Abstract

Ecological changes evoke many felt losses and types of grief. These affect sustainability efforts in profound ways. Scholarship on the topic is growing, but the relationship between general grief research and ecological grief has received surprisingly little attention. This interdisciplinary article applies theories of grief, loss, and bereavement to ecological grief. Special attention is given to research on “non-death loss” and other broad frameworks of grief. The dynamics related to both local and global ecological grief are discussed. The kinds of potential losses arising from ecological issues are clarified using the frameworks of tangible/intangible loss, ambiguous loss, nonfinite loss and shattered assumptions. Various possible types of ecological grief are illuminated by discussing the frameworks of chronic sorrow and anticipatory grief/mourning. Earlier scholarship on disenfranchised ecological grief is augmented by further distinctions of the various forms it may take. The difficulties in defining complicated or prolonged grief in an ecological context are discussed, and four types of “complicated ecological grief” are explored. On the basis of the findings, three special forms of ecological loss and grief are identified and discussed: transitional loss and grief, lifeworld loss and shattered dreams. The implications of the results for ecological grief scholarship, counselling and coping are briefly discussed. The results can be used by psychological and healthcare professionals and researchers but also by members of the public who wish to reflect on their eco-emotions. They also have implications for policy makers.

1. Introduction

1.1. General Introduction

In an era of ecological crises, various changes and losses evoke many kinds of sad feelings. Several terms have been proposed to describe the sad feelings that result from environmental crises, such as Kevorkian’s environmental grief [1], ecological grief (e.g., [2]) and solastalgia (e.g., [3]). Leading scholars Cunsolo and Ellis define ecological grief as “the grief felt in relation to experienced or anticipated ecological losses, including the loss of species, ecosystems and meaningful landscapes due to acute or chronic environmental change” ([2] p. 275).

What is felt as a loss is partly dependent on individual persons and their different value orientations and emotional attachments, which are shaped by many kinds of psychosocial and cultural factors, including political views and various worldviews [4,5]. Some changes related to ecological crises can be so vast and profound that they evoke feelings of loss in numerous members of a community, such as the loss of a very important hunting species due to climate change or the loss of possibilities for agriculture [6,7]. Other ecological changes evoke feelings of loss only in some people, and there may even be contradictory feelings among various people about an ecological change [8,9]. The distinction made in the research between loss and grief is an important one, since these two are not the same (e.g., [10]), and not all ecological losses engender sadness in all people (e.g., [11,12]).

Those who have especially close emotional ties with more-than-human environments have long observed ecological grief, well before there were special names for these feelings. Indigenous peoples have felt profound ecological grief over the centuries due to colonial destruction of their ecosystems and relations (e.g., [13,14]). Historical Western examples include the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins, written in the 1800s, in which, for example, the felling of trees is mourned (e.g., the poem “Binsey Poplars”, see [15]), and several writings by the early 20th century ecologist Aldo Leopold (e.g., [16], see the discussion in [17]). In the 1980s and 1990s, writers connected with the broad field of eco-psychology started naming various forms of ecological grief and developed practices to encounter the related feelings (e.g., Macy [18], and Glendinning [19] who includes a chapter on “Earthgrief”). Many ecological scientists and environmentalists felt profound ecological loss and grief, but this was rarely spoken about in public, and pioneering pleas were made by a few authors to start engaging with this grief (especially in [20,21] and more recently in [22]). Ecological grief is a major issue for sustainability professionals and advocates.

Research on the various forms and intensities of ecological grief gradually grew in during 2000s. Albrecht’s neologism solastalgia, created in the early 2000s, provided a special term for feelings of longing, homesickness and nostalgia caused by human-induced ecological changes such as open pit mining ([3], and more widely [23]). Solastalgia has been studied in various parts of the world, although with slightly different connotations [24]. The work of Cunsolo and colleagues on ecological grief, climate grief and mourning has been influential since the early 2010s (e.g., [2,12,25]), and case studies have been conducted, for example, among indigenous peoples [6,26,27]. Significant scholarship on ecological grief has also been conducted as part of what can be called eco-anxiety research: the study of anxiety, distress and worry caused by ecological issues (for reviews, see [28,29,30]). Broadly, ecological grief situates itself as part of a wider spectrum of ecology-related emotions and feelings, and it is especially intimately connected with sadness ([8,31,32], see already [33]). Scholars have continuously tried to develop measures for various kinds of these eco-emotions, including ecological grief and solastalgia (e.g., [34,35,36,37]).

The general scholarship on grief, bereavement and mourning has grown into a rather broad research field since the early 20th century. It has been closely connected with Death Studies, and, indeed, the field has been very much shaped by a focus on grief resulting from the death of a close human person [38]. Gradually, there have emerged frameworks that focus on a broader spectrum of possible losses and griefs, and tellingly these are nowadays often called “nondeath loss and grief” [39,40]. As a whole, this research field is fundamentally about the wide variety of sadness and loss, which has been argued to be an elemental part of human existence in a mortal world (e.g., [41,42], in popular press, [43]). However, much academic research on grief and bereavement has focused on clinically significant and “pathological” forms of the phenomena, and there have been long-standing debates about where the lines are between normal and abnormal grieving (e.g., [44,45]).

This general grief and bereavement research—later called “grief research” in this article—is a natural discussion partner for studies about ecological grief. However, there is surprisingly little literature about the in-depth relationship between these topics and research frameworks (e.g., [46]). Several pioneers in ecological grief research have made important observations and, sometimes, adaptations of general grief theory. Psychotherapist Randall [47] applied eminent grief scholar Worden’s theories to climate grief (see also many articles in [12]). Comtesse and colleagues [48] briefly discussed several grief theories and ecological grief, calling for more research on the topic (see also [49]).

This article answers this call by engaging more deeply with various theories of grief and bereavement in the context of ecological grief. Special attention is given to grief theories which also discuss non-death losses. The aim is to gain a greater understanding of the various forms of ecological loss and grief, with the help of general grief theory. At the same time, this endeavor helps to bridge these two fields of grief scholarship, bringing out similarities and differences. It is hoped that this will (a) encourage grief researchers to engage more with ecological grief with their expertise and (b) encourage people who are interested in ecological grief to read grief research and the many popular books about its key results. In general, this supports sustainability efforts by providing greater understanding of important dynamics related to them.

The author has a long history of engagement with grief research, and he has focused on ecological emotions for nearly a decade. He has worked mainly in the Western world, and a possible bias toward forms of ecological grief that are prevalent there is recognized.

As for terminology, this article uses “sadness” to refer to sad emotions and feelings and “grief” to refer to an emotional response to loss that is often long-lasting. In practice, the concepts of sadness and grief overlap. There is much discussion in research and philosophy about what exactly do the concepts of grieving and mourning mean and include (e.g., [50,51,52]). This article will not participate in those debates but instead uses these terms simply to refer to practical forms of engaging with grief and the related time spans. The concept of sorrow is used in the title to bring both loss and grief together (for other uses of sorrow as a term for ecological loss and grief, see [36,53,54]).

The rest of Section 1 (Introduction) is as follows. First, the forms of ecological grief and loss are discussed in light of earlier research. This section clarifies the viewpoint of this article in relation to particular and more global causes of ecological grief. After, a brief description of grief research, especially research on the various kinds of non-death loss, is provided.

1.2. Forms of Ecological Grief and Loss: Building from Earlier Research

Some cases of ecological grief are straightforward, such as when clearly manifested physical losses in ecosystems cause grief. The concept of solastalgia is sometimes used to study these kinds of losses, especially when one’s sense of home becomes eroded or lost in some way [24]. However, ecological grief can also result from more subtle changes, and some losses are immaterial, as will be discussed below. The relationship between ecological changes in the material world and feelings of ecological loss and grief can be complex.

There are three climate-related contexts in which ecological grief has been reported: “grief associated with physical ecological losses and attendant ways of life and culture”, “grief associated with disruptions to environmental knowledge systems and resulting feelings of loss of identity”, and “grief associated with anticipated future losses of place, land, species, and culture” (pp. 276–278). Cunsolo and Ellis point out that these three do not compose all of the possible types of loss that can generate ecological grief and that future research is needed (p. 276).

Already from these three categories, it becomes clear, however, that there are many kinds of felt losses that arise simultaneously from ecological and socioecological changes. When physical ecological losses take place, they can, at the same time, produce negative impacts on identity and ways of living. Furthermore, temporalities can be combined; for example, past and present ecological losses can intensify anticipatory loss and grief. Ecological grief scholar Saint-Amour wrote about this:

Rooted in losses that can begin in the deep past and extend into the deep future, it [ecological grief] exceeds the span of human seasons, lifetimes, epochs, and even species-being. And while the losses that prompt ecological grief can be actual losses in the present, these losses have a meaning beyond themselves: they are semaphores that point to planetary-scaled, often permanent losses in the future. ([55] p.139)

This brings out the close connection between ecological grief arising from particular ecological losses and possible grief and/or anxiety about the global ecological situation. The latter has been called by many names, with eco-anxiety and ecological distress being two of the most popular terms [30,56]. However, some refer to this global-level phenomenon using grief terminology, for example, “climate grief” (e.g., [57]). The author has argued, in previous research, that the process of encountering the ecological state of the world evokes a combination of what is called eco-anxiety and ecological grief [58]. There are various kinds of losses, changes and threats, and emotions related to anxiety and grief arise in order to help people react to them [28,59,60]. Because the ecological situation is so difficult, emotions easily become very difficult, too. Thus, the potential of such eco-anxiety and -grief that need psychosocial support increases, and these issues can become—or contribute to—mental health disturbances [61]. While this article focuses on ecological grief, the close connections with eco-anxiety are constantly kept in mind, and elements from grief research that may be helpful in understanding these connections were sought.

As regards the forms of ecological loss and grief, this article started from the understanding that there is ecological grief related to both particular losses and to the global situation. These two modalities are here called “local ecological grief” and “global ecological grief”. Interconnections between these two are evident but also complex. In some cases, local ecological grief dominates and global ecological grief may not play a major role (for a case example, see [62]). In other cases, both can overlap, or then global grief can dominate people’s experiences (for case examples, see [63]). In the contemporary world, many local and regional changes have connections with global phenomena and often people know this, which makes any complete separation of local from global difficult. A category of “regional ecological grief” could be conceptualized between these two (for a case example of that, see [64]).

Because of this complexity, this article respects the multifaceted nature of people’s experiences of ecological loss and grief. Instead of trying to neatly separate the local and global dimensions of ecological grief from each other, this article explores how general grief theory might help to discern various aspects of ecological loss and grief. Sometimes the focus will be more on local ecological grief and sometimes on global. Between these are regional ecological changes which are felt as losses.

1.3. Theories of Grief and Bereavement

In handbooks on grief and bereavement research [38,65,66,67,68,69], certain grief theories emerge as especially prominent. These include the task-based approach of Worden [68], the Dual-Process model of bereavement developed by Stroebe and Schut [70], the framework of “continuing bonds” [71] and the meaning reconstruction framework of Neimeyer and colleagues [72]. All of these theories have engaged critically with older “grief work” approaches, modifying and integrating various parts of it (for an overview of developments in grief and bereavement theory, see [73]). In brief, grief work approaches see grief as something that can be worked on, and classic views about it often emphasize the need to remove emotional attachments to the lost person and move on in life (e.g., [65], Chapter 1). However, scholars have observed that people often want to continue their emotional bonds with those who have been lost, instead of breaking those bonds [74]. Space does not permit here a full introduction to all relevant grief theories, but many of them will be discussed later in this article in relation to ecological grief.

While grief scholars and philosophers have observed various kinds of loss and grief for a long time now (e.g., [42], Chapter 2), non-death loss has received growing attention only recently [39]. Earlier, Walter and McCoyd [75] developed a framework of “maturational loss”, with which they observe that developmental phases bring both losses and positive feelings. Harris [76] has written about “living losses”, which have an ongoing characteristic. Hooyman and Kramer [65] studied typical and nontypical losses in relation to stages of life, and these losses include a wide variety. Schultz and Harris [77] recorded various “uncommon losses”, many of which are nondeath related. Ratcliffe and Richardson [40] discuss philosophically the relationship between classic cases of bereavement and non-death losses.

The recent collection of articles Non-Death Loss and Grief [39] takes significant steps forward by bringing together scholars both from classic bereavement research and other grief studies. It is strange, however, that Walter and McCoyd’s work is not discussed. The insights and results from grief and bereavement theory are applied to various kinds of non-death losses, and contributors feature noted grief researchers (e.g., Pauline Boss and Robert A. Neimeyer). Chapters of that book are used often in this article. The book also features a chapter on environmental grief by Kevorkian [78], which includes, for example, a brief discussion of ecological grief and chronic sorrow, a topic which is given a more extensive discussion below. Grief researchers have not yet engaged much with ecological grief, but recently there are signs of growing interest in this (e.g., [79] p. 15).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sources

Sources were collected over the years and searched for in electronic databases. Supplement S1 provides more information on the libraries, databases and search keywords.

Theories of grief and loss were engaged with using handbooks, review articles, research articles and monographs. The selection was influenced by the author’s long-time engagement with theories of grief and features of many prominent theories.

The sources on ecological grief included studies and literature that used a variety of terms and methods, including the following:

- Studies that used the concept of ecological grief (e.g., [2,11,48,80]). These are easy to find in databases. They are mostly recent, and the research interest seems to be growing;

- Studies that used other formulations that include the word grief, such as “environmental grief” (e.g., [1]). Environmental grief is an older term than ecological grief, but it did not spark as much interest among scholars then. Some often-cited articles and essays use the word grief or loss combined with other words, such as Windle’s “Ecology of grief” [20] or Randall’s “Loss and climate change” [47].

- Studies that used other related affective terms, such as sadness or sorrow (e.g., [36,81]);

- Studies that employed the concept of solastalgia (e.g., [3,24,82]);

- Studies that included observations of ecological losses and related affects but did not highlight this as a keyword. This includes many sources from anthropology, ethnography and sociology (e.g., [62,83]);

- Studies and popular books on eco-emotions, often focusing on eco-anxiety but including reflections about ecological grief (e.g., [57,84,85,86,87], see the overviews of these books in Table 2 in [58]).

A complete literature review of such a wide topic was not possible. In the future, more systematic reviews of relevant literature should be made, and it is hoped that this article helps in preparing those reviews. A selection of important sources for both ecological grief and general grief research is displayed in Supplement S2. For further information about current and previous research, a very recent scoping review focuses on the role of socio-ecological factors for ecological grief and includes information about many sources from the period between 2018 and 2022 [88]. The author has striven for objectivity and a balanced view of various sources, but, naturally, selections were made and some important sources may have been missed. The language of the sources was limited to English (and some very few Finnish sources).

2.2. Method, Research Questions and Structure

The article uses a philosophical and interdisciplinary method. The main research questions of this perspective article are as follows. On the basis of the study of both (a) the general research on grief and bereavement and (b) interdisciplinary ecological grief studies:

- What frameworks and concepts of loss seem helpful for an increased understanding of ecological loss? (Section 3.1)

- What frameworks and concepts of grief seem helpful for an increased understanding of the various forms of ecological grief? (Section 3.2)

- In the light of the analysis, what kind of new frameworks and concepts about ecological loss and grief could be useful? (Section 4.1)

The rest of Section 4 brings together the results (Section 4.2) and discusses the implications for ecological grief scholarship (Section 4.3). Finally, Section 4.4. mentions many themes for further research and development, such as applying grief counseling literature to ecological grief.

3. Types of Ecological Loss and Forms of Ecological Grief

3.1. Types of Ecological Loss

After engaging with the literature, four frameworks of loss emerged as especially helpful for providing a greater understanding of ecological loss: tangible/intangible loss (Section 3.1.1), ambiguous loss (Section 3.1.2), nonfinite loss (Section 3.1.3) and shattered assumptions (Section 3.1.4). Many of these have not yet been explicitly discussed in relation to ecological loss and grief in earlier research.

It is noteworthy that different characterizations could be made, such as adding traumatic loss as a separate category. In the following four types, traumas may be present, and for example shattered assumptions are often linked with trauma (see Section 3.1.4 below).

3.1.1. Tangible and Intangible Loss

“When Ganga is no more,” she said, “we won’t have any identity”. ([62] p. 27)

As observed in Section 1 (Introduction), scholars of ecological grief have noted that there may be many kinds of immaterial losses that people feel amidst ecological changes. As a framework in grief theory, the distinction between tangible and intangible losses [89] can help map these various kinds of possible losses.

Tangible losses may be perceived with the senses, at least when people pay attention: for example, a creature or their limb is no longer there, or a landscape is so much damaged that the changes are evident. Intangible losses have sometimes been called invisible losses, exactly because they are so difficult or even impossible to notice with senses. They include “lack of physical signs or something obvious to the casual observer” ([89] p. 239). Intangible losses can often be more abstract and sometimes symbolic, and they can have an existential characteristic. Examples include the following:

- Loss or change in identity or sense of self;

- Loss of connection to others;

- Loss of social status;

- Loss of meaning, faith or hope [89].

These kinds of intangible losses can easily be discerned in accounts of ecological loss and grief, as will be discussed below.

Particular losses can contain both tangible and intangible aspects, and a single tangible loss can include many kinds of intangible losses for a person or a collective. Furthermore, there exists complex combinations of losses and gains. For example, selling one’s car in order to reduce climate emissions—a chosen loss—can result in both feelings of pride and feelings of loss. The tangible loss is the car, but possible intangible losses include less autonomy in terms of mobility and a changed status in the eyes of other car owners. To name another example, if a couple decides not to try to have a baby because of the ecological crisis, this can generate many intangible losses for them and their own parents, such as the loss of an identity of a parent or grandparent (see [47,90]).

Grief scholar Rando’s concept of secondary loss can be helpful in thinking about causalities of loss, even when these are sometimes complex. Rando distinguishes between primary loss and the resulting secondary losses, which can include in her terminology also symbolic losses ([91], see the discussion in [92]). For example, the loss of fish in a body of water is a tangible loss, which can generate for fishermen loss of identity, loss of social status and loss of meaning in life. It should be noted that also intangible losses can generate other, secondary intangible losses.

Tangible losses such as loss of place, loss of creatures and loss of living beings have been the main target of studies about ecological grief and solastalgia [2,7]. To the author’s knowledge, the framework of tangible and intangible loss has not been extensively applied to ecological grief. However, the importance of paying attention to intangible losses has been raised by Cunsolo and colleagues ([2] p. 278, [6] pp. 52–53), and many intangible losses have been observed (e.g., [80,93] p. 28). More broadly, Tschakert and colleagues [94,95] insightfully recorded the many possible kinds of intangible climate-related losses, as Table 1 shows.

Table 1.

Intangible losses related to climate change, according to Tschakert et al. [94,95].

Exploring the various tangible and intangible aspects of ecological loss can be argued as an important task so that people’s experiences can be better understood and responded to (for this point in general grief research, see [42,96]). Grief scholars point out that intangible loss is very often disenfranchised because it is not so obvious [89], and as such, the intangible aspects of ecological grief deserve special attention (similarly in [95]).

Grief research may help also in seeing new aspects of ecological loss and understanding links between these and general forms of loss. For example, Harris notes that “loss of familiarity” in the world is a common form of intangible loss, for example, for immigrants [89]. Broadly, loss of familiarity in the world has been observed in experiences of ecological grief: people may feel that the world is not the same anymore because of ecological damage and change, and feelings of isolation and grief may result (e.g., [97]). This issue is closely linked with solastalgia and local ecological grief. However, it may be linked also with global environmental change. In the contemporary polycrisis, it has been mentioned by some that the world seems to be unfamiliar now (for changes to the Earth, see [98]). This might be a form of ecological loss, which is typical for older people, while younger people are more prone to feel intangible losses related to loss of future plans, for example.

Pastoral psychologists and grief researchers Anderson and Mitchell [96] have made distinctions which can provide further conceptual help. They categorize the following kinds of loss:

- Material loss;

- Relationship loss;

- Intrapsychic loss;

- Functional loss;

- Role loss;

- Systematic loss [96].

Some of these types of loss are tangible—most notably material loss—and some of them are intangible, and there exist complex combinations of both aspects. Anderson and Mitchell, themselves, do not use explicitly the framework of tangible/intangible loss, which is a newer feature. Many of their concepts can bring light to ecological losses and complement the exploration of Tschakert and colleagues (see Table 1 above). The concept of role loss can help in seeing certain intangible losses arising out of ecological damage and change, as in the case of the lost role of parent or grandparent or the lost role of a hunter in an indigenous community [6]. The concept of relationship loss may help in observing both human relationships and cross-species relationships that suffer because of ecological damage and change (for a discussion of mourning nonhuman animals, see [11,99,100]). Systematic loss refers to losses that resonate with many areas of life, even to the whole organic system of how one’s life is organized. Examples are losing a job or losing the family of one’s childhood when one moves away for university study. This concept can easily be applied to ecological loss as well, where it points to the complex ripple effects and general systems-wide strength of ecological loss [101].

With “functional loss”, Anderson and Mitchell refer to bodily functions, muscular or neurological. However, the concept might perhaps be used more broadly and combined with role loss in many ways. For example, a small-scale farmer losing the possibility of functioning as a farmer due to climate change suffers role loss, identity loss, and also loss of a central function in life; “I have lost a sense of dignity as a man”, says such a farmer in Ghana in a recent study [80].

One of the most interesting of these categories for ecological loss is intrapsychic loss. Anderson and Mitchell describe it as follows: “Intrapsychic loss is the experience of losing an emotionally important image of oneself, losing the possibilities of ‘what might have been,’ abandonment of plans for a particular future, the dying of a dream” ([96] p. 40). These formulations help highlight significant possible aspects of intangible ecological loss, and the concept of intrapsychic loss complements the concept of intangible loss. The list provided by Tschakert and colleagues, as displayed in Table 1 above, could thus be extended by certain forms of intangible, partly intrapsychic losses, such as the loss of dreams about the future, which will be discussed more below.

Sometimes the major aspect of ecological loss is intangible, and sometimes it is a combination of both tangible and intangible aspects. Table 2 shows examples of simultaneous tangible and intangible aspects in ecological loss, using empirical studies as source materials. The studies themselves do not use the framework of tangible/intangible loss.

Table 2.

Examples of tangible and intangible losses from empirical research on ecological loss.

The framework of tangible and intangible losses, thus, helps to clarify various aspects of ecological loss. It can also be used to discern various intangible aspects which have so far been discussed implicitly: see, for instance, the fictional ecological grief example by Comtesse and colleagues, where a mountaineer “does not even know who he really is without the cherished environment and has a diminished sense of security and control” ([48] p. 3).

3.1.2. Ambiguous Loss

Leah experienced solastalgia for predictable New England winters; her embodied, beyond words grief became more salient as autumn turned to winter and the predictable, sustained cold temperatures from her childhood had changed due to climate warming. ([102] p. 6)

Ecological grief scholars Cunsolo and Ellis have observed that “ecological grief may also expose new understandings of ‘ambiguous loss’” ([2] p. 279), because ecological losses may be ongoing, unending and ambivalent (see also [6] p. 51) [102]. They briefly refer to grief scholar Boss’ pioneering work in relation to this concept and framework. The “ongoing” and “unending” aspects of ecological grief are better captured by the concepts of nonfinite loss (see Section 3.1.3 below) and transitional loss (see Section 4.1.1), but the many kinds of potential ambiguities in ecological losses can be explored by engaging more deeply with grief research on ambiguous loss.

Ambiguous loss refers to such felt losses where there is either uncertainty about the exact state of the loss or then something is partly lost and partly not. The term was coined by Boss in the 1970s, and she has written extensively on the topic. A classic example is mourning soldiers who are missing in action. Grief is often complicated by this kind of ambiguity, sometimes becoming “frozen grief” because closure is not reachable. Furthermore, grief arising from ambiguous loss often becomes disenfranchised by others (more about this in Section 3.2.1) because of the uncertainties about the loss and the difficulty of supporting people who grieve for extended periods [10,103,104,105].

Boss and colleagues have observed that there can be two ways of ambiguity in relation to absence and presence of human persons: physical and psychological. A person can be “physically absent but psychologically present”, as with soldiers missing in action; or a person may be “physically present but psychologically absent”, as with people who have severe dementia [104]. Ratcliffe ([52] p. 189) observes a unifying theme: in both cases, there are “competing possibilities” that complicate grieving.

The first aspect seems very common in ecological loss: something about the ecosystems is gone, at least for now, but there is the psychological presence of it [12]. The second aspect needs more adaptation for an ecological context, but it seems also possible. The key idea is that there are cases where something or someone is in one way present, though key aspects of its essence are gone. A person with severe dementia has lost something essential; a forest which has lost birdsong might be an example of an ecological loss of this kind [106]. The recent proposal by Cáceres and colleagues [37] for a solastalgia scale includes a related survey item: “The place I live in has lost its inherent characteristics”. Human geographer Maddrell [107] has proposed the term “absence–presence” to describe the complex dynamics of grief (see also [108]), and this term might also be useful for ecological loss studies (for general reflections on the role of absence in ecological grief, see [11]).

The concept of intangible loss can be helpful and highly relevant here, and sometimes the intangible aspects of ecological loss are the ambiguous ones. For example, a person who feels to have lost the role of a grandparent because their child has chosen voluntary childlessness due to the ecological crisis can feel ambiguous loss: is the role of a grandparent completely lost or will some of their children someday have a child?

Table 3 shows a few examples of the various kinds of ambiguous loss, both in general and in relation to ecological loss.

Table 3.

Types of ambiguous loss and examples of ecological loss.

More broadly, the general aspect of ambiguity is evidently a major feature in ecological loss, as Cunsolo and Ellis pointed out [2]. Many creatures, features, relations and things are currently partly lost and partly not, and there can be great uncertainty as to whether they are completely lost. Climate change increases many kinds of uncertainty and instability in ecosystems, producing many kinds of ambiguous losses. For example, in places where for many people winters and snow are important, climate change has produced ambiguous loss, “snow anxiety” and “winter grief”. One can never know if and when there will be snow during the forthcoming winter [102,109,110,111].

This element of uncertainty produces a major link between anxiety and grief in the context of ambiguous loss. Uncertainty breeds anxiety (for eco-anxiety and this, see [30]), and grieving ambiguous ecological losses can complicate eco-anxiety in a kind of vicious circle. This is why the practice-based and research-based recommendations of Boss for engaging with ambiguous loss seem very helpful for the joint landscape of both ecological grief and eco-anxiety, such as learning to live with ambiguity and resisting ideals of total mastery and closure [10] (see Section 4.4).

3.1.3. Nonfinite Loss

Ashlee Cunsolo Willox … has studied the impact of a changing climate on mental health Inuit communities in Labrador. Visible signs of climate change in the North from month to month or year to year make the repercussions inescapable for the people who live there, she says.

“People … talk about experiencing strong emotional reactions: sadness and anger and frustration,” she says. “It’s a grief without end. Every day it’s changing and there’s a sense of loss.” [112]

In the literature review, a framework in grief research was found that resonates strongly with the empirical evidence on ecological loss: nonfinite loss. It deals directly with the aforementioned dynamics of ongoing and unending losses, which have been noticed by several scholars (e.g., [2,8,21,55]).

The framework of nonfinite loss was developed originally by grief scholars Bruce and Schultz around the year 2000 (this history is discussed in [77,113]). It been used, for example, in studies on parents who mourn the disabilities that their children have and on the experiences of women with involuntary childlessness. Nonfinite loss can be generated by a single powerful event, but its defining feature is the ongoing presence of the loss. There is something that reminds the person of the loss, triggering difficult feelings [39,77].

Explicit applications of the framework of nonfinite loss to ecological grief are currently almost nonexistent (except in the Master’s Thesis by Gelderman [114]), possibly because nonfinite loss as a concept is not very widely known in societies, although the experience often seems to be familiar. The concept can help to give recognition to an important but often unspoken dimension of ecological loss. Furthermore, research around nonfinite loss can help to clarify the many important dynamics of ecological loss and grief.

The aspects of nonfinite loss, as identified in the general research, can easily be found in accounts of people who experience ecological loss, grief and distress. These aspects are next discussed in two sequences. First, the key characteristics of nonfinite loss are quoted, and then the more exact features are cited and linked with ecological loss. Here is how scholars define nonfinite loss:

- “The loss (and grief) is continuous and ongoing in some way. While the initial event may be time-limited, an element of the experience will stay with the individual(s) for the rest of life;

- An inability to meet normal expectations of everyday life due to physical, cognitive, social, emotional, or spiritual losses that continue to be manifest over time;

- The inclusion of intangible losses, such as the loss of one’s hopes or ideals related to what a person should have been, could have been, or might have been;

- Awareness of the need to continually accommodate, adapt, and adjust to an experience that derails expectations of what life was supposed to be like. The term living losses is sometimes used to refer to nonfinite losses because of the awareness that an individual will live with this loss or some aspect of it for an indefinite period of time, and most likely for the rest of that individual’s life” ([115], see also [77]).

These characteristics of nonfinite loss are perhaps the most descriptive for global ecological grief. While more particular ecological losses can also cause long-standing grief, global change and damage have a nonfinite characteristic on a human timescale. Naturally, these two can be combined, and if local ecological losses happen regularly, the experience of nonfinite loss is intensified.

The second characteristic, “an inability to meet normal expectations of everyday life”, is not a feature of all instances of ecological grief. On the basis of the current research, it seems that the majority of ecological grief is not this intense, but many people do suffer, at least, periods in which ecological grief and anxiety affect their daily functioning [36,116,117]. Perhaps clarifying the wording, for example, to an “inability to often/sometimes meet normal expectations” would be more fitting for the fluctuating character of nonfinite loss. This is also in line with the nonpathological character of chronic sorrow (see Section 3.2.2), which is a common response to nonfinite loss [77,104,118].

The “cardinal features” of nonfinite loss, which grief researchers have recorded, are next cited and linked with studies about ecological emotions in Table 4.

Table 4.

“Cardinal features” of nonfinite loss according to Harris [115] (p. 141) and Bruce and Schultz (2001) [113].

It has to be emphasized that there are numerous examples of discussions of these kinds of features in eco-emotion literature, even while the term nonfinite loss is not mentioned, and many sources on ecological grief include discussion of practically all of these features (e.g., [84,85,86]). Windle wrote, already in the 1990s, “Environmental losses are intermittent, chronic, cumulative, and without obvious beginnings and endings” ([20] p. 144). Thus, the framework of nonfinite loss seems very relevant indeed for ecological grief and anxiety (similarly [114]).

The first feature explicitly links loss and grief with anxiety, and the fourth feature focuses on feelings of helplessness and powerlessness, which have been found to be very common eco-emotions (e.g., [121]). The last feature mentions continuing despair and dread, originally added to the list by Jones and Beck via a study of death row inmates and their close ones [126], and these kinds of difficult feelings have often been discussed by ecological grief and anxiety scholars (e.g., [128], for a review, see [32]). Since mortality and fear of death have been explicitly discussed as being related to eco-anxiety and ecological grief by many scholars (e.g., [129,130,131]), there may be even deeper links between the dynamics explored by Jones and Beck and these eco-emotions.

The many social dimensions that are mentioned in the list of features are further discussed below, especially in relation to disenfranchised grief (Section 3.2.1).

Researchers of nonfinite loss often discuss intangible losses. These include the loss of dreams and hopes, as well as identity struggles (see Section 3.1.1 and Section 4.1.3). The changes are so profound that “The individual feels compelled to engage in a significant search for meaning” ([77] p. 240), which brings us to the next and final theme related to losses.

3.1.4. Shattered Assumptions

“When I’m thinking about careers as well, I’m thinking, ‘Oh, well I’m going to find a job, but then the world’s kind of coming to an end’. I feel like that sounds really dramatic, but it does feel like, ‘What’s all this for?’ (Izzy)” ([132] p. 480)

“when you realize how serious, how far-reaching and how fast we need to act in the climate crisis … That’s an experience that shakes your entire foundation, in every possible way. It changes your entire view on the world in every aspect.” (young Swedish climate activist, ([133] p. 27))

There is evidence for such ecological loss and grief that is so powerful that it threatens to shatter people’s fundamental beliefs about the world and themselves [132,134,135]. Grief research offers tools for understanding these kinds of dynamics, and especially relevant seem to be the frameworks of shattered assumptions and meaning reconstruction. These frameworks are also referred to by scholars of ambiguous loss and nonfinite loss [118].

Many factors always contribute to whether people experience losses so strongly that basic assumptions about life are either profoundly challenged or even shattered. This is the interplay among the event, the persons experiencing it, and various moderating factors [5]. Certain events and losses are so powerful that they easily generate challenges to the basic assumptions of all kinds of people, such as sudden violent losses or very large changes that affect whole communities. But any loss that includes strong damage to emotional bonds can challenge people’s meaning systems [52].

In grief theory, these kinds of losses and the resulting grief processes have been explored prominently in several frameworks. The work around trauma by Janoff-Bulman has been highly influential here. Her view, based on empirical research, is that traumas are generated exactly by shattered assumptions [136]. One closely related framework has been the study of “traumatic grief” (for an overview, see [137]) and more broadly the relationship between trauma and grief [138]. Another close framework is existential crisis, which is defined by leading scholars as involving turmoil about fundamental assumptions and beliefs (e.g., [139]). Some scholars approach the phenomenon by focusing on the concept of meaning and people’s crises about meaning and purpose (e.g., [140], historically [141]).

Among grief scholars, for example, Attig [142] has engaged deeply with existential themes and meaning issues and Parkes with assumptive worlds [69,143]. Over the last decades, grief dynamics related to people’s meaning systems have been very prominently studied by Neimeyer and colleagues. They utilize a constructivist framework of meaning reconstruction, pointing out that grief processes include a very substantial element of reworking one’s system of meanings (e.g., [72,144]). This is an integrative grief theory, which incorporates, for example, the framework of continuing bonds and Attig’s view of grief as a process of “relearning the world”. Narrative methods play an important role in meaning reconstruction: Neimeyer and colleagues argue that people need to process both the “event story” of the loss and the “back story” of how they relate to the loss. People are invited to build a narrative that continues into the future and incorporates the experiences around losses, effectively reconstructing their life paths (e.g., [145], see also the “meaning attribution” framework by Smid in [146]).

Testimonies and studies of ecological loss show that deep processes of meaning reconstruction among shattered assumptions can arise from both particular ecological losses and global ecological grief [132,134,135,147]. The following description of “the assumptive world and loss” by grief scholars Harris and Winokuer seems very fitting to many of these experiences:

Significant life-changing events can cause us to feel deeply vulnerable and unsafe, because the world that we once knew, the people that we relied on, and the images and perceptions of ourselves may prove to be no longer relevant in light of what we have experienced. Grief is both adaptive and necessary in order to rebuild the assumptive world after its destruction. ([66] p. 122)

In the ecological context, this kind of loss clearly has aspects of ambiguous loss, because the earlier world is partly lost and partly not, and there may be uncertainty about the extent of future loss (for case examples, see [57,84]). This is related also to anticipatory grief and mourning, which will be discussed in Section 3.2.3.

The need to relearn the world—echoing Attig—in ecological grief has been briefly discussed by some scholars [84,110], and the possible traumas included in deep processes of ecological loss and grief have been noted by many researchers (e.g., [19,148,149]). Human geographer Head has observed how ecological grief may include grieving the modern subject and major assumptions about the future [21]. However, as far as the author can tell, there are not yet explicit adaptations of the frameworks of shattered assumptions and meaning reconstruction to ecological grief, and it seems that these would be very helpful. Neimeyer and colleagues have also written much about grief counselling and meaning reconstruction in practice, and these insights could be explored in relation to coping with ecological loss and grief (see Section 4.4).

These kinds of processes are closely related to worldviews and people’s possible religiosity and spirituality, in other words their systems of meaning. Ecological loss can be a factor in engendering or strengthening a spiritual crisis or a spiritual struggle (for various kinds of spiritual crises, see [150]), which can be seen as a form of existential crisis [139]. Losses related to worldviews and religious traditions have been noted in the research on intangible losses caused by climate change (see Table 1), but loss related to meaning systems as such has not received yet much attention.

Worldviews and meaning systems shape people’s experiences and practices, and if they are in turmoil, there are ripple effects in numerous aspects of people’s lives, including identity, social roles, and a felt sense of order or safety in the world [150,151]. Such impacts of loss are seen in the writings of many religious persons who have been deeply struck by the severity of the ecological crisis, and many of these people tell of a profound process of reorganizing and reshaping their worldview and spirituality (e.g., [152,153,154]). People may even feel that they are “losing their religion”, to quote the famous pop song by REM; for some people, a major aspect of ecological loss and grief can be felt as loss in relation to meaning systems or spirituality or religion. This topic needs further research, including studies of whether ecological grief may result in “complicated spiritual grief” [155].

Table 5 shows key terms related to these deep forms of ecological loss.

Table 5.

Key concepts and frameworks related to shattered assumptions and meaning reconstruction.

3.2. Forms of Ecological Grief

After engaging with the literature, four frameworks of grief emerged as especially helpful for providing a greater understanding of ecological grief: disenfranchised grief (Section 3.2.1), chronic sorrow (Section 3.2.2), anticipatory grief and mourning (Section 3.2.3), and complicated grief (Section 3.2.4). Some of these have not yet been explicitly discussed in relation to ecological loss and grief in earlier research, and all of them are here paid deeper attention than before.

The relationship between various kinds of ecological loss and these forms of ecological grief is multifaceted, and will be discussed more in Section 4. Some forms of ecological grief are intimately tied with certain types of ecological loss, such as chronic sorrow with nonfinite loss, but others, such as disenfranchised grief, can manifest in relation to many types of ecological loss.

3.2.1. Disenfranchised Grief and Its Varieties

… my friend Liz loved a certain forest in New Hampshire. … She was a teenager when a fierce storm blew into that forest, wiping out a large swath of trees. Liz was heartbroken. She had lost a friend, a spiritual presence, a guide. The next time her high school English teacher assigned the class an essay, she wrote about her love and grief for the forest. The teacher read the essay aloud to the class—not to praise it but to scorn it. When he finished reading, he chastised Liz for her sentimentality and her misguided notion that it was possible to love a mere thing like a forest. She was twice bereaved: once by the damage to her beloved forest and once by disrespect for her grief. ([156] p. 19)

The concept of disenfranchised grief refers to various kinds of dynamics where grief is not “openly acknowledged”, “socially validated”, and/or “publicly mourned” ([157] p. 26). The background is that there are contextual norms in societies and communities about grief, “grieving rules” [158]. Grief philosopher Ratcliffe condenses the core of disenfranchised grief: “others fail to acknowledge or legitimate one’s grief, in ways that affect one’s access to processes that shape grief’s trajectory” ([52] p. 211). A key developer of this framework has been grief researcher Doka (e.g., [159,160]), and the framework is commonly featured in grief research. Doka, himself, has briefly discussed disenfranchised grief in relation to non-death loss [157], but most research on it has focused on classic bereavement.

Dynamics of disenfranchised grief have often been observed in ecological grief research both explicitly and implicitly. Many kinds of ecological grief have not been understood in various communities [2,12,78], and sometimes ecological grief has been deliberately silenced or ridiculed, as in the quote above. As a result, ecological mourners have often felt belittled and isolated (e.g., [97,161]). Grief research shows that social support is a key factor in engaging constructively with grief, and if that is missing or complicated, many problems can ensue for grief processes (e.g., [68]).

However, the more exact dynamics of disenfranchised grief have not been discussed in ecological grief research. A deeper engagement with grief research can help show the various factors and dynamics in disenfranchised ecological grief. More broadly, this research and topic raises the importance of paying attention to the social dynamics around grief and mourning and provides opportunities to link disenfranchised grief more deeply with existing ethical and political critiques of the dismissal of ecological grief, which are often inspired by feminist philosophy (such as [12,162]).

Doka makes several distinctions about the various possible dynamics of disenfranchised grief, including the following: “the relationship is not recognized”, “the loss is not acknowledged”, and/or “the griever is excluded” ([157] pp. 29–30). In addition, some circumstances of losses are prone to increase disenfranchised grief, for example, via social stigma, and various grieving styles may affect the responses of others, including disenfranchisement (p. 31). Grief scholar Corr [163,164] extended the list to grief reactions and expressions of them, ways of mourning and rituals, and outcomes of grief [165]. Sociologist Thompson [166] observes that non-death losses are especially prone to disenfranchisement.

When the aforementioned distinctions are applied to the literature on ecological grief, it becomes evident that all of these dynamics of disenfranchised grief can take place in relation to ecological grief. However, some forms of these have received more attention than others, and closer engagement with the distinctions can help to discern important dynamics.

In ecological grief scholarship, the second dynamic mentioned by Doka, “the loss is not recognized”, has often been discussed. Scholars have noted that various kinds of ecological loss, including many climate-change-related losses, have not been socially validated or they have been contested (e.g., [167,168]). The reasons for not recognizing ecological losses can be very diverse. Fundamentally, anthropocentric ideas are often in the background, and sometimes these have been combined with colonial, patriarchal and/or racist leanings [12,162]. There may also be economic factors at play: people may not want to recognize an ecological loss if that recognition would include admitting that current economic practices should be changed [169]. Furthermore, the general psychosocial difficulty of connecting with ecological grief impacts the situation [170,171,172,173].

The first dynamic mentioned by Doka, “lack of recognition of the relationship”, provokes further thinking on ecological grief. Doka writes that, if there are no “recognizable kin ties”, grief can become disenfranchised: for example, if there was a secret love relationship between the deceased and another person, that other person may not be given any recognition of their grief [157]. In the case of ecological grief, this dynamic leads again to issues of anthropocentrism and speciesism. As, for example, ecological grief scholar Braun [100] has noted, anthropocentric societies deny kinship between humans and many other parts of the natural world, which many indigenous peoples have recognized. Braun calls for a renewed understanding of the fundamental importance of interspecies relations and kinship and warns that ecological mourning may sometimes be simply adjusting to a changed environment, not including necessary ethical and relational transformations in human attitudes.

In both kinds of ecological grief—not recognizing the relationship or not recognizing the loss—there seem to be versions where part of the loss is recognized but not its actual depth. This often happens also with general forms of grief. It is noticed that something is lost, but no real recognition is offered and, thus, there is “an empathic failure”, as grief scholars write [174]. For example, when a companion animal such as a dog dies and a person feels strong grief, others may say things such as “You can always get a new dog” or “Don’t be so sad, it’s only a dog” (for related dynamics, see [99]). Or, if a person feels ecological grief about the clearcutting of an old forest, people may say, “But the forest will grow there again!” [175]. The idea that the loss could easily be replaced is often deeply insulting to mourners and may lead to disruptions in social relations and loneliness among mourners. The framework of intangible loss is highly relevant here: what are often totally disenfranchised are the intangible aspects of the loss.

By the formulation “the griever is excluded”, Doka means that sometimes “the characteristics of the bereaved in effect disenfranchise their grief”; the person “is not socially defined as capable of grief” ([157] p. 30). Examples mentioned are persons with dementia or disabilities, and very young children.

When applied to ecological grief, this reminds that sometimes people’s characteristics can be used as an excuse to exclude them from ecological grief. For example, many children and old people often mourn the destruction of nature areas in cities, including city trees, but they may be disenfranchised because of their age and social status [175,176]. However, Doka seems not to pay enough attention to power structures and active disenfranchisement here, which are raised by Corr [163,164], Attig [165] and Thompson [177]. Grievers are often excluded because their communities and groups are held in a subordinate position [163]. For example, grief experienced by indigenous peoples about ecological and cultural changes has often not been recognized by white people in power (e.g., [178]). Furthermore, there are also studies of white people who become “emotional outlaws” because of their ecological grief [97].

Attig [165] argues that disenfranchised grief is not only an empathic failure but also an ethical failure and often a political failure: communities and/or societies fail to give recognition both to the loss and to the rights of mourners.

Disenfranchising messages actively discount, dismiss, disapprove, discourage, invalidate, and delegitimate the experiences and efforts of grieving. And disenfranchising behaviors interfere with the exercise of the right to grieve by withholding permission, disallowing, constraining, hindering, and even prohibiting it. ([165] p. 198)

This dimension of disenfranchised grief is further elaborated by the sociologist Thompson [166,177] and philosopher Rinofner-Kreidl [179]. Thompson discusses social injustices related to grieving, including discrimination and oppression, which can manifest in the dynamics of disenfranchised grief. The losses and griefs experienced by some people are likely even more disenfranchised than for others, and long-standing injustice issues, such as racism, sexism, colonialism and ableism, are evident here. This could be linked with discussions in ecological grief research concerning philosopher Judith Butler’s ideas and her concept of what is deemed “grievable” ([50], see many articles in [12]), as well as the framework of “affective injustice” [180,181], which has been applied to ecological grief by van den Bosch [162].

Rinofner-Kreidl [179] argues that grief both affects social relations and is affected by them (similarly [52]). She points out that the existential difficulty of facing death and mortality easily strengthens a general disposition toward disenfranchising grief in Western and industrial societies: “there is a far more extensive latent readiness to disenfranchise grief, which takes effect in our society for the sake of warding off deep existential anxieties” ([179] p. 203, italics in original). In general, social aversion to grief and mourning in the West has been discussed by many scholars (e.g., [44,76]), and several authors have linked it with denial of death (for a classic discussion, see [182]). These kinds of dynamics have been discussed by several authors in relation to ecological grief and anxiety (e.g., [131,170,183]) but usually not in conversation with theories of disenfranchised grief.

As for Doka’s distinctions about the circumstances of the loss or ways of grieving as causes for disenfranchisement, more research is needed to study these in relation to ecological grief. Broadly, the circumstances of losses naturally affect grief responses and the social dynamics around them, but Doka and other grief researchers have focused on stigma-producing circumstances and anxiety-producing circumstances. Some classic examples of stigmatized loss are suicide and death because of substance overdose ([157] p. 31). In relation to ecological grief, a related but complex case would be a suicide where the dead person has left a note stating that the ecological crisis is a major reason for the suicide; these kinds of cases have already been reported (e.g., [184]). Mourning a close one who has committed a suicide, at least partly because of ecological despair is perhaps not explicitly ecological grief—it depends on how the term is used—but it is, at least, closely related to the broad topic of sorrow caused by the ecological crisis.

It is an open question whether ways of grieving and particular mourning practices around ecological grief could be more a cause for disenfranchisement than the unrecognition of the loss, relationship or griever. One can speculate, for example, about cases in which the ecological loss would be, at least, partly recognized, but a person’s very emotional grief reaction would be the cause for disenfranchising. The same uncertainty applies to outcomes of mourning: whether others may claim that a person’s outcome of ecological grief is, in some ways, wrong or inadequate in their minds, whether this outcome is depression or acceptance.

More broadly, it seems important to think about what kinds of ecological grief and mourning are socially supported in various societies and communities—and which are not. This issue is related to normativity of eco-emotions and climate emotions (e.g., [9,185]). Certain “affective displays” and “grieving rules” [157] of ecological grief can be supported and others disenfranchised.

People can also internalize societal grieving rules and, thus, self-initiate disenfranchised grief ([157] p. 28, [166] p. 20) or strengthen the disenfranchisement started by others. These kinds of dynamics are also discussed below in Section 3.2.4. in relation to “inhibited grief”. There can be a literal ecological, reciprocal and complex process of disenfranchising grief, where individuals and collectives both do their part. Grief philosopher Ratcliffe points out that people can simply have a lack of “interpretative resources” to make sense of their grief ([52] p. 135), and this seems very evident in relation to ecological grief which is a new topic for many people.

The literal ecological character of disenfranchised grief is actually discernable in the definition of empathic failure by grief scholars Neimeyer and Jordan, which is cited also by Doka: “the failure of one part of the system to understand the meaning and experience of another” ([157,174] p. 96). However, as discussed above, this definition needs more awareness of (a) intentional use of power and (b) collective dimensions.

Table 6 brings together various aspects of disenfranchised grief and, when possible, links them with studies of ecological grief. Many aspects need further study and are marked with “?”.

Table 6.

Various dynamics of disenfranchised grief.

3.2.2. Chronic Sorrow

Here is a well of grief we’re going to have to drop into over and over again for all our lives, no matter if we are eighty or eight: the wrecking power of climate change. ([156] p. 13)

Grief theory includes a framework that brings together many aspects that have been discussed above and which seems highly relevant for ecological grief, namely, chronic sorrow. The name can be misleading: it is to be noted that this is not the same as ‘chronic grief’, which will be discussed more in Section 3.2.4. The phenomenon, which is characterized by chronic sorrow, is ancient: a type of grief that persists for a long time but includes variations in strength. Indeed, scholars have linked the old Greek word parapono, having a heavy heart, with chronic sorrow. This is a grief that is difficult but not pathological, because it has a very real reason [66,104,186,187].

The concept of chronic sorrow was spearheaded in the 1960s by rehabilitation counselor and leader Simon Olshansky, and it became used in nursing professions. In the 2000s, the concept and framework were much developed by grief scholar Roos [186]. Chronic sorrow was first observed, in particular, in the parents of children with disabilities, but later the framework was applied to a wide variety of cases. Roos defines chronic sorrow as follows: “a normal yet profound, pervasive, continuing, and recurring set of grief responses resulting from a loss or absence of crucial aspects of oneself (self-loss) or another living person (other-loss) to whom there is a deep attachment” ([187] p. 194). A deep feature of chronic sorrow is “a painful discrepancy” between what was supposed to be and what has happened, e.g., the feelings of parents who realize that their child will not develop similar abilities as most other children.

As grief scholars have observed, there is significant overlap between theories of nonfinite loss, ambiguous loss and chronic sorrow [10,118]. There is, however, a difference: nonfinite loss and ambiguous loss focus on the type of loss, while chronic sorrow focuses on the type of grief. The theories complement each other, helping to show various kinds of losses and related grief dynamics. Chronic sorrow is a natural response to significant nonfinite loss, and often aspects of ambiguous loss and/or disenfranchised grief make it more difficult [10,118].

The term chronic may sound pathologizing, but actually, a major emphasis of the whole framework of chronic sorrow has been to oppose pathologizing. Practitioners and scholars have wanted to bring into the fore that when losses are ongoing and complex, it is natural to experience grief in long-standing and variable ways [66,186]. This fits ecological grief, especially with its global dimension, very well, and also gives a strong message about the fundamental nonpathological character of such ecological grief.

As noted above, a special feature of the chronic sorrow framework is that it prominently includes both self-related loss and other-related loss as potential causes of such grief. In “self-loss”, some aspect of the self is felt to be lost, and in “other-loss”, this happens to somebody other. These losses are often tangible, such as a disabling injury, but they can also be intangible or include both kinds of aspects. Involuntary childlessness is one example of such a loss that can produce chronic sorrow; again, the “painful discrepancy” between expectations (and hopes) and reality is very evident ([118,187], compare with [40]). Fundamentally, both the self and the world are at play in chronic sorrow, especially one’s experience of the self in the world ([186] esp. 54–59). The first realization of the loss, which results in chronic sorrow, can often be traumatic ([186] p. 65), and chronic sorrow prominently includes shattered assumptions and the need for meaning reconstruction (see Section 3.1.4; and [118]). Thus, there are natural elements of an existential crisis in the processes of chronic sorrow ([186], especially Chapter 6).

As is the case with its loss-related counterpart, nonfinite loss, the framework of chronic sorrow has not yet been extensively discussed in ecological loss and grief research. Kevorkian ([78] p. 222) briefly observes the fittingness of the concept for many dynamics of ecological grief, but to the author’s knowledge, this article is the first time that chronic sorrow has been discussed in more length in an ecological context.

Table 7 shows the characteristics that Roos links with chronic sorrow and the literature on ecological grief in connection with them, showing how the aspects of this framework resonate closely with it. These are discussed below.

Table 7.

Chronic sorrow and ecological grief.

As Table 7 shows, all of these characteristics of chronic sorrow can rather easily be found in the studies and literature on ecological grief. Chronic sorrow seems to serve as a helpful unifying grief framework, especially for experiences of global ecological grief, such as broad climate grief, and for such local ecological griefs that have a profound and lasting impact on people. It is usually nonpathological but difficult (characteristic A in Table 7, see also Section 3.2.4). It is often disenfranchised because it is so difficult (characteristic B, see Section 3.2.1). It can include many kinds of tangible and intangible losses, including shattered assumptions (characteristic C, see Section 3.2.1 and Section 3.1.4). It often has a traumatic beginning (characteristic D, see Section 3.1.4 and Section 3.2.4), and it is closely connected with nonfinite loss (characteristic E, see Section 3.1.3).

Environmental grief scholar Kevorkian observes three aspects of chronic sorrow. She writes: “the loss [producing ecological grief] is ongoing without a foreseeable end and there are constant reminders of what has been lost and the potential of what will be lost with time” ([78] p. 222). Thus, Kevorkian links chronic sorrow and its characteristics of (e) practically nonfinite loss and (f) constant reminders with ecological grief. She also discusses trauma and ecological grief, emphasizing the “insidious” and “slow” trauma that is possible amidst long-time ecological changes and losses. Kevorkian notes that there may not be a “single identifiable incident” of trauma behind ecological grief but rather a more compounded experience of various losses causing trauma (for further discussions of related dynamics, see [149,191]). This is an important observation, but it must be added that, in some cases, there can be single incidents that cause ecological trauma and grief, whether these are experiences of “natural” disasters or traumatic awakenings to the severity of the ecological crisis (see [188,192,193]).

The research on characteristics F–J of chronic sorrow seems to offer especially novel insights for ecological grief scholarship. While fluctuations in ecological grief have been observed by several scholars (e.g., [58,86]), chronic sorrow research offers nuanced concepts about various aspects of these kinds of phenomena.

Chronic sorrow scholars have observed that there is usually a first, more intense period of crisis and grief following the realization of a significant loss. They note that this can last for several years ([186] p. 84). This correlates with attempts of ecological grief and anxiety researchers in recording an initial, intense process and then a continued process with fluctuations [58,188].

“Constant reminders or triggers” ([186] pp. 84–85) are closely related to nonfinite loss, but they can also arise simply out of the experience of chronic sorrow. Many kinds of things, both inner and outer, can contribute to a triggering effect ([66] p. 126). Something in the outer world may remind a person of the loss and the grief; or something internal, such as a mood or a feeling, may lead to the triggering of the grief in a person. In many forms of ecological grief, the array of potential triggers is vast. For example, carbon emissions are interlinked with a nearly endless amount of things in contemporary societies, and a person sensitized to climate grief can be reminded of their grief simply by seeing a new construction site, because construction causes carbon emissions [194]. Grief scholar Harris writes about the “unavoidable reminders of the loss” ([118] p. 294), and this wording seems very suitable for experiences of ecological grief (e.g., [87,195]).

Chronic sorrow scholars also observe “predictable and unpredictable stress points” (characteristic H), sometimes discussing “critical stress points” ([186] pp. 80–81). These are closely related to characteristic G, “unavoidable, periodic resurgence of intensity”, and the feature of “temporary adaptation” in chronic sorrow ([118] p. 292).

In classic types of chronic sorrow, many stress points have been identified. For example, a parent of a seriously disabled child may feel greater stress and grief when other children of the same age reach a developmental milestone that the disabled child does not. These kinds of events are called “life markers” by Roos, and a person experiencing chronic sorrow may be left “marker bereft” ([186] pp. 83–84). To mention another example, a person suffering from involuntary childlessness may feel unusually bad during an annual Mother’s Day or Father’s Day. Stronger feelings of anxiety are one possible impact.

In ecological grief research, these concepts can provide tools for observing similar dynamics and linking them with broader grief research. Triggers and stress points have been passingly observed in ecological grief and anxiety research, but more attention is needed to explore them. Some already known stress points include the publication of new and alarming climate change reports and periods in life in which big decisions should be made but the ecological crisis complicates them (e.g., [57,84,87]). The concepts of “life markers” and being “marker bereft” apply, for example, to those ecological mourners who have decided not to try to have children and who see others celebrating children’s births and development stages.

The alternation between psychic numbness and being emotionally flooded in chronic sorrow ([66] p. 126, [186] p. 86) also seems to have its counterparts in people’s experiences of ecological grief and anxiety [84,119,170]. Chronic sorrow research could be validating for people who experience fluctuations in their ecological grief. Furthermore, it could help them to accept that, in response to significant and ongoing losses, it is normal to feel persistent sorrow.

3.2.3. Anticipatory Grief and Mourning

Leah wept about her children’s futures and the immensity of intensified suffering for all living beings. At times, the grief was in response to a present irretrievable loss and at other times, the mourning was about imagined future loss. ([102] p. 6)

Anticipatory grief and mourning have been much discussed in grief research ([196,197]; for a review of the research up to the mid-1990s, see [198]). The topic has also been prominent in ecological grief research, because many dire environmental changes are predicted for the future. Cunsolo and Ellis delineate “grief associated with anticipated future losses” as a category of their threefold classification ([2] p. 278). Many scholars of ecological grief discuss the topic and mention the term “anticipatory”, combined with ‘”grief” or “grieving” ([11], especially Chapter 2, [46], ([199] p. 172), ([200] p. 242), ([201] p. 197)), or with solastalgia [202]. However, ecological grief scholarship has not yet engaged extensively with general grief research on anticipatory grief and mourning, such as Rando’s work [91,197,203].

A major theme in general grief research on anticipatory grief and mourning has been its usefulness. Scholars have wondered: Is anticipatory grief/mourning helpful or harmful? Or which forms and in which circumstances? ([198] p. 1353). Many debates around anticipatory grief and mourning have roots in different understandings about what grief itself is. If grief is seen more in the vein of “grief work”, then there is the possibility of thinking that such work could be done in advance, with various consequences (as in [196]). But if grief is seen as a process (e.g., [52,143]), it is quite natural that such a process can start with the “forewarning of loss”, a term grief researchers sometimes use [198]. Especially in relation to ongoing losses, the temporalities of the present and future are intimately connected.

Rando, a major scholar of anticipatory grief and mourning, has consistently argued that the phenomenon should be seen in a wide way. In her view, anticipatory mourning is:

the phenomenon encompassing the processes of mourning, coping, interaction, planning, and psychosocial reorganization that are stimulated and begun in part in response to the awareness of the impending loss of a loved one and the recognition of associated losses in the past, present, and future ([197] p. 24)

Rando, thus, includes the complexity of temporalities in her definition, and sees grief and mourning strongly as a process. Later she added the task of “balancing conflicting demands” to this characterization [203]. Rando prefers the term anticipatory mourning, instead of grief, because of the breadth of the phenomenon (for a critical discussion, see [204,205]). Because various scholars use different terms and with different nuances, here the term “anticipatory grief/mourning” is used.

Worden ([68] pp. 204–208) also warns against simple interpretations related to anticipatory grief/mourning and their effects, because grief is so multidetermined. There is the positive possibility that experiencing a longer period of knowing about the loss can help people in tasks of grief by providing the possibility to work through the acceptance of the loss and the many emotions that can be connected with it.

A special theme in anticipatory grief/mourning is the possibility of cutting off emotional bonds before the actual loss has happened in an effort to lessen the potential pain [197,198]. This theme is closely linked to the whole debate about the Freudian concept of decathexis and the grief work hypothesis. The influential framework of continuing bonds is a response to this: contemporary grief researchers usually see the aim of grief as not to be the cutting of emotional bonds but instead the re-working and continuation of them [74] (see Section 1.3).

These discussions and distinctions in grief research can provide nuance for ecological grief scholarship. The idea of decathexis has been discussed both explicitly and implicitly in environmental research, but the framework of continuing bonds and the nuances of anticipatory grief/mourning have not received attention. A classic example of an implicit discussion related to decathexis is the discourse about “biophobia”, as defined by Sobel [206], in environmental education and psychology: the possibility that children and young people, in particular, start to avoid natural environments because they remind them of the emotional distress caused by the awareness of environmental crises. Scholars have wondered whether people may cut or try to cut emotional bonds with the more-than-human world in an effort to protect themselves from pain in the future (e.g., [207,208]).

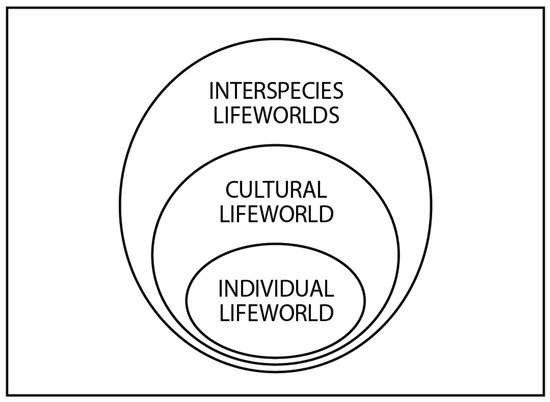

Several scholars of ecological grief have explicitly and critically discussed the concept and phenomenon of decathexis in relation to ecological grief and argued that, instead of it, the aim should be to continue relationships with the more-than-human world (e.g., [11,55]). These scholars also point out that various temporalities become intertwined in experiences of ecological grief. For example, Barnett writes: