Abstract

This study examines the relationship between CO2 emissions, labor force participation, foreign direct investment (FDI), and trade openness on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Saudi Arabia, within the context of Vision 2030’s economic reforms. Vision 2030 aims to diversify the economy, reduce oil dependency, and promote sustainable growth, making it crucial to understand the factors influencing inflation and economic stability. Using annual data from 2001 to 2022 and the nonlinear Autoregressive Distributed Lag (NARDL) bounds testing approach, the study analyzes both short- and long-term effects. The findings reveal that higher CO2 emissions have a deflationary effect, reducing the CPI in both the short and long term, while FDI shows an inflationary impact with a delayed effect. Labor force expansion contributes to lowering the CPI, reflecting its deflationary pressure, especially over the long term. Trade openness is also examined for its dual effects on CPI, In the short run, both positive and negative trade openness reduce consumer prices, while in the long run, positive trade openness increases inflation, and negative trade openness lowers prices. This shows the differing inflationary impacts of trade openness over time. These findings contribute to the policy discourse on balancing economic growth, environmental sustainability, and inflation management, offering strategic insights for policymakers in alignment with Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 objectives.

1. Introduction

The economy of Saudi Arabia is in the process of rebranding as part of the Vision 2030 plan, which will reduce the country’s economic dependence on hydrocarbons. This shift has caused debates in terms of economic stability and inflationary rates with the Consumer Price Index as a key determinant of economic status and the cost of goods and services within the country [1]. Knowledge of the factors that lead to fluctuations in the CPI is useful for policymakers as they seek to formulate mechanisms to control inflation rates [2]. As part of Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030 plan, the variables of CO2 emissions, Foreign Direct Investment, labor force participation, and trade openness are critical to the country’s economic reforms [3]. Vision 2030 aims to diversify the economy, reduce dependence on oil, and promote sustainable development, making these factors central to achieving its economic goals [2,4]. Policies enhancing Foreign Direct Investment, labor participation, and trade openness, while addressing CO2 emissions, are designed to stimulate economic growth and stabilize inflation [5]. Among the factors that affect the CPI, CO2 emissions stand out as a critical factor because of their impacts on consumer prices and yet they need to be understood comprehensively as Saudi Arabia now adopts policies for sustainability development. Moreover, the labor force participation rate, which also affects the CPI so much, has received limited attention in prior Saudi studies. The Kingdom has also learnt about FDI and the impacts it has on economic growth, especially with the boost in expectations that more FDI will lead to positive changes to the economy [6]. Nevertheless, the influence of FDI on the Consumer Price Index and trends in inflation are still questionable. Trade openness, as a result of liberalization initiatives, is another important dimension of economic transition that requires research attention, especially its link to the CPI. This research seeks to explore the complex interaction between CO2 emissions, labor force, FDI, and trade openness with reference to the CPI in Saudi Arabia [7]. Hence, the primary research question explored in this study is the following: what is impact of CO2 emissions, labor force, FDI and trade openness on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Saudi Arabia under the Vision 2030 economic reforms?

This research uses a time series analysis model that is based on Keynesian economic theory to determine the impact of environmental and economic factors on the Consumer Price Index. Both the Keynesian model of macroeconomic thought and practice focus on total spending and its influences on output and inflation; employment levels and FDI influence the CPI. A strong labor force builds up the production capacity to help contain or lower down the CPI; conversely, a shrinking workforce leads to a rise in wages and production costs and thus increases the CPI [8]. Additionally, FDI is the mechanism through which capital is brought into the country; therefore, increasing the overall demand in the economy can have an effect on the general price level, specifically on consumer prices [9]. But on the other hand, FDI can also bring efficiency and technology, which can lead to the reduction of cost and inflation. Consumption expenditure together with investment expenditure is expected to influence the CPI through price changes due to imports and exports, with export demand likely to increase domestic prices. These economic theories are used in this paper to examine the links between CO2 emissions, labor force participations, FDI, trade openness, and the CPI in Saudi Arabia. By focusing on the dynamics of these variables, this study aims to provide valuable insights for policymakers in managing inflation and fostering sustainable economic development in the Kingdom.

Overview of CO2 Emissions and Consumer Price Index in Saudi Arabia

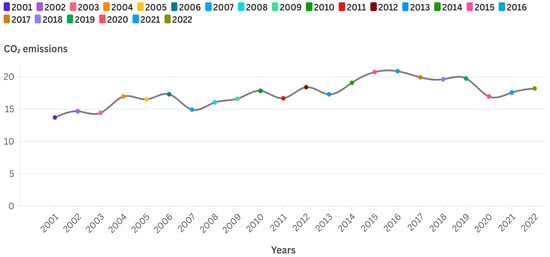

Figure 1 shows that Saudi Arabia’s per capita CO2 emissions exhibit a generally increasing trend, reflecting the country’s reliance on fossil fuels and industrial activities. In 2001, the emissions were approximately 2.62 metric tons per capita, gradually rising to about 3.03 metric tons in 2015. After a slight decline in subsequent years, emissions peaked again at around 2.91 metric tons in 2021 before slightly decreasing to approximately 2.90 metric tons in 2022. This pattern highlights the challenges Saudi Arabia faces in balancing economic growth with environmental sustainability, particularly as it continues to pursue its Vision 2030 objectives aimed at diversifying the economy and reducing carbon dependence.

Figure 1.

CO2 emissions (mt per capita) for Saudi Arabia.

Saudi Arabia’s energy consumption patterns heavily influence its CO2 emissions due to a strong reliance on fossil fuels, particularly oil and natural gas, which are significant contributors to carbon dioxide emissions [10]. Economic growth has driven increased energy demand across sectors like construction and transportation, further elevating emissions. Although there have been efforts to improve energy efficiency and invest in renewable energy, the transition remains gradual, overshadowed by the historical focus on fossil fuel production [11]. Government initiatives, such as Vision 2030, aim to diversify the energy mix and reduce oil dependence, but the effectiveness of these policies in decreasing emissions will depend on their implementation speed and scale [12]. Overall, shifting towards a more sustainable energy model is critical for mitigating CO2 emissions in the long term.

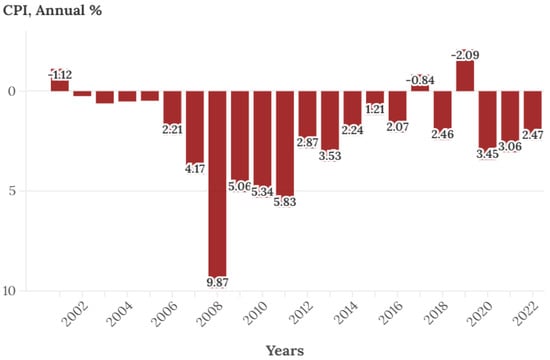

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) data are shown in Figure 2. Saudi Arabia reveals fluctuations in the annual percentage change over a series of years. The dataset indicates a notable decline in CPI values in earlier years, with percentages as low as −1.40% and −0.73%, suggesting periods of deflation or very low inflation. As the years progress, there is a gradual increase, with CPI values rising to 1.76% and 1.62% in subsequent years. This upward trend suggests a transition towards moderate inflation, which may be influenced by various economic factors such as changes in demand, supply chain dynamics, and government policies.

Figure 2.

Consumer Price Index (annual %) for Saudi Arabia.

2. Literature Review

2.1. CO2 Emission and Consumer Price Index

The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is one of the most important indexes used to reflect the average annual change in the price level for a range of products and services [13]. This index is commonly used for measuring inflation and deflation processes, which allows it to be valued as an essential instrument for the activity of policymakers, economists, and the financial markets in general [14].

Such trends as the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions are also becoming essential when concerned with the issue of economic growth efficiency in terms of environmental impact [15,16]. When the focus turns to climate change, it is essential to understand how inflation and the policy mechanism in carbon pricing work so as to comprehend its link to the rest of the economy [17]. In the past, it has been observed that as the economy grows, so do CO2 emissions, mainly due to the exploitation of fossil fuels during industrialization [18]. From this trend, it is possible to deduce that as the industrialization scale rises, the level of emissions also depends on the production capabilities of the countries [19]. However, the literature in previous years depicts a possibility of the above relationship diminishing, particularly in developed countries. For example, while in the European Union and United States the gross domestic product (GDP) remains steady or even grows, CO2 emissions either remain the same or decline [15]. Such changes can be explained by either increases in the energy intensity of the GDP or a transition to renewable energy sources, which can again affect the CPI by changing the cost structure of energy inputs in the economy [20]. Many emerging economies such as India and China have experienced rapid industrialization, therefore registering a direct relation in terms of GDP and emissions [21]. For instance, it was established that environmental gains from an increase in gross domestic product (GDP) were relatively low; a 1% rise in the GDP in India was linked to a 2 percent rise in total factor productivity (TFP) and, thus, the expenses of the economic enlargement in emerging markets [22]. This dynamic illustrates the trade-off that many developing countries face: economic development also leads to deterioration in the quality of the environment since growth is being sought blindly without worrying for the future effects it will cause on the general growth of the CPI and other aspects concerning consumers [7].

This relationship further becomes mixed up with the trade openness, energy consumption, and CO2 emissions variables. Analyzing the trend between energy consumption and economic growth, it has been determined that while this indicator increases with economic growth, the effects of the growth of energy consumption differ when renewable energy is in use [23]. Sound polices on renewable energy and efficiency consequently foster economic growth yet reduce the negative effects on the surrounding environment [24]. They may also feed back to the citizens’ standard of living by either stabilizing or lowering the Consumer Price Index within the long run, resulting in a more superior outlook to the CPI [1,24].

Also, other cleaner production methods like carbon taxes and the emissions trading system play an essential role in the management and control of CO2 emissions [25]. These policies can have an impact on inflation rates since they act to change the price parameters of carbon-intensive commodities and services [26]. The research in [27] demonstrates that volatility in carbon prices can result in short-term increases in inflation due to increased energy costs; however, the adoption of carbon prices stimulates research into renewable energy which, in turn, decreases the costs of electricity and, hence, the proportion of energy costs in the CPI budget [28]. This duality of impact means that the exact extent of inflationary pressures arising from carbon pricing, and, hence, the total effect of carbon pricing on total inflationary pressures, is unknown and therefore requires empirical analysis to ascertain its long-term effects on the economy and on climate change [16,29].

2.2. Labor Force and Consumer Price Index

The Consumer Price Index is a significant macroeconomic index in a country that tracks price changes for urban consumers for a set of goods and services over a period of time [30]. Thus, it can carry considerable consequences for the labor force and employment patterns. Among the demographic variables, age, sex, and education level are some of the significant factors that affect the labor force participation rate (LFPR) and CPI [31]. For instance, it is now common to see women engaging in paid work more than ever, which has been attributed to the change in society [32]. This alteration does not only impact the income level of households, but also the purchasing power of money to stimulate various goods and services, leading to the change in the CPI [33].

Other factors relate to the characteristics and trends in job-seeking activities within the labor force that influence the CPI. The usage of the internet and social networks as the main source of searching for jobs along with an increased role of young people in the employment market proves the need for the accessibility of technology [34]. Such a shift can affect the CPI given that it may change the demand of technical products and services and even employment patterns [30]. Indeed, as a larger number of people obtain employment via online intermediaries, the structure of employment and related goods and services that can be purchased may change, thus affecting the overall levels of inflation [35]. Employment relations, minimum wages, employment protection laws, and unemployment insurance also influence the CPI greatly [36]. They possess possibilities of shaping the mobility of the labor market and employing conditions, which are relevant to employees. Specifically, a proper structure of minimum wages can allow for higher wages for low-wage employees with a limited impact on employment [37]. On the other hand, protracted employment protection laws may discourage employment generation, especially for small businesses, thus affecting consumer prices through employment subordination [38].

The existing literature suggests that interventions in domestic value chains can have significant impacts on labor market conditions and the Consumer Price Index (CPI). Measures aimed at enhancing human capital development within these value chains are known to improve working conditions and increase wages, which, in turn, can boost employment status [33]. Such improvements in domestic value chains may also affect the CPI by altering the price levels of goods and services, as these value chains often yield results that differ from those of global value chains [24]. This perspective underscores the importance of understanding how domestic value chain interventions influence both employment and price levels, as supported by the existing body of research [39].

Therefore, the CPI is causally connected to demographic characteristics, job search behaviors, existing labor market structures (LM), and the instituted value chain development initiatives [23]. It is important to have these relationships expounded to policymakers and economists in formulating the right formula to control inflation and facilitate sustainable development [40]. When analyzing these elements in relation to each other, it becomes easier to design a more proper approach to the economic policy that deals not only with the stability of prices, but also with the health of the labor market [14].

2.3. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) and Consumer Price Index

Direct investment has become an essential area of study in countries’ economic systems after several decades, especially in the aspect of FDI in the growth of its economy and, hence, the rate of inflation as indicated by the Consumer Price Index (CPI) [36]. This literature review discusses the findings of recent works that have examined the impacts and determinants of FDI with a focus on the connection with the CPI.

In line with the above, an elementary observation from the literature mainly points towards a largely positive relationship entrenched by FDI growth on the economies of most developing countries inclusive of the least developed ones [21]. In direct employment, FDI brings technology, managerial and operational skills, and even boosts the host economy’s GDP [20]. These factors are important because GDP and the changes in it are usually associated with changes in the CPI, where an increase in GDP indicates increased demand of consumers in the market and, hence, higher prices [40]. FDI is significant for a country’s economic development because it supplements shortages in modern technology and skillful human capital and opens competition and general economic activity; therefore, it may lead to changes in inflation rates as can be seen in the CPI [41].

It has also been revealed that the mode of FDI affects growth and, consequently, the CPI differently depending on the type of FDI [42]. Greenfield investments, in particular investments in new production facilities, may raise capital stock, employment, and output and thus push up consumer prices as demand for products increases [43]. Brownfield investments, in which the buyer acquires the target firm’s assets, are generally linked to higher improvements in productivity in the early years [44]. Also, FDI can be classified into horizontal FDI (market seeking) and vertical FDI, which results in different impacts on the host economy and makes the relationship between FDI and the CPI even less discernable [9].

Studies using data at the firm level have contributed to the investigation on the case of technology transfer in multinational corporations (MNCs) [45]. For example, it has been established that host country changes in standards of patent protection are likely to affect technology transfer from the parent company to local affiliates, relative changes in royalties paid, and, possibly, cost structure [46]. This co-relation emphasizes the need for proper legal and intellectual property rights regimes in order to harness the benefits of FDI because it can influence the CPI through efficiency changes in production costs [12].

Knowing the sources that create FDI between countries, it is imperative to understand their impact on economic growth and the CPI. The two primary types of FDI—Greenfield investments and mergers and acquisitions (M&As)—are influenced by factors such as the financial development of the home country relative to the host country and the institutional quality of the host country’s financial system [41,43,47]. These dynamics make it possible to conclude that FDI decisions depend on the characteristics of both the home and host countries and may stipulate different effects for the CPI, depending on the type of investment and the conditions in the economy [5].

A cross-sectional analysis of quantitative research, which discussed FDI during 1950–2015, demonstrated that the focus was expanded to a more significant number of countries than predominantly case-study approaches [48]. For this reason, FDI was expanded to state that it occurs in complex environments that require different methods of analysis [49]. It is for these reasons that global academic discourse on FDI has obstinately challenged academic insight into the way it differentially links with the CPI, as FDI increasingly comes to define economic development while still having effects on inflation rates across different economies [50].

Therefore, the reviewed literature shows that FDI stands as a rather effective source to contribute to the economic development of both developed and developing countries; however, its impacts on the CPI may be rather positive or negative depending on multiple factors, including the type of investment, legal settings, and other indicators of an economic environment. That a country experiences FDI and a rising CPI shows that the two variables are related, implying that policies that have provisions for FDI can cause an expansion in the economy’s size alongside efforts to curb inflation [51].

2.4. Trade Openness and Consumer Price Index

Trade openness and the Consumer Price Index (CPI) have drawn a lot of interest in the field of international economics. There are a number of methods to measure trade openness, of which the most common is the extent to which a country is involved in trade irrespective of direction as estimated by the total trade shar, that is, total exports plus total imports divided by the total gross domestic product [24,37,52]. This relationship is important because openness in trade will have a direct impact on the prices within an economy which are represented by the researchers [40,53].

The theoretical framework which was used to analyze the relationship between trade openness and the CPI is anchored in classical and neo-classical trade theory [54]. These theories assume that trade liberalization enables nations to obtain a position to export goods that they produce more efficiently as compared to other nations [6,55]. From this specialization, manufacturer’s costs are generally contained; thus, prices offered to consumers are relatively low, which is a reality that would be manifested in a situation where the CPI is either stagnant or declining [56]. Moreover, technology and knowledge transfer enhance total fact productivity affecting domestic firms, and thus influence prices due to efficiency gains [19].

Findings made by empirical research on the relationship between indexes for trade openness and the CPI, on the other hand, have been inconclusive. Certain works show that trade liberalization has a positive effect on economic growth and assists in stabilizing, or decreasing, the CPI, and there are works that claim that the effects will depend on the level of development, the quality of institutions, or the nature of trade [47]. For instance, researchers [4] opine that trade can increase income levels, hence increasing demand; hence, prices may also be recorded to be higher, therefore affecting the CPI. On the other hand, the research in [57] showed that liberalization has a positive effect on economic growth, although this always has tendencies of increasing inflation due to increased demand.

Accurately defining and measuring trade openness is crucial for explaining its impact on the CPI. The traditional approach of using the trade-to-GDP ratio is often inadequate, as it fails to capture the full complexity of trade interactions [6]. Consequently, alternative indicators like the trade restrictiveness index or trade facilitation index have been proposed to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how trade policies influence economic conditions [27]. As a result, the selection of a particular measure can lead to varying empirical outcomes, affecting how the relationship between trade openness and the CPI is understood.

In order to fully capitalize on the benefits of trade openness, appropriate policies must be implemented. Investment in human capital, infrastructure, and institutional development can enhance the competitiveness of domestic firms, enabling them to enter export markets and influence price levels [58]. Additionally, sound monetary and fiscal policies that promote both micro- and macroeconomic stability, while facilitating trade flows, can help mitigate inflationary pressures linked to increased openness [56].

Overall, theoretical frameworks generally support the view that structural changes associated with trade openness led to lower prices and a stable CPI. However, empirical evidence remains mixed and context-dependent. The relationship between trade openness, economic growth, and the CPI is influenced by moderating factors such as the level of development and institutional quality. For policymakers, understanding these dynamics is crucial to ensure that the benefits of trade are realized while keeping inflation under control.

2.5. Theoretical Framework

The current paper seeks to assess the effects of CO2 emissions, labor force, FDI, and trade openness on the relative inflation rate expressed by the CPI.

The Keynesian economic theory mainly underlines the ability of the aggregate demand to influence various aspects of the economy like inflation and the CPI [1,25,59,60]. This theory supposes that variables such as labor force, FDI, trade openness can strongly influence the aggregate demand and, in a way, the CPI [59]. Increased employment might increase the manufacturing capacity, scaling down the manufacturing cost, which in turn affects the CPI [30]. On the other hand, a tight labor market increases the wages that are charged to firms, thus touching the cost of production, with the ultimate consequence being high prices for consumers [31]. FDI results in increased capital inflow which may improve economic circles and lift demand, though this may cause a consequential rise in the cost of goods and services available in the market [3]. But it is also a fact that FDI can introduce new technologies and better production processes which tends to decrease the CPI [14]. Trade openness is usually associated with competition that often results in efficiency gains that bring down the production costs, hence lowering the CPI [54]. However, opening up to global markets can also result in imported inflation in the view that trading partners’ inflation rates can also rise.

Based on these theories, this research develops a structural framework that aids in the examination of the impact that CO2 emissions have on the labor force, FDI, and trade openness in affecting the CPI. This method thus offers a strong theoretical framework for analyzing the interdependencies of these determinants and their effects on consumer prices.

Hypothesis 1 (H1).

CO2 emissions have a negative impact on the Consumer Price Index in Saudi Arabia.

Hypothesis 1 (H2).

Labor force has a positive impact on the Consumer Price Index in Saudi Arabia.

Hypothesis 1 (H3).

Foreign Direct Investment has a positive impact on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Saudi Arabia.

Hypothesis 1 (H4a).

Positive trade openness (TO+) has a positive impact on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Saudi Arabia.

Hypothesis 1 (H4b).

Negative trade openness (TO−) has a distinct impact on the Consumer Price Index (CPI) in Saudi Arabia, which could be either negative or positive depending on the specific context.

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Data

The present research endeavors to discern the impact of macroeconomic variables, including CO2 emissions (CO2), labor force (LF), Foreign Direct Investment (FDI), and trade openness (TO), on the Consumer Price Index (CPI). This study utilizes the annual data spanning from 2001 to 2022 for Saudia Arabia, sourced from the World Development Indicators (WDI) and the Global Carbon Budget (GCB). Table 1 presents a summary of the study variables, including their symbols, units of measurement, and data sources. To minimize the occurrence of data abnormalities and heteroscedasticity, all data were converted into natural logarithmic form.

Table 1.

Variables of the study and their descriptions.

3.2. Methodology

3.2.1. Unit Root

To accurately discern whether a time series variable is stationary, some scholars suggest distinguishing between stochastic trends and difference-stationary processes. This study employs the Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) test by [61] and the Phillips–Perron (PP) unit root tests to detect the presence of linear stochastic trends within the series.

3.2.2. NARDL Model

The long-term primary model of the study is given in the following equation:

CPIt = ∝0 + ∝1 CO2t + ∝2LFt + ∝3 FDIt + ∝4TOt + ɛt

The nonlinear autoregressive distributive lag (NARDL) can be used to derive both long-term and short-term dynamics and asymmetries of variables used in a model [62,63,64]. The NARDL bounds test can still provide robust estimates in the presence of a small sample size [62,65]. The approach is simple and flexible since variables are not required to be stationary at the same level [66]. It can also be applied regardless of the order of integration, with the exception that the series is not integrated at I(2) [62]. The study focused on the asymmetric impact of trade openness on the Consumer Price Index. Equation (1) provides long-term coefficients in a linear framework. However, the objective of this study is to investigate nonlinear effect of trade openness on the Consumer Price Index. Therefore, the nonlinear form of the model is specified as

CPIt = π0 + π1 CO2t + π2 LFt + π3FDIt + π4 (TO+t) + π5 (TO−t)

In Equation (2) above, π0, π1, π2, π3 π4, and π5 are the long-term parameters of the model. The asymmetric effects of trade openness on the Consumer Price Index are incorporated by both positive and negative changes denoted by TO+ and TO−, respectively. To derive the short-term and long-term effects of the variables, Equation (1) can be re-written as follows:

The terms with ∑ symbols represent the short-term error correction dynamics, while the terms with β indicate the long-term relationships among the variables [67]. The maximum lag lengths ρ, ρ1, ρ2, and ρ3 are determined using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), with t − i indicating the optimal lag selection according to this criterion. The research in [68] provided critical values concerning the F-statistic in the framework of bounds testing technique and constructed both upper and lower bound standards for different circumstances. Their account indicates that if the F-statistic computed is lower than the lower bound, then the variables of interest are not cointegrated. Thus, it can be concluded that the relationship is long-term if the F-statistic is greater than the upper bound. If the F-statistic is located in the range of these bounds, the result of the test is said to be non-significant.

Equation (4) below shows the nonlinear cointegrating regression of [65] given as

where Ωt are the long-term parameters of the k × 1 vector of regressors decomposed as

where are the independent variables, which are decomposed into a partial sum of negative and positive changes. The asymmetric impact of trade openness on the Consumer Price Index is accounted for by incorporating the positive changes and negative changes , where and are partial sums of the positive and negative changes in TOt, respectively.

Since our concern is mainly on the asymmetric impact of trade openness on the Consumer Price Index, if we replace TO in Equation (3) with and , Pesaran et al. (2001) bounds testing approach is applicable to Equation (8) below:

We can ascertain whether trade openness changes have symmetric or asymmetric effects on the Consumer Price Index once Equation (8) is estimated. The same coefficients of the partial sums in terms of size and sign show a symmetric effect of trade openness on the Consumer Price Index; if otherwise, the effect is asymmetric.

3.2.3. Diagnostic Analysis

In conducting this research, we aimed to identify the model using best practice methodologies. The NARDL bounds testing approach is grounded in the fundamental assumption of homoscedasticity, where errors are assumed to be independently and uniformly distributed. To detect the presence of serial correlation, we employed the Breusch–Godfrey Serial Correlation LM test, while the Jarque–Bera test was used to assess the normality of errors within the model [55]. To determine whether the model exhibits heteroscedasticity, we conducted the Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey and ARCH tests.

3.2.4. Stability Test

Model stability is crucial, particularly for models with autoregressive components, which are often inherent. Following the approach of Pesaran (2001), the model’s reliability was evaluated using the recursive CUSUM and CUSUM of squares tests, with necessary modifications as appropriate [69].

4. Results and Discussion

The descriptive statistics are shown in the upper part of Table 2, and the five variables used in the correlation analysis are listed below. From the correlation matrix results presented at the bottom of Table 2, it is observed that CO2 emissions, labor force, and trade openness have a positive correlation with the Consumer Price Index, while Foreign Direct Investment shows a negative correlation with the Consumer Price Index. Studies indicates that conducting correlation tests among the variables of interest allows the researcher to detect potential multicollinearity, which could lead to estimates that contradict economic theory due to the impact of multicollinearity among the explanatory variables [70]. Nonetheless, multicollinearity is considered significant only when the correlation exceeds 0.95 [71]. According to the results presented in Table 2, all correlation coefficients are below 0.95, suggesting no likelihood of multicollinearity among the independent variables.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and correlation.

4.1. Unit Root Results

Before applying the ARDL method, it is crucial to ensure that no series are stationary at I(2), as this would invalidate the results. To verify this, two different unit root tests, Augmented Dickey–Fuller (ADF) and Phillips–Perron (PP), were conducted on each series. The results indicated that none of the series are stationary at I(2). Therefore, the findings from these unit root tests, as presented in Table 3, confirm that the NARDL model can be applied to the series used.

Table 3.

Unit root results.

In the autoregressive distributed lag model, different lag orders can be specified for dependent and independent variables. The results of various lag selection criteria tests are shown in Table 4. The AIC, SC, and HQ are known to help in identifying the right lag period for these variables. As for the lag selection, we used the AIC and it shows that a lag of two(*) best fits our model

Table 4.

Criteria for lag length.

4.2. Diagnostic Test of the Model

Table 5 provides features of the different diagnostic statistics which are used to check the model fit. The results of the Breusch–Godfrey LM test indicate that there are no problems with serial correlation in the model. To test for heteroscedasticity, we employed the Breusch–Pagan–Godfrey test and ARCH test and found no heteroscedasticity problems in the current study. Also, the Jarque–Bera test reveals that the residuals of the model are normally distributed. The R-squared value confirms the fact that the model fits the data perfectly.

Table 5.

Diagnostic statistics.

The F-statistics used in cointegration testing are presented in Table 6 below. The calculated F-statistics are higher than the upper bound for 10%, 5%, 2.5%, and 1%. Hence, the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected and the existence of long-term relationships among the variables of the model can be confirmed at 10%, 5%, 2.5%, and 1% significance levels [65].

Table 6.

Bound test for cointegration.

Table 7 presents the NARDL model results, highlighting both short-term and long-term asymmetric relationships. In the short term, a positive shock in trade openness (TO+) significantly reduces the CPI by approximately 5.36%, while a negative shock (TO−) also leads to a decrease in the CPI, though by a smaller magnitude of 1.47%, as reported in upper part of Table 7. This indicates an asymmetric relationship between trade openness and the CPI in the short run, with both positive and negative shocks exerting downward pressure on inflation. Furthermore, CO2 emissions have a substantial and significant negative effect, as a 1% increase in CO2 reduces the CPI by about 5.1%. Although the direct short-term impact of FDI on the CPI is insignificant, lagged FDI positively affects the CPI, indicating that Foreign Direct Investments may increase inflation over time. The labor force (LF) contributes to a reduction in the CPI in both the short and long run, reflecting the negative effect of labor force expansion on inflationary pressures. In contrast, the long run reveals a positive and significant effect of positive shocks in trade openness (TO+), where a 1% increase raises the CPI by 11.02%, while negative shocks (TO−) continue to reduce the CPI, as highlighted in the lower part of Table 7. Additionally, CO2 emissions and labor force participation maintain their negative long-term impact, further dampening the CPI by 3.14% and 7.00%, respectively. The error-correction coefficient is negative and statistically significant, indicating that approximately 138% of the disequilibrium from the previous period is corrected in the current period, suggesting a rapid adjustment toward long-term equilibrium. This adjustment time estimate aligns with the findings of [52], confirming that a higher, particularly negative, ECM coefficient signifies a shorter adjustment time.

Table 7.

Long-term and short-term estimates of NARDL.

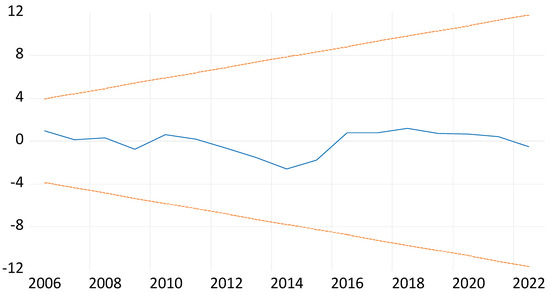

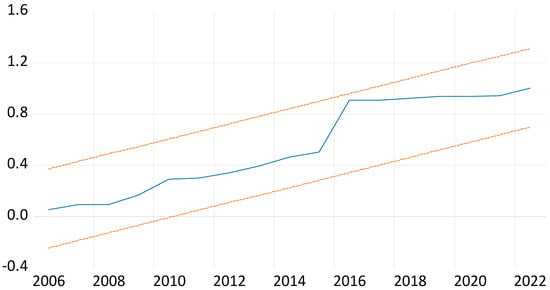

4.3. Model Stability Results

To test the structural stability of the long-term dynamics and validate the short-term findings for Saudi Arabia, the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ tests were employed on the model parameters as proposed by [69]. The results are displayed in Figure 3 and Figure 4. Both figures show the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ plots along with the 5% significance boundaries. The solid line represents the cumulative sum (CUSUM or CUSUMSQ) of the residuals, while the dashed lines represent the 5% significance boundary (critical lines). If these boundaries are crossed, it would indicate instability in the model parameters. However, as can be observed, the CUSUM and CUSUMSQ plots remain within the critical bounds at the 5% level, suggesting that the model’s parameters are stable over time.

Figure 3.

CUSUM at 5% significance level.

Figure 4.

CUSUM of square at 5% significance level.

5. Discussion

Overall, this study confirmed the hypotheses, demonstrating significant relationships between CO2, labor force, FDI, trade openness, and the CPI in Saudi Arabia. Hypothesis 1 posited that CO2 emissions have a negative impact on the CPI. The study found that a 1% increase in CO2 emissions led to a significant 12.15% decrease in the CPI, indicating an inverse relationship between environmental factors and consumer prices. Hypothesis 2 suggested that the labor force has a positive effect on the CPI. The results indicated that a 1% increase in labor force resulted in an approximate 1.32% rise in the CPI, suggesting that a growing workforce contributed to higher consumer prices. According to Keynesian principles, which predict that a growing labor force will boost production capacity because it exerts upward pressure on wages, the larger labor force eventually raised consumer prices [68].

Hypothesis 3 examined the influence of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) on the CPI, revealing that a 1% increase in FDI corresponded to an approximate 0.45% increase in the CPI. This finding highlighted the role of foreign investment in driving consumer price levels. Hypothesis 4 addressed trade openness, showing that a 1% increase in trade openness led to an approximate 3.86% increase in the CPI. This indicated that greater integration into global markets elevated consumer prices. Keynesian theory suggests that increased demand from FDI and trade openness is expected to increase consumer prices as greater capital inflows and market competition influence production costs and pricing dynamics [68].

The present study demonstrates a clear direction towards the relationship of CO2 emissions, the labor force participation rate, FDI, trade openness, and the CPI in Saudi Arabia. The ARDL model results reveal insightful dynamics between CO₂ emissions, FDI, labor force participation, trade openness, and CPI in Saudi Arabia, offering a deeper understanding of the economic and environmental factors shaping inflation. In the long run, CO2 emissions show a significant negative impact on the CPI, with a 1% increase leading to a 12.15% drop in prices. This suggests that sectors contributing to CO2 emissions may drive down consumer prices through increased efficiency or lower production costs, an insight supported by studies linking economic activity to emission reductions [36,56]. FDI, on the other hand, has a modest inflationary effect, where a 1% rise in FDI causes a 0.45% increase in the CPI, reflecting how foreign investments boost economic activity and demand, which can drive inflation [47]. Similarly, labor force participation leads to a 1.32% rise in the CPI for every 1% increase, as more people in the workforce increase productivity and spending, thus pushing prices higher [27]. Trade openness, too, contributes to higher prices, with a 3.86% increase in the CPI linked to global market integration, where rising demand for imports and heightened economic competition push up prices [24]. In the short run, CO2 emissions maintain their deflationary influence, lowering the CPI by 10.45%, suggesting that economic activities tied to emissions initially lead to lower consumer costs [60]. Interestingly, labor force participation, when lagged, reduces the CPI by 21.86%, indicating that while labor initially inflates prices, market adjustments over time help ease inflationary pressures [16]. Trade openness, in the short term, also lowers prices, with a 2.86% reduction, possibly due to access to cheaper imports, although this effect reverses in the long run as global demand increases [24]. With an error correction coefficient of −0.7782, the results show that the system quickly returns to equilibrium, correcting 77.82% of deviations each period [52]. For policymakers, these findings offer a roadmap for navigating the complex interactions between economic growth and environmental sustainability under Vision 2030. While reducing CO2 emissions could help control inflation, the inflationary effects of FDI, labor force participation, and trade openness require careful management to maintain economic stability. Balancing these factors will be crucial as Saudi Arabia diversifies its economy and strives for sustainable development [16].

Overall, this study confirmed the hypotheses, demonstrating significant relationships between CO2, labor force, FDI and trade openness and the CPI in Saudi Arabia. Hypothesis 1 posited that CO2 emissions have a negative impact on the CPI. The study found that a 1% increase in CO2 emissions led to a significant 12.15% decrease in the CPI, indicating an inverse relationship between environmental factors and consumer prices. Hypothesis 2 suggested that the labor force has a positive effect on the CPI. The results indicated that a 1% increase in the labor force resulted in an approximate 1.32% rise in the CPI, suggesting that a growing workforce contributes to higher consumer prices. According to Keynesian principles, a growing labor force will boost production capacity because it exerts upward pressure on wages, eventually raising consumer prices [68].

Hypothesis 3 examined the influence of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) on the CPI, revealing that a 1% increase in FDI corresponded to an approximate 0.45% increase in the CPI. This finding highlights the role of foreign investment in driving consumer price levels. The study confirms the asymmetric impact of trade openness on the CPI, as hypothesized in H4a and H4b. The findings suggest that positive trade openness (H4a), which signifies increased integration into global markets, exerts upward pressure on consumer prices in the long run. Specifically, a 1% increase in positive trade openness (TO⁺) leads to an approximate 11.02% increase in the CPI, reflecting heightened demand for imports and increased competition. This aligns with Keynesian theory, which links greater economic openness to inflationary pressures driven by higher production costs and increased demand from global markets.

On the other hand, negative trade openness (H4b) has a more complex and variable impact on the CPI. In the short run, a negative shock to trade openness (TO⁻) reduces the CPI by 1.47%, indicating that lessened openness or reduced market access can temporarily decrease consumer prices, possibly due to lower import demand or competitive pricing adjustments. However, the long-term effects of negative trade openness are context-dependent and can either dampen or elevate prices depending on external factors such as market conditions and trade policies [68].

The present study demonstrates a clear direction towards the relationship of CO2 emissions, labor force participation rate, FDI, trade openness, and the CPI in Saudi Arabia. The ARDL model results reveal insightful dynamics between CO2 emissions, FDI, labor force participation, trade openness, and the CPI in Saudi Arabia, offering a deeper understanding of the economic and environmental factors shaping inflation. In the long run, CO2 emissions show a significant negative impact on the CPI, with a 1% increase leading to a 12.15% drop in prices. This suggests that sectors contributing to CO2 emissions may drive down consumer prices through increased efficiency or lower production costs, an insight supported by studies linking economic activity to emission reductions [36,56]. FDI, on the other hand, has a modest inflationary effect, where a 1% rise in FDI causes a 0.45% increase in the CPI, reflecting how foreign investments boost economic activity and demand, which can drive inflation [47]. Similarly, labor force participation leads to a 1.32% rise in the CPI for every 1% increase, as more people in the workforce increase productivity and spending, thus pushing prices higher [27]. Trade openness, too, contributes to higher prices, with a 3.86% increase in the CPI linked to global market integration, where rising demand for imports and heightened economic competition push up prices [24]. In the short run, CO2 emissions maintain their deflationary influence, lowering the CPI by 10.45%, suggesting that economic activities tied to emissions initially lead to lower consumer costs [60]. Interestingly, labor force participation, when lagged, reduces the CPI by 21.86%, indicating that while labor initially inflates prices, market adjustments over time help ease inflationary pressures [16]. Trade openness, in the short term, also lowers prices, with a 2.86% reduction, possibly due to access to cheaper imports, although this effect reverses in the long run as global demand increases [24]. With an error correction coefficient of −0.7782, the results show that the system quickly returns to equilibrium, correcting 77.82% of deviations each period [52]. For policymakers, these findings offer a roadmap for navigating the complex interactions between economic growth and environmental sustainability under Vision 2030. While reducing CO2 emissions could help control inflation, the inflationary effects of FDI, labor force participation, and trade openness require careful management to maintain economic stability. Balancing these factors will be crucial as Saudi Arabia diversifies its economy and strives for sustainable development [16].

6. Conclusions

This study offers a comprehensive analysis of the interplay between CO2 emissions, labor force participation, Foreign Direct Investment, trade openness, and the Consumer Price Index in Saudi Arabia. The empirical results underscore a multifaceted dynamic in which CO2 emissions exert a substantial negative impact on the CPI, indicating an inverse relationship. Specifically, a 1% increase in CO2 emissions correlates with a notable 12.15% decrease in the CPI. This suggests that sectors associated with higher emissions might experience cost efficiencies or reduced production costs that subsequently lower consumer prices. These finding challenges conventional economic theories which often associate higher emissions with increased costs and prices.

Conversely, the study confirms that labor force participation, FDI, and trade openness contribute positively to the CPI. A 1% rise in the labor force leads to a 1.32% increase in the CPI, reflecting the Keynesian perspective that a larger workforce boosts production capacity and upward wage pressure, which in turn elevates consumer prices. Similarly, FDI has an approximate 0.45% inflationary effect per 1% increase, highlighting its role in stimulating economic activity and demand, which can drive up prices. Trade openness also shows a significant impact, with a 1% increase in trade openness resulting in a 3.86% rise in the CPI, indicative of how greater market integration can influence domestic price levels through increased demand for imports and competitive pressures on local markets.

The long-term analysis reveals that while CO2 emissions generally exert a deflationary pressure, reducing the CPI by 10.45% in the short term, this effect may reverse over time as economic adjustments occur. Labor force participation initially inflates prices but reduces the CPI by 21.86% when lagged, suggesting that the market adjusts over time to labor-induced inflationary pressures. Trade openness, too, initially lowers prices by 2.86% but eventually contributes to price increases as global demand rises.

6.1. Practical Implications

Based on the findings of this study, it can be concluded that environmental and economic factors are of significant influence to the CPI in Saudi Arabia. Analyzing the relationship between these variables as the nation charts its way through the Vision 2030 plan, it is important that policymakers recognize that CO2 emissions, labor force participation, FDI, and trade openness are central to inflation rates. The findings of this paper highlight the evidence that a reduction in CO2 emissions is likely to have a positive effect on the CPI, thus showing that environmentally sound policies can help curb inflation. In this case, the best strategies to employ are those that would address the issues of emissions while at the same time promoting economic development. Also, increasing the employment rate through promotion of education and training lowers unemployment levels and raises productivity, stabilizing the prices of such goods in the marketplace. The findings of this paper in relation to the relationship between FDI and the CPI underscore the importance of the ongoing policies aimed at attracting FDI especially in sectors that facilitate technology acquisition and productivity. The study highlights that positive and negative trade openness exert distinct effects on the CPI, underscoring the need for tailored trade policies. Policymakers should carefully balance encouraging trades to control prices and protecting local industries from the negative consequences of reduced market access. In conclusion, it is crucial to state that the successful implementation of environmental sustainability in economic planning is necessary for long-term viability.

6.2. Theoretical Implications

This paper contributes to the theoretical literature on the effects of environmental conditions on employment characteristics, FDI, trade openness, and consumer price indices. This paper shows that CO2 emissions and the CPI exhibit an inverse relationship, and this is contrary to the existing economic theory in which economic development (often construed as emission) is known to raise general prices. Thus, at the same time, it can be stated that the processes of price formation in an economy might be more multifaceted than is conceived, and the topic remains open for further investigation. Moreover, FDI and the performance of a country’s labor force add jumps to CPI claims, and this is in vindication of the endogenous growth theories of human capital and outward investments. Therefore, these findings support the assertion advanced by neo-classical theory that FDI and increases in the labor force will lead to demand pulling inflation and, hence, enriching the contemporary debate on the nature of inflation in developing countries. The asymmetric effects of positive and negative trade openness on the CPI contribute to the literature by expanding the understanding of how trade openness influences inflation in varying economic contexts. These findings support the view that nonlinear models provide a more nuanced understanding of macroeconomic dynamics. Thus, we suggest that the present research offers some evidence to better understand the relations between different factors and consumer prices, suggesting that much more attention should be paid to the search for the specifics of the characteristics in future. Therefore, the results of the study are the call for a refutation of conventional economic theories and the integration of the complex factors of environmental impacts, relations with labor, and relations with other countries regarding inflation processes.

6.3. Limitations and Future Directions

It is, however, important to understand that this paper is not without its own limitations. The study is limited to the Saudi Arabian context only; therefore, the findings of this study are generalizable to the Saudi Arabian context only. Future research should perhaps subject the findings to comparative analysis based on data collected from other countries to test the generalizability of the results. Furthermore, this study chiefly emphasizes only the CO2 emissions; future research on other greenhouse gasses could enhance the knowledge of environmental effects on inflation. The techniques used are sound, yet the application of more sophisticated econometric techniques and machine learning methods to boost the forecast precision might have been preferable. This study primarily focuses on trade openness in Saudi Arabia; future research could explore the contextual variations in trade openness effects across different countries. Additionally, incorporating other economic variables (e.g., currency fluctuations) could provide a broader perspective on how external shocks influence the CPI. To sum up, enlarging the range of areas under investigation and extending the list of variables studied will give a broader picture of the processes occurring in the mutual interaction of economic and environmental factors affecting consumer prices.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.A and N.R.; methodology, M.B.; software, M.B.; validation, S.A., N.R. and A.A.; formal analysis, M.B. and S.A; investigation, M.B.; data curation, M.B.; writing—original draft preparation, M.B.; writing—review and editing, S.A. and A.A; visualization, N.R.; supervision, N.R.; project administration, A.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Ali, S.; Yusop, Z.; Kaliappan, S.R.; Chin, L.; Meo, M.S. Impact of trade openness, human capital, public expenditure and institutional performance on unemployment: Evidence from OIC countries. Int. J. Manpow. 2022, 43, 1108–1125. [Google Scholar]

- Amran, Y.A.; Amran, Y.M.; Alyousef, R.; Alabduljabbar, H. Renewable and sustainable energy production in Saudi Arabia according to Saudi Vision 2030; Current status and future prospects. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 247, 119602. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, R.; Qattan, A. Vision 2030 and sustainable development: State capacity to revitalize the healthcare system in Saudi Arabia. INQUIRY J. Health Care Organ. Provis. Financ. 2021, 58, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chowdhury, S.; Mok, D.; Leenen, L. Transformation of health care and the new model of care in Saudi Arabia: Kingdom’s Vision 2030. J. Med. Life 2021, 14, 347. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Lee, C.-C. Does technological innovation reduce CO2 emissions? Cross-country evidence. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 263, 121550. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, Q.; Zheng, B.; Zheng, Y.; Tong, D.; Liu, Y.; Ma, H.; Hong, C.; Geng, G.; Guan, D.; He, K.; et al. Co-benefits of CO2 emission reduction from China’s clean air actions between 2013–2020. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 5061. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie, H.; Roser, M. Who Has Contributed Most to Global CO2 Emissions? Available online: https://ourworldindata.org/contributed-most-global-co2?fbclid=IwAR3wFPB_uJPxtA9jX6EPy9OPRhvDmZ7sir7sq2MLFO6xZbLMGkrtb5E77GQ (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Yoro, K.O.; Daramola, M.O. CO2 emission sources, greenhouse gases, and the global warming effect. In Advances in Carbon Capture; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Yao, Y.; Ivanovski, K.; Inekwe, J.; Smyth, R. Human capital and CO2 emissions in the long run. Energy Econ. 2020, 91, 104907. [Google Scholar]

- Zubair, A.O.; Samad, A.-R.A.; Dankumo, A.M. Does gross domestic income, trade integration, FDI inflows, GDP, and capital reduces CO2 emissions? An empirical evidence from Nigeria. Curr. Res. Environ. Sustain. 2020, 2, 100009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, C.; Su, Z.; Zhu, M.; Ren, H. New structural economic growth model and labor income share. J. Bus. Res. 2023, 160, 113644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Quéré, C.; Peters, G.P.; Friedlingstein, P.; Andrew, R.M.; Canadell, J.G.; Davis, S.J.; Jackson, R.B.; Jones, M.W. Fossil CO2 emissions in the post-COVID-19 era. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2021, 11, 197–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knížat, P. Web scraped data in consumer price indices. Stat. J. IAOS 2023, 39, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, K.J.; Levell, P.; O’Connell, M. Multilateral Index Number Methods for Consumer Price Statistics; Economic Statistics Centre of Excellence (ESCoE): London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Li, G.; Luo, J.; Liu, S. Performance evaluation of economic relocation effect for environmental non-governmental organizations: Evidence from China. Economics 2024, 18, 20220080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esaku, S. The long-and short-run relationship between the shadow economy and trade openness in Uganda. Cogent Econ. Financ. 2021, 9, 1930886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mead, D.; Ransom, K.; Reed, S.B.; Sager, S. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on food price indexes and data collection. Mon. Labor Rev. 2020, 143, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonio, M.S.; Rusydiana, A.S.; Soeparno, W.S.I.; Rani, L.N.; Pratomo, W.A.; Nasution, A.A. The impact of oil price and other macroeconomic variables on the islamic and conventional stock index in indonesia. Int. J. Energy Econ. Policy 2021, 11, 418–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voumik, L.C.; Rahman, M.H.; Islam, M.A.; Chowdhury, M.A.S.; Zimon, G. The impact of female education, trade openness, per capita GDP, and urbanization on women’s employment in South Asia: Application of CS-ARDL model. Systems 2023, 11, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahnazi, R.; Shabani, Z.D. The effects of renewable energy, spatial spillover of CO2 emissions and economic freedom on CO2 emissions in the EU. Renew. Energy 2021, 169, 293–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imrani, O.; Hamich, M.; Boulaksili, A. The consumer price index and it effect in the new ecosystems and energy consumption during the sanitary confinement: The case of an emerging country. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the First International Conference on Physical Geography and Physical Processes Landscapes, Jember, Indonesia, 6–17 October 2021; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2022; Volume 975, p. 012006. [Google Scholar]

- Kacou, K.Y.T.; Kassouri, Y.; Evrard, T.H.; Altuntaş, M. Trade openness, export structure, and labor productivity in developing countries: Evidence from panel VAR approach. Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2022, 60, 194–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dix-Carneiro, R.; Goldberg, P.; Meghir, C.; Ulyssea, G. Trade and informality in the presence of labor market frictions and regulations. Econ. Res. Initiat. Duke (ERID) Work. Pap. 2021, 302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baccini, L.; Guidi, M.; Poletti, A.; Yildirim, A.B. Trade liberalization and labor market institutions. Int. Organ. 2022, 76, 70–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, Y.; Costlow, L.; Ebel, A.; Laves, S.; Ueda, Y.; Volin, N.; Zamek, M.; Herforth, A.; Masters, W.A. Retail consumer price data reveal gaps and opportunities to monitor food systems for nutrition. Food Policy 2021, 104, 102148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. The Price Effect of Trade: Evidence of the China Shock and Canadian Consumer Prices; Centre for the Study of Living Standards: Ottawa, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chaback, B. Ben-Joe Consumer Price Index. In Proceedings of the Discovery Day—Daytona Beach Campus, Daytona Beach, FL, USA, 10 April 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Li, T.; Yu, L.; Ma, Y.; Duan, T.; Huang, W.; Zhou, Y.; Jin, D.; Li, Y.; Jiang, T. Carbon emissions of 5G mobile networks in China. Nat. Sustain. 2023, 6, 1620–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatima, S.; Chen, B.; Ramzan, M.; Abbas, Q. The nexus between trade openness and GDP growth: Analyzing the role of human capital accumulation. Sage Open 2020, 10, 2158244020967377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Soonhui, L.E.E. Note on Pattern Changes in Consumer Price Index (CPI) Year-On-Year (YoY) of the Republic of Korea Since the COVID-19 Pandemic via Statistical Analysis. Indian J. Econ. Bus. 2023, 22. Available online: http://www.ashwinanokha.com/resources/1.%20-Seok%20Ho%20CHANG%20and%20Soonhui%20LEE%20-%20final%20version.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Schwalm, C.R.; Glendon, S.; Duffy, P.B. RCP8. 5 tracks cumulative CO2 emissions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 19656–19657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, A.; Wanita, F.; Arisha, R.; Kusuma, A.H.P.; Azhary, Z. Python-Powered Precision: Unraveling Consumer Price Index Trends in Makassar City through a Duel of Long Short-Term Memory and Gated Recurrent Unit Models. Ceddi J. Inf. Syst. Technol. (JST) 2023, 2, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leblebicioğlu, A.; Weinberger, A. Openness and factor shares: Is globalization always bad for labor? J. Int. Econ. 2021, 128, 103406. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, P.; Alakkari, K.; Abotaleb, M.; Singh, P.K.; Singh, S.; Ray, M.; Das, S.S.; Rahman, U.H.; Othman, A.J.; Ibragimova, N.A. Nowcasting India Economic Growth Using a Mixed-Data Sampling (MIDAS) Model (Empirical Study with Economic Policy Uncertainty–Consumer Prices Index). Data 2021, 6, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brutger, R.; Guisinger, A. Labor market volatility, gender, and trade preferences. J. Exp. Political Sci. 2022, 9, 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul-Mumuni, A.; Amakye, K.; Abukari, A.-L.; Insaidoo, M. Modeling trade openness–unemployment nexus in sub-Saharan Africa: The role of asymmetries. Afr. J. Econ. Manag. Stud. 2023, 14, 792–805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinsdorf, M.; Schreyer, P. Measuring consumer inflation in a digital economy. In Measuring Economic Growth and Productivity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 339–362. [Google Scholar]

- Li, L. An empirical analysis of rural labor transfer and household income growth in China. J. Chin. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2023, 14, 106–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, E.; Taveira, J.G.; Labrador, A.; Pio, J.G. Is trade openness a carrier of knowledge spillovers for developed and developing countries? Struct. Chang. Econ. Dyn. 2021, 58, 66–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haqqoni, M.G.A.; Pramana, S. Implementation of marketplace data in the production of Consumer Price Index in Indonesia. Data Sci. 2022, 5, 79–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anser, M.K.; Syed, Q.R.; Apergis, N. Does geopolitical risk escalate CO2 emissions? Evidence from the BRICS countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 48011–48021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amna Intisar, R.; Yaseen, M.R.; Kousar, R.; Usman, M.; Makhdum, M.S.A. Impact of trade openness and human capital on economic growth: A comparative investigation of Asian countries. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veckalne, R.; Humbatov, H. Impact of oil prices on the consumer price index: In the case of azerbaijan, latvia and uzbekistan. TURAN Strat. Arastirmalar Merk. 2023, 15, 341–355. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Ngo, T.Q.; Saydaliev, H.B.; He, H.; Ali, S. How do trade openness, public expenditure and institutional performance affect unemployment in OIC countries? Evidence from the DCCE approach. Econ. Syst. 2022, 46, 101023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handel, M.J. Growth trends for selected occupations considered at risk from automation. Growth 2022, 32, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, A.; Segelhorst, A. Do consumer price indices in oil-producing economies respond differently to oil market shocks? Evidence from Canada. Empir. Econ. 2024, 21, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riofrio, J.; Infante, S.; Hernández, A. Forecasting the Consumer Price Index of Ecuador using Classical and Advanced Time Series Models. In Conference on Information and Communication Technologies of Ecuador, Proceedings of the 11th Ecuadorian Conference (TICEC 2023), Cuenca, Ecuador, 18–20 October 2023; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 128–144. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, B.; Gao, Y. Forecast and Analysis of Shanghai Consumer Price Index based on Markov chain. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Bigdata Blockchain and Economy Management (ICBBEM 2023), Hangzhou, China, 19–21 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Palumbo, L.; Laureti, T. Finding the goldilocks data collection frequency for the consumer price index. Soc. Sci. Res. Netw. 2024, 33, 23–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Chen, H. Revisiting the linkage between financial inclusion and energy productivity: Technology implications for climate change. Sustain. Energy Technol. Assess. 2023, 57, 103275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dankumo, A.M.; Ishak, S.; Bani, Y.; Hamzah, H.Z. Relationship between governance and trade: Evidence from Sub-Saharan African countries. Res. World Econ. 2020, 11, 139–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Peng, D.; Ni, Y.; Jiang, X.; Wang, Z. Trade openness and economic growth quality of China: Empirical analysis using ARDL model. Financ. Res. Lett. 2021, 38, 101488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngouhouo, I.; Nchofoung, T.N. Does trade openness affects employment in Cameroon? Foreign Trade Rev. 2021, 56, 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rois, R.; Basak, T.; Rahman, M.M.; Majumder, A.K. Modified Breusch-Godfrey Test for restricted higher order autocorrelation in dynamic linear model-a distance based approach. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2012, 7, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wang, K.; Xu, L.; Zhang, C.; Balezentis, T. A time-varying distance based interval-valued functional principal component analysis method–A case study of consumer price index. Inf. Sci. 2022, 589, 94–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndlovu, S.E. The High-Frequency Response of the Johannesburg Stock Exchange All Share Index to South African Trade Balance and Consumer Price Index Announcements: An Event Study Approach. Master’s Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Cobbinah, M.; Alnaggar, A. An attention encoder-decoder RNN model with teacher forcing for predicting consumer price index. J. Data Inf. Manag. 2024, 6, 65–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costales, J.A. Cost Modeling and Analysis of the Consumer Price Index in the Philippines. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Software and Computer Applications, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 26 February 2021; pp. 32–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dorn, F.; Fuest, C.; Potrafke, N. Trade openness and income inequality: New empirical evidence. Econ. Inq. 2022, 60, 202–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dickey, D.A.; Fuller, W.A. Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 1979, 74, 427–431. [Google Scholar]

- Kniss, A.R.; Vassios, J.D.; Nissen, S.J.; Ritz, C. Nonlinear regression analysis of herbicide absorption studies. Weed Sci. 2011, 59, 601–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milliken, G.A. Nonlinear Regression Analysis and Its Applications; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth, G.K. Nonlinear regression. Encycl. Environmetrics 2002, 3, 1405–1411. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, N.-H.; Lee, S.-H.; Kim, C.-S. Moving window regression: A novel approach to ordinal regression. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 19–20 June 2022; pp. 18760–18769. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.-L.; Wang, X.-Z.; Huang, J.Z. Fuzzy nonlinear regression analysis using a random weight network. Inf. Sci. 2016, 364, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsalobre-Lorente, D.; Shahbaz, M.; Roubaud, D.; Farhani, S. How economic growth, renewable electricity and natural resources contribute to CO2 emissions? Energy Policy 2018, 113, 356–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó-Szentgróti, G.; Végvári, B.; Varga, J. Impact of Industry 4.0 and digitization on labor market for 2030-verification of Keynes’ prediction. Sustainability 2021, 13, 7703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, R.L.; Durbin, J.; Evans, J.M. Techniques for testing the constancy of regression relationships over time. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Stat. Methodol. 1975, 37, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamsal, M. The Effect of Paradoxical Strategies on Firms’ Positional Advantage and Performance: The Case of Indonesian Banking Industry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Economics and Business Management (EBM-2015), Phuket, Thailand, 29–30 July 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Iyoha, M. Macroeconomics Theory and Policy; Mindex Publishing: Benin City, Nigeria, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Coddington, A. Keynesian economics: The search for first principles. J. Econ. Lit. 1976, 14, 1258–1273. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).