Abstract

This research explores development conflicts within Kopaonik National Park (NP) arising from the prioritization of winter tourism, particularly skiing activities and the associated infrastructure. This emphasis has led to the marginalization of the unique natural heritage that warranted the park’s establishment in 1981, presenting an unusual case of exploiting and jeopardizing significant Balkan natural heritage. Tourist facilities situated in protection zones II and III interface with natural reserves in protection zone I, escalating conflicts and spatial impacts and raising concerns about the preservation of reserves and the park’s original purpose. Kopaonik Mountain, inherently suited for winter tourism, faces the challenge of accommodating a ski center within its exceptional natural heritage. Legal and planning activities support winter tourism without adequately defining its compatibility with the park’s natural heritage. Through an in-depth analysis of legal documents, plans, projects, and studies, this paper highlights conflicts, especially with natural heritage, expressing concerns for the park’s future. The Spatial Plan of the Special Purpose Area of National Park Kopaonik, as a highly important strategic document, leans toward winter activities, prompting a critical review. The paper concludes with suggestions to alleviate winter tourism’s negative impacts and proposes sustainable practices within the realm of protected natural heritage and other human activities.

1. Introduction

Tourism is seen as one of the most significant economic sectors in many countries [1], characterized by a constant increase in the number of tourist destinations and a large number of other parameters [2]. Its multiple influences on the area in which it develops have long been recognized [3,4,5,6,7], with an emphasis on the relation between tourism and nature conservation [3]. The intensity of mass tourist movements in the middle and at the end of the 20th century started to exceed the carrying capacity of the environment [8], with wildlife viewing and outdoor recreation (much of which is centered on protected areas) as some of the fastest-growing aspects [9]. As environmental issues associated with rapid tourism have become critical concerns in recent years [10,11], Gössling [12] points out that global tourist activities affect the environment in many ways, such as through the “change of land cover and land use”, the “use of energy and its impacts”, and the “exchange of biota and species extinction”. Sustainable tourism development has attracted significant attention in many scientific studies, particularly in tourism studies, and has been a very fast-growing area of tourism studies research since the late 1980s [13]. As a form of tourism that adheres to commonly accepted sustainability criteria, including economic, social, environmental, cultural, ethical, and political aspects [14,15], sustainable tourism emerged in part as a negative and a reactive concept in response to the many issues of tourism, such as environmental damage and serious impacts on society and traditional cultures [16].

In the broader discourse on sustainable tourism, a notable focus has been on the intricate “tourism–nature conservation” relationship within protected areas. This dialogue is enriched by numerous studies that (a) identify and examine conflicts between nature conservation and the development of other segments, primarily tourism [17,18,19,20,21]; (b) consider and propose various instruments (strategic impact assessments and social impact assessments on the environment, planning zoning, etc.) for overcoming and stabilizing conflicts, i.e., frameworks for the implementation and monitoring of sustainable tourism in protected areas [15,22,23,24]; and (c) assess and value the tourist potential of natural attractions in protected and sensitive areas with the aim of developing tourism and ecotourism as an environmentally sustainable and acceptable model [25,26]. These perspectives contribute valuable insights into the ongoing efforts to harmonize tourism development with the imperative of nature conservation, underscoring the critical need for a balanced approach that respects and preserves the ecological integrity of protected areas.

Mountain regions are especially threatened by different anthropogenic activities, amongst which massive winter tourism and outdoor activities have become increasingly popular worldwide, presenting a new kind of human pressure on sensitive mountain ecosystems [27,28]. Additionally, tourism influences not only natural, sensitive mountain ecosystems but also those connected with traditional human activity in mountain areas that could also be valuable, i.e., seminatural mountain meadows—so-called traditional landscapes [29,30]. In some cases, these mountain meadows have been converted into ski slopes and are under pressure from tourism. The spontaneous development of tourism in particular contributes to the disappearance of traditional landscape elements which are replaced by entirely new landscape elements related to tourist development [30].

Winter tourism presents a complex array of conflicts that necessitate nuanced spatial planning and policy strategies. Many studies highlight the challenges of overcrowding, resource management, and the balance between ecological sustainability and tourism development [31,32]. The integration of environmental measures, as seen in the implementation of the EU Eco-Audit in ski resorts, underscores the importance of ecological considerations. Additionally, the dynamics of winter tourism are further complicated by global challenges such as health concerns during the COVID-19 pandemic [33], and the impact of climate change poses significant challenges to the sustainability and viability of winter tourism [34]. Altered snow conditions, crucial for skiing demand, highlight the profound impact of climate change on winter tourism activities [35,36,37,38]. This transformation in natural environments calls for adaptive strategies that balance ecological sustainability with the operational aspects of tourism. Moreover, the evolving preferences of tourists toward artificial snowmaking, coupled with winter sports enthusiasts’ varied perceptions of climate change [39,40], introduce additional complexity to managing winter tourism [41,42].

Incorporating nature conservation and natural heritage into winter tourism planning is crucial. Studies highlight the importance of aesthetic value in conserving and sustainably developing natural heritage sites [43] and the varying impacts of tourism, including endangerment in some areas [44]. Local institutions are key in resource management and conservation education, despite facing challenges [45]. Evaluating ecosystem services helps balance conservation with tourism [46], and stewardship in protected areas shows the importance of shared conservation values [47].

Winter sports resorts represent a special type of tourist destination due to the complex and two-way nature of their relationship with the natural environment [48]. These resorts’ success depends on the specific features of the environment [49]; however, winter sports resorts are also often perceived as places where particular threats to nature occur [50]. This is due to the large-scale nature of investments that interfere with nature, the accumulation of a large number of tourists, and the fact that they are usually established in mountain areas characterized by the highest value and sensitivity of ecosystems [48,51]. In order to achieve sustainable tourism development at a destination, especially concerning winter tourism, some authors [52,53] emphasize the necessity of considering tourist infrastructure as a key prerequisite, taking into account the importance of minimizing pressure on natural systems.

The interaction between the natural environment and winter sports resorts has been the subject of multiple scientific studies conducted over many years [49,54,55,56,57,58]. Despite this, it is important to point out that common scientific knowledge on this subject is highly fragmented [48]. In many cases, highly specific issues are the subject of research [59,60,61,62,63], while works that more comprehensively show the relationship between nature and how winter sports resorts operate are missing [64,65].

The construction of new ski resorts and the improvement of existing ski resorts are very attractive activities in transition societies of the Balkan region [66]. In Serbia, mountains’ potential for all-season tourism development is well known [67], and winter tourism is developed in several mountain regions [68]. On the other hand, the environmental impacts of Serbian ski resorts are recognized as very strong, leading to the degradation of unique mountain landscapes and functionality losses [69]. It was observed that processes of urbanization, construction, or improvement cause not only the degradation of topsoil and native vegetation but also floods, noise, air and water pollution, etc. [69,70,71,72,73]. Ristić et al. [69] point out that legal nature-protection standards are weakly implemented in Serbian regional ski areas. Kopaonik NP is chosen as the study area for this research because it is acknowledged as a region with the highest state protection level (national park) but is also well known as the location of the oldest and largest ski resort in Serbia and the second-largest ski center in Southeast Europe after Bansko in Bulgaria [71,73]. In accordance with significant but fragmented previous research, the aim of this study is, in addition to the comprehensive analysis and presentation of conflicts between skiing areas and natural heritage, to suggest potential solutions related to each conflict in order to achieve sustainable tourism development within Kopaonik NP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area Selection Model

The first methodological step of this research was the selection of a “case study” that would be relevant for the defined theme, objectives, and character of the study. To avoid random and subjective selection, three key criteria were applied:

- The criterion of a “categorized tourist location”, which implies that the research area is categorized as a tourist site by the Ministry of Tourism and Youth of the Republic of Serbia;

- The criterion of a “protected natural area”, which implies that the research area has the status of a protected area according to the Law on Nature Protection and is registered in the Central Registry of Protected Natural Assets managed by the Institute for Nature Conservation of Serbia;

- The criterion “conflict”, which implies that there are certain conflicts in the research area between nature conservation and the development of winter tourism.

The area of Kopaonik NP meets all the aforementioned criteria. It has been categorized by the Ministry of Tourism and Youth of the Republic of Serbia as a first-category tourist site [74]. This means that it represents an organizational and functional unit with an established tourist offering, natural values, and other attractions significant for tourism, along with municipal, transport, and tourist infrastructures as well as facilities for accommodation and tourist stay. Kopaonik is the most recognizable mountain destination and the most popular ski resort in Serbia, and for several decades, it has played a leading role in the tourist development of Serbia’s mountain destinations [75,76]. It also has status as a protected area of the first category of exceptional (international and national) importance. In accordance with the Law on Nature Protection, Kopaonik has been registered in the Central Registry of Protected Natural Assets as a National Park since 1981 [77,78]. Its protection status was later verified by the Law on National Parks [79]. The area of the Kopaonik NP is important from the perspective of the preservation of biodiversity, particularly areas which are important for the preservation of plant species—important plant areas (IPAs)—and areas for the preservation of the diversity of birds (important bird areas (IBAs)) and daily butterflies (prime butterfly areas (PBAs)) [75].

Although tourism has been continuously developing and nature has been protected in Kopaonik since the early 1980s, tourism development was not integrally considered with nature conservation, which has led to certain conflicts in the area. The natural resources and landscapes of Kopaonik are very attractive and significant for the development of tourism [52]. However, this area is often publicly labeled as the most degraded protected natural asset in Serbia [80]. Analyzing the realization of planning provisions, Ristić et al. [80] concluded that in some parts of Kopaonik, nature has been disturbed and the provisions of planning documents have been violated in terms of the planned scope of construction, the planned distribution of tourist facilities, and planned communal equipment. The construction of a large volume of cottages in the Lisina area which later evolved into guesthouses and small hotels was recorded, as well as the excessive and inappropriate construction of hotels and apartments in the Suvo Rudište area—the center of the ski resort [80]. As the main weaknesses of Kopaonik NP and a danger to the preservation of natural values, the authors of [75] identified the excessive construction of tourist facilities not in accordance with plans, the inadequate treatment of natural values, and inconsistency in the construction of tourist and general infrastructure. Potić et al. also claim that conflicts between economic and ecological goals are growing in this area and that it is exposed to strong anthropogenic influence and pressure caused by the development of winter tourism [76].

2.2. Description of the Study Area

Kopaonik NP is located in the southern part of central Serbia, 279 km south of the capital, Belgrade, and 130 km west of Niš (Figure 1). This part of Serbia is a rural area which, like most of the territory of the Republic, is exposed to negative demographic trends [81,82]. The NP covers the central, highly mountainous part of Kopaonik with an area of 12,079 ha, known as the central mountain zone, the base of which is made up of Ravni Kopaonik, a vast, mountainous area with an average height of 1600 m to 1800 m above sea level [83]. From its edges, the dominant mountain ridges and rounded peaks are Kukavica (1726 masl) in the northwest, Vučak (1714 masl) in the north, Gobelja (1934 masl) in the northeast, Karaman (1917 masl) in the east, and Suvo Rudište (1976 masl) in the south. Pančić’s Peak rises conically from it at 2017 masl, topped by a monument to Josif Pančić [84]. The Kopaonik Mountain Range is over 80 km long. It is bordered by the river valleys of the rivers Ibar, Jošanica, Rasina, Gornja Toplica, and Gornji Lab, but according to its geotectonic and geomorphological structure and the direction in which it extends, its mountain branches continue through Željin, Goč, and Stolovi [85]. The most attractive part of Kopaonik Mountain is its central mountain zone because of its dominant position, the vastness of Ravni Kopaonik, and the high mountain peaks.

Figure 1.

Location of the Kopaonik NP [80].

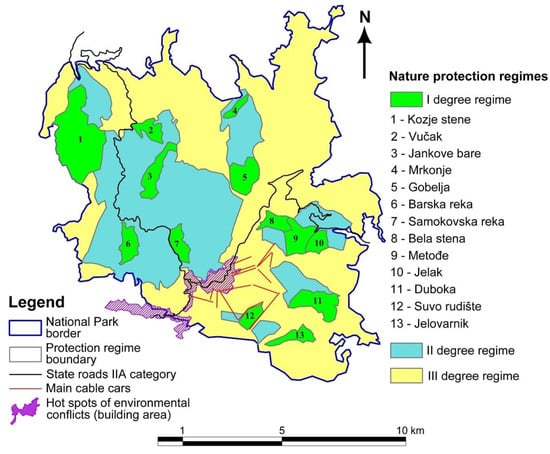

Due to the diverse and complex geological, orographic, climatic, and ecological conditions of this high mountain, Kopaonik has rich plant life from the most diverse ecosystems, with habitats of rare species and large areas of the highest quality coniferous forests [52,86]. On this basis, in the territory of the NP, 13 strict nature reserves have been selected, formed, and valorized which represent rare combinations of forest and grass communities with frequent relicts and endemics (Table 1). In addition, 28 natural monuments have been identified which are rare, naturally valuable, and attractive objects and phenomena of a geological, geomorphological, or hydrological nature in the forms of stone figures, geological profiles and sections, glacial traces, and springs and watercourses with waterfalls and cascades [87,88,89] (Figure 2).

Table 1.

Strict nature reserve areas under a first-degree protection regime.

Figure 2.

Nature reserves and natural monuments in the area of the Kopaonik NP. 1—Mrkonja; 2—Jelovarnik (waterfall); 3—Rendara; 4—Bele Stene; 5—Kozje Stene; 6—Vučak; 7—Metođe (“Geyser” Gvozdac); 8—Jankove Bare.

The area of the NP is dominated by the natural landscapes of Ravni Kopaonik. Some of Kopaonik’s particularly significant and attractive natural rarities are hydrographic objects, such as numerous thermal–mineral springs, the formation of which is caused by deep faults and the geological structure of the mountain [90], with an outlet temperature that ranges from 21 to 78.7 °C [90,91], as well as Jelovarnik Waterfall (Figure 2 (2)) in Jelovarski Potok (stream), which springs up from below mountain peaks in the eastern part of Kopaonik. The stream is about 3 km long with steep drops so that in its central section, Jelovarnik, is a complex, cascading type of waterfall with a height of about 60 m and an average fall of 60 degrees. The spring of the Duboka River is the biggest in Kopaonik, with a yield of up to 250 L/s; the river itself is fast-flowing with steep drops, and it loses its lower course among the chasms where there is a low flow of water so that for one part of the flow, the riverbed remains dry. Another natural rarity is a series of seven springs on the eastern slopes of Srebrnac, below Gvozdac (1425 m) (Figure 2 (7)), which form an unnamed stream with a 16 m high waterfall, as well as Semeteško Lake on the western perimeter of the national park. The lake is known for its beautiful surroundings and floating peat islands, which are a rare natural phenomenon [92].

2.3. Tourism Development and Conservation Challenges in Kopaonik NP

The attractiveness of Kopaonik, its central position, varied relief, hydrographic richness, especially in thermal waters [90], the construction of infrastructure and its high category accommodation, have resulted in Kopaonik Mountain and tourism on it being studied since the early 1960s. For such mountain massifs, it is known that there are several types of tourism that are interdependent and interrelated, namely, residential tourism (mountain, spa, and rural tourism) and short-stay tourism (day trips and excursions, events, transit, congresses, etc.) [93,94].

Tourism in Kopaonik, as the premier winter tourism center in the Republic of Serbia, flourished due to political and financial backing during the era of centralized planning, making it a unique case not entirely replicable under Serbia’s current transitional conditions [95]. Its significant national value is bolstered by state support and is closely intertwined with the natural and cultural heritage of the area, including the national park (NP) and medieval Serbian heritage, and complemented by well-developed superstructure and infrastructure [96]. This development is reflected in tourism data from 1980 to 2022 (Table 2), which shows remarkable growth: the number of tourists increased from 12,394 to 146,852, and nights spent in Kopaonik rose from 74,393 to 585,057. Additionally, bed capacity, which has been recorded since 2005, also saw a significant increase from 4799 to 8695 beds. This upward trend, despite occasional fluctuations (the disintegration of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, 1990–1995, and the conflict in the territory of Kosovo and Metohija in 1999), indicates a robust and adaptable tourism industry in Kopaonik, demonstrating its capacity to meet growing demands and potentially overcome global challenges such as climate change and pandemics.

Table 2.

Overview of tourism trends in the Kopaonik NP (1980–2022).

Investing all of this potential into the sustainable protection of the national park and the development of tourism is limited by the unresolved issues of integrating the institutional and organizational management of tourism with the protection and cultural use of the NP, as well as by the division of administrative responsibility between the ministries, NP Kopaonik PLC, the Public Enterprise for Forest Management “Srbijašume”, Public Enterprise Ski Resorts of Serbia, and the municipalities of Brus, Raška, and Leposavić. Other problems include underdeveloped infrastructure and utilities as well as low levels of the implementation and enforcement of adopted plans [94].

There has been no integral and multifunctional development of tourism on Kopaonik Mountain; instead, tourist facilities have been concentrated and constructed in the NP area of Ravni Kopaonik. The highest peaks rise up from Ravni Kopaonik, adorned with sports trails, viewpoints, and numerous cable cars. Therefore, in this rich landscape suitable for sports and recreation with high-mountain ambiance, fresh, warm summers, and long, snowy winters, it is possible to successfully develop recreational summer tourism and sports/recreational winter tourism. However, the steep and high-mountain terrains above the upper forest border are very sensitive to the beginnings of erosion processes under the influence of sports and other activities [66,99]. For this reason, these steep slopes, passes, and zones of water sources have been placed under protection. The strictest protection level, known as the I-degree, is applied to the most valuable and well-preserved sections of the NP in Serbia, encompassing 13 nature reserves and 27 nature monuments. Activities such as resource use and construction are strictly prohibited, with allowances only for scientific research, monitoring, and controlled visits for educational and cultural purposes. The II-degree protection regime allows for management interventions in areas with partially changed ecosystems, focusing on preserving and improving the protected zone. Limited and controlled use of natural resources is permitted, while anthropogenic activities like construction are prohibited. The III-degree protection regime applies to areas with altered ecosystems, emphasizing sustainable and controlled spatial development for improving economic and living conditions. This includes selective resource use, the preservation of environmental and cultural–historical values, and development aligned with sustainability principles, such as constructing tourist facilities and improving rural infrastructure. Beyond the NP, the designated protection belt aims to prevent and mitigate external influences that may harm the NP [88,100,101] (Table 3). In the spatial plan for the national park, this terrain is covered by protection level I which, together with specially protected natural assets, covers an area of 1470.9 ha or 12.38% of the national park. The second level of protection, with limited conditions of land-use and established purposes, applies to 3600.4 ha or 29.94% of the total territory of the national park, while the level III protection zone comprises the remaining 7007.9 ha, or 57.68% [88,100]. The disadvantage of this concept is that the established regimes of protection and purpose are little respected.

Table 3.

Overview of the areas covered by the NP and regimes for protection via various planning and legal acts.

A problem arises because some economic and all tourist activities are located in protection zone III, encroaching on space in zone II and endangering reserves in protection zone I. Consequently, it is not possible to maintain established nature protection regimes. Conflicts manifest within the national park between ski areas and natural heritage in the form of autochthonous flora and fauna, water, and reliefs of exceptional beauty and significance.

The above-mentioned natural heritage and phenomena of the NP are special features of its mountain tourism, which is dominated by winter tourism (alpine skiing), which is confirmed by the accommodation capacities on Ravni Kopaonik and in Brzeće, the only settlement in the park, as well as by the tourist and communal infrastructure. Bošković et al. [68], based on the indicator values regarding the number of beds (accommodation capacity), indicate that the situation in the NP is unsustainable and negatively affects the quality of the tourist experience. The winter tourist center bears the name Tourist Center (TC) “Kopaonik”, and the administration of the NP does not participate in winter tourism activities, more precisely in skiing.

According to the latest data for the year 2024, in Kopaonik, the Ministry of Tourism and Youth has categorized 12 hotels, with a total of 1087 accommodation units and 2371 individual beds [74], while the other accommodation units remain uncategorized.

Tourism in Kopaonik is more stable and better organized than tourism in other mountain regions of the Republic of Serbia and has the necessary conditions to maintain its acquired status and reputation as an international ski center and the main center for mountain tourism in Serbia [102]. The tourist offerings of TC Kopaonik encompass its strategic location and various tourist complexes, notably including Suvo Rudište, Srebrnac, Brzeće, and Jošanička Banja, which host the majority of accommodation units. The most important part of the offer in the region is the alpine skiing area on the route from Pančić’s Peak (Pančićev vrh) and Suvo Rudište to Gobelja and Srebrnac as well as the Nordic slopes of Ravni Kopaonik, which mostly follow the routes of forest and field paths and trails belonging to the NP. The summer offer in the area is less extensive and consists of marked and partially planned hiking and mountaineering trails [94].

Kopaonik has over 50 km of alpine ski runs, including five FIS runs for slalom and giant slalom and twenty-four easy, fifteen medium, and nine difficult runs. Of these, 23 ski slopes have artificial snow systems, while 10 ski routes have machines for making artificial snow [103]. The slopes are served by a system of 25 chairlifts and ski lifts (and two conveyor belts) with a total length of 23.25 km and a capacity of 33,092 skiers per hour [103], making it one of the largest ski centers in this part of Europe (Table 4). Of the 25 chairlifts and ski lifts, three are six-seater chairlifts, seven are four-seater chairlifts, two are two-seater chairlifts, thirteen are in the “ski-lift” category, and two are conveyor belts [103]. All runs are interconnected and are located less than 100 m from the central hotel complex (ski to door). The average track width is 40 m, and the slopes range from 5 to 40% [103]. In addition to the ski runs for alpine disciplines in the Ravni Kopaonik area, there are 12 km (routes of 3, 5, and 10 km) of groomed runs for Nordic skiing [104].

Table 4.

Characteristics of the Kopaonik ski center.

2.4. Methods

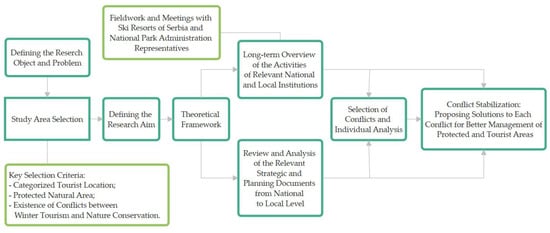

Based on the above, it can be concluded that this ski resort of Balkan significance, with all its facilities developed within Kopaonik NP, has functionally and spatially integrated facilities which have been separated and placed in fragments of the reserves. According to the object and aim of this research study, the methodological procedure (Figure 3) consisted of the following steps:

Figure 3.

Steps of the methodological procedure.

- The research commenced with the selection of a case study based on three criteria: official recognition as a tourist site by Serbia’s Ministry of Tourism and Youth, status as a protected natural area under Serbian law, and the presence of conflicts between nature conservation and winter tourism development.

- An introductory part which, in addition to the relevant theoretical framework, focused on a long-term and detailed analysis of the characteristics of the development and state of natural heritage, built tourist accommodations, and tourist activities. This part of the study was based on both primary (field research) and secondary data sources (the relevant literature and legal, strategic and planning documents (Law on NP Kopaonik (1981), Study of the Organization and Arrangement of the Kopaonik Area (1987), Spatial Plan of NP Kopaonik (1989), Law on National Parks of the Republic of Serbia (1993), Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia (1996), Spatial Plan of the Special Purpose Area of NP Kopaonik (2009), Master Plan of the Tourist Destination Kopaonik (2009), Spatial Plan of the Republic of Serbia 2010–2020 (2010), Spatial Plan of the Municipality of Raška (2010), Spatial Plan of the Municipality of Brus (2013), Law on National Parks of the Republic of Serbia (2015), Amendments and Supplements to the Spatial Plan of the Special Purpose Area of NP Kopaonik (2016), Report on the Strategic Environmental Assessment of Amendments and Supplements to the Spatial Plan of the Special Purpose Area of NP Kopaonik (2016), Amendments and Supplements to the Spatial Plan of the Special Purpose Area of NP Kopaonik (2023), and detailed urban plans for the settlements and tourist centers within the NP (Jaram, Rendara, Srebrnac, Suvo Rudište, Lisina-Čajetina, Sunčana dolina-Bačište, Brzeće, and Kopaonik)).

- An analysis of the causes of the current situation through a long-term overview of the activities of national and local institutions responsible for the management of the area of Kopaonik NP (National Park Administration, Institute for Nature Protection of the Republic of Serbia, Public Enterprise for Forest Management “Srbijašume”, Public Enterprise Ski Resorts of Serbia, and relevant ministries and local governments to which parts of the park administratively belong). A specific segment of this methodological step involved conducted fieldwork and holding a meeting with ski resorts of Serbia and NP administration representatives.

- Along with the previous step, relevant strategic and planning documentation from the national to the local level was reviewed, i.e., this study assessed how the relationship between the development of tourist activities and the preservation of the natural and anthropogenic heritage of the national park were treated in the plans.

- The selection of conflicts and their individual analyses. Within this step, it is important to note that the conflicts processed in this research were selected and observed in relation to the planning and development of the ski areas. This was carried out according to the fact that the specificity and uniqueness of the area, with built-in tourist facilities, would be difficult to observe through only one universal conflict in which tourist activities plunder, degrade, and destroy natural heritage and affect other dominant activities within this area.

- The presentation of proposed solutions to individual conflicts, with the aim of stabilizing the conflict situations as a basic prerequisite not only for the rehabilitation of the degraded natural heritage and other dominant activities within the national park but also to increase their quality and achieve sustainable development and coexistence with tourist activities.

Support in all phases of the research and cartographic attachment preparation was provided by contemporary GIS software capabilities (QGIS 3.28.0 software).

3. Results

3.1. Unraveling the Planned Degradation: The Systematic Plundering of Natural Heritage in Kopaonik NP

Plundering the natural heritage of the national park is not a spontaneous process but a planned, legally defined, and articulated procedure which has been carried out continuously for several decades. After a series of earthquakes on Kopaonik in the period 1977–1983, the preparation of a study and social action to eliminate the consequences of the earthquakes were initiated. A group of eminent experts with various specializations was mobilized to carry out the research. Expert opinions were given on 17 scientific and professional themes which dealt in detail with natural conditions and heritage, population, settlements and the economy, the contents of the social standard, creditworthiness and the concept of land use, technical infrastructure, possibilities for developing tourism, the preservation of natural and cultural heritage, etc. Based on expert opinions in the “Study on the organization and arrangement of the Kopaonik area” [106], conditions and factors for the development and protection of the Kopaonik area were given. Special attention was paid to the concept of the protection and use of natural and cultural heritage, as well as the concept of developing tourism and recreation. In the part of the study “Land-use regimes”, previously known limitations and existing and potential conflicts in the use of space were stated, namely, conflicts between settlements and agriculture, settlements and the protection of water, mining and agriculture, forestry and agriculture, forestry and natural heritage, and agriculture and natural heritage [106]. This was carried out for the wider area of Kopaonik in the period in which the Kopaonik NP area still did not have any significant tourist facilities.

While carrying out research and planning activities within the study, it was recognized that among the four valorized tourist regions, the Ravni Kopaonik locality of Suvo Rudište was ideal for mountain tourism as the future Tourist Center of Kopaonik, with around 5500 beds, thus having significance in the Balkans. A program entitled “Long-term Program for the Rehabilitation and Development of Kopaonik” was implemented through the Directorate for Rehabilitation and Reconstruction of the Kopaonik Area. The planning, design and construction of the winter tourism center was entrusted to Kopaonik GENEX. After preparation and planning, GENEX began with the construction of apartments in Suvo Rudište, the construction of cable cars, and the construction of ski slopes with the necessary technical infrastructure and roads [106].

A projection of tourist zones and centers which dominantly covered the territory of the NP and its natural heritage deviated from the expert solutions built into the study. In terms of development and organization, the vision of the development of tourist zones and centers in the Kopaonik NP was not adjusted in line with the use and preservation of valuable areas of forests and pastures, which were the primary reason for declaring Kopaonik (in 1981) a national park.

The results of research and planning activities were used for the construction of a tourist resort on Suvo Rudište, cable cars, and ski slopes which, over time, have covered the landscape of the national park. Since 1985, the territory of Kopaonik NP has been a space for the development of winter tourism, with the continuous construction of a network of cable cars (ski lifts), ski runs, accommodation facilities, and technical infrastructure (Figure 4). All this was designed and verified through current planning documents [87,88,107,108,109] as the basis for an even more intensive development of winter tourism and the construction of facilities and tourist infrastructure which directly generate and cause the previously mentioned conflicts between natural heritage and ski areas. It should be noted that the Republic of Serbia is a signatory to most international conventions, strategies, programs, directives, and agendas, which bind it in the field of sustainable development, biodiversity, and the conservation of flora and fauna. All of the above represent an example of how Kopaonik NP has been put in second place.

Figure 4.

Some of the observed conflicts in the Kopaonik NP. 1–3,13–15—degradation of vegetation and pedological cover and endangerment of natural assets and biodiversity; 4–11,13,15—intensive construction of accommodation facilities and technical and tourist infrastructure in the protection zone; 12—area of special purpose with military site on the Pančić peak.

Conflicts culminated in the early 1990s with a process of intensive unplanned construction, increasing accommodation capacity and the number of users. Intensive degradation of natural heritage was carried out in the period from 2006 to 2011 by extending the winter ski season and installing an artificial snow system, which accelerated the process of the illegal and unplanned construction of accommodation facilities. In certain parts of the NP, a large-scale unplanned construction of cottages has been recorded (around 10,000 accommodation units were built in the Lisine area, despite the plan allowing for only 1000), which later evolved into guesthouses and small hotels, as well as the excessive and inappropriate construction of hotels and apartments in the Suvo Rudište area (approximately 10,250 beds were built instead of the planned 8000) [80] (Table 5). Negative trends are still present today, so we can discuss intense conflicts and harmful impacts on the natural heritage of the national park whose significance, meaning, and functioning have reached absurdity.

Table 5.

Overview of the number of accommodation capacities (number of beds) from the planning documents.

In addition to the aforementioned study from 1987, the planning basis for further activities that endanger the natural heritage of the national park is found in the Spatial Plan for the Special Purpose Area of National Park Kopaonik [88,89] (hereinafter called the Plan). Those who developed this Plan, taking into account all of the positive and negative processes within the limits of the Plan, from 1981 to 2023 provided planning solutions and the possibility of implementing them within the current area on which the needs of the users, stakeholders, NP Administration, and relevant ministries of the Government of the Republic of Serbia are based [95]. Even if the protection zones of the NP are verified in the Plan, further elaboration shifts the focus to the development of tourism, where the existing and planned construction zones for ski lifts and ski resorts (ten ski zones), accommodation facilities (four primary ski centers), and social and technical infrastructure are verified. In addition to the existing 25 ski lifts, the construction of another 47 is planned, 66 km of which is in the national park, with an area of 92.5 ha. Within the boundaries of the park is 124.9 km of existing and planned ski runs, with an area of 624.5 ha [88].

The Plan for the protection of natural heritage with protection regimes I, II, and III defines natural monuments (dendrological) and the Ravnica Strict Nature Reserve as well as geo-heritage, habitats, and feeding grounds for the preservation of biodiversity as special purposes. This group includes four protected, two registered, and ninety-eight identified immovable cultural assets [88].

Apart from natural heritage, the Plan defines the following as special purposes:

- Zones and locations related to tourism: complexes that are part of the primary TC Kopaonik, secondary tourist centers and tourist villages, ski resort sectors, parking areas, the FIS polygon, the ski jump, and the Stefan Nemanja Memorial Complex;

- Zones and locations connected with ski resorts (existing and planned ski runs and ski lifts);

- Construction areas for commercial and residential complexes and a heliport with a hangar in the settlement of Čajetina;

- Planned facilities for the Ministry of Internal Affairs;

- Exploitation fields for mineral raw materials and exploration areas for geological research;

- Special purpose zones in which the following are defined: a zone where construction is forbidden with a complex for special purposes; a zone with limited purposes, a sanitary protection zone with a complete ban on construction, and a planned hunting ground with a reprocenter [88].

The Plan emphasizes that “the most important tourist complexes and related facilities of the tourist superstructure and infrastructure of Kopaonik will be realized in the area of the National Park”. The plan does not provide a planning basis for the protection of natural heritage, nor does it offer planning solutions that will mitigate or reduce the listed conflicts and pressures in the area. With the help of this document, which was adopted as a law [88], the construction of tourist complexes in 12 locations was able to place directly through the preparation of urban plans. The plan verifies the planned and unplanned activities that have taken place in the last 20 years and that have directly plundered the NP’s area. The spatial coverage of the Plan is wider than the area of the NP and totals 324.8 km2. Of this, 120.79 km2 (37%) is within the NP area, and 204.05 km2 (63%) is outside the NP area [88,89]. In this way, the “development ring” (space) around the NP is verified and observed, which will allow for the development of new winter tourism facilities that will surround the protected nature reserves and endanger them over time (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Nature protection regimes and conflicts within Kopaonik NP.

The Plan does not define the use of protected natural heritage; neither does the Plan show the biogeographical structures of the thirteen protection level I reserves with an area of 1470.9 ha or the eight protection level II sites with an area of 3600.4 ha. There are no verified and defined viewpoints or hiking trails provided for in the Plan that tourists can use to visit protected reserves and natural features. Everything is subordinated to the development of tourist activities and facilities, so the “Report on the Strategic Environment Impact Assessment of the Spatial Plan” states that there are no negative impacts on nature and natural heritage [110]. It should be emphasized that there are no precise data on which to base the degree of risk to natural ecosystems, bird and animal habitats, and plant species.

The Master Plan for the Tourist Destination of Kopaonik [111] did not recognize the NP as an area of exceptional landscape and biological value but rather as a suitable area for the development of alpine skiing because Kopaonik is already a regionally known tourist destination. Thus, it is necessary to optimize the key elements of the tourist offerings (ski system, accommodation, product offerings, and tourist infrastructure) and define strategic guidelines for the further development of this destination. Nature was left in the background, and the focus was on the analysis of relevant spatial planning regulations in the area of Kopaonik, making an inventory and conducting assessments of existing ski runs and ski lifts, the accommodation capacity, and tourist and technical infrastructure and carrying out an analysis of potential areas for developing the NP’s accommodation capacity and new tourist infrastructure [111].

The activities of the Kopaonik NP administration and the Institute for Nature Conservation in Serbia were also taken into account when investigating the causes and consequences of the increasing conflicts. In the management period since 1981, problems with the protection of natural heritage and buildings have been identified in the NP which are due to conflicts caused by ski areas. Numerous roundtables, lectures, and scientific meetings have been organized at which the results of scientific research have been presented. Significant activities are carried out by the Institute for Nature Protection of Serbia, which constantly monitors and approves planning and design documents. For example, during the development of the Brzeće–Mali Kamen gondola project [112], the Institute issued a negative assessment regarding its threat to natural heritage.

3.2. Analysis of the Observed Conflicts

Since the activities on the ski runs and the ski facilities have exerted considerable pressure on the area, which has led to a number of conflicts, it is necessary to break down the area of the NP into its natural and anthropogenic components in order to gain a detailed insight into the conflict situations (Table 6).

Table 6.

Conflicts between ski areas and the natural heritage in the NP.

Based on the analysis carried out, several researchers have addressed this issue. Ristić et al. investigated the problem of the rehabilitation of a ski slope on Stara Planina mountain destroyed by a torrent and landslide [66,70]. Demirović et al. [113] explored how tourism impacts ecosystems and property rights in mountain areas, suggesting that the development of conservation plans can positively affect the social–ecological system. Filipović and Lukić investigated the impact of power lines on forest ecosystems in national parks in Serbia [114], and Petrović et al. investigated the ecological features of vascular flora on ski trails in the Kopaonik NP, Serbia [115]. A study by Milijić et al. [116] addresses the intensified conflicts between ski areas and natural heritage in Kopaonik due to unresolved economic and social relationships, market mechanisms, and social and political contradictions. Ćurčić et al. [72] discussed the environmental challenges faced by winter tourism in natural, protected areas like Kopaonik, including land degradation, deforestation, and pollution. There was a study by Masin et al. [51] that evaluated the effectiveness of strategic planning for protected mountain areas in Serbia, including the Kopaonik mountains, by analyzing spatial and sector plans in tourism. The topic is current; however, it has not been the subject of broader scientific interest but rather of professional interest, which has been very modest in the preparation of strategic environmental assessments and environmental impact assessments for planned ski lifts and for similar tourist infrastructure facilities.

3.2.1. Conflict: Ski Area—Natural Assets

The NP on Kopaonik Mountain is a central and highly valuable area featuring diverse natural assets, such as high mountain landscapes, unique resources, and conditions suitable for various activities. Its geological richness includes ores and radioactive springs, along with renowned spas in the foothills [90,91]. Kopaonik’s elevated position provides stunning viewpoints, shaping a vertical climatic and vegetation gradient from sub-Mediterranean to alpine types.

The mountain hosts diverse flora, rich forest ecosystems, and rare species, especially in the sharp alpine climate of its highest section. With an annual rainfall of approximately 1000 mm and snow cover lasting 4–6 months, the orographic and climatic conditions favor winter sports tourism [117]. However, economic and other activities concentrated in the area, notably winter tourism, have posed challenges to the park’s protective function [75,118].

Road construction across Kopaonik has influenced its development and strategic importance, making it a complex NP with predominantly winter tourism. Ski facilities and slopes, though they boost tourism, have adversely impacted the park’s natural heritage, including strict nature reserves and rare natural assets [119]. The transformation brought by cable cars and winter tourism facilities has altered the natural landscape [75,116], leading to erosion in high mountain terrains [69].

Despite protection zones I and II covering a significant part of the park, economic and tourist activities in protection zone III intersect with zones I and II, challenging the established regimes for nature protection (Figure 5). Instances like unauthorized construction on Pančić’s Peak underscore the need for greater adherence to protection regulations to safeguard the park’s unique flora, fauna, water, and reliefs.

3.2.2. Conflict: Ski Area—Vegetation

Kopaonik’s diverse vegetation spans from oak forests at lower elevations to beech forests at 800–1100 masl, transitioning to beech-dominated landscapes from 1100–1500 masl which are often mixed with fir and spruce. Above 1500 masl, spruce forests prevail, especially on granite-based Ravni Kopaonik. Beyond 1800 masl, subalpine shrub vegetation emerges with tundra-like communities, featuring spruce, blueberry, and creeping juniper at the upper edge of the spruce forest. The highest peaks host high mountain meadows and alpine/subalpine pastures, along with rock formations and secondary herbaceous communities. Meadow communities within the beech forest belt are economically crucial among the 125 identified vegetation units [120].

Kopaonik’s vegetation diversity is scientifically noteworthy, with 118 associations and 39 subassociations cataloged, forming 62 alliances, 41 vegetation genera, and 24 classes. Notably, 60% of these syntaxons are found within the borders of Kopaonik NP, distinguishing the NP in terms of biodiversity within Serbia and the Balkans [52,86]. A qualitative analysis of the physiognomic types reveals that herbaceous communities constitute 74% of the vegetation units, while forest communities make up the remaining 26%. Moreover, 85% of the phytocenoses are of a primary character, reflecting the mountain’s potential, while 15% exhibit secondary or tertiary characteristics.

Ski tourism can have a detrimental impact on vegetation. According to Kňazovičová et al. [121], the construction of ski runs, their preparation, and snowpack compression can lead to the destruction of vegetation cover, decreasing biodiversity and interrupting successional stages. The delicate balance between economic development and environmental preservation is evident, particularly concerning the impact of ski infrastructure on forests. While developers aim to minimize deforestation, concerns linger regarding habitat destruction, erosion, and microclimate changes. Ski areas, utilized with mechanization for maintenance and artificial snow, pose challenges to pastures, causing degradation and species extinction.

In navigating the development of tourism infrastructure, Kopaonik faces the critical challenge of preserving its unique flora, fauna, and ecological balance while accommodating economic activities. As many environmental disturbances caused by the development of winter tourism on Kopaonik have already been registered, especially regarding destroyed vegetation and the fragmentation of forests [72], the need for sustainable practices and careful environmental management is paramount to ensure the longevity of this precious natural resource.

3.2.3. Conflict: Ski Areas—Pedological Cover

The distribution of soil types on Kopaonik corresponds to its vegetation zones. Below 800 masl, featuring thermophilic oak forests, there are serozem, organogenic, and organomineral humus silicate soils on serpentine. Between 800 and 1100 masl, with mesophilic oak and beech forests, brown and brown soils occur on serpentine, and acid brown soil is found on silicate rocks. From 1100 to 1500 masl (beech, beech and fir, and spruce and fir forests), the soil types include a humus variety of acid brown soil, brown soil on serpentine, and brown soil on limestone. At 1500–1800 masl, covering mixed forests, there are brown podzolic soils, acidic humus–silicate soils, and organomineral and brownish black soils on limestones. Above 1800 masl, in the upper forest border and alpine belt, brown podzolic soils and humus–silicate soils coexist [122].

Initial land degradation involves cutting down forests for ski slopes and cable cars (Figure 4 (1)), clearing uneven terrains, and rock removal. Skiing activities disrupt the compactness of the thin pedological layer, leading to erosion during snowmelt. Although there are several studies addressing soil erosion and loss in the Kopaonik region [123,124,125], they are not particularly focused on winter tourism as a significant factor. However, a recent study conducted by Potić et al. [76] identified the development of winter tourism on Kopaonik as one of the main causes of pedological cover degradation, particularly emphasizing the process of intensive soil erosion and the increase in areas with barren soil.

3.2.4. Conflict: Ski Area—Protection and Use of Water

Kopaonik’s diverse physical and biological conditions contribute to potent erosive forces in its watercourses, particularly in areas with specific geological compositions, steep slopes, and deforestation. The watercourse regime is influenced by snowmelt, resulting in increased flows in late winter and spring which are sustained through summer by rain and groundwater recharge, with the lowest flows in autumn and early winter. Notable rivers in the area include the Samokovska, Barska, Gobeljska, Brzećka, and Duboka. Semeteško Lake, situated in the park’s protection zone, holds scientific importance but lacks sufficient protection or developmental valorization [92,95,96].

The tourist center’s development necessitates substantial water for tourist needs, communal hygiene, and artificial snow production. To safeguard biodiversity, watercourses, and landscape features, efforts include forming smaller reservoirs with measures to mitigate negative impacts. While these reservoirs address water supply needs, strict consideration in planning is crucial if significant adverse effects on natural heritage and the environment are determined. Challenges arise with wastewater discharge, partly controlled and partly spontaneous, leading to environmental degradation. Regarding our study area, several studies confirm the negative impact of intensive winter tourism development on water quality, especially in terms of the physico-chemical composition of water and the condition of watercourses [72,126], as well as water consumption [127].

The ski center’s location near vital watercourses and lakes complicates matters as water flows into the Rasina and Toplica river basins, where dams (the Ćelije and Selova reservoirs) serve regional water supply systems. Robust protection measures are vital to preventing catchment area pollution, mandating wastewater treatment before entering these crucial water sources.

3.2.5. Conflict: Ski Area—Wildlife

The fauna of Kopaonik and the park area remains a less-explored biological segment, primarily studied within protected nature reserves with a level I protection regime. Recorded amphibians include the colorful salamander, yellow-bellied turtle, alpine newt, tree frog, grass frog, and Greek frog. Among reptiles, the live-bearing lizard/mountain lizard and Aesculapian snake are protected by the Decree on the Protection of Natural Rarities in Serbia, while the horned viper is covered by the ordinance on the control of the use and trade of wild plant and animal species. Additional species like the meadow lizard, wall lizard, and slow worm have also been documented [128,129]. The ornithofauna, influenced by the mountain’s enormity and distinct vegetation belts, boasts 166 bird species on Kopaonik. Changes in natural conditions over the past 50 years have led to the arrival and disappearance of various species. Nesting birds dominate, with 133 species, and the park’s boundaries seem accurately defined, hosting 120 nesting bird species. However, 99 bird species from Kopaonik are under protection, with 13 that have disappeared and 9 that are no longer visible. Research and protection efforts have focused on birds of prey through feeding programs since 1996 [88,110,126].

Previous research [106,115,126,128,130] indicates that Kopaonik’s mammalian fauna includes 39 species, with native species facing challenges. The American muskrat, appearing 40 years ago, is an exception. The elimination of bears, lynx, chamois, deer, and otters (in a protected zone) occurred in the last century, with the wild cat and wild boar now endangered. Two species from the area are on the European Red List, both classified as vulnerable. Ski areas development and vegetation conflicts threaten animal habitats, leading to the migration, reduction, and extinction of certain species. Human presence remains the primary cause of these phenomena, irrespective of habitat degradation levels.

3.2.6. Conflict: Ski Area—Livestock (Agriculture)

The NP, positioned in a mountainous and sub-mountainous agricultural area, underutilizes its agricultural potential, especially for livestock and mountain fruit cultivation. Despite market distances and protection regimes, nature protection measures present more advantages than constraints. Existing livestock units are around four times lower than the minimum necessary for profitability [88]. Efforts to establish farms on the prime meadows and pastures of Kopaonik have failed due to unprofitability, with local farms currently bearing the main burden of livestock, constrained by numerous restrictions [130].

Kopaonik, hosting significant resources for colored fruit production, is a primary habitat for blueberries and forest fruits. Local agricultural households organize the production and processing of these fruits, yielding well-known products [88,128].

While skiing and livestock maintenance occur at different times of the year, grazing animals on ski terrains hinder vegetation development, impacting meadow ecosystems’ vitality. The development of winter tourism indirectly diminishes livestock keeping as an economic branch, redirecting households toward tourist activities [94].

3.2.7. Conflict: Ski Area—Mineral Resources

Due to the depletion of ore reserves, the irrationality and lack of competitiveness of mining production, political problems on the border with Kosovo and Metohija, and restrictions imposed by the protection regime of the NP (especially for the extraction of wollastonite), mining on Kopaonik is not a significant economic activity in the NP [131]. Three mines (Gvozdac, Suvo Rudište, and Zaplanina) are located in the NP and its protected zone, while the Raičeva Gora mine is outside the NP’s borders [131]. The underground mines closed, followed by the surface mines, with the exception of the Belo Brdo lead and zinc mine, which operates at a reduced capacity. The planned rehabilitation of the closed mines in the area of the NP was not carried out.

As in the case of livestock farming, there is also a multifunctional negative impact in this case as there are surface and underground deposits of certain mineral resources at the locations of the ski resorts. The potential activation and access to exploit the deposits would raise a number of new issues ranging from economic viability to environmental justification and sustainability. Mining on the surface and in the shallow subsoil rules out the possibility of using the space for other purposes [131]. The exploitation of mineral resources in deeper layers conditionally enables the use of the space for skiing activities in the Kopaonik NP, in which a combination of activities related to winter and summer tourism and ore mining takes place [88,132].

3.2.8. Conflict: Ski Area—Special Purpose Areas

Within the national park, space serves mainly military purposes, with special facilities and zones for different purposes. The army was one of the first subjects in the development of Kopaonik. With its presence, initially only with official facilities and later with a military resort, it has simultaneously participated in and contributed to the development and construction of infrastructure and accommodation and, to some extent, limited the mass development of tourist activities due to training sessions for military units in the ski resort and military training area, as well as some other restrictions. Prior to the adoption of the Spatial Plan for the Special Purpose Area of the National Park, the army abandoned its earlier plan to use about 500 ha within the park for a training area intended for mountain training special units. In addition to the location of the military site, the army is a land user with an area of 20 ha near the military site. The functions and regime of the site on Pančić’s Peak (Figure 4 (12)) led to even greater restrictions on the ski resort and the movement of tourists by “taking” the mausoleum of Josip Pančić, which is a significant cultural and tourist motif within the military complex, and restricting the starting points of the existing and planned cable cars of Belo Brdo in the municipality of Leposavić. The uncertain fate of the military site on Pančić’s Peak in terms of purpose and jurisdiction, as well as in terms of territorial affiliation, makes the functioning of the NP and ski resorts uncertain.

The positive factor in this conflict is that the needs and interests of the army and the military troops present have significantly limited the possibility of expanding and forming new ski resorts and building cable cars in this part of the NP. The area and facilities are of strategic importance, so the development of winter sports areas is only possible with the consent of the user (the Armed Forces of the Republic of Serbia) of the area in question or one of the state institutions and according to the criteria set by them [133]. A precedent was set by the construction of an unplanned and illegal facility in a protection and security zone, where any construction is prohibited, on Pančić’s Peak.

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Due to the endangerment of basic natural phenomena in relation to the European criteria in the field of nature protection, Kopaonik NP is today gradually losing the characteristics necessary to classify it as a national park. Its natural values are not treated with their natural spatial integrity and are not compatible with the expansion and development of mountain tourism, especially alpine skiing. Therefore, if the conditions of the strict protection regulations are not met, the elements that make this area a national park will disappear [84,95].

The identified conflicts in Kopaonik NP and the results of this study could have significant national implications. This is particularly relevant considering that attitudes toward the development of mountain tourist destinations in Serbia have predominantly been based on experiences in developing Kopaonik which, compared to other mountain destinations, has the longest tradition and continuity in tourism development [116]. There are indications that the trend of developing mass winter tourism will relocate to other suitable mountain destinations in Serbia which are mostly protected natural areas. This is confirmed by existing master plans for the development of tourism in Golija, Stara Planina, Besna Kobila, Kučajske Planine, and Beljanica, which have been identified as future ski centers [134]. In these master plans for tourism development, concepts and solutions are based exclusively on a sectoral (economic) approach, without prior verification and without achieving spatial, ecological, social, and economic sustainability [135]. Therefore, the results of this study, the identified conflicts and challenges faced by the managers of the National Park and ski center, are significant for the future development of mountain tourism. They call for caution and learning from examples of poor practice, non-integrated tourism development, and the protection of space and the environment in Kopaonik. They suggest a need to abandon the current practice and model of tourism development in mountain destinations and to apply less intensive and more sustainable tourism development models to avoid the fate of Kopaonik NP. In Stara Planina, Divčibare, and Zlatibor, the degradation of nature has already occurred due to the construction of ski centers. In Stara Planina and Divčibare, work on building the ski center, and in Zlatibor on the renovation of the ski center, started in 2006 which, as in Kopaonik, caused erosion and deep gullies on the tracks [69]. Restoration and anti-erosion works in these ski centers have caused significant expenses [69]. In Serbia, Kopaonik and Zlatibor are in an advanced stage of tourist development [116], so here we are possibilities for damage remediation and conflict stabilization, while Stara Planina, Golija, and other mountains are in the initial phase of development; hence, the results of this study must be considered an example of poor practice in planning and sizing future ski resort capacities on other mountain destinations in Serbia.

On the other hand, Kopaonik is a ski resort which is popular not only in Serbia but also in this part of Europe [136]. Mountain tourism is one of the fastest-growing types of tourism in Southeastern Europe, and the experience of developing Kopaonik as a regional leader is linked to destinations in the surrounding area. Competitive mountain destinations in the region (Bulgaria, Romania, Montenegro, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Slovenia, Croatia, and North Macedonia) are developing their capacities to compete with Kopaonik [111]. Therefore, the results of this study have a broader regional (Balkan) significance and are relevant for competitive mountain destinations in the vicinity.

The survival of the national park largely depends on the further development of alpine skiing, i.e., on overcoming conflict with it. On the one hand, we have favorable terrains for alpine skiing in protection zone II and tourist complexes with intensive and unplanned development in protection zone III.

Based on the researched material and site visits, a group of dominant conflicts caused by the ski resorts in the national park was formed. We familiarized ourselves with the complexity and value of this area by analyzing all possible conflicts as well as the starting points for the following activities (Table 7). For each landscape and natural asset, it is necessary to carry out valorization in relation to the current situation. The next step is the concept of spatial organization, with a clear picture of the purpose of the area, conservation planning, organization, planning and land-use, with limits to its capacity.

Table 7.

Possible solutions for the “stabilization” of conflicts.

The proposed framework and solutions for the “stabilization” of the conflict in this work, although based on a specific and typical case study of the conflict between winter tourism and nature conservation in the national park, have a general character and are applicable in other areas with the same or similar conflicts.

A conceptual framework similar to this study was applied by Bukvić and Glamuzina [17] to identify conflicts and interest groups challenging a nature conservation policy in the Hutovo Blato Nature Park (Bosnia and Herzegovina). Conflicts were identified between the conservation of Mediterranean wetland ecosystems on one side and the hydroenergy sector, tourism sector, hunting associations, and local rural population on the other [17]. Another study of a similar nature, aimed at examining conflict and defining recommendations for conflict management in protected areas of Turkey, was conducted in Küre Mountain National Park [19]. Through an analysis and the determination of the level of conflict and its effect on the NP area among four interest groups (for the realization of tourism, the management of forest resources, wildlife management, management, and the administration of the NP), the root causes and possible consequences of the conflict were revealed [19]. The interest groups included local residents and village representatives, NP administration, NGOs, public institution bodies, tourism establishments and tourists, forest administrations, poachers, illegal hunters, and law enforcement agencies. Similar to the case of Kopaonik NP, in their study, Bukvić and Glamuzina [17] concluded that the conflicts are deeply rooted and that the readiness of protected-area managers to stabilize conflicts must be supported by national and local authorities as well as international organizations. This refers primarily to institutional and financial support, which is particularly important for Serbia and other countries in the region (Western Balkans). They significantly lag behind the countries of Central Europe [137], and even the countries of Eastern Europe [138], in terms of progress achieved in the transition process. They share a relatively high degree of inequality, unemployment, and poverty, and their economic development is based on the exploitation of natural resources [137,139]. Therefore, investments in ecology and achieving EU standards are not priorities and are often not available, leading to ecological problems in the form of the excessive exploitation of natural resources, excessive urbanization, and intensive and unbalanced tourism development that threatens biodiversity [137]. In addition, they face a lack of success in institutional transitions and building institutional capacities that would adequately, with proactive management approaches, respond to the challenges of economic transformation that have also affected protected areas, initiating a physical transformation of the space [138,139,140].

One of the main instruments for balancing different interests in protected areas is functional (re)zoning, which involves differentiating areas into zones with various regimes for protection and nature use [23]. This approach encourages appropriate land use and minimizes conflicts between incompatible uses [141]. It is also necessary to ensure the coordination and cooperation of the national park administration with other public institutions, organizations, and commercial enterprises to solve problems and minimize conflicts [19]. Therefore, there is a need for a coordination-based protection model [19]. Effective conflict management entails a participatory management model that includes all stakeholders and relies on policies for the protection and conservation of nature [17]. Measures to mitigate and proposals to resolve conflict as a product of such an organizational model would significantly contribute to the protection, use, and management of national parks [17]. The views of interest groups can be aligned with a more comprehensive and meaningful nature conservation policy while creating various development options for space users (sustainable tourism and agriculture) [17]. As an effective tool for adaptive management and supporting the development of sustainable tourism entrepreneurship in protected areas, Piñeiro-Chousa et al. [24] suggested a combined methodological approach of a cost-benefit analysis and a real options analysis which is flexible and easily applicable in other protected areas.

Area monitoring and inspection mechanisms should be strengthened to increase people’s sensitivity toward the conservation of biological diversity [19]. Social networks can be effective means of detecting and preventing irresponsible actions by users. Location-specific content posted by social network users can provide valuable information about visitor locations and activities in protected areas [142]. However, it can also deepen conflicts by showcasing irresponsible behavior and attracting visitors with low ecological awareness to protected areas [20]. Informing and educating visitors about the effects of their behavior on the environment also plays a key role [143]. More active dissemination of information, providing education on nature conservation, and transforming ecological education into ecological behavior are necessary activities for achieving sustainable tourism [17,144,145].

Solutions to the conflicts examined can be expected, provided that the legal and planning principles are redefined. There are two possible scenarios:

- The redefinition of the oversized ski facilities with the suspension of planning new tourist facilities in the national park.

- Repealing the law on the establishment of the national park from 1981 and complete subordination to winter tourism.

For the first, it is necessary to make a new planning document containing planning statements on the protection and preservation of the “remaining” natural assets in the NP. The presented alternative scenario for Kopaonik NP, at this moment, seems to be a path toward the complete weakening of the two fundamental segments (natural values and touristic significance) that make this area unique. The fact that the beginning of more intensive tourism development in Kopaonik is linked to the period of its designation as a national park suggests a causal relationship between natural values and tourism. Complete subordination to winter tourism and the abolition of protection measures and regimes would inevitably lead to the total degradation of natural resources and, consequently, to a decrease in Kopaonik’s touristic appeal. The high ratings of their attractiveness and importance indicate that natural resources and landscapes form the basis of tourism development in Kopaonik [52]. Further devastation of nature can have a disastrous impact on the competitiveness of Kopaonik as a mountain destination, i.e., on its regional and even international standing [75]. The touristic attractiveness and competitiveness of six winter mountain destinations in the Balkans were recently evaluated by tourists, with Kopaonik placing third, after Bansko (BG) and Borovets (BG) and before Jahorina (BIH), Zlatibor (SRB), and Stara Planina (SRB) [103]. The results showed that Kopaonik is both attractive to tourists and competitive, but it is necessary for the management of the NP and ski resort to focus on preserving natural values when planning and creating future tourist offerings. The value of natural attractions and the amount of snow cover were key elements in valorization, according to tourist assessments. This places focus not only on aligning the development of tourism and the protection of nature and the environment in protected mountain areas but also on the global phenomenon of climate change.

Today, climate change represents a significant risk and challenge for the survival of winter tourism [146]. At the beginning of the 21st century, a large number of studies focused on assessing the impact of climate change on winter mountain tourism. Research studies and projections of climate changes on various geographical scales clearly show that the length of the winter snow season will decrease [40]. Climate changes, manifested by increases in air and surface temperatures and reductions in the amount and duration of snow cover, negatively affect winter tourism, shortening the winter season and increasing the vulnerability and variability of natural snow conditions [35,36,147,148,149]. In the USA, it is expected that the length of the winter season will decline in all ski centers, in some areas by up to 80% by 2090 [42] and in some states by 4–14% during the time period 2010–2039 [35]. In Austrian ski resorts, a relationship has been proven between resort attendance and the amount of snow, i.e., the demand for skiing decreased by 14–48% in years with less snow cover [150]. Nowadays, already 57 of the main 666 ski resorts of the European Alps are no longer considered snow reliable [34]. Considering the results of global studies, it is assumed that the survival of winter tourism on medium–high mountains (up to 2000 m) such as Kopaonik (with Pančić’s Peak only 2017 masl) will be questioned in the future. Climate change can cause even greater pressure on the highest parts of the NP, where the snow cover lasts the longest, with the additional construction of ski slopes and artificial snowmaking systems. However, it is absurd to favor tourism in the NP and further expand ski resort capacities at a time when the survival (at least in current capacities) of the ski center is questioned due to climate change. The further degradation of nature in favor of expanding ski resort capacities, at this time, does not represent a rational move. Infrastructure built for a ski center without sufficient snow would not be purposeful, and the devastated natural areas would not be attractive or competitive for tourism. Several studies confirm that skiers adapt to climate change by changing destinations or substituting activities [41,151,152,153]. Therefore, in Kopaonik, there must be a focus on preserving natural tourism values and the potential transformation of existing winter ski tourism into other forms of tourism based on these values. Before making decisions about further plans for the development of snow-based mountain tourist destinations, planners must assess their sustainability and take appropriate measures, as the way tourism responds to climate change is critical for its sustainability [154,155]. In Kopaonik, they have already faced the consequences of climate change. A decrease in the number of tourists in March has been noticed as a result of rising temperatures and reduced snowfall [136]. Therefore, to reduce weather dependence, 23 out of 48 slopes are covered by an artificial snowmaking system [103].

The past twenty years have been characterized by a lack of effective control and protection measures, which has led to a significant increase in unplanned development in Kopaonik NP and revealed numerous weaknesses of the competent authorities and organizations that had to implement laws and control the implementation of valid planning documents [95]. It is realistic to expect that the spatial plan envisaged for the NP will be implemented over time, which means that the plundering and degradation of natural values will continue. The NP will continue to function and protect its natural values provided that the management of the state park (9862.6 ha–over 82%) is entrusted with the administration of the NP and that projects, monitoring, and financial resources are provided for the proposed solutions to the analyzed conflicts (Table 7). Based on the principles and values of landscape ecology, it is necessary to create a landscape plan for Kopaonik NP which would create a bio-landscape basis for the further development of tourism activities, nature conservation, and the rehabilitation of the analyzed conflicts. In this way, it is possible to mobilize and involve a wider circle of experts—biologists, ecologists, geologists, paleontologists, speleologists, geomorphologists, hydrologists, forest engineers, landscape architects, and other scientists—needed for the appropriate treatment and conservation of the natural heritage of the NP.

The area of Kopaonik NP is a unique natural complex facing severe environmental challenges that manifest in evident pollution and degradation, with escalating potential risks. The imperative to valorize and protect this area while facilitating sustainable tourism is paramount; failure to do so risks pushing the natural environment into a state of extreme degradation and imbalance. Given the prioritization of winter tourism development, the long-term viability and function of Kopaonik NP are fraught with uncertainty. This critical juncture calls for a decisive shift toward more sustainable and integrated approaches to tourism development and environmental conservation, ensuring the park’s preservation for future generations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.L. and B.P.; methodology, B.P., V.P. and D.R.; formal analysis, B.P., D.R. and V.P.; investigation, B.P., B.L., D.R., V.Š., M.R.J., D.S.Đ. and V.P.; writing—original draft preparation, B.L., B.P., V.P. and D.R.; visualization, D.R., V.P. and B.P.; writing—review and editing, D.R., V.P., B.P. and B.V.; supervision, V.Š., M.R.J., B.V. and D.S.Đ.; funding acquisition, V.Š. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of the Republic of Serbia (contract number 451-03-47/2023-01/200091).