The Impact of the Wellness Tourism Experience on Tourist Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Tourist Satisfaction

Abstract

1. Introduction

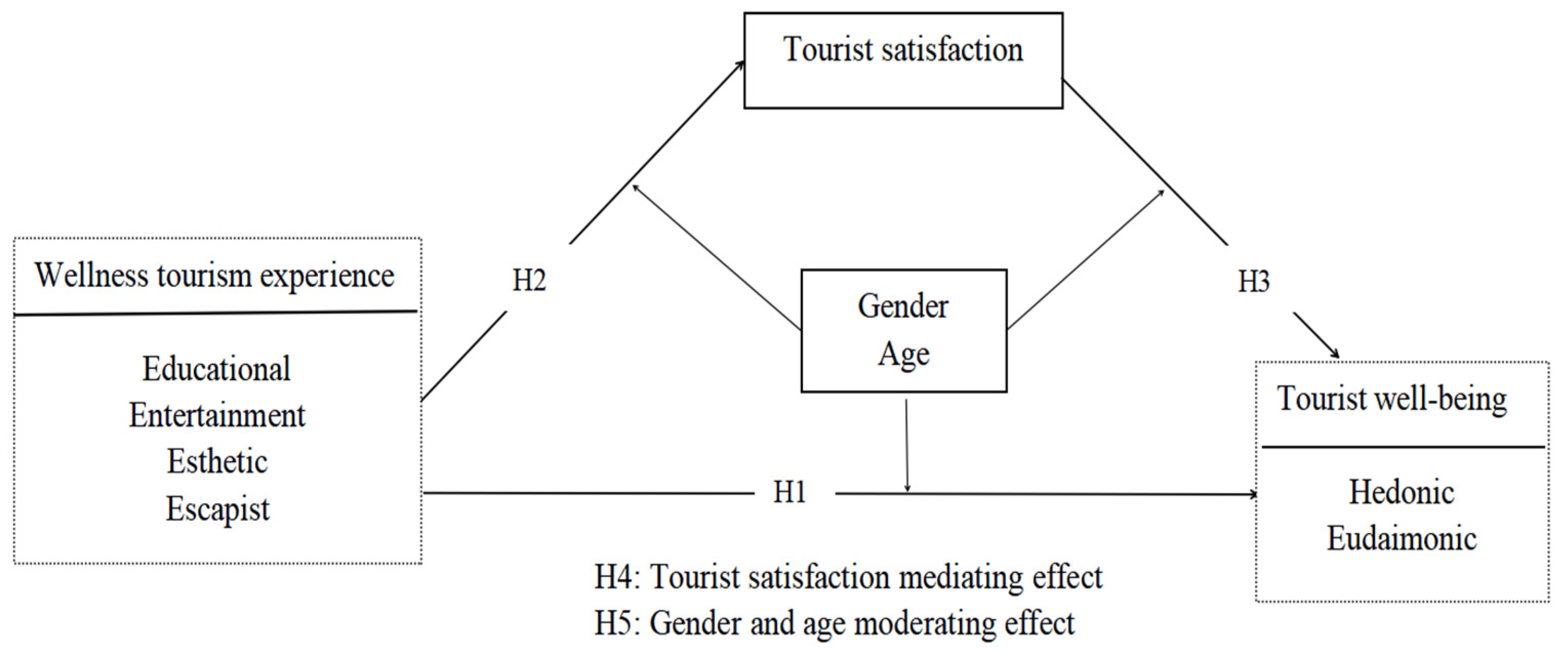

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Bottom-Up Spillover Theory

2.2. Wellness Tourism Experience and Tourist Well-Being

2.3. Tourist Satisfaction

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Gender and Age

3. Methodology

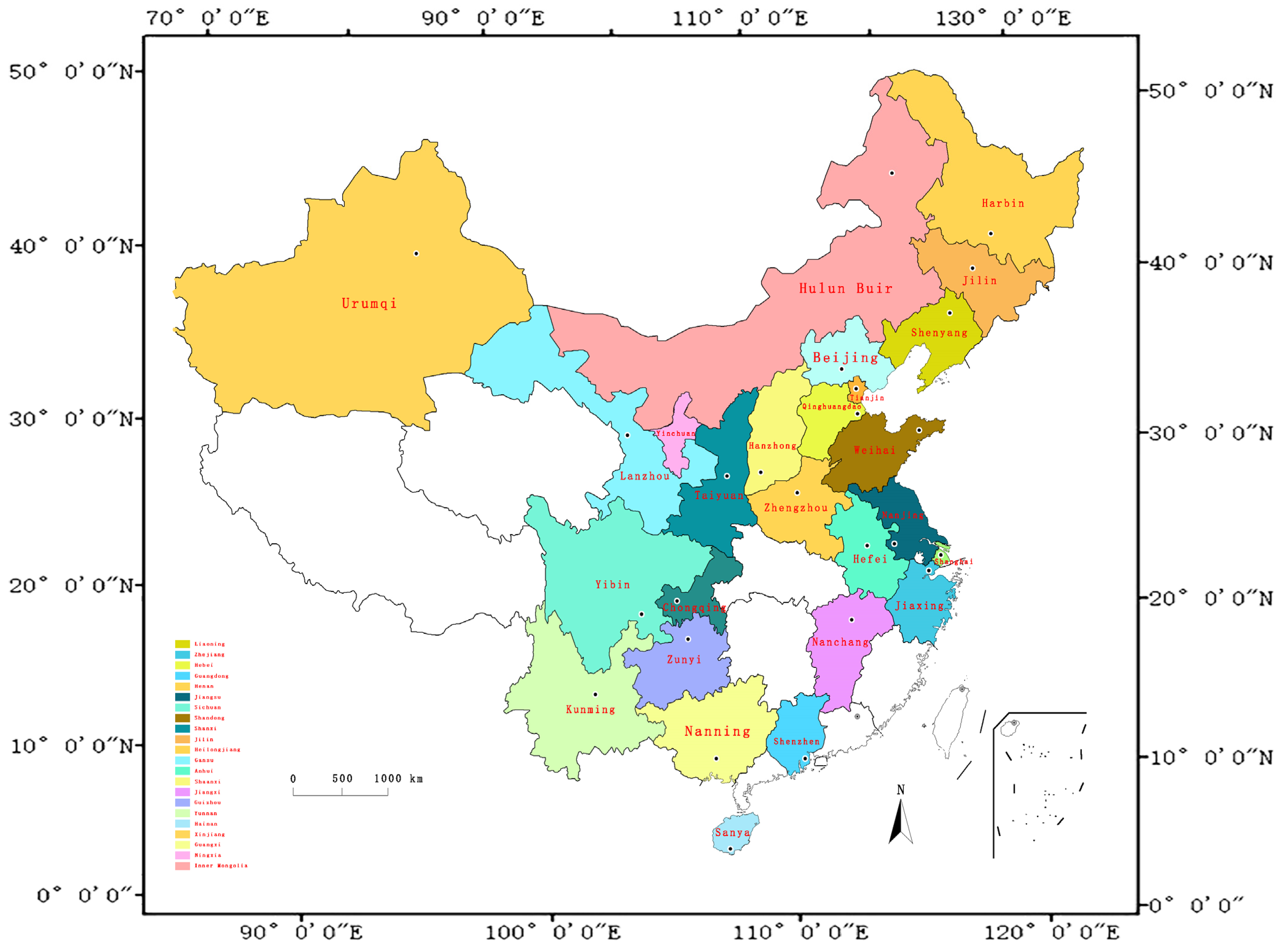

3.1. Sample and Data Collection

3.2. Measures

4. Results

4.1. Confirmatory Factor Analysis

4.2. Path Analysis and Hypotheses Testing

4.2.1. Path Analysis

4.2.2. Mediating Effect Analysis

4.2.3. Moderating Effect Analysis

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Main Conclusions

6.2. Theoretical Implications

6.3. Practical Implications

6.4. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Voigt, C.; Pforr, C. Wellness Tourism: A Destination Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhai, C.; Gao, H.; Chen, M.; Wang, J. Effect of moxibustion on the nailfold microcirculation of young and middle-aged people in sub-health status. World J. Acupunct. Moxib. 2017, 27, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno-González, A.A.; León, C.J.; Fernández-Hernández, C. Health destination image: The influence of public health management and well-being conditions. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2020, 16, 100430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, I.D.; Ainsworth, G.B.; Crowley, J. Transformative travel as a sustainable market niche for protected areas: A new development, marketing and conservation model. J. Sustain. Tour. 2017, 25, 1650–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chrysikou, E.; Tziraki, C.; Buhalis, D. Architectural hybrids for living across the lifespan: Lessons from dementia. Serv. Ind. J. 2018, 38, 4–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakov, S.; Oyner, O. Wellness tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 58–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wellness Institute (GWI). The Global Wellness Economy: Country Rankings Report; Global Wellness Institute (GWI): Miami, FL, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Dillette, A.K.; Douglas, A.C.; Andrzejewski, C. Dimensions of holistic wellness as a result of international wellness tourism experiences. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 24, 794–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Wellness Institute (GWI). The Global Wellness Tourism Economy Report; Global Wellness Institute (GWI): Miami, FL, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Florido-Benítez, L. The impact of tourism promotion in tourist destinations: A bibliometric study. Int. J. Tour. Cities 2022, 8, 844–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hook, H.; De Vos, J.; Van Ackler, V.; Witlox, F. A comparative analysis of determinants, characteristics, and experiences of four daily trip types. Travel Behav. Soc. 2023, 30, 335–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, M.K.; Diekmann, A. Tourism and well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2017, 66, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kan, T.; Ku, E.; Sun, W.; Lai, T.; Hsu, P.; Hsu, S. Wellness tourism enhances elderly life satisfaction. J. Qual. Assur. Hosp. Tour. 2022, 21, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sthapit, E.; Coudounaris, D.N. Memorable tourism experiences: Antecedents and outcomes. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2018, 18, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dekhili, S.; Hallem, Y. An examination of the relationship between co-creation and well-being: An application in the case of tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, V.W.; Ritchie, J.B. Exploring the essence of memorable tourism experiences. Ann. Tour. Res. 2011, 38, 1367–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Lyu, S.O. The antecedents and consequences of well-being perception: An application of the experience economy to golf tournament tourists. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2015, 4, 248–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartwell, H.; Fyall, A.; Willis, C.; Page, S.; Ladkin, A.; Hemingway, A. Progress in tourism and destination wellbeing research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2018, 21, 1830–1892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, J.; Back, K.J. Cruise brand experience: Functional and wellness value creation in tourism business. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2019, 31, 2205–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton, R.N.; Gustafsson, A.; McColl-Kennedy, J.; Sirianni, N.J.; David, K.T. Small details that make big differences: A radical approach to consumption experience as a firm’s differentiating strategy. J. Serv. Manag. 2014, 25, 253–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Channeling life satisfaction to tourist satisfaction: New conceptualization and evidence. J. China Tour. Res. 2019, 16, 566–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabor, M.R.; Oltean, F.D. Babymoon tourism between emotional well-being service for medical tourism and niche tourism. Development and awareness on Romanian educated women. Tour. Manag. 2019, 70, 170–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Fu, X.; Cai, L.A.; Lu, L. Destination image and tourist loyalty: A meta-analysis. Tour. Manag. 2014, 40, 213–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, W.; Jeong, C. Distinctive roles of tourist eudaimonic and hedonic experiences on satisfaction and place attachment: Combined use of SEM and necessary condition analysis. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2021, 47, 58–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilbert, D.; Abdullah, J. Holiday taking and the sense of well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2004, 31, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Ahn, D. Seeking pleasure or meaning? The different impacts of hedonic and eudaimonic tourism happiness on tourists’ life satisfaction. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neal, J.D.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M.J. The effect of tourism services on travelers’ quality of life. J. Travel. Res. 2007, 46, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Kiatkawsin, K.; Jung, H.; Kim, W. The role of wellness spa tourism performance in building destination loyalty: The case of Thailand. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 595–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Arcodia, C.; Kim, I. Critical success factors of medical tourism: The case of South Korea. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2019, 16, 4964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.P.; Chang, W.C.; Ramanpong, J. Assessing visitors’ memorable tourism experiences (MTEs) in forest recreation destination: A case study in Xitou nature education area. Forests 2019, 10, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Wang, W.; Du, J. An integrative review of patients’ experience in the medical tourism. J. Health Care 2020, 57, 0046958020926762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pinos-Navarrete, A.; Abarca-Álvarez, F.J.; Maroto-Martos, J.C. Perceptions and profiles of young people regarding spa tourism: A comparative study of students from Granada and Aachen universities. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Tang, B.; Nawijn, J. Eudaimonic and hedonic well-being pattern changes: Intensity and activity. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 84, 103008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Tang, B.; Nawijn, J. How tourism activity shapes travel experience sharing: Tourist well-being and social context. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higham, J. Sport tourism: A perspective article. Tour. Rev. 2020, 76, 64–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ažić, M.L.; Suštar, N. Loyalty to holiday style: Motivational determinants. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 239–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hung, H.K.; Wu, C.C. Effect of adventure tourism activities on subjective well-being. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 91, 103147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazakova, A.; Kim, I. Tourists’ pro-environmental behavior decision-making process: Application of norm activation model (NAM) and moderating effect of age. Korean J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 29, 79–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Cheng, J.; Swanson, S. The companion effect on adventure tourists’ satisfaction and subjective well-being: The moderating role of gender. Tour. Rev. 2022, 77, 897–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiese, C.W.; Kuykendall, L.; Tay, L. Get active? A meta-analysis of leisure-time physical activity and subjective well-being. J. Posit. Psychol. 2018, 13, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, C.; Omar, H.; Rashid-Radha, J. The impact of tourist attractions and accessibility on tourists’ satisfaction: The moderating role of tourists’ age. Geo. J. Tour. 2020, 32, 1202–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marín-García, A.; Gil-Saura, I.; Ruiz-Molina, M.E.; Berenguer-Contrí, G. Sustainability, store equity, and satisfaction: The moderating effect of gender in retailing. Sustainability 2021, 13, 1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Kim, Y.G.; Woo, E. Examining the impacts of touristification on quality of life (QOL): The application of the bottom-up spillover theory. Serv. Ind. J. 2021, 41, 787–802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagan, R. Sport participation, life satisfaction and domains of satisfaction among people with disabilities. Appl. Res. Qual. Life 2020, 15, 893–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Efraty, D.; Siegel, P.; Lee, D.J. A new measure of quality of work life (QWL) based on need satisfaction and spillover theories. Soc. Indic. Res. 2001, 55, 241–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, H.J. Effect of chief executive officer’s sustainable leadership styles on organization members’ psychological well-Being and organizational citizenship behavior. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sirgy, M. Promoting quality-of-life and well-being research in hospitality and tourism. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2019, 36, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Pan, L.; Wen, J.; Phau, I. Effects of tourism experiences on tourists’ subjective well-being through recollection and storytelling. J. Vacat. Mark. 2022, 13, 13567667221101414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nawijn, J. The holiday happiness curve: A preliminary investigation into mood during a holiday abroad. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2010, 12, 281–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alipour, H.; Rezapouraghdam, H.; Esmaeili, B. Public health and tourism; a personalist approach to community well-being: A narrative review. Iran. J. Public Health 2020, 49, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Swanson, S.R.; Chen, X. Reputation, subjective well-being, and environmental responsibility: The role of satisfaction and identification. J. Sustain. Tour. 2018, 26, 1344–1361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Su, L.; Swanson, S.R. The service quality to subjective well-being of Chinese tourists connection: A model with replications. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 2076–2092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, Y.J.; Kim, H.K.; Lee, T.J. Visitor motivational factors and level of satisfaction in wellness tourism: Comparison between first-time visitors and repeat visitors. Asia Pac. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 21, 137–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberato, D.; Brandão, F.; Teixeira, A.S.; Liberato, P. Satisfaction and loyalty evaluation towards health and wellness destination. J. Tour. Dev. 2021, 2, 9–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, N.; Min, S. Research on satisfaction, happiness, scenic attractions in the perspective of travelers visiting intangible cultural heritage sight: A study based on Huangshan city. J. Huangshan Univ. 2019, 21, 26–29. [Google Scholar]

- Sirgy, M.J.; Kruger, P.; Lee, D.J.; Yu, G.B. How does a travel trip affect tourists’ life satisfaction? J. Travel Res. 2011, 50, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Romão, J. Tourism dynamics and regional sustainable development. In Tourism, Territory and Sustainable Development; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10, pp. 95–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Cheng, C.; Ai, C. A study of experiential quality, experiential value, trust, corporate reputation, experiential satisfaction and behavioral intentions for cruise tourists: The case of Hong Kong. Tour. Manag. 2018, 66, 200–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Wei, W.; Wen, J.; Ying, T.; Tan, X. Creating memorable experience in rural tourism: A comparison between domestic and outbound tourists. J. Travel Res. 2021, 60, 1527–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Lanlung, C.; Kim, E.; Tang, L.R.; Song, S.M. Towards quality of life: The effects of the wellness tourism experience. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2018, 35, 410–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Liu, B.; Li, Y. Recovery experience of wellness tourism and place attachment: Insights from feelings-as-information theory. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2022, 34, 2934–2952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Yang, X.; Fu, S.; Huan, T. Exploring the influence of tourists’ happiness on revisit intention in the context of Traditional Chinese Medicine cultural tourism. Tour. Manag. 2023, 94, 104647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devesa, M.; Laguna, M.; Palacios, A. The role of motivation in visitor satisfaction: Empirical evidence in rural tourism. Tour. Manag. 2010, 31, 547–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S. Moving beyond subjective well-being: A tourism critique. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2012, 38, 266–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jew, J. Links between Cultural Heritage Tourism and Overall Sense of Tourist Well-Being. Ph.D. Thesis, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pyke, S.; Hartwell, H.; Blake, A.; Hemingway, A. Exploring well-being as a tourism product resource. Tour. Manag. 2016, 55, 94–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filep, S.; Laing, J. Trends and directions in tourism and positive psychology. J. Travel Res. 2019, 58, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Lee, S.; Uysal, M.; Kim, J.; Ahn, K. Nature-based tourism: Motivation and subjective well-being. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 76–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogt, C.; Jordan, E.; Grewe, N.; Kruger, L. Collaborative tourism planning and subjective well-being in a small island destination. J. Destin. Mark. Manag. 2016, 5, 36–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, F.; Xiao, H. Residential tourism and eudaimonic well-being: A ‘value-adding’ analysis. Ann. Tour. Res. 2021, 87, 103150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vada, S.; Prentice, C.; Hsiao, A. The influence of tourism experience and well-being on place attachment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2019, 47, 322–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grubb, E.L.; Grathwohl, H.L. Consumer self-concept, symbolism and market behavior: A theoretical approach. J. Mark. 1967, 31, 22–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.; Kim, J.J.; Choe, Y.; Hyun, S.; Kim, I. Modeling the role of luxury air-travelers’ self-enhancement. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2020, 37, 200–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, D.; Kruger, S.; Whang, M.; Uysal, M.; Sirgy, M. Validating a customer well-being index related to natural wildlife tourism. Tour. Manag. 2014, 45, 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Elliott, F.; Oates, L.; Schembri, A.; Mantri, N. Do wellness tourists get well? An observational study of multiple dimensions of health and well-being after a week-long retreat. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 2017, 23, 140–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, V.; Machado, J.; Marques, O.; Nunes, J. Mixed feelings? Fluctuations in well-being during tourist travels. Serv. Ind. J. 2020, 40, 158–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitas, O.; Kroesen, M. Vacations over the years: A cross-lagged panel analysis of tourism experiences and subjective well-being in the Netherlands. J. Happiness Stud. 2020, 21, 2807–2826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Park, B.; Tsunetsugu, Y.; Ohira, T.; Kagawa, T.; Miyazaki, Y. Effect of forest bathing on physiological and psychological responses in young Japanese male subjects. Public Health 2011, 125, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohe, Y.; Ikei, H.; Song, C.; Miyazaki, Y. Evaluating the relaxation effects of emerging forest-therapy tourism: A multidisciplinary approach. Tour. Manag. 2017, 62, 322–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Li, Y.; Kralj, A.; Moyle, B.; He, M. Inspiration and wellness tourism: The role of cognitive appraisal. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2022, 39, 173–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliver, R.L. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective on the Consumer; Taylor and Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pizam, A.; Neumann, Y.; Reichel, A. Dimentions of tourist satisfaction with a destination area. Ann. Tour. Res. 1978, 5, 314–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, L.; Tian, Z.; Koh, J. Tourist satisfaction enhancement using mobile QR code payment: An empirical investigation. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias, O.; Markovic, S.; Rialp, J. How does sensory brand experience influence brand equity? Considering the roles of customer satisfaction, customer affective commitment, and employee empathy. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 96, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phakdeephirot, N. Tourists’ satisfaction with products, services and quality development of hot spring wellness tourism. J. Creat. Entrep. Manag. 2021, 2, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backman, S.; Huang, Y.; Chen, C.; Lee, H.; Cheng, J. Engaging with restorative environments in wellness tourism. Curr. Issues Tour. 2022, 2, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Liu, B.; Li, Y. Tourist inspiration: How the wellness tourism experience inspires tourist engagement. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2021, 24, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtarian, P.L.; Pendyala, R.M. Travel Satisfaction and Well-Being; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 34, pp. 17–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vada, S.K. The Tourist Perspective: Examining the Effects of Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-Being in Tourism. Ph.D. Thesis, Griffith University, Queensland, Australia, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmaki, A.; Stergiou, D.P. Escaping loneliness through Airbnb host-guest interactions. Tour. Manag. 2019, 74, 331–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Cottam, E.; Lin, Z. The effect of resident-tourist value co-creation on residents’ well-being. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 44, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, L.; Huang, S.; Chen, X. Effects of service fairness and service quality on tourists’ behavioral intentions and subjective well-being. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2015, 32, 290–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biswas, C.; Deb, S.; Hasan, A.; Khandakar, M. Mediating effect of tourists’ emotional involvement on the relationship between destination attributes and tourist satisfaction. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 4, 490–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jebbouri, A.; Zhang, H.; Imran, Z.; Iqbal, J.; Bouchiba, N. Impact of destination image formation on tourist trust: Mediating role of tourist satisfaction. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 845538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, W.; Lee, C.; Reisinger, Y. Behavioral intentions of international visitors to the Korean hanok guest houses: Quality, value and satisfaction. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 47, 83–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, L.; Chi, C.G.; Liu, Y. Authenticity, involvement, and image: Evaluating tourist experiences at historic districts. Tour. Manag. 2015, 50, 85–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bosque, I.R.; San Martín, H. Tourist satisfaction a cognitive-affective model. Ann. Tour. Res. 2008, 35, 551–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Hwang, J.; Kim, I. Congruent charitable cause sponsorship effect: Air travelers’ perceived benefits, satisfaction and behavioral intention. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2020, 42, 190–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Lu, L.; Gursoy, D. Traveling to a gendered destination: A goal-framed advertising perspective. J. Hosp. Tour. Res. 2020, 44, 499–522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo, R.R.; León, C.J.; Carballo, M.M. Gender as moderator of the influence of tourists’ risk perception on destination image and visit intentions. Tour. Rev. 2021, 77, 913–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, I.; Kim, J.J. Emotional attachment, age and online travel community behaviour: The role of parasocial interaction. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 3466–3488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, W.H.; Cho, J.; Kim, K.S. The relationships of wine promotion, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intention: The moderating roles of customers’ gender and age. J. Hosp. Tour. Manag. 2019, 39, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, L.; Lu, L.; Zhang, T. Destination gender: Scale development and cross-cultural validation. Tour. Manag. 2021, 83, 104225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Florido-Benítez, L. The influence of demographic and situational characteristics in satisfaction and decision of tourism activities via mobile marketing. Cuad. Tur. 2016, 38, 143–165. [Google Scholar]

- Estelami, H.; Nejad, M.G. The role of cognitive and demographic profile of future managers on product elimination decisions. J. Res. Mark. Entrep. 2022, 24, 365–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karande, K.; Magnini, V.P.; Tam, L. Recovery voice and satisfaction after service failure: An experimental investigation of mediating and moderating factors. J. Serv. Res. 2007, 10, 187–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escobar-Rodríguez, T.; Grávalos-Gastaminza, M.A.; Perez-Calanas, C. Facebook and the intention of purchasing tourism products: Moderating effects of gender, age and marital status. Scand. J. Hosp. Tour. 2017, 17, 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Ariza-Montes, A.; Tirado-Valencia, P.; Lee, S. Volunteering attitude, mental well-being, and loyalty for the non-profit religious organization of volunteer tourism. Sustainability 2020, 12, 4618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, S.J. Investigating beliefs, attitudes, and intentions regarding green restaurant patronage: An application of the extended theory of planned behavior with moderating effects of gender and age. Int. J. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 92, 102727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelet, J.É.; Lick, E.; Taieb, B. The internet of things in upscale hotels: Its impact on guests’ sensory experiences and behavior. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 33, 4035–4056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, L.G.; Sun, X. The effects of perception of video image and online word of mouth on tourists’ travel intentions: Based on the behaviors of short video platform users. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 984240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atulkar, S.; Kesari, B. Satisfaction, loyalty and repatronage intentions: Role of hedonic shopping values. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2017, 39, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wantono, A.; McKercher, B. Backpacking and risk perception: The case of solo Asian women. Tour. Recreat. Res. 2020, 45, 19–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, E.; Van Riper, C.; Kyle, G.; Wallen, K.; Absher, J. Accounting for gender in a study of the motivation-involvement relationship. Leisure Sci. 2018, 40, 494–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, R.; Westaway, D. Mental health rescue effects of women’s outdoor tourism: A role in COVID-19 recovery. Ann. Tour. Res. 2020, 85, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karagöz, D.; Işık, C.; Dogru, T.; Zhang, L. Solo female travel risks, anxiety and travel intentions: Examining the moderating role of online psychological-social support. Curr. Issues Tour. 2021, 24, 1595–1612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyers, L.J.; Loken, B. Revisiting gender differences: What we know and what lies ahead. J. Consum. Psychol. 2015, 25, 129–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakus, J.J.; Chen, W.; Schmitt, B.; Zarantonello, L. Experiences and happiness: The role of gender. Psychol. Mark. 2022, 39, 1646–1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hervé, C.; Mullet, E. Age and factors influencing consumer behaviour. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2009, 33, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, N.; Ringle, C.M.; Gudergan, S.; Feistel, M. The link between customer satisfaction and loyalty: The moderating role of customer characteristics. J. Strat. Mark. 2018, 26, 298–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, R.A.; Hollebeek, L.D. Customers’ service-related engagement, experience, and behavioral intent: Moderating role of age. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assaker, G.; Hallak, R.; Assaf, A.; Assad, T. Validating a structural model of destination image, satisfaction, and loyalty across gender and age: Multigroup analysis with PLS-SEM. Tour. Anal. 2015, 20, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, B.; Barreda, A.; Okumus, F.; Nusair, K. Website interactivity and brand development of online travel agencies in China: The moderating role of age. J. Bus. Res. 2019, 99, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loureiro, S.M.; Roschk, H. Differential effects of atmospheric cues on emotions and loyalty intention with respect to age under online/offline environment. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2014, 21, 211–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaichon, P.; Lobo, A.; Quach, T.N. The moderating role of age in customer loyalty formation process. Serv. Mark. Q. 2016, 37, 52–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.; Hollebeek, L.; Islam, J. Customer experience and commitment in retailing: Does customer age matter? J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2020, 57, 102219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mang, C.; Piper, L.; Brown, N. The incidence of smartphone usage among tourists. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 591–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, J.G. Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) with SPSS/Amos; Cheongram Publishing: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bae, B.J. Amos 27 Structural Equation Modeling; Cheongram Publishing: Seoul, Republic of Korea, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, H.; Fiore, A.M.; Jeoung, M. Measuring experience economy concepts: Tourism applications. J. Travel Res. 2007, 46, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campón-Cerro, A.; Di-Clemente, E.; Hernández-Mogollón, J.; Folgado-Fernández, J. Healthy water-based tourism experiences: Their contribution to quality of life, satisfaction and loyalty. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 103041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, T.; Gau, L.; Wu, T. Apply ground theory to interpret escapist experiences in Mudanwan Villa. Open. J. Soc. Sci. 2014, 2, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, Y.; Moon, H.C. What drives customer satisfaction, loyalty, and happiness in fast-food restaurants in China? Perceived price, service quality, food quality, physical environment quality, and the moderating role of gender. Foods 2020, 9, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Isa, S.; Ramayah, T.; Blanes, R.; Kiumarsi, S. The effects of destination brand personality on Chinese tourists’ revisit intention to Glasgow: An examination across gender. J. Int. Consum. Mark. 2020, 32, 435–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liébana-Cabanillas, F.; Singh, N.; Kalinic, Z.; Carvajal-Trujillo, E. Examining the determinants of continuance intention to use and the moderating effect of the gender and age of users of NFC mobile payments: A multi-analytical approach. Inform. Technol. Manag. 2021, 22, 133–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanson, H.; Ferrari, J.R. Older adults and clutter: Age differences in clutter impact, psychological home, and subjective well-being. Behav. Sci. 2022, 12, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nasir, M.; Mohamad, M.; Ghani, N.; Afthanorhan, A. Testing mediation roles of place attachment and tourist satisfaction on destination attractiveness and destination loyalty relationship using phantom approach. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2020, 10, 443–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Details | Frequency | Rate % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | F | 213 | 47.9 |

| M | 232 | 52.1 | |

| Age | Under 20 | 15 | 3.4 |

| 20–30 | 98 | 22 | |

| 31–40 | 109 | 24.5 | |

| 41–50 | 146 | 32.8 | |

| Over 50 | 77 | 17.3 | |

| Education | Less than high school | 47 | 10.6 |

| High school/technical school | 177 | 39.8 | |

| Bachelor’s degree | 147 | 33 | |

| Master’s degree or higher | 74 | 16.6 | |

| Occupation | Student | 36 | 8.1 |

| Public sector | 101 | 22.7 | |

| Private sector | 140 | 31.5 | |

| Self-employed | 127 | 28.5 | |

| Others | 41 | 9.2 | |

| Monthly income (yuan) | Under 2000 | 8 | 1.8 |

| 2001–3000 | 59 | 13.3 | |

| 3001–4000 | 135 | 30.3 | |

| 4001–5000 | 149 | 33.5 | |

| Over 5000 | 94 | 21.1 | |

| Participation in wellness tourism | Once | 177 | 39.8 |

| Twice | 144 | 32.4 | |

| Three times | 80 | 18 | |

| More than four times | 44 | 9.9 | |

| Observed Variable | Mean (SD) | Factor Loading | t Value | CR | AVE | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.878) | 3.429 (0.806) | 0.879 | 0.646 | Luo et al. [60]; He et al. [87] | ||

| The wellness tourism experience has made me more knowledgeable. | 3.46 (0.933) | 0.885 | ||||

| The wellness tourism experience has helped me learn a lot. | 3.49 (0.914) | 0.784 | 19.755 | |||

| The wellness tourism experience stimulates my curiosity to learn new things. | 3.26 (1.032) | 0.775 | 19.386 | |||

| Wellness tourism is a real learning experience. | 3.51 (0.889) | 0.766 | 19.066 | |||

| Entertainment (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.827) | 3.65 (0.594) | 0.828 | 0.548 | |||

| Wellness tourism experience activities make me feel happy. | 3.76 (0.736) | 0.808 | ||||

| Wellness tourism activities make me feel relaxed and are fun. | 3.60 (0.763) | 0.715 | 14.774 | |||

| The experience of wellness tourism is refreshing for me. | 3.64 (0.745) | 0.710 | 14.681 | |||

| Wellness tourism activities are enjoyable. | 3.61 (0.687) | 0.724 | 14.984 | |||

| Esthetic (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.844) | 3.59 (0.607) | 0.847 | 0.582 | |||

| When I undertake wellness tourism, I feel a real sense of harmony. | 3.65 (0.725) | 0.853 | ||||

| The experience of wellness tourism gives me sensory enjoyment through sight, hearing, smell, and taste. | 3.60 (0.749) | 0.760 | 17.505 | |||

| The theme of a wellness tourism destination is distinctive. | 3.46 (0.745) | 0.689 | 15.449 | |||

| Wellness tourism destinations have a unique local culture. | 3.69 (0.725) | 0.741 | 16.950 | |||

| Escapist (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.809) | 3.61 (0.656) | 0.816 | 0.529 | |||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, I feel like I am a different person. | 3.63 (0.799) | 0.868 | ||||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, I feel like I am living in a different time or place. | 3.59 (0.870) | 0.701 | 15.000 | |||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, the experience here makes me imagine being someone else. | 3.75 (0.845) | 0.675 | 14.383 | |||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, I completely escape from reality and forget about my stress and worries. | 3.48 (0.784) | 0.647 | 13.709 | |||

| Hedonic (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.885) | 3.85 (0.590) | 0.889 | 0.575 | Su et al. [34]; Vada [89] | ||

| Wellness tourism gives me a strong sense of enjoyment. | 3.62 (0.721) | 0.882 | ||||

| Wellness tourism gives me great pleasure. | 3.54 (0.748) | 0.842 | 23.223 | |||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, I feel more satisfied than I do when engaging in most other activities. | 3.58 (0.689) | 0.776 | 20.215 | |||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, I feel good. | 3.62 (0.743) | 0.750 | 19.106 | |||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, I feel a warm glow. | 3.52 (0.702) | 0.628 | 14.761 | |||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, I feel happier than I do when engaging in most other activities. | 3.60 (0.746) | 0.640 | 15.153 | |||

| Eudaimonic (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.874) | 3.57 (0.578) | 0.870 | 0.540 | |||

| Wellness tourism gives me the great feeling of really being alive. | 3.56 (0.747) | 0.829 | ||||

| Wellness tourism gives me a strong feeling that this is who I really am. | 3.53 (0.752) | 0.790 | 18.976 | |||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, I feel more intensely involved than in most other activities. | 3.51 (0.829) | 0.746 | 17.539 | |||

| When I engage in wellness tourism, I feel that this is what I was meant to do. | 3.63 (0.731) | 0.681 | 15.544 | |||

| I feel more complete or fulfilled when engaging in wellness tourism than I do when engaging in most other activities. | 3.52 (0.761) | 0.675 | 15.360 | |||

| I feel a particular fit or enmeshment when engaging in wellness tourism. | 3.40 (0.772) | 0.674 | 15.351 | |||

| Tourist satisfaction (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.858) | 3.52 (0.599) | 0.859 | 0.551 | Biswas et al. [93] | ||

| I am very interested in visiting wellness tourism destinations. | 3.78 (0.719) | 0.822 | ||||

| I think it is a wise choice to engage in wellness tourism. | 3.78 (0.768) | 0.753 | 17.220 | |||

| I am glad to have experienced wellness tourism activities. | 4.04 (0.764) | 0.699 | 15.663 | |||

| The wellness tourism experience met my needs. | 3.81 (0.715) | 0.760 | 17.426 | |||

| I am generally satisfied with the wellness tourism experience. | 3.86 (0.736) | 0.669 | 14.835 |

| Variable | a | b | c | d | e | f | g |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational (a) | 0.803 | ||||||

| Entertainment (b) | 0.289 | 0.740 | |||||

| Esthetic (c) | 0.405 | 0.377 | 0.762 | ||||

| Escapist (d) | 0.369 | 0.343 | 0.270 | 0.727 | |||

| Satisfaction (e) | 0.489 | 0.419 | 0.566 | 0.325 | 0.742 | ||

| Hedonic (f) | 0.463 | 0.469 | 0.528 | 0.473 | 0.612 | 0.758 | |

| Eudaimonic (g) | 0.546 | 0.467 | 0.582 | 0.426 | 0.679 | 0.600 | 0.734 |

| Hypothetical Path | Standardized Path Coefficient | S.E. | C.R. | p | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H1a: Educational→Hedonic | 0.075 | 0.039 | 1.459 | 0.145 | no |

| H1b: Educational→Eudaimonic | 0.194 | 0.035 | 4.185 | *** | yes |

| H1c: Entertainment→Hedonic | 0.152 | 0.054 | 3.008 | 0.003 ** | yes |

| H1d: Entertainment→Eudaimonic | 0.125 | 0.047 | 2.747 | 0.006 ** | yes |

| H1e: Esthetic→Hedonic | 0.233 | 0.059 | 4.060 | *** | yes |

| H1f: Esthetic→Eudaimonic | 0.200 | 0.052 | 3.879 | *** | yes |

| H1g: Escapist→Hedonic | 0.217 | 0.043 | 4.590 | *** | yes |

| H1h: Escapist→Eudaimonic | 0.132 | 0.038 | 3.136 | 0.002 ** | yes |

| H2a: Educational→Satisfaction | 0.294 | 0.038 | 5.591 | *** | yes |

| H2b: Entertainment→Satisfaction | 0.185 | 0.053 | 3.466 | *** | yes |

| H2c: Esthetic→Satisfaction | 0.410 | 0.053 | 7.340 | *** | yes |

| H2d: Escapist→Satisfaction | 0.038 | 0.043 | 0.755 | 0.450 | no |

| H3a: Satisfaction→Hedonic | 0.313 | 0.068 | 4.930 | *** | yes |

| H3b: Satisfaction→Eudaimonic | 0.431 | 0.062 | 7.259 | *** | yes |

| Mediating Effect Path | Significance (Two-Tailed Test) | 95% Confidence Interval | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Lower Limit | Upper Limit | ||

| H4a: Educational→Satisfaction→Hedonic | 0.001 | 0.052 | 0.237 |

| H4b: Educational→Satisfaction→Eudaimonic | 0.003 | 0.032 | 0.181 |

| H4c: Entertainment→Satisfaction→Hedonic | 0.003 | 0.021 | 0.184 |

| H4d: Entertainment→Satisfaction→Eudaimonic | 0.006 | 0.011 | 0.152 |

| H4e: Esthetic→Satisfaction→Hedonic | 0.000 | 0.084 | 0.324 |

| H4f: Esthetic→Satisfaction→Eudaimonic | 0.003 | 0.041 | 0.276 |

| H4g: Escapist→Satisfaction→Hedonic | 0.415 | −0.033 | 0.072 |

| H4h: Escapist→Satisfaction→Eudaimonic | 0.374 | −0.021 | 0.061 |

| Hypothetical Path | Path Coefficient of Population | Female | Male | Difference Ratio | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational→Eudaimonic | 0.194 *** | 0.180 * | 0.145 ** | 17.9% | yes |

| Entertainment→Hedonic | 0.152 ** | 0.001 | 0.249 *** | 163% | no |

| Entertainment→Eudaimonic | 0.125 ** | 0.019 | 0.224 *** | 164% | no |

| Esthetic→Hedonic | 0.233 *** | 0.250 ** | 0.264 ** | 6.1% | yes |

| Esthetic→Eudaimonic | 0.200 *** | −0.011 | 0.426 *** | 207% | no |

| Escapist→Hedonic | 0.217 *** | 0.318 *** | 0.168 ** | 69% | yes |

| Escapist→Eudaimonic | 0.132 ** | 0.128 | 0.164 ** | 27.3% | no |

| Educational→Satisfaction | 0.294 *** | 0.394 *** | 0.226 ** | 57.1% | yes |

| Entertainment→Satisfaction | 0.185 *** | 0.290 *** | 0.105 | 100% | no |

| Esthetic→Satisfaction | 0.410 *** | 0.310 *** | 0.506 *** | 47.8% | yes |

| Satisfaction→Hedonic | 0.313 *** | 0.470 *** | 0.175 * | 94% | yes |

| Satisfaction→Eudaimonic | 0.431 *** | 0.656 *** | 0.205 ** | 104% | yes |

| Hypothetical Path | Path Coefficient of Population | Young Age Group | Older Age Group | Difference Ratio | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educational→Eudaimonic | 0.194 *** | 0.170 ** | 0.201 * | 15.9% | yes |

| Entertainment→Hedonic | 0.152 ** | 0.071 | 0.258 *** | 123% | no |

| Entertainment→Eudaimonic | 0.125 ** | 0.097 | 0.161 * | 51.2% | no |

| Esthetic→Hedonic | 0.233 *** | 0.262 *** | 0.187 * | 32.1% | yes |

| Esthetic→Eudaimonic | 0.200 *** | 0.162 * | 0.247 * | 42.5% | yes |

| Escapist→Hedonic | 0.217 *** | 0.186 * | 0.235 *** | 22.5% | yes |

| Escapist→Eudaimonic | 0.132 ** | 0.204 *** | 0.080 | 93.9% | no |

| Educational→Satisfaction | 0.294 *** | 0.331 *** | 0.272 ** | 20% | yes |

| Entertainment→Satisfaction | 0.185 *** | 0.155 * | 0.214 * | 31.8% | yes |

| Esthetic→Satisfaction | 0.410 *** | 0.465 *** | 0.346 *** | 29% | yes |

| Satisfaction→Hedonic | 0.313 *** | 0.408 *** | 0.198 * | 67% | yes |

| Satisfaction→Eudaimonic | 0.431 *** | 0.567 *** | 0.286 ** | 65% | yes |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, X. The Impact of the Wellness Tourism Experience on Tourist Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Tourist Satisfaction. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031872

Liu L, Zhou Y, Sun X. The Impact of the Wellness Tourism Experience on Tourist Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Tourist Satisfaction. Sustainability. 2023; 15(3):1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031872

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Ligang, Yang Zhou, and Xiao Sun. 2023. "The Impact of the Wellness Tourism Experience on Tourist Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Tourist Satisfaction" Sustainability 15, no. 3: 1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031872

APA StyleLiu, L., Zhou, Y., & Sun, X. (2023). The Impact of the Wellness Tourism Experience on Tourist Well-Being: The Mediating Role of Tourist Satisfaction. Sustainability, 15(3), 1872. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15031872