Abstract

Today’s adolescents will inevitably face the negative effects of climate change and will need to engage in pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) as part of the solutions. The primary objective of this scoping review was to identify the individual, peer and family, and school and community predictors of PEB in adolescence. The secondary objectives were to highlight the main types of PEBs, the main conceptual frameworks examined in adolescence, and the main research gaps mentioned in prior studies. A bibliographic search on multiple databases was conducted. Among the 2578 records identified, 209 were retrieved and assessed for eligibility, and 62 met the inclusion criteria (i.e., peer-reviewed primary research articles published in English in the last ten years with adolescent data). Results reveal a heterogeneous set of correlates with an imbalance favoring individual correlates. The most frequent PEBs in the reviewed studies were linked to energy and water conservation. The most frequent theoretical frameworks were the Theory of Planned Behavior and the Value–Belief–Norm Theory, while the most frequently highlighted research gap was the use of cross-sectional designs. These results can inform the targets of interventions aimed at increasing PEBs, which are fundamental aspects of the psychology of sustainability and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

The latest report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change sends a clear message about the urgency of taking action in response to actual threats posed by climate change [1]. Recent surveys also reveal that adolescents are concerned about the issue of climate change. In a recent survey conducted in ten countries, nearly 60% of the 10,000 youths aged 16 to 25 reported that they felt “very worried” or “extremely worried” about climate change, and over 45% reported that these feelings negatively affected their daily lives [2]. Their voices are thus increasingly being raised, demanding more decisive actions from governments [3].

Today’s adolescents will inevitably face the negative effects of climate change and will need to find solutions [3,4,5]. It is thus crucial to involve them now in the fight against climate change for them to be prepared. Adolescence represents a great window of opportunity for this mobilization since, unlike in adulthood, habits are not yet firmly established or crystallized [6]. Adolescents are naturally curious, receptive, and ready to engage in new behaviors when they understand their meaning and relevance [6]. They are also in the process of forming their identity. As a result, they are more susceptible to influences from their social environment (peers, parents, teachers, social media, etc.) in shaping their values and lifestyle habits [7,8]. Adolescents represent important actors in effecting lasting changes in our society [9,10]. However, as recommended by the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by the United Nations, they need to “have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature” [11]. To assist them along the way, it is important to identify the predictors of pro-environmental behaviors (PEBs) during this specific developmental period, which can be situated at three different levels: (a) individual (e.g., connectedness with nature), (b) peer and family (e.g., communication about environmental issues), and (c) school and community (e.g., participation in afterschool environmental clubs). These predictors are the basis of intervention efforts, which are central to the psychology of sustainability and sustainable development. For example, we need to know more about the psychological processes involved in environmental decisions and behavior so that youths adopt a sustainable lifestyle in the future.

1.1. Definitions of the Concept and the Population

PEB encompasses the actions individuals undertake to reduce environmental harm or actively contribute to the restoration of the natural environment [12]. These behaviors are integral to creating a more sustainable and resilient future, as they contribute to the preservation of natural resources and biodiversity. In this scoping review, PEB is broadly defined as the conscious endeavor of an individual to mitigate the negative impact of their personal activities on the environment [13]. PEB is usually classified in different types of behaviors, such as energy and water conservation (e.g., switching off the lights, turning off the water, and turning off electronics at home), mobility and transportation (e.g., bicycling or walking to school and using public transportation), waste avoidance (e.g., avoiding single-use packages and plastic bags and using refillable water bottles), recycling (e.g., putting the trash in the proper recycling bin), consumerism (e.g., buying environmentally friendly products and decreasing the amount of meat consumed), communication and persuasion (e.g., asking parents to buy seasonal and local products and talking to others about environmental issues), knowledge and interests (e.g., reading about environmental problems and watching environmental documentaries), participatory actions (e.g., using online tools to raise awareness about environmental issues and taking part in a protest about environmental issues), and leadership actions (e.g., organizing an event related to environmental issues and writing to a politician about environmental issues). As can be seen from these different types of behaviors, some require more involvement than others (energy and water conservation versus leadership actions) and some are individual while others are collective (buying environmentally friendly products versus taking part in a protest). There is, therefore, a wide range of PEBs that adolescents can adopt.

Adolescence is usually understood as the transitional period between childhood and adulthood, typically occurring from ages 10 to 20. This developmental period involves rapid physical, cognitive, emotional, and social changes. Examples include significant shifts in physical and sexual characteristics, substantial cognitive advancements, a heightened focus on peer relationships, and the desire for autonomy from parents [14,15]. In this scoping review, adolescence was defined within the range of 12–18 years old to minimize confusion with late childhood and early adulthood. It also helps to pinpoint adolescence in high school ages, which can be valuable for intervention efforts. In addition, it should be noted that we did not consider young environmental “activists”, since the focus of this scoping review was on more normative or typical adolescents.

1.2. Prior Findings on the Predictors of PEB

Multiple literature reviews, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses have been published over the last ten years on the predictors of PEB. Whereas some have focused on specific predictors, such as connectedness with nature [16,17,18], materialistic values [19], self-regulation [20], emotions [21], personality traits [22] or identity [23], others have examined multiple predictors simultaneously [24,25,26]. Overall, findings from the meta-analyses revealed medium-sized associations between the various predictors and PEB [17,18,19,21,22,23,25]. More specifically, in the meta-analysis by [17], which included 75 studies published between 1998 and 2018 conducted among student and non-student samples, results revealed a moderate association (r = 0.37) between nature connection and PEB across different operationalizations, measures, and demographic characteristics. Results from the meta-analysis by [18], which included 26 studies published between 2003 and 2018 conducted among children, university students, and adults, also supported these findings, revealing a moderate association between connection to nature and PEB (r = 0.42). In the meta-analysis by [21], which included 30 studies (years not specified) conducted among student and non-student samples, results revealed a moderate association between anticipated pride (r = 0.47) and anticipated guilt (r = 0.39) and intended and reported PEB. Additionally, results from the meta-analysis by [22], which included 38 studies published between 1999 and 2019 conducted among adolescents and adults, revealed that openness and honesty–humility were the strongest correlates of PEB (r = 0.21 and 0.25, respectively). Agreeableness, conscientiousness, and extraversion were also associated with PEB, but to a lesser extent (r = 0.10, 0.11, and 0.10, respectively). In the meta-analysis by [23], which included 86 studies published between 1992 and 2016 conducted among student and non-student samples, results revealed that the overall concept of identity was moderately associated with PEB (r = 0.34) and that individual identities were more strongly associated with PEB than group identities. Overall, these findings highlight the diverse attitudes and behaviors that can predict PEB in mixed samples of individuals.

To explain why individuals adopt PEB, the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) [27] and the Value–Belief–Norm theory (VBN) [28] are among the most popular conceptual frameworks used by the authors. Both frameworks highlight specific sequences of variables that ultimately predict PEB. In TPB, the sequence begins with our beliefs, which affect our attitudes, our subjective norms, and our perceived behavioral control. These beliefs can refer to the perceived advantages and disadvantages of engaging in behaviors, or to factors that facilitate or hinder the enactment of such behaviors (e.g., time, costs, and availability of infrastructure). Next, our attitudes (e.g., concerns and care for the environment) will influence our willingness to adopt such behaviors. The same goes for our subjective norms, which involve considering the opinions of others regarding the behaviors we should adopt or not. Our perception of control over our behaviors, or the evaluation of our ability to engage in a specific behavior, will also impact our intention to act. If we do not believe we can engage in a behavior, there is little chance that we will have the intention to do it. This intention will then predict whether we will adopt PEB or not (sequence: attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control → intention → behavior).

The VBN also emphasizes the importance of beliefs and perception of behavioral control in explaining the adoption of PEB. However, it gives a more central role to our values (e.g., biospheric and altruistic) and sense of obligation or responsibility to take action. Having a worldview that recognizes the inseparable connections between human activity and its negative impacts on the biosphere is also at the core of this theory (sequence: values → ecological worldview, awareness of consequences, perception of behavioral control → personal norms or sense of obligation/responsibility → behavior). These two sequences highlight the importance of attitudes, values, norms, and perceived behavioral control in predicting PEB.

Even though these findings and explanations contribute to our understanding of factors influencing PEB among individuals, less is known about whether they can apply specifically to adolescents. In the meta-analyses reviewed above, age is either not specified, or considered as a moderator but within large categories (e.g., adults, university students, and children, [18]; student and non-student samples, [21]). Consequently, it is not clear whether the predictors are the same for adults and adolescents. Yet, they may not adopt the same PEBs. For example, unlike adults, most adolescents do not grocery shop, buy a car, or choose the place they want to live in (e.g., urban versus suburban areas). Therefore, the list of PEBs is not necessarily the same in studies that focus on these two age groups. This inevitably impacts the identification of predictors. Moreover, they are not in the same developmental stage and exposed to the same social influences. For example, unlike adults, adolescents have not yet formed a strong environmental identity [29,30]. They may also be more susceptible to parents’ and peers’ influences [7,8]. Moreover, they have more opportunities to adopt PEB in structured settings such as extracurricular activities in their schools or organized clubs in their communities. As a result, focusing on the predictors of PEB among adolescents is important for increasing our understanding of the influencing factors during this unique developmental period. It is also important for guiding intervention efforts aimed at promoting and fostering these behaviors in this specific population.

Given that there is no literature review on the predictors of PEB in adolescence, a scoping review was undertaken to provide an overview of the available studies in this field of research. This type of review is particularly fitting when there is a need to explore emerging evidence before formulating more specific research questions like in a systematic review [31].

1.3. Current Study

To increase our knowledge on the predictors of PEB among adolescents, a scoping review was conducted. Specifically, this review was guided by the following question: what are the (a) individual, (b) peer and family, and (c) school and community predictors of PEB in adolescence? A series of sub-questions were also addressed to further our understanding:

- What types of PEBs are examined in adolescent samples?

- What conceptual frameworks have been used to understand PEB in adolescence?

- What are the main gaps or areas in need of future research identified by the authors of prior studies?

2. Methods

A scoping review is a type of literature review that has a broad focus and does not require assessing the quality of the individual studies [32]. Its main goals are to provide a systematic and replicable summary of the existing literature. In addition, its aims are to map existing empirical data, synthesize key concepts, and identify any gaps or areas of knowledge that require further exploration [33,34]. Five stages are usually conducted in a scoping review, namely “identifying the research question, identifying relevant studies, study selection, charting the data, and collating, summarizing, and reporting the results” [32] (p. 22).

This scoping review was conducted following the methodological frameworks outlined by Arskey and O’Malley [32] and the subsequent developments by Levac et al. [33]. Furthermore, this review adheres to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews guidelines (PRISMA ScR) [35]. The completed PRISMA ScR checklist can be found in Supplemental Material S1. The review protocol was pre-registered with Open Science Framework (ID: osf.io/khs2e).

2.1. Systematic Search Strategy

Studies were identified by searching in four relevant scientific online databases: ERIC—Education Resources Information Center (EBSCO), Education Source (EBSCO), PsycInfo (OVID), and Web of Science Core Collection (CLARIVATE). The first search strategy was conducted on 15 August 2022.

The search strategy was based on two main concepts: adolescents and pro-environmental behavior. For each concept, specific or associated terms in accordance with the controlled vocabulary unique to each database were used (e.g., “adolescent*”, “youth”, “pro-environmental behavi*”, “environmental action”, recycling behavi*”, “high school”). The search strategy was adapted to respect the syntax of the different databases and was first limited to the last 20 years (2002 to present). The list of keywords and the full search strategy for each database are presented in Supplemental Material S2. The initial search in the databases resulted in 2319 sources. The records were exported from each database into a master EndNote library (version 20). The studies were imported into the Covidence® software (version 2020). The duplicates were removed with Covidence.

The selected studies were independently screened by the researchers. Before doing so, a pilot test was conducted to improve mutual understanding of the main concepts (PEB, predictors, and adolescents). Based on a sample of 50 randomly selected studies, the inter-coders agreement was 80% (titles and abstracts). The screening process was then conducted in two steps. In the first step, a preselection was made based on the titles and abstracts. In the second step, the full texts were examined, using inclusion and exclusion criteria. In cases of disagreement, a final decision was made after analysis and discussion.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

In the second step of the process, 181 full-text manuscripts were screened according to four inclusion criteria: (1) only manuscripts published between 2012 and 2022 were included to ensure that findings would be most relevant to the current sociohistorical context, which has seen youth movements taking place all over the world in the fight against climate change (e.g., Fridays for Future); (2) only manuscripts written in English were included, to facilitate the process; (3) only peer-reviewed primary research articles were included, to ensure a minimum level of quality in the selected studies; and (4) only primary research articles with adolescent data were included, given the population under study. Studies that grouped adolescents together with either younger children or older youths were considered for inclusion if data about adolescents could be separated from the other age groups. Alternatively, if at least 50% of the data in the study were specifically related to adolescents based on the sample description, the study was also included. Additional reasons were applied to exclude other research articles. For instance, those with very specific predictors (e.g., taking care of a dog) or those only examining one sociodemographic predictor (e.g., age) were excluded. Finally, a snowballing strategy was used to identify any additional papers from the reference lists of the 49 selected articles that were not found in the initial database searches (titles only). Two additional articles were found and included in the scoping review, for a total of 51 studies. Article selection and both screening rounds were completed by 30 March 2022.

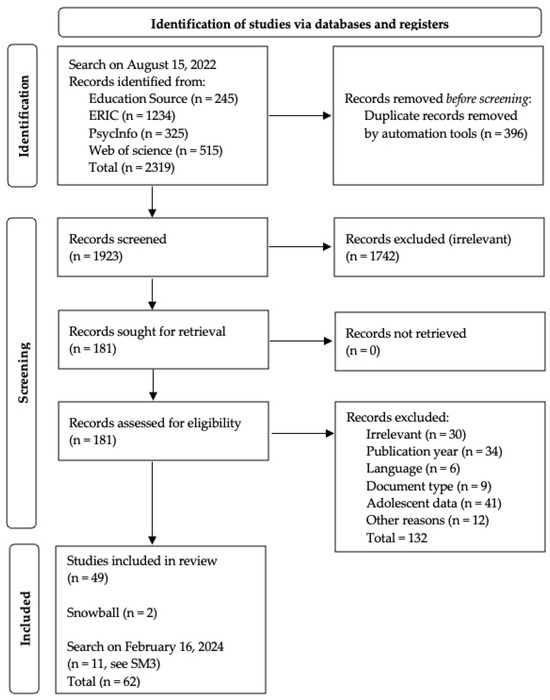

A second search strategy was conducted on 16 February 2024, to include articles that were published between August 2022 and February 2024. The exact same process was used to select the articles. A flowchart depicting this screening process is available in Supplemental Material S3. Eleven additional articles were found and included in the scoping review, for a total of 62 studies. A flowchart depicting all of the screening process is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flowchart based on the PRISMA 2020 flow diagram.

2.2. Data Extraction

Data were extracted using a data extraction tool developed specifically for this study. From each of the 62 selected studies, the data items were (a) the name of the authors, (b) the publication year, (c) the title of the study, (d) the journal and its impact factor, (e) the country where the study was conducted, (f) the study objectives, (g) the theoretical approach, (h) the characteristics of the sample (i.e., size, age, gender, race/ethnicity, and other information), (i) the context (i.e., school or not and part of a larger longitudinal study or not), (j) the method (i.e., study design, number of measurement points, measures of PEB and predictors, control variables, and statistical analyses), (k) the key findings (i.e., types of behaviors and predictors), and (l) the gaps and areas in need of future research. In cases of disagreement, a final decision was made after analysis and discussion. The tool is included in Supplemental Material S4.

3. Results

3.1. Descriptive Information

The relevant data for each included source are summarized in Table 1. As shown in this table, studies were published in various journals, and authors were from multiple countries in the Global North (e.g., United States, Canada, Australia, Denmark, and Sweden) and South (e.g., India, Philippines, Iran, and Indonesia). Regarding study design, only one study was mixed [36]. Among the 61 quantitative studies, only 6 were longitudinal [9,10,37,38,39,40]. In terms of sample characteristics, around 70% of the studies included adolescents aged 12 to 18 years old. In cases where this range was not applicable, the minimum age was 6 years and the maximum age was 22 years, except for one study with a maximum age of 40 years [12]. The most common mean age was around 15 or 16 years. Two studies focused on older adolescents (Ref. [12]: 52% of the sample was between the ages of 12 and 19 years old; Ref. [41]: 17 to 20 years old, with a mean age of 18.4). Regarding gender, most samples included an equal number of males and females. Other key information extracted using the data extraction tool indicated that 82% of the samples were recruited from schools. In terms of statistical analyses used in quantitative studies, multiple regression analyses were used in 53% of cases, structural equation modeling in 42% of cases, and correlations and other types of analyses in 5% of cases. It is important to note that while some studies tested mediating and moderating effects, only direct associations were reported in the main results.

Table 1.

Description of included studies (N = 62).

3.2. Correlates of PEB in Adolescence

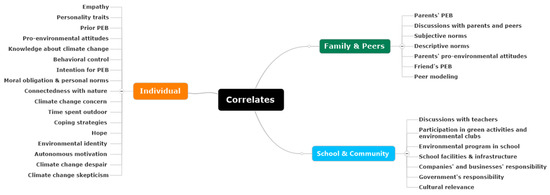

Our central question was to identify the (a) individual, (b) peer and family, and (c) school and community predictors of PEB in adolescence. Given that most studies were cross-sectional, correlates were identified for the most part. Nonetheless, we highlighted the results from longitudinal studies whenever possible. A very large set of correlates was identified through this scoping review, as can be seen in Table 1. For parsimony, we only considered correlates documented in at least two studies, except for school and community correlates, which have received considerably less attention in prior studies. The correlates are presented according to the three different categories. They are also listed in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Overview of the correlates by category.

3.2.1. Individual Correlates

First, multiple studies have looked at sociodemographic factors as correlates of PEB or control variables, including gender, age, ethnicity, living in a rural versus an urban location, parents’ education, and family income. For gender, studies suggest either that there is no significant relationship between gender and PEB [9,12,47,51,58,59,73,74,76,77,79], that females engage in more PEB than males [36,49,63,68,69] or that males engage in more PEB than females [60,85,86,88]. For age or grade, results are also likely to reveal a nonsignificant association with PEB [48,59,74,76,79]. When significant, results reveal that being older was both positively [36,47,68,85,86] and negatively [12,56,57,69] associated with PEB. For adolescents’ ethnicity, results reveal a nonsignificant relationship with PEB [51,58,60,76,77,79], except for Krettenauer et al. [57] who found that Chinese adolescents reported more PEB than Canadian adolescents.

For living in a rural versus an urban setting, two studies reported nonsignificant results [58,76] and two studies reported that living in an urban context was associated with more PEB among adolescents [12,79]. For parents’ education, two studies found no significant relationship [59,68]. Bøheleregen and Wiium [47] found that fathers’ education was not related to adolescents’ PEB, whereas Zhang et al. [85] found the opposite. With respect to mothers’ education, one study found that mothers’ education was negatively related to adolescents’ PEB [47], whereas two other studies found the opposite [37,85]. Finally, for income, whereas Li and Liu [59] found that its relationship with PEB was not significant, Metzger et al. [60] found that it was positively associated with adolescents’ PEB. Overall, these findings tend to suggest that adolescents’ sociodemographic factors are not highly related to their PEB in the set of studies selected for this review. Moreover, in cases where such factors are significantly linked to PEB, the results are mixed.

Among individual correlates not directly related to environmental issues, some studies have looked at empathy and personality traits. For empathy, one study revealed that empathy does not predict PEB [9], whereas another one revealed that empathy is positively associated with PEB [60]. For personality traits, both studies by Poškus [4,70] suggest that adolescents with a positive pattern of personality traits (e.g., high levels of extraversion, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) are more likely to report PEB. Thus, it seems that adolescents who naturally enjoy social interactions and have concerns for the others also adopt more PEB.

Among individual correlates directly related to environmental issues, a central one refers to prior PEB. Among the seven studies with longitudinal data, only four included this predictor in their analyses. Three studies revealed that prior PEB predicted an increase in adolescents’ PEB [36,38,39]. However, another one found no significant predictive association between PEB in childhood and PEB in late adolescence [37].

Our review also reveals that the four most cited correlates and predictors of PEB in adolescence are pro-environmental attitudes and beliefs, knowledge about environmental issues (e.g., climate change), perceived behavioral control (which encompasses self-efficacy and locus of control; [10]), and intention for PEB (27%, 18%, 16%, and 15% of the studies, respectively). This can be explained by the reliance on the TPB or the VBN as the most popular conceptual frameworks in the set of reviewed studies (for more details, see the subsection “Conceptual Frameworks in Adolescence”). With a few exceptions, these four variables are positively related to PEB in adolescence [6,7,43,44,46,48,49,50,52,53,69,70,71,73,74,78,79,83,84,89]. Longitudinal studies also revealed that perceived behavioral control and intention for PEB predicted higher levels of PEB among adolescents [9,39]. Yet, other studies found no significant association between pro-environmental attitudes [3,13,37,38,75], knowledge about environmental issues [84,87], perceived behavioral control [10,51,74,75], and intention for PEB [10] and PEB in adolescence. In their longitudinal study, Ernst et al. [10] even found that an increase in pro-environmental attitudes was related to a decrease in PEB in their adolescent sample. However, overall, studies tend to support the fact that adolescents who have positive feelings, beliefs, and values about the environment, a good understanding of environmental concepts and processes (e.g., what causes climate change), positive expectations about their capability of performing PEB, and a willingness to engage in PEB also adopt more PEB.

Moral emotions or obligations (personal norms) towards PEB, connectedness with nature, and climate change concern were also examined in 10% of the studies. For moral issues, the evidence supports a positive association with adolescents’ PEB [3,7,13,57]. However, the studies by Ernst et al. [10] and Krettenauer [56] reveal no significant link between feeling morally obliged to act in pro-environmental ways and adolescents’ PEB. For connectedness with nature, all other studies suggest that having contact with nature, feeling an emotional connection with nature (e.g., being part of the natural world), and feeling empathetic towards living beings, is associated with PEB in adolescence [12,51,53,56,57,62,82,87]. For climate change concern, adolescents who are worried about climate change also adopt more PEB [43,49,58,77,79,81].

Three other correlates have been examined in 6 to 8% of the studies, namely, time spent outdoor in nature, coping strategies, and hope. For time spent outdoor in nature, studies reported a positive relationship with adolescents’ PEB [37,53,82,87], except for one study, which revealed a nonsignificant relationship [76]. In addition, most studies suggest that adolescents who embrace problem-focused coping strategies (i.e., focusing on ways to solve the problem [39,63,65,67,81]) and have positive goals and thoughts about a better future [55,63,66,77] also adopt more PEB. However, meaning-focused coping strategies (i.e., focusing on beliefs, values, and existential goals) are not consistently linked to PEB among adolescents (a positive association in Ojala [63], but a nonsignificant association in Ojala [65], Ojala and Bengtsson [67], and Wullenkord and Ojala [81]). Concerning coping strategies focused on de-emphasizing the problem or denial, they are negatively associated with adolescents’ PEB [63,65,67]. In addition, moral emotions were not related to adolescents’ PEB in one study [56]. Problem-focused coping strategies and hope thus show a more consistent and positive association with PEB in adolescence.

The other correlates investigated in only two studies include environmental self-identity, autonomous environmental motivation, climate change despair, and climate change denialism or skepticism. For environmental self-identity, results reveal that the extent to which adolescents see themselves as a person who acts in an environmentally friendly way is not consistently associated with their PEB (nonsignificant association in Balundé et al. [3]; positive association in Barata and Castro [46]). For autonomous environmental motivation, both studies that examined this correlate found a positive association with adolescents’ PEB. This suggests that adolescents who report engaging in PEBs because these behaviors are consistent with their desires, interests, goals, and values also adopt more PEB. For climate change despair, results are mixed. The longitudinal study by Veijonaho et al. [40] revealed that climate change despair is positively associated with PEB, whereas the cross-sectional study by Stevenson and Peterson [77] found the opposite. Yet, both studies looking at climate change denialism (or skepticism) found that the more adolescents deny climate change or are skeptical, the less they are likely to adopt PEB [40,69].

3.2.2. Peer and Family Correlates

The most documented correlate concerning adolescents’ family is the adoption of PEB by parents (perceived by adolescents or reported by parents). For the most part, studies suggest that the more parents adopt PEB, the more adolescents will too [41,58,72,80,84]. Yet, Evans et al. [37] found no link between parents’ and adolescents’ PEB. Grønøj and Thøgersen [52] also reported mixed findings depending on whether the parental PEB were perceived by the adolescents (positive association) or reported by parents (no association). Another documented correlate in the peer and family spheres is communication with parents and peers about societal problems, including environmental issues. Results for this correlate are mixed. Two studies reported a positive association with adolescents’ PEB [58,79] and two studies reported no association with adolescents’ PEB [67,82]. It thus seems that the frequency of discussions with parents or peers on societal or environmental problems such as climate change and the way parents or peers respond emotionally during these discussions (e.g., encourage to talk more about their feelings, give advice, and listen) are not consistently associated with adolescents’ PEB.

“Important persons” subjective and descriptive norms have also been examined as correlates of PEB in adolescence. Subjective norms refer to adolescents thinking that important persons surrounding them, such as parents and friends, expect them to adopt PEB or want them to adopt PEB. Descriptive norms refer to adolescents thinking that important persons surrounding them adopt PEB. Results concerning subjective norms reveal that friends’, mothers’, and fathers’ subjective norms are not associated with adolescents’ PEB [7,38]. For descriptive norms, important persons’, friends’, mothers’, and fathers’ descriptive norms are positively associated with adolescents’ PEB in Busch et al. [48] and Collado et al. [7] (only in Study 1). However, this association is negative for important persons for one of the PEBs assessed in Pickering et al. [69] and nonsignificant in the longitudinal study by Gonzalez et al. [38]. Results from these studies thus suggest that thinking that other persons adopt PEB is not clearly associated with the adoption of PEB in adolescence.

Another documented family correlate is the parents’ pro-environmental attitudes or beliefs (perceived or self-reported). Results are also mixed. The association with adolescents’ PEB is positive and significant in one of the longitudinal studies [37]. Yet, like parents’ PEB, Grønøj and Thøgersen [52] also reported mixed findings depending on whether the parental pro-environmental attitudes were perceived by the adolescents (positive association) or reported by parents (no association). Balundé and Perlaviciute [45] also found no association between parents’ pro-environmental beliefs and adolescents’ PEB.

The other peer and family correlates investigated in only two studies are friends’ PEB and having a peer who is a role model for PEB. For friends’ PEB, results reveal a positive relationship with adolescents’ PEB both in one longitudinal study [36] and in one cross-sectional study [84]. For having a peer who is a role model for PEB, one study found that it was not significantly linked to adolescents’ PEB [76]. It also emerged as an important theme in the focus groups conducted by Long et al. [36]. Other important themes that emerged from these focus groups on friends’ influence included their encouragement and direct verbal requests.

3.2.3. School and Community Correlates

Among the correlates related to the school and the community contexts examined in the selected studies, having discussions on climate change with teachers is not associated with PEB in adolescence [79]. Concerning participating in green school activities and environmental clubs, it is associated with more PEB in one study [82]. However, this association is not significant in two other studies [55,76]. In addition, whether schools integrate environmental programs is not significantly related to adolescents’ PEB, but whether they have facilities and infrastructure for PEB (use of renewable energy, bicycle storage, and composting facility) is positively related to their PEB [61,84]. The extent to which adolescents perceived that companies and businesses should be responsible for protecting the environment is also significantly and positively linked to their PEB. This is not the case for government responsibility (no significant association [49]). Lastly, Gould et al. [51] looked at cultural relevance (e.g., traditional cultural practices) and found that it was not significantly related to adolescents’ PEB. Overall, these results suggest that more distal school and community-related correlates are less likely to be associated with PEB in adolescence.

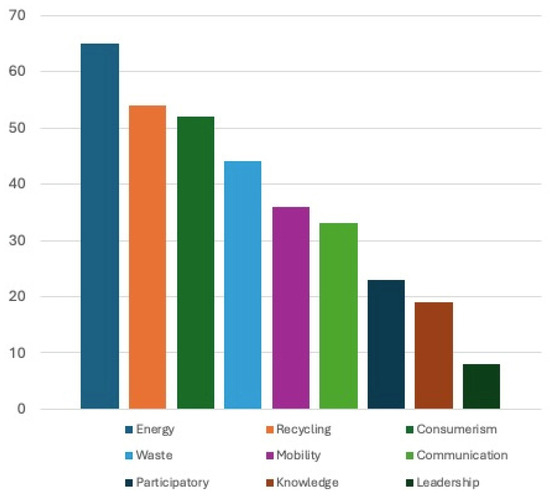

3.3. Types of PEBs in Adolescence

As seen in Figure 3, the most frequent types of PEBs assessed in the reviewed studies could be classified in energy and water conservation (66% across studies), consumerism (55% across studies), recycling (53% across studies), and waste avoidance (44% across studies). The other types of PEBs, such as mobility and transportation (34% across studies), communication and persuasion (31% across studies), participatory actions (29% across studies), knowledge and interests (21% across studies), and leadership actions (7% across studies) are less considered in prior studies. In addition, most studies (80%) included more than one type of PEB in their measure and were thus examined simultaneously in the analyses. However, multiple studies only looked at one type of PEB in their analyses [10,39,43,44,46,47,59,70,71,75,80,84]. A few studies have also verified the associations between correlates and different types of PEBs, revealing different associations depending on the PEB under examination [3,41,43,45,50,52,53,54,61,69,82,89].

Figure 3.

Percentages of types of PEBs examined across studies.

3.4. Conceptual Frameworks in Adolescence

Among the set of conceptual frameworks mentioned in the reviewed studies, the TPB [27] (Ajzen, 1991) was the most popular (32% across studies), followed by the VBN theory (ref. [28]; 11% across studies), and the Social Learning Theory (ref. [90]; 10% across studies). All other conceptual frameworks were used in only one, two, or three studies. Overall, around 25 other different conceptual frameworks were mentioned by the authors in their introduction, focusing on different concepts related to the correlates of interest (e.g., Hope theory for hope, Self-Determination theory for types of motivation, Theory of Generativity for generativity, and Coping theory for coping strategies). Finally, more than one conceptual framework was mentioned by the authors in 24% of the studies, whereas no theoretical framework was mentioned by the authors in 26% of the studies.

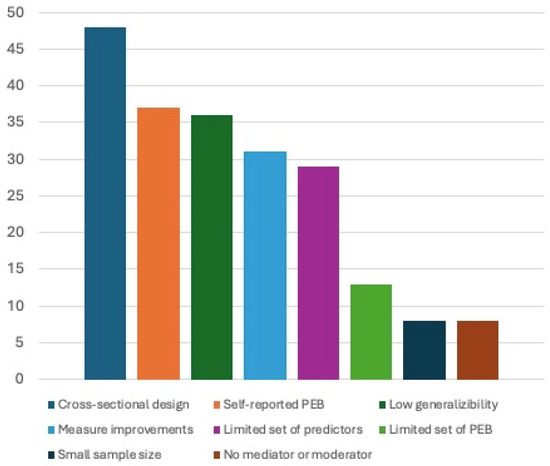

3.5. Gaps and Areas in Need of Future Research

We identified eight main gaps mentioned by the authors in the reviewed studies, which are presented in Figure 4. First, the use of a cross-sectional design was the most frequent study limitation mentioned by the authors (48% across studies). Second, the authors reported that PEB was self-reported and not measured by direct observation, underlying issues of social desirability (37% across studies). Third, they emphasized the low generalizability of their findings, indicating that their results only applied to a specific region or country or that their samples were not representative of the population under study (36% across studies). Fourth, some authors called for the need to improve their measures of various concepts in 31% of the studies (e.g., few items used for measuring the concept under study, use of unvalidated or homemade questionnaires). Fifth, they mentioned the examination of a limited set of predictors among their study limitations (29% across studies). The last three ones included the examination of a limited set of PEBs (13% across studies), the small sample size (8% across studies), and the absence of the examination of moderators and mediators (8% across studies). In addition, around 60% of the authors of the reviewed studies mentioned at least one other study limitation relating mostly to their specific study, such as not measuring the difficulty of PEB (i.e., some PEBs are more difficult to adopt than others, such as organizing a protest versus recycling; e.g., ref. [3]), using retrospective predictors (e.g., ref. [53]), sampling youths engaged in a program (e.g., ref. [10]), not differentiating between types of values (e.g., ref. [13]), not considering macrosystemic predictors such as social media (e.g., ref. [7]), attrition (e.g., ref. [36]), the need for experimental studies (e.g., ref. [63]), and the need to look at bidirectional associations (e.g., ref. [80]).

Figure 4.

Percentages of study limitations mentioned by the authors across studies.

4. Discussion

The primary goal of this scoping review was to identify predictors of PEB in adolescence. The secondary goals were to document what types of PEBs are usually assessed in adolescent samples, what are the main theoretical frameworks used, and what are the main limitations identified by the authors in this field of research to better capture the future directions. Following the review process, we identified five main considerations for the field.

First, very few studies were longitudinal. As a result, we decided to refer to “correlates” of PEB in adolescence and not “predictors”, since predictors entail that the variable comes before the PEB, thus increasing the probability of enacting it. This is a major issue since longitudinal studies are needed to disentangle the direction of the associations. For instance, an adolescent who watches environmental documentaries or decides to become vegan is more likely to feel connected with nature. This could also lead to a loop in which the adolescent will adopt more diversified PEB. Consequently, the association could go from connectedness with nature to PEB, but also the other way around, and become bidirectional over time. Only longitudinal studies can truly disentangle these scenarios. A further step of this field of research is thus to examine PEB over multiple years to portray the complex relationships between predictors and PEB during adolescence. Among the individual predictors, results from the seven studies with longitudinal data reveal that prior behavior [36,38,39], perceived behavioral control and intention [9,39], time spent outside in childhood [36], pro-environmental attitudes [10], habits and action planning [39], and climate change despair and denialism [40] predict PEB among adolescents. Among peer and family predictors, friends’ PEB [36], as well as mothers’ education and pro-environmental attitudes [37] also predict PEB among adolescents.

Second, correlates identified in the selected studies were very diversified, with around 50 different individual correlates, 20 different peer and family correlates, and 8 different school and community correlates. Overall, 42 correlates were not presented in detail in this scoping review given that they were investigated in only one or two studies (30 individual correlates, e.g., mothers’ political ideology, Five C’s of Positive Youth Development [PYD]), prosocial moral reasoning, climate change despair, news consumption, feeling of intergenerational obligation, life satisfaction, subjective wellbeing, and cognitive flexibility, and 12 peer and family correlates, e.g., parental autonomy support, parenting styles, parents’ climate change concern, and parents’ environmental identity; all correlates can be found in Table 1). On one hand, this diversity provides an overall overview of the relevant variables associated with PEB in adolescence. On the other hand, it becomes difficult to have a clear understanding of what are the essential variables in this field of research.

As revealed by this review, the most frequent sociodemographic and individual correlates include gender, age, perceived behavioral control, environmental literacy, pro-environmental attitudes, intention to adopt PEB, personal norms, connectedness with nature, and climate change concern. The most frequent peer and family correlates are parents’ PEB, communication with parents and friends about societal problems, and subjective and descriptive norms. The most frequent school and community correlate is engagement in green activities or environmental clubs at school or in the community.

There is also an imbalance between the study of individual correlates versus the study of other correlates in the peer and family, as well as the school and community spheres. Yet, a synergy is likely to take place in explaining why adolescents adopt PEB. For instance, adolescents with climate change concern are more likely to take action if opportunities, such as a school environmental club, are offered to them and if their parents and friends support such involvement. A further step of research is thus to consider different spheres of influence to better understand why adolescents adopt PEB. Among the 62 selected studies, only 17 (27%) examined two spheres [7,37,38,41,48,49,50,52,58,67,76,79,80,82,83,84,89] and only 4 (6%) examined the three spheres simultaneously [50,79,82,84].

Third, even though each type of PEB can make a difference, some are likely to make a bigger difference in the fight against climate change and require more efforts and initiative from adolescents. For instance, putting cardboard into the recycling bin at home is much easier than writing a letter to a government representative and will not have the same impact. Yet, these two behaviors are considered “equal” in studies on PEB’s correlates and are mixed in indexes of PEB. As a result, we know little about the predictors associated with more “difficult” PEB that could truly make a difference. Among exceptions, the findings by Wu and Otsuka [82] revealed that enjoying nature when younger, being a member of an environmental club, and experience with a severe natural disaster are associated with participatory actions in adolescence. Sarrasin et al. [75] also found that a sense of intergenerational obligation was linked to participatory actions among adolescents.

In addition, no difference is made between individual versus collective behaviors (e.g., turning off the lights when leaving the room versus taking part in a protest on environmental issues). Yet, in adolescence, collective behaviors might represent a more powerful experience given the importance of peers in this specific developmental period. Over the last five years, the rise of environmental youth movements such as “Fridays for future” and “Extinction rebellion” have given a collective voice and opportunities for adolescents who want to be involved in environmental causes. Further steps of research are thus to make a distinction between different types of behaviors, give more weight to behaviors more likely to make a difference, and differentiate between individual and collective behaviors.

Fourth, a very heterogeneous set of theoretical frameworks were identified in the 62 selected studies. For the most part, each study had its own theoretical framework. This is not a problem per se. However, it might help to develop a framework that embraces different perspectives and predictors in the individual, peer and family, and school and community spheres that are salient during the adolescent years. For instance, the TPB [27] is a central theoretical framework with a strong predictive capacity for PEB, and has been replicated in numerous studies, including meta-analyses (e.g., ref. [25]). Yet, this framework was not developed for adolescents and only include variables at the individual level (however, for a summary of extended versions of TPB, see [91]).

Given that adolescents are now facing the crisis of climate change, we believe that this is having an impact on the formation of their identity and personal norms and values. It also influences their comprehension of the world surrounding them, their emotion regulation, and their motivations. To add complexity, we believe that this occurs within the broader context of heightened peer influence (peer pressure, desire to please and popularity, and need to belong) and increased detachment from parents (questioning their values and advice), which are typical aspects of adolescence [92]. This is not to forget the omnipresence of social media that can send ambiguous messages about whether one should get involved in the fight against climate change or not (ref. [93], e.g., is it urgent or not, can I do something or not, is it “cool” or not?). If not already in place, we also believe that high schools will be encouraged more and more to integrate environmental education into their curriculum and establish environmental school clubs to support the ecological transition. Furthermore, in the coming years, social movements are likely to increasingly engage and mobilize adolescents [94]. A further step of research is thus to develop theoretical models that embrace this complexity in understanding why adolescents engage in PEB, which is crucial for intervention efforts.

Fifth, the review of the main limitations mentioned by the authors calls for a more rigorous study of PEB’s predictors in adolescence, whether in terms of design, measurement of the main concepts, or generalizability of the findings. This will enable researchers and practitioners to better understand the key predictors of adolescent PEB and identify the most robust factors to target in intervention.

Overall, future efforts may benefit from a large-scale, multisite longitudinal study using the same set of predictors, a unified theoretical model, and validated measurement tools across diverse countries including direct observations of PEB. This would significantly advance this field of research.

Study Limitations

Among the study limitations of this scoping review, first, only published peer-reviewed research articles written in English were included. Gray literature articles and other-language articles were not considered. Second, the first step of the screening process was based on titles and abstracts instead of full texts, due to a very high number of occurrences at the start of our search. As a result, we may have excluded relevant articles, such as qualitative studies that documented determinants of PEB even though it was not clear from the title and the abstract. Third, consistent with the parameters of a scoping review, we did not assess the methodological qualities of the selected studies and discuss the effect sizes of the associations between the correlates and adolescents’ PEB. Fourth, only direct associations were retrieved and reported in this scoping review. Some moderators and mediators have been studied in the selected studies (e.g., ref. [6,9,39,48,55,70,73,75,89], but were not considered. Nonetheless, drawing on a substantial body of research from various countries, this scoping review represents an initial effort to document and provide a global overview of predictors of adolescent PEB.

5. Conclusions

Due to the scarcity of longitudinal studies, robust conclusions regarding predictors of PEB among adolescents remain elusive. This review identified prevailing correlates that warrant further investigation, including pro-environmental attitudes, environmental knowledge, perceived behavioral control, personal norms, connectedness with nature, climate change concern, parents’ PEB, communication with parents and peers concerning societal issues, parents’ and peers’ descriptive norms, and engagement in school or community green activities. Nevertheless, it also highlighted significant limitations in the existing literature. This scoping review thus contributes to prior research by offering a new research agenda for researchers interested in factors and processes underlying PEB among adolescents. Identifying robust predictors of PEB in adolescence is crucial for understanding its driving factors and guiding future interventions. These predictors can inform the targets of interventions aimed at increasing PEB. To achieve this goal effectively, we need to develop a robust program theory or theory of change that practitioners could rely on.

For instance, based on our results, an intervention aimed at increasing PEB among adolescents should include a component with objectives and activities aligned with youths’ positive attitudes and connection with nature (e.g., walking in a forest, kayaking in a nearby river, planting trees and flowers, and growing vegetables), knowledge about core concepts of climate change and solutions to soothe their concerns (e.g., conferences by experts and key actors in the community), and empowerment (e.g., hands-on projects and workshops based on skill development such as decision-making and leadership). It should also include a family component in which parents are coached to discuss environmental issues with their children and encouraged to adopt pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Peers should also be part of the intervention, helping to foster positive social norms around involvement in environmental causes and acting as role models in their social networks. All these components could be implemented by schools, which should also provide various environmental activities and clubs for adolescents. Schools remain central to promoting and disseminating a universal culture of sustainable development and lifestyle among future generations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/su16135383/s1, S1—Preferred Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) Checklist (Tricco et al., 2018 [35]); S2—List of keywords and search strategy for each database; S3—Flowchart for the identification of studies from 15 August 2022 to 16 February 2024; and S4—Data extraction tool.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.-S.D.; methodology, A.-S.D. and M.D.L.; formal analysis, A.-S.D., M.B. and J.P.; investigation, A.-S.D., M.B., J.P. and M.D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.-S.D.; writing—review and editing, F.P. and V.D.; funding acquisition, A.-S.D., F.P., V.D. and I.A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada, grant number 430-2022-00291.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. 2022. Available online: https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg2/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf (accessed on 30 April 2024).

- Hickman, C.; Marks, E.; Pihkala, P.; Clayton, S.; Lewandowski, E.; Mayall, E.E.; Wray, B.; Mellor, C.; van Susteren, L. Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. Lancet Planet. Health 2021, 5, e863–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G.; Truskauskaitė-Kunevičienė, I. Sustainability in youth: Environmental considerations in adolescence and their relationship to pro-environmental behavior. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 582920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poškus, M.S. What works for whom? Investigating adolescents’ pro-environmental behaviors. Sustainability 2020, 12, 7313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. World Youth Report: Youth and Climate Change. 2010. Available online: https://www.un.org/development/desa/youth/world-youth-report/world-youth-report-2010.html (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Uitto, A.; Boeve-de Pauw, J.; Saloranta, S. Participatory school experiences as facilitators for adolescents’ ecological behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 55–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collado, S.; Staats, H.; Sancho, P. Normative influences on adolescents’ self-reported pro-environmental behaviors: The role of parents and friends. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 288–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray-Lake, L.; Flanagan, C.A.; Osgood, D.W. Examining trends in adolescent environmental attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors across three decades. Environ. Behav. 2010, 42, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Leeuw, A.; Valois, P.; Ajzen, I.; Schmidt, P. Using the theory of planned behavior to identify key beliefs underlying pro-environmental behavior in high-school students: Implications for educational interventions. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 128–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, J.; Blood, N.; Beery, T. Environmental action and student environmental leaders: Exploring the influence of environmental attitudes, locus of control, and sense of personal responsibility. Environ. Educ. Res. 2017, 23, 149–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/2030agenda (accessed on 3 June 2024).

- Anderson, D.J.; Krettenauer, T. Connectedness to nature and pro-environmental behaviour from early adolescence to adulthood: A comparison of urban and rural Canada. Sustainability 2021, 13, 3655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, S.; Gatarić, D.; Prnjat, Z.; Andjelković, G.; Jovanović, J.M.; Lukić, B.; Lutovac, M.D. Exploring proenvironmental behavior of Serbian youth through environmental values, satisfaction, and responsibility. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2016, 44, 1057–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association. APA Dictionary Of Psychology–Adolescence. Available online: https://dictionary.apa.org/adolescence (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- World Health Organization. Adolescent Health. Available online: https://www.who.int/health-topics/adolescent-health#tab=tab_1 (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- DeVille, N.V.; Powers Tomasso, L.; Stoddard, O.P.; Wilt, G.E.; Horton, T.H.; Wolf, K.L.; Brymer, E.; Kahn, P.H.; James, P. Time spent in nature is associated with increased pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 7498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mackay, C.M.L.; Schmitt, M.T. Do people who feel connected to nature do more to protect it? A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 65, 101323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitburn, J.; Linklater, W.; Abrahamse, W. Meta-analysis of human connection to nature and proenvironmental behavior. Conserv. Biol. 2020, 34, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurst, M.; Dittmar, H.; Bond, R.; Kasser, T. The relationship between materialistic values and environmental attitudes and behaviors: A meta-analysis. J. Environ. Psychol. 2013, 36, 257–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, K.S. From prediction to process: A self-regulation account of environmental behavior change. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 51, 189–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipley, N.J.; van Riper, C.J. Pride and guilt predict pro-environmental behavior: A meta-analysis of correlational and experimental evidence. J. Environ. Psychol. 2022, 79, 101753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soutter, A.R.B.; Bates, T.C.; Mõttus, R. Big five and HEXACO personality traits, proenvironmental attitudes, and behaviors: A meta-analysis. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 913–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udall, A.M.; de Groot, J.M.; De Jong, S.B.; Shankar, A. How I see me—A meta-analysis investigating the association between identities and pro-environmental behaviour. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 582421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R.; Nilsson, A. Personal and social factors that influence pro-environmental concern and behaviour: A review. Int. J. Psychol. 2014, 49, 141–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klöckner, C.A. A comprehensive model of the psychology of environmental behaviour—A meta-analysis. Glob. Environ. Chang. 2013, 23, 1028–1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ma, S.; Zhao, L.; Shao, S.; Zhang, L. What influences an individual’s pro-environmental behavior? A literature review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2019, 146, 28–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. 1991, 50, 179–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, P. Toward a coherent theory of environmentally significant behavior. J. Soc. Issues 2000, 56, 407–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuba, M.K.; Alisat, S.; Pratt, M.W. Environmental activism in emerging adulthood. In Flourishing in Emerging Adulthood: Positive Development during the Third Decade of Life; Padilla-Walker, L.M., Nelson, L.J., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 175–201. [Google Scholar]

- Riemer, M.; Dittmer, L. An introduction to the Special Issue. Ecopsychology 2016, 8, 163–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munn, Z.; Peters, M.D.J.; Stern, C.; Tufanaru, C.; McArthur, A.; Aromataris, E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2018, 18, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Method 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devault-Tousignant, C.; Lavoie, N.; Audette-Chapdelaine, S.; Auger, A.-M.; Côté, M.; Cotton, J.-C.; Brodeur, M. Gambling among LGBTQIA2S+ populations: A scoping review. Addict. Res. Theory 2023, 31, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. Prisma extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, J.; Harré, N.; Atkinson, Q.D. Understanding change in recycling and littering behavior across a school social network. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 2014, 53, 462–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, G.W.; Otto, S.; Kaiser, F.G. Childhood origins of young adult environmental behavior. Psychol. Sci. 2018, 29, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, A.; Vandenbosch, L.; Rousseau, A. A panel study of the relationships between social media interactions and adolescents’ pro-environmental cognitions and behaviors. Environ. Behav. 2023, 55, 399–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pakpour, A.H.; Lin, C.-K.; Safdari, M.; Lin, C.-Y.; Chen, S.-H.; Hamilton, K.; Han, H.; Tchounwou, P.B. Using an integrated social cognition model to explain green purchasing behavior among adolescents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 12663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veijonaho, S.; Ojala, M.; Hietajärvi, L.; Salmela-Aro, K. Profiles of climate change distress and climate denialism during adolescence: A two-cohort longitudinal study. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 2023, 48, 103–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Why young people do things for the environment: The role of parenting for adolescents’ motivation to engage in pro-environmental behaviour. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 11–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, A.; Ahmad, A.; Khan, M.N. Examining the role of consumer lifestyles on ecological behavior among young Indian consumers. Young Consum. 2017, 18, 348–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ari, E.; Yılmaz, V. Effects of environmental illiteracy and environmental awareness among middle school students on environmental behavior. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2017, 19, 1779–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aruta, J.J.B.R. Science literacy promotes energy conservation behaviors in Filipino youth via climate change knowledge efficacy: Evidence from PISA 2018. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2022, 39, 55–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balundė, A.; Perlaviciute, G. Are we on the same page? Exploring the relationships between environmental values, self-identity, personal norms and behavior in parent-adolescent dyads. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 92, 102157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barata, R.; Castro, P. “I feel recycling matters… sometimes”: The negative influence of ambivalence on waste separation among teenagers. Soc. Sci. J. 2013, 50, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bøhlerengen, M.; Wiium, N. Environmental attitudes, behaviors, and responsibility perceptions among Norwegian youth: Associations with positive youth development indicators. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 844324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Busch, K.C.; Ardoin, N.; Gruehn, D.; Stevenson, K. Exploring a theoretical model of climate change action for youth. Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2019, 41, 2389–2409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fielding, K.S.; Head, B.W. Determinants of young Australians’ environmental actions: The role of responsibility attributions, locus of control, knowledge and attitudes. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 171–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, D.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Q. Motivating sustainable consumption among chinese adolescents: An empirical examination. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, R.K.; Krymkowski, D.H.; Ardoin, N.M.; Lepczyk, C.A. The importance of culture in predicting environmental behavior in middle school students on Hawai’i island. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0207087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grønhøj, A.; Thøgersen, J. Action speaks louder than words: The effect of personal attitudes and family norms on adolescents’ pro-environmental behaviour. J. Econ. Psychol. 2012, 33, 292–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoover, K.S. Children in nature: Exploring the relationship between childhood outdoor experience and environmental stewardship. Environ. Educ. Res. 2021, 27, 894–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, H.; Madjar, N. Autonomous motivation and pro-environmental behaviours among Bedouin students in Israel: A self-determination theory perspective. Aust. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 31, 223–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerret, D.; Orkibi, H.; Ronen, T. Testing a model linking environmental hope and self-control with students’ positive emotions and environmental behavior. J. Environ. Educ. 2016, 47, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krettenauer, T. Pro-environmental behavior and adolescent moral development. J. Res. Adolesc. 2017, 27, 581–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krettenauer, T.; Wang, W.; Jia, F.; Yao, Y. Connectedness with nature and the decline of pro-environmental behavior in adolescence: A comparison of Canada and China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2020, 71, 101348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawson, D.F.; Stevenson, K.T.; Peterson, M.N.; Carrier, S.J.; Seekamp, E.; Strnad, R. Evaluating climate change behaviors and concern in the family context. Environ. Educ. Res. 2019, 25, 678–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Liu, C. Intergenerational influence on adolescents’ proenvironmental behavior. Soc. Behav. Personal. 2016, 44, 589–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metzger, A.; Alvis, L.M.; Oosterhoff, B.; Babskie, E.; Syvertsen, A.; Wray-Lake, L. The intersection of emotional and sociocognitive competencies with civic engagement in middle childhood and adolescence. J. Youth Adolesc. 2018, 47, 1663–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mónus, F. Environmental education policy of schools and socioeconomic background affect environmental attitudes and pro-environmental behavior of secondary school students. Environ. Educ. Res. 2022, 28, 169–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neaman, A.; Montero, E.; Pensini, P.; Burnham, E.; Castro, M.; Ermakov, D.S.; Navarro-Villarroel, C. Unleashing the power of connection: How adolescents’ prosocial propensity drives ecological and altruistic behaviours. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. How do children cope with global climate change? Coping strategies, engagement, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2012, 32, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope and climate change: The importance of hope for environmental engagement among young people. Environ. Educ. Res. 2012, 18, 625–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Coping with climate change among adolescents: Implications for subjective well-being and environmental engagement. Sustainability 2013, 5, 2191–2209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M. Hope in the face of climate change: Associations with environmental engagement and student perceptions of teachers’ emotion communication style and future orientation. J. Environ. Educ. 2015, 46, 133–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojala, M.; Bengtsson, H. Young people’s coping strategies concerning climate change: Relations to perceived communication with parents and friends and proenvironmental behavior. Environ. Behav. 2019, 51, 907–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Östman, J. The influence of media use on environmental engagement: A political socialization approach. Environ. Commun. 2014, 8, 92–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pickering, G.J.; Schoen, K.; Botta, M. Lifestyle decisions and climate mitigation: Current action and behavioural intent of youth. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Chang. 2021, 26, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poškus, M.S.; Žukauskienė, R. Predicting adolescents’ recycling behavior among different big five personality types. J. Environ. Psychol. 2017, 54, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prabawani, B.; Hadi, S.P.; Zen, I.S.; Afrizal, T.; Purbawati, D. Education for sustainable development as diffusion of innovation of secondary school students. J. Teach. Educ. Sustain. 2020, 22, 84–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratt, M.W.; Norris, J.E.; Alisat, S.; Bisson, E. Earth mothers (and fathers): Examining generativity and environmental concerns in adolescents and their parents. J. Moral Educ. 2013, 42, 12–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, A.C.; Downey, L.A.; Ford, T.C.; Lomas, J.E.; Stough, C. Green teens: Investigating the role of emotional intelligence in adolescent environmentalism. Pers. Indiv. Differ. 2019, 138, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Runhaar, P.; Wagenaar, K.; Wesselink, R.; Runhaar, H. Encouraging students’ pro-environmental behaviour: Examining the interplay between student characteristics and the situational strength of schools. J. Educ. Sustain. Dev. 2019, 13, 45–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarrasin, O.; Crettaz von Roten, F.; Butera, F. Who’s to act? Perceptions of intergenerational obligation and pro-environmental behaviours among youth. Sustainability 2022, 14, 1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K.T.; Peterson, M.N.; Carrier, S.J.; Strnad, R.L.; Bondell, H.D.; Kirby-Hathaway, T.; Moore, S.E. Role of significant life experiences in building environmental knowledge and behavior among middle school students. J. Environ. Educ. 2014, 45, 163–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevenson, K.; Peterson, N. Motivating action through fostering climate change hope and concern and avoiding despair among adolescents. Sustainability 2016, 8, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Lu, X.; Cui, J.; Du, K.; Xie, S. Effects of vicarious experiences of nature, environmental beliefs, and attitudes on adolescents’ environmental behavior. Environ. Educ. Res. 2023, 30, 926–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez, R.; Peterson, M.N.; Stevenson, K.T. How communication with teachers, family and friends contributes to predicting climate change behaviour among adolescents. Environ. Conserv. 2018, 45, 183–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallis, H.; Klöckner, C. The transmission of energy-saving behaviors in the family: A multilevel approach to the assessment of aggregated and single energy-saving actions of parents and adolescents. Environ. Behav. 2020, 52, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wullenkord, M.C.; Ojala, M. Climate-change worry among two cohorts of late adolescents: Exploring macro and micro worries, coping, and relations to climate engagement, pessimism, and well-being. J. Environ. Psychol. 2023, 90, 102093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Otsuka, Y. Pro-climate behaviour and the influence of learning sources on it in Chinese adolescents. Int. Res. Geogr. Environ. Educ. 2021, 30, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, W.; Li, L.M.W. Multilevel evidence for the parent-adolescent dyadic effect of familiarity with climate change on pro-environmental behaviors in 14 societies: Moderating effects of societal power distance and individualism. Environ. Behav. 2022, 54, 1097–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, J.; Liu, L.; Hao, M.; Morse, S. The waste separation behaviour of primary and middle school students and its influencing factors: Evidence from Yingtan city, China. Environ. Res. Commun. 2023, 5, 045002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Y. Can adolescents’ subjective wellbeing facilitate their pro-environmental consumption behaviors? Empirical study based on 15-year-old students. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1184605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Zhang, W.; Shi, Y. Are happier adolescents more willing to protect the environment? Empirical evidence from Programme for International Student Assessment 2018. Front. Psychol. 2023, 14, 1157409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, W. A cross-cultural perspective on adolescents’ cognitive flexibility and pro-environmental behavior: Multilevel evidence. Curr. Psychol. 2022, 43, 14686–14694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zecha, S. Significant influences on nature experiences: A comparative study of southern German and northern Spanish pupils aged 14-15. Discourse Commun. Sustain. Educ. 2015, 4, 23–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Žukauskienė, R.; Truskauskaitė-Kunevičienė, I.; Gabė, V.; Kaniušonytė, G. “My words matter”: The role of adolescents in changing pro-environmental habits in the family. Environ. Behav. 2021, 53, 1140–1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Yuriev, A.; Dahmen, M.; Paillé, P.; Boiral, O.; Guillaumie, L. Pro-environmental behaviors through the lens of the Theory of Planned Behavior: A scoping review. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2020, 155, 104660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steinberg, L.D. Adolescence; McGraw-Hill Education: New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Hautea, S.; Parks, P.; Takahashi, B.; Zeng, J. Showing they care (or don’t): Affective publics and ambivalent climate activism on TikTok. Soc. Media Soc. 2021, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cebul, M.D. Youth Activism: Balancing Risk and Reward. 2023. Available online: https://www.usip.org/publications/2023/01/youth-activism-balancing-risk-and-reward (accessed on 6 February 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).