Abstract

Social media has introduced influencers and influencer marketing (IM), which is becoming increasingly popular among marketers. The effectiveness of IM is significantly influenced by parasocial interactions (PSI) and parasocial relationships (PSR) that develop between followers and influencers. Historically, a variety of scales have been used to measure PSI and PSR, raising concerns about the comparability of research results. Given the recent growth of IM and the importance of PSI and PSR within it, we aimed to examine how these constructs are measured in IM. We conducted a literature review, analyzing 72 studies focused on the empirical measurement of PSI and PSR. We found a significant heterogeneity in the measurement of PSI and PSR, identifying 26 scales for PSI and 29 scales for PSR, with two scales being used for measuring both PSI and PSR. This high degree of variability among scales that are supposed to measure the same constructs raises questions about the comparability of the results. We identified a critical need for clearer conceptual and empirical differentiation between PSI and PSR, which should be reflected in the development of measurement instruments. It is essential to develop reliable and valid scales that account for these differences and distinctly measure PSI and PSR in IM.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

With the emergence of social media in the first decade of the 21st century, individuals who have become more recognizable, visible, and influential on these platforms have also appeared—we call them social media influencers. Dhanesh and Duthler [1] (p. 1) describe influencers as follows: “Social media influencers, a type of opinion leader, engage in self-presentation on social media, accomplished through the creation of their online images employing rich multimodal narration of their personal, everyday lives, and leverage these images to attract attention, and a large number of followers”.

Due to their public image [1], which they have created on social media, the content they publish [2,3], their expertise [3], interesting lifestyle [2], or similarity to their followers [4], they have become very intriguing to other social media users—the followers.

Influencers’ ability to attract and maintain the attention of thousands to millions of followers [5], who are also consumers, has drawn the attention of marketers, especially at a time when traditional forms of advertising are losing their effectiveness [6,7].

This has led to the development of a new form of marketing called influencer marketing. Influencer marketing is based on the collaboration between influencers and brands, where influencers include the promotion of products, services, or viewpoints in their content in exchange for payment. The goal is to gain a favorable attitude from followers towards the promoted product, service, or viewpoint [8,9,10].

Due to its effectiveness, more companies are adopting influencer marketing [8], contributing to the growth of the global influencer marketing market, which was valued at $9.7 billion in 2020 and is expected to reach $22.2 billion by 2025 [11].

Numerous studies agree that interaction and relationship between influencers and followers are among the most critical factors for the effectiveness of influencer marketing [1,12,13,14,15]. Previous research has explained this phenomenon using the concepts of PSI and PSR [16], which have been measured using specifically created scales.

Until 2016, the most established scale for measuring PSI was the PSI Scale [17], with 20 items, and its shorter version with 10 items was published two years later [18]. Despite its popularity, the scale has been heavily criticized for primarily measuring PSR instead of PSI, leading to confusion in the field due to the lack of distinction between the constructs. In response to these criticisms, several other scales have been developed over the years, including the Audience Persona Scale [19], the PSI-Process Scale [20], the Multiple PSR Scale [21], and the Experience of Parasocial Interaction—EPSI Scale [22], each operationalizing PSI and PSR differently.

Liebers and Schramm [23] note that the measurement of PSI and PSR from 1956 to 2016 was extremely diverse, with various scales being used, making it difficult to compare results. Past measurements of PSI and PSR have also faced significant criticism, as many scales were found to measure constructs other than PSI or PSR and often lacked construct validity [24].

Given that calls for more unified measurement of PSI and PSR, considering construct validation, have been made for almost a decade, we aim to investigate whether these initiatives have been implemented in recent studies, particularly those in the field of influencer marketing.

1.2. Research Purpose

Liebers and Schramm [23] highlight the extreme heterogeneity in methods used to measure PSI and PSR in the past, while Dibble, Hartman, and Rosaen [24] are critical of the scales used for measuring PSI and PSR. The PSI scale, which was the most frequently used scale from its inception until 2016 [23], lacks content validity, as it is inconsistent with the original definition of PSI provided by Horton and Wohl, as well as with subsequent updates [24]. Furthermore, it includes items that more accurately measure PSR rather than PSI [24].

Dibble, Hartmann, and Rosaen [24] also criticize other scales used later, arguing that they do not define the constructs they aim to measure with sufficient validity and precision and have not undergone adequate construct validation testing. They emphasize that PSI and PSR have undergone significant theoretical and conceptual refinements since their inception, but the measurement tools have not reflected these developments.

Given that studies highlighting the extreme diversity in PSI and PSR measurement [23] and pointing out conceptual and empirical confusion in measurement methods [24] were published before the rise of influencer marketing, we are interested in understanding how PSI and PSR are measured in influencer marketing. Considering the critical role of PSI and PSR in the effectiveness of influencer marketing, it is essential to understand how PSI and PSR are measured in this context, especially given the empirical and conceptual ambiguities that existed before the rise of influencer marketing.

Therefore, we aim to examine how the challenges regarding empirical differentiation are addressed in the measurement of PSI and PSR in influencer marketing.

The purpose of this study is to determine the following:

- Which scales are used to measure PSI and PSR in influencer marketing?

- Are there predominant scales for measuring PSI and PSR in influencer marketing?

- Do the measurement instruments for PSI and PSR in influencer marketing account for the distinction between PSI and PSR?

2. Theoretical Framework

2.1. Parasocial Interaction and Parasocial Relationship

The concepts of PSI and PSR were first mentioned in 1956 in an essay by sociologist Richard Wohl and anthropologist Donald Horton titled “Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction: Observations on Intimacy at a Distance”, published in the journal Psychiatry [16].

Horton and Wohl [16] defined PSI as a simulated form of conversational interaction that viewers experience while engaging with media characters, such as watching TV content featuring a television persona. It is a one-sided, mediated form of social interaction between the viewer and the media character [23]. The viewer perceives it as an illusion of a “face-to-face” interaction with the performer.

Viewers experience PSI as an intimate, reciprocal personal interaction, even though they are aware that it is merely an illusion [24]. Thus, PSI is similar to personal interaction between two individuals in real life, with the crucial difference being the lack of reciprocity and two-way communication—PSI is entirely one-sided.

PSI is triggered and managed by the media persona or TV character during their performance, specifically during the viewer’s exposure. This interaction begins with behaviors that indicate the character’s awareness of the audience, such as physical and verbal engagement, which create the illusion that the TV character is directly addressing the viewer. Experiments have demonstrated that this engagement includes actions like looking straight into the camera, mimicking real-life eye contact, turning towards the camera, and directly addressing the audience verbally [16,22,24,25,26]. The behavioral patterns and tactics used in real interpersonal interactions also contribute to the formation of PSI [20]. According to Horton and Wohl [16], physical and verbal engagement with the audience is crucial for establishing PSI.

In the article “Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction: Observations on Intimacy at a Distance” [16], Horton and Wohl also discussed PSRs, describing them as long-term, illusionary relationships and one-sided intimacy that viewers develop with media personas from a distance. While PSR begins with PSI, it persists even when the viewer is no longer directly exposed to the media character and extends beyond a single medium. The key aspect of PSR is its duration, which significantly outlasts the period of exposure. According to Horton and Wohl [16], PSR results from repeated exposure to the media character, whereas PSI involves mutual awareness that only lasts during the exposure to the media persona.

Both PSI and PSR involve illusory interactions or relationships experienced unilaterally by viewers or fans of media characters. Initially, the focus was on TV casters, but it later expanded to include media personas and now encompasses influencers. The crucial difference between PSI and PSR is the duration. PSI occurs only during moments when the person experiencing PSI is directly exposed to the media character, interacting with them. In contrast, PSR is a longer-lasting feeling that often begins with PSI but continues and is felt even when the viewer or person experiencing PSR is no longer directly exposed to the media character.

2.2. Measurement of Parasocial Interaction and Parasocial Relationship

PSI and PSR received little attention until 1985, being mentioned in fewer than ten scientific articles [23]. The topic gained significant momentum after 1985, when Rubin, Perse, and Powell [17] published the PSI Scale. This scale enabled the theoretical concepts to be translated into numerous quantitative studies, allowing for the measurement and examination of the effects of PSI and PSR. The scale, in its original and various adapted forms, became the standard for measuring the parasocial phenomenon in subsequent periods.

While the PSI Scale [17] revitalized the topic, it also introduced some confusion. The individual items in the scale did not distinguish between PSI and PSR [24]. Furthermore, the definition of PSI provided by Rubin, Perse, and Powell [17] in their article—described as the viewer’s interpersonal involvement with the media persona, including seeking guidance from media characters, viewing them as friends, imagining being part of their social world, and wanting to meet them in real life—did not distinguish between PSI and PSR. Rubin, Perse, and Powell [17], following the uses-and-gratifications theory, regarded PSI and PSR as forms of social involvement or gratification that users seek from media [24]. While Horton and Wohl [16] explicitly stated that PSI exists only at the time of the viewing experience, Rubin, Perse, and Powell [17] combined PSI and PSR into a broader concept of social involvement, encompassing interaction, identification, and long-term identification with television characters, contrary to Horton and Wohl’s original distinction.

The PSI Scale and its items convey feelings of long-term friendship, long-term affinity, or general positivity towards the character. Rather than focusing on the simulated conversational exchange or the one-sided sense of mutual awareness that occurs only during viewing, as described by Horton and Wohl [16], the PSI Scale measures these constructs differently [24]. Dibble, Hartmann, and Rosaen [24] conclude that the PSI Scale expresses more positive affection towards the media persona rather than the mutual awareness critical for PSI, making it more suitable for measuring long-term PSR. Tukachinsky [21] criticizes the PSI Scale for capturing PSR in only half of its items, with the remaining items measuring perceived realism, affinity, and identification.

As a result, after 1985, there was considerable ambiguity in precisely defining PSI and PSR. The term PSI was often used to describe what we now understand as PSR, and sometimes the terms were used interchangeably or as synonyms [20,23]. At the turn of the millennium and beyond, several researchers called for clearer definitions and distinctions between PSI and PSR [21,22,26,27]. These calls for distinction and more precise definitions led to a clearer differentiation between PSI and PSR, primarily focusing on the duration of each parasocial phenomenon. Consequently, new scales for measuring PSI and PSR were developed.

The Audience Persona Scale [19], with its 22 items, measured positive long-term involvement with a favorite media character. It consists of four subscales: Identification with Favorite Character, Interest in Favorite Character, Group Identification/Interaction, and Favorite Character’s Problem-Solving Ability. Schramm and Hartmann [20] evaluated the Audience Persona Scale as suitable for measuring PSR with a favorite character but unsuitable for measuring parasocial engagement with a disliked character and for PSI.

Schramm and Hartmann [20] were critical of previously published scales, asserting that they all measure PSR instead of PSI. Consequently, they developed the PSI-Process Scale [20], which measures PSI or users’ parasocial processing during exposure. The authors define PSI as parasocial processing, encompassing users’ cognitive, affective, and behavioral responses to media characters.

Tukachinsky’s [21] 24-item Multiple-PSR Scale defines PSR as para-friendship, imagined support and intimacy between the media persona and the viewer, and para-love, where the viewer perceives the media persona as physically attractive and desires the media character. Tukachinsky [21] notes that, similar to social relationships, PSR is not uniform and varies in both intensity and quality (friendship vs. love). Tukachinsky describes PSR as a complex, multi-dimensional phenomenon that cannot be entirely measured by the PSI Scale.

In response to the key shortcoming that the PSI Scale does not measure PSI as originally defined by Horton and Wohl [16], Hartmann and Goldhorn [22] created the Experience of Parasocial Interaction—EPSI Scale. This scale focuses on reciprocal awareness, attention, and adjustment with the media performer. Dibble, Hartmann, and Rosaen [24] claim this scale to be more suitable for measuring PSI than the PSI Scale.

The considerable number of different scales for measuring PSI and PSR, which have treated PSI and PSR differently both as conceptual constructs and empirically, has resulted in great diversity in measuring PSI and PSR over the 60-year period from 1956 to 2016 [23].

Liebers and Schramm [23] found that between 1956 and 2016, the parasocial phenomenon, which includes various parasocial concepts (e.g., PSI, PSR, parasocial break-ups, etc.), was measured in different ways. It was sometimes measured using one of the established scales, such as the short and long versions of the PSI Scale [17], the Audience-Persona Interaction Scale [19], and the PSI-Process Scale [20]. Others approached measurement by combining several different established scales, while some added items exclusively developed for their study to the established scales, and still others used individually developed scales unique to their study.

Liebers and Schramm [23] point out that the heterogeneity in the methods of measuring parasocial phenomena stems from the lack of differentiation between individual parasocial phenomena, making it difficult to compare different studies. They emphasize the need for standardized and more differentiated measurement instruments for parasocial phenomena, which would ensure the approximate comparability of empirical findings in parasocial research.

2.3. Parasocial Interaction and Parasocial Relationship in Influencer Marketing

Research examining PSI and PSR between influencers and followers on social media within influencer marketing consistently finds that parasocial phenomena have a crucial impact on the effectiveness of influencer marketing. This effectiveness is typically measured by purchase intention [28,29,30], brand trust [31], brand interest [32], and engagement with brand content [33].

Followers who developed higher PSI with a vlogger showed stronger purchase intentions for the product presented in the video [34]. PSI between French followers and fashion bloggers positively influenced purchase intentions for the products they showcased [4]. A study on a sample of Chinese individuals aged 18 to 40 also confirmed that PSI between them and the influencers they followed positively affected purchase intentions [35]. Followers who developed a more intense PSI with a beauty YouTuber expressed higher purchase intentions for the products featured in the videos, indicating that PSI directly influences purchase intentions [36]. Women who developed stronger PSI with a fashion vlogger also showed greater purchase intentions for the featured products [37,38]. Farivar, Wang, and Yuan [9] found that PSR had a stronger impact on purchase intentions than followers’ perception of the SMI as an opinion leader.

In their study, Reinikainen [31] found that PSR between a vlogger and her followers increased trust in the brand she represented. Similarly, PSR developed by followers towards a YouTuber positively influenced their opinions about the products he presented [39]. PSR between followers and influencers also positively affects followers’ interest in the brand being promoted [32]. A study among social media users who follow various influencers showed that PSR positively impacts all levels of engagement with brand content [40]. Likewise, followers who developed a stronger PSR with a fitness YouTuber exhibited a stronger and more enduring intention to perform the exercises and anticipated more positive physical effects from the workout compared to those who did not develop PSR with the influencer [41].

All these studies demonstrate that PSI and PSR play a very important role in influencer marketing.

3. Methodology

Selection of Studies

We conducted a systematic review using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) [42] of empirical studies that included the measurement of PSI and PSR in influencer marketing. We searched for articles in which the constructs PSI or PSR were among the variables in different models. These variables (PSI and PSR) were measured using various scales.

In the identification phase, we selected the Scopus database for our article search, as it is recognized as the largest multidisciplinary database of peer-reviewed scientific articles in the social sciences [43]. We accessed Scopus through the Digital Portal of the University of Primorska.

The literature review was carried out in December 2023 and included articles published up to 14 December 2023. We initiated the search using two keywords. The first keyword was “parasocial”. To encompass two forms of the parasocial phenomenon (relationship, interaction), we did not add any additional terms to this keyword, as doing so would have limited the search.

Since our study focuses on influencer marketing on social media, we chose “social media” as the second keyword. For the first 60 years, from 1956, when the term parasocial was first used [16], until 2016, researchers primarily focused on film and television [23]. The field of social media has become relevant only in recent years. Therefore, we limited our selection to studies examining the parasocial phenomenon on social media. The selected keywords were connected using the Boolean operator “AND”.

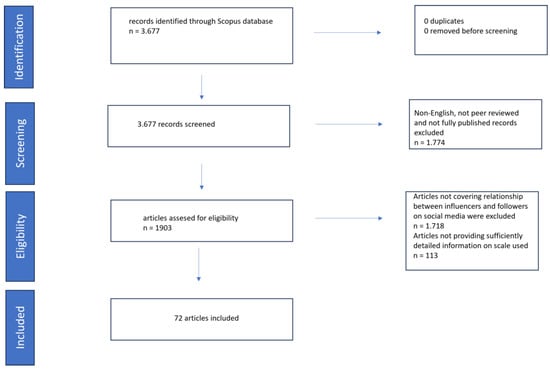

In the initial search and identification phase, we retrieved 3677 results. Since we focused exclusively on the Scopus database, there were no duplicates to remove during the identification phase. In the next step, the screening phase, we limited the results to fully published, peer-reviewed scientific articles in English, reducing our selection to 1903 articles ready for eligibility assessment.

In the eligibility assessment phase, we assessed the content relevance of the articles. We read the titles and abstracts to determine whether the articles covered the scope of our study: (1) the relationship between influencers and followers on social media and/or (2) the field of influencer marketing on social media. After this review, we excluded 1718 articles, leaving 185 for further review.

We then thoroughly read the remaining articles and included quantitative studies that empirically examined the parasocial phenomenon between followers and influencers on social media using one of the scales for measuring the parasocial phenomenon. We excluded any quantitative studies that measured PSI or PSR but did not provide sufficiently detailed information on the scales used. Specifically, we excluded studies that did not provide enough precise data to determine which items and how many were included in the PSI and/or PSR scales they used. At the end, 72 articles were included. The selection of articles is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The procedure of identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion within the systematic review (PRISMA).

We were left with 72 studies for a detailed analysis of scales used to measure the parasocial phenomenon. The list of all examined studies is provided in Appendix A, and the lists of all scales is in Appendix B.

After selecting studies suitable for examining the scales, we read each one in full and extracted the data of interest from each study. The data included the following:

- Authors

- Title of the article

- Journal

- Year of publication

- The parasocial phenomenon measured in the study (PSI or PSR)

- Questions in the scale

- Number of questions in the scale

- The predominant scales from which the questions were derived

- Whether the scale includes questions not derived from established scales

4. Results

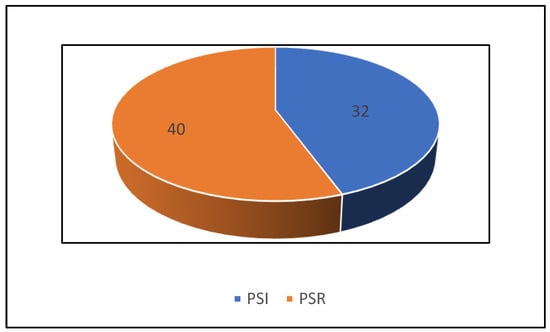

Out of the 72 studies examined, 32 focus on PSI, and 40 focus on PSR. See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Proportion of studies measuring PSI or PSR.

The first study included in our review (Scopus database) was conducted in 2015. From 2015 to 2019, three or fewer studies were conducted annually. However, the number of studies began to increase sharply thereafter, with the highest number of studies conducted in the most recent year. See Table 1.

Table 1.

Number of studies conducted per year.

In the 72 studies examined, 55 different versions of scales were used, varying in both the number of items and the content of the items. We defined scales as different if they differed in the number and content of items. If two scales contained the same number of items but differed in the content of only one item, we treated them as two different scales.

If items differed only in the subject’s reference, for example, “my favorite soap opera character makes me feel comfortable, as if I am with a friend” and “the YouTube blogger makes me feel comfortable, as if I am with friends”, we treated this as the same item. However, if the items also differed in meaning, for example, “I think the YouTube blogger is like an old friend”, we treated them as two different items and consequently as two different scales. Given that different items can indicate different operational definitions, we also classified scales that differ by only one item as distinct scales.

4.1. Parasocial Interaction Scales

In the 32 studies that measured PSI, we identified 26 different scales. The list of all scales and the studies in which they were used is provided in Appendix B.

The 26 examined PSI scales vary significantly in length, containing between two and 13 questions. The most common scales have five questions (four scales), followed by those with three, four, eight, or nine questions (three scales each). Only two scales contain two questions, and one scale contains 13 questions. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Number of questions in the PSI scales and the number of scales containing that many questions.

The 26 different scales were derived from various established scales (PSI Scale, Audience Persona Scale, PSI-Process Scale, Multiple PSR Scale, EPSI Scale) and included a wide range of items. The scales combined items from established scales and items specifically developed for the particular scale in different ways:

- Thirteen scales derived all their items from one of the established scales.

- Five scales combined items from an established scale with items specifically developed for the scale or taken from other less established scales.

- Five scales drew items from multiple established scales.

- Two scales combined items from multiple established scales and added items specifically developed for the scale or taken from other less established scales.

- One scale consisted solely of items not derived from any established scales.

Among all the scales:

- Twenty-three scales included items from the PSI Scale [17].

- Eight scales included items from the Audience-Persona Scale [19].

- Two scales derived items from the EPSI Scale [22].

- One scale derived items ns from the PSI-Process Scale [20].

- One scale consisted solely of items that were not part of any established scales.

- Eight studies used additional, specially developed questions for the study alongside one or more established scales.

4.2. Parasocial Relationship Scales

In the 40 studies that measured PSR, we identified 30 different scales. The list of all scales and the studies in which they were used is provided in Appendix B.

The PSR scales also varied significantly in length. The number of items ranged from three (one scale) to 22 items in one scale (one scale). A detailed breakdown of the number of items in the scales is presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Number of questions in the PSR scales and the number of scales containing that many questions.

In the 40 different scales measuring PSR, we identified items derived from established scales or specifically developed for the particular scale.

- Twelve scales derived all their items from one established scale.

- Twelve scales combined items from one established scale with additional items specifically developed for the particular study or derived from other less established scales.

- One scale derived items from multiple established scales.

- Three scales combined items from multiple established scales with additional questions specifically developed for the particular study or derived from other less established scales.

- One scale consisted of items that were not found in any previously established scales.

The scales used to measure PSR between influencers and followers on social media drew questions from the following established scales:

- Fourteen scales drew items entirely or partially from the PSI scale [17].

- Four scales drew items entirely or partially from the Audience Persona Scale [19].

- Two scales drew items entirely or partially from the Multiple-PSR Scale [21].

- One scale drew items from the PSI Process Scale [20].

- One scale consisted of items that did not appear in any of the established scales.

4.3. Similarities in Parasocial Interaction and Parasocial Relationship Scales

In measuring both PSI and PSR between influencers and followers in influencer marketing, we find that both phenomena are assessed using a large number of different scales. PSI is measured with 26 different scales, and PSR with 29 different scales, which vary in the number and origin of items.

We observe that the scales for measuring PSI and PSR draw from the same established scales: 23 PSI scales and 15 PSR scales draw from the PSI Scale [17], eight PSI scales and four PSR scales draw from the Audience-Persona Scale [19], and one scale for each PSI and PSR draws from the PSI Process Scale [20].

Upon detailed examination of all PSI and PSR scales, we found that two scales were identified as both PSI and PSR scales. In some studies, these scales were used to measure PSI, while in others, they were used in identical form to measure PSR. See Table 4.

Table 4.

Scales and their items used for measuring both PSI and PSR.

5. Discussion

The aim of this study was to review and examine the scales used to measure PSI and PSR between influencers and followers in influencer marketing and to answer the main research questions:

- Which scales are used to measure PSI and PSR in influencer marketing?

- Are there predominant scales for measuring PSI and PSR in influencer marketing?

- Do the measurement instruments for PSI and PSR in influencer marketing account for the distinction between PSI and PSR?

To achieve this, we reviewed the existing seminal literature on the measurement of PSI and PSR. We found that there has historically been considerable theoretical and empirical confusion in the conceptualization and measurement of PSI and PSR. Since their first mention, PSI and PSR have undergone several refinements and conceptual enhancements, as have the methods for measuring these constructs. Liebers notes that over 60 years of research, there has been significant heterogeneity in the ways PSI and PSR have been measured.

Despite Horton and Wohl [16] distinguishing between PSI and PSR, this distinction has become blurred, particularly after the publication of the PSI Scale, with the terms sometimes being used interchangeably. Rubin, Perse, and Powell [17] defined PSI as social involvement, which includes both interaction and long-term identification. The items included in their 20-item scale from 1985 and the shorter 10-item version from 1987 do not distinguish between the concepts of interaction and long-term relationship. Dibble, Hartmann, and Rosaen [24] emphasize that the scale primarily measures PSR rather than PSI.

At the beginning of the new millennium, several scholars began emphasizing the need to distinguish between PSI and PSR and developed new scales that incorporated recent theoretical advancements in these concepts. With the emergence of social media influencers and influencer marketing, PSI and PSR have become highly relevant concepts for describing interactions and relationships between influencers and followers. Research has shown that PSI and PSR between influencers and followers play a crucial role in the effectiveness of influencer marketing [34,35,37,38]. Therefore, we decided to examine the measurement instruments for PSI and PSR in influencer marketing.

We found that both PSI and PSR are measured using a considerable number of scales. In the 40 studies that examined PSR between influencers and followers on social media, 29 different scales were used. Researchers studying PSI in 32 studies used 26 different scales. For both PSI and PSR, the scales vary in content and length.

The shortest scales for measuring PSI have only two items, while the longest have 13 items. The shortest scales for measuring PSR have three items, while the longest have 22 items. The scales also differ in content, drawing from various established scales developed in the past. They may also include items from other less established scales or items specifically developed for the particular study.

The scales used to measure PSI draw their items from the PSI Scale [17], Audience-Persona Scale [19], EPSI Scale [22], PSI Process Scale [20], and several other less established scales, or they are entirely composed of items that do not belong to any established scale.

A similar practice is observed in the measurement of PSR. The scales for measuring PSR between influencers and followers on social media draw from the PSI Scale [17], Audience-Persona Scale [19], Multiple PSR Scale [21], PSI Process Scale [20], and various other less established scales. In this case, we also found one scale entirely composed of items that do not belong to any established scale.

The degree of differentiation among the 26 different scales for measuring PSI and the 29 different scales for measuring PSR varies. Some scales are very similar and differ by only one item. For example, the PSI 26 and PSI 15 scales differ by just one item. Similarly, the PSR 4 and PSR 15 scales both contain six identical items, with PSR 4 having an additional two items, all derived from the PSI Scale.

On the other hand, scales can be entirely different, such as PSI 1 and PSI 5, which differ both in length and content. PSI 1 has five items, while PSI 5 has 13 items, with no overlapping items between the two scales. A similar situation is observed in PSR measurement; for instance, PSR 18 has three items, whereas PSR 2 has 22 items, with no overlapping items. This raises questions about whether a scale with just two items can measure the same phenomenon to the same extent as a scale with 22 items.

We found that there is a significant lack of standardization and uniformity in the measurement of PSI and PSR in influencer marketing. Both PSI and PSR are measured using a large number of different scales that vary in content and length. There could be two reasons for this diversity. First, the nearly 40-year period of developing different scales has provided researchers with a wide range of tools for measurement, which they further adapted and combined in ways that suited their specific studies. It seems that the established practice among researchers studying PSI and PSR in influencer marketing is to select one or more established scales, choose the items they find suitable for their specific study, and add other items as needed. As a result, PSI was measured with 26 scales in 32 studies, and PSR was measured with 29 scales in 40 studies.

Another reason for such heterogeneous measurement of both concepts is the lack of clear and logical conceptual clarification of PSI and PSR and, consequently, the empirical clarification of what PSI and PSR actually are in influencer marketing and which dimensions they encompass.

Due to the significant heterogeneity in measurement, it raises the question of whether the findings from studies that measure PSI and PSR in such diverse ways are even comparable.

The answer to the research question of if there are predominant scales for measuring PSI and PSR in influencer marketing is no. As explained earlier, the measurement tools for PSI and PSR in influencer marketing are numerous and highly varied. The only predominant feature we observed in both PSI and PSR scales is that the majority of scales we studied draw from the PSI Scale. Among the 26 scales measuring PSI, 23 derive items from the PSI Scale, and among the 29 scales measuring PSR, 14 draw from the PSI Scale. Thus, we can conclude that there is no single predominant scale for measuring PSI and PSR in influencer marketing, but items from the extensive 20-item PSI Scale frequently appear in many scales. Therefore, the scale that has been the subject of much criticism for allegedly measuring PSR instead of PSI, as its name suggests, still serves as a common basis for developing new scales for both PSI and PSR measurement.

The reasons for drawing from the same scales are likely simplicity and trust. Researchers rely on frequently used scales from the past when measuring the concepts included in their studies.

In conclusion, we find that the scales used to measure PSI and PSR in influencer marketing do not differentiate between the two distinct constructs of PSI and PSR, despite calls from numerous authors over the past 20 years to do so. While many of the articles we reviewed differentiate between PSI and PSR at the theoretical level and briefly explain the main differences in the introduction or literature review, this distinction is not reflected at the empirical level.

As noted above, the scales for measuring PSI and PSR often draw from the same sources. Most frequently, scales draw from the PSI Scale, followed by the Audience-Persona Scale—eight scales for measuring PSI and four scales for PSR. Additionally, one scale for measuring PSI and one scale for measuring PSR draw from the PSI-Process Scale.

The issue extends further. Dibble, Hartmann, and Rosaen, as well as Schramm and Hartmann, emphasize that the PSI Scale primarily measures long-term PSR rather than PSI. The Audience-Persona Scale, according to its authors, measures “positive long-term involvement”, yet items from this scale appear in eight scales for measuring PSI. Simultaneously, one scale for measuring PSR draws from the PSI-Process Scale, which was designed to measure PSI.

We also identified two scales that are used in identical form to measure both PSI and PSR. The first scale was used to measure PSI in seven articles and PSR in three articles. The second scale was used once to measure PSI and once to measure PSR.

This raises questions about whether these scales truly measure two different constructs or what they are actually measuring. Do the scales intended to measure PSI between influencers and followers, which draw from scales originally meant to measure PSR, genuinely measure PSI? Do these scales, based on such items, possess sufficient content validity?

To conclude, the current problem with measuring both PSI and PSR between influencers and followers is twofold. Firstly, the measurement of both constructs is overly heterogeneous, as it involves a large number of highly varied scales, differing so much that it questions the comparability of study results.

Secondly, there is a lack of conceptual and empirical differentiation between the constructs, leading to two different constructs being measured by scales that can be very similar or even identical. We believe that it is not possible to measure two different constructs with the same or very similar instruments.

Limitations and Future Research

In our literature review, we limited our scope to the Scopus database and to scientific articles published in English. We used two key search terms in our investigation; however, employing a broader set of keywords might have captured a larger number of scales and uncovered additional measures used for assessing PSI and PSR. Regarding the field, we focused specifically on influencer marketing. Future studies could expand the scope of investigation to include other areas. It would also be worthwhile to explore how PSI and PSR on social media differ from PSI and PSR in traditional media, as social media platforms offer significantly more opportunities for interaction compared to traditional media.

We suggest that future research should focus on creating clearer differentiation between PSI and PSR and on developing reliable and valid measurement scales that accurately measure the constructs of PSI and PSR. These scales should then be used in empirical studies in as unchanged a form as possible. This approach will enable easier comparability of research results that use the same scales. Additionally, a comprehensive literature review focusing on the conceptualization, dimensionality, itemization, and underlying theoretical perspectives of PSI and PSR in influencer marketing would be valuable in further refining and standardizing these constructs.

Currently, both constructs are measured with too many varied scales, which are too similar across constructs.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.B.Z.; methodology, B.B.Z.; formal analysis, B.B.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, B.B.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.B.Z.; supervision, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Articles included in the research.

Table A1.

Articles included in the research.

| Title | Authors | Reference | Year | Journal | PSI/ PSR | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Be My Friend! Cultivating Parasocial Relationships with Social Media Influencers: Findings from PLS-SEM and fsQCA | Eugene Cheng-Xi Aw, Garry Wei-Han Tan, Stephanie Hui-Wen Chuah, Keng-Boon Ooi, Nick Hajli | [53] | 2021 | Information Technology & People | PSR |

| 2 | Blind Trust? The Importance and Interplay of Parasocial Relationships and Advertising Disclosures in Explaining Influencers’ Persuasive Effects on Their Followers | Priska Breves, Jana Amrehn, Anna Heidenreich, Nicole Liebers, Holger Schramm | [13] | 2021 | International Journal of Advertising | PSR |

| 3 | Digital Influencers’ Attributes and Perceived Characterizations and Their Impact on Purchase Intentions | Manuel Joaquim de Sousa Pereira, António Cardoso, Ana Canavarro, Jorge Figueiredo, Jorge Esparteiro Garcia | [54] | 2023 | Sustainability | PSR |

| 4 | Disclosing Influencer Marketing on YouTube to Children: The Moderating Role of Para-Social Relationship | Sophie C. Boerman and Eva A. van Reijmersdal | [55] | 2020 | Frontiers in Psychology | PSR |

| 5 | Disclosure of Vlog Advertising Targeted to Children | Steffi De Jans, Liselot Hudders | [48] | 2020 | Journal of interactive marketing | PSI |

| 6 | Do Digital Celebrities’ Relationships and Social Climate Matter? Impulse Buying in f-Commerce | Abaid Ullah Zafar, Jiangnan Qiu and Mohsin Shahzad | [56] | 2020 | Internet Research | PSR |

| 7 | Do Parasocial Interactions and Vicarious Experiences in the Beauty YouTube Channels Promote Consumer Purchase Intention? | Minsun Lee1 Hyun-Hwa Lee2 | [36] | 2022 | International Journal of Consumer Studies | PSI |

| 8 | Does Familiarity Matter? Examining Model Familiarity in Instagram Advertisements | Lauren Copeland, Jewon Lyu & Jinhee Han | [57] | 2023 | JournaL of Internet Commerce | PSI |

| 9 | Does Parasocial Interaction with Weight Loss Vloggers Affect Compliance? The Role of Vlogger Characteristics, Consumer Readiness, and Health Consciousness | MD Nazmus Sakib, Mohammadali Zolfagharian, Atefeh Yazdanparast | [58] | 2020 | Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | PSI |

| 10 | Effect of Instagram Influencer Parasocial Relationship on Follower Behaviors: A Moderated Moderation Model of Expertise and Involvement | Sara Al Sulaiti Mohamed Slim Ben Mimoun | [59] | 2023 | International Journal of Customer Relationship Marketing and Management | PSR |

| 11 | Endorsement Effectiveness of Celebrities versus Social Media Influencers in the Materialistic Cultural Environment of India | Arpita Agnihotri, Saurabh Bhattacharya | [60] | 2020 | Journal of International Consumer Marketing | PSR |

| 12 | Engaging Fans on Microblog: The Synthetic Influence of Parasocial Interaction and Source Characteristics on Celebrity Endorsement | Wanqi Gong, Xigen Li | [61] | 2018 | Psychology in marketing | PSI |

| 13 | Fancying the New Rich and Famous? Explicating the Roles of Influencer Content, Credibility, and Parental Mediation in Adolescents’ Parasocial Relationship, Materialism, and Purchase Intentions | Chen Lou, Hye Kyung Kim | [62] | 2019 | Frontiers in Psychology | PSR |

| 14 | Followers’ Problematic Engagement with Influencers on Social Media: An Attachment Theory Perspective | Samira Farivar, Fang Wang, Ofir Turel | [63] | 2022 | Computers in Human Behavior | PSR |

| 15 | Fostering Parasocial Relationships with Celebrities on Social Media: Implications for Celebrity Endorsement | Siyoung Chung, Hichang Cho | [29] | 2017 | Psychology & Marketing | PSR |

| 16 | Gender Effects in Influencer Marketing: An Experimental Study on the Efficacy of Endorsements by Same- vs. Other-Gender Social Media Influencers on Instagram | Liselot Hudders and Steffi De Jans | [64] | 2021 | International Journal of Advertising | PSR |

| 17 | Greenfluencing. The Impact of Parasocial Relationships with Social Media Influencers on Advertising Effectiveness and Followers’ Pro-environmental Intentions | Priska Breves, Nicole Liebers | [65] | 2022 | Environmental Communication | PSR |

| 18 | Hedonic and Utilitarian Gratifications to the Use of TikTok by Generation Z and the Parasocial Relationships with Influencers as a Mediating Force to Purchase Intention | Jose A. Flecha-Ortiza | [66] | 2023 | Journal of Interactive Advertising | PSR |

| 19 | Home-based Workouts in the Era of COVID-19 Pandemic: The Influence of Fitness YouTubers’ Attributes on Intentions to Exercise | Hyung-Min Kim | [41] | 2023 | Internet Research | PSR |

| 20 | How an Advertising Disclosure Alerts Young Adolescents to Sponsored Vlogs: The Moderating Role of a Peer-Based Advertising Literacy Intervention through an Informational Vlog | Steffi De Jans, Veroline Cauberghe, Liselot | [44] | 2018 | Journal of advertising | PSI |

| 21 | How and When Social Media Influencers’ Intimate Self-disclosure Fosters Purchase Intentions: The Roles of Congruency and Parasocial Relationships | Kian Yeik Koay | [67] | 2023 | Marketing Intelligence & Planning | PSR |

| 22 | How Do Social Media Influencers Inspire Consumers’ Purchase Decisions? The Mediating Role of Parasocial Relationships | Arif Ashraf | [68] | 2023 | International Journal of Consumer Studies | PSR |

| 23 | How iInstagram Influencers Affect the Value Perception of Thai Millennial Followers and Purchasing Intention of Luxury Fashion for Sustainable Marketing | Akawut Jansom and Siwarit Pongsakornrungsilp | [69] | 2021 | Sustainability | PSI |

| 24 | How Instagram Influencers Contribute to Consumer Travel Decision: Insights from SEM and fsQCA | Wen-Kuo Chen | [70] | 2023 | Emerging Science Journal | PSI |

| 25 | How Social Media Influencers Foster Relationships with Followers: The Roles of Source Credibility and Fairness in Parasocial Relationship and Product Interest | Shupei Yuan, Chen Lou | [32] | 2020 | Journal of Interactive Advertising | PSR |

| 26 | How to Strategically Disclose Sponsored Content on Instagram? The Synergy Effects of Two Types of Sponsorship Disclosures in Influencer Marketing | Quan Xie and Yang Feng | [71] | 2023 | International Journal of Advertising | PSI |

| 27 | How Video Streamers’ Mental Health Disclosures Affect Viewers’ Risk Perceptions | Lee Yu Hao Lee; Yuan Chien Wen; Wohn Donghee Yvette; | [72] | 2021 | Health Communication | PSI |

| 28 | “I Follow What You Post!”: The Role of Social Media Influencers’ Content Characteristics in Consumers’ Online Brand-related Activities (COBRAs) | Man Lai Cheung, Wilson K.S. Leung, Eugene Cheng-Xi Awd, Kian Yeik Koay | [40] | 2022 | Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | PSR |

| 29 | “I Will Buy What My ‘Friend’ Recommends”: The Effects of Parasocial Relationships, Influencer Credibility and Self-esteem on Purchase Intentions | Nicky Chang Bi, Ruonan Zhang | [39] | 2022 | Journal of Research in InteractiveMarketing | PSR |

| 30 | Impact of Influencers’ Influencing Strategy on Follower Outcomes: Evidence from China | Wenyu Doua, Jintao Wub, Ming Yanc, and Junyi Tangd | [50] | 2023 | Asia Pacific Business Review | PSR |

| 31 | Impacts of Influencer Attributes on Purchase Intentions in Social Media Influencer Marketing: Mediating Roles of Characterizations | Hisashi Masuda, Spring H. Han, Jungwoo Lee | [73] | 2022 | Technological Forecasting & Social Change | PSR |

| 32 | Influence of Parasocial Relationship Between Digital Celebrities and Their Followers on Followers’ Purchase and Electronic Word-of-mouth Intentions, and Persuasion Knowledge | Kumju Hwanga, Qi Zhangb | [35] | 2018 | Computers in Human Behavior | PSR |

| 33 | Influence of Self-disclosure of Internet Celebrities on Normative Commitment: the Mediating Role of Para-social Interaction | Edward Shih-Tse Wang and Fang-Tzu Hu | [74] | 2022 | Journal of Research in Interactive Marketing | PSI |

| 34 | Influencer Marketing in China: The Roles of Parasocial Identification, Consumer Engagement, and Inferences of Manipulative Intent | Chen, Kuan-Ju; Lin, Jhih-Syuan (Elaine); Shan, Yan | [75] | 2021 | Journal of Consumer Behaviour | PSI |

| 35 | Influencers As Endorsers and Followers As Consumers: Exploring the Role of Parasocial Relationship, Congruence, and Followers’ Identifications on Consumer-Brand Engagement | Xiaofan Wei, Huan Chen, Artemio Ramirez, Yongwoog Jeon & Yao Sun | [76] | 2022 | Journal of Interactive Advertising | PSR |

| 36 | Influencers on Social Media as References: Understanding the Importance of Parasocial Relationships | Bo-Chiuan Su, Li-Wei Wu, Yevvon-Yi-Chi Chang, Ruo-Hao Hong | [77] | 2021 | Sustainability | PSR |

| 37 | Instagram and YouTube Bloggers Promote It, Why Should I Buy? How Credibility and Parasocial Interaction Influence Purchase Intentions | Karina Sokolova, Hajer Kefi | [4] | 2019 | Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | PSI |

| 38 | Investigating the Impact of Authenticity of Social Media Influencers on Followers’ Purchase Behavior: Mediating Analysis of Parasocial Interaction on Instagram | Durgesh Agnihotri and Pallavi Chaturvedi, Kushagra Kulshreshtha, Vikas Tripathi | [78] | 2023 | Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics | PSI |

| 39 | Keeping Up with Influencers: Exploring the Impact of Social Presence and Parasocial Interactions on Instagram | Hyosun Kim | [79] | 2021 | International Journal of Advertising | PSI |

| 40 | Making and Breaking Relationships on Social Media: The Impacts of Brand and Influencer Betrayals | Hanna Reinikainen, Teck Ming Tan, Vilma Luoma-aho, Jari Salo | [80] | 2021 | Technological Forecasting & Social Change | PSR |

| 41 | Micro, Macro and Mega-influencers on Instagram: The Power of Persuasion via the Parasocial Relationship, | Rita Conde, Beatriz Casais | [81] | 2023 | Journal of Business Research | PSR |

| 42 | Opinion Leadership vs Para-social Relationship Key Factors in Influencer Marketing | Samira Farivar, Fang Wang, Yufei Yuan | [9] | 2021 | Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | PSR |

| 43 | Overeating with Our Eyes: An Examination of Mukbang Influencer Marketing and Consumer Engagement with Food Brands | Linda Dama, Anne Marie Basaran Borsaib and Benjamin Burroughsa | [82] | 2023 | Journal of Promotion Management | PSI |

| 44 | Parasocial Interaction in Social Media Influencer-Based Marketing: An SEM Approach | Arijit Bhattacharya | [83] | 2023 | Journal of Internet Commerce | PSI |

| 45 | Parasocial Interaction Message Elements and Disclosure Timing in Nano- and Micro-influencers’ Sponsored Content As Alternative Explanations for Follower Count’s Influence on Engagement | Zijian Harrison Gong, Steven Holiday | [84] | 2023 | Journal of Interactive Advertising | PSI |

| 46 | Parasocial Relations and Social Media Influencers’ Persuasive Power. Exploring the Moderating Role of Product Involvement | Delia Cristina Balaban, Julia Szambolics, Mihai Chiric˘ | [85] | 2022 | Acta Psychologica | PSR |

| 47 | Parasocial Relationships with Micro-influencers: Do Sponsorship Disclosure and Electronic Word-of-mouth Disrupt? | Jie Sheng Yi Hui Lee Hao Lan | [86] | 2023 | Internet Research | PSR |

| 48 | Patient Influencers’ Promotion of Prescription Drugs on Instagram: Effects of Illness Disclosure on Persuasion Knowledge through Narrative Transportation | Hyosun Kim | [87] | 2022 | International Journal of Advertising | PSI |

| 49 | Predictors Affecting Effects of Virtual Influencer Advertising among College Students | Namhyun Um | [88] | 2023 | Sustainability | PSI |

| 50 | Promoting Healthy Foods in the New Digital Era on Instagram: An Experimental Study on the Effect of a Popular Real Versus Fictitious Fit Influencer on Brand Attitude and Purchase Intentions | Frans Folkvord; Elze Roes, Elze; Kristen Bevelander | [45] | 2020 | BMC Public Health | PSI |

| 51 | Response to Social Media Influencers: Consumer Dispositions as Drivers | Ainsworth Anthony Bailey, Aditya Shankar Mishra, Khushboo Vaishnav | [52] | 2023 | International Journal of Consumer Studies | PSR |

| 52 | Scientists as Influencers: The Role of Source Identity, Self-Disclosure, and Anti-Intellectualism in Science Communication on Social Media | Annie Li Zhang and Hang Lu | [89] | 2023 | Social Media & Society | PSI |

| 53 | Self-Influencer Congruence, Parasocial Relationships, Credibility, and Purchase Intentions: A Sequential Mediation Model | Kian Yeik Koay, Chee Wei Cheah, and Jia Ying Yap | [90] | 2023 | Journal of Relationship Marketing | PSR |

| 54 | SNS Users’ Para-social Relationships with Celebrities: Social Media Effects on Purchase Intentions | Hyojin Kim, Eunju Ko, and Juran Kim | [91] | 2015 | Journal of Global Scholars of Marketing Science | PSR |

| 55 | Stop the Unattainable Ideal for an Ordinary Me! Fostering Parasocial Relationships with Social Media Influencers: The Role of Self-discrepancy | Eugene Cheng-Xi Aw, Stephanie Hui-Wen Chuah | [92] | 2021 | Journal of Business Research | PSR |

| 56 | “Thanks for Watching”. The Effectiveness of YouTube Vlogendorsements | Juha Munnukkaa, Devdeep Maityb, Hanna Reinikainena, Vilma Luoma-ahoa | [49] | 2019 | Computers in Human Behavior | PSR |

| 57 | The Determinant Factors of Purchase Intention in the Culinary Business in Indonesia That Mediated by Parasocial Interaction and Food Vlogger Credibility | Lilian Pindaa, Kenji Handokob, Sandy Halimc, Willy Gunadi | [93] | 2021 | Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education | PSI |

| 58 | The Development of Reputational Capital—How Social Media Influencers Differ from Traditional Celebrities | Hess, Alexandra C.; Dodds, Sarah; Rahman, Nadia | [94] | 2022 | Journal of Consumer Behaviour | PSI |

| 59 | The Effect of the Promotion of Vegetables by a Social Influencer on Adolescents’ Subsequent Vegetable Intake: A Pilot Study | Frans Folkvord, Manouk de Bruijne | [95] | 2020 | International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health | PSI |

| 60 | The Effects of Social Media Influencers’ Self- disclosure on Behavioral Intentions: The Role of Source Credibility, Parasocial Relationships, and Brand Trust | Fernanda Polli Leite, Paulo de Paula Baptista | [96] | 2021 | Journal of Marketing Theory and Practice | PSR |

| 61 | The Effects of the Standardized Instagram Disclosure for Micro- and Meso-influencers | Boerman, Sophie C. | [97] | 2020 | Computers in Human Behavior | PSI |

| 62 | The Impact of Celebrity Endorsement on Followers’ Impulse Purchasing | Xiaofan Yue, Nawal Hanim Abdullah, Mass Hareeza Ali, Raja Nerina Raja Yusof | [98] | 2023 | Journal of Promotion Management | PSR |

| 63 | The Impact of Familiarity with a Communicator on the Persuasive Effectiveness of Pandemic-Related Fear Appeals Explained Through Parasocial Relationships | Nicole Liebers, Achim Vogel, Priska Breves, Holger Schramm | [99] | 2023 | Mass Communication and Society | PSR |

| 64 | The Impact of the Source Credibility of Instagram Influencers on Travel Intention: The Mediating Role of Parasocial Interaction | Orhan Can Yılmazdog˘an, Rana S¸en Dog˘an, Emre Altıntas¸ | [46] | 2021 | Journal of Vacation Marketing | PSI |

| 65 | Understanding Followers’ Stickiness to Digital Influencers: The Effect of Psychological Responses | Lixia Hua, Qingfei Mina, Shengnan Hanb, Zhiyong Liu | [100] | 2020 | International Journal of Information Management | PSR |

| 66 | Unpacking Unboxing Video-Viewing Motivations: The Uses and Gratifications Perspective and the Mediating Role of Parasocial Interaction on Purchase Intent | Hyosun Kim | [51] | 2020 | Journal of Interactive Advertising | PSI |

| 67 | When Influencers Promote Unhealthy Products and Behaviours: The Role of Ad Disclosures in YouTube Eating Shows | Soontae An, Sieun Ha | [101] | 2022 | International Journal of Advertising | PSI |

| 68 | When Media matters: The Role of Media Richness and Naturalness on Purchase Intentions Within Influencer Marketing | David Chidiac, Jana Bowden | [47] | 2023 | Journal of Strategic Marketing | PSI |

| 69 | “You Are a Virtual Influencer!”: Understanding the Impact of Origin Disclosure and Emotional Narratives on Parasocial Relationships and Virtual Influencer Credibility | Rachel Esther Lim, So Young Lee | [102] | 2023 | Computers in Human Behavior | PSI |

| 70 | You Follow Fitness Influencers on YouTube. But Do You Actually Exercise? How Parasocial Relationships, and Watching Fitness Influencers, Relate to Intentions to Exercise | Karina Sokolova, Charles Perez | [103] | 2021 | Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services | PSR |

| 71 | You Really Are a Great Big Sister—Parasocial Relationships, Credibility, and the Moderating Role of Audience Comments in Influencer Marketing | Hanna Reinikainen, Juha Munnukka, Devdeep Maity, Vilma Luoma-aho | [31] | 2020 | Journal of Marketing Management | PSR |

| 72 | YouTube Vloggers’ Influence on Consumer Luxury Brand Perceptions and Intentions | Jung Eun Lee; Brandi Watkins | [30] | 2016 | Journal of Business Research | PSI |

Appendix B

Table A2.

PSI scales used in the analyzed articles.

Table A2.

PSI scales used in the analyzed articles.

| Scale | Items of the Scale | No. of the Items | Scales from Which (Some) the Items Are Derived | Scale Used in Articles |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSI 1 |

| 5 | EPSI Scale [22] | [72] |

| PSI 2 |

| 8 | PSI-Scale [17] | [30,31,36,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| PSI 3 |

| 9 | PSI-Scale [17] | [61] |

| PSI 4 |

| 2 | PSI-Scale [17] | [4] |

| PSI 5 |

| 13 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [95] |

| PSI 6 |

| 6 | PSI-Scale [17] | [58] |

| PSI 7 |

| 5 | PSI-Scale [17] | [97] |

| PSI 8 |

| 6 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [51,52] |

| PSI 9 |

| 7 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [79] |

| PSI 10 |

| 12 | PSI-Process Scale [20] | [75] |

| PSI 11 |

| 4 | / | [69] |

| PSI 12 |

| 11 | PSI-Scale [17] | [94] |

| PSI 13 |

| 5 | PSI-Scale [17] | [101] |

| PSI 14 |

| 9 | PSI-Scale [17] | [74] |

| PSI 15 |

| 9 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [87] |

| PSI 16 |

| 3 | PSI-Scale [17] | [88] |

| PSI 17 | When watching the clip, I had the feeling that the influencer

| 6 | EPSI-Scale [22] | [84] |

| PSI 18 |

| 4 | PSI-Scale [17] | [83] |

| PSI 19 |

| 5 | PSI-Scale [17] | [82] |

| PSI 20 |

| 2 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [89] |

| PSI 21 |

| 8 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [70] |

| PSI 22 |

| 4 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [102] |

| PSI 23 |

| 3 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [57] |

| PSI 24 |

| 7 | PSI-Scale [17] | [93] |

| PSI 25 |

| 11 | PSI-Scale [17] | [71] |

| PSI 26 |

| 8 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [78] |

Table A3.

PSR scales used in the analyzed articles.

Table A3.

PSR scales used in the analyzed articles.

| Scale | Items of the Scale | No. of the Items | Scales from Which (Some) the Items Are Derived | Scale Used in Articles |

| PSR 1 |

| 10 | PSI-Scale [17] | [73] |

| PSR 2 |

| 22 | Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [81] |

| PSR 3 |

| 6 | PSI-Scale [17] | [35,56,59,91] |

| PSR 4 |

| 8 | PSI-Scale [17] | [30,31,36,44,45,46,47,48,49,50] |

| PSR 5 |

| 9 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [53,92] |

| PSR 6 |

| 12 | PSI-Scale [17] | [62] |

| PSR 7 |

| 6 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [51,52] |

| PSR 8 |

| 6 | PSI-Scale [17] | [55] |

| PSR 9 |

| 13 | PSI-Scale [17] | [60] |

| PSR 10 |

| 5 | PSI-Scale [17] | [100] |

| PSR 11 |

| 13 | PSI-Scale [17] | [32] |

| PSR 12 |

| 4 | PSI-Scale [17] | [9,29,63,90] |

| PSR 13 |

| 5 | PSI-Scale [17] | [103] |

| PSR 14 |

| 13 | PSI-Scale [17] | [96] |

| PSR 15 |

| 6 | PSI-Scale [17] | [80] |

| PSR 16 |

| 13 | Multiple-PSR Scale [21] | [13,65,99] |

| PSR 17 |

| 6 | Multiple-PSR Scale [21] | [77] |

| PSR 18 |

| 3 | PSI-Scale [17] | [40] |

| PSR 19 |

| 16 | PSI-Scale [17] | [39] |

| PSR 20 |

| 5 | PSI-Scale [17] | [76] |

| PSR 21 |

| 7 | PSI-Process Scale [20] | [85] |

| PSR 22 |

| 8 | PSI-Scale [17] | [54] |

| PSR 23 |

| 6 | PSI-Scale [17] | [68] |

| PSR 24 | Cognitive

| 6 | [66] | |

| PSR 25 |

| 9 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [67] |

| PSR 26 |

| 7 | PSI-Scale [17] | [86] |

| PSR 27 |

| 7 | PSI-Scale [17] | [41] |

| PSR 28 |

| 8 | PSI-Scale [17] | [64] |

| PSR 29 |

| 8 | PSI-Scale [17] Audience-Persona Scale [19] | [98] |

References

- Dhanesh, G.S.; Duthler, G. Relationship Management through Social Media Influencers: Effects of Followers’ Awareness of Paid Endorsement. Public Relat. Rev. 2019, 43, 101765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abidin, C.; Ots, M. Influencers Tell All? Unravelling Authenticity and Credibility in a Brand Scandal; Edström, M., Kenyon, A.T., Svensson, E.-M., Eds.; Nordicom: Göteborg, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lou, C.; Yuan, S. Influencer Marketing: How Message Value and Credibility Affect Consumer Trust of Branded Content on Social Media. J. Interact. Advert. 2019, 19, 58–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, K.; Kefi, H. Instagram and YouTube Bloggers Promote It, Why Should I Buy? How Credibility and Parasocial Interaction Influence Purchase Intentions. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 53, 101742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, C.; Farrell, J.R. More than Meets the Eye: The Functional Components Underlying Influencer Marketing. Bus. Horiz. 2020, 63, 469–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, F.F.; Gu, F.F.; Palmatier, R.W. Online Influencer Marketing. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2022, 50, 226–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southgate, D. The Emergence of Generation Z And Its Impact in Advertising. J. Advert. Res. 2017, 57, 227–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Veirman, M.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. Marketing through Instagram Influencers: The Impact of Number of Followers and Product Divergence on Brand Attitude. Int. J. Advert. 2017, 36, 798–828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Yuan, Y. Opinion Leadership vs. Para-Social Relationship: Key Factors in Influencer Marketing. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 59, 102371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tafesse, W.; Wood, B.P. Followers’ Engagement with Instagram Influencers: The Role of Influencers’ Content and Engagement Strategy. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 58, 102303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Influencer Marketing Platform Market Size Worldwide from 2022 to 2025 Statista. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1036560/global-influencer-marketing-platform-market-size/ (accessed on 20 June 2024).

- Djafarova, E.; Rushworth, C. Exploring the Credibility of Online Celebrities’ Instagram Profiles in Influencing the Purchase Decisions of Young Female Users. Comput. Human. Behav. 2017, 68, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breves, P.; Amrehn, J.; Heidenreich, A.; Liebers, N.; Schramm, H. Blind Trust? The Importance and Interplay of Parasocial Relationships and Advertising Disclosures in Explaining Influencers’ Persuasive Effects on Their Followers. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 40, 1209–1229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Archer, C.; Harrigan, P. Show Me the Money: How Bloggers as Stakeholders Are Challenging Theories of Relationship Building in Public Relations. Media Int. Aust. 2016, 1, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C. Social Media Influencers and Followers: Theorization of a Trans-Parasocial Relation and Explication of Its Implications for Influencer Advertising. J. Advert. 2021, 51, 4–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, D.; Wohl, R. Mass Communication and Para-Social Interaction. Psychiatry 1956, 19, 215–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.M.; Perse, E.M.; Powell, R.A. Loneliness, Parasocial Interaction, and Local Television News Viewing. Hum. Commun. Res. 1985, 12, 155–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubin, A.M.; Perse, E.M. Audience Activity and Soap Opera Involvement A Uses and Effects Investigation. Hum. Commun. Res. 1987, 14, 246–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auter, P.J.; Palmgreen, P. Development and Validation of a Parasocial Interaction Measure: The Audience-persona Interaction Scale. Commun. Res. Rep. 2000, 17, 79–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schramm, H.; Hartmann, T. The PSI-Process Scales. A New Measure to Assess the Intensity and Breadth of Parasocial Processes. Communications 2008, 33, 385–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tukachinsky, R. Para-Romantic Love and Para-Friendships: Development and Assessment of a Multiple-Parasocial Relationships Scale Theorizing Development of Parasocial Engagement View Project. Am. J. Media Psychol. 2010, 3, 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, T.; Goldhoorn, C. Horton and Wohl Revisited: Exploring Viewers’ Experience of Parasocial Interaction. J. Commun. 2011, 61, 1104–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebers, N.; Schramm, H. Parasocial Interactions and Relationships with Media Characters—An Inventory of 60 Years of Research. Commun. Res. Trends 2019, 38, 4–31. [Google Scholar]

- Dibble, J.L.; Hartmann, T.; Rosaen, S.F. Parasocial Interaction and Parasocial Relationship: Conceptual Clarification and a Critical Assessment of Measures. Hum. Commun. Res. 2016, 42, 21–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, D.; Strauss, A. Interaction in Audience-Participation Shows. Am. J. Sociol. 1957, 62, 579–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummins, R.G.; Cui, B. Reconceptualizing Address in Television Programming: The Effect of Address and Affective Empathy on Viewer Experience of Parasocial Interaction. J. Commun. 2014, 64, 723–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dibble, J.L.; Rosaen, S.F. Parasocial Interaction as More Than Friendship. J. Media Psychol. 2011, 23, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.A.; Lee, M. Effects of Relationship Types on Customers’ Parasocial Interactions: Promoting Relationship Marketing in Social Media. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2017, 8, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, S.; Cho, H. Fostering Parasocial Relationships with Celebrities on Social Media: Implications for Celebrity Endorsement. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 481–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.E.; Watkins, B. YouTube Vloggers’ Influence on Consumer Luxury Brand Perceptions and Intentions. J. Bus. Res. 2016, 69, 5753–5760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinikainen, H.; Munnukka, J.; Maity, D.; Luoma-aho, V. ‘You Really Are a Great Big Sister’–Parasocial Relationships, Credibility, and the Moderating Role of Audience Comments in Influencer Marketing. J. Mark. Manag. 2020, 36, 279–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, S.; Lou, C. How Social Media Influencers Foster Relationships with Followers: The Roles of Source Credibility and Fairness in Parasocial Relationship and Product Interest. J. Interact. Advert. 2020, 20, 133–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buzeta, C.; De Pelsmacker, P.; Dens, N. Motivations to Use Different Social Media Types and Their Impact on Consumers’ Online Brand-Related Activities (COBRAs). J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 52, 79–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazli-Salehi, R.; Jahangard, M.; Torres, I.M.; Madadi, R.; Zúñiga, M.Á. Social Media Reviewing Channels: The Role of Channel Interactivity and Vloggers’ Self-Disclosure in Consumers’ Parasocial Interaction. J. Consum. Mark. 2022, 39, 242–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, K.; Zhang, Q. Influence of Parasocial Relationship between Digital Celebrities and Their Followers on Followers’ Purchase and Electronic Word-of-Mouth Intentions, and Persuasion Knowledge. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2018, 87, 155–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.; Lee, H.H. Do Parasocial Interactions and Vicarious Experiences in the Beauty YouTube Channels Promote Consumer Purchase Intention? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2022, 46, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E. “I’ll Buy What She’s #wearing”: The Roles of Envy toward and Parasocial Interaction with Influencers in Instagram Celebrity-Based Brand Endorsement and Social Commerce. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 55, 102121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, S.V.; Ryu, E. Instagram Fashionistas, Luxury Visual Image Strategies and Vanity. J. Product Brand Manag. 2020, 29, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bi, N.C.; Zhang, R. “I Will Buy What My ‘Friend’ Recommends”: The Effects of Parasocial Relationships, Influencer Credibility and Self-Esteem on Purchase Intentions. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 17, 157–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, M.L.; Leung, W.K.S.; Aw, E.C.X.; Koay, K.Y. “I Follow What You Post!”: The Role of Social Media Influencers’ Content Characteristics in Consumers’ Online Brand-Related Activities (COBRAs). J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2022, 66, 102940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.M.; Kim, M.; Cho, I. Home-Based Workouts in the Era of COVID-19 Pandemic: The Influence of Fitness YouTubers’ Attributes on Intentions to Exercise. Internet Res. 2023, 33, 1157–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G.; Antes, G.; Atkins, D.; Barbour, V.; Barrowman, N.; Berlin, J.A.; Clark, J.; et al. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, G.; Hudders, L.; De Jans, S.; De Veirman, M. The Value of Influencer Marketing for Business: A Bibliometric Analysis and Managerial Implications. J. Advert. 2021, 50, 160–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jans, S.; Cauberghe, V.; Hudders, L. How an Advertising Disclosure Alerts Young Adolescents to Sponsored Vlogs: The Moderating Role of a Peer-Based Advertising Literacy Intervention through an Informational Vlog. J. Advert. 2018, 47, 309–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folkvord, F.; Roes, E.; Bevelander, K. Promoting Healthy Foods in the New Digital Era on Instagram: An Experimental Study on the Effect of a Popular Real versus Fictitious Fit Influencer on Brand Attitude and Purchase Intentions. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yılmazdoğan, O.C.; Doğan, R.Ş.; Altıntaş, E. The Impact of the Source Credibility of Instagram Influencers on Travel Intention: The Mediating Role of Parasocial Interaction. J. Vacat. Mark. 2021, 27, 299–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chidiac, D.; Bowden, J. When Media Matters: The Role of Media Richness and Naturalness on Purchase Intentions within Influencer Marketing. J. Strateg. Mark. 2023, 31, 1178–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jans, S.; Hudders, L. Disclosure of Vlog Advertising Targeted to Children. J. Interact. Mark. 2020, 52, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munnukka, J.; Maity, D.; Reinikainen, H.; Luoma-aho, V. “Thanks for Watching”. The Effectiveness of YouTube Vlogendorsements. Comput. Hum. Behav. 2019, 93, 226–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, W.; Wu, J.; Yan, M.; Tang, J. Impact of Influencers’ Influencing Strategy on Follower Outcomes: Evidence from China. Asia Pac. Bus. Rev. 2023, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. Unpacking Unboxing Video-Viewing Motivations: The Uses and Gratifications Perspective and the Mediating Role of Parasocial Interaction on Purchase Intent. J. Interact. Advert. 2020, 20, 196–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.A.; Mishra, A.S.; Vaishnav, K. Response to Social Media Influencers: Consumer Dispositions as Drivers. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1979–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, E.C.X.; Tan, G.W.H.; Chuah, S.H.W.; Ooi, K.B.; Hajli, N. Be My Friend! Cultivating Parasocial Relationships with Social Media Influencers: Findings from PLS-SEM and FsQCA. Inf. Technol. People 2022, 36, 66–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, M.J.D.S.; Cardoso, A.; Canavarro, A.; Figueiredo, J.; Garcia, J.E. Digital Influencers’ Attributes and Perceived Characterizations and Their Impact on Purchase Intentions. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boerman, S.C.; van Reijmersdal, E.A. Disclosing Influencer Marketing on YouTube to Children: The Moderating Role of Para-Social Relationship. Front. Psychol. 2020, 10, 3042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zafar, A.U.; Qiu, J.; Shahzad, M. Do Digital Celebrities’ Relationships and Social Climate Matter? Impulse Buying in f-Commerce. Internet Res. 2020, 30, 1731–1762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copeland, L.; Lyu, J.; Han, J. Does Familiarity Matter? Examining Model Familiarity in Instagram Advertisements. J. Internet Commer. 2023, 22, 97–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakib, M.N.; Zolfagharian, M.; Yazdanparast, A. Does Parasocial Interaction with Weight Loss Vloggers Affect Compliance? The Role of Vlogger Characteristics, Consumer Readiness, and Health Consciousness. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 52, 101733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Sulaiti, S.; Mimoun, M.S. Ben Effect of Instagram Influencer Parasocial Relationship on Follower Behaviors: A Moderated Moderation Model of Expertise and Involvement. Int. J. Cust. Relatsh. Mark. Manag. 2023, 14, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnihotri, A.; Bhattacharya, S. Endorsement Effectiveness of Celebrities versus Social Media Influencers in the Materialistic Cultural Environment of India. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020, 33, 280–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, W.; Li, X. Engaging Fans on Microblog: The Synthetic Influence of Parasocial Interaction and Source Characteristics on Celebrity Endorsement. Psychol. Mark. 2017, 34, 720–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, C.; Kim, H.K. Fancying the New Rich and Famous? Explicating the Roles of Influencer Content, Credibility, and Parental Mediation in Adolescents’ Parasocial Relationship, Materialism, and Purchase Intentions. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 2567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farivar, S.; Wang, F.; Turel, O. Followers’ Problematic Engagement with Influencers on Social Media: An Attachment Theory Perspective. Comput. Human. Behav. 2022, 133, 107288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudders, L.; De Jans, S. Gender Effects in Influencer Marketing: An Experimental Study on the Efficacy of Endorsements by Same- vs. Other-Gender Social Media Influencers on Instagram. Int. J. Advert. 2021, 41, 128–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breves, P.; Liebers, N. #Greenfluencing. The Impact of Parasocial Relationships with Social Media Influencers on Advertising Effectiveness and Followers’ Pro-Environmental Intentions. Environ. Commun. 2022, 16, 773–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flecha-Ortiz, J.A.; Feliberty-Lugo, V.; Santos-Corrada, M.; Lopez, E.; Dones, V. Hedonic and Utilitarian Gratifications to the Use of TikTok by Generation Z and the Parasocial Relationships with Influencers as a Mediating Force to Purchase Intention. J. Interact. Advert. 2023, 23, 114–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koay, K.Y.; Lim, W.M.; Kaur, S.; Soh, K.; Poon, W.C. How and When Social Media Influencers’ Intimate Self-Disclosure Fosters Purchase Intentions: The Roles of Congruency and Parasocial Relationships. Mark. Intell. Plan. 2023, 41, 790–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, A.; Hameed, I.; Saeed, S.A. How Do Social Media Influencers Inspire Consumers’ Purchase Decisions? The Mediating Role of Parasocial Relationships. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2023, 47, 1416–1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansom, A.; Pongsakornrungsilp, S. How Instagram Influencers Affect the Value Perception of Thai Millennial Followers and Purchasing Intention of Luxury Fashion for Sustainable Marketing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.K.; Silaban, P.H.; Hutagalung, W.E.; Silalahi, A.D.K. How Instagram Influencers Contribute to Consumer Travel Decision: Insights from SEM and FsQCA. Emerg. Sci. J. 2023, 7, 16–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Feng, Y. How to Strategically Disclose Sponsored Content on Instagram? The Synergy Effects of Two Types of Sponsorship Disclosures in Influencer Marketing. Int. J. Advert. 2023, 42, 317–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.H.; Yuan, C.W.; Wohn, D.Y. How Video Streamers’ Mental Health Disclosures Affect Viewers’ Risk Perceptions. Health Commun. 2021, 36, 1931–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masuda, H.; Han, S.H.; Lee, J. Impacts of Influencer Attributes on Purchase Intentions in Social Media Influencer Marketing: Mediating Roles of Characterizations. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2022, 174, 121246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.T.; Hu, F.T. Influence of Self-Disclosure of Internet Celebrities on Normative Commitment: The Mediating Role of Para-Social Interaction. J. Res. Interact. Mark. 2022, 16, 292–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.J.; Lin, J.S.; Shan, Y. Influencer Marketing in China: The Roles of Parasocial Identification, Consumer Engagement, and Inferences of Manipulative Intent. J. Consum. Behav. 2021, 20, 1436–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, X.; Chen, H.; Ramirez, A.; Jeon, Y.; Sun, Y. Influencers As Endorsers and Followers As Consumers: Exploring the Role of Parasocial Relationship, Congruence, and Followers’ Identifications on Consumer–Brand Engagement. J. Interact. Advert. 2022, 22, 269–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, B.C.; Wu, L.W.; Chang, Y.Y.C.; Hong, R.H. Influencers on Social Media as References: Understanding the Importance of Parasocial Relationships. Sustainability 2021, 13, 10919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]