Abstract

Indigenous foods are used to prepare delicious delicacies (Imefino) in South Africa, and are consumed for their medicinal, food security, and nutritional value. Many of them are rich in macro- and micronutrients and contribute to improving the households’ income. However, the commercialization of many indigenous foods remains problematic with poor market penetration. This study investigates the commercialization status and determinants of indigenous floral food (IFF) commercialization using descriptive statistics, and the double- and triple-hurdle analysis. A semi-structured questionnaire was used to collect cross-sectional data from 240 rural households in Amathole District Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. The result shows that most (60%) of the rural households rely solely on agriculture and agricultural-related activities as their source of employment. Ironically, among the rural household heads who are solely engaged in agriculture, most (83%) do not sell IFFs despite being involved solely in agriculture. More so, there is poor commercialization of IFF with the evidence of a low-commercialization index and low-income generation from IFF. However, IFF consumed for medicinal value has a higher commercialization index. Indigenous foods show potential for commercialization if well harnessed. The results also show that if the rural householder is a male and adds value to indigenous floral foods, he is more likely to make a decision that entails him being involved in the commercialization of indigenous floral foods. The result further proves that the influence of households’ willingness to pay for the improved seed of IFFs will not necessarily affect the intensity of IFF commercialization. Household size is among the determinants of IFF commercialization. Commercialization indicators reveal that rural household heads are committing to IFF commercialization. Based on the study’s overall findings, factors such as seasonality, price, demand fluctuation, and other identified challenges in this study affect IFF commercialization. Programs addressing value addition and the domestication of indigenous floral foods, application of marketing philosophy, and marketing mix, among others, are recommended.

1. Introduction

Commercialization is associated with the application of a business methodology to modernize new or existing services, to produce products or process lines for trade and profit maximization [1]. It borders around the spinoff of evolving trade, innovation, value addition, licensing, packaging, selling improvement, or in-house product launch to the market with the determination to increase income generation [2]. In general, commercialization is said to take place following a progressive transformation of small and emerging businesses in their operations to enable their participation in a larger market [3]. Commercialization aims to improve the value of a commodity, product standardization, and income generation [4]. However, the level of income generated, among other things, indicates the products’ commercialization status [5]. Every sector and aspect of society and livelihood could be commercialized [6].

Commercialization has overwhelming competitive advantages because it allows products to infiltrate urban and international markets timely [1]. It introduces new services and products to the market [7]. Commercialization leads to the creation and advancement of new job opportunities [8]. It does this by providing an avenue for recruiting and training necessary personnel throughout the logistic channel, from the beginning to the end of the production process [9]. Hence, it provides the needed platform and opportunity for the workforce, such as agents, distributors, operators, marketers, analysts, and other service providers, to strive. Commercialization brings solutions to market standardization and vacuums, such as lack of value addition and patent rights [10]. On the other hand, it stimulates business competition that promotes product development, cuts down monopolies, such as the dominance of a particular brand, and increases income [7]. However, achieving commercialization is engulfed by various challenges [11]. In most cases, many entrepreneurs need more than a simple framework for an appropriate commercialization strategy [4]. According to [12], many smallholders, rural householders, their products, and aspects of the agricultural sector are besieged severely by the challenges of a commercialization pathway despite their economic significance. This also applies to many indigenous foods in Africa, which need better global recognition that could only be made possible through commercialization [13].

Commercialization requires business experience, maneuvering of risk knowledge (risk adjustment), distribution, design, future forecasting, construction, marketing, customer support, and a pathway to production opportunity [2]. The campaign for the commercialization of many institutions and industrial sectors is on an upward trajectory [14]. However, commercialization applicability strategies of each sector vary in degree and scope despite procedural similarities that are linked to commercialization [15]. For example, the commercialization strategy applicable in the academic sector differs reasonably from that of the food sector, leading to skepticism about conflicting operation mechanisms and collegiate principles [15]. This also forms the basis for investigating specific sector commercialization determinants because their support differs [15]. Commercialization sometimes needs a patent agreement, but some organizations are unwilling to keep the research results secret [16]. This is a shift from the fundamental objective of some organizations, leading to a reduction/deviation in funding and purposes. For example, evidence from the United States in 1980 revealed that a weakening of research studies and research investment came about because it was transformed along organized objectives or individual business units [16]. In some cases, there is also the fear of irregularities in the demand and product price, which in turn has the potential to influence the quality of the product to be commercialized [17]. The private sector and significant numbers of entrepreneurs take advantage of commercialization to exploit the public by subverting the goodwill extended by the government for their benefit [17]. More so, it results in a high cost of product sales due to a profit maximization mindset. The profit orientation nature of commercialization largely neglects society’s welfare, especially that of people with low incomes, because it aims to provide solutions in return for pay [16]. This leads to the stimulation of the unequal distribution of wealth and products to the public [18]. On the other hand, innovation along the value chain of commercialization involving machine use has also been identified as one of the major causes leading to redundancy and retrenchment of staff. Further to this, it has been noted that the developing stages and segments of commercialization are time- and money-consuming, as special attention needs to be paid to professionalism.

Agricultural commercialization involves the transformation of a farming system and its product from that which uses crude implements to produce mainly for consumption to profit and market-driven-oriented farming [19]. The agricultural sector in South Africa is highly diverse, with well-developed commercial agriculture and poorly developed smallholder agriculture [20]. Agriculture in South Africa parades fewer large commercial farmers that have penetrated the export market, and it enjoys economies of scale [21]. Of course, the number of both large commercial and small subsistence farmers varies over time due to exit and entry [21]. However, ref. [20] reported that there are plus or minus 32,000 commercial farmers in South Africa. Nevertheless, ref. [21,22] reported that there are, on average, not more than 40,122 commercial farmers in South Africa. These commercial farmers produced no less than 80% of South African agricultural output [20,23].

Smallholder farmers in South Africa are estimated to average 2.6 million, and contribute only 5% to South African total agricultural output [23]. The insignificant contribution from the massive number of smallholders to agricultural output in South Africa, the dualistic nature of the agricultural sector, and the need to transform the rural area prompted the government to increase budgetary location and expenditure on smallholder agriculture for more than a decade [24]. Despite the efforts of the South African government, the challenge of commercializing many of the smallholders remains unabated [19]. The smallholders’ commercialization challenges are not peculiar to exotic crops but spill over to indigenous food plants [25]. One major challenge of indigenous foods (IFs) is that they are not widely consumed due to the perception of their low status as foods for the poor [26]. The lack of a methodology developmental guide also impedes the growth of indigenous foods in Africa despite their nutritional values [26,27].

1.1. Problem Statement

Research shows that the role of indigenous food is vital to some rural households’ livelihood; ironically, many rural households have not exploited the benefits of IFFs for maximum financial gain. For instance, many Xhosa householders in South Africa consume a delectable meal known as Imifino, which is prepared from some common IFFs like Ixhaba and Bomba, but these IFFs are frequently unsold despite their widespread consumption, and numerous health, nutritional, and food security advantages [28]. Research has described several IFFs as rich, abundant, and untapped food sources containing various minerals, vitamins, and antioxidants. However, only shreds of the numerous IFFs have witnessed commercialization, with evidence of poor market penetration [28,29]. Research shows that many individuals spend money on dietary supplements as sources of minerals, vitamins, and antioxidant food [30]. Ironically, the consumption of natural foods such as IFFs is not as widespread as the supplement intake, with regular and inappropriate intake of dietary supplements causing kidney damage [31]. Indigenous foods have income benefits if well harnessed for profit making and significant societal gain [32]. However, it is only a few rural households that generate income from IFs [27]. Furthermore, the revenue generated by vendors of indigenous foods is relatively dwindling due to the challenges of poor supply chains and the commercialization of indigenous foods [33]. This has, in the past, facilitated investments in developing indigenous foods, but only a few indigenous foods, such as Rooibos and Marula, have been commercialized in South Africa [32,34]. Most indigenous foods are not being sold despite the country having numerous IFFs [35]. Conversely, hundreds of rich and nutritious indigenous foods are yet to penetrate the market, preventing the optimum harnessing of their income generation benefit [36]. The extant literature shows that the consumption of indigenous foods is on the decline, especially among urban households [28]. This has resulted in research investigating the reason for the decline in indigenous food consumption, and the root cause for this was attributed to indigenous foods being viewed and portrayed as foods for the less privileged [37]. As such, there have been studies that demonstrate the nexus between IFs and food security and the frequency of IFs’ consumption [38]. Some areas of indigenous food development, such as domestication, adaptation, and resilience, have also been emphasized [39], and research also emphasizes strategies and the need to promote awareness of the significance of indigenous foods [40]. However, concerns have been raised in many areas of IFFs, including poor development, insufficient data to support the contribution of indigenous foods to food security, lack of support, and others [26]. One niche area in which IFFs have performed poorly is commercialization; ironically, research on the commercialization of IFFs remains elusive and not inclusive [41], with many IFFs serving the purpose of food consumption without being considered for commercialization [27,42]. In general, the commercialization of a product is greatly aided by research; ironically, many organizations and entrepreneurs have overlooked the importance of research in this regard. In Africa, there is a general challenge of bringing local content, including the commercialization of agricultural food and other food products, to global audiences [43]. Therefore, this study seeks to investigate, evaluate, and summarize general information on rural households’ IFF commercialization in the Amathole District Municipality in the Eastern Cape Province in South Africa. More so, this research is motivated because investigating the factors impeding the commercialization of indigenous floral foods would logically unlock the income component of rural households, generating multiple livelihood strategies, benefits, and optimization of the natural resources in their environment.

1.2. The Specific Objectives of the Study

The Specific Objectives of the Study are, as follows, to:

- Identify indigenous floral foods used by rural households from the study area.

- Itemize challenges faced by rural households in the commercialization of IFFs in the study area.

- Investigate IFF commercialization status and the determinants of IFF commercialization in the study area.

2. Materials and Methods

The study area is Amathole District Municipality of the Eastern Cape, South Africa. The name (Amathole) is derived from an isiXhosa language interpreted as forest, and it is located along the coastal area of the province [44]. Hence, it is a habitat for many faunas and floras indigenous to South Africa [45]. Ironically, it is among the poorest of municipalities in South Africa, with many rural areas [46].

2.1. Sampling Techniques and Data Collection Procedure

A cross-sectional research design and a multistage sampling technique were used to collect data from rural household heads across all six local municipalities in Amathole District Municipality. The multistage sampling technique was used to accommodate all local municipalities in Amathole. This is because Amathole has a vast land mass with several local municipalities that have significant amounts of forest areas as habitats for many faunas and floras [45]. The multistage sampling technique assisted in covering all the local municipalities in the large and geographically spread Amathole. Additionally, the study area (Amathole) was selected as it is one of the financially poorest district municipalities despite the availability of resources such as IFF. The first stage involved purposive sampling of the six local municipalities of Amathole. The local municipalities are Mnquma, Mbhashe, Amahlathi, Ngqushwa, Great Kei, and Raymond Mhlaba. The decision to select all six local municipalities was to ensure equal chances of data collection from household heads in the different local municipalities of Amathole. In the second stage, five villages/communities in each local municipality were randomly selected. The last stage involved random sampling of eight households from each municipality, sampling 240 residents from the study area using a semi-structured questionnaire. However, data from 211 respondents were used for the analysis because some questionnaires were completed incorrectly. The sampling procedure used, which covered random sampling, allowed for fair chances for all households in the areas participating in the study [47]. Hence, it prevented the likelihood of having a biased outcome [47]. Drawing inferential conclusions is one essential and preferred requirement in quantitative analysis, and achieving it requires the application of the right model, effect size, proper sampling technique, and procedure [48]. In this regard, Ref. [49] states that inferential unbiased conclusions are drawn on large populations, such as a sample size of 500 respondents. However, their findings also suggest an unbiased outcome for an inferential study of 100 respondents depending on the number of independent variables. Hence, Ref. [49] on event per variable (EPV) introduced a formula of 100 + xi that resulted in unbiased inferential outcomes with a small sample size of 100—where i is the number of independent variables, and x is an integer, which should start from eight. Therefore, the 211 respondents with the number of independent variables would present an unbiased result. Moreover, the multistage sampling procedure used involved random sampling and also took into account the possible occurrence of non-response by sampling nest household heads should the randomly targeted household fail to respond to give more credence to the sample size and validity of the result [50].

2.2. Theoretical Frameworks for Modelling Indigenous Food Commercialization from Market Participation

Regression models enable applying models such as ordinary least squares, Logit, Tobit, Heckman, and others to investigate the relationship between the outcome and the explanatory variables. However, applying each regression model depends on its appropriateness, competitiveness, and data to be analyzed [51]. For example, every rational human has the decision to participate in an event or not, but the decision needs an appropriate model for interpretation [52]. The agribusiness and the general agricultural sector are subject to complex environmental, institutional, and socioeconomic constraints that influence the stakeholders involved. Based on decision making, individual stakeholders such as the rural household head might not participate in an agribusiness-related activity, resulting in zero involvement. They might participate in it to stimulate a positive amount of involvement depending on the constraining factor influencing the decision.

If the rural household head’s decision is decoupled along a utilization of the amount, then the double hurdles application is appreciated because it involves a corner solution [53]. The corner solution explains the decision to be involved and the intensity of involvement in the activity, indicating the commercialization level, and this is associated with the limited dependent variables [54]. For instance, the quantity harvested/produced or income a household head generates for commercializing indigenous food will roughly continue over time in a positive interval depending on the household head’s decision. However, there will also be a pile-up of zero for the household heads who decide not to participate in the commercialization of the commodity, including IFFs [53].

The double-hurdle model presented by [55] builds on the Tobit model to better explain the choice decision of censor data for limited dependent variables with endpoints and a positive continuous interval variable that initially operates using probability attributes. However, Tobit’s model mainly used a particular figure to represent the entire observation without leaving room for adequate representation of each respondent [56]. Beyond the concept that the double-hurdle model nests the Tobit model, the double-hurdle model has the likelihood of being a more flexible alternative than Tobit and Heckman’s model because it suggests that factors that influence the willingness decision to commercialize IFFs could be dissimilar from the factors affecting the intensity or level of IFF commercialization [57]. Suppose the household head’s decision to commercialize IFFs is evident in the sales level/income generated, , from the ratio of the quantity of the commodity sold to quantities produced/harvested. The scenario is expressed in Equation (1), as mimicked in the presentation of the state double hurdle command [54].

Equation (1) is structural zero because some households will or will not participate in the IFF market by selling a specific quantity. A household that does not participate in the IFF market cannot commercialize IFFs. This indicates zero bound IFF commercialization, and there cannot be less than zero IFF sales if commercialization is to take place. However, following the Tobit model of a probability function, the decision by the rural household heads who are involved in IFF commercialization is based on the dichotomy variable. This decision could be mathematically linked with the standard normal density function expressed as φ and standard normal cumulative distribution function (CDF) described as Φ in the Tobit model as presented by [58] in Equation (2).

where represents the log-likelihood of the household probability decision to commercialize indigenous floral foods (IFFs). is the vector of likely factors responsible for the household head’s decision to commercialize IFFs, is the magnitude of the factor influencing the household decision, and is the specific density. Since Tobit functional forms restrict the stochastic process that links the parameter in the conditional probability for both commercialization the conditional density magnitude of the probability that commercialization is greater than zero , ranges between zero and one. Therefore, the Tobit model cannot manage the condition in which the covariate effect of the probability of a household commercializing IFFs is greater than zero where the amount (density) of commercialization is greater than one. The household head who commercialized IFFs might be less likely to generate zero income/sales but also generate income/sales beyond one amount, making the double hurdle more appropriate. The double-hurdle analysis is characterized by a relationship such that is the observed value of the dependent variable.

The household head’s decision to commercialize indigenous foods entails two steps. This implies that rural households must overcome two obstacles to effectively commercialize IFFs. These obstacles are the hurdle of commercialization and the hurdle of the intensity of commercialization. The first hurdle is a dichotomy choice in which the household head decides whether to commercialize IFFs by participating in the IFF sales or not, and it is referred to as a commercialization decision. The second hurdle is a truncated continuous decision, which involves the intensity of the IFF commercialization response due to their circumstances, which is called the quantity/density/level of commercialization decision. Since implies the amount of income/sales from IFFs by the household head, the model could be expressed as in Equations (3) and (4) [59].

Otherwise, with a minimum of zero commercialization of IFFs, then Equation (4) would apply

where is the random shock of the error term, and ui is a zero score that follows the distribution, while (0, Σ) stands for the independent and identical normal disturbance random error term with zero means, and σ is the unknown variance. The log-likelihood function for the double-hurdle model is formed by the integration of Equations (2)–(4) for the household head’s IFF commercialization decision, and the level of commercialization, which is presented in Equation (5), with Ψ for (x, y, ρ) standing for the CDF of a bivariate normal and a correlation ρ. Hence, following bivariate modelling that nested a truncated regression, commercialization of the household decision is presented in Equation (5) as modelled by [53].

The household’s IFF commercialization choice described above provides intuition about the structure of the double-hurdle model. Different researchers including [60,61,62,63] have used the double hurdle in the analysis of various agricultural commodities and other commercialization investigations. The hurdles models possess the unique attributes of mitigating sample selection bias, investigating unrestricted data (data not between 0 and 1), analyzing censored data, and intensity of commercialization.

Due to the likelihood that some rural household heads might not participate in the commercialization of IFFs with evidence of selling beyond zero sales and that all rural household heads who participated in the sales of IFFs might not sell a single/unifying IFF, the triple-hurdle model is also applied in this research. This is to further ensure a crystal-clear explanation of IFF commercialization conditions in the study area. It also aims to present a more acceptable outcome. The triple-hurdle model is also applied to compare its outcome with that of the double-hurdle model. Hence, the application of the triple-hurdle model becomes inevitable when a proportion of those who could participate in an event fail to do so despite being faced with similar opportunities or challenges, which could stimulate or prevent participation [64].

As applied by past research and in this study, the first stages (commercialization decision) of both the double and triple hurdles are dichotomies that use the Tobit model [65]. However, the double hurdle involves two stages, while the triple hurdle involves three stages. The triple hurdle gives the opportunity for all observations, such as the rural household heads, to be evaluated in terms of their (1) awareness or decision to harvest/produce or not, (2) choice to participate in the sales of harvested/produced commodity, and (3) intensity of involvement after the choice is made [66]. The exclusion of the zero participants limits the ability to make inferences about the entire population [64]. While the triple hurdle analyzed three stages in which both the first and second stages censor binary choices on truncation, the last stage, which involved the intensity of participation on continuity by nesting the two previous stages, could use probit, tobit, or logit because of their dummy variable nature [64,67]. The triple hurdle has been applied [64,66,68] to investigate the scenario that involved zero participation level.

2.3. Variable Description and Measurement

The dependent variable of the households’ IFFs participation decision for the hurdles analysis is the commercialization index of indigenous floral food sales in a month. It was measured from the baseline, starting from zero sales and ending with the average maximum sales in a month by individual sampled household heads. Ref. [4] described the major attributes that characterized commercialization as market specialization, the level of trade, and revenue/income generated.

Income earned from service has been used as a measure of commercialization level in different studies, and this comprises the amount of income generated [1,69]; financial sector [70]; income paid in the labor [71]; and the level of the business income [72,73]. However, a review of the literature on agricultural commercialization by households revealed that the measurement of commercialization is not restricted to a single or common standard [12]. For example, in the agricultural commodity output market, participation involving quantity has been used to measure commercialization. This is because there is variation in the degree of sales leading to commercialization, making the degree of commodity sales essential in agricultural commodity commercialization [74]. The impact of price variation could influence income generated from the commercialization of the products [75]. Hence, different commercialization indicators were used to assess the status of IFFs’ commercialization by the rural household heads in this study. However, the extent of IFF commercialization is assessed by the commercialization index (CI). It is assumed that commercialization intention and effort start from the sales of a commodity/service [76]. As a result, the commercialization index in this study is calculated from the baseline sales, which is zero (0), to the end-line (maximum) expressed as percentage sales of IFF by the rural household. Therefore, it is used as the dependent variable as measured and presented in Equation (6) to investigate the determinants of IFF commercialization by rural household heads.

where is the indigenous floral food commercialization index of the rural household. The gross values of IIF harvested/produced and sold were measured in number/head and kg. However, following the procedure used by [77], the commercialization index for six IFFs in the study was determined as presented in Equations (7)–(13), respectively.

The independent variables encompassing the household heads’ socioeconomic characteristics were measured. Other selected variable factors with the possibility to influence the commercialization of IFFs by rural household heads considered in this study included institutional (market types and value addition) and entrepreneurial factors (willingness to pay). While all determining factor variables can certainly not be included in a single investigation, the reason for including these variable factors was because the author is of the opinion that the socioeconomic characteristics of the rural household heads and institutional and entrepreneurial factors could play a crucial role in influencing IFF commercialization. These are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of other variables and measurement.

3. Results and Discussion

This section presents the results and discussion of rural household data collected on the commercialization of IFFs. It starts with the presentation of basic sample statistics of the respondents and the identification of IFFs in the study area. It proceeds to briefly discuss the common challenges associated with IFF commercialization in the study. Lastly, this section presents IFF commercialization status, IFF commercialization index, and the determinants of IFF commercialization in the study.

3.1. Basic Description of the Rural Households’ Involvement in IFF Sales

Table 2 presents the basic statistics of the rural households sampled and their involvement in IFF sales in the study area. The descriptive result of the rural households sampled shows that the majority (56%) have spouses as married couples. Among the married rural household heads, the majority (approximately 76%) are not involved in the sale of IFFs. Table 2 also shows that most (60%) of the rural households are not involved in occupations to generate income other than agricultural activities such as harvesting of IFFs. Ironically, among the household heads involved only in agricultural-related activities, most (approximately 83%) do not sell IFFs despite being involved solely in agriculture. Table 2 also indicates that male rural households are more (41%) involved in the sale of IFFs than their female counterparts (18%). This might be influenced by the male household head considering himself as the breadwinner/head of the home who needs to provide for the home. Hence, the male head will be willing to maximize income generation from available resources in their environment.

Table 2.

Summary of frequency statistics.

Table 2 further shows that there is not much variation in the age difference between the households that sell IFFs and those that do not sell. This could be due to the fact both young and older rural household heads could easily decide to harvest IFFs from the wild since they naturally grow in the environment in most cases. However, the mean value of respondents’ level of education attainment shows that households with lower levels of education are more likely to sell IFFs. In another development, households with more years of experience in farming, including the harvest of IFFs, are more likely to sell IFFs. This could be because they have gained knowledge of IFFs, including that of their market, over time.

3.2. Identification of Indigenous Floral Foods Used by Rural Households from the Study Area

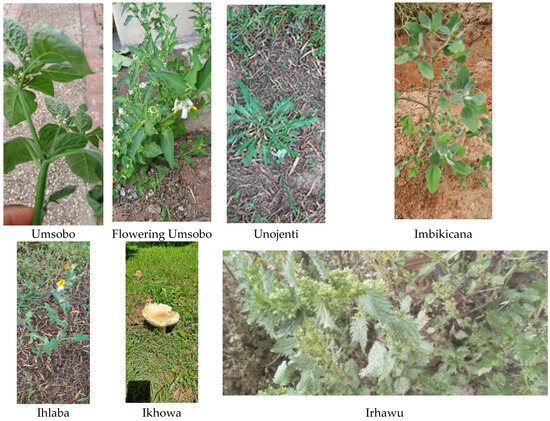

This section discusses the IFFs used in the study area through identification and description. Figure 1 presents a pictorial display of some common IFFs consumed in the study area.

Figure 1.

Pictorial description and identification of some consumed IFFs in the study area. Source: computed from field survey data, 2022.

Table 3 shows that IFFs are harvested/produced and sold for various values and uses in the study area. For example, the combined cuisine of Ihlaba and Unojenti described in Table 3 is popular and generally consumed as delicious meals called imifino. Ikhala is used for its medical value and sold to generate income.

Table 3.

Identification of IFFs in the Amathole District Municipality by usage.

In its totality, Table 3 reveals that the purposes for which IFFs are harvested include selling them for income generation, and consuming them for their food, nutritional, and medicinal value. However, Table 3 also reveals that there is a high likelihood that most IFFs are mainly harvested for food, nutritional, and medicinal value rather than income, with the indication of fewer reports of their income generation by the rural household heads.

3.3. IFF Commercialization Challenges Raised by Rural Household Heads

While there are different challenges to IFF commercialization: the sampled rural households in this study pointed out some of the challenges associated with the commercialization of IFFs as itemized:

- ➢

- Dwindling and lack of profitable market opportunity;

- ➢

- High levels of fluctuation in IFFs’ price and demand;

- ➢

- Low price of IFFs;

- ➢

- Increasing negative perceptions and responses of some people, especially young people, toward IFFs;

- ➢

- Lack of knowledge about the benefits and essential components of many IFFs;

- ➢

- Customers’ choice of going to harvest themselves;

- ➢

- Seasonality;

- ➢

- Limited government and organizational support in terms of how to promote and create awareness;

- ➢

- Lack of training on how to improve their IFFs. Rural households need more training in processing, value addition, management, and general product improvement;

- ➢

- Poor knowledge on the path of many people on the essential benefits of many IFFs;

- ➢

- The problem with standardization is that most IFFs sold are not calibrated for uniform weight before they are sold;

- ➢

- Inability to preserve the IFFs due to the nature of the market in which most of the respondents sell IFFs.

3.4. IFF Commercialization Status in the Study Area

This section uses key commercialization indicators to discuss the status of IFF commercialization in the study area. Recall that commercialization is the process of introducing a new product to the market. It includes stages such as production, distribution, marketing, sales level, income generation level, and customer support [3]. Hence, this section starts with the presentation of IFF status using key indicators and also presents some common commercialized IFFs in the study area and the proportion of rural households involved in the sale of IFFs.

3.5. Commercialization Indicators Using Types of Market and Value Addition in the Assessment of IFF Commercialization Status

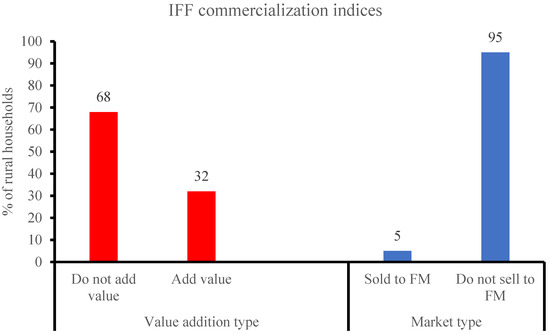

Figure 2 presents two indicators of commercialization (market type and value addition) to assess IFF commercialization status in the study area. In this regard, the status of IFF commercialization is analyzed based on the fraction of rural households that exploit commercialization indicators of selling IFFs to the formal market and adding value to their IFFs.

Figure 2.

Value addition and market types commercialization indices, where FM is a formal market. Source: computed from field survey data, 2022.

Figure 2 shows that only 5% of the rural sampled households sold IFFs to the formal market. On the other hand, a large proportion (95%) either sold to the informal market or did not participate in the IFF market. The results suggest there is a poor commercialization level of IFFs because the type of market where sales mostly occurred indicates the commercialization status of IFFs; ironically, many of them have not penetrated the formal market. These findings could be attributed to many rural household heads lacking market strategies and knowledge of IFFs to enable their sale in the formal market. The results are similar to findings in Botswana, which revealed that most indigenous food markets involve vendors selling them around the malls or in motor parks [33]. Figure 2 also indicates that the rural households’ engagement with IFFs is such that most of the respondents (68%) reported not adding value to their IFFs. While this study does not reveal the type of value addition, it shows that one key indicator of commercialization (value addition) is not optimized by many of the rural households for IFFs.

3.6. Income Indices of IFF Commercialization Level

Table 4 shows the level of income distribution generated from IFFs by rural household heads in the study area.

Table 4.

IFF income commercialization.

In Table 4, while some rural households generate zero income from the sales of IFFs, the mean income of R1326 (USD 70.46) is generated from IFF sales. The zero income generated by some of the rural household heads revealed by the result further indicates that some rural household heads are not commercializing nor intensifying the commercialization of IFFs. The study compared the monthly mean income from IFFs by rural household heads in the study area to the R2090 (USD 111.17) monthly grant paid to older adults aged 60 to 74 in South Africa. The average monthly income generated from IFFs by the households is R764 less than the older adults’ grant. This result indicates that while IFFs’ commercialization contributes to rural household income, the level of the IFFs’ income commercialization is shallow. However, the amount of income R14,600.00 (USD 775.77) generated in a month through the sale of IFFs by some rural households who sold IFFs in the study area indicates that IFFs could be significantly commercialized to promote substantial income generation among rural households.

3.7. Level of IFF Commercialization for Rural Households with Only Positive Sales of IFFs for Six Specific Selected IFFs

Table 5 presents the number of rural households involved in the commercialization of a specific IFF beyond zero sales (intensity of commercialization for selected IFFs) in the study area. More rural households (26 and 25%) are involved in the commercialization of Ikhowa (Mushroom) and Ikhala (Bitter Aloe). Again, this result shows that few are involved in the commercialization of IFFs. More so, it is necessary to investigate the commercialization index for specific IFFs because the likelihood of commercializing a crop could differ according to the type of crop. Additionally, the marketability of the crop, technological know-how, and the knowledge of the rural household head could drive the commercialization index of a specific crop. As revealed in Table 5, the average commercialization index of selected IFFs (Ikhowa, Ikhala, Impepho, Utywala bentaka, Irhawu, and Ihlaba) for the rural households who participated in their sale beyond zero were approximately 42, 79, 94, 84, 23, and 36% of the total production, respectively. This result shows there is a possibility for IFF commercialization in the study area.

Table 5.

Intensity of IFFs’ commercialization among rural household IFF sellers.

From the result in Table 5, IFFs with medicinal value or a high medicinal purpose of consumption seem to have a higher tendency for commercialization in the study area. For example, Utywala bentaka and Ikhala are among IFFs consumed for medicinal purposes, as indicated in Table 3, and they are among IFFs with higher 84 and 79% levels of the commercialization index, respectively. Impepho has the highest commercialization index of approximately 94% in the study area, and it is reportedly utilized for medicinal purposes. The result could be because a lot of people in South Africa still utilize herbs and other IFFs for healthy living. This result is in line with the findings of Street and Prinsloo (2013) [78], which revealed that 80% of South Africans consumed indigenous medicinal foods.

3.8. Commercialization Index of IFFs by Rural Household Heads in the Study Area

Table 6 presents the commercialization index of IFFs in the study area. To investigate the IFF commercialization index, the sampled rural household heads were categorized into groups according to the level of IFF sales. Table 6 shows that a high proportion (approximately 65%) of the rural household heads do not commercialize/sell IFF. Table 6 also shows that the mean commercialization level of IFF in the study area is only approximately 8%. This reveals that IFFs are poorly commercialized.

Table 6.

IFFs commercialization index.

Under the sales beyond zero to 25% of IFF, only 21% of the rural households commercialized IFF, with a mean commercialization index of 12.4%. On the other hand, only 14% of the rural household heads who sold beyond 25 to 100% of IFF output sales have a mean commercialization level of 37%. Table 6 results depict real-life situations where the proportion of farmers that sell commodities at large scales is fewer than those that sell at small scales. Furthermore, the result of the commercialization index in Table 6 implicitly implies that a high proportion of the rural household heads are not involved in the IFF’s commercialisations.

3.9. Determinants of IFF Commercialization by Rural Households Using Double Hurdle (DH)

This section briefly discusses the double-hurdle model fit. It also discusses the determinants of IFF commercialization and its intensity. Recall that the commercialization index (CI) of the IFF was measured as the value of the quantity sold to the quantity harvested/produced as a percentage for the dependent variable. Because the degree of sales leading to the commercialization could be attributed to different factors, the baseline sales (0) commercialization and end-line sales (maximum) level of IFFs commodities were used for the commercialization index in the double hurdles analysis. Hence, the first hurdle involved the rural household head deciding whether to harvest/produce IFF for sales or not. In this case, the rural household head either attempts the commercialization of an IFF by selling a specific quantity in any month of the year or does not sell. The second hurdle is the intensity/degree of IFFs’ commercialization, starting from the sales beyond zero. A small agribusiness has the ability to grow from the smallest/first degree of sales to the maximum (pick of commercialization) level [79]. Since some of the rural households do not attempt to commercialize IFFs, with evidence of zero sales, while some do, and because a small agribusiness could grow to increase the intensity of sales to the maximum commercialization level [79], the intensity of commercialization is truncated from greater than zero. More so, the intensity of IFF commercialization, which is contingent on the decision to commercialize, is a continuous variable that is truncated from greater than zero because a huge spike of rural households do not sell. This also means zero commercialization attempts despite the availability of IFFs in the rural area. Hence, the intensity of IFF commercialization (second hurdle) by the rural household is investigated from greater than zero to 100% sales.

Table 7 shows the model fit and determinants of IFF commercialization by rural households. The double-hurdle result of IFF commercialization shows that the log-likelihood value is =−383.9725, and 211 rural households were used for the analysis. The pseudo R2 value is 0.54, which shows that the model explains 54% variability in the outcome. Though the pseudo R2 is not precisely interpreted as linear regression R2, it has a nice interpretation in logit regression, as does the R2 in linear regression. The chi-square (chi2) result shows that, generally, the model is significant (chi2 = 0.000), indicating a good fit of the model. Following the explanation of the limited dependent variable by [80], this chi-square result shows that at least one of the predictors (determinants of IFF commercialization) in this analysis aligns with evidence of a good prediction of IFF commercialization in the study area. This reflects that the whole model predicts significant improvement in the determinants of the commercialization of IFFs by rural household heads over the null model.

Table 7.

Double-hurdle analysis of IFF commercialization determinants.

Before interpreting the determinants of the IFFs’ commercialization, this research points out one important fact justifying the application of the double-hurdle model in this study. The result of the model indicates that if the rural household head wants to effectively commercialize IFFs, the hurdle restricting the commercialization decision and the hurdle associated with the intensity/level of commercialization must be overcome. Hence, Table 7 shows that the factors influencing the rural household head’s decision to be involved in the commercialization of IFFs might not necessarily be the same as the factor(s) that affect the level (intensity) of commercialization. For example, the result shows that relative to females, male rural household heads might decide to be involved in the commercialization of IFFs; however, the gender of the rural households does not influence the intensity of IFF commercialization, indicating that the intensification of IFF commercialization by the rural male household head might only be significant if satisfactory income is generated. Hence, rural household heads must overcome some inherent attributes and behavioral responses for effective commercialization. Moreover, the findings explain and support the double-hurdle theory, as reported by [57], that factors that influence the willingness decision to commercialize could be different from the factors responsible for the intensity of commercialization. The double-hurdle analysis in Table 7, under the selection model of hurdle variables, shows that the IFF commercialization decision by the rural household head is significantly determined by gender, household size, value addition, and willingness to pay for improved IFF seeds.

3.10. Selection Model Aspect of the Double Hurdle

The selection model result in Table 7 shows that the gender of the rural household heads is significantly associated with IFF commercialization at a 99% significance level. Furthermore, the coefficient result for the gender variable shows that the male rural household head is, on average, 77% more likely to decide on IFF commercialization than the female. That means male-headed households living in rural areas are more likely to commercialize IFFs than female household heads. This result could be attributed to African common societies and cultural beliefs that the male gender should literarily take full or considerably more financial responsibility for the home. Hence, this drive could force rural male-headed households to optimize their decision on the utilization of available resources in their surroundings, including the commercialization of IFFs. More so, male household heads could take advantage of the available manpower to commercialize IFFs more than their female counterparts by engaging in more IFF activities as part of the agricultural sector, which is labor intensive. Ironically, these findings contrast with those of [81], that female-headed household heads commercialized more of their agricultural crops with evidence of higher income generation from a high sales volume than their male counterparts. However, the results of the study in terms of gender are closely related to the view of [82], who opined that being male promotes more commercialization in the agricultural sector.

There is an association between household size and the IFFs’ commercialization decision, with the household size of the rural household head positively influencing the IFFs’ commercialization decision at a 1% significance level. Furthermore, the result of the household size shows that as the household size of the rural household head increases by one, the likelihood of the rural household head engaging in IFFs’ commercialization increases by not less than 14%. The influence of the household size on IFFs’ commercialization decisions could be because a larger household size might stimulate more financial responsibility for the rural household head, which could result in the probability of the household head making the decision to involve the household members in the harvest of IFFs for commercialization as means of income generation. Similar findings of evidence that household size influences agricultural activity, including making market participation decisions, have been reported across African countries such as Kenya [83] and Nigeria [84].

Adding value to IFFs by the household head positively influences the rural household head’s decision to be involved in commercializing IFFs at a 1% significant level. Relative to rural household heads who did not add value to IFFs, the rural household heads who added value to IFFs will be more likely to commercialize IFFs by 1.36 units. The household head who has committed to adding value to IFFs might be more likely to engage in their commercialization compared to the household head who does not add value to IFFs.

As shown in Table 7, at a 95% confidence level, the rural households’ willingness to pay for improved IFF seed varieties has a positive relationship with the commercialization of IFFs. Hence, willingness to pay for improved IFF seeds increases the likelihood of IFF commercialization by 43%. The outcome means that if the household head lives in a rural area and is willing to pay for an improved variety of IFF seeds, then the household is more likely to commercialize IFFs than the household head whose willingness decision is not to pay for an enhanced variety of IFFs. The positive connection between the rural household heads’ willingness to pay for the improved seeds of IFFs and the IFF commercialization decision could be enforced by the household heads’ determination to maximize profit on return on investment. For example, the rural household head who purchases an improved seed variety would desire to have value for their money by having a better gross and net profit. This research implies that willingness, which indicates behavioral responses from rural households, plays a significant role in commercializing indigenous floral foods. This finding is similar to the study of [85], which opined that willingness to pay for innovation, including improved forage, is linked to higher production for the market, which results in commercialization in the agricultural sector. The influence of value added to IFFS commercialization shows how an individual’s ideology shapes behavior and stimulates decision-making mechanisms in the willingness to pay for improved IFFs by the rural household. Leveraging the serendipity of the Bayesian Mindsponge Analytical approach, this paper provides an in-depth analysis of how the inherent choice decisions of rural households play a core in the commercialization of IFFs through value-added-based activities that influence the choice decision of the rural household head. Considering the complexity and dynamic behavior of the entrepreneur as observed by [86], the influence of the value addition on IFF commercialization could unpack the question of how and why some rural households are willing to pay for improved IFFs to harness their commercialization, as pointed out in the Bayesian Mindsponge Analytical Approach. This result demonstrates that the rural household head could draw on the Bayesian Mindsponge Analytical Approach to make effective IFF commercialization decisions through (1) accessing reliable information on IFFs, (2) rejecting unhelpful information about IFFs, and (3) accessing different markets and populations of IFFs [87].

The result in Table 7 indicates that the factors influencing commercialization decisions will not necessarily affect the intensification of commercialization. Additionally, this result indicates that the entrepreneurial trail of willingness from the rural household head is crucial in influencing the commercialization decision. However, it shows that the rural householders’ willingness to pay for improved IFF seeds is associated with the IFF commercialization decision but does not influence the intensity of IFF commercialization.

3.11. Intensity Model Aspect of the Double Hurdle

The intensity aspect of the double-hurdle model explains the level of involvement of the individual who made the decision to participate in an invention, which includes the IFF commercialization decision [58]. The gender of the rural household head and value addition significantly influence the intensity of IFF commercialization by the rural household head.

Upon the decision of the rural household head to participate in the commercialization of IFF, the gender of the rural household head influences the intensity of IFF commercialization at a 10% significant level. Table 7 further indicates that in comparison to the female rural household heads, the male rural household head is approximately 59% more likely to intensify the commercialization of IFF. Again, this observed association is most likely caused by the male rural household head’s determination to harness and maximize available resources to meet the household’s financial needs as the head of the household. The gender result is similar to findings in Ghana, which stated that while female household heads are marginalized in the commercialization process of cultural foods due to culture, their male counterparts take advantage of their energy to intensify the commercialization of cultural food [88].

Table 7 shows that value addition to IFFs positively motivates the rural household head to intensify the commercialization of IFFs at a 1% significant level. If the rural household has overcome the IFF commercialization decision and added value to IFFs, such a household head is approximately 34.3 units more likely to increase the intensification of IFF commercialization than those who did not add value to IFFs. The nexus of IFF value addition invigorating IFF commercialization could be ascribed to the role the value added plays in making the IFFs more acceptable by a large proportion of society, resulting in an increased demand for the product, which could motivate intensification efforts. Similar research has reported that value addition, including traditional fermentation strategies of value addition, has triggered rural dwellers to seek entrepreneurial opportunities for rural households [89]. The findings align with research by [90] that value addition influences involvement in indigenous food activity, including the stimulation of income generation.

3.12. Determinants of IFF Commercialization by Rural Households Using Triple Hurdle (TH)

Table 8 presents the result of the triple-hurdle analysis. The second hurdle was incorporated into the first hurdle in the binary choice decision to investigate the triple hurdle application for the IFF commercialization in the study area. To determine the intensity of IFF commercialization in the triple hurdle, the IFF commercialization index was truncated at greater than 25% sales of IFF by the rural household head in a month. That is, conditional on the first and second hurdle decisions, the intensity of IFF commercialization is sales greater than 25 to 100% in a month by the rural household heads. The decision to use quarter sales of IFF as the cut-off is because the commercialization index shows that the mean sales of IFF by the rural household are low. More so, the decision to use quarter sales and not half sales of harvested/produced IFF in a month is to ensure that the investigation of IFF intensity of sales is robust and to ensure that a large share of rural household heads who overcame the first hurdle are not truncated from the analysis.

Table 8.

Triple-hurdle analysis of IFF commercialization determinants.

The selection result of the triple-hurdle analysis in Table 8 shows that the gender of the rural household head, value addition, and willingness of the rural household head to pay for improved IFF seed significantly influence the rural household heads’ decision to be involved in the commercialization of IFF. Further, this result and that of the double hurdles show that the gender of the rural household head, value addition, and willingness of the rural household head to pay for improved IFF seed stimulate the rural household heads’ decision to be involved in the commercialization of IFF.

The TH result in Table 8, like the double hurdle, shows that the gender of the rural household head has an association with IFFs’ commercialization decision. The TH gender result shows that rural household heads are, at a 5% significance level, more likely to make IFF commercialization decisions. The gender coefficient results of the TH further show that in comparison to females, male rural household heads are 51% more likely to be involved in the commercialization of IFFs.

The TH analysis in Table 8 also shows that the value added statistically influences the rural household heads’ IFFs’ commercialization decision at a 1% significant level. The TH coefficient result in Table 8 further reveals that IFFs’ value addition will increase the chances of the rural household overcoming the IFF commercialization hurdle by 97%. In other words, this result implies that unlike the rural household head who did not add value to IFFs, the rural household head who added value to IFFs is 97% more likely to decide to be involved in IFFs’ commercialization.

The TD result in Table 8 also reveals that the rural household head’s willingness to pay (WTP) has a positive relationship with IFFs’ commercialization decision at a 10% significance level. Hence, the coefficient outcome reveals that the rural household with an entrepreneurial trial, such as the willingness to pay for IFF improvements or training, is 41% more likely to get into the commercialization of IFF than the rural household head who is not willing to pay for such services.

The intensity of IFFs’ commercialization in the triple hurdle result shows that the rural household head’s marital status and level of education attainment significantly determined IFF commercialization. Contrary to expectation, a single-headed household head is more likely to intensify the commercialization of IFF in comparison to a married-headed household head. The triple hurdle intensity result in Table 8 also shows that living in a rural area and being married will reduce the intensification of IFF commercialization by approximately 7.15 units at a 10% level of significance. The result could be influenced by the fact that the married person could depend on his/her spouse for financial help, which could reduce the drive to intensify sales of IFF. The household head that does not have a spouse, unlike the married household head, would intensify the commercialization of IFF because of the desire to meet the household’s financial responsibility.

The triple hurdle result in Table 8 reveals that the level of education attainment of rural household heads statistically influenced the intensity of IFFs’ commercialization at a 10% significant level. Hence, Table 8 further indicates that an increase in the educational level of the rural household head at a 10% significant level increases the intensity of IFF commercialization by 1.42 units. This could be due to the fact that higher education attainment could increase agribusiness management skills, which could result in the intensification of IFF commercialization. This result corroborates the findings of [29], which observed that a higher level of education achievement stimulates the integration of rural households in selling IFF in the formal market. However, the T-value of the double and triple hurdles results, which are 2.87 and 2.73, respectively, show that adding value to IFF stimulates IFF commercialization more than any other IFF commercialization determinant.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, this study has demonstrated that the socioeconomic characteristics of the rural household heads and entrepreneurial factors are crucial determinants of IFF commercialization. This research revealed that married households are more likely to sell IFFs than single heads. This research posits that gender and household size influence the upscale of IFF commercialization. This study has indicated that both young and older rural household heads have equal chances of generating income from IFFs, and this has been carried out by the respondents in the study area, as there is no variation in the mean of the age differences between the households that sell IFFs and those that do not sell.

From the findings of the research, household heads with more years of experience in farming, including the harvest of IFFs, have the ability to and will be more likely to commercialize IFFs. IFFs contribute to rural households’ income, with some households, though few, generating income that could enable them to live above the poverty line. However, the research uncovered that most rural households do not add value to their IFFs, and the IFFs are mainly sold in the informal market, indicating poor commercialization of IFFs. Different indigenous floral foods are harvested and sold to generate income by rural households, but IFFs are harvested more for food and nutritional benefits than income benefits by the majority of the rural household heads. Hence, the IFFs’ commercialization indicators and commercialization index revealed that IFFs are poorly commercialized despite being available as natural resources due to different challenges. One core challenge pointed out by this research, militating against the rural household heads’ decision to commercialize IFFs, is the dwindling and lack of profitable market opportunities. The rural household head must overcome some inherent attributes and behavioral responses for effective IFF commercialization. Like the average entrepreneur, the rural household needs some entrepreneurial skills and drivers to demonstrate intrinsic qualities such as a willingness to invest in improved IFFs, and this willingness aids their commercialization of IFFs. This research concludes that common determining factors, such as the marital status of the rural household heads, value added, and willingness to pay, play a key role and affect IFFs’ commercialization decisions of the rural household heads in the double and triple hurdle investigations. From the result, it could be argued and concluded that the decision making of the rural household head plays a crucial role in the commercialization of IFFs. Hence, the application of the double and triple hurdles divulged that the socioeconomic characteristics and the entrepreneurial factors of rural household heads play a role in determining their involvement in IFF commercialization.

Recommendation

Based on the adaptability of IFFs to the environment and the willingness of rural households to pay for improved seed varieties of IFFs that are cultivatable, yield better, and are resistant to pest/disease outbreaks should be developed for their use. Hence, more aggressive domestication strategies and other programs that guarantee sustainability and off-season cultivation of IFFs should be adopted. Government, policymakers, and all stakeholders in the agricultural sector and rural area development agencies should focus on promoting and developing the IFFs’ value addition chain, as this will not only stimulate the commercialization of IFFs but also influence the decision making of the rural household heads to be involved in the income generation and commercialization of IFFs. Rural households should be trained in modern value addition, sorting, and packing strategies. This training could make rural household heads more efficient and less reliant on household members for labor. Moreover, to maximize the commercialization of IFFs, market-driven strategies such as value addition, promotion, packaging, branding, and the socio-characteristics of those involved in IFF agribusiness must be developed. Campaigns on the benefit of IFFs should be intensified, as this could reawaken the minds of many to the nutritional and medicinal benefits of IFFs. It could also change the negative narrative and perception of IFFs. Policies that incorporate IFFs into school children’s meals should be encouraged. This will enable the children to grow up knowing the nice taste of those IFFs. This would also increase market demand for IFFs. Policies and programs targeting IFFs should focus more on rural male-headed households since they are more likely to be engaged in IFFs than households headed by females. The fallacy of generalization that rural households are not committed to IFF commercialization should be prevented. Instead, they should be viewed as entrepreneurs with limited resources but willing to be transformed. This will be a vital tool for stakeholders to take pragmatic approaches to address IFF challenges for better commercialization. Government should adequately support the development of IFFs as they play a crucial role in rural household income generation welfare. There should also be an exhibition display promoting local dishes prepared from IFFs. Indigenous foods, as stated earlier, are an integral part of the people’s culture. IFFs have been used over the years to prepare several dishes, including cultural Imefino dishes in South Africa. Since culture influences interactions within a group of people and with others around the world, which has been revealed in Cultural Tower to shape behavior, feelings, and thinking, the consumption, supply, and commercialization of IFFs could be supported in the form of the value added and promotion that suggests showcasing of their culture to the global arena by stakeholders.

5. Limitations of the Study

While the study investigated the impact of value addition on the IFFs’ commercialization decisions by the rural household head, it did not analyze the types of value additions implemented by rural households. It also did not focus on the types of IFF value chain challenges the rural households face. The scope of the study does not cover gross margin analysis. Moreover, the study investigated the entrepreneurial orientation trail of rural households’ willingness to pay for improved IFF seed. However, the study did not investigate other critical entrepreneurial orientation trails, such as pro-activeness, risk-taking, and innovativeness.

- Key findings and originality of the research

- ❖

- It is an outstanding research that applied both the double and triple hurdles in the investigation of IFF commercialization; the findings show that value addition is critical to IFF commercialization. Value addition influences IFF commercialization more than other determinants.

- ❖

- Most rural households struggle to add value to IFFs despite the significance of IFF value addition to IFF commercialization.

- ❖

- Rural households exhibit positive displays toward the commercialization of IFF, with some of them expressing willingness toward the development of IFFs, which plays a crucial role in influencing the commercialization of IFFs by rural householders.

- ❖

- IFFs are mainly consumed or sold in informal markets.

Funding

This research was funded by the University of Fort Hare Govan Mbeki Research & Development Centre (GMRDC). The grant number is P740, and “The APC was funded by GMRDC”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Ethics Committee of the University of Fort Hare (protocol code ETHICS CLEARANCE REC-270710-028-RA Level 01, Project Number: ONO001-22 and 11 November 2022).

Informed Consent Statement

I willingly and voluntarily participated in the exercise. The investor(s) told me the exercise was purely for research and academic purposes.

Data Availability Statement

The data are under the policy of the University of Fort Hare data availability. They were shared among the appropriate authorities. The ethical certificate clearance is ETHICS CLEARANCE REC-270710-028-RA Level 01. Project Number: ONO001-22 (Project).

Acknowledgments

The researcher appreciates all the enumerators for their efforts in the data collection. My postdoctoral research fellowship hosts, Amon Taruvinga and Willie Tafadzwa Chinyamurindi are highly appreciated. Your contributions toward my development are immensely commendable.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Stoddard, S.L.; Danielsen, A.J. What Makes an Idea or Discovery Marketable—And Approaches to Maximize Success. Surgery 2008, 143, 161–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walwyn, D. Selecting the Most Appropriate Commercialisation Strategy Is Key to Extracting Maximum Value from Your R&D. Int. J. Technol. Transf. Commer. 2005, 4, 162–171. [Google Scholar]

- Kenton, W. Commercialization: Definition, Plus the Product Roll-Out Process. Investopedia 2020. Available online: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/c/commercialization.asp (accessed on 12 September 2024).

- Baycan, T.; Stough, R.R. Bridging Knowledge to Commercialization: The Good, the Bad, and the Challenging. Ann. Reg. Sci. 2013, 50, 367–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van-Asselt, J.; Useche, P. Agricultural Commercialization and Nutrition; Evidence from Smallholder Coffee Farmers. World Dev. 2022, 159, 106021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehghani, T. Technology Commercialization: From Generating Ideas to Creating Economic Value. Int. J. Librariansh. 2015, 4, 192–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stenard, B.S.; Thursby, M.C.; Fuller, A. Commercialization Strategies: Cooperation versus Competition. In Technological Innovation: Generating Economic Results; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Leeds, UK, 2016; Volume 26, pp. 289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Jeen-Su, L.; Darley, W.K.; Marion, D. Market Orientation, Innovation Commercialization Capability and Firm Performance Relationships: The Moderating Role of Supply Chain Influence. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2017, 32, 913–924. [Google Scholar]

- Tolfree, D.; Mehalso, R. The Path to Commercialization; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Boni, A.A. The Business of Commercialization and Innovation. J. Commer. Biotechnol. 2018, 24, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bugusu, B.; Lay-Ma, U.V.; Floros, J.D. Products and Their Commercialization. In Nanotechnology in the Agri-Food Sector: Implications for the Future; Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 149–170. [Google Scholar]

- Gebremedhin, B.; Jaleta, M. Commercialization of Smallholders: Is Market Participation Enough? In Proceedings of the 2010 AAAE Third Conference/AEASA 48th Conference, 19–23 September 2010, Cape Town, South Africa.

- Asogwa, I.S.; Okoye, J.J.; Oni, K. Promotion of Indigenous Food Preservation and Processing Knowledge and the Challenge of Food Security in Africa. J. Food Secur. 2017, 5, 75–87. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers, D.S.; Lambert, D.M.; Knemeyer, M.A. The Product Development and Commercialization Process. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2014, 15, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hearn, G.; Cunningham, S.; Ordonez, D. Commercialisation of Knowledge in Universities: The Case of the Creative Industries. Prometheus 2004, 22, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillies, M. Commercialisation and Globalisation. Humanit. Soc. Sci. Futures 2002, 71. Available online: https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/document?repid=rep1&type=pdf&doi=de43519f1f85acb78bb70aff5ae36ac0f704ef42#page=78 (accessed on 9 August 2024).

- Roy, P.; Kumar Sinha, N.; Tiwari, S.; Khare, A. A Review on Perovskite Solar Cells: Evolution of Architecture, Fabrication Techniques, Commercialization Issues and Status. Sol. Energy 2020, 198, 665–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varman, R.; Skålén, P.; Belk, R.W. Conflicts at the Bottom of the Pyramid: Profitability, Poverty Alleviation, and Neoliberal Governmentality. J. Public Policy Mark. 2012, 31, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwatayo, I.B.; Rachoene, M.A. Effect of Agricultural Commercialization on Food Security among Smallholder Farmers in Polokwane Municipality, Capricorn District of Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Agribus. Rural Dev. 2017, 43, 143–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Trade Administration (ITA) South Africa. Country Commercial Guide: Agricultural Sector; International Trade Administration U.S. Department of Commerce: Washington, DC, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Research on Socioeconomic Policy (RESEP) How Many Commercial Farms Are There Really in South Africa and Are Most of Them ‘Large’? Research on Socioeconomic Policy (RESEP). 2020. Available online: https://resep.sun.ac.za/how-many-commercial-farms-are-there-really-in-south-africa-and-are-most-of-them-large/sample-post/ (accessed on 7 July 2024).

- Statistics South Africa. Stats SA Releases Census of Commercial Agriculture 2017 Report; Statistics South Africa: Pretoria, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Aliber, M.; Hart, T. Should Subsistence Farming Be Supported as a Strategy to Address Rural Food Security. Agrekon 2009, 48, 434–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliber, M.; Hall, R. Support for Smallholder Farmers in South Africa: Challenges of Scale and Strategy. Dev. S. Afr. 2012, 29, 548–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Dannenberg, P. Opportunities and Challenges of Indigenous Food Plant Farmers in Integrating into Agri-Food Value Chains in Cape Town. Land 2022, 11, 2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onomu, A.R. Pitfalls and Potential Pathways to Commercialization of Indigenous Food Crops, Fruits, and Vegetables in Africa. Asian J. Agric. Rural. Dev. 2023, 13, 25–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onomu, A.R.; Taruvinga, A.; Chinyamurindi, W.T. Potential and Transformation of Indigenous Floral Foods in Africa: What Research Tells over the Past Two Decades (2000–2022). Adv. Agric. 2023; accepted. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njume, C.; Goduka, N.I.; George, G. Indigenous Leafy Vegetables (Imifino, Morogo, Muhuro) in South Africa: A Rich and Unexplored Source of Nutrients and Antioxidants. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 13, 1933–1942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Onomu, A.R.; Amon, T.; Chinyamurindi, T. The Determinants of Formal Market Access for Indigenous Floral Foods among Rural Households in the Amathole District Municipality of South Africa: A Crucial Investigation for Understanding the Economic and Nutritional Dynamics of Rural Communities. J. Soc. Sci. 2024, 23, 1–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman, H.R.; Marriott, B.P.; Williams, C.; Judelson, D.A.; Glickman, E.L.; Geiselman, P.J.; Dotson, L.; Mahoney, C.R. Patterns of Dietary Supplement Use among College Students. Clin. Nutr. 2015, 34, 976–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, A.C. Kidney Toxicity Related to Herbs and Dietary Supplements: Online Table of Case Reports. Part 3 of 5 Series. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2017, 107, 502–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakona, G.; Shackleton, C.M. Food Insecurity in South Africa: To What Extent Can Social Grants and Consumption of Wild Foods Eradicate Hunger? World Dev. Perspect. 2019, 13, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasimba, S.; Covic, N.; Motswagole, B.; Cockeran, M.; Claasen, N. Street Vending of Traditional and Indigenous Food and the Potential Contribution to Household Income, Food Security and Dietary Diversity: The Case of Gaborone, Botswana. Agroecol. Sustain. Food Syst. 2022, 46, 181–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rampedi, I.T.; Olivier, J. Traditional Beverages Derived from Wild Food Plant Species in the Vhembe District, Limpopo Province in South Africa. Ecol. Food Nutr. 2013, 52, 203–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabhaudhi, T.; Chimonyo, V.; Modi, A. Status of Underutilised Crops in South Africa: Opportunities for Developing Research Capacity. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aworh, C.O. Promoting Food Security and Enhancing Nigeria’s Small Farmers’ Income through Value-Added Processing of Lesser-Known and under-Utilized Indigenous Fruits and Vegetables. Food Res. Int. 2015, 76, 986–991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinola, R.; Pereira, L.M.; Mabhaudhi, T.; de Bruin, F.-M.; Rusch, L. A Review of Indigenous Food Crops in Africa and the Implications for More Sustainable and Healthy Food Systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nengovhela, R.; Taruvinga, A.; Mushunje, A. Determinants of Indigenous Fruits Consumption Frequency among Rural Households: Evidence from Mutale Local Municipality, South Africa. J. Adv. Agric. Technol. 2018, 5, 227–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tlhompho, G. African Indigenous Food Security Strategies and Climate Change Adaptation in South Africa. J. Hum. Ecol. 2014, 48, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekomer; Deaconu, A.; Mercille, G.; Batal, M. Promoting Traditional Foods for Human and Environmental Health: Lessons from Agroecology and Indigenous Communities in Ecuador. BMC Nutr. 2021, 7, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, H.; Afrad, S.I.; Ferdous, H. Product Commercialization and Income Generation at Different Agricultural Farms in Bogra District of Bangladesh. J. Agric. Econ. Dev. 2015, 5, 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Masekoameng, M.R.; Molotja, M.C. The Role of Indigenous Foods and Indigenous Knowledge Systems for Rural Households’ Food Security in Sekhukhune District, Limpopo Province, South Africa. J. Consum. Sci. 2019, 4, 34–48. [Google Scholar]

- Tembo, G.; Jayne, T.S. Increasing Returns to Marketing in Zambian Maize Markets. Zamb. Soc. Sci. J. 2010, 1, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Amathole District Municipality Amathole District Municipality: COASTAL MANAGEMENT PROGRAMME. Amathole District Municipality 2016. Available online: https://cer.org.za/wp-content/uploads/2009/12/Draft-Amathole-District-Municipality-CMP_Notice.pdf (accessed on 10 September 2024).

- Amathole Forestry Co DAFF PARLIAMENTARY PORTFOLIO COMMITTEE PRESENTATION: Implementation of the B-BBEE Forestry Sector Transformation Charter November 2017; Amathole Forestry Company (Pty) Ltd.: Stutterheim, South Africa, 2017.

- Eastern Cape Socio Economic Consultative Council (ECSECC). Amathole District Municipality Socio Economic Review and Outlook, 2017; Eastern Cape Socio Economic Consultative Council (ECSECC): Vincent, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]