Abstract

Pakistan hosts over 1.4 million Afghan refugees and is facing extreme challenges in accomplishing the UN’s refugee pacts and 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The inflow and longer stay of refugees in the host country may affect the local population’s socio-economic conditions. However, not all refugees are a “burden” to the host economy. Some refugees can contribute positively to the local economy given the opportunity. This study investigates the leading hurdles to establishing businesses for refugees to provide a different perspective to policymakers and scholars in achieving refugee integration. Through a thematic analysis of interviews conducted with Afghan entrepreneurial refugees, this study identifies ten hurdles and five opportunities they face while conducting business in Pakistan. Fuzzy Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (FSWARA) prioritizes the central theme, i.e., a lack of policies, among other hurdles, by allocating weights. Hypotheses on hurdles and opportunities are built and tested through multiple regression analysis (MRA). All the hypotheses on hurdles and three on opportunities are accepted. This study highlights the importance of a comprehensive framework for entrepreneurial refugees for their smooth integration into Pakistani society. This study helps policymakers and scholars identify the main barriers for refugee entrepreneurs in Pakistan.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

The growing number of refugees poses a significant threat to host countries not merely in terms of security but also economically [1]. There are 35.3 million refugees worldwide, and 69% are from just five countries [2]. Most refugees and immigrants take shelter in developing countries. United Nations (UN) statistics show that about 86% of refugees reside in developing countries. The host countries must provide the refugees with food, accommodation, and other commodities. These countries hardly manage to fulfill their fundamental necessities, and the influx of refugees is a great challenge for them to tackle.

However, it is important to highlight that all refugees are not a burden on the host country. Some refugees actively participate in entrepreneurial activities and innovations that benefit the host country [3]. Therefore, the entrepreneurial engagement of refugees may pave a path for their integration into the host society, thus lessening the onus on the recipient country. Furthermore, those refugees with capital or skills set up their businesses in the country where they take shelter. Refugees’ entrepreneurial activities also benefit their communities [4]. Enterprises run by refugees create jobs for them and others in the area while battling prejudice and unfavorable attitudes toward migrants [5].

1.2. Entrepreneurial Refugees and Their Integration

According to the United States Small Business Administration, immigrant entrepreneurs are much more likely to launch a business than native-born residents. Moreover, immigrants have been creating jobs in regions where they are needed [6]. Refugees have no other better options than to engage in business as they have difficulty acquiring employment for which they do not fulfill the necessary criteria. Further, they may also lack the required language proficiency. So, they are more likely to step into startups where they take significant risks than locals [7].

Turkey hosts the world’s largest community of refugees. About a 3.7 million Syrian refugees are residing in Turkey [8]. All of the refugees are not a burden on the host state’s economy, but rather, play a significant role in Turkey’s development. A Turkish think tank revealed that Syrian refugees cum entrepreneurs provide livelihoods to about 7% of their respective compatriots, and they can fill the shortage of cheap labor and tackle future demographic issues. Considering a similar situation, Germany allowed Syrian immigrants to stay and work there. They introduced the “Wir Zusammen” slogan, meaning “We together” for refugee integration [9]. However, integration through businesses and entrepreneurial activities is a recent method of sustainable settlement in host countries. Their engagement in entrepreneurship is not only in the host’s interest but also in that of the origin country.

The integration of refugees has many interpretations, but more precisely, it targets legal, economic, and socio-cultural perspectives. It is regarded as a two-way process because, on the one hand, it requires refugees to adopt the new environment, and on the other hand, it demands that the host community facilitate them. The effective integration of migrants is crucial for regional development. Migrants often settle in cities to acquire relevant services, social networks, and employment opportunities and contribute their talents and cultural diversity to local growth. In several nations, rural communities seek new people to revitalize their economic and demographic foundations and may seek to accept more migrants. In this regard, regional economic development policies might consider the significant contribution migrants can make to a local economy. A policy consultation program organized by Georgetown University concludes that Turkey, Uganda, and Colombia dealt with refugees better in terms of integrating them into their society.

The 1951 UN Convention is about the status of refugees, and its 1967 Protocol focuses substantially on refugees’ integration. Article 34 of the Convention calls on states to support refugees’ “assimilation and citizenship”. The Convention enumerates social and economic rights aiming to aid integration. The logic behind the architecture of the Convention is that refugees should eventually be allowed to possess a broader range of rights as their affiliation and links with the host state strengthen. In this respect, the 1951 Convention provides refugees with a firm foundation for gradually regaining the social and economic independence necessary to move on with their lives.

1.3. Entrepreneurial Afghan Refugees and Their Integration into Pakistan

A refugee faces several hurdles if they want to engage in entrepreneurial activity or start a business in the host country. Depending upon the country’s demography, rules, and regulations, migrants face bulk requirements and sometimes vagueness in the policies for inhabiting the host country. Developing countries like Iran, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Lebanon, and Sudan do not have proper refugee policies [10]. Thus, this creates trouble for the migrants who are already escaping problems from their country of origin. Furthermore, these hurdles and barriers of a weak policy system restrict the integration process.

Pakistan is one of the world’s leading host countries for refugees. Pakistan hosts the largest community of Afghans of about 1.4 million registered people and 1 million unregistered refugees who started migrating into their territory in 1979. During that time, the Government of Pakistan (GOP) accepted refugees on a humanitarian basis, and the Foreigners Act was also not applicable to them [11].

The Government of Pakistan (GOP) is not a signatory to the UN’s 1951 convention and protocol of 1967 for refugees [12]. With time, policies changed, but the matter of refugees’ legal status is still lingering. Thus, refugees are suffering due to the vagueness in the laws of the GOP. Refugees cannot earn a livelihood or start their registered businesses due to loopholes in rules and regulations. Pakistan’s policy on refugee registration has been volatile. Refugees have been issued Proof of Registration (POR) and Afghan Citizen cards (ACC) at various times, but there are still many who remain unregistered. Registering Afghan refugees with no legal status in Pakistan will ultimately help the host country as they will contribute to the economy [13].

Refugees in camps face dire challenges, including inadequate shelter, a lack of basic services, the absence of a proper legal framework, and limited employment opportunities. For refugees, the possession of Proof of Registration (POR) cards does not ensure access to stable employment [14]. Because of the lack of recognition and constantly changing policies, refugees find it difficult to secure traditional jobs. As a result, they are often compelled to engage in small and non-traditional businesses to make ends meet. While pursuing these businesses, they must compete with local traders and entrepreneurs who have more extensive opportunities and smoother pathways for their products.

Some refugees resorted to bribing personnel at Pakistan’s National Database Regulatory Authority (NADRA) to obtain illegal documents, but this ultimately benefits neither the refugees nor Pakistan [15]. Without a valid card, obtaining legal housing or shop leases becomes challenging. Moreover, lacking a Proof of Registration card or visa makes it difficult for individuals to acquire SIM cards or establish bank accounts [16]. Afghan traders encounter obstacles at the borders due to the actions of Pakistani officials. These officials impose additional taxes on top of the standard levies, often using this as a tactic to solicit bribes right on the spot. Penalizing Afghan merchants for personal gain not only harms state revenue but also creates inefficiencies. Furthermore, customs and intelligence officials employ delaying tactics under the guise of clearance and screening processes, seeking bribes from transporters and drivers [17]. Due to the uncertain policies, limited or non-existent registration facilities, disruptions by customs and other security forces at borders, challenges during transportation within the country, the absence of bank account facilities, and a lack of legal frameworks for land purchase or leasing, refugee entrepreneurs in Pakistan encounter significant obstacles in conducting their business activities.

To thoroughly examine the challenges and opportunities in the Pakistani business landscape, this research employs a comprehensive methodology that integrates both qualitative and quantitative approaches. In the qualitative phase, the study engages in interviews with business owners from the Afghan refugee community. Thematic analysis is then applied to the interview data to extract crucial themes and patterns. Transitioning to the quantitative aspect, this research utilizes the Fuzzy SWARA methodology to allocate weights to the significant themes identified through the thematic analysis. Following this, their validation is carried out through multiple regression analysis (MRA). This multifaceted approach ensures a thorough understanding of the complexities inherent in the business environment under investigation.

Considering the above-stated background, this study has two objectives: Firstly, it explores the obstacles faced by refugees while conducting business in Pakistan. Secondly, the study identifies whether the GOP has managed to remove the hurdles, resulting in more opportunities for refugees. This research adds to the existing literature on barriers that entrepreneurial refugees encounter during their stay in host countries and their respective opportunities. Moreover, it illustrates the looming situation of refugees in Pakistan for researchers and policymakers because of the lack of stern rules and regulations.

2. Literature Review

The integration of refugees remains a hot topic for researchers. Many methods have been identified in studies, and new searches are underway for reliable and durable approaches to the integration of refugees. The number of scholarly articles in top-notch entrepreneurship journals has surged in the last few years [18].

2.1. Concept of Entrepreneurial Refugees

Different researchers define many types of integration. Among them, socio-cultural integration is the mutual relationship between the host country’s refugees and locals [19]. More understanding among them will result in further compatible integration. Public support adds to the sustainability of integration. Similarly, structural integration is about incorporating refugees into educational, residential, and labor markets [20]. According to the European Commission, resilience in integration can be achieved by coordinating responses, health, education, employment, housing, and prior proper preparations.

Moreover, for the integration process to move more quickly, access to the labor market is essential, and routes should be safe, clear, straightforward, and quick. The United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) presented five modules for the socio-economic inclusion of refugees. All the modules are oriented toward entrepreneurship and helping refugees to avoid legal hurdles. A similar study shows highly skilled refugees’ legal and practical barriers while establishing a startup. Moreover, the study recommends that an easily accessible and transparent structure of financial assistance should be made available to refugees [21].

Studies reveal that compared to the native population, refugees have relatively low employment rates and are left behind by other migrant groups with more social capital inside well-established ethnic groupings [22]. Due to a lack of formal proof and unavailability of professional certification, refugees cannot obtain the desired and full advantages of working in the host country [23]. So, such refugees are more inclined toward entrepreneurship to tackle the threat of unemployment and low-wage jobs [24]. The author of [25] shows that 10% of the refugees in their study started their businesses after staying five years in Australia. Deloitte’s [26] survey of 305 refugees from the United Kingdom, Australia, and the Netherlands reports that 32% of respondents were previously business owners before migration. But now, 12% are willing to conduct business in the host country, mainly due to the high risk and lack of support.

The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) categorizes refugee challenges into four groups; institutional level, opportunity, ethnic group level, and individual level. These groups illustrate the hurdles of legal status, business opportunity, discrimination, and a lack of assistance [27]. Because of these barriers, refugees are pushed towards entrepreneurship to feed their families and survive in their new location [28]. Other scholars also termed refugee integration as economic integration. Economic integration means the integration of the labor market. Refugees can earn and partake in entrepreneurial activities as easily as locals [29]. According to academics, structural and socio-cultural integration also impacts migrants’ ability to integrate economically [30]. Entrepreneurs’ unique situations and the host societies’ various social and institutional structures play a vital role in economic integration through entrepreneurship. With the interrelation of socio-economic aspects, a business web can be created, which assists in developing a new social network [31,32].

2.2. The Situation of Afghan Refugees in Pakistan

To start a business, refugee entrepreneurs mainly rely on capital from family or friends, which will smooth the integration process [33]. Family is a top priority for Afghan refugees, among other matters [34]. Integrating refugees into the host society through economic methods is a gradual process. A paper categorizes this process into three stages: (1) entry into the labor market, (2) step-by-step integration, and (3) submerging into society [35]. Moreover, the study also mentioned that the Afghani refugees in Pakistan develop different types of vertical and horizontal capital due a lack of financial and legal support from the Government of Pakistan. After migration, refugees may also face the challenge of developing a new social network in the host country. Moreover, they must adopt different strategies to start a business [36,37].

However, refugees also encounter several significant problems in conducting business. According to the Policy Guide of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), immigrants and refugees face obstacles to starting their businesses because of linguistic and cultural challenges and a lack of financial and social capital. Refugee business owners frequently encounter obstacles relating to their legal status, which may entail not having the ability to work or pursue self-employment. As a result of not being documented, they may face unforeseen forced relocation and its psychological implications with travel restrictions. Immigrants and refugees may also suffer from xenophobia and stigma associated with their legal status in their respective host country [38].

Garnham (2006) [39] states that the most prominent barrier refugee entrepreneurs face is the financial barrier. Other hurdles are hectic legal procedures and lengthy documentation. A study from the ten big markets of Europe states that newcomer refugee entrepreneurs have additional barriers compared to locals. Those obstacles include legal status, a lack of language proficiency, and less information about local markets [40]. Governments’ uncertain and stringent rules and regulations may also pose a threat to the entrepreneurial activities of refugees. A study in Kenya states that specific segments of government policies also obstruct the path of entrepreneurial refugees [41].

Afghan refugees in Pakistan also experience such problems. Pakistan has not yet devised proper, thorough regulation for refugees. They cannot purchase land, are unable to register a company, and cannot have full access to bank accounts and money transfers. Certain newspapers also report lacuna in refugees’ travel, business, identity, and status policies [42]. A report [43] states that Afghan refugees come across the following problems: (1) no proper documentation and government-defined policy, (2) no acquisition of land and property, and (3) no detailed laws about bank accounts and funds transfers. Similarly, the Sustainable Development Policy Institute (SDPI), in its report, states that refugees face difficulty in business due to a lack of credit facilities, informal taxes, inspection, and violence.

For the consolidation of economic growth and the development of effective policies, it is imperative for a country to prioritize entrepreneurship. Babson College in the United States, in collaboration with the London Business School in the United Kingdom, initiated the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) in 1999. The GEM assesses the impact and significance of entrepreneurship on economic development [44]. Entrepreneurship plays a crucial role in mobilizing regional economies, leading to increased employment opportunities, trade, the introduction of new technologies, and innovation in various industries.

A study was conducted to evaluate the entrepreneurial performance of Asian and Oceanian countries using indicators from the GEM. This study employed methods such as Aras, Waspas, and Mairca, integrating the results using the Borda Count method. The results ranked India, Pakistan, and Malaysia lower, indicating that Pakistan, which hosts one of the largest refugee communities, is among the lowest-ranking countries with minimal emphasis on entrepreneurship [45]. This situation not only has implications for local entrepreneurs but also paints a challenging picture for refugee entrepreneurs trying to establish themselves in such an environment. Numerous studies aim to explore the positive correlation between businesses and immigrants, with some utilizing the GEM dataset [46,47]. However, this specific study stands out due to its distinctive approach, incorporating a unique amalgamation of both qualitative and quantitative methodologies.

This literature survey indicates that countries have multiple problems regarding refugees’ entrepreneurial activities. Therefore, the study of entrepreneurial refugees may be undertaken in each country’s context. Furthermore, earlier work did not evidently combine qualitative and quantitative analysis with studying the barriers faced by entrepreneurial refugees in host countries. So, this study, in detail, explores the list of limitations an Afghan refugee faces while having or starting a business in Pakistan. The study is undertaken in two steps. First, this study conducts in-depth interviews of Afghan refugees cum entrepreneurs. Through thematic analysis, the limitations and opportunities in conducting business were thematically determined from the interviews. Researchers still consider thematic analysis worthy and reliable [48]. Afterwards, three essential themes were grouped from the limitations obtained from the thematic analysis, and they were prioritized using Fuzzy Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis (FSWARA). F-SWARA is the latest method to rank criteria, in which experts assign weights according to their perceived importance of the alternative [49].

Further, this study’s novelty lied in the multiple regression analysis (MRA) for hypothesis testing built from limitations and opportunities extracted from the thematic analysis regarding Afghan refugees in Pakistan. MRA is credible in hypothesis testing [50]. Thus, this study contributes to the literature on refugee entrepreneurship and its barriers.

3. Data Collection and Methodology

This study is based on both qualitative and quantitative analysis. For the qualitative analysis, we interviewed entrepreneurial Afghan refugees and inquired about the hurdles and opportunities while conducting business in Pakistan. Then, the main themes were identified by thematic analysis. Further, in the quantitative portion, firstly, Fuzzy SWARA was implied to allocate weights to the main themes extracted from the thematic analysis. Then, hypotheses were built on those hurdles and opportunities, and afterwards tested through MRA. In detail, the step-by-step process of data collection and analysis is explained in the subsequent sections.

3.1. Interviews and Their Thematic Analysis

While numerous studies have explored the positive connection between immigrants and business activities, there is limited research on the challenges faced by refugees in their host countries. The Afghan diaspora is widespread, with a significant presence in Pakistan and Iran. Unfortunately, Afghan refugee businesses in these countries often face instability and inadequate policies, making them vulnerable. We collected primary data to identify and list the obstacles encountered by refugee entrepreneurs in Pakistan, along with the potential opportunities that could arise if these challenges were addressed. Semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect information about the hurdles and the opportunities regarding conducting business in Pakistan. Detailed information about the participants can be found in Table 1. For convenience, an Afghan language interpreter was hired. Questions were asked in both Urdu and Pashto. All the respondents were male and ran their businesses. Many had a Proof of Registration (POR) card and some had an Afghan Citizen card (ACC), while others were unregistered. Refugee entrepreneurs were asked about what barriers they encounter in daily life while conducting routine business in Pakistan.

Table 1.

Interview figures.

Interviewees were purposefully selected based on specific criteria—being entrepreneurs and Afghan refugees in Pakistan. Local assistance was sought to arrange meetings with four Afghan entrepreneurs, two of whom were involved in the truck industry (operating in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa), while the others included a mechanical service provider and a fish shop owner in Afghan Refugee Camp Gandaf, Swabi, KPK. Additionally, 14 entrepreneurs from Karkhano Market in Peshawar, KPK, were selected and interviewed onsite, each engaged in diverse businesses such as selling rugs, clothes, electric appliances, stationery, sports products, and dry fruits. These interviews took place over the last two weeks of May 2022.

The interview process involved the following steps:

- Invitation to participate.

- Explanation of the study’s purpose and major areas of discussion.

- Obtaining consent for recording.

- Ensuring confidentiality of identity, recording, and information.

- Arranging the interview time based on participant availability.

- Conducting the interview with a relaxed atmosphere.

- Expressing gratitude for the participants’ time and valuable insights.

Moreover, what opportunities they would have if the GOP resolved those obstacles was questioned. The interviews were recorded, and participants’ consent was obtained before the recording started. After thoroughly analyzing the recordings, intersecting patterns were identified, and themes were extracted using an inductive approach.

Thematic analysis is a powerful and versatile method still widely used by researchers to construct patterns [51]. In thematic analysis, researchers first familiarize themselves with the obtained data and generate initial codes. Afterwards, themes are developed and refined, and then, given particular titles. Lastly, a report or manuscript is prepared from the extracted themes. In this study, about ten hurdles were extracted after thematic analysis, shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Hurdles extracted through thematic analysis.

3.2. Fuzzy SWARA

In order to prioritize the barriers so that if the Government of Pakistan, relevant departments, Non-Governmental Organizations, and law enforcement agencies want to take notice of the plights of the entrepreneurial community, it would be easy to address their challenges priority wise, we used Fuzzy SWARA. Fuzzy SWARA (Fuzzy Step-wise Weight Assessment Ratio Analysis) is one of the latest methods developed by Violeta Kersuliene and other scholars [52]. It is mainly used for rational decision making [49,53,54]. The main feature of FSWARA is weight allocation by the decision makers [55].

Applying Fuzzy SWARA in this study is unusual, but it served the purpose of prioritizing themes for which gathering data was particularly challenging [56] due to the reluctance of participants to engage in discussions concerning sensitive matters related to Afghan refugees. This hesitancy comes from the fact that law enforcement agencies are part of the subject matter.

The first step of FSWARA is to determine the main factors under study. In this study, the significant factors were obtained by coupling barriers that Afghan refugees encounter while conducting entrepreneurship in Pakistan. A total of ten obstacles were obtained through the thematic analysis of the interviews, shown in Table 2. Then, experts were asked to group those barriers based on their similarity. Experts cumulated these hurdles into three main factors depending upon the similarity of the nature of the problems. The three main themes are a lack of policies (T1), informal taxation (T2), and bribery and corruption (T3).

A five-point Likert scale was developed to rank the main themes and sent to the selected respondents. The questionnaire was also translated into the Pashto language. The survey was disseminated among government officials working with refugees, Afghan entrepreneurs in Pakistan, Scholars from research institutes, and different NGO personnel. Participants were asked to select the most suitable option ranging from very low to very high for the three main factors. A total of twenty-six responses were obtained.

Fuzzy set theory was used to convert linguistic variables into fuzzy numbers. Lofti Asgerzadeh was the first to present this theory in 1965 [57]. It removes the vagueness involved during the collection of data. The linguistic variables and their respective ratings are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Fuzzy set linguistic variables with fuzzy numbers [58].

After transforming linguistic variables into fuzzy triangular numbers, the subsequent step was the evaluation of weights. The subsequent steps were carried out in accordance with the procedure outlined below [52].

Step 1: The results obtained through transforming linguistic variables are ranked again by the decision makers. The three factors are arranged in descending order, depending upon their importance and severity.

Step 2: For average criterion values “tj”, the following Equation (1) is used for calculation.

Here, “tjk” shows the jth criterion ranking for the kth participant, and “r” represents the number of respondents.

Step 3: For the sorting criteria “Sj”, its comparative importance is ascertained according to the expert’s opinion.

Step 4: This step involves the calculation of the coefficient value “Kj”.

Step 5: In this step, Fuzzy recalculated weights are determined, denoted by “qj”.

Step 6: This final step involves the calculation of the respective criteria’s Fuzzy relative weights. It is denoted by “wj”.

3.3. Multiple Regression Analysis (MRA)

Multiple regression analysis (MRA) is integral to many studies based on statistical and numerical data analysis. Moreover, MRA is very much reliable in hypothesis testing. It evaluates the correlation between the selected dependent and independent variables efficiently [59]. A general equation used for regression is given below:

Here, the dependent variable (Y) represents the satisfaction level for the perceived hurdles and opportunities, while the multiple independent variables (X1–Xn) correspond to the actual hurdles and opportunities. The measurement of the dependent variable involved assessing participants’ satisfaction levels through a questionnaire, utilizing a Likert scale to gauge their perspectives on the identified obstacles and the ensuing opportunities after they have been resolved.

For this study, two central hypotheses were constructed, i.e., HA and HB.

HA = Refugees face significant hurdles while conducting business in Pakistan (H1–H10).

HB = The removal of hurdles will result in opportunities (H11–H15).

Both the main hypotheses lead toward multiple sub-hypotheses, shown in Table 4. These hypotheses were built to test the validity of the hurdles and opportunities extracted in the thematic analysis of interviews with the Afghan entrepreneurial refugees stated in the first half of the study. HA and HB were separately tested through multiple regression analysis.

Table 4.

Sub-hypothesis from the main hypotheses, HA and HB.

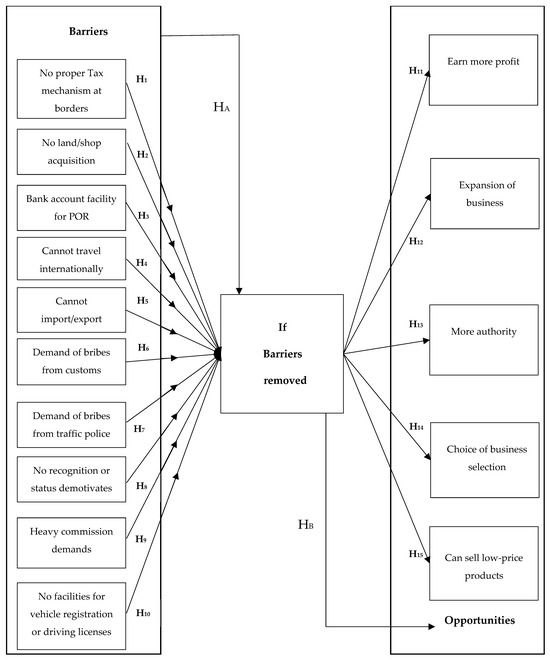

To test these two hypotheses (HA and HB), we formulated two separate equations. On the right side of Equation (6), ( represents the independent variables, signifying the barriers faced by refugees when conducting business in Pakistan. These hurdles are also illustrated on the left side (HA) of Figure 1, i.e., (H1–H10). Further, the independent variables in Equation Seven ( represent the perceived resultant opportunities (H11–H15), as depicted on the right side of Figure 1 (HB). Alpha () and beta () denote the coefficients, while “” represents the error terms, respectively. In both equations, the dependent variables reflect the satisfaction levels associated with the identified hurdles and perceived opportunities, respectively. Data for the dependent variable for both equations were also collected through the survey.

Figure 1.

Theoretical model of hypotheses (HA and HB).

The hypotheses in Table 4 was tested to see whether these hurdles and opportunities could be accepted or rejected through regression analysis.

A total of sixteen Afghan entrepreneurial refugees took part in the survey. For the respondents’ ease of understanding, the questionnaire was converted into the Pashto language. The survey was filled in with our close cooperation with the respondents, as many did not have formal education. The participants’ opinions were obtained using a Likert scale with five points ranging from strongly disagree to strongly agree. We have come across studies that employ a five-point Likert scale in their regression analyses to investigate topics such as immigrants, mental health, and human resources [60,61,62]. The Likert scale is highly reliable and easily understandable [63]. After the responses were recorded, they were interpreted and run through a multiple regression equation through MS-Excel. Data of the hurdles (H1–H10) and opportunities (H11–H15) from the responses were input into Equations (6) and (7), respectively.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Barriers to the Integration of Entrepreneurial Refugees

In the first portion of this research, interviews were carried out with eighteen Afghan refugee entrepreneurs. As refugees, they were questioned about the barriers they encountered while conducting business in Pakistan. Moreover, migrants were asked about possible opportunities if the GOP resolved those barriers. As shown in Table 1, out of eighteen, only nine refugees fully cooperated and responded to all questions from our semi-structured interview. Seven responded partially, and two entrepreneurs abstained from recording the interview because of security concerns. Refugees in their respective host countries fear security agencies because of their unfamiliarity with the country. Furthermore, rules and regulations are strict regarding immigrants and refugees. So, due to fear of deportation, they are reluctant to discuss policy-related matters [64]. Recorded interviews were coded precisely, and central themes were extracted afterwards by decoding them through thematic analysis. We obtained a list of barriers, as presented in Table 2.

One of the hurdles among them is the deficiency of good policies. The GOP (Government of Pakistan) initiates repatriation drives from time to time. They did not want to manage refugees for the long term as the country faces severe economic and security crises. Resultantly, the government never intended to devise a comprehensive policy regarding refugees; thus, it remained highly volatile [65]. Lacuna in the rules and regulations results in no proper taxation mechanism at the border, which gives rise to other barriers, i.e., informal taxation and bribery [13]. Local government representatives ask for the desired amount of taxes from refugees; simultaneously, bribes are also demanded by traffic and customs officers [16].

Similarly, legal status and refugees’ identities also pose a significant obstacle to their way of conducting business. Due to looming deportation and repatriation drives, refugees are reluctant to give importance to registration drives, as if they do, they will be on the list of surveillance of security departments. On the other hand, the limited facilities provided by the government cannot be accessed by refugees because of being unregistered [66]. As fund transfers remain a hot topic for refugee entrepreneurs, unregistered refugees cannot have the opportunity of credit transfer through bank accounts. However, holders of Proof of Registration (POR) cards issued by the GOP can use the credit account facility [67]. But still, its functionality has also succumbed to the government’s changing policies.

4.2. Possible Opportunities after Removal of Barriers for Entrepreneurial Refugees

In recent times, promoting long-term stability in host countries has been achieved through the integration of businesses and entrepreneurial initiatives. Refugees’ participation in entrepreneurship not only provides economic benefits to the host country, but also contributes to its overall prosperity. In accordance with these research findings, it is critical for host country governments to implement well-considered policies that actively support and nurture refugee entrepreneurship. These actions are essential in advancing the social and economic integration of refugees, enabling them to fully leverage their economic potential within the host nation. Given Pakistan’s significant economic challenges, it is crucial for the country to develop policies that promote the integration of refugees and provide support to the entrepreneurial community. These measures can play a pivotal role in bolstering the nation’s economy during these challenging times.

In light of this study, it is imperative that host country governments establish rational policies aimed at actively endorsing and fostering refugee entrepreneurship. These measures are indispensable for enhancing the social and economic integration of refugees and enabling them to maximize their economic contributions to the host nation [68]. In order to alleviate the challenges faced by the entrepreneurial refugee community, it is essential to first identify and assess the primary obstacles they encounter. Yet, to truly empower them and ensure their well-being and satisfaction, the government must also focus on creating opportunities once these obstacles have been successfully addressed. This aligns with our overarching objective of exploring the opportunities that would arise if these hurdles were effectively resolved by governments and relevant authorities.

So, in the same interview, entrepreneurs were asked about the resultant possible opportunities after resolving the barriers. Through thematic analysis, we identified and categorized these opportunities, as depicted in the model presented in Figure 1. According to entrepreneurial refugees, they would be able to engage in a business of their own choice, as currently, they are bound to work in a specific market. The problem is their direct restriction to acquiring shop/land in their name.

Moreover, when they can import/export legally in their name, incur less commission, and face no chances of bribery, this will result in cheap products. Consequently, they were willing to expand their businesses and had hopes of earning more profit. This would help the government generate revenue from refugees instead of spending on them and help them integrate into the host society effectively [69].

4.3. Results of Quantitative analysis

4.3.1. Fuzzy SWARA Results and Discussion

The second part of this study applies the quantitative methods of Fuzzy SWARA and MRA for hypothesis testing. After the experts coupled the hurdles into three main themes, they were assessed by decision makers. The fuzzy set theory then converted the resulting linguistic variables into corresponding fuzzy numbers. The first step involved finding the average values of the main hurdles and listing them in descending order with the help of Equation (1).

Afterwards, the comparative importance of the three main themes of limitations was determined based on the opinions of a pool of Afghan entrepreneurs, denoted by Sj. In the next step, the coefficient value was calculated using Equation (2), represented by Kj. Afterwards, Equation (3) was utilized to find fuzzy recalculated central theme weights. The final step of Fuzzy SWARA was associated with calculating fuzzy relative weights with the help of Equation (4). The results are given in Table 5.

Table 5.

Results obtained through Fuzzy SWARA.

It is evident from the results of the Fuzzy SWARA from Table 5 that T1, i.e., lack of policies, is the most significant theme among the hurdles, with an assigned ultimate weight of (0.84, 0.88, 0.89). Hosting countries have to devise long- and short-term policies whenever refugees are settled in any host country. The immigrant rules and regulations should be proper and systematic to avoid hurdles. With time, due to the United Nations’ resolutions and its Sustainable Development Goals, host countries have to ensure quality of life and normality for refugees with the collaboration of the UN and its associated agencies [59]. Pakistan is not a signatory to the UN’s 1951 refugees convention, nor does it have any national legislation regarding refugees [70]. Additionally, the rules and regulations on the provisional level also have many loopholes, i.e., only POR card holders can lease land/property in their name by signing a deed. At the same time, they cannot purchase judicial stamp paper. POR cards are issued only to the initial migrants of 1979 or refugees with registration proof in Pakistan.

Similarly, they cannot travel to any other country from Pakistan. Entrepreneurs face restrictions on import/export in their name, and then, they have to order products in the name of a Pakistani friend/relative. Moreover, they feel insecure due to the absence of permanent legal status in Pakistan. This raises more significant issues such as obtaining a business license, registering a store, registering as an individual, acquiring any property, studying, public employment, and work permits [35]. Thus, the lack of policies seems to be a significant hurdle for entrepreneurial Afghan refugees.

4.3.2. Results and Discussion on Hypothesis Testing

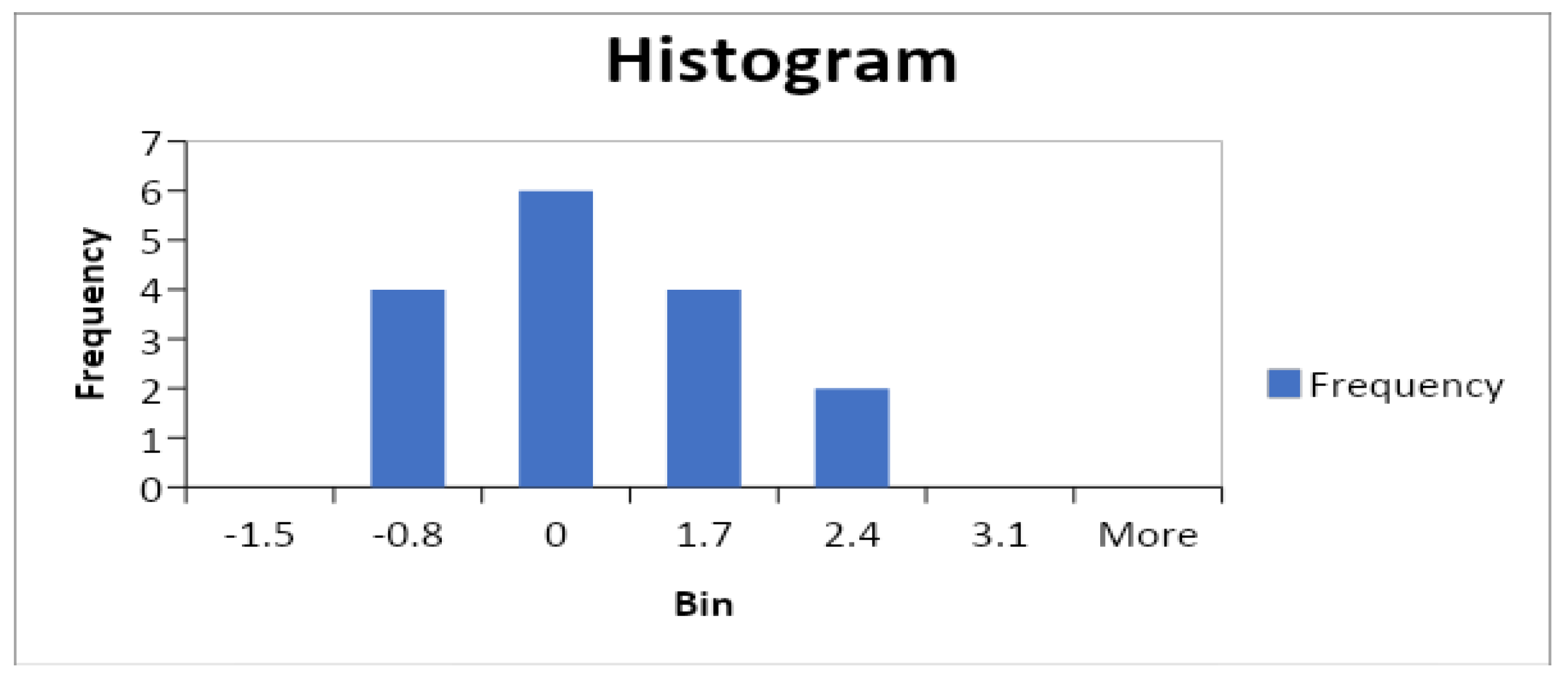

It is generally preferable to gather responses from a large number of participants for multiple regression analysis (MRA). However, we conducted a pilot study in this case, which utilized MRA with only 16 responses. It is worth noting that obtaining a sufficient number of responses posed a challenge as very few refugees were willing to participate in the survey due to their concerns about potential persecution by law enforcement agencies after recording their responses. Instances of applying MRA (multiple regression analysis) with small sample sizes have been observed. There exist studies that advocate for the use of minimal sample sizes. In cases with a limited number of respondents, achieving normally distributed data can be challenging in MRA. In such situations, we assess data normality by examining the residuals of the data [71].

In addition to conducting multiple regression analysis (MRA), we also executed commands for residuals and standardized residuals in MS-Excel, examining their normality through a histogram (Appendix A). The resulting residual graph demonstrates that the data follows a perfectly normal distribution. Further, Shapiro–Wilk Test values also confirm the normality of residuals (Table A1). Table 4 shows the built-up hypothesis upon the hurdles and possible opportunities, whereas Table 6 exhibits the results from MRA. Cronbach’s alpha was used to measure the internal consistency of the questionnaire [72]. A value of 0.8 or above for Cronbach’s alpha showed a perfect level [73]. The results of this study indicate a high level of internal consistency in the questionnaire, which was developed based on the hurdles and opportunities identified through thematic analysis. This is reflected in the Cronbach’s alpha score (0.85 and 0.88), which signifies strong internal reliability.

Table 6.

Results of hypotheses after analyzing them through MRA (acceptable p-value range = 0.10).

Furthermore, from Table 7 the t-statistic provides support to measure the null hypothesis. It describes whether there is a difference between the average of the two groups or not; moreover, it tells us about their relationship. Any t-value greater than +2 or smaller than −2 is generally acceptable [74]. Here, in the results of this study’s hypotheses, HA has all the values in the acceptable region, whereas for HB, the two results are therefore rejected. Table 6 shows the overall significance of both hypotheses, i.e., HA and HB. The more the value of significance is reduced, the better the fit for the model proposed [75]. The adjusted R2 is the proportion of the dependent variable’s variance explained by the variability in the independent variables. From Table 6 the substantial acceptable range is above 0.75, where both the hypotheses’ values in this study show strong results, i.e., 0.86 and 0.84, respectively. The p-value is very much necessary for testing the statistical significance of the hypotheses. Similarly, regarding the p-value, the acceptable error value selected was 0.10. Several scholars have computed results using this value of error by stating that the limit of the error depends upon the nature of the study [76]. For the constructed hypotheses in Table 4, all were accepted for HA (H1–H10), while two hypotheses (H13, H14) of HB (H11–H15) were rejected.

Table 7.

Hypotesis testing and confirming.

Concerning the identified hurdles, the coefficients for H3, H5, H6, and H9 exhibit a negative trend. This can be attributed to the fact that during their residence in the host country, Afghan refugees were once granted the opportunity to open a bank account, which was subsequently restricted following a change in the relevant government. Additionally, the import and export processes necessitate proper documentation, a requirement that the majority of refugees lack. Exploiting this deficiency, there is a prevalent demand for hefty commissions and bribes. Within the identified opportunities, only H13 exhibits a negative trend. This is attributed to the perception that, even if the challenges faced by Afghan refugees are addressed, there is still a prevailing belief that their autonomy in business matters will continue to be suppressed.

As stated earlier, Pakistan is not a party to the 1951 Convention on the status of refugees, nor does it adhere to the United Nations’ provisions on refugees. Therefore, refugees in Pakistan are currently treated under the Foreigners Act, 1946. In close cooperation with the Government of Pakistan, the UNHCR established an agreement in 1993. According to this accord, Pakistan will give refugees status and accept asylum applications. Additionally, it allows them to stay as long as it takes for a compatible solution to be obtained for the crisis. In 2007, the GOP started a registration drive by giving refugees Proof of Registration (POR) cards, giving them a temporary legal stay in Pakistan (UNHCR (2022), Asylum System in Pakistan. [Online] Available at: https://bit.ly/3P7UmII (accessed on 10 August 2022)). However, this card has limited facilities, and about 1 million Afghan refugees are still unregistered. Though Pakistan is committed to the UN’s 2030 Sustainable Development Goals, refugees are left behind [77]. Subsequently, lacking national legislative framework and turning a blind eye to ground-level policies have caused grave suffering for refugees and citizens.

Afghan refugees are the largest among the migrant communities in Pakistan. After the halting of a significant portion of financial assistance by the GOP and UNHCR, refugees have struggled to survive [78]. Alternatively, they have started joining informal labor markets, service providers, the transportation industry, the catering industry, and retailers. Entrepreneurship is the fastest way to integrate into the host society without burdening the economy. Thus, it requires comprehensive regulation, which Pakistan lacks, which causes great hurdles for refugees.

Consequently, under the acceptance of all hypotheses of HA, all barriers identified are accepted. Entrepreneurial refugees cannot lease land/property in their name, even for commercial purposes. They must ask a relative/friend who is a Pakistan nationality holder to sign a deed on official stamped paper. Moreover, air travel restrictions add fuel to the fire, as refugees must go back to Afghanistan if they want to go to any other country for business dealings. Similarly, entrepreneurs have to bear significant losses in paying heavy commissions to brokers if they want to import/export products. While procuring products, they have to undergo bribery and corruption from the traffic police and customs officers. POR card holders have limited access to a credit facility, and the fear of account closure looms. POR cards do not grant any substantial opportunities for refugees.

However, according to the results of the Hb hypothesis, if the GOP resolves these hurdles, refugees will enjoy greater profits and business expansion and can sell cheap products. In contrast, hypotheses H13 and H14 are rejected because refugees will still have limited authority over their businesses and fewer choices of business selection. Developing countries can only allow this much to accommodate refugees. Such settlements and systematic rules are possible, as evident in Syrian refugees residing in Turkey [69]. Although the laws are well defined, and the government of Turkey supports Syrian entrepreneurial refugees very much, they still have limited options, and central authority belongs to the government institutions [79]. Thus, Pakistan needs to work from this perspective toward the economic integration of refugees by reforming the existing system and making specific policies regarding refugees, especially for refugee entrepreneurs.

5. Conclusions

As the world is moving towards more sustainability, countries are striving to achieve the 2030 Sustainable development Goals (SDGs) set by the United Nations. The refugee crisis remains an unresolved matter for most developing countries. The economic integration of refugees is supposed to be the most compatible solution to the problem, which is also a vital part of the SDGs. Unfortunately, underdeveloped countries host 86% of the world’s refugees, along with worsening economic and security conditions. Yet, the UN compels host countries to meet their criteria for refugee protocols and its 1951 Refugee Convention. Pakistan has hosted the largest community of Afghan refugees since 1979. Not being a part of the UN’s Refugee Convention and protocols, residing refugees encounter several difficulties. The refugee trouble spiked when the European Union and UN slashed funds of the UNHCR Pakistan. As a result, refugees must undertake entrepreneurial activities to make ends meet.

However, Pakistan lacks a comprehensive legal framework for refugees on the National level. Most of the refugees do not have proper documentation and authorized status. In such circumstances, entrepreneurial refugees come across several barriers. This study interviewed entrepreneurial refugees to ascertain the obstacles they face in Pakistan’s daily routine. Furthermore, they were asked about the possible resultant opportunities if those barriers were to be resolved. This study identifies ten barriers and five opportunities through thematic analysis. One significant hurdle for refugee entrepreneurs is the lack of well-defined policies in Pakistan. The government, due to economic and security crises, periodically initiates repatriation efforts without a long-term refugee management plan, resulting in a volatile policy environment. This policy gap leads to informal taxation and bribery at the border, with local authorities and customs officers demanding taxes and bribes. Additionally, refugee entrepreneurs face challenges related to legal status and identity as they fear surveillance during registration drives linked to deportation efforts. Limited government-provided facilities are inaccessible to unregistered refugees, impacting their access to financial services. While Proof of Registration (POR) card holders can access credit accounts, this privilege is subject to government policy changes. After using Fuzzy SWARA, the central theme of the lack of a policy framework was ranked first. This supports the main hurdles of refugees while conducting business. Similarly, multiple regression analysis (MRA) was used to check the hypothesis built on the ten hurdles and five opportunities. The results concluded that all the hurdles identified were accepted, and two opportunities were rejected. If the GOP successfully addresses these obstacles, refugees stand to benefit from increased profitability, expanded business opportunities, and the ability to offer more affordable products. However, it is important to note that two hypotheses were rejected, as refugees may still encounter limitations in terms of business autonomy and choices in business selection. This study suggests that Pakistan must formulate comprehensive national legislation for refugees. As a difficult economic situation is looming in Pakistan; in such a time, if the GOP takes steps to improve policies regarding refugees’ entrepreneurial activities, it will be beneficial for both stakeholders.

Future studies should focus on pinpointing challenges faced by host governments regarding refugees. These inquiries should offer specific insights to ensure a thorough understanding. Recommendations should strike a balance, addressing the concerns of both host governments and refugees.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.T., M.S. and Y.A.; methodology H.T., M.S. and Y.A.; software, H.T., M.S. and Y.A.; validation, H.T., M.S., Y.A., M.G.-F. and Á.C.-K.; formal analysis, Y.A.; investigation, Á.C.-K.; resources, H.T., Y.A., M.G.-F. and Á.C.-K.; data curation, H.T., M.S., Y.A., M.G.-F. and Á.C.-K.; writing—original draft preparation, H.T., M.S., Y.A., M.G.-F. and Á.C.-K.; writing—review and editing, H.T., M.S., Y.A., M.G.-F. and Á.C.-K.; visualization, Á.C.-K. supervision, Á.C.-K. and M.G.-F.; project administration, Á.C.-K. and M.G.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Results from Shapiro–Wilk test.

Table A1.

Results from Shapiro–Wilk test.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| p-value | 0.2056 |

| W | 0.9254 |

| Sample size (n) | 16 |

| Average () | 6.25 × 10−11 |

| Median | −0.7336 |

| Sample standard deviation (S) | 2.5429 |

| Sum of squares | 96.9921 |

| b | 9.4738 |

| Skewness | 0.7801 |

References

- Ali, Y.; Sabir, M.; Muhammad, N. Refugees and host country nexus: A case study of Pakistan. J. Int. Migr. Integr. 2019, 20, 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN Refugee Agency. 108.4 Million People Worldwide Were Forcibly Displaced. 2023. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/about-unhcr/who-we-are/figures-glance (accessed on 12 October 2023).

- Nathan, M.; Lee, N. Cultural diversity, innovation, and entrepreneurship: Firm-level evidence from London. Econom. Geogr. 2013, 89, 367–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkongolo-Bakenda, J.M.; Chrysostome, E.V. Exploring the organizing and strategic factors of diasporic transnational entrepreneurs in Canada: An empirical study. J. Int. Entrep. 2020, 18, 336–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez Pineiro, O.M. How Business Incubators Can Facilitate Refugee Entrepreneurship and Integration—UNHCR Innovation. 2017. Available online: https://www.unhcr.org/innovation/how-we-can-use-business-incubators-for-refugee-integration/ (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Sundararajan, M.; Sundararajan, B. Immigrant capital and entrepreneurial opportunities. Entrep. Bus. Econ. Rev. 2015, 3, 29–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Middermann, L.H. Do immigrant entrepreneurs have natural cognitive advantages for international entrepreneurial activity? Sustainability 2020, 12, 2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNHCR. Proof of Registration Card (PoR)—UNHCR Pakistan. 2022. Available online: https://help.unhcr.org/pakistan/proof-of-registration-card-por/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Müller, T.R. Reshaping conceptions of citizenship? German Business sector engagement and refugee integration. Citizsh. Stud. 2021, 25, 409–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandre, L.; Salloum, C.; Alalam, A. An investigation of migrant entrepreneurs: The case of Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Int. J. Entrep. Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1147–1164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Watch. Pakistan Coercion, UN Complicity: The Mass Forced Return of Afghan Refugees. 2016. Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2017/02/13/pakistan-coercion-un-complicity/mass-forced-return-afghan-refugees (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Zieck, M. The Legal Status of Afghan Refugees in Pakistan, a Story of Eight Agreements and Two Suppressed Premises. Int. J. Refug. Law 2018, 20, 253–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cone, D.; Khan, S. They Left Us Without Any Support’ Afghans in Pakistan Waiting for Solutions. Refug. Int. 2023. Available online: https://d3jwam0i5codb7.cloudfront.net/wp-content/uploads/2023/07/Pakistan_July2023_R-1.pdf (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Riaz, J.; Qureshi, S.N. A socio-legal analysis of refugees’ response framework in Pakistan. J. Int. Aff. 2023, 6, 688–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, N. Afghan Refugees in Pakistani English Dailies: In Context of Peace Journalism. J. Dev. Soc. Sci. 2023, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amnesty International. Pakistan: Afghan Refugees Harassed, Jailed And Forced To Pay Bribes—New Testimonies. Amnesty Int. 2023. Available online: https://www.amnesty.org.uk/press-releases/pakistan-afghan-refugees-harassed-jailed-and-forced-pay-bribes-new-testimonies (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Gul, I. How Pakistan Lost Potential Afghan Investments? Express Trib. 2022. Available online: https://tribune.com.pk/story/2383957/how-pakistan-lost-potential-afghan-investments (accessed on 16 September 2023).

- Shepherd, D.A.; Williams, T. Entrepreneurship responding to adversity: Equilibrating Adverse Events and Disequilibrating Persistent Adversity. Organ. Theory 2020, 1, 2631787720967678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beckers, P.; Blumberg, B.F. Immigrant entrepreneurship on the move: A longitudinal analysis of first- and second-generation immigrant entrepreneurship in the Netherlands. Organ. Strategy Enterpreneurship 2013, 25, 654–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rusinovic, K. Dynamic Entrepreneurship; Amsterdem University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2006; Available online: www.imiscoe.org (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- de Lange, T.; Berntsen, L.; Hanoeman, R.; Haidar, O. Highly Skilled Entrepreneurial Refugees: Legal and Practical Barriers and Enablers to Start Up in the Netherlands. Int. Migr. 2021, 59, 74–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarvimaki, M. Labor Market Integration of Refugees in Finland. VATT Res. Rep. 2017, 185. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2921095 (accessed on 26 July 2022). [CrossRef]

- Wauters, B.; Lambrecht, J. Barriers to Refugee Entrepreneurship in Belgium: Towards an Explanatory Model. J. Ethn. Migr. Stud. 2008, 36, 895–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rengs, B.; Kopf, J.; Buber-Ennser, I.; Kohlenberger, J.; Hoffmann, R.; Soder, M.; Gatterbauer, M.; Themel, K. Labour Market Profile, Previous Employment and Economic Integration of Refugees: An Austrian Case Study; Vienna Institute of Demography Working Paper; Austrian Academy of Sciences (ÖAW), Vienna Institute of Demography (VID), Vienna: Vienna, Austria, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legrain, P. Refugees Work: A Humanitarian Investment that Yields Economic Dividends. 2016. Available online: https://static1.ara.cat/ara/public/content/file/original/2016/0518/13/informe-refugees-work-a-humanitarian-investment-that-yields-economic-dividends-84875f1.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Betts, A.; Streck, O.; Geervilet, R.; MacPherson, C. Talent Displaced The Economic Lives of Syrian Refugees in Europe. Refugees Study Centre. Deloitte. 2017. Available online: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/talent-displaced-syrian-refugees-europe.pdf (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Chliova, M.; Farny, S.; Salmivaara, V. Supporting Refugees In Entrepreneurship. Prepared for the OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338147136_Supporting_refugees_in_entrepreneurship (accessed on 26 July 2022).

- Mawson, S.; Kasem, L. Exploring the entrepreneurial intentions of Syrian refugees in the UK. Int. J. Entrepreneurial Behav. Res. 2019, 25, 1128–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bevelander, P. Integrating Refugees Into Labor Markets; IZA World Labor: Bonn, Germany, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloosterman, R.C. Matching opportunities with resources: A framework for analysing (migrant) entrepreneurship from a mixed embeddedness perspective. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2010, 22, 25–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marko, V.; Bunar, N. State Assisted Integration: Refugee Integration Policies in Scandinavian Welfare States: The Swedish and Norwegian Experience. J. Refug. Stud. 2010, 23, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, S.Y.; Phillimore, J. Refugees, Social Capital, and Labour Market Integration in the UK. Sociology 2014, 48, 518–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gericke, D.; Burmeister, A.; Löwe, J.; Deller, J.; Pundt, L. How do refugees use their social capital for successful labor market integration? An exploratory analysis in Germany. J. Vocat. Behav. 2018, 105, 46–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blood, P.R. Afghanistan, A Country Study. Blackmask, 2002. Available online: http://public-library.uk/ebooks/10/35.pdf (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Zehra, K.; Usmani, S. Not without family: Refugee family entrepreneurship and economic integration process. J. Enterprising Communities 2021, 17, 158–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harima, A.; Elo, M.; Freiling, J. Rich-to-poor diaspora ventures: How do they survive? Int. J. Entrep. Small Bus. 2016, 28, 391–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bizri, R.M. Refugee-entrepreneurship: A social capital perspective. Entrep. Reg. Dev. 2016, 29, 847–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. Policy Guide on Entrepreneurship for Migrants and Refugees. 2018. Available online: https://unctad.org/system/files/official-document/diae2018d2_en.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Garnham, A. Refugees and the entrepreneurial process. Labour Employ. Work 2006, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Human Safety Net. Refugee Entrepreneurs. 2021. Available online: https://www.thehumansafetynet.org/programmes/for-refugee/refugee-entrepreneurs (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Luseno, T.; Kolade, O. Barriers and Opportunities for Refugee Entrepreneurship in Africa: A Social Capital Perspective. Palgrave Handb. Afr. Entrep. 2022, 407–435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gul, I. DWoes of Afghan Refugees and Businessmen. Daily Times. 2019. Available online: https://dailytimes.com.pk/511976/woes-of-afghan-refugees-and-businessmen/ (accessed on 27 July 2022).

- Kuschminder, K.; Dubov, T. Moral Exclusion, Dehumanisation, and Continued Resistance to Return: Experiences of Refused Afghan Asylum Seekers in the Netherlands. Geopolitics 2023, 28, 1057–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, J.P.R.; Gozun, B.C. Pursuing Venture Growth through External Participation among Entrepreneurs in the Philippines: Evidence from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. J. Entrep. Innov. Emerg. Econ. 2023, 23939575231169905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szymczyk, K.; Bağcı, H.; Kaygın, Y.C.; Şahin, D. A Comparison of the Entrepreneurial Performance of Asian-Oceanian Countries via the Multi-Criteria Decision-Making Techniques of Critic, Aras, Waspas, Mairca and Borda Count Methods. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2023, 20, 65–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-Romero, R. Businesses create more jobs in countries with higher share of immigrants because of skill complementarity. J. Glob. Entrep. Res. 2023, 13, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellalage, N.H.; Fernandez, V.; Bui, T.Q.T. Immigration and entrepreneurship: Is there a uniform relationship across countries? Int. Rev. Econ. Financ. 2023, 85, 270–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castleberry, A.; Nolen, A. Thematic analysis of qualitative research data: Is it as easy as it sounds? Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2018, 10, 807–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Perçin, S. An integrated fuzzy SWARA and fuzzy AD approach for outsourcing provider selection. J. Manuf. Technol. Manag. 2019, 30, 531–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irfan, E.; Yousaf, A.; Muhammad, S. Analysing role of businesses’ investment in digital literacy: A case of Pakistan. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 2022, 176, 121484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiger, M.E.; Varpio, L. Thematic analysis of qualitative data: AMEE Guide No. 131. Med. Teach. 2020, 42, 846–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keršuliene, V.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Turskis, Z. Determining a rational dispute resolution method using a new criterion weighting. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2010, 11, 243–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgács, A.; Lukács, J.; Horváth, R. The Investigation of the Applicability of Fuzzy Rule-based Systems to Predict Economic Decision-Making. Acta Polytech. Hung. 2021, 18, 97–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tesic, D.; Delibasic, B.; Bozanic, D.; Lojic, R.; Pamucar, D.; Balassa, B.E. Application of the Fucom-Fuzzy Mairca Model in Human Resource Management. Acta Polytechn. Hung. 2023, 20, 231–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardani, A.; Kazimieras, E.K.; Zainab, K.; Norhayati, Z.; Ahmad, J.; Khalil, N.; Khoshnoudi, M. A review of multi-criteria decision-making applications to solve energy management problems: Two decades from 1995 to 2015. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2017, 71, 216–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdağoğlu, G.; Özdağoğlu, A.; Damar, M. Identifying and prioritising process portfolio for sustaining an effective business process management lifecycle. J. Multi-Criteria Decis. Anal. 2023, 30, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets. 1965. Available online: https://www-liphy.univ-grenoble-alpes.fr/pagesperso/bahram/biblio/Zadeh_FuzzySetTheory_1965.pdf (accessed on 29 July 2022).

- Achkasova, S. Implementation the Fuzzy Modeling Technology by Means of fuzzy TECH Into the Process of Management the Riskiness of Business Entities Activity. East. -Eur. J. Enterp. Technol. 2018, 5, 39–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uyanık, G.K.; Güler, N. A Study on Multiple Linear Regression Analysis. Procedia Soc. Behav. Sci. 2013, 106, 234–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gottlob, A.; Boomgaarden, H. Risk Propensity, News Frames and Immigration Attitudes. Int. J. Commun. 2022, 16, 2174–2197. [Google Scholar]

- Durden, E.; Pirner, M.C.; Rapoport, S.J.; Williams, A.; Robinson, A.; Forman-Hoffman, V.L. Changes in stress, burnout, and resilience associated with an 8-week intervention with relational agent “Woebot”. Internet Interv. 2023, 33, 100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, P.V.S.; Sujitha, S.; Estherita, S.A.; Vasantha, S. Effect of Hr Analytics, Human Capital Management on Organisational Performance. J. Educ. Teach. Train. 2023, 14, 117–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taherdoost, H. What Is the Best Response Scale for Survey and Questionnaire Design; Review of Different Lengths of Rating Scale Attitude Scale Likert Scale. Int. J. Acad. Res. Manag. 2019, 8, hal-02557308. [Google Scholar]

- Khattak, S.G. IN/SECURITY Afghan Refugees and Politics in Pakistan. SDPI, 2003. Available online: www.sdpi.org (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Ghufran, N. Afghan Refugees in Pakistan Current Situation and Future Scenario. Policy Perspect. 2006, 3, 83–104. Available online: https://www.ips.org.pk/afghan-refugees-in-pakistan-current-situation-and-future-scenario/ (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- UNHCR. United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. 2019. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/un-system-sdg-implementation/united-nations-high-commissioner-refugees-unhcr-24540 (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Siddiqui, S. Bank Account Facility for Refugees to Aid Economy. Express Trib. 2019. Available online: https://tribune.com.pk/story/1920562/bank-account-facility-refugees-aid-economy (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Newman, A.; Macaulay, L.; Dunwoodie, K. Refugee Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review of Prior Research and Agenda for Future Research. Int. Migr. Rev. 2023, 01979183231182669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atasü-Topcuoğlu, R. Syrian refugee entrepreneurship in turkey: Integration and the use of immigrant capital in the informal economy. Soc. Incl. 2019, 7, 200–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Center for Global Development. With US Withdrawal, Rights of Afghan Refugees in Pakistan Hang in the Balance, Ideas to Action. 2019. Available online: https://www.cgdev.org/blog/us-withdrawal-rights-afghan-refugees-pakistan-hang-balance (accessed on 1 August 2022).

- Morgan, C.J. Use of proper statistical techniques for research studies with small samples. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 2017, 313, L873–L877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karch, J.D. Improving on Adjusted R-Squared; Leiden University: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ursachi, G.; Horodnic, I.A.; Zait, A. How reliable are measurement scales? External factors with indirect influence on reliability estimators. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2015, 20, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komori, O.; Eguchi, S.; Copas, J.B. Generalized t-statistic for two-group classification. Biometrics 2015, 71, 404–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frost, J. How to Interpret the F-test of Overall Significance in Regression Analysis—Statistics By Jim. 2022. Available online: https://statisticsbyjim.com/regression/interpret-f-test-overall-significance-regression/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Kim, J. How to Choose the Level of Significance: A Pedagogical Note. 2015. Available online: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/66373/ (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Denaro, C.; Giuffre, M. UN Sustainable Development Goals and the “Refugee Gap”: Leaving Refugees Behind? Refug. Surv. Q. 2022, 41, 79–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashim, A. Refugees in Pakistan Hit by Aid Cuts as Europe Crisis Drains Funds. Reuters. 2015. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-pakistan-refugees-europe-idUKKCN0S71S520151013 (accessed on 2 August 2022).

- Alafi, K.K. Syrians and Business in Irbid City: Jordanian Stability and Refugees: A Qualitative Study. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2014, 9, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).