Abstract

Reinforced concrete (RC) structures are vulnerable to damage under dynamic loads such as earthquakes, necessitating innovative solutions that enhance both performance and sustainability. This study investigates the integration of Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC) in RC frames to improve ductility, durability, and energy dissipation while considering cost-effectiveness. To achieve this, the partial replacement of concrete with ECC at key structural locations, such as beam–column joints, was explored through experimental testing and numerical simulations. Small-scale beams with varying ECC replacements were tested for failure modes, load–deflection responses, and crack propagation patterns. Additionally, nonlinear quasi-static cyclic and modal analyses were performed on full RC frames, ECC-reinforced frames, and hybrid frames with ECC at the joints. The results demonstrate that ECC reduces the need for shear reinforcement due to its crack-bridging ability, enhances ductility by up to 25% in cyclic loading scenarios, and lowers the formation of plastic hinges, thereby contributing to improved structural resilience. These findings suggest that ECC is a viable, sustainable solution for achieving resilient infrastructure in seismic regions, with an optimal balance between performance and cost.

1. Introduction

Recent seismic events, such as the 2023 Turkish earthquakes, have highlighted the severe structural vulnerabilities in existing buildings. These events caused extensive damage and loss of life, underscoring the need for advanced materials that can improve structural resilience and energy dissipation in RC frames [1]. This study addresses this demand by exploring ECC for enhanced ductility and sustainability in RC structures under seismic loads.

Structural engineers have been working to reduce earthquake-related damage to buildings and other structures. Their efforts have focused on understanding how earthquakes cause damage, quantifying the effects, and developing methods to mitigate the damage. Earthquakes create seismic waves that can cause compressive, tensile, and bending stresses in a structure, leading to the release of energy and damage to the structure. By understanding how these stresses occur and dissipating energy through hysteresis in structural members, engineers can help to reduce the amount of damage an earthquake can cause [2,3,4,5,6,7].

In addition to direct structural damage, earthquakes can have extensive environmental impacts, largely due to the high volume of construction and demolition waste (CDW) and the resource-intensive rebuilding efforts that follow. The 2023 earthquakes in East Anatolia [8] illustrate the severe environmental toll associated with large-scale structural collapse. According to [9], the loose enforcement of building codes, along with poor construction standards, exacerbated the destruction across Türkiye, resulting in widespread building failure and significant environmental degradation. The intersection of coseismic surface ruptures and secondary earthquake environmental effects (EEEs) like liquefaction and landslides further contributed to the high levels of structural damage and waste generation.

This extensive CDW includes materials such as concrete, steel, and other construction components that demand considerable resources for disposal or recycling. Bilgili and Çetinkaya [10] quantified the environmental burden of managing earthquake-generated CDW, finding that improper waste management, such as sending all debris to landfills, can result in substantial CO₂ emissions. However, alternative strategies like reusing concrete and recycling materials can reduce these emissions significantly, demonstrating the environmental benefit of sustainable material choices in construction.

In this context, Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC) present a valuable approach to mitigating these impacts. By enhancing ductility and crack resistance, ECC can extend the lifecycle of RC structures and reduce the need for frequent repairs or replacements following seismic events. Gonzalez et al. [11] propose that incorporating environmental impact metrics into seismic design—rather than adhering solely to life-safety objectives—can reduce the lifecycle environmental costs of buildings, especially when aiming for structures that are less prone to demolition and extensive repair after earthquakes. ECC’s durability and energy dissipation properties align with this sustainable design philosophy, as it minimizes structural damage, thereby reducing CDW and the associated environmental footprint. This research investigates ECC’s potential to support both seismic resilience and environmental sustainability, offering a dual benefit for earthquake-prone regions seeking sustainable infrastructure resilience.

Portland cement concrete (PCC) is a commonly used construction material with low tensile strength and toughness/strain capacity. However, by adding discrete high-strength fibers to the cementitious matrix, the ultimate tensile strength and tensile strain can be increased, and the energy dissipation capacity is enhanced. This behavioral change can also change the crack distribution, leading to the better control of crack width [12,13,14].

The addition of macrofibers makes fiber-reinforced concrete (FRC) [15,16,17,18]. There are two types of FRCs: thin-sheet products and bulk-structure products. Thin-sheet products require a high fiber volume fraction (3–10%) and unique processing methods, such as spray-up, layup, and extrusion. Bulk-structure products, such as ECC (engineered cementitious composites) [18,19,20,21,22], have a moderate fiber volume fraction (1–2%) and are typically mixed and cast using specialized techniques.

FRC has many advantages over traditional concrete [23,24], including increased strain-hardening capacity, improved toughness and ductility, and reduced weight. Despite these advantages, a fully detailed understanding of the structural behavior of FRCs is still needed to develop a design methodology for this composite [25].

ECC is a material that features an increasing tensile capacity under tension, which means that it can withstand significant stresses before breaking for extended periods. The development of multiple cracks in an ECC material results in strain-hardening behavior. Thus, allowing it to absorb and dissipate energy without significant damage is a good choice for engineering applications [26,27,28].

Kesner and Billington [29,30,31] conducted the monotonic compressive stress–strain testing of ECCs. Their results reveal that the inclusion of fibers drastically increased the ductility of a material; the curing process, the type of fibers and the existence of aggregates, and the shape of the specimens affected the tensile response characteristics of a material. Cyclic compressive testing indicated that fibers maintained the integrity of a material, and stable hysteresis loops were observed without any notable reduction from the backbone curve obtained from monotonic compressive testing. Similar findings on the cyclic response of ECCs by a study that investigated a relatively limited number of parameters [32] were also confirmed.

Said and Abdul Razak [33] investigated the effects of ECC on the behavior of RC exterior beam–column joints under reversed cyclic loading. They found that the ECC joint showed significant improvements in the ultimate shear and moment capacities, deformation behavior, and damage tolerance compared with the RC specimen at the ultimate and failure stages.

Yu et al. [34] found that ECC has a high tensile strain capacity and that different curing and drying processes, types of fibers, and loading protocols can produce ECCs with other properties. This research provides a detailed understanding of ECC properties and can be used to produce ECCs with desired properties.

The first analysis of crack bridging was conducted by Cox and Marshall [35], who found that the usage of fibers to bridge cracks endowed the material with a strain-hardening behavior. Li investigated short-fiber reinforced cementitious composites and developed a micromechanical model. Furthermore, Li and coresearchers [36] discovered a relationship between bridging stress and the width of a crack opening with a statistical approach and different volumes of fibers. The model was further expanded to account for the rupture of carbon and glass fibers by Maalej et al. [37]. Further analysis of the debonding interface was conducted to investigate the shear stress owing to fiber pullout, which characterizes slip-hardening behavior [38].

ECCs are primarily applied for the utilization of high ductility and crack-width control. For instance, Fischer and Li [39] concluded that ECC deformation is compatible with primary steel reinforcement after the first crack, leading to high damage tolerance and deformation.

In summary, the presence of fibers in the material increases its ductility, integrity, and resistance to load reversal. Additionally, compression softening does not cause significant strength degradation in tension.

Furthermore, studies have found that using an engineered cementitious composite (ECC) in beam–column joints can improve the ultimate shear and moment capacities, the deformation behavior, the damage tolerance, and the structure’s overall performance compared to regular concrete [19]. This information is essential for engineers designing materials subjected to cyclic loading, as it can help them choose materials that will be more resistant to failure.

The high cost of ECC microfibers has limited their widespread application in civil structures, with usage typically minimized to meet safety standards while balancing budget constraints. However, as sustainability and long-term performance become increasingly vital in infrastructure design, there is a growing need for innovative approaches that optimize the use of advanced materials like ECC. This study seeks to address this challenge by experimentally investigating the performance of reinforced concrete (RC) beams with partial and full ECC integration, considering both the presence and absence of steel stirrups. By evaluating structural behavior under different configurations, this research aims to propose more efficient and sustainable design strategies that leverage ECC’s superior properties while minimizing costs. The following section outlines the specific problem statement and research objectives driving this investigation.

2. Problem Statement and Research Objectives

The integration of microfibers in ECC significantly improves the mechanical performance of concrete, especially in terms of strain hardening and crack control. However, the high cost of microfibers and the specialized processes required for ECC applications make large-scale use economically challenging. This presents a critical trade-off between enhanced structural performance and cost-effectiveness, particularly in industrial and infrastructure projects where sustainability and long-term resilience are paramount.

While the strain-hardening behavior of ECC is one of its most desirable properties, the performance of the composite matrix can degrade into strain-softening when the fiber volume is not optimally controlled. Additionally, the design of ECC-based structures is often complex and reliant on empirical engineering expertise, highlighting the need for more systematic experimental and numerical investigations. Current design approaches may lead to undesirable failure mechanisms, such as unexpected shear failures under cyclic loading conditions, which compromise both safety and structural integrity.

Given these challenges, a sustainable and durable design framework for ECC structures must be developed. Such a framework should minimize costs while mitigating potential damage and ensuring performance under seismic and dynamic loads. To date, the cyclic and dynamic modal behavior of reinforced concrete (RC) frames with partial ECC replacement at critical locations—such as beam–column joints—remains largely unexplored in the literature. Addressing this gap is essential for advancing both the scientific understanding and practical applications of ECC in civil infrastructure.

While previous studies have addressed the static performance of RC and ECC beams, this research uniquely explores the impact of partial ECC replacement at critical locations with varying stirrup configurations. By evaluating these configurations, this study contributes to understanding ECC’s role in reducing shear reinforcement requirements, improving ductility, and achieving more sustainable RC frame designs, especially for seismic applications.

Moreover, integrating ECC into RC frames remains an emerging field, with limited studies addressing its combined effects on energy dissipation, ductility, and sustainability. This research aims to bridge this gap by providing a comprehensive analysis of ECC’s potential in enhancing RC frame performance.

This study sets the following research objectives to fill these knowledge gaps:

- −

- Construct and test small-scale RC beams, including two beams with partial ECC replacement and one fully reinforced ECC beam, to identify failure modes and crack propagation patterns in the presence and absence of steel stirrups.

- −

- Perform numerical simulations to study the structural behavior of RC frames when ECC is introduced at different strategic locations, such as beam–column joints.

- −

- Investigate energy dissipation through hysteresis and assess the residual deflection ratios of these framed structures under cyclic loading conditions.

Although cyclic load tests were not conducted experimentally, this study utilizes Zeus-NL simulations to examine cyclic behavior due to the software’s proven reliability in capturing ECC and RC material responses under seismic conditions. These simulations allow for an effective preliminary analysis of ECC’s potential in dynamic applications, setting a foundation for future experimental studies under cyclic loads.

3. Experimental Investigation

The experimental program consists of testing four beams under three-point loading: (1) an ordinary Portland cement RC beam with stirrups, (2) an RC beam with an ECC layer in the tension zone (RC–ECC) and without stirrups, (3) an RC–ECC beam with stirrups, and (4) a beam with ECC only and without stirrups. One reinforced concrete (RC) beam had different materials (ECC and RC) and different beam reinforcement patterns. This section first presents the materials, geometry, and test setup of the test specimens. The results obtained from the tests are discussed in detail; in particular, the failure modes and crack patterns are addressed.

3.1. Materials and Mix Design

3.1.1. Concrete Mix Design and Properties

A normal-weight ordinary PCC mixture was developed to obtain a 28-day nominal compressive strength of 45 MPa. The mixture binder was composed of type I cement with a water-cement ratio of 0.45. The aggregates used were 20 mm, 10 mm, and 5 mm, and dune sand was obtained from a local aggregate supplier. The sieve analysis, specific gravity, and absorption of the aggregates were determined in the lab according to ASTM C136 [40], and the testing results are shown in Table 1. A superplasticizer admixture, ADVA Flow 480, was used to reduce the water–cement ratio and give workability to the mix. Samples of 100 × 100 × 100 cubes were tested to have an average compressive strength of 49 MPa at 56 days with a standard deviation of 0.5. Statistical analysis of the test-to-nominal ratio of the compressive strength is log-normally distributed with a bias factor of 1.09 and a coefficient of variation of 10.2%. The concrete mix design used to cast the beams is presented in Table 2.

Table 1.

Percentage of aggregate passing by size.

Table 2.

Reinforced concrete mix design.

3.1.2. Steel Reinforcement

Here, 6 mm and 8 mm nominal diameter steel bars were used to reinforce the test specimens. The bars were made of hot-rolled unfinished tempered steel with grade 40 designation. A sample of these bars was tested according to ASTM A570 to obtain the actual mechanical properties. The average test results are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Properties of reinforcing steel bars.

3.1.3. ECC Mix Design and Properties

The ECC mix design used in this study used the same formula as that developed by Maalej and Li [41]. The ECC mixture binder was composed of Type I cement and silica fumes with a water–cement ratio of 0.27. A superplasticizer admixture, ADVA Flow 480, was used to give workability to the mix. The ECC mixture fibers used were a Honeywell Spectra® 900 fiber, a manufactured fiber with a high strength–weight ratio; the fiber volume used in the mix was 2% by volume of the total mixture volume. The manufacturer’s fiber specifications are listed in Table 4. The sample cubes were cast and tested; they gave an average compressive strength of 60 MPa at 56 days with a standard deviation of 2 MPa. Similarly, dog-bone test samples were cast to assess the tensile strength, and the average stress was 1.6 MPa. The ECC mix design is presented in Table 5.

Table 4.

Fiber dimensions and mechanical properties.

Table 5.

Engineered cementitious composite mix design.

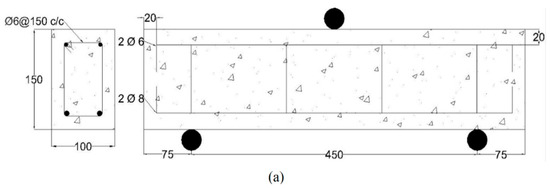

3.2. Geometry and Preparation of Test Specimens

Four beam specimens with rectangular cross-sections were tested in the university’s laboratory. The specimens were a regular RC beam with stirrups (designated RC-St and shown in Figure 1a), an RC beam with an ECC layer (designated RC-ECC and shown in Figure 1b) but without stirrups, an RC-ECC beam with stirrups (designated RC-ECC-St and shown Figure 1c), and a reinforced ECC beam without stirrups (designated ECC and shown Figure 1d). All beams have a clear span of 450 mm, a width of 100 mm, and an effective depth of 130 mm. The bottom flexural reinforcement of all the beams is two 8 mm bars, and the top reinforcement is two 6 mm bars. The stirrups are 6 mm bars with a spacing of 150 center-to-center. The ECC layer of the RC-ECC beams covered the bottom reinforcement to a depth of 40 mm from the bottom of the beam. Figure 1 shows detailed drawings of all test specimens with the support and loading conditions.

Figure 1.

Test specimens: (a) RC-St; (b) RC-ECC; (c) RC-ECC-St; (d) ECC (units: mm).

The configurations in Figure 1a–d were specifically selected to explore the role of ECC placement and stirrup reinforcement in enhancing the seismic performance of RC beams. By varying the presence and location of ECC and stirrups, this study aims to evaluate how these configurations impact failure modes, crack propagation, and energy dissipation under cyclic loads. These configurations allow for a comparative assessment of ECC’s effectiveness in crack control and structural ductility.

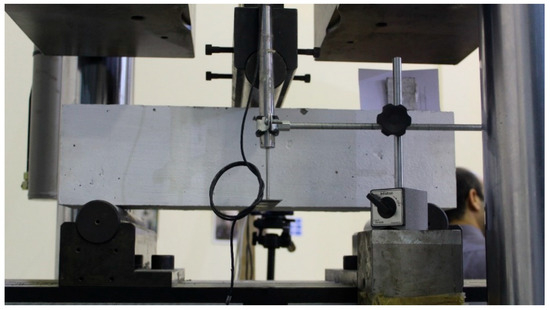

3.3. Test Setup and Instrumentation

The beam specimens were tested under a simply supported three-point flexure test by applying a point load using a DARTEC hydraulic actuator with a 1500 kN loading capacity. The beams had a clear span and shear span of 450 mm and 225 mm, respectively. The testing mode was displacement-controlled with a 0.01 mm/sec loading rate. A linear voltage displacement transducer (LVDT) was placed at the midpoint of the clear span of the specimen to measure the mid-span deflection. Figure 2 shows the test setup and the position of the LVDT. All test specimens were painted white to monitor the crack development and propagation during the tests. A crack-width ruler and crack-width microscope were used to measure cracks while the specimen was under loading.

Figure 2.

Test setup and instrumentation.

3.4. Results and Discussion

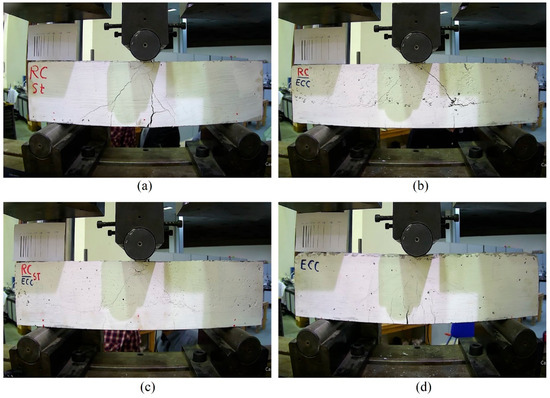

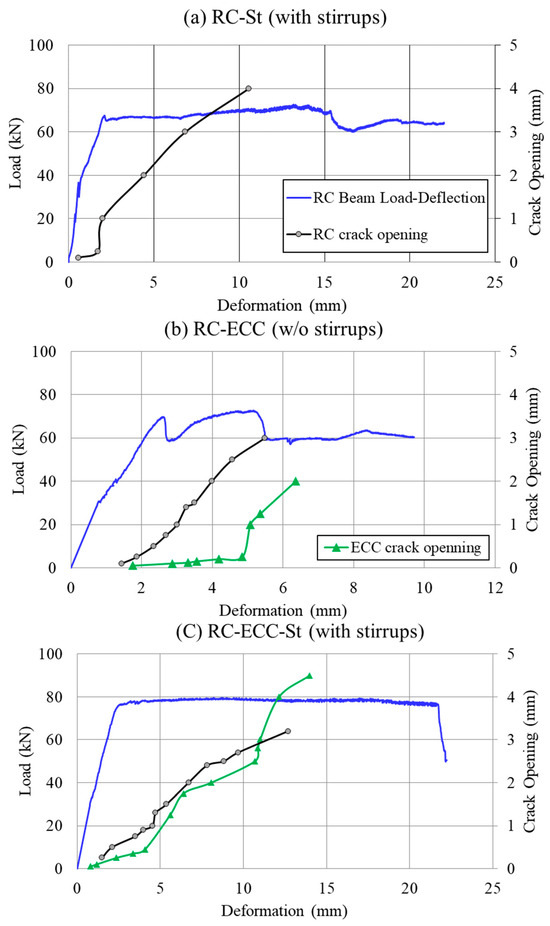

Figure 3 shows the failure state of the test specimens at the end of the loading protocol. During each test, the load and mid-span deflection were recorded automatically, crack development and propagation were observed in all specimens, and measurements of crack openings were taken at different deflection levels. The load–deflection curves and crack openings are plotted in Figure 4. Out of the four tested beams, only the RC-ECC (Figure 3b) beam without stirrups suffered a shear–tension failure, while the rest had a flexural failure. Note that this includes the ECC beam (Figure 3d) without stirrups; no shear failure was observed on the surface.

Figure 3.

Beam specimens after testing: (a) RC-St; (b) RC-ECC; (c) RC-ECC-St; (d) ECC.

Figure 4.

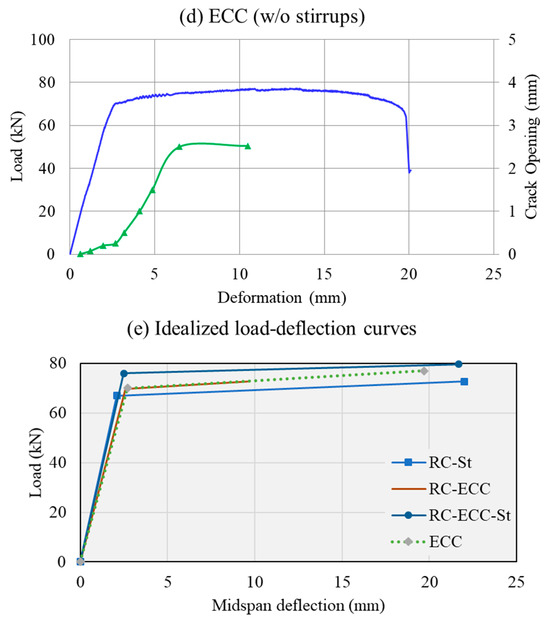

Load–deflection and crack openings: (a) RC; (b) RC-ECC; (c) RC-ECC-St; (d) ECC; (e) idealized load–deflection curves.

The RC-St beam with stirrups (Figure 3a) showed three significant cracks that continued to open throughout the test until failure. The initial crack, which formed at a load level of 36 kN, developed at mid-span in the tension side of the beam cross-section. Then, the second flexural crack started while the first one grew wider near 59 kN of loading. The third crack appeared at a load level of 67 kN. The beam failed directly after the main cracks widened, propagated, and converged at the load application point.

As shown in the load–deflection curves of Figure 4a–d, all beam specimens followed the typical linear elastic behavior with an approximately similar elastic stiffness of approximately 29 kN/mm until reaching the yielding point. The yielding displacement and yielding load were close and in the narrow ranges in all specimens. They were [2.1, 2.7] mm and [67, 70] kN, respectively (see Table 6)—the behavior after yielding shifted to the nonlinear plastic regime but with different displacement ductility. As reported in Table 6, the specimens with stirrups (i.e., RC-St and RC-ECC-St) were the most ductile beams, followed by ECC and RC-ECC. Specimen ECC was the most flexible among all tested beams.

Table 6.

Properties of the idealized load–deflection curves.

The RC beam with the layer of ECC but without stirrups (RC–ECC) showed a significant shear–tension crack that caused the failure of the beam (Figure 3b). Unlike the RC beam, this beam had microcracks that started to appear at a load of approximately 32 kN. These cracks were distributed in the tension side of the beam cross-section and localized in the ECC layer. At approximately 70 kN, two major diagonal cracks at a 45-degree angle appeared in the upper layer of the beam on the RC side, and then the load dropped noticeably (Figure 4b). One of the two cracks increased in size until it reached the ECC layer, following which the crack changed direction and became horizontal, splitting the beam at the interface between the RC and ECC layer. This kind of behavior is mainly due to the absence of stirrups in the upper layer of the beam. The ECC beam without stirrups did not fail due to shear or experience sudden failure, as evidenced by Figure 3d.

Moreover, comparing the load–deflection curves of beams RC-ECC-St and ECC (Figure 4c,d) shows that they behaved similarly, especially in terms of the overall behavior, displacement ductility, and cracking pattern. Both specimens did not fail due to shear even though the ECC beam had no stirrups. Therefore, it is safe to say that in this investigation, the use of ECC reduces or eliminates the need for shear stirrups due to the microfiber’s function in bridging any possible shear cracks.

As shown in Figure 3c, the RC-ECC-St beam with stirrups showed two major flexure cracks that caused the failure of the beam. While increasing the load, two major diagonal cracks appeared at the yield load (see Figure 4c and Table 6). Then, the concrete compression zone experienced concrete crushing. Since the load did not drop, the two cracks became very large such that the beam was almost split into three pieces, and the ECC fibers could be seen under high tension trying to bridge the cracks.

4. Modal Response and Nonlinear Performance of ECC and RC Framed Structures

In this section, the performances of a full RC frame, an RC frame with ECC at the beam–column joints, and a full ECC frame are investigated, and their performances are compared against each other. This investigation used two types of analyses: modal analysis and nonlinear quasi-static cyclic analysis. All analyses were run using Zeus-NL [42], which comprised a dedicated ECC material constitutive model for ECC [43,44].

4.1. Material Constitutive Models

Material properties, such as compressive strength and modulus of elasticity, were incorporated into the Zeus-NL analysis using values reported by Gencturk and Elnashai (2013), which provide a realistic representation of ECC and RC material behavior under load. For ECC, a Zeus-NL custom model was adopted that includes parameters such as tensile strength, modulus of elasticity, and ultimate compressive strain, closely reflecting the empirical data from Gencturk and Elnashai’s study. These properties are critical for accurately capturing ECC’s energy dissipation and ductility under cyclic loading. Similarly, the RC material properties were defined using standard concrete models within Zeus-NL, with adjustments for confined and unconfined concrete stress–strain behavior. By adopting these realistic material values, we ensured that the simulation effectively represents the structural response of both ECC and RC materials, allowing us to assess ECC’s performance in enhancing the seismic resilience of RC frames.

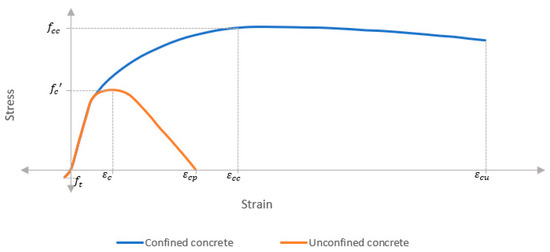

4.1.1. Concrete Constitutive Model

Confined and unconfined concrete models are essential for performing any analytical assessment of structures under cyclic or seismic loads. Therefore, the Martinez–Rueda nonlinear constant confinement model [45] for uniaxial loading was utilized in this study. This model is based on the model proposed by Mander et al. [46]; however, Martinez–Rueda used different equations to account for the damage level of a member corresponding to low, intermediate, and high strains because of the numerical instability of Mander’s model under large deformations. The model considers the effect of confinement in compression, where the confined concrete stress and ultimate confined concrete strain are calculated from the lateral reinforcement, the unconfined concrete compressive strength , and the unconfined concrete strain at peak stress . Equations (1) and (2) were used to calculate and ,

where is the confining pressure of concrete and is the correction factor developed by Mander et al. [46] to justify reducing confining pressure because of the spacing between lateral reinforcements. These two values can be found using the following equations:

where is the ratio of the ties, is the yield strength of the lateral reinforcement, is the distance between two adjacent longitudinal reinforcement bars, is the spacing of the lateral reinforcement, and are the dimensions of the confined concrete core, and is the ratio of the longitudinal reinforcement. The stress–strain envelope curve can be calculated based on Equation (6) from these parameters.

where is a dimensionless parameter, is the unconfined compressive concrete modulus of elasticity, and is the confined compressive concrete modulus of elasticity. and can be calculated as

As mentioned above, Martinez–Rueda modified the Mander et al. model by introducing three different equations based on the strain level (low, intermediate, and high strain) and the reversal point from the envelope.

The low-strain reversal point occurs when the unloading is in the elastic range, which corresponds to a strain with stress less than or equal to 35% of the maximum strength of the confined concrete. The plastic strain can be calculated as

where is the unloading strain and is the corresponding unloading stress.

The intermediate- and high-strain reversal points occur when the unloading is in the plastic range, corresponding to a strain with stress higher than 35% of the maximum strength of the confined concrete. The plastic strain can be calculated as:

The tensile behavior considered by this model is represented by a linear region starting from zero up to a tensile strength , and the stress–strain curve can be calculated as

The stress–strain envelope curve of this model shown in Figure 5 was implemented in Zeus-NL [42], and required four main model parameters for the full description of the concrete’s mechanical properties, including compressive strength and tensile strength, crushing strain, and confinement factor. Table 7 lists the values of the model parameters used in the present section. The confinement factor was calculated as

Figure 5.

Stress–strain relationship of confined and unconfined concrete (compression side only).

Table 7.

Modeling parameters of concrete.

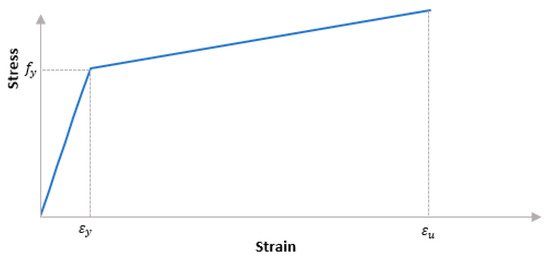

4.1.2. Steel Constitutive Model

The adopted reinforcing steel model is a bilinear elastoplastic model with strain hardening. This model was used for compression and tension and consisted of a linear elastic range and linear kinematic hardening range, as shown in Figure 6. Equations (14)–(16) are the defining model parameters. The first equation is for the elastic range and is valued for all stresses less than or equal to the yield stress . The second equation is for the plastic range at which the stresses are higher than .

where is the elastic stress, is Young’s modulus, is the elastic strain, is the plastic stress, is the tangent modulus, and is the strain-hardening parameter.

Figure 6.

Stress–strain relationship of steel reinforcement.

This model was incorporated into Zeus-NL, which requires Young’s modulus, yielding strength, and strain hardening. Table 8 reports the values of each of these parameters.

Table 8.

Parameters of steel reinforcement.

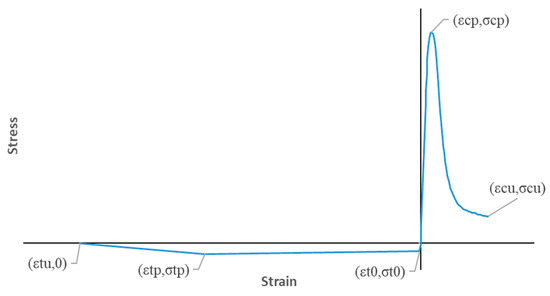

4.1.3. ECC Constitutive Model

The ECC constitutive model described below is based on several lab tests conducted by different researchers [43,44]. The compression behavior of ECCs has two distinctive parts, as shown in Figure 7—linear elastic stress–strain up to 2/3 of the strain corresponding to peak stress and a parabolic nonlinear stress–strain for all values higher than 2/3 of the strain corresponding to peak stress. These stress–strain relationships can be found using Equation (17).

where is defined by

where is the compression stress, is the compression peak stress, is the strain corresponding to the compression peak stress, is the ultimate compression stress, and is the ultimate strain.

Figure 7.

Stress–strain relationship of ECC in compression and tension.

The tension behavior of ECC investigated by Kesner and Billington [31] was characterized through three different linear regions, as shown in Figure 7—an elastic stress–strain up to cracking strain, a pseudostrain-hardening with stiffness reduction owing to the formation of multiple cracks until the ultimate tensile stress of the material is reached, and crack localization occurring as the tensile stress advances beyond the ultimate tensile stress and the material fails. These stress–strain relationships can be computed from

where is the tensile stress, is the cracking strain, is the stress corresponding to the cracking strain, is the ultimate peak tensile stress, is the strain corresponding to the ultimate peak tensile stress, and is the ultimate tensile strain.

These two models were combined, tested, verified, and implemented by Gencturk and Elnashai [44] in Zeus-NL. The combined model required nine parameters: Young’s modulus, first cracking strain, strain at peak stress in tension, strength in tension, tensile strain capacity, strain at peak stress in compression, strength in compression, ultimate strain in compression, and compression peak stress. All adopted parameter values are reported in Table 9.

Table 9.

Parameters of the ECC model.

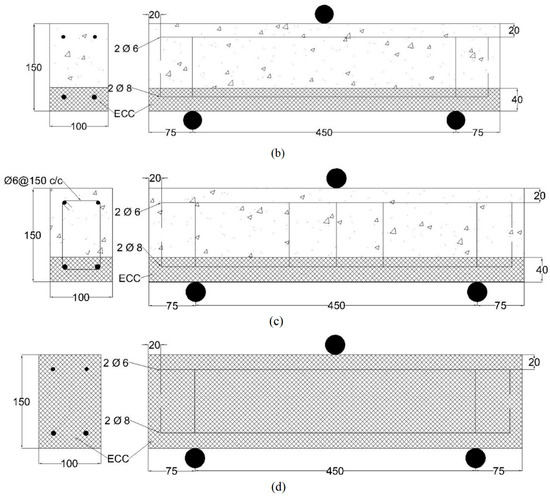

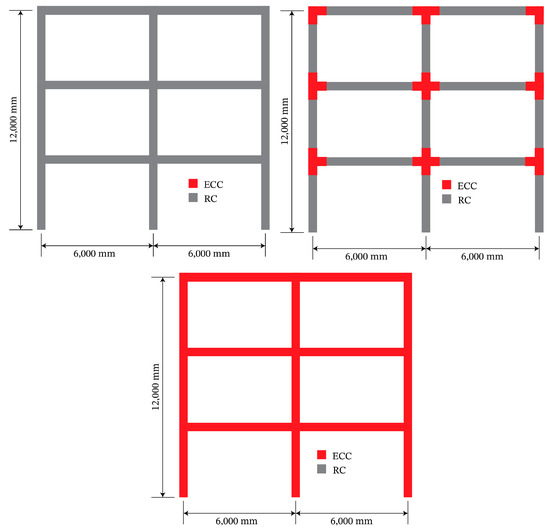

4.2. Description of Frame Structures

A reinforced-concrete three-story case study building with two 6 m bays in each direction and a height of 12 m above the foundation was designed according to ACI 318 [47,48]. The building was designed for a superimposed dead load of 1 kN/m and the structure’s own weight, a live load of 2 kN/m, and a seismic load according to IBC2000/ASCE 7 [49,50]. The superimposed dead and live loads were vertical loads applied on the beams, while the seismic load was a horizontally concentrated load applied at the structure’s joints.

Three sets of 2D frames with identical sections and reinforcement from the case study building were selected to assess the performance of ECC under cyclic loading (Figure 8). The first frame was made of RC alone (designated RC), the second included ECC at the beam–column joints (designated RC-ECC), and the third frame was made entirely of ECC (designated ECC). The frames were modeled in Zeus-NL [42]. The frames had rectangular column cross-sections with dimensions of 400 mm × 400 mm and rectangular beam cross-sections with dimensions of 400 mm × 450 mm. The columns were reinforced with 10#25 rebar, while the beams were reinforced with 12#16 rebar. All concrete sections were reinforced with the minimum required transverse steel.

Figure 8.

RC, EC-ECC, and ECC case study frames.

4.3. Modal Analysis

A complete modal analysis was carried out for all three frames. The results of the first three modes of vibration and corresponding natural periods of vibration are illustrated in Table 10. As shown in the table, all frames have the same mode shapes, but with different periods of vibration. The fundamental period of vibration (and subsequent periods) was the highest for the full ECC frame, followed by the RC–ECC, and the shortest fundamental period was that of the RC-alone frame. This indicates that the ECC frame was more flexible, and this particular frame will perform the best in the case of earthquake excitation, especially on firm and hard soils.

Table 10.

The first three natural periods of vibration and mode shapes.

4.4. Nonlinear Cyclic Quasi-Static Analysis

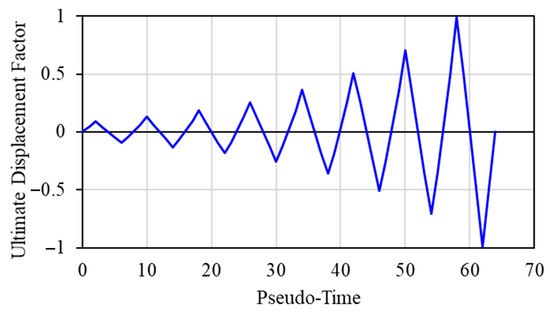

The same frames were analyzed using Zeus-NL when subjected to a cyclic load applied on the roof. The cyclic load protocol is based on FEMA 461 [51], which depends on the maximum displacement () obtained from pushover analysis. The loading protocol started from a displacement value of 0.048 and increased by 140% each cycle. For clarity purposes, only a subset of the loading protocol is shown in Figure 9.

Figure 9.

FEMA 461 loading protocol (partial signal).

4.4.1. Load–Deformation Response

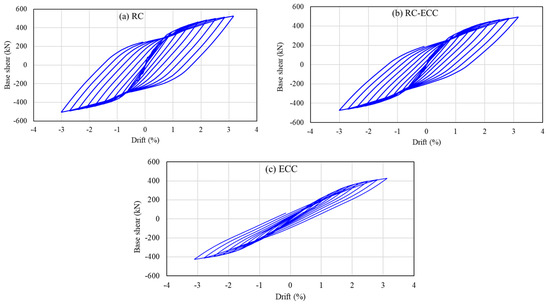

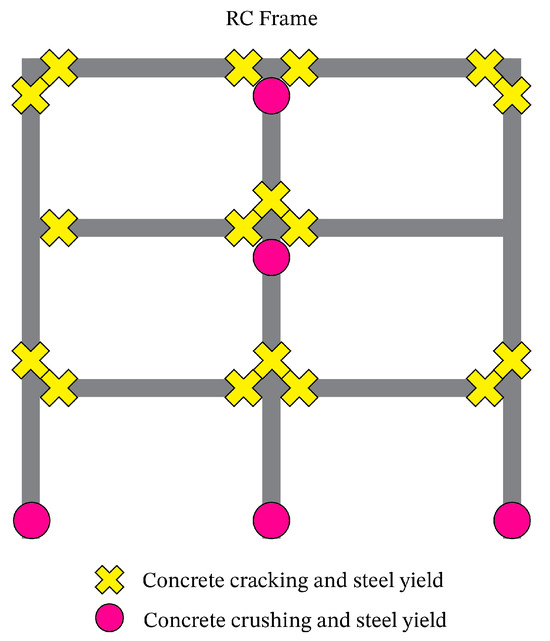

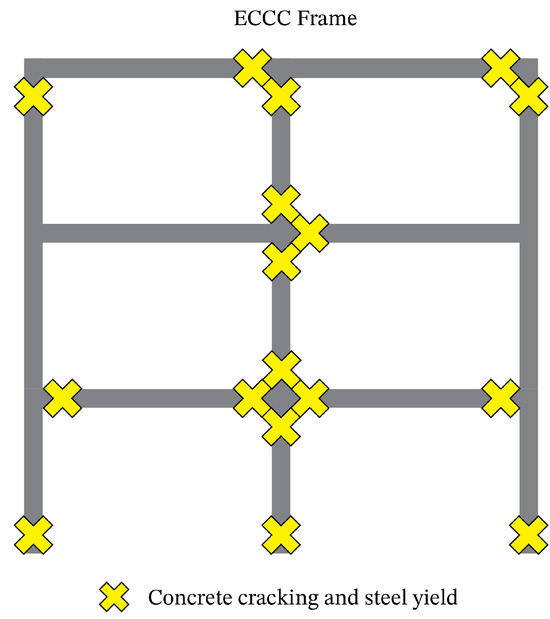

The load–deformation curves of the three frames exhibited hysteretic behavior, as shown in Figure 10. The hysteresis loops vary in width, implying different energy dissipation demands. The inelastic deformation of the RC frame appeared at approximately 1% drift (@300 kN) caused by the yielding of the reinforcing steel (Figure 10a). At 2% drift (@470 kN), the frame’s stiffness decreased significantly due to the formation of plastic hinges in the columns and beams, as shown in Figure 11. As the loading continued and reached 3% drift (@520 kN), more plastic hinges formed as more beams and columns reached their total plastic capacity. At the same time, the base shear increased, leading the frame to form a complete kinematic mechanism susceptible to collapse by sway. Figure 11 demonstrates the concrete crushing and steel yielding at the base of the columns of the ground floor and the upper parts of the middle columns of the first and second floors.

Figure 10.

Force–displacement curves of the three frames.

Figure 11.

Damage locations in the RC frame.

In Figure 11, areas of concrete cracking and steel yielding were identified based on strain thresholds established in the Zeus-NL analysis. Concrete cracking was detected when tensile strains exceeded the material’s cracking strain capacity, while steel yielding was indicated by strains surpassing the yield strain of reinforcement bars. These critical points are visually highlighted in yellow to illustrate the progression of damage and the stress concentration areas within the structural model.

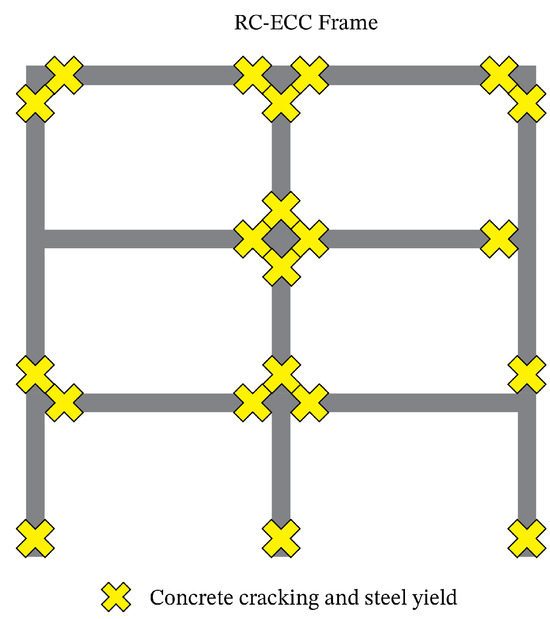

As shown in Figure 12, the RC-ECC frame exhibited a hysteresis behavior similar to that of the RC frame. Nevertheless, the damage was limited to the steel yielding due to the ECC contribution to the beam–column joints. However, the initial stiffness was slightly less than that of the RC frame (Figure 10b), but the effective stiffness was approximately the same at 167 kN/mm. The energy dissipation through hysteresis is less than that in the RC frame, which indicates the low level of damage sustained by the RC-ECC frame (Figure 10b).

Figure 12.

Damage locations in the RC–ECC frame.

Similar to the RC frame with ECC replacing the joints, the full ECC frame exhibited concrete cracking and steel yielding (Figure 13). However, as shown in Figure 10c, the narrow load–displacement hysteresis response loops indicate that the contribution of microfibers in the ECC mix has reduced the damage to the structural members. The full ECC frame had the lowest initial stiffness, and its effective stiffness and base shear were 20% less than those of the two previously discussed frames. The frame’s slight inelastic deformation started at approximately 1% drift (@220 kN), mainly due to the multitracking of concrete members and the partial yielding of the reinforcing steel.

Figure 13.

Damage locations in the full ECC frame.

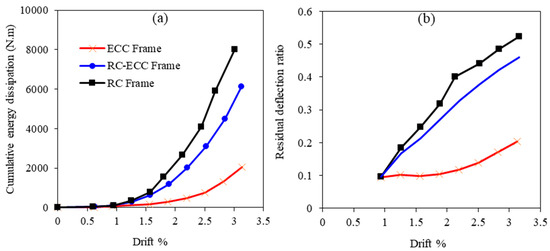

4.4.2. Hysteretic Energy Dissipation and Residual Deflection Ratio

To quantify energy dissipation in this study, we analyzed the hysteresis loops generated during cyclic loading tests, which provide a direct measure of a structure’s ductility and resilience to repeated seismic loads. The area enclosed by these hysteresis loops represents the energy dissipated through inelastic deformation, a critical factor in assessing structural performance under seismic conditions [52]. This approach aligns with methods used in similar studies, such as those by Pekgökgöz and Avcil [53] who examined the effects of steel fibers in enhancing the energy dissipation and ductility of RC beam–column joints under reversed cyclic loading.

Figure 14a presents the relationship between cumulative energy dissipation and drift. As previously discussed, the RC frame experienced severe damage because of the formation of plastic hinges at several locations. Therefore, the RC frame showed the highest energy dissipation among the frames. The energy dissipated in this frame was primarily the result of irreversible deformation and the concrete crushing of some members, as shown in Figure 14b. The RC-ECC frame (i.e., RC frame with ECC beam–column joints) showed a 23.5% lower energy dissipation than the RC frame and a 200% higher energy dissipation than the ECC frame (Figure 14a). This difference can be attributed to the redistribution of stresses from the ECC joints to the RC members, leading to fewer plastic hinges than the RC frame.

Figure 14.

Cumulative energy dissipation and residual deflection ratio.

The ECC frame dissipated the lowest energy through hysteresis (Figure 14a). The microfibers distributed the stress uniformly across the structural members, thus preventing the formation of plastic hinges and soft stories. The ECC frame had a 74.5% lower energy dissipation than that of the RC frame and 66.6% lower energy dissipation than that of the RC–ECC frame. Most of the energy dissipated by the ECC frame was in the form of viscous damping; therefore, the residual deflection ratio was practically constant (Figure 14b).

The takeaway from the analysis of the three frames is that the addition of ECC fiber reduces the base shear and number of plastic hinges significantly, which is evident from the RC-ECC frame result. The energy dissipated in the plastic deformation and residual deformation ratio of the ECC frame is the lowest of the three frames. The addition of ECC fiber reduces the plastic deformation and residual deformation ratio, which is evident from the RC-ECC frame’s result. The ECC frame exhibits the highest period of vibration and thus flexibility. The addition of ECC fibers increases the period of vibration and flexibility of a frame.

5. Conclusions

This study investigated the structural performance of reinforced concrete (RC) beams and frames with the partial and full replacement of concrete by Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC), using both experimental testing and numerical analysis. The findings demonstrate that ECC significantly enhances ductility, crack control, and energy dissipation in RC structures, establishing it as a promising material for improving the seismic resilience of civil infrastructure. Specifically, ECC’s crack-bridging capabilities and its ability to reduce reliance on traditional shear reinforcement make it an ideal material for key structural locations, such as beam–column joints, where enhanced performance is essential.

In the experimental phase, small-scale beam tests showed that ECC effectively mitigates shear failure and enhances flexural performance, even in configurations without stirrups. This suggests that ECC can reduce the amount of shear reinforcement needed, therefore offering an economical and sustainable solution for seismic applications. Numerical simulations further validated these results at the frame level, where ECC-reinforced joints led to a substantial reduction in base shear and a decrease in the formation of plastic hinges under cyclic loading. This improved energy dissipation capacity under seismic conditions highlights ECC’s effectiveness in enhancing overall structural resilience.

The results of this study demonstrate the ECC’s potential to achieve sustainable and resilient designs in earthquake-prone regions. By reducing the demand for additional shear reinforcement, ECC not only lowers construction costs but also contributes to the longevity and durability of RC structures. As the industry moves towards sustainable design solutions, ECC stands out as a material that combines high seismic performance with reduced environmental impact, supporting the development of safer and more sustainable infrastructure in regions vulnerable to seismic activity.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed to the study’s conception and design. Material preparation, data collection, and analysis were performed by M.L. and A.M. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M.L. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The University of Sharjah supported this work through the College of Graduate Studies via funds to the graduate student (author #2) and the Research Institute of Sciences and Engineering (RISE) via funds to the corresponding author (author #1).

Data Availability Statement

All data can be requested from the corresponding author, without the need to provide a reason.

Acknowledgments

The University of Sharjah supported this work through the College of Graduate Studies and the Research Institute of Sciences and Engineering, RISE. This support is duly acknowledged.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

References

- Avcil, F.; Işık, E.; İzol, R.; Büyüksaraç, A.; Arkan, E.; Arslan, M.H.; Aksoylu, C.; Eyisüren, O.; Harirchian, E. Effects of the February 6, 2023, Kahramanmaraş earthquake on structures in Kahramanmaraş city. Nat. Hazards 2024, 120, 2953–2991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achour, N.; Miyajima, M.; Kitaura, M.; Price, A. Earthquake-Induced Structural and Nonstructural Damage in Hospitals. Earthq. Spectra 2011, 27, 617–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucuoǧlu, H.; Erberik, A. Energy-based hysteresis and damage models for deteriorating systems. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2004, 33, 69–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mieler, M.W.; Mitrani-Reiser, J. Review of the State of the Art in Assessing Earthquake-Induced Loss of Functionality in Buildings. J. Struct. Eng. 2017, 144, 04017218. Available online: https://ascelibrary.org/doi/full/10.1061/%28ASCE%29ST.1943-541X.0001959 (accessed on 11 May 2022). [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.S.; Sexsmith, R.G. Seismic Damage Indices for Concrete Structures: A State-of-the-Art Review. Earthq. Spectra 1995, 11, 319–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASCE/SEI. Seismic Evaluation and Retrofit of Existing Buildings; American Society of Civil Engineers: Washington, DC, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Loh, C.; Mao, C.; Huang, J.; Pan, T. System identification and damage evaluation of degrading hysteresis of reinforced concrete frames. Earthq. Eng. Struct. Dyn. 2011, 40, 623–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yolsal-Çevikbilen, S.; Taymaz, T.; Irmak, T.S.; Erman, C.; Kahraman, M.; Özkan, B.; Eken, T.; Öcalan, T.; Doğan, A.H.; Altuntaş, C. Source geometry and rupture characteristics of the 20 February 2023 Mw 6.4 Hatay (Türkiye) earthquake at southwest edge of the East Anatolian Fault. Geochem. Geophys. Geosystems 2024, 25, e2023GC011353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mavroulis, S.; Argyropoulos, I.; Vassilakis, E.; Carydis, P.; Lekkas, E. Earthquake Environmental Effects and Building Properties Controlling Damage Caused by the 6 February 2023 Earthquakes in East Anatolia. Geosciences 2023, 13, 303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilgili, L.; Çetinkaya, A.Y. Environmental impact assessment of earthquake-generated construction and demolition waste management: A life cycle perspective in Turkey. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2024, 44, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.E.; Stephens, M.T.; Toma, C.; Dowdell, D. Incorporating potential environmental impacts in building seismic design decisions. Bull. Earthq. Eng. 2023, 21, 4385–4428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, E.; Ferrara, L. Self-healing capacity of fiber reinforced cementitious composites. State of the art and perspectives. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2017, 21, 2777–2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Ding, Y.; Liu, J.; Bai, Y. Energy dissipation characteristics of all-grade polyethylene fiber-reinforced engineered cementitious composites (PE-ECC). Cem. Concr. Compos. 2020, 106, 103459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrishambaf, A.; Pimentel, M.; Nunes, S. Influence of fibre orientation on the tensile behaviour of ultra-high performance fibre reinforced cementitious composites. Cem. Concr. Res. 2017, 97, 28–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zollo, R.F. Fiber-reinforced concrete: An overview after 30 years of development. Cem. Concr. Compos. 1997, 19, 107–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altoubat, S.; Yazdanbakhsh, A.; Rieder, K.-A. Shear Behavior of Macro-Synthetic Fiber-Reinforced Concrete Beams without Stirrups. ACI Mater. J. 2009, 106, 381–389. [Google Scholar]

- Altoubat, S.A.; Lange, D.A. A New Look at Tensile Creep of Fiber-Reinforced Concrete. ACI Spec. Publ. Fiber Reinf. Concr. 2003, 216, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblouba, M.; Al-Toubat, S.; Maalej, M. Engineered Cementitious Composites for Improved Crack-Width Control of FRC Beams—A Review. Spec. Publ. 2017, 319, 7.1–7.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qudah, S.; Maalej, M. Application of Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC) in interior beam–column connections for enhanced seismic resistance. Eng. Struct. 2014, 69, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Maalej, M.; Quek, S.T. Performance of Hybrid-Fiber ECC Blast/Shelter Panels Subjected to Drop Weight Impact. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2007, 19, 855–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblouba, M.; Altoubat, S.; Karzad, A.; Maalej, M.; Barakat, S.; Metawa, A. Impact response and endurance of unreinforced masonry walls strengthened with cement-based composites. Structures 2022, 36, 262–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altoubat, S.; Maalej, M.; Leblouba, M.; Karzad, A.S. Experimental study on the out-of-plane strengthening of unreinforced masonry walls using cement-based fiber composites. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 601, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasgul, U.; Yavas, A.; Birol, T.; Turker, K. Steel Fiber Use as Shear Reinforcement on I-Shaped UHP-FRC Beams. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorelli, L.G.; Meda, A.; Plizzari, G.A. Bending and Uniaxial Tensile Tests on Concrete Reinforced with Hybrid Steel Fibers. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2005, 17, 519–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stang, H.; Li, V.C. Classification of Fiber Reinforced Cementitious Materials for Structural Applications. In Proceedings of the 6th Rilem Symposium on Fibre-Rienfoced Concretes BEFIB 2004, Varenna, Italy, 20–22 September 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, E.-H.; Li, V.C. Strain-hardening fiber cement optimization and component tailoring by means of a micromechanical model. Constr. Build. Mater. 2010, 24, 130–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.; Saini, B.; Chalak, H. Performance and composition analysis of engineered cementitious composite (ECC)—A review. J. Build. Eng. 2019, 26, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.H.; Razak, H.A. The effect of synthetic polyethylene fiber on the strain hardening behavior of engineered cementitious composite (ECC). Mater. Des. 2015, 86, 447–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesner, K.; Billington, S.L. Investigation of Infill Panels Made from Engineered Cementitious Composites for Seismic Strengthening and Retrofit. J. Struct. Eng. 2005, 131, 1712–1720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesner, K.E.; Billington, S.L.; Douglas, K.S. Cyclic Response of Highly Ductile Fiber-Reinforced Cement-Based Composites. ACI Mater. J. 2003, 100, 381–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kesner, K.; Billington, S.L. Tension, Compression and Cyclic Testing of Engineered Cementitious Composite Materials. Art. No. MCEER-04-0002, March 2004. Available online: https://trid.trb.org/view/756217 (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Yuan, F.; Pan, J.; Dong, L.; Leung, C.K.Y. Mechanical Behaviors of Steel Reinforced ECC or ECC/Concrete Composite Beams under Reversed Cyclic Loading. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 2014, 26, 04014047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Said, S.H.; Razak, H.A. Structural behavior of RC engineered cementitious composite (ECC) exterior beam–column joints under reversed cyclic loading. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 107, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, K.; Li, L.; Yu, J.; Wang, Y.; Ye, J.; Xu, Q. Direct tensile properties of engineered cementitious composites: A review. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 165, 346–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, B.N.; Marshall, D.B. Crack Bridging in the Fatigue of Fibrous Composites. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 1991, 14, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, V.C.; Maalej, M.; Hashida, T. Experimental determination of the stress-crack opening relation in fibre cementitious composites with a crack-tip singularity. J. Mater. Sci. 1994, 29, 2719–2724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maalej, M.; Li, V.C.; Hashida, T. Effect of Fiber Rupture on Tensile Properties of Short Fiber Composites. J. Eng. Mech. 1995, 121, 903–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Zhang, Y.X.; Su, C.; Lo, S.R. Effect of Slip-Hardening Interface Behavior on Fiber Rupture and Crack Bridging in Fiber-Reinforced Cementitious Composites. J. Eng. Mech. 2015, 141, 04015035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, G.; Li, V.C. Effect of Matrix Ductility on Deformation Behavior of Steel-Reinforced ECC Flexural Members under Reversed Cyclic Loading Conditions. ACI Struct. J. 2002, 99, 781–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C136; Standard Test Method for Sieve Analysis of Fine and Coarse Aggregates. ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2015.

- Maalej, M.; Li, V.C. Introduction of Strain-Hardening Engineered Cementitious Composites in Design of Reinforced Concrete Flexural Members for Improved Durability. ACI Struct. J. 1995, 92, 167–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elnashai, A.; Papanikolaou, V.; Lee, D. Zeus-NL—A System for Inelastic Analysis of Structures-User Manual; Mid-America Earthquake (MAE) Center, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Urbana, IL, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Gencturk, B.E. Multi-Objective Optimal Seismic Design of Buildings Using Advanced Engineering Materials; University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: Urbana, IL, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Gencturk, B.; Elnashai, A.S. Numerical modeling and analysis of ECC structures. Mater. Struct. 2013, 46, 663–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Rueda, J.E.; Elnashai, A.S. Confined concrete model under cyclic load. Mater. Struct. 1997, 30, 139–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mander, J.B.; Priestley, M.J.N.; Park, R. Theoretical stress-strain model for confined concrete. J. Struct. Eng. 1988, 114, 1804–1826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Design Guide on the ACI 318 Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete—CRSI Resource Materials. Available online: https://resources.crsi.org/resources/design-guide-aci-318-19-building-code/ (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- ACI Committee 318. Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-08) and Commentary; American Concrete Institute: Farmington Hills, MI, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2000 International Building Code® (PDF Download). Available online: https://shop.iccsafe.org/2000-international-building-coder-pdf-download.html (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- ASCE 7 Standard. Available online: https://www.asce.org/publications-and-news/asce-7 (accessed on 11 May 2022).

- Publications:: FEMA, Interim Testing Protocols for Determining the Seismic Performance Characteristics of Structural and Nonstructural Components—Applied Technology Council Online Store. Available online: https://store.atcouncil.org/index.php?dispatch=products.view&product_id=209 (accessed on 12 May 2022).

- Dominguez-Santos, D. Optimization and analysis of hysteretic energy dissipators in reinforced concrete frame structures of five, 10 and 15 stories. Int. J. Prot. Struct. 2024, 20414196241286157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pekgökgöz, R.K.; Avcil, F. Effect of steel fibres on reinforced concrete beam-column joints under reversed cyclic loading. Građevinar 2021, 73, 1185–1194. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).