Abstract

Climate change has garnered widespread societal concern due to its yawning consequences on both the natural environment and human society. Consequently, the imperative for adaptation to climate change has become intensely entrenched in the collective psyche of humanity. Traditionally, women have played an indispensable role in climate adaptation processes, yet their invaluable contributions remain unfortunately disregarded and underrepresented. While contemporary financial assistance promotes women’s engagement in climate change adaptation, the coping strategies in real situations are widely varied and are significantly important to discuss. This study endeavors to rectify this gap by identifying and revealing the adaptive strategies of women in response to the vulnerabilities engendered by the multidimensional impacts of climate change. Thus, this study was conducted deploying a mixed research methodology combined with qualitative and quantitative approaches, particularly focus group discussions (FGD), household surveys, and key informant interviews (KII) across three villages in the Nilphamari district of Northwestern Bangladesh. The findings of this study reveal that women have made substantial contributions to adapting to the impacts of climate change through the execution of distinctive saving mechanisms. In facing adversities resulting from climate-induced losses, women exhibit a commendable capacity for adaptation by leveraging their accrued financial reserves as a robust and astute coping mechanism. This study suggests a broader replication of this approach to confront the impacts of climate change.

1. Introduction

In contemporary society, distinctive manifestations of global-scale climate change exert profound influences on humans’ lives and the world, spanning from local to regional and global scales [1,2]. Global climate change, exacerbated by emissions of greenhouse gases, correlates with the escalating severity and frequency of extreme events, such as global warming, sea level rise, seasonal irregularities, storms, drought cycles, and flooding incidents [3]. The urgency in contemporary research stems from the burgeoning concern surrounding these extreme events, primarily driven by climate change. Moran [1] posits that extreme events and natural hazards, while not novel in human history, are distinguished today by their escalating occurrence, amplified by global-scale climate change. Studies like Planton et al. [4] suggest a nuanced perspective: there is not uniform warming everywhere, but rather an increase in the occurrence of extreme events—droughts in some regions and floods in others. The confluence of climate change and the heightened frequency of extreme events exacerbate species decline, impacting crop yield and human health. Subsequently, it imperils fundamental human livelihoods, manifesting as food insecurity, inadequate shelter, energy deficits, water scarcity, and impediments to education and healthcare access—ultimately undermining sustainable development. While the impacts of climate change resonate globally, its effects exhibit spatial heterogeneity due to geographical positioning, socioeconomic conditions, political determinants, poverty levels, and disparities in race and gender [5].

Bangladesh has gained global recognition as one of the most vulnerable nations to climate change [6] due to its geographical nature, low-lying terrain, and high population densities. Vulnerabilities in this context manifest through multiple climate change implications, including flooding, cyclones, sea-level rise, and drought [7,8,9]. The region has already witnessed an upward trajectory in mean temperatures over the past three decades, with projections indicating further increases of 1 °C, 1.4 °C, and 2.4 °C by 2030, 2050, and 2100, respectively [5]. Moreover, the consequences of climate change are intense in the form of extreme natural events—unexpected heavy rains, droughts, late winters, and early summers. The frequency of these extreme natural events, particularly droughts and reduced rainfall, has surged [10,11]. In the northwestern region of Bangladesh, extreme natural events, including heavy rain, irregular precipitation patterns, excessive fog, and droughts, have become recurrent [12], signifying the direct impacts of climate change. Drought, especially, is an enduring challenge, primarily affecting vulnerable northern regions, and over the past half-century, Bangladesh has grappled with over 20 major drought episodes [13]. Climate change, however, increases the severity and frequency of these droughts, further exacerbating the toll on agricultural production [14,15].

Consequently, the imperative of adaptation, defined as the adjustment of natural or human systems in response to current or anticipated climatic stimuli [16], takes center stage in addressing climate change. Moran [1] advocates the Human Adaptability Approach, which addresses specific challenges confronted by inhabitants of diverse ecosystems. This approach underscores the dynamic interplay between human populations, their environment, and their efforts to adapt to environmental challenges. It emphasizes the agency of people in effecting changes, adjustments, and transformations in the physical environment, all while acknowledging that these reciprocal dynamics also reshape individuals themselves. Moran [1] presented evidence supporting the notion that adaptation processes comprise both physiological and cultural aspects.

Women emerge as pivotal agents in climate change adaptation, as shown in different studies around the world adapting different strategies (see [17,18,19]). Moreover, in Bangladesh, several studies show that women adopted different strategies to confront the impacts of climate change. A study on climate change and gender conducted by the Ministry of Environment and Forestry [20] underscored the significant role of rural women in alleviating the impact of climate-related change by engaging in various activities including preparation to store dry food, fuel, and seeds, which also ensures food security. Dankelman et al. [21] found that women adapt by diversifying food production; for instance, they cultivate flood-tolerant local vegetables during and after flooding when traditional crops like rice become untenable, ensuring food security for their families and communities. Further, Islam [22] noted that women alter family diets to enhance food security. In coastal areas, women preserve fish through drying, thus fulfilling protein needs during food shortages caused by climate-induced events and generating supplementary income through surplus sales. Although these studies provide a background of women’s adaptation strategies, their research is not strong enough to understand the country-wide adaptation mechanisms because the predominant focus of major studies is limited to flood events and coastal regions.

In the socio-cultural setting of Bangladesh, women’s substantial economic contributions remain under-recognized [23]. Thus, women are at a heightened risk of experiencing poverty relative to their male counterparts. In the contexts of poverty and prevailing gender roles, responsibilities, and cultural norms, women frequently confront vulnerabilities and burdens stemming from the impacts of climate change [24]. Situations become worsened during extreme climatic events, including droughts, floods, and other climate-induced catastrophes [25].

Although women make substantial contributions to climate change adaptation, discussions surrounding their adaptation strategies remain relatively sparse within scholarly discourse in Bangladesh. To fill the gap, our study attempts to identify the adaptation strategies led by rural women in response to the impacts of climate change. We conducted our investigation within the framework of the women-led Shabolombee Samity (self-help group) in three distinct villages within Jaldhaka Upazila in the Nilphamari district. We deployed a mixed research approach, encompassing both qualitative and quantitative methodologies to comprehensively explore the actions undertaken by women to combat the impacts of climate change.

Climate change is a historical reality requiring appropriate adaptive mechanisms to confront its impacts. This investigation provides an important insight into women-led climate change adaptation for the global south.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

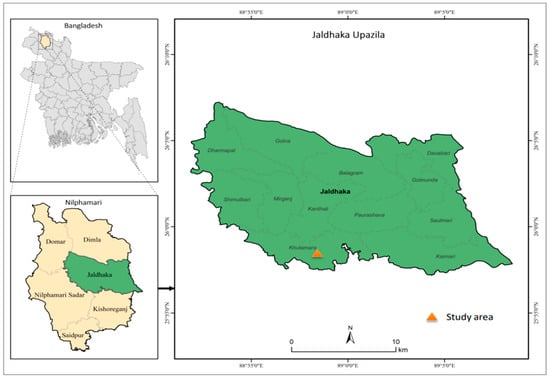

This research was conducted with small and medium women farmer families in Madrashapara, Kamarpara, and Baroipara villages in the Jaldhaka Upazila of the Nilphamari district in Northern Bangladesh (see Figure 1). This area is vulnerable to climate change and extreme natural events, including heavy rainfall, erratic precipitation patterns, excessive fog, droughts, and flash floods (see [12,26,27]), indicating the direct impacts of climate change.

Figure 1.

Location map of the study area (Madrashapara, Kamarpara, and Baroipara villages within Khutamara Union, Jaldhaka Upazila, Nilphamari district in Bangladesh) adopted from Rahman et al. [12].

Similar to the other regions of the country, agriculture covers major sources of livelihood for both men and women in this area. Apart from agriculture, men are engaged in daily wage-based labor, construction work, rickshaw/auto van pulling, and business. Some individuals also pursue various urban activities. In contrast, women primarily engage in agriculture and agricultural-related wage-based activities, while others perform household chores, work in artificial hair manufacturing, or engage in sewing. Notably, women in household chores face extended periods of unemployment and lack extracurricular activities beyond their homes [12].

Farmers depend on traditional farming methods alongside modern techniques. Crops like rice, jute, potatoes, and tobacco are staples, with maize gaining popularity. Villagers also grow vegetables and raise cattle, goats, and chickens. Seasonal unemployment, lasting four months in April–May and October–November, creates vulnerability. Extreme natural events like droughts and irregular rainfall affect crop production, particularly during the dry season [12].

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

The research has been conducted on the Shabolombee Samity (self-help group) of the Unnayan Shahojogy Team (UST) project deploying a mixed research approach, referring to the use of two or more methods in a single research, including qualitative and quantitative approaches to increase the accuracy and level of confidence [28,29,30,31] in three different villages of Jaldhaka Upazila located in Northwestern Bangladesh. Data were collected from women farmers who are members of the Shabolombee Samity through household surveys and focus group discussions (FGD) from April 2022 to March 2023.

In 2001, a targeted intervention strategy was introduced with the establishment of a women’s forum known as a Shabolombee Samity (self-help group). This initiative was facilitated by the Unnayan Shahojogy Team (UST), a local NGO, in eight distinct villages covering two unions, namely Kathali and Khutamara Union, with the primary aim of enhancing the savings practices among the local residents. The cumulative membership across these eight distinct groups amounted to 1200 women. These women, predominantly engaged in agricultural pursuits, were provided with the necessary support mechanisms to foster secure savings practices, creating an enabling environment. Notably, the intervention facilitated by the UST was instigated by the observance of localized, fragmented savings practices among women in the study area. The UST, instead, consolidated these individual practices into a collective framework, fostering a supportive environment and cultivating trust among the community members.

However, it became evident that the implementation of these services resulted in an important economic empowerment of women farmers. This empowerment was marked by the alleviation of adverse consequences and vulnerabilities stemming from climate change and various uncertainties. Building upon the achievements of this earlier endeavor, a similar project was replicated two decades later in 2021. This subsequent phase extended its reach to five villages, encompassing 800 women members, situated within the same unions. The overarching objectives of this undertaking remained centered on the establishment of secure and enabling paths for savings among rural women. This was envisaged as a strategic response to address uncertainties, economic shocks, and adverse impacts induced by the dynamic forces of climate change. It is noteworthy that membership eligibility for the savings group was contingent upon the applicant’s status as a married woman above the age of 25 years. This criterion was established to ensure the targeted inclusion of a specific demographic segment within the initiative. This study was conducted among the 311 women farmers from three different villages of Khutamara Union who have been actively involved in the self-help group both in 2001 and 2021.

To comprehensively comprehend the experiences of women in relation to the impacts of climate change and their corresponding adaptive strategies, our research adopted a multi-layered methodological approach. This approach incorporated group discussions, focus group discussions (FGD), household surveys, and key informant interviews (KII).

The initial phase of data collection involved group discussions and focus group discussions, conducted using checklists. We conducted four focus group discussions among 48 women consisting of 12 members in each. These discussions were primarily oriented toward exploring the respondent’s views of the climate change scenario in the study area. The topics covered during these discussions comprised a range of dimensions, including socio-economic information, experiences related to climate change and its associated impacts, and the adaptive practices employed by women to confront the consequences of climate change. Women confirmed that they introduced savings as a strategy for climate change adaptation, which was later facilitated by the UST. The insights garnered from these discussions highlighted the predominant role of agriculture in the area, underscoring that climate change disproportionately affected crop production compared to other economic sectors. Hence, following the preliminary observations acquired from these focus group discussions and group discussions, we outlined the principal thematic domains of the survey questionnaire. These areas encompassed the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents, the amount of crop loss experienced by respondents, women’s adaptive strategies for addressing climate change impacts, and their sources of savings, among other pertinent aspects. Surveys were undertaken to quantify the losses incurred as a result of climate change impacts and ascertain the numerical recovery rate through savings accumulated from the Shabolombee Samity. Additionally, KIIs were conducted with individuals closely associated with the projects, offering valuable insights into the initiatives and their outcomes. The research employed both open-ended questionnaires for group discussions, FGDs, and KIIs, while semi-structured questionnaires were utilized for household surveys.

Our research adhered to rigorous ethical protocols, with both verbal and written consent being obtained from all participants. Furthermore, a commitment to safeguarding the privacy and confidentiality of the respondents throughout the research dissemination process was assured. We anonymized their identities, thus upholding their confidentiality.

The data obtained from the focus group discussions, accurately recorded and supplemented with comprehensive notes, were transcribed into textual format. These data were then analyzed using traditional qualitative data analysis software (N-Vivo, Version 20, Melbourne, Australia) [10,31]. The analysis process adopted an inductive approach, systematically identifying and extracting emergent themes embedded within the FGD data. Simultaneously, the data stemming from the household surveys underwent a distinct analytical path. Employing Microsoft Excel, computer software dedicated to data analysis, a thorough investigation of the household survey data was conducted to quantify the losses incurred and the recovery rates achieved through savings mechanisms.

3. Results

3.1. Climate Change Scenario in the Study Area

All respondents to this study asserted that the climate has changed over time, with observable consequences. Numerous consequences of this climatic change include early and lengthy summer days, shorter and warmer winters (warmer than in previous decades), sudden and heavy rainfall, irregular rainfall, rainstorms, winter fogs, and droughts. The prevalent agrarian dominance of the region is intricately dependent on the prevailing natural settings. Hence, extreme natural events caused by climate change have an effect on agricultural production, as stated by all 311 respondents.

3.2. Women-Led Climate Change Adaptation

Women inhabitants of the rural villages have exhibited proactive involvement in addressing the recurring effects of climate change. This engagement is accentuated by their initiation of concerted efforts towards financial preparedness aimed at adapting to the adverse impacts hastened by climatic changes. A noteworthy cohort comprising 144 women in 2003 and 183 women in 2023 among 311 was directly affected by the damaging consequences of climate change, as confirmed by the members of Shabolombee Samity and KII respondents. Farmers experienced crop losses due to various climatic factors such as droughts, dense fog, and extreme weather events. These women carefully draw upon the funds accrued within their designated savings to ameliorate the financial strains imposed by such adversities. This reservoir of funds, colloquially termed Shabolombee Savings (self-help savings), represents an adaptive strategy that transcends the variability of climate change impacts, as not every growing season witnesses the exact extent of crop production impairment. Consequently, during adversity and vulnerability, the Shabolombee Savings mechanism serves as a crucial buffer to rectify the prevailing financial uncertainties.

3.2.1. Saving System

Women primarily introduced the saving practices for managing the uncertainties produced by climate change. It was initially practiced in a small group. Later, the Shabolombee Somity, a self-help group, was established by the Unnayan Shahojogy Team (UST), a local NGO, as an institutionalized process to facilitate small group practices in the larger community in the years 2001–2003. Further, it was reintroduced in 2021. Within this organizational framework, a designated collector was appointed from among the group members, referred to as savers, tasked with the responsibility of gathering financial contributions from fellow members.

The collector diligently interacted with the group members on a daily basis, six days a week, to facilitate the collection process. During these interactions, members were given the autonomy to deposit any amount of their choosing, and there was no obligation to make a deposit if one did not have funds available on a particular day. This flexible approach aimed to accommodate the financial circumstances of all participants.

Additionally, the group design allowed for withdrawals at the discretion of the members, without imposing any restrictions on the withdrawal amount or frequency within her savings. Importantly, members were granted immediate access to their withdrawal funds, and no fees or charges were levied for availing of this service. This structure was designed to foster a supportive and inclusive environment within the Shabolombee Somity, enabling individuals to manage their financial resources with ease and without undue financial burdens.

3.2.2. Sources of Savings

This research endeavors to examine the socioeconomic engagement and savings behaviors of women residing in three distinct rural villages. Primarily, women in these locales are engaged in agricultural pursuits, encompassing poultry farming, livestock rearing, and vegetable cultivation. Drawing upon primary data gathered through surveys, this study elucidates the diverse sources of savings among these women. The identified avenues include income derived from livestock and poultry rearing activities, the surplus income remaining after daily expenses, earnings from the artisanal craft of nakshi kantha production, and economizing through the reduction in expenditures.

3.2.3. Savings as a Climate Change Adaptation Mechanism

In our study, we investigated how women in three different villages, namely Kamarpara, Madrasapara, and Baraipara, perceived and dealt with the impact of extreme natural events on their crop production during the years 2003 and 2022. We also investigated, if crops were lost or damaged impacted by climate change, how they dealt with the losses.

Table 1 shows that in 2003, women in Kamarpara reported that 43 women’s families experienced crop losses due to these extreme natural events. By 2022, this number had increased to 59 families. Similarly, in Madrasapara, 47 families faced crop losses in 2003, which rose to 69 in 2022. In Baroipara, 54 women encountered crop losses in 2003, which slightly decreased to 56 in 2022.

Table 1.

Crop loss scenario resulting from extreme natural events and the recovery rate from Shabolombee savings.

Women in all three villages relied on their savings in the Shabolombee Samity to recover their crop losses. In Kamarpara, 29 women were able to recover losses through this savings group in 2003, which increased to 36 in 2022. In Madrasapara, 32 women recovered their losses in 2003 through the Shabolombee Somity, which also increased to 38 in 2022. In Baroipara, 31 women recovered losses through this savings group in 2003, but this number decreased slightly to 29 in 2022.

Only a small percentage of women in these villages recovered their losses through other sources such as banks or NGOs. In Kamarpara, one woman used these alternative sources to recover losses in both 2003 and 2022. In Madrasapara, one woman used this option in 2003, and it increased to four in 2022. In Baroipara, two women utilized other sources in 2003, and this increased to seven in 2022.

Some women resorted to loans from NGOs to recover their losses. In Kamarpara, five women used NGO loans for recovery in 2003, which increased to nine in 2022. In Madrasapara, 10 women used this option in 2003, and it slightly increased to 12 in 2022. In Baroipara, 12 women used NGO loans for recovery in 2003, and it decreased to 8 in 2022.

Despite their efforts, some women were unable to recover their crop losses. In Kamarpara, eight women could not recover losses in 2003, which remained the same in 2022. In Madrasapara, 4 women faced this issue in 2003, which increased to 15 in 2022. In Baroipara, 9 women could not recover losses in 2003, which increased to 12 in 2022.

According to the study findings, in 2003, among 311 women respondents, 144 women’s families faced crop losses due to the extreme natural events. Among 144 women, 92 woman farmer’s families were able to recover losses and manage the uncertainties and vulnerabilities with the money they saved in Shabolombee Samity and the recovery rate was approximately 64 percent. Further, in 2022, 183 women’s families faced crop loss due to the extreme natural events and 103 women could recover themselves from their savings in Shabolombee Samity (recovery rate is about 56 percent).

These findings highlight the challenges women face in recovering from crop losses caused by extreme natural events and underscore the importance of savings groups and alternative sources in building adaptive capacity to such events, particularly in the context of climate change adaptation.

3.2.4. Why Did Microcredit Fail to Cope with Uncertainties Generated by Climate Change?

Our study revealed that although microcredit organizations provided loans and created savings opportunities for the villagers, they were not effective in managing uncertainty generated by the impacts of climate change claimed by 165 women. In total, 133 respondents claimed that instead of managing uncertainties with the loans and savings from microcredit organizations, they created a burden. When we asked why were credits or savings in microcredit organizations not effective in managing the losses generated by the impacts of climate change, the respondents of FGD-4 claimed,

“When engaging in microcredit borrowing, it often engenders financial burdens in numerous instances. In our village, we have observed cases that in the aftermath of crop damage caused by severe natural events such as heavy rainfall, rainstorms, and droughts, a substantial portion of rural inhabitants take loans as a means of adaptation to their incurred losses. These individuals repay the loans (taken from microcredit organizations) taking conditional credits from the non-institutional lenders, comprising neighbors, relatives, or traditional village money lenders. They commit to the lenders (outside of microcredit organizations) that they will pay their loans after getting the crops in the next season (i.e., the season immediately following the crop damage event). However, when subsequent crop losses transpire in successive seasons, rendering them incapable of settling the debts accrued from these external lenders, they are confronted with the necessity of securing further financial assistance, either from non-institutionalized sources or microcredit organizations.”

Echoing the same statements, respondents 1, 4, 5 and 7 of FGD 2 stated,

“If someone borrows loan from microcredit organization, s/he is supposed to borrow it twice, thrice or many more”.

While asking about the savings in microfinance organizations, all the respondents of FGD 1, 2 and 3 claimed,

“It is very difficult to withdraw the money saved in microcredit NGOs because it is a long bureaucratic process. If we need money for instant gratification or urgent needs, we cannot withdraw money immediately. Moreover, the savings are collateral.”

4. Discussion

The study revealed that climate changes caused crop damage for the farmers, and the frequencies of the damages have increased over the last few decades due to irregular rain, heavy rain, seasonal change (early and long summer days, late and short winter days), and frequent droughts. Our study replicates the other studies conducted in the diverse regions in national and international contexts (see [12,16,32,33,34]).

Women, across diverse global contexts, exhibit a remarkable capacity for adapting to the challenges posed by climate change. This adaptability is underlined by the utilization of various strategies, as elucidated by existing research. According to Mitchell et al. [17], women farmers have demonstrated a proactive response to the unpredictable weather patterns associated with climate change. They conducted this by implementing a strategy that involves cultivating off-season vegetables and bananas. This strategic shift reduces the risk of crop failure, a consequence often precipitated by climatic events such as floods and droughts. Moreover, Al-Nabel’s study [18] reinforces the notion that women contribute significantly to climate change mitigation efforts. Evidence suggests that women’s active participation in the management of small-scale irrigation projects, coupled with their involvement in water harvesting and soil conservation activities, yields tangible benefits by enhancing the effective utilization of water resources. This multifaceted engagement underscores their pivotal role in addressing the challenges posed by shifting environmental conditions. The study by Matindra [19] sheds light on the evolving gender roles in the context of climate-change-induced migration. Prolonged absences of men from their households, attributed to migration, precipitate a noteworthy shift in responsibilities. In such circumstances, women assume crucial roles, including cattle herding and pasture maintenance. This transformation underscores women’s adaptability in responding to climate-induced disruptions. Within the specific context of Bangladesh, women emerge as fundamental agents in adapting to the impacts of climatic phenomena such as floods, cyclones, and storms. Their contributions are multifaceted, encompassing the preparation and preservation of essential resources, including dry food, fuel, fodder, seeds, and medicine. Additionally, women employ portable mud stoves during critical climate-related events, as recognized by the Ministry of Environment and Forest, Bangladesh [20]. These adaptive strategies exemplify the multifunctional role that women play in safeguarding their communities from climate-related challenges. A significant revelation arising from this collective body of research is the significant contributions women make to society in the face of climate-change-induced uncertainties. Their proactive responses serve as a cornerstone in building climate change adaptation within their communities. Empirical evidence further supports the involvement of women in climate-related initiatives across various global locations, with a striking illustration of women’s own forms of financial management through the savings facilitated by the Shabolombee Samity, a self-help group. This experiment underscores the vital role of women in climate change adaptation endeavors, transcending geographical boundaries and exemplifying their invaluable contributions to global sustainability efforts.

As posited in the scholarly domain, microcredits can assist impoverished individuals and vulnerable populations worldwide in adapting to climate change. This assistance is achieved by granting access to financial resources, enabling the accumulation and effective management of assets and capabilities. Consequently, individuals and households are empowered to reduce their susceptibility to various shocks and stresses and effectively cope with the impacts of climate change [35]. Nevertheless, microcredit is working as an adaptive tool for combating the financial strains produced by climate change. The respondents argue that the intricate bureaucratic and institutional processes of microcredit organizations make it exceedingly challenging to sustain oneself solely through loans or savings. The study findings suggest that individuals who obtain loans from microcredit organizations are required to commence loan repayment within one week. Furthermore, it is pertinent to note that a distinct fraction of the loan’s principal is set aside by the financial institution in the capacity of a reserved fund on a weekly basis, subject to a collateral requirement. In the case that depositors seek to execute a withdrawal of these accrued savings, they encounter an impediment, as any failure to fulfill the loan repayment obligations will lead to an automatic deduction of a specified portion from the reserved funds, serving as a mechanism for loan repayment. Further, Cons and Paprocki [36] documented that the failure to meet the loan repayment obligations resulted in a heightened tendency for violent incidents and instances of physical and sexual abuse. Incidents of unauthorized asset repossession, including removing the roofs from the residences of loan recipients, were also observed. On the contrary, according to the assertions made by the respondents, the act of depositing funds into the Shabolombee Samity is purportedly devoid of bureaucratic intricacies and does not entail any conditional requirements. There are no limitations on the quantity of savings, allowing individuals to save as much as they choose and at their discretion. During the withdrawal procedure, members have the ability to withdraw their savings at any time of the day, and the transaction is completed promptly.

Furthermore, climate change adaptation is closely related to human psychology and it plays a crucial role [37]. According to the findings of the focus group discussion (FGD) participants, the possession of savings within a family can provide family managers with the necessary fortitude and psychological adaptation to cope with the adverse consequences arising from climate change. Individuals who borrow funds from alternative sources may experience psychological vulnerability due to the strain of debt payback. Karim’s [38] research described that the inability to fulfill debt repayment obligations culminated in instances of borrower suicide. When crop productions experience damage in two consecutive seasons, it exacerbates their economic and psychological vulnerabilities, hence increasing the likelihood of facing difficulties related to loans. On the other hand, Shabolombee Savings are regarded as a form of “safe savings” due to their governance by the members of the Samity. According to the project directors, the saving process is fully dependent on the members, who have the freedom to save and withdraw funds without any external interference. Women are mostly responsible for exerting control over it in a manner that aligns with their own preferences, while we have merely established an enabling environment to facilitate the women’s efforts.

Although women’s savings through the Shabolombee Samity have fostered climate change adaptation, it is essential to recognize that this initiative represents only a localized adaptive mechanism confined to a specific geographic region. In light of this, this study suggests that to determine its universal applicability and assess its sustainability, there is a compelling need for establishing and evaluating Shabolombee Samities in diverse regions.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this research explicate the insightful impact of climate change on agriculture and the indispensable role of women in adapting to its effects. Our study corroborates previous national and international research, underscoring the universal nature of the challenges posed by climate change for farmers. Irregular rain patterns, heavy rain, seasonal shifts, and frequent droughts have collectively heightened the frequency and severity of crop damage. The research also highlights women’s significant contributions to society in the face of climate-change-induced uncertainties. Their adaptive capacity and proactive responses are cornerstones in building climate change adaptation within their communities.

Although microcredit programs could be a valuable tool in assisting vulnerable populations in adapting to climate change by providing access to financial resources, the bureaucratic and institutional intricacies of such programs can pose challenges for independent actions to adapt to climate change. Nevertheless, this research underscores a compelling imperative—the necessity for flexible and autonomous financial mechanisms, demonstrated by the Shabolombee Savings initiative. These mechanisms empower individuals and households, enabling them to organize resources and fortify their capacity to cope effectively with the multidimensional impacts of climate change. This study posits that the successful implementation of such practices in this geographical context should not be regarded as an isolated effort but rather as a prototype worthy of imitation in other regions of the country. The imperative lies in the systematic replication and evaluation of these practices across diverse settings, thereby facilitating the quantification of their sustainability and efficacy in fostering adaptive mechanisms against the challenges posed by climate change.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M.R. and H.H.; methodology, M.M.R., H.H. and M.A.H.; software, M.M.R.; validation, M.M.R. and H.H.; formal analysis, M.M.R., H.H. and M.A.H.; investigation, M.M.R., H.H. and M.A.H.; resources, M.M.R.; data curation, M.M.R., H.H. and M.A.H.; writing—original draft preparation, M.M.R.; writing—review and editing, M.M.R., H.H. and M.A.H.; visualization, M.M.R.; supervision, M.M.R., H.H. and M.A.H.; project administration, M.M.R., H.H. and M.A.H.; funding acquisition, M.M.R., H.H. and M.A.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project was funded by the Institute for Advanced Research (IAR) of the United International University, Bangladesh (Project Code: IAR/01/19/BE/08).

Institutional Review Board Statement

This research was carried out in strict adherence to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and obtained ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Institute for Advanced Research at United International University, denoted by the approval code IAR/01/19/BE/08, dated 1 January 2022.

Informed Consent Statement

All participants in the study provided their informed consent prior to their involvement in the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Moran, E.F. Human Adaptability: An Introduction to Ecological Anthropology; Routledge: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Alston, M. Women and adaptation. WIREs Clim. Chang. 2013, 4, 351–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajkhowa, S.; Sarma, J. Climate change and flood risk, global climate change. In Global Climate Change; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 321–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Planton, S.; Déqué, M.; Chauvin, F.; Terray, L. Expected impacts of climate change on extreme climate events. Comptes Rendus Geosci. 2008, 340, 564–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran-Nantes, Y.; Roy, S. Gender, climate change, and sustainable development in Bangladesh. In Balancing Indi-Vidualism and Collectivism: Social and Environmental Justice; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 163–179. [Google Scholar]

- Alam, G.M.M. Livelihood Cycle and Vulnerability of Rural Households to Climate Change and Hazards in Bangladesh. Environ. Manag. 2017, 59, 777–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahman, M.M.; Ahmad, S.; Mahmud, A.S.; Zaman, H.U.; Nahian, M.A.; Ahmed, A.; Nahar, Q.; Streatfield, P.K. Health consequences of climate change in Bangladesh: An overview of the evidence, knowledge gaps and challenges. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Clim. Change. 2019, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.A.; Imran Reza, M.; Rahman, S.; Kayes, I. Climate change and its impacts on the livelihoods of the vul-nerable people in the southwestern coastal zone in Bangladesh. In Climate Change and the Sustainable Use of Water Resources; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 237–259. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawala, S.; Ota, T.; Ahmed, A.U.; Smith, J.; Van Aalst, M. Development and Climate Change in Bangladesh: Focus on Coastal Flooding and the Sundarbans; OECD: Paris, France, 2003; pp. 1–49. [Google Scholar]

- Hossen, M.A.; Benson, D.; Hossain, S.Z.; Sultana, Z.; Rahman, M. Gendered Perspectives on Climate Change Adaptation: A Quest for Social Sustainability in Badlagaree Village, Bangladesh. Water 2021, 13, 1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A.R.M.T.; Shen, S.; Hu, Z.; Rahman, M.A. Drought Hazard Evaluation in Boro Paddy Cultivated Areas of Western Bangladesh at Current and Future Climate Change Conditions. Adv. Meteorol. 2017, 2017, 351438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.; Huq, H.; Hossen, M.A. Patriarchal Challenges for Women Empowerment in Neoliberal Agricultural Development: A Study in Northwestern Bangladesh. Soc. Sci. 2023, 12, 482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, N.; Chowdhury, S.; Paul, S.K. Farmer-level adaptation to climate change and agricultural drought: Empirical evidences from the Barind region of Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards 2016, 83, 1007–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goosen, H.; Hasan, T.; Saha, S.K.; Rezwana, N.; Rahman, R.; Assaduzzaman, M.; Van Scheltinga, C. Nationwide Climate Vulnerability Assessment in Bangladesh. Final Draft. 2018. Available online: https://moef.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/moef.portal.gov.bd/notices/d31d60fd_df55_4d75_bc22_1b0142fd9d3f/Draft%20NCVA.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- Salam, R.; Islam, A.R.M.T.; Shill, B.K.; Alam, G.M.M.; Hasanuzzaman; Hasan, M.; Ibrahim, S.M.; Shouse, R.C. Nexus between vulnerability and adaptive capacity of drought-prone rural households in northern Bangladesh. Nat. Hazards 2021, 106, 509–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayers, J.; Huq, S.; Wright, H.; Faisal, A.M.; Hussain, S.T. Mainstreaming climate change adaptation into development in Bangladesh. Clim. Dev. 2014, 6, 293–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, T.; Tanner, T.; Lussier, K. ‘We Know What We Need’: South Asian Women Speak Out on Climate Change Adaptation. 2007. Available online: https://actionaid.org/publications/2007/we-know-what-we-need-south-asian-women-speak-out-climate-change-adaptation (accessed on 15 September 2023).

- Al-Naber, S.; Shatanawi, M. The Role of Women in Irrigation Management and Water Resources Development in Jordan. Integration of Gender Dimension in Water Management in the Mediterranean Region: INGEDI Project. Bari: CIHEAM. 2004. Available online: https://om.ciheam.org/article.php?IDPDF=6002407 (accessed on 22 July 2023).

- Matinda, M.Z. Maasai Pastoralist Women’s Vulnerability to the Impacts of Climate Change: A Case Study of Namalulu Village, Northern Tanzania. In Proceedings of the Global Worksh Seminar on Indigenous Women, Climate Change and Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD+), Mandaluyong City, Philippines, 18–19 November 2010. [Google Scholar]

- MoEF (Ministry of Environment and Forest). Bangladesh Climate Change and Gender Action Plan. Government of the People’s Republic of Bangladesh, 2013, pp. 1–122. Available online: http://nda.erd.gov.bd/files/1/Publications/CC%20Policy%20Documents/CCGAP%202009.pdf (accessed on 17 August 2023).

- Dankelman, I.E.M. Gender, Climate Change and Human Security Lessons from Bangladesh, Ghana and Senegal. 2008. Available online: https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/72456/72456.pdf (accessed on 19 July 2023).

- Islam, M.R. Vulnerability and coping strategies of women in disaster: A study on coastal areas of Bangladesh. Arts Fac. J. 2012, 4, 147–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, A.; Naser, K.; Zaman, A.; Nuseibeh, R. Factors influencing women business development in the developing countries: Evidence from Bangladesh. Int. J. Organ. Anal. 2009, 17, 202–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alfthan, B.; Skaalvik, J.; Johnsen, K.; Sevaldsen, P.; Nellemann, C.; Verma, R.; Hislop, L. Women at the Frontline of Climate Change: Gender Risks and Hopes. 2011. Available online: https://policycommons.net/artifacts/2390408/women-at-the-frontline-of-climate-change/3411682/ (accessed on 17 July 2023).

- Tanny, N.Z.; Rahman, M.W. Climate Change Vulnerabilities of Woman in Bangladesh. Agric. 2017, 14, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sultana, N.; Rayhan, I. Coping strategies with floods in Bangladesh: An empirical study. Nat. Hazards 2012, 64, 1209–1218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.A.; Bijoy, M.R.; Chakraborty, T.R.; Imrul Kayes, A.S.M.; Rahman, M.A.; Leal Filho, W. Climate in-formation services and their potential on adaptation and mitigation: Experiences from flood affected regions in Bangladesh. In Handbook of Climate Services; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 481–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelle, U. Sociological explanations between micro and macro and the integration of qualitative and quantitative methods. Hist. Soc. Res. 2005, 30, 95–117. [Google Scholar]

- Alexander, V.D.; Thomas, H.; Cronin, A.; Fielding, J.; Moran-Ellis, J. Mixed methods. Res. Soc. Life 2008, 3, 125–144. [Google Scholar]

- Knappertsbusch, F.; Langfeldt, B.; Kelle, U. Mixed-methods and multimethod research. In Soziologie-Sociology in the German-Speaking World; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2021; pp. 261–272. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.; Huq, H.; Mukul, S.A. Implications of Changing Urban Land Use on the Livelihoods of Local People in Northwestern Bangladesh. Sustainability 2023, 15, 11769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, M.A.; Rahman, M.M.; Hossain, M.S. Climate-resilient agricultural practices in different agro-ecological zones of Bangladesh. In Handbook of Climate Change Resilience; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.M.; Zulfiqar, F.; Datta, A.; Kuwornu, J.K.M.; Shrestha, S. Analysing the variation in farmers’ perceptions of climate change impacts on crop production and adaptation measures across the Ganges’ Tidal Floodplain in Bangladesh. Local Environ. 2022, 27, 968–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, N.K. Impact of climate change on agriculture production and its sustainable solutions. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 2, 95–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammill, A.; Matthew, R.; McCarter, E. Microfinance and Climate Change Adaptation. IDS Bull. 2009, 39, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cons, J.; Kasia, P. “The Limits of Microcredit–A Bangladesh Case.” Food First Backgrounder 14. 2008. Available online: https://archive.foodfirst.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/BK14_4-microcredit-winter-2008.pdf (accessed on 11 October 2023).

- Bradley, G.L.; Reser, J.P. Adaptation processes in the context of climate change: A social and environmental psychology perspective. J. Bioeconomics 2016, 19, 29–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, L. Microfinance and its Discontents: Women in Debt in Bangladesh; U of Minnesota Press: Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).