Abstract

There are two key areas of development across wind turbine blade lifecycles with the potential to reduce the impact of wind energy generation: (1) deploying lower-impact materials in blade structures and (2) developing low-impact blade recycling solution(s). This work evaluates the feasibility of using natural fibres to replace traditional glass and carbon fibres within state-of-the-art offshore blades. The structural design of blades was performed using Aeroelastic Turbine Optimisation Methods and lifecycle assessment was conducted to evaluate the environmental impact of designs. This enabled the matching of blade designs with preferred waste treatment strategies for the lowest impact across the blade lifecycle. Flax and hemp fibres were the most promising solutions; however, they should be restricted to use in stiffness-driven, bi-axial plies. It was found that flax, hemp, and basalt deployment could reduce Cradle-to-Gate Global Warming Potential (GWP) by around 6%, 7%, and 8%, respectively. Cement kiln co-processing and mechanical recycling strategies were found to significantly reduce Cradle-to-Grave GWP and should be the prioritised strategies for scrap blades. Irrespective of design, carbon fibre production was found to be the largest contributor to the blade GWP. Lower-impact alternatives to current carbon fibre production could therefore provide a significant reduction in wind energy impact and should be a priority for wind decarbonisation.

1. Introduction

Most industrialised countries are leaning heavily on the expansion of renewable energy generation to meet net zero targets, with wind being at the forefront of the global green energy transition. The amount of electricity generated by wind increased by almost 273 TWh in 2021, which represents the largest growth of all power generation technologies. Wind remains the leading non-hydro renewable technology, generating 1870 TWh in 2021; almost as much as all other renewable sources combined [1].

While wind energy generation can provide electricity with just 1–6% of the Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions produced by traditional fossil fuels [2], there remains room for improvement within the industry to help accelerate toward global net zero targets. Several authors have conducted lifecycle assessment (LCA) on wind turbine powerplants, concluding that the production of raw materials used during manufacturing is the largest single contributor to wind energy’s GHG emissions [3,4]. Raw material production typically accounts for more than 70% of the total Global Warming Potential (GWP) across the lifecycle of a wind turbine. The wind turbine blades (WTBs) account for just 7–10% of the full powerplant mass; however, the materials used in WTB manufacture have a larger GWP compared to other dominant material in the turbine powerplant (e.g., steel and iron). This is heightened for the current generation of 10+ MW powerplants which almost all use highly impactful carbon fibre in their construction.

Although more than 80% of materials used in current wind powerplants are recyclable [5], the persistent lack of circular, scalable, and low-impact solutions for decommissioned WTBs remains a blight on the wind energy sector. Several studies have demonstrated the potential environmental benefits that could be realised by WTB recycling [6,7,8]. These findings point to two key areas of strategic development across the WTB lifecycle with the potential to yield a reduction in the impact of wind energy generation: (1) deploying lower-impact, more sustainable materials in WTB structures and (2) developing low-impact recycling solutions for WTBs.

This work evaluates the feasibility of using natural fibre reinforcement to replace traditional glass and carbon fibre materials within state-of-the-art offshore WTBs. WTB design is a highly complex and coupled problem to be tackled with many interactions from several fields, for example, the aerodynamic, structural, or control strategy of the wind turbine machine. Thus, multi-disciplinary optimisation (MDO) techniques are favourable as they can effectively navigate complex design spaces and algorithmically find improved solutions in the presence of multiple interacting design trade-offs. Over the past years, a number of tools for designing wind turbines have been created such as Open-FAST [9,10], Cp-Max [11], HAWTopt2 [12], and Aeroelastic Turbine Optimisation Methods (ATOM) [13,14,15]. However, MDO can become computationally very expensive, and thus a trade-off between computational cost versus scope of the MDO study needs to be assessed carefully. Whilst the research is ongoing in this field, there are several blade design and optimisation strategies devised and suggested in [13,16,17], giving confidence and demonstrating the superior end results of using MDO tools in WTB design over traditional, heuristic approaches. Herein, the structural design of WTBs reinforced with the sustainable materials flax, hemp, and basalt fibre was performed using ATOM, which were examined against IEC design load cases (DLCs) [18]. LCA was conducted on selected WTB designs to evaluate the through life environmental impact of new natural-fibre-reinforced WTB designs. Proprietary models have also been developed to assess the environmental impact across a range of WTB end-of-life (EoL) scenarios. This has enabled the matching of new blade material compositions with preferred waste treatment options for the lowest impact across the WTB lifecycle.

Despite the existence of both sustainable fibre materials and advanced robust methodologies to assess the effectiveness of these new materials in WTB designs, very few works have been found to investigate these aspects in depth [19,20,21,22]. To the authors’ knowledge, none of them have followed a detailed material deployment strategy and modelling approach to present quantitative evidence on which materials could potentially meet WTB design requirements with an assessment of their performance as well as of their environmental impact.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Baseline Wind Turbine Blade

The WTB used in this work was developed from the IEA 15 MW reference wind turbine [23] developed as part of the IEA Wind Task 37 by the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) and the Technical University of Denmark (DTU). This specific wind turbine was originally optimised by NREL using the WISDEM system level design tool [23]. The outcome of the design process resulted in a 117 m blade. The load calculations of this specific blade design were performed using state-of-the-art aero-servo-elastic tools developed by NREL and DTU. Due to some buckling and aeroelastic stability issues of this specific blade design (identified in a thorough analysis performed in [24]), a new round of calculations was conducted using ATOM and an optimised blade design was achieved satisfying all the problematic constraints. This exercise resulted in a slightly longer blade of 122 m—the design calculations as well as main characteristics of this blade can be found in [24].

2.2. Blade Structure and Materials

This paper investigates the potential for using three alternative reinforcement fibres within a traditional horizontal axis WTB: flax fibre (FF), hemp fibre (HF), and basalt fibre (BF). Bio-derived natural fibre materials generally present inferior mechanical properties compared to glass fibre (GF) or carbon fibre (CF) counterparts; however, they exhibit excellent specific stiffness compared to that of GF. Therefore, a promising area for deployment of FF/HF is in regions where stiffness is the main design driver. These are mainly the areas of the blade where bi-axial reinforcement is used in sandwich laminates (e.g., shell and shear webs).

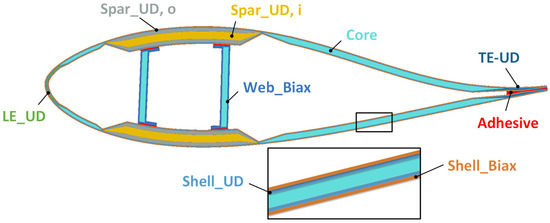

Figure 1 shows a cross-section schematic of the WTB investigated, comprising 2x spar caps, 2x shear webs, high/low pressure shells, and leading edge (LE) and trailing edge (TE) reinforcements. The shells and shear webs are sandwich structures of a PET foam core and fibre-reinforced epoxy. Shear web laminates comprise only bi-axial non-crimp fabric (NCF), and shell laminates are constructed from both bi-axial and unidirectional (UD) NCF layers. The LE reinforcement, TE reinforcement, and spar cap laminates are epoxy-reinforced with UD NCF only.

Figure 1.

Schematic of WTB cross-section and the nomenclature used to describe structural elements.

Several different blade designs were generated for each of the alternative fibre materials investigated. Table 1 describes the WTB scenarios and alternative fibres used and Table 2 describes the fibre deployment and analyses conducted for each WTB scenario. Carbon fibre-reinforced epoxy (CFRP) was used in the “Spar_UD, i” region in all blade designs. The baseline design (Baseline (1)) uses only glass and carbon fibre reinforcement, in line with current industry standard practices. Four blade designs were generated using FF to investigate (1) the feasibility of deploying FF across different blade regions and (2) the influence of FF volume fraction (Vf) (40% and 54%) on bi-axial laminates. Two blade designs were generated using HF to investigate the influence of HF Vf (40% and 54%) in bi-axial laminates. Two blade designs were generated using BF to investigate the effect of CF replacement in the “Spar_UD, i” region. Structural analysis was carried out on all blade designs whereas LCA was conducted on one blade design with each of the alternative fibres as shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

Description of blade scenarios and alternative fibres used in study.

Table 2.

Description of reinforcement fibre deployment across the WTB scenarios, ✔—Analysis conducted, ✖—Analysis not conducted, 1—no CF replacement in “Spar_UD,i” region, 2—CF replacement allowed in “Spar_UD,i” region, 3—Vf of CF and BF in CF/Epoxy and BF/Epoxy plies, respectively, in hybrid spar caps.

2.3. Blade Design Optimisation

The structural design of the reference blade using standard and alternative fibres was performed using ATOM. From an analysis point of view, a set of numerical design variables (DVs) that define each aspect of a turbine can be input by the user. ATOM then performs every step from the meshing of the blade and tower beams, right through to running a full set of aero-servo-elastic DLCs and post-processing results for statistics on power, loads, cross-sectional strains, and failure indices. This analysis capability is integrated within an optimisation framework with a choice of algorithms. The optimisation algorithm searches the design space to find the minimum (or maximum) of the objective function.

The objective function of the optimisation problem was set to consider the GWP of the materials used in the WTB design. The optimisation algorithm therefore searches for the minimum total material production GWP of all the materials in the WTB bill of materials (BoM). The trade-off in this optimisation framework is between the performance and environmental impact of the blade. Materials with adequate mechanical properties and smaller GWP values are favoured by the optimisation algorithm. From preliminary studies conducted by the authors, it was observed that optimisation results are quite sensitive to the GWP value of individual materials. However, in offshore wind turbine blades and more specifically in the IEA 15 MW wind turbine blade, this effect is expected to be limited due to the presence of the carbon fibre UD layers which have relatively high GWP compared to other WTB materials. Design constraints imposed in the blade optimisation of this work are related to strength, buckling, fatigue, tower clearance, and aeroelastic stability of the blade as well as manufacturing constraints related to the taper of the composite plies and the core materials.

Theoretical lamina properties for GF/epoxy, CF/epoxy, FF/epoxy, HF/epoxy, and BF/Epoxy were generated from empirical micromechanical properties of the constituent fibre and epoxy systems (shown in Table A2). UD lamina properties were derived using the Halpin–Tsai method, a semi-empirical model which considers the properties of both the fibre and the matrix, the volume fraction of the fibres, and the geometry of the model composite [25]. The mechanical properties at the ply level along with the density of each material used in the ATOM analysis are listed in Table 3, which includes the appropriate derived knockdown factors described in Appendix B.

Table 3.

Lamina (UD) mechanical properties used during ATOM blade design optimisation.

Appendix B gives a comprehensive description of the optimisation methodology, design load case, micromechanical material properties, and laminate knockdown factors used during the blade design optimisation process.

2.4. Lifecycle Assessment

The LCA has been conducted with reference to the methods provided in the international standards series ISO 14040 related to the preparation of LCA studies [26].

2.4.1. Goal and Scope

The aim of this LCA is to evaluate and compare the Cradle-to-Gate and Cradle-to-Grave impact of a variety of offshore WTB designs constructed with alternative reinforcement fibres. It is intended that the impact of materials, processes, and practices used throughout a typical commercial blade lifecycle (e.g., blade production, service life, and end-of-life operations) be captured within this LCA to best represent their real-world impact. A secondary objective of this LCA is to understand the impact of WTB disposal across a range of EoL scenarios, in order to match WTB designs with preferred waste treatment options for the lowest impact.

Functional Unit

The production of electricity is the main function of a wind power plant. This LCA report focuses on the WTB only, and all other turbine parts have been excluded from the analysis. The Functional Unit for this LCA study is defined as, “The production, use and disposal of one WTB, to be installed on an offshore wind power plant with a lifecycle of 25 years”. The reference flow has been chosen to allow for comparison with blades with different materials and annual energy production (AEP) values and is therefore equal to the fraction of one WTB required to deliver 1 GWh of electricity. The total turbine energy generation and reference flow for the various WTB scenarios analysed in this LCA are described in Table A1.

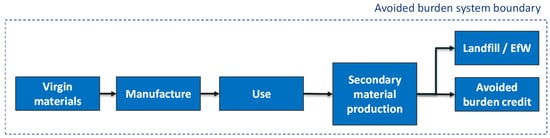

System Boundary

A system expansion was used to include the secondary material production (recycling) within the WTB system boundary, as shown in Figure 2. This method was selected to (1) present the environmental impact of WTB material selections with respect to different EoL scenarios, (2) evaluate open-loop recycling of WTB since closed-loop recycling has yet to be demonstrated as feasible, and (3) accommodate the diversity of secondary materials produced across the different EoL scenarios assessed. By using the avoided burden approach, the following is observed: (1) the burden for virgin materials used is allocated to the system, (2) the burden of secondary material production is included within the system boundary and is allocated to the system, (3) materials recycled at EoL offset the demand for a quantity of virgin counterpart materials, (4) knockdowns in offset rates are included based on loss in performance and the impact this will have on products utilising recycled materials, and (5) all blade waste is either recycled or disposed of in the system boundary and an avoided burden credit is given to secondary materials produced.

Figure 2.

Avoided burden system boundary used in the LCA.

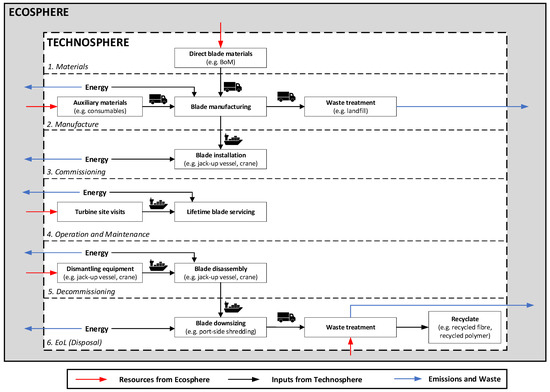

Figure 3 shows the system boundaries of the LCA and processes being assessed. Figure 3 is not exhaustive and is intended for illustrative purposes only, to give an overview of the material and energy flow throughout the system and the resultant waste and emissions produced which are quantified within the LCA.

Figure 3.

LCA system boundary.

Scenarios

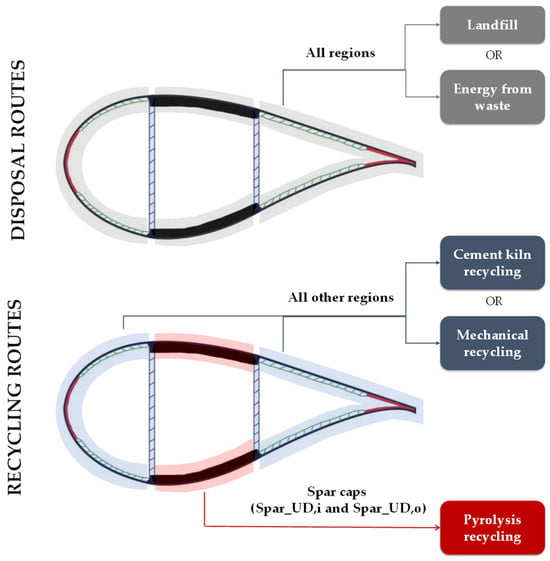

LCA was conducted on the following blade design scenarios: Baseline (1), Flax (2.2.), Hemp (3.2), and Basalt (4.2). Additionally, four EoL scenarios were assessed for each blade scenario: landfill, EfW, cement kiln co-processing, and mechanical recycling. For traditional disposal routes, all the blade mass (except the metallics) is disposed of in landfill or EfW. For recycling routes (cement kiln and mechanical recycling), it is assumed that the spar cap is isolated from the rest of the blade structure during initial sectioning activities or during downstream separation following mechanical downsizing. The spar cap is then recycled using pyrolysis to extract the valuable CF, and all other regions (shear webs, shells, LE/TE reinforcement—which make up approximately 75% of the WTB mass) are then recycled via cement kiln co-processing or mechanical recycling. This is illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Schematic showing how each of the WTB regions are processes at EoL across each EoL scenario.

2.4.2. Lifecycle Inventory

Data Sources

The Lifecycle Inventory (LCI) secondary datasets used in this report have been sourced from the following databases: GaBi Professional Database 2022, Extension database XXII: Carbon Composites 2022, and Extension database VII: Plastics 2022. No LCI primary data have been collected or measured, as the materials and energy flows needed to manufacture the representative blade have been estimated/calculated based on the optimised WTB designs.

Processes and Assumptions in LCI Calculations

The LCA boundary in Figure 3 was selected to capture all major processes used in the blade lifecycle that result in an environmental impact. Various proprietary models have been developed which allow for variation in blade materials and design to alter the LCI data at each lifecycle phase.

Materials: The mass of materials used in each of the blade designs was generated using ATOM blade optimisation as discussed above. Table A1 provides the bill of materials for each of the blade scenarios. The mass of consumables used was estimated using the model outlined in [27]. LCI secondary data from GaBi datasets have been used in the LCA to account for the raw material extraction/production impacts (see Table S43).

Manufacture: A process map used in the WTB manufacturing phase of the LCA is given in Figure S1 and is based on standard blade manufacturing practices described in [27]. The LCA encompasses processes used at each stage where energy/material is input. Transportation of production materials to the manufacturing facility is considered, in addition to transportation and landfilling of production waste. During blade production, waste is generated both from the blade materials and consumables. The waste quantity model for consumable materials was informed by assumptions made in [27], whereas the model for blade materials’ waste was informed by discussion with a major turbine OEM. Manufacturing waste assumptions and LCI data are tabulated in Tables S5–S7. Energy models were developed which are used to estimate the energy input required at each of the production phases. The energy models have been developed with respect to the blade geometry and BoM. The energy model also uses assumptions outlined in [27], in conjunction with input data from primary data captured during analogous operations by the National Composites Centre, equipment data provided by suppliers/manufacturers, and energy models developed from the first principles. LCI data generated from the manufacturing energy model are tabulated in Tables S9–S18.

WTB delivery: Delivery of the WTB from the manufacturer to the offshore wind farm support port is conducted using a Heavy Lift Vessel (HLV). Based on the linear regression of similar reported WTB delivery operations, it was assumed that the HLV could transport 106 WTBs at once. It was assumed the WTB is transported 500 km. The total heavy fuel oil consumption of the HLV during transit was estimated assuming a transit speed of 22 km/h and a fuel consumption rate of 0.93 t/h. The emissions factors for heavy fuel oil are given in Table S20.

Installation: Offshore installation of the WTB is assumed to take place alongside the installation of the WT system following standard industry practices outlined in [28]. This involves portside loading of the WTB onto a self-propelled jackup vessel (JUV), transportation of the WTB to the pre-installed foundation, and lifting and connecting the WTB onto the turbine hub. The model described in [28] was used to estimate the total JUV fuel consumption for one WT installation. The total fuel consumption of the JUV during the WT installation was calculated and fuel allocated to the WTB based on the time contribution of the blade activities to the total WT installation time (see Table S19).

O&M: The impact associated with O&M is assumed to be solely the service operations vessel (SOV) needed to carry out inspection and repair work. The additional material used during WTB repair work is small compared the total material used to produce the blades, therefore the impact of these processes is assumed to be negligible and not included. SOV fuel consumption during regular WT inspections is given in [29] and tabulated in Table S21. It was assumed that the system-wide inspection rate is 1.44 inspections per year [30]. Repair rates for various offshore wind turbine sub-systems were measured as part of the SPARTA program, which found an average of 0.115 repair trips per month per turbine explicitly for turbine rotor repair work [30]. It was assumed that four WTs can be inspect/repaired in parallel from a single SOV [29], with each WTB requiring one or two days per inspection or repair, respectively. The fuel consumption of the SOV during inspection/repair works was allocated evenly across all WT substructures being inspected/repaired.

Decommissioning: Due to the technology immaturity, no standard practices for offshore WT decommissioning exist yet. WTB decommissioning is assumed to be one step of the system-wide WT decommissioning following methods outlined in [28]. This involves decommissioning vessel transit to the offshore wind farm, disconnecting the WTB from the WT hub using a JUV, loading the WTB onto a barge vessel, transporting the barge vessel back to port (using a tugboat), and unloading the WTB portside. The models described in [28] were used to estimate the total JUV and tugboat fuel consumption for one WT’s decommissioning. The total fuel consumption of the JUV during the WT decommissioning was calculated and fuel was allocated to the WTB based on the time contribution of the blade activities to the total WT decommissioning time (see Table S23).

Disposal/Recycling: Processes considered at EoL are the following: (1) downsizing the blade using industrial shredding and granulating equipment; (2) transporting shredded waste to a waste management facility; (3) disposal/recycling of blade waste using the following processes: landfill, energy from waste (EfW), cement kiln co-processing, mechanical recycling, and pyrolysis recycling; (4) transporting recycling waste to a waste management facility; and (5) disposing of recycling waste in landfill. Appropriate Gabi datasets were used to evaluate the impact of landfilling the materials within the WTB structure (see Table S25). Energy models were developed for EfW, cement kiln co-processing [8], mechanical [31], and pyrolysis [32] recycling, based on the best available literature data. Direct emissions from polymer combustion (PET core, laminate epoxy, and PU surface coating) were calculated assuming that polymers are fully combusted to CO2, H2O, and NO2 (for EfW, cement kiln co-processing, and pyrolysis processes). The calorific value of each WTB design was calculated based on their material compositions, which was used as input in modelling the EfW and cement kiln routes. The combustion products and calorific value of various materials used in the LCA are given in Table S28.

EfW: WTB waste can be co-processed with solid municipal waste within well-established EfW facilities. While energy is recovered from the waste, this process is unable to reclaim the non-combustible fractions and is therefore not considered to be a recycling process. Energy generated by EfW is assumed to be in line with the UK average EfW facility efficiency, with electricity assumed to offset the UK grid electricity mix. Bottom ash (carbonous residue and GF fraction) from EfW is assumed to be landfilled.

Cement kiln co-processing: WTB waste is already commercially used as both fuel and raw materials in the production of clinker within cement kilns [8]. WTB waste is an ideal raw material for cement manufacturing since the mineral composition of glass fibre is consistent with the ratio between calcium oxide, silica, and alumina used in clinker production [33]. Combustion of the organic fraction of the WTB waste within cement kilns can be used to heat the process and offset demand for petroleum coke. WTB waste is assumed to offset petroleum coke fuel in a traditional cement kiln and the mineral content is assumed to replace raw minerals within the clinker, using the method outlined in [8].

Mechanical recycling: Many variations of mechanical recycling of composite materials (WTB or otherwise) have been demonstrated, with commercial operations already in existence [34]. In general, the composite is mechanically downsized (shredded and/or granulated) and the resulting granulated recyclate can either be sorted in different fractions or be used directly in the production of secondary materials. Mechanical recycling of WTB waste was modelled using a downsizing and classification process outlined in [31]. WTB waste is first ground using a granulator then separated into three fractions using a classifier. The fractions differ in composition and size, with the process producing a fibre rich “fibrous” fraction, a “coarse” resin rich fraction and a final “powder” fraction. The “fibrous” and “powder” fractions are assumed to replace virgin GF (in low value GFRP) and standard CaCO3 filler, respectively. The “coarse” resin fraction is assumed to be landfilled.

Pyrolysis recycling: The thermal recycling of composites’ waste using pyrolysis involves the decomposition of polymers without (or in low) oxygen at high temperatures between 300 and 800 °C [32]. This is often a multistage process, requiring different temperatures and/or atmospheric conditions to remove thermally stable char residues to reclaim contaminant free fibres. Reclaimed fibres (GF, CF, and BF) can then be used in the production of secondary composite materials. Pyrolysis recycling of the WTB spar caps was modelled using energy inventory data obtained from a commercial operation, reproduced in [32]. It is assumed that all products from the polymer pyrolysis are fully oxidised prior to being released to the environment. It is assumed that reclaimed CF, GF, and BF replace virgin fibre counterparts in the production of secondary composite materials.

Knockdown factors based on loss in mechanical performance were applied to the mechanically recycled “fibrous” fraction and pyrolysed fibres. The knockdown factors were used to define the replacement rate of virgin fibres with recycled counterparts and are given in Table S32. Detailed assumptions used in modelling EoL routes are given in Tables S30 and S31.

Allocation

According to the information provided by GaBi regarding their database; secondary LCI data from the GaBi Sphera database uses allocation when necessary, using integral mass/energy reference values. In scenarios where the blade is recycled at the end-of-life stage, there are always one or more secondary material products produced during the recycling process. The following are allocated to the blade only: (1) the burden of the blade recycling/secondary material production, (2) the burden of the disposal of waste by-products, (3) the avoided burden of all secondary material products, and (4) the avoided burden of energy generation (EfW only).

Cut-Off Criteria

The LCI secondary data for raw materials production have been sourced from the GaBi Sphera database. In general, each LCI dataset covers at least 95% of mass and energy of the input and output flows and 98% of their environmental relevance. For the LCI primary data for blade manufacturing, no formal cut-off criteria have been established, as these have all been calculated and are not direct measurements of masses and energy flows. General exclusions that are part of the cut-off criteria are as follows: human energy inputs to processes; production and disposal of infrastructure and its maintenance; transport of employees to and from their normal place of work and business travel; support functions (R&D, marketing, finance, and management); manufacturing consumables excluded: sandpaper, disc blades, pump oil, and packaging; fugitive GHG emissions during manufacturing (AC units, refrigeration units, and VOCs from polymer curing); material/energy input required for repair works; and primary cutting of blade during decommissioning.

2.5. Lifecycle Impact Assessment

The Impact Assessment Methodology “CML2001-August 2016 update” has been applied, focusing on assessing the following Environmental Impact Indicators:

- Abiotic Depletion (ADP elements) [kg Sb eq.]

- Abiotic Depletion (ADP fossil) [MJ]

- Acidification Potential (AP) [kg SO2 eq.]

- Eutrophication Potential (EP) [kg Phosphate eq.]

- Freshwater Aquatic Ecotoxicity Pot. (FAETP inf.) [kg DCB eq.]

- Global Warming Potential (GWP 100 years) [kg CO2eq.]

- Global Warming Potential (GWP 100 years), excl. biogenic carbon [kg CO2eq.]

- Human Toxicity Potential (HTP inf.) [kg DCB eq.]

- Marine Aquatic Ecotoxicity Pot. (MAETP inf.) [kg DCB eq.]

- Ozone Layer Depletion Potential (ODP, steady state) [kg R11 eq.]

- Photochem. Ozone Creation Potential (POCP) [kg Ethene eq.]

- Terrestric Ecotoxicity Potential (TETP inf.) [kg DCB eq.]

3. Results

3.1. Blade Design Optimisation

Simulations were performed in ATOM with parameter settings as described in Section 2.3. Initially, one simulation to optimise the Baseline (1) design was conducted. Eight simulations then followed, which corresponded to the different alternative fibre scenarios listed in Table 1. The AEP for every blade design scenario was found to be similar (as shown in Table A1). This is attributed to the specific set up of the optimisation process in which DVs related to the external geometry of the blade were not considered. Thus, the planform for all the different blades was kept the same and only the thickness of each laminate at the various stations along the blade length was modified.

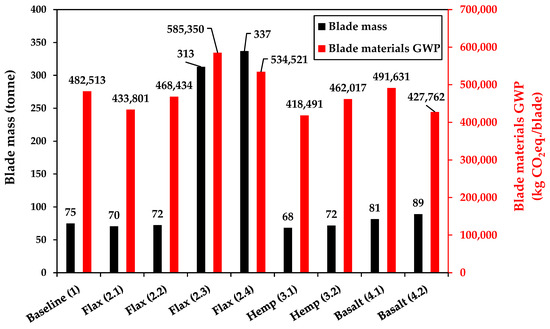

Blade mass and material GWP results are summarised in Figure 5, showing that the Flax (2.1/2.2) and Hemp (3.1/3.2) scenarios result in blade mass savings while the Flax (2.3/2.4) and Basalt (4.1/4.2) scenarios produce heavier blade designs compared to Baseline (1). The ability of FF and HF to drive down the blade mass is attributed to the appropriate deployment of the fibres in the blade, by replacing only the GF bi-axial layers in the shear web and shell components. This takes advantage of the superior specific stiffness of the FF/epoxy and HF/epoxy laminates. The best results were achieved by the Hemp (3.1) scenario, offering 8.9% and 13.2% reductions in WTB mass and total WTB material GWP, respectively. While the production of FF [35] and HF [36] reinforced polymer composites with Vf greater than 40% has been demonstrated, it is believed that a Vf of 40% best represents what is achievable using the vacuum-assisted resin infusion methods used in commercial WTB manufacturing. Flax (2.2) and Hemp (3.2) are therefore believed to be more representative of what is possible using established technologies and were therefore selected for LCA.

Figure 5.

Comparison of total blade mass (tonne) and blade material GWP for each of the scenarios investigated.

Regarding Basalt (4.1/4.2), the alternative fibre deployment strategy was less effective and the resulting WTB designs were heavier than Baseline (1). Despite this, Figure 5 shows that the Basalt (4.2) scenario results in a considerably lower WTB material. This is due to the trade-off between blade mass and material GWP. With respect to the objective function, the optimiser will tend to remove material with higher GWP and replace it with less impactful materials. For Basalt (4.1), the thickness of the CFRP in the spar caps of the blade was kept constant during the optimisation process; while in the Basalt (4.2) scenario, the spar cap thickness was a DV. The optimiser in Basalt (4.2) tended to gradually displace some of the CF material by progressively adding more BF material. Although that action added mass in the blade, it is beneficial for the total blade material GWP value. The methodology used in generating the Basalt (4.1) scenario restricted the deployment of BF in the spar cap to limit CF replacement by BF. This was conducted as a means of limiting the growth of WTB designs when BF was used. Despite this approach, the mass of Basalt (4.1) remains greater than the Baseline (1) scenario. While BF/epoxy’s longitudinal (UD) specific properties are superior to GF/epoxy in the Baseline (1) WTB, the specific transverse properties are lower than GF/epoxy. This is a result of higher BF density compared to GF and the transvers properties being matrix-dominated. Ultimately, this results in a greater required mass for BF-reinforced WTB designs (compared to GF-reinforced), regardless of whether CF displacement in the spar cap is limited or not.

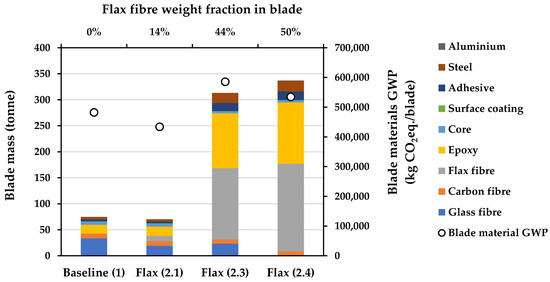

3.1.1. Influence of Flax Fibre Deployment

Figure 6 shows the effect of the different FF deployment strategies across the WTB regions on both the blade mass and resulting GWP of materials used in blade design. As FF is allowed to progressively increase GF displacement in different blade regions (going from Flax 2.1 → Flax 2.3 → Flax 2.4), the mass of FF/epoxy laminates required in highly stressed components of the WTB grows rapidly. This is because performance constraints could not be satisfied easily with the poor UD properties of FF/epoxy (compared to GF/epoxy). This has a tremendous effect on the WTB mass, producing blade designs ranging from 71 t (Flax 2.1) up to 336 t (Flax 2.4). Although a similar analysis has not been present for HF, it is believed that a similar phenomenon would be observed given the similarity in FF and HF’s mechanical properties. Figure 6 also shows that the use of more FF material in the blade does not necessarily lead to a lower total blade material GWP even though the FF/epoxy GWP is lower than GF/epoxy.

Figure 6.

Mass of materials in blade designs generated during the flax fibre deployment analysis (compared to the baseline blade).

It is recognised that this study is not exhaustive and other strategies involving smaller to larger areas of the blade could be considered to progressively replace standard materials. Nevertheless, these additional case studies would be unlikely to change the observed trend. Due to the poor strength performance of the natural fibre materials in the longitudinal direction, any attempt to replace glass UD layers in highly stressed areas of the blade would require the use of excessive material to fulfil blade performance requirements. This need for additional material would drive up the CO2eq. mass of the blade as depicted in Figure 6.

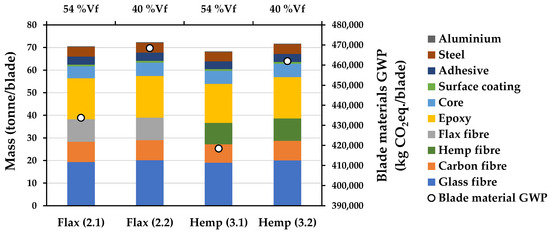

3.1.2. Influence of Natural Fibre Volume Fraction

The effect of different FF and HF Vf (40%, 54%) in FF/epoxy and HF/epoxy material systems is explored in Figure 7. Deployment of FF and HF in Figure 7 is restricted to displacing bi-axial GF in the shear web and shell regions. Figure 7 reveals that the Vf of FF/epoxy and HF/epoxy laminates in these regions influences both the total blade mass and the total blade material GWP value; with the higher FF/HF Vf achieving larger savings in blade mass and total blade material GWP. It should be noted that there is not a contradiction in findings with Figure 6, which shows that increasing the total FF content in WTB significantly increases the blade mass and total blade material GWP. This is caused by extending FF deployment to include displacing UD GF in the shell, LE, TE, and spar regions. On the other hand, FF/HF deployment in Figure 7 is isolated to regions where specific stiffness is the main design driver.

Figure 7.

Comparison of bill of materials and material blade material GWP across the natural fibre laminate volume fractions analysed.

The material properties used in this work were derived from micromechanical models and thus may not align precisely with experimentally measured mechanical properties (laminate strength for example). Stiffness properties estimated from micromechanical models do, however, correlate well with experimentally measured property values [37]. Since FF/HF deployment in Figure 7 is isolated to stiffness/transverse strength-driven regions, it is anticipated that using model-derived FF/epoxy and HF/epoxy mechanical properties will produce representative WTB designs. On the other hand, gradient-based optimisation algorithms used in this study do not guarantee convergence to the global minimum point, and they do not provide any evidence whether the achieved convergence concerns a global or a local minimum. This means that the design solutions in Figure 5 to Figure 7 may be at local minimums, with lower-impact blade designs being located at global minimums that have not been identified. This is important to consider when comparing WTB designs with different fibre types in Figure 7. It is possible that different minimums have been reached across the WTB designs, therefore the designs do not necessarily represent the lowest possible blade material GWP when using each fibre type.

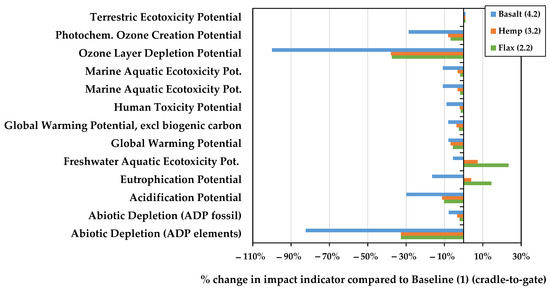

3.2. LCA: Cradle-to-Gate

Figure 8 gives the Cradle-to-Gate LCA results for the Flax (2.2), Hemp (3.2), and Basalt (4.2) WTB scenarios, relative to the Baseline (1) WTB scenario. Flax (2.2) and Hemp (3.2) were selected for LCA because the fibre volume fraction used in these scenarios best represents what is achievable with current blade manufacturing processes for bio-based natural fibre composites [38]. Basalt (4.2) was selected from the two basalt fibre scenarios as the design constraints used allowed for a reduction in carbon fibre usage in the spar cap region, which is the single largest contributor to the blade material GWP.

Figure 8.

Cradle-to-Gate LCA results of alternative blade designs relative to baseline impacts.

The Cradle-to-Gate impact in Figure 8 includes all processes in the production of WTB up to the point the WTB exits the factory gate. The raw Cradle-to-Gate data for each WTB scenario are tabulated in Table S44. Figure 8 shows that most impact indicators are reduced across the WTB designs utilising alternative fibres, except for the Terrestric Ecotoxicity Potential (TEP), Freshwater Aquatic Ecotoxicity Potential (FAEP), and Eutrophication Potential (EP). The FAEP is the toxic effects of substances on freshwater ecosystems causing biodiversity loss and/or species extinction. EP covers the impacts on terrestrial and aquatic environments due to fertilisation or an excess supply of nutrients. The rise in FAEP and EP observed for Flax (2.2)/Hemp (3.2) are a direct consequence of the agricultural practices used during flax and hemp cultivation. Fungicides and pesticides used in food agriculture have been linked to increase FAEP [39,40,41], with similar practices likely used in flax and hemp cultivation resulting in the greater FAEP for Flax (2.2)/Hemp (3.2) WTBs. Similarly, the use of fertilisers in flax and hemp cultivation explains the increase in EP for Flax (2.2)/Hemp (3.2) WTBs.

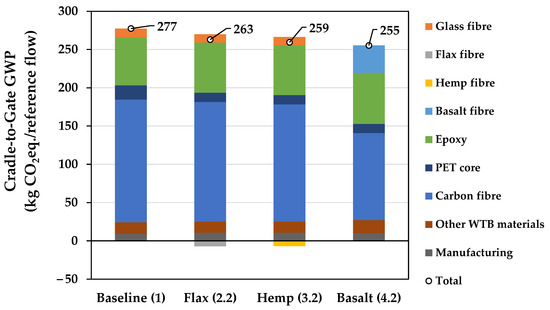

Given the imminent threat that GHG emissions have on environmental and ecological disruption, it is pertinent to single out the GWP as an impact indicator for further examination. Figure 9 shows the contributions toward Cradle-to-Gate GWP for each of the WTB scenarios, split between the production of the various WTB BoM materials and WTB manufacturing. Figure 9 shows that the Cradle-to-Gate GWP is dominated by the impact to produce the WTB materials. The Cradle-to-Gate GWP was found to be reduced in WTB designs which incorporate FF, HF, and BF. This observed reduction in GWP is enabled through a lower impact of raw materials for WTB with alternative fibres. Flax (2.2), Hemp (3.2), and Basalt (4.2) reduce the WTB Cradle-to-Gate GWP by 5.6%, 6.8%, and 8.0%, respectively, when compared to the Baseline (1) WTB design.

Figure 9.

Comparison of the Cradle-to-Gate GWP of the blade scenarios. “Other WTB materials” includes adhesive, metallics, and surface coating. “Manufacturing” includes consumables production, materials transport, manufacturing waste transport and disposal, and impact of energy used during manufacturing processes and facilities’ operation.

Figure 9 shows that CF used in the WTB spar cap is responsible for the greatest contribution of WTB raw material production across the WTB scenarios. While CF comprises <13 wt.% of all WTB design BoMs, CF production has a significantly higher impact than the other materials used in the WTBs. Figure 9 shows that Basalt (4.2) has the lowest Cradle-to-Gate GWP by significantly reducing the fraction of CF used in spar cap reinforcement. As discussed above, this is due to BFRP exhibiting greater UD-specific mechanical properties compared to GFRP, meaning that BF can replace CF in the spar region to a greater extent than GF. This does, however, result in a greater mass of BF and epoxy being used (in Basalt (4.2)) compared to GF (Baseline (1)) and ultimately produced a heavier blade design (see Figure 5).

3.3. LCA: Cradle-to-Grave

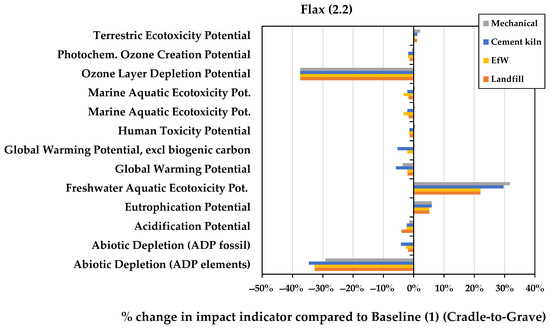

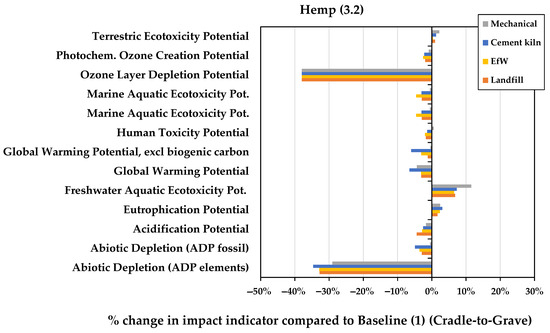

Figure 10, Figure 11 and Figure 12 give the Cradle-to-Grave LCA results across different EoL scenarios for Flax (2.2), Hemp (3.2), and Basalt (4.2) WTBs, respectively. The raw Cradle-to-Grave data for each WTB/EoL scenario are tabulated in Tables S45–S48. As was observed for Cradle-to-Gate impact, Figure 10 and Figure 11 show that Flax (2.2) and Hemp (3.2) have higher TEP, FAEP, and EP compared to the Baseline (1) blade scenario. This is true regardless of the EoL scenario as the higher FAEP and EP is a consequence of processes used during flax and hemp crop cultivation.

Figure 10.

Cradle-to-Grave LCA results of alternative blade designs relative to baseline impacts for Flax (2.2) scenario across different EoL scenarios.

Figure 11.

Cradle-to-Grave LCA results of alternative blade designs relative to baseline impacts for Hemp (3.2) scenario across different EoL scenarios.

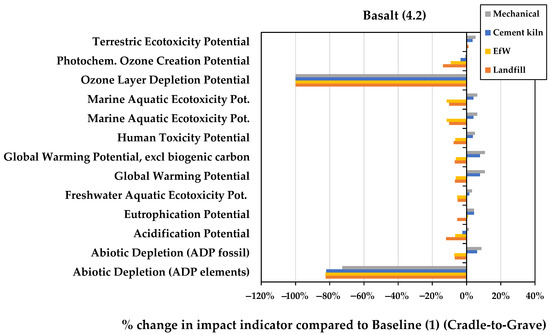

Figure 12.

Cradle-to-Grave LCA results of alternative blade designs relative to baseline impacts for Basalt (4.2) scenario across different EoL scenarios.

Figure 12 shows that the Basalt (4.2) performance against Baseline (1), across most impact indicators, is highly dependent on the EoL scenario analysed. Basalt (4.2) generally scores lower than Baseline (1) across the impact indicators for disposal methods (landfill and EfW). However, for recycling EoL scenarios (cement kiln and mechanical recycling), the Basalt (4.2) generally scores higher than Baseline (1) across the impact indicators. The exceptions are Photochemical Ozone Creation Potential and Ozone Layer Depletion Potential, which are a result of displacing GF with BF in Basalt (4.2) WTB design (and therefore independent of the EoL scenario).

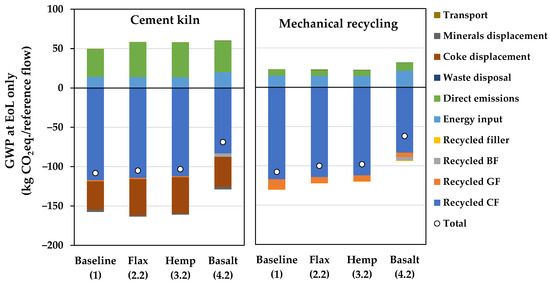

The higher impact of Basalt (4.2) across various indicators, when considering recycling strategies, is attributed to the reduced avoided burden from the secondary material products resulting from recycling this blade. Basalt (4.2) contains a lower CF content compared to the Baseline (1) WTB, as detailed in Table A1. Consequently, the mass of recyclable CF is reduced, leading to a lower avoided burden from recycling this high-impact material. This is demonstrated for GWP in Figure 13, which gives a breakdown of the sources of GWP for cement kiln co-processing and mechanical recycling. Figure 13 shows that most of the GWP credit at EoL is attributable to CF recycling (recycled from the spar cap using pyrolysis) and highlights the importance of ensuring CF is recycled from EoL WTBs. Recycling of the WTB itself at EoL does not reduce the Cradle-to-Gate impact of WTB production. This is because recycled CF cannot be used directly in the production of future WTBs based on current technologies; however, recycled CF can be used in other less demanding applications to displace high-impact CF production.

Figure 13.

Breakdown of sources of GWP for cement kiln co-processing and mechanical recycling.

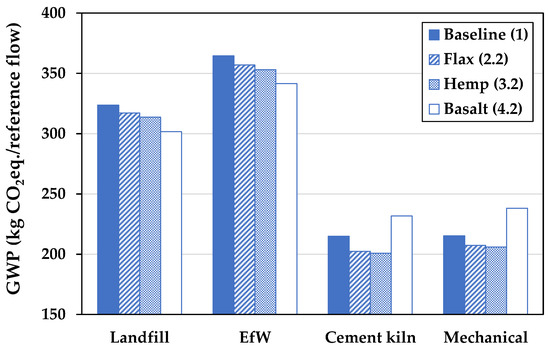

Figure 14 summarises the Cradle-to-Grave GWP of the WTBs across different EoL scenarios. Again, the GWP is being further examined due to the urgent need for global decarbonisation. Figure 14 shows that across all WTB scenarios, traditional disposal methods (landfill and EfW) result in the highest Cradle-to-Grave GWP. This is due to the higher EoL GWP associated with these processes. While EfW can reduce landfill burden, Cradle-to-Grave GWP for all blade scenarios is higher than landfilling. This is because combusting the polymer, FF, and HF fractions in the blade produces direct GHG emissions. Although it is assumed that the electricity generated can offset UK grid electricity generation, the growth in green energy within the current UK grid mix means that electricity produced in the EfW facility has a higher impact than the rest of the grid mix.

Figure 14.

Cradle-to-Grave GWP of blade across different EoL scenarios.

Cement kiln co-processing and mechanical recycling scenarios yield similar Cradle-to-Grave GWPs. Cement kiln co-processing does produce direct GHG emissions through combustion of the polymer, FF, and HF fractions in the WTB; however, it is assumed that the WTB waste offsets traditional petroleum coke fuel which has higher GWP relative to the amount of heat energy released. Overall, the cement kiln route has a net negative GWP in the EoL phase and is a lower-impact route for scrap WTBs compared to landfilling or EfW.

Mechanical recycling is also a promising EoL route for all WTB scenarios in terms of the GWP. One downside to this route is that while most of the WTB mass is recycled, there remains a coarse resin-rich fraction (extracted during granulate classification) which is assumed to not have a use and is therefore landfilled. This is estimated to be about 8 wt.% based on the findings in [42]. The landfilling of this fraction is the reason for the higher GWP when mechanically recycling Flax (2.2) or Hemp (3.2) compared to cement kiln co-processing, seen in Figure 14. When landfilled, FF and HF produce greater amounts of GHG emissions (such as methane), as these bio-based materials can undergo anaerobic digestion within landfills. It is important to note that many variations of WTB mechanical recycling have been proposed, and the assumptions used in this LCA are just based on one published approach [42].

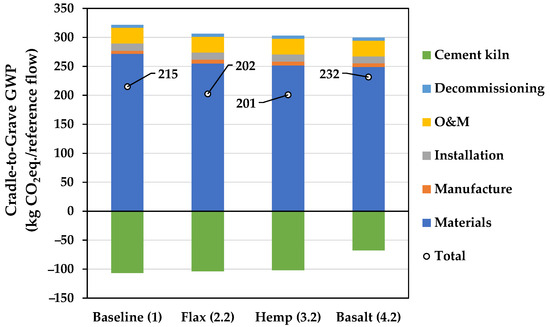

Cement kiln co-processing represents the lowest-impact EoL route across the scenarios; therefore, Figure 15 presents the best-case Cradle-to-Grave GWP for each WTB scenario. The impact of raw material production remains the largest contributor regardless of the WTB scenario. Due to direct vessel emissions, the O&M phase is the second largest contributor to the WTBs’ Cradle-to-Grave GWP. The data in Figure 15 show that Flax (2.2) or Hemp (3.2) have approximately 5% lower GWP compared to Baseline (1). Despite the potential to reduce Cradle-to-Gate GWP (shown in Figure 9), Basalt (4.2) Cradle-to-Grave GWP is approximately 9% higher than the Baseline (1) counterpart (for reasons discussed above). Scaling these findings to a wind farm level is useful to put the change in GWP into perspective. Considering a 1.5 GW offshore wind farm development, with a capacity factor of 40%, the Flax (2.2) and Hemp (3.2) WTB scenarios would be expected to have a total Cradle-to-Grave GWP saving of 1.60 and 1.75 kt CO2eq., respectively. These projected estimates should be taken as indicative, as a full wind farm LCA is required to better understand the impact of alternative fibre deployment in WTBs. The results in Figure 15 do show that there is real opportunity for Cradle-to-Grave GWP reduction (and other impact indicators shown in Figure 10 and Figure 11) with the use of FF and HF reinforcements.

Figure 15.

Cradle-to-Grave GWP of the different WTB scenarios, assuming cement kiln co-processing at EoL.

4. Discussion

This research represents a crucial advancement in demonstrating the viability of incorporating more sustainable fibre reinforcements in WTBs, considering both structural integrity and environmental impact mitigation. Moving towards industrialisation necessitates additional economic analysis. Dittenber and Gangarao show that flax and hemp fibres exhibit comparable costs to E-glass fibre when normalised to load-carrying capacity [43]. However, a techno-economic evaluation specific to blade production is essential to understand the potential cost implications of utilising natural fibres. Moreover, FF and HF are not readily available in formats compatible with standard WTB manufacturing processes, which typically require high areal weight non-crimped fabrics. Consequently, there is a need for the development of natural fibre textiles to facilitate drop-in solutions to existing WTB production lines to avoid costly disruptions. Hemp cultivation also faces various restrictions globally which could limit its utilisation as a WTB reinforcement. Regions such as the United States and European Union allow hemp cultivation but imposed stringent regulations. In contrast, countries like China, which is a major producer of hemp, have fewer restrictions, focusing on its industrial uses. As such, the potential environmental impact is only one set of metrics by which WTB material scenarios should be compared holistically, which should be coupled with an economic and supply chain assessment.

This work has shown the feasibility for alternative, lower-impact reinforcement fibre to be used in large-scale offshore WTB designs as a means of reducing the Cradle-to-Gate and/or Cradle-to-Grave impact. It is important to note that changes in blade design, particularly the blade mass, will have knock-on effects on the rest of the turbine design which will in turn change the impact associated with wind energy generation. Reducing the WTB mass, as was found to be feasible for the Flax (2.2) and Hemp (3.2) WTB designs, could decrease the demand for materials in other sections of the turbine (e.g., tower and drivetrain). The tower represents the greatest material burden in offshore WT production, and savings here could yield significant reductions in WT-level LCA. This can also be evaluated using ATOM’s integrated tower optimiser to produce WT design BoMs and be used as an LCI input to assess the impact on a turbine or wind farm level. It is anticipated that reducing overall turbine mass would further reduce the environmental impact of turbine production, as well as decreasing fuel consumption and the impact associated with transportation, installation, and decommissioning. LCA at both the WT and wind farm levels is therefore needed and forms a key part of the next steps in this research.

Despite the opportunity for impact reduction using natural fibres, raw material production remains the largest contributor to WTB impact across the indicators investigated. CF production is the main contributor to the WTB’s Cradle-to-Gate GWP, accounting for 46–62% of the CO2eq. attributed to the WTB production. With commercial offshore WTs already reaching 18 MW (140 m blade length) [44], CF is critical in creating WTB with the stiffness and strength demanded at these scales. Lower-impact alternatives to CF, or the development of lower-impact CF production, could therefore provide a significant reduction in wind energy impact and should be a priority for wind energy decarbonisation. This could include strategies to reduce the CF production phase such as the electrification of thermal processes [45] and improved production efficiency [46,47,48]. Additionally, accelerating the development of lower-impact precursor fibres should be pursued, such as PAN fibre from bio-derived acrylonitrile [49] (already commercialised by Toray Industries Inc. [50] and Teijin Ltd. [51]) or replacing PAN fibre entirely with lignin fibre [52].

While reduced GWPs were observed, a rise in FAEP and EP indictors was observed for Flax (2.2) and Hemp (3.2), which is attributed to agricultural practices used during flax and hemp cultivation. The ecological impacts of freshwater toxicity and eutrophication differ regionally, and are dependent on whether, and to what extent, agricultural runoff enters ecosystems. The realised impact will therefore vary depending on the location of cultivation and the specific practices used across producers. To reduce the FAEP and EP, adopting sustainable agricultural practices is crucial [53]. Integrated pest management and organic farming can minimise harmful chemical use [54], while precision agriculture ensures efficient resource application [55]. Effective nutrient management and the use of genetically improved crops enhance nutrient uptake and reduce fertiliser dependency [56,57]. Conservation tillage [58] and cover crops [59] help prevent soil erosion and nutrient runoff. And where runoff ultimately occurs, pollutants can be absorbed and filtered before they reach water bodies with the use of riparian buffers and constructed wetlands [60]. It is also important to consider other environmental impacts associated with flax and hemp cultivation that were not captured in the LCA, for example, the impact of increased demand for arable land. The impact of land use is highly dependent on what is being replaced; however, studies have shown agricultural activities and electricity production to be the biggest contributors to the environmental impacts of FF, with contributions due to land use changes being minor in comparison [61].

This study has found that O&M activities account for 8–13% of the WTB Cradle-to-Gate GWP, highlighting the importance of developing sustainable practises for O&M. A limitation of this LCA is the assumption that the O&M requirements for Flax (2.2), Hemp (3.2), and Basalt (4.2) WTBs are the same as the Baseline (1) WTB. Since these alternative fibres have not yet been deployed within an offshore wind environment, a better understanding of material fatigue, erosion, and corrosion is needed. These factors could negatively affect through-life operations (e.g., repair and inspection frequencies) and the life expectancy of wind turbine blades, resulting in additional GWP relative to their energy generated. This additional GWP could supersede any benefits realised in WTB production using alternative fibres. Therefore, a better understanding of the material compatibility with the in-service environment is needed to fully understand the impact of new blade designs. This can be realised by conducting an extensive experimental campaign to characterise durability and fatigue properties of these materials. More specifically, regarding the fatigue properties, i.e., the derivation of SN curves, standard constant amplitude fatigue tests should be performed in at least three different R ratio values (the ratio between minimum and maximum fatigue stress) as specified by certification guideline DNVGL-ST-0376. Furthermore, to protect the leading edge against rain erosion, appropriate experiments should be conducted in rain erosion test systems based on the three-bladed helicopter principle following relevant standards. Finally, appropriate corrosion testing following relevant standards should be conducted to determine the severity in galvanic corrosion, that is, the specific type of corrosion that should be avoided in WTBs according to DNVGL-ST-0376.

This work has shown the importance of adopting recycling strategies for EoL WTBs from an environmental perspective. Cement kiln co-processing was found to reduce the Cradle-to-Grave GWP of Baseline (1), Flax (2.2), Hemp (3.2), and Basalt (4.2) WTB scenarios by 33%, 35%, 35%, and 33%, respectively, when compared to landfilling. This method has the benefit of producing no waste products; however, it does require the combustion of the organic fractions in scrap WTBs. The development of green cement is critical for decarbonisation of the construction sector, and WTB scrap as an alternative lower carbon fuel source could play a role. In kilns where alternative fuels, such as solid recovered fuels, are already being used, it is yet to be established if substitution with WTB scrap will be an environmentally preferable alternative. High-value recycling of composite wind blades is challenging due to the complexity of multi-material structures. These materials are difficult to separate without degrading their quality. Additionally, there is a significant lack of information on blade materials across the supply chain, complicating recycling efforts [62,63]. These factors could be exacerbated by further diversifying WTB materials through the use of natural fibres. It is critical that blade recyclability at the EoL stage is not compromised, and the compatibility of all material selections with recycling technologies (both technically and economically) should be well understood prior to deployment.

5. Conclusions

Various natural fibres were investigated and assessed for their capability to meet the performance requirements of a 15 MW offshore WTB. State of the art design tools were used to produce new promising WTB designs with minimised Cradle-to-Grave environmental impact, assessed using LCA. This work has highlighted the importance of an effective material deployment strategy that could drive down both the blade mass and blade lifetime impact.

Key conclusions from the blade design optimisation are as follows:

- Design load cases could be met by WTBs containing each of the alternative fibres assessed.

- Flax and hemp fibres were the most promising solutions; however, they must be restricted to use in stiffness-driven, bi-axial plies in the shell and shear webs to avoid excessive blade mass requirements.

- Basalt fibre has the potential to replace carbon fibre in the spar cap regions; however, the resulting blade is heavier and turbine level design is needed to understand the knock-on effects to the tower and drivetrain requirements.

- The best results were achieved by the hemp fibre, offering 8.9% and 13.2% reductions in WTB mass and total WTB material GWP, respectively.

Key conclusions from the LCA are as follows:

- Flax and hemp fibre deployment in bi-axial plies could reduce the Cradle-to-Grave GWP by up to 5%. Due to the cultivation methods of these fibres, however, freshwater aquatic ecotoxicity and eutrophication were found to be greater than the baseline blade design.

- Basalt fibre was found to increase the Cradle-to-Grave impact across most indicators compared to the baseline blade design when recycled and is therefore not a priority material for future blade designs.

- Cement kiln co-processing and mechanical recycling EoL strategies were found to significantly reduce the WTB Cradle-to-Grave GWP and should be the prioritised strategies for WTB scrap, regardless of fibre type used.

- Irrespective of blade design, carbon fibre production was found to be the largest contributor to the WTB GWP. Lower-impact alternatives, or the development of lower-impact carbon fibre production, could therefore provide a significant reduction in wind energy impact and should be a priority for wind energy decarbonisation.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16135533/s1, Table S1: Additional WTB data; Table S2: List of design variables (PS: pressure side, SS: suction side); Table S3: Assumptions and materials used in consumables models and mass of consumables used. All waste estimates based on NREL blade cost model; Table S4: Mass of consumables used in all blade scenarios; Table S5: Assumption used in blade production waste model; Table S6: Mass of consumables waste materials in all blade scenarios; Table S7: Mass of blade structural material waste across the scenarios; Figure S1 A high-level process flow of the entire blade manufacturing process used in the baseline impact assessment; Table S8 High-level description of blade manufacturing stages and processes; Table S9 Resin mass and energy of infusion across the blade scenarios; Table S10 Trim lengths, cycle time and energy associated with flash trimming for all blade scenarios; Table S11 Adhesive mass and energy demand for all blade scenarios; Table S12 Cycle time, cart type used and energy demand associated with component transportation within warehouse; Table S13 Cycle time assumptions and crane type to lift, demould and insert the various structures; Table S14 Cycle time and energy demand to lift, demould and insert the various structures for all blade scenarios; Table S15 Sanding area, cycle time and energy demand during blade surface sanding; Table S16 Spray area, cycle time and energy demand during coatings application; Table S17 Cure schedule and energy required during thermal post curing for each of the blade scenarios; Table S18 Estimated energy demand from facility atmospheric control (HVAC); Figure S2 Different installation methods for WTs; Table S19 Installation operation duration; Table S20 Emissions factors in case of combustion of 1kg of heavy fuel oil; Table S21 Fuel consumptions assumptions made in O&M model; Table S22 Emissions factors in case of combustion of 1kg of heavy fuel oil; Table S23 Decommissioning operation duration; Figure S3 Maximum throughput and relative energy demand of a range of shredders with differing capacities as provided by Summit System; Table S24 Assumed transportation distances for WTB waste; Table S25 Assumptions and datasets used for landfilling the various blade materials; Figure S4 Process flow for WTB disposal in landfill; Figure S5 Process flow for WTB disposal using incineration with energy recovery; Figure S6 Process flow for WTB co-processing in cement kiln; Table S26 Mechanical recycling fractions; Figure S7 Process flow for WTB disposal using mechanical recycling; Figure S8 Process flow for WTB spar cap recycling using pyrolysis process; Table S27 Energy input during pyrolysis recycling; Table S28 Chemical composition, combustion products and calorific value of various materials used in LCA; Table S29 Aggregated calorific value of wind blade waste from each of the scenarios assessed; Table S30 Composition of model composite used in fibre knockdown assessment; Table S31 Input data used to calculate composite tensile strength using recycled fibres; Table S32 Fibre knockdown factors calculated for each recycling routes; Table S33 Energy consumption of the manufacturing process of CBF; Table S34 Specification of fourth generation process line TE BCF 2500-3000; Table S35 Distances between the basalt quarry and the CBF manufacturing site; Table S36 Distances between the CBF manufacturing site and the UK; Figure S9 GaBi Plan model of CBF manufacture & transportation; Table S37 LCI secondary datasets used in the GaBi model of CBF manufacture; Table S38 LCA results related to the production of 1kg of CBF raw material; Table S39: Raw materials densities; Table S40: LCI input-output table to produce 1 kg of PET foam; Table S41: LCI secondary datasets used in the GaBi model of PET foam manufacture; Figure S10 – GaBi Plan for the production of 1kg of PET foam; Table S42 - LCA results related to the production of 1kg of virgin PET foam; Table S43 LCI datasets used from Gabi Sphera; Table S44. Cradle-to-gate LCA results for the various blade designs; Table S45 Cradle-to-grave LCA results for Baseline (1); Table S46 Cradle-to-grave LCA results for Flax (2.2); Table S47 Cradle-to-grave LCA results for Hemp (3.2); Table S48 Cradle-to-grave LCA results for Basalt (4.2). References [64,65,66,67,68,69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90] are cited in the Supplementary Materials.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, K.P. and J.F.; methodology, K.P. and K.B.; software, K.P. and K.B.; validation, F.R. and P.G.; formal analysis, K.P. and K.B.; investigation, K.P. and K.B.; resources, J.F.; data curation, K.P.; writing—original draft preparation, K.P. and K.B.; writing—review and editing, J.F., P.G. and F.R.; visualisation, K.P.; supervision, J.F. and P.G.; project administration, J.F.; funding acquisition, J.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the SusWIND consortium: Net Zero Technology Centre, EDF Renewables UK and Ireland, SSE Renewables, Shell UK, Total Energies, Vestas Wind Systems A/S, Owens Corning and Catapult funding through the Department for Business, Energy & Industrial Strategy.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available in the Supplementary Material.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Bill of Materials and AEP for Blade Designs from ATOM

Table A1.

Bill of materials, AEP, and materials GWP for all blade designs generated using ATOM.

Table A1.

Bill of materials, AEP, and materials GWP for all blade designs generated using ATOM.

| Scenario | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline (1) | Flax (2.1) | Flax (2.2) | Flax (2.3) | Flax (2.4) | Hemp (3.1) | Hemp (3.2) | Basalt (4.1) | Basalt (4.2) | ||

| Mass (tonne) | Total | 74.88 | 70.50 | 72.33 | 313.05 | 336.84 | 68.23 | 71.73 | 81.32 | 89.02 |

| Glass fibre | 33.75 | 19.33 | 20.19 | 23.46 | 0.45 | 19.06 | 20.07 | 0.00 | 0.00 | |

| Carbon fibre | 9.07 | 9.02 | 8.84 | 8.14 | 8.08 | 8.12 | 8.67 | 9.07 | 6.44 | |

| Flax fibre | / | 9.92 | 9.95 | 136.95 | 168.67 | / | / | / | / | |

| Hemp fibre | / | / | / | / | / | 9.48 | 9.95 | / | / | |

| Basalt fibre | / | / | / | / | / | / | / | 39.01 | 46.30 | |

| Epoxy | 16.98 | 18.12 | 18.40 | 105.37 | 117.97 | 17.29 | 18.22 | 18.17 | 19.67 | |

| Core | 5.80 | 5.31 | 5.95 | 3.65 | 3.57 | 5.72 | 5.89 | 5.07 | 5.77 | |

| Surface coating | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.78 | |

| Adhesive | 3.74 | 3.52 | 3.62 | 15.65 | 16.84 | 3.41 | 3.59 | 4.07 | 4.45 | |

| Steel | 4.49 | 4.23 | 4.34 | 18.78 | 20.21 | 4.09 | 4.30 | 4.88 | 5.34 | |

| Aluminium | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | 0.27 | |

| AEP (GWh) | 79.67 | 79.68 | 79.64 | 79.67 | 79.67 | 79.50 | 79.60 | 79.74 | 79.69 | |

| Material GWP (kg CO2eq./blade) | 482,513 | 433,801 | 468,434 | 585,350 | 534,521 | 418,491 | 462,017 | 491,631 | 427,762 | |

| FF/HF/BF laminate fraction | / | 54%Vf | 40%Vf | 54%Vf | 54%Vf | 54%Vf | 40%Vf | 54%Vf | 54%Vf | |

| Reference flow (no. WTB per GWh generated) | 5.021 × 10−4 | / | 5.022 × 10−4 | / | / | / | 5.025 × 10−4 | / | 5.020 × 10−4 | |

Appendix B. Blade Design Optimisation Methodology and Assumptions

Appendix B.1. Methodology

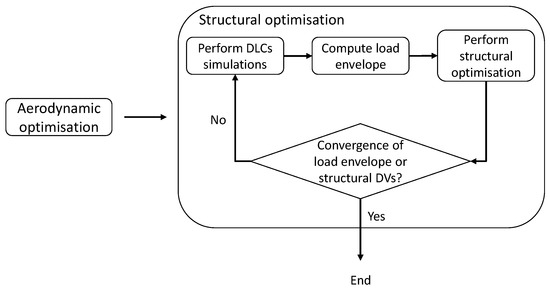

The optimisation algorithm implemented in ATOM is the globally convergent method of moving asymptotes (GCMMA) [91]. GCMMA uses the function values and gradients at each step to generate a convex subproblem that approximates the real objective and constraint functions. If the solution to the subproblem is found to be inaccurate when checked against the real values, then the approximating functions are sequentially modified until they are conservative, resulting in an improved and feasible solution. In ATOM, the user has the capability to simulate either by adopting a monolithic approach, that is, the whole problem is in a single optimisation procedure, or using a distributed architecture, in the frame of this work called “frozen load” optimisation. Distributed architectures decompose the multi-disciplinary optimisation problem into several smaller sub-problems. That is, the aerodynamic and structural design is separated into two sub-optimisation processes. Herein, due to the high computational cost of a monolithic optimisation as well as the large number of different materials to be investigated, the “frozen load” approach was adopted. A diagram of the “frozen load” approach is depicted in Figure A1. The aerodynamic optimisation runs once at the beginning of the process. The structural loop then aims to find a mass-optimal internal structure for the prescribed planform. The structural loop is an iterative procedure in which DLC simulations are run, load envelopes are calculated, and structural optimisation is performed with fixed loads. The loop is repeated until convergence of either the load envelope or the structural DVs. ATOM includes several models and theories necessary to output optimised blade designs such as an unsteady blade element momentum theory, a dynamic stall model, a dynamic wake model, a piecewise linear model to accelerate aeroelastic computations, the turbulent wind field generator TurbSim, an in-house controller, a cross-section modeler calculating cross sectional properties to feed the aeroelastic beam model, and a suite of structural beam models (modal, linear, and nonlinear). Further details in ATOM and the optimisation strategies implemented can be found in [13,14,15,92].

Figure A1.

Diagram of the “frozen load” optimisation approach.

Appendix B.2. Design Variables and Load Cases

Regarding the DVs, only those that affect the internal structure of the blade were considered, that is, the thickness of the various layers/core along the length of the blade structure. The normalised location of the spline control points along the blade length (each one corresponds to one DV) are presented in Table S2.

A reduced set of IEC DLCs [18] (DLC 1.1 and 1.3) were examined as these have been found to offer a good estimate of ultimate blade loads without excessive computational effort [24]. Comparative studies have been conducted in [92] among various reduced load envelopes considering a larger number of critical DLCs to only two DLCs using different fidelity aerodynamic/structural models in ATOM. It was observed that the reduced load envelope (DLC 1.1 and 1.3) with low-fidelity models within the optimisation tends to give conservative results, yet it still produces a blade mass that is competitive with commercial technology trends. An in-depth investigation into the ATOM load envelopes computations and their effect on blade design optimisation can be found in [92].

Appendix B.3. Micromechanical Properties

Table A2.

Micromechanical properties and GWP of fibres used during blade design optimisation.

Table A2.

Micromechanical properties and GWP of fibres used during blade design optimisation.

| Property | Fibre Type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GF | FF | HF | BF | Epoxy | |

| Density [gcm−2] | 2.62 [37] | 1.45 [37] | 1.45 [37] | 2.70 [37] | 1.19 [93] |

| Tensile modulus [GPa] | 78.0 [37] | 60.0 [94] | 56.8 [37] | 91 [95] | 3.2 [93] |

| Tensile strength [MPa] | 1995 [37] | 625 [94] | 585 [37] | 2100 [95] | 65 [93] |

| Compressive strength [MPa] | 1085 [37] | 339.9 2 | 318.2 2 | 1142 2 | 85 [93] |

| Shear modulus [GPa] 1 | 17.2 | 12.0 | 11.4 | 18.2 | Data not required |

| Shear strength [MPa] | Data not required | 43 [37] | |||

| Poisson’s ratio | 0.22 [37] | 0.20 [37] | 0.20 [37] | 0.20 [37] | 0.35 [37] |

| GWP [kg CO2eq./kg] | 1.49 [96] | −1.39 [97] | −1.34 [98] | 1.34 3 | 6.37 [99] |

1 empirical shear modulus data not available, fibres assumed isotropic and shear modulus found by multiplying tensile modulus and Poisson’s ratio; 2 empirical compression strength data not available, applied knockdown factor from fibre tensile strength based on GF data; 3 representative GWP data not available, literature LCI data used (see Table S38).

Appendix B.4. Laminate Knockdown Factors

The material property values derived by the micromechanical models were assumed to be averaged values. Blade design certification standards (DNVGL-ST-0376 [100]) require that design values be used in most of the verification analyses. Design values are derived by applying appropriate partial safety factors that consider various sources of uncertainty such as ageing, temperature effects, or manufacturing defects on the characteristic values of the material properties (i.e., the 5% quantile with 95% confidence level). Therefore, design values are substantially lower compared to the averaged values to consider all the sources of uncertainties that cannot be captured when simple coupon tests are performed. In this case study, due to the lack of experimental data, appropriate knockdown factors were calculated and applied to the derived values. The knockdown factors were calculated by using the material database from the ORE Catapult‘s Levenmouth demonstration turbine in which a comprehensive experimental campaign existed. For every material property, the ratio of the design over its average value was calculated and applied to the respective average value of the property calculated by the micromechanical models. Thus, Table 3 presents material properties including the appropriate derived knockdown factors. Stiffness properties for bi-axial materials were estimated by calculating the equivalent properties of a laminate composed of UD material stacked in the appropriate orientation angles (±45°) using Classical Lamination Theory [101].

References

- IEA. Wind Electricity. 2022. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/wind-electricity (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Pehl, M.; Arvesen, A.; Humpenöder, F.; Popp, A.; Hertwich, E.G.; Luderer, G. Understanding future emissions from low-carbon power systems by integration of life-cycle assessment and integrated energy modelling. Nat. Energy 2017, 2, 939–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonou, A.; Laurent, A.; Olsen, S.I. Life cycle assessment of onshore and offshore wind energy-from theory to application. Appl. Energy 2016, 180, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsaleh, A.; Sattler, M. Comprehensive life cycle assessment of large wind turbines in the US. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 2019, 21, 887–903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khalid, M.Y.; Arif, Z.U.; Hossain, M.; Umer, R. Recycling of wind turbine blades through modern recycling technologies: A road to zero waste. Renew. Energy Focus 2023, 44, 373–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiesura, G.; Stecher, H.; Jensen, J.P. Blade materials selection influence on sustainability: A case study through LCA. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 942, 012011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, P.; Meng, F.; Barlow, C.Y. Wind turbine blade end-of-life options: An eco-audit comparison. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 212, 1268–1281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagle, A.J.; Delaney, E.L.; Bank, L.C.; Leahy, P.G. A Comparative Life Cycle Assessment between landfilling and Co-Processing of waste from decommissioned Irish wind turbine blades. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 277, 123321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenFAST. OpenFAST Documentation v3.5.3. 2024. Available online: https://openfast.readthedocs.io/en/dev/index.html (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- NREL. OpenFAST. Available online: https://www.nrel.gov/wind/nwtc/openfast.html#:~:text=OpenFAST (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Bortolotti, P.; Bottasso, C.L.; Croce, A. Combined preliminary-detailed design of wind turbines. Wind Energy Sci. 2016, 1, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinz, J.C.; Sørensen, N.N.; Zahle, F. Fluid–structure interaction computations for geometrically resolved rotor simulations using CFD. Wind Energy 2016, 19, 2205–2221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macquart, T.; Maes, V.; Langston, D.; Pirrera, A.; Weaver, P.M. A New Optimisation Framework for Investigating Wind Turbine Blade Designs. In Advances in Structural and Multidisciplinary Optimization; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 2044–2060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; Greaves, P.; Weaver, P.M.; Pirrera, A.; MacQuart, T. Efficient structural optimisation of a 20 MW wind turbine blade. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1618, 042025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, S.; MacQuart, T.; Rodriguez, C.; Greaves, P.; McKeever, P.; Weaver, P.; Pirrera, A. Preliminary validation of ATOM: An aero-servo-elastic design tool for next generation wind turbines. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2019, 1222, 012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bottasso, C.L.; Bortolotti, P.; Croce, A.; Gualdoni, F. Integrated aero-structural optimization of wind turbines. Multibody Syst. Dyn. 2016, 38, 317–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavese, C.; Tibaldi, C.; Zahle, F.; Kim, T. Aeroelastic multidisciplinary design optimization of a swept wind turbine blade. Wind Energy 2017, 20, 1941–1953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 61400-1; Wind Turbines -Part 1: Design Requirements, 3rd IEC. International Electrotechnical Commission: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- Lee, J.H.; Collier, C.; Ainsworth, J.; Cho, K.N.; Lee, Y.S. Development of Natural Fiber Wind Turbine Blades Using Design Optimization Technology. 2021. Available online: https://cdn.collieraerospace.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/04/TEAM2021-fullpaper-yslee-Development-of-Natural-Fiber-Wind-Turbine-Blades.pdf (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Shah, D.U.; Schubel, P.J.; Clifford, M.J. Can flax replace E-glass in structural composites? A small wind turbine blade case study. Compos. Part B Eng. 2013, 52, 172–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalagi, G.R.; Patil, R.; Nayak, N. Experimental Study on Mechanical Properties of Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composite Materials for Wind Turbine Blades. Mater. Today Proc. 2018, 5, 2588–2596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miliket, T.A.; Ageze, M.B.; Tigabu, M.T.; Zeleke, M.A. Experimental characterizations of hybrid natural fiber-reinforced composite for wind turbine blades. Heliyon 2022, 8, e09092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaertner, E.; Rinker, J.; Sethuraman, L.; Anderson, B.; Zahle, F.; Barter, G. IEA Wind TCP Task 37: Definition of the IEA 15 MW Offshore Reference Wind Turbine; National Renewable Energy Lab.: Golden, CO, USA, 2020; pp. 1–44. Available online: https://github.com/IEAWindTask37/IEA-15-240-RWT (accessed on 23 April 2024).

- Scott, S.; Greaves, P.; Macquart, T.; Pirrera, A. Comparison of blade optimisation strategies for the IEA 15MW reference turbine. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2022, 2265, 032029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halpin, J.C.; Kardos, J.L. The Halpin-Tsai Equations: A Review. Polym. Eng. Sci. 1976, 16, 293–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]