Abstract

The study of urban resilience (UR) in the context of sustainable development (SD) is a relatively new chapter, so we give it our full attention in this article. We seek to link UR and SD by understanding the complexity of current anthropogenic hazards—more precisely, global consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic and war in Ukraine. In our study, we go a step further and create a hypothetical model based on hazards that links the key factors of UR and SD. We set the following two objectives: whether and how research incorporates newly perceived conceptual hazards (pandemic, war) and whether all groups of factors are explored equally and simultaneously. As these two hazards have only recently emerged and research on the subject is still well underway, we have opted for a systematic review method. We focused on articles from 2019 to 2022. The study showed that newly perceived conceptual tensions (pandemic, war) related to UR and SD have not been adequately explored. The study confirmed the lack of existing research in the broader context of understanding resilience of the built environment, and thus the lack of studies that provide a foundation and perspective for SD of the built environment. Therefore, we believe that further research should specifically focus on the plurality of approaches to understand the complex interactions, their impacts, and feedbacks in the context of multidimensional urbanization to understand UR as a perspective for SD.

1. Introduction

The resilience of urban environments to ecological, socioeconomic, and political uncertainties has been the subject of sustainable development (SD) research for some time [1,2]. The term resilience originates from physics and refers to the property of a substance or system to return to its original position after deformation [2]. The concept was used as early as 1973 to define the ability of a natural ecosystem to recover from natural disasters. Since then, the concept has been widely used in the field of urban research, especially in the field of SD of urban settlements, as a promising paradigm to promote disaster risk reduction [3]. Urban settlement resilience, or so-called urban resilience (UR), almost always has a positive connotation that emphasizes the adaptive capacity of the local community (technical, organizational, social, and economic resilience), the flexibility of the socioeconomic paradigm (social, economic, physical, and human capital), and the physical resilience of the built environment (natural capital, physical characteristics of the environment, resource stability, and infrastructure) [4]. The main objective of UR is to reduce the consequences of disturbances originating from different sources [5].

The concept of resilience encompasses processes related to both natural (e.g., earthquakes, hurricanes, cyclones, drought) and anthropogenic hazards, such as human errors or malicious attacks [5,6]. Existing studies in the field of UR focus mainly on the capacity of communities to adapt to natural disasters in the context of climate change (e.g., [7,8,9,10,11,12]), but there are fewer such studies focused on public health concerns such as pandemics [13] and very few concerning physical aggression or war [14]. The COVID-19 pandemic has encouraged researchers to explore resilience, but mainly from the perspective of human capital resilience, social capital resilience, and system (risk) management. The COVID-19 pandemic is one example of a completely unexpected risk, which triggered health, social, and economic consequences for cities, higher unemployment rates, changing attitudes toward public spending, accessibility of public services and public facilities, mobility, infrastructure, etc. [15,16]. However, other aspects of UR remain unexplored, such as spatial elements and institutional and sociocultural contexts, which also have a strong influence on UR [13]. Therefore, the aim of our study is to respond to the lack of existing research in the broader context of SD of the built environment and to identify a clear perspective on SD of the built environment considering UR.

Some authors [10,17] define UR as a dynamic urban process which consists of four categories: urban ecological resilience, urban hazards and disaster risk reduction, resilience of urban and regional economies, and promotion of resilience through urban governance and institutions. Ref. [17] summarized the key factors into four main categories: environmental quality (air quality, environmental factors, and water quality), socioeconomic impacts (social and economic impacts), management and governance (governance, smart cities, etc.), and transportation and urban design.

Talking about anthropogenic hazards, not only COVID-19, but also political instability or even physical aggression on the urban environment (war in Ukraine) affect the resilience of the built environment. Cities have political, economic, and symbolic value, so even an aggressor seeking to undermine an attacked country’s political stability, economic vitality, and social stability will find cities attractive targets. On the other hand, cities offer considerable advantages to defenders by serving as sanctuaries, surveillance, and reconnaissance platforms, turning them into fortresses. All aggression leads to migration. Although the phenomenon of migration is not a new problem, with its different patterns, it is becoming a force that has significant implications for urbanization due to its complexity and rapid changes in origin, transit, and destinations [18]. Inter-racial conflicts, political conflicts, war situations, etc., bring instability and insecurity to urban settlements. They create risks in different dimensions that not only affect the demographic, social, environmental, and economic structure of the city, but also put pressure on the urban macrostructure. Research on the impact of the 2011 war in Libya found that urban residents developed stronger resilience strategies economically through job creation [19]. The study also found that in response to spatial resilience, Benghazi residents have gradually begun to build homes on the outskirts of the city, which in turn puts pressure on the pristine natural environment near the cities [19]. A host of studies have examined the vulnerability of the demographic structure of urban settlements by looking at differences in fertility or mortality rates before and after the war [20,21]. As Ref. [22] notes, the 1992 war between Serbia and Bosnia, as a sudden and violent change in the urban situation, led to a new spatial organization, a new understanding of the urban environment, and new patterns of movement and traffic, and drastically altered patterns and rhythms within the urban fabric [22]. Several studies have looked at the consequences of migration of people from conflict areas to safer urban areas (e.g., [23,24]).

Ref. [25] suggested examining the concept of UR in the context of five dimensions: physical (e.g., infrastructure), natural (e.g., ecological and environmental resilience), economic (e.g., social and economic development), institutional (e.g., political governance and management), and social (e.g., communication among people, coexistence in general). Ref. [2] states that the resilience of cities rests on four basic pillars: resist, recover, adapt, and transform. However, as Ref. notes, all theories generally agree that UR has two main objectives: to adapt to the hazardous situation and to mitigate the unexpected stresses on the exposed population. Moreover, as Ref. [26] states in the conclusion of their study reviewing the literature on UR, future studies need to incorporate the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on issues such as health, logistics, supply chains, and other elements related to UR. However, as Ref. [26] points out, all theories generally agree that the two main goals of UR are to adapt to new and difficult situations and to mitigate unexpected stresses for those affected. They argue that future studies of UR should include the COVID-19 pandemic and its impact on issues such as health, logistics, supply chains, and other elements related to UR. Ref. notes that although the concept of UR has been closely linked to the field of ecology until recently, the concept has expanded to include many different fields, such as psychology, social sciences, education, urban safety, policy and governance, disaster risk management, economics, etc. Interestingly, Ref. [27] already pointed out the importance of the link between UR and future urban development through the three basic phases of disaster risk response mentioned above, namely response, recovery, and future development work.

2. Research Model Concept

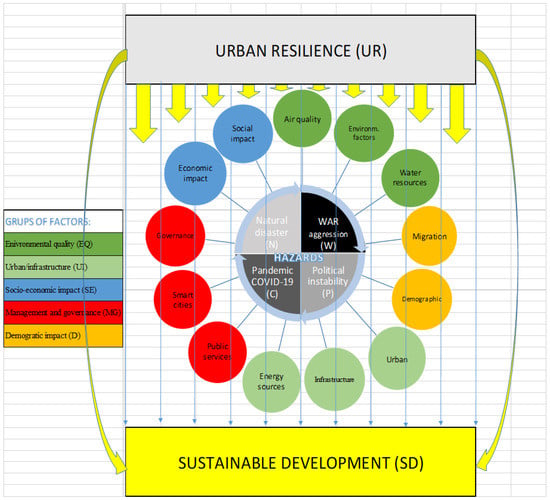

In our study, we go a step further and create a hypothetical model that links the key areas of UR and SD (Figure 1). The model serves as a transparent basis for further research. We place natural and anthropogenic hazards [5,6] at the center of the model, which are further subdivided according to current hazards, namely COVID-19 and the war in Ukraine. All these hazards require accelerated mobilization of various UR factors. We grouped these factors into the following five categories: environmental impact (EI; air quality, water resources, environmental factors, etc.), infrastructure impact (UI; urbanization, infrastructure transformation, energy supply, etc.), socioeconomic development (SE; social and economic impacts due to the changing global context), management and governance (MG; public services and governance of countries), and demographic impact (D; aging population, migration, increasing poverty, etc.). The model assumes that all these factors must be considered equally to achieve adequate UR development in today’s world. We see UR as a perspective for the SD of the entire built environment.

Figure 1.

A hypothetical model of UR and SD factors in times of health (COVID-19) and human-induced malicious (global consequences of the war in Ukraine) hazards.

Based on the hypothetical model developed in Figure 1, we conducted a systematic literature review over the past three years (2019–2022). We were interested in whether the research perceives UR and the perspective of SD of the built environment in the puddle of these new, previously unforeseen impacts in the past three years, i.e., in a period of pronounced impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic and war on European soil.

The aim of our study is to identify the most relevant and influential research on the UR–SD nexus, to define its theoretical origins, and to make its contribution to the development of the research field. Based on a hypothetical model of the contemporary relationship between UR and SD, we set the following two objectives: whether and how research incorporates newly perceived conceptual hazards (pandemic, war) and whether all groups of factors are explored equally and simultaneously.

We argue that it is important to draw attention to the possible lack of research and to highlight the categories of SD that are under-researched or not researched at all in this context. The study is therefore important for further research and understanding of the perspective in the context of pandemic and war as current anthropogenic hazards and opens research areas that need to be explored in the future for a clear understanding of this problem. The study model is a useful tool to observe the level of development of resilience of a particular urban community and to identify the level of development of important factors of the built environment. Thus, the study can serve as an important tool for future planning of resilient and sustainably developed urban areas. In order to identify the dynamics of UR and SD research involving pandemics and war, we conducted a numerical review of articles published on this topic up to 2022.

3. Methods

The literature review was conducted according to the PRISMA protocol [27,28]. First, we searched the EBSCOhost database for scholarly articles in Academic Search Complete, Business Source Premier, APA PsycInfo, Scopus, Web of Science (WOS), SocINDEX with Full Text, and GreenFILE. Then, we searched the JSTOR database, and finally other bases, such as Google Scholar. The searches were conducted in May and June 2022. This search set proved to be stable, as the results obtained with the narrower search datasets were also identified with the final search set, and the hits we relied on for the literature review were also identified with the broader search datasets.

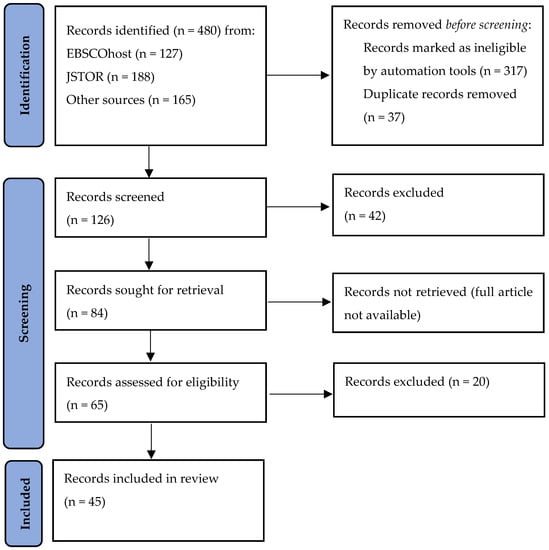

The screening process at EBSCOhost began by evaluating individual articles by title and abstract using the search term “urban resilience AND sustainable development*”. Our initial search query in EBSCOhost yielded no results. We therefore used a related search term, “urban resilience” AND “sustainable development” and obtained 127 results. We then evaluated each article using exclusion and inclusion criteria. Figure 2 shows the PRISMA flow diagram corresponding to the search protocol, inclusion and exclusion criteria, screening, eligibility, and final selection process. Articles that met the following inclusion criteria were considered for further review: (1) original empirical study/review article/book chapter, (2) written in English, (3) peer-reviewed, (4) at least abstract accessible, and (5) published between 2019 and 2022. Publications were excluded if they were (1) commentaries or editorial articles, (2) dissertations, or (3) unpublished articles. The same criteria were used to search for scientific publications in the JSTOR digital library, and the search term “urban resilience AND sustainable development*” yielded only one article. Using the search term “urban resilience” AND “sustainable development”, we obtained 188 hits. An identical search in other databases, especially Google Scholar, gave us 165 results. For further analysis, we considered publications that met the same cut-off criteria as those used at EBSCOhost.

Figure 2.

PRISMA diagram of the protocol for searching, inclusion, and exclusion of reviewed articles.

Based on these criteria and a review of duplicate publications, we extracted 66 articles from the EBSCOhost database that could be methodologically classified into review articles and original scientific articles reporting research conducted using quantitative and qualitative methods, and theoretical articles. In order to analyze them as systematically and thoroughly as possible, we looked for the restriction options offered by the EBSCOhost application. We then used the EBSCOhost restriction options to choose among the restrictions associated with “subject”, namely “subject-thesaurus term”, “subject-major heading”, and “subject”. After an independent content review by both authors, we chose the “subject-thesaurus term” restriction option and included only articles on the following clusters: urban planning, SD, urban growth, cities and towns, sustainable urban development, emergency management, social capital, urban renewal, and quality of life. We excluded the other options because they were not relevant to our research problem. There were no choices such as migration, war, etc., that we wanted to cover topics related to war-related aggression. The result was 14 publications.

In the JSTOR digital database, the 17 retrieved publications were further extracted by automatic “subject” bounding boxes and contained only publications on the following topics or clusters: environmental science, environmental studies, health science, intergovernmental relations, peace and conflict studies, population studies, public policy and administration, and urban studies, resulting in a total of 7 publications. We extracted 43 publications using other sources, reviewed them, and included 24 publications in the final analysis according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

The entire process of the systematic literature search is shown in the PRISMA diagram in Figure 2. This shows that of the 480 articles identified, 45 articles were extracted step by step, which are discussed in more detail in Section 4.

In the next section, we present the results of the literature review in line with the research questions. The results are followed by a discussion that includes UR and the sustainability perspective of the built environment and incorporates new conceptual tensions (pandemic, war), as presented in Figure 1, and a synthesis of the main findings of the literature review.

4. Results

Table 1 lists the a priori study and practice focus areas of UR and SD, as well as the study areas (clusters) that we identified and named within each focus level based on the underlying themes or constructs.

Table 1.

Key elements of the scientific articles included in the literature review by EBSCOhost database.

Table 1 shows that most excluded articles relate UR and sustainability to public sector functioning and governance (E3, E6, E7, E8, and E11), followed by environmental quality with the environmental factors presented (E1, E2, and E12), with significantly less coverage of the other groups of factors. Interestingly, most excluded articles identify natural disasters as a source of resilience (E1, E2, E3, E9, E12, and E14), followed by political instability (E4, E6, E7, and E8), while aggression (war) and climate change (E4, E6, E7, and E8) are the most common sources of resilience. A significant number of articles do not address the causes that lead to a situation in which UR is relevant (E10, E11, and E13).

Table 1 shows that most articles mention natural disasters (E1, E2, E12, E14) and political instability (E3, E4, E6, E7, E8, E9) as the main hazard. Only one article mentions war aggression (E5) and no pandemic (COVID-19) as threats. We note that a substantial number of articles do not mention a specific hazard that has led to a situation in which UR is relevant (E10, E11, E1, E13). In most of the articles where natural disasters are mentioned as the main hazard, they involve water (water resources, floods). We attribute this mainly to the fact that the water problem has become relevant in recent years with increasing urbanization [43]. Ref. [43] notes that today, more than two-thirds of water-scarce cities can alleviate water scarcity by investing in infrastructure, but they must be willing to make significant environmental trade-offs. Ref. [44] showed that strategic management of water resources in these cities is therefore important for the future of the global economy. On the other hand, there are the political problems arising from the growth of cities [45]. Therefore, most studies refer to the problem of urban management, economic stability, risk management, government stability, people’s sense of security, and trust. The lack of the latter is identified as a threat, so most studies identify the accelerated development of risk management as a solution. It is therefore not surprising that most studies identify MG as the main factor linking UR and SD (E3, E6, E7, E9, E11), followed by SE (E8, E13, E14) and EQ (E1, E2, E12).

According to the objective of whether and how research incorporates newly perceived conceptual hazards (pandemic, war), the results presented in Table 1 primarily show the lack of existing research that recognizes the threat of a pandemic such as COVID-19. Regarding the objective of whether all groups of factors are equally and simultaneously studied, the results presented in Table 1 show the lack of research that considers the plurality of UR in the broader context of SD.

We created results in Table 2 following the EBSCOhost restrictions and independently chose 10 clusters in which we included the read articles: environmental science, environmental studies, health science, intergovernmental relations, peace and conflict studies, population studies, public policy and administration, and urban studies. Of all the articles retrieved, only six were found to be relevant, fitting into four clusters: environmental science (J1–J3), peace and conflict studies (J4), health science (J5), and urban studies (J6).

Table 2.

Key elements of the scientific articles included in the literature review by JSTOR database.

Table 2 shows that most articles identify natural disasters (J2, J3, J6) as the main hazard. We note that a significant number of articles do not identify a specific hazard that leads to a situation where UR is relevant (J1, J4, J5). Most of the articles that mention natural disasters as a major hazard discuss climate change. Climate change is one of many types of shocks and stresses that cities face [10]. The cited articles in Table 2 associate UR with reducing the risks and consequential damages of natural disasters from climate change. Thus, they note that it is climate change that increases pressures and uncertainties for the economy, the environment, and society in general.

According to the objective of whether and how research incorporates newly perceived conceptual hazards (pandemic, war), the results presented in Table 2 primarily show the lack of existing research that recognizes the threat of the COVID-19 pandemic. Regarding the objective of whether all groups of factors are equally and simultaneously studied, the results presented in Table 2 show that in the broader context of SD, there is no research that considers the plurality of UR.

We created results in Table 3 according to Google Scholar and grouped them in one cluster. Of 43 articles retrieved, 24 were found to be relevant. Table 3 shows that most excluded articles UR and SD refer to management and governance factors (G1, G2, G3, G5, G8, G9, G10, G12, G14, G15, G17, G19, G20, G21, G23), followed by environmental quality factors (G1, G6, G11, G16, G18, G20, G21, G22), while the effects of other groups of factors are addressed much less. Interestingly, most excluded articles mention natural disasters as the main risk (G2, G3, G4, G6, G8, G15, G16, G19, G21), followed by political instability (G1, G4, G7, G9, G12, G14, G17, G24), while aggression (war) and pandemics (COVID-19) are not mentioned as sources of hazard in any of the excluded articles. A considerable number of articles do not discuss sources of danger at all (G5, G10, G11, G13, G18, G20, G22, G23). However, among all articles, there are seven articles that address the topic more comprehensively, covering at least three or four groups of factors simultaneously (G5, G10, G15, G17, G20, G21, G22). However, we did not find any article covering all five groups (EQ, UI, SE, MG, and D) simultaneously.

Table 3.

Key elements of the scientific articles included in the literature review by other databases.

The results show that most articles associate UR with urban governance, smart city development, and public services (n = 23), followed by infrastructure development (n = 18), socioeconomic development (n = 15), and environmental factors (n = 12), and the least with demographic impacts and migration (n = 3). Consequently, most of the excluded articles simultaneously address the importance of management and governance and urban infrastructure (n = 10). However, we found no article that simultaneously links management and governance to demographic impacts (n = 0), and no article that links demographic impacts to urban infrastructure (n = 0). The results show that climate change is one of many types of shocks and stresses that cities face, and that climate change-related shocks usually occur in combination with other environmental, economic, and political stresses. This was also confirmed by [10], who draws on numerous authors [71,72,73].

5. Discussion

Interestingly, the results show that researchers have focused primarily on the relationship between UR and the management and governance of urban built space over the past three years. It is believed that the influence of management and governance plays a key role in UR and consequently in the development of sustainability. On the other hand, our findings show that there is virtually no research linking demographic issues to UR and SD. The importance of the lack of a more comprehensive approach is also highlighted by other researchers who argue that UR as a perspective for SD the built environment requires a better understanding of the complex interactions, their impacts, and feedbacks in the context of multidimensional urbanization and the complex governance structures involved, land use change, climate change, changing ecological foundations, socioeconomic factors, emerging risks such as pandemics, multiple uses of urban space and resources, and new opportunities to engage in governance [74,75,76]. However, we found that researchers still associate UR mainly with resilience to phenomena resulting from political instability, also understood as a lack of risk management, poor governance and management of cities, poor communication between government structures, etc.

Only in second place are causes such as natural and environmental disasters, which surprised us. What surprised us even more was the virtual absence of studies dealing with pandemics (COVID-19) and war (migration) in the context of UR and US. Many of the studies we excluded from our review do not address the causes that UR requires. They understand UR as a general component of SD, to which they attach great importance, but they do not explain the causes, consequences, and interplay of complex interactions that can lead to different scenarios (e.g., [37,39,41,43,46,47,52,57,58,60,63,65,69]). As Ref. [77] notes, “We have memory, we look for patterns, we prepare scenarios.” The emergence of COVID-19, of aggression (war), and of many natural disasters, on the other hand, are memories from which we can search for patterns and prepare scenarios. We believe these scenarios should include all the factors that we combine in our study in the hypothetical model (Figure 1) as environmental quality (EQ), urban infrastructure (UI), socioeconomic impacts (SE), management and governance (MG), and demographic impacts (D).

All the hazards of recent years have dictated the need to integrate different skills. Most people are aware that the world is a single entity and that it is no longer enough to control local urban dynamics [78]. Collaborative scenario building, the development of new tools, disciplines, and solutions is becoming a process that involves all stakeholders in shaping the urban environment [78]. It points to a transition from a consumer society, where most people expect society to be responsible for their well-being, to a self-determined society, where everyone must take responsibility for what happens [78].

UR almost always has a positive connotation, emphasizing the adaptability of the local community (technical, organizational, social, and economic resilience), the flexibility of the socioeconomic paradigm (social, economic, physical, and human capital), and the physical resilience of the built environment (natural capital, physical features of the environment, stability of resources and infrastructure). In our research, we combined the above factors into a hypothetical model of the determinants of UR and SD observed in the context of threats to the health (COVID-19) and livelihood (global consequences of the war in Ukraine) of the population. Using the method of a systematic literature review over the past three years, the study had two objectives: whether and how research incorporates newly perceived conceptual hazards (pandemic, war) and whether all groups of factors are equally and simultaneously explored.

Our study confirmed the lack of existing research in the broader context of understanding the resilience of the built environment, and thus the lack of studies that provide a foundation and perspective for SD of the built environment. Therefore, we believe that further research should specifically focus on the plurality of approaches to understand the complex interactions, their impacts, and feedback in the context of multidimensional urbanization to understand UR as a perspective for SD.

The importance of taking a broader view of UR considering sustainable urban development must be emphasized in future research. The global UR design needs to respond in a way that understands all types of risk and addresses them in the context of resulting vulnerability. We can conclude that natural and anthropogenic hazards can impact all aspects of society, including its economy and the environment.

6. Limitations of the Study

Pandemics and wars are one of many types of shocks and stresses that cities can face and are the least explored in terms of sustainable urban development. The latter lends relevance to our study. However, we know that our study is limited and that future studies will have to cover all hazards simultaneously. The most studied hazards are certainly natural disasters due to climate change, such as extreme heat [79,80,81]. This was also confirmed by other studies [10,71,73].

7. Conclusions and Guidelines for Further Research

The study showed that newly perceived conceptual tensions (pandemic, war) related to UR have not been adequately explored. In line with the hypothetical model (Figure 1) that we set up in this study, we found:

- That most of the research on the relationship between UR and SD is on the management and governance of urban built space (MG).

- The second most important area of research is the urban infrastructure (UI) sub-area;

- Followed by research in the environmental quality (EQ) sub-area.

- The least amount of research is on demographic factors in UR (D).

The study confirmed the lack of existing research in the broader context of understanding built environment resilience, and thus the lack of studies that provide a foundation and perspective for SD the built environment. Therefore, we believe that further research should specifically focus on the multiplicity of approaches to understand the complex interactions, their impacts, and feedbacks in the context of multidimensional urbanization to understand UR as a perspective for SD of the built environment. In this way, we would encourage researchers to continue their research in this important area, which will ultimately lead to the overall satisfaction and well-being of users of the built environment. It is impossible to predict the response and behavior of citizens in the event of a disaster. However, something can certainly be done to make the built environment more resilient, which may help the disaster itself respond positively to the disruption. Such a response can reduce material damage, migration, and all the negative impacts of a disaster. Therefore, we believe that this study, which highlights the lack of mainly pluralistic research, can encourage researchers to further investigate this topic.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.G. and D.K.G.; methodology, B.G. and D.K.G.; software, D.K.G.; validation, B.G. and D.K.G.; formal analysis, B.G. and D.K.G.; investigation, B.G. and D.K.G.; resources, B.G. and D.K.G.; data curation, B.G. and D.K.G.; writing—original draft preparation, B.G. and D.K.G.; writing—review and editing, D.K.G.; visualization, B.G.; supervision, B.G.; project administration, B.G.; funding acquisition, B.G. and D.K.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research was supported by the Slovenian research agency (grant numbers J5-3112, J7-4599, and P5-0110).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Meerow, S.; Newell, J.P.; Stults, M. Defining urban resilience: A review. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2016, 147, 38–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, P.J.G.; Pena Jardim Gonçalves, L.A. Urban resilience: A conceptual framework. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2019, 50, 101625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, B. A review of the literature on community resilience and disaster recovery. Curr. Environ. Health Rep. 2019, 3, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patel, S.S.; Rogers, M.B.; Amlôt, R.; Rubin, G.J. What do we mean by ‘community resilience’? A systematic literature review of how it is defined in the literature. PLoS Curr. 2017, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gill, J.C.; Malamud, B.D. Anthropogenic processes, natural hazards, and interactions in a multi-hazard framework. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 166, 246–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghim, S.; Garna, R.K. Countries’ classification by environmental resilience. J. Environ. Manag. 2019, 230, 345–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, S.; de Souza Filho, C.R. Spectral remote sensing for onshore seepage characterization: A critical overview. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2017, 168, 48–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, J.C. Vulnerability, capacity and resilience: Perspectives for climate and development policy. J. Int. Dev. J. Dev. Stud. Assoc. 2010, 22, 218–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jon, I. Resilience and ‘technicity’: Challenges and opportunities for new knowledge practices in disaster planning. Resilience 2019, 7, 107–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.M. Climate change and urban resilience. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2011, 3, 164–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marto, R.; Papageorgiou, C.; Klyuev, V. Building resilience to natural disasters: An application to small developing states. J. Dev. Econ. 2018, 135, 574–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Lin, K.; Tang, G.; Zhang, Q.; Hong, Y.; Chen, X. A framework to evaluate community resilience to urban floods: A case study in three communities. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, C.; Liao, L.; Li, H.; Su, Z. Which urban communities are susceptible to COVID-19? An empirical study through the lens of community resilience. BMC Public Health 2022, 22, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laakkonen, S. Urban resilience and warfare: How did the Second World War affect the urban environment? City Environ. Interact. 2020, 5, 100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanović, A.; Klimek, P.; Renn, O.; Schneider, R.; Øien, K.; Brown, J.; Chhantyal, P. Assessing resilience of healthcare infrastructure exposed to COVID-19: Emerging risks, resilience indicators, interdependencies and international standards. Environ. Syst. Decis. 2020, 40, 252–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wister, A.; Speechley, M. COVID-19: Pandemic Risk, Resilience and Possibilities for Aging Research. Can. J. Aging La Rev. Can. Du Vieil. 2020, 39, 344–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharifi, A.; Khavarian-Garmsir, A.R. The COVID-19 pandemic: Impacts on cities and major lessons for urban planning, design, and management. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 749, 142391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, A.; Kötter, T.; Fekete, A.; Moghadas, M.; Alizadeh, M.; Zebardast, E.; Weiss, D.; Basirat, M.; Hutter, G. Urbanization, migration, and the challenges of resilience thinking in urban planning: Insights from two contrasting planning systems in Germany and Iran. Cities 2022, 125, 103642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barani, A.; Kahraman, Z.E. Uncovering Vulnerabilities and Resilience of Benghazi after the War. Resil. J. 2019, 3, 165–171. [Google Scholar]

- Coale, A.J. Demographic Transition. In Social Economics; Eatwell, J., Milgate, M., Newman, P., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 1989; pp. 16–23. [Google Scholar]

- Webb, J.W. The natural and migrational components of population changes in England and Wales, 1921–1931. Econ. Geogr. 1963, 39, 130–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilav, A. Before the war, war, after the war: Urban imageries for urban resilience. Int. J. Disaster Risk Sci. 2012, 3, 23–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, S.O.; Ferrara, A. Consequences of forced migration: A survey of recent findings. Labour Econ. 2019, 59, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugo, G.J. Internal and International Migration in East and Southeast Asia: Exploring the Linkages. Popul. Space Place 2016, 22, 651–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostadtaghizadeh, A.; Ardalan, A.; Paton, D.; Jabbari, H.; Khankeh, H.R. Community disaster resilience: A systematic review on assessment models and tools. PLoS Curr. 2015, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Büyüközkan, G.; Ilıcak, Ö.; Feyzioğlu, O. A review of urban resilience literature. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 77, 103579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirzadeh, M.; Sobhaninia, S.; Sharifi, A. Urban resilience: A vague or an evolutionary concept? Sustain. Cities Soc. 2022, 81, 103853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009, 62, 1006–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beceiro, P.; Brito, R.S.; Galvão, A. Assessment of the contribution of Nature-Based Solutions (NBS) to urban resilience: Application to the case study of Porto. Ecol. Eng. 2022, 175, 106489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Hopton, M.E.; Wang, X. Assessment of green infrastructure performance through an urban resilience lens. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 289, 125146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acuti, D.; Bellucci, M.; Manetti, G. Company disclosures concerning the resilience of cities from the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) perspective. Cities 2020, 99, 102608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez-Medina, P.; Artal-Tur, A.; Sánchez-Casado, N. Tourism business, place identity, sustainable development, and urban resilience: A focus on the sociocultural dimension. Int. Reg. Sci. Rev. 2021, 44, 170–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aquilino, M.; Tarantino, C.; Adamo, M.; Barbanente, A.; Blonda, P. Earth observation for the implementation of sustainable development goal 11 indicators at local scale: Monitoring of the migrant population distribution. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Kou, C.; Wen, F. The dynamic development process of urban resilience: From the perspective of interaction and feedback. Cities 2021, 114, 103206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S. Reactive, Individualistic and disciplinary: The urban resilience project in dhaka reactive, individualistic and disciplinary: The urban resilience project in Dhaka. New Political Econ. 2021, 26, 1078–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, S.; Xu, H.; Chen, F. A hierarchical measurement model of perceived resilience of urban tourism destination. Soc. Ind. Res. 2019, 145, 777–804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz-Sarachaga, J.M.; Jato-Espino, D. Do sustainable community rating systems address resilience? Cities 2019, 93, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, A.; Monstadt, J.; Driessen, P.P.J. Building urban and infrastructure resilience through connectivity: An institutional perspective on disaster risk management in Christchurch, New Zealand. Cities 2019, 98, 102573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huck, A.; Monstadt, J.; Driessen, P.P.J.; Rudolph-Cleff, A. Towards resilient Rotterdam? Key conditions for a networked approach to managing urban infrastructure risks. J. Contingen. Crisis Man. 2021, 29, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anguelovski, I.; Irazábal-Zurita, C.; Connolly, J.J. Grabbed urban landscapes: Socio-spatial tensions in green infrastructure planning in Medellín. Int. J. Urban Reg. Res. 2019, 43, 133–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Q.; Zhu, M.; Qiao, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J. Achieving resilience through smart cities? Evidence from China. Habitat Int. 2021, 111, 102348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumura, C.K.; Locke, M.; Fraga, J.P.R.; de Oliveira, A.K.B.; Veról, A.P.; de Magalhães, P.C.; Miguez, M.G. Integrated water resource management as a development driver–prospecting a sanitation improvement cycle for the greater Rio de Janeiro using the city blueprint approach. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 315, 128054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, T.; Sikder, M.J.U.; Bhuiyan, M.R.A. Climate change and mitigation in Bangladesh. Cool. Down Local Responses Glob. Clim. Chang. 2022, 1, 113–130. [Google Scholar]

- Wade, K.; Vrbka, J.; Zhuravleva, N.A.; Machova, V. Sustainable governance networks and urban Internet of Things systems in big data-driven smart cities. Geopolit. Hist. Int. Relat. 2021, 13, 64–74. [Google Scholar]

- Thoren, H. Resilience in ecology and sustainability science. In Situating Sustainability: A Handbook of Contexts and Concepts; Krieg, C.P., Toivonen, R., Eds.; Helsinki University Press: London, UK, 2021; pp. 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cilk, M. National culture and urban resilience. Consilience 2020, 22, 18–30. [Google Scholar]

- Manteaw, B.O. Mindscapes and Landscapes. Consilience 2020, 22, 93–103. [Google Scholar]

- Roggema, R. The ‘Beltscape’: New horizons for the city in its natural region. In Repurposing Green Belt 21st Century; Bishop, P., Martinez Perez, A., Roggema, R., Williams, L., Eds.; UCL Press: London, UK, 2020; pp. 119–155. [Google Scholar]

- Carta, S.; Pintacuda, L.; Owen, I.; Turchi, T. Resilient communities: A novel workflow. Front. Built Environ. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caughman, L.E. Collaboration and Evaluation in Urban Sustainability and Resilience Transformations: The Keys to a Just Transition? Ph.D. Thesis, Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, B.; Sharifi, A.; Schlör, H. Integrated social-ecological-infrastructural management for urban resilience. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2022, 181, 106268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavin, C.T.; Dabreau, A.M.; Walpole, E.H. Resilience, Adaptation, and Sustainability Plan Assessment Methodology: An Annotated Bibliography. Tech. Note 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cobbinah, P.B. Urban resilience in climate change hotspot. Land Use Policy 2021, 100, 104948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elmqvist, T.; Andersson, E.; Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Olsson, P.; Gaffney, O.; Folke, C. Sustainability and resilience for transformation in the urban century. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 267–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fastiggi, M.; Meerow, S.; Miller, T.R. Governing urban resilience: Organisational structures and coordination strategies in 20 North American city governments. Urban Stud. 2021, 58, 1262–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frantzeskaki, N.; McPhearson, T.; Kabisch, N. Urban sustainability science: Prospects for innovations through a system’s perspective, relational and transformations’ approaches. Ambio 2021, 50, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaman Galantini, Z. Catching on “Urban Resilience” and Examining “ Urban Resilience Planning” “Kentsel Dayanıklılığı” Anlamak ve “Kentsel Dayanıklılık Planlanmasını”. İrdelemek İdealkent 2019, 10, 882–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, T.; Wang, B.; Li, L.; Gou, X. The coupling relationship between urban resilience level and urbanization level in Hefei. Math. Probl. Eng. 2022, 2022, 7339005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapucu, N.; Martín, Y.; Williamson, Z. Urban resilience for building a sustainable and safe environment. Urban Gov. 2021, 1, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.; Wu, Q.; Yan, S.; Peng, J. Factors Affecting Urban Resilience and Sustainability: Case of Slum Dwellers in Islamabad, Pakistan. J. Urban Plan. Dev. 2021, 147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramirez Lopez, L.J.; Grijalba Castro, A.I. Sustainability and resilience in smart city planning: A review. Sustainability 2020, 13, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narieswari, L.; Sitorus, S.R.P.; Hardjomidjojo, H.; Putri, E.I.K. Multi-dimensions urban resilience index for sustainable city. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 399, 012020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creamer, E.G.; Guetterman, T.C.; Govia, I.; Fetters, M.D. Challenging procedures used in systematic reviews by promoting a case-based approach to the analysis of qualitative methods in nursing trials. Nurs. Inq. 2021, 28, e12393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni’mah, N.; Roychansyah, M. Urban Sustainability and Resilience Governance: Review from The Perspective of Climate Change Adaptation And Disaster Risk Reduction. J. Reg. City Plan. 2021, 32, 83–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eskandari Nodeh, M.; Gholipoor, Y.; Fallah Heydari, F.; Ahmadpour, A. Identifying Resilience Dimensions and its Impact on Urban Sustainability of Rasht City. Geogr. Environ. Sustain. 2019, 9, 63–77. [Google Scholar]

- Philibert Petit, E. Smart City Technologies plus Nature-Based Solutions: Viable and valuable resources for urban resilience. In Smart Cities Policies and Financing; Vacca, J.R., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 377–398. [Google Scholar]

- Sethi, M.; Sharma, R.; Mohapatra, S.; Mittal, S. How to tackle complexity in urban climate resilience? Negotiating climate science, adaptation and multi-level governance in India. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0253904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Yu, Y.; Yang, S.; Lv, Y.; Sarker, M.N.I. Urban resilience for urban sustainability: Concepts, dimensions, and perspectives. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tootoonchi, S.; Bahrainy, H.; Tabibian, M. Introducing a new paradigm in urban planning through integration of resilience and critical theory to increase feasibility of urban resilience. Laplage Em Rev. 2021, 7, 521–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urquiza, A.; Amigo, C.; Billi, M.; Calvo, R.; Gallardo, L.; Neira, C.I.; Rojas, M. An integrated framework to streamline resilience in the context of urban climate risk assessment. Earth’s Future 2021, 9, e2020EF001508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coaffee, J. Risk, resilience, and environmentally sustainable cities. Energy Policy 2008, 36, 4633–4638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Sherbinin, A.; Schiller, A.; Pulsipher, A. The vulnerability of global cities to climate hazards. Environ. Urban. 2007, 19, 39–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leichenko, R.; O’Brien, K. Environmental Change and Globalization: Double Exposures; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wilbanks, T.J.; Kates, R.W. Beyond adapting to climate change: Embedding adaptation in responses to multiple threats and stresses. Ann. Assoc. Am. Geogr. 2010, 100, 719–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, E. “Reconnecting cities to the biosphere: Stewardship of green infrastructure and urban ecosystem services”-where did it come from and what happened next? Ambio 2021, 50, 1636–1638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folke, C.; Polasky, S.; Rockström, J.; Galaz, V.; Westley, F.; Lamont, M.; Walker, B.H. Our future in the Anthropocene biosphere. Ambio 2021, 50, 834–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nathanial, P.; Van der Heyden, L. Crisis management: Framework and principles with applications to COVID-19. Working paper. INSTEAD. Bus. Sch. World 2020, 17, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Nevejan, C. City science for urban challenges, Pilot assessment and future potential of the City Science Initiative 2019–2020. Eur. Comm. 2020. Available online: https://openresearch.amsterdam/nl/page/63027/city-science-for-urban-challenges (accessed on 20 September 2022).

- He, B.J.; Zhao, D.; Xiong, K.; Qi, J.; Ulpiani, G.; Pignatta, G.; Jones, P. A framework for addressing urban heat challenges and associated adaptive behavior by the public and the issue of willingness to pay for heat resilient infrastructure in Chongqing, China. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2021, 75, 103361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, B.J.; Wang, J.; Zhu, J.; Qi, J. Beating the urban heat: Situation, background, impacts and the way forward in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 161, 112350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalho, D.; Martins, H.; Marta-Almeida, M.; Rocha, A.; Borrego, C.J.U.C. Urban resilience to future urban heat waves under a climate change scenario: A case study for Porto urban area (Portugal). Urban Clim. 2017, 19, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).