Abstract

This research is about the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), which is an important and first project of the “Belt and Road” initiative (BRI). BRI is the framework and manifesto for the wide-ranging, fundamental collaboration signed by China and Pakistan in 2013. The CPEC vision and mission were initiated to develop economic growth and facilitate free trade, the people’s living standards of Pakistan and China through bilateral investments, trade, cultural exchanges, and economic activities between both countries. The initial investment for the project was $46 billion, with a tentative duration of fifteen years. This research aimed to inquire into the effects of legal risks (LR), social security (SS), and employee environmental awareness (EEA) on the project performance (PP) of the CPEC. It further investigates the significance of gender empowerment perspectives (GEP). A research framework consisting of this quantitative analysis and the bilateral impacts of the study were explored through several policies scenarios into 2025. The results of the risk analysis were rated on a Likert scale. A questionnaire survey was used in order to collect data and test the research framework and hypotheses. An empirical test was conducted using a dataset with partial least square structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) to validate the study.

1. Introduction

China and Pakistan have enjoyed close, and cordial ties as great friends, partners, and brothers since the two nations’ diplomatic relations were established in May 1951 [1]. The connection has developed into an “all-weather strategic cooperative partnership” over time, more comprehensively after ratifying the Bilateral Investment Treaty of 1989 (BIT) [2]. Most recently, the recent development in this relationship discourse through the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC or Corridor) under the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is going to be a game changer in the region [3]. This corridor will serve for greater development and the social and economic progress of both China and Pakistan. As the corridor is a component of China’s considerably more comprehensive trade and infrastructure development strategy, it will benefit over four billion people in over 60 countries, with regional economies growing by a minimum of $2.5 trillion [4].

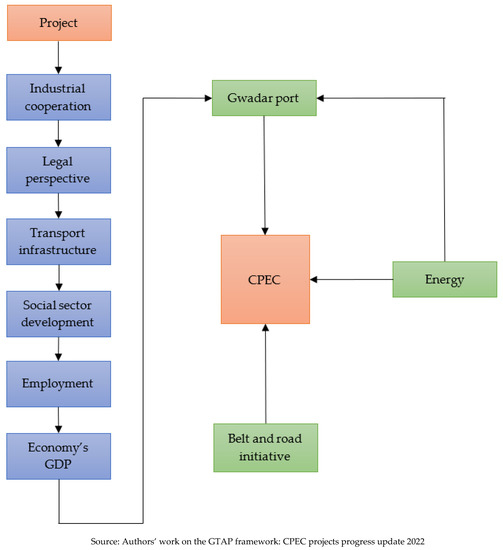

The BRI aspires to connect China with Central Asia, Europe, and Russia via the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean. Therefore, Pakistan’s strategic location in Southeast Asia, bordering Iran and Afghanistan in the west [5], China in the northeast, and India to the east, has contributed to its significance in the region as a transit fare. The Arabian Sea bordering Pakistan’s south, with a 1046-km shoreline, serves as a major commercial route between Pakistan and the rest of the globe. The ports located there will be a principal focus of China [6]. Because of significant investment in other sectors, Pakistan will also be one of the project’s main beneficiaries in addition to the areas mentioned above [7]. The agriculture, industry, and services sectors account for the largest shares of the Pakistani economy’s GDP, contributing 21.4%, 20.8%, and 53.3%, respectively [8]. Due to the country’s acute energy situation, interest from investors has fallen in all these areas. In the midst of these difficulties, the CPEC presents Pakistan with a chance to attract new investors and spark economic activity that could lead to socioeconomic progress [9,10]. Figure 1 demonstrates the CPEC projects that have been progressing under the CPEC authority of Pakistan recently [11] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Projects Progress Update.

Given the above and Pakistan’s crucial but strategic location from an economic and apolitical standpoint for Asia and the rest of the world, the utilization of women in such a development landscape is attaining great significance [12]. As a land with a lot of potentials to affect the political and socioeconomic landscape as the sole Muslim nuclear power [13], Pakistan’s proximity to the Persian Gulf, where around 65 percent of the world’s oil is produced, women play a crucial role in its growth. While women’s employment plays a crucial part in human capital and is a strategically significant component of development [14,15], it is also necessary to reap the rewards of social-economic development and forward-thinking economies. In contrast to industrialized countries, this idea is far more dispersed in developing nations. Therefore, this research focuses on the legal risks and social security of the women in Pakistan who will potentially work in the CPEC mechanism under the BRI strategy [16].

In its 2012 version of the constitution, the Communist Party of China (CCP) under President Xi Jinping set two key centennial goals for China’s progress [17]. The first objective takes place in 2021, the year that CCP turns 100. President Xi Jinping wants China’s GDP and per capita income to have doubled by this time compared to 2010. The second goal is to turn China from a “moderately successful society” By the time the People’s Republic of China turns 100, we aim to transform it into a modern socialist nation that is powerful, democratic, culturally developed, and peaceful [18,19]. These extremely lofty objectives are the foundation of President Xi Jinping’s doctrine, which will be elucidated later. These two centennial objectives seek to advance China’s development and economy to unprecedented heights [20]. The accomplishment of these objectives is crucial to the legitimacy of the CCP’s authority. From this perspective, BRI and CPEC are two major initiatives that will propel China’s economic development [21].

This research is an empirical investigation focused on discovering a negative relationship between Legal Risks (LR) [22], Social Security (SS) [23], and Employee Environmental Awareness (EEA) [24]. It will be concluded that LR, SS, and EEA negatively influence the CPEC because of the lack of a policy framework developed under the BIT [25]. Furthermore, this research also analyzes that the Gender Empowerment Perspective (GEP) negativities moderate the ROL, L-R, and SS of CPEC [26]. In differentiation, the values of EEA and ROL were investigated in the presence of the positive GEP.

The remaining structure of the paper is as follows: Section 2 outlines the literature review. Section 3 presents the material and methods, while Section 4 focuses on the impact of women’s empowerment perspectives and the legal framework between Pakistan and China. Section 5 provides conclusions, limitations, and future research areas.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Infrastructure Project

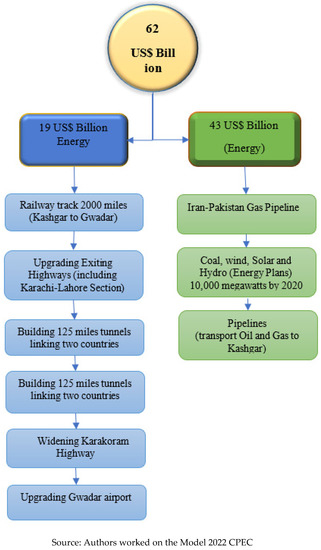

Over the next 10 to 15 years, initially, the Chinese government had intended to invest more than $46 billion through the CPEC in development projects, a variety of ongoing infrastructure projects are under construction and fall under the CPEC’s scope of investment, and were to be completed all over Pakistan, with a foundation amount of investment of US$46 billion in 2013 [27]. Then, it was revised to an initial estimation of US$55 billion [28]. The value of CPEC projects has increased again to $62 billion as of 2020 [29] after the inclusion of new projects, including industrial zones, the Karachi Circular Railway, and other projects, which is equal to 25% of Pakistan’s GDP [30]. The energy sector will receive about $43 billion in investments to expand its capacity by supplying 17,000 megawatts of electricity are provided to the infrastructure and national grid [31]. The remaining $19 billion will go to communications, transportation, and energy. For example, Figure 2 reflects that the railway lines between Peshawar and Karachi will be addressed with some of these funds.

Figure 2.

Outlying in CPEC.

The CPEC’s growth of transportation infrastructure projects has affected local citizens’ education. Additionally, officials frequently assess community needs, acceptance, and lifestyle using the outcomes of regional community behavior [32]. The local communities will benefit from the project development. It is a proven fact that when residents profit from the growth of CPEC projects and see it favorably, they have faith in the CPEC policies and offer more support. So, the current study considers many of the regional community’s benefit-based approaches and the host community’s feelings about the CPEC projects that will be built [23].

The three primary phases of all CPEC projects are meant to be completed sequentially. The completion dates for CPEC projects in the short, medium, and long term are 2020, 2025, and 2030, respectively [32]. The money was originally intended to be distributed among the projects as depicted.

The CPEC will fund the construction of economic zones alongside its trade routes, including Khuzdar to Bisma, Gwadar-Hosab, the Karachi to Lahore, and Karakorum motorways, as well as railway lines to link them [33]. This connectivity is intended to guarantee goods access for trades and consumers to enhance domestic business and investment. Railway tracks will also be extended from Karachi-Peshawar to improve connections and expand transportation options. For long-term and medium-term investments, Pakistan has designated nine favorable trade zones [34]. In order to increase Pakistan’s exports to international markets, stronger development investments are being made, and a mix of energy technologies is focusing on manufacturing development [35]. This will encourage the expansion of logistics, transportation, and enriched exports from Pakistan. The industrial and infrastructure growth of development areas of the CPEC are developing into an efficient tool for decreasing Pakistan’s national debt and improving profitability for repaying CPEC debts [36]. The CPEC infrastructure expansion and concurrent key interconnections have created a more competitive environment for the central Asian states to interchange and vend their commodities in international markets. Pakistan wants to travel through Afghanistan to Central Asia known as Middle Asia [37,38,39].

2.2. Gwadar Port and Gwadar Sea Port

It is anticipated that the CPEC will further improve trade and economic relations between the two nations. Chinese Premier Li Keqiang highlighted the CPEC edifice during his visit to Pakistan in May 2013 [40]. Since then, the current Pakistani administration has also demonstrated a lot of excitement for the project. The corridor will link Kashgar in northwest China to Baluchistan (Pakistan), making Gwadar Port in Baluchistan fully operational and an important deep-sea port in the area [41]. The government-owned China Overseas Ports Holding received control of Gwadar Port. Since that time, Gwadar has undergone significant growth to become a complete, deep-water commercial port. With Pakistan serving as south Asia’s gatekeeper for South, Central, and East Asia, Gwadar is a natural gateway to China, Pakistan, and Afghanistan along the trade routes of Central Asia [42]. China would thus lessen its reliance on the Malacca Strait checks. The Gwadar of port has become more crucial to its strategic approach due to changes in global energy policies, the risky South-China marine environment, and the Sri-Lanka and Malacca Straits making up China’s newest sea route [43].

The goal of the CPEC projects is to promote the growth of economic and free commerce among the two nations. However, that has also led to a significant increase in employment opportunities, worker environmental awareness, social security, educational opportunities, legal risks, assessments of the rule of law, and an improvement in the standard of life for residents, particularly women [41]. This research study explores and analyzes the advantages of the CPEC plan and how it affects attitudes toward women’s empowerment by considering what we understand about the CPEC.

Due to Kashgar’s distance from its most important port in China, which is 4500 km, the Gwadar port would help reduce travel distances by around 2800 km and 2500 km, respectively. Raising China’s many million-dollar exports would reduce the deficit [44]. These highways would facilitate the development of many facilities, including communications and economic zones. On the other hand, most emerging nations in south Asia, the Middle East, and central Africa have reacted to China and Pakistan’s ideas of economic growth [45]. There may have been a gathering of more than 3 billion individuals. More goods and services will be exported because of improved road connections and the development of the Gwadar port. Considering that there are more than two hundred million people in Pakistan, there is a majority of young people, and human resources could potentially be a significant exploitative source. Pakistan’s Karachi region will develop into a significant port and profit from its ties to the Gwadar port [46], which might benefit the residents of Karachi, in particular, with significant investments and economic trends. Thus, the development of Gwadar has benefited the shipping, industrial, and fishing sectors. These factors combined make it an economic center for Karachi’s passionately driven business community and private sector [47].

2.3. Energy Projects

Following a fast-track agenda, China intends to invest 43 billion dollars in 21 energy projects in Pakistan through CPEC from 2018 to 2020. These energy projects have received 5–6% financing from the Exim Bank of China [48]. Some studies have shown that Pakistan’s economic growth and energy use are related. Additionally, one study concludes that energy benefits employment prospects. Energy production and national economic expansion are related. Energy plays a significant role in CPEC, to the point where it could also be referred to as the China–Pakistan Energy Corridor, and much of the total funds are estimated to be invested in power-producing facilities [49] (See Table 1).

Table 1.

Energy Projects Under CPEC.

2.4. Maritime Belt and Ports

President Xi Jinping of China first proposed developing a 21st-century version of the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and the Maritime Silk Road (MSR) in 2013 [51]. This announcement marked the beginning of the BRI Initiative [52]. The BRI consists of hundreds of large-scale international projects, including industrial parks, power, trains, and bridges, with far-reaching effects on the participating nations. Parallel to this, BRI has presented potential barriers between these international endeavors and local people, such as climate change and displacement, which have brought significant benefits. China’s diplomatic efforts are based on the BRI and CPEC [53,54]. Pakistan is to be considered vital to the execution of this diplomacy as envisaged by Chinese diplomatic circles. This would not simply be limited to economic benefits. In many ways, Pakistan, which is crucial to China’s geostrategic objectives through the CPEC, will gain in practical terms if its human capital is properly utilized. Since the CPEC decided to use this resource strategically, its importance has become increasingly apparent. There is widespread agreement that human resources must demonstrate that a country’s development depends on its human capital [55].

The consequences of CPEC on the Pakistani community have barely been studied. This research includes an inclusive review of the prior literature in two disciplines. This research study’s initial emphasis was on the body of existing literature [56]. Employee environmental awareness sought to locate studies on the effects of gender disparities in empowerment. Researchers and decision-makers have been examining how women have impacted the development of less developed nations. Scientists and experts are inspired by the astounding eastern Bose study from the 1970s; the study explored solutions to the issue of gender disparities that impede developmental progress.

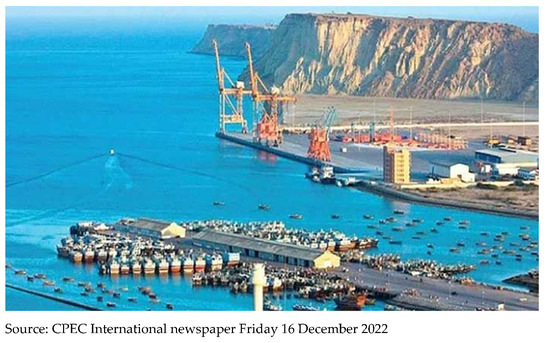

One of the factors contributing to the economic success of members like Pakistan and China is the CPEC (see Figure 3). The former benefited from the development of an internal infrastructure that raised the standard of living in the area [57]. These measures also help Pakistani women living in both urban and rural areas. The advantages of the CPEC are felt throughout Pakistan, not only in one area especially as a means of empowering women economically. In Pakistan, rural residents, especially women, confront several difficulties, including inadequate employment, education, and healthcare opportunities [58]. Numerous studies of the CPEC have been conducted based on the literature, including research focusing on the supply of benefits to local people by the beginning of the CPEC. However, no research has been done on the CPEC project with a focus on empowering women in the Thar region, one of the poorest regions in the country [59]. Thus, by focusing on the empowerment of women and learning how the CPEC directly impacts the empowerment of women by offering work possibilities, a high standard of living, and educational facilities to the women in Sindh of the Thar region, this study fills the research vacuum and adds to the body of knowledge. This study supports the idea that local women directly benefit from CPEC’s opportunities for employment, education, and a high standard of living. These markers are significant for women in such underdeveloped places, and this study hopes to use them to determine how women feel about CPEC [60]. It will help policymakers create better policies to support local communities and women [61].

Figure 3.

CPEC Location.

2.5. Characteristics of the Population

Regarding the ideal organizational settings that emphasize enhancing environmental performance for their personnel [62]. Table 2 displays the overall characteristics of the participants in this study who responded. According to the characteristics, there were 248 females and 319 males (56.26% and 43.73%, respectively). A total of 68 respondents were under 20–25 years old (14.46%), 99 were aged between 30–35 (21.06%), 159 were aged between 40–45 (33.82%), 106 were aged between 50–55 (22.5%), and 38 were over 55 years old (8.08%).

Table 2.

Analytical of gender traits.

2.6. Industry Types of Respondents

The information gathered on segment properties for the final sample, broken down by segment. Table 3 express 78 employment respondents in green organizations in the agriculture industry (15.82%), 76 in the energy sector (15.41%), 71 in the construction sector (14.40 %), 74 in the waste management service sector (15.01%), 95 in the transport sector (19.26%), and 90 in the rural sector and forestry (18.25%) (See Table 3).

Table 3.

Industry type and respondents in their 30s, 40s, and 50s.

3. Material and Methods

This paper comprises the author’s analysis, an evaluation of the literature review and jurisprudence, and personal reflections on the CPEC project’s legal regulations. The research was based on articles from peer-reviewed English journals in databases and official websites of the participating countries: PubMed, the Web of Science, served as the source for the study’s data, published between 2013 and 2022, through the use of certain keywords. The rule of law has to do with legal risks, social security, environmental awareness among employees, the CPEC, and women’s empowerment.

The CPEC aspires to improve people’s quality of life in China and Pakistan through bilateral investments, trade, cultural exchanges, and economic activities. Pakistan and China set up the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor Authority (CPECA) to help reach this goal [62]. Our research methods focused on how the CPEC in Pakistan has empowered women and examined how rules can be made to get more women to work on the CPEC Project [63].

Items from a prior study were used. All variables were computed to identify which variables had the highest and lowest mean values to understand better research variables like mean, and standard deviation, and the correlation provides all the variables’ descriptive statistics and correlation matrix (refer Table 4). There is a high association between CPEC expansion and employment opportunities (r = 0.516, p < 0.05), education improvement and the CPEC (r = 0.618, p < 0.05), and quality of life and the CPEC (r = 0.589, p < 0.05). All correlation values are less than 0.80 and significant at the two-tailed level, while the standard deviation ranges from 0.48 to 0.58, suggesting that mean values are above average. The table shows how the CPEC’s integration significantly increased foreign direct investment, benefiting the country. However, there has been a global decline in investment activities and remittances as a current result of the COVID-19 epidemic and the lockdown scenario. The tables display data from direct investment in China and Pakistan.

Table 4.

Correlation.

This research is an empirical investigation focused on discovering a negative relationship between the analysis of gender traits, industry type and respondents, legal risks (LR), social security (SS), and employee environmental awareness (EEA). It will be concluded that LR, SS, and EEA negatively influence the CPEC because of the lack of a policy framework developed under the BIT. Furthermore, this research also suggested that the Gender Empowerment Perspective (GEP) negatively moderates the ROL, LR, and SS of the CPEC. In contrast, the value of EEA and ROL can be investigated in the presence of the positive GEP. The research is divided into six parts, including an introduction and conclusion, wherefore, following from here, the literature review depicts the gaps and laxity in the research conducted so far, followed by analysis and discussion sections.

It also discusses how employees can be more aware of the environment. Consequently, in order to give this concept some context, to analyze the data and answer these study problems, qualitative and quantitative methods were used, and this research addresses three major issues related to the research questions. Specifically, a single circumstance study was used to answer the CPEC authority of initiative, government, and practice questions: (1) How does this promote women’s and girls’ equal rights in the effects of passing through the CPEC route on local women; (2) What is the difference between gender equity, gender equality, gender employment, and women’s empowerment in the CPEC project? (3) What helps women break out of the cycle of poverty and build their futures? A situation study is the most popular approach used to conduct a thorough investigation of current occurrences that the investigator has little or no influence over. The questionnaire was used to collect data in a systematic way to answer the CPEC authority impact question, which compared how the local community changed before and after CPEC transnational projects were built, and how the CPEC authority works.

4. The Impact of Women’s Empowerment

4.1. Effects Empowerment of Women’s Education

The right of women to education has been acknowledged. Women’s education has a positive impact on national production, income, and economic development, as well as a population that is healthier and more adequately fed [64]. All types of demographic activity, including mortality, health, fertility, and contraception, depend on it. According to geography, culture, and the level of development, women’s gains from education vary greatly. Still, it is undeniable that education empowers women, giving them more autonomy and leading to fewer children in almost every situation [65]. This study concludes that the generalizations concerning the interactions between education, fertility, and female autonomy are complicated by contextual factors, such as the general degree of socioeconomic development and the condition of women in traditional kinship networks. It explains how these findings affect policy and makes smart suggestions for more research.

4.2. Women’s Paid Job Involvement

It is assumed that women’s involvement in businesses, paid jobs, and other revenue-generating activities will lessen their dependency on the economy. Additionally, it boosts their influence over resources, participation in decision-making, and mobility [66]. Greater autonomy was seen among people working in successful industries. It has been asserted that women’s ability is primarily due to their dependence on the economy and that economically productive women can raise their position in all spheres of life. Therefore, by creating a supportive atmosphere, planners should devise strategies to improve women’s employment status. A global survey found that employment is the most important factor in women’s independence [67].

4.3. Women’s Awareness and Rights

Hundreds of millions of women and girls are not allowed to go to school and work, which stops them from becoming independent. Women should benefit from the CPEC by breaking the cycle of poverty and building a future for themselves [68]. The CPEC project and Pakistan’s women are more essential than anything else. Despite some concerning eliminations, the figures show increasing support for women’s rights. Nevertheless, passing a law is only one obstacle in the way of refining the lives of women. The gap between women’s realities and what is written in the laws is still very extensive [69,70].

4.4. Status of Women in Pakistan

The framework establishes women’s place in daily work and encourages a strict division of labor. It also places restrictions on women’s freedom of movement. The family is intimately tied to the status of the average woman, and she is essential to keeping the family together by having children, nurturing them, and caring for the elderly [71]. Particularly in India and Pakistan, there is a widening gender gap in education, employment, political engagement, decision-making, access to health care, employment prospects, and investment in women’s education. [72]. In the discriminatory system, the place of in the family and society is unsatisfactory. The CPEC presents numerous chances for growth and development for Pakistan and the provinces that the route travels through. However, current stereotypical limitations on an educated female workforce prevent them from contributing actively to such a successful endeavor [73]. The study underscores this disparity in terms of a crucial but frequently disregarded question as to how the CPEC can change the game for Pakistani women. It could either significantly advance the status of women in Pakistan or exacerbate their already precarious position. As the issue becomes more pertinent to understanding how the CPEC may provide this opportunity and close the gap, employee environmental performance becomes more significant to women [74].

4.5. Descriptive Statistics

We used items from the previous study. To better comprehend research variables like mean, standard deviation, and correlation, all variables were computed to determine which variables had the highest and lowest mean values [54]. Also, the correlation and standard deviation were used to determine how the variables were related and to see how different the responses were. The table below provides all variables’ descriptive statistics and correlation matrix. There is a high association between CPEC expansion and employment opportunities (r = 0.516, p < 0.05), education improvement and the CPEC (r = 0.618, p < 0.05), and quality of life and the CPEC (r = 0.589, p < 0.05). All correlation values are less than 0.80 and significant at two-tailed. While the standard deviation ranges from 0.48 to 0.58, suggesting that mean values are above average, and the low value of standard deviation shows that values are close to the mean, and the mean values are higher than the mid values (See Table 4).

5. A Legal Framework between Pakistan and China

The CPEC is a part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), a strategy by China that essentially intends to construct a road network that connects Europe with southeast Asia and China with Africa. On 20 April 2015 [75], A Memorandum of Understanding and 51 agreements totaling $46 billion were signed by the Chinese President Xi Jinping and the Prime Minister of Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif. [76], which is how the project started. The $46 billion direct investment in Pakistan that makes up the CPEC project was to be utilized to build highways, electrical power-projects, better to communication infrastructure, manufacturing zones [77], and for the exclusive modernization of Gwadar City to meet international requirements, etc. Chinese investment in Pakistan will greatly increase once the CPEC is put into action. These investments have high risks and significant legal and political implications. Even though Chinese banks gave money to these businesses, which should be profitable like any other business, some Chinese companies may have invested in Pakistan with goals [78].

Pakistan also encourages Chinese investors to enter the services industry, which includes financial, engineering, cultural, sporting, and leisure activities related to construction, as well as communication, educational, and business services, as well as environmental, social, and health services, as well as travel and tourism-related services. According to the Pakistan Board of Investment, foreign investments are protected by the Foreign Private Investment (Promotion and Protection) Act of 1976 and the Protection of Economic Reforms Act of 1992 [79]. Section 6 of the 1976 Act Law about the requirements of the 1947 Act states that international investors in the industrial ventures of countrywide government have approved and can withdraw their money at any time in their home currency [80].

5.1. Remittances and Foreign Direct Investment

Table 5 shows how the CPEC’s integration significantly increased foreign direct investment, benefiting the country. [81,82]. However, there has been a global decline in investment activities and remittances as a current result of the COVID-19 epidemic and the lockdown scenario [83]. It displays direct investment in China and Pakistan (see Table 5).

Table 5.

Pandemic Situation.

5.2. Rural Women in Pakistan

Pakistani women contribute to the socioeconomic activities and economic growth of the country. Women who work at home indirectly support their families while developing intellectually and physically. Children’s strong upbringing, physical growth, and sound mental health depend on women’s empowerment in socially conscious fields, such as education and health. [84]. Unfortunately, women are typically restricted to domestic responsibilities in Pakistan, which is seen as patriarchal and emanating from a male-dominated society, especially in rural regions [85].

Due to their disrespect and perception as members of the middle and upper classes, women are frequently the focus of violence in rural communities, where they continue to experience systemic disadvantages and are given inferior rights and decision-making opportunities [86]. Women suffer social and cultural discrimination due to traditional norms, family regulations, and low social status in rural areas. Violence against women is possible, including rape, burning, honor killings, and acid throwing. [87]. The following designed specific predictions of the hypothesis included:

H1.

Pakistani rural women’s perceptions of their own self-improvement and CPEC’s development act as mediators;

H2.

CPEC significantly influences rural development;

H3.

Opportunities for women are regarded to be significantly more favorable in rural areas due to rural development;

H4.

Rural development greatly affects how rural women feel about the quality of their lives;

H5.

Rural development is a link between the growth of CPEC and rural women’s ideas about how they can improve themselves in Pakistan.

5.3. Rule of Law

Before the CPEC, Pakistan’s civilian governments fluctuated, and military regimes ruled for extended periods, leading to notably protracted political unrest [88]. A legal expert at the High Court claimed that, as a result, a homely and unpredictable environment developed that held back the country’s progress. After two democratic terms under the “rule of law” were effectively accomplished, this measure of consistency sharply fell. This illustrates the improved standard of law enforcement-related property rights, contract enforcement, and police and court services to improve the socioeconomic environment [89]. The final option to choose the eastern route rather than the western route was taken after consideration by a number of experts in the fields of geography, security, and civil engineering based on the security situation, technological selection, distance, and geo-feasibility. [90]. This is a response to the claim that the provinces of Punjab and Sindh got special treatment when it came to CPEC projects and routes in the beginning [91]. Later, equal disparities were used to compensate for the remaining provinces and areas [92,93].

5.4. Legal Risks

Risks associated with construction projects include those related to politics, security, the environment, technology, the economy, culture, and the law; when engaging in international construction projects like international joint ventures (IJVs), AEC businesses are exposed to these risks (IJVs) [94,95]. The term ‘legal’ refers to all legal requirements, including those pertaining to employment, taxes, resources, import and export, and other project-related elements [96]. International project firms and the host nation both experience the accompanying LR. These LRs include contract violations and a failure to uphold court orders in IJVs for construction. So, the strength of the legal systems in the host countries is very important for the success of foreign joint ventures (IJVs). A country’s legal system might aid project management and understanding of IJV projects. Sophisticated procedures can help resolve claims, disputes, conflicts, variations, and other contractual difficulties through a strong legal framework. Losses resulting from failure to know, comprehend, be clear about, or adhere to the laws that apply to the business are known as LRs [97].

According to research on major external risks in IJVs in Pakistan, nationalism, protectionism, and a weak judicial framework are the main LRs. Ordinarily, governments in developing countries adopt laws and regulations to protect the interests of local company owners and entrepreneurs in Pakistan [98]. State laws and regulatory requirements for billing, claims, and the security and privacy of multinational enterprises are among them, as are authorities and regulation systems, modified contract formats, a lack of a legal system, corruption, and nepotism. Also, these countries do not have an independent court system and have a weak and unstable way of changing the government [24].

5.5. Social Security

The CPEC project is a prime illustration of the risks and difficulties that the Chinese government and businesses wanting to invest in Pakistan face, including pervasive corruption, a lack of good governance, and the incompetence of public institutions [99,100]. Pakistan has been dealing with a severe issue for almost seven decades, which has compromised its security [101]. Many different militant organizations are operating in Pakistan; Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP), Baluchistan Liberation Army (BLA), Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ), Baluchistan Liberation Front (BLF) [102,103]. The threat of terrorism has always had an impact on Pakistan’s security and stability. Since the start of the Global War on Terror, Pakistan has made significant efforts to curb extremist and terrorist activity (GWOT) [104].

Even though security has significantly improved recently, there is still a chance that these projects’ engineering staff and construction sites will become terrorist targets [105,106]. There have been several attacks on Chinese engineers and workers in Pakistan, some of which have even resulted in fatalities. To establish and implement the CPEC, Pakistan must destroy its domestic terrorist infrastructure. Baluchistan’s unrest has both domestic and international implications. The ongoing nature of the insurgency in the region poses serious hurdles to the effective completion of the CPEC project because of the geostrategic location of Baluchistan’s Gwadar port [107]. The Xinjiang Uyghur autonomous region of China appears to be rife with unrest. The Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KPK) has been threatened by terrorism for a considerable time. Still, the Pakistani Army has launched numerous successful military operations to destroy the terrorist infrastructure in the nation. Pakistan started Operation Zarb-e-Azb against domestic and international groups of terrorists, including the East-Turkistan-Islamic-Movement (ETIM) and Uzbek militants, and have been focusing on China to weaken terrorist networks [108].

5.6. Discussion and Analysis

The Pakistani government made a bold statement in the paper’s first paragraph, claiming that the CPEC and BRI would be a harbinger of economic success and well-being for Pakistan. This research takes a considerably gloomier stance in comparison to this big claim. Although there is reason to believe that the CPEC could boost Pakistani corporate women’s employment, there has been no proof of this since the project’s inception [109], the conditions under which investments in transportation can result in economic transformation through the rule of law and employee environmental consciousness in the CPEC project were taken from the literature on social savings for this research. This study uses the structural interpretation model (ISM) technique to create a hierarchical model of the phenomenon encountered by CPEC [89]. The setup that has been created uses words and images to depict complicated subjects in a logically planned and explained way, one element by one element. The hierarchical model created using the ISM technique is displayed. Regarding developing a collaborative relationship among CPEC members, all the concerns mentioned are quite serious and dynamic. Finally, the ISM model created in this study will aid in the clear understanding of women’s empowerment and unemployment by authorities and lawmakers.

The employment of contemporary technologies for managing fuel waste and effective filtering procedures, as well as state interference in the stringent enforcement of environmental safety rules, can resolve these concerns [110]. Pakistan will only get the most out of the CPEC in infrastructure development, job creation, and industrial development if it keeps strict environmental rules.

Furthermore, China and Pakistan should focus on sticking to their Carbon dioxide (CO2) emission reduction plan to reap the benefits of trade openness through the (BRI) while also protecting of environment and CPEC’s success [111].

Pakistan, a developing country, must deal with serious problems relating to skilled labor. Underemployment, and unemployment are said to be caused by a brain drain of skilled workers and a lack of technical education and awareness. The misconception in the contentious discussion of the CPEC is that it only has anything to do with energy and road connectivity projects. Beyond this limited meaning, the CPEC aims to prepare the nation for enormous Chinese investment and the cross-sectional integration of skilled labor and culture [112]. Pakistan faces a significant issue in finding skilled employees in the context of the CPEC unless we have qualified and diverse human resources across many sectors. The dearth of a skilled and trained female workforce makes this problem even worse. Due to the globalization of the economy, which the CPEC represents, there is a need for a national policy to help women develop their human incomes [113].

Emphasize the benefits of development projects for education and culture, stating that these benefits include new learning opportunities, fresh ideas, exposing residents to other social backgrounds, and providing leisure opportunities for the community. Existing research demonstrates that CPEC offers a wide range of opportunities for economic and educational development [114]. According to previous surveys, infrastructure development significantly impacts local community enrollment in education. Creating an infrastructural system decreases the cost and time of visiting educational institutions. For instance, they said that low literacy rates caused by the scarcity of schools and the placement of universities in the local community are one of the leading causes of undeveloped areas. The connection of long-distance visitors was also found to significantly impact the local community’s literacy rate [115].

Political, economic, social, security, and technical issues impact how well international transportation routes function. In particular, the effects of political hazards are lethal. The fund for construction may be impacted by the economic risks, which have a substantial impact. The safety issues significantly impact the construction process and everyday operations. The influence of social dangers is significant [116]. Because of the limited influence of technological hazards and the advancement of human technology, these risks have less effect on global transportation channels. The International Transport Corridor, which runs through China, Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey, does, however, pose a number of operational risks.

According to the authors, there is a significant possibility that Pakistan will fail to attract international investors if a forum purchasing clause regarding the CPEC is not included in the dispute resolution system. This would be detrimental to the efforts of the region to achieve long-term economic sustainability. However, China has already taken steps to make its investment policies safer. It has set up three international commercial courts, also called Belt and Road courts, one in Xi’an for the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt, one in Shenzhen for the Maritime Silk Road, and one in Beijing that will be the headquarters for all these courts [117].

These courts will offer services for litigation, arbitration, and mediation. According to one theory, China wants these tribunals to resolve any disputes surrounding the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). This places Pakistan in a difficult position and calls for taking preventative steps. The CPEC’s investment depends on Pakistan’s foreign direct investment (FDI) laws and legal framework. Therefore, Pakistan will find it difficult (and less beneficial) to settle these issues in Chinese courts.

6. Conclusions and Limitations of Future Research

This research suggested that the lack of a specific policy framework in the CPEC under the BRI shall result in negative impacts on the sustainable growth of the projects. Therefore, the LR, SS, and EEA variables on the PP of the CPEC, when analyzed through PLS-SEM equation model structuring, depict adverse and harmful impacts. Moreover, women employed under the CPEC of BRI are at risk, and the evaluation shows that the vulnerable segments of society under any such development projects always work with low income and fewer benefits. However, it was also concluded that the suggestions provided in this research shall be taken into consideration by the policy institutions for the effective protection of the women and vulnerable segments of the society under the CPEC of BRI for its sustainable growth and development.

Furthermore, China and Pakistan should focus on sticking to its carbon dioxide (CO2) emission reduction plan in order to reap the benefits of trade openness through the Belt and Road initiative while also protecting the environment and CPEC’s success. Pakistan, a developing country, must deal with serious problems relating to skilled labor; underemployment, and unemployment are said to be caused by a brain drain of skilled workers and a lack of technical education and awareness. The misconception in the contentious discussion of the CPEC is that it only has anything to do with energy and road connectivity projects. Beyond this limited meaning, the CPEC aims to prepare the nation for enormous Chinese investment and the cross-sectional integration of skilled labor and culture. Pakistan faces a significant issue in finding skilled employees in the context of CPEC unless we have qualified and diverse human resources across many sectors. The dearth of a skilled and trained female workforce makes this problem even worse. Due to the globalization of the economy, which the CPEC represents, there is a need for a national policy to help women develop their human incomes.

The new law on Special Economic Zones, which will directly affect how the CPEC is put into place, includes arbitration as an alternative way to settle disagreements. In the absence of a recognized institute to administer dispute resolution and arbitration services, advanced domestic, commercial arbitration will continue to be an appropriate alternative to legal disputes; the domestic law of Pakistan on foreign investment is based on both legal and constitutional security.

China has already taken steps to make its investment policies more secure by setting up three international commercial courts (also known as Belt and Road courts), one in Xi’an for the land-based Silk Road Economic Belt, one in Shenzhen for the Maritime Silk Road, and one in Beijing that will act as the headquarter. These courts will provide services for litigation, arbitration, and mediation. One opinion holds that China wants all conflicts involving the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) to be settled by these tribunals. Given that the CPEC investment is predicated on Pakistan’s foreign direct investment (FDI) rules and legal framework, this puts Pakistan in a tricky situation and necessitates taking proactive measures.

Future researchers can use limitations as a guide to investigate innovative studies because they are key identifiers for them. Since no single study can fully address every possible scenario, each has some methodological, contextual, or theoretical constraints. Future researchers can build on this study’s findings by examining the model in different cultural organizations or by comparing various companies and nations, such as the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor, using contextual constraints. Academics are urged to create the underlying theories that would explain how a working woman’s empowerment perspective could be used to deal with “employee environmental awareness”, “negative workplace attitudes”, “resistance to change”, “counterproductive work behaviors”, and “deviant workplace behaviors” in a positive way. Last but not least, future researchers should add organizational-level variables to the model that is already there.

Author Contributions

Contributed to the conception and design of the study, M.B.K. and S.W.; Investigation, Y.H.; Resources, X.Y. and Y.H.; wrote sections of the manuscript, M.B.K.; Wrote—review & editing, X.Y.; Supervision, S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there is no known conflict of interest.

References

- Ramay, S.A.; Jun, T. Pakistan-China Journey of Brotherhood. Pac. Int. J. 2022, 5, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Investment Claims: Agreement between the Government of the Islamic Republic of Pakistan and Government of the People’s Republic of China on the Reciprocal Encouragement and Protection of Investments. Available online: https://oxia.ouplaw.com/view/10.1093/law:iic/bt455.regGroup.01/law-iic-bt455?prd=IC (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Zhao, J.; Sun, G.; Webster, C. Does China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Improve Connectivity in Pakistan? A Protocol Assessing the Planned Transport Network Infrastructure. J. Transp. Geogr. 2022, 100, 103327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, K.; Sarma, J.; Rippa, A. Infrastructures and b/Ordering: How Chinese Projects Are Ordering China–Myanmar Border Spaces. Territ. Politics Gov. 2022, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, S.; Ahmad, R.E. Pakistan-China Strategic Relations in the Context of Geopolitical. 2022. Available online: https://www.isas.nus.edu.sg/papers/pakistan-china-relations-in-a-changing-geopolitical-environment/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Ul Amin, L.C.R.R.; Awan, G.M.; Begum, M.T. Ground Reality of CPEC: A Continuum of Opportunities or Compelling Puzzle for Pakistan. J. Educ. Res. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2021, 1, 57–67. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.K.; Abdul Rasid, S.Z.; Bardai, B.; Saruchi, S.A. Framework of affordable cooperative housing through an innovative waqf-based source of finance in Karachi. J. Islam. Account. Bus. Res. 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzal, H.; Hassan, S.; Bashir, M.K.; Ali, A. Estimation of Total Factor Productivity Growth of Agriculture Sector in Pakistan. Growth, Yield and Economic Analysis of Dry-Seeded Basmati Rice. Sarhad J. Agric. 2021, 37, 1298–1305. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Yu, C.; Suleman, M.; Manzoor, S. Strategies for Accomplishing the Benefits of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor for Pakistan. J. Econ. Sustain. Dev. 2021, 12, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Akhtar, N.; Khan, H.U.; Jan, M.A.; Pratt, C.B.; Jianfu, M. Exploring the Determinants of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and Its Impact on Local Communities. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211057130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CPEC. Authority Official Website. Available online: https://cpec.gov.pk/news/167 (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Sadik-Zada, E.R. Political Economy of Green Hydrogen Rollout: A Global Perspective. Sustainability 2021, 13, 13464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, X.; Liu, X.; Gong, M. An Improved Method of Assessing Marine Utilization Impact to Describe the Man-Land Relationship for Coastal Management: A Case Study of the Laizhou Bay, China. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behram, M.; Oğlak, S.C.; Dağ, İ. Circulating Levels of Elabela in Pregnant Women Complicated with Intrauterine Growth Restriction. J. Gynecol. Obstet. Hum. Reprod. 2021, 50, 102127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oluwatosin, E.A. The Role of Female Human Capital in Sustainable Economic Development. J. Glob. Econ. Bus. Financ. 2022, 4, 28–33. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Nawaz, T. Regional connectivity through China Pakistan economic cooridor: Challenges and prospects. J. Pak. China Stud. JPCS 2021, 2, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W. Xi Jinping’s ‘Major Country Diplomacy’: The Role of Leadership in Foreign Policy Transformation. J. Contemp. China 2019, 28, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bekkevold, J.I. What Xi’s First Decade Tells Us about the Next. Foreign Policy. 13 October 2022. Available online: https://foreignpolicy.com/2022/10/13/xi-jinping-china-ccp-communist-party-congress-geopolitics/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Ferdinand, P. Westward Ho—The China Dream and ‘One Belt, One Road’: Chinese Foreign Policy under Xi Jinping. Int. Aff. 2016, 92, 941–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z. Upgrading of Industrial Structure in China’s Economic Growth and the Belt and Road Initiative. In The Belt and Road: Industrial and Spatial Coordinated Development; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 85–135. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatia, B.; Rana, B.S. Belt and Road Initiative (BRI): Modernisation of China, Mao to Xi Jinping. Himachal Pradesh Univ. J. 2020, 8, 39. [Google Scholar]

- Waqas, M. Identification of Risk Factors Affecting China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) Projects; an Empirical Study. J. Bus. Manag. Stud. JBMS 2022, 1, 68–73. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, W.; Ni, X.; Hussain, A.; Neelam, B. Relationship of Transport Infrastructure, China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and Elimination of Poverty: A Case of Hazara Division. J. Manag. Res. 2021, 7, 68–81. [Google Scholar]

- Khan, M.; Mahmood, A.; Shoaib, M. Role of Ethical Leadership in Improving Employee Outcomes through the Work Environment, Work-Life Quality and ICT Skills: A Setting of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Sustainability 2022, 14, 11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, S. Decoding Chinese Bilateral Investment Treaties; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Leal Filho, W.; Marisa Azul, A.; Brandli, L.; Lange Salvia, A.; Wall, T. Partnerships for the Goals; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Safdar, M.T. The Local Roots of Chinese Engagement in Pakistan; Carnegie Endowment for International Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Siddiqa, A. Pakistan-GCC Relationship: Reframing Policy Trajectories. Strateg. Stud. 2021, 41, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, L. Examining the CPEC through the Lens of South-South Cooperation. Political Sci. Undergrad. Rev. 2021, 6, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, T.; Huang, J.; Xie, W. Bilateral Economic Impacts of China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. Agriculture 2022, 12, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiep, N.C.; Wang, M.; Mohsin, M.; Kamran, H.W.; Yazdi, F.A. An Assessment of Power Sector Reforms and Utility Performance to Strengthen Consumer Self-Confidence towards Private Investment. Econ. Anal. Policy 2021, 69, 676–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, N.; Fani, M.I. China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) opportunities and threats at domestic and regional circles. Pak. J. Int. Aff. 2021, 4, 240–254. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, S.; Rafiq, M.; Quddus, A.; Ahmad, N.; Pham, P.T. China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: Cooperate Investment Development and Economic Modernization Encouragement. J. Contemp. Issues Bus. Gov. 2021, 27, 96–108. [Google Scholar]

- Islam, S.A. Umbrella of China Pakistan Economic Corridor Influence on Local Business Industries and Trade Balance: A Mediation Analysis in Special Economic Zone of Hattar. Indian J. Econ. Bus. 2021, 20, 955–971. [Google Scholar]

- Shafqat, S. The China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. Rethink. China Middle East Asia Mult. World 2022, 34–35, 96. [Google Scholar]

- Boon, H.T.; Ong, G.K. Military Dominance in Pakistan and China–Pakistan Relations. Aust. J. Int. Aff. 2021, 75, 80–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCartney, M. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC): Infrastructure, Social Savings, Spillovers, and Economic Growth in Pakistan. Eurasian Geogr. Econ. 2022, 63, 180–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmood, S.; Ali, G.; Menhas, R.; Sabir, M. Belt and Road Initiative as a Catalyst of Infrastructure Development: Assessment of Resident’s Perception and Attitude towards China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0271243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arif, A.M.; Hameed, A.; Anwar, A. SWOT Analysis of Kaghan Valley, Mansehra: Some Suggested Measures for Sustainable Tourism Development. Glob. Political Rev. 2022, 7, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landry, D. A Torrent or a Trickle? The Local Economic Impacts of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Oxf. Dev. Stud. 2022, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, S. Socio-Political Significance of China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and Its Impact on Regional Politics. 2020, p. 46. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/344227987 (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Zubair, M.; Ali, A.; Naeem, S.; Jamal, F.; Anam, S.; Bukhari, S.A. The Economic Corridor Between China and Pakistan Has an Impact on Pakistan’s Economy. J. Stat. 2022, 25, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Grof, K. All Infrastructure Projects Lead to Beijing: How the Belt and Road Initiative Has Influenced China’s Regional Policy. Ph.D. Thesis, Wright State University, Dayton, OH, USA, August 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Naseer, R.; Wang, Q.; Ali, A. A Narrative of Debt Trap Vs Connectivity under CPEC: A Case of Gwadar Port. Res. J. South Asian Stud. 2022, 37, 141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M.; Husnain, S.M. Recalibrating Impact of Regional Actors on Security of China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Fudan J. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2022, 15, 437–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetly, R. The Politics of Gwadar Port: Baluch Nationalism and Sino-Pak Relations. Round Table 2021, 110, 432–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, S.; Hassan, S.Z.; Mian, S.A. Business Incubation and Acceleration in Pakistan: An Entrepreneurship Ecosystem Development Approach. In Handbook of Research on Business and Technology Incubation and Acceleration: A Global Perspective; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2021; p. 280. [Google Scholar]

- Rashid, F.; Butt, F.S.; Khalid, B. Inspecting the Effect of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor on Quality of Life: The Moderating Role of Economic Benefit. Pak. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2021, 5, 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Energy Projects under CPEC. China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) Authority Official Website. Available online: https://cpec.gov.pk/energy (accessed on 15 October 2022).

- Duan, W.; Khurshid, A.; Nazir, N.; Calin, A.C. Pakistan’s Energy Sector—From a Power Outage to Sustainable Supply. Examining the Role of China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. Energy Environ. 2021, 33, 0958305X211044785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 1320MW Sahiwal Coal-Fired Power Plant. China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) Authority Official Website. Available online: https://cpec.gov.pk/project-details/2 (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Song, A.Y.; Fabinyi, M. China’s 21st Century Maritime Silk Road: Challenges and Opportunities to Coastal Livelihoods in ASEAN Countries. Mar. Policy 2022, 136, 104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asif, M. Confucius Institute as an Instrument for the Promotion of Chinese Public and Cultural Diplomacy in Pakistan. Asian J. Manag. Entrep. Soc. Sci. 2022, 2, 39–69. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, J.; Xi, C.; Imran, M.; Kumari, J. Cross Border Project in China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and Its Influence on Women Empowerment Perspectives. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alavi, S.; Aghakhani, H. Identifying the Effect of Green Human Resource Management Practices on Lean-Agile (LEAGILE) and Prioritizing Its Practices. Int. J. Product. Perform. Manag. 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogato, G.S. The Quest for Gender Equality and Women’s Empowerment in Least Developed Countries: Policy and Strategy Implications for Achieving Millennium Development Goals in Ethiopia. Int. J. Sociol. Anthropol. 2013, 5, 358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awan, M.A.; Ali, Y. Sustainable Modeling in Reverse Logistics Strategies Using Fuzzy MCDM: Case of China Pakistan Economic Corridor. Manag. Environ. Qual. Int. J. 2019, 30, 1132–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saad, A.; Ijaz, M.; Asghar, M.U.; Yamin, L. China-Pakistan Economic Corridor and Its Impact on Rural Development and Human Life Sustainability. Observations from Rural Women. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0239546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S.; Chong, R.; Pitafi, A.H. China–Pakistan Economic Corridor Projects Development in Pakistan: Local Citizens Benefits Perspective. J. Public Aff. 2019, 19, e1888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanwal, S.; Pitafi, A.H.; Malik, M.Y.; Khan, N.A.; Rashid, R.M. Local Pakistani Citizens’ Benefits and Attitudes toward China–Pakistan Economic Corridor Projects. SAGE Open 2020, 10, 2158244020942759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood-ul-Hassan, K. TAPI: A New Silk Route of Regional Energy Cooperation. Def. J. 2019, 22, 29–42. [Google Scholar]

- Woo, E.-J.; Kang, E. Employee Environmental Capability and Its Relationship with Corporate Culture. Sustainability 2021, 13, 8684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, M.; Ali, M.; Faqir, K.; Begum, S.; Haider, B.; Shahzad, K.; Nosheen, N. China Pakistan Economic Corridor Digital Transformation. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 887848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tansel, A.; Gungor, N. Gender Effects of Education on Economic Development in Turkey. J. Econ. Stud. 2013, 40, 794–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Facts and Figures: Economic Empowerment. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/economic-empowerment/facts-and-figures (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Quak, E.; Barenboim, I.; Guimaraes, L. Female Entrepreneurship and the Creation of More and Better Jobs in Sub-Saharan African Countries; MUVA Paper Series; Institute of Development Studies: Brighton, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Parker, K. Women More than Men Adjust Their Careers for Family Life; Pew Research Center: Washington, DC, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Planning, Development & Special Initiatives. Available online: https://www.pc.gov.pk/web/gender (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Niazi, K.; He, G.; Ullah, S. Lifestyle Change of Female Farmers through CPEC’s Coal Power Plant Project Initiative. J. Int. Women Stud. 2019, 20, 15. [Google Scholar]

- Accountability & Action: Addressing Evidence Gaps in Strengthening Human Rights for Women and Girls–AVPN. Available online: https://avpn.asia/blog/accountability-action-addressing-evidence-gaps-in-strengthening-human-rights-for-women-and-girls/?gclid=CjwKCAjwtKmaBhBMEiwAyINuwIl7Xoa3jzHxhJI9xr9K0PFjbxdsGOXErM1AFqpXkoANJrOovjd1_BoCq7kQAvD_BwE (accessed on 16 October 2022).

- Bhattacharya, S. Status of Women in Pakistan. J. Res. Soc. Pak. 2014, 51, 179–210. [Google Scholar]

- Sadaquat, M.B. Employment Situation of Women in Pakistan. Int. J. Soc. Econ. 2011, 38, 98–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jalal-ud-Din, M.; Khan, M. Socio-Economic and Cultural Constraints of Women in Pakistan with Special Reference to Mardan District, NWFP Province. Sarhad J. Agric. 2008, 24, 485–493. [Google Scholar]

- Abid, M.; Ashfaq, A. CPEC: Challenges and Opportunities for Pakistan. J. Pak. Vis. 2015, 16, 142–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ghani, W.I.; Sharma, R. China-Pakistan Economic Corridor Agreement: Impact on Shareholders of Pakistani Firms. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2018, 10, 148–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H. Motivation behind China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ Initiatives and Establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank. J. Contemp. China 2017, 26, 353–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Shoaib, M. Surge in Economic Growth of Pakistan: A Case Study of China Pakistan Economic Corridor. Front. Psychol. 2022, 13, 900926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Hameed, J.; Khuhro, R.A.; Albasher, G.; Alqahtani, W.; Sadiq, M.W.; Wu, T. The Impact of the Economic Corridor on Economic Stability: A Double Mediating Role of Environmental Sustainability and Sustainable Development under the Exceptional Circumstances of COVID-19. Front. Psychol. 2021, 11, 634375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, S.; Qian, X.; Liu, T. Belt and Road Initiative and Chinese Firms’ Outward Foreign Direct Investment. Emerg. Mark. Rev. 2019, 41, 100629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Belder, R.; Ali Khan, M. Legal Aspects of Doing Business in Pakistan. In Int’l L.; HeinOnline: Getzville, NY, USA, 1986; Volume 20, p. 535. [Google Scholar]

- Ullah, S.; Hussain, S.; Rustandi Kartawinata, B.; Muhammad, Z.; Fitriana, R. Empirical Nexus between Chinese Investment under China–Pakistan Economic Corridor and Economic Growth: An ARDL Approach. Cogent Bus. Manag. 2022, 9, 2032911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kafle, H.B. China’s Foreign Direct Investment in South Asia: A Strategic Quest of China’s Economic Diplomacy. Shanti J. 2022, 1, 49–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A.; Pinglu, C.; Ullah, S.; Elahi, M.A. A Pre Post-COVID–19 Pandemic Review of Regional Connectivity and Socio-Economic Development Reforms: What Can Be Learned by Central and Eastern European Countries from the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor. Comp. Econ. Res. Cent. East. Eur. 2021, 24, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jolly, P.M.; Gordon, S.E.; Self, T.T. Family-Supportive Supervisor Behaviors and Employee Turnover Intention in the Foodservice Industry: Does Gender Matter? Int. J. Contemp. Hosp. Manag. 2021, 34, 1084–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imran, M.; Akhtar, S.; Chen, Y.; Ahmad, S. Environmental Education and Women: Voices from Pakistan. SAGE Open 2021, 11, 21582440211009468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jabeen, S.; Haq, S.; Jameel, A.; Hussain, A.; Asif, M.; Hwang, J.; Jabeen, A. Impacts of Rural Women’s Traditional Economic Activities on Household Economy: Changing Economic Contributions through Empowered Women in Rural Pakistan. Sustainability 2020, 12, 2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongdao, Q.; Khaskheli, M.B.; Rehman Saleem, H.A.; Mapa, J.G.; Bibi, S. Honor Killing Phenomena in Pakistan. JL Pol’y Glob. 2018, 73, 169. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, R.; Mi, H.; Fernald, L.W. Revisiting the Potential Security Threats Linked with the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). J. Int. Counc. Small Bus. 2020, 1, 64–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qureshi, A.H. China/Pakistan Economic Corridor: A Critical National and International Law Policy Based Perspective. Chin. J. Int. Law 2015, 14, 777–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surahio, M.K.; Gu, S.; Mahesar, H.A.; Soomro, M.M. China–Pakistan Economic Corridor: Macro Environmental Factors and Security Challenges. SAGE Open 2022, 12, 21582440221079820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamran, M.; Bian, J.; Li, A.; Lei, G.; Nan, X.; Jin, Y. Investigating Eco-Environmental Vulnerability for China–Pakistan Economic Corridor Key Sector Punjab Using Multi-Sources Geo-Information. ISPRS Int. J. Geoinf. 2021, 10, 625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Younis, M.; Shah, N.H.; Gul, R.; Khan, H.; Malik, R. Impact of change of government in Pakistan on cpec and Pak-China relations. PalArch’s J. Archaeol. Egypt/Egyptol. 2021, 18, 3054–3067. [Google Scholar]

- Westfall, S. Pakistan’s Prime Minister Embraces China’s Policy toward Uyghurs in Remarks on Communist Party Centenary. Washington Post. 2 July 2021. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2021/07/02/pakistan-prime-minister-backs-china-on-uyghurs/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Zahoor, H.; Khan, R.M.; Ali, B.; Maqsoom, A.; Mazher, K.M.; Ullah, F. Diverse Impact of Sensitive Sub-Categories of Demographic Variables on Safety Climate of High-Rise Building Projects. Architecture 2022, 2, 175–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akdeniz, M.B.; Talay, M.B. Happily (N) Ever after: An Empirical Examination of the Termination of IJVs across Emerging versus Developed Markets. J. Bus. Res. 2022, 148, 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idrees, R.Q.; Rehna Gul, D.; Kiyani, S. The China trade model in the ambit of belt and road initiative Pakistan and international law perspective. Pak. J. Int. Aff. 2022, 5, 652–667. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, N.M. Development of Cultural Ecotourism in Gilgit-Baltistan: Opportunities and Challenges in the Wake of the CPEC. China South Asia 2021, 210–224. [Google Scholar]

- Razzaq, A.; Thaheem, M.J.; Maqsoom, A.; Gabriel, H.F. Critical External Risks in International Joint Ventures for Construction Industry in Pakistan. Int. J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 16, 189–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwemlein, J. Strategic Implications of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor; United States Institute of Peace: Washington, DC, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Ismail, M. China-Pakistan Economic Corridor: A Case Study of Internal Security Challenge Faced by Pakistan. Int. J. Policy Stud. 2022, 2, 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Boni, F. Protecting the Belt and Road Initiative. Asia Policy 2019, 14, 5–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. Insurgency in Balochistan. Stratagem 2019, 2, 80–95. [Google Scholar]

- Bhatti, M.N.; Mustafa, G.; Ahmad, F. China Pakistan Economic Corridor: Prospects and Challenges. Pak. Soc. Sci. Rev. 2020, 4, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbas, A.; Baloch, J.; Khoso, P.A. Global War on Terrorism, Its Effects on Pakistan. Progress. Res. J. Arts Humanit. PRJAH 2020, 2, 95–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, F.E.; Abbas, R.; Rashid, M.A. Terrorism in Pakistan: A Critical Analysis. Pak. Lang. Humanit. Rev. 2022, 6, 1003–1013. [Google Scholar]

- Saud, A.; Ahmad, A. Terrorism and Transnational Groups in Pakistan. Strateg. Stud. 2018, 38, 37–51. [Google Scholar]

- Droogan, J. The Perennial Problem of Terrorism and Political Violence in Pakistan. J. Polic. Intell. Count. Terror. 2018, 13, 202–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, S.M. FATA Merges into Pakistan’s National System. South Asian Surv. 2022, 29, 103–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekhteyar, M.A.; Aleem, N.; Kumar, H.; Ali, W.; Shabbir, T. Critical Discourse Analysis of Newspapers’ Articles: CPEC In the Lens of Lexicalization. Webology 2021, 18, 929–942. [Google Scholar]

- Hadi, N.U.; Batool, S.; Mustafa, A. CPEC: An Opportunity for a Prosperous Pakistan or Merely a Mirage of Growth and Development. Dialogue Pak. 2018, 13, 296–311. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M. Pakistan’s Quest for Coal-Based Energy under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC): Implications for the Environment. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 31935–31937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Wu, M.; Shouse, R.C. Impact of Organizational Culture, Occupational Commitment and Industry-Academy Cooperation on Vocational Education in China: Cross-Sectional Hierarchical Linear Modeling Analysis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0264345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Staff Report. President Urges Lawmakers to ‘End Polarisation’ to Decide Election Date Together. Pakistan Today. 6 October 2022. Available online: https://www.pakistantoday.com.pk/2022/10/06/president-urges-lawmakers-to-end-polarisation-to-decide-election-date-together/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Global Times CPEC Laying Foundation for Sustained Indigenous Economic Modernization; Growth Within and across the Region Is Logical Next Step: Pakistan PM—Global Times. Available online: https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202208/1272927.shtml (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Desk, N. Current Status of Pakistan-China Bilateral Relations. Pakistan Observer. 1 October 2022. Available online: https://pakobserver.net/current-status-of-pakistan-china-bilateral-relations/ (accessed on 25 October 2022).

- Awan, M.A.; Ali, Y. Risk Assessment in Supply Chain Networks of China–Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). Chin. Political Sci. Rev. 2022, 7, 550–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H. Evolution of the Belt and Road. In The Ebb and Flow of Globalization; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 195–208. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).