Abstract

Little is known about SMEs’ perceptions of CSR, sustainability, and business ethics, particularly in the fashion industry. We have even less information on the relationship between SMEs’ CSR actions and employer branding. This important knowledge gap is addressed in this study. We intend to focus on how small and medium-sized enterprises that are operating and considered sustainable in the fashion industry interpret the concept of sustainability, corporate social responsibility (CSR), and business ethics, which CSR elements appear in relation to employees, and how they contribute to employer branding. In the course of our qualitative research, we conducted semistructured, in-depth interviews with the owners and managers of 10 European businesses, bearing sustainability in mind. Our results show that the organisational culture and the reputation perceived by a wide range of stakeholders are the most essential elements of employer branding, which promotes employees’ commitment to sustainable fashion enterprises.

1. Introduction

Sustainability and corporate social responsibility (CSR) issues have recently come to the fore in the fashion industry. The fashion industry’s role in the economy is unquestionable. In the European Union, the textile industry provides job opportunities for 1.5 million people, of which the fashion industry accounts for almost half, generating approximately EUR 160 billion in turnover annually, predominantly (90%) from small businesses [1]. Products manufactured and marketed in the global fashion industry face various state-level regulations, rules, employment opportunities, and environmental conditions [2]. However, the fashion industry is also the second largest industrial polluter in the world [3]. Human rights issues, equal opportunities, fair and ethical working conditions, and the proper management of natural resources are just some of the global issues for which the United Nations (UN) sustainable development goals seek to find solutions in a targeted manner within the framework of cooperation at various levels [4]. Sustainable fashion includes several factors, such as ethical design and sources, environmentally friendly materials and production techniques, local production, waste management, recycling, fair trade, fair wages, transparency, and conscious consumers [5,6].

Due to serious requirements for innovation, service or product quality, flexibility, and the ability to cope with lockdowns caused by epidemics and pandemics (e.g., Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS), Influenza, and the COVID-19 coronavirus), small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) have always been subjected to increased pressures in the manufacturing and service sectors in particular [7,8]. These phenomena have caused a recessionary trend in the global economy, with no single nation being able to cope with the impacts, resulting in a total of 5.2% shrinkage in 2020 [9]. Since the advent and growth of online retailers, the threat has reached SMEs in fashion retail as well, leading to their ever-improving quest for survivability. SMEs are contributors to job creation, poverty alleviation, and economic prosperity [10], yet the evolutionary approach to cyberstore development, i.e., the “web-weaving” process, includes how an e-retail enterprise, in a highly competitive/dynamic market, can develop and sustain a transactional e-business over a longer period. In the fashion industry, utilising the power of human resource (HR) management elements has also come into the limelight [11], and as a result of criticism, sustainability and CSR issues are increasing among the global issues facing the industry [12].

For global fashion industry supply chains, numerous fashion-industry-related research works highlight the obstacles and supporting factors of CSR [13], emphasising that the expectations of large companies in developing countries influence the CSR activities of fashion industry SMEs [14], but local specificities and historical context must be taken into account [15]. At the same time, in developed countries, branding and social media strategies are the main drivers of the CSR activities of SMEs in the fashion industry [16]. The authors of [17] identified four CSR activities of fashion industry SMEs: (1) environment-related CSR, (2) workplace CSR, (3) community-related CSR, and (4) marketplace CSR. CSR programmes positively impact not only SMEs’ reputations but also their innovation and competitive position [18]. However, the costs of CSR programmes and their internal and external communication represent a significant obstacle for SMEs in the fashion industry [19,20].

Workplace CSR includes issues of recruitment, diversity, pay and working conditions, health and safety, and human rights and can appear in a code of conduct, specific benefits for employees, and the evaluation system [17]. However, the impact of CSR on employees goes beyond the way the company treats its employees since CSR activities are also related to commitment and the retention and attraction of employees. Research in several different industries has shown the positive impact of CSR practices. Every company has an employer brand, but active employer branding aims to attract, retain, motivate, and inspire potential and existing high-quality employees in order to give the company a sustainable competitive advantage [21,22]. There is a link between employer branding and CSR activities. The positive impact on attracting and retaining employees is particularly evident for those factors of CSR that directly affect employees, such as fair, safe, and good working conditions or training and career opportunities [23].

Employer branding might be challenging for SMEs with scarce resources operating in a highly competitive environment, yet the literature is still limited [24,25]. Small fashion businesses face significant competition, especially from sustainability-oriented businesses that must compete with low-cost, well-known fast fashion brands, while new technologies require attracting and retaining talented workers who embrace sustainability values [26]. This can be accomplished with the application of employer branding and be facilitated by CSR activities in these businesses. In the post-COVID-19 years, when adequate and well-proven supply chains are more than challenged, SMEs in the fashion industry also face people management issues in the fields of recruitment, selection, and, more than ever, retention. We see a constant organisational need for both internal and external attraction towards the labour force. This was the reason behind the authors’ decision to scrutinise these subject areas with the potential to overlap. To the best of our knowledge, no research work has examined how the CSR activity of fashion SMEs promotes employer branding. Our research aims to cover this research gap. To put this in a broader context, we formulated two research questions: (1) How do SMEs in the fashion industry interpret the concepts of CSR and sustainability? and (2) Which elements of small business employer branding are emphasised in the fashion industry?

2. Background

2.1. CSR: The Concept of Sustainability and Business Ethics

CSR is very popular both in theory and in practice, yet its concept is vague [27,28]. In corporate practice, CSR is present in many ways, from philanthropy to increased operational efficiency to the new business model [29], and countless definitions of CSR are known [30]. In the classic definition of CSR in the history of CSR, Carroll distinguished four dimensions, namely, economic, legal, ethical, and charitable responsibilities, which appeared in his late work as well [31,32]. Critiques of these four pillars, especially charity, have contributed to the development of different concepts of modern CSR; however, the aspects of the corporate sector have changed significantly due to newly emerging issues, the constantly renewing environment of companies, the continuous expansion of the stakeholder circle, different national and international legislations, and not the least, the consequence of globalisation [33]. Related concepts such as sustainable development, good corporate citizenship, sustainable entrepreneurship, triple bottom line, business ethics, and CSR can be found in the literature [34,35].

The concepts of CSR and corporate sustainability are considered synonymous by many [34], while others consider the differences between them important [36]. According to [35], the reason for the popularity of the term “corporate sustainability” is that it is considered neutral, omits the terms “responsibility” and “ethics”, and is much less critical. At the same time, many ethical aspects appear in the concept of sustainability, such as justice between the present and future generations, as well as helping the disadvantaged [37]. The authors of [38] classify sustainability as a value-based, ethical CSR concept, and based on numerous empirical studies, both sustainable development and CSR show synergy with business ethics [39]. In our study, we use the concepts of CSR and corporate sustainability as synonyms but also emphasise that, in our interpretation, both include ethical responsibility towards stakeholders [32,40] and the integration of economic, environmental, social, and ethical aspects into corporate operations, decision making, and the creation of common values for external and internal stakeholders [27,34].

2.2. The Impact of CSR on the Attraction, Commitment, and Retention of Employees

There is a common understanding that CSR melds specific social and environmental issues together with corporate aspects, thus forming the organisation’s reputation and shaping the firm’s values [41,42,43,44,45,46,47]. While, on the one hand, perceived CSR makes a notable difference in customer attitudes towards even weaker brands [48], on the other, results reveal that a company’s CSR initiatives increase employee–company identification [49].

All of this is, as research results show, based on employee perceptions of CSR; how employees understand, interpret, and even judge their company’s CSR; and other related notions, such as organisational identification, corporate culture, and intention to stay. The mentioned items, in turn, influence work attitudes and behaviours [50,51]. While some studies deal with how employee perceptions of CSR affect employee behaviour, only a few investigate whether employee perceptions of internal and external CSR influence the behavioural outcomes of employees working in organisations, one of them arguing that employees tend to perform over that required of them if their organisation fosters positive social relations with them [52]. Research papers demonstrate that when companies apply an internal CSR attitude, employees have the feeling that their well-being is highly valued, which results in greater organisational commitment [53,54,55].

CSR has appeared in the HR management and leadership literature as well [56,57,58]. The author of [59] emphasises the significance of authentic leadership traits that play a major role in attaching meaning to enacted CSR and managing employee attribution processes diligently. The authors of [60] took a step further by revealing that one effective way to build and motivate employees’ customer-oriented behaviours is to develop CSR strategies and allocate CSR resources. These perspectives, or mental models of employees, include friendly and supportive co-workers, teamwork, and supportive and effective management as the top three values [61]. As a foreseeable outcome of these properly communicated, coherent, and management-led internal CSR practices, employee communicative behaviours develop further between a company and its employees [62].

This path inevitably leads to the heart of employee involvement, engagement, and commitment. Their interconnected relations to CSR have so far received limited attention from companies and researchers [63,64]. One possible reason for this came from an examination of whether different forms of CSR have different impacts on employee engagement [65]; it resulted in the realisation that no significant difference exists between the impacts of internal and external forms of CSR on respondents. Since commitment is driven by employee perceptions of CSR, it can be achieved through employee involvement and recognition [66].

The authors of [67] argue that employee commitment is associated with payment, promotion, fringe benefits, co-worker communication, operating procedures, and the nature of the work. The work in [68] mentions that due to the poor communication of CSR to employees and a weak CSR culture, a particular perceived lack of embeddedness can be experienced within organisations due to the separation of organisational and personal engagement with CSR activities. Their study also shows that employees hold diverse views towards organisational CSR and differ in their levels of engagement, including (1) being fully engaged, (2) valuing personal CSR outside the workplace, and (3) perceiving no value of CSR engagement at all.

As the years have passed, what employer branding meant at the beginning [69], i.e., improving employer attractiveness to current and prospective employees by merging marketing and HR elements, has slowly established a different focus. Although employer branding was seen as an integral part of an organisation’s sustainability strategy by the end of the 2010s, researchers experienced some counter-examples [70]: not taking advantage of including CSR information in job advertisements. In a world where virtual space and social networks had become a common part of posting job offers in the recruitment process [71], a great chance to find suitable talent seemed to fade away in this way. The authors of [72] examined CSR as an important attribute of employer branding for retaining competent employees, and they confirmed that social responsibility substantially influences retention at an organisation. Moreover, new paths of employer branding ideas have been born, i.e., one that reconceptualised it as a holistic and processual discipline, including the theories of branding, HR management, and CSR [73], or one that integrated CSR and human rights into one, creating “corporate human rights social responsibility” to demonstrate the multidimensional feature as a tool to enhance organisational performance based on unique recruitment and retention [74]. Even potential future employees can be affected by corporate attention to social responsibility, social well-being, and environmental responsibility, as shown by a study on business school students [75].

2.3. CSR and Employer Branding in SMEs

The interpretation and application of CSR in the SME sector have a shorter history and were under-researched for a long time [76,77]. Previous research works have thoroughly explored the fact that CSR is less compatible with the operation and basic strategy of SMEs due to the necessity of survival, scarcer resources, less visibility [78], and less formalised ethical institutions [79]. Meanwhile, many articles argue for the development and integration of SME CSR practices [80,81], taking into account the essential characteristics of SMEs, such as the significant role of owner-manager relationships, personal relationships or informal mechanisms [82], different organisational structures and cultures [83], and identifying CSR areas within the SME sector [84]. The ethical aspects of responsibility also appear among SMEs. Some studies have shown that small businesses want to believe in their good deeds and positive contributions to integrity and satisfaction, while their operations can increase the market share in the long run by building a trusted brand name and reputation [85].

At the same time, the expectations of socially close stakeholders [86], such as employees and the local community, seem to have a positive effect on the responsibility of SMEs, while external pressure is experienced negatively [87]. Most of the studies interpret the social responsibility of SMEs within the framework of stakeholder theory, highlighting owner-managers, customers, employees, local communities, and the natural environment among the stakeholders [78,79,88,89,90]. Typical SME CSR areas are environmental protection, the fair treatment of employees, good corporate climate, work–life balance, and the support of the local environment [78,91,92]. High levels of CSR have a positive impact on the international performance and learning orientation of SMEs [93].

The challenges faced by SMEs include limited resources, recruitment processes, a risk-taking attitude, and a willingness to learn. As for the solutions, researchers find that structured and coordinated work–life balance procedures [94] and organisational innovation [95] mean a greater positive impact on small firms. All of these, as argued, can be most efficiently carried out by properly harmonised internal and external scopes of employer branding thinking and actions, which include the development and internal and external marketing of the employment value proposition (EVP) [96,97]. All of these strengthen the importance of employer branding in HR management in SMEs, since they may result in countless benefits (i.e., the attraction and retention of talent). SME employer branding models contain some different elements, but all integrate CSR. According to [25], SMEs operate without an HR and recruitment department and, thus, are intensively challenged to find a strategy to attract and retain new employees (i.e., talent). The authors developed an employer branding model that focuses on four dimensions (organisational culture, corporate strategy, company reputation, and reward system). In its “CSR employer branding process” model, [98] distinguishes four internal CSR signals: (1) CSR socialisation, which helps individuals identify with company values; (2) workplace benefits that go beyond legislation, such as recognition, flexibility, and work–life balance; (3) corporates that jointly create CSR initiatives’ ethical empowerment; and (4) equitable HR practices that ensure a fair and impartial work environment. The value propositions of the employer branding concept, based on the Business Model Canvas, include a good reputation, caring directly about employees outside the workplace, a friendly, informal company culture, good, strong relationships with colleagues, flexible working hours, freedom based on trust, a lack of hard control mechanisms (trust), and feedback and the appreciation of effort [99]. Employee-focused CSR activities have a positive impact on the perception of the employer brand in SMEs [100], commitment [98], and loyalty and work quality [99].

3. Methodology

This study applied a qualitative methodology to reveal the relationship between the CSR approaches and practices of small and medium-sized fashion enterprises within the European Union and their employer branding. Semistructured in-depth interviews were conducted with SME founders and/or owner-managers who had established sustainably running clothing SMEs. This study investigated the extent to which sustainability practices influence the HR processes of a small fashion company and whether important CSR values are reflected in the way they treat their stakeholders and, if so, in what aspects.

3.1. Qualitative Methodology and In-Depth Interviews

Qualitative data are not measured in quantity or frequency like quantitative data; rather, they are analysed in depth for the meaning of the data themselves [101]. A qualitative methodology provides an opportunity to explore attitudes, experiences, stories, beliefs, and in-depth interpretation [102] and allows a holistic approach paired with interpretivism [103]. Interviews are widely applied as data collection tools; furthermore, according to [104], one-on-one interviews are commonly used in qualitative research. The authors of [105] consider interviews to be the best method to obtain information in an interactive atmosphere. Hence, the interviewee has a chance to explore the subject with adequacy, accuracy, responsiveness, and clarification [106], which is of high importance in the current research not only to collect information but to gain deep insights into the possible interpretational differences of various theories and definitions from the fashion SMEs’ point of view. To conduct an effective interview, proper planning is essential [107]. Regarding preparation, [108,109] were considered for reviewing secondary data, critically reflecting on the question of “who” the interviewees will be, drafting the questions, and paying close attention to ethical permissions.

As the primary source of data, the data were collected through face-to-face interviews scheduled using Microsoft Teams between January and July 2022. Teams proved to be the perfect platform for both researchers and interviewees to explore the topic in more depth, allowing them to describe their perceptions and practices in detail. Using the online platform, the interviewees were able to talk to us about the issues raised without any cost, time, or geographical challenges. The interviews were conducted in a good atmosphere, and the openness of the subjects gave us insight into their daily business operations. This allowed us to gather primary and relevant information.

3.2. Data Sampling and Processing

The interviews were conducted with 10 fashion SMEs located in the European Union, specifically 2 Hungarian, 2 Italian, 2 Slovenian, 2 Romanian, 1 German, and 1 Slovakian fashion enterprise. The sample consisted of nine women and one man, with most participants having an operating business for more than five years. The number of employees varied between 12 and 87; hence, based on [110]’s SME definition, taking into account the staff headcount, micro, small, and medium-sized firms were present in the sample. The aim was to obtain data from fashion SME owner-managers about their internal and external CSR and sustainability attempts regarding employee attraction and retention.

The interviewees were selected in a structured way. The first round involved the Fashion Revolution country coordinators of Central European countries that are also members of the European Union. The Fashion Revolution is a well-known and highly acknowledged international movement, especially by fashion SMEs; the movement offers cultural exchange opportunities and platforms for brainstorming and sharing industry-specific best practices and is constantly working on industrial changes, attempting to influence brands and retailers for a faster transition and response to consumer demands, and promoting practice-oriented incentives to achieve transparency and accountability. The Fashion Revolution has a publicly available local team in each country, with a country coordinator actively involved in the day-to-day activities of the sector, liaising with both large and small companies, with relevant knowledge of national market practices. Each coordinator was asked to propose the 3 best examples based on the following criteria: (1) the company meets the EU definition of a small and medium-sized enterprise, i.e., the number of employees is less than 250, (2) the company is active in the fashion industry, covering the clothing and other fashion accessories sector, (3) the company was founded at least five years ago and has been operating continuously ever since, (4) the company applies good practices in the domestic (or foreign) market in terms of sustainability and/or CSR. Through the recommendations of these coordinators, it was possible to connect with local small fashion businesses that are prominent members of the national industrial community from a sustainability perspective. Those companies were involved in this research and were willing to participate.

Table 1 introduces the selected interview partners, along with the country, type of initiative, sector, target market, foundation date, size in terms of employees, and interviewees’ positions.

Table 1.

Sample.

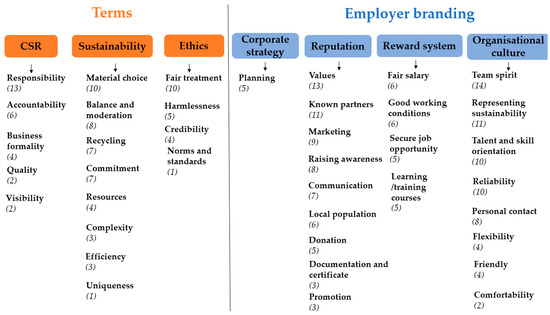

The current study relied on qualitative research [111], reviewing the works on the benefits and drawbacks of NVivo, a QSR software that can be used for various data analyses, involving documents, project items, data material, transcripts, and surveys. The coding procedure allowed texts to be read through, identifying relevant parts with an analytical and inductive approach to categorising the obtained data. The literature distinguishes between inductive and deductive coding [112]. Inductive coding develops codes as data are being processed, while with the deductive approach [113], the researcher predetermines codes and themes and then delves deeper into the data by organising [114]. The current research applied an inductive approach, so there were no preconceived concepts. The codes defined based on the research questions were further categorised into nodes to create a holistic code structure, and by representing units of observation, cases were created with various attributes and variables. As a final step before the data analysis, case classification led to the acquisition of descriptive information from the manuscripts. Figure 1 details the codes and node structure the authors applied. Each node is completed with the number of references, which is the count of the number of selections within that source that have been coded to any node.

Figure 1.

Code and node structure applied in NVivo. Source: own elaboration.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of CSR and Sustainability Amongst Fashion Industry SMEs

Regarding the interpretation of sustainability and CSR, we asked the interviewees about both of these concepts and also the concept of business ethics. For the surveyed small business owners/managers in the fashion industry, future orientation, the consideration of others (corporate stakeholders), care, and the creation of balance and harmony amongst the three pillars of sustainability prominently appear in connection with the concept of sustainability. The answers also revealed the interpretation of sustainability as awareness and responsibility. Based on the answers, the concept of sustainability is included in Table 2.

Table 2.

Fashion SMEs’ understanding of sustainability.

The authors discovered differences in the interpretation of CSR in connection with companies representing individual countries. According to the interviewed Hungarian business owners, CSR is basically the same as sustainability, only in a corporate context. However, one of them emphasised that the two concepts are somewhat different, since in his opinion, CSR is voluntary, while “sustainability is something that I do because it is not an option. It is more natural”. According to the Slovak company owner, CSR is also a voluntary activity.

For the majority of business owners representing other countries, the stakeholder approach [40] and the impact on others are important in CSR interpretations. The owner of the interviewed Italian fashion company put it this way: “It means not just looking at the bottom line but looking at how and to what extent our business activities impact the environment and society”. A Slovenian business owner put it similarly: “I believe that being responsible is necessary because it goes without saying that what we do affects others”. The owner of one of the Romanian companies also interpreted CSR as having an impact on others and beyond profit and emphasised that it must be “visible”. According to the Slovenian respondent, the essence of CSR is that “ethical operation is the basis of our business”. Our research results agree with the results of previous research. The emphasis on social and environmental impacts appears several times in connection with sustainable enterprises [115]. The reduction in the negative effects of the operation also appeared as the main aspect for SMEs in the Italian fashion industry [116].

When interpreting business ethics, the Romanian owner returned his basic definition: “It is very important that our products do not cause problems or harm to anyone.” In other answers, many values appeared. The Slovak owner put it this way: “To me, business ethics brings with honesty, keeping promises, reliability, loyalty on both sides, and of course, legal rules which is very important in the life of any business”. One of the Slovenian respondents emphasised that the company’s values must be “real and true”. All of the Hungarian answers regarding fair behaviour were about avoiding unfair behaviour: “I think when we talk about ethics, we try to avoid anything that is unfair”. Another respondent put it this way: “You have to be fair not only to the external environment, but also to the internal environment”. However, specific activities were also referred to: “My producing point of view, being ethical is giving fair wages, pay worker, for their skills and so on. At the same time, when we think about it from a consumption perspective, it is well, to give the product the right price”. Additional examples were also given regarding individual stakeholders: “We are always strict about paying our suppliers and partners on time. As this is a skill intensive industry, we are very careful to ensure that everyone can do their job safely”. According to the Italian entrepreneur, the terms “sustainability”, “CSR”, and “business ethics” cover something similar: “My responsibility, that they get paid on time, that they are healthy, that they have a perspective on life and opportunity. I think these are all congruent words”.

4.2. CSR and Employer Branding in SMEs

We asked the owner-managers of SMEs in the fashion industry about how their CSR measures for employees affect the attraction and retention of employees and employer branding. Based on the SME employer branding dimensions of [25], we reviewed the answers of the owner-managers of the examined enterprises. Table 3 contains the answers related to dimension 4 (reward system), which included financial and nonfinancial incentives [25]. More than half of the interviewed owner-managers mentioned the factor related to the reward system. Among them was that they offer good, competitive, and fair pay; good conditions; and long-term work opportunities to employees. Several people pointed out that no one was fired during the COVID-19 pandemic. For years, global Employer Brand Research has also rated salary as the most important factor in job selection [117]. In our survey of the fashion industry, half of the respondents emphasised training courses. According to reskilling and upskilling, it is one of the factors that the vast majority of employees (76%) expect, but only 61% of talented people feel that they will receive it [117]. The respondents emphasised that talent, creativity, good insights, and freedom are important in fashion SMEs, so one company prefers to employ interns, who are offered learning opportunities.

Table 3.

Employer branding dimension 4: reward system in fashion industry SMEs.

In relation to the corporate reputation, we took into account the feedback received from the company’s stakeholders by the interviewed owner-managers and their efforts to increase the corporate reputation. These are summarised in Table 4. A company’s reputation is “stakeholders’ collective knowledge” [118] (p. 320) and “aggregate perceptions by stakeholders”, on the basis of which they decide whether they want to buy the company’s products or carry out other activities, such as become its employees or invest in it [119] (p. 43). SMEs typically have a few financial resources to develop their reputation, but their personal relationships are very important for this [120]. In relation to the corporate reputation of SMEs in the fashion industry, customer satisfaction, employee satisfaction, and the support of the local community are crucial factors. Both online and personal tools are used to strengthen the reputation. At the same time, a shared value system with suppliers and partners also strongly appears, which, for some respondents, is formalised in a code of conduct and the expectation of certification. Our results agree with the fact that Vietnamese fashion has also appeared among SMEs; that fair payment and wages are also considered important by partners; and that suppliers comply with all aspects of safety, child labour, or forced labour while sourcing [14].

Table 4.

Employer branding dimension 3: company reputation of fashion industry SMEs.

There are a few references to the company’s strategy in the interviews summarised in Table 5. One respondent even says that they do not have a strategy. Another emphasises that they have a long-term plan. In other cases, conscious planning or an annual plan appears. The results indicating a lack of strategy in SMEs are the same as the results found in the literature.

Table 5.

Employer branding dimension 2: corporate strategy of fashion industry SMEs.

A reference to organisational culture appears in each interview (Table 6). A friendly, helpful, familiar, and trust-based atmosphere is vital for maintaining a community of sustainable fashion industry SMEs. By creating and maintaining a family culture, owner-managers satisfy the emotional and social expectations of employees [121]. Teamwork [61] and the fact that employees are considered internal customers are essential for these enterprises. It is crucial to respect sustainability as a common value and the feeling that they are doing something good by operating sustainably [98]. Not only is this typical for existing employees, but fashion SMEs’ owner-managers also look for such employees. One entrepreneur put it this way: “If you don’t want to think or work with sustainable materials, if you don’t see the potential in that, if you can’t free your mind to design or sew or manufacture in that way, we are unfortunately not the right company for you. Employees are also involved in CSR activities, which results in greater commitment”.

Table 6.

Employer branding dimension 1: organisational culture of fashion industry SMEs.

While performing the interviews, we carefully paid attention to answers including elements of employer branding. According to [25], the SME employer branding model focuses on four dimensions (organisational culture, corporate strategy, company reputation, and reward system), and SMEs operate without an HR and recruitment department and, thus, are intensively challenged to find a strategy to attract and retain new employees (i.e., talent). During the interviews, we posed questions that could elicit useful information on which of the dimensions carry importance for the 10 interviewed companies. We argue that all 10 interviewed companies have commonly shared values and a sound vision/mission of their operation (dimension #1), and 4 added hints of the presence of their reward system (dimension #4). Our interviews seem to have further strengthened the views of [25]: that is, SMEs in the fashion industry lack professional HR-related support functions within the company and are, thus, more likely to opt for ad hoc, personal solutions. The interviewees also showed a strong focus on corporate (and indeed industry-specific) values rather than corporate strategy and/or company reputation when raising in-house cohesion to aim for retention.

5. Conclusions

Based on interviews with the owner-managers of sustainable fashion SMEs, we can conclude that sustainability, CSR, and business ethics are interwoven and often interpreted as synonyms. This confirms the research of [122], in which the author argues that, in practice, these terms are used interchangeably. This is no coincidence since the development of CSR also reflects society’s expectations of companies, which, in recent years, have been moving towards sustainable development [123]. Applying the SME employer branding model of [25], organisational culture and caring for internal and external stakeholders and the reputation developed based on their feedback are crucial for these businesses. Two elements appear in connection with the reward system: wages and training. Strategy and long-term planning hardly appear in the case of sustainable fashion SMEs. According to [68], we can say that the individual value system of the employees and the value system mediated by the company are in harmony, which promotes full commitment. Based on our findings, we recommend that fashion SMEs be more conscious of the elements of employer branding [25] and emphasise their CSR practices and values to attract and retain high-quality employees in order to increase their competitiveness.

A limitation of the current research was that the interviews were conducted in English, so not all interviewees were able to express themselves as precisely as they would have in their native language. We did not examine the companies’ online appearances and job advertisements to see to what extent they used the benefits of including CSR information in job advertisements [70]. The sample did not cover all Central European countries, and some SMEs with best practices from each country participated. We also asked owner-managers whether a further study could be conducted to ask the employees what they perceive about this matter, since different target groups need different employment value propositions (EVPs) depending on gender, generation, and work experience [124]. These limitations might be worth further research. A subject of further investigation may also be the correlations between the demographic characteristics and opinions of the owner-managers, as well as cultural and socio-economic variables [125] or the legal origin of the countries [126] of the examined SMEs and the main findings of the research.

Author Contributions

Conceptualisation, K.S. and T.N.; methodology, D.K.; formal analysis, K.S., T.N. and D.K.; resources, T.N. and D.K.; writing—original draft preparation, K.S., T.N. and D.K.; writing—review and editing, K.S. and D.K.; supervision, K.S.; project administration, D.K. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to confidentiality restrictions posed by the interviewees.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- European Commission. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/sectors/fashion/textiles-and-clothing-industries/textiles-and-clothing-eu_en (accessed on 28 December 2022).

- Ferrigno, S.; Richero, R. A Background Analysis on Transparency and Traceability in the Garment Value Chain; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Niinimaki, K.; Peters, G.; Perry, P. The environmental price of fast fashion. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2020, 1, 189–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. The UN High Level Political Forum on Sustainability Development. Available online: https://hlpf.un.org/ (accessed on 13 July 2022).

- Achabou, M.A.; Dekhili, S. Luxury and sustainable development: Is there a match? J. Bus. Res. 2013, 66, 1896–1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henninger, C.E.; Alevizou, P.J.; Oates, C.J. What is sustainable fashion? J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2016, 20, 1361–2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raymond, L.; St-Pierre, J. Strategic capabilities for product innovation in SMEs: A Gestalts perspective. Int. J. Entrep. Innov. 2010, 11, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, R.; Naveed, M.; Hanif, S. An analysis of COVID-19 implications for SMEs in Pakistan. J. Chin. Econ. Foreign Trade Stud. 2021, 14, 74–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2020/06/08/the-global-economic-outlook-during-the-covid-19-pandemic-a-changed-world (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Ng, H.S.; Kee, D.M.H. The core competence of successful owner-managed SMEs. Manag. Decis. 2018, 56, 252–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashworth, C.J.; Schmidt, R.A.; Pioch, E.A.; Hallsworth, A. ‘Web-weaving’: An approach to sustainable e-retail and online advantage in lingerie fashion marketing. Int. J. Retail. Distrib. Manag. 2006, 34, 497–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinsey & Company. Available online: https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/mckinsey/industries/retail/our%20insights/state%20of%20fashion/2022/the-state-of-fashion-2022.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2022).

- Perry, P.; Towers, N. Conceptual framework development: CSR implementation in fashion supply chains. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2013, 43, 478–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayak, R.; Thang, L.N.V.; Nguyen, T.; Gaimster, J.; Morris, R.; Majo, G. Sustainable developments and corporate social responsibility in Vietnamese fashion enterprises. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2022, 26, 307–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund-Thomsen, P.; Jamali, D.; Vives, A. CSR in SMEs: An analysis of donor-financed management tools. Soc. Responsib. J. 2014, 10, 602–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienda, L.; Ruiz-Fernández, L.; Poveda-Pareja, E.; Andreu-Guerrero, R. CSR drivers of fashion SMEs and performance: The role of internationalization. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2022, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, M.; Testa, F.; Bianchi, L.; Iraldo, F.; Frey, M. Corporate social responsibility and competitiveness within SMEs of the fashion industry: Evidence from Italy and France. Sustainability 2014, 6, 872–893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermanto, B.; Romly, A.; Sukoco, I.; Purnomo, M. The effect of supply chain corporate social responsibility (CSR) program on small business innovation through entrepreneurial orientation. Uncertain Supply Chain. Manag. 2022, 10, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedes, G.; Ferreira, F.; Urbano, L.; Marques, A. Corporate social responsibility: Competitiveness in the context of textile and fashion value chain. Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 2017, 16, 1193–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, E.; Mark-Herbert, C. Relationship marketing in green fashion—A case study of hessnatur. In Green Fashion. Environmental Footprints and Eco-Design of Products and Processes, 1st ed.; Muthu, S., Gardetti, M., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2016; pp. 21–47. [Google Scholar]

- Backhaus, K. Employer Branding Revisited. Organ. Manag. J. 2016, 13, 193–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Näppä, A. Co-created employer brands: The interplay of strategy and identity. Eur. J. Train. Dev. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Bustamante, S.; Ehlscheidt, R.; Pelzeter, A.; Deckmann, A.; Freudenberger, F. The Effect of Values on the Attractiveness of Responsible Employers for Young Job Seekers. J. Hum. Values 2021, 27, 27–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moser, K.J.; Tumasjan, A.; Welpe, I.M. Small but attractive: Dimensions of new venture employer attractiveness and the moderating role of applicants’ entrepreneurial behaviors. J. Bus. Ventur. 2017, 32, 558–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monteiro, B.; Santos, V.; Reis, I.; Correia Sampaio, M.; Sousa, B.; Martinho, F.; Sousa, M.J.; Au-Yong-Oliveira, M. Employer branding applied to SMEs: A pioneering model proposal for attracting and retaining talent. Information 2020, 11, 574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Martínez, A.; Cegarra-Navarro, J.-G.; Garcia-Perez, A.; De Valon, T. Active listening to customers: Eco-innovation through value co-creation in the textile industry. J. Knowl. Manag. 2022; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Amaeshi, K.; Nnomid, P.; Onyeka, O. Corporate social Responsibility, Entrepreneurship, and Innovation, 1st ed.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams, A. Corporate social responsibility: A theory of the firm perspective. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 117–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rangan, K.; Chase, L.; Karim, S. The Truth About CSR. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlsrud, A. How corporate social responsibility is defined: An analysis of 37 definitions. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2006, 15, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. The Carroll Model: A 25-year retrospective and prospective view. Educ. Res. 1989, 18, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2016, 1, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, A.; Rodríguez-del-Bosque, I. Measuring CSR image: Three studies to develop and to validate a reliable measurement tool. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 118, 3–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marrewijk, M. Concepts and definitions of CSR and corporate sustainability: Between agency and communion. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 44, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, A.B. Corporate social responsibility: The centerpiece of competing and complementary frameworks. Organ. Dyn. 2015, 44, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheehy, B.; Farneti, F. Corporate social responsibility, sustainability, sustainable development and corporate sustainability: What is the difference, and does it matter? Sustainability 2021, 13, 5965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behringer, K.; Szegedi, K. The role of CSR in achieving sustainable development—Theoretical approach. Eur. Sci. J. 2016, 12, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garriga, E.; Melé, D. Corporate social responsibility theories: Mapping the territory. J. Bus. Ethics 2004, 53, 51–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doh, J.; Husterd, B.; Mattern, D.; Santoro, M. Ahoy there! Toward greater congruence and synergy between international business and business ethics theory and research. Bus. Ethics Q. 2010, 20, 481–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach, 1st ed.; Pitman: Boston, MA, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, H.R. Social Responsibility of the Businessman, 1st ed.; Harper & Row: New York, NY, USA, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, T.J.; Dacin, P.A. The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. J. Mark. 1997, 61, 68–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sen, S.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Does doing good always lead to doing better? Consumer reactions to corporate social responsibility. J. Mark. Res. 2011, 38, 225–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, C.M.; Rodrigues, L.L. Corporate social responsibility and resource-based perspectives. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 69, 111–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, X.; Bhattacharya, C.B. Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, G.; Beatty, S.E. Customer-based corporate reputation of a service firm: Scale development and validation. J. Acad. Mark. Sci. 2007, 35, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, K. A systematic review of the corporate reputation literature: Definition, measurement, and theory. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2010, 12, 357–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Doorn, J.; Onrust, M.; Verhoef, P.C.; Bügel, M.S. The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer attitudes and retention—the moderating role of brand success indicators. Mark Lett. 2017, 28, 607–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.-R.; Lee, M.; Lee, H.-T.; Kim, N.-M. Corporate social responsibility and employee–company identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 95, 557–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gond, J.-P.; Akremi, A.E.; Swaen, V.; Babu, N. The psychological microfoundations of corporate social responsibility: A person-centric systematic review. J. Organ. Behav. 2017, 38, 225–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Roeck, K.; Maon, F. Building the theoretical puzzle of employees’ reactions to corporate social responsibility: An integrative conceptual framework and research agenda. J. Bus. Ethics 2018, 149, 609–625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouakouak, M.L.; Arya, B.; Zaitouni, M. Corporate social responsibility and intention to quit—Mediating role of organizational citizenship behavior. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2020, 69, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofman, P.S.; Newman, A. The impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on organizational commitment and the moderating role of collectivism and masculinity: Evidence from China. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 25, 631–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mory, L.; Wirtz, B.W.; Göttel, V. Factors of internal corporate social responsibility and the effect on organizational commitment. Int. J. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2016, 27, 1393–1425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carnahan, S.; Kryscynski, D.; Olson, D. When does corporate social responsibility reduce employee turnover? Evidence from attorneys before and after 9/11. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 60, 1932–1962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, S.; Lynch, M. Beyond CSR: Preparing future leaders for a global economy. Dev. Learn. Organ. 2010, 24, 12–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Voorde, K.V.; Beijer, S. The role of employee HR attributions in the relationship between high-performance work systems and employee outcomes. Hum. Resour. Manag. J. 2014, 25, 62–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewett, R.; Shantz, A.; Mundy, J. Information, beliefs, and motivation: The antecedents to human resource attributions. J. Organ. Behav. 2019, 40, 570–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhary, R. Authentic leadership and meaningfulness at work Role of employees’ CSR perceptions and evaluations. Manag. Decis. 2019, 59, 2024–2039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X. The impact of employees’ perceived CSR on customer orientation: An integrated perspective of generalized exchange and social identity theory. Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2020, 32, 2345–2364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naude, M. Corporate governance, CSR and using mental models in employee retention. Corp. Ownersh. Control 2009, 7, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y. Linking internal CSR with the positive communicative behaviors of employees: The role of social exchange relationships and employee engagement. Soc. Responsib. J. 2020, 18, 348–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hejjas, K.; Graham, M.; Scarles, C. It’s like hating puppies! Employee disengagement and corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 157, 319–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Silva, K.M.; De Silva Lokuwaduge, C.S. Impact of corporate social responsibility practices on employee commitment. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, P.; Real de Oliveira, E. Does corporate social responsibility impact on employee engagement? J. Workplace Learn. 2014, 26, 232–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, R.; Johar, E.R.; Mat Nor, N. Managing the obligation to stay through employee involvement, recognition and AMO model: A study amongst millennial employees. Asian J. Bus. Account. 2020, 13, 93–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valaei, N.; Sunway, B.; Rezaei, S. Job satisfaction and organizational commitment: An empirical investigation among ICT-SMEs. Manag. Res. Rev. 2016, 39, 1663–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slack, R.E.; Corlett, S.; Morris, R. Exploring employee engagement with (corporate) social responsibility: A social exchange perspective on organisational participation. J. Bus. Ethics 2015, 127, 537–548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambler, T.; Barrow, S. The employer brand. J. Brand Manag. 1996, 4, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puncheva-Michelotti, P.; Hudson, S.; Jin, G. Employer branding and CSR communication in online recruitment advertising. Bus. Horiz. 2018, 61, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vetráková, M.; Hitka, M.; Potkány, M.; Lorincová, S.; Smerek, L. Corporate sustainability in the process of employee recruitment through social networks in conditions of Slovak small and medium enterprises. Sustainability 2018, 10, 1670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharadwaj, S.; Yameen, M. Analyzing the mediating effect of organizational identification on the relationship between CSR employer branding and employee retention. Manag. Res. Rev. 2021, 44, 718–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggerholm, H.K.; Andersen, S.E.; Thomsen, C. Conceptualising employer branding in sustainable organisations. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2011, 16, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheruiyot, T.K.; Maru, L.C. Corporate human rights social responsibility and employee job outcomes in Kenya. Int. J. Law Manag. 2014, 56, 152–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verčič, A.T.; Ćorić, D.S. The relationship between reputation, employer branding and corporate social responsibility. Public Relat. Rev. 2018, 44, 444–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tilley, F. Small firm environmental ethics: How deep do they go? Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2000, 9, 31–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vo, L.C. Corporate social responsibility and SMEs: A literature review and agenda for future research. Probl. Perspect. Manag. 2011, 9, 89–97. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkins, H. Small business champions for corporate social responsibility. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 241–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graafland, J.; van de Ven, B.; Stoffele, N. Strategies and Instruments for organising CSR by small and large businesses in the Netherlands. J. Bus. Ethics 2003, 47, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morsing, M.; Perrini, F. CSR in SMEs: Do SMEs matter for the CSR agenda? Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2008, 18, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, I.; Crane, A. Corporate social responsibility in small-and medium-size enterprises: Investigating employee engagement in fair trade companies. Bus. Ethics A Eur. Rev. 2010, 19, 126–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L. Does size matter? The state of the art in small business ethics. Bus. Ethics Environ. Responsib. 2002, 8, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Sanchez, D.; Barton, J.R.; Bower, D. Implementing environmental management in SMEs. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2003, 10, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, L.; Rutherfood, R. Small business and the environment in the UK and the Netherlands: Toward stakeholder cooperation. Bus. Ethics Q. 2000, 10, 945–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, D.; Lynch-Wood, G.; Ramsay, J. Drivers of environmental behaviour in manufacturing SMEs and the implications for CSR. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 317–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lähdesmäki, M.; Siltaoja, M.; Spence, L.J. Stakeholder salience for small businesses: A social proximity perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2019, 158, 373–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst, R.-A.; Gerken, M.; Hack, A.; Hülsbeck, M. SMES’ reluctance to embrace corporate sustainability: The effect of stakeholder pressure on self-determination and the role of social proximity. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 335, 130273–130287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, D.; Lozano, J.M. SMEs and CSR: An approach to CSR in their own words. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perrini, F. SMEs and CSR theory: Evidence and implications from an Italian perspective. J. Bus. Ethics 2006, 67, 305–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kusyk, S.; Lozaon, J. Corporate responsibility in small and medium-sized enterprises SME social performance: A fourcell typology of key drivers and barriers on social issues and their implications for stakeholder theory. Corp. Gov. 2007, 7, 502–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sweeney, L. Corporate social responsibility in Ireland: Barriers and opportunities experienced by SMEs when undertaking CSR. Corp. Gov. 2007, 7, 516–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sancho, M.P.L.; Jorge, M.L.; Jesús, H.M. Design and validation of an instrument of measurement for corporate social responsibility practices in small and medium enterprises. Soc. Responsib. J. 2021, 17, 1150–1174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torkkeli, L.; Durst, S. Corporate social responsibility of SMEs: Learning orientation and performance outcomes. Sustainability 2022, 14, 6387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, F.; McKie, L.; Beattie, R.; Hogg, G. A toolkit to support human resource practice. Pers. Rev. 2010, 39, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laforet, S. Organizational innovation outcomes in SMEs: Effects of age, size, and sector. J. World Bus. 2013, 48, 490–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backhaus, K.; Tikoo, S. Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Dev. Int. 2004, 9, 501–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karga, A.; Tsokos, A. Employer branding implementation and human resource management in Greek telecommunication industry. Adm. Sci. 2020, 10, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlini, J.; Grace, D.; France, C.; Lo Iacono, J. The corporate social responsibility (CSR) employer brand process: Integrative review and comprehensive model. J. Mark. Manag. 2019, 35, 182–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bite, P.; Konczos-Szombathelyi, M. Employer branding concept for small- and medium-sized family firms. J. Int. Stud. 2020, 13, 143–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özcan, F.; Elçi, M. Employees’ perception of CSR affecting employer brand, brand image, and corporate reputation. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020972372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Labuschagne, A. Qualitative research—Airy fairy or fundamental? Qual. Rep. 2003, 8, 100–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Landscape of Qualitative Research: Theories and Issues, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin, N.K.; Lincoln, Y.S. The Qualitative Inquiry Reader, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski, M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res. Nurs. Health 2000, 23, 334–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, S.D.; Loiselle, C.G. Combining individual interviews and focus groups to enhance data richness. J. Adv. Nurs. 2008, 62, 228–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irvine, A.; Drew, P.; Sainsbury, R. ‘Am I not answering your questions properly?’ Clarification, adequacy and responsiveness in semi-structured telephone and face-to-face interviews. Qual. Res. 2012, 13, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, F.; Coughlan, M.; Cronin, P. Interviewing in qualitative research: The one-to-one interview. Int. J. Ther. Rehabil. 2009, 16, 309–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, M.; Lewis, P.; Thornhill, A. Research Methods for Business Students, 5th ed.; Pearson Education: London, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston, M. Secondary data analysis: A method of which the time has come. Qual. Quant. Methods Libr. 2014, 3, 619–626. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Available online: https://single-market-economy.ec.europa.eu/smes_en (accessed on 9 October 2022).

- Dollah, S.; Abduh, A.R. Benefits and drawbacks of NVivo QSR application. Adv. Soc.Sci. Educ. Humanit. Res. 2017, 2, 61–63. [Google Scholar]

- Fereday, J.; Muir-Cochrane, E. Demonstrating Rigor Using Thematic Analysis: A Hybrid Approach of Inductive and Deductive Coding and Theme Development. Int. J. Qual. Methods 2006, 5, 80–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyatzis, R. Transforming Qualitative Information: Thematic Analysis and Code Development, 1st ed.; SAGE Publications: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Crabtree, B.; Miller, W. A template approach to text analysis: Developing and using codebooks. In Doing Qualitative Research, 1st ed.; Crabtree, B., Miller, W., Eds.; SAGE Publications: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1999; pp. 163–177. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, J.K.; Daneke, G.A.; Lenox, M.J. Sustainable development and entrepreneurship: Past contributions and future directions. J. Bus. Ventur. 2010, 25, 439–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaosman, H.; Perry, P.; Brun, A.; Morales-Alonso, G. Behind the runway: Extending sustainability in luxury fashion supply chains. J. Bus. Res. 2020, 117, 652–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randstad. Available online: https://workforceinsights.randstad.com/randstad-employer-brand-research-global-report-2022 (accessed on 25 September 2022).

- Petkova, A.; Rindova, V.; Gupta, A. How can new ventures build reputation? An exploratory study. Corp. Reput. Rev. 2008, 11, 320–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Riel, C.B.M.; Fombrun, C.J. Essentials of Corporate Communication, 1st ed.; Taylor and Francis: London, UK, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Koporcic, N.; Törnroos, J.-A. Understanding Interactive Network Branding in SME Firms, 1st ed.; Emerald Publishing: Bingley, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Martdianty, F.; Coetzer, A.; Susomrith, P. Job embeddedness of manufacturing SME employees in Indonesia. Empl. Relat. Int. J. 2020, 42, 180–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montiel, I. Corporate Social Responsibility and Corporate Sustainability Separate Pasts, Common Futures. Organ. Environ. 2008, 21, 245–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latapí Agudelo, M.A.; Jóhannsdóttir, L.; Davídsdóttir, B. A literature review of the history and evolution of corporate social responsibility. Int. J. Corp. Soc. Responsib. 2019, 4, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samoliuk, N.; Bilan, Y.; Mishchuk, H.; Mishchuk, V. Employer brand: Key values influencing the intention to join a company. Manag. Mark. Chall. Knowl. Soc. 2022, 17, 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustamante, S.; Pizzutilo, F.; Martinovic, M.; Herrero Olarte, S. Corporate Social Responsibility and Employer Attractiveness—An International Perspective, 1st ed.; Springer Nature: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H.; Renneboog, L. On the Foundations of Corporate Social Responsibility. J. Financ. 2017, 72, 853–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).