Abstract

This study aims to investigate the demand for ecotourism in marine protected areas by (a) identifying motivations specific to marine protected areas, (b) establishing the relationship between social and demographic variables and motivations, and (c) determining the relationship between social and demographic characteristics, satisfaction, and loyalty variables. The study was conducted in Santa Elena Province at the reserve called “Puntilla”, which is a coastal marine and fauna production reserve in Ecuador, a country renowned for its biodiversity. The sample comprised 369 on-site surveys. Factor analysis and stepwise multiple regression methods were used for data analysis. The results revealed associations between social and demographic variables and tourist motivations. Specifically, lower-income tourists were most motivated by “escape and ego-defensive function motivation” and reported higher satisfaction levels. Conversely, tourists who visited the destination less frequently displayed stronger motivations related to nature and showed high satisfaction. Furthermore, visitors who spent less at the destination demonstrated a greater intention to return and recommend the area to others. These findings hold significant implications for protected areas management and contribute to the scientific literature on ecotourism in similar protected areas.

1. Introduction

Ecotourism destinations are gaining importance due to their contribution to job creation, education, recreation and environmental protection [1]. Stemming from Latin American and Caribbean countries in the 1960s [2], ecotourism emerged as an important sector within the tourism industry. Globally, it has an annual growth rate of 5%, outpacing the overall growth rate of tourism [3]. Ecotourism has also positioned itself as an approach that offers more sustainable opportunities, providing solutions for troubles like economic problems and biodiversity decrease [4]. Although tourism in protected areas that focuses on nature offers a more accessible ecosystem experience for people, it also puts tourism pressure on the ecosystem [5].

Motivation research can yield critical insights for destination management, market planning, and natural or protected areas (product) development [6]. Therefore, motivation research plays an important role in tourism destinations, contributing to the increase in demand and helping visitors make decisions [7,8]. In fact, understanding specific travel motivation expectations is crucial for assessing tourists’ satisfaction with their destination experiences and their subsequent impact on loyalty. Accordingly, gratified tourists are more likely to come back, recommend the destination, or provide supportive word of mouth [9]. Regardless, the relationship changes when factors such as gender, education, and marital status are taken into account [10].

Situated along the Ecuadorian coast, Puntilla Reserve belongs to the coastal marine protected areas of Ecuador. This natural reserve is one of the most popular and visited places on the Ecuadorian coast. Puntilla Reserve is recognized as the most extreme western point of the South American continental coastline. The waters of the reserves are a vital resource for some fishing communities and provide an important opportunity to protect and restore fish stocks that have been depleted by overfishing. In addition to the marine area, this nature reserve also includes beaches, cliffs, and a small area of coastal shrubland and dry forests.

Current scientific literature on the relationship between social and demographic variables and ecotourism motivations in marine protected areas remains lacking. Similarly, little research has been conducted on the relationship between social and demographic characteristics and satisfaction and loyalty, which are important for the sustainability of marine conservation goals. The research hypothesis remains the existence of a relationship between the sociodemographic variables with the motivation, satisfaction, and loyalty variables. Given this research gap, the objectives of this study were to (a) identify motivations specific to marine protected areas, (b) determine the relationships between social and demographic variables and motivations, and (c) determine the relationship between demographic characteristics and satisfaction and loyalty variables. This field study conducted in Ecuador, an ecologically diverse country, provides a theoretical and practical understanding of the sociodemographic characteristics of visitors and their motivations for developing sustainable development strategies in protected areas.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Marine Protected Areas and Ecotourism

Protected areas are important places for ecotourism and tourism because of their unspoiled nature and unique natural structures. Greater awareness of the environment increases the value of protected areas and ecological protection, thus contributing to the long-term development of the ecosystem [11]. Therefore, in countries where economic development levels are not optimal, creating national parks is a viable option for fostering tourism activities [12].

As part of sustainable tourism [13], ecotourism has been an important topic of academic research since its birth [14,15]. Overall, the ecotourism model is widely recognized as a way to improve livelihoods, local culture, and environmental protection [16]. Ecotourism can connect tourists to nature and help them develop stronger relationships with nature [17]. Many areas and regions continue to develop and market products to meet the growing demand for ecotourism products [11,18].

Protected areas can be classified as marine protected areas (MPAs). MPAs have been established as a means of conserving and restoring endangered species, fisheries, and coral reef habitats [19], and as a means of regulating fishing activities while promoting research. It aims to improve environmental protection [20]. MPAs also play a central role in remediating environmental damage and maintaining a wide range of services provided by marine ecosystems [21]. In fact, they are a preferred mechanism to prevent marine biodiversity loss [22]. Well-managed MPAs protect natural habitats and species from numerous local stressors, such as destructive fishing and pollution [23]. Therefore, they are considered to have positive consequences for both nature and human society [24]. In this context, Carvache-Franco et al. [25] point out the attraction of pristine beaches, diverse leisure activities for tourists, crystal clear water and fresh air, and immersive culture with local people. They emphasize that experiential possibilities should dictate the tourism offered in coastal and marine protected areas.

2.2. Motivations in Marine Protected Areas

Motivation is considered one of the most important variables to explain visitor behavior, as it is the central factor in their decision-making process [26]. In this sense, motivations are a psychological need that plays an essential role in making an individual feel that a psychological imbalance can be corrected through a travel experience [27,28].

Previous studies have identified visitor motivations in different tourism environments. For example, Lee et al. [29] analyzed a restored ecological park in South Korea and identified seven motivational factors: self-development, interpersonal relationships, rewards, building personal relationships, escape, ego-defensive function, and nature appreciation. In another study, Jeong et al. [30] compared the motivation and attitudinal segmentation of the tourism market in Kuang Si Waterfall and Kong Lo Cave in the Lao Republic, establishing four motivational dimensions: health, nature, cohesion, and escape. Similarly, Ma et al. [31] investigated the self-determined travel motivation of Chinese tourists visiting protected areas and identified three motivational factors: relaxation and nature exploration, novelty seeking, and social influence. Furthermore, Chow et al. [31] revealed that the main motivations for nature tourism in the Ramsar wetlands in Hong Kong were relaxation, escape from everyday life, and physical and mental health. Finally, in relation to marine reserves and national parks in the Galapagos Islands, Carvache-Franco et al. [32] found six factors: self-development, interpersonal relationships and ego-defense function, escape, relationship building, appreciation of nature, and reward. Also, for Chi and Pham [33], the image of the eco-destination significantly reinforces the effects of four travel motives (i.e., excitement, escape, search for knowledge, and personal development) on the intention of ecotourism. In another more recent study, academics Carvache-Franco et al. [34] in a study in the Posets-Maladeta protected area in Spain, identified nine motivational dimensions: self-development, interpersonal relationships, security measures, establishing personal bonds, escape, ego-defensive function, nature, entertainment, and rewards.

Fundamentally, the motivations for ecotourism vary depending on the destination, but they share certain similarities nevertheless, in aspects such as nature, social interaction, novelty, and escape. Given the paucity of research investigating motivations in marine protected areas and the lack of standardized elements, our first research question is as follows: RQ1: What are the specific motivations for marine protected areas?

2.3. Social and Demographic Variables and Motivations in Marine Protected Areas

The social and demographic characteristics of tourists could be a stable forecaster of motivations. In fact, these attributes are often associated with and intertwined with motivations. Tepavčević et al. [35] highlight that tourists’ motivations and travel constraints tend to vary based on their social and demographic profiles, shaping their travel preferences and reasons.

Previous research in the context of ecotourism has yielded different findings on social and demographic variables. Motivating factors for young travelers include recreation/physical activity, enjoyment of nature, prestige, and impressions, and social interaction [36,37,38,39]. In line with this perspective, Kim et al. [37] argued that younger individuals are more motivated by seeking novelty compared to their older counterparts. Similarly, Luo and Deng [40] found a negative correlation between age and motivation for novelty among tourists from China, suggesting that young tourists seek more novelty. On the other hand, Jang and Feng [41] and Jönsson and Devonish [36] found that old individuals are the ones more motivated by novelty. This opposing viewpoint shows that different criteria have been found when analyzing novelty. Regarding another motivational factor, Ma et al. [31] found that age positively correlates with relaxation and nature exploration. In a recent study, Carvache-Franco et al. [42] found more motivated younger tourists tended to strengthen self-development; on the other hand, older travelers tended to strengthen relationships, including family and friends.

Concerning education level and ecotourism motivations, Jensen [38] identified that visitors with higher educational backgrounds were more motivated toward relaxation, escape, knowledge-seeking, and socialization. Conversely, less educated individuals displayed higher motivation for prestige/impression and novelty. Likewise, Carvache-Franco et al. [42] found that novelty highly motivates tourists with lower educational levels. However, Ma et al. [31] found that there is a negative correlation between educational level and motivation for social influence.

In the context of income and motivations, varying results have emerged from different studies. Jensen [38] found that high-income visitors tended to favor nature appreciation and relaxation and escape, whereas tourists with lower income levels showed a preference for knowledge-seeking. Ma et al. [31] noticed a more significant relationship between monthly income and the motivation for social influence. Finally, Carvache-Franco et al. [42] argued that tourists with low incomes were more motivated to strengthen interpersonal relationships, including family and friends.

Regarding the frequency of visits and motivations, Jang and Feng [41] identified that Canadian tourists seeking novelty motivation positively influenced their intention to make revisits in the coming years. Additionally, Barros and Machado [43], when examining social and demographic aspects and length of stay, found that old, educated male visitors were prone to have longer stays.

In essence, recent findings have indicated an unfavorable correlation between tourists’ ages and novelty motivations. Furthermore, highly educated tourists tend to seek knowledge and socialization, whereas lowly educated tourists lean toward prestige and novelty. Likewise, high-income tourists have demonstrated a preference for motivations related to escape and nature, while tourists with low incomes display a stronger inclination toward knowledge. Therefore, the literature lacks studies of sociodemographic relationships in marine protected areas. Our second research question arises as follows: RQ2: What is the connection between social and demographic variables and motivations in marine protected areas?

2.4. Relationship between Social and Demographic Aspects and Satisfaction and Loyalty in Marine Protected Areas

Turning to specific correlation, both sociodemographic and tourist satisfaction have been the object of many studies. For instance, Tsiotsou and Vasioti [44] conducted a study on the demographics and satisfaction of tourists and found that older individuals with high education levels turned out to be more pleased with their experiences while traveling. Likewise, Ozdemir et al. [45] carried out a study in Türkiye and discovered that well-educated older women with a lower income were positively correlated with higher satisfaction levels. Currently, Carvache-Franco et al. [42] identified that low-educated tourists are more satisfied with their visit and are more inclined to recommend and give favorable word of mouth about the tourist attraction. Moreover, their study also noted that regular visitors are interested in revisiting the destination.

These findings show limited literature on the correlation between social and demographic variables and their impact on satisfaction and loyalty in marine protected areas. While some studies have indicated a positive association between higher age, educational levels, and increased satisfaction, there is a notable scarcity of research on this specific subject in the context of marine protected areas. Therefore, the research gap opens up opportunities toward finding the relationships between sociodemographic variables and satisfaction and loyalty in the context of marine protected areas. Hence, our third research question emerges as follows: RQ3: What is the connection among variables like social and demographic characteristics, satisfaction, and loyalty in marine protected areas?

3. Study Area

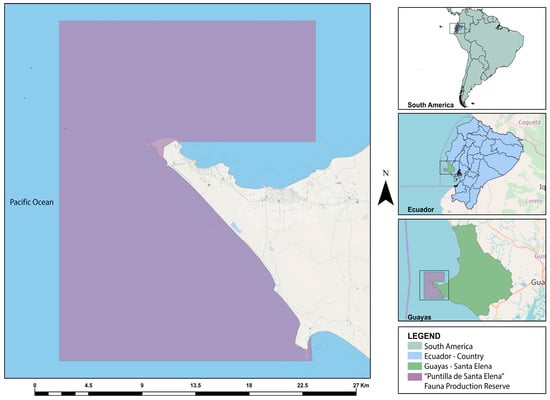

Puntilla Reserve was created in 2008 and is the primary protected area in Santa Elena, Ecuador. This country’s four regions are rich in biodiversity, reporting 91 ecosystems with 15% of the world’s endemic species [46]. This reserve has 52,231 marine hectares and 203 hectares of land, including coastal marine areas, cliffs, and rocky landscapes. Notably, tourism development within this area has not posed a threat to conservation efforts; however, erosion by wind or water along the impact zone between the ocean and the mainland has led to gradual degradation (See Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Location: Puntilla Reserve (Ecuador).

The marine and land ecosystems of Puntilla Reserve are influenced by the intertropical convergence zone, showing a predominantly dry climate with annual variations in precipitation and temperature. This pattern causes two seasons: dry and cold days (from June to November), followed by warm and rainy days (from December to May). From July to September, migrating whales such as the Humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae), Sei whale (Balaenoptera borealis), and Bryde’s whale (Balaenoptera edeni) are observed within these waters, including six other whale species.

Stationary animals like the South American fur seal (Otaria flavescens) and the Galapagos fur seal (Artocephalus galapagoensis) are found in an area commonly referred to as “La Lobería”. In addition, around 16 marine mammals, 60 birds, and 3 types of turtles (hawksbill turtles, green turtles, and pacific olive ridley turtles) use this place as their feeding area. Moreover, the reserve trails are home to reptiles, for instance, the common iguana (Iguana iguana), lizard Microlophus occipitalis (Tropiduridae), and Ameiva sp. (Teiidae) [45].

Sports activities like surfing and bodyboarding are performed extensively; some prestigious surfing events like the US Open of Surfing (2004) [47] and the World Junior Surfing Championship (2009) [48] were held in FAE and Punta Brava Beaches, where we can find wooden facilities. Also, organizers of these events recognized the attractiveness and great beach conditions for these water sports mentioned. Furthermore, visitors can also enjoy walking and cycling along the trails, while photographers can seize the opportunity to capture images. Near the reserve, 17.6 km away, lies clues of early civilization known as Vegas (10,800 BC–6600 BC) [49] and Valdivia civilization (5600 BC–3500 BC) [50], who created some of the oldest ceramics in South America.

4. Methodology

This study is part of a project approved by the Research Dean of the ESPOL University and the ESPOL Ethics Committee under Code CIEC-16-2015. This population sample consisted of both Ecuadorian residents and visitors from abroad, facilitating us to carry out an on-site study in Puntilla Reserve. Informed consent was requested in writing from respondents when filling out the surveys. The surveys were administered between January and March 2019, when visitors typically took breaks after their tours. Trained and skillful interviewers conducted surveys and helped respondents on the spot. No ethical problems were found.

The questionnaire was devised comprising various sections to fulfill the research objectives:

First, we gathered respondents’ profiles and visit characteristics using closed-ended questions adapted from the study by Lee et al. [29].

Second, we concentrated on motivations using a 34-item scale rated on a Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not important) to 5 (very important). This scale helps to measure respondents’ points of view [29]. The reliability of the motivation scale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, resulting in a value of 0.94, which indicates high internal consistency.

Third, we included questions about visitors’ overall satisfaction, intentions to revisit, and likelihood of recommending the ecotourism destination. Satisfaction was evaluated using a five-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (not satisfied at all) to 5 (very satisfied). Similarly, intentions to return, recommend, and word-of-mouth point of view were measured using the same Likert scale but with different labels (totally disagree = 1 to totally agree = 5). The scales assessing satisfaction and loyalty were adapted from Kim and Park’s [51] research.

Notably, convenience sampling was used based on tourists’ accessibility to the protected area and willingness to participate in the questionnaire. To reduce the bias of the method due to convenience, the diversity of the population was taken into account, so the samples were recognized on different days of the week, weekends, and daytime hours, and the samples were taken in different geographical points of the marine area protected, which allowed us to reduce bias and increase the representativeness of the sample. This study had limitations in the generalization of the results because the sample was taken in a specific marine protected area. This study was limited to a sample size of 369 participants, with a sampling error of 5%, which was an acceptable value for this type of study. Population variability was set at 50% (p = q = 0.5) for the sample size, which resulted in 369. Additionally, it was considered to have a margin of error of 5% and a confidence level of 95%. The data were organized, tabulated, and analyzed in SPSS 22.0, comprising two stages of analysis.

Initially, we identified constructs underlying the variables by applying a factor analysis, which, in tourism research, is a commonly used method [52,53,54]. We also applied varimax rotation to interpret the data. The Kaiser criterion helped to determine the quantity of factors to keep such as those with eigenvalues greater than 1. Particularly, the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) index and Bartlett’s sphericity test indicated the suitability to conduct this analysis.

Finally, we used multiple regression analysis to identify relationships between variables and factors such as motivations, satisfaction, and loyalty. Only variables demonstrating statistical significance (p < 0.05) were considered for establishing these relationships. The sign of the beta coefficient was used to determine whether the relationship was positive or negative.

5. Results

5.1. Social and Demographic Characteristics of the Sample

In this study, the sample comprised 369 respondents. Gender was distributed as 49.9% male and 51.1% female. A total of 51.5% of the respondents were single, while 36.6% were married. Concerning age, 37% fell between 21 and 30 years old, and 30.6% were between 31 and 40 years old. In terms of their educational background, 58.3% had university studies while 27.1% had completed high school.

Turning to labor activity, 27.4% of the respondents were employed, and 23.8% were students. Concerning travel companions, 45.5% of the visitors were accompanied by family members, while 30.4% were traveling with friends. As for the frequency of visits, most respondents (41.5%) were visiting Puntilla Reserve for the first time, compared to 24.1% who had visited more than three times. Concerning income levels, 32.2% reported monthly incomes ranging from USD 501 to USD1000, while 15.2% reported incomes from USD 1001 to USD 1500. Regarding average expenses per person in one day, 42.8% spent between USD 30 and USD 60 per day, while 32.5% spent less than USD 30. See Table 1 for the detailed information.

Table 1.

Social and demographic variables.

5.2. Motivations in a Marine Protected Area

Our factor analysis reduced motivational variables into a smaller number of factors and facilitated interpretation of the results. The Varimax rotation method was applied to obtain an adequate factor solution, and the Kaiser criterion was employed to determine the factors with eigenvalues greater than 1.00. This analysis yielded six factors explaining 66.66% of the total variance. The KMO index (Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin) had a result of 0.925, indicating a favorable fit. Additionally, Bartlett’s test of sphericity was significant at <0.05, confirming the suitability of applying factor analysis (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Motivations in a marine protected area.

As shown in Table 2, the analysis revealed distinct visitors’ motivations in marine protected areas. The first dimension accounted for 38.96% of the explained variance and was labeled “Self-development and Interpersonal Relationships”. This factor is associated with personal skill growth and relationships with family and friends. The second dimension accounted for 7.97% of the explained variance and was named “Building Personal Relationships” as it is about establishing relationships with tourists with similar interests and willingness to interact with locals. The third dimension represented 61% of the explained variance and was named “Escape and Ego-defensive Function”. This factor is linked to motivations to escape from routine and daily stress and engage with society. The fourth factor was labeled “Marine Nature” due to its association with appreciating fauna and flora, learning from nature, and enjoying the sun and beach. This dimension accounted for 4.65% of the explained variance. The fifth dimension was “Terrestrial Nature” and was related to motivations for observing flora, fauna, and landscapes. This factor consisted of 4.19% of the explained variance. The last factor was named “Rewards” and was linked with the motivation to acquire new memories. This dimension represented 3.30% of the explained variance. These results answered our first research question, RQ1: What are the specific motivations for marine protected areas?

5.3. Social and Demographic Variables and Motivational Dimensions in a Marine Protected Area

The analysis of the significant social and demographic predictors of motivations was conducted using multiple regression methods, as outlined in Table 3.

Table 3.

Social and demographic variables and motivational dimensions.

As shown in the third table, professional activity was a significant positive predictor of motivation for “Self-development and Interpersonal Relationships”. This suggests that tourists’ motivation for personal growth and engaging in relationships with family and friends depends on their professional activity. Conversely, the income level or monthly income negatively correlated with the motivation for “Escape and Ego-defensive Function”. Consequently, lower-income tourists were more motivated to escape from routine and daily stress.

The study also identified the social and demographic predictors associated with the motivational dimension of “Terrestrial Nature” (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Social and demographic variables and the motivational dimension “Terrestrial Nature”.

According to the results in Table 4, the frequency of visits to the destination emerged as a significant negative predictor of “Terrestrial Nature”. This indicates that tourists visiting the marine protected area less frequently can exhibit a higher motivation toward observing terrestrial flora, fauna, and landscapes.

5.4. Social and Demographic Variables and Satisfaction

We used multiple regression analysis to analyze significant predictors linked to social and demographic variables with the level of satisfaction (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Social and demographic variables and level of satisfaction.

Based on the findings in Table 5, the frequency of visits to Puntilla Reserve emerged as a significant negative predictor of satisfaction. This suggests that tourists who visit these areas less frequently have higher satisfaction levels. Conversely, the average income level demonstrated a significant negative correlation with satisfaction, indicating that lower-income tourists were the most satisfied in the marine protected area. This could mean that the destination should offer low-priced products and services to keep tourists satisfied.

5.5. Social and Demographic Variables of Intentions to Return and Recommend

The significant social and demographic predictors of intentions to revisit and recommend the destination were analyzed through multiple regression analysis (see Table 6).

Table 6.

Social and demographic variables and intentions to return and recommend the marine protected area.

According to Table 6, the frequency of visits to the marine protected area emerged as a significant positive forecaster of intentions to return to the destination. Therefore, tourists who visit protected marine areas more frequently are also more inclined to revisit them. Conversely, the average daily expenditure per person exhibited a significant negative correlation with intentions to return. This indicates that tourists who spend less are more likely to revisit the marine protected area. This could mean that the destination is visited by lower-income tourists interested in spending less while enjoying the destination.

Moreover, the frequency of visits significantly positively predicted intentions to recommend the destination. This suggests that tourists who visit the area more frequently are more inclined to recommend it. Therefore, the tourists who visited the destination the most were those who recommended it the most. This could mean that the reputation of the destination depends more on which tourists visit the marine protected areas.

On the contrary, the average daily expenditure per person showed a significant negative correlation with intentions to recommend, implying that tourists who spend less have higher intentions to recommend the protected marine area to others. This could mean that the tourists who had the least income are the ones who would recommend these destinations the most. Therefore, the income of tourists is a fundamental variable in this study.

5.6. Social and Demographic Variables and Positive Word of Mouth About the Destination

We used multiple regression analysis to analyze the significant social and demographic predictors of positive word of mouth about the protected area (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Social and demographic variables and positive word of mouth about the destination.

Based on the findings presented in Table 7, the frequency of visits to the destination emerged as a significant positive predictor of positive word-of-mouth about the protected marine area. Consequently, individuals who visit the destination more frequently tend to express more positive opinions about it. This suggests that the reputation of the destination could depend on the tourists who visit it the most. Conversely, the income level demonstrated a significant negative correlation with positive word of mouth about the marine protected area. This implies that lower-income tourists are more likely to give positive feedback about the destination. These results address our third research question: RQ3: What is the relationship between social and demographic characteristics, satisfaction, and loyalty variables in marine protected areas?

6. Discussion

The first objective of this research is to identify tourist motivations in marine protected areas. In this regard, the results are consistent with previous studies. First, the dimension “Self-development and Interpersonal Relationships” discovered in this study is similar to the factors found in the studies by Lee et al. [29] and Carvache-Franco et al. [32]. Moreover, the motivational dimension of “Building Personal Relationships” mirrors the “Development of personal relationships” reported by Lee et al. [29] and later on by Carvache-Franco et al. [32] and Carvache-Franco et al. [34]. Chi and Pham [33] also found it as a search for knowledge and personal development. Additionally, the dimension “Escape and Ego-defensive Function” is similar to the “Escape” dimension found in the investigations by Lee et al. [29]. Carvache-Franco et al. [34] and Jeong et al. [30] and “Escape from everyday life” by Chow et al. [31]. Furthermore, the “Ego-defensive Function” dimension was also identified by Lee et al. [29], Carvache-Franco et al. [32], and Carvache-Franco et al. [34]. Moreover, the dimension “Marine Nature” was discovered as well by Jeong et al. [30] and is similar to the “Exploration of Nature” dimension obtained by Ma et al. [31]. Likewise, this study identified the dimension “Terrestrial Nature”, which was also established by Lee et al. [29], Jeong et al. [30], and Carvache-Franco et al. [32]. Finally, the “Rewards” dimension observed in this study exhibits similarities with the factors found by Lee et al. [29], Carvache-Franco et al. [32], and Carvache-Franco et al. [34].

The second objective of this research aimed to establish the relationship between social and demographic variables and motivations. This study found that income level significantly negatively predicted “Escape and Ego-defensive Function”. These results contrast with findings by Jensen [38], who identified that higher-income tourists favored escape and relaxation, while those with lower incomes were more inclined toward knowledge seeking. Additionally, Carvache-Franco et al. [42] found that low-income tourists were primarily motivated toward strengthening interpersonal relationships with family and friends. Furthermore, this study identified that the frequency of visits was a significant negative predictor of the “Terrestrial Nature” dimension. Such results are novel in the existing literature and represent a valuable contribution by finding that less frequent visitors are more motivated by some of the on-land activities of the destination. Equally noteworthy is the discovery that lower-income tourists are most motivated by the “Escape and Ego-defensive Function” dimension, adding unique insights to the literature.

Another objective was to determine the relationship between social and demographic characteristics and loyalty and satisfaction variables. This study found that the frequency of visits to the destination was a significant negative predictor of satisfaction, a unique discovery not previously reported in the literature. This indicates that tourists who visit the destination less frequently are the most satisfied. Additionally, this study identified that the average income was a significant negative predictor of satisfaction, partly aligning with the findings by Ozdemir et al. [45], who explained that older, highly educated women with lower incomes displayed higher satisfaction levels.

Furthermore, this research revealed that the frequency of visits positively predicted intentions to revisit and recommend the marine protected area. The relationship between average daily expenditure per person and intentions to revisit and recommend the destination is another noteworthy finding, suggesting that tourists who spend less have higher intentions to return and recommend Puntilla Reserve. These results have not been found in previous studies, representing a contribution of this paper to the scientific literature. These novel discoveries shed light on the relationships between visitation patterns, spending behavior, satisfaction, and intentions to revisit or recommend, a valuable contribution to understanding tourist behavior in protected areas.

Among its theoretical implications, this study found that tourists who visit the destination less frequently are the most motivated by the terrestrial nature of the area and are the most satisfied. Furthermore, tourists with lower monthly incomes are the most motivated by the “Escape and Ego-defensive Function” dimension. This study also identified that tourists who visit the marine protected area more frequently or spend less money demonstrate a stronger intention to revisit and recommend the destination.

This study offers practical implications for tourism businesses by emphasizing the importance of considering tourists’ social and demographic characteristics to create activities and services linked to social variables (motivations, satisfaction, and loyalty). To improve motivation, self-development, interpersonal Relationships, and building personal relationships, tourist packages could be organized where people can meet friends and enjoy the visit. Learning workshops can also be created, such as marine flora and fauna watching, craft making, and water sports, so that visitors can develop knowledge and, at the same time, improve their social relationships.

To improve the “Escape and Ego-defensive Function” dimension, it is advisable to organize activities and events in the marine protected area, such as games, recreational activities, and sports competitions, so that people can organize getaways and increase enjoyment in the protected area. To increase Marine Nature’s motivation, scientific courses could be created to learn about marine flora and fauna. Recreational sun and beach activities could also be created, such as visits to viewpoints, games on the beach, and hiking or snorkeling. To improve the Terrestrial Nature dimension, walks and workshops could be carried out to learn more about the terrestrial flora and fauna with environmental education. Also, to improve the Rewards factor, guided tours could be carried out with adequate interpretation of the tourist packages combined with recreational activities.

Because it has been identified that professional activities were a significant positive predictor of motivation for “self-development and interpersonal relationships”. It is recommended to create tourist packages aimed at professionals where self-development activities are included in the visit to the protected area and group dynamics are carried out to meet with friends with similar interests. Also, low-income tourists were more motivated to escape routine and daily stress. It is recommended that recreational activities in the marine protected area should not be expensive to attract tourists. Low-income tourists could benefit from innovative activities that help them escape their daily routines. Those who have visited the marine protected area less frequently will be able to look for activities focused on the observation of flora, fauna, and landscapes, and likewise, tourists who visit the marine protected area less frequently may exhibit greater motivation toward observing the flora, fauna, and terrestrial landscapes. They could be offered workshops on sightings of marine flora and fauna so that, in addition to their taste for terrestrial nature, they increase their frequency of visits and have other recreational activities. Furthermore, offering novel activities at affordable prices could increase the satisfaction levels of less frequent visitors and people with lower incomes. Finally, in terms of loyalty, it is recommended that offering services and activities at low and accessible prices can encourage repeat visits, recommendations, and positive word of mouth from tourists with lower spending habits.

7. Conclusions

Social and demographic variables exhibit relationships with motivations, satisfaction, and loyalty, allowing for the differentiation of tourist segments, a critical aspect in designing activities and services.

This study has identified six motivational dimensions in marine protected areas: Self-Development and Interpersonal Relationships, Building Personal Relationships, Escape and Ego-defensive Function, Marine Nature, Terrestrial Nature, and Rewards.

Regarding social and demographic variables and motivations, this study found that lower-income tourists were the most motivated by the “Escape and Ego-defensive Function” dimension and were the most satisfied. In contrast, tourists who visited the marine protected area less frequently were more motivated by the destination’s terrestrial nature and showed high satisfaction. Conversely, tourists who spent less demonstrated stronger intentions to return and recommend Puntilla Reserve.

Findings demonstrate that tourists in marine protected areas prefer destinations that are not financially demanding, favoring affordable places that offer unique natural attractions related to flora, fauna, and landscapes. Additionally, these destinations should provide experiences that take visitors beyond their everyday routine.

This study also found that tourists who visit the destination less frequently or have lower monthly incomes are more motivated by nature and escape. Conversely, those who visit the marine protected area more often or spend less are more willing to revisit and recommend the destination.

This study can help businesses plan activities and services based on tourists’ motivations, satisfaction, and loyalty. Its results suggest that creating diverse and innovative activities will help tourists escape their daily routines, such as offering them opportunities to observe flora, fauna, and landscapes in these protected areas. Moreover, services should be reasonably priced to ensure high satisfaction and foster loyalty, particularly among lower-income tourists seeking cost-effective experiences within these destinations.

This study had a specific limitation related to the sample collection and timing. Future research should explore the relationships between social and demographic variables with the segmentation of ecotourist demand in marine protected area settings.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.C.-F., O.C.-F., J.B.-M. and W.C.-F.; methodology, M.C.-F., O.C.-F. and W.C.-F.; software, M.C.-F. and O.C.-F.; validation, M.C.-F., O.C.-F., J.B.-M. and W.C.-F.; investigation, M.C.-F., O.C.-F., J.B.-M., S.B.-R., A.A.-T. and W.C.-F.; writing—original draft preparation, M.C.-F., O.C.-F., J.B.-M., S.B.-R., A.A.-T. and W.C.-F.; writing—review and editing, M.C.-F., O.C.-F., J.B.-M., S.B.-R., A.A.-T. and W.C.-F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Tao, T.C.; Wall, G. Tourism as a sustainable livelihood strategy. Tour. Manag. 2009, 30, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundstrom, S. El Ecoturismo Como Instrumento Para Desarrollo Sostenible. Un estudio comparativo de campo entre Suecia y Ecuador. 2003. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:6392/FULLTEXT01.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Hultman, M.; Skarmeas, D.; Oghazi, P.; Beheshti, H.M. Achieving tourist loyalty through destination personality, satisfaction, and identification. J. Bus. Res. 2015, 68, 2227–2231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabral, C.; Dhar, R.L. Ecotourism research in India: From an integrative literature review to a future research framework. J. Ecotourism 2020, 19, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chun, J.; Kim, C.K.; Kim, G.S.; Jeong, J.; Lee, W.K. Social big data informs spatially explicit management options for national parks with high tourism pressures. Tour. Manag. 2020, 81, 104136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, L.T.; Fok, L. The motivations and environmental attitudes of nature-based visitors to protected areas in Hong Kong. Int. J. Sustain. Dev. World Ecol. 2014, 21, 28–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, F.; Azam, M.S.; Bose, T.K. Factors affecting the selection of tour destination in Bangladesh: An empirical analysis. Int. J. Bus. Manag. 2010, 5, 52. [Google Scholar]

- Alegre, J.; Cladera, M. Analysing the effect of satisfaction and previous visits on tourist intentions to return. Eur. J. Mark. 2009, 43, 670–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakoori, A.; Hosseini, M. An examination of the effects of motivation on visitors’ loyalty: Case study of the Golestan Palace, Tehran. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 2019, 32, 100554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adam, I.; Adongo, C.A.; Amuquandoh, F.E. A structural decompositional analysis of eco-visitors’ motivations, satisfaction and post-purchase behaviour. J. Ecotourism 2019, 18, 60–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellanos-Verdugo, M.; Vega-Vázquez, M.; Oviedo-García M, Á.; Orgaz-Agüera, F. The relevance of psychological factors in the ecotourist experience satisfaction through ecotourist site perceived value. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 124, 226–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bimonte, S.; Punzo, L.F. Tourist development and host–guest interaction: An economic exchange theory. Ann. Tour. Res. 2016, 58, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.C.; Cater, C. Ecotourism as a Sustainable Recovery Tool after an Earthquake; CABI: Wallingford, UK, 2015; pp. 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mckercher, B. Academia and the evolution of ecotourism. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2010, 35, 15–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weaver, D.B.; Lawton, L.J. Twenty years on: The state of contemporary ecotourism research. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 1168–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirkby, C.A.; Giudice, R.; Day, B.; Turner, K.; Soares-Filho, B.S.; Oliveira-Rodrigues, H.; Yu, D.W. Closing the ecotourism-conservation loop in the Peruvian Amazon. Environ. Conserv. 2011, 38, 6–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olmsted, P.; Honey-Rosés, J.; Satterfield, T.; Chan, K.M. Leveraging support for conservation from ecotourists: Can relational values play a role? J. Sustain. Tour. 2020, 28, 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walter, P.G. Theorising visitor learning in ecotourism. J. Ecotourism 2013, 12, 15–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cinner, J.E.; Huchery, C.; MacNeil, M.A.; Graham, N.A.; McClanahan, T.R.; Maina, J.; Maire, E.; Kittinger, J.N.; Hicks, C.C.; Mora, C.; et al. Bright spots among the world’s coral reefs. Nature 2016, 535, 416–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strain, E.M.; Edgar, G.J.; Ceccarelli, D.; Stuart-Smith, R.D.; Hosack, G.R.; Thomson, R.J. A global assessment of the direct and indirect benefits of marine protected areas for coral reef conservation. Divers. Distrib. 2019, 25, 9–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MedPAN & UNEP-MAP-SPA/RAC. The 2016 Status of Marine Protected Areas in the Mediterranean: Main Findings. Brochure MedPAN & UN Environment/MAP—SPA/RAC. 2016. Available online: http://d2ouvy59p0dg6k.cloudfront.net/downloads/medpan_forum_mpa_2016___brochure_a4_en_web_1_.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Stevenson, S.L.; Woolley, S.N.; Barnett, J.; Dunstan, P. Testing the presence of marine protected areas against their ability to reduce pressures on biodiversity. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 622–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sala, E.; Giakoumi, S. No-take marine reserves are the most effective protected areas in the ocean. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2018, 75, 1166–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villasante, S.; Lopes, P.F.; Coll, M. The role of marine ecosystem services for human well-being: Disentangling synergies and trade-offs at multiple scales. Ecosyst. Serv. 2016, 17, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Hernández-Lara, A.B.; Carvache-Franco, O. Effects of motivations in marine protected areas: The case of Galápagos Islands. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0293480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yolal, M.; Rus, R.V.; Cosma, S.; Gursoy, D. A pilot study on spectators’ motivations and their socio-economic perceptions of a film festival. In Journal of Convention & Event Tourism; Routledge: London, UK, 2015; Volume 16, pp. 253–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crompton, J.L. Motivations for pleasure vacation. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 408–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Crompton, J.L.; Botha, C. Responding to competition: A strategy for sun/lost city, South Africa. Tour. Manag. 2000, 21, 33–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, G. Ecotourists’ motivation and revisit intention: A case study of restored ecological parks in South Korea. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 19, 1327–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, Y.; Zielinski, S.; Chang, J.S.; Kim, S.I. Comparing motivation-based and motivation-attitude-based segmentation of tourists visiting sensitive destinations. Sustainability 2018, 10, 3615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, A.S.; Cheng, I.N.; Cheung, L.T. Self-determined travel motivations and ecologically responsible attitudes of nature-based visitors to the Ramsar wetland in South China. Ann. Leis. Res. 2019, 22, 42–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Manner-Baldeon, F. Market Segmentation Based on Ecotourism Motivations in Marine Protected Areas and National Parks in the Galapagos Islands, Ecuador. J. Coast. Res. 2021, 37, 620–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chi NT, K.; Pham, H. The moderating role of eco-destination image in the travel motivations and ecotourism intention nexus. J. Tour. Futures 2024, 10, 317–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carrascosa-López, C.; Carvache-Franco, W. Market segmentation and consumer motivations in protected natural parks: A study from Spain. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tepavčević, J.; Miljanić, U.; Bradić, M.; Janićević, S. Impact of London residents’ sociodemographic characteristics on the motives for visiting national parks. J. Geogr. Inst. “Jovan Cvijic” SASA 2019, 69, 135–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jönsson, C.; Devonish, D. Does nationality, gender, and age affect travel motivation? A case of visitors to the Caribbean island of Barbados. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2008, 25, 398–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.S.; Kim, M.; Park, J.; Guo, Y. Cave tourism: Tourists’ characteristics, motivations to visit, and the segmentation of their behavior. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2008, 13, 299–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, J.M. The relationships between sociodemographic variables, travel motivations and subsequent choice of vacation. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Economics 2011, Business and Management, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 25–27 November 2011; Volume 22, pp. 37–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, G.; Bao, J.; Huang, S. Segmenting Chinese backpackers by travel motivations. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2014, 16, 355–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Deng, J. The New Environmental Paradigm and nature-based tourism motivation. J. Travel Res. 2008, 46, 392–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.S.; Feng, R. Temporal destination revisit intention: The effects of novelty seeking and satisfaction. Tour. Manag. 2007, 28, 580–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvache-Franco, M.; Carvache-Franco, O.; Víquez-Paniagua, A.G.; Carvache-Franco, W.; Perez-Orozco, A. Sociodemographic aspects and their relationship with motivations, satisfaction and loyalty in ecotourism: A study in Costa Rica. J. Cult. Herit. Manag. Sustain. Dev. 2022, 12, 209–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, C.P.; Machado, L.P. The length of stay in tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2010, 37, 692–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiotsou, R.; Vasioti, E. Using demographics and leisure activities to predict satisfaction with tourism services in Greece. J. Hosp. Leis. Mark. 2006, 14, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozdemir, B.; Aksu, A.; Ehtiyar, R.; Çizel, B.; Çizel, R.B.; İçigen, E.T. Relationships among tourist profile, satisfaction and destination loyalty: Examining empirical evidences in Antalya region of Turkey. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2012, 21, 506–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Environment. Puntilla De Santa Elena Fauna Production Reserve, Management Plan 2009–2013. 2009. Available online: https://www.ambiente.gob.ec/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2020/07/Acuerdo-Ministerial-Nro.-MAE-2020-006.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- Ministry of Tourism. El Mundial Infantil de Surf 2014 Será en Salinas-Ecuador. 2014. Available online: https://www.turismo.gob.ec/el-mundial-infantil-de-surf-2014-sera-en-salinas-ecuador/ (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- International Surfing Asociation (n.d.). 2009 ISA World Junior Surfing Championship in La FAE, Salinas, Ecuador. Available online: https://isawjsc.com/2014/es/salinas-ecuador/ (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Stothert, K.E.; Piperno, D.R.; Andres, T.C. Terminal Pleistocene/early Holocene human adaptation in coastal Ecuador: The Las Vegas evidence. Quat. Int. 2003, 109, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowe, S.M.; Duke, G.S. Buen Suceso: A New Multicomponent Valdivia Site in Santa Elena, Ecuador. Lat. Am. Antiquity. 2020, 31, 639–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.H.; Park, D.B. Relationships among perceived value, satisfaction, and loyalty: Community-based ecotourism in Korea. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2017, 34, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formica, S.; Uysal, M. Market segmentation of an international cultural-historical event in Italy. J. Travel Res. 1998, 36, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastenholz, E.; Davis, D.; Paul, G. Segmenting tourism in rural areas: The case of North and Central Portugal. J. Travel Res. 1999, 37, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johns, N.; Gyimóthy, S. Market segmentation and the prediction of tourist behavior: The case of Bornholm, Denmark. J. Travel Res. 2002, 40, 316–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).