its mandate for joint governance of oceans and fisheries [1]. Despite the milestones achieved with the adoption of the various mechanisms at international levels for the joint governance of oceans and fisheries, many issues remained insufficiently addressed. Such challenges can be addressed by the RFMOs and MEOs developed under the MEAs. The MEAs developing RFMOs and MEOs’ provisions contain far-reaching provisions with an ecosystem-based approach, precautionary measures, and science–policy integration.

2.3. MEAs Governing LMEs

Regional organizations play an essential role in the joint governance of oceans and fisheries. As regional organizations existed even before the UNCLOS entered into force, they provide a forum for collaboration between multiple States to protect shared fish stocks and marine ecosystems and to ensure the sustainable use of ocean resources [44]. One of the most critical aspects of these organizations is their ability to facilitate the negotiation and implementation of regional ocean and fisheries governance MEAs [45]. MEAs establish regional organizations that have various provisions for the sustainable management of oceans and fisheries. Most of these regional organizations govern in a manner that ensures institutional credibility, stability, and legitimacy in their decision-making processes [46]. These MEAs provide rules and regulations for the conservation, management, and utilization of ocean resources and can help to reduce overfishing and ensure the long-term sustainability of fish stocks.

The MEAs governing oceans and fisheries are substantive extensions of the UNCLOS, UNFSA, CCRF, and Compliance Agreement. The functions of both the RFMOs and MEOs vary at different levels. In principle, regional organizations cooperate for joint monitoring, information sharing, and capacity building. Regional organizations are functional when States see common gains in cooperating to overcome collective-action problems related to the use of regional seas situated in oceans [47]. In terms of LMEs, one can differentiate between regional organizations because some of them are for scientific research, some are for fisheries (Total Allowable Catches under UNFSA/UNCLOS), some are for marine environmental protection (under the UNCLOS and IEL), and some are for exploitation of ocean resources [25]. Therefore, some regional organizations lack credibility due to political and geographical conflicts between States in specific regions.

Such a crisis in the effectiveness of regional organizations has already been recognized and is under a new round of debate over the form and function of IEL. In contrast, UN-DOALAS and UN-Oceans have suggested more comprehensive sub-regionalization in response to shifting political alliances and new environmental challenges [1]. Such suggestions are based on the UNFSA and UNCLOS, representing a trend towards sub-regionalism in the governance of LMEs. UN-Oceans also reiterated the Rio Declaration to govern complex (marine) environmental problems [48]. Moreover, the interpretation of the law of the sea, including the CCRF and Compliance Agreement, complements the regional approach to the governance of LMEs.

A new agreement for the governance of areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ) is in the final stages; potential clauses exist in the MEAs governing regional organizations for the protection of the marine environment and fisheries preservation with coherency [49]. The analysis catalyzes regional organizations’ frameworks in line with the international mechanisms governing oceans and fisheries. Regional organizations have evolved through the FAO system while recognizing that inadequate fisheries’ governance mechanisms exist [50]. These organizations face explicit challenges of negotiating with independence, finance, staff, and administration.

The jurisdictional limits of the RFMOs highly impact the marine environment and habitat. Such limitations are also contrary to the provisions of the UNCLOS and IEL. UNCLOS and IEL can be expected to considerably impact the RFMOS on jointly managing fisheries and the ocean. In doing so, FAO recognized that the organization needed strengthening and modernization in light of the development of international fisheries law [51]. Therefore, in the next section, thirty-four regional fisheries and forty ocean-governing MEAs have been reviewed and suggested at the end as to how a concrete mechanism of joint ocean and fisheries governance can be developed.

3. Legal and Theoretical Framework—Application of Methodology

The threefold literature review (including decisions of the courts, UN systems, and regional mechanisms) portrayed a new understanding of SDG 14. This means that the conceptualization of SDG 14 is not new as a form of joint governance of ocean and fisheries; it already exists in jurisprudence, law, and practice. However, many practices and international regulations have failed to provide adequate governance for protecting the marine environment and preserving fisheries. Therefore, SDG 14 appears as an opportunity to develop new means of governing LMEs.

3.1. Framework

SDG 14, entitled ‘Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources for sustainable development,’ presents international organizations’ jurisprudence and practices (as shown in Table 2). Moreover, by stating that ‘conserve at least 10 percent of coastal and marine areas, consistent with national and international law and based on the best available scientific information’, SDG 14 substantiates the existing UNCLOS and IEL. Other purposes stated in SDG 14, such as ‘Increase scientific knowledge, develop research capacity and transfer marine technology, taking into account the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission Criteria and Guidelines on the Transfer of Marine Technology, to improve ocean health and to enhance the contribution of marine biodiversity’ is one of the objectives of UNCLOS (Table 2).

Table 2.

SDG 14 and Its Legal Basis with Supporting Literature (Theoretical and Legal Framework). Source: Developed on the basis of literature and SDG 14.

RFMOs and MEOs play an essential role in the joint governance of oceans and fisheries. Both provide a forum for collaboration between multiple nations to protect shared fish stocks and marine ecosystems and to ensure the sustainable use of ocean resources. It is crucial to consider both the positive and negative aspects of RFMOs and to examine their effectiveness in protecting vulnerable species, marine habitats, and shared fish stocks [1]. The RFMOs and MEOs developed under the MEAs are of an advisory nature with limited enforcement powers unless the States act themselves for the governance of LMEs [1]. Therefore, the MEOs require substantial modification to implement elements of RFMOs or vice versa.

Regional organizations could be reorganized mainly according to organizational functions, formation purposes, and regions. The regional organizations had multiple responsibilities and relatively limited powers, and there were different fisheries species to govern. However, in the last eight years, policy prescriptions for addressing the global crisis in fisheries have centered on strengthening SDG 14 [54]. SDG 14 clarifies individual and community rights of access to fisheries. With a focus on small island developing States (SIDS) and least developed countries (LDCs), SDG 14 bases the case for fisheries governance reform on assumed economic incentives under ocean governance mechanisms [52].

More secure, less vulnerable fisheries make more effective and motivated ocean governance mechanisms in the context of participatory or rights-based policy systems [55]. The perspective under SDG 14 goes well beyond the widely advocated notion of ‘multi-level ocean governance’ and aligns with how fisheries govern in the context of international development. Embedding the fisheries governance challenges within a broader perspective of ocean governance enhances the chances of achieving both human development and resource sustainability outcomes [56]. There are many arguments that might be advanced to suggest that this “thought experiment” in advancing equity under the UNCLOS and IEL should receive no further attention because it unfairly privileges a minority interest at the expense of the majority interests [56]. However, the lack of institutional capacity in the developing world forwards the equity implications (e.g., between poor and rich or between developed and developing countries) for joint governance of LMEs.

In addition to the apparent challenges in getting RFMOs to fulfill coordinating roles, there are coordination issues with other regional arrangements for the LMEs. Mainly, the failure of some States to accept and implement UNCLOS and IEL and a lack of willingness by some States to delegate sufficient responsibility to RFMOs and MEOs appear to be obstacles to the effective implementation of SDG 14 [53]. The significance of cooperation and coordination among and between RFMOs and MEOs is prominent in SDG 14; sustainable development goals 1, 2, 11, and 17 explicitly refer to regionalism for sustainable development [1]. Therefore, enhanced governance of LMEs has been proposed as an essential component of achieving SDG 14 through this research. It has also been argued that the RFMOs and MEOs shall play a key role in the governance of ABNJ, which is being addressed by a new global agreement.

3.2. Methodology

Regarding governing LMEs, regionalization is referred to as a policy-administrative process of establishing spatially determined scales of (various) organizations that devolve decision-making and create more responsible and adaptive mechanisms. There are thirty-one RFMOs, nine under the auspices of the FAO Constitution and 24 under MEAs between two or more contracting parties. On the other hand, eighteen MEOs globally govern the marine environment; ten work in close collaboration with UNEP, and others work independently. The obstructive factors in progress and the effectiveness of regional organizations are discussed and analyzed in this section. This section utilizes the policy (and the literature) review as a method to make a theoretical contribution to the literature on regional and sub-regional governance of LMEs. This section is advanced by clarifying the provisions of MEAs (of RFMOs and MEOs) that have the potential to develop LME governance mechanisms. The criteria used to evaluate the quality of each MEA are based on the elements of governance as mentioned above, including joint monitoring, information sharing, and an ecosystem-based approach. A regional approach has been utilized to evaluate MEAs governing each ocean.

3.3. Analysis

As discussed in the sections mentioned above, the capacity of RFMOs and MEOs shall be improved for the global governance of LMEs, ranging from policy development through organizational planning to technology transfer. The RFMOs shall have the capacity to coordinate among MEOs in order to achieve the integration required for the successful implementation of SDG 14. For each ocean, the number of LMEs, their total area, the number of States in that region, and the number of MEAs are relevant to governing organizations [43]. As SDG 14 urges states to effectively regulate fisheries’ preservation by ending overfishing, IIU fishing, and destructive fishing practices, it also calls for regional cooperation. Therefore, in such terms, SDG 14 supports the notions of SDG 1, 11, and 17, calling for robust national, regional, and international policy frameworks [41].

Most external RFMOs and MEOs are connected to an international governance system. UNEP–Regional Seas, FAO fisheries governance programs, and IMO Port State Control MOUs for fisheries vessels are essential in these regards [32]. In this way, there is oversight and coordination at the global level within most of the MEAs. Such arrangements interact with SDG 14 while recalling ‘for an increase in the economic benefits to SIDS and LDCs from the sustainable use and management of fisheries and aquaculture and providing access for small-scale artisanal fishers to marine resources and markets’. In this scenario, SDG 14 rationalizes SDG 11 and 17, which endorses positive economic, social, and environmental links by strengthening national and regional development planning and cooperation on and access to science, technology, and innovation and enhancing knowledge-sharing on mutually agreed terms.

3.3.1. Analysis of the Challenges in the Indian Ocean Region

Although the Indian Ocean regions have historically lacked strong MEAs focused on environmental protection and fisheries preservation, some relevant initiatives have been shown in Table 3. Two regional MEAs govern fisheries in the Indian Ocean Region: (i) the Agreement Establishing the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission (IOTC Agreement) and (ii) the Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFC Agreement) [57,58]. Although there is noticeable agreement on some of the principles and systematic approaches, significant differences remain in various elements of governance. IOTC established a committee for the management of Indian Ocean Tuna to consider governance measures for tuna stocks, and SIOFC aims to ensure and promote the long-term conservation and sustainable use of fishery resources.

Table 3.

RFMOs and MEOs under MEAs governing the Indian Ocean Region. Source: Chronology of the MEAs development as discussed in this section.

Governance strategies for fisheries in the Indian Ocean region have focused on the trade-offs and complementarities between cooperation and national strategy in terms of economic gains [59]. Less attention is paid to a better understanding between the States in the region and to creating better governance mechanisms for LMEs. Furthermore, the existing RFMOs have established research coordination programs [60]. The Southwest Indian Ocean Fisheries Project (SWIOFP) allows for integrated approaches to IOTC and SIOFC [61]. A serious constraint is the inadequate enforcement of and compliance with governance measures in the Indian Ocean region. Unlike other Oceans (as discussed below), where collaboration through RMFOs and MEOs is common, the Indian Ocean region demonstrates that while there are a number of issues and challenges, there is rarely involvement of all relevant States and stakeholders.

Both the RFMOs attempt to cooperate and coordinate with MEOs, but apparently, their efforts remain in vain due to the complex political considerations. The Indian Ocean region consists mainly of developing or undeveloped states that require financial and technical support from the FAO, UN-Oceans, or other relevant UN bodies [62]. With the continual decline in fish stock abundance and increased fishing pressure throughout the Indian Ocean, it is evident that there are plenty of institutional barriers in the monitoring, evaluation, and information-sharing processes within the RFMOs. The credibility of an allocation provided under the UNCLOS and IEL becomes questionable in the MEAs governing the Indian Ocean Region. Even though established rules and regulations exist in the MEAs governing the Indian Ocean Region, they are not effective without reducing the time gap between data submission, scientific analysis, and decision-making.

3.3.2. Challenges in the Pacific Ocean

Regional organizations in the Pacific Ocean region function within a web of treaties and institutional frameworks, as shown in Table 4. Through such primary cooperation, in the North-Pacific Ocean, the Commission for the Conservation of Anadromous Stocks (CCAS) and North Pacific Fisheries Commission (NPFC) are created under the presence of many factors and are defined theoretically as necessary for the successful formation of stable regional cooperation [63,64]. From a historical perspective of the Bering Sea Arbitration settlement, the Convention on the Conservation and Management of Pollock Resources (CCMPR) in the Central Bering Sea is another essential instrument for the preservation of the marine habitat in the Southeast and North-Pacific region [65]. Other sub-regional organizations are the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission (WCPFC), International Pacific Halibut Commission (IPHC), and South Pacific Regional Fisheries Management Organization (SPRFMO) [66,67].

Table 4.

RFMOs and MEOs under MEAs governing the Pacific Ocean Region. Source: Chronology of the MEAs development as discussed in this section.

Additionally, treaty-defined sub-regional MEOs are also involved in fisheries governance. The sub-regional MEOs supported the formation of independent RFMOs in the region [1]. Although regional organizations support a complex set of governance and institutional arrangements, they can be commended as the most sophisticated sets of collaborative tools in global ocean governance [16]. Strong coordination exists among most of the regional organizations working in the Pacific Ocean, ensuring a variety of standard mechanisms from which a range of global and national conservation and ocean and fisheries policies can emerge [1]. The model of Pacific Ocean governance consists of a range of actors, subsidiarity, and democratization, which essentially creates joint mechanisms for monitoring, evaluation, and information sharing.

Agreements related to the International Dolphin Conservation Programs and the Pacific Salmon Treaty are high-level commitments already made that require guidance, will, and resources for the governance of RFMOs in the Pacific Ocean [68,69]. Both treaties contain enough theoretical principles and technical guidance from the FAO to support the implementation of the CCRF and Compliance Agreement under the provisions of the UNFSA and UNCLOS. A wide range of mechanisms engage stakeholders through formal and informal processes. Stakeholder engagement positions the consolidation of interests and sustainability in joint governance mechanisms. However, there is much to be completed before all necessary RFMOs can coherently implement all the Pacific Ocean instruments. Evolution is required regarding enforcement mechanisms that include transparency, more decentralization, capacity building, and transfer of technology [1]. In addition, the limits of the regional organizations will need to be reconsidered to better match the limits of the LMEs.

The regional emphasis of the States and various organizations developed under MEAs reflects the influence of IEL and UNCLOS. Such prominence in governance models indicates regional orientation, which affects cooperation and participation for mutual benefits. In this context, it is worth noting that the MEAs operating in the Pacific Ocean contain restrictive membership language, defining it as “real interest” in the fisheries concerned [25]. Moreover, the criteria to be considered in each MEA determines the nature and extent of participating rights. In some instances, these agreements resolve conflicts and difficulties in operationalization. However, the involvement of multinational companies in fishing impacts the rights of maritime or coastal communities. Therefore, each State in the Pacific Ocean region is somehow attempting to develop “local” enterprises or other types of incorporated bodies, increasingly ensuring local participation.

3.3.3. Challenges in the Atlantic Ocean

Atlantic Ocean regions are entirely developed regarding MEAs consisting of robust policy cycles under IEL and UNCLOS, as shown in Table 5. The scopes of arrangements under MEAs comprise external and indigenous communities. Strong local participation exists in each MEA, and the proportion of fisheries and ocean governance MEAs are higher in the external arrangements. From the perspective of joint governance, the Convention for the Conservation of Salmon in the North Atlantic Ocean, the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR Convention), and the Convention on the Protection of the Marine Environment of the Baltic Sea (HELCOM or Helsinki Convention) is an exemplary match between arrangements and ecosystems commonly observed in marine systems [70,71]. Under the Convention on Future Multilateral Cooperation in the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries, the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization is also operative in this region along with the North Atlantic Salmon Conservation Organization [72,73].

Table 5.

RFMOs and MEOs under MEAs Governing the Atlantic Ocean. Source: Chronology of the MEAs development as discussed in this section.

Notably, the MEOs (Baltic Marine Environment Protection Commission and OSPAR Commission) in the North Atlantic Region support RFMOs in marine cadastral space to “provide an ability to define, manage, and administrate boundaries” [72]. These regional organizations adopt a holistic approach to crosscutting sectoral policies and interact with the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism (which acts under the Agreement establishing the Caribbean regional fisheries mechanism and the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (which acts under the Agreement establishing the Caribbean Regional Fisheries Mechanism) [74,75]. This approach helps to apply IEL and UNCLOS on the Atlantic Ocean with the North-South approach. It helps in implementing the Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles and the Convention for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas [74,75,76]. Informal engagement of stakeholders exists in the fisheries MEAs, allowing contextualized governance initiatives and a common understanding of the Atlantic Ocean Region. Such engagement places emphasis on the MEAs’ ability to achieve sustainability and interests while sharing space in the region.

In the Mediterranean Sea, the Black Sea Commission and the special administrative units of the European Commission work together under the Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea Against Pollution (Barcelona Convention) and Convention on the Protection of the Black Sea Against Pollution (Bucharest Convention) for the protection of the marine environment in the region [77,78]. These arrangements have a broader effect on the Western Central Atlantic Fisheries Commission, which works closely with FAO. All the RFMOs also work alongside FAO to effectively implement fisheries MEAs under UNCLOS and IEL.

All the RFMOs in the Atlantic Ocean evolved through FAO systems recognizing adequate MEOs. Still, there were several deliberations at that time to establish an independent body outside the framework of the FAO. Still, it is decided that it would need to be a long-term goal due to the complex political considerations. Moreover, the States in the region felt that they needed the financial and technical support of the FAO in the initial development of the organization. The FAO formulated the draft agreement, reflecting the negotiations and giving greater autonomy to RFMOs compared to MEOs [50]. However, as FAO governs them, all the RFMOs are within the UN system’s boundaries, which has so far failed to find a solution for the effective governance of LMEs.

3.3.4. Challenges in the Arctic Ocean

The importance the Arctic Ocean requires is never provided to it. As the melting ice of the Arctic Ocean poses grave climate and food security challenges, global cooperation in ocean governance requires more deliberation [79]. The challenges that are gradually manifested in developing relationships between fisheries and ocean governance (as discussed in the previous sections) overlap the Arctic Ocean in different ways. The Central Arctic Ocean, as governed under the International Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean, is partially governed by the Nauru Agreement, OSPAR Convention, and HELCOM (as shown in Table 6). However, the existing challenges need deeper consideration of the causes and effects of natural variability and ecological variations in the Arctic Ocean [80].

Table 6.

RFMOs and MEOs under MEAs governing the Arctic Ocean. Source: Chronology of the MEAs development as discussed in this section.

A particular formula of regional cooperation is required in fisheries governance because the existing mechanisms under the Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources and the Convention on the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna lack technical implementation [81]. Moreover, scientific research in the Arctic Ocean through the Agreement on Enhancing International Arctic Scientific Cooperation under the auspices of the IMO shall be based on a supra-regional model [82]. This suggestion is made because the Arctic Ocean is full of resources, and at the same time, it is quite remote to access.

It is already established that the fisheries of the Arctic are moving towards the sub-Arctic regions due to the summer retreat [25]. The melting ice and the warming of the oceans compel fisheries to move towards the north. Therefore, the prospects of fishing in the Arctic Ocean are increasing, though it is unclear in terms of the kind of fisheries, their numbers, and the time they are in operation. Fisheries Governance under the Ottawa Charter protects fishing vessels [83]. Therefore, IMO has established the International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters. However, the Treaty on ABNJ is now more demanding regarding the governance of the Arctic Ocean. One aspect of a few arrangements in the Arctic Ocean is that several RFMOs and MEOs of other regions come under this region’s heading. Another aspect is the observation of a high proportion of climatic vulnerabilities.

4. Sustainable Development Goal 14 (Life Below Water): Prospects and Way-Forward

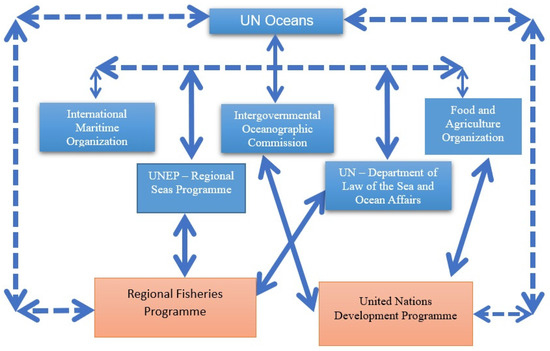

In the Pacific Ocean and Atlantic Ocean regions, there are eight fisheries MEAs and RFMOs (as shown in Figure 3). This position depicts the goal-based approach of the States in this region in accordance with the fisheries governance targets of SDG 14. Moreover, five MEOs in both regions collaborate with the states to address marine environmental issues. However, there are only two fisheries MEAs in the Indian Ocean and five in the Arctic Ocean regions. This places an additional and significant burden on the States in these regions about the extent “of the perception that fragmentation at the regional level leads to duplication of effort and inefficiency deter engagement?” and “should be explored systematically through a programmatic approach to regional ocean governance” [73,82]. Such issues shall be explored and understood to inform initiatives to establish regional coordination mechanisms under the broader framework of UNCLOS and IEL.

The data shown in Figure 3 identify fisheries and Ocean MEAs emerging from the multilateral cooperation. These data are used to analyze the problems faced by ocean regions with fewer MEAs and MEOs; the restriction in the development of more meaningful agreements is identified as a lack of institutional approach, leadership, political adherence, and legal understanding of oceanic issues [65]. The progress made thus far has not been without difficulties in the Pacific and Atlantic Ocean regions, despite the financial, technical, and human support supplied by a wide range of dedicated players from many sectors and jurisdictional levels ranging from local to global [43]. Overcoming institutional and capacity restrictions has proven to be particularly difficult for the regions participating in global ocean governance.

Such a process can be further enhanced to ensure the transformative potential of stakeholders. Facilitating stakeholders through multiple levels in the governance of fisheries (because most of the stakeholders are involved in fisheries governance) shall lead to novel perspectives, agreements, and cooperation [75]. The stakeholders, through participation, provide a better understanding of the MEOs and RFMOs as observed in the Atlantic and Pacific Ocean regions. Transforming SDG 14 into action at the local and national levels requires the systematic engagement of the stakeholders, RFMOs, and MEOs [84]. The governance through such a systematic approach fosters the process of implementing a sustainable mechanism towards the sustainability of the oceans and fisheries as LMEs.

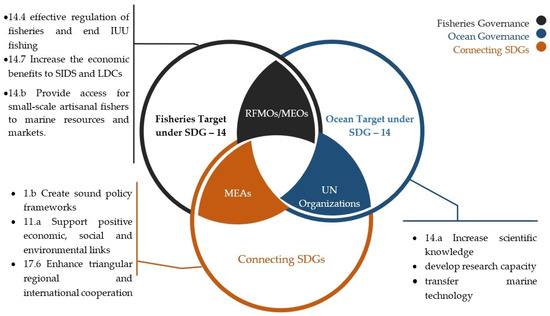

The characteristics of the governance arrangements comprising each region are shown in Figure 3. Governance of LMEs strategically can be developed with the UNEP Program, as shown in Figure 4. As FAO covers most of the fisheries MEA, indigenous participation can be strengthened with SDG 2 and 4, which call for “more agricultural productivity and incomes of small-scale food producers, in particular women, indigenous peoples, family farmers, pastoralists and fishers, including through secure and equal access to land, other productive resources and inputs, knowledge, financial services, markets and opportunities for value addition and non-farm employment” [52]. Even while a new treaty governing ABNJ is being established, to better gauge the governing mechanisms for LMEs, the RFMOs, and MEOs should be better able to reflect in policy systems [53]. The reference data for global information shall be improved to understand the current situation of LMEs [84]. Although efforts are being made to improve the data, assisting RFMOs and MEOs in revising their systems and providing training courses is utterly required. Additionally, to improve quality, timeliness, and transparency, UN Oceans and FAO shall start the development of a global cooperative governance program for LMEs [85,86]. In such a way, RFMOs and MEOs shall be connected to UN Oceans, UNEP, FAO, and other relevant organizations to better mobilize the competencies and information available [87].

Figure 4.

Prospects of Strong RFMOs and MEOs with SDG 14. Source: SDGs Final List of Proposed Indicators supported by the framework developed through this research.

Furthermore, crosscutting governance implications require technical solutions in the ongoing realm of technological advancements. Utilization of marine technology for oceanic research and development shall assist the RFMOs and MEOs in monitoring, data collection, and evaluation of ocean health [88]. Technological advancement has already provided monitoring and data tools to RFMOs and MEOs, which are utilized in policy and decision-making. However, as provided in UNCLOS, legal and regulatory issues hamper the technological solutions because of threats to the marine environment. Therefore, such technological advancements and solutions that do not impact the marine environment shall be vital for the joint governance of the ocean and fisheries as LMEs in the near future.

Given the above, it is established that monitoring the oceans for the condition of fisheries, marine resources, and the environment shall be substantially strengthened in the interest of sustainability. Such mechanisms for improved governance of LMEs call for more transparency and better public information/participation. In this case, UNCLOS and IEL are the fundamental foundations on which a new system of governance under SDG 14 can be built. FAO Code of Conduct as an operational instrument has been recognized as a procedural tool for RFMOs, and UNEP Regional Seas Program/UN-Oceans are central/international organizations for ocean governance. Therefore, the global arrangements shall be improved to reduce potential duplication and conflicts with and among RFMOs and MEOs.

5. Conclusions

This research paper discussed and analyzed complex and heterogeneous challenges to joint ocean and fisheries governance depending on regions. The relative policy and capacity support that the States shall provide to RFMOs and MEOs is not in place to achieve SDG 14. Moreover, SDG 14 is not very strongly organized within UN systems, RFMOs, and MEOs, and the result is that the capacity of regional organizations for effective implementation is limited. This could become a problem at a time when States and the UN have to decide which RFMO or MEO to put the coming ABNJ in. Large and vertically integrated RFMOs and MEOs are getting more involved in the international debate about the pros and cons of SDG 14. In the coming evolutionary process of governing LMEs, a much greater involvement of States, RFMOs, MEOs, and UN organizations will be essential. Further research on the joint governance of LMEs is going to be developed on the legal basis of SDG 14 under UNCLOS and IEL. Moreover, scientific advancement and technological development in oceanic research shall be valuable in the future of governing LMEs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.Z., M.M.Z.B. and Q.W.; methodology, S.Z., M.M.Z.B. and Q.W.; formal analysis, Y.-M.L. and Y.-E.-W.; investigation, Y.-M.L. and Y.-E.-W.; resources, S.Z. and Q.W.; data curation, M.M.Z.B.; writing—original draft preparation, S.Z., M.M.Z.B. and Q.W.; writing—review and editing, Y.-M.L. and Y.-E.-W.; supervision, S.Z.; project administration, S.Z.; funding acquisition, S.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The funding for this fieldwork was provided by Institute of Eco-Environmental Forensics. This research work was supported by the Research Project: “Theoretical Contributions of Law and Policy in Marine Environmental Preservation and Ocean Development Programme, Environmental Integration and Justice Department” (Funding No: 1324-MJB-2022.) provided to Institute of Eco-Environmental Forensics, Economic and Environmental Law Institute, Shandong University, Qingdao, China.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank the Institute of Eco-Environmental Forensics at School of Law, Shandong University, for providing assistance and resources in writing this paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Zulfiqar, K.; Butt, M.J. Preserving Community’s Environmental Interests in a Meta-Ocean Governance Framework towards Sustainable Development Goal 14: A Mechanism of Promoting Coordination between Institutions Responsible for Curbing Marine Pollution. Sustainability 2021, 13, 9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laffoley, D.; Baxter, J.M.; Amon, D.J.; Claudet, J.; Downs, C.A.; Earle, S.A.; Gjerde, K.M.; Hall-Spencer, J.M.; Koldewey, H.J.; Levin, L.A. The Forgotten Ocean: Why COP26 Must Call for Vastly Greater Ambition and Urgency to Address Ocean Change. Aquat. Conserv. Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 2022, 32, 217–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lennan, M.; Morgera, E. The Glasgow Climate Conference (COP26). Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2022, 37, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment. 1973. (U.N. Doc. A/Conf.48/14/Rev. 1). Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/stockholm1972 (accessed on 11 January 2024).

- United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea. 1982. (Came into Force on 16 November 1994, (1833 UNTS 397)). Available online: https://www.un.org/depts/los/convention_agreements/texts/unclos/unclos_e.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2023).

- Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals; (Enforced 1991), (UNTS 1651; 1983). Available online: https://www.cms.int/#:~:text=The%20Convention%20on%20Migratory%20Species,migratory%20animals%20and%20their%20habitats (accessed on 26 December 2023).

- Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora; (Enforced 1975); 1973. (993 UNTS 243). Available online: https://cites.org/eng/disc/text.php (accessed on 19 November 2023).

- United Nations Conference Declaration on Environment and Development; 1992. (UN Doc. A/CONF.151/26 (vol. I)). Available online: https://www.un.org/en/conferences/environment/rio1992 (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- Biagini, B.; Bierbaum, R.; Stults, M.; Dobardzic, S.; McNeeley, S.M. A Typology of Adaptation Actions: A Global Look at Climate Adaptation Actions Financed through the Global Environment Facility. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2014, 25, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on the Conservation and Management of Highly Migratory Fish Stocks in the Western and Central Pacific Ocean, 2000. (Enforced—2004) (2275 UNTS 43). Available online: Https://Treaties.Un.Org/Pages/showDetails.Aspx?Objid=0800000280074802 (accessed on 25 December 2023).

- Coll, M.; Libralato, S.; Pitcher, T.J.; Solidoro, C.; Tudela, S. Sustainability Implications of Honouring the Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitcher, T.; Kalikoski, D.; Pramod, G. Evaluations of Compliance with the FAO (UN) Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries. 2006. Published by Fisheries Centre Research (Reports 2006 Volume 14 Number 2). Available online: https://iuuriskintelligence.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Free-FCRR_2006_14-2-Report-for-53-countries.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- Birnie, P. New Approaches to Ensuring Compliance at Sea: The FAO Agreement to Promote Compliance with International Conservation and Management Measures by Fishing Vessels on the High Seas. Rev. Eur. Comp. Int’l Envtl. L. 1999, 8, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner-Kramer, D.M.; Canty, K. Stateless Fishing Vessels: The Current International Regime and a New Approach. Ocean. Coast. LJ 2000, 5, 227. [Google Scholar]

- Agreement on Port State Measures to Prevent, Deter and Eliminate Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing, 2009. (Enforced 2016) (US Senate Consideration of Treaty Document 112-4). Available online: https://www.Congress.Gov/Treaty-Document/112th-Congress/4/Document-Text (accessed on 10 February 2024).

- Butt, M.J.; Zulfiqar, K.; Chang, Y.-C.; Iqtaish, A.M.A. Maritime Dispute Settlement Law towards Sustainable Fishery Governance: The Politics over Marine Spaces vs. Audacity of Applicable International Law. Fishes 2022, 7, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties. 1969. (Came into Force 27 January 1980, (1155 UNTS 331)). Available online: https://legal.un.org/ilc/texts/instruments/english/conventions/1_1_1969.pdf (accessed on 24 January 2024).

- Chang, Y.-C. Good Ocean Governance. Ocean. Yearb. Online 2009, 23, 89–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention on Biological Diversity. 1992. (Came into Force on 29 December 1993, (1760 UNTS 79)). Available online: https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=XXVII-8&chapter=27 (accessed on 21 January 2024).

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. 1992. (1771 UNTS 107). Available online: https://unfccc.int/ (accessed on 23 January 2024).

- Robinson, M. COP-26: The Political Conundrum. Round Table 2021, 110, 606–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, E. The M/V’ Saiga’ Case on Prompt Release of Detained Vessels: The First Judgment of the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea. Mar. Policy 1998, 22, 307–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de La Fayette, L. ITLOS and the Saga of the Saiga: Peaceful Settlement of a Law of the Sea Dispute. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2000, 15, 355–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de la Fayette, L. International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea: The M/V “Saiga” (No.2) Case (St. Vincent and the Grenadines v. Guinea), Judgment. Int. Comp. Law Q. 2000, 49, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Butt, M.J.; Iqatish, A.; Zulfiqar, K. China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) under the Vision of ‘maritime Community with a Shared Future’ and Its Impacts on Global Fisheries Governance. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schiffman, H.S. The Southern Bluefin Tuna Case: ITLOS Hears Its First Fishery Dispute. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 1999, 2, 318–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convention for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna, 1993 (Enforced 1994). (1819 UNTS 359). Available online: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%201819/volume-1819-I-31155-English.pdf (accessed on 12 March 2023).

- MOX Plant Case, Ireland v United Kingdom. 2003. (Order No 3, (2003) 126 International Law Reports 310) Special Arbitral Tribunal Constituted under the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Available online: https://www.itlos.org/en/main/cases/list-of-cases/case-no-10/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- The “Volga”, Russian Federation v Australia. (Prompt Release, ITLOS Case No 11, International Courts of General Jurisprudence 344 (ITLOS 2002)). Available online: https://www.itlos.org/en/main/cases/list-of-cases/case-no-11/ (accessed on 13 June 2023).

- Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources, 1980 (Enforced 1982). (1329 UNTS 47). Available online: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/organisation/camlr-convention-text (accessed on 29 May 2023).

- Responsibilities and Obligations of States Sponsoring Persons and Entities with Respect to Activities in the Area. (Advisory Opinion, ITLOS Case No 17, (2011) ITLOS Rep 10, International Courts of General Jurisdiction 449 (ITLOS 2011)). Available online: https://www.itlos.org/index.php?id=109 (accessed on 29 April 2023).

- Becker, M.A. Request for an Advisory Opinion Submitted by the Sub-Regional Fisheries Commission (SRFC). Am. J. Int. Law 2015, 109, 851–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, Y. Obligations and Liability of Sponsoring States Concerning Activities in the Area: Reflections on the ITLOS Advisory Opinion of 1 February 2011. Neth. Int. Law Rev. 2013, 60, 205–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talmon, S. The South China Sea Arbitration and the Finality of ‘Final’ Awards. J. Int. Disput. Settl. 2017, 8, 388–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kojima, C. South China Sea Arbitration and the Protection of the Marine Environment: Evolution of UNCLOS Part Xii Through Interpretation and the Duty to Cooperate. Asian Yearb. Int. Law 2017, 21, 166–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anyanova, E. Oil Pollution and International Marine Environmental Law. In Sustainable Development–Authoritative and Leading Edge Content for Environmental Management; Curkovic, S., Ed.; Intech Open: London, UK, 2012; pp. 29–54. [Google Scholar]

- Boczek, B.A. Global and Regional Approaches to the Protection and Preservation of the Marine Environment. Case W. Res. J. Int’l L. 1984, 16, 39–70. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Oceans and the Law of the Sea; Report of the Secretary-General; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008; Available online: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/437569?ln=en (accessed on 24 June 2023).

- International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ship (MARPOL 73/78). 1973. (Came into Force on 26 November 1983, (1340 UNTS 184)). Available online: https://www.imo.org/en/about/Conventions/Pages/International-Convention-for-the-Prevention-of-Pollution-from-Ships-(MARPOL).aspx#:~:text=The%20International%20Convention%20for%20the,from%20operational%20or%20accidental%20causes (accessed on 21 June 2023).

- International Maritime Organization. Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter; 26 UNTS 2403; International Maritime Organization: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Environment Programme. UNEP the Global Environmental Agenda Annual Report; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 2015; pp. 1–57. [Google Scholar]

- Environment, U.N. Why Does Global Clean Ports Matter? Available online: http://www.unenvironment.org/explore-topics/transport/what-we-do/global-clean-ports/why-does-global-clean-ports-matter (accessed on 17 November 2019).

- Telesetsky, A. UN Food and Agriculture Organization: Exercising Legal Personality to Implement the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. In Global Challenges and the Law of the Sea; Ribeiro, M.C., Loureiro Bastos, F., Henriksen, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Barnes-Dabban, H.; van Koppen, C.S.A.; van Tatenhove, J.P.M. Regional Convergence in Environmental Policy Arrangements: A Transformation towards Regional Environmental Governance for West and Central African Ports? Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2018, 163, 151–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caviedes, V.; Arenas-Granados, P.; Barragán-Muñoz, J.M. Regional Public Policy for Integrated Coastal Zone Management in Central America. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 186, 105114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnes-Dabban, H.; Karlsson-Vinkhuyzen, S. The Influence of the Regional Coordinating Unit of the Abidjan Convention: Implementing Multilateral Environmental Agreements to Prevent Shipping Pollution in West and Central Africa. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 2018, 18, 469–489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bateman, S. UNCLOS and Its Limitations as the Foundation for a Regional Maritime Security Regime. Korean J. Def. Anal. 2007, 19, 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Summary Report: Seventeenth Meeting of UN-Oceans; Reports of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization: Paris, France, 2018; p. 23. [Google Scholar]

- Office of the Legal Affairs. Intergovernmental Conference on Marine Biodiversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction; Office of the Legal Affairs: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pauly, D.; Zeller, D. Comments on FAOs State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA 2016). Mar. Policy 2017, 77, 176–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosch, G.; Ferraro, G.; Failler, P. The 1995 FAO Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries: Adopting, Implementing or Scoring Results? Mar. Policy 2011, 35, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Development Programme. Final List of Proposed Sustainable Development Goal Indicators; Report of the Inter-Agency and Expert Group on Sustainable Development Goal Indicators; United Nations Development Programme: Geneva, Switzerland, 2016; p. 25. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, M.M.; Shamsuddoha, M. Coastal and Marine Conservation Strategy for Bangladesh in the Context of Achieving Blue Growth and Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Environ. Sci. Policy 2018, 87, 45–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.J. The Role of the International Law in Shaping the Governance for Sustainable Development Goals. J. Law Political Sci. 2021, 28, 95–164. [Google Scholar]

- Colard-Fabregoule, C. Chapter 7—Maritime Spatial Planning: A Means of Organizing Maritime Activities Measured Iin Terms of Sustainable Development Goals. In Global Commons: Issues, Concerns and Strategies; Pillai, M.B., Dore, G.G., Eds.; SAGE Publishing: New Delhi, India, 2020; p. 95. ISBN 978-93-5388-362-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, F.; Shen, B. Progress and Prospects of China in Implementing the Goal 14 of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Chin. J. Urban Environ. Stud. 2019, 07, 1940006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinan, H.; Bailey, M. Understanding Barriers in Indian Ocean Tuna Commission Allocation Negotiations on Fishing Opportunities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 6665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scanlon, Z. Incorporating Taiwan in International Fisheries Management: The Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement Experience. Ocean. Dev. Int. Law 2017, 48, 35–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Geest, C. Redesigning Indian Ocean Fisheries Governance for 21st Century Sustainability. Glob. Policy 2017, 8, 227–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welsford, D.; Ziegler, P.; Maschette, D.; Sumner, M. Bottom Fishing Impact Assessment (BFIA) for Planned Fishing Activities by Australia in the Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFA) Area–2020 Update. In Proceedings of the 5th Meeting of the Southern Indian Ocean Fisheries Agreement (SIOFA) Scientific Committee, Phuket, Thailand, 25–29 June 2020; pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- van der Elst, R.P.; Groeneveld, J.C.; Baloi, A.P.; Marsac, F.; Katonda, K.I.; Ruwa, R.K.; Lane, W.L. Nine Nations, One Ocean: A Benchmark Appraisal of the South Western Indian Ocean Fisheries Project (2008–2012). Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2009, 52, 258–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ALI, G. China–Pakistan Maritime Cooperation in the Indian Ocean. Issues Stud. 2019, 55, 1940005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dereynier, Y.L. Evolving Principles of International Fisheries Law and the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission. Ocean. Dev. Int. Law 1998, 29, 147–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, R.; Oozeki, Y.; Takasaki, K.; Saito, T.; Uehara, S.; Miyahara, M. Transshipment Activities in the North Pacific Fisheries Commission Convention Area. Mar. Policy 2022, 146, 105299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J.S. Fur Seals and the Bering Sea Arbitration. J. Am. Geogr. Soc. N. Y. 1894, 26, 326–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aqorau, T. Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2009, 24, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, W.G.; Hare, S.R. Effects of Climate and Stock Size on Recruitment and Growth of Pacific Halibut. N. Am. J. Fish. Manag. 2002, 22, 852–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.J.; Croston, J.L. WTO Scrutiny v. Environmental Objectives: Assessment of the International Dolphin Conservation Program Act. Am. Bus. LJ 1999, 37, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noakes, D.J.; Fang, L.; Hipel, K.W.; Kilgour, D.M. The Pacific Salmon Treaty: A Century of Debate and an Uncertain Future. Group Decis. Negot. 2005, 14, 501–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The 1992 Convention for the Protection of Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (Paris), 22 September 1992, Came into Force on 25 March 1998, (32 ILM (1992)), 1068. Available online: https://www.oecd-nea.org/jcms/pl_29147/convention-for-the-protection-of-the-marine-environment-of-the-north-east-atlantic-ospar-convention#:~:text=The%20OSPAR%20Convention%20is%20the,restore%20marine%20areas%20which%20have (accessed on 22 January 2024).

- Wilewska-Bien, M.; Anderberg, S. Reception of Sewage in the Baltic Sea—The Port’s Role in the Sustainable Management of Ship Wastes. Mar. Policy 2018, 93, 207–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koen-Alonso, M.; Pepin, P.; Fogarty, M.J.; Kenny, A.; Kenchington, E. The Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization Roadmap for the Development and Implementation of an Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries: Structure, State of Development, and Challenges. Mar. Policy 2019, 100, 342–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, K.J.; Hansen, S.C.; Gale, J. Overview of Discards from Canadian Commercial Groundfish Fisheries in Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization (NAFO) Divisions 4X5Yb for 2007–2011; Canadian Science Advisory Secretariat (CSAS): Moncton, NB, Canada, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Chiriboga, O.R. The American Convention and the Protocol of San Salvador: Two Intertwined Treaties: Non-Enforceability of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights in the Inter-American System. Neth. Q. Hum. Rights 2013, 31, 159–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namnum, S. The Inter-American Convention for the Protection and Conservation of Sea Turtles and Its Implementation in Mexican Law. J. Int. Wildl. Law Policy 2002, 5, 87–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanning, L.; Mahon, R.; McConney, P. Applying the Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) Governance Framework in the Wider Caribbean Region. Mar. Policy 2013, 42, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gormley, W.P. Convention for the Protection of the Mediterranean Sea against Pollution. Environ. Policy Law 1976, 2, 45–47. [Google Scholar]

- Kirk, E.A.; Popattanachai, N.; Ibe, C. Convention on the Protection of the Black Sea Against Pollution 1992. In Elgar Encyclopedia of Environmental Law; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2017; pp. 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Y.-C. Chinese Legislation in the Exploration of Marine Mineral Resources and Its Adoption in the Arctic Ocean. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2019, 168, 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serdy, A. The Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean: An Overview. Ocean. Yearb. Online 2019, 33, 401–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, M. The Convention on the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources: A Five-Year Review. Int. Comp. Law Q. 1989, 38, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Convey, P.; Peck, L.S. Antarctic Environmental Change and Biological Responses. Sci. Adv. 2019, 5, eaaz0888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.-C. The Sino-Canadian Exchange on the Arctic: Conference Report. Mar. Policy 2019, 99, 76–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akaso, A.A. Oceans Policy as a Sustainable Tool for the Regulation of the Marine Environment. Int’l J. Adv. Leg. Stud. Gov. 2012, 3, 71–77. [Google Scholar]

- Aukes, E.; Lulofs, K.; Bressers, H. (Mis-)Matching Framing Foci: Understanding Policy Consensus among Coastal Governance Frames. Ocean. Coast. Manag. 2020, 197, 105286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.J. Book Review: Kum-Kum Bhavnani, John Foran, Priya A. Kurian and Debashish Munshi, Climate Futures: Reimagining Global Climate Justice. Prog. Dev. Stud. 2021, 23, 14649934211028718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butt, M.J.; Zulfiqar, K.; Chang, Y.-C. The Belt and Road Initiative and the Law of the Sea, Edited by Keyuan Zou. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 2021, 1, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chomariyah. Oceans Governance: Implementation of the Precautionary Approach to Anticipate in Fisheries Crisis. Procedia Earth Planet. Sci. 2015, 14, 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).